| Issue |

A&A

Volume 701, September 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A27 | |

| Number of page(s) | 11 | |

| Section | Astrophysical processes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554106 | |

| Published online | 02 September 2025 | |

General relativistic quasi-spherical accretion in a dark matter halo

1

School of Astronomy, Institute for Research in Fundamental Sciences (IPM), P.O. Box 19395-5531 Tehran, Iran

2

Departamento de Matemática da Universidade de Aveiro and Centre for Research and Development in Mathematics and Applications (CIDMA), Campus de Santiago, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

11

February

2025

Accepted:

4

July

2025

Context. The Bondi spherical accretion solution has been used to model accretion onto compact objects in a variety of situations, from the interpretation of observations to subgrid models in cosmological simulations.

Aims. We investigate how the presence of DM alters the dynamics and physical properties of accretion onto SMBHs on scales ranging from ∼10 pc to the event horizon.

Methods. In particular, we investigated Bondi-like accretion flows with zero and low specific angular momentum around SMBH surrounded by DM halos by performing 1D and 2.5D GRHD simulations using the BHAC.

Results. We find notable differences in the dynamics and structure of spherical accretion flows in the presence of DM. The most significant effects include increases in density, temperature, and pressure, as well as variations in radial velocity both inside and outside the regions containing DM or even the production of outflow.

Conclusions. This investigation provides valuable insights into the role of cosmological effects, particularly DM, in shaping the behavior of accretion flows and BHs. Our simulations are directly applicable to model systems with a high BH-to-halo mass ratio that are expected to be found at very high redshifts.

Key words: black hole physics / hydrodynamics / galaxies: halos / dark matter

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

The heart of each galaxy is home to SMBHs. These BHs grow when nearby gas and dust are swallowed by their deep gravitational wells. Despite the evident potential of SMBHs in characterizing objects at galactic centers, many aspects of their physics remain unknown. For example, existing models attempting to explain the origins of SMBHs fail to accurately predict their observed distribution in mass and distance (Kormendy & Ho 2013). One of the key questions with cosmological implications is how they so quickly increased in mass. Observed spectra can provide considerable information on the accretion systems (Abramowicz et al. 1988). It might not be sufficient to focus on luminous matter components such as gas, dust, and the accretion disk to explain this observed high growth rate.

It is thought that 85% of the mass in the Universe is invisible DM (Jarosik et al. 2011). Based on numerous observations and N-body simulations, it is now widely accepted that galactic centers contain a SMBH that is enclosed within a DM halo that extends to much larger distances for millions of light years (see, e.g. de Martino et al. 2020). An enormous body of theoretical and observational work supports the idea of the existence of DM halos around galaxies (Bertin 2014; Binney & Tremaine 2008). The most massive BHs are found at the centers of galaxies and grow during accretion phases, observed as AGN. Despite advances in understanding AGN properties and host galaxies, their connection to large-scale cosmic environments and DM halos remains unclear. Understanding how AGN activity is affected by these environments can provide important insights into SMBH fueling and feedback mechanisms (Powell et al. 2022). We aim to contribute to the understanding of the effects of the DM environment on the growth and coevolution of the central SMBH in a galaxy by studying the problem of spherical and quasi-spherical accretion onto a BH surrounded by a DM halo. In particular, we focus on the case of accretion onto SMBHs at the centers of elliptical galaxies. When modeling the accretion flow in the close vicinity of compact objects such as SMBHs, it becomes crucial to consider the gravitational field in a general relativistic fashion, with the spacetime around the object being described by a metric tensor that is a solution of the Einstein field equations. The simplest spacetime geometry that captures this scenario is that of a static spherically symmetric BH, that is, the Schwarzschild solution. When the spacetime is described around a BH surrounded by DM, it becomes necessary to consider nonvacuum solutions. The dynamics of the accretion flow can be significantly altered when different distributions of matter are present outside the BH. Different DM models might therefore have different observational signatures. Through different observations and simulations, we have a rough understanding of the distribution of DM in galaxies. Some of the most popular DM profiles in the literature are those of NFW (Navarro et al. 1996), Hernquist (Hernquist 1990), Jaffe (Jaffe 1983), and King (King 1972). Bondi accretion (Bondi 1952) and its relativistic generalization by Michel (Michel 1972) represents the conceptually simplest case of accretion, that of a spherically symmetric object in a uniform medium. The original model and some of its extensions are not only intrinsically interesting from a mathematical physics point of view, however, but also possess important astrophysical applications. For example, the growth of a primordial BHs can be inferred as a sequence of nearly stationary accretion stages of spherical accretion of ultrarelativistic gas (Lora-Clavijo et al. 2013). The formation, accretion, and growth of SMBHs in the early Universe have been investigated using the Bondi-accretion rate onto initial seed BHs with masses  that can evolve into a SMBHs with masses

that can evolve into a SMBHs with masses  (Moffat 2020). Furthermore, Bondi accretion can be used to calculate and estimate the mass of intermediate-mass BHs (Wrobel et al. 2018). In cosmological simulations, Bondi prescriptions are often used to estimate the rate at which gas accretes onto SMBHs (Davé et al. 2019; Ricotti 2007). In this model, accretion can be considered to start at the Bondi radius, where the gravitational potential of the SMBH dominates the thermal energy of the surrounding hot gases (Russell et al. 2015). The EHT observed the SMBHs at the core of the galaxy M 87*87 (from now on, M 87*87) and the Milky Way, the latter known as Sgr A*, producing images of the accreting plasma at the event-horizon scales (Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration 2019, 2022). The mass of M 87*87 is

(Moffat 2020). Furthermore, Bondi accretion can be used to calculate and estimate the mass of intermediate-mass BHs (Wrobel et al. 2018). In cosmological simulations, Bondi prescriptions are often used to estimate the rate at which gas accretes onto SMBHs (Davé et al. 2019; Ricotti 2007). In this model, accretion can be considered to start at the Bondi radius, where the gravitational potential of the SMBH dominates the thermal energy of the surrounding hot gases (Russell et al. 2015). The EHT observed the SMBHs at the core of the galaxy M 87*87 (from now on, M 87*87) and the Milky Way, the latter known as Sgr A*, producing images of the accreting plasma at the event-horizon scales (Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration 2019, 2022). The mass of M 87*87 is  , corresponding to a Bondi radius of approximately rB ∼ 0.12 kpc. Sgr A*, has a mass of

, corresponding to a Bondi radius of approximately rB ∼ 0.12 kpc. Sgr A*, has a mass of  and a Bondi radius of ∼0.1 pc (Falcke & Markoff 2013). Observations suggest that M 87*87 possesses a DM halo with a mass of approximately 1014 M⊙ with a characteristic scale of about 100 kpc (De Laurentis & Salucci 2022). Similarly, Sgr A* has an estimated halo mass of

and a Bondi radius of ∼0.1 pc (Falcke & Markoff 2013). Observations suggest that M 87*87 possesses a DM halo with a mass of approximately 1014 M⊙ with a characteristic scale of about 100 kpc (De Laurentis & Salucci 2022). Similarly, Sgr A* has an estimated halo mass of  within a radius of 20 kpc (Posti & Helmi 2019). In recent years, Bondi accretion has been generalized to include the effects of the gravitational field of the host galaxy with a central BH and DM halo, while still keeping the problem analytically tractable (Korol et al. 2016; Ciotti & Pellegrini 2017, 2018; Mancino et al. 2022).

within a radius of 20 kpc (Posti & Helmi 2019). In recent years, Bondi accretion has been generalized to include the effects of the gravitational field of the host galaxy with a central BH and DM halo, while still keeping the problem analytically tractable (Korol et al. 2016; Ciotti & Pellegrini 2017, 2018; Mancino et al. 2022).

We investigate the scenario of a nonrotating BH surrounded by DM that is accreting from a uniform medium. DM deforms the Schwarzschild geometry sufficiently to alter the structure of the accretion flow around the SMBH. In particular, we concentrate on DM distributed following the Hernquist and NFW profiles. We first perform a detailed comparison between the Newtonian (Bondi 1952) model and its general relativistic generalization by Michel (1972) by studying the analytical solution. Then, using GRHD simulations, we study spherical accretion from large (∼10 pc) scales onto the vicinity of the BH event horizon, exploring the influence of the DM halo on the mass-accretion rate, and the structure of the flow. We find that the effect of DM becomes more significant as the halo mass Mhalo and characteristic scale a0 increase. Finally, we extend Michel’s solution by considering a small amount of gas rotation in addition to the influence of the DM halo. Throughout this work, we adopt geometrized units (G = c = 1), so that the gravitational radius of the BH  and its gravitational timescale

and its gravitational timescale  take the value M, with M the BH mass. We use these value as our units of length and time.

take the value M, with M the BH mass. We use these value as our units of length and time.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we recall the main properties of the classical Bondi and Michel models. In Sect. 3 we introduce the DM density profile and derive the spherically symmetric metric of a BH surrounded by a DM halo. In Sect. 4 we briefly discuss the numerical setup. In Sect. 5 we discuss the results of 1D and 2.5D simulations. Finally, we summarize and discuss our results in Sect. 6.

2. Semi-analytic stationary solutions

2.1. Bondi model

A spherical symmetric steady-state accretion flow (with zero angular momentum and no magnetic field) onto a gravitating body was first described by Bondi 1952 under Newtonian physics and is often called the Bondi model. This model is foundational in understanding simple accretion processes. The flow is supposed to be steady and one-dimensional in the radial (r-)direction. The flow is further assumed to be inviscid, and magnetic and radiation fields are ignored. These assumptions limit the applicability of the simplest model to environments in which these effects are minimal. Under the Newtonian approximation, the continuity equation and the equation of motion are

respectively, where v is the flow velocity (negative for accretion), ρ is the density, p is the pressure, and Φ(r) is the gravitational potential. The polytropic relation  is assumed, where K and

is assumed, where K and  are constants. It is worth noting that when the polytropic exponent

are constants. It is worth noting that when the polytropic exponent  in the polytropic formula is the ratio of the constant pressure to constant volume specific heats, the flow performs an adiabatic reversible (i.e., isentropic) transformation, while for different values of

in the polytropic formula is the ratio of the constant pressure to constant volume specific heats, the flow performs an adiabatic reversible (i.e., isentropic) transformation, while for different values of  , the flow is polytropic, but not isentropic.

, the flow is polytropic, but not isentropic.

While in the classical Bondi model, Φ represents the potential of a point source, the inclusion of DM introduces additional gravitational effects that alter the density and velocity profiles. We can go beyond the original model and have Φ including the additional potential of a DM halo,

Integrating the above equations yields the continuity equation and the Bernoulli equation,

where Ṁ is the mass-accretion rate, and E is the Bernoulli constant. By considering the regularity condition at the sonic point, vc = cs, c, and fixing the gravitational potential, we can determine the location of the sonic point and the sound speed, and we subsequently determine the radial profiles for all hydrodynamic variables.

2.2. Mass-accretion rate

The mass-accretion rate plays a crucial role in accretion disk theory as it governs the accretion mode of BHs. In large-scale cosmological simulations, the Bondi accretion formula is commonly employed to estimate the BH accretion rate. It has also been found that DM is a major contributor to BH accretion physics and that its influence can be seen in the variation of the BH central energetics as an increase in the mass-accretion rate. The Bondi accretion rate, which characterizes the mass-accretion rate of transonic spherical accretion onto compact objects such as BHs, is determined by the gas density and temperature at the outer boundary in its Newtonian form. By defining the Bondi radius as rB = GM/cs, ∞2 (the sound speed cs, ∞ of the ambient gas is determined by its temperature), we can express the Bondi accretion rate as  . For

. For  , the constant

, the constant  is 0.25, while for

is 0.25, while for  , it is 1.12 (Park 2009).

, it is 1.12 (Park 2009).

Recent Event Horizon Telescope results targeted the M 87* BH and the center of our Galaxy, revealing images of M 87* and Sgr A* that were released in 2019 and March 2024, respectively. The accretion rate of M 87* is estimated to be  (Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration 2019), which is about one hundred times lower than the predicted Bondi accretion rate. Furthermore, the accretion rate of Sgr A* in simulations from Ressler et al. (2023) falls within the range

(Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration 2019), which is about one hundred times lower than the predicted Bondi accretion rate. Furthermore, the accretion rate of Sgr A* in simulations from Ressler et al. (2023) falls within the range  , which is consistent with previous estimates of the accretion rate onto Sgr A* and with estimates based on the EHT-observed flux. Chandra observations using ACIS-I, centered on the position of (Sgr A*), indicated that its accretion rate may be lower by one to two orders of magnitude than the estimated Bondi rate, which is approximately

, which is consistent with previous estimates of the accretion rate onto Sgr A* and with estimates based on the EHT-observed flux. Chandra observations using ACIS-I, centered on the position of (Sgr A*), indicated that its accretion rate may be lower by one to two orders of magnitude than the estimated Bondi rate, which is approximately  (Baganoff et al. 2003). While Bondi accretion is mathematically simple, it is insufficient for accurately describing real astrophysical systems, necessitating several modifications. One significant but less frequently discussed factor is the influence of a DM halo, which might affect the accretion rate.

(Baganoff et al. 2003). While Bondi accretion is mathematically simple, it is insufficient for accurately describing real astrophysical systems, necessitating several modifications. One significant but less frequently discussed factor is the influence of a DM halo, which might affect the accretion rate.

2.3. Michel accretion

The general relativistic version of the Bondi model is known as Michel accretion (Michel 1972). Instead of describing gravity by means of a potential, it is now understood as the effect of a curved spacetime described by the metric gμν, which is a solution to the Einstein equations. For a static spherically symmetric spacetime described by the coordinates xμ = (t, r, θ, ϕ), the line element

can be written in a general way as

where dΩ2 = dθ2 + sinθdϕ2.

The equations of relativistic hydrodynamics consist of the conservation of mass and energy-momentum (i.e., the divergence-free nature of the mass current and the stress-energy tensor), whose covariant expressions are

where ∇μ is the covariant derivative associated with the metric gμν, ρ is the fluid rest-frame density, and uμ is the fluid four-velocity. The stress-energy tensor of a perfect fluid can be expressed as

where h is the specific relativistic enthalpy, p is the pressure in the fluid frame, and gμν denotes the components of the inverse of the spacetime metric. Under the assumptions of stationarity and spherical symmetry, Eqs. (8) and (9) can be manipulated to obtain the general-relativistic analog of Eqs. (4) and (5), namely

where Ṁ and E are again constants. After assuming an equation of state and expressing the enthalpy in terms of the sound speed cs, we solved the two algebraic Eqs. (11) and (12) simultaneously for the fluid three-velocity vr = ur/Γ (where Γ is the Lorentz factor) and cs. This in turn allowed us to find the remaining fluid variables. More details on the solution of the Michel problem can be found, for instance, in Rezzolla & Zanotti (2013) for the case of a Schwarzschild BH and in Meliani et al. (2016) for a general spherically symmetric metric. In the next section, we focus on the particular case of the metric we used to describe a BH surrounded by a DM halo.

3. Spacetime geometry

We implemented the newly introduced metrics to investigate the impacts of DM on BH accretion. To account for the effect of the DM halo on the spacetime geometry, we constructed a metric that was consistent with the mass function

where ρDM is the matter density including the halo and the central SMBH. Similarly to Cardoso et al. (2022), we did not find m(r), but took it as given in such a way that was consistent with the DM profiles at large scales. For simplicity, the system was assumed to be spherically symmetric. Under these assumptions, a general static solution of the Einstein equations can be written in the form

where the radial function f(r) is related to the mass function by

The integral can be calculated numerically to keep the method flexible for any mass function, which corresponds to a specific DM profile. For this purpose, it is convenient to work in compacted coordinates to evaluate the integrand at infinity. Our compacted coordinate x is defined as

and the inverse transformation is

With these coordinates, the integral (15) becomes

which can be integrated numerically for a known m(x). In particular, to obtain the spacetimes used in this work, we performed the integration using Simpson’s rule. For the cases we considered, a small number of points (∼40) was sufficient to achieve convergence. In the next sections, we provide more details on the specific density profiles we studied.

3.1. Halo density profiles

A wide class of density distribution of a galactic halo in astrophysics can be written as a double power law (Merritt et al. 2006; Hernquist 1990; Jaffe 1983),

where a0 is the scale radius, and ρ0, DM is the scale density. If r ≪ a0, ρDM ∼ r−γ and if r ≫ a0, ρDM ∼ r−β. The parameter α controls the sharpness of the break. In order for the mass to be finite, it requires γ < 3 and β > 3.

The model with (α, β, γ)=(1, 4, 1) is called a Hernquist profile, while the model with (α, β, γ)=(1, 3, 1) is called the NFW profile. The Hernquist profile models mass distributions in elliptical galaxies, with a central concentration falling off as r−1 at small radii and as r−4 at large radii. In contrast, the NFW profile is commonly used for DM halos, with a central density decaying as r−1 at small radii and r−3 at large radii. Using both profiles can help us understand the role of DM in galactic centers and provide insights into how DM distribution influences the formation of galactic structure.

3.2. Hernquist profile

The Hernquist profile (Hernquist 1990) is applied for modeling the Sérsic profiles observed in bulges and elliptical galaxies (Konoplya & Zhidenko 2022) (hereafter KZ22). As a first step, we used the mass function inspired by the Hernquist profile that appeared in Cardoso et al. (2022). The BH+DM halo system can be modeled by the mass function

where M is the BH mass, Mhalo is the halo mass, and a0 is the characteristic scale of the galactic halo. In terms of the compacted coordinates, the mass function to be inserted in Eq. (18) reads

3.3. NFW profile

Although the Hernquist profile describes isolated DM halos, halos found in cosmological simulations are better fit by an NFW profile because of the continued infall from the cosmological background. For galaxies with the largest content of DM, the NFW model (Navarro et al. 1995, 1997) is mostly used KZ22.

The density profile of DM is the NFW profile obtained from numerical simulations based on DM and ΛCDM. We used the mass function inspired by the NFW profile that appeared in KZ22,

where

Here, s represents the truncation radius of the galactic halo. The truncation radius s sets the outer boundary of the halo beyond which the DM density is zero.

In terms of the compacted coordinates, the mass function reads

We adopted the density distribution Eq. (19), where the constant ρDM(a0) determines the total mass of the galactic halo KZ22,

We assumed  and set the truncation radius to s = 50 a0. Notably, for β > 3, the galaxy size can be considered infinite because the improper integral in Eq. (26) converges as s → ∞. When s is finite, to ensure a finite total mass, we assumed that the space beyond the galactic halo was empty, that is, ρDM(r > s)=0 similar to KZ22. As shown in Fig. 1, we plot the metric as a function of the radius in units of M.

and set the truncation radius to s = 50 a0. Notably, for β > 3, the galaxy size can be considered infinite because the improper integral in Eq. (26) converges as s → ∞. When s is finite, to ensure a finite total mass, we assumed that the space beyond the galactic halo was empty, that is, ρDM(r > s)=0 similar to KZ22. As shown in Fig. 1, we plot the metric as a function of the radius in units of M.

|

Fig. 1. Metric components g11 and α as functions of the radius r (in units of M) for the different models of a BH. The Schwarzschild metric is shown with the solid blue curves. The Hernquist and NFW metrics are also shown with the blue and red curves, respectively (solid and dashed lines). Both a0 and Mhalo are normalized to the BH mass M. |

Notably, the metric functions of a nonrotating BH embedded in DM deviate from those of a Schwarzschild BH in a vacuum. Near the event horizon, however, these deviations remain minimal due to the strong gravitational influence of the BH in this region. Moreover, the plots from both the Hernquist and NFW sections show that this deviation increases with increasing halo mass.

4. Simulation setup

To consider the effect of a galactic halo on the dynamics of the transonic spherical accretion flow, we performed a set of 1D to 2.5D ideal GRHD simulations by using the GRMHD code BHAC (Porth et al. 2017; Olivares et al. 2019). Here, 2.5D refers to simulations carried out in a two-dimensional domain while using all three components of the vector quantities, such as the velocity. We used a spherical polar grid in Schwarzschild coordinates with logarithmic spacing for better resolution at small radii.

There is only one sonic point rs/M in this type of solution, and we fixed it at 500. We performed 1D and 2.5D simulations and discuss the results in Sects. 5.1 and 5.2, respectively. For 1D simulations, we assumed zero angular momentum and set the outer boundary at r/M = 105. In 2.5D simulations, small amounts of angular momentum are incorporated, and the outer boundary was located at r/M = 103. To perform the 1D simulations, we considered an effective resolution (96). For each halo mass (Mhalo/M = 1 and Mhalo/M = 10), simulations were performed for two values of the length scale: a0/M = 80 and  . The 2D simulations were performed using different coordinate systems (see Sect. 3) with a resolution of Nr × Nθ = 104 × 96 over a computational domain defined by r/M ∈ [2.8, 103] and θ ∈ [0, π]. For 2.5D simulations, we set the halo mass to 1 and the length scale to a0/M = 100. Simulations were performed up to t/M = 106 and 5 × 103 for 1D and 2.5D, respectively. The details of the different runs are summarized in Table 1. The fluid followed an ideal equation of state with

. The 2D simulations were performed using different coordinate systems (see Sect. 3) with a resolution of Nr × Nθ = 104 × 96 over a computational domain defined by r/M ∈ [2.8, 103] and θ ∈ [0, π]. For 2.5D simulations, we set the halo mass to 1 and the length scale to a0/M = 100. Simulations were performed up to t/M = 106 and 5 × 103 for 1D and 2.5D, respectively. The details of the different runs are summarized in Table 1. The fluid followed an ideal equation of state with  .

.

Simulation parameters and results

5. Results

5.1. Test evolutions 1D

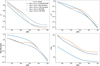

In this part, we carried out 1D simulations to explore dynamics in accretion flow with zero angular momentum. Figs. 2 and 3 illustrate the impact of a DM halo on the dynamics of accretion flows around SMBHs and compares these flows to those around a Schwarzschild BH in a vacuum. In Fig. 2, the halo mass is equal to the BH mass, while in Fig. 3, the halo mass is ten times higher than that of the BH. As the length scale increases, DM distribution extends farther and might affect the outer accretion regions more significantly. These values apply to both Figs. 2 and 3.

|

Fig. 2. Radial component of the spherical accretion parameters as a function of radius r (in units of M) in the presence of a DM halo. These 1D simulations are shown at t/M = 1 000 000 for different coordinates (Schwarzschild, Hernquist, and NFW), with the outer edge of the flow set at r/M = 105. The solid blue line represents the Schwarzschild profile, which represents a static nonrotating BH in a vacuum, without the influence of additional mass like DM. The dashed orange and gray lines correspond to the Hernquist DM profile, and the dot-dashed black and blue lines represent the NFW profile. Both a0 and Mhalo are normalized to the BH mass M. |

The top left panel illustrates the density profile as a function of radius, showing a density increase near the BH in the presence of a DM halo. The DM halo strengthens the gravitational potential near the BH and within the halo, causing a higher density in this region. The solid blue line shows the simulation in the Schwarzschild metric. The difference between the Hernquist and NFW profiles is in the steepness of their density distribution. The top right panel presents the radial velocity, which decreases inside the DM halo region as the gravitational effect of the halo weakens the inflow and increases outside it, where the gravitational effect of the halo is weaker. The bottom left panel shows the Mach number, which is the speed of the flow relative to the local sound speed, and the bottom right panel depicts the temperature. Temperature also increases due to the DM halo. One of the reasons for the increase in temperature in the presence of the halo is likely the additional gravitational potential energy from the DM, which heats the accreting matter. Notably, the deviations in these profiles are more pronounced when the halo mass is higher, as shown in Fig. 3. One of the striking results of our simulations is that the structure of the flow inside and outside the radius of the halo is different. A huge halo can therefore affect a wide region of the accretion flow and increase the mass-accretion rate significantly. In particular, we find an increase in the accretion rate by up to over 100% when DM halos are present, especially when the halo mass is high. We restricted our study to a small halo that is strictly aligned with the early Universe and high redshift (see the Sect. 5.3 for more details).

5.2. 2D simulation

In astrophysical accretion flows, the presence of angular momentum is anticipated, and it undoubtedly influences various flow properties, including the mass-accretion rate. The behavior of Bondi-like accretion flows with low angular momentum has also been extensively studied with large-scale hydrodynamic simulations (e.g. Olivares et al. 2023; Dihingia & Mizuno 2024; Proga & Begelman 2003; Suková et al. 2017). We primarily focused on the lower limits of angular momentum and conclude that the behavior of accretion flow differs significantly from that of high and zero angular momentum flows. The impact of rotation on DM-embedded accretion flows in the Newtonian regime on galactic scales was studied (Gan et al. 2019; Ciotti et al. 2022), while fully relativistic GRHD simulations in the regions near the BH to Bondi radius merit further investigation. It is plausible to expect that if the rotational support is insignificant at the Bondi radius, the impact of angular momentum on the mass-accretion rate is minimal.

In this section, we investigate the effect of both profiles of DM halo on accretion flow by evolving an accretion flow with angular momentum (l = 3.25, 4.25) in 2.5D, as illustrated in Figs. 4, 5 and 6. As we expected, the high angular momentum simulation (l = 4.25) shows noticeable shock and turbulence in the region close to the event horizon.

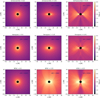

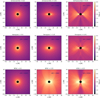

Figure 4 shows snapshots of logarithmic density maps for all simulations at t/M = 10 000 on the x − z plane. The snapshot at t/M = 10 000 represents a steady-state phase that provides the same conditions for comparison. The panels are organized as increasing angular momentum from left to right and different metrics from top to bottom (Schwarzschild, Hernquist, and NFW). The snapshots indicate denser accretion structures near the BH for the Hernquist and NFW profiles compared to a less dense pattern in the Schwarzschild metric. The density maps in the Schwarzschild panels indicate symmetry and uniformity, especially at l = 0, showing the simplicity of the accretion flow in Schwarzschild profiles. The differences in simulations with higher angular momentum are clear1.

|

Fig. 4. Snapshots of 2.5D GRHD simulations from the regions near the BH for different metrics, Schwarzschild, Hernquist, NFW (up to down) at time t/M = 10 000. The colors show the logarithm of the gas density ρ. From left to right, we show the zero angular momentum, l = 0, l = 3.25, l = 4.25. In all simulations, quasi-spherical accretion flow structures form around the BHs. Movies of the simulations are available online. |

Figure 5 displays snapshots of radial velocity in the x-z plane. The rows show from top to bottom three different metrics: the first row represents the Schwarzschild metric without DM, the second row includes the Hernquist profile, and the third row corresponds to the NFW profile of the DM halo. In these panels, the angular momentum values increase from left to right, with l = 0, l = 3.25, and l = 4.25, respectively. In these snapshots, blue regions indicate gas accreting into the BH, while red regions show outflows of matter being removed from the accretion flow. The results demonstrate that outflows become stronger in all metrics as the angular momentum increases. For l = 0, accretion occurs without any outflow. The presence of a DM halo enhances the strength of the outflow, as shown in this figure.

|

Fig. 5. Snapshots of 2D GRHD simulations of accretion and outflow in the regions near the BH for different metrics, Schwarzschild, Hernquist, NFW (up to down) at time t/M = 8000. The colors show the gas radial velocity ur. From left to right, we show the zero angular momentum, l = 0, l = 3.25, l = 4.25. In all simulations, quasi-spherical accretion flow structures form around the BHs. Movies of simulations are available online. |

Figure 6 shows a streamline of components of the velocity ux and uz, while the background color map presents the logarithm of the intensity of velocity in the direction of ϕ, that is, the azimuthal velocity (uϕ). We ran all three simulations related to Schwarzschild, Hernquist, and NFW profiles at t/M = 5000. In this case, we had a high angular momentum of l = 4.25. The streamlines show how the gas moves around the SMBH in each simulation. In the Schwarzschild profile, the flow is approximately radial with very little rotational structure. In the Hernquist profile, the onset of circularized motion is visible, which is indicative of the effects of angular momentum. The NFW profile exhibits more complex structures that may be related to a higher accretion rate. The mass-accretion rate for the NFW profile is higher than that of the Hernquist profile.

|

Fig. 6. Velocity streamlines in the x − z plane show components of the velocity ux and uz for Schwarzschild, Hernquist, and NFW profiles at t/M = 5000, with angular momentum l = 4.25. The color bar indicates the logarithmic intensity of uϕ (azimuthal velocity). Each panel displays the unique flow pattern of a gravitational profile. Movies of the simulations are available online. |

The simulations with the impact of DM halo are summarized in Table 1. We therefore performed many simulations with different values of the halo mass and characteristic length scale at both large and small scales. In Col. 9 of Table 1, we present the mass-accretion rate (in units of the Bondi accretion rate). Table 1 includes two simulation models: zero angular momentum, and low angular momentum. For the zero angular momentum 1D simulations, the outer radial boundary was set at r/M = 105. For the low angular momentum 2.5D simulations, the outer boundary was r/M = 103. We expect the mass-accretion rate for an accretion flow with angular momentum to be lower than in the case without angular momentum. Because our simulation with the NFW profile is not fully quasi-stationary, however, the value of 2.2672 in Table 1 is not entirely physical. In contrast, the Hernquist profile exhibits better stability, which indicates that it reaches quasi-stationary state faster than the NFW profile.

Figure 7 illustrates the variation in mass-accretion rate as influenced by the length scale and halo mass for the Hernquist and NFW profiles. The left panel corresponds to the Hernquist profile, and the right panel corresponds to the NFW profile. In these simulations, we explored angular momentum values of (l = 0) (solid lines) and (l = 3.25) (dashed lines). In both panels, the blue curves depict variations with respect to the length scale (lower x-axis), and the red curves represent changes as a function of the halo mass (upper x-axis). The figure shows that adding angular momentum reduces the mass accretion, as previously demonstrated in simulations and analytical studies (Ranjbar & Abbassi 2023). The simulations were performed at t/M = 100 000. Notably, the NFW profile exhibits a higher mass-accretion rate than the Hernquist profile. This trend is consistent in the zero and nonzero angular momentum scenarios. This illustrates the stronger gravitational binding of the NFW profile. We performed power-law fits to model the behavior of the mass-accretion rate for both the Hernquist and NFW profiles. The results of the fits are presented for different configurations (l = 0 and l = 3.25), and the coefficients of the fitted power law are provided for each case in Table 2.

|

Fig. 7. Mass-accretion rate normalized by Bondi accretion rate as a function of length scale (top x-axis, green) and halo mass (lower x-axis, blue) for Hernquist (left panel) and NFW (right panel) DM profiles. The solid lines represent zero angular momentum (l = 0), and the dashed lines indicate (l = 3.25). The solid orange and red lines are a power-law fit for these data. The coefficients of the power-law function are provided in Table 2. |

Power-law coefficients

These power-law fits accurately represent the behavior of the mass-accretion rate for the Hernquist and NFW profiles. The red curves capture the general trends of the mass-accretion rate with respect to the length scale, and the orange curves account for variations with halo mass. This analysis provides deeper insight into how the accretion rate changes with key parameters, which aids in the interpretation of physical phenomena in cosmology.

5.3. Relevance to observed systems

Even though the parameters of the BH-halo system we considered in our simulations are not representative of nearby galaxies, they describe the mass relation between DM halos and SMBHs at high redshift in the early Universe more closely. It is thought that the relation between BH mass M and the mass of the dark halos Mhalo in which it grows gives different insights into coevolution because it directly constrains the SMBH growth efficiency in halos. SMBHs in luminous QSOs expand much more rapidly than host halos owing to gas accretion, although we cannot rule out the possibility that undetected SMBHs may have a lower local M/Mhalo ratio. Preliminary evidence also suggests that smaller halos of  are becoming less efficient at forming SMBHs, possibly to the point of being unable to do so. Our simulation limit is in the special range of M/Mhalo that appears in some high-redshift QSOs such as J1044 − 0125 (Shimasaku & Izumi 2019). According to some observations, the M/Mhalo increases with redshift. Furthermore, the semi-analytical model of Shirakata et al. (2019) showed that the M/Mhalo increases with redshift. Some hydrodynamical simulations showed that Mhalo ∼ 1012 M⊙ halos can have an SMBH as massive as ∼109 M⊙ (e.g., Tenneti et al. 2019), but based on only a few examples. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has provided results for studying and understanding high-redshift quasars z ≥ 6 powered by rapidly accreting SMBHs with masses reaching up to ∼109 M⊙. For instance, the quasar J1120+0641 is driven by an exceptionally massive BH, which exhibits the highest reported BH-to-stellar mass ratio (M/M*) of approximately 0.54 (Marshall et al. 2025). It is a representative example of high-redshift quasars with SMBHs that we discussed in this section. Our results can be used to calibrate the efficiency of SMBH growth in the early cosmic epoch. This means that our simulation can be applied to a galaxy with a high redshift and in the early Universe. Two of the most well-known massive BHs, Sgr A* and M 87*, possess halo masses of

are becoming less efficient at forming SMBHs, possibly to the point of being unable to do so. Our simulation limit is in the special range of M/Mhalo that appears in some high-redshift QSOs such as J1044 − 0125 (Shimasaku & Izumi 2019). According to some observations, the M/Mhalo increases with redshift. Furthermore, the semi-analytical model of Shirakata et al. (2019) showed that the M/Mhalo increases with redshift. Some hydrodynamical simulations showed that Mhalo ∼ 1012 M⊙ halos can have an SMBH as massive as ∼109 M⊙ (e.g., Tenneti et al. 2019), but based on only a few examples. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has provided results for studying and understanding high-redshift quasars z ≥ 6 powered by rapidly accreting SMBHs with masses reaching up to ∼109 M⊙. For instance, the quasar J1120+0641 is driven by an exceptionally massive BH, which exhibits the highest reported BH-to-stellar mass ratio (M/M*) of approximately 0.54 (Marshall et al. 2025). It is a representative example of high-redshift quasars with SMBHs that we discussed in this section. Our results can be used to calibrate the efficiency of SMBH growth in the early cosmic epoch. This means that our simulation can be applied to a galaxy with a high redshift and in the early Universe. Two of the most well-known massive BHs, Sgr A* and M 87*, possess halo masses of  and

and  , respectively, with characteristic length scales of 20 kpc and 91.2 kpc (Posti & Helmi 2019; De Laurentis & Salucci 2022). The mass difference between the central BH and the halo is on the order of 104. A simulation of these systems therefore requires high-performance computing and significant resources. A detailed investigation of these objects, along with a comparison between simulation results and observational data, is reserved for future studies.

, respectively, with characteristic length scales of 20 kpc and 91.2 kpc (Posti & Helmi 2019; De Laurentis & Salucci 2022). The mass difference between the central BH and the halo is on the order of 104. A simulation of these systems therefore requires high-performance computing and significant resources. A detailed investigation of these objects, along with a comparison between simulation results and observational data, is reserved for future studies.

5.4. Thermal Bremsstrahlung emissivity

We aim to incorporate an observational perspective into our simulation to highlight the presence of DM and quantify its impact by comparing the Bremsstrahlung emission with previous works. Based on Chandra observations of massive BHs in galaxies (Baganoff et al. 2003), we can interpret the results in this paper, which helps us to validate our simulations. In these systems, the BH can accrete the hot interstellar medium (ISM) surrounding the galaxy. Bremsstrahlung (free-free radiation) is radiation emitted from charges accelerated in the Coulomb field of another charge. Energy is emitted at the expense of kinetic energy; thus, free-free radiation can cool the plasma. In most cases, the Bremsstrahlung radiation is produced at large radii, where the ion temperatures are not significantly different from the electron temperatures. We therefore considered only one temperature for the Bremsstrahlung radiation. Bremsstrahlung is the main cooling process for high T (> 107 K) plasma. By integrating over the whole spectrum, we only obtained that the nonrelativistic thermal Bremsstrahlung per unit area, eff, is given by

when no relativistic corrections are considered. The unit in CGS (erg s−1 cm−3, radiated power per cubic cm). gB is the frequency of the velocity-averaged Gaunt factor, which is in the range of 1.1 to 1.5,

The unit in CGS, erg/s. Γ, is the Lorentz factor. Similarly to Olivares et al. (2023), we chose the parameters for monoatomic hydrogen since the classical Bondi and ADAF models assume that the X-ray emission from Sgr A* is dominated by thermal Bremsstrahlung emission from electrons in a hot optically thin accretion flow (Baganoff et al. 2003). We calculated the Bremsstrahlung emission for Sgr A* using different density profiles. For Sgr A* with a BH mass 4.15 × 106 M⊙, the luminosity is equal to 7.63 × 1040 erg s−1 for the Hernquist profile and 2.92 × 1040 erg s−1 for the NFW profiles.

These values were scaled by a factor of (ni/106)2. These values are not realistic for Sgr A*, but they serve as an illustrative example. This demonstrates that the DM profile can influence observational properties, as evidenced by a more than twofold increase in the Bremsstrahlung luminosity for the considered halo mass.

6. Discussion and conclusions

A correlation between the mass of a BH and its host DM halo has been suggested in recent studies, which indicates a possible link between their formation and growth (Powell et al. 2022; Booth & Schaye 2010). Moreover, AGN feedback extends to larger scales, where it regulates the growth of the galaxy, BH, and halo together. We performed 1D to 2.5D GRHD simulations to model the spherical accretion flow around a BH surrounded by a DM halo. The presence of DM significantly alters the structure and dynamics of the accretion flow. It deviates from the characteristics observed in a vacuum scenario with a Schwarzschild BH. These accretion scenarios were evaluated using several cases, including accretion flow with zero and low angular momentum, for several quantities, and different DM halos were used to analyze their properties. The altered flow structures and enhanced accretion rates suggest that DM not only affects the large-scale dynamics of galaxies, but also profoundly affects the region near the SMBHs.

The gravitational influence of a DM halo on spherical accretion flows was analyzed by comparing the results with the exact general relativistic Bondi solution. Two independent models of DM halos were considered to evaluate their gravitational effects with the aim to reproduce general relativity Bondi accretion under more realistic conditions. These findings underscored the significant role of DM in modifying the physical properties of accretion flows. The main findings of this study are summarized below.

-

Within the DM halo region, the radial velocity of the accretion flow decreases, but it increases outside the halo. The presence of a DM halo also leads to an increase in density and pressure.

-

The temperature of the accretion flow increases by more than 100% in the presence of a DM halo for both the Hernquist and NFW profiles (∼1011 K near the event horizon).

-

The size and mass of the halo significantly affect the accretion flow structure. Larger and more massive halos (Mhalo/M = 10, a0/M = 100) induce stronger changes in the dynamics and structure of the accretion flow.

-

Simulations have shown that DM can cause the mass-accretion rate to deviate from the Bondi accretion rate. The mass-accretion rate, Ṁ, increases significantly in models that include a DM halo. Our simulation results showed an increase by ∼30% for the Hernquist profile and an increase over ∼50% for the NFW profile.

-

Conversely, a reduction in the mass-accretion rate was observed for models with higher angular momentum. This is consistent with results from previous studies.

-

The gravitational effects of DM profile or underlying space time geometry can significantly influence the intensity of the inflow and outflow in low-angular-momentum accretion flows. This affects the mass loss and the overall mass-accretion rate.

These results have important implications for understanding SMBHs growth because the altered accretion rates might affect the BH mass and the coevolution of BHs with their host galaxies. We restricted our study to a small halo that was strictly aligned with the early Universe and high redshift.

It remains unclear whether this change carries over to the ultra-Bondi radius regime of most astrophysical interest. It would therefore be interesting to explore the impact of a huge DM halo around the Bondi radius in future studies, as well as the effect of an interstellar gas, relative to the outer boundary. These model problems might help us to understand the connection between the problem studied here and the growth rate of BHs, in which a huge DM can dramatically change the dynamics of the accretion flow. It is called the accretion of hot gas in galaxy centers embedded in DM halo.

Future surveys will uncover millions of new AGNs, which will lead to significant advancements in understanding these phenomena. This will allow us to test and refine models at different cosmic epochs and will revolutionize our knowledge of AGNs and their environments. The studies will also unveil the underlying physical processes that drive the growth of BHs and galaxies within the cosmic web of DM. In future studies, we will test higher-resolution simulations that capture these phenomena. Generally, the results from our simulations represent an important step toward obtaining realistic models of relativistic accretion flows that have been immersed in DM halos.

Data availability

Movies associated with Figs. 4–6 are available at https://www.aanda.org

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Moscibrodzka and O. Porth for contributing to the initial idea and for the discussions. RR thanks S. Markoff, O. Porth, and R. Wijers at the University of Amsterdam, and M. Moscibrodzka at the Radboud University Nijmegen and C. Herdeiro at the University of Aveiro, for their hospitality. This work is supported by CIDMA under the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, https://ror.org/00snfqn58) Multi-Annual Financing Program for R&D Units. HO is supported by the Individual CEEC program - 5th edition funded by the FCT, and acknowledges support from the projects PTDC/FIS-AST/3041/2020, CERN/FIS-PAR/0024/2021, and 2022.04560.PTDC. This work has further been supported by the European Horizon Europe Staff Exchange (SE) programme HORIZON-MSCA-2021-SE-01 Grant No. NewFunFiCO-10108625.

References

- Abramowicz, M. A., Czerny, B., Lasota, J. P., & Szuszkiewicz, E. 1988, ApJ, 332, 646 [Google Scholar]

- Baganoff, F. K., Maeda, Y., Morris, M., et al. 2003, ApJ, 591, 891 [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, G. 2014, Dynamics of Galaxies (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Binney, J., & Tremaine, S. 2008, Galactic Dynamics, 2nd edn. (Princeton: Princeton University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Bondi, H. 1952, MNRAS, 112, 195 [Google Scholar]

- Booth, C. M., & Schaye, J. 2010, MNRAS, 405, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, V., Destounis, K., Duque, F., Macedo, R. P., & Maselli, A. 2022, Phys. Rev. D, 105, L061501 [Google Scholar]

- Ciotti, L., & Pellegrini, S. 2017, ApJ, 848, 29 [Google Scholar]

- Ciotti, L., & Pellegrini, S. 2018, ApJ, 868, 91 [Google Scholar]

- Ciotti, L., Ostriker, J. P., Gan, Z., et al. 2022, ApJ, 933, 154 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Davé, R., Anglés-Alcázar, D., Narayanan, D., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 486, 2827 [Google Scholar]

- De Laurentis, M., & Salucci, P. 2022, ApJ, 929, 17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- de Martino, I., Chakrabarty, S. S., Cesare, V., et al. 2020, Universe, 6, 107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dihingia, I. K., & Mizuno, Y. 2024, ApJ, 967, 4 [Google Scholar]

- Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (Akiyama, K., et al.) 2019, ApJ, 875, L1 [Google Scholar]

- Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration (Akiyama, K., et al.) 2022, ApJ, 930, L12 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Falcke, H., & Markoff, S. B. 2013, CQG, 30, 244003 [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Z., Ciotti, L., Ostriker, J. P., & Yuan, F. 2019, ApJ, 872, 167 [Google Scholar]

- Hernquist, L. 1990, ApJ, 356, 359 [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, W. 1983, MNRAS, 202, 995 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Jarosik, N., Bennett, C. L., Dunkley, J., et al. 2011, ApJS, 192, 18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- King, I. R. 1972, ApJ, 174, L123 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Konoplya, R. A., & Zhidenko, A. 2022, ApJ, 933, 166 [Google Scholar]

- Kormendy, J., & Ho, L. C. 2013, ARA&A, 51, 511 [Google Scholar]

- Korol, V., Ciotti, L., & Pellegrini, S. 2016, MNRAS, 460, 1188 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lora-Clavijo, F. D., Guzmán, F. S., & Cruz-Osorio, A. 2013, JCAP, 2013, 015 [Google Scholar]

- Mancino, A., Ciotti, L., & Pellegrini, S. 2022, MNRAS, 512, 2474 [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, M. A., Yue, M., Eilers, A.-C., et al. 2025, A&A, in press, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202452650 [Google Scholar]

- Meliani, Z., Grandclément, P., Casse, F., et al. 2016, CQG, 33, 155010P [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, D., Graham, A. W., Moore, B., Diemand, J., & Terzić, B. 2006, ApJ, 132, 2685 [Google Scholar]

- Michel, F. C. 1972, Ap&SS, 15, 153 [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, J. W. 2020, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2011.13440] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M., 1995, MNRAS, 275, 720 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M. 1996, ApJ, 462, 563 [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M. 1997, ApJ, 490, 493 [Google Scholar]

- Olivares, H., Porth, O., Davelaar, J., et al. 2019, A&A, 629, A61 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares, H. R., Mościbrodzka, M. A., & Porth, O. 2023, A&A, 678, A141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Park, M.-G. 2009, ApJ, 706, 637 [Google Scholar]

- Porth, O., Olivares, H., Mizuno, Y., et al. 2017, Comput. Astrophys. Cosmol., 4, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Posti, L., & Helmi, A. 2019, A&A, 621, A56 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, M. C., Allen, S. W., Caglar, T., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, 77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Proga, D., & Begelman, M. C. 2003, ApJ, 592, 767 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ranjbar, R., & Abbassi, S. 2023, ApJ, 954, 117 [Google Scholar]

- Ressler, S. M., White, C. J., & Quataert, E. 2023, MNRAS, 521, 4277 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rezzolla, L., & Zanotti, O. 2013, Relativistic Hydrodynamics (Oxford: Oxford University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Ricotti, M. 2007, ApJ, 662, 53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, H. R., Fabian, A. C., McNamara, B. R., & Broderick, A. E. 2015, MNRAS, 451, 588 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shimasaku, K., & Izumi, T. 2019, ApJ, 872, L29 [Google Scholar]

- Shirakata, H., Okamoto, T., Kawaguchi, T., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 482, 4846 [Google Scholar]

- Suková, P., Charzyński, S., & Janiuk, A. 2017, MNRAS, 472, 4327 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tenneti, A., Wilkins, S. M., Di Matteo, T., Croft, R. A. C., & Feng, Y. 2019, MNRAS, 483, 1388 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wrobel, J. M., Miller-Jones, J. C. A., Nyland, K. E., et al. 2018, AAS Meet., 231, 342.33 [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Metric components g11 and α as functions of the radius r (in units of M) for the different models of a BH. The Schwarzschild metric is shown with the solid blue curves. The Hernquist and NFW metrics are also shown with the blue and red curves, respectively (solid and dashed lines). Both a0 and Mhalo are normalized to the BH mass M. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Radial component of the spherical accretion parameters as a function of radius r (in units of M) in the presence of a DM halo. These 1D simulations are shown at t/M = 1 000 000 for different coordinates (Schwarzschild, Hernquist, and NFW), with the outer edge of the flow set at r/M = 105. The solid blue line represents the Schwarzschild profile, which represents a static nonrotating BH in a vacuum, without the influence of additional mass like DM. The dashed orange and gray lines correspond to the Hernquist DM profile, and the dot-dashed black and blue lines represent the NFW profile. Both a0 and Mhalo are normalized to the BH mass M. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Similar to Fig. 2, but the assumed mass of the halo is ten times the BH mass Mhalo/M = 10. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Snapshots of 2.5D GRHD simulations from the regions near the BH for different metrics, Schwarzschild, Hernquist, NFW (up to down) at time t/M = 10 000. The colors show the logarithm of the gas density ρ. From left to right, we show the zero angular momentum, l = 0, l = 3.25, l = 4.25. In all simulations, quasi-spherical accretion flow structures form around the BHs. Movies of the simulations are available online. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Snapshots of 2D GRHD simulations of accretion and outflow in the regions near the BH for different metrics, Schwarzschild, Hernquist, NFW (up to down) at time t/M = 8000. The colors show the gas radial velocity ur. From left to right, we show the zero angular momentum, l = 0, l = 3.25, l = 4.25. In all simulations, quasi-spherical accretion flow structures form around the BHs. Movies of simulations are available online. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Velocity streamlines in the x − z plane show components of the velocity ux and uz for Schwarzschild, Hernquist, and NFW profiles at t/M = 5000, with angular momentum l = 4.25. The color bar indicates the logarithmic intensity of uϕ (azimuthal velocity). Each panel displays the unique flow pattern of a gravitational profile. Movies of the simulations are available online. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Mass-accretion rate normalized by Bondi accretion rate as a function of length scale (top x-axis, green) and halo mass (lower x-axis, blue) for Hernquist (left panel) and NFW (right panel) DM profiles. The solid lines represent zero angular momentum (l = 0), and the dashed lines indicate (l = 3.25). The solid orange and red lines are a power-law fit for these data. The coefficients of the power-law function are provided in Table 2. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$$ \begin{aligned} \ln f(r) = - \int _{x(r)}^1 \frac{2m(x\prime )}{x\prime [x\prime - 2m(x\prime )(1 - x\prime )]} \mathrm{d}x\prime , \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa54106-25/aa54106-25-eq36.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \rho _{\rm DM}(r) = \frac{\rho _{\rm 0, DM}}{(r/a_0)^\gamma [1+ (r/a_0)^\alpha ]^{(\beta - \gamma )/\alpha }}, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa54106-25/aa54106-25-eq37.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} m(r) = \frac{r}{2} \left\{ 1 - \left( 1 - \frac{2M}{r} \right) \left[ 1 - \eta \frac{a_0}{r+a_0} - \eta \frac{a_0}{r} \ln \left( \frac{a_0}{r+a_0} \right) \right] \right\} , \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa54106-25/aa54106-25-eq40.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \eta&= \frac{2M_{\rm halo} s(a_0+s)}{a_0 \left(s-2M \right) \left[ s + (a_0+s) \ln \left( \frac{a_0}{a_0+s}\right) \right]} \,, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa54106-25/aa54106-25-eq42.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} m(x)&= \frac{x}{2(1 - x)} \bigg \{ 1 - \left( \frac{x - 2M(1 - x)}{x} \right) \nonumber \\&\times \left[ 1 - \eta \frac{a_0(1 - x)}{x + a_0 - a_0x} - \eta \frac{a_0(1 - x)}{x} \ln \left( \frac{a_0(1 - x)}{x + a_0(1 - x)} \right) \right] \bigg \}. \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa54106-25/aa54106-25-eq43.gif)