| Issue |

A&A

Volume 700, August 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A266 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Atomic, molecular, and nuclear data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554403 | |

| Published online | 26 August 2025 | |

Excitation of Molecules and Atoms for Astrophysics (EMAA): A spectroscopic and collisional database

1

Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG,

38000

Grenoble,

France

2

Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, OSUG,

38000

Grenoble,

France

★ Corresponding authors: alexandre.faure@univ-grenoblealpes.fr; aurore.bacmann@univ-grenoble-alpes.fr

Received:

6

March

2025

Accepted:

15

July

2025

Context. In astrophysical environments, the energy levels of molecules, atoms, and ions are rarely populated at local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE), that is the level populations reflect the competition between radiative and collisional processes. Interpreting non-LTE spectra therefore requires knowing both the Einstein radiative coefficients and the collisional rate coefficients. For a long time, inelastic collision calculations were limited to the most abundant and simple species, but they have now entered a new era thanks to the increase of computer power and the development of high-accuracy potential energy surfaces.

Aims. With the advent of observatories with powerful spectral capabilities, such as ALMA or the JWST, and the wealth of new species detected, obtaining collisional rate coefficients quickly has become essential. We aim to provide the community with atomic and molecular data available from the literature for an ever-increasing number of systems.

Methods. We have developed a database hosting both the collisional and spectroscopic data necessary to interpret spectra of non-LTE environments such as the (extra)galactic interstellar media, star-forming regions, and cometary atmospheres. We provide data files that can be employed directly in widely used non-LTE radiative transfer codes such as RADEX.

Results. To date, the database contains 106 targets, including nuclear-spin isomers and isotopologues and nine possible projectiles (ortho-H2, para-H2, H, H+, electrons, He, CO, ortho-H2 O and para-H2O, depending on the targets), for a total of 311 target-projectile data files.

Key words: atomic data / line: formation / molecular data / radiative transfer / astronomical databases: miscellaneous

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

In the ultra-high vacuum conditions that prevail in astrophysical molecular environments (densities lower than 1010 cm−3), the frequency of inelastic collisions is often insufficient to maintain the populations of atoms and molecules at local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE). As a result, interstellar and protostellar spectra in the microwave and infrared domains cannot generally be modeled by a single excitation temperature, and their intensity is strongly dependent on the density and temperature of the medium. The magnitude of non-LTE effects, however, depends on the molecule and on the transition under study. In the non-LTE regime, it is therefore necessary to resolve the statistical equilibrium of the ro-vibrational populations simultaneously with the radiative transfer equation. In addition to spectroscopic data, precise knowledge of the state-to-state collisional rate coefficients is therefore required. Since these coefficients are notoriously difficult to measure experimentally and because experiments can only cover a limited range of transitions and collision energies or temperatures, theory is the preferred approach to produce comprehensive sets of data. The collision partners are the most abundant species, namely these are H2 and He in the cold and radiatively shielded interstellar medium (ISM) and H, He, and free electrons in warmer and/or irradiated regions. In the atmospheres of comets, H2O and CO (and possibly CO2) become the dominant neutral colliders. The kinetic temperatures in these various environments vary from a few degrees Kelvin in prestellar cores to several thousand Kelvin in evolved (AGB) stellar envelopes.

The quantum theory of molecular collisions was developed in the 1960s and 1970s by Millard Alexander, Alex Dalgarno, David Flower, Sheldon Green, and their colleagues (see, e.g., Arthurs & Dalgarno 1960; Green & Thaddeus 1976; Flower & Launay 1977; Alexander & DePristo 1977). However, it was not until the years 2000 to 2010 that the combined progress of quantum chemistry and computing resources enabled theory to achieve an accuracy on the order of 10-30% and to rival (or even surpass) experiments in determining, for example, the collisional rate coefficients of CO (j = 1, 4, 6) + He between 15 and 294 K (Carty et al. 2004). At low kinetic temperatures (T < 100 K), the description of atomic and molecular collisions requires both very high-level ab initio electronic structure methods to determine potential energy surfaces (PES) and full quantum treatments for the dynamics of nuclei in order to properly describe purely quantum effects such as resonances, which are sharp enhancements in the cross section when the collision energy matches the energy of a metastable state of the collision complex, and interferences, which reflect the anisotropy of the PES. The gold standard methods in the field of cold atomic and molecular collisions are the coupled-cluster CCSD(T) theory1 for calculating the PES and the close-coupling theory for the scattering calculations (see the review by Roueff & Lique 2013, and references therein). The numerical effort is substantial, typically requiring several hundred thousand CPU hours for the complete study of a system. Approximations are thus necessary to tackle the most computationally demanding systems, particularly complex organic molecules for which the H2 projectile is, for example, substituted by a helium atom (e.g., Dzenis et al. 2022; Ben Khalifa & Loreau 2024). Quasi-classical, statistical and hybrid classical-quantum approaches have also been used in recent years to study collisions between H2O and another molecule (Faure & Josselin 2008; Loreau et al. 2018; Mandal et al. 2024). In the case of electronmolecule collisions, the R-matrix approach combined with the fixed-nuclei and (Coulomb-)Born approximations is currently the method of choice. It has been validated through comparison with elaborated calculations (multichannel quantum defect theory), for example, in the case of CH+ (Forer et al. 2024).

Over the same period (2000–2020), significant progress has also been made in the experimental field thanks to the development of new techniques based on, for example, supersonic expansion, crossed molecular beams, and the use of lasers to selectively populate and probe specific quantum states (Toscano 2024). Crossed molecular beam experiments, in particular, have made it possible to probe inelastic cross sections in the very low collision energy regime characterized by the presence of resonances that are extremely sensitive to the quality of the PES (e.g., Chefdeville et al. 2012; Vogels et al. 2018; Bergeat et al. 2020). Recently, the Cinétique de Réaction en Ecoulement Supersonique Uniforme (CRESU) experiment combined with an IR/UV double-resonance device has enabled the direct and absolute measurement of state-to-state rate coefficients for the CO + H2 system at temperatures below 20 K (Labiad et al. 2022). The first state-selected measurements of the rotational (de)excitation of CH+ by electron collisions were also performed at the cryogenic storage ring (CSR) (Kálosi et al. 2022). These various experiments have validated the calculations to a spectacular level of detail, demonstrating an accuracy on the order of 20% for the theoretical state-to-state rate coefficients. As a result, it was established that for a number of systems, collisional data (when available) are no longer the limiting factor in the reliability of non-LTE analyses.

Collisional (de)excitation data are currently available from several sources. For the interstellar and circumstellar media, BASECOL (Dubernet et al. 2024) supplies collisional rate coefficients with metadata for 94 species (atoms, molecules, or ions) and LAMDA (van der Tak et al. 2020) assorted spectroscopic and collisional data (without metadata) for 58 species in a format directly usable by radiative transfer codes such as RADEX (van der Tak et al. 2007), RATRAN (Hogerheijde & van der Tak 2000), and Cloudy (Chatzikos et al. 2023). The aim of the Excitation of Molecules and Atoms for Astrophysics (EMAA) database is i) to provide users with data files that include both collisional data and the corresponding spectroscopic data (energy levels, transition frequencies, and Einstein A coefficients) for direct use in radiative transfer codes and ii) to comply with the FAIR principles, that is, making the (meta)data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable for long-term scientific value. EMAA thus currently includes extensive metadata, unique and persistent digital object identifiers (DOI), and version control in order to support data citation and traceability. In addition, it is updated as regularly as possible (more than once a month on average) to support the ongoing efforts of the theoreticians.

The paper is organized as follows: In Sections 2 and 3, we describe the contents of the database and the web interface, respectively. In Section 4 we discuss the accuracy of data, and we conclude in Section 5.

2 Database description

2.1 Database contents

The aim of the new database for atomic and molecular collisions, EMAA, is to ensure a fast, efficient, and reliable dissemination of newly calculated collisional data. EMAA collects both spectroscopic data and collisional data for the main interstellar and cometary molecules. Spectroscopic data are taken from databases such as the Cologne Database for molecular spectroscopy (CDMS; Müller et al. 2005; Endres et al. 2016), the Jet Propulsion Laboratory molecular spectroscopy database (JPL; Pickett et al. 1998), the Lille Spectroscopic Database (LSD)2, the high-resolution transmission molecular absorption database (HITRAN; Gordon et al. 2022) and the ExoMol database (Tennyson et al. 2024). The collisional data, however, comes directly from the data producers and occasionally from the supplementary data of their articles or from the BASECOL database (Dubernet et al. 2024). In the following, the terminology “target” and “projectile” are employed in order to distinguish between the “target” atom or molecule whose internal quantum state is changed during the collision and the “projectile” atom or molecule whose internal quantum state is fixed (e.g., para-H2(j = 0)) or “thermalized.” In the latter case, the rate coefficients are summed over the final states of the projectile and averaged over a thermal distribution (at the kinetic temperature) of its initial states. This is required when the kinetic temperature is larger than the typical energy spacing of the projectile (see, e.g., Faure et al. 2020, for the rotational excitation of CO by H2O).

In EMAA, rotational, fine-structure, hyperfine, and ro-vibrational transitions are considered. The target species include atoms, molecules, and ions frequently encountered in the interstellar medium, star-forming regions, protoplanetary disks (especially their atmospheres and outer regions), envelopes of AGB stars, or comets. As for the projectiles, electrons, protons, atomic hydrogen, helium, molecular hydrogen (ortho and para), CO, and H2O (ortho and para) are included, depending on the target species. The data files provided by the EMAA database contain both spectroscopy (energy levels, transition frequencies, and Einstein A coefficients) and collisional data (collisional rate coefficients at different temperatures) with matching quantum numbers in the form of a file that can be directly used in the non-LTE radiative transfer code RADEX (van der Tak et al. 2007) or the spectral synthesis code Cloudy (Chatzikos et al. 2023), for example. The files are divided into three sections: the top section lists the energy levels of the target with their degeneracy and quantum numbers, the middle section gives the radiative transitions between the energy levels with transition frequencies and Einstein coefficients, and the last section gives the collisional rate coefficients for de-excitation between the energy levels for different kinetic temperatures.

We note that EMAA only provides spectroscopic data that have been validated by spectroscopists. Even though the energy levels and radiative transitions originating from spectroscopy databases may span a very wide range in energies, the maximum energy for the spectroscopy given in the EMAA data files is adjusted to the highest energy level of the collisional data, i.e. only the relevant subset of energy levels and radiative transitions are provided in EMAA. Conversely, when collisional data are available for higher energy levels than available in the spectroscopy line list (this can happen, for example, when the hyperfine splitting is resolved experimentally for low-lying energy levels only), the collisional rate coefficients in the EMAA data file are restricted to the highest energy level available in the line list. This ensures the self-consistency of the entire EMAA dataset. In the latter case, the full set of collisional data may always be retrieved by contacting the data producers.

To date, EMAA contains data for 106 target species (including rare isotopologues and nuclear-spin isomers) corresponding to 311 collisional systems with different projectiles. A list of the systems is presented in Table A.1.

2.2 Rare isotopologues

The EMAA database provides de-excitation rate coefficients for a number of rare isotopologues, including the isotopic elements D, 13C, 15N, 17O, 18O, 34S, 38Ar, and 40Ar. When a set of collisional data for a specific rare isotopologue (e.g., H13CO+) is not available, the de-excitation rate coefficients of the main isotopologue (HCO+) are used, and the actual data (“HCO+ data”) are specified with the reference. On the other hand, EMAA always provides the isotopologue-specific spectroscopic data.

As a general rule, H/D isotopic substitution has a strong impact for hydrides, such as in the case of water (Faure et al. 2024), with typical differences of a factor of two to three on the rate coefficients. For heavier molecules (e.g., HCN), the rate coefficients are changed typically by 10-30% for the dominant transitions (Denis-Alpizar et al. 2015) due to the smaller relative change in rotational constants. Heavy atom isotopic effects (e.g., 13C versus 12C) have been studied for the CO isotopologues (Dagdigian 2022d), and in this case differences were found not to exceed 20%. Isotopic substitution, however, can modify the symmetry of the main isotopologue (e.g., HDCO versus H2CO) as well as the hyperfine structure (e.g., 13CN versus CN). In such cases, isotopologue-specific calculations are mandatory.

2.3 CO and H2O projectiles

In certain environments, including cometary comas but also water rich (exo)planet atmospheres and in some protoplanetary disks, hydrogen (H or H2) may no longer be the main neutral projectile, and collisions with H2O and/or CO may dominate. Data with the projectiles para-H2O, ortho-H2O, and CO are currently available in EMAA for the target CO and its isotopologues 13CO and C18O (see Table A.1). We note that because the rigorous close-coupling approach is impractical for such systems (due to CPU and memory costs), alternative methods were employed, namely, the statistical adiabatic channel method for CO colliding with para-H2O and ortho-H2O (Faure et al. 2020) and the coupled-states approximation for CO + CO collisions (Żółtowski et al. 2023).

2.4 Data model

The EMAA application employs the Python Pyramid framework and accesses the PostgreSQL database via SQLAlchemy object-relational mapping. The software is developed under a Creative Commons license (BY-NC-SA), as are the data. The data import and export operations are performed via command line utilities. The source code is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

2.5 Metadata

Each dataset, consisting of collisional data and associated spectroscopy, has a unique and persistent DOI. This DOI depends on the type of transitions considered, i.e. for the same target molecule and same collisional partners, hyperfine transitions and rotational transitions will have a different DOI. The DOI resolves to a landing page with species names, identifiers (InChIKey), excitation type (typically rotation, hyperfine, fine-structure, rovi-bration), file details (number of energy levels, of transitions, of collisional transitions and temperatures), and bibliographical references of the data.

2.6 Data policy

When using data from EMAA, it is vital to acknowledge the work and dedication of the EMAA scientific partners who made this resource available. We thus strongly encourage users of EMAA to cite the original sources when using specific datasets (as well as the corresponding DOI whenever possible). This recognizes and values the data contributions from researchers. Accordingly, for each spectroscopic and collisional data file, EMAA provides the complete bibliographic references both in text and BibTeX format.

3 Web interface

Data from EMAA are accessible through the website emaa.osug.fr. The website has a search engine that finds all the targets in the database containing the chosen atoms. Otherwise, all the targets can be listed by number of atoms and increasing atomic mass. The target page allows the user to choose the type of transition (depending on the target, it can be rotational, fine-structure, hyperfine, or ro-vibrational) and then the specific projectile(s). After selection of both transition and projectile(s), an ASCII file in the RADEX format can be displayed or downloaded. If several projectiles are selected, all the corresponding collisional rate coefficients are included in the RADEX file.

New and recommended data appear on the front page of the species, while older data (less accurate but sometimes more complete) are available in an archive section on the species’ page. A comment box might specify that some datasets are not recommended for use; however, the data will still be available in EMAA to allow for comparison with previous applications. The comment box may also include important information about the datasets (e.g., their accuracy). An example of a front page for the species DCN is shown in Fig. 1.

4 Accuracy of data

4.1 Spectroscopic data

As explained in Section 2, spectroscopic data in EMAA are taken from databases such as the CDMS for microwave and (sub)millimeter frequency ranges. In such databases, experimental data reported in the literature have been fit to an effective Hamiltonian, and the derived spectroscopic parameters have been used to calculate the transition frequencies, the state energies, and the line intensities. In general, data are only provided if transition frequencies are known with enough accuracy for astronomical search, that is, if the rest frequencies are known to better than one megahertz (Endres et al. 2016). Line intensities are generally accurate to better than 1%, with uncertainties coming from errors in the dipole moment, for example. We note that in EMAA, Einstein A coefficients are provided rather than intensities, I (the equation relating I and A can be found in Pickett et al. (1998), their Eq. (9)). In the case of extensive empirical line lists, as provided by the ExoMol database, uncertainties are larger, but data extend over the infrared range and cover ro-vibrational transitions, which are not considered in CDMS or JPL, with a few exceptions.

|

Fig. 1 Screen capture of a typical page to access EMAA data. The example shown here is for DCN. In the first section, the user chooses the type of transition (among hyperfine structure, fine-structure, rotational, ro-vibrational) when several are available. In the second section, the collision partners are selected. The data can either be downloaded or displayed on screen by using one of the buttons at the bottom of the page. A comment box with notable information about the system might be present, depending on the species. An archive section is available, and it allows the user to access older spectroscopic or collisional data, when they exist. |

4.2 Collision data

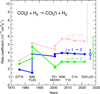

Collision data in EMAA are taken from theoretical data reported in the literature. Rate coefficients are generally computed using the close-coupling method for atom-molecule and moleculemolecule systems and the R-matrix approach for electronmolecule systems. As explained in the introduction, such gold standard calculations can provide a typical accuracy of 10%. As an illustration of this, we present in Fig. 2 the convergence of scattering calculations as a function of years for the most studied system: the rotational excitation of CO(ν = 0, j → j′) by para-H2. We can observe that the rate coefficients (at 10 K) for the three plotted transitions vary within a factor of two to three since 1976 before convergence to better than 5% is reached after 2010, which may be interpreted as the typical accuracy of theory for these three CO transitions (at 10 K). We note that since the close-coupling method was used in all the theoretical references, the convergence of theory mostly reflects the continuously improved accuracy of the CO-H2 PES. The theoretical rate coefficients can also be compared to the first state-to-state measurements performed below 20 K for CO(ν = 2, j=0, 1) molecules colliding with normal-H2 (Labiad et al. 2022). We note that the corrections due to the vibrational state of CO and the nuclear-spin form of H2 are minor at the current level of experimental accuracy3. As expected, very good agreement is observed between the experiment and the latest calculations (within 2σ for j = 0 → 1, within 1σ for j = 0 → 2 and within 0.5σ for j = 1 → 2), once again confirming (after the validation by the crossed beam measurements of Chefdeville et al. 2015) that the theoretical rate coefficients can be used with complete confidence in the interpretation of CO emission spectra.

The CO-H2 benchmark system exemplifies the theoretical accuracy achieved since the 2010s and thus the general quality of collisional data reported in EMAA, which derive for the most part from rigorous close-coupling calculations and high-accuracy PES. On the other hand, for the most demanding systems (large organic targets or heavy projectiles), where approximations are necessary, the accuracy hardly reaches 10% and typically lies between ∼50 and 100% (see, e.g., Faure et al. 2020, and references therein). A complementary discussion on the accuracy of collision data can be found in van der Tak et al. (2020).

|

Fig. 2 Rate coefficients for the rotational excitations j = 0 → 1, j = 0 → 2, and j = 1 → 2 of CO due to collisions with H2 at a kinetic temperature of 10 K. Filled circles show the theoretical rate coefficients for CO collisions with para-H2 as a function of years. Open circles indicate experimental rate coefficients for CO collisions with normal-H2 (Labiad et al. 2022, L22). Experimental error bars correspond to 2σ statistical errors (see text for details). Theoretical references are Green & Thaddeus (1976) (GT76), Schinke et al. (1985) (S85), Flower & Launay (1985) (FL85), Flower (2001) (F01), Mengel et al. (2001) (MDH01), Wernli et al. (2006) (W06), Yang et al. (2010) (Y10), Chefdeville et al. (2015) (C15), and Dagdigian (2022c) (D22). |

5 Conclusions

The new database EMAA compiles spectroscopic and collisional data for non-LTE modeling of astrophysical atomic and molecular spectra. The primary focus of EMAA is on interstellar and cometary molecules, whose main projectiles are He, H, H2, and CO and H2O electrons, respectively. Data cover the microwave, (sub)millimeter, and infrared frequency ranges. At present, 311 target-projectile systems are provided, corresponding to rotational, ro-vibrational, fine-structure, and hyperfine structure transitions, depending on the system, and the database is scheduled to be regularly updated following the availability of new collisional rate coefficients. Data can be easily downloaded from the EMAA website at emaa.osug.fr.

Future developments include, in addition to continuous data updates, the addition of new metadata to improve interoperability by following the community standards for atomic and molecular data and, in particular, the standards defined by the Virtual Atomic and Molecular Data Center (VAMDC), which are still evolving (Albert et al. 2020). A bibliographic database including all references attached to EMAA datasets will also be constructed to allow users to search for articles by target or projectile species and by transition types (rotational, fine-structure, hyperfine, ro-vibrational) with a BibTeX output format.

From a perspective point of view, it should be noted that most of the data in EMAA are currently for rotational, fine-structure, and hyperfine transitions. Comprehensive ro-vibrational datasets are available for only three light diatoms, H2, HD, and HeH+. Including the vibrational degrees of freedom in close-coupling calculations is very demanding, especially for polyatomic targets. Ro-vibrational state-to-state collisional data are indeed scarce in the literature (see van der Tak et al. (2020) for a list of systems) and generally incomplete (i.e., available over partial ranges of energy levels) despite recent progress toward polyatomics (see the very recent works on CO2 + He (Selim et al. 2023) and H2O + H2 (Wiesenfeld 2022; Garcia-Vazquez et al. 2024). Such data are critical to modeling infrared molecular emissions in warm and hot environments, as observed with JWST (see, e.g., Tabone et al. 2021, for the OH radical), and should become the focus of future studies. In this context, we note that ro-vibrationally state-selected reactive rate coefficients are also crucial in order to model the infrared emission of reactive species such as CH+ (Neufeld et al. 2021), and state-resolved reactive scattering calculations should be encouraged as well. Increasingly larger molecules will also need to be tackled, and in this regard, we note the recent detection of a seven-ring polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (with 37 atoms) toward the dark molecular cloud TMC-1 (Wenzel et al. 2025). Finally, with the continuous accumulation of collision data, the use of machine learning to predict state-to-state (inelastic or reactive) datasets with consistent accuracy will probably become evermore extensive (see, e.g., Bossion et al. 2024; Mihalik et al. 2025, for recent applications).

Data availability

The database is accessible at emaa.osug.fr.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Programme National « Physique et Chimie du Milieu Interstellaire » (PCMI) of the CNRS/INSU with INC/INP co-funded by CEA and CNES and by the Observatoire des Sciences de l’Univers de Grenoble. The authors thank the EMAA scientific council (A. Bergeat, F. Herpin, P. Hily-Blant, E. Josselin, F. Lique, J. Loreau) as well as the EMAA scientific partners (M. Ayouz, D. Babikov, C. Balança, P. Dagdigian, O. Denis-Alpizar, N. Feautrier, D. Flower, T. González-Lezana, V. Kokoouline, L. Margulès, R. Motyenko, H. Müller, O. Roncero, I. Schneider, Y. Scribano, I. Sims, T. Stoecklin, J. Tennyson, L. Wiesenfeld, A. Zanchet) and their collaborators. Special thanks to H. Müller for his precious help with CDMS archive data, and to P. Caselli, H. Nomura and J. Pety for their support. We are also grateful to A. Dubray for the development of the EMAA web site. Bernard Boutherin and Geneviève Michaud are finally acknowledged for the technical management of EMAA.

Appendix A Collisional systems in EMAA

Collisional systems present in EMAA database as of June 29, 2025.

References

- Albert, D., Antony, B. K., Ba, Y. A., et al. 2020, Atoms, 8, 76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. H., & DePristo, A. E. 1977, J. Chem. Phys., 66, 2166 [Google Scholar]

- Arthurs, A. M., & Dalgarno, A. 1960, Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. Ser. A, 256, 540 [Google Scholar]

- Balança, C., Dayou, F., Faure, A., Wiesenfeld, L., & Feautrier, N. 2018, MNRAS, 479, 2692 [Google Scholar]

- Balança, C., Scribano, Y., Loreau, J., Lique, F., & Feautrier, N. 2020, MNRAS, 495, 2524 [Google Scholar]

- Ben Khalifa, M., & Loreau, J. 2024, MNRAS, 527, 846 [Google Scholar]

- Ben Khalifa, M., Sahnoun, E., Wiesenfeld, L., et al. 2019, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 21, 1443 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Khalifa, M., Dagdigian, P. J., & Loreau, J. 2023, MNRAS, 523, 2577 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeat, A., Morales, S. B., Naulin, C., Wiesenfeld, L., & Faure, A. 2020, Phys. Rev. Lett., 125, 143402 [Google Scholar]

- Bop, C. T., & Lique, F. 2023, J. Chem. Phys., 158, 074304 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bop, C. T., Lique, F., Faure, A., Quintas-Sánchez, E., & Dawes, R. 2020, MNRAS, 501, 1911 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bop, C. T., Agúndez, M., Cernicharo, J., Lefloch, B., & Lique, F. 2024, A&A, 681, L19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bossion, D., Nyman, G., & Scribano, Y. 2024, Artif. Intell. Chem., 2, 100052 [Google Scholar]

- Bouhafs, N., Rist, C., Daniel, F., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 470, 2204 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhafs, N., Bacmann, A., Faure, A., & Lique, F. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 2178 [Google Scholar]

- Carty, D., Goddard, A., Sims, I. R., & Smith, I. W. M. 2004, J. Chem. Phys., 121, 4671 [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Spielfiedel, A., Balança, C., et al. 2011, A&A, 531, A103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzikos, M., Bianchi, S., Camilloni, F., et al. 2023, Rev. Mexicana Astron. Astrofis., 59, 327 [Google Scholar]

- Chefdeville, S., Stoecklin, T., Bergeat, A., et al. 2012, Phys. Rev. Lett., 109, 023201 [Google Scholar]

- Chefdeville, S., Stoecklin, T., Naulin, C., et al. 2015, ApJ, 799, L9 [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2018a, MNRAS, 477, 802 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2018b, MNRAS, 479, 3227 [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2018c, MNRAS, 475, 5480 [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2019, MNRAS, 487, 3427 [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2020, MNRAS, 494, 5239 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2022a, MNRAS, 518, 5976 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2022b, MNRAS, 511, 3440 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2022c, MNRAS, 514, 2214 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2022d, J. Chem. Phys., 157, 104305 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2023, MNRAS, 527, 2209 [Google Scholar]

- Dagdigian, P. J. 2025, J. Chem. Phys., 162, 174308 [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, F., Dubernet, M. L., & Grosjean, A. 2011, A&A, 536, A76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, F., Faure, A., Dagdigian, P. J., et al. 2014a, MNRAS, 446, 2312 [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, F., Faure, A., Wiesenfeld, L., et al. 2014b, MNRAS, 444, 2544 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, F., Faure, A., Pagani, L., et al. 2016a, A&A, 592, A45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, F., Rist, C., Faure, A., et al. 2016b, MNRAS, 457, 1535 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Demes, S., Lique, F., Faure, A., & van der Tak, F. F. S. 2023a, MNRAS, 527, 2573 [Google Scholar]

- Demes, S., Lique, F., Loreau, J., & Faure, A. 2023b, MNRAS, 524, 2368 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Denis-Alpizar, O., Stoecklin, T., & Halvick, P. 2015, MNRAS, 453, 1317 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Denis-Alpizar, O., Stoecklin, T., Guilloteau, S., & Dutrey, A. 2018, MNRAS, 478, 1811 [Google Scholar]

- Denis-Alpizar, O., Stoecklin, T., Dutrey, A., & Guilloteau, S. 2020, MNRAS, 497, 4276 [Google Scholar]

- Desrousseaux, B., & Lique, F. 2020, J. Chem. Phys., 152, 074303 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Desrousseaux, B., Coppola, C. M., & Lique, F. 2022, MNRAS, 513, 900 [Google Scholar]

- Dubernet, M. L., Boursier, C., Denis-Alpizar, O., et al. 2024, A&A, 683, A40 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dumouchel, F., Faure, A., & Lique, F. 2010, MNRAS, 406, 2488 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dzenis, K., Faure, A., McGuire, B. A., et al. 2022, ApJ, 926, 3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Endres, C. P., Schlemmer, S., Schilke, P., Stutzki, J., & Müller, H. S. P. 2016, J. Mol. Spectrosc., 327, 95 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., & Josselin, E. 2008, A&A, 492, 257 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Gorfinkiel, J. D., & Tennyson, J. 2004, MNRAS, 347, 323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Varambhia, H. N., Stoecklin, T., & Tennyson, J. 2007, MNRAS, 382, 840 [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Lique, F., & Wiesenfeld, L. 2016, MNRAS, 460, 2103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Halvick, P., Stoecklin, T., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 469, 612 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Lique, F., & Remijan, A. J. 2018, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 9, 3199 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Lique, F., & Loreau, J. 2020, MNRAS, 493, 776 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Żółtowski, M., Wiesenfeld, L., Lique, F., & Bergeat, A. 2024, MNRAS, 527, 3087 [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R. 2001, J. Phys. B At. Mol. Phys., 34, 2731 [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R., & Launay, J. M. 1977, J. Phys. B At. Mol. Phys., 10, 3673 [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R., & Launay, J. M. 1985, MNRAS, 214, 271 [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R., & Lique, F. 2014, MNRAS, 446, 1750 [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R., Le Bourlot, J., Pineau des Forets, G., & Roueff, E. 2000, MNRAS, 314, 753 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R., Pineau des Forêts, G., Hily-Blant, P., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 507, 3564 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Forer, J., Hvizdoš, D., Ayouz, M., Greene, C. H., & Kokoouline, V. 2024, MNRAS, 527, 5238 [Google Scholar]

- Fuente, A., García-Burillo, S., Usero, A., et al. 2008, A&A, 492, 675 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Vazquez, R. M., Faure, A., & Stoecklin, T. 2024, ChemPhysChem, 25, e202300698 [Google Scholar]

- Gerin, M., Liszt, H., Pety, J., & Faure, A. 2024, A&A, 686, A49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Giers, K., Spezzano, S., Caselli, P., et al. 2023, A&A, 676, A78 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y., Henkel, C., Bop, C. T., et al. 2025, A&A, 696, A31 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- González-Lezana, T., Hily-Blant, P., & Faure, A. 2021, J. Chem. Phys., 154, 054310 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- González-Lezana, T., Hily-Blant, P., & Faure, A. 2022, J. Chem. Phys., 157, 214302 [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, I. E., Rothman, L. S., Hargreaves, R. J., et al. 2022, J. Quant. Spec. Radiat. Transf., 277, 107949 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gratier, P., Pety, J., Guzmán, V., et al. 2013, A&A, 557, A101 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Green, S., & Thaddeus, P. 1976, ApJ, 205, 766 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, V. V., Goicoechea, J. R., Pety, J., et al. 2013, A&A, 560, A73 [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. R., Faure, A., & Tennyson, J. 2015, MNRAS, 455, 3281 [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. R., Faure, A., & Tennyson, J. 2018, MNRAS, 476, 2931 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, S., Faure, A., & Tennyson, J. 2013, MNRAS, 435, 3541 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Vera, M., Lique, F., Dumouchel, F., Hily-Blant, P., & Faure, A. 2017, MNRAS, 468, 1084 [Google Scholar]

- Hily-Blant, P., Faure, A., Vastel, C., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 480, 1174 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hogerheijde, M. R., & van der Tak, F. F. S. 2000, A&A, 362, 697 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kálosi, Á., Grieser, M., von Hahn, R., et al. 2022, Phys. Rev. Lett., 128, 183402 [Google Scholar]

- Kalugina, Y., Lique, F., & Kłos, J. 2012, MNRAS, 422, 812 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kłos, J., Ma, Q., Dagdigian, P. J., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 471, 4249 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kłos, J., Bergeat, A., Vanuzzo, G., et al. 2018, J. Phys. Chem. Lett., 9, 6496 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kłos, J., Dagdigian, P. J., Alexander, M. H., Faure, A., & Lique, F. 2020a, MNRAS, 493, 3491 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kłos, J., Dagdigian, P. J., & Lique, F. 2020b, MNRAS, 501, L38 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Labiad, H., Fournier, M., Mertens, L. A., et al. 2022, Phys. Rev. A, 105, L020802 [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S.-J., Pagani, L., Lai, S.-P., Lefèvre, C., & Lique, F. 2020, A&A, 635, A188 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lique, F. 2015, MNRAS, 453, 810 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lique, F., Senent, M.-L., Spielfiedel, A., & Feautrier, N. 2007, J. Chem. Phys., 126, 164312 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lique, F., Daniel, F., Pagani, L., & Feautrier, N. 2015, MNRAS, 446, 1245 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lique, F., Bulut, N., & Roncero, O. 2016, MNRAS, 461, 4477 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lique, F., Kłos, J., Alexander, M. H., Le Picard, S. D., & Dagdigian, P. J. 2017, MNRAS, 474, 2313 [Google Scholar]

- Lique, F., Zanchet, A., Bulut, N., Goicoechea, J. R., & Roncero, O. 2020, A&A, 638, A72 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Loreau, J., Faure, A., & Lique, F. 2018, J. Chem. Phys., 148, 244308 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Loreau, J., Faure, A., Lique, F., Demes, S., & Dagdigian, P. J. 2023, MNRAS, 526, 3213 [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, V. S., Hily-Blant, P., Faure, A., Hernandez-Vera, M., & Lique, F. 2018, A&A, 615, A52 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, B., Żółtowski, M., Cordiner, M., Lique, F., & Babikov, D. 2024, A&A, 688, A208 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Marinakis, S., Kalugina, Y., Kłos, J., & Lique, F. 2019, A&A, 629, A130 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mengel, M., De Lucia, F. C., & Herbst, E. 2001, Can. J. Phys., 79, 589 [Google Scholar]

- Mihalik, D. E., Wang, R., Yang, B. H., et al. 2025, J. Chem. Phys., 162, 024116 [Google Scholar]

- Müller, H. S. P., Schlöder, F., Stutzki, J., & Winnewisser, G. 2005, J. Mol. Struct., 742, 215 [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Almaida, D., Bop, C. T., Lique, F., et al. 2023, A&A, 670, A110 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld, D. A., Godard, B., Bryan Changala, P., et al. 2021, ApJ, 917, 15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, H. M., Poynter, R. L., Cohen, E. A., et al. 1998, J. Quant. Spec. Radiat. Transf., 60, 883 [Google Scholar]

- Pirlot Jankowiak, P., Lique, F., & Goicoechea, J. R. 2024, A&A, 683, A155 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pirlot Jankowiak, P., Lique, F., & Dagdigian, P. J. 2023a, MNRAS, 526, 885 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pirlot Jankowiak, P., Lique, F., & Dagdigian, P. J. 2023b, MNRAS, 523, 3732 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rabli, D., & Flower, D. R. 2010, MNRAS, 406, 95 [Google Scholar]

- Roueff, E., & Lique, F. 2013, Chem. Rev., 113, 8906 [Google Scholar]

- Schinke, R., Engel, V., Buck, U., Meyer, H., & Diercksen, G. H. F. 1985, ApJ, 299, 939 [Google Scholar]

- Selim, T., van der Avoird, A., & Groenenboom, G. C. 2023, J. Chem. Phys., 159, 164310 [Google Scholar]

- Sil, M., Faure, A., Wiesemeyer, H., et al. 2025, A&A, 695, A244 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tabone, B., van Hemert, M. C., van Dishoeck, E. F., & Black, J. H. 2021, A&A, 650, A192 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tennyson, J., Yurchenko, S. N., Zhang, J., et al. 2024, J. Quant. Spec. Radiat. Transf., 326, 109083 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toscano, J. 2024, Chimia, 78, 40 [Google Scholar]

- Troscompt, N., Faure, A., Maret, S., et al. 2009, A&A, 506, 1243 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van der Tak, F. F. S., Black, J. H., Schöier, F. L., Jansen, D. J., & van Dishoeck, E. F. 2007, A&A, 468, 627 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van der Tak, F. F. S., Lique, F., Faure, A., Black, J. H., & van Dishoeck, E. F. 2020, Atoms, 8, 15 [Google Scholar]

- Varambhia, H. N., Gupta, M., Faure, A., Baluja, K. L., & Tennyson, J. 2009, J. Phys. B: At. Mol. Opt. Phys., 42, 095204 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Varambhia, H. N., Faure, A., Graupner, K., Field, T. A., & Tennyson, J. 2010, MNRAS, 403, 1409 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels, S. N., Karman, T., Kłos, J., et al. 2018, Nat. Chem., 10, 435 [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, G., Gong, S., Xue, C., et al. 2025, ApJ, 984, L36 [Google Scholar]

- Wernli, M., Valiron, P., Faure, A., et al. 2006, A&A, 446, 367 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeld, L. 2022, J. Chem. Phys., 157, 174304 [Google Scholar]

- Wiesenfeld, L., & Faure, A. 2013, MNRAS, 432, 2573 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C., Remijan, A., Faure, A., et al. 2024, ApJ, 967, 164 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B., Stancil, P. C., Balakrishnan, N., & Forrey, R. C. 2010, ApJ, 718, 1062 [Google Scholar]

- Żółtowski, M., Lique, F., Loreau, J., Faure, A., & Cordiner, M. 2023, MNRAS, 520, 3887 [Google Scholar]

Specific scattering calculations can be found in Labiad et al. (2022).

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Screen capture of a typical page to access EMAA data. The example shown here is for DCN. In the first section, the user chooses the type of transition (among hyperfine structure, fine-structure, rotational, ro-vibrational) when several are available. In the second section, the collision partners are selected. The data can either be downloaded or displayed on screen by using one of the buttons at the bottom of the page. A comment box with notable information about the system might be present, depending on the species. An archive section is available, and it allows the user to access older spectroscopic or collisional data, when they exist. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Rate coefficients for the rotational excitations j = 0 → 1, j = 0 → 2, and j = 1 → 2 of CO due to collisions with H2 at a kinetic temperature of 10 K. Filled circles show the theoretical rate coefficients for CO collisions with para-H2 as a function of years. Open circles indicate experimental rate coefficients for CO collisions with normal-H2 (Labiad et al. 2022, L22). Experimental error bars correspond to 2σ statistical errors (see text for details). Theoretical references are Green & Thaddeus (1976) (GT76), Schinke et al. (1985) (S85), Flower & Launay (1985) (FL85), Flower (2001) (F01), Mengel et al. (2001) (MDH01), Wernli et al. (2006) (W06), Yang et al. (2010) (Y10), Chefdeville et al. (2015) (C15), and Dagdigian (2022c) (D22). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.