| Issue |

A&A

Volume 514, May 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A35 | |

| Number of page(s) | 25 | |

| Section | Stellar atmospheres | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911899 | |

| Published online | 07 May 2010 | |

- Top

- Abstract

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Model atmospheres and ...

- 3 Line formation in ...

- 4 The influence of ...

- 5 Simulating line ...

- 6 Towards realistic ...

- 7 CO

Line formation in AGB atmospheres including velocity effects

Molecular line profile variations of long period variables

W. Nowotny1 - S. Höfner2 - B. Aringer1

1 - University of Vienna, Department of Astronomy, Türkenschanzstraße 17, 1180 Wien, Austria

2 - Department of Physics and Astronomy, Division of Astronomy and Space Physics, Uppsala University, Box 515, 75120 Uppsala, SwedenReceived 20 February 2009 / Accepted 19 January 2010

Abstract

Context. Towards the end of the evolutionary stage of the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) the atmospheres of evolved red giants are considerably influenced by radial pulsations of the stellar interiors and developing stellar winds. The resulting complex velocity fields severely affect molecular line profiles (shapes, time-dependent shifts in wavelength, multiple components) observable in near-infrared spectra of long period variables. Time-series high-resolution spectroscopy allows us to probe the atmospheric kinematics and thereby study the mass loss process.

Aims. With the help of model calculations the complex line formation process in AGB atmospheres was explored with the focus on velocity effects. Furthermore, we aimed for atmospheric models which are able to quantitatively reproduce line profile variations found in observed spectra of pulsating late-type giants.

Methods. Models describing pulsation-enhanced dust-driven winds were used to compute synthetic spectra under the assumptions of chemical equilibrium and LTE. For this purpose, we used molecular data from line lists for the considered species and solved the radiative transfer in spherical geometry including the effects of velocity fields. Radial velocities (RV) derived from Doppler-shifted (components of) synthetic line profiles provide information on the gas velocities in the line-forming region of the spectral features. In addition, we made use of radial optical depth distributions to give estimates for the layers where lines are formed and to illustrate the effects of velocities in the line formation process.

Results. Assuming uniform gas velocities for all depth points of an atmospheric model we estimated the conversion factor between gas velocities and measured RVs to p = /RV

/RV  1.2-1.5. On the basis of dynamic model atmospheres and by

applying our spectral synthesis codes we investigated in detail the

finding that various molecular features in AGB spectra

originate at different geometrical depths of the very extended

atmospheres of these stars. We show that the models are able to

quantitatively reproduce the characteristic line profile variations of

lines sampling the deep photosphere (CO

1.2-1.5. On the basis of dynamic model atmospheres and by

applying our spectral synthesis codes we investigated in detail the

finding that various molecular features in AGB spectra

originate at different geometrical depths of the very extended

atmospheres of these stars. We show that the models are able to

quantitatively reproduce the characteristic line profile variations of

lines sampling the deep photosphere (CO  = 3, CN)

of Mira variables and the corresponding discontinuous, S-shaped

RV curve. The global velocity fields (traced by different

features) of typical long-period variables are also realistically

reproduced. Possible reasons for discrepancies concerning other

modelling results (e.g. CO

= 3, CN)

of Mira variables and the corresponding discontinuous, S-shaped

RV curve. The global velocity fields (traced by different

features) of typical long-period variables are also realistically

reproduced. Possible reasons for discrepancies concerning other

modelling results (e.g. CO  = 2 lines)

are outlined. In addition, we present a model showing

variations of CO

= 2 lines)

are outlined. In addition, we present a model showing

variations of CO  =

3 line profiles comparable to observed spectra of semiregular

variables and discuss that the non-occurence of line doubling in these

objects may be due to a density effect.

=

3 line profiles comparable to observed spectra of semiregular

variables and discuss that the non-occurence of line doubling in these

objects may be due to a density effect.

Conclusions. The results of our line profile modelling are another indication that the dynamic models studied here are approaching a realistic representation of the outer layers of AGB stars with or without mass loss.Key words: stars: late-type - stars: AGB and post-AGB - stars: atmospheres - infrared: stars - line: profiles - line: formation

1 Introduction

Stars on the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) represent objects of low to intermediate main sequence mass (

0.8-8

0.8-8  )

in a late evolutionary phase. While they exhibit low effective

temperatures (<3500 K), their luminosities can reach

values of up to a few 10

)

in a late evolutionary phase. While they exhibit low effective

temperatures (<3500 K), their luminosities can reach

values of up to a few 10

at the tip of the AGB, placing them in the upper right corner

of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. Compared to the atmospheres of most

other types of stars the outer layers of these evolved red giants have

remarkable properties (see e.g. the review by Gustafsson

& Höfner 2004,

below GH04).

at the tip of the AGB, placing them in the upper right corner

of the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. Compared to the atmospheres of most

other types of stars the outer layers of these evolved red giants have

remarkable properties (see e.g. the review by Gustafsson

& Höfner 2004,

below GH04). In the cool and very extended atmospheres (extensions of the same order as the radii of the stars; up to a few 100

), molecules

can form. Their large number of internal degrees of freedom results in

a plethora of spectral lines. Thus, molecules significantly affect the

spectral appearance of late-type giants at visual and infrared

wavelengths (IR; e.g. Lançon & Wood 2000;

Gautschy-Loidl et al. 2004,

GH04; Aringer et al. 2009).

), molecules

can form. Their large number of internal degrees of freedom results in

a plethora of spectral lines. Thus, molecules significantly affect the

spectral appearance of late-type giants at visual and infrared

wavelengths (IR; e.g. Lançon & Wood 2000;

Gautschy-Loidl et al. 2004,

GH04; Aringer et al. 2009).

On the upper part of the AGB, the stars become instable to strong radial pulsations. This leads to a pronounced variability of the emitted flux with amplitudes of up to several magnitudes in the visual (e.g. Lattanzio & Wood 2004). Since the variations occur on long time scales of a few 10 to several 100 days, pulsating AGB stars are often referred to as long period variables (LPVs). In the past, different types of LPVs were empirically classified according to the regularity of the light change and the visual light amplitude: Mira variables (regular,

> 2.5

> 2.5 ),

semiregular variables (SRVs, poor regularity,

),

semiregular variables (SRVs, poor regularity,  < 2.5

< 2.5 ), and

irregular variables (irregular,

), and

irregular variables (irregular,  < 1-2

< 1-2 ). Major

advances in our understanding of the pulsation of AGB stars

were achieved by exploiting the data sets of surveys for microlensing

events (MACHO, OGLE, EROS), which produced a substantial number of

high-quality lightcurves for red variables as a by-product. According

to the pioneering work in this field by Wood et al. (1999) and Wood (2000), and to a

number of subsequent studies (e.g. Lebzelter et al. 2002; Ita

et al. 2004a,b)

it is probably more adequate to characterise LPVs according to their

pulsation mode than to their light change in the visual as it was done

historically. From observational studies during recent years

(see e.g. Lattanzio & Wood 2004) it appears

that stars start to pulsate (as SRVs) in the second/third overtone mode

(corresponding to sequence A in Fig. 1 of Wood 2000) and switch

then to the first overtone mode (sequence B). Light amplitudes

are increasing while the stars evolve and finally become Miras. In this

stadium they pulsate in the fundamental mode (sequence C) and

show highly periodic light changes. Observational evidence for this

evolution scenario was found for LPVs in the globular

cluster 47 Tuc by Lebzelter et al. (2005b) and

Lebzelter & Wood (2005).

). Major

advances in our understanding of the pulsation of AGB stars

were achieved by exploiting the data sets of surveys for microlensing

events (MACHO, OGLE, EROS), which produced a substantial number of

high-quality lightcurves for red variables as a by-product. According

to the pioneering work in this field by Wood et al. (1999) and Wood (2000), and to a

number of subsequent studies (e.g. Lebzelter et al. 2002; Ita

et al. 2004a,b)

it is probably more adequate to characterise LPVs according to their

pulsation mode than to their light change in the visual as it was done

historically. From observational studies during recent years

(see e.g. Lattanzio & Wood 2004) it appears

that stars start to pulsate (as SRVs) in the second/third overtone mode

(corresponding to sequence A in Fig. 1 of Wood 2000) and switch

then to the first overtone mode (sequence B). Light amplitudes

are increasing while the stars evolve and finally become Miras. In this

stadium they pulsate in the fundamental mode (sequence C) and

show highly periodic light changes. Observational evidence for this

evolution scenario was found for LPVs in the globular

cluster 47 Tuc by Lebzelter et al. (2005b) and

Lebzelter & Wood (2005).

The pulsating stellar interior of an AGB star severely influences the outer layers. The atmospheric structure is periodically modulated, and in the wake of the emerging shock waves dust condensation can take place. Radiation pressure on the newly formed dust grains (at least in the C-rich case, cf. Sect. 2.1) leads to the development of a rather slow (terminal velocities of max. 30 km s-1) but dense stellar wind with high mass loss rates (from a few 10-8 up to 10-4

yr-1;

e.g. Olofsson 2004).

yr-1;

e.g. Olofsson 2004).

As a consequence of these dynamic processes - pulsation and mass loss - the atmospheres of evolved AGB stars eventually become even more extended than non-pulsating red giants in earlier evolutionary stages. The resulting atmospheric structure strongly deviates from a hydrostatic configuration and shows temporal variations on global and local scales (Sect. 2). The complex, non-monotonic velocity fields with relative macroscopic motions of the order of 10 km s-1 have substantial influence on the shapes of individual spectral lines (Doppler effect). Observational studies have demonstrated that time series high-resolution spectroscopy in the near IR (where AGB stars are bright and well observable) is a valuable tool to study atmospheric kinematics throughout the outer layers of pulsating and mass-losing red giants (e.g. Hinkle et al. 1982, from now on HHR82; or Alvarez et al. 2000). Radial velocities (RV) derived from Doppler-shifts of various spectral lines provide clues on the gas velocities in the line-forming regions of the respective features. A detailed review on studies of line profile variations for AGB stars (observations and modelling) can be found for example in Nowotny (2005, below N05).

In two previous papers (Nowotny et al. 2005a,b, from now on Paper I and Paper II, respectively) we investigated whether observed variations of line profiles can be comprehended with state-of-the-art dynamic model atmospheres. We were able to show that the used models allow to qualitatively reproduce the behaviour of spectral lines originating in different regions of the extended atmospheres. The work presented here can be regarded as an extension of the previous two papers about line profile modelling. The aim is to shed light on the intricate line formation process within the atmospheres of evolved red giants with an emphasis on the velocity effects (Sects. 3-5 and 7.4). In addition, we report on our efforts to achieve realistic models, which are able to reproduce line profile variations and the derived RVs even quantitatively (Sects. 6 and 7).

2 Model atmospheres and spectral synthesis

2.1 General remarks

Modelling the cool and very extended atmospheres of evolved AGB stars remains challenging due to the intricate interaction of different complicated phenomena (convection, pulsation, radiation, molecular and dust formation/absorption, acceleration of winds). Dynamic model atmospheres are constructed to simulate and understand the physical processes (e.g. mass loss) occuring in the outer layers of AGB stars. In particular they are needed if one is interested in reproducing the complex and temporally varying atmospheric structures that form the basis for radiative transfer calculations, which allows us to simulate observational results (spectra, photometry, etc.).

For our line profile modelling we used dynamic model atmospheres as described in detail by Höfner et al. (2003; DMA3), Gautschy-Loidl et al. (2004; DMA4), N05 or Papers I and II. These models represent the scenario of pulsation-enhanced dust-driven winds (cf. Sects. 4.7 and 4.8 of GH04). They provide a consistent and realistic description from the deep and dust-free photosphere (dominated by the pulsation of the stellar interior) out to the dust-forming layers and beyond to the stellar wind region at the inner circumstellar envelope (characterised by the cool, steady outflow). This is accomplished by a combined and self-consistent solution of hydrodynamics, frequency-dependent radiative transfer and a detailed time-dependent treatment of dust formation and evolution.

As a result of deep-reaching convection (dredge-up), nucleo-synthesis products can be mixed up from the stellar interior of AGB stars, resulting in a metamorphosis of the molecular chemistry of the whole atmosphere (e.g. Busso et al. 1999; Herwig 2005). The most important product of all the nuclearly processed material mixed up is carbon 12C. As a consequence, the stars can turn from oxygen-rich (C/O < 1) to carbon-rich (C/O > 1) during the late AGB phase. The resulting so-called carbon stars (C stars) can be found close to the tip of the AGB in observed colour-magnitude diagrams (e.g. Nowotny et al. 2003a). The drastic change of the atmospheric chemical composition is not only relevant for the observable spectral type of the star (changing from M to C), it is also crucial for the formation of circumstellar dust.

Observational studies revealed a rich mineralogy in the dusty outflows of O-rich objects (e.g. Molster & Waters 2003, and references therein). Unfortunately, the dust formation process is theoretically not fully understood. Many physical and chemical details of the process are still not clear, which would be necessary for a fully consistent numerical treatment. In addition to the lack of a grain formation theory, there is an ongoing debate concerning the underlying physics of the driving mechanism (Woitke 2006b, 2007; Höfner 2007; Höfner & Andersen 2007). A potential solution was recently suggested by Höfner (2008).

Things are quite different for C-rich stars, where we find a rather simple composition of the circumstellar dust. A very limited variety of dust species were identified by their spectral features (e.g. Molster & Waters 2003), as for example SiC (prominent feature at

11

11  m)

or MgS (broad emission band around 30

m)

or MgS (broad emission band around 30  m). The most

important species is amorphous carbon dust, though. Not producing any

distinctive spectral feature, grains of carbon dust represent the

dominating condensate and play a crucial role from the dynamic point of

view (mass loss process). Amorphous carbon fulfills the relevant

criteria for a catalyst of dust-driven winds: (i) made up of

abundant elements; (ii) simple and efficient formation

process; (iii) refractory, i.e. stable at high

temperatures (

m). The most

important species is amorphous carbon dust, though. Not producing any

distinctive spectral feature, grains of carbon dust represent the

dominating condensate and play a crucial role from the dynamic point of

view (mass loss process). Amorphous carbon fulfills the relevant

criteria for a catalyst of dust-driven winds: (i) made up of

abundant elements; (ii) simple and efficient formation

process; (iii) refractory, i.e. stable at high

temperatures ( 1500 K);

(iv) large radiative cross section around 1

1500 K);

(iv) large radiative cross section around 1  m in order

to absorb momentum. Moreover, the formation and evolution of amorphous

carbon dust grains can be treated numerically in a consistent way by

using moment equations as described in Gail & Sedlmayr (1988) and Gauger

et al. (1990).

As a consequence of this, atmospheric models for

C-rich AGB stars with dusty outflows were quite successfully

calculated and applied in the past by different groups

(see the overviews given by Woitke 2003; or Höfner

et al. 2005),

among them the models used in this work.

m in order

to absorb momentum. Moreover, the formation and evolution of amorphous

carbon dust grains can be treated numerically in a consistent way by

using moment equations as described in Gail & Sedlmayr (1988) and Gauger

et al. (1990).

As a consequence of this, atmospheric models for

C-rich AGB stars with dusty outflows were quite successfully

calculated and applied in the past by different groups

(see the overviews given by Woitke 2003; or Höfner

et al. 2005),

among them the models used in this work.

2.2 Models for atmospheres and winds

Table 1: Characteristics of the dynamic atmospheric models for pulsating, C-rich AGB stars used for the modelling (for a detailed description see text and DMA3).

Following the previous remarks, we concentrated in this study on model atmospheres for C-type LPVs for our line profile modelling, because these models contain a more consistent prescription of dust formation

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) . However, the velocity

effects on line profiles are of general relevance, and a comparison

with observational results of stars with other spectral types

(e.g.

. However, the velocity

effects on line profiles are of general relevance, and a comparison

with observational results of stars with other spectral types

(e.g.  Cyg)

should be justified. This is especially the case for CO lines

because of the characteristic properties of this molecule

(e.g. Sect. 2.2 in Paper I). Table 1 lists the

parameters and the resulting wind properties of the dynamic models used

in this work.

Cyg)

should be justified. This is especially the case for CO lines

because of the characteristic properties of this molecule

(e.g. Sect. 2.2 in Paper I). Table 1 lists the

parameters and the resulting wind properties of the dynamic models used

in this work.

The starting point for the calculation is a hydrostatic initial model, which is very similar to classical model atmospheres (Fig. 1 in DMA3), as for example those calculated with the MARCS-Code (Gustafsson et al. 2008). These initial models are characterised by a set of parameters as listed in the first part of Table 1. They are dust-free and rather compact in comparison with fully developped dynamical structures (e.g. Fig. 4). The effects of pulsation of the stellar interior are then simulated by a variable inner boundary

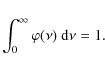

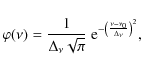

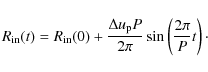

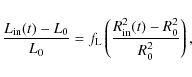

This so-called piston moves sinusoidally with a period P and a velocity amplitude .

Assuming a constant radiative flux at the inner boundary, the

luminosity

.

Assuming a constant radiative flux at the inner boundary, the

luminosity

varies like

varies like

for the models presented in DMA3. The assumptions for the

inner boundary were slightly adapted for the latest generation of

models as discussed in DMA4: an additional free

parameter

for the models presented in DMA3. The assumptions for the

inner boundary were slightly adapted for the latest generation of

models as discussed in DMA4: an additional free

parameter  was introduced so that the luminosity at the inner boundary

varies like

was introduced so that the luminosity at the inner boundary

varies like

where and

and  are the values at the inner boundary of the hydrostatic initial model (

are the values at the inner boundary of the hydrostatic initial model ( =

=  ,

by definition, and

,

by definition, and  corresponds to the previously used case of constant flux at the inner

boundary)

corresponds to the previously used case of constant flux at the inner

boundary)![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) . The luminosity variation

amplitude of the model can be adjusted thereby independent of the

mechanical energy input by the piston. This allows us to tune the

bolometric amplitudes

. The luminosity variation

amplitude of the model can be adjusted thereby independent of the

mechanical energy input by the piston. This allows us to tune the

bolometric amplitudes

to resemble more closely the values derived from observational studies.

Figure 3a

shows the variability of the luminosity L

of one dynamic model as an example.

to resemble more closely the values derived from observational studies.

Figure 3a

shows the variability of the luminosity L

of one dynamic model as an example.

As described in detail in DMA3, the models can be divided into two sub-groups according to their dynamical behaviour:

-

- pulsating model atmospheres where no dust forms;

-

- models developing pulsation-enhanced dust-driven winds.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11899fig01.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg55.png)

Figure 1: Movement of mass shells with time at different depths of the dust-free model W, which exhibits no mass loss and shows a strictly periodic behaviour for all layers. Note the different scales on the radius-ordinates compared to Fig. 2. The shown trajectories represent the points of the adaptive grid at a selected instance of time (higher density of points at the location of shocks) and their evolution with time (cf. the caption of Fig. 2 in DMA3 for further explanations).

Open with DEXTER The atmospheres of LPVs become qualitatively different with the occurence of dust and the development of a stellar wind. The other models listed in Table 1, namely models S and M, represent examples for this second type of dynamic model atmospheres. Again, shock waves are triggered by the pulsating stellar interior and propagate outwards. The difference arises because efficient dust formation can take place in the wake of the shock waves (post-shock regions with strongly enhanced densities at low temperatures). Radiation pressure on the newly formed dust grains results in an outflow of the outer atmospheric layers. This behaviour is demonstrated in Fig. 2, which shows the characteristic pattern of the moving mass layers with model M as an example. While the models without mass loss stay rather compact compared to the hydrostatic initial model (Fig. 3), the models that develop a wind are inflated by it and become much more extended than the corresponding initial model. Numerically, a transmitting outer boundary - allowing outflow; fixed at 20-30

-

is used for the latter type of dynamic model atmospheres. Spatial

structures of model M are shown in Fig. 4,

demonstrating the strong influence of dust formation on the atmospheric

extension. The models S and M exhibit quite a

moderate dust formation process, which leads to a smooth transistion of

the velocity field from the pulsating inner layers to the steady

outflow of the outer layers (see the velocity structure plots

in Fig. 9

of Paper I and Fig. 4 in

this work). In contrast, the model applied in

Sect. 6.1 of Paper II is a representative of a group

of models with a more extreme dust formation. Not every emerging shock

wave leads to the formation of dust grains (cf. Fig. 20

in DMA3) and the velocity field in the dust-forming region may

look very different for similar phases of different pulsation periods.

Pronounced dust shells arise from time to time and propagate outwards

(see the structure plot in Fig. 10

of Paper II).

-

is used for the latter type of dynamic model atmospheres. Spatial

structures of model M are shown in Fig. 4,

demonstrating the strong influence of dust formation on the atmospheric

extension. The models S and M exhibit quite a

moderate dust formation process, which leads to a smooth transistion of

the velocity field from the pulsating inner layers to the steady

outflow of the outer layers (see the velocity structure plots

in Fig. 9

of Paper I and Fig. 4 in

this work). In contrast, the model applied in

Sect. 6.1 of Paper II is a representative of a group

of models with a more extreme dust formation. Not every emerging shock

wave leads to the formation of dust grains (cf. Fig. 20

in DMA3) and the velocity field in the dust-forming region may

look very different for similar phases of different pulsation periods.

Pronounced dust shells arise from time to time and propagate outwards

(see the structure plot in Fig. 10

of Paper II). ![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11899fig02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg56.png)

Figure 2: Same plot as Fig. 1 for model M, representing the scenario of a pulsation-enhanced dust-driven wind. The plot illustrates the different regions within the atmosphere of a typical mass-losing LPV. The innermost, dust-free layers below

2

2  are subject to strictly regular motions caused by the pulsating

interior (shock fronts). The dust-forming region (colour-coded is the

degree of dust condensation

are subject to strictly regular motions caused by the pulsating

interior (shock fronts). The dust-forming region (colour-coded is the

degree of dust condensation  )

at

)

at  2-3

2-3  where the stellar wind is triggered represents dynamically a transition

region with moderate velocities, not necessarily periodic.

A continuous outflow is found from

where the stellar wind is triggered represents dynamically a transition

region with moderate velocities, not necessarily periodic.

A continuous outflow is found from  4

4  outwards, where the dust-driven wind is decisive from the dynamic point

of view.

outwards, where the dust-driven wind is decisive from the dynamic point

of view.

Open with DEXTER We refer to Höfner et al. (2003) for more details about the numerical methods and the atmospheric models.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=15cm,clip]{11899fig03.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg57.png)

Figure 3: Characteristic properties of model W. Plotted in panel a) is the bolometric lightcurve resulting from the variable inner boundary (piston), diamonds mark instances of time for which snapshots of the atmospheric structure were stored by the radiation-hydrodynamics code. Denoted are selected phases for which line profiles are presented in Fig. 20. Other panels: atmospheric structures of the initial hydrostatic model (thick black line) and selected phases

of the dynamic calculation (colour-coded in the same way as the phase

labels of panel a)). Plotted are gas

temperature b), gas density

c), and gas velocities d). Note

that this is a dust-free model and the degree of condensation of carbon

into dust is

of the dynamic calculation (colour-coded in the same way as the phase

labels of panel a)). Plotted are gas

temperature b), gas density

c), and gas velocities d). Note

that this is a dust-free model and the degree of condensation of carbon

into dust is  = 0

for every depth point at each instance of time.

= 0

for every depth point at each instance of time.

Open with DEXTER ![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=15cm,clip]{11899fig04.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg58.png)

Figure 4: Characteristic properties of model M. Radial structures of the initial hydrostatic model (thick black) and selected phases of the dynamic model atmosphere during one pulsation cycle (

= 0.0-

1.0). Plotted are gas temperatures a),

gas densities b), gas velocities

c), and degrees of condensation of carbon into dust

d). Panel b) demonstrates the

larger extension compared to the hydrostatic initial model and the

local density variations.

= 0.0-

1.0). Plotted are gas temperatures a),

gas densities b), gas velocities

c), and degrees of condensation of carbon into dust

d). Panel b) demonstrates the

larger extension compared to the hydrostatic initial model and the

local density variations.

Open with DEXTER 2.3 The specific models used

Model S was already used extensively in the previous Papers I and II to study line profile variations. Its parameters (listed in Table 1) were chosen to resemble the Mira S Cep, as this is the only C-type Mira with an extensive time series of high-resolution spectroscopy and derived RVs (Fig. 17). Table 1 of Paper II lists properties for this object as compiled from the literature for comparison. Model S should not be taken as a specific fit for S Cep, though. A discussion of the difficulties when relating dynamic model atmospheres to certain objects can be found in Sect. 3 of Paper II (or Sect. 2.1.4 in N05). However, there is evidence that the model reproduces the outer layers of this star reasonably well. There are some properties listed in the mentioned tables which can be compared directly and agree to some extent (e.g. L, P,

,

,

). In addition,

low-resolution synthetic spectra in the visual and IR computed

on the basis of model S resemble observed

spectra (ISO, KAO) of S Cep fairly well as

it was shown by Gautschy-Loidl et al. (2004; their

Sect. 5.1).

). In addition,

low-resolution synthetic spectra in the visual and IR computed

on the basis of model S resemble observed

spectra (ISO, KAO) of S Cep fairly well as

it was shown by Gautschy-Loidl et al. (2004; their

Sect. 5.1).

Model M was the (so far) last model of a small parameter study we carried out subsequent to Papers I and II. The intention was not to find a model fitting a certain target of observations better, but to change the model parameters in order to reproduce one particular observational aspect: namely the velocity variations in the inner, dust-free photosphere resulting in a rather uniform RV curve for CO

=

3 lines in spectra of Miras as discussed in Sect. 6.1 and shown

in Fig. 14.

The comparison of the global velocity field of this model M

with observational results in Sect. 6.2 is

still done on a qualitative basis, though. Confronting

RV measurements (Fig. 17) with

the corresponding synthetic values (Fig. 18) provides

some general information of how realistic the velocity structures of

the model are. However, a direct and quantitative comparison

of stellar and model parameters is not feasible at the moment due to

limitations on the observational side (very small number of

stars observed extensively, often only rough estimates for properties

of targets) as well as on the modelling side (only C-rich

models, laborious process to get a RV diagramm as

Fig. 18)

as discussed in Sect. 6.2.

=

3 lines in spectra of Miras as discussed in Sect. 6.1 and shown

in Fig. 14.

The comparison of the global velocity field of this model M

with observational results in Sect. 6.2 is

still done on a qualitative basis, though. Confronting

RV measurements (Fig. 17) with

the corresponding synthetic values (Fig. 18) provides

some general information of how realistic the velocity structures of

the model are. However, a direct and quantitative comparison

of stellar and model parameters is not feasible at the moment due to

limitations on the observational side (very small number of

stars observed extensively, often only rough estimates for properties

of targets) as well as on the modelling side (only C-rich

models, laborious process to get a RV diagramm as

Fig. 18)

as discussed in Sect. 6.2.

While investigating synthetic CO

= 3 line

profile variations based on a few dynamical models available at that

time, we found model W reproducing the observed behaviour of

SRVs (Sect. 7.1)

with similarities to W Hya (increased

= 3 line

profile variations based on a few dynamical models available at that

time, we found model W reproducing the observed behaviour of

SRVs (Sect. 7.1)

with similarities to W Hya (increased  RV).

In Sect. 7.3

we will make a comparison of observational and modelling results only

for this very selected aspect. Relating model W (C-rich

chemistry) and the M-type LPV W Hya to constrain the

parameters of this star is even less possible than for the before

mentioned case of model M, and was not intended.

RV).

In Sect. 7.3

we will make a comparison of observational and modelling results only

for this very selected aspect. Relating model W (C-rich

chemistry) and the M-type LPV W Hya to constrain the

parameters of this star is even less possible than for the before

mentioned case of model M, and was not intended.

2.4 Calculating synthetic line profiles

For the spectral synthesis we followed the numerical approach as described in detail in N05 (Sect. 2.2) and also in Papers I and II. The modelling procedure of dynamic model atmospheres (see DMA3) yields some immediate results, like mass loss rates

,

terminal velocities of the winds

,

terminal velocities of the winds  ,

or degrees of dust condensation in the outflows

,

or degrees of dust condensation in the outflows  .

In addition, it provides snapshots of the

time-dependent atmospheric structure (

.

In addition, it provides snapshots of the

time-dependent atmospheric structure ( , T, p,

u, etc.) at several instances of

time (e.g. Figs. 3

and 4).

These represent the starting point for the aspired spectral synthesis,

accomplished in a two-step process as described below.

, T, p,

u, etc.) at several instances of

time (e.g. Figs. 3

and 4).

These represent the starting point for the aspired spectral synthesis,

accomplished in a two-step process as described below.

The first step, calculating opacities based on a given atmospheric structure, was accomplished with the COMA code, a description of which can be found in Aringer (2000), Gautschy-Loidl (2001), or N05. Informations on recent updates and the latest version can be found in Gorfer (2005), Lederer & Aringer (2009), Aringer et al. (2009). Element abundances for the spectral synthesis were used in consistency with the hydrodynamic models of solar composition. We adopted the values from Anders & Grevesse (1989), except for C, N and O where we took the data from Grevesse & Sauval (1994). This agrees with our previous work (e.g. Aringer et al. 1999, 2009) and results in

0.02.

Subsequently, the carbon abundance was increased according to

the C/O of the models. Abundances and ionisations of various

atoms and formed molecules for all layers of the atmospheric model were

calculated with equilibrium chemistry routines

(for a detailed discussion and an extensive list of

references we refer to Lederer & Aringer 2009). The

depletion of carbon in the gas phase due to consumption by dust grain

formation is also taken into account by the COMA code.

Examples for the resulting partial pressures can be found in

Fig. 5.

Subsequently, opacities for every radial depth point and the chosen

wavelength grid were computed. Several opacity sources were considered,

the most important one being the molecules for which the line profiles

are to be studied. Their contribution to the opacities were computed by

using line lists and under the following assumptions:

(i) conditions of LTE;

(ii) a microturbulence velocity of

0.02.

Subsequently, the carbon abundance was increased according to

the C/O of the models. Abundances and ionisations of various

atoms and formed molecules for all layers of the atmospheric model were

calculated with equilibrium chemistry routines

(for a detailed discussion and an extensive list of

references we refer to Lederer & Aringer 2009). The

depletion of carbon in the gas phase due to consumption by dust grain

formation is also taken into account by the COMA code.

Examples for the resulting partial pressures can be found in

Fig. 5.

Subsequently, opacities for every radial depth point and the chosen

wavelength grid were computed. Several opacity sources were considered,

the most important one being the molecules for which the line profiles

are to be studied. Their contribution to the opacities were computed by

using line lists and under the following assumptions:

(i) conditions of LTE;

(ii) a microturbulence velocity of  = 2.5 km s-1;

and (iii) line shapes described by Doppler profiles. Assuming

LTE conditions, level populations can be computed from

Boltzmann distributions at the corresponding gas temperature T.

The opacity

= 2.5 km s-1;

and (iii) line shapes described by Doppler profiles. Assuming

LTE conditions, level populations can be computed from

Boltzmann distributions at the corresponding gas temperature T.

The opacity

at a given frequency

at a given frequency  for a certain transition from state m to

state n can then be written as

for a certain transition from state m to

state n can then be written as

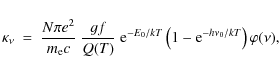

with the number density of relevant particles N, the charge e and mass me of the electron, the speed of light c, the Boltzmann constant k, and the energy of the respective radiation. The partition function Q(T)

is the weighted sum of all possible states. E0 represents

the excitation energy of the level m (from

ground state) and gf is the product of the

statistical weight g(m)

of the level times the oscillator strength f(m,n)

of the transition. Line lists usually contain frequencies

of the respective radiation. The partition function Q(T)

is the weighted sum of all possible states. E0 represents

the excitation energy of the level m (from

ground state) and gf is the product of the

statistical weight g(m)

of the level times the oscillator strength f(m,n)

of the transition. Line lists usually contain frequencies  (or in practice wavenumbers), excitation energies E0,

and gf values together with informations

for line identification. In order to reproduce the line shapes

in a realistic way, a broadening function

(or in practice wavenumbers), excitation energies E0,

and gf values together with informations

for line identification. In order to reproduce the line shapes

in a realistic way, a broadening function

for the line profile was introduced with

for the line profile was introduced with

(4)

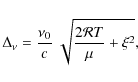

Only the effects of thermal broadening (first term in Eq. (6)) and the non-thermal contribution of microturbulent velocities (second term in Eq. (6)) are taken into account by COMA, whereas other effects (e.g. natural and pressure broadening, macroturbulence) are neglected. We refer to Sect. 2.2.2 of N05 for details. The resulting Doppler profiles can be described by a (Gaussian) broadening function

(5)

with a Doppler width given by

given by

where is the gas constant,

is the gas constant,  the

molecular weight, and

the

molecular weight, and  the microturbulent velocity. An updated set of references for

the line lists of all molecular species used by the current version of

COMA can be found in Lederer & Aringer (2009).

In this work we made use of the list of Goorvitch &

Chackerian (1994)

for CO and the CN line list of Jørgensen & Larsson (1990). We utilised

the same molecular lines as in Papers I and II, their

respective properties are summarised in Table 2.

In addition, molecules affecting the spectra

pseudo-continuously (mainly C2H2)

were considered by an opacity of constant value for the considered

spectral range (cf. Sect. 5.1 in Paper I

or N05). Furthermore, continuum absorption coefficients are

determined by COMA (Lederer & Aringer 2009)

as well as the opacity due to dust grains of amorphous carbon.

For the latter we used the data of Rouleau & Martin (1991;

set AC) and computed the resulting dust absorption

the microturbulent velocity. An updated set of references for

the line lists of all molecular species used by the current version of

COMA can be found in Lederer & Aringer (2009).

In this work we made use of the list of Goorvitch &

Chackerian (1994)

for CO and the CN line list of Jørgensen & Larsson (1990). We utilised

the same molecular lines as in Papers I and II, their

respective properties are summarised in Table 2.

In addition, molecules affecting the spectra

pseudo-continuously (mainly C2H2)

were considered by an opacity of constant value for the considered

spectral range (cf. Sect. 5.1 in Paper I

or N05). Furthermore, continuum absorption coefficients are

determined by COMA (Lederer & Aringer 2009)

as well as the opacity due to dust grains of amorphous carbon.

For the latter we used the data of Rouleau & Martin (1991;

set AC) and computed the resulting dust absorption![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) under the assumption of

the small particle limit of the Mie theory (grain sizes much

smaller than relevant wavelengths

under the assumption of

the small particle limit of the Mie theory (grain sizes much

smaller than relevant wavelengths  opacities proportional to the total amount of condensed material, but

independent of grain size distribution; cf. DMA3, Höfner

et al. 1992).

opacities proportional to the total amount of condensed material, but

independent of grain size distribution; cf. DMA3, Höfner

et al. 1992).

In the second step of the spectral synthesis, the previously calculated data array of opacities

for all depth and wavelengths points was utilised to solve the

radiative transfer (RT). As the thickness of the

line-forming region in AGB atmospheres is large compared to

the stellar radii, it is necessary to treat the RT in

spherical geometry. In addition, the complex velocity fields

(pattern of outflow and infall as for example shown in Fig. 4) in

AGB atmospheres severely affect the line shapes in the

resulting spectra (observed or synthetic, e.g. Fig. 12),

and it is essential to include the influence of relative macroscopic

velocities in this step of the spectral synthesis. Thus, a code for

solving spherical RT, which takes into account velocity

effects, is used to model line profiles and their variations.

The RT code used in this work (Windsteig 1998) follows the

numerical algorithm described in Yorke (1988).

for all depth and wavelengths points was utilised to solve the

radiative transfer (RT). As the thickness of the

line-forming region in AGB atmospheres is large compared to

the stellar radii, it is necessary to treat the RT in

spherical geometry. In addition, the complex velocity fields

(pattern of outflow and infall as for example shown in Fig. 4) in

AGB atmospheres severely affect the line shapes in the

resulting spectra (observed or synthetic, e.g. Fig. 12),

and it is essential to include the influence of relative macroscopic

velocities in this step of the spectral synthesis. Thus, a code for

solving spherical RT, which takes into account velocity

effects, is used to model line profiles and their variations.

The RT code used in this work (Windsteig 1998) follows the

numerical algorithm described in Yorke (1988).

It is necessary to choose spectral resolutions that are high enough to sample individual spectral lines with a sufficient number of wavelength points. This is especially important for synthesising the often quite complex line profiles for stars with pronounced atmospheric dynamics, like those that are the topic of this work. Therefore, all spectra are calculated with an extremely high resolution of R =

=

300 000 and were then rebinned to R =

70 000 for comparison with observed FTS spectra.

Furthermore, the synthetic spectra shown below were normalised relative

to a computation with only the continuous opacity taken into

account (F/

=

300 000 and were then rebinned to R =

70 000 for comparison with observed FTS spectra.

Furthermore, the synthetic spectra shown below were normalised relative

to a computation with only the continuous opacity taken into

account (F/

).

). Table 2: Different molecular features and the properties of the specific lines used for the line profile modelling here (and in Papers I and II).

Our aim is to infer information about atmospheric velocity fields from shifts in the wavelength of (components of) spectral lines. For this purpose, RVs were calculated by using the rest wavelength of the respective line and the formula for Doppler shift. For an easy comparison of our modelling results with observations, we adopted the naming convention for velocities of observational studies (positive for material moving away from the observer and negative for matter moving towards the observer). Thus, outflow from the star results in blue-shifted lines and negative RVs, while infalling matter revealed by red-shifted lines leads to positive RVs. In general, the RVs resulting from observations were combined into one composite lightcycle (

= 0.0-1.0)

and then plotted repeatedly for better illustration

(e.g. Fig. 14).

For the modelling we computed spectra and derived RVs throughout one

pulsation period (

= 0.0-1.0)

and then plotted repeatedly for better illustration

(e.g. Fig. 14).

For the modelling we computed spectra and derived RVs throughout one

pulsation period (

= 0.0-1.0)

and replicate the values beyond this interval

(e.g. Fig. 15).

= 0.0-1.0)

and replicate the values beyond this interval

(e.g. Fig. 15).

Following the convention of Papers I and II, bolometric phases

within the lightcycle in luminosity (Fig. 3a) will be

used throughout this work to characterise the modelling results

(atmospheric structures, synthetic spectra, derived RVs, etc.) with

numbers written in italics for a clear distinction

from the visual phases

within the lightcycle in luminosity (Fig. 3a) will be

used throughout this work to characterise the modelling results

(atmospheric structures, synthetic spectra, derived RVs, etc.) with

numbers written in italics for a clear distinction

from the visual phases

,

which are usually used to denote observational results (with

,

which are usually used to denote observational results (with  = 0

corresponding to phases of maximum light in the visual).

For a discussion of the relation between the two

types of phase informations, namely

= 0

corresponding to phases of maximum light in the visual).

For a discussion of the relation between the two

types of phase informations, namely

and

and

,

we refer to Appendix A.

,

we refer to Appendix A.

Throughout this work (e.g. the lower panel of Fig. 6 and all similar plots in the following), the radial optical depth

is computed by radially integrating inwards

is computed by radially integrating inwards![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) for a given wavelength point

for a given wavelength point

and is then plotted with dotted lines. For the opacities ,

all relevant sources (continuous, molecular/atomic, dust) are

included. If velocity effects are taken into account, optical

depths are calculated with the opacities at all depth points

Doppler-shifted according to the corresponding gas velocity there and

then plotted with solid lines. The optical depth of

,

all relevant sources (continuous, molecular/atomic, dust) are

included. If velocity effects are taken into account, optical

depths are calculated with the opacities at all depth points

Doppler-shifted according to the corresponding gas velocity there and

then plotted with solid lines. The optical depth of

1

provides clues on the approximate location of atmospheric layers where

radiation of a certain frequency

1

provides clues on the approximate location of atmospheric layers where

radiation of a certain frequency  (or the corresponding wavelength

(or the corresponding wavelength  )

originates.

)

originates.

3 Line formation in the extended atmospheres of evolved red giant stars

This section is concerned with the fact that different molecular spectral features visible in spectra of AGB stars originate at different atmospheric depths and the examination of this with numerical methods.

Typical main sequence stars exhibit relatively compact photospheres, and the radiation in different wavelengths originates at roughly the same geometrical atmospheric depths with a rather well defined temperature (e.g. Sect. 4.3.1 in GH04). For example, the relative thickness of the flux-forming region where the spectrum is produced in our Sun amounts to

4

4  10-4

(cf. N05). The often used parameter effective

temperature

10-4

(cf. N05). The often used parameter effective

temperature

represents a mean temperature in the layers of the thin photosphere,

from where almost all photons can escape.

represents a mean temperature in the layers of the thin photosphere,

from where almost all photons can escape. ![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11899fig05.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg88.png)

Figure 5: Upper panel: atmospheric structure of model S for the phase

=

0.0. Gas velocities

=

0.0. Gas velocities

are overplotted for illustration purposes (shock fronts). Compare

Figs. 1

and 9

in Paper I to get an idea of the temporal variations and also

for the scale of the gas velocities. The dotted line marks the border

between the actual model and the extension towards the interior for the

sake of optical depth (see text). Lower panel:

the total gas pressure together with the corresponding partial

pressures of selected molecules for this phase if chemical equilibrium

is assumed. Shown is only a subset of all molecular species considered

by COMA, which are CO, CN, C2, CH, C3,

C2H2, and HCN.

are overplotted for illustration purposes (shock fronts). Compare

Figs. 1

and 9

in Paper I to get an idea of the temporal variations and also

for the scale of the gas velocities. The dotted line marks the border

between the actual model and the extension towards the interior for the

sake of optical depth (see text). Lower panel:

the total gas pressure together with the corresponding partial

pressures of selected molecules for this phase if chemical equilibrium

is assumed. Shown is only a subset of all molecular species considered

by COMA, which are CO, CN, C2, CH, C3,

C2H2, and HCN.

Open with DEXTER In contrast, estimating the atmospheric extensions

in the case of AGB stars is much more difficult. The outer

boundaries of these objects are hard to define (as discussed

by GH04 in their Sect. 4.1) due to the shallow density

gradients related to the low surface gravities

in the case of AGB stars is much more difficult. The outer

boundaries of these objects are hard to define (as discussed

by GH04 in their Sect. 4.1) due to the shallow density

gradients related to the low surface gravities  ,

intensified by the dynamic processes of pulsation and mass loss.

GH04 give estimates of 0.1-0.5 for the

parameter

,

intensified by the dynamic processes of pulsation and mass loss.

GH04 give estimates of 0.1-0.5 for the

parameter

/

/ .

For the dynamic models used here (Sect. 2.2), one could

for example consider the region of dust formation at

.

For the dynamic models used here (Sect. 2.2), one could

for example consider the region of dust formation at  2

2  ,

where the onset of the stellar wind takes place

(cf. Fig. 4)

as an outer boundary of the atmosphere. This results in

,

where the onset of the stellar wind takes place

(cf. Fig. 4)

as an outer boundary of the atmosphere. This results in  /

/

1.

Whatever value one adopts, it is clear that the thickness of

an AGB atmosphere is of the same order as the stellar radius,

which is quite different from normal main sequence stars. With these

extremely extended atmospheres, the wavelength-dependent geometrical

radius can vary by a few 100

1.

Whatever value one adopts, it is clear that the thickness of

an AGB atmosphere is of the same order as the stellar radius,

which is quite different from normal main sequence stars. With these

extremely extended atmospheres, the wavelength-dependent geometrical

radius can vary by a few 100  (equivalent to a few AU) or more. Also the

related gas temperatures can cover a wide range from

(equivalent to a few AU) or more. Also the

related gas temperatures can cover a wide range from  5000 K

down to a few hundred Kelvin (N05).

5000 K

down to a few hundred Kelvin (N05). In general, molecular lines do not originate in a well-defined and narrow region, but are formed over a more or less wide range in radius. Nevertheless, there have been attempts to constrain the approximative line forming region in radius and temperature for different molecular features with similar dynamical model atmospheres as used here. The results - which should be regarded as rough estimates rather than definite borders, though - are compiled e.g. in Table 1.2 of N05. There are only a few molecular bands (e.g. CN or C2), which are solely formed in the deep, warm layers of the photosphere. Most of the strong features (e.g. H2O, HCN, C2H2) originate in the cool, upper layers of the atmosphere because of the small dissociation energies of the (polyatomic) molecules in combination with the high gf values. It is interesting that there are examples for bands formed in a relatively narrow region, as e.g. the ones of C3, which is due to the interplay between molecular formation and dissociation probabilities (Gautschy-Loidl 2001, Fig. 5). The special role of CO and the corresponding features will be discussed in detail below. To sum this up, the emerging spectrum (across the whole spectral range from the visual to the IR) of an AGB star is formed over a large radial range with diverse physical conditions, which is quite different from the scenario for the Sun as sketched above.

Moreover, not only spectral features of different molecules originate at varying radial atmospheric depths, but also different lines of the same molecular species can show this effect. This is especially pronounced in the case of CO lines and will be investigated below on the basis of one (arbitrarily chosen) phase of model S. The upper panel of Fig. 5 shows the corresponding atmospheric structure

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) at the phase

at the phase  = 0.0.

= 0.0.

There are a few factors that are decisive for the line intensities and for the locations (r,

)

of the line forming regions of molecular features in

AGB atmospheres:

)

of the line forming regions of molecular features in

AGB atmospheres: - i.

- the atmospheric structure itself (r-T-p);

- ii.

- the relative abundance (i.e. partial pressure) of the considered molecular species at certain depth points within the atmosphere (formation/depletion);

- iii.

- the properties of the respective line (excitation

energy

,

strength of the transition gf);

,

strength of the transition gf);

- iv.

- possibly other opacity sources (local continuous opacity, other molecular lines, dust opacity, pseudo-continuous molecular contributions);

- v.

- influence due to the relative macroscopic velocity fields.

i.) has substantial

impact on spectral features. Compared with hydrostatic model

atmospheres, dynamic models have enhanced densities in cool upper

layers (Fig. 4).

This results in a change of molecular abundance and decreased or

increased intensities of molecular features (as outlined in

Sects. 4.7.5 and 4.8.3.2 of GH04). Examples

for this effect would be the SiO bands at 4

i.) has substantial

impact on spectral features. Compared with hydrostatic model

atmospheres, dynamic models have enhanced densities in cool upper

layers (Fig. 4).

This results in a change of molecular abundance and decreased or

increased intensities of molecular features (as outlined in

Sects. 4.7.5 and 4.8.3.2 of GH04). Examples

for this effect would be the SiO bands at 4  m

(Fig. 5

of Aringer 1999),

the H2O bands around 3

m

(Fig. 5

of Aringer 1999),

the H2O bands around 3  m

(Fig. 9

in DMA3), or the combined feature of C2H2

and CN at

m

(Fig. 9

in DMA3), or the combined feature of C2H2

and CN at  14

14  m

(Sect. 4 of DMA4).

m

(Sect. 4 of DMA4).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.7cm,clip]{11899fig06.ps}\vspace*{3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg93.png)

Figure 6: Radial distribution of absorption per mol of the molecular material ( upper panel), absorption coefficient (centre panel) and the optical depths (see text for detailed discussion) for the molecular lines chosen for the line profile modelling as listed in Table 2, calculated on the basis of the atmospheric structure shown in the upper panel of Fig. 5. For the absorptions ( upper and middle panel) only the contribution of the respective lines are plotted, while all relevant opacity sources (cf. Eq. (7)) are taken into account for the optical depths ( lower panel). Note that the effects of gas velocities (Doppler-shifts) are not taken into account for the computation of the optical depths.

Open with DEXTER The lower panel of Fig. 5 demonstrates the differences in relative abundance (

ii.) for various

molecules throughout the whole atmosphere. Plotted are the partial

pressures for different molecular species resulting from the evaluation

under the assumption of chemical equilibrium by the COMA code.

CN is a typical representative for species

which form in deep photospheric layers below

ii.) for various

molecules throughout the whole atmosphere. Plotted are the partial

pressures for different molecular species resulting from the evaluation

under the assumption of chemical equilibrium by the COMA code.

CN is a typical representative for species

which form in deep photospheric layers below  1.5

1.5  .

Values of 2400-5000 K for the gas temperatures in the line

forming regions were assigned to this species by Gautschy-Loidl (2001).

In contrast, C2H2 shows

a quite different behaviour. As they are very sensitive to

temperature (dissociation), these molecules can be found from

.

Values of 2400-5000 K for the gas temperatures in the line

forming regions were assigned to this species by Gautschy-Loidl (2001).

In contrast, C2H2 shows

a quite different behaviour. As they are very sensitive to

temperature (dissociation), these molecules can be found from  1.2

1.2  on outwards, Gautschy-Loidl lists temperatures of

<2400 K. C3 represents

a fairly extreme example. Its formation requires at the same

time high densities for high enough collision probabilities with low

temperatures in order not to dissociate. This is met only in a rather

narrow region around temperatures of 2000 K. The density

variations due to the propagating shock wave (for this phase

at a radius slightly larger than 1

on outwards, Gautschy-Loidl lists temperatures of

<2400 K. C3 represents

a fairly extreme example. Its formation requires at the same

time high densities for high enough collision probabilities with low

temperatures in order not to dissociate. This is met only in a rather

narrow region around temperatures of 2000 K. The density

variations due to the propagating shock wave (for this phase

at a radius slightly larger than 1  )

also are of importance, as can be seen in the partial

pressures. From

)

also are of importance, as can be seen in the partial

pressures. From  0.8

0.8  inwards the abundances of all species decrease as molecules are

dissociated for temperatures higher than 5000 K.

inwards the abundances of all species decrease as molecules are

dissociated for temperatures higher than 5000 K.

Figure 5 illustrates also that CO is an outstanding molecular species concerning its relative abundance. Due to its high dissociation energy (11.1 eV), CO is stable and the most abundant species (of those shown; not included in this figure is e.g. the by far most abundant molecular species H

)

at all depth points of the atmospheric model. For some

molecules - like CN or even more C3 -

the limited range with significant large partial pressures sets

constraints on the line forming region. However, CO is present

and abundant across the whole atmosphere, and the properties of

individual spectral lines (

)

at all depth points of the atmospheric model. For some

molecules - like CN or even more C3 -

the limited range with significant large partial pressures sets

constraints on the line forming region. However, CO is present

and abundant across the whole atmosphere, and the properties of

individual spectral lines (

iii.), namely the

excitation energy

iii.), namely the

excitation energy

and the strength of the transition gf,

become important. The excitation energy E0

of the lower level of a certain transition m

and the strength of the transition gf,

become important. The excitation energy E0

of the lower level of a certain transition m

n

determines at which temperatures (i.e. atmospheric depths) the

levels are populated so that an absorption can occur at all.

In addition, the strength of the transition (gf-value)

determines the intensity of the line and thus also the atmospheric

depth were

n

determines at which temperatures (i.e. atmospheric depths) the

levels are populated so that an absorption can occur at all.

In addition, the strength of the transition (gf-value)

determines the intensity of the line and thus also the atmospheric

depth were

1

is reached. Compare Sect. 2.4 and

Eq. (3)

in this context. Also the relative abundance is present in this

equation by the quantity N.

1

is reached. Compare Sect. 2.4 and

Eq. (3)

in this context. Also the relative abundance is present in this

equation by the quantity N.

To study these effects for the lines chosen for our line profile modelling (cf. Table 2, Fig. 8), we used the atmospheric structure shown in Fig. 5 and calculated different quantities. Note that velocity effects were neglected for all subsequent computations of this subsection. The results are plotted in Fig. 6. The upper panel of this plot shows the molecular absorption (absorption per mol of the material of the corresponding molecular species), illustrating how one individual molecule of a given species would absorb radiation of the wavelength of the corresponding line at all atmospheric depth points. Level populations are computed by Boltzmann distributions for the respective temperature (LTE). The increasing gf values from second overtone (

= 3)

to first overtone (

= 3)

to first overtone ( = 2)

and to fundamental (

= 2)

and to fundamental ( = 1)

CO lines (cf. Fig. 8) are

reflected in the increasing molecular absorption. The middle panel of

Fig. 6

shows the actual absorption coefficient (absorption per gram of the

whole stellar material) due to the respective molecular line, where the

relative abundance of the species comes in. This can be

recognised by the decrease for all

= 1)

CO lines (cf. Fig. 8) are

reflected in the increasing molecular absorption. The middle panel of

Fig. 6

shows the actual absorption coefficient (absorption per gram of the

whole stellar material) due to the respective molecular line, where the

relative abundance of the species comes in. This can be

recognised by the decrease for all  values

with higher temperatures or the steep decrease for the CN line

below 2000 K where the partial pressure of CN

severely drops (Fig. 5).

Plotted in the middle panel is the opacity due to the CO or

CN lines only. In combination with all other contributions

(continuous, other molecular species, dust;

values

with higher temperatures or the steep decrease for the CN line

below 2000 K where the partial pressure of CN

severely drops (Fig. 5).

Plotted in the middle panel is the opacity due to the CO or

CN lines only. In combination with all other contributions

(continuous, other molecular species, dust;

iv.), these

opacities serve as input for the RT or can be used to calculate radial

optical depths as shown in the lower panel of Fig. 6. The

quantities

iv.), these

opacities serve as input for the RT or can be used to calculate radial

optical depths as shown in the lower panel of Fig. 6. The

quantities

and

and

for the central/rest wavelength of the respective lines

(cf. line profiles in Fig. 12

plotted grey) are shown here, no velocity effects are taken

into account. It can clearly be seen that

for the central/rest wavelength of the respective lines

(cf. line profiles in Fig. 12

plotted grey) are shown here, no velocity effects are taken

into account. It can clearly be seen that

1

is reached in a wide temperature range between

1

is reached in a wide temperature range between  300 K and

300 K and  3000 K,

corresponding to

3000 K,

corresponding to

10-20

10-20

23-46 AU in this case. While for the CN line the

limited region of high enough partial pressure and

the line parameters are crucial for the line formation, only the latter

is relevant for CO lines. Different rotation-vibration band

systems of CO originate in quite separated regions within the stellar

atmosphere. Therefore and because of other important effects

(cf. Sect. 2.2 of Paper I), the spectral

lines of CO play a major role in the research on

AGB atmospheres, especially for kinematic studies.

23-46 AU in this case. While for the CN line the

limited region of high enough partial pressure and

the line parameters are crucial for the line formation, only the latter

is relevant for CO lines. Different rotation-vibration band

systems of CO originate in quite separated regions within the stellar

atmosphere. Therefore and because of other important effects

(cf. Sect. 2.2 of Paper I), the spectral

lines of CO play a major role in the research on

AGB atmospheres, especially for kinematic studies. The contributions of different opacity sources to the resulting radial optical depths are illustrated in Fig. 7 for the model atmosphere used (Fig. 5). The upper panel of this plot shows that the strong fundamental CO line is the dominant source at its central/rest wavelength over almost the whole extended atmosphere. Only in the hot layers below the photosphere the continuous opacity takes over, while the dust plays a neglectable role in general. The panel below shows the same quantities for the chosen second overtone CO line. Because of its properties (lower gf value and higher

lower line intensity compared to the

lower line intensity compared to the  = 1 line;

cf. the spectrum in Fig. 8), this

molecular line provides the main contribution to the total optical

depth only in the layers of

= 1 line;

cf. the spectrum in Fig. 8), this

molecular line provides the main contribution to the total optical

depth only in the layers of  2-4000 K. From

2-4000 K. From  5000 K

inwards the continuous opacity represents the major source again,

although to a somewhat lower extent (minimum of absorption due to the H- ion

around 1.6

5000 K

inwards the continuous opacity represents the major source again,

although to a somewhat lower extent (minimum of absorption due to the H- ion

around 1.6  m;

e.g. GH04) compared to the former case (

m;

e.g. GH04) compared to the former case ( 4.65

4.65  m). On the

other hand, the absorption due to grains of amorphous carbon dust is

stronger in the wavelength region of CO

m). On the

other hand, the absorption due to grains of amorphous carbon dust is

stronger in the wavelength region of CO  = 3 lines

(cf. Fig. 1 of

Andersen et al. 1999)

as reflected in the dust optical depths. Still, the absorption

features are visible in the synthetic spectra because of the moderate

mass loss of the used model S (Table 1). This

changes for higher mass loss rates, the intensities of molecular

features decrease as the corresponding line forming regions are hidden

by optically thick dust shells.

= 3 lines

(cf. Fig. 1 of

Andersen et al. 1999)

as reflected in the dust optical depths. Still, the absorption

features are visible in the synthetic spectra because of the moderate

mass loss of the used model S (Table 1). This

changes for higher mass loss rates, the intensities of molecular

features decrease as the corresponding line forming regions are hidden

by optically thick dust shells.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11899fig07.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg96.png)

Figure 7: Same as bottom panel of Fig. 6, the individual contributions of different opacity sources (continuous, molecular line, dust) to the radial optical depth (cf. Eq. (7)) for two of the CO lines used in this study (Table 2) are shown in addition.

Open with DEXTER ![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{11899fig08.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg97.png)

Figure 8: Characteristic properties excitation energy and gf value of several lines of the CO

=

3/2/1 bands are shown in the upper and middle panel.

Plotted in each case are lines of the same rotational transition but

from different vibrational bands (meaning for example 1-0 R1,

2-1 R1, 3-2 R1, ..., 21-20 R1). The strong

variations in

=

3/2/1 bands are shown in the upper and middle panel.

Plotted in each case are lines of the same rotational transition but

from different vibrational bands (meaning for example 1-0 R1,

2-1 R1, 3-2 R1, ..., 21-20 R1). The strong

variations in

and gf from one vibrational band to another

influence the results shown in Fig. 6 and

lead to distinct different line intensities. This is illustrated in the

lower panel with a spectrum (frequency times specific

luminosity vs. wavelength) based on the atmospheric model of

Fig. 5

where only the respective lines are taken into account. Marked with the

same colour-code as Fig. 6 are the

lines actually used for the line profile modelling (as listed

in Table 2).

and gf from one vibrational band to another

influence the results shown in Fig. 6 and

lead to distinct different line intensities. This is illustrated in the

lower panel with a spectrum (frequency times specific

luminosity vs. wavelength) based on the atmospheric model of

Fig. 5

where only the respective lines are taken into account. Marked with the

same colour-code as Fig. 6 are the

lines actually used for the line profile modelling (as listed

in Table 2).

Open with DEXTER ![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.4cm,clip]{11899fig09.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/06/aa11899-09/Timg98.png)

Figure 9: Same as bottom panel of Fig. 6 but for the large number of CO

=

3/2/1 lines as shown in Fig. 8. Plotted

with thick linestyle are the CO lines that were actually used

for the line profile modelling (Fig. 6).

=

3/2/1 lines as shown in Fig. 8. Plotted

with thick linestyle are the CO lines that were actually used

for the line profile modelling (Fig. 6).

Open with DEXTER Figure 8 illustrates that the same type of CO lines (fundamental, first or second overtone), but from different vibrational bands can have very different values of

and gf. Not only leading to

variations in line intensities (lower panel), it also has a

strong impact on the absorption coefficients and optical depths as

discussed above. This is demonstrated in Fig. 9, where

the radial optical depths are plotted for the variety of lines from

different vibrational bands used for Fig. 8.

Going to higher vibrational quantum numbers leads to weaker

lines and line formation regions located at higher

temperatures (

and gf. Not only leading to

variations in line intensities (lower panel), it also has a

strong impact on the absorption coefficients and optical depths as

discussed above. This is demonstrated in Fig. 9, where

the radial optical depths are plotted for the variety of lines from

different vibrational bands used for Fig. 8.

Going to higher vibrational quantum numbers leads to weaker

lines and line formation regions located at higher

temperatures (

), i.e. further

inside the atmosphere. One may suppose that these differences should

also be reflected in the dynamic effects (line profile variations,

derived RVs) if other lines than those used for our line profile

modelling (Table 2;

chosen to be similar to observational studies) are considered.

), i.e. further

inside the atmosphere. One may suppose that these differences should

also be reflected in the dynamic effects (line profile variations,

derived RVs) if other lines than those used for our line profile

modelling (Table 2;

chosen to be similar to observational studies) are considered.

The remaining factor (

v.) concerning the

line formation process, namely the important point of the influence of

velocity fields, will be the main issue in the next sections. Velocity

effects are most relevant for line profiles in spectra of evolved red

giants.

v.) concerning the

line formation process, namely the important point of the influence of

velocity fields, will be the main issue in the next sections. Velocity

effects are most relevant for line profiles in spectra of evolved red

giants.

4 The influence of velocity fields