| Issue |

A&A

Volume 519, September 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A19 | |

| Number of page(s) | 7 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201014829 | |

| Published online | 07 September 2010 | |

Fitting formulae of the reduced-shear power spectrum for weak lensing![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) (Research Note)

(Research Note)

M. Kilbinger1,2,3

1 -

Excellence Cluster Universe, Technische Universität München,

Boltzmannstr. 2, 85748 Garching, Germany

2 -

Universitäts-Sternwarte München, Scheinerstr. 1, 81679 München, Germany

3 -

Shanghai Key Lab for Astrophysics, Shanghai Normal University,

Shanghai 200234, PR China

Received 20 April 2010 / Accepted 9 June 2010

Abstract

Context. Weak gravitational lensing is a powerful probe of

large-scale structure and cosmology. Most commonly, second-order

correlations of observed galaxy ellipticities are expressed as a

projection of the matter power spectrum, corresponding to the

lowest-order approximation between the projected and the

three-dimensional power spectrum.

Aims. The dominant lensing-only contribution beyond the

zero-order approximation is the reduced shear, which takes into account

not only lensing-induced distortions but also the isotropic

magnification of galaxy images. This involves an integral over the

matter bispectrum. We provide a fast and general way to calculate this

correction term.

Methods. Using a model for the matter bispectrum, we fit

elementary functions to the reduced-shear contribution and its

derivatives with respect to cosmological parameters. The dependence on

cosmology is encompassed in a Taylor-expansion around a fiducial model.

Results. Within a region in parameter space comprising the WMAP7

68% error ellipsoid, the total reduced-shear power spectrum (shear plus

fitted reduced-shear correction) is accurate to 1% (2%) for ![]() (

(

![]() ).

This corresponds to a factor of four reduction in the bias compared to

the case where no correction is used. This precision is necessary to

match the accuracy of current non-linear power spectrum predictions

from numerical simulations.

).

This corresponds to a factor of four reduction in the bias compared to

the case where no correction is used. This precision is necessary to

match the accuracy of current non-linear power spectrum predictions

from numerical simulations.

Key words: gravitational lensing: weak - large-scale structure of Universe

1 Introduction

Cosmic shear surveys exploit the distortions of distant galaxy images

induced by the matter structures in the Universe on large scales. Weak

cosmological lensing has become an important tool to measure

cosmological parameters. The current precision in the measured shapes

of high-redshift galaxies is at the few percent level providing

important constraints on the matter density

![]() and the

power-spectrum normalisation

and the

power-spectrum normalisation ![]() .

Future surveys aim to achieve

sub-percent level accuracy in measuring dark-energy properties or

deviations from general relativity.

.

Future surveys aim to achieve

sub-percent level accuracy in measuring dark-energy properties or

deviations from general relativity.

To reach this precision for cosmological parameters, efforts not only on the observational but also on the theoretical side have to be made. To predict the shear power spectrum from theoretical models, several approximations are usually made to facilitate calculations. When comparing and fitting models to observations, these simplifications can significantly bias the resulting cosmological parameters. One of these approximations is to neglect the correction due to the so-called reduced shear.

The observed ellipticity of galaxies is an estimator of the

reduced shear

where

The effect of reduced shear was examined using N-body

simulations by White (2005) and compared with theoretical predictions

in Dodelson et al. (2006). Corrections to the lensing skewness

were discussed in Schneider et al. (1998) and

Dodelson & Zhang (2005).

An extensive study of

higher-order corrections to the weak-lensing power spectrum, including

reduced shear, was presented by Krause & Hirata (2009). Compared

with corrections due to light-path integration (relaxation of the Born

approximation) and lens-lens coupling

(e.g., Bernardeau et al. 1997; Seitz 1993), reduced-shear

corrections represent the dominant contribution to the weak-lensing

power spectrum. The lowest-order correction term, which is of order

![]() in the gravitational potential

in the gravitational potential ![]() ,

reaches 10%

of the total lensing spectrum. This is the term that we consider

in this work. The next-order correction at

,

reaches 10%

of the total lensing spectrum. This is the term that we consider

in this work. The next-order correction at

![]() is one

magnitude below the

is one

magnitude below the

![]() -term (Krause & Hirata 2009).

Ignoring reduced shear will cause a bias in cosmological parameters,

which is comparable to the statistical error from future surveys like

DES

-term (Krause & Hirata 2009).

Ignoring reduced shear will cause a bias in cosmological parameters,

which is comparable to the statistical error from future surveys like

DES![]() , LSST

, LSST![]() ,

or Euclid

,

or Euclid![]() (Shapiro 2009). For the weak-lensing results of

the COSMOS survey

(Shapiro 2009). For the weak-lensing results of

the COSMOS survey![]() , an estimate from

numerical simulations yielded a 1% underestimation of

, an estimate from

numerical simulations yielded a 1% underestimation of ![]() (Schrabback et al. 2010).

(Schrabback et al. 2010).

Another correction to weak lensing from a magnitude-limited galaxy sample is the so-called magnification bias. Hamana (2001) found its contribution to the lensing power spectrum to be small. The corresponding third-order correction terms were also calculated and compared to numerical simulations by Ménard et al. (2003). However, if not corrected for, future surveys will yield significantly biased cosmological parameter constraints (Schmidt et al. 2009a). The lowest-order correction term has the same functional form as the reduced-shear one, and therefore both can be dealt with simultaneously. Higher-order terms contribute by smaller than one percent to the lensing power spectrum (Krause & Hirata 2009).

There are additional important sources of contamination to the weak lensing observables, some of which may be larger than the reduced-shear corrections. These involve galaxy clustering, the intrinsic alignment of galaxies with each other or with the surrounding dark matter haloes, and the modelling of the non-linear dark-matter power spectrum and baryonic processes. The modelling of these effects requires detailed understanding of baryonic physics, galaxy formation, the interplay between galaxies and dark matter, and massive numerical simulations in the case of the non-linear power spectrum. In contrast, taking into account the reduced shear is straightforward and can be done with sufficient accuracy to render it a sub-dominant contamination.

In the next section, we review the expressions for the lowest-order reduced-shear term, and introduce a fitting scheme to efficiently model this term. In Sect. 3, we present our results, demonstrating the accuracy of the fits. We conclude this paper in Sect. 4.

2 Reduced shear

2.1 Lowest-order expansion

For small values of the convergence,

![]() ,

the reduced

shear (1) is expanded as

,

the reduced

shear (1) is expanded as

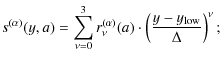

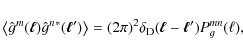

To calculate the power spectrum of the reduced shear g, we apply a Fourier transform to Eq. (2) to second order

| (3) |

In our notation, the convolution of

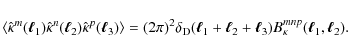

We assume that the reduced shear is measured in redshift bins. With Pgmn, we denote the reduced-shear (cross-)power spectrum for two redshift bins with indices m and n. In general, the shear field can be decomposed into an E-mode (gradient) and a B-mode (curl). However, as is the case for cosmic shear at lowest order, the reduced-shear correction of order

where gm denotes the reduced shear measured from galaxies in the mth redshift bin, the asterisk (*) denotes complex conjugation, and

The reduced-shear power spectrum is the sum of the convergence power spectrum (which equals the shear power spectrum) and a correction given by

Using the relation between shear and convergence,

With this, we derive the correction term

Without loss of generality, we have set

The convergence bispectrum can be expressed in terms of the three-dimensional matter

bispectrum ![]() using Limber's equation

(Limber 1953; Kaiser 1992) providing

using Limber's equation

(Limber 1953; Kaiser 1992) providing

The lower limit of the integral over the scale factor a corresponds to the limiting redshift,

![\begin{displaymath}G^m(a) = \frac 3 2 \left(\frac{H_0}c\right)^2 \frac{\Omega_{\...

...me) \frac{f_K[\chi(a^\prime) - \chi(a)]}{f_K[\chi(a^\prime)]},

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14829-10/img47.png)

|

(11) |

which includes an integral over the probability distribution pm of the number density of source galaxies in the mth bin.

2.2 Expansion around a fiducial model

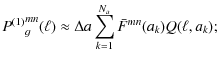

In the expressions needed to calculate the first-order reduced-shear power spectrum

in Eqs. (9, 10), we can interchange the ![]() - and the

a-integration, and replace the latter by a finite sum. Then

- and the

a-integration, and replace the latter by a finite sum. Then

Evaluating the

Table 1:

Parameter limits for where the accuracy of the fitted

reduced-shear power spectrum is better than ![]() for

for ![]() ,

and better than

,

and better than ![]() for

for

![]() (see also

Fig. 3).

(see also

Fig. 3).

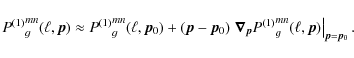

We perform a Taylor-expansion to first order

P(1)mng as a function of a cosmological

parameter vector

![]() around a fiducial cosmological model with

parameter

around a fiducial cosmological model with

parameter ![]()

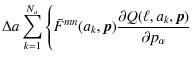

Inserting Eq. (12), the derivatives with respect to cosmological parameters are given by

In Sect. 3, we consider the cosmological parameters

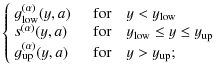

2.3 Magnification and size bias

A typical galaxy sample used in weak cosmological lensing is selected

by both magnitude and galaxy size. Magnification due to lensing

changes both quantities (e.g. Bartelmann & Schneider 2001), and therefore introduces

a correlation between number density and convergence. If the number

density of galaxies with fluxes higher than some flux S, and sizes

larger than some size R can be written as power laws,

|

(15) |

the observed number density differs from the unlensed one p0to first order, becoming

| (16) |

according to Schmidt et al. (2009b,a). This simple linear model assumes that the galaxy selection function depends on flux and size in a separable way. We refer to Wyithe et al. (2003) for a generalisation that takes into account correlations between the two quantities.

Magnification and size bias induces a lowest-order correction to the

lensing power spectrum which has the same form as for reduced

shear. Therefore, we can add the corresponding correction term

![]() to Eq. (6) with

to Eq. (6) with

|

|||

| (17) |

where the function Q is given in Eq. (12).

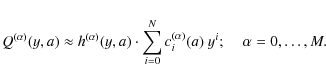

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14829Fg1}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14829-10/Timg69.png)

|

Figure 1:

The function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

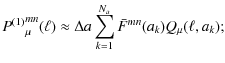

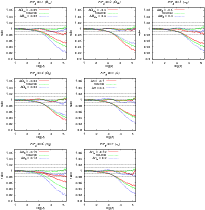

Figure 2:

Fit coefficients as a function of scale factor.

Left: the polynomial fit coefficients c(0)i for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

|

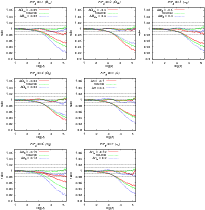

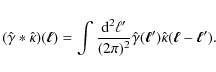

Figure 3:

The fitted reduced-shear power spectrum (thick lines) and

the uncorrected convergence power spectrum (thin lines). Both

quantities are plotted as ratios with respect to the reduced-shear

power spectrum (6), where the first-order correction

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.4 Fitting formulae

For simplicity, we define

Q(0) = Q and

![]() for

for

![]() .

These correspond to the

.

These correspond to the ![]() -dependent terms in

Eqs. (12) and (14), which behave as near-power laws for

both small and large

-dependent terms in

Eqs. (12) and (14), which behave as near-power laws for

both small and large ![]() .

With the abbreviation

.

With the abbreviation

![]() ,

we

perform two linear fits of

,

we

perform two linear fits of

![]() for

for

![]() and

and

![]() ,

respectively.

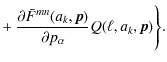

We smoothly piece together these two asymptotic functions with a cubic

spline

,

respectively.

We smoothly piece together these two asymptotic functions with a cubic

spline

![]() such that the composite function

such that the composite function

![]() and its first derivative are continuous

and its first derivative are continuous

for the linear functions

| (19) |

and the cubic spline

|

|||

| (20) |

The ratios

We note that we cannot fit the logarithm of the functions

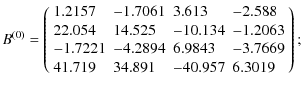

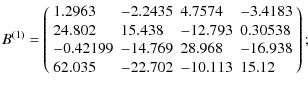

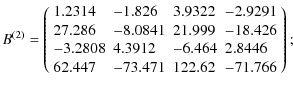

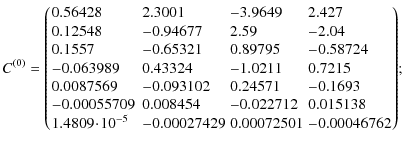

The fit coefficients

![]() are expected to

smoothly vary with the scale factor a. We therefore perform another series

of fits by polynomials of order Nb and Nc, respectively

are expected to

smoothly vary with the scale factor a. We therefore perform another series

of fits by polynomials of order Nb and Nc, respectively

The two matrices

3 Results

We use a fiducial flat ![]() CDM cosmological model with WMAP7-like

parameters,

CDM cosmological model with WMAP7-like

parameters,

![]() and

and

![]() (Komatsu et al. 2010). The dark-matter bispectrum is calculated

according to Scoccimarro & Couchman (2001). Their fitting formula is

accurate to only 30-50% on small scales; this is however

sufficient for our purpose. We note also that the bispectrum is not

calibrated for any dark-energy model other than

(Komatsu et al. 2010). The dark-matter bispectrum is calculated

according to Scoccimarro & Couchman (2001). Their fitting formula is

accurate to only 30-50% on small scales; this is however

sufficient for our purpose. We note also that the bispectrum is not

calibrated for any dark-energy model other than ![]() CDM. For the

matter power spectrum, we use the ``halofit'' fitting formula of

Smith et al. (2003) and the transfer function ``shape fit''

from Eisenstein & Hu (1998). Following the icosmo.org code

(Refregier et al. 2008) for models with

CDM. For the

matter power spectrum, we use the ``halofit'' fitting formula of

Smith et al. (2003) and the transfer function ``shape fit''

from Eisenstein & Hu (1998). Following the icosmo.org code

(Refregier et al. 2008) for models with ![]() ,

we

modify ``halofit'' to interpolate between

,

we

modify ``halofit'' to interpolate between ![]() CDM and w=-1/3,

which behaves in a similar way to an OCDM model (for

more details, see Schrabback et al. 2010).

CDM and w=-1/3,

which behaves in a similar way to an OCDM model (for

more details, see Schrabback et al. 2010).

The function Q and the corresponding fit with the composite function

given in Eq. (21) are shown in Fig. 1. The polynomial that

is part of the composite function has order N=6. The fitting

coefficients b(0)i and ci(0) are plotted in

Fig. 2. Although the higher-order polynomial

coefficients have relatively low amplitudes (right panel), we found that a

polynomial of order 6 is necessary to provide a good fit to the

reduced-shear power spectrum, as discussed below. For the

polynomial fits of the coefficients as functions of a (22), we chose

Nb = Nc = 3. These

cubic polynomials provide sufficient accuracy, in particular

for

![]() ,

where the coefficients show the most

variation. This is important because the reduced-shear correction

spectrum in Eq. (12) obtains a large contribution from large a.

,

where the coefficients show the most

variation. This is important because the reduced-shear correction

spectrum in Eq. (12) obtains a large contribution from large a.

We perform the fits in the ![]() -range between 0.1 and

-range between 0.1 and

![]() .

The functions

.

The functions

![]() are not perfect power laws,

therefore the fit for large

are not perfect power laws,

therefore the fit for large ![]() is not excellent. We found an

improvement of our final results for the total power spectrum by

adding 0.05 to b2 after performing the fits.

is not excellent. We found an

improvement of our final results for the total power spectrum by

adding 0.05 to b2 after performing the fits.

The fitting functions for the reduced-shear power spectrum corrections

provide accurate results over a wide range in ![]() .

We illustrate

the case of a single redshift bin with distribution

.

We illustrate

the case of a single redshift bin with distribution

![]() and parameters

and parameters

![]() ,

and z0 = 0.5. The maximum considered redshift is

,

and z0 = 0.5. The maximum considered redshift is

![]() ,

which results in a mean redshift of 0.75.

At

,

which results in a mean redshift of 0.75.

At

![]() the reduced-shear correction to the

convergence power spectrum starts to become important. On smaller

scales, the latter underestimates the total power spectrum by more

than 1%. For

the reduced-shear correction to the

convergence power spectrum starts to become important. On smaller

scales, the latter underestimates the total power spectrum by more

than 1%. For

![]() ,

we fit

,

we fit

![]() (Eq. (7)) to better than 20%. This is sufficient to provide an

approximation of the total power spectrum at the percent-level.

(Eq. (7)) to better than 20%. This is sufficient to provide an

approximation of the total power spectrum at the percent-level.

In Fig. 3, we the plot the ratio of the reduced-shear power

spectrum derived using our fitting functions to that obtained by numerical

integration of Eq. (12). This is compared to the case of no

correction for reduced-shear, corresponding to just the convergence

power spectrum. In this latter power spectrum, a downward bias is evident, since

the power is underestimated. This bias increases from 1% at

![]() to 6% at

to 6% at

![]() for the fiducial

cosmology. In models with more structure, this bias is larger,

e.g., 8% for

for the fiducial

cosmology. In models with more structure, this bias is larger,

e.g., 8% for

![]() .

In contrast, our fitted correction is

accurate to better than 1% for

.

In contrast, our fitted correction is

accurate to better than 1% for

![]() at the fiducial

point.

at the fiducial

point.

We test different redshift distributions by changing to z0 = 0.3 and z0 = 0.7, corresponding to mean redshifts of 0.45 and 1, respectively, and also a redshift bin of width 0.1 around z=0.75. In all cases, the fitting formula remains accurate to within 1% at the fidicual model.

In Table 1, we denote the parameter ranges for which our

fitting formulae are accurate to better than ![]() for

for ![]() ,

and better than

,

and better than ![]() for

for

![]() .

.

4 Conclusions

The lowest-order correction term for the reduced-shear power spectrum

is the dominant contribution from lensing-only effects

(Krause & Hirata 2009). This term is proportional to the third

power of the gravitational potential ![]() ,

and includes an integral

over the lensing bispectrum. In this paper, we have presented fitting

formulae for this integral and its derivative with respect to

cosmological parameters. This has permitted a more efficient

calculation of the reduced-shear correction power spectrum within a

parameter range comprising the 68% confidence region of

WMAP7. The fitting scheme reduces the computational effort from tens

of minutes for the full integration to a fraction of a second.

,

and includes an integral

over the lensing bispectrum. In this paper, we have presented fitting

formulae for this integral and its derivative with respect to

cosmological parameters. This has permitted a more efficient

calculation of the reduced-shear correction power spectrum within a

parameter range comprising the 68% confidence region of

WMAP7. The fitting scheme reduces the computational effort from tens

of minutes for the full integration to a fraction of a second.

For currently available weak-lensing data, the uncertainty in the non-linear power spectrum on small scales is still larger than the bias due to the reduced-shear. For example, the widely-used fitting prescription by Smith et al. (2003) strongly underestimates the power on small scales. More recent numerical simulations however provide fitting formulae that improve the accuracy by a factor 5 to 10 (Heitmann et al. 2009; Lawrence et al. 2010; Heitmann et al. 2008). Moreover, their emulation scheme can be applied to a wide range of cosmological parameters. This range is comprised in the hypercube for which our fits are valid. In combination, these results provide us with predictions for the weak lensing power spectrum that are accurate to the few percent level.

AcknowledgementsWe thank Peter Schneider for helpful comments on the manuscript, and the anonymous referee whose suggestions helped to improve the paper. This research was supported by the DFG cluster of excellence Origin and Structure of the Universe and the Chinese National Science Foundation Nos. 10878003 and 10778725, 973 Program No. 2007CB 815402, Shanghai Science Foundations and Leading Academic Discipline Project of Shanghai Normal University (DZL805).

References

- Bartelmann, M., & Schneider, P. 2001, Phys. Rep., 340, 297

- Bernardeau, F., Van Waerbeke, L., & Mellier, Y. 1997, A&A, 322, 1

- Dodelson, S., & Zhang, P. 2005, Phys. Rev. D, 72, 083001

- Dodelson, S., Shapiro, C., & White, M. 2006, Phys. Rev. D, 73, 023009

- Eisenstein, D. J., & Hu, W. 1998, ApJ, 496, 605

- Hamana, T. 2001, MNRAS, 326, 326

- Heitmann, K., Higdon, D., White, M., et al. 2009, ApJ, 705, 156

- Heitmann, K., White, M., Wagner, C., Habib, S., & Higdon, D. 2008, ApJ, 715, 104

- Kaiser, N. 1992, ApJ, 388, 272

- Komatsu, E., Smith, K. M., Dunkley, J., et al. 2010, ApJS, submitted, [arXiv:1001.4538]

- Krause, E., & Hirata, C. M. 2009, A&A, accepted, [arXiv:0910.3786]

- Lawrence, E., Heitmann, K., White, M., et al. 2010, ApJ, 713, 1322

- Limber, D. N. 1953, ApJ, 117, 134

- Ménard, B., Hamana, T., Bartelmann, M., & Yoshida, N. 2003, A&A, 403, 817

- Refregier, A., Amara, A., Kitching, T., & Rassat, A. 2008, A&A, submitted, [arXiv:0810.1285]

- Schmidt, F., Rozo, E., Dodelson, S., Hui, L., & Sheldon, E. 2009a, ApJ, 702, 593

- Schmidt, F., Rozo, E., Dodelson, S., Hui, L., & Sheldon, E. 2009b, Phys. Rev. Lett., 103, 051301

- Schneider, P., Van Waerbeke, L., Jain, B., & Kruse, G. 1998, MNRAS, 296, 873

- Schneider, P., Van Waerbeke, L., & Mellier, Y. 2002, A&A, 389, 729

- Schrabback, T., Hartlap, J., Joachimi, B., et al. 2010, A&A, 516, A63

- Scoccimarro, R., & Couchman, H. M. P. 2001, MNRAS, 325, 1312

- Seitz, S. 1993, in Liege International Astrophysical Colloquia, ed. J. Surdej, D. Fraipont-Caro, E. Gosset, S. Refsdal, & M. Remy, 31, 579

- Shapiro, C. 2009, ApJ, 696, 775

- Smith, R. E., Peacock, J. A., Jenkins, A., et al. 2003, MNRAS, 341, 1311

- White, M. 2005, Astropart. Phys., 23, 349

- Wyithe, J. S. B., Winn, J. N., & Rusin, D. 2003, ApJ, 583, 58

Online Material

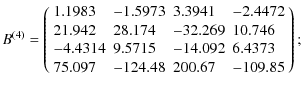

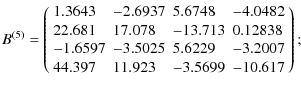

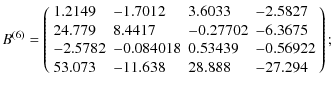

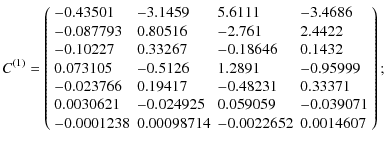

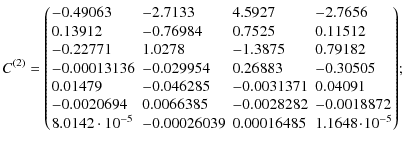

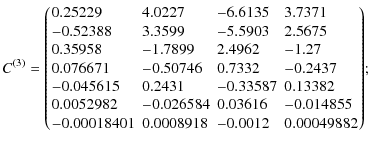

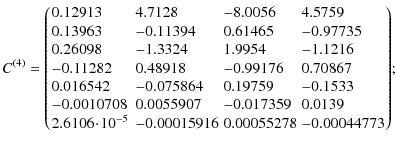

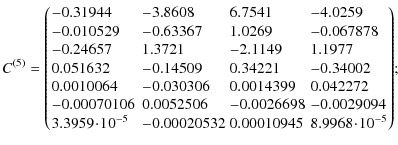

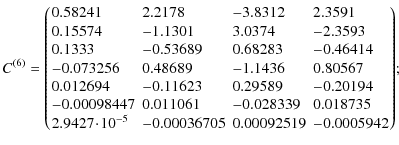

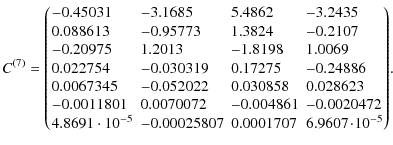

Appendix A: Fitting matrices

The matrices

![]() and

and

![]() (22),

(22),

![]() contain the coefficients of the reduced-power

spectrum fits given in Eq. (21). Here, we provide the numerical values from

our fits. The index

contain the coefficients of the reduced-power

spectrum fits given in Eq. (21). Here, we provide the numerical values from

our fits. The index ![]() corresponds to the function Q(12) in the fiducial cosmology, and

corresponds to the function Q(12) in the fiducial cosmology, and

![]() to its

derivatives with respect to cosmological parameters (see Table

1). The matrices are also available in electronic form

with an example code

to its

derivatives with respect to cosmological parameters (see Table

1). The matrices are also available in electronic form

with an example code![]() .

.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes

- ... lensing

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Appendix A is only available in electronic form at http://www.aanda.org

- ...

DES

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://www.darkenergysurvey.org

- ... LSST

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://www.lsst.org

- ... Euclid

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://www.ias.u-psud.fr/imEuclid

- ... survey

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://cosmos.astro.caltech.edu

- ... code

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- http://www2.iap.fr/users/kilbinge/reduced

All Tables

Table 1:

Parameter limits for where the accuracy of the fitted

reduced-shear power spectrum is better than ![]() for

for ![]() ,

and better than

,

and better than ![]() for

for

![]() (see also

Fig. 3).

(see also

Fig. 3).

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{14829Fg1}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14829-10/Timg69.png)

|

Figure 1:

The function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 2:

Fit coefficients as a function of scale factor.

Left: the polynomial fit coefficients c(0)i for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

|

Figure 3:

The fitted reduced-shear power spectrum (thick lines) and

the uncorrected convergence power spectrum (thin lines). Both

quantities are plotted as ratios with respect to the reduced-shear

power spectrum (6), where the first-order correction

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![\begin{displaymath}g = \frac{\gamma}{1-\kappa} = \gamma [ 1 + \kappa

+ \kappa^2

+ \ldots ].

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14829-10/img22.png)

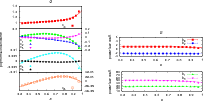

![\begin{displaymath}{P^{(1)}}^{mn}_{g}(\ell) = \int

\frac{{\rm d}^2\ell^{\prime}...

...) +

B^{nmm}_\kappa(\vec \ell_0, -\vec \ell^{\prime}) \right].

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14829-10/img37.png)

![$\displaystyle B_\kappa^{mnp}(\vec \ell_1, \vec \ell_2) = \int_{a_{\rm lim}}^1

{...

...{\vec \ell_1}{f_K[\chi(a)]},

\frac{\vec \ell_2}{f_K[\chi(a)]}; \chi(a)

\right);$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14829-10/img43.png)

![$\displaystyle Q(\ell, a) = 2 \int \frac{{\rm d}^2 \ell^\prime}{(2\pi)^2} \cos (...

...ac{\vec\ell_0}{f_K[\chi(a)]},

\frac{-\vec\ell^\prime}{f_K[\chi(a)]}\right)\cdot$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa14829-10/img51.png)