| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A305 | |

| Number of page(s) | 12 | |

| Section | Atomic, molecular, and nuclear data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555216 | |

| Published online | 24 December 2025 | |

Gas-phase formation routes of dimethyl sulfide in the interstellar medium

1

Dipartimento di Chimica, Biologia e Biotecnologie, Università degli Studi di Perugia, Via Elce di Sotto,

8,

06123

Perugia,

Italy

2

Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile ed Ambientale, Università degli Studi di Perugia,

via G. Duranti,

Perugia,

Italy

3

Master-Tec,

Via Gerardo Dottori 94,

06132

Perugia,

Italy

4

Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS,

Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG),

38000

Grenoble,

France

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

18

April

2025

Accepted:

22

October

2025

Context. Dimethyl sulfide (DMS; CH3 SCH3) is an organosulfur compound that has been suggested as a potential biosignature in exoplanetary atmospheres. In addition to its tentative detections toward the sub-Neptune planet K2-18b, DMS has been detected in the coma of the 67/P comet and toward the galactic-center molecular cloud G+0.693-0.027. However, its formation routes have not been characterized yet.

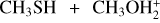

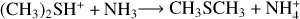

Aims. In this work, we aim to investigate five gas-phase reactions (the ion-molecule reactions CH3SH + CH3SH2+, CH3OH + CH3SH2+, CH3SH + CH3OH2+, (CH3)2SH+ + NH3, and the CH3+CH3S radiative association) in order to characterize DMS formation routes in shocked molecular clouds and star-forming regions.

Methods. We performed dedicated quantum and kinetics calculations to derive the potential energy surfaces of these reactive systems and evaluate the reaction rate coefficients as a function of temperature to be included in astrochemical models.

Results. Among the investigated processes, the reaction between methanethiol (CH3SH) and protonated methanol (CH3OH2+), possibly followed by a gentle proton transfer to ammonia, is a compelling candidate to explain the formation of DMS in the galactic-center molecular cloud G+0.693−0.027. The CH3+CH3S radiative association does not seem to be a very efficient process, with the exclusion of cold clouds, provided that the thiomethoxy (CH3 S) and methyl radical are available.

Conclusions. This work does not directly address the potential formation of DMS in the atmospheres of exoplanets. However, it clearly indicates that there are efficient abiotic formation routes of this interesting species. Furthermore, the characterization of the potential energy surface for the CH3+CH3 S radiative association supports the recent suggestion that DMS could be formed via photolysis in exoplanetary atmospheres.

Key words: astrochemistry / molecular processes / ISM: abundances / ISM: molecules

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

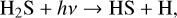

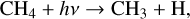

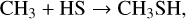

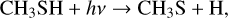

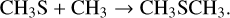

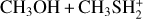

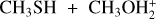

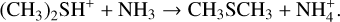

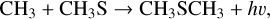

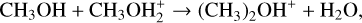

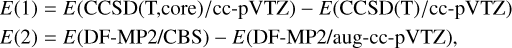

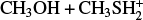

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS; CH3SCH3) is an organosulfur compound that has been considered as a potential biosignature in exoplanetary atmospheres since most emission sources of atmospheric DMS on Earth are associated with life (Bentley & Chasteen 2004; Barnes et al. 2006; Stefels et al. 2007), with the main contribution coming from microbial degradation of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (C5H10O5S) (Stefels et al. 2007). Since there are no significant geological sources on Earth, DMS is considered to have less likely false positives than other species (Pilcher 2003; Seager et al. 2013) and has been proposed specifically as a biosignature for identifying life on habitable exoplanets with H2-rich atmospheres (Catling et al. 2018; Seager et al. 2013), including the so-called Hycean worlds that may host habitable oceans (Madhusudhan et al. 2021). Infrared spectra recorded by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) NIRISS and NIRSpec instruments in the 0.9−5.2 μm range led to a tentative detection of DMS in the atmosphere of the exoplanet K2-18b, a Hycean-world candidate (Madhusudhan et al. 2023). Using the JWST MIRI LRS instrument in the 6−12 μm range, a confirmation of that first detection was recently reported with the additional tentative detection of other molecules, including dimethyl disulfide (DMDS), methanethiol (CH3SH), phosphine (PH3), and methanol (CH3OH) (Madhusudhan et al. 2025). Together with the simultaneous observation of CO2 and CH4 (which suggests an atmosphere far from the thermochemical redox equilibrium) and the missing detection of NH3 and CO, the tentative detection of DMS drew a lot of attention for the potential indication of life. Nevertheless, the assumption that DMS can only be produced by life has been challenged by its identification in astrophysical environments where biological activity is not expected. Indeed, the confirmed identification of DMS in the 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet by Hänni et al. (2024), followed by the detection of DMS in the interstellar medium (ISM) toward the galactic-center molecular cloud G+0.693-0.027 by Sanz-Novo et al. (2025) clearly indicated that DMS can be formed abiotically. Drawing an analogy with the formation routes of dimethyl ether (DME), which is characterized by a very similar molecular structure with the central S atom substituted by an O atom, Sanz-Novo et al. (2025) suggested as possible formation routes either the recombination reaction CH3(ice)+CH3 S(ice) → CH3 SCH3(ice) on the ice surface of interstellar dust grains or, alternatively, the following gas-phase reactions:

leading to protonated dimethyl sulfide, (CH3)2SH+ (hereinafter DMSH+), that must then be converted into neutral DMS. The lack of available experimental or quantum-chemistry investigations on these processes has prevented an assessment of their importance. However, interesting comparisons between S- and the O-related species were drawn, showing some consistency and aligning with the fact that sulfur species are significantly less abundant than their O counterparts. We recall that O and S are supposed to have similar chemical behavior since they belong to the same group of the periodic table. However, significant differences are possible (and already noted in some cases of interest; see, e.g., Berteloite et al. (2011) and Lin et al. (2000)).

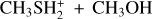

In this work, we used quantum chemistry and kinetics calculations to investigate several possible reactions that lead to the formation of DMS or its protonated version. Given that protonated methanol,  , is much more abundant than protonated methanethiol,

, is much more abundant than protonated methanethiol,  , we expect that the reaction

, we expect that the reaction

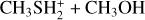

is more relevant than the ones suggested by Sanz-Novo et al. (2025). Therefore, we investigated reactions (1)–(3) to assess their role. Since reactions (1)–(3) produce DMSH+, we also characterized the proton transfer reaction to ammonia, following the original suggestion by Charnley et al. (1995) (see also Rodgers & Charnley 2001; Taquet et al. 2016) as an alternative way to ensure dissociative electron-ion recombination for the conversion of protonated species into their neutral counterpart

Finally, since DME can also be formed in the gas phase by the radiative association of the CH3 (methyl) and CH3 O (methoxy) radicals (as originally suggested by Balucani et al. 2015 and later demonstrated by Tennis et al. 2021), we also investigated the radiative association of CH3 and CH3 S (thiomethoxy) radicals,

using an approach similar to the one used by Tennis et al. (2021).

This article is organized as follows. In Section 2, the employed theoretical methods are described. In Sections 3 and 4, the results of electronic structure and kinetics calculations, respectively, are presented. The discussion and astrochemical implications are presented in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the principal conclusions of this work.

2 Theoretical methods

In this section, we first provide details on the methods employed to obtain the stationary points of the potential energy surfaces (PESs) of the studied reactions. The description of the kinetics calculations follows.

2.1 Electronic structure calculations

The proposed reactions were characterized by adopting the same computational strategy already used for other bimolecular reactions (see, e.g., Skouteris et al. 2015; Rosi et al. 2018; Giani et al. 2023; Rosi et al. 2019), including the related reactions

characterized in Skouteris et al. (2019). In the case of reaction (6), the calculated rate coefficients were compared with experimental data at room temperature and higher T (Skouteris et al. 2019). The excellent agreement indicates the accuracy of our methodology for systems of this type.

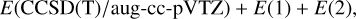

The GAUSSIAN09 (Frisch et al. 2009) and Molpro (Werner et al. 2020) software packages were used to investigate the PESs of reactions (1)–(5). All stationary points of the relevant PES were optimized at the DFT ω B97XD level of theory (Chai & Head-Gordon 2008) in conjunction with the minimally augmented Karlsruhe basis set ma-def2-TZVP (Zheng et al. 2011). Harmonic vibrational frequencies were computed, at the same level of theory, to determine the nature of each stationary point; that is, a minimum (reactants, reaction intermediates; and products) if all the frequencies are real, and a first-order saddle point (transition state) if there is one, and only one, imaginary frequency. When a saddle point was found, intrinsic-reaction-coordinate (IRC) calculations (Gonzalez & Schlegel 1989, 1990) were performed to assign each transition state to the respective reactant and product. After each geometry optimization at the DFT level, more accurate calculations were performed using the single- and double-electronic excitation coupled-cluster method with a perturbative description of triple excitations, CCSD(T) (Bartlett 1981; Olsen et al. 1996; Raghavachari et al. 1989), in conjunction with the correlation-consistent valence polarized basis set (Kendall et al. 1992; Woon & Dunning Jr 1993; Dunning Jr 1989), augmented with a tight d function for the sulfur atoms to correct for the core polarization effects (Dunning Jr et al. 2001) (aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z). The zero-point energy (ZPE) was used to correct all energy values. Finally, since some transition states for the systems under investigation are very close to the energy content of the reactants, we increased the level of theoretical calculations to obtain single-point energy values that are as accurate as possible. Using Molpro (Werner et al. 2012, 2020), we performed CCSD(T) calculations corrected with a density-fitted (DF)MP2 extrapolation to the complete basis set (CBS) and with corrections for core electron excitations. Namely, the energy values were computed according to

where

with E (DF-MP2/CBS) defined as

The E (DF-MP2/CBS) extrapolation was performed using Martin’s two-parameter scheme (Martin 1996), leading to an expected accuracy of about ± 5 kJ mol−1. These energies, labelled CBS despite also including core-valence correlation corrections, were used for the kinetic investigation described below. Given the uncertainty in the calculations, all reported energy values were rounded to the nearest integer. In a few cases, an additional decimal place is provided to indicate the relative ordering of structures with very similar energies.

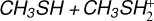

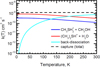

The calculated PESs for reactions (1)–(5) are shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, while the optimized structures of intermediates and transition states at the ω B97XD/ma-def2-TZVP level of theory are shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The energy values indicated inFigs. 1–5 are those computed at the CBS (black) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (red) level of theory.

|

Fig. 1 Potential energy surface for the reaction |

|

Fig. 2 Potential energy surface for the reaction |

|

Fig. 3 Potential energy surface for the reaction |

2.2 Kinetics calculations

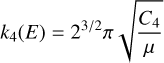

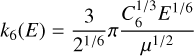

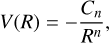

The initial bimolecular rate constant was computed using the capture theory formalism (see, e.g., Tsikritea et al. 2022) according to

for ion-molecule reactions (1)–(3) and

for neutral-neutral reactions. Cn (with n=4 and 6 for ionmolecule and neutral-neutral reactions, respectively) was obtained by considering the entrance potential described by the formula

in which R represents the distance between the two reactants (more specifically, the distance between the two atoms that approach each other to form the bond in the first intermediate). Cn is a coefficient obtained by fitting the long-range ab initio data (the values calculated for the reactions (2)–(5) are reported in Table B.1 of the appendix). Atomic units are used with 4πε0=1, where ε0 is the vacuum electric permittivity.

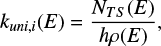

The Ramsperger-Rice-Kassel-Marcus (RRKM) theory (Gilbert & Smith 1990) was used to calculate the unimolecular reaction-rate coefficients, kuni, starting from the first reaction intermediates formed upon capture and as a function of the total energy, E, of each intermediate. We employed an in-house code widely used by us in previous studies and tested against experimental branching fractions (see, e.g., Leonori et al. 2013, 2009; Liang et al. 2023; Pannacci et al. 2023; Balucani et al. 2023). The energy-dependent rate coefficient for each specific channel, i, is given by

where NT S(E) is the sum of states of the transition state of each isomerization or dissociation step at the total energy, E, ρ(E) is the density of states of the intermediate undergoing the process at the total energy, E, and h is Planck’s constant. NT S(E) was obtained by integrating the relevant density of states up to the energy, E, assuming a rigid rotor/harmonic oscillator model. The density of states is symmetrized with respect to the number of identical configurations of the reactants and/or transition states. For the cases in which we were not able to locate a clear transition state in the exit channel, the corresponding microcanonical rate constant was obtained through a variational approach (Klippenstein 1992) in which kuni, i(E) is evaluated at various points along the reaction coordinate. The point that minimizes the rate constant was chosen in accordance with the variational theory. In cases where this approach could not be used due to problems with the electronic structure calculations, the transition state was assumed to be the products at infinite separation. This approximation has already been used by us and others and has been shown to provide reasonably accurate branching fractions when compared to experimental values (Pannacci et al. 2023; Liang et al. 2023; Vanuzzo et al. 2022). Having obtained unimolecular rate coefficients for all intermediate steps (at a specific energy), we made a steady-state assumption for all intermediates and, by resolving the master equation, derived energy-dependent rate constants for the overall reaction (from initial reactants to final products). Finally, we performed Boltzmann averaging of the energy-dependent rate constants to derive canonical rate constants (as a function of temperature).

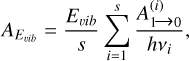

In the case of reaction (5), the radiative-association reaction rate coefficient was obtained by coupling the capture rate coefficient with the rate of spontaneous emission that we calculated following the approach suggested by Herbst (1982) and recently applied to the case of the related process CH3+CH3 O (Tennis et al. 2021). The spontaneous emission rate AEvib (in s−1) can be expressed as

where s is the number of vibrational frequencies and Evib is the total vibrational energy. Am → n is given by

where v is the transition frequency and I is the integrated intensity.

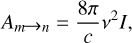

To facilitate their inclusion in astrochemical models, all the calculated rate constants were fit to the modified Arrhenius equation:

|

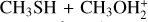

Fig. 4 Potential energy surface for the reaction (CH3)2SH++NH3. The indicated energy values are those computed at the CBS (black) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (red) levels of theory. |

|

Fig. 5 Potential energy surface for the reaction CH3+CH3 S. The indicated energy values are those computed at the CBS (black) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (red) levels of theory. |

|

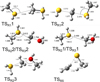

Fig. 6 ω B 97 XD/ma-def2-TZVP optimized geometries (Å and °) of the intermediates identified along the PESs of reactions (1)–(5). |

|

Fig. 7 ω B97XD/ma-def2-TZVP optimized geometries (Å and °) of the transition states identified along the PESs of reactions (1)–(5). |

3 Results: Potential energy surfaces

This section reports and describes the potential energy surfaces. All comments refer to energy values obtained using the CBS method, unless otherwise indicated.

3.1 Potential energy surface of the reaction

The reaction between methanethiol and protonated methanethiol starts with a barrierless formation of the adduct IR11 (located at −27 kJ mol−1 with respect to the energy content of the reactants, assumed as the zero value of the energy scale). IR11 is characterized by a new C−S interaction between the sulfur atom of CH3SH and the carbon atom of the protonated methanethiol. The C-S bond length is 3.376 Å (see Fig. 6), which is significantly larger than a typical σ bond length, thus suggesting that this could be considered an electrostatic interaction rather than a true chemical bond. IR11, through the transition state TSR11, which is almost degenerate in energy, can isomerize to the IR12 intermediate (located at −69 kJ mol−1) where the H+is equally shared by the two methanethiol moieties via electrostatic interaction. However, IR12 can only evolve back into protonated methanethiol and methanethiol, resulting in a null reaction being a protontransfer reaction between two identical molecules. Alternatively, IR11 can isomerize to IR13, where the C–S interaction becomes a true chemical bond (bond length 1.801 Å, see Fig. 6), while the terminal C−S bond becomes an electrostatic interaction (as can be noticed from the C−S bond length, which increases from the value of 1.812 Å in IR11 to a value of 3.518 Å in IR13). Once formed, IR13 easily evolves via the total detachment of the H2 S molecule into (CH3)2SH+. This channel is exothermic overall by −70 kJ mol−1 with respect to the reactants energy asymptote, but the transition state TSR12 connecting IR11 and IR13 is very high in energy, as it is located at +23 kJ mol−1 at our highest level of theory. The presence of such a high barrier for the channel leading to DMSH+and H2 S prevents this reaction from playing any role in the chemistry of molecular clouds, given the low temperatures typical of those regions.

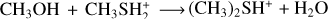

3.2 Potential energy surface of reaction

The interaction of methanol with protonated methanethiol starts with the barrierless formation of the electrostatic adduct IR21, in which the proton of  interacts with the oxygen atom of methanol. IR21 lies at −83 kJ mol−1 below the energy asymptote of the reactants of reaction (2), which is assumed as the zero value of the energy scale for this system. IR21 can only isomerize to IR22 by overcoming TSR11 (located at −4 kJ mol−1). In this step, the

interacts with the oxygen atom of methanol. IR21 lies at −83 kJ mol−1 below the energy asymptote of the reactants of reaction (2), which is assumed as the zero value of the energy scale for this system. IR21 can only isomerize to IR22 by overcoming TSR11 (located at −4 kJ mol−1). In this step, the  proton is being transferred to methanol, while the sulfur atom interacts with the carbon of the protonated methanol. IR22 can isomerize to IR23, and it then evolves into DMSH++H2 O. However, this isomerization takes place via a transition state, TSR22, whose energy (+2 kJ mol−1) is slightly above that of the reactants at the highest level of calculations employed here, while it is slightly below (−2 kJ mol−1) at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z level of theory. Unfortunately, this variation falls within the accuracy range of theoretical methods. Although small in absolute terms, this difference is crucial for determining the efficiency of this reaction, as a positive value of the TSR22 energy results in a very small rate coefficient at the temperatures of interest for molecular clouds because of the presence of an emerged barrier. We performed our kinetics calculations using the values calculated at both levels of theory employed to verify the effect. As we see, in both cases, back dissociation to reactants is significant, but the rate coefficients are larger by a factor of 102−103 with the CCSD(T)/aug-ccpV(Q+d) Z values compared to the CBS ones. The channel leading to the DMSH++H2 O channel is overall exothermic by 114 kJ mol−1.

proton is being transferred to methanol, while the sulfur atom interacts with the carbon of the protonated methanol. IR22 can isomerize to IR23, and it then evolves into DMSH++H2 O. However, this isomerization takes place via a transition state, TSR22, whose energy (+2 kJ mol−1) is slightly above that of the reactants at the highest level of calculations employed here, while it is slightly below (−2 kJ mol−1) at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z level of theory. Unfortunately, this variation falls within the accuracy range of theoretical methods. Although small in absolute terms, this difference is crucial for determining the efficiency of this reaction, as a positive value of the TSR22 energy results in a very small rate coefficient at the temperatures of interest for molecular clouds because of the presence of an emerged barrier. We performed our kinetics calculations using the values calculated at both levels of theory employed to verify the effect. As we see, in both cases, back dissociation to reactants is significant, but the rate coefficients are larger by a factor of 102−103 with the CCSD(T)/aug-ccpV(Q+d) Z values compared to the CBS ones. The channel leading to the DMSH++H2 O channel is overall exothermic by 114 kJ mol−1.

For this system, an additional channel could be considered; that is, the one leading to protonated dimethyl ether and H2 S. This channel is slightly endothermic (+7 kJ mol−1) at our best level of calculations, but we explored it for completeness. In this case, the initial interaction is established between the carbon of  and the oxygen atom of methanol and leads to the electrostatic intermediate IR24. To evolve toward the products, however, it must surmount a barrier of +42 kJ mol−1 (at the CBS level; +34 kJ mol at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z level of theory). Such a high barrier completely inhibits this reaction channel under the conditions of the ISM.

and the oxygen atom of methanol and leads to the electrostatic intermediate IR24. To evolve toward the products, however, it must surmount a barrier of +42 kJ mol−1 (at the CBS level; +34 kJ mol at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z level of theory). Such a high barrier completely inhibits this reaction channel under the conditions of the ISM.

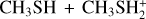

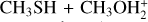

3.3 Potential energy surface of the reaction

The reaction between methanethiol and protonated methanol starts with the barrierless formation of the adduct IR31 (located at −33 kJ mol−1 with respect to the energy content of the reactants, assumed as the zero value of the energy scale). The structure of IR31 is the same as IR22, but in this case it is formed during the initial step of the reaction. A new C–S interaction between the sulfur atom of CH3SH and the carbon atom of the protonated methanol is formed. The C–S bond length is 3.201 Å, which is quite larger than the typical σ bond length, thus suggesting that this can also be considered an electrostatic interaction rather than a true chemical bond. IR31, through the transition state TSR32, which lies at −22 kJ mol−1 below the energy of the reactants, can isomerize to the IR33 intermediate (located at −168 kJ mol−1), where the C−S interaction becomes a true chemical bond (bond length 1.800 Å), while the terminal C−O bond becomes an electrostatic interaction, as we can notice from the C−O bond length (which increases from the value of 1.529 Å in IR31 to the value of 2.876 Å in IR33). Once formed, IR33 easily evolves via the total detachment of the water molecule into (CH3)2SH+. This channel is exothermic by −138 kJ mol−1 with respect to the reactants energy asymptote.

Alternatively, via TSR31 (located at −28 kJ mol−1), IR31 can also isomerize to IR32 (located at −107 kJ mol−1), another electrostatic complex where the proton of  is also interacting with the S atom of methanethiol. IR32 evolves towards

is also interacting with the S atom of methanethiol. IR32 evolves towards  in a proton transfer process, which is, overall, exothermic by 24 kJ mol−1. IR32 is the same intermediate of reaction (2) IR21, while IR33 coincides with IR23. Also, the connecting transition states TSR31 and TSR32 coincide with TSR21 and TSR22, respectively.

in a proton transfer process, which is, overall, exothermic by 24 kJ mol−1. IR32 is the same intermediate of reaction (2) IR21, while IR33 coincides with IR23. Also, the connecting transition states TSR31 and TSR32 coincide with TSR21 and TSR22, respectively.

Summarizing, reaction (3) is characterized by two competing channels that are both open in the low-T conditions of interstellar clouds: channel (3a) leads to the formation of DMSH+ +H2 O, while channel (3 b) is a proton-transfer channel leading to protonated methanethiol and methanol. We note here that the known proton affinity of CH3SH(773.4 kJ mol−1) is larger than that of CH3 OH(754.3 kJ mol−1) (Linstrom & Mallard 2025), in good agreement with our calculated enthalpy change. In conclusion, according to our calculations, each intermediate and transition state for the reaction channel (3 a) lies below the reactant’s energy asymptote, which makes it a feasible formation route of DMSH+in the low-temperature regions of the interstellar medium.

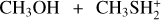

3.4 Potential energy surface of reaction (CH3)2SH++NH3

The PES for the reaction (CH3)2SH++NH3 is shown in Fig. 4, while the structure of the IR4 adduct is shown in Fig. 6. The reaction starts with the barrierless formation of the electrostatic adduct, which lies 101 kJ mol−1 below the reactants energy asymptote. IR4 then evolves via a proton-transfer mechanism into DMS and protonated ammonia. The process is exothermic by 19 kJ mol−1 with respect to the reactants energy asymptote, in line with the noted large proton affinity of CH3SH. The mild exothermicity guarantees a “gentle, ” non-dissociative proton-transfer mechanism.

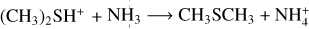

3.5 Potential energy surface of reaction CH3+CH3 S

The PES for the CH3+CH3 S radiative association is shown in Fig. 5. The reaction starts with the coupling of the unpaired electrons of CH3 and CH3 S and the formation of a new σ bond between the carbon atom of methyl and the sulfur atom of thiomethoxy. As expected, the addition is barrierless and leads directly to the formation of DMS, located at 305 kJ mol−1 below the reactant’s energy asymptote. In principle, DMS could evolve by losing an H atom or by forming thioformaldehyde and methane. However, the channel leading to CH3 SCH2+H is endothermic by 80 kJ mol−1 and, therefore, is not open. Instead, the channel leading to H2 CS and CH4 is strongly exothermic (−224 kJ mol−1), but DMS must overcome an energy barrier of 339 kJ mol−1 to dissociate into them. The relevant transition state (TSR5) is located at +34 kJ mol−1 above the energy of the reactants and, therefore, is not accessible under the low-T conditions typical of interstellar clouds. Consequently, given the absence of open two-product channels, radiative association can contribute to DMS formation.

An H-abstraction mechanism could also compete and lead directly to the H2 CS and CH4 products. Normally, processes of this kind are characterized by a small entrance barrier. This was the case for the related CH3 O+CH3 reaction (Sivaramakrishnan et al. 2011), but we were unable to locate one with our computational methods for the CH3+CH3 S system. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that this competitive process plays a role by reducing the reactive flux that experiences the deep potential well associated with DMS formation. Finally, a so-called roaming mechanism was seen to be active for the CH3 O+CH3 reaction. If it occurs, roaming would lead to the very exothermic H2 CS+CH4 channel (by analogy with the H2 CO+CH4 channel in the CH3 O+CH3 reaction (Sivaramakrishnan et al. 2011)). However, the roaming mechanism was observed to contribute only at high temperatures, which is not the case in the study under consideration here. Remarkably, experimental and theoretical investigation of DMS thermal decomposition only provided evidence of CH3+CH3 S formation (Shum & Benson 1985; Mousavipour et al. 2002), thus excluding the occurrence of the H2 CS+CH4 channel.

4 Results: Rate coefficients

4.1 Rate coefficients for the  reaction

reaction

Due to the presence of a significant reaction barrier, reaction (1) exhibits a negligible rate coefficient under the relevant conditions of the interstellar medium. This result confirms that exothermic ion-molecule reactions are not necessarily fast, as is often assumed in astrochemical models in the absence of specific information on the system under consideration.

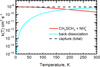

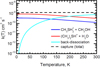

4.2 Rate coefficients for the  reaction

reaction

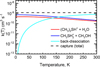

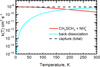

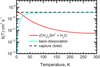

In this case, due to some issues with the electronic structure calculations, we were unable to perform geometry optimization of the structure along the entrance channel to derive the capture rate coefficients. For this reason, a rigid scan of the entrance channel was performed, consisting of a series of single-point energy evaluations at different distances between the two interacting fragments. According to our calculations, the favored initial step is the formation of the IR21 adduct rather than IR41. The resulting capture rate is significantly smaller that that for reactions (3) and (4) (see Figure 8). IR21 can undergo isomerization to IR22 or dissociate back to the reactants. TSR21 is quite high in energy (−4 kJ mol−1 at the CBS level, −6 kJ mol−1 at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z level), making back dissociation (i.e., the decomposition of IR21 back to the reactants) a competitive outcome. In addition, to evolve towards the bimolecular exit channel, IR22 must further isomerize to IR23, the electrostatic adduct preceding the separation of DMSH+and H2 O. The related transition state, TSR22 is quite high in energy, being located at +2 kJ mol−1 at our highest level of theory, while it is mildly submerged (−2 kJ mol−1) at the CCSD(T)/aug-ccpV(Q+d) Z level of theory. Unfortunately, kinetics calculations are very sensitive to this kind of difference in energy, as can be appreciated by comparing the rate coefficient as a function of the temperature when using the CBS values of energy for TSR22 and TSR23 (see Fig. 7) or the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (see Fig. A.1 of the appendix). This is an important reminder to use the most accurate electronic structure calculations possible in these special cases where the transition states are characterized by energy values very close to those of the reactants. For example, at 100 K, the two rate constants differ by three orders of magnitude. Given the greater accuracy of the CBS calculation level, we recommend using the rate constant derived in this way. The α and β coefficients were obtained by interpolating the calculated k(2) values. Different temperature ranges were used to achieve a better fit (see Table 1).

|

Fig. 8 Rate coefficients for reaction |

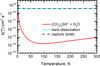

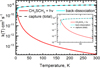

4.3 Rate coefficients for the  reaction

reaction

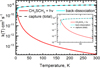

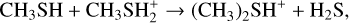

The initial step is the formation of the IR31 adduct in a barrierless process. We employed the approach described in Section 2.2 to obtain the capture rate coefficient. Then, we considered the possible evolution of IR31 via its isomerization to IR32 and IR33, as well as back dissociation to the reactants. We then applied the master equation approach to derive the partial rate coefficients for back dissociation: channels (3 a) and (3 b). The trend of the rate coefficients for each individual channel is shown in Fig. 9. At all temperatures, the rate coefficient of the competing channel (3 b) is slightly larger than the contribution of channel (3 a). With the increase in temperature, the contribution from back dissociation becomes significant, thus reducing both the values of k(3 a) and k(3 b), which, however, remain both significantly large over the entire range of temperatures explored. Also in this case, the accuracy of the electronic structure calculations is crucial for a proper description of the system. Indeed, even if the isomerization of IR31 to IR32 is always favored with respect to the isomerization to IR33 because TSR31 is lower than TSR32 at both levels of calculations (−28 vs. −22 kJ mol−1 at the CBS level and −29 vs. −25 kJ mol−1 at the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z level of theory), the increased energy gap for the CBS calculations has the effect of lowering the importance of channel (3 a). This can be appreciated by inspecting the unimolecular rate coefficients relative to IR31 → IR32 and IR31 → IR32 in Figure A.2.

Once accounting for the following steps, k(3 b) prevails over k(3 a) when using CBS values, while it is the opposite when using CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (see Fig. A.3). In both cases, the rate coefficients of (3 a) and (3 b) are comparable. This also signals an important reminder to use the most accurate electronic structure calculations possible when two or more competing channels have transition states with very close energies.

The rate constants for (3 a) and (3 b) were fit to Equation (16). Different temperature ranges were used to achieve a better fit. We chose to set γ=0 since both channels are barrierless. The resulting α and β coefficients for each temperature range are reported in Table 2.

|

Fig. 9 Rate coefficients for reaction |

Values of α and β coefficients for  reaction.

reaction.

Values of α and β coefficients for the reaction ( .

.

|

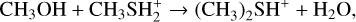

Fig. 10 Rate coefficients for proton-transfer reaction |

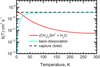

4.4 Rate coefficients for the (CH3)2SH++NH3 reaction

The calculated capture rate coefficient has the typical value for this kind of process (see Figure 10). However, since the reaction is not very exothermic (given the large proton affinity of DMS), at temperatures higher than 180 K back dissociation makes an important contribution, and the reaction coefficient decreases. The rate constant for reaction (5) was fit to equation (16). The resulting α and β coefficients for each temperature range are reported in Table 3.

Values of α and β coefficients for reaction CH3+CH3 S → CH3 SCH3.

|

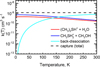

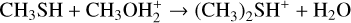

Fig. 11 Rate coefficients for CH3+CH3 S radiative-association reaction (red line) and back dissociation (cyan lines). The global capture rate coefficients are also shown (dashed black line). A close-up view of the range of temperatures between 5 and 30 K is shown in the inset figure. |

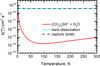

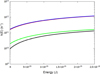

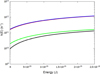

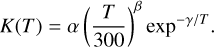

4.5 Rate coefficients for the CH3+CH3 S radiative association

The capture rate coefficients and their partitioning among radiative association and back dissociation are reported for the CH3+CH3 S system in Figure 11. Due to competition with back dissociation, the process of radiative association can only make a significant contribution at low temperatures (see the close-up for small temperature values in the inner panel of Fig. 11). A value of k on the order of 10−12 cm3 s−1 can be significant in rarefied media at very low temperatures.

The rate constant for reaction (5) was fit to equation (16). The reaction rate coefficients obtained from the fitting are reported in Table 4.

5 Discussion

5.1 Comparison of the reactions involving S- and O-bearing species

An interesting point to discuss concerns the comparison of the reactions studied in this work with analogous reactions involving oxygen species. The  reaction has been the focus of both theoretical and experimental studies, among which a recent theoretical study performed by us and employing the same methodology used here (Skouteris et al. 2019). When we compare the PES of the

reaction has been the focus of both theoretical and experimental studies, among which a recent theoretical study performed by us and employing the same methodology used here (Skouteris et al. 2019). When we compare the PES of the  system with that of reaction (1), we can identify both similarities and differences. The initial approach and the subsequent steps bear a close resemblance; however, some distinctions arise. The structure equivalent to IR11 (MIN1 in Skouteris et al. (2019)) is more stabilized with respect to the reactants (−47.3 vs. −27 kJ mol−1) since there is a stronger interaction between methanol and protonated methanol (notably, the distance between the O atom of methanol and the C atom of protonated methanol is 2.369 Å; this is to be compared with the distance between the S atom of methanethiol and the C atom of protonated methanethiol of 3.376 Å). This can be due to the fact that O atoms have a much higher electronegativity with respect to S atoms (3.44 vs. 2.58 according to the Pauling scale), and therefore they hold a larger partial negative charge in the neutral methanol reactant. In addition, the structure of TSR12 is more similar to IR13 than TS13 is to MIN3 in the PES by Skouteris et al. (2019), meaning that TSR12 appears to be a late transition state rather than an early one as TS13. Being a late transition state, TSR12 requires a greater modification of the structure of the initial intermediate IR11 if compared to the case of TS13 → MIN1, and thus a larger energy jump. The two combined effects may explain why TS13 is a submerged transition state at −23 kJ mol−1, while TSR12 is emerged by +23 kJ mol−1. A final remark concerns the similarity of the IR11 → TSR11 → IR12 pathway to the MIN1 → TS12 → MIN2 pathway in reaction (6): they both result in a proton transfer between two identical molecules.

system with that of reaction (1), we can identify both similarities and differences. The initial approach and the subsequent steps bear a close resemblance; however, some distinctions arise. The structure equivalent to IR11 (MIN1 in Skouteris et al. (2019)) is more stabilized with respect to the reactants (−47.3 vs. −27 kJ mol−1) since there is a stronger interaction between methanol and protonated methanol (notably, the distance between the O atom of methanol and the C atom of protonated methanol is 2.369 Å; this is to be compared with the distance between the S atom of methanethiol and the C atom of protonated methanethiol of 3.376 Å). This can be due to the fact that O atoms have a much higher electronegativity with respect to S atoms (3.44 vs. 2.58 according to the Pauling scale), and therefore they hold a larger partial negative charge in the neutral methanol reactant. In addition, the structure of TSR12 is more similar to IR13 than TS13 is to MIN3 in the PES by Skouteris et al. (2019), meaning that TSR12 appears to be a late transition state rather than an early one as TS13. Being a late transition state, TSR12 requires a greater modification of the structure of the initial intermediate IR11 if compared to the case of TS13 → MIN1, and thus a larger energy jump. The two combined effects may explain why TS13 is a submerged transition state at −23 kJ mol−1, while TSR12 is emerged by +23 kJ mol−1. A final remark concerns the similarity of the IR11 → TSR11 → IR12 pathway to the MIN1 → TS12 → MIN2 pathway in reaction (6): they both result in a proton transfer between two identical molecules.

When comparing reactions (2) and (3) with the  reaction, the most interesting aspects to note are the effects due to the loss of symmetry. In the case of reaction (2), the formation of protonated DME and H2 S is also possible, even though we demonstrate that this channel is not feasible under the conditions of molecular clouds. Concerning the case of reaction (3), while the symmetry of the

reaction, the most interesting aspects to note are the effects due to the loss of symmetry. In the case of reaction (2), the formation of protonated DME and H2 S is also possible, even though we demonstrate that this channel is not feasible under the conditions of molecular clouds. Concerning the case of reaction (3), while the symmetry of the  system has the effect of rendering the formation of MIN2 a dead end (as already stated above), in reaction (3) the equivalent species IR32 leads to the competing proton-transfer process. Additionally, due to the different characteristics of IR33 and the different energetics, we lack the equivalent pathways that proceed via other intermediates (MIN4 and MIN5 in Skouteris et al. (2019), the ultimate fate of which is the formation of protonated DME and water. Overall, the capture rate coefficients for reactions (3) and (6) are quite similar. In both cases, with the increase in temperature, back dissociation becomes significant. Concerning reaction (6), there is also a strong similarity with the equivalent (CH3)2 OH++NH3 reaction (Skouteris et al. 2019). Since the proton affinity of DMS is larger than that of DME (830.9 vs. 792 kJ mol−1) (Linstrom & Mallard 2025), the proton-transfer reaction with ammonia is less exothermic and back dissociation becomes important at temperatures above 200 K, slightly reducing the value of the rate coefficient. Instead, back dissociation was found to be negligible in the case of the reaction with protonated DME, whose rate coefficient was essentially independent of temperature.

system has the effect of rendering the formation of MIN2 a dead end (as already stated above), in reaction (3) the equivalent species IR32 leads to the competing proton-transfer process. Additionally, due to the different characteristics of IR33 and the different energetics, we lack the equivalent pathways that proceed via other intermediates (MIN4 and MIN5 in Skouteris et al. (2019), the ultimate fate of which is the formation of protonated DME and water. Overall, the capture rate coefficients for reactions (3) and (6) are quite similar. In both cases, with the increase in temperature, back dissociation becomes significant. Concerning reaction (6), there is also a strong similarity with the equivalent (CH3)2 OH++NH3 reaction (Skouteris et al. 2019). Since the proton affinity of DMS is larger than that of DME (830.9 vs. 792 kJ mol−1) (Linstrom & Mallard 2025), the proton-transfer reaction with ammonia is less exothermic and back dissociation becomes important at temperatures above 200 K, slightly reducing the value of the rate coefficient. Instead, back dissociation was found to be negligible in the case of the reaction with protonated DME, whose rate coefficient was essentially independent of temperature.

Finally, regarding the radiative association processes, we note significant differences in the CH3+CH3 O case compared to the CH3+CH3 S case. The canonical rate coefficient calculated by Tennis et al. (2021) is significantly larger than ours for temperatures over ∼ 10 K. Their phase-space coefficient is, instead, smaller than our values for very low temperatures, but it also remains in the 2 × 10−12 cm3 s−1 range at 300 K. Globally, our rate coefficient for the CH3+CH3 S radiative association is around two orders of magnitude smaller with respect to the case of CH3+CH3 O. To rationalize this difference, we note that the potential energy well associated with DMS is −234 kJ mol−1 with respect to CH3+CH3 S, whereas for DME it is – 351 kJ mol−1. This should increase the DME lifetime; however, the density of states is larger in the case of DMS, and therefore these two factors contrast each other. Furthermore, the spacing of the vibrational levels is larger in the case of DME, resulting in an increase in the Einstein coefficient for spontaneous emission, which varies as the square of the frequency. Using the data from Table 1 in Tennis et al. (2021), we calculated the Einstein coefficients for DME and compared them with our data for DMS. Around 300 K, they are larger by a factor of three. Therefore, our conclusion is that it is the different photon-emitting capability that makes the difference. In all cases, even though the radiative association has a much smaller rate coefficient, its contribution can play a significant role up to 100 K in very rarefied media, where few other processes can contribute.

5.2 Astrophysical implications: The case of molecular clouds and shocked regions

To date, the only detection of DMS in the interstellar medium has been toward the galactic-center molecular cloud G+0.693− 0.027 by Sanz-Novo et al. (2024). This object is known to be less depleted of S-species in the gas phase with respect to most known star-forming regions and molecular clouds (Sanz-Novo et al. 2024), where S is believed to be mostly locked in the dust grains (Fuente et al. 2023). The reduced depletion in G+0.693− 0.027 is probably associated with the erosion of the dust ices driven by shocks (Requena-Torres et al. 2006; Zeng et al. 2020). According to the estimates by Sanz-Novo et al. (2025), the ratios between the abundances of DME and DMS is ![$\frac{[D M E]}{[D M S]}=30 \pm 4$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa55216-25/aa55216-25-eq47.png) and that between CH3OH and CH3SH is

and that between CH3OH and CH3SH is ![$\frac{\left[{CH}_{3}{OH}\right]}{\left[{CH}_{3}{SH}\right]} \approx 31$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa55216-25/aa55216-25-eq48.png) . Considering a temperature of 100 K and a kinetically controlled regime in which the destruction routes of both DME and DMS have similar rate coefficients and k6 ≈k(3a), if reaction (3a) is the main DMS formation route and reaction (6) is the main DME formation route, and considering that the proton-transfer reactions with ammonia will have the same rate coefficient for protonated DMS and DME, we can write

. Considering a temperature of 100 K and a kinetically controlled regime in which the destruction routes of both DME and DMS have similar rate coefficients and k6 ≈k(3a), if reaction (3a) is the main DMS formation route and reaction (6) is the main DME formation route, and considering that the proton-transfer reactions with ammonia will have the same rate coefficient for protonated DMS and DME, we can write

which is nicely in agreement with the observed abundance ratios reported by Sanz-Novo et al. (2025). As a matter of fact, at 100 K the value of k6 is around 5 × 10−10 cm3 s−1, the value of k(3 a) is around 4 × 10−10 cm3 s−1, while the proton transfer to ammonia has a rate coefficient of c. 1 × 10−9 for the protonated DME and 7 × 10−10 for DMSH+. However, given the uncertainty of the detection and, especially, the missing information on the destruction routes, we can conclude that the agreement is quite satisfactory and that CH3OH and CH3SH can reasonably be the parent molecules of DME and DMS via their reactions with protonated methanol, followed by proton transfer to ammonia. We plan to run a complete astrochemical model to verify this very simplified estimate in a forthcoming article. The present results confirm that protonated methanol is an excellent methyl donor, as demonstrated by Taquet et al. (2016), in the formation of many interstellar complex organic molecules.

5.3 Astrophysical implications for other environments

Hänni et al. (2024) confirmed the detection of DMS in the comet 67/P Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which was initially reported with some ambiguity because of the presence of ethanethiol, an isomer of DMS (Altwegg et al. 2019). Molecules detected in cometary comae could be primary, that is, released directly by the nucleus of the comet; or secondary, that is, formed by chemical processes in the gaseous envelope formed by the sublimation of parent species. Hänni et al. (2024) did not discuss the profile of DMS with respect to the distance from the nucleus, and therefore we do not know to which class it belongs. Here, we comment that the ion  was clearly detected by ROSINA (Beth et al. 2020), as was methanethiol (Calmonte et al. 2016). Therefore, at least in principle, reaction (3) can contribute to DMS formation in the gaseous coma.

was clearly detected by ROSINA (Beth et al. 2020), as was methanethiol (Calmonte et al. 2016). Therefore, at least in principle, reaction (3) can contribute to DMS formation in the gaseous coma.

Concerning the DMS observed in the planet K2-18, we are not aware that ion-molecule reactions are considered in the photochemical models of the atmosphere of sub-Neptune exoplanets. Our work, therefore, can only contribute by pointing out that the CH3+CH3 S recombination is possible, either in high-pressure regions via termolecular collisions or collisional stabilization (or also by radiative association in the uppermost rarefied atmosphere). The presence of the thiomethoxy radical would require, as a precursor species, methanethiol, which is also considered a possible biosignature candidate, though less strong than DMS.

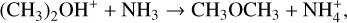

Interestingly, photochemical experiments have shown that DMS (as well as other sulfur-containing species) can be formed from a mixture of simple gaseous species, including H2 S and CH4 (Reed et al. 2024). To account for their results, the following sequence of reactions was proposed:

While reactions (18)–(21) have already been characterized and routinely used in the modelling of atmospheric chemistry, reaction (22) lacked a dedicated investigation. The PES that we derived here fully confirms the suggestion put forward by Reed et al. (2024): the deep well associated with DMS and the impossibility of evolving toward the product will cause dissociation back to the reactants, but with a lifetime of DMS ranging on the μ s timescale at room temperature. In an atmosphere with pressures in the mbar range, this can be sufficient to allow collisional stabilization by secondary collisions. Stabilizing three-body collisions are also possible.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we report new formation routes of DMS based on dedicated quantum and kinetics calculations. Our aim was to characterize the formation of DMS in shocked molecular clouds or star-forming regions. We identified three possible processes. Among them, we believe that the reaction between methanethiol and protonated methanol is a compelling candidate to explain the formation of DMS in the galactic-center molecular cloud G+0.693−0.027. The CH3+CH3 S radiative association is not a very efficient process, but it can make a contribution in cold clouds, provided that the thiomethoxy radical is available. This work does not directly address the possible formation routes of DMS in the atmospheres of exoplanets. However, it clearly indicates that there are efficient abiotic formation routes of this interesting species.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Italian MUR PRIN2020 (2020AFB3FX-Astrochemistry beyond the second period elements) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program from the European Research Council (ERC) (project ‘The Dawn of Organic Chemistry’ DOC, grant agreement no. 741002) for support. Support from the Italian Space Agency (Bando ASI Prot. no. DC-DSR-UVS-2022-231, Grant no. 2023-10-U. 0 MIGLIORA) is also acknowledged. MR acknowledges financial support under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.1, Call for tender No. 104 published on 2.2.2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), funded by the European Union-NextGenerationEU- Project Title 2022JC2Y93 ChemicalOrigins: linking the fossil composition of the Solar System with the chemistry of protoplanetary disks – CUP J53D23001600006 – Grant Assignment Decree No. 962 adopted on 30.06.2023 by the Italian Ministry of Ministry of University and Research (MUR). NB thanks the Campagne d’accueil de scientifiques étrangers – UGA et Grenoble INP-UGA – Année 2025 for supporting her stay at IPAG.

References

- Altwegg, K., Balsiger, H., & Fuselier, S. A., 2019, Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys., 57, 113 [Google Scholar]

- Balucani, N., Ceccarelli, C., & Taquet, V., 2015, MNRAS, 449, L16 [Google Scholar]

- Balucani, N., Caracciolo, A., Vanuzzo, G., et al. 2023, Faraday Discuss., 245, 327 [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, I., Hjorth, J., & Mihalopoulos, N., 2006, Chem. Rev., 106, 940 [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, R. J., 1981, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem., 32, 359 [Google Scholar]

- Bentley, R., & Chasteen, T. G., 2004, Chemosphere, 55, 291 [Google Scholar]

- Berteloite, C., Le Picard, S. D., Sims, I. R., et al. 2011, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 13, 8485 [Google Scholar]

- Beth, A., Altwegg, K., Balsiger, H., et al. 2020, A&A, 642, A27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Calmonte, U., Altwegg, K., Balsiger, H., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 462, S253 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Catling, D. C., Krissansen-Totton, J., Kiang, N. Y., et al. 2018, Astrobiology, 18, 709 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chai, J.-D., & Head-Gordon, M., 2008, J. Chem. Phys., 128 [Google Scholar]

- Charnley, S., Kress, M., Tielens, A., & Millar, T., 1995, ApJ, 448 [Google Scholar]

- Dunning Jr, T. H., 1989, J. Chem. Phys., 90, 1007 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DunningJr, T. H., Peterson, K. A., & Wilson, A. K., 2001, J. Chem. Phys., 114, 9244 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M., Trucks, G., Schlegel, H. B., et al. 2009, Inc. Wallingford CT, 121, 150 [Google Scholar]

- Fuente, A., Rivière-Marichalar, P., Beitia-Antero, L., et al. 2023, A&A, 670, A114 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Giani, L., Ceccarelli, C., Mancini, L., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 526, 4535 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, R. G., & Smith, S. C., 1990, Theory of Unimolecular and Recombination Reactions (Blackwell Scientific Publications) [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, C., & Schlegel, H. B., 1989, J. Chem. Phys., 90, 2154 [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, C., & Schlegel, H. B., 1990, J. Phys. Chem., 94, 5523 [Google Scholar]

- Hänni, N., Altwegg, K., Combi, M., et al. 2024, ApJ, 976, 74 [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, E., 1982, Chem. Phys., 65, 185 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, R. A., Dunning, T. H., & Harrison, R. J., 1992, J. Chem. Phys., 96, 6796 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Klippenstein, S. J., 1992, J. Chem. Phys., 96, 367 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leonori, F., Petrucci, R., Balucani, N., et al. 2009, J. Phys. Chem. A, 113, 15328 [Google Scholar]

- Leonori, F., Skouteris, D., Petrucci, R., et al. 2013, J. Chem. Phys., 138, 024311 [Google Scholar]

- Liang, P., de Aragão, E. V. F., Pannacci, G., et al. 2023, J. Phys. Chem. A, 127, 685 [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J. J., Shu, J., Lee, Y. T., & Yang, X., 2000, J. Chem. Phys., 113, 5287 [Google Scholar]

- Linstrom, P. J., & Mallard, W. G., 2025, NIST Chemistry WebBook, “Proton Affinity Evaluation” by Edward P. Hunter and Sharon G. Lias [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudhan, N., Piette, A. A., & Constantinou, S., 2021, ApJ, 918, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudhan, N., Sarkar, S., Constantinou, S., et al. 2023, ApJ, 956, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudhan, N., Constantinou, S., Holmberg, M., et al. 2025, New Constraints on DMS and DMDS in the Atmosphere of K2-18 b from JWST MIRI [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J. M., 1996, Chem. Phys. Lett., 259, 669 [Google Scholar]

- Mousavipour, S. H., Emad, L., & Fakhraee, S., 2002, J. Phys. Chem. A, 106, 2489 [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, J., Koch, H., Balkova, A., Bartlett, R. J., et al. 1996, J. Chem. Phys., 104, 8007 [Google Scholar]

- Pannacci, G., Mancini, L., Vanuzzo, G., et al. 2023, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 25, 20194 [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher, C. B., 2003, Astrobiology, 3, 471 [Google Scholar]

- Raghavachari, K., Trucks, G. W., Pople, J. A., & Head-Gordon, M., 1989, Chem. Phys. Lett., 157, 479 [Google Scholar]

- Reed, N. W., Shearer, R. L., McGlynn, S. E., et al. 2024, ApJ, 973, L38 [Google Scholar]

- Requena-Torres, M. A., Martín-Pintado, J., Rodríguez-Franco, A., et al. 2006, A&A, 455, 971 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, S., & Charnley, S., 2001, ApJ, 546, 324 [Google Scholar]

- Rosi, M., Mancini, L., Skouteris, D., et al. 2018, Chem. Phys. Lett., 695, 87 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rosi, M., Skouteris, D., Balucani, N., et al. 2019, in International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications (Springer), 306 [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Novo, M., Rivilla, V. M., Jiménez-Serra, I., et al. 2024, ApJ, 965, 149 [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Novo, M., Rivilla, V. M., Endres, C. P., et al. 2025, ApJ, 980, L37 [Google Scholar]

- Seager, S., Bains, W., & Hu, R., 2013, ApJ, 777, 95 [Google Scholar]

- Shum, L. G. S., & Benson, S. W., 1985, Int. J. Chem. Kinet., 17, 749 [Google Scholar]

- Sivaramakrishnan, R., Michael, J., Wagner, A., et al. 2011, Combust. Flame, 158, 618 [Google Scholar]

- Skouteris, D., Balucani, N., Faginas-Lago, N., Falcinelli, S., & Rosi, M., 2015, A&A, 584, A76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Skouteris, D., Balucani, N., Ceccarelli, C., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 482, 3567 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stefels, J., Steinke, M., Turner, S., Malin, G., & Belviso, S., 2007, Biogeochemistry, 83, 245 [Google Scholar]

- Taquet, V., Wirström, E. S., & Charnley, S. B., 2016, ApJ, 821, 46 [Google Scholar]

- Tennis, J., Loison, J.-C., & Herbst, E., 2021, ApJ, 922, 133 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tsikritea, A., Diprose, J. A., Softley, T. P., & Heazlewood, B. R., 2022, J. Chem. Phys., 157 [Google Scholar]

- Vanuzzo, G., Mancini, L., Pannacci, G., et al. 2022, ACS Earth Space Chem., 6, 2305 [Google Scholar]

- Werner, H.-J., Knowles, P. J., Knizia, G., Manby, F. R., & Schütz, M., 2012, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Computat. Mol. Sci., 2, 242 [Google Scholar]

- Werner, H.-J., Knowles, P. J., Manby, F. R., et al. 2020, J. Chem. Phys., 152 [Google Scholar]

- Woon, D. E., & DunningJr, T. H., 1993, J. Chem. Phys., 98, 1358 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S., Zhang, Q., Jiménez-Serra, I., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 497, 4896 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, J., Xu, X., & Truhlar, D. G., 2011, Theoret. Chem. Acc., 128, 295 [Google Scholar]

Appendix A Additional rate coefficients

The calculated rate coefficients for reactions (2) and (3) are different when using the CBS and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z energy values. While in the main text we have reported k(2) and k(3) derived by using the CBS energy values (see Figures 8 and 9), in this appendix are shown: a) the rate coefficients for reaction (2) when using the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z energy values; b) the unimolecular rate coefficients for the competing isomerization processes IR31 → IR32 and IR31 → IR33 in reaction (3) at both levels of calculations; c) the rate coefficients for reaction (3) when using the CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z energy values

|

Fig. A.1 Rate coefficients for the reaction |

|

Fig. A.2 Unimolecular rate coefficients relative to IR31 → IR32 with CBS (blue) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (red) energies, and to IR31 → IR33 with CBS (black) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (green) energies. |

Appendix B Cn coefficients

|

Fig. A.3 Rate coefficients for the reaction |

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Potential energy surface for the reaction |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Potential energy surface for the reaction |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Potential energy surface for the reaction |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Potential energy surface for the reaction (CH3)2SH++NH3. The indicated energy values are those computed at the CBS (black) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (red) levels of theory. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Potential energy surface for the reaction CH3+CH3 S. The indicated energy values are those computed at the CBS (black) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (red) levels of theory. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 ω B 97 XD/ma-def2-TZVP optimized geometries (Å and °) of the intermediates identified along the PESs of reactions (1)–(5). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 ω B97XD/ma-def2-TZVP optimized geometries (Å and °) of the transition states identified along the PESs of reactions (1)–(5). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Rate coefficients for reaction |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Rate coefficients for reaction |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10 Rate coefficients for proton-transfer reaction |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 11 Rate coefficients for CH3+CH3 S radiative-association reaction (red line) and back dissociation (cyan lines). The global capture rate coefficients are also shown (dashed black line). A close-up view of the range of temperatures between 5 and 30 K is shown in the inset figure. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.1 Rate coefficients for the reaction |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.2 Unimolecular rate coefficients relative to IR31 → IR32 with CBS (blue) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (red) energies, and to IR31 → IR33 with CBS (black) and CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pV(Q+d)Z (green) energies. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.3 Rate coefficients for the reaction |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$\begin{split}E(\text{DF-MP2/CBS}) & = E[\text{(DF-MP2)/aug-cc-pVQZ)}] \\ &\quad + 0.5772*[E(\text{DF-MP2/aug-cc-pVQZ}) \\ &\quad + - E(\text{DF-MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ})].\end{split}$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa55216-25/aa55216-25-eq14.png)

![$\begin{align*}& \frac{[D M E]}{[D M S]} \propto \frac{\text { rate }_{D M E^{\text {formation }}}}{\text { rate }_{D M S^{\text {formation }}}} \\& =\frac{\mathrm{k}_{6} \times\left[\mathrm{CH}_{3} \mathrm{OH}\right] \times\left[\mathrm{CH}_{3} \mathrm{OH}_{2}^{+}\right]}{\mathrm{k}_{(3 \mathrm{a})} \times\left[\mathrm{CH}_{3} \mathrm{SH}\right] \times\left[\mathrm{CH}_{3} \mathrm{OH}_{2}^{+}\right]}\\& =\frac{\mathrm{k}_{6} \times\left[\mathrm{CH}_{3} \mathrm{OH}\right]}{\mathrm{k}_{(3 \mathrm{a})} \times\left[\mathrm{CH}_{3} \mathrm{SH}\right]} \approx \frac{\left[\mathrm{CH}_{3} \mathrm{OH}\right]}{\left[\mathrm{CH}_{3} \mathrm{SH}\right]},\end{align*}$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa55216-25/aa55216-25-eq49.png)