| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A111 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| Section | Atomic, molecular, and nuclear data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557636 | |

| Published online | 08 December 2025 | |

Nuclear spin effects in ammonia chemistry

Ion trap study of NH3+ and NH4+ formation

Department of Surface and Plasma Science, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Charles University,

V Holešovičkách 2,

180 00

Prague,

Czech Republic

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

10

October

2025

Accepted:

3

November

2025

Aims. We investigate whether the nuclear-spin state of H2 (ortho or para state) modifies the kinetics of two key reactions in ammonia formation in the interstellar medium: NH2+ + H2 → NH3+ + H and NH3+ + H2 → NH4+ + H.

Methods. The reaction rate coefficients were measured in a cryogenic 22-pole radiofrequency ion trap over 15-270 K using normal H2 (ortho-to-para ratio 3 : 1) and para-enriched H2 (99.5% para-H2) produced by catalytic conversion at ≈15 K.

Results. For NH2+ + H2, the reaction rate coefficients are in the range 10−10-10−9 cm3 s−1 with a weak negative temperature dependence. For NH3+ + H2, the reaction rate coefficients exhibit an Arrhenius dependence with an activation energy of ≈90 meV at high temperatures (>100 K), combined with an increasing value towards low temperatures (10-100 K) due to quantum tunneling. In the studied range of temperatures, the reaction rate coefficients obtained with para-enriched and normal H2 are indistinguishable within the experimental uncertainty for both reactions.

Key words: astrochemistry / molecular data / methods: laboratory: molecular / ISM: molecules

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Ammonia (NH3) is one of the most observed molecules in the interstellar medium (ISM), serving as a key diagnostic tool for understanding the physical and chemical conditions of interstellar clouds (Le Gal et al. 2014; Millar 2015; Sipilä et al. 2015; Redaelli et al. 2023). Its high abundance and unique chemical properties make it an important actor in astrochemical networks, especially in the formation of more complex nitrogen-bearing species. However, ammonia’s behavior in the ISM is also greatly affected by the quantum mechanical nature of its hydrogen atoms, rather than being determined solely by its molecular structure. Specifically, ammonia can exist in two different nuclear spin states, ortho and para, due to the different spins of its hydrogen nuclei (Sipilä et al. 2015).

To understand these properties, it is useful to first consider molecular hydrogen (H2), the most abundant molecule in the ISM. Molecular hydrogen exists in two nuclear spin configurations: ortho-H2 (I = 1) and para-H2 (I = 0). Due to the Pauli exclusion principle, these nuclear spin states correspond to different rotational energy levels, with ortho-H2 occupying odd- J states and para-H2 occupying even- J states.

Similarly, ortho-NH3 has a total nuclear spin of I = 3/2, while para-NH3 has a total nuclear spin of I = 1 /2. The nuclear spin states of the ammonia molecule are also coupled to its rotational levels, consequently influencing its internal energy.

This distinction has significant implications for ion-molecule reactions. Since the transitions between these spin states are forbidden in nonreactive processes, their populations are often far from equilibrium in the ISM, indicating that ortho-H2, para-H2, ortho-NH3, and para-NH3 should be considered distinct species in chemical models (Millar 2015; Öberg 2016; Faure et al. 2013; Harju et al. 2024).

The observed ortho-to-para ratios of ammonia in the ISM are often found to be less than 1 (Faure et al. 2013). These nonthermal populations cannot be explained by heterogeneous formation on dust or ice surfaces, and gas-phase chemistry must be invoked to explain the observations. The formation of ammonia in the gas-phase proceeds through a sequence of hydrogen abstraction reactions (Le Gal et al. 2014):

followed by dissociative recombination of NH4+ with electrons. The ortho-to-para ratio of ammonia is therefore tightly linked to the nuclear spin population of NH4+ and, consequently, to the nuclear spin selection rules in the hydrogen abstraction reactions (Faure et al. 2013).

Beyond nuclear spin effects, the internal energy of H2 plays a crucial role in ion-molecular reactions. Ortho-H2, with its lowest rotational state at J = 1 (15 meV above the ground state, Huber & Herzberg 1979), carries significantly more internal energy than para-H2, which resides in the J = 0 state at low temperatures. This additional energy could impact reaction rates through enhanced activation or quantum tunneling mechanisms (Mohandas et al. 2020; Zhu et al. 2022). Statistical models commonly assume a temperature-independent branching ratio for ortho-H2 and para-H2 reactions. Nevertheless, laboratory measurements reveal that reaction rates may be significantly influenced by the internal energy of H2, which is coupled to its nuclear spin state (Zymak et al. 2013; Roučka et al. 2018).

To quantify these effects in the process of ammonia formation, we specifically focus on the following ion-neutral reactions leading to the formation of ammonium (NH4+) in the ISM:

Although previous studies have established temperaturedependent behavior for these reactions, they have not taken into account the nuclear spin states of the reactants, leading to possible ambiguities in astrochemical modeling.

The reaction of NH2+ with H2 has been experimentally studied at 300 K by Kim et al. (1975); Adams et al. (1980), and the only experiments performed at lower temperatures were ion trap studies by Gerlich (1993); Rednyk et al. (2019). However, the data of Gerlich (1993) may be influenced by the internal excitation of NH2+, as discussed by Rednyk et al. (2019). These studies revealed that the reaction rate coefficient increases with decreasing temperature between 300 K and 40 K, with a possible flat maximum between 20 K and 40 K. Following these experimental efforts, theoretical treatments of reaction energetics and rate coefficients were developed using transition-state theory (TST, Mohandas et al. 2020) and quasiclassical trajectory calculations (QCT, Zhu et al. 2022). Surprisingly, the TST calculations predict an activation energy between 15 meV and 32 meV because of vibrational zero-point energy effects, with the reaction proceeding via quantum tunneling at low energies. This is in contrast to the calculations of Zhu et al. (2022) that predict a submerged barrier, and thus no tunneling and zero activation energy. Neither of these theoretical approaches accounts for the effects of nonthermal nuclear spin populations. Given that the predicted barrier height is comparable to the rotational energy of ortho-H2 , a significant influence of rotational excitation on the reaction rate can be expected. However, it remains unclear whether the reaction rate coefficient should increase with rotational excitation as a result of a higher available energy or decrease due to a lower tunneling probability.

The reaction of NH3+ with H2 has attracted considerable scientific interest for its fundamental relevance and its role in the formation of NH3 in interstellar clouds (Herbst & Klemperer 1973; Le Gal et al. 2014). Numerous experiments (Luine & Dunn 1985; Böhringer 1985; Barlow & Dunn 1987; Rednyk et al. 2019) have shown the existence of an activation energy of about 0.09 eV (Fehsenfeld et al. 1975), which determines the temperature dependence of its rate coefficient at high temperatures (T > 100 K). At lower temperatures, the kinetics is dominated by quantum tunneling from a pre-reactive complex. Theoretical studies of this reaction (Herbst et al. 1991; Álvarez-Barcia et al. 2016; Hashimoto et al. 2023; Zhu et al. 2025) support these findings. The most recently calculated zero-point-energy-corrected energies of the pre-reactive state and transition state are -0.04 and 0.11 eV, respectively, consistent with the observed activation energy (identical energies calculated by Hashimoto et al. 2023 and Zhu et al. 2025 at CCSD(T)-F12b/cc-pV5Z and UCCSD(T)-F12a/aug-cc-pVQZ levels of theory, respectively).

To our knowledge, none of these studies has addressed how the nuclear spin state of the H2 reactant affects the reaction of NH2+ and NH3+ with H2. This omission is rather surprising, given the strong temperature dependence of the reaction rate coefficients, which seems to imply that the available rotational energy of ortho-H2 may affect the reaction rate coefficients as well, similarly to the role of vibrational zero point energy observed in the previous studies of isotope effects in reaction (3) (Adams & Smith 1984; Barlow & Dunn 1987).

In the absence of experimental data, current astrochemical models typically assume equal reaction rate coefficients for both spin isomers and statistical product branching fractions (Le Gal et al. 2014; Harju et al. 2017; Sipilä et al. 2019). However, as discussed above, this assumption may be violated at low temperatures, where the rotational energy of ortho-H2 becomes significant. This work aims to improve the reliability of astrochemical models by providing state-specific reaction rate coefficients.

2 Experiment

The experiments were carried out using a linear 22-pole cryogenic radiofrequency (RF) ion trap apparatus, which operates at nominal temperatures T22PT ranging from 10 K to 300 K. The apparatus confines the ions using inhomogeneous RF fields, as described by Gerlich (1992). Based on previous measurements and characterizations of the ion trap (Kovalenko et al. 2018; Plasil et al. 2023), we assume that the kinetic temperature of the ions, T, is close to the trap temperature, T = T22PT + (5 ± 5) K. The detailed description of the experimental setup can be found in Zymak et al. (2013); Kovalenko et al. (2018), and only a short overview is given here.

The primary ions (NH2+ and NH3+) were produced in the storage ion source by electron bombardment of an equal-pressure mixture of hydrogen (H2) and nitrogen (N2) at a total pressure of approximately 10−6 mbar. The electron energy was set to 55 eV, which ensured the efficient production of the desired ions. The ions are periodically extracted from the ion source, then mass-selected using the first quadrupole mass filter and directed into the 22-pole trap through a 90° electrostatic quadrupole bender. The 22-pole ion trap consists of 22 parallel electrodes that are connected alternately to the opposite phases of RF potential to generate an effective potential for the radial confinement of the ions (Gerlich & Horning 1992). Inside the trap, the ions are thermalized to the trap temperature through collisions with a helium buffer gas. The helium number density in the trap is typically in the range of 1013 to 1014 cm−3, which is sufficient to thermalize the ions within a few milliseconds.

The thermal nuclear spin state ratio at 300 K between ortho-H2 and para-H2 populations is 3:1. Here and in the following text, such reactant gas is denoted as normal H2 . A key aspect of our experimental setup is the use of para-enriched hydrogen, which is produced by catalytic conversion of normal hydrogen at low temperatures (approximately 15 K) (Hejduk et al. 2012; Zymak et al. 2013). The typical nuclear spin state composition is 99.5% para-H2 and 0.5% ortho-H2 (Zymak et al. 2013).

The number density of the reactant in the trap is determined using a Bayard-Alpert ionization gauge in the vacuum chamber containing the ion trap, calibrated by a spinning rotor gauge connected directly to the trap volume. Both gauges are operated at room temperature (Troom) and the number density of reactant in the trap, ng, is calculated from the number density of reactant in the spinning rotor gauge, nroom, using the relation for thermal transpiration in the molecular regime, ng = nroom √Troom∕Tg, where Tg is the gas temperature in the trap. The total uncertainty of this procedure is estimated to be 20%. This leads to a 20% systematic uncertainty in determining the reaction rate coefficient. Only statistical uncertainties are shown for the present data in Figures 2 and 4.

After a controlled reaction time, the ions are extracted from the trap, analyzed using a second quadrupole mass filter, and counted using a microchannel plate detector. The standard measurement procedure involves filling the ion trap at a fixed frequency with a well-defined number of primary ions and analyzing the contents of the trap after different trapping (reaction) times, which allows us to observe the loss of primary ions and the formation of reaction products as a function of trapping time. The data were analyzed by fitting the observed decay curves of the primary ions with an exponential decay model, n(t) = n0 exp(-rt), with the initial number of ions n0 and the reaction rates r as free parameters. The corresponding reaction rate coefficients were calculated by dividing the fitted rates by the reactant number density. In Figures 1 and 3, the numbers of the product ions, n′ were fit with a complementary function n′(t) = n′0 + n0(1 - exp(-rt)). The difference of detection efficiencies of the reactant and product ions is less than 10 %, and the presented data have been corrected for this mass discrimination.

|

Fig. 1 Dependence of normalized numbers of NH2+ (circles) and NH3+ (squares) ions in the trap on storage time t. The crosses (Σ) show the total number of ions. The lines are the fits of the data. The data were measured at T = 31 K and a para-enriched H2 number density of 3.1 × 1011 cm−3. |

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Reaction NH2+ + H2

The typical experimental data obtained after the injection of NH2+ into the trap filled with para-enriched H2 are plotted in Figure 1, which shows the time evolution of normalized counts of NH2+ and NH3+ ions measured at a collision temperature of 31 K and number density of para-enriched H2 of 3.1 × 1011 cm 3. The detected ion counts are normalized by the initial number of all ions, n∑0.

The exponential decrease in the primary NH2+ ion counts is coupled with a corresponding increase in the NH3+ product counts due to reaction (2). The sum of all ion counts is plotted as crosses and denoted by Σ.

The rate coefficients of reaction (2) were determined from the fitted loss rates of NH2+ ions. The temperature dependence of the reaction rate coefficients for the reaction (2) measured between 15 and 270 K is plotted in Figure 2. The figure shows that the values of the reaction rate coefficient obtained for normal and para-enriched H2 are the same within the experimental error.

The present results for reactions with normal H2 are in excellent agreement with earlier low-temperature measurements performed using normal H2 by Rednyk et al. (2019), indicating the consistency and reproducibility of our results. Our measurements confirm a relatively fast reaction, characterized by rate coefficients of the order of 10−10 cm3 s−1 across the entire temperature range studied, accompanied by a weak negative temperature dependence.

The insensitivity of reaction (2) to the internal excitation of the used H2 gas is rather surprising. According to Mohandas et al. (2020), reaction (2), although highly exoergic, has to proceed through a small barrier, whose height is comparable with the rotational spacing of the two lowest rotational states in the H2 molecule.

It is possible that the thermal activation of the reaction is compensated for by a reduced tunneling probability due to the shorter pre-reactive complex lifetime at higher collision energies, or, in accordance with Zhu et al. (2022), dynamical effects may be responsible for the observed kinetics in the absence of a reaction barrier. Further theoretical studies are needed to understand these observations.

While the UMIST database (Millar et al. 2024) lists for reaction (2) a value that approximates the data measured by Rednyk et al. (2019) in agreement with present results, the KIDA database (Wakelam et al. 2024) recommends a value of 1.2 × 10−10 cm3 s−1 in the temperature range of 10-280 K or 1.95 × 10−10 cm3 s−1 at 300 K. This could lead to the underestimation of the NH3+ production at low temperatures prevalent in the diffuse interstellar medium.

To facilitate the use of our data in astrochemical models, we fit the measured temperature dependences of NH2+ + H2 reaction rate coefficients with the Arrhenius Kooij formula,  . The fitted curves and their confidence bands are indicated in Figure 2. For the reaction with paraenriched H2, the fit parameters are α = 3.6(7) × 10−10 cm3 s−1, β = -0.69(24), γ = 25(12) K, and for the reaction with normal H2, we have α = 3.2(4) × 10−10 cm3 s−1, β = -0.43(21), γ = 9(10) K. The uncertainties of the parameters are given in parentheses. The 1σ confidence bands in Figure 2 indicate that these curves are again identical within the uncertainty. These parameters are valid in the temperature range of 15-270 K.

. The fitted curves and their confidence bands are indicated in Figure 2. For the reaction with paraenriched H2, the fit parameters are α = 3.6(7) × 10−10 cm3 s−1, β = -0.69(24), γ = 25(12) K, and for the reaction with normal H2, we have α = 3.2(4) × 10−10 cm3 s−1, β = -0.43(21), γ = 9(10) K. The uncertainties of the parameters are given in parentheses. The 1σ confidence bands in Figure 2 indicate that these curves are again identical within the uncertainty. These parameters are valid in the temperature range of 15-270 K.

|

Fig. 2 Temperature dependence of the reaction rate coefficient for reaction NH2+ + H2 → NH3+ + H. The present data obtained using normal H2 (pentagons) and para-enriched H2 (diamonds) are compared to values obtained in normal hydrogen by Rednyk et al. (2019); Kim et al. (1975); Adams et al. (1980). The Langevin capture rate coefficient kL, the calculated value by Mohandas et al. (2020), and the present values in the KIDA and UMIST databases are indicated by lines (see legend for explanation of the symbols). The Arrhenius Kooij fits of the present data are indicated by lines with 1σ confidence bands. |

|

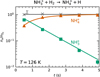

Fig. 3 Dependence of the normalized numbers of NH3+ (squares) and NH4+ (triangles) ions in the trap on storage time measured at T = 126 K and para-enriched hydrogen number density of 5.1 × 1012 cm−3. |

3.2 Reaction NH3+ + H2

An example of the time evolution of the detected numbers of primary (NH3+) and product (NH4+) ions in the trap at 126 K, and para-enriched H2 number density of 5.1 × 1012 cm−3, is shown in Figure 3. As can be seen from the figure, NH3+ ions are converted to NH4+ via ion molecule reaction (3).

To investigate the potential influence of hydrogen nuclear spin states on reaction dynamics, we measured the reaction rate coefficients across a temperature range from 15 to 270 K using both normal and para-enriched hydrogen. The temperature dependence of the measured reaction rate coefficients is presented in Figure 4. Our results for normal H2 are in excellent agreement with previous experimental studies Fehsenfeld et al. (1975); Smith & Adams (1981); Böhringer (1985); Gerlich (1993); Rednyk et al. (2019).

The most significant finding is the complete consistency between the reaction rate coefficients measured in the present study with para-enriched H2 and those measured with normal H2. As clearly shown in Figure 4, the data points for the spin isomers of H2 are, within the experimental uncertainty, identical across the entire temperature range. This observation holds true not only in the high-temperature regime, but also in the low-temperature quantum tunneling regime (T < 100 K).

The barrier for reaction (3) is 0.11 eV (Hashimoto et al. 2023), which is substantially higher than the energy difference between the two lowest para and ortho states in the H2 molecule. Therefore, it could be expected that the difference between measurements with normal and para-enriched H2 at temperatures above 100 K will be small.

However, at low collisional energies, the reaction proceeds mainly via tunneling from a pre-reactive complex (Álvarez-Barcia et al. 2016; Hashimoto et al. 2023) that is located at a minimum of the potential energy surface of approximately -0.04 eV. The order-of-magnitude increase of the reaction rate coefficient with a decrease in temperature between 100 and 10 K indicates that the lifetime of the pre-reactive complex, and thus also the tunneling probability, is highly sensitive to the collision energy. Since the rotational energy of the J = 1 ortho-H2 state is equivalent to the mean kinetic energy ( kBT) at T = 114 K, we may anticipate that the rotational excitation will also affect the complex lifetime and reaction probability. Nevertheless, the values of the reaction rate coefficients for reaction (3) measured using normal and para-enriched H2 are practically the same. This indicates that the translational and rotational energies are not equivalent in determining the complex lifetime. That is, the rotational motion is not efficiently coupled to the other degrees of freedom in the weakly bound pre-reactive complex.

kBT) at T = 114 K, we may anticipate that the rotational excitation will also affect the complex lifetime and reaction probability. Nevertheless, the values of the reaction rate coefficients for reaction (3) measured using normal and para-enriched H2 are practically the same. This indicates that the translational and rotational energies are not equivalent in determining the complex lifetime. That is, the rotational motion is not efficiently coupled to the other degrees of freedom in the weakly bound pre-reactive complex.

We also considered the possibility of stabilization of the complex by a collision with a third particle (He or H2), which may effectively remove the excess energy in collisions with ortho-H2. However, the results of Böhringer (1985) show that collisions with ambient gas do not play a significant role at gas number densities below 1016 cm−3, i.e., two orders of magnitude above the present experimental conditions.

|

Fig. 4 Temperature dependence of the reaction rate coefficient for the reaction NH3+ + H2 → NH4+ + H. The present data obtained using normal H2 (pentagons) and para-enriched H2 (diamonds) are compared to values measured previously in normal hydrogen (Fehsenfeld et al. 1975; Smith & Adams 1981; Luine & Dunn 1985; Böhringer & Arnold 1985; Böhringer 1985; Kim et al. 1975; Gerlich 1993; Rednyk et al. 2019), and to the theoretical predictions by Álvarez-Barcia et al. (2016); Hashimoto et al. (2023) and Zhu et al. (2025) (see legend for description of the symbols). |

4 Conclusion

Using a cryogenic 22 pole RF ion trap with both normal and para-enriched H2, we observed that the nuclear spin state of the reactant H2 gas does not affect the kinetics of NH2+ + H2 and NH3+ + H2 reactions between 15 and 270 K. In the case of the NH2+ + H2 reaction, this observation should be considered in future theoretical studies in order to further investigate the nature of the transition state and the possibility of a positive reaction barrier. For the NH2+ + H2 reaction, our results indicate that the tunneling mechanism that governs the behavior of this reaction at low temperatures is not substantially influenced by rotational excitation of the incident H2 molecule.

Molecular hydrogen in the ISM often exhibits nonequilibrium ortho-to-para ratios, which vary widely according to local conditions (Albertsson et al. 2014). Our experimental results confirm that these fundamental reactions remain unaffected by H2 rotational excitation in ammonia molecular systems, validating the use of unified rate coefficients in statistical rate theories, independent of variations in ortho-to-para ratios. This significantly simplifies the chemical modeling of ammonia formation in interstellar environments and eliminates a possible source of uncertainty in astrochemical networks.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on the open data repository platform Zenodo and are accessible under the DOI 10.5281/zenodo.17311246.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Czech Science Foundation project GACR 23-05439S. O.E.H.A. was partly funded by the Mexican agency for Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation (SECIHTI; scholarship no. 836571).

References

- Adams, N. G., & Smith, D. 1984, Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process., 61, 133 [Google Scholar]

- Adams, N. G., Smith, D., & Paulson, J. F. 1980, J. Chem. Phys., 72, 288 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Albertsson, T., Indriolo, N., Kreckel, H., et al. 2014, Astrophys. J., 787, 44 [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Barcia, S., Russ, M.-S., Meisner, J., & Kästner, J. 2016, Faraday Discuss., 195, 173 [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, S., & Dunn, G. 1987, Int. J. Mass Spectrom. Ion Process., 80, 227 [Google Scholar]

- Böhringer, H. 1985, Chem. Phys. Lett., 122, 185 [Google Scholar]

- Böhringer, H., & Arnold, F. 1985, in NATO ASI Series, 157, Molecular Astrophysics (Dordrecht: Springer), 639 [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Hily-Blant, P., Le Gal, R., Rist, C., & Pineau des Forêts, G. 2013, Astrophys. J. Lett., 770, L2 [Google Scholar]

- Fehsenfeld, F. C., Lindinger, W., Schmeltekopf, A. L., Albritton, D. L., & Ferguson, E. E. 1975, J. Chem. Phys., 62, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich, D. 1992, in Advances in Chemical Physics (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd), 1 [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich, D. 1993, J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans., 89, 2199 [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich, D., & Horning, S. 1992, Chem. Rev., 92, 1509 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harju, J., Daniel, F., Sipilä, O., et al. 2017, Astron. Astrophys., 600, A61 [Google Scholar]

- Harju, J., Pineda, J. E., Sipilä, O., et al. 2024, Astron. Astrophys., 682, A8 [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, Y., Takayanagi, T., & Murakami, T. 2023, ACS Earth Space Chem., 7, 623 [Google Scholar]

- Hejduk, M., Dohnal, P., Varju, J., et al. 2012, Plasma Sources Sci. Technol., 21, 024002 [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, E., & Klemperer, W. 1973, Astrophys. J., 185, 505 [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, E., DeFrees, D., Talbi, D., et al. 1991, J. Chem. Phys., 94, 7842 [Google Scholar]

- Huber, K. P., & Herzberg, G. 1979, Molecular Spectra And Molecular Structure, Vol. IV, Molecular Spectra And Molecular Structure: Constants Of Diatomic Molecules (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold) [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. K., Theard, L. P., & Huntress, W. T. Jr. 1975, J. Chem. Phys., 62, 45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko, A., Tran, T. D., Rednyk, S., et al. 2018, Astrophys. J., 856, 100 [Google Scholar]

- Le Gal, R., Hily-Blant, P., Faure, A., et al. 2014, Astron. Astrophys., 562, A83 [Google Scholar]

- Luine, J. A., & Dunn, G. H. 1985, Astrophys. J. Lett., 299, L67 [Google Scholar]

- Millar, T. J. 2015, Plasma Sources Sci. Technol., 24, 31 [Google Scholar]

- Millar, T. J., Walsh, C., Van de Sande, M., & Markwick, A. J. 2024, Astron. Astrophys., 682, A109 [Google Scholar]

- Mohandas, S., Ramabhadran, R. O., & Kumar, S. S. 2020, J. Phys. Chem. A, 124 [Google Scholar]

- Öberg, K. I. 2016, Chem. Rev., 116, 9631 [Google Scholar]

- Plasil, R., Uvarova, L., Rednyk, S., et al. 2023, Astrophys. J., 948, 131 [Google Scholar]

- Redaelli, E., Bizzocchi, L., Caselli, P., & Pineda, J. E. 2023, Astron. Astrophys., 674, L8 [Google Scholar]

- Rednyk, S., Roucka, S., Kovalenko, A., et al. 2019, Astron. Astrophys., 625, A74 [Google Scholar]

- Roucka, S., Rednyk, S., Kovalenko, A., et al. 2018, Astron. Astrophys., 615, L6 [Google Scholar]

- Sipilä, O., Caselli, P., & Harju, J. 2015, Astron. Astrophys., 578, A55 [Google Scholar]

- Sipilä, O., Caselli, P., & Harju, J. 2019, Astron. Astrophys., 631, A63 [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D., & Adams, N. G. 1981, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc., 197, 377 [Google Scholar]

- Wakelam, V., Gratier, P., Loison, J.-C., et al. 2024, Astron. Astrophys., 689, A63 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y., Li, R., & Song, H. 2022, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 24, 25663 [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y., Qi, Y., Ping, L., & Xie, X. 2025, J. Chem. Phys., 163, 014306 [Google Scholar]

- Zymak, I., Hejduk, M., Mulin, D., et al. 2013, Astrophys. J., 768, 86 [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Dependence of normalized numbers of NH2+ (circles) and NH3+ (squares) ions in the trap on storage time t. The crosses (Σ) show the total number of ions. The lines are the fits of the data. The data were measured at T = 31 K and a para-enriched H2 number density of 3.1 × 1011 cm−3. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Temperature dependence of the reaction rate coefficient for reaction NH2+ + H2 → NH3+ + H. The present data obtained using normal H2 (pentagons) and para-enriched H2 (diamonds) are compared to values obtained in normal hydrogen by Rednyk et al. (2019); Kim et al. (1975); Adams et al. (1980). The Langevin capture rate coefficient kL, the calculated value by Mohandas et al. (2020), and the present values in the KIDA and UMIST databases are indicated by lines (see legend for explanation of the symbols). The Arrhenius Kooij fits of the present data are indicated by lines with 1σ confidence bands. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Dependence of the normalized numbers of NH3+ (squares) and NH4+ (triangles) ions in the trap on storage time measured at T = 126 K and para-enriched hydrogen number density of 5.1 × 1012 cm−3. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Temperature dependence of the reaction rate coefficient for the reaction NH3+ + H2 → NH4+ + H. The present data obtained using normal H2 (pentagons) and para-enriched H2 (diamonds) are compared to values measured previously in normal hydrogen (Fehsenfeld et al. 1975; Smith & Adams 1981; Luine & Dunn 1985; Böhringer & Arnold 1985; Böhringer 1985; Kim et al. 1975; Gerlich 1993; Rednyk et al. 2019), and to the theoretical predictions by Álvarez-Barcia et al. (2016); Hashimoto et al. (2023) and Zhu et al. (2025) (see legend for description of the symbols). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![\mathrm{N+ ->[+H2] NH+ ->[+H2] NH2+ ->[+H2] NH3+ ->[+H2] NH4+},](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57636-25/aa57636-25-eq1.png)

![\ce{NH2+ + ^{o/p}H2 &->[\mathit{k}_{\ce{NH2+}}] NH3+ + H}, \label{NH2p_to_NH3p}\\](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57636-25/aa57636-25-eq2.png)

![\ce{NH3+ + ^{o/p}H2 &->[\mathit{k}_{\ce{NH3+}}] NH4+ + H}. \label{NH3p_to_NH4p}](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa57636-25/aa57636-25-eq3.png)