| Issue |

A&A

Volume 701, September 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L1 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| Section | Letters to the Editor | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555045 | |

| Published online | 01 September 2025 | |

Letter to the Editor

Positive feedback

II. How dust coagulation inside vortices can form planetesimals at low metallicity

1

New Mexico State University, Department of Astronomy, PO Box 30001 MSC 4500 Las Cruces, NM, 88001, USA

2

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Iowa State University, Ames, IA, 50010, USA

3

Institute for Advanced Computational Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY, 11794-5250, USA

4

Department of Astrophysics, American Museum of Natural History, 200 Central Park West, New York, NY, 10024, USA

⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

4

April

2025

Accepted:

5

July

2025

Context. The origin of planetesimals (∼100 km planet building blocks) has confounded astronomers for decades as numerous growth barriers appear to impede their formation. In a recent paper we proposed a novel interaction where the streaming instability (SI) and dust coagulation work in tandem: each changes the environment in a way that benefits the other. This mechanism proved effective at forming planetesimals in the fragmentation-limited inner disk, but much less effective in the drift-limited outer disk, and we concluded that dust traps may be key to forming planets at wide orbital separations.

Aims. Here we explore a different hypothesis, namely that vortices host a feedback loop in which a vortex traps dust and boosts dust coagulation, which in turn boosts vortex trapping.

Methods. We combined an analytic model of vortex trapping with an analytic model of fragmentation-limited grain growth that accounts for how dust concentration dampens gas turbulence.

Results. We find a powerful synergy between vortex trapping and dust growth. For α ≲ 10−3 and solar-like metallicity, this feedback loop consistently takes the grain size and dust density into the planetesimal formation region of the SI. Only in the regime of strong turbulence (α ≳ 3 × 10−3) does the system often converge to a steady state below the SI criterion.

Conclusions. The combination of vortex trapping with dust coagulation is an even more powerful mechanism than the one involving the SI. It is effective at lower metallicity and across the whole disk, anywhere that vortices form.

Key words: minor planets / asteroids: general / planets and satellites: formation / protoplanetary disks

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Despite decades of research, we still lack a coherent picture of planet formation. When stars are young, they are surrounded by a circumstellar disk of gas and dust. The dust component must give rise to planetary building blocks, such as planetesimals and embryos, that can later become rocky planets or the cores of giant planets. The current open question regarding the origin of these building blocks is fundamental: What is the mechanism that converts dust grains into kilometer-size bodies?

Once the disk is established, collisions between micron-sized grains leads to rapid growth until the grains reach millimeter to centimeter sizes, at which point they encounter two main barriers:

-

fragmentation barrier: As grains grow in size, their collision speed increases (Ormel & Cuzzi 2007) until it overcomes the adhesion of the grains (e.g., Güttler et al. 2010);

-

radial drift barrier: As grains grow, aerodynamic drag makes them drift toward the star with increasing speed (Weidenschilling 1977) until the drift timescale is shorter than the grain growth timescale (Birnstiel et al. 2012).

Current efforts to overcome these barriers generally focus on aerodynamic processes that concentrate dust. If the dust density is sufficiently high, the collective gravity of dust grains can lead to gravitational collapse, giving rise to full size planetesimals, leapfrogging intermediate sizes. Two prominent mechanisms include the SI, which collects dust into filaments (Youdin & Goodman 2005; Johansen et al. 2007), and vortices which trap dust (Barge & Sommeria 1995; Adams & Watkins 1995; Tanga et al. 1996). Both have been shown to produce self-gravitating dust clumps (e.g., Johansen et al. 2007; Lyra et al. 2008, respectively), but both have important limitations.

For a solar-like dust-to-gas ratio of Z = 0.01, dust growth models predict dust sizes of St ≤ 0.1 with a typical maximum value of St ≲ 0.01 (Drazkowska et al. 2021), where St = tstopΩK is the stopping time tstop normalized by the Keplerian frequency ΩK. However, the SI requires high (Z, St) to work (e.g., Carrera et al. 2015; Lim et al. 2024), and it has not been shown to form planetesimals for Z = 0.01, St = 0.01. Conversely, vortex trapping struggles for St = 0.03, Z = 0.01 and α = 3 × 10−4 (Lyra et al. 2024), where α is the turbulence parameter (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973). It is not been shown to work for realistic α ∼ 10−3 − 10−2, (Lesur & Papaloizou 2010; Lyra & Klahr 2011), Z = 0.01, and St = 0.01.

Furthermore, there are many known exoplanets around subsolar metallicity stars (e.g., GJ 9827c, and Kepler 37d & 408b are 0.2 − 2 M⊕ planets around stars with 0.003 ≤ Z⋆ ≤ 0.006), so any planetesimal formation model must work for Z < 0.01. Here we find a mechanism that bypasses these problems by simultaneously increasing dust concentration and St, while decreasing turbulence. Recently we proposed a mechanism where the SI and dust growth work in tandem, forming a feedback loop where each process enhances the other (Carrera et al. 2025, “Paper I”): The SI concentrates dust, which dampens turbulence (Johansen et al. 2009) and slows radial drift, promoting grain growth. In turn, grain growth makes the SI more effective. This feedback proved extremely effective in the fragmentation-limited regime, taking the system straight toward the region where the SI is thought to produce planetesimals. Instead, in the drift-limited regime the gains were modest.

Here we present a follow-up investigation with a different mix of mechanisms. We propose that vortex trapping also exhibits a feedback loop with dust growth. Since vortices also collect particles, they also dampen turbulence, which promotes grain growth. At the same time, larger grains (up to St ≲ 1) concentrate more strongly. Because vortices are true dust traps, this mechanism completely eliminates the radial drift barrier, making it especially important in the drift-limited outer disk.

This Letter is organized as follows. We present our model in Section 2. We describe how mass loading affects the fragmentation barrier, and how we combine grain growth and vortices into a feedback loop. Section 3 shows our final results. We discuss in Section 4 and draw conclusions in Section 5.

2. Model

We used the same model for turbulence dampening as in Paper I. We include a summary in Appendices A and B.

2.1. Vortex trapping

Inside a vortex the dust density follows a Gaussian profile with constant density along ellipses of equal aspect ratio (Lyra & Lin 2013). The density peaks at the center of the vortex, and reaches a maximum column dust-to-gas ratio of (see Appendix A)

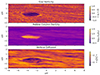

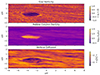

Figure 1 shows the vorticity, pebble column density, and vertical diffusion inside a vortex using the recent simulation data from Lyra et al. (2024). We note that the vortex has a distinct α, independent from the rest of the disk. Vortices produce their own turbulence via the elliptic instability (Lesur & Papaloizou 2010; Lyra & Klahr 2011). We also note the dust concentration inside the vortex with a peak near the center. Lyra et al. (2024) showed that their runs have maximum dust density consistent with Equation (1), at least up to the point where gravitational instability leads to collapse. To estimate the vortex trapping timescale, we start with the drift velocity of solid grains relative to the gas inside a vortex (Lyra & Lin 2013)

|

Fig. 1. Gas vorticity (top), pebble column density (middle), and vertical diffusion (bottom) for the 5123 simulation of Lyra et al. (2024). |

where h is enthalpy (defined as dh = dP/ρg, where P is pressure). We refer to Lyra & Lin (2013) for the full expression of ∇h inside the vortex, but the key result is that, for a typical vortex aspect ratio of 4, HΩK2 ≤ |∇h|≤4HΩK2 at the boundary, decreasing toward zero at the center. We further note that, in general, ∇h does not point exclusively toward the center of the vortex, so that the “radial” speed is vrad ≤ vdrift 1. Nonetheless, these constraints provide a useful ballpark estimate of the radial drift rate of solid grains

We let tZ be the vortex trapping timescale. Again, for a vortex with an aspect ratio of 4, the radial distance traversed by the grains is between H and 4H, so that

Comparing this expression against the simulations of Lyra et al. (2024), we find support for the tZ ∝ 1/St scaling, and indeed we find that tZ appears to be in the vicinity of tZ ∼ 4(St ΩK)−1. To cover the range of uncertainty in tZ, we ran our semi-analytic model twice, spanning an order of magnitude in tZ

It is worth noting that vortex trapping cannot continue indefinitely. When St ≫ 1, solid grains can no longer be trapped and escape the vortex (e.g., Raettig et al. 2015). In practice, we only explore the parameter space for St ≤ 0.1 because that is the most relevant region for determining whether the local conditions are consistent with planetesimal formation via the SI.

2.2. Vertical sedimentation

Next, we added an expression for dust sedimentation that accounts for mass loading. A common approach is to model ρp(z) as a Gaussian profile with scale height  so that the midplane dust-to-gas ratio is given by ϵ = Z(H/Hp) (Youdin & Lithwick 2007). However, this expression does not account for mass loading. Using the colloid approximation, Yang & Zhu (2020) defined the effective scale height of the dust-gas mixture

so that the midplane dust-to-gas ratio is given by ϵ = Z(H/Hp) (Youdin & Lithwick 2007). However, this expression does not account for mass loading. Using the colloid approximation, Yang & Zhu (2020) defined the effective scale height of the dust-gas mixture  , and Lim et al. (2024) showed that

, and Lim et al. (2024) showed that

is a better predictor of the dust scale height. The (Π/5)2 term estimates the amount of turbulence caused by the SI, ignoring the effect of St. For this work we made two further modifications. First, we assume that inside the vortex the SI is not the dominant source of turbulence so that the (Π/5)2 term can be neglected. Second, we use Equation (B.3) for  instead of the colloid approximation. The two expressions agree for St ≪ 1. This gives us an expression for the midplane dust-to-gas ratio that is valid even when neither St nor ϵ are negligible:

instead of the colloid approximation. The two expressions agree for St ≪ 1. This gives us an expression for the midplane dust-to-gas ratio that is valid even when neither St nor ϵ are negligible:

Equation (7) assumes that the dust has a Gaussian profile. The true profile is more centrally peaked (Lim et al. 2024), meaning that Equation (7) is a conservative estimate. This is a quadratic on ϵ. We let ζ ≡ Z2(1 + St/α)/(1 + St) and solve

It should be noted that we did not include Equation (1) in this expression. That would be a good option if we were to treat St as a static quantity, but we are interested (St, Z) as dynamic quantities that evolve together and respond to one another. As a result, the expressions for Stfrag (Equation B.4) and Zmax (Equation 1) are dynamic targets that the system is steadily moving toward. This is described in more detail in the next section.

2.3. Feedback loop

The feedback loop arises from the co-evolution of dust growth, vortex trapping, and sedimentation, as each process changes the environment for the others. The model parameters are the column dust-to-gas ratio Zdisk = 0.01, the turbulence parameter α ∈ [10−4, 3 × 10−3], and the classic fragmentation barrier Stx ∈ [0.01, 0.04]. Using Stx as an input allows us to explore the problem without assuming a particular disk model. However, as a point of reference, for the passive disk of Chiang & Youdin (2010) at 40 AU the associated fragmentation velocity is

We recall that our objective is the formation of planetesimals in the drift-dominated outer disk. Therefore, dust grains enter the vortex with a small drift-limited grain size St0 < Stx, and then grow inside the vortex. For the sake of simplicity, we set St0 ≡ 0.1Stx, initialize ϵ with Equation (8), and apply the following algorithm:

-

Update Stfrag, tgrow, Zmax, tZ (Equations B.4, B.6, 1, and 4);

-

Let Δt = 0.1min(tZ, tgrow) be the iteration timestep;

-

Update (St, Z) at the same time:

-

St = min[Stmax,St⋅exp(Δt/tgrow)]

-

Z = min[Zmax,Z⋅exp(Δt/tZ)]

-

-

Update ϵ (Equation 8).

3. Results

Figure 2 shows the evolution of (St, ϵ) at the center of the vortex for 24 simulations. We explored a range of turbulence values 10−4 ≤ α ≤ 3 × 10−3, and vortex trapping timescales 1 ≤ tZ(StΩK)≤10. Every simulation has Z = 0.01. We were mainly interested in vortices in the outer disk, where dust grains are limited by radial drift instead of fragmentation. That means that dust grains might enter the vortex well below the fragmentation limit. To capture this, we set the initial grain size to St0 = 0.1Stx, where Stx is the value of the fragmentation limit most often encountered in the literature (Equation B.5). We treat Stx as an input parameter so that our analysis remains agnostic to the disk model.

|

Fig. 2. Growth tracks for a range of grain sizes St, levels of turbulence α, and vortex trapping timescales tZ. Every run has Z = 0.01. The vertical dashed lines are Stx, but the growth tracks start at St0 = 0.1Stx as a proxy for the small drift-limited grains entering the vortex. Solid circles mark the start of the growth tracks and open circles mark every 100 orbits. The green region is the SI planetesimal formation (Lim et al. 2024). Most scenarios result in growth tracks that reach this region. However, for large α and small Stx, the growth tracks converge to a steady state outside the planetesimal formation region (the thick circles are multiple iterations plotted on top of each other). As a point of reference, we added the associated fragmentation velocity vfrag for some Stx values for the passive disk of Chiang & Youdin (2010) at 40 AU. |

First and foremost, we find that this mechanism is extremely effective. Nearly every scenario leads to (St, ϵ) evolution tracks that enter the planetesimal formation region for the SI (green region; Lim et al. 2024). We find that vortex trapping + dust growth is a far more powerful mechanism than the SI + dust growth that we explored in Paper I. The mechanism in Paper I was ineffective in the drift-limited regime and required Z > 0.01 in the fragmentation-limited regime. Replacing the SI with vortices allows us to run all models with Z = 0.01. A companion work (Eriksson et al. 2025) shows that this mechanism can form planetesimals in the ultra-low metallicity disks of the early universe (Z ≥ 0.0004).

Second, we find that this mechanism can stall for strong turbulence relative to the grain size (α = 3 × 10−3, Stx ≤ 0.02 in Figure 2). It is worth noting that the vortex in Figure 1 already exhibits some turbulence dampening. In Lyra et al. (2024) the low-dust vortex had α ∼ 3 × 10−3 and the high-dust vortex had α ∼ 3 × 10−4, showing that dust dampens turbulence. However, their runs did not include coagulation, so they do not model the full effect of the mechanism presented in this Letter.

4. Discussion

4.1. Bouncing barrier versus dust traps

Perhaps the most important caveat is that grain sizes may be limited by bouncing rather than fragmentation. Meaning that growth stalls because grain collisions result in bouncing instead of sticking (Zsom et al. 2010). Importantly, if present, the bouncing barrier can lead to grains that are much smaller than those of the fragmentation limit (Zsom et al. 2010). However, it is not clear that this is the case. Whether collisions lead to sticking or bouncing depends on the detailed properties of the grains, such as their shape, surface tension, and porosity. Furthermore, Jungmann & Wurm (2021) have made a strong case that the bouncing barrier may be overcome by electrostatic forces.

Suppose that the bouncing barrier is present. The bouncing barrier resembles fragmentation in that they are both a limit on the collision speed between grains  . The critical difference is that bounce-limited grains are around an order of magnitude smaller (Dominik & Dullemond 2024). That means that the (St, ϵ) evolution tracks should have a similar shape to those in Figure 2, but will require either higher Z or lower α to reach the planetesimal formation region.

. The critical difference is that bounce-limited grains are around an order of magnitude smaller (Dominik & Dullemond 2024). That means that the (St, ϵ) evolution tracks should have a similar shape to those in Figure 2, but will require either higher Z or lower α to reach the planetesimal formation region.

This leads us to an important process that we omitted: pebble flux. We kept the total dust mass inside the vortex constant. In a real disk there is a steady influx of dust grains drifting from the outer disk, which are captured by the vortex. Therefore, Z grows over the lifetime of the vortex. This might be the key to overcoming the bouncing barrier if it is present.

5. Conclusions

We presented a novel mechanism where dust growth and vortex trapping work in tandem, as each one changes the environment in a way that enhances the other. Vortices eliminate the radial drift barrier and concentrate grains, which dampens turbulence. Lower turbulence allows fragmentation-limited grains to grow, and larger grains concentrate more strongly. This new interaction is potentially more powerful than that involving the SI that we reported in Paper I. Our conclusions are as follows:

-

Unlike the mechanism described in Paper I, the one presented here is effective for Z = 0.01 and St = 0.01 (Figure 2), making it fully compatible with dust evolution models.

-

The mechanism presented here is active wherever vortices form. Crucially, it is active in the drift-dominated outer disk, where the mechanism of Paper I is not effective.

We did find that, for sufficiently high turbulence (α ≥ 3 × 10−3; higher than suggested by vortex simulations) the system can stall below the planetesimal formation threshold. However, in a real disk this would be mitigated by the fact that vortices continuously trap grains as they drift from the outer disk. The total dust mass in the vortex increases for as long as the vortex lives.

Altogether, the combination of vortices and dust growth in a feedback loop appears to bridge the gap between the dust growth barriers and planetesimal formation mechanisms. This novel mechanism works entirely within the (St, Z) constraints predicted by dust evolution models, and it is effective anywhere that vortices form.

Acknowledgments

DC, WL, and JBS acknowledge support from NASA under Emerging Worlds through grant 80NSSC25K7414. J.L. acknowledges support from NASA under the Future Investigators in NASA Earth and Space Science and Technology grant 80NSSC22K1322. LE acknowledges the support from NASA via the Emerging Worlds program (80NSSC25K7117), as well as the Institute for Advanced Computational Science Postdoctoral Fellowship.

References

- Adams, F. C., & Watkins, R. 1995, ApJ, 451, 314 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barge, P., & Sommeria, J. 1995, A&A, 295, L1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Birnstiel, T., Klahr, H., & Ercolano, B. 2012, A&A, 539, A148 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, D., Johansen, A., & Davies, M. B. 2015, A&A, 579, A43 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Carrera, D., Lim, J., Eriksson, L. E. J., Lyra, W., & Simon, J. B. 2025, A&A, 696, L23 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, P., & Oishi, J. S. 2010, ApJ, 721, 1593 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-W., & Lin, M.-K. 2018, MNRAS, 478, 2737 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, E., & Youdin, A. N. 2010, Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 38, 493 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cuzzi, J. N., Dobrovolskis, A. R., & Champney, J. M. 1993, Icarus, 106, 102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dominik, C., & Dullemond, C. P. 2024, A&A, 682, A144 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Drazkowska, J., Stammler, S. M., & Birnstiel, T. 2021, A&A, 647, A15 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, L. E. J., Menon, S., Carrera, D., Lyra, W., & Burkhart, B. 2025, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2503.11877] [Google Scholar]

- Güttler, C., Blum, J., Zsom, A., Ormel, C. W., & Dullemond, C. P. 2010, A&A, 513, A56 [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, A., Oishi, J. S., Mac Low, M.-M., et al. 2007, Nature, 448, 1022 [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, A., Youdin, A., & Mac Low, M.-M. 2009, ApJ, 704, L75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann, F., & Wurm, G. 2021, A&A, 650, A77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Laibe, G., & Price, D. J. 2014, MNRAS, 440, 2136 [Google Scholar]

- Lesur, G., & Papaloizou, J. C. B. 2010, A&A, 513, A60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lim, J., Simon, J. B., Li, R., et al. 2024, ApJ, 969, 130 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.-K., & Youdin, A. N. 2017, ApJ, 849, 129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lyra, W., & Klahr, H. 2011, A&A, 527, A138 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lyra, W., & Lin, M.-K. 2013, ApJ, 775, 17 [Google Scholar]

- Lyra, W., Johansen, A., Klahr, H., & Piskunov, N. 2008, A&A, 491, L41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lyra, W., Yang, C.-C., Simon, J. B., Umurhan, O. M., & Youdin, A. N. 2024, ApJ, 970, L19 [Google Scholar]

- Ormel, C. W., & Cuzzi, J. N. 2007, A&A, 466, 413 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Raettig, N., Klahr, H., & Lyra, W. 2015, ApJ, 804, 35 [Google Scholar]

- Schräpler, R., & Henning, T. 2004, ApJ, 614, 960 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shakura, N. I., & Sunyaev, R. A. 1973, A&A, 24, 337 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.-M., & Chiang, E. 2013, ApJ, 764, 20 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tanga, P., Babiano, A., Dubrulle, B., & Provenzale, A. 1996, Icarus, 121, 158 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Voelk, H. J., Jones, F. C., Morfill, G. E., & Roeser, S. 1980, A&A, 85, 316 [Google Scholar]

- Weidenschilling, S. J. 1977, MNRAS, 180, 57 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.-C., & Zhu, Z. 2020, MNRAS, 491, 4702 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Youdin, A. N., & Goodman, J. 2005, ApJ, 620, 459 [Google Scholar]

- Youdin, A. N., & Lithwick, Y. 2007, Icarus, 192, 588 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zsom, A., Ormel, C. W., Güttler, C., Blum, J., & Dullemond, C. P. 2010, A&A, 513, A57 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Vortex trapping

Here we present a concise high-level derivation of Equation 1; we skipped some details that can be found in Lyra & Lin (2013). In addition to vertical sedimentation, a vortex leads to a horizontal concentration of pebbles. The steady-state dust density was also shown to have Gaussian stratification in both midplane directions. Since each Gaussian contributes a  factor, the column density is enhanced by (1 + St/α).

factor, the column density is enhanced by (1 + St/α).

We start by introducing coordinates (a, ν), where a is the semiminor axis of ellipses with equal aspect ratio and ν is the azimuth angle in the vortex reference frame. The conversion to local Cartesian coordinates (x, y) in the vortex frame is

where χ > 1 is the aspect ratio of the vortex. The Jacobian of this coordinate transformation is

Thus, the total dust mass in the vortex is

where |J|=aχ is the determinant of the Jacobian. The gas mass has the same expression. In this model ρp and ρg are constant along ν. For this Appendix, we are not interested in the vertical density profile as we treat it differently from Lyra & Lin (2013) to account for mass loading. Therefore, we let ρg, max(z) and ρp, max(z) be the gas and dust densities at the center of the vortex, but we do follow Lyra & Lin (2013) in modeling the density as Gaussian on a:

Here Hg = H/f(χ),  , and f(χ) is a factor of order unity (Lyra & Lin 2013). Therefore,

, and f(χ) is a factor of order unity (Lyra & Lin 2013). Therefore,

We let Zdisk ≡ mp/mg and Zmax = (∫ρp, max(z) dz) ÷ (∫ρg, max(z) dz). We divide Equations A.8 and A.9 and we obtain

Appendix B: Mass loading and the fragmentation barrier

We used the same model of turbulence dampening as in Paper I, and we refer to that paper for details. What follows is a short summary of the model.

The most common way to model mass loading is to treat the gas-dust mixture as a colloidal suspension where dust contributes to the inertial of the fluid, but not to its pressure (Chang & Oishi 2010; Shi & Chiang 2013; Laibe & Price 2014; Lin & Youdin 2017; Chen & Lin 2018). This approach is valid in the limit as St → 0, but for our investigation we are interested in the case where St is not negligible, so that the fluid might not be well approximated by a colloid. In Paper I we approach the problem from the point of view of energy conservation, where there is a finite energy source that has to be partitioned between the gas and dust components,

where vg and vp are the root-mean-squared velocities of the gas and dust and ϵ is the dust-to-gas ratio. Using the fact that  (Voelk et al. 1980; Cuzzi et al. 1993; Schräpler & Henning 2004), Paper I showed that the gas velocity can be expressed as

(Voelk et al. 1980; Cuzzi et al. 1993; Schräpler & Henning 2004), Paper I showed that the gas velocity can be expressed as

where  is the effective sound speed of the gas-dust mixture. In the limit as St → 0, Equations B.2 and B.3 reduce to the colloid approximation.

is the effective sound speed of the gas-dust mixture. In the limit as St → 0, Equations B.2 and B.3 reduce to the colloid approximation.

The fragmentation barrier occurs when the collision speed between grains  (Ormel & Cuzzi 2007) reaches the fragmentation speed vfrag of the grain material. Combined with Equation B.2 we obtain

(Ormel & Cuzzi 2007) reaches the fragmentation speed vfrag of the grain material. Combined with Equation B.2 we obtain

where Stx is the usual definition of Stfrag commonly found in the literature. In other words, mass loading boosts the fragmentation barrier by a factor of 1 + ϵ/(1 + St). Birnstiel et al. (2012) derive the grain growth rate tgrow = 1/(ZΩK). For dust growth inside a vortex we replace this with

where ΩV is the vortex frequency. In practice, ΩV ≈ ΩK, and we adopt the typical value of ΩV = 0.5ΩK (Lyra & Lin 2013).

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Gas vorticity (top), pebble column density (middle), and vertical diffusion (bottom) for the 5123 simulation of Lyra et al. (2024). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Growth tracks for a range of grain sizes St, levels of turbulence α, and vortex trapping timescales tZ. Every run has Z = 0.01. The vertical dashed lines are Stx, but the growth tracks start at St0 = 0.1Stx as a proxy for the small drift-limited grains entering the vortex. Solid circles mark the start of the growth tracks and open circles mark every 100 orbits. The green region is the SI planetesimal formation (Lim et al. 2024). Most scenarios result in growth tracks that reach this region. However, for large α and small Stx, the growth tracks converge to a steady state outside the planetesimal formation region (the thick circles are multiple iterations plotted on top of each other). As a point of reference, we added the associated fragmentation velocity vfrag for some Stx values for the passive disk of Chiang & Youdin (2010) at 40 AU. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$$ \begin{aligned} t_Z \in \left[\frac{1}{\mathrm{St}\,\Omega _{\rm K}}, \frac{10}{\mathrm{St}\,\Omega _{\rm K}}\right]. \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa55045-25/aa55045-25-eq5.gif)