| Issue |

A&A

Volume 700, August 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A121 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Celestial mechanics and astrometry | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555470 | |

| Published online | 12 August 2025 | |

Obliquity of Mercury with a fluid core and a deformable mantle

1

LTE, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, Sorbonne Université, Université de Lille, LNE, CNRS,

61 Avenue de l’Observatoire,

75014

Paris,

France

2

Instituto de Matemática e Estatística, Universidade de São Paulo,

R. do Matão, 1010,

São Paulo,

SP 05508-090,

Brazil

★ Corresponding authors: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

9

May

2025

Accepted:

8

June

2025

In anticipation of BepiColombo’s orbital insertion in 2026, this study revisits the rotation of Mercury, modelling it with a fluid core and a deformable mantle. For this well-established physical model, we provide an analytical solution based on a novel Lagrangian formalism. Our approach enables a comprehensive 3D solution for the mantle’s orientation, including the phase in longitude at the perihelion. The model incorporates dissipative torques from core-mantle boundary friction and tidal deformations, conservative pressure torques, and the effect of the planet’s apsidal precession. We validate the equilibrium positions obtained numerically in previous studies, but identify discrepancies in earlier analytical works. These inconsistencies overestimated the out-of-Cassini-plane offset induced by tidal deformation by a factor of 100. Additionally, we explore the parameter space to determine where the spin axis deviates most from the Cassini plane and identify a region exhibiting bifurcation in the spin axis equilibrium position. This region cannot be adequately analysed using a model linearised with respect to the obliquity angle.

Key words: celestial mechanics / planets and satellites: dynamical evolution and stability / planets and satellites: interiors

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

The existence of a molten core in Mercury has been inferred since the detection of its magnetic field by the Mariner 10 spacecraft (Ness et al. 1974). Shortly thereafter, Peale (1976) discussed methods to independently estimate the polar moments of inertia, C for the entire planet and Cm for the mantle alone, using the planet’s obliquity and forced libration, knowing the gravitational coefficients C20 and C22. This estimation is feasible due to the core-mantle coupling, which is weak enough for the core to avoid following the mantle’s rapid 88-day libration period, yet strong enough for the core to follow the mantle’s slow 327000-year nodal precession (Peale 1976)1.

Subsequent measurements have been conducted using Earth-based radar observations for libration (Margot et al. 2007) and data from the MESSENGER spacecraft for obliquity and gravity coefficients (Mazarico et al. 2014). These observations nicely confirm the predictions of Peale (1976), with current estimates placing C/(MR2) at 0.333 ± 0.005 and Cm/C at 0.443 ± 0.019 (Genova et al. 2019; see also Goossens et al. 2022).

With this value of the mantle’s moment of inertia, the period of Mercury’s free oscillation in longitude is close to Jupiter’s 12-year orbital period (Margot et al. 2007). The amplitude and phase of the forced libration at this period should thus allow for the refinement of the mantle’s moment of inertia (Peale et al. 2009). However, observations over a sufficiently long timespan are still missing to properly fit these two quantities (Margot et al. 2007).

Other physical properties that can be probed by rotation include tidal dissipation and core-mantle interactions, such as viscous coupling, topographic coupling, electromagnetic coupling, and pressure coupling (Peale et al. 2014). The pressure torque, related to the flattening of the core, is a conservative torque that mainly modifies the equilibrium obliquity (Peale et al. 2014).

All other dissipative effects influence the amplitude and phase of the forced libration at 12 years (Peale et al. 2009), and they also displace the spin axis from the plane containing the normal to the invariant plane and the orbit pole, known as the Cassini plane (Peale et al. 2014).

The dissipative effects on Mercury’s spin axis orientation have been analysed numerically by Peale et al. (2014), and tides in particular, characterised by the ratio k2/Q of the Love number k2 divided by the quality factor Q, have been studied analytically for a solid Mercury without a molten core by Baland et al. (2017). Notably, all core-mantle dissipative mechanisms have quite similar signatures (Peale et al. 2014) and a significantly stronger effect than tides (Peale 2005). The addition of a solid inner core has been studied both numerically and analytically by (Peale et al. 2016; Dumberry 2021; MacPherson & Dumberry 2022).

Concurrently, observational studies of Earth-based measurements and MESSENGER data have constrained Mercury’s spin axis orientation, suggesting that Mercury’s spin indeed deviates from the Cassini plane by a few arcseconds (Margot et al. 2012; Mazarico et al. 2014; Stark et al. 2015a; Stark et al. 2015b; Verma & Margot 2016; Genova et al. 2019; Konopliv et al. 2020; Bertone et al. 2021). However, current observational uncertainties still leave room for further refinement, particularly in constraining the core-mantle interactions.

The upcoming BepiColombo mission, a joint endeavour between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), launched on October 19, 2018, represents a significant advancement in our ability to probe Mercury’s geophysical properties. Upon its scheduled orbital insertion in 2026, BepiColombo will deploy its suite of state-of-the-art instruments to achieve unprecedented accuracy in measuring geodetic parameters such as the gravitational coefficients C20 and C22, the amplitude of longitudinal librations, the orientation of the spin axis, and tidal deformation (Genova et al. 2021). These improved measurements will provide a more precise assessment of Mercury’s rotational motion, offering constraints on its interior structure (Steinbrügge et al. 2021).

In this study, we revisit Mercury’s rotational dynamics and derive analytical formulae for the orientation of its spin axis, extending the model presented in Baland et al. (2017) to include a fluid core. These formulae are designed to avoid the need for numerical integrations as in Peale et al. (2014). Given that the different core-mantle dissipative processes discussed by Peale et al. (2014) have similar signatures, here, we only consider the viscous coupling at the core-mantle boundary (CMB), which is proportional to the relative angular velocity between the core and the mantle (e.g. Peale et al. 2007).

While acknowledging the comprehensive model of MacPherson & Dumberry (2022) that includes the solid core, our initial focus is on refining the formula for the deviation of the spin axis from the Cassini plane induced by tides, addressing an inconsistency identified in Baland et al. (2017) and subsequently reproduced in MacPherson & Dumberry (2022). Additionally, we highlight a non-linear effect that emerges at low viscosity for specific values of the pressure torque, associated with the substantial tilt of the core’s angular velocity as depicted in Peale et al. (2014, Fig. 3) and discussed in Boué (2020). The exploration of more realistic interior structures is reserved for future work.

Our analysis employs the Lagrangian formalism developed in Ragazzo & Ruiz (2015) and Boué (2020), which is mathematically equivalent to the angular momentum approach followed by Baland et al. (2017). In Sections 2 and 3, we pursue a similar series of approximations as in Baland et al. (2017) to obtain analytical solutions. Section 2 is dedicated to the rigid body approximation while the tidal deformation is accounted in Section 3. The key distinction, beyond the incorporation of the fluid core in Section 4, lies in our consideration of the complete 3D rotation matrix defining Mercury’s orientation (three degrees of freedom), whereas Baland et al. (2017) focused solely on the spin axis (two degrees of freedom). As demonstrated in our results in Section 5, this methodological difference significantly impacts the outcomes, despite both approaches yielding consistent results when considering only the projection of the torque orthogonal to the spin axis. Our conclusions are presented in Section 6.

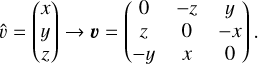

In this paper, we follow the notation of Boué (2020) and represent each vector v by a skew-symmetric matrix v such that

(1)

(1)

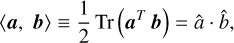

The dot product 〈, 〉 of two matrices is defined as

(2)

(2)

where Tr denotes the trace operator, and the norm  of a vector v is denoted ∥v∥.

of a vector v is denoted ∥v∥.

2 Mercury as a rigid body

Here, we retrieve the results of Baland et al. (2017) using the formalism of Boué (2020). The goal is to introduce the methodology on a simple case before adding complexity, namely deformation and a liquid core.

For the sake of generality, hereafter we refer to Mercury simply as a body ℬ of mass M and radius R orbiting a central point mass object m0. Let Rℬ be the rotation matrix between an inertial reference frame ℱinv and a frame ℱℬ attached to ℬ. For the inertial frame, we take a basis (iinv, jinv, kinv) whose third axis is normal to the invariant plane with respect to which the orbit is assumed to have a constant inclination i. As for the body fixed frame, we choose the basis composed of the principal axes of inertia (I, J, K), in which the moments of inertia are denoted A, B and C along the first, second and third axis, respectively.

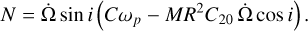

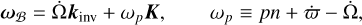

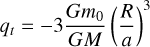

Let Ω be the longitude of the ascending node of the orbit reckoned from the invariant plane. We assume the planet to be in a p : 1 spin-orbit resonance, meaning that its angular velocity with respect to the inertial frame is

(3)

(3)

with  the orbital mean motion and ϖ the longitude of the periapsis. In practice, for Mercury, we have p = 3/2. In the expression of the mean motion, G is the gravitational constant and a the semi-major axis.

the orbital mean motion and ϖ the longitude of the periapsis. In practice, for Mercury, we have p = 3/2. In the expression of the mean motion, G is the gravitational constant and a the semi-major axis.

We consider that the position of the Cassini state corresponds to a fixed orientation of the vector K in a frame rotating at the orbital nodal precession frequency. Note that in the literature, Cassini states are sometimes defined using the angular momentum vector (Noyelles et al. 2011) instead of the body polar axis. However, both axes are very close, and for our purpose the two definitions are equivalent. Let us then introduce the frame ℱorb attached to the orbit whose basis (i, j, k) is such that i is along the orbital ascending node with respect to the invariant plane and k is along the orbital angular momentum. The transformation of coordinates between the orbital frame ℱorb and the inertial invariant frame ℱinv is given by Rinv = R3(Ω) R1 (i) where R1 denotes a rotation around the first axis and R3 around the third axis2. The rotation matrix between the body fixed frame ℱℬ and the inertial frame ℱinv can itself be decomposed as follows

(4)

(4)

with θp = pM + ϖ − Ω + γ0 the rotation angle of the planet, γ0 an offset being equal to 0 or π/2 depending on the resonance (Wisdom et al. 1984, page 139), M the mean anomaly, and R the rotation defining the orientation of the Cassini states. Were the body not in a Cassini state, the expression of Rℬ would still hold, but the angular velocity would have an extra term  accounting for the time derivative of R, namely

accounting for the time derivative of R, namely

(5)

(5)

In the following, we provide the equations of motion in terms of the variables (ω, R), the Cassini state being an equilibrium of the secular problem (averaged over the orbital mean anomaly) corresponding to ω = 0 and R = constant. When deformation is taken into account, the matrix of inertia (or equivalently the traceless symmetric B-matrix, as defined in Ragazzo & Ruiz (2015)) is allowed to vary, and an equation of motion is added for this variable.

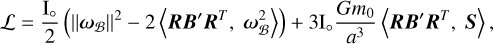

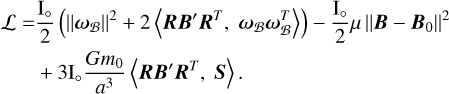

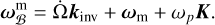

The Lagrangian describing the motion of (ω, R), written in the orbital frame ℱorb is (e.g. Boué 2020)

(6)

(6)

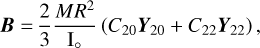

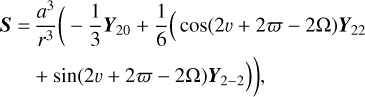

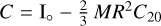

with I∘ ≡ (A + B + C)/3 the mean moment of inertia of the body ℬ, B′ = R3(θp)BR3(–θp), the B-matrix written in the preces-sional frame as defined in Ragazzo et al. (2022, Sect. 7) such that RB′RT is expressed in the orbital frame ℱorb, and S a traceless symmetric matrix encapsulating the orbital dependency of the spin-orbit potential energy. We only consider Mercury’s gravity field at second order, as the higher orders measured by MESSENGER (Smith et al. 2012; Mazarico et al. 2014) have negligible effects on the orientation of the spin axis (Noyelles & Lhotka 2013; Baland et al. 2017). We decompose B and S onto real spherical harmonic matrices as defined in Boué (2020), namely,

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

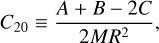

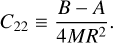

where r is the orbital separation and v the true anomaly. Parameters C20 and C22 are Stokes coefficients related to the moments of inertia according to

(9)

(9)

(10)

(10)

The equations of motion are (Boué 2020)

![$\matrix{ {{d \over {dt}}{{\partial L} \over {\partial \omega }} = \left[ {\omega ,{{\partial L} \over {\partial \omega }}} \right] + \hat J\left( L \right),} & {\dot R = \omega R} \cr } ,$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq14.png) (11)

(11)

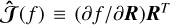

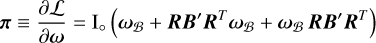

where  is the spin operator defined for all function f (R) as

is the spin operator defined for all function f (R) as  and [, ] is the usual commutator of two matrices : [A, B] ≡ AB – BA. The equilibrium is reached when the body’s angular momentum

and [, ] is the usual commutator of two matrices : [A, B] ≡ AB – BA. The equilibrium is reached when the body’s angular momentum

(12)

(12)

averaged over an orbital period remains constant for ω = 0. Substituting the expression of the Lagrangian in the equation of motion, one gets

![$\dot \pi = - \dot \Omega \left[ {{k_{inv}},\,\pi } \right] + 3{I_ \circ }\,{n^2}\left[ {RB'\,{R^T},\,S} \right].$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq18.png) (13)

(13)

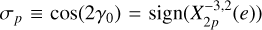

Setting the time average of the body’s angular momentum rate  equal to 0, we obtain an equation whose unknown is the rotation matrix R defining the orientation of the Cassini state in the orbital frame ℱorb. In the case of Mercury, the deviation of the figure-axis K from the orbit normal k is very small (about 2 arcmin). It is thus legitimate to linearise Eq. (13) over the tilt angle ε = ε1 i + ε2 j + ε3 k, where ε1 represents the in-plane offset of the Cassini state, ε2 the deviation from the Cassini plane, and ε3 the rotation lag of the body around its spin axis or, equivalently, the centre of libration in longitude. With this approximation, R ≈ 𝕀+ ε where 𝕀 is the identity matrix and RB′RT ≈ B′ + [ε, B′]. Moreover, the precession rate of the orbit

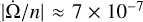

equal to 0, we obtain an equation whose unknown is the rotation matrix R defining the orientation of the Cassini state in the orbital frame ℱorb. In the case of Mercury, the deviation of the figure-axis K from the orbit normal k is very small (about 2 arcmin). It is thus legitimate to linearise Eq. (13) over the tilt angle ε = ε1 i + ε2 j + ε3 k, where ε1 represents the in-plane offset of the Cassini state, ε2 the deviation from the Cassini plane, and ε3 the rotation lag of the body around its spin axis or, equivalently, the centre of libration in longitude. With this approximation, R ≈ 𝕀+ ε where 𝕀 is the identity matrix and RB′RT ≈ B′ + [ε, B′]. Moreover, the precession rate of the orbit  is much smaller than the orbital mean motion n in absolute value (

is much smaller than the orbital mean motion n in absolute value ( ), therefore we can safely ignore terms in

), therefore we can safely ignore terms in  before those in n2. Applying the two simplifications in the expression of

before those in n2. Applying the two simplifications in the expression of  (Eq. (13)) and averaging over the mean anomaly, one gets

(Eq. (13)) and averaging over the mean anomaly, one gets

![$\eqalign{ & \left[ {\matrix{ D & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & D & 0 \cr 0 & N & { - 4{\kappa _{22}}} \cr } } \right]\left( {\matrix{ {{\varepsilon _1}} \cr {{\varepsilon _2}} \cr {{\varepsilon _3}} \cr } } \right) = - \left( {\matrix{ N \cr 0 \cr 0 \cr } } \right) \cr & + {\kappa _\omega }\left( {\matrix{ {\cos \left( {2\varpi - 2\Omega } \right)} & {\sin \left( {2\varpi - 2\Omega } \right)} & 0 \cr {\sin \left( {2\varpi - 2\Omega } \right)} & { - \cos \left( {2\varpi - 2\Omega } \right)} & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 \cr } } \right) \cr} $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq24.png) (14)

(14)

The polar moment of inertia is given by  . In the above expressions, we applied a notation similar to that introduced in Baland et al. (2017) up to a factor

. In the above expressions, we applied a notation similar to that introduced in Baland et al. (2017) up to a factor  . More explicitly, we have

. More explicitly, we have

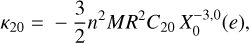

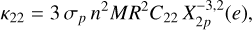

(17)

(17)

(18)

(18)

where the  are Hansen coefficients of the eccentricity e defined such that

are Hansen coefficients of the eccentricity e defined such that

(20)

(20)

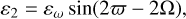

and  (Wisdom et al. 1984). The system of equations (14) was obtained with the help of the computer algebra system TRIP (Gastineau & Laskar 2011). This system includes trigonometric terms in 2ϖ – 2Ω due to the apsidal precession of the orbit as in Baland et al. (2017, Eqs. (34, 35)). These terms are responsible for a nutation of the spin axis at a slow period of about 84 kyr (Baland et al. 2017). To solve Eq. (14), we proceeded as in Baland et al. (2017), i.e. we first neglected the contribution due to the apsidal precession of the orbit, which amounts to set κω ~ e2p equal to zero. In that case, we get a first order solution

(Wisdom et al. 1984). The system of equations (14) was obtained with the help of the computer algebra system TRIP (Gastineau & Laskar 2011). This system includes trigonometric terms in 2ϖ – 2Ω due to the apsidal precession of the orbit as in Baland et al. (2017, Eqs. (34, 35)). These terms are responsible for a nutation of the spin axis at a slow period of about 84 kyr (Baland et al. 2017). To solve Eq. (14), we proceeded as in Baland et al. (2017), i.e. we first neglected the contribution due to the apsidal precession of the orbit, which amounts to set κω ~ e2p equal to zero. In that case, we get a first order solution  and

and  with

with

(21)

(21)

In a second step, we inserted this first order solution in the right-hand side of Eq. (14) and solved again the system. The result is

(22a)

(22a)

(22b)

(22b)

(22c)

(22c)

The results of this calculation from Eq. (21) to Eq. (23) are very similar to those in Baland et al. (2017). The main difference is the libration angle ε3 that is absent in Baland et al. (2017).

Let us rewrite the relevant formulae neglecting the nodal precession frequency  before the mean motion n in a simpler form :

before the mean motion n in a simpler form :

(24)

(24)

(25)

(25)

3 Mercury as a deformable body

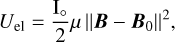

Here, we consider the case where the body is deformable. As in Ragazzo & Ruiz (2015), we introduce an effective macroscopic rigidity μ accounting for the elastic response of the body as a whole according to the elastic potential energy

(26)

(26)

where B0 is a permanent deformation induced by a prestress (Ragazzo et al. 2022). The effective rigidity μ is related to the Love number k2 and to the tidal parameter (Baland et al. 2017, Eq. (B.12))

(27)

(27)

For a smooth comparison with Baland et al. (2017), we also introduce the ratio of the centrifugal acceleration to the gravitational acceleration  . With the elastic potential energy, the Lagrangian of the problem now reads

. With the elastic potential energy, the Lagrangian of the problem now reads

(29)

(29)

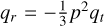

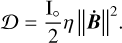

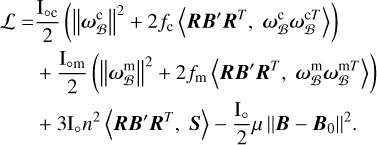

The viscous deformation of the body as a whole is controlled by a Rayleigh dissipation function 𝒟 that is a function of an effective macroscopic viscosity η such that

(30)

(30)

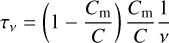

From the effective macroscopic viscosity η and the effective macroscopic rigidity μ, one can define a Maxwell relaxation time τM = η/μ that is related to the tidal quality factor Q = 1/(nτM). Introducing the phase shift ζ ≡ 1/Q = nτM as in Baland et al. (2017), we get the relation

(31)

(31)

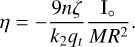

The equations of motion (11) for (ω, R) still hold. We now add the equation describing the evolution of the B-matrix, namely,

(32)

(32)

Since we discard the kinetic energy associated with the deformation of the body (there is no Ḃ dependency in the Lagrangian), the equation of motion (32) is equal to 0. This approximation is justified in Correia et al. (2018). Let δB ≡ B – B0 be the deviation of the B-matrix from its relaxed state B0. From the expression of the Lagrangian (29) and of Rayleigh dissipation function (30), the equation of motion (32) reads

(33)

(33)

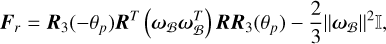

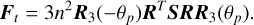

with F = Fr + Ft and

(34)

(34)

(35)

(35)

Given that the influence of deformation on the spin axis orientation is weak, only the leading-order terms are retained in the evaluation of the ‘force’ F on the left-hand side of Eq. (33). Consequently, we disregard the obliquity, assuming the spin axis to be perpendicular to the orbital plane, and neglect the precession frequency relative to the spin rate. With this approximation,

(36)

(36)

(37)

(37)

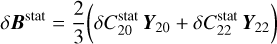

The static part  of F generates a constant deformation δBstat for which the Love number k2 admits the fluid limit kf. We get

of F generates a constant deformation δBstat for which the Love number k2 admits the fluid limit kf. We get

(38)

(38)

These two formulae are in perfect agreement with Baland et al. (2017, Eqs. (B.13–B.14)). Putting numbers into these expressions show that the hydrostatic parts  and

and  represent about 1% of the observed gravity field coefficients C20 and C22, respectively.

represent about 1% of the observed gravity field coefficients C20 and C22, respectively.

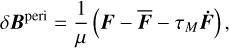

We now turn to the oscillatory part  that produces a significant out of plane offset of the Cassini state of about 1 arcsec according to Baland et al. (2017). At first order in τΜ = η/μ, the oscillatory (or periodic) part δBperi of δB is

that produces a significant out of plane offset of the Cassini state of about 1 arcsec according to Baland et al. (2017). At first order in τΜ = η/μ, the oscillatory (or periodic) part δBperi of δB is

(41)

(41)

with μ evaluated at k2 ≠ kf. In our approximation, the centrifugal force remains static in the body frame. Consequently, we can compute the periodic component of δB using Eq. (41), substituting the force F with Ft.

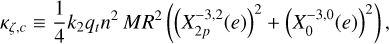

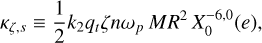

Once δBperi is known, the system (14) is recomputed with B′ replaced by B′ + R3(θp)δBperiR3(–θp) in Eqs. (12 and 13). The result is averaged over the mean anomaly and over the longitude of the periapsis to focus on the out of plane offset of the Cassini state. The calculation done with TRIP gives

![$\left[ {\matrix{ D & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & D & 0 \cr 0 & N & { - 4{\kappa _{22}}} \cr } } \right]\left( {\matrix{ {\delta {\varepsilon _1}} \cr {\delta {\varepsilon _2}} \cr {\delta {\varepsilon _3}} \cr } } \right) = - \left( {\matrix{ {{\kappa _{\zeta ,c}}\,{\varepsilon _\Omega }} \cr {{\kappa _{\zeta ,s}}\,{\varepsilon _\Omega }} \cr {{\kappa _{\zeta ,s}}\,{\kappa _{\zeta ,n}}} \cr } } \right),$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq66.png) (42)

(42)

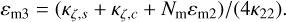

where δε = (δε1, δε2, δε3) is a correction to the solution ε = (ε1, ε2, ε3) obtained in the rigid case (Eq. (22)). The constants in this new system are defined as

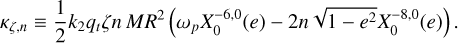

(43)

(43)

(44)

(44)

(45)

(45)

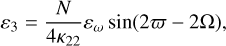

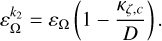

The first line of Eq. (42) provides a small correction to the in-plane offset of the Cassini state εΩ of the order of 0.1% that becomes

(46)

(46)

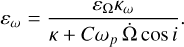

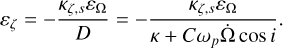

The third line corresponds to a rotation of the body around its figure axis of about 3 arcsec, and the second line gives the out of plane offset of the Cassini state, namely, δε2 = εζ with

(47)

(47)

This result shows some similarities with Baland et al. (2017, Eq. (66)). Our denominator is directly expressed in terms of the entries of the B-matrix while in Baland et al. (2017) the same denominator (up to a coefficient cos i) explicitly shows the contribution of the static hydrostatic adjustment (related to the δBstat-matrix) with respect to a situation where only the relaxed gravity field coefficients (related to the B0-matrix) would have been taken into account. But since observations cannot distinguish these two constant components, we chose not to split the entries of the B-matrix (which means that in our notation, C, C20 and C22 do include the permanent hydrostatic deformation).

The primary difference between our result (47) and Baland et al. (2017, Eq. (66)) lies in the numerator. Our expression includes only the first term of Baland et al.’s numerator, omitting the cos i factor. To derive their Eq. (66), Baland et al. (2017) solved two components of their 3D angular momentum equation (Eq. (59)), where the unknown is the spin axis (ŝ(t) in their notation). The challenge arises because their Eq. (59) for dŝ/dt is not orthogonal to ŝ, despite ŝ being a unit vector. By definition, if ŝ ∙ ŝ = 1, then  should be zero.

should be zero.

To address this issue, Baland et al. (2017) would have considered the two components of the torque orthogonal to ŝ (or to the orbit pole k, given the very small obliquity of the Cassini state εΩ). They instead chose the two components in the invariant plane, resulting in their numerator containing the second component of the right-hand side of our Eq. (42) multiplied by cos i, plus the third component of the right-hand side of our Eq. (42) multiplied by sin i. As a result, the reasoning used in Baland et al. (2017) to obtain their final expression Eq. (66) is not correct. We nevertheless verified that our expression for εζ can be derived from Baland et al.’s equation of motion (Eq. (59)) using the correct projections.

4 Influence of a fluid core

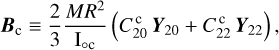

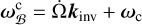

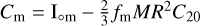

In this section, we take into account the presence of a molten core in the interior of Mercury. The mantle surrounding the core is still subject to tidal deformation. The fluid core is parameterised by its mean moment of inertia I∘c and by the B-matrix

(48)

(48)

where the Stokes coefficients  and

and  are normalised by the product MR2 of the total mass M and the full radius squared R2 of the body. The matrix Bc implicitly defines the shape of the core mantle boundary (CMB). The mantle is equiva-lently characterised by its mean moment of inertia I∘m and the B-matrix

are normalised by the product MR2 of the total mass M and the full radius squared R2 of the body. The matrix Bc implicitly defines the shape of the core mantle boundary (CMB). The mantle is equiva-lently characterised by its mean moment of inertia I∘m and the B-matrix

(49)

(49)

where  and

and  also are normalised by MR2. The overall body has a mean moment of inertia I∘ = I∘c + I∘m and its gravity field is represented by the matrix B such that I∘B = I∘cBc + I∘mBm. These three matrices rotate in concert with the rotation matrix of the mantle R. Under tidal perturbation, Bc and Bm could vary independently. We should expect two normal modes of vibration, a symmetric one where the two matrices oscillate in phase and another antisymmetric where they oscillate in antiphase. For the sake of simplicity, we only consider the symmetric mode and assume that each of these B-matrices remain proportional to the total B-matrix with a constant coefficient that we denote fc for the core and fm for the mantle, namely,

also are normalised by MR2. The overall body has a mean moment of inertia I∘ = I∘c + I∘m and its gravity field is represented by the matrix B such that I∘B = I∘cBc + I∘mBm. These three matrices rotate in concert with the rotation matrix of the mantle R. Under tidal perturbation, Bc and Bm could vary independently. We should expect two normal modes of vibration, a symmetric one where the two matrices oscillate in phase and another antisymmetric where they oscillate in antiphase. For the sake of simplicity, we only consider the symmetric mode and assume that each of these B-matrices remain proportional to the total B-matrix with a constant coefficient that we denote fc for the core and fm for the mantle, namely,

(50)

(50)

By definition of the matrix B, the two coefficients fc and fm are related to each other by the formula

(51)

(51)

The rotational state of the core is given by its angular velocity

(52)

(52)

where ωc is the rotation speed with respect to the orbital frame. For the mantle, we chose the same decomposition as in the single layer model above, i.e. we define its angular velocity as

(53)

(53)

The variables of the problem are (ωc, ωm, R, B). At a Cassini state, the system is in a relative equilibrium characterised by ωm = 0, ωc = constant and R = constant.

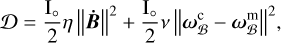

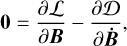

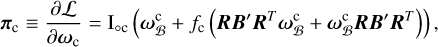

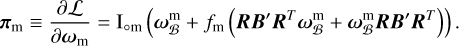

The Lagrangian of the system is the kinetic energy of the core plus the kinetic energy of the mantle minus the spinorbit potential energy minus the elastic potential energy of deformation

(54)

(54)

To this Lagrangian, we added a Rayleigh dissipation function similar to the one used above in the single layer approach but with an extra term accounting for a viscous friction at the CMB, namely,

(55)

(55)

where ν (not to be confused with the true anomaly v) has the dimension of a frequency related to the inverse of the characteristic timescale

required to damp the relative angular velocity of the core with respect to that of the mantle (Peale et al. 2009). In this formula,  is the mantle’s polar moment of inertia. The equations of motion are

is the mantle’s polar moment of inertia. The equations of motion are

![${\dot \pi _c} = \left[ {{\omega _c},\,{\pi _c}} \right] - {{\partial D} \over {\partial {\omega _c}}},$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq87.png) (56a)

(56a)

![${\dot \pi _m} = \left[ {{\omega _m},\,{\pi _m}} \right] - {{\partial D} \over {\partial {\omega _m}}} - J\left( L \right),$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq88.png) (56b)

(56b)

(56c)

(56c)

where the angular momenta are given by

(57)

(57)

(58)

(58)

To get the position of the Cassini state, we proceed as above. The periodic oscillations δBperi of the B-matrix are computed at the leading order and injected in the first two equations of motion whose explicit expressions read

![${{\dot \pi }_c} = - g\left[ {{k_{inv}},\,{\pi _m}} \right] - {I_{ \circ ,c}}{f_c}\left[ {RB'\,{R^T},\,{{\left( {\omega _B^c} \right)}^2}} \right] - {I_ \circ }\nu \left( {\omega _B^c - \omega _B^m} \right).$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq92.png) (59)

(59)

![$\eqalign{ & {{\dot \pi }_m} = - g\left[ {{k_{inv}},\,{\pi _m}} \right] - {I_{ \circ ,c}}{f_c}\left[ {RB'\,{R^T},\,{{\left( {\omega _B^c} \right)}^2}} \right] + {I_ \circ }\nu \left( {\omega _B^c - \omega _B^m} \right) \cr & - 3.{I_ \circ }{n^2}\left[ {RB'\,{R^T},\,S} \right], \cr} $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq93.png) (60)

(60)

with now B′ ≡ R3(θp)(B + δBperi)R3(–θp). The second term in the right-hand side of  and

and  represents the conservative coupling between the core and the mantle generated by the pressure force of the liquid as it rotates while the third term accounts for the friction at the CMB. When adding the two equations of motion, we easily check that the total angular momentum π = πc + πm does satisfy the same equation of motion as in the single layer case (13), as it should be.

represents the conservative coupling between the core and the mantle generated by the pressure force of the liquid as it rotates while the third term accounts for the friction at the CMB. When adding the two equations of motion, we easily check that the total angular momentum π = πc + πm does satisfy the same equation of motion as in the single layer case (13), as it should be.

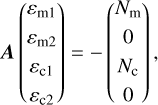

To solve Eqs. (59) and (60), we searched for a solution of the form R = εm1 i + εm2j + εm3k and ωc = ωp (εc2i – εc1j + k). The calculation done with TRIP shows that the in-plane obliquities εm1 and εc1 and the deviations from the Cassini plane εm2 and εc2 again are decoupled from the mantle’s rotation lag εm3 that is given by

(61)

(61)

The other angles are solution the linearised system

(62)

(62)

where A = Av + Αω + Αζ is a 4 × 4 matrix given by

![${A_\nu }\left[ {\matrix{ {{D_m}} & F & E & { - F} \cr { - F} & {{D_m}} & F & E \cr E & { - F} & {{D_c}} & F \cr F & E & { - F} & {{D_c}} \cr } } \right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq98.png) (63)

(63)

![${A_\omega } = - {\kappa _\omega }\left[ {\matrix{ {\cos \left( {2\varpi - 2\Omega } \right)} & {\sin \left( {2\varpi - 2\Omega } \right)} & 0 & 0 \cr {\sin \left( {2\varpi - 2\Omega } \right)} & { - \cos \left( {2\varpi - 2\Omega } \right)} & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \cr 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 \cr } } \right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq99.png) (64)

(64)

![${A_\zeta } = \left[ {\matrix{ { - {K_1} + {\kappa _{\zeta ,c}}} & {{K_2} - {\kappa _{\zeta ,s}}} & {{K_3}} & { - {K_4}} \cr { - {K_2} + {\kappa _{\zeta ,s}}} & { - {K_1} + {\kappa _{\zeta ,c}}} & {{K_4}} & {{K_3}} \cr {{K_3}} & { - {K_4}} & { - {K_5}} & {{K_6}} \cr {{K_4}} & {{K_3}} & { - {K_6}} & { - {K_5}} \cr } } \right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/08/aa55470-25/aa55470-25-eq100.png) (65)

(65)

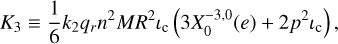

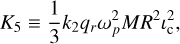

with the parameters

(66)

(66)

(67)

(67)

(68)

(68)

(69)

(69)

(70)

(70)

(71)

(71)

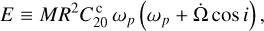

where Cc and Cm are the polar moment of inertia of the core and of the mantle, respectively, and

(72)

(72)

(73)

(73)

(74)

(74)

(75)

(75)

(76)

(76)

(77)

(77)

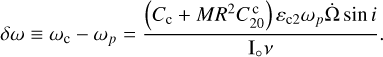

where lc = I∘c fc/I∘. The coefficients κ, κ22, and κω have exactly the same expression as in the single layer model (see Eqs. (17)–(19)). In this system of equations, we retained only the leading terms, disregarding those involving  and smaller. A keen observer might notice that the system governed by Equations (59) and (60) contains six independent equations, whereas Equations (61) and (62) together provide only five. Indeed, there is an additional equation that the system must satisfy, corresponding to the projection of

and smaller. A keen observer might notice that the system governed by Equations (59) and (60) contains six independent equations, whereas Equations (61) and (62) together provide only five. Indeed, there is an additional equation that the system must satisfy, corresponding to the projection of  onto the unit vector k. This equation has no solution under the assumption that the core’s spin rate ωc equals the mantle’s spin rate, ωp. However, if we allow the core spin rate to differ slightly from the mantle spin rate by a small amount δω, the final equation yields

onto the unit vector k. This equation has no solution under the assumption that the core’s spin rate ωc equals the mantle’s spin rate, ωp. However, if we allow the core spin rate to differ slightly from the mantle spin rate by a small amount δω, the final equation yields

(78)

(78)

In Equation (62), we decomposed the matrix A into three matrices, Av, Αω, and Αζ to emphasise the distinct physical processes involved. The matrix Av encapsulates the core-mantle interaction, namely the pressure torque (parameter E) and the viscous coupling (parameter F). The matrix Αω describes the apsidal precession of the orbit, as observed in Peale et al. (2014) and detailed in Baland et al. (2017). The matrix Αζ accounts for the tidal deformation.

By neglecting apsidal precession and tidal deformation, and considering the frictionless regime (F = 0) at the CMB, the system (62) decouples into two independent subsystems involving (εm1, εc1) and (εm2, εc2), respectively. The 2 × 2 matrix with entries Dm, E, E, and Dc is generically invertible, implying that εm2 and εc2 must be zero. This signifies that, in this case, the Cassini state resides within the Cassini plane (Boué 2020). However, the inclusion of friction, apsidal precession, or tidal deformation couples (εm1, εc1) and (sm2, εc2), leading to a deviation of the Cassini state from the Cassini plane.

In the following, solutions are obtained by inverting the system described in Equation (62). This analytical approximation holds valid as long as the quantities εm1, εm2, εm3, εc1, εc2, and δω/ωp are much smaller than one.

5 Results

Here, we apply the model to Mercury where p = 3/2, γ0 = 0 and σp = +1. We briefly consider the solid case without molten core to compare our results with those of Baland et al. (2017) and MacPherson & Dumberry (2022). Then, we rapidly switch to the two-layer model for comparison with Peale et al. (2014) and to explore a larger domain of the parameter space.

5.1 Mercury as a solid body with no fluid core

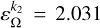

Using the parameters from Baland et al. (2017), we find the obliquity of Mercury in the Cassini plane to be εΩ = 2.026 arcmin (Eq. (21)) for the rigid case and  arcmin (Eq. (46)) for the deformable case, in perfect agreement with Baland et al. (2017).

arcmin (Eq. (46)) for the deformable case, in perfect agreement with Baland et al. (2017).

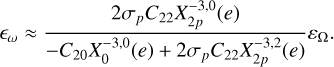

The radius of the circle described by the top of the spin axis, as the argument of the perihelion spans 180 degrees (see, e.g. Baland et al. 2017, Fig. 8), is given by our formula (23) as εω = 0.898 arcsec (hereafter, we refer to this motion as the apsidal circle). The value we obtain for εω is slightly larger than the 0.868 and 0.863 arcsec found by Baland et al. (2017) for the deformable and rigid cases, respectively.

However, we obtain a value closer to that of Baland et al. (2017), namely εω = 0.865 arcsec, when substituting C20 and C22 with  and

and  , respectively. As explained earlier, we consider the C20 and C22 values measured with MESSENGER (Mazarico et al. 2014) to include the static component of their tidal deformation. Therefore, we favour the formula without the static corrections

, respectively. As explained earlier, we consider the C20 and C22 values measured with MESSENGER (Mazarico et al. 2014) to include the static component of their tidal deformation. Therefore, we favour the formula without the static corrections  and

and  .

.

Lastly, for the deviation of the apsidal circle from the Cassini plane, we obtain εζ = 0.0097 arcsec, a value much smaller than its radius, in agreement with the green circle represented in Peale et al. (2014, Fig. 3), whereas Baland et al. (2017) found 0.995 arcsec, a value approximately 100 times larger. As discussed previously, we believe the extreme value reported by Baland et al. (2017) is due to incorrect projections of their equations of motion (59), which are not self-consistent because of the lack of the rotation lag (ε3 in our notation). This omission resulted in the unit vector ŝ and its time derivative not being orthogonal.

Surprisingly, MacPherson & Dumberry (2022) reproduce the deviation angle εζ from the Cassini plane, as found by Baland et al. (2017), using their Equation (16), despite working in the mantle’s equatorial plane, which by definition, is orthogonal to the figure axis. Therefore, the argument we presented against Baland et al. (2017) does not apply in this case. The origin of the discrepancy between our result and that of MacPherson & Dumberry (2022) remains unclear.

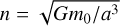

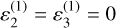

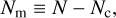

|

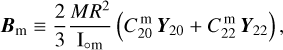

Fig. 1 Projected equilibrium spin axes on the orbital plane for varying core-mantle viscous friction, assuming a spherical core. a) Mantle spin axis coordinates. b) Core spin axis coordinates. The vertical line labelled Cassini plane in panel a) is the intersection of the Cassini plane with the orbital plane. Red dots indicate coordinates from Peale et al. (2014, Table 2). The observations are taken from Margot et al. (2012); Mazarico et al. (2014); Stark et al. (2015a); Verma & Margot (2016); Genova et al. (2019); Konopliv et al. (2020); Bertone et al. (2021). |

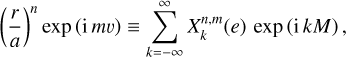

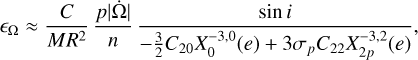

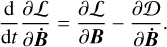

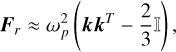

5.2 Influence of the molten core

In Peale et al. (2014), the authors determined the equilibrium of Mercury’s spin axis through numerical integration of equations of motion similar to our system (56), but also incorporating magnetic and topographic core-mantle couplings. One of our goals is to reproduce their results analytically, eliminating the need for numerical simulations. For easier comparison, we adopt their planetary parameters but retain the orbital parameters from Baland et al. (2017).

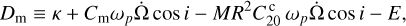

To validate our model, we reproduced Figure 3 from Peale et al. (2014) in our Figure 1, with red dots indicating the values from their Table 2. This figure shows the projection of the equilibrium spin axis onto the orbital plane for varying core-mantle viscous friction. Our model’s agreement with their numerical solution is excellent. We also plot recent measurements of Mercury’s spin pole orientation with their associated 1σ error bars. The model can explain the observed deviation from the Cassini plane, εm2, provided the tilt is towards positive abscissa (Xm > 0). Among the seven measurements in Figure 1, only that of Mazarico et al. (2014) has a negative abscissa, with its error bar crossing the Cassini plane at the bottom of the figure. As noted in the introduction, the whole planet’s moment of inertia, C, can be adjusted to fit the in-plane obliquity εm1 without affecting the longitude libration fit, provided the mantle’s moment of inertia, Cm, remains fixed (Peale 1976). Thus, fitting the spin axis orientation primarily involves determining the core’s moment of inertia, Cc, and the viscosity, parameterised by the relaxation time τν.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that our model’s leading-order computation of the planet’s elastic deformation does not account for the fluid core spin obliquity. Including this effect could cause the viscous coupling to tilt the mantle spin axis towards Xm < 0, as explained in MacPherson & Dumberry (2022).

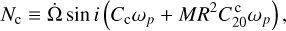

Figure 3 of Peale et al. (2014) and our Figure 1 were obtained for a spherical core. However, Peale et al. (2014) noted that the hydrostatic shape of the core would lead to a geometric flattening of εf = 7.161 × 10–5, corresponding to fc = 1.04 in our notation. They also considered a non-hydrostatic case with twice the flattening, implying fc = 2.08. With these values, Peale et al. (2014) concluded that the spin axes of the core and mantle should be nearly aligned and close to the Cassini plane.

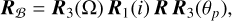

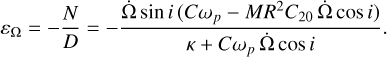

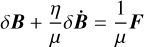

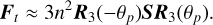

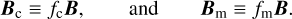

To better understand this conclusion, we constructed a map of the mantle’s in-plane obliquity, εm1, and deviation from the Cassini plane, εm2, as functions of the core flattening coefficient, fc, and viscous timescale τν. The five cases considered by Peale et al. (2014) in their Figure 3 are indicated by black crosses in our Fig. 2. The hydrostatic flattening of the core places Mercury slightly outside the map to the right. In Figure 2a, we observe two plateaus: the light red area corresponds to εm1 ≈ 2 arcmin as observed, while the blue upper left corner shows a plateau at 1 arcmin. The ratio between these two values is exactly C/Cm, implying that only the mantle is tilted in the blue region of the parameter space (Fig. 2a). Indeed, in the upper left corner, both flattening and viscous friction are low, decoupling the core from the mantle even on the nodal precession timescale. The transition occurring at fc ≈ 0.005 corresponds to a resonance of the precession angular speed with the nearly diurnal free wobble eigenfrequency (Ragazzo et al. 2022). The parameters chosen by Peale et al. (2014) ensure that the pressure torque is negligible (fc ≪ 1), and the range of viscous timescales spans the transition between coupled and uncoupled core-mantle states. Figure 2b shows that this parameter space region exhibits significant deviation from the Cassini plane. As observed by Peale et al. (2014), adding the pressure torque (fc close to one) causes the planet to behave like a solid body, reducing the deviation from the Cassini plane that is then solely induced by tidal deformation.

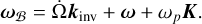

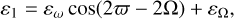

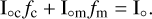

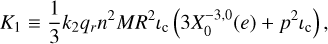

In Figures 2a and 2b, the white domain corresponds to extreme solution values where the linear approximation used in this study fails. The parameter space studied by Boué (2020) corresponds to the upper line of the figure (τν → ∞ and a full range of fc). Although the linear model always provides a single solution, the non-linear solution obtained in the inviscid case exhibits a bifurcation (Fig. 3). It may seem surprising that Mercury’s obliquity shows non-linear effects despite its small value. This is due to the core reaching high obliquities of the order of 90 degrees, as shown in Peale et al. (2014) and Boué (2020). In this parameter space region, it is necessary at least to treat the core’s in-plane obliquity, εc1, non-linearly. But as the core tilts, its angular speed significantly differs from the mantle’s, requiring the addition of a new variable ωc to model this spin rate. And the relative angular speed, δω = ωc – ωp, between the core and the mantle, must also be treated non-linearly.

|

Fig. 2 Mantle’s in-plane obliquity εm1 (a) and deviation from the Cassini plane εm2 (b) as functions of the core flattening coefficient fc and viscous relaxation time τν. The white domains correspond to values that fall outside the colour scales. In these regions, the linear approximation is no longer valid and the equations of motions have to be solved treating the core’s in-plane obliquity and angular velocity non-linearly. Black crosses indicate the parameters considered by Peale et al. (2014), shown as red dots in our Figure 1. |

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we present a new formulation of the classical model describing the rotation of Mercury, grounded in an advanced Lagrangian formalism developed by Ragazzo & Ruiz (2015) and Boué (2020). This approach enables a comprehensive 3D solution for the mantle’s orientation, including the phase in longitude at the perihelion, and in the future, will contribute to constraining its internal structure.

The final model takes into account a deformable mantle and a fluid ellipsoidal core, whose flattening imposes the conservative pressure torque. We also consider apsidal precession and dissipative effects associated with tidal interactions and friction between the core and mantle.

Firstly, we compare our results with those of Baland et al. (2017) by treating Mercury initially as a rigid body and subsequently as a deformable body. We obtain similar values for the offset in the Cassini plane, with 2.026 arcmin in the rigid case and 2.031 arcmin in the deformable case. However, we find a radius of 0.898 arcsec for the circle traced by the rotation axis during one perihelion precession, which is approximately 3% larger than the value reported by Baland et al. (2017). This minor discrepancy might be attributed to a potential double-counting of the static component of the tidal deformation effects in their approach. More significantly, our calculation of the tidally induced deviation from the Cassini plane results in a tilt that is 100 times smaller than the value reported by Baland et al. (2017). We suggest that the out-of-Cassini-plane offset may have been overestimated in their study due to an incorrect projection of the angular momentum equations onto the invariant plane.

Secondly, we obtain for the complete model the derivation of analytical equilibrium equations for Mercury’s rotation axis. We reproduce the equilibrium positions obtained numerically by Peale et al. (2014), which are compatible with the latest observations of Mercury’s rotation axis. We focus particularly on the influence of core flattening and CMB friction on both in-plane and out-of-plane offsets from the Cassini plane. We confirm the result of Margot et al. (2012), which concluded that if the core and mantle are too weakly coupled, it becomes impossible to explain the observed in-plane offset. As in Peale et al. (2014), we show that for a nearly spherical core, friction plays a dominant role, even more so than in the case of a more flattened core. This leads to a regime where the out-of-Cassini-plane offset becomes excessively large, rendering it incompatible with observations.

Finally, we identify a parameter space region where the linear approximation in Mercury’s orientation breaks down. This region is characterised by weak core-mantle friction and intermediate core flattening. In this regime, a bifurcation occurs, as described in the frictionless limit by Boué (2020), when the core angular momentum tilts beyond 30 degrees. Additionally, the core’s angular speed, forced by core-mantle friction, should significantly decrease, in contradiction with our assumption that the core and mantle angular speeds are equal.

Nevertheless, comparing our results with those of Peale et al. (2014) – which are not subject to the linear approximation – shows that a significant out-of-Cassini-plane deviation can still occur within the validity range of our model. This scenario assumes a nearly spherical core and a viscous relaxation time, driven by core-mantle friction, of the order of 107 days. In this situation, tidal deformation plays a minimal role compared to the core flattening and CMB friction.

Future work is still needed to constrain Mercury’s interior structure using the upcoming data from the BepiColombo space mission. This work will focus on incorporating a solid inner core, a realistic fluid rotation model for the outer core, a more complex rheological model, and a more refined orbital motion that goes beyond the uniform precession at constant inclination and eccentricity.

|

Fig. 3 Mantle’s in-plane obliquity without viscous dissipation at the CMB (τν → ∞). The curve labelled ‘linear’ was computed using the present model and represents a transverse view of the top line in Fig. 2a. The non-linear curve is from Boué (2020). |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Benoît Noyelles, whose valuable comments helped to improve the quality of the paper. C.R. is partially supported by FAPESP grant 2023/07076-4.

References

- Baland, R.-M., Yseboodt, M., Rivoldini, A., & Van Hoolst, T. 2017, Icarus, 291, 136 [Google Scholar]

- Bertone, S., Mazarico, E., Barker, M. K., et al. 2021, J. Geophys. Res. (Planets), 126, e06683 [Google Scholar]

- Boué, G. 2020, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 132, 21 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Correia, A. C. M., Ragazzo, C., & Ruiz, L. S. 2018, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 130, 51 [Google Scholar]

- Dumberry, M. 2021, J. Geophys. Res. (Planets), 126, e06621 [Google Scholar]

- Gastineau, M., & Laskar, J. 2011, ACM Commun. Comput. Algebra, 44, 194 [Google Scholar]

- Genova, A., Goossens, S., Mazarico, E., et al. 2019, Geophys. Res. Lett., 46, 3625 [Google Scholar]

- Genova, A., Hussmann, H., Van Hoolst, T., et al. 2021, Space Sci. Rev., 217, 31 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens, S., Renaud, J. P., Henning, W. G., et al. 2022, Planet. Sci. J., 3, 37 [Google Scholar]

- Konopliv, A. S., Park, R. S., & Ermakov, A. I. 2020, Icarus, 335, 113386 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson, I., & Dumberry, M. 2022, J. Geophys. Res. (Planets), 127, e07184 [Google Scholar]

- Margot, J. L., Peale, S. J., Jurgens, R. F., Slade, M. A., & Holin, I. V. 2007, Science, 316, 710 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margot, J.-L., Peale, S., Solomon, S., et al. 2012, J. Geophys. Res. (Planets), 117, E00L09 [Google Scholar]

- Mazarico, E., Genova, A., Goossens, S., et al. 2014, J. Geophys. Res.: Planets, 119, 2417 [Google Scholar]

- Ness, N. F., Behannon, K. W., Lepping, R. P., Whang, Y. C., & Schatten, K. H. 1974, Science, 185, 151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Noyelles, B., & Lhotka, C. 2013, Adv. Space Res., 52, 2085 [Google Scholar]

- Noyelles, B., Karatekin, Ö., & Rambaux, N. 2011, A&A, 536, A61 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Peale, S. J. 1976, Nature, 262, 765 [Google Scholar]

- Peale, S. J. 2005, Icarus, 178, 4 [Google Scholar]

- Peale, S. J., Yseboodt, M., & Margot, J. L. 2007, Icarus, 187, 365 [Google Scholar]

- Peale, S. J., Margot, J. L., & Yseboodt, M. 2009, Icarus, 199, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Peale, S. J., Margot, J.-L., Hauck, S. A., & Solomon, S. C. 2014, Icarus, 231, 206 [Google Scholar]

- Peale, S. J., Margot, J.-L., Hauck, S. A., & Solomon, S. C. 2016, Icarus, 264, 443 [Google Scholar]

- Ragazzo, C., & Ruiz, L. S. 2015, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 122, 303 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ragazzo, C., Boué, G., Gevorgyan, Y., & Ruiz, L. S. 2022, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 134, 10 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. E., Zuber, M. T., Phillips, R. J., et al. 2012, Science, 336, 214 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A., Oberst, J., & Hussmann, H. 2015a, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 123, 263 [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A., Oberst, J., Preusker, F., et al. 2015b, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 7881 [Google Scholar]

- Steinbrügge, G., Dumberry, M., Rivoldini, A., et al. 2021, Geophys. Res. Lett., 48, e89895 [Google Scholar]

- Verma, A. K., & Margot, J.-L. 2016, J. Geophys. Res.: Planets, 121, 1627 [Google Scholar]

- Wisdom, J., Peale, S. J., & Mignard, F. 1984, Icarus, 58, 137 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Here, we quote a refined value of the nodal precession from Stark etal. (2015a).

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Projected equilibrium spin axes on the orbital plane for varying core-mantle viscous friction, assuming a spherical core. a) Mantle spin axis coordinates. b) Core spin axis coordinates. The vertical line labelled Cassini plane in panel a) is the intersection of the Cassini plane with the orbital plane. Red dots indicate coordinates from Peale et al. (2014, Table 2). The observations are taken from Margot et al. (2012); Mazarico et al. (2014); Stark et al. (2015a); Verma & Margot (2016); Genova et al. (2019); Konopliv et al. (2020); Bertone et al. (2021). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Mantle’s in-plane obliquity εm1 (a) and deviation from the Cassini plane εm2 (b) as functions of the core flattening coefficient fc and viscous relaxation time τν. The white domains correspond to values that fall outside the colour scales. In these regions, the linear approximation is no longer valid and the equations of motions have to be solved treating the core’s in-plane obliquity and angular velocity non-linearly. Black crosses indicate the parameters considered by Peale et al. (2014), shown as red dots in our Figure 1. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Mantle’s in-plane obliquity without viscous dissipation at the CMB (τν → ∞). The curve labelled ‘linear’ was computed using the present model and represents a transverse view of the top line in Fig. 2a. The non-linear curve is from Boué (2020). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.