| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A76 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Celestial mechanics and astrometry | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557345 | |

| Published online | 08 December 2025 | |

Lunar time ephemeris LTE440: Definitions, algorithm, and performance

1

Purple Mountain Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences,

Nanjing

210023,

China

2

School of Astronomy and Space Science, University of Science and Technology of China,

Hefei

230026,

China

★ Corresponding author: yixie@pmo.ac.cn

Received:

21

September

2025

Accepted:

20

October

2025

Context. Robotic and human activities in cislunar space are expected to rapidly increase in the future. Modeling, joint analysis, and sharing of time measurements made in the vicinity of the Moon may require calculating a lunar timescale and transforming it into other timescales.

Aims. For users, we present a ready-to-use software package of lunar time ephemeris LTE440 that can calculate the lunar coordinate time (TCL) and its relations with the barycentric coordinate time (TCB) and the barycentric dynamical time (TDB).

Methods. According to the International Astronomical Union Resolutions on relativistic timescales, we numerically calculated the relativistic time-dilation integral in the TCL-TCB or TCL-TDB transformation with the JPL ephemeris DE440 including the gravitational contributions from the Sun, all planets, the main belt asteroids, and the Kuiper belt objects.

Results. At a conservative estimate, LTE440 has an accuracy better than 0.15 ns before 2050 and a numerical precision at the level of 1 ps throughout its entire time span. The secular drifts between the coordinate times in LTE440 are respectively estimated as ⟨d TCL/d TCB⟩ = 1−1.482 536 216 7 × 10−8 and ⟨d TCL/d TDB⟩ = 1 + 6.798 355 24 × 10−10. Its most significant periodic variations are an annual term with an amplitude of 1.65 ms and a monthly term with an amplitude of 126 µs.

Conclusions. LTE440 might satisfy most current needs and the data files are publicly available.

Key words: ephemerides / time

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

The relativistic time-dilation integral is an indispensable ingredient in the transformation between timescales defined in two distinct reference systems in the Solar System. One perfect example is the time ephemeris of the Earth, traditionally called “time ephemeris” for short, which represents the integral in the transformation between the geocentric coordinate time (TCG) or terrestrial time (TT) and the barycentric coordinate time (TCB) or the barycentric dynamical time (TDB), according to the International Astronomical Union (IAU) Resolutions on relativistic reference systems and timescales (Soffel et al. 2003; IAU 2006).

The time ephemeris has been an essential part of the current framework for the reference systems of the relativistic space-time (e.g., Brumberg et al. 1996; Soffel et al. 2003) and has been widely used in Earth-based time-related measurements, such as the precise modeling of astrometry (e.g., Klioner 2003; Lindegren & Dravins 2003), spacecraft tracking (e.g., Dirkx et al. 2016), pulsar timing (e.g., Hobbs et al. 2006; Edwards et al. 2006), and geodesy (Müller et al. 2008; Sánchez et al. 2016). The time ephemerides can be divided into two types: analytical and numerical. Dating back to the 1960s, the analytical ones climax with Fairhead & Bretagnon (1990), and all of them are based on analytical planetary and lunar ephemerides. The numerical time ephemeris evaluates the relativistic time-dilation integral numerically with the quantities provided by a numerical planetary and lunar ephemeris. In its earlier stage, the pioneering studies of Fukushima (1995) and Irwin & Fukushima (1999) provided time ephemerides with more sophisticated methods and higher accuracy. Nowadays, all the widely used planetary and lunar ephemerides, such as DE440 (Park et al. 2021), INPOP21a (Fienga et al. 2021), and EPM2021 (Pitjeva et al. 2022), provide evaluated TT−TDB in their products, which can be directly obtained by a user without any further calculation; in addition, INPOP21a also gives TCG − TCB.

However, with the expected increase in robotic and human activities in the cislunar space in the future, new demands might emerge. A lunar time ephemeris, which characterizes the relativistic time-dilation in the transformation between the lunar coordinate time (TCL) (IAU 2024a) and TCB or TDB, would be useful for conveniently modeling, jointly analyzing, and sharing time measurements made in the vicinity of the Moon. Such an ephemeris could be employed in scenarios that demand high accuracy and ease of use, including (but not limited to) tracing the proper time of a Moon-based clock back to the Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) and conducting the very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) with telescopes separated in the vicinity of the Earth and Moon.

Missions on and around the Moon in the future might require a practical lunar reference time (LRT) (IAU 2024b), since TCL – defined as the time coordinate for the lunar celestial reference system (LCRS) (IAU 2024a) – is not given by any real clock. Although international organizations and countries have not yet reached an agreement on the definition of an LRT scale, there is consensus that the relationship between LRT and UTC must be clearly established. Ensuring this traceability requires the development of a lunar time ephemeris to bridge the gap between these timescales. If the uncertainty of LRT UTC is within 10 ns in a day, it translates to a relative error and−corresponding lunar time ephemeris derivative error of 10−13. The systematic errors of the lunar time ephemeris and its derivative should be ideally kept at the level of 0.1 ns and 10−15, at least 2 orders of magnitude smaller than proposed demands, according to the consideration of Irwin & Fukushima (1999).

By taking advantage of the Moon’s low gravity, absence of atmosphere, deep natural cooling, low magnetic field, and interference-free radio environment (Burns 1985; Gurvits 1998), Earth-Moon VLBI with Earth- and Moon-based radio telescopes might significantly improve our understanding of the Moon’s orbital and rotational motion and enhance the precision of astrometry with its longer baselines and more sufficient uv-coverage (Kurdubov et al. 2019). With the expectation that Earth-Moon VLBI would achieve performance at least as good as ground-based VLBI, it requires time tags of the recorded signals on the Moon with uncertainties less than 1 µs and Moon-based clocks with stability better than 10−14 at 50 min, consistent with the requirements of ground-based VLBI (Nothnagel et al. 2018). Therefore, the systematic errors of the lunar time ephemeris and its derivative must be controlled at the level of 10 ns and 10−16, 2 orders of magnitude better than these requirements. Targeted at the direct imaging of supermassive black holes and their photon rings (Fish et al. 2020; Roelofs et al. 2021), future space-borne submillimeter VLBI in the cislunar space might raise even more challenges to the technological and theoretical aspects of time-related measurements (Gurvits et al. 2022; Hudson et al. 2023).

Very recently, Ashby & Patla (2024), Kopeikin & Kaplan (2024), and Turyshev et al. (2025) estimated the rate of an ideal clock on the Moon’s selenoid with respect to the one on the Earth’s geoid. Furthermore, Kopeikin & Kaplan (2024) and Turyshev et al. (2025) also constructed analytical formulae to handle the relativistic time-dilation integral associated with TCL by adopting different approximations and cutoffs for the lunar motion, which could be regarded as nascent analytic lunar time ephemerides. Motivated by potential needs and inspired by these pioneering studies, we extend these analytical results by making a numerical lunar time ephemeris following the methodology of foundational studies by Fukushima (1995) and Irwin & Fukushima (1999).

In this work, we present the lunar time ephemeris package LTE4401, which contains the numerically evaluated relativistic time-dilation integral between TCL and TCB or TDB and also provides functions to calculate TCL − TCB, TCL − TDB, and TCL for a given TDB moment. We define the relativistic time-dilation integral of the lunar time ephemeris in Sect. 2. We explain the algorithms for calculating the integral based on DE440 and making the product of LTE440 in Sect. 3. By comparing LTE440 with LTE430 and LTE441, two auxiliary lunar time ephemeris packages based on DE430 and DE441, we analyze their characteristics and differences, assess their performance, and correct the linear drift of ⟨dTCL/dTCB⟩ of LTE440 through LTE441 in Sect. 4. We conclude the paper in Sect. 5.

2 Definitions

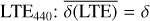

According to IAU 2024 Resolution II (IAU 2024a), LCRS and TCL can be constructed with the same techniques used to construct the Geocentric Celestial Reference System (GCRS) and TCG. The transformation between TCL and TCB is analogous to the transformation between TCG and TCB given by IAU 2000 Resolution B1.5 (Soffel et al. 2003), with the Earth-related quantities replaced by the Moon-related quantities. Therefore, the relation between TCL and TCB can be expressed as

(1)

where “

(1)

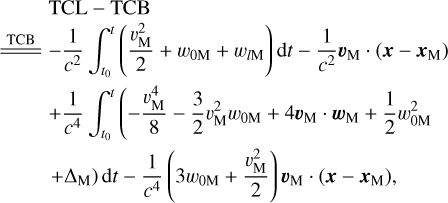

where “ ” means that all quantities on its right-hand side are TCB-compatible, t denotes TCB, t0=1977 January 1, 0h0m32.184s is the common value of TT, TCG, TCB, and TCL set on 1977 January 1, 0h0m0s International Atomic Time (TAI) (IAU 2024a). x is the barycentric position vectors of the point where the transformation between TCL and TCB occurs, while xM and vM are the barycentric position and velocity vectors of the Moon. The potential w0M describes the gravitational potential of external bodies at the center of the Moon in the point-mass approximation, and it is defined as

” means that all quantities on its right-hand side are TCB-compatible, t denotes TCB, t0=1977 January 1, 0h0m32.184s is the common value of TT, TCG, TCB, and TCL set on 1977 January 1, 0h0m0s International Atomic Time (TAI) (IAU 2024a). x is the barycentric position vectors of the point where the transformation between TCL and TCB occurs, while xM and vM are the barycentric position and velocity vectors of the Moon. The potential w0M describes the gravitational potential of external bodies at the center of the Moon in the point-mass approximation, and it is defined as

(2)

where rMA = |rMA|, rMA = xM − xA, and the summation runs over all the Solar System bodies A except the Moon (M). The potential wlM represents the nonspherical gravitational potential of the external bodies. The vector potential wM can be expressed as

(2)

where rMA = |rMA|, rMA = xM − xA, and the summation runs over all the Solar System bodies A except the Moon (M). The potential wlM represents the nonspherical gravitational potential of the external bodies. The vector potential wM can be expressed as

![${{\bf{w}}_{\rm{M}}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{{\rm{A}} \ne {\rm{M}}} G\left[ {{{{M_{\rm{A}}}{{\bf{v}}_{\rm{A}}}} \over {{r_{{\rm{MA}}}}}} - {{{{\bf{r}}_{{\rm{MA}}}} \times {{\bf{S}}_{\rm{A}}}} \over {2r_{{\rm{MA}}}^3}}} \right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57345-25/aa57345-25-eq4.png) (3)

where SA is the total angular momentum of body A. The ∆M term contains nonlinear couplings of w0M and wM and other higher-order contributions at

(3)

where SA is the total angular momentum of body A. The ∆M term contains nonlinear couplings of w0M and wM and other higher-order contributions at  ; it is defined as

; it is defined as

![$\matrix{{{\Delta _{\rm{M}}} = \mathop \sum \limits_{{\rm{A}} \ne {\rm{M}}} \{ {{G{M_{\rm{A}}}} \over {{r_{{\rm{MA}}}}}}[\mathop \sum \limits_{{\rm{B}} \ne {\rm{A}}} {{G{M_{\rm{B}}}} \over {\left| {{x_{\rm{B}}} - {x_{\rm{A}}}} \right|}} - 2v_{\rm{A}}^2 + {{{{({{\bf{r}}_{{\rm{MA}}}} \cdot {{\bf{v}}_{\rm{A}}})}^2}} \over {2r_{{\rm{MA}}}^2}}} \hfill \cr {{{{{\bf{r}}_{{\rm{MA}}}} \cdot {{\bf{a}}_{\rm{A}}}} \over 2}] + {{2G{{\bf{v}}_{\rm{A}}} \cdot ({r_{{\rm{MA}}}} \times {{\bf{S}}_{\rm{A}}})} \over {r_{{\rm{MA}}}^3}}\} ,} \hfill \cr }$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57345-25/aa57345-25-eq6.png) (4)

where aA is the barycentric acceleration vector of the body A.

(4)

where aA is the barycentric acceleration vector of the body A.

In order to evaluate the relation of TCL−TCB (1), one inevitably needs an ephemeris to know the positions and velocities of the Solar System bodies up to sufficient accuracy. Given the fact that all modern numerical ephemerides adopt TDB as their main timescale, it is more convenient for calculation and practical use to rewrite TCL−TCB as TCL − TDB by considering the linear relation between TCB and TDB (IAU 2006):

(5)

so that we find

(5)

so that we find

![$\matrix{ {} \hfill & {{\rm{TCL - TDB}}} \hfill \cr {\underline{\underline {{\rm{TDB}}}} } \hfill & {{{{L_B}} \over {1 - {L_B}}}\left( {{\rm{TDB}} - {t_0}} \right) - {1 \over {1 - {L_B}}}{\rm{TD}}{{\rm{B}}_0}} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & { - {1 \over {1 - {L_B}}}\left[ {{1 \over {{c^2}}}\int_{{\rm{TD}}{{\rm{B}}_{0 + }}{t_0}}^{{\rm{TDB}}} {\left( {{{v_{\rm{M}}^2} \over 2} + {w_{0{\rm{M}}}} + {w_{l{\rm{M}}}}} \right){\rm{dTDB}}} } \right.} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & { + {1 \over {{c^2}}}{v_{\rm{M}}} \cdot \left( {x - {x_{\rm{M}}}} \right) - {1 \over {{c^4}}}\left( { - {{v_{\rm{M}}^4} \over 8} - {3 \over 2}v_{\rm{M}}^2{w_{0{\rm{M}}}}} \right.} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {\left. { + 4{v_{\rm{M}}} \cdot {w_{\rm{M}}} + {1 \over 2}w_{0{\rm{M}}}^2 + {\Delta _{\rm{M}}}} \right){\rm{dTDB}}} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {\left. { + {1 \over {{c^4}}}\left( {3{w_{0{\rm{M}}}} + {{v_{\rm{M}}^2} \over 2}} \right){v_{\rm{M}}} \cdot \left( {x - {x_{\rm{M}}}} \right)} \right],} \hfill \cr }$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57345-25/aa57345-25-eq8.png) (6)

where “

(6)

where “ ” means that all quantities on its right-hand side are TDB-compatible, and LB = 1.550519768 × 10−8 and TDB0 = −6.55 × 10−5 s are defining constants. If one can directly combine TCL−TDB and TT − TDB, one can easily find TCL − TT. Since TT−TDB has been precisely provided by the ephemerides DE440, INPOP21a, and EPM2021, we believe that a ready-to-use product of TCL−TDB may help trace the Moon-based timescales back to the Earth-based ones.

” means that all quantities on its right-hand side are TDB-compatible, and LB = 1.550519768 × 10−8 and TDB0 = −6.55 × 10−5 s are defining constants. If one can directly combine TCL−TDB and TT − TDB, one can easily find TCL − TT. Since TT−TDB has been precisely provided by the ephemerides DE440, INPOP21a, and EPM2021, we believe that a ready-to-use product of TCL−TDB may help trace the Moon-based timescales back to the Earth-based ones.

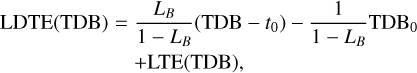

Following Fukushima (1995), we denote the time-dilation integral in Eq. (1) as the lunar time ephemeris (LTE). Considering TDB as the timescale used by modern planetary ephemerides and following the note on the computation in IAU 2000 Resolution B1.5 (Soffel et al. 2003), we write it in terms of TDB-compatible quantities as

![$\matrix{{{\rm{LTE(TDB)}}} \hfill \cr { = - {1 \over {1 + {L_B}}}[{1 \over {{c^2}}}\mathop \smallint \limits_{{\rm{TD}}{{\rm{B}}_0} + {t_0}}^{{\rm{TDB}}} \left( {{{v_{\rm{M}}^2} \over 2} + {w_{0{\rm{M}}}} + {w_{l{\rm{M}}}}} \right){\rm{dTDB}}} \hfill \cr { - {1 \over {{c^4}}}\mathop \smallint \limits_{{\rm{TD}}{{\rm{B}}_0} + {t_0}}^{{\rm{TDB}}} ( - {{v_{\rm{M}}^4} \over 2} - {3 \over 2}v_{\rm{M}}^2{w_{0{\rm{M}}}} + 4{{\bf{v}}_{\rm{M}}} \cdot {{\bf{w}}_{\rm{M}}}} \hfill \cr { + {1 \over 2}w_{0{\rm{M}}}^2 + {\Delta _{\rm{M}}}){\rm{dTDB}}],} \hfill \cr }$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57345-25/aa57345-25-eq10.png) (7)

which are precisely the integrals in Eq. (6). With its help, we can rewrite the transform of TCL−TCB as

(7)

which are precisely the integrals in Eq. (6). With its help, we can rewrite the transform of TCL−TCB as

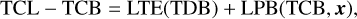

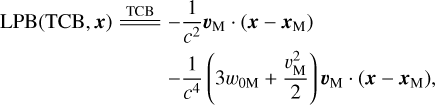

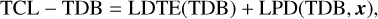

(8)

where LPB(TCB, x) depends on TCB and the user’s TCB-compatible position, expressed as

(8)

where LPB(TCB, x) depends on TCB and the user’s TCB-compatible position, expressed as

(9)

and similarly, rewrite the form of TCL−TDB as

(9)

and similarly, rewrite the form of TCL−TDB as

(10)

where

(10)

where

(11)

and LPD(TDB, x) depends on TDB and the user’s TDB-compatible position as

(11)

and LPD(TDB, x) depends on TDB and the user’s TDB-compatible position as

![$\matrix{ {{\rm{LPD(TDB,}}{\bf{x}}{\rm{)}}\mathop = \limits^{{\rm{TDB}}} {1 \over {1 - {L_B}}}[ - {1 \over {{c^2}}}{{\bf{v}}_{\rm{M}}} \cdot ({\bf{x}} - {{\bf{x}}_{\rm{M}}})} \hfill \cr { - {1 \over {{c^4}}}\left( {3{w_{0{\rm{M}}}} + {{v_{\rm{M}}^2} \over 2}} \right){{\bf{v}}_{\rm{M}}} \cdot ({\bf{x}} - {{\bf{x}}_{\rm{M}}})].} \hfill \cr }$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57345-25/aa57345-25-eq15.png) (12)

(12)

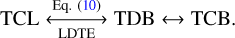

We can see that the introduction of TDB in the TCL − TCB transformation might simplify the computation of its integral in Eq. (1) and facilitate the creation of a ready-to-use product of lunar time ephemeris; however, the drawback is that users must handle three time coordinates that appear in Eq. (8). The TCL−TDB transformation bridged by LDTE(TDB) in Eq. (10) avoids such a dilemma and enables users to easily and clearly calculate TCL for a given TDB moment with an available product of LDTE(TDB), and vice versa. Therefore, in the following parts of this work, we adopt the chain of transformations as

(13)

(13)

Using the JPL ephemeris DE440 (Park et al. 2021), we numerically computed the right-hand side of Eq. (7) and exported data files in the SPICE format2. For users, we also provide software functions to calculate LTE(TDB) in TCL − TDB and LDTE(TDB) in TCL−TCB at a given TDB epoch, respectively. We call the package of these data files and functions as LTE440. To enhance understanding, we made two auxiliary lunar time ephemeris packages, LTE430 and LTE441, based on JPL ephemerides DE430 (Folkner et al. 2014) and DE441 (Park et al. 2021), respectively, for comparisons and uncertainty assessments. For convenience, we denote the mathematical function LTE(TDB) (7) in LTE430, LTE440, and LTE441 as LTE430, LTE440, and LTE441 for short, respectively.

3 Algorithm

We evaluated the integral in Eq. (7) using a tenth-order Romberg scheme (Press et al. 1992) with half-day integration intervals. The integrand was computed using position and velocity data of the Sun, planets, and small objects provided by JPL ephemerides. Since the integrand consists of a constant value plus periodic terms, the resulting lunar time ephemeris is expected to exhibit a more significant secular drift along with indistinct periodic terms over a long time span. Since no mature analytic series of lunar time ephemeris is currently available, we were unable to use the hybrid method of Irwin & Fukushima (1999) to separate the secular drift and periodic variations for maintaining the accuracy of the numerical evaluation of Eq. (7). In order to reveal these periodic terms in the lunar time ephemeris more clearly, we adopted a method that combines the approaches of Fukushima (1995) and Irwin & Fukushima (1999). First, we subtracted a roughly estimated constant from the integrand of Eq. (7) in the initial evaluation (Irwin & Fukushima 1999), which can be regarded as an approximated secular drift rate of the lunar time ephemeris. Then, we iteratively found the secular drift rate of the resulting curve by fitting it with a linear function and reevaluated the integration after removing this rate from the integrand until this rate converged (Fukushima 1995). Finally, we subtracted this converged rate from the integrand, redid the integration numerically, and combined the evaluation with the secular drift as our product. We suppose that this procedure can more clearly separate the secular drift and the periodic terms in the lunar time ephemeris based solely on the numerical computation. We also discuss a possible way to calibrate such a drift rate by using a longer time-span numerical ephemeris in Sect. 5.

We used three versions of JPL ephemerides DE430, DE440, and DE441 to produce the lunar time ephemerides. Table A.1 summarizes and compares the characteristics of these planetary ephemerides. As pointed out by Park et al. (2021), several updates have been made in DE440 and DE441 compared to DE430, including 30 Kuiper belt objects and a ring, solar radiation pressure on the Earth and the Moon, and the Lense–Thirring effect from the Sun’s angular momentum. For the resulting lunar time ephemerides, the gravitational contribution of these Kuiper belt objects and the motion of the Moon could be the main factors differentiating LTE430 from LTE440 or LTE441.

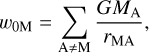

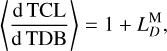

We estimated the error of our integration scheme by comparing the resulting lunar time ephemeris computed with integration intervals of half-day and one-day, respectively. We find that their difference is on the order of 10 fs, which is negligible for the purpose of this work. We further assessed the accuracy of our numerical method by reproducing TT – TDB at the geocenter using the planetary data from DE440 and comparing our result with the one inherently provided by DE440. As shown in Fig. 1, we find that the difference between our reproduction and that of DE440 is less than 1 ps over the entire time span, demonstrating that our numerical scheme is adequate for producing a precise lunar time ephemeris comparable with the time ephemeris provided by DE440.

The values of the integral (7) with its secular drift removed are fitted with thirteenth-degree Chebyshev polynomials on four-day granules using the method described by Newhall (1989). The coefficients of these Chebyshev polynomials are exported into a binary SPK file conforming to the SPICE format. The coefficients of the secular drift are stored in a text PCK file. These files for LTE440 are publicly available; see Lu et al. (2025) for more details on their usage.

|

Fig. 1 Differences between our reproduced version of TT − TDB at the geocenter using the planetary data of DE440 and the inherent version of DE440. Top panel: difference between the derivatives δ[d(TT − TDB)/dTDB] = [d(TT − TDB)/dTDB]this [d(TT − TDB)/dTDB]DE440. Bottom panel: −difference between the Earth time ephemerides δ(TT − TDB) = (TT − TDB)this − (TT − TDB)DE440. |

4 Performance

In this section, we present some detailed characteristics of LTE440, including its secular drift and periodic variations. We also compare LTE430 and LTE440, and attempt to correct the secular drift of LTE440 by using LTE441 with a longer time span.

4.1 Characteristics

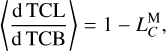

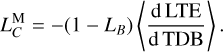

It is well known that there are secular drifts of TCG with respect to TCB and TDB (Seidelmann & Fukushima 1992). The same is true for TCL. Following IAU Resolution 2000 (Soffel et al. 2003), we introduce  and

and  to describe the secular drifts of TCL with respect to TCB and TDB, respectively, as

to describe the secular drifts of TCL with respect to TCB and TDB, respectively, as

(14)

and

(14)

and

(15)

where ⟨ ⟩ refers to a sufficiently long time average used to remove its periodic variations.

(15)

where ⟨ ⟩ refers to a sufficiently long time average used to remove its periodic variations.  and

and  satisfy the following relation:

satisfy the following relation:

(16)

(16)

In fact, according to Eqs. (5) and (8), at the selenocenter x = xM, we have

(17)

(17)

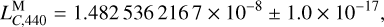

Based on LTE440, we find that

(18)

and

(18)

and

(19)

(19)

Our numerical estimation of  is consistent with the analytic ones given by Kopeikin & Kaplan (2024) and Turyshev et al. (2025) (see Table 1 for a comparison).

is consistent with the analytic ones given by Kopeikin & Kaplan (2024) and Turyshev et al. (2025) (see Table 1 for a comparison).

We also estimated the contributions to  from different sources in LTE440, as shown in Table 2. We find that the square of lunar velocity and the gravitational potential of the Sun at the Moon play the most significant roles in

from different sources in LTE440, as shown in Table 2. We find that the square of lunar velocity and the gravitational potential of the Sun at the Moon play the most significant roles in  , with the contribution reaching about 5 × 10−9 and 1 × 10−8, respectively. These contributions are at least two and three orders of magnitude greater than those of the Earth and the Jupiter system, which are the third and fourth contributors in

, with the contribution reaching about 5 × 10−9 and 1 × 10−8, respectively. These contributions are at least two and three orders of magnitude greater than those of the Earth and the Jupiter system, which are the third and fourth contributors in  . Despite their remoteness, the objects and the ring in the Kuiper belt, which are new gravitational ingredients for DE440, contribute about 2 × 10−17 in

. Despite their remoteness, the objects and the ring in the Kuiper belt, which are new gravitational ingredients for DE440, contribute about 2 × 10−17 in  : this is more than three times greater than the overall contribution of closer main belt asteroids, due to the much higher total mass of the Kuiper belt objects and the ring. While we took the dynamical form factors, J2, of the Earth and the Sun into account for completeness, the former rose barely to about 1 × 10−18, and the latter was even smaller by two orders of magnitude. The total contribution of all gravitational bodies at the post-Newtonian order

: this is more than three times greater than the overall contribution of closer main belt asteroids, due to the much higher total mass of the Kuiper belt objects and the ring. While we took the dynamical form factors, J2, of the Earth and the Sun into account for completeness, the former rose barely to about 1 × 10−18, and the latter was even smaller by two orders of magnitude. The total contribution of all gravitational bodies at the post-Newtonian order  is about 1 × 10−16, mainly arising from the Moon’s velocity and the Sun’s potential.

is about 1 × 10−16, mainly arising from the Moon’s velocity and the Sun’s potential.

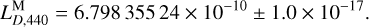

Using Fourier transform on LTE440 after removing its linear trend, we find that there are 13 periodic terms with amplitudes larger than 1 µs. The amplitudes Ai, periods Ti, and phases ϕi of these terms  are listed in Table 3. The arguments of each term are derived from their periods, which indicate the contributing sources of each term. The first periodic variation with the largest amplitude of 1.6 ms and a period of about 365.26 day is due to the orbital motion of the Earth-Moon barycenter around the Sun. The second periodic variation with an amplitude of 126 µs and a period of 29.53 days comes from the orbital motion of the Moon around the Earth. The sources of the third and fourth terms are the motion of the Moon relative to Jupiter and around the Sun, respectively. All the other variations with amplitudes below 10 µs are associated with the motion of the Moon, Venus, Earth, Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. We note that the accuracy of these periodic terms is limited by the Fourier transform, and the figures in Table 3 consist of preliminary results. In following studies, we might use more sophisticated approaches, such as that of Harada & Fukushima (2003), to perform harmonic analysis on LTE440.

are listed in Table 3. The arguments of each term are derived from their periods, which indicate the contributing sources of each term. The first periodic variation with the largest amplitude of 1.6 ms and a period of about 365.26 day is due to the orbital motion of the Earth-Moon barycenter around the Sun. The second periodic variation with an amplitude of 126 µs and a period of 29.53 days comes from the orbital motion of the Moon around the Earth. The sources of the third and fourth terms are the motion of the Moon relative to Jupiter and around the Sun, respectively. All the other variations with amplitudes below 10 µs are associated with the motion of the Moon, Venus, Earth, Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. We note that the accuracy of these periodic terms is limited by the Fourier transform, and the figures in Table 3 consist of preliminary results. In following studies, we might use more sophisticated approaches, such as that of Harada & Fukushima (2003), to perform harmonic analysis on LTE440.

Summary of estimated  .

.

4.2 Estimated accuracy

Since a lunar time ephemeris has a much more significant secular drift alongside tiny variations, we suppose that the error in the secular drift rate might dominate the accuracy of the lunar time ephemeris over the long time span. According to Eq. (7), this drift rate is inversely proportional to the distances between the Moon and other gravitational bodies. Taking the post-fit residuals of the ranging data adopted in DE440 and DE441 (see Section 5.1 in Park et al. 2021) as an order-of-magnitude estimate of the distances error, we preliminarily estimate the error of the drift rate to be about 7 × 10−20. We also find that the accuracy of LTE440 is about 0.15 ns within the year 2050. We think that a more robust estimate of accuracy may have to wait for the next version of the JPL ephemeris.

4.3 Comparison of LTE430 and LTE440

For better understanding of our lunar time ephemerides products, we compare LTE430 and LTE440. We assume that differences between them may mainly be caused by the planetary and lunar data we used, rather than by our numerical integration scheme, which has been found to be accurate enough (see Sect. 3 for details). We find that, similar to LTE440, LTE430 also has a more significant secular drift with indistinct periodic variations. For LTE430, its  , indicating the secular drift rate between TCL and TCB, is estimated as

, indicating the secular drift rate between TCL and TCB, is estimated as

(20)

and it also includes 13 periodic terms with amplitudes larger than 1 µs listed in Table 3.

(20)

and it also includes 13 periodic terms with amplitudes larger than 1 µs listed in Table 3.

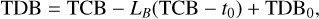

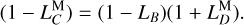

The difference between the integrands of LTE430 and LTE440 is at the level of 2 × 10−17 around the year 2000 and increases to about 2 × 10−15 over the next 600 years, as shown in Fig. 2a. After integration, the resulting LTE430 deviates from LTE440 by up to 13 ns around the year 2000, and their difference rises to about 350 ns around the year 2600, as shown in Fig. 2b. This is because these two lunar time ephemerides have slightly different  values (see Table 1 for a summary):

values (see Table 1 for a summary):

(21)

(21)

To pinpoint the cause of such a tiny yet nonzero difference, we decomposed  of LTE430 and LTE440 into their respective contributing sources (see Table 2 for details). We think that this difference arises naturally from the inclusion of 30 Kuiper belt objects and a ring in LTE440, which are absent in LTE430, since their contribution matches the figure very well. In fact, these remote Kuiper belt objects have almost four times the overall impact on

of LTE430 and LTE440 into their respective contributing sources (see Table 2 for details). We think that this difference arises naturally from the inclusion of 30 Kuiper belt objects and a ring in LTE440, which are absent in LTE430, since their contribution matches the figure very well. In fact, these remote Kuiper belt objects have almost four times the overall impact on  compared to 343 closer main belt asteroids. Regarding the periodic variations in LTE430 and LTE440, the differences between their amplitudes for identical periods do not exceed 12 ps, while their phase differences are less than 10−5 rad (see Table 3). After removal of the linear trend in Fig. 2b, the detrended difference between LTE430 and LTE440 ranges from −7.5 ns to 2.5 ns over the span from 1550 to 2650. It seems to exhibit a bimodal pattern without distinct long periodic variations, as in Fig. 2c.

compared to 343 closer main belt asteroids. Regarding the periodic variations in LTE430 and LTE440, the differences between their amplitudes for identical periods do not exceed 12 ps, while their phase differences are less than 10−5 rad (see Table 3). After removal of the linear trend in Fig. 2b, the detrended difference between LTE430 and LTE440 ranges from −7.5 ns to 2.5 ns over the span from 1550 to 2650. It seems to exhibit a bimodal pattern without distinct long periodic variations, as in Fig. 2c.

To decipher the possible reasons for such a detrended difference, we calculated the detrended contributions of each source in the difference between LTE430 and LTE440. We find that it likely traces back to three main sources: the Moon’s velocity, the Sun’s gravitational potential at the Moon, and the gravitational potentials of the Kuiper belt objects at the Moon. Their contributions to the detrended LTE430−LTE440 are shown in Figs. 3a, b and c, ranging from −4 ns to 1.5 ns, −3 ns to 1 ns, and −1.5 ns to 1 ns, respectively. The contribution of the Kuiper belt objects and ring in LTE440 exhibits an oscillation with a period of about 600 years, which may explain the bimodal shape in Fig. 2c. Adding these up reproduces the result of the detrended LTE430−LTE440.

In their work, Fukushima (1995) and Irwin & Fukushima (1999) found that the mass-dependent errors in the planetary and lunar ephemerides cause the different versions of the Earth time ephemerides, such as TE200 and TE405, to deviate from each other. However, since current planetary and lunar ephemerides have been considerably improved with much more accurate and precise masses for the gravitational bodies than those adopted in Fukushima (1995) and Irwin & Fukushima (1999), we suppose that this situation may no longer be true for our lunar time ephemerides. We estimated the effects of the mass-dependent errors between LTE430 and LTE440 on  and the amplitudes of the periodic variation using the analytic method from Fukushima (1995) (see Table 4). We find that the differences caused by these mass-dependent errors are much smaller than the deviations we observed (see Fig. 2) and are not likely the main causes.

and the amplitudes of the periodic variation using the analytic method from Fukushima (1995) (see Table 4). We find that the differences caused by these mass-dependent errors are much smaller than the deviations we observed (see Fig. 2) and are not likely the main causes.

Therefore, we think that the Kuiper belt objects and the ring in DE440 may cause the long-term deviation between LTE430 and LTE440, while the improvement in the Moon’s position and velocity, as well as the Kuiper belt objects in DE440 could explain the remainder of the detrended LTE430 − LTE440. Apart from these factors, LTE430 and LTE440 show very good consistency overall.

|

Fig. 2 Comparison of LTE430 and LTE440. (a) Difference between their derivatives: δ(dLTE/dTDB) = dLTE430/dTDB dLTE440/dTDB. (b) Difference between LTE430 and LTE440: δLTE = LTE430 − LTE440. (c) Detrended difference between LTE430 and |

Sources contributing to  in LTE430 and LTE440.

in LTE430 and LTE440.

Results of Fourier transformation analyses for the periodic terms in LTE430 and LTE440 in the form of ![${A_i}\sin [2\pi T_i^{ - 1}(t - {\rm{J}}2000.0) + {\phi _i}]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57345-25/aa57345-25-eq46.png) with the amplitude Ai > 1 µs, period Ti, and phase ϕi.

with the amplitude Ai > 1 µs, period Ti, and phase ϕi.

Differences in  and amplitudes of the periodic variations caused by the mass-dependent errors between LTE430 and LTE440.

and amplitudes of the periodic variations caused by the mass-dependent errors between LTE430 and LTE440.

|

Fig. 3 Detrended differences between main contributing sources of LTE430 and LTE440. (a) Square of Moon’s velocity |

4.4 Correction to

In their studies on numerical Earth time ephemerides, Irwin & Fukushima (1999) did not recommend determining the secular drift rate of TCG with respect to TCB using numerical approaches alone, as this procedure strongly depends on the epoch range chosen for the integration. Instead, they suggested that a much better approach to determine such a rate is to use an analytic series approximation for the Earth time ephemeris and to extract the coefficient of the linear term as the drift rate. This series approach benefits from a much longer time interval than the numerical ephemerides and enables unambiguous identification of periodic and secular terms. Considering the lower accuracy of the series compared to the numerical ephemeris, these authors proposed a hybrid approach. This method involves performing a linear least-squares fit on the residuals between a series (with its linear drift removed) and a numerical time ephemeris (with a preliminary drift rate removed). This provides a correction to the rate obtained from the numerical time ephemeris.

We think that this statement is also true for the determination of  in the lunar time ephemeris. However, we face the frustrating fact that any analytic series for the lunar time ephemeris as sophisticated as those developed for the Earth time ephemerides (Hirayama et al. 1987; Fairhead & Bretagnon 1990) is currently unavailable, and we expect that achieving such an ambitious goal will take quite a long time. Therefore, to bypass this situation and find a timely solution, we propose a mixed numerical approach to calibrate

in the lunar time ephemeris. However, we face the frustrating fact that any analytic series for the lunar time ephemeris as sophisticated as those developed for the Earth time ephemerides (Hirayama et al. 1987; Fairhead & Bretagnon 1990) is currently unavailable, and we expect that achieving such an ambitious goal will take quite a long time. Therefore, to bypass this situation and find a timely solution, we propose a mixed numerical approach to calibrate  of a short lunar time ephemeris using a much longer lunar time ephemeris. Since LTE441 has a much longer time span than LTE440, we used it to calibrate

of a short lunar time ephemeris using a much longer lunar time ephemeris. Since LTE441 has a much longer time span than LTE440, we used it to calibrate  . We applied a linear least-squares fit to the residuals between LTE441 and LTE440, both of which are linearly detrended. This fit provides a correction to the numerical value of

. We applied a linear least-squares fit to the residuals between LTE441 and LTE440, both of which are linearly detrended. This fit provides a correction to the numerical value of  that is independent of the numerical value of

that is independent of the numerical value of  . Consequently, we find the calibrated

. Consequently, we find the calibrated  to be

to be

(22)

which is slightly greater than

(22)

which is slightly greater than  . This slows down the drift between TCL and TCB by removing the long-term periodic contribution from the secular drift rate. See Eq. (14).

. This slows down the drift between TCL and TCB by removing the long-term periodic contribution from the secular drift rate. See Eq. (14).

5 Conclusions

We presented a numerical lunar time ephemeris package LTE440, which contains the data files of the evaluated relativistic time-dilation integral and software functions to calculate transformations among TCL, TCB, and TDB. We computed the integral by using a tenth-order Romberg scheme with quantities from the JPL ephemeris DE440 and produced the data files via thirteenth-degree Chebyshev polynomials for interpolation. The accuracy of LTE440 is estimated to be better than 0.15 ns within the lunar time ephemeris and 7 × 10−20 in its secular drift rate up to the year 2050. We believe these levels of accuracy satisfy the most current needs.

We also made two auxiliary lunar time ephemeris packages, LTE430 and LTE441, based on DE430 and DE441, respectively, for performance assessment. A detailed comparison of LTE430 and LTE440 reveals good overall agreement, with the observed discrepancies attributable to the existence of Kuiper belt objects and the improvement in Moon’s motion in DE440. To better separate secular drift from periodic variations, we calibrated the long-term change rate of TCL and TCB in LTE440 with the help of LTE441.

We believe that an external comparison of LTE440 with other lunar time ephemerides based on INPOP21a and EMP2021 would be helpful to understand their performances and characteristics. A comparison of the modeling assumptions across these ephemerides as well as the differences in secular drift rates and periodic components among the resulting lunar time ephemerides may provide further insights and useful information for lunar timekeeping efforts. We leave this for future work.

Data availability

The files of LTE440, including the ephemeris SPICE kernel files together with some demo files, are available online at https://github.com/xlucn/LTE440.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the Strategic Priority Research Program on Space Science of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA300103000, XDA30040000, XDA30030000 and XDA0350300) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 62394350, No. 62394351 and No. 12273116).

References

- Ashby, N., & Patla, B. R. 2024, AJ, 168, 112 [Google Scholar]

- Brumberg, V. A., Bretagnon, P., & Guinot, B. 1996, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 64, 231 [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J. O. 1985, in Lunar Bases and Space Activities of the 21st Century, ed. W. W. Mendell, 293 [Google Scholar]

- Dirkx, D., Noomen, R., Visser, P. N. A. M., Gurvits, L. I., & Vermeersen, L. L. A. 2016, A&A, 587, A156 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R. T., Hobbs, G. B., & Manchester, R. N. 2006, MNRAS, 372, 1549 [Google Scholar]

- Fairhead, L., & Bretagnon, P. 1990, A&A, 2 c2q29, 240 [Google Scholar]

- Fienga, A., Deram, P., Di Ruscio, A., et al. 2021, Notes Scientifiques et Techniques de l’Institut de Mecanique Celeste, 110 [Google Scholar]

- Fish, V. L., Shea, M., & Akiyama, K. 2020, Adv. Space Res., 65, 821 [Google Scholar]

- Folkner, W. M., Williams, J. G., Boggs, D. H., Park, R. S., & Kuchynka, P. 2014, Interplanet. Netw. Prog. Rep., 42-196, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima, T. 1995, A&A, 294, 895 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Gurvits, L. I. 1998, Highlights Astron., 11B, 985 [Google Scholar]

- Gurvits, L. I., Paragi, Z., Amils, R. I., et al. 2022, Acta Astron., 196, 314 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harada, W., & Fukushima, T. 2003, AJ, 126, 2557 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hirayama, T., Kinoshita, H., Fujimoto, M. K., & Fukushima, T. 1987, in Twentieth Symposium on Celestial Mechanics, eds. H. Kinoshita, H. Nakai, & M. Yoshikawa (Berlin: Springer), 75 [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, G. B., Edwards, R. T., & Manchester, R. N. 2006, MNRAS, 369, 655 [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, B., Gurvits, L. I., Wielgus, M., et al. 2023, Acta Astron., 213, 681 [Google Scholar]

- IAU 2006, Resolution B3: “Re-definition of Barycentric Dynamical Time, TDB”, https://www.iau.org/Iau/Publications/List-of-Resolutions [Google Scholar]

- IAU 2024a, Resolution II: “to establish a standard Lunar Celestial Reference System (LCRS) and Lunar Coordinate Time (TCL)”, https://www.iau.org/Iau/Publications/List-of-Resolutions [Google Scholar]

- IAU 2024b, Resolution III: “on the establishment of a coordinated lunar time standard by international agreement”, https://www.iau.org/Iau/Publications/List-of-Resolutions [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, A. W., & Fukushima, T. 1999, A&A, 348, 642 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Klioner, S. A. 2003, AJ, 125, 1580 [Google Scholar]

- Kopeikin, S. M., & Kaplan, G. H. 2024, Phys. Rev. D, 110, 084047 [Google Scholar]

- Kurdubov, S. L., Pavlov, D. A., Mironova, S. M., & Kaplev, S. A. 2019, MNRAS, 486, 815 [Google Scholar]

- Lindegren, L., & Dravins, D. 2003, A&A, 401, 1185 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X., Yang, T.-N., & Xie, Y. 2025, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2506.19213], Lunar Time Ephemeris LTE440: User Manual, https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.19213 [Google Scholar]

- Müller, J., Soffel, M., & Klioner, S. A. 2008, J. Geodesy, 82, 133 [Google Scholar]

- Newhall, X. X. 1989, Celest. Mech., 45, 305 [Google Scholar]

- Nothnagel, A., Nilsson, T., & Schuh, H. 2018, Space Sci. Rev., 214, 66 [Google Scholar]

- Park, R. S., Folkner, W. M., Williams, J. G., & Boggs, D. H. 2021, AJ, 161, 105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pitjeva, E., Pavlov, D., Aksim, D., & Kan, M. 2022, IAU Symp., 364, 220 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Vetterling, W. T., & Flannery, B. P. 1992, Numerical Recipes in FORTRAN: The Art of Scientific Computing, 2nd edn. (New York: Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Roelofs, F., Fromm, C. M., Mizuno, Y., et al. 2021, A&A, 650, A56 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, L., Čunderlík, R., Dayoub, N., et al. 2016, J. Geodesy, 90, 815 [Google Scholar]

- Seidelmann, P. K., & Fukushima, T. 1992, A&A, 265, 833 [Google Scholar]

- Soffel, M., Klioner, S. A., Petit, G., et al. 2003, AJ, 126, 2687 [Google Scholar]

- Turyshev, S. G., Williams, J. G., Boggs, D. H., & Park, R. S. 2025, ApJ, 985, 140 [Google Scholar]

The data files of LTE440 are available online at https://github.com/xlucn/LTE440

The SPICE (Spacecraft, Planet, Instrument, C-matrix, Events) is an information system built by JPL, see https://naif.jpl.nasa.gov/naif/aboutspice.html

Appendix A Key information for DE430, DE440, and DE441

Comparison of DE430, DE440, and DE441

All Tables

Results of Fourier transformation analyses for the periodic terms in LTE430 and LTE440 in the form of ![${A_i}\sin [2\pi T_i^{ - 1}(t - {\rm{J}}2000.0) + {\phi _i}]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57345-25/aa57345-25-eq46.png) with the amplitude Ai > 1 µs, period Ti, and phase ϕi.

with the amplitude Ai > 1 µs, period Ti, and phase ϕi.

Differences in  and amplitudes of the periodic variations caused by the mass-dependent errors between LTE430 and LTE440.

and amplitudes of the periodic variations caused by the mass-dependent errors between LTE430 and LTE440.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Differences between our reproduced version of TT − TDB at the geocenter using the planetary data of DE440 and the inherent version of DE440. Top panel: difference between the derivatives δ[d(TT − TDB)/dTDB] = [d(TT − TDB)/dTDB]this [d(TT − TDB)/dTDB]DE440. Bottom panel: −difference between the Earth time ephemerides δ(TT − TDB) = (TT − TDB)this − (TT − TDB)DE440. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Comparison of LTE430 and LTE440. (a) Difference between their derivatives: δ(dLTE/dTDB) = dLTE430/dTDB dLTE440/dTDB. (b) Difference between LTE430 and LTE440: δLTE = LTE430 − LTE440. (c) Detrended difference between LTE430 and |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Detrended differences between main contributing sources of LTE430 and LTE440. (a) Square of Moon’s velocity |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.