| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L18 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Letters to the Editor | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202558117 | |

| Published online | 18 December 2025 | |

Letter to the Editor

Vibrationally excited H2 muting the He I triplet line at 1.08 μm on warm exo-Neptunes

1

Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Cité, CEA, CNRS, AIM, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France

2

Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Struttura della Materia, Rome, Italy

3

Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, 600 UCB, Boulder, 80309 CO, USA

4

Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences, University of Colorado, 600 UCB, Boulder, 80309 CO, USA

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

14

November

2025

Accepted:

26

November

2025

Context. Neptune-sized exoplanets (i.e., exo-Neptunes) are fundamental to the study of exoplanet diversity. Their evolution is sculpted by atmospheric escape, often traced by absorption in the H I Lyman-α line at 1216 Å and the He I triplet line at 1.08 μm. On the warm exo-Neptunes HAT-P-11 b, GJ 3470 b and GJ 436 b, H I Lyman-α absorption causes extreme in-transit obscuration of their host stars. This suggests that the He I triplet line absorption would be strong as well, yet it has only been identified on two of these planets.

Aims. We explore processes that had previously been omitted, which might act to attenuate the He I triplet line on warm exo-Neptunes. In particular, we assess the role of vibrationally excited H2 to remove the He+ ion that acts as precursor of the absorbing He(23S).

Methods. We determined thermal rate coefficients for this chemical process, leveraging the available theoretical and experimental data. The process becomes notably fast at the temperatures expected in the atmospheric layers probed by the He I triplet line.

Results. Our simulations show that this removal process severely mutes the line on GJ 3470 b and leads to the nondetection on GJ 436 b. The overall efficiency of this mechanism is connected to the location in the atmosphere of the H2-to-H transition and, ultimately, to the amount of high-energy radiation received by the planet. The process will be more significant on small exoplanets than on hotter or more massive ones since, in the latter case, the H2-to-H transition generally occurs deeper in the atmosphere.

Conclusions. Weak He I triplet line absorption does not necessarily imply the lack of a primordial, H2-He-dominated atmosphere, an idea to bear in mind when interpreting observations of other small exoplanets.

Key words: planets and satellites: atmospheres / planets and satellites: physical evolution

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Exo-Neptunes offer valuable insights into the transition between the gas giants of total mass dominated by H2-He and the ubiquitous sub-Neptunes of uncertain composition (Venturini et al. 2020; Bean et al. 2021; Ikoma & Kobayashi 2025). Although they have been extensively investigated both observationally and theoretically, major gaps remain in our understanding of the nature of exo-Neptunes. Some of these gaps are related to the fact that their interiors can often be explained by a range of possible interpretations, whereby the outer envelopes are dominated by hydrogen, astrophysical ices (e.g., H2O), and a combination thereof (Nettelmann et al. 2010; Otegi et al. 2020). Infrared (IR) spectroscopy of their atmospheres does not always break this degeneracy. Indeed, a non-negligible number of exo-Neptunes exhibit featureless transmission spectra due to the occurrence of high-altitude clouds and small atmospheric scale heights (Knutson et al. 2014; Grasser et al. 2024; Sun et al. 2024).

For exoplanets orbiting close to their host stars, the main mechanism through which they lose mass and evolve is atmospheric escape to space. Many escaping atmospheres have been probed by means of absorption lines of H I and He I, and by lines of metals such as O I, C II, or Mg II (Vidal-Madjar et al. 2003, 2004; Fossati et al. 2010; Spake et al. 2018; Yan & Henning 2018; García Muñoz et al. 2021; Czesla et al. 2022; Loyd et al. 2025). The H I Lyman-α line at 1216 Å and the He I triplet line at 1.08 μm are both prominent on exoplanets of very disparate conditions and thus useful for comparative studies. The first line arises in absorption from the ground to the lowest excited state of the H atom. The second one arises in He(23S) + hν → He(23P). The He(23S) triplet state is metastable and, in the layers probed by transmission spectroscopy, it is produced by radiative recombination, reaction R1: He+ + e− → He(i) + hν, and subsequent relaxation of the nascent states (Oklopčić & Hirata 2018). As the precursor of He(23S), the He+ ion partly controls the absorption line’s strength. The He+ ion is mostly produced by photoionization. Its loss is affected by multiple chemical-collisional-radiative disequilibrium processes (Oklopčić 2019; García Muñoz 2025), among which reaction R1 is usually important. Any investigation that builds upon the He I triplet line for characterizing the atmosphere must rely on sophisticated models and on including the leading disequilibrium processes (Oklopčić & Hirata 2018; Dos Santos et al. 2022; Lampón et al. 2023). In other words, any findings based on such models will be robust as long as the models are complete and accurate.

To date, the He I triplet line has been detected on ∼20 exoplanets, including several gas giants and sub-Neptunes, plus GJ 3090 b and TOI 1430 b, both at then frontier between sub-Neptunes and super-Earths (Dos Santos et al. 2022; Fossati et al. 2022, 2023; Vissapragada et al. 2022; Zhang et al. 2023; Orell-Miquel et al. 2024; Guilluy et al. 2024; Masson et al. 2024; Ahrer et al. 2025). Surprisingly, the number of attempted but unsuccessful detections is comparable and includes planets for which past models predicted strong absorption (Kasper et al. 2020; Rumenskikh et al. 2023). The nondetections suggest that there is more to line formation than simply competition between photoionization of ground-state He atoms by extreme ultraviolet (XUV, wavelengths < 912 Å; threshold at 504 Å), which favours reaction R1, as well as of He(23S) by longer wavelength photons, which removes it; this overall mechanism predicts K dwarfs as the best host stars for He I triplet line searches (Oklopčić 2019). To advance the understanding of the He I triplet line on small exoplanets, here we focus on three warm exo-Neptunes; namely, HAT-P-11 b, GJ 3470 b, and GJ 436 b.

2. Atmospheric escape from warm exo-Neptunes

HAT-P-11 b (Rp ∼ 4.9 R⊕, mass Mp ∼ 25 M⊕, equilibrium temperature, Teq ∼ 847 K; Basilicata et al. 2024), GJ 3470 b (3.9 R⊕, 12.6 M⊕, 615 K; Kosiarek et al. 2019), and GJ 436 b (4.2 R⊕, 23.1 M⊕, 686 K; Turner et al. 2016) are the most extensively investigated exo-Neptunes. They follow nearly polar orbits, a feature common to other exo-Neptunes. GJ 436 b’s atmospheric metallicity remains unconstrained because the measured transmission and emission spectra are featureless (Knutson et al. 2014; Grasser et al. 2024; Mukherjee et al. 2025). There are significant uncertainties in the metallicities of the other two planets. Early observations suggested modest values (Benneke et al. 2019; Chachan et al. 2019; Sun et al. 2024), but the view may be changing and recent JWST data suggest that GJ 3470 b’s atmospheric metallicity is ×100 solar (Beatty et al. 2024).

The H I Lyman-α line has been detected on all three warm exo-Neptunes, consistently showing strong absorption that extends well out of the optical transit (Kulow et al. 2014; Ehrenreich et al. 2015; Bourrier et al. 2018; Ben-Jaffel et al. 2022). In the line wings, at hundred or more km/s from the core typically hidden by interstellar medium absorption, the H atoms that enshroud the planets obscure their host stars by up to a few times their optical radii (García Muñoz et al. 2020). The He I triplet line has been detected at each published attempt on HAT-P-11 b (Allart et al. 2018, 2023; Mansfield et al. 2018; Guilluy et al. 2024). The planet’s opaque radius in the line core is about twice the optical radius. Transmission spectroscopy of the He I triplet line on GJ 3470 b has resulted in a few clear detections, but also some nondetections (Ninan et al. 2020; Pallé et al. 2020; Allart et al. 2023; Guilluy et al. 2024; Masson et al. 2024). The variability might be caused by temporal changes in the radiative (and possibly corpuscular) output of the host star; this is a scenario that would require validation by, for example, monitoring the star at X-ray wavelengths over several years. Unlike the cases of HAT-P-11 b and GJ 3470 b, all past searches of the He I triplet line on GJ 436 b have been unsuccessful (Nortmann et al. 2018; Guilluy et al. 2024; Masson et al. 2024). One proposed explanation is that the ratio He*/H* of helium to hydrogen nuclei on this planet is notably subsolar (Rumenskikh et al. 2023). Naturally, the idea prompts further questions regarding the fate of the helium accreted during planet formation. Alternatively, it has been shown that the line weakness is partly explained by accepting that the host star emits in the XUV to a lesser extent than what has been assumed in early models (García Muñoz 2025; Sanz-Forcada et al. 2025). Disequilibrium chemistry in the atmosphere involving vibrationally excited H2 offers an additional viable explanation.

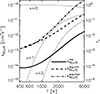

In this work, we simulated the escaping atmospheres of the three warm exo-Neptunes with our own model (García Muñoz 2025), generally assuming a solar He*/H*. Each of the planets receives a notably different amount of XUV radiation (Table B.1), with GJ 3470 b and GJ 436 b receiving about 22% and 2.3% of the incident XUV flux on HAT-P-11 b. The simulations show (Fig. 1, top) that the transition from H2 (dominant hydrogen form in the deep atmospheric layers) into H becomes nearly complete at r/Rp ∼ 1.3 for HAT-P-11; meanwhile, H2 survives to much farther distances on GJ 3470 b and even farther on GJ 436 b. Similar behaviors have been described by past models (Loyd et al. 2017; Ben-Jaffel et al. 2022; García Muñoz 2025), indicating that the stronger the incident XUV flux, the deeper the H2-to-H transition occurs. The transformation is mostly driven by ion-neutral chemical reactions, ultimately connected to photoionization and by H2 thermal dissociation where temperatures are high. Direct photodissociation of H2 into neutral fragments typically contributes to the H2-to-H transition to a small extent.

|

Fig. 1. Profiles of temperature and neutral densities (top), ion densities (middle), and the He(23S) metastable state density (bottom) for the three warm exo-Neptunes. Solid, dotted, dashed, and dotted-dashed curves refer to calculations based on kR2, v = 0, kR2, LTEthe, kR2, LTEexp, min, and kR2, LTEexp, max, respectively. Gray boxes in the bottom panel show the range of opaque radii calculated here (Table 1). |

In our original model, the removal of the precursor ion He+ in the layers probed by transmission spectroscopy of the He I triplet line is controlled by reaction R1. That model implicitly assumes that H2 is in the vibrational ground state and that the rate coefficient for reaction R2: He+ + H2(v) → He + H+ + H (v is the quantum number; exothermic by 6.5 eV) takes the value kR2, v = 0 = 3 × 10−14 cm3 s−1 measured in the laboratory at low temperature (Schauer et al. 1989) and recommended in astrochemistry applications (McElroy et al. 2013). This is five orders of magnitude slower than the collisional limit at which many other exothermic ion-neutral reactions proceed (Jones et al. 1986).

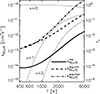

3. Disequilibrium chemistry driven by H2(v > 0)

Interestingly, there is both experimental and theoretical evidence that reaction R2 becomes fast when H2 is vibrationally excited and that it approaches the collisional limit for v ≥ 2 (Preston et al. 1978; Johnsen et al. 1980; Jones et al. 1980, 1986; Aguillon 1998; De Fazio et al. 2019). To our knowledge, the possibility that reaction R2 may control the He+ abundance in exoplanet atmospheres and in turn that of He(23S) has been overlooked thus far. Related ideas are, however, well established in the modelling of photodissociation regions and protoplanetary disks (Agúndez et al. 2010; Goicoechea & Roncero 2022). We compiled the available data on the v-resolved rate coefficients for reaction R2 (Appendix B) and formed thermal rate coefficients kR2, LTE under three scenarios motivated by the origin and uncertainties of the chemical data (and satisfying kR2, LTEthe < kR2, LTEexp, min ≤ kR2, LTEexp, max). Here, kR2, LTE exceeds kR2, v = 0 by up to four orders of magnitude in the conditions predicted for the three warm exo-Neptunes (Fig. B.1). Forseeably, reaction R2 will take over R1 as a sink for He+, where the [e−]/[H2] density ratio is small and the temperatures are high.

We repeated the simulations of the escaping atmospheres using the new kR2, LTE. For the three warm exo-Neptunes, the H2, H, and He densities change negligibly (Fig. 1, top). In contrast, the vibrationally enhanced rates for reaction R2 result in large drops in the He+ densities there where H2 remains undissociated (Fig. 1, middle). This occurs simultaneously with the charge transfer from He+ to H+ through reaction R2, and from H+ to H3+ through H+ + H2 → H2+ + H and H2+ + H2 → H3+ + H. Reduced densities of the precursor ion He+ lead to reduced densities of the He(23S) metastable state (Fig. 1, bottom). The effect is the largest for GJ 3470 b and GJ 436 b. The reason can be traced to the overlap on these planets of the layer where H2 remains undissociated and the layer where He+ remains abundant. Our simulations reveal the importance of the H2-to-H transition as a factor controlling the He(23S) density. The H2 survival to far distances on both GJ 3470 b and GJ 436 b opens up the possibility (unexplored here) that the H2 vibrationally excited states could be populated by stellar photoexcitation or by collisions with thermal electrons and become detectable in absorption in the Werner and Lyman bands at far-UV (FUV) wavelengths (Morgan et al. 2022).

Transmission spectroscopy is sensitive to the outermost atmospheric layers. We generated spectra of the He I triplet line based on the above simulations and extracted from each spectrum two transmission depth indicators (the excess absorption and the planet’s opaque radius, both specified at the line core (Guilluy et al. 2024; Masson et al. 2024, Table 1). For HAT-P-11 b, the transmission depths depend weakly on the rate coefficient for reaction R2 and are consistent with the measurements. As expected, the effect of the vibrationally enhanced reaction R2 on the transmission depths is significant for GJ 3470 b and GJ 436 b. The simulations adopting the thermal rate coefficients bring the transmission depths in closer agreement with the occasional detections on GJ 3470 b and the systematic nondetections on GJ 436 b. These simulations confirm that the He(23S) density on these planets is significantly affected by disequilibrium chemistry driven by vibrationally excited H2 through reaction R2.

Transmission depths, past measurements, and our calculations.

For the standard XUV flux of 278 erg cm−2 s−1 incident on GJ 436 b (Table B.1), the most recent upper limit on the excess absorption in the He I triplet line (0.3% (Masson et al. 2024); Table 1) is explained by He*/H* < 0.06, < 0.08, < 0.10, or < 0.12, if kR2, v = 0, kR2, LTEthe, kR2, LTEexp, min, or kR2, LTEexp, max, are adopted in the model, respectively. Clearly, the choice of the rate coefficient for reaction R2 limits the information that can potentially be inferred from He I triplet line measurements. New determinations (experimental or theoretical) of the rate coefficient for reaction R2 over a broad range of temperatures are needed.

4. Discussion and outlook

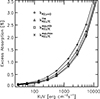

Conceivably, the He I triplet line might be used to assess whether an atmosphere is H2-He-dominated and, therefore, to help determine whether it is primordial or, alternatively, metal-rich and secondary. This notion is appealing, especially in its application to small exoplanets, for which IR molecular spectroscopy is challenging; however, we must also take into account that the large spatial scales associated with the escaping atmosphere produce detectable atomic signatures (García Muñoz et al. 2020, 2021; Ahrer et al. 2025). Without attempting to explore the full range of possibilities here, we simulated the atmosphere of a virtual sub-Neptune (Rp ∼ 2.2 R⊕; same bulk density as GJ 436 b, about half its gravity) orbiting GJ 436 at the same distance as GJ 436 b. The calculations (Fig. A.1) show that the He I triplet line is notably weaker than for GJ 436 b and that H2 remains undissociated to farther distances. The H2 survival to high altitudes is very detrimental to the strength of the He I triplet line, for which we obtain excess absorptions between 0.08% (for kR2, v = 0) and 0.03% (for kR2, LTEexp, max). On the positive side, the H2 survival suggests that vibrationally excited H2 might become detectable at FUV wavelengths. Overall, the large drop in the predicted He I triplet line strength when going from kR2, v = 0 to kR2, LTEexp, max cautions against simplified interpretations, in which the absence of He I triplet line absorption might be taken as evidence against a H2-He-dominated atmosphere.

The atmospheres of warm exo-Neptunes are fundamentally different to those of hotter or heavier exoplanets (e.g., hot Jupiters, for which there are many He I triplet line detections). On the latter, the H2-to-H transition generally occurs deep in the atmosphere, which makes reaction R2 ineffective at controlling the line strength. In contrast, our work shows that the H2 survival to far distances on small exoplanets significantly affects the He I triplet line that is often utilized as a tracer of atmospheric escape. The continuing discovery and characterization of warm exo-Neptunes will provide additional opportunities to test these ideas, especially if there is a concerted effort to detect the H I Lyman-α and He I triplet lines on them and to constrain their host stars’ high-energy emission. Our work reveals the importance of chemistry mediated through the vibrational states of molecules and the need to take such effects into account in future studies.

Acknowledgments

DDF acknowledges CINECA (ISCRA initiative) for availability of high performance computing resources and support.

References

- Aguillon, F. 1998, J. Chem. Phys., 109, 560 [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez, M., Goicoechea, J. R., Cernicharo, J., Faure, A., & Roueff, E. 2010, ApJ, 713, 662 [Google Scholar]

- Ahrer, E.-M., Radica, M., Piaulet-Ghorayeb, C., et al. 2025, ApJ, 985, L10 [Google Scholar]

- Allart, R., Bourrier, V., Lovis, C., et al. 2018, Science, 362, 1384 [Google Scholar]

- Allart, R., Lemée-Joliecoeur, P. B., Jaziri, A. Y., et al. 2023, A&A, 677, A164 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud, M., & Rothenflug, R. 1985, A&AS, 60, 425 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Basilicata, M., Giacobbe, P., Bonomo, A. S., et al. 2024, A&A, 686, A127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bean, J. L., Raymond, S. N., & Owen, J. E. 2021, J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 126, e06639 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty, T. G., Welbanks, L., Schlawin, E., et al. 2024, ApJ, 970, L10 [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Jaffel, L., Ballester, G. E., García Muñoz, A., et al. 2022, Nat. Astron., 6, 141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Benneke, B., Knutson, H. A., Lothringer, J., et al. 2019, Nat. Astron., 3, 813 [Google Scholar]

- Bourrier, V., Lecavelier, A., Ehrenreich, D., et al. 2018, A&A, 620, A147 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chachan, Y., Knutson, H. A., Gao, P., et al. 2019, AJ, 158, 244 [Google Scholar]

- Czesla, S., Lampón, M., Sanz-Forcada, J., et al. 2022, A&A, 657, A6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- De Fazio, D., Aguado, A., & Petrongolo, C. 2019, Front. Chem., 7, 249 [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, L. A., Vidotto, A. A., Vissapragada, S., et al. 2022, A&A, 659, A62 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich, D., Bourrier, V., Wheatley, P. J., et al. 2015, Nature, 522, 459 [Google Scholar]

- Fantz, U., & Wünderlich, D. 2006, At. Data Nucl. Data Tables, 92, 853 [Google Scholar]

- Fossati, L., Haswell, C. A., Froning, C. S., et al. 2010, ApJ, 714, L222 [Google Scholar]

- Fossati, L., Guilluy, G., Shaikhislamov, I. F., et al. 2022, A&A, 658, A136 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati, L., Pillitteri, I., Shaikhislamov, I. F., et al. 2023, A&A, 673, A37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- France, K., Loyd, R. O. P., Youngblood, A., et al. 2016, ApJ, 820, 89 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- García Muñoz, A. 2025, A&A, 698, A199 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- García Muñoz, A., & Bataille, E. 2024, ACS Earth Space Chem., 8, 2652 [Google Scholar]

- García Muñoz, A., Youngblood, A., Fossati, L., et al. 2020, ApJ, 888, L21 [Google Scholar]

- García Muñoz, A., Fossati, L., Youngblood, A., et al. 2021, ApJ, 907, L36 [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea, J. R., & Roncero, O. 2022, A&A, 664, A190 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Grasser, N., Snellen, I. A. G., Landman, R., Picos, D. G., & Gandhi, S. 2024, A&A, 688, A191 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Guilluy, G., D’Arpa, M. C., Bonomo, A. S., et al. 2024, A&A, 686, A83 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ikoma, M., & Kobayashi, H. 2025, ARA&A, 63, 217 [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, R., Chen, A., & Biondi, M. A. 1980, J. Chem. Phys., 72, 3085 [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E. G., Wu, R. L. C., Hughes, B. M., Tiernan, T. O., & Hopper, D. G. 1980, J. Chem. Phys., 73, 5631 [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. E., Barlow, S. E., Ellison, G. B., & Ferguson, E. E. 1986, Chem. Phys. Lett., 130, 218 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, D., Bean, J. L., Oklopčić, A., et al. 2020, AJ, 160, 258 [Google Scholar]

- Kingdon, J. B., & Ferland, G. J. 1996, ApJS, 106, 205 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson, H. A., Benneke, B., Deming, D., & Homeier, D. 2014, Nature, 505, 66 [Google Scholar]

- Kosiarek, M. R., Crossfield, I. J., Hardegree-Ullman, K., et al. 2019, AJ, 157, 97 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kulow, J. R., France, K., Linsky, J., & Loyd, R. O. P. 2014, ApJ, 786, 132 [Google Scholar]

- Lampón, M., López-Puertas, M., Sanz-Forcada, J., et al. 2023, A&A, 673, A140 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Loyd, R. O. P., Koskinen, T. T., France, K., Schneider, C., & Redfield, S. 2017, ApJ, 834, L17 [Google Scholar]

- Loyd, R. O. P., Schreyer, E., Owen, J. E., et al. 2025, Nature, 638, 636 [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, M., Bean, J. L., Oklopčić, A., et al. 2018, ApJ, 868, L34 [Google Scholar]

- Masson, A., Vinatier, S., Bézard, B., et al. 2024, A&A, 688, A179 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy, D., Walsh, C., Markwick, A. J., et al. 2013, A&A, 550, A36 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, A., Cauley, P. W., France, K., Youngblood, A., & Koskinen, T. T. 2022, RNAAS, 6, 141 [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee, S., Schlawin, E., Bell, T. J., et al. 2025, ApJ, 982, L39 [Google Scholar]

- Nahar, S. N. 2010, New Astron., 15, 417 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nahar, S. 2020, Atoms, 8, 68 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nettelmann, N., Kramm, U., Redmer, R., & Neuhäuser, R. 2010, A&A, 523, A26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ninan, J. P., Stefansson, G., Mahadevan, S., et al. 2020, ApJ, 894, 97 [Google Scholar]

- Nortmann, L., Pallé, E., Salz, M., et al. 2018, Science, 362, 1388 [Google Scholar]

- Oklopčić, A. 2019, ApJ, 881, 133 [Google Scholar]

- Oklopčić, A., & Hirata, C. M. 2018, ApJ, 855, L11 [Google Scholar]

- Orell-Miquel, J., Murgas, F., Pallé, E., et al. 2024, A&A, 689, A179 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Otegi, J. F., Bouchy, F., & Helled, R. 2020, A&A, 634, A43 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pallé, E., Nortmann, L., Casasayas-Barris, N., et al. 2020, A&A, 638, A61 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock, S., Barman, T., Shkolnik, E. L., et al. 2019, ApJ, 886, 77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preston, R. K., Thompson, D., & McLaughlin, D. 1978, J. Chem. Phys., 68, 13 [Google Scholar]

- Rumenskikh, M. S., Khodachenko, M. L., Shaikhislamov, I. F., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 526, 4120 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Forcada, J., López-Puertas, M., Lampón, M., et al. 2025, A&A, 693, A285 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer, M., Jefferts, S., Barlow, S., & Dunn, G. 1989, J. Chem. Phys., 91, 4593 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spake, J. J., Sing, D. K., Evans, T. M., et al. 2018, Nature, 557, 68 [Google Scholar]

- Stecher, T. P., & Williams, D. A. 1967, ApJ, 149, L29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Q., Wang, S. X., Welbanks, L., Teske, J., & Buchner, J. 2024, AJ, 167, 167 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, J., Christie, D., Arras, P., & Johnson, R. 2016, MNRAS, 458, 3880 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Venturini, J., Guilera, O. M., Haldemann, J., Ronco, M. P., & Mordasini, C. 2020, A&A, 643, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Madjar, A., Lecavelier, A., Désert, J. M., et al. 2003, Nature, 422, 143 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal-Madjar, A., Désert, J. M., Lecavelier, A., et al. 2004, ApJ, 604, L69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vissapragada, S., Knutson, H., Greklek-McKeon, M., et al. 2022, AJ, 164, 234 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- West, B. W., Lane, N. F., & Cohen, J. S. 1982, Phys. Rev. A, 26, 3164 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D. J., Froning, C. S., Duvvuri, G. M., et al. 2025, ApJ, 978, 85 [Google Scholar]

- Yan, F., & Henning, T. 2018, Nat. Astron., 2, 714 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M., Knutson, H. A., Dai, F., et al. 2023, ApJ, 165, 62 [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Further discussion

To explore the broader implications of the vibrationally enhanced reaction R2, we simulated GJ 436 b-like planets (and atmospheres of solar He*/H*) that receive XUV fluxes in the range from 30 to 20,000 erg cm−2s−1. For reference the incident XUV flux at Earth is of a few erg cm−2s−1. In practice, we scaled the stellar XUV spectra without modifying the incident fluxes at longer wavelengths. The exercise provides also insight into GJ 436 b at epochs when its host star might have experienced a different activity or the exoplanet might have been on a different orbit. The vibrationally enhanced reaction R2 has a major relative impact on the transmission depth for low-to-moderate XUV fluxes, but the impact is minor for high XUV fluxes (Fig. A.2). The reason is that high XUV fluxes lead to atmospheres in which the H2-to-H transition occurs deeper, making the removal of the precursor ion He+ through reaction R2 progressively marginal. Based on these calculations, we speculate that a time-varying radiation environment experienced by the planet due to, for example, an activity cycle, rotational modulation or enhanced flare activity of the host star might be the causes of the temporal variability on GJ 3470 b. A multi-year transit campaign with contemporaneous X-ray and FUV observations to track the XUV output at the same time as tracking the He I triplet line on this warm exo-Neptune will help test these scenarios that, if proven correct, might serve as an indirect method for monitoring the high-energy radiative output of this and other host stars.

|

Fig. A.1. Same as Fig. 1, but for the virtual sub-Neptune motivated by GJ 436 b described in the text. The He I triplet line is one of the few atmospheric features detectable on sub-Neptunes with current technology (as in the case of GJ 3090 b, Ahrer et al. 2025). The limited set of simulations presented in this figure confirm that H2 is likely to survive to far distances on them, which has a significant effect on the He I triplet line strength. |

|

Fig. A.2. Excess absorption predicted for a GJ 436 b-like exoplanet under a range of XUV fluxes. On its current orbit, GJ 436 b receives a XUV flux of about 278 erg cm−2s−1 (Table B.1). Simulations based on the various rate coefficients for reaction R2. For small XUV fluxes, the EA varies by up to a factor of 2 depending on the rate coefficient for reaction R2 that is adopted. For strong XUV fluxes, the choice of reaction rate coefficient is, in relative terms, weaker. This figure complements the EA quoted in Table 1 for HAT-P-11 b, GJ 3470 b, and GJ 436 b. |

Appendix B: Methods

B.1. Rate coefficient for reaction R2

We formed thermal or local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) rate coefficients for reaction R2,  , from the information available on the v-resolved rate coefficients, v referring to the vibrational quantum number in H2(v). LTE is used to mean that the H2(v) population is assumed to be in local thermodynamic equilibrium, described by a truncated Boltzmann distribution of states v≤2 at the gas kinetic temperature. We calculated the transition probabilities Av′v″ for spontaneous emission v′ = 1–2→v″< v′ in H2, finding they are ≲10−6 s−1 and therefore much smaller than the deexcitation rates for collisions with H2 or H at the pressures of interest, which gives evidence that the relative H2(v≤2) populations are dictated by collisions and thus thermalized. At the usual temperatures of exoplanet atmospheres, the H2(v> 2) population is negligible.

, from the information available on the v-resolved rate coefficients, v referring to the vibrational quantum number in H2(v). LTE is used to mean that the H2(v) population is assumed to be in local thermodynamic equilibrium, described by a truncated Boltzmann distribution of states v≤2 at the gas kinetic temperature. We calculated the transition probabilities Av′v″ for spontaneous emission v′ = 1–2→v″< v′ in H2, finding they are ≲10−6 s−1 and therefore much smaller than the deexcitation rates for collisions with H2 or H at the pressures of interest, which gives evidence that the relative H2(v≤2) populations are dictated by collisions and thus thermalized. At the usual temperatures of exoplanet atmospheres, the H2(v> 2) population is negligible.

We calculate the LTE rate coefficient as

where fv=exp( − Ev/kT)/Z is the H2(v) relative abundance, and kR2, v is the v-resolved rate coefficient for collisions of He+ with H2(v). Z=∑v ≤ 2exp( − Ev/kT) is the truncated partition function. The energies Ev are from a compilation (Fantz & Wünderlich 2006); k and T are Boltzmann’s constant and temperature, respectively. Our calculated fv are consistent with the relative abundances calculated taking also into account the rotational structure of the molecule.

We collected the information on the kR2, v from a variety of sources that include theoretical calculations and laboratory experiments. Although there is general consensus in their qualitative behaviors, there remain discrepancies in their quantitative values. To account for these uncertainties and explore their implications, we formed three LTE rate coefficients, one of them based on theoretical calculations, which we term  , and two of them based on experimental constraints, which we term

, and two of them based on experimental constraints, which we term  and

and  . Ideally, future work by chemists will solve these discrepancies.

. Ideally, future work by chemists will solve these discrepancies.

B.2. Theory-based rate coefficient

We adopted the kR2, v = 0the and kR2, v = 1the (with both v = 0 and v = 1 in their rotational ground states) obtained in quantum dynamical calculations up to 2,000 K (De Fazio et al. 2019), and assumed they become temperature-independent and equal to 1.30×10−14 and 1.39×10−12 cm3s−1, respectively, for T> 2,000 K. Importantly, test calculations suggest that the H2(v = 0) reactivity is very sensitive to rotational excitation, which might enhance the efficiency of reaction R2 as the temperature increases well above the values adopted here, which should therefore be seen as lower limits. We assumed kR2, v = 2the = 10×kR2, v = 1the based on available semi-classical cross-section calculations at collision energies ∼2 eV (Aguillon 1998). Future rate coefficient calculations should include collisions at energies below 1 eV with H2(v≤2) in a broad range of rotational states.

|

Fig. B.1. Thermal (LTE) rate coefficients for reaction R2 implemented in our simulations (see text for details). Also, relative abundances fv for H2(v≤2) are shown as the dotted lines. The experiment-based rate coefficients are consistent with the measurements at temperatures between 400 and 700 K (Johnsen et al. 1980). For reference, the low-temperature measurements (Schauer et al. 1989) recommended for astrochemical applications (McElroy et al. 2013) are ∼3×10−14 cm3s−1. |

The parameterization:

reproduces the theory-based LTE rate coefficient to within 15% from 200 to 10,000 K.

B.3. Experiment-based rate coefficients

We adopted the available experimental measurements between 400 and 700 K for the collisions of He+ and H2 (Johnsen et al. 1980), which we assumed to represent the combination of fv = 0kR2, v = 0exp + fv = 1kR2, v = 1exp. The measurements are well described by a power law of the type ∝Tm with m = 1.4309776, and we used this law to represent the contribution of collisions with H2(v≤1) over the full range of temperatures. To account for the contribution of collisions with H2(v = 2), we added fv = 2kR2, v = 2exp, where kR2, v = 2exp was borrowed from published (Jones et al. 1986) lower (kR2, v = 2exp, min = 1.8×10−10 cm3s−1) and upper (kR2, v = 2exp, max= 1.8×10−9 cm3s−1) estimates. We formed  and

and  by using kR2, v = 2exp, min and kR2, v = 2exp, max respectively. The parameterizations,

by using kR2, v = 2exp, min and kR2, v = 2exp, max respectively. The parameterizations,

reproduce the experiment-based LTE rate coefficients to within 30% from 400 to 10,000 K.

Figure B.2 shows the three  as a function of temperature. They differ by up to ×100 at the highest temperature in the plot. The differences call for new constraints either from quantum calculations or experiments. This said, both theory and experiments have given substantial evidence (Preston et al. 1978; Johnsen et al. 1980; Jones et al. 1986; Schauer et al. 1989; Aguillon 1998; De Fazio et al. 2019) that kR2, v = 0≪kR2, v = 1≪kR2, v = 2 and this translates into LTE rate coefficients for reaction R2 that vary by 3-4 orders of magnitude between ambient temperature and a few thousand Kelvin. Although exothermic by at least 6.5 eV, reaction R2 exhibits an internal barrier (Preston et al. 1978) that makes it unusually slow at ambient temperature. Vibrational excitation facilitates the tunneling through the barrier and enhances its reactivity.

as a function of temperature. They differ by up to ×100 at the highest temperature in the plot. The differences call for new constraints either from quantum calculations or experiments. This said, both theory and experiments have given substantial evidence (Preston et al. 1978; Johnsen et al. 1980; Jones et al. 1986; Schauer et al. 1989; Aguillon 1998; De Fazio et al. 2019) that kR2, v = 0≪kR2, v = 1≪kR2, v = 2 and this translates into LTE rate coefficients for reaction R2 that vary by 3-4 orders of magnitude between ambient temperature and a few thousand Kelvin. Although exothermic by at least 6.5 eV, reaction R2 exhibits an internal barrier (Preston et al. 1978) that makes it unusually slow at ambient temperature. Vibrational excitation facilitates the tunneling through the barrier and enhances its reactivity.

|

Fig. B.2. LTE rate coefficients for reaction R2. Top: theory-based value. Middle and Bottom: Experiment-based values; Johnsen et al. (1980) measurements are shown for reference. |

B.4. Stellar SEDs

Hydrodynamic escape is driven by stellar photons incident on the atmosphere that transfer some of their energy to the internal modes of the gas atoms and molecules. The heated atmosphere expands and accelerates into space, setting off a bulk outflow. Our simulations show that H2, H, He, and He+ are relatively abundant at some altitude and thus prime candidates to drive the gas acceleration. The longest wavelength at which these species engage in continuum absorption leading to photofragmentation is ∼1,200 Å, the threshold for the first step in the sequence H2(X, v)+hν→H2(B, C)→H+H (Stecher & Williams 1967). In truth, the threshold depends on the details of the vibrational population of the electronic ground state H2(X, v) and thus on temperature. If the description of the stellar spectral energy distribution (SED) at λ≲1,200 Å is key for the outflow modelling, the helium modelling is sensitive to the wavelengths that enable He+hν(λ< 504Å)→He++e−, He++hν(λ< 228Å)→He2++e− and He(23S)+hν(λ< 2,600Å)→He++e−, as photoionization contributes to the chemical balance of the He+ precursor and the He(23S) metastable.

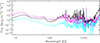

The high-energy spectra of the host stars of interest in our study have been studied multiple times (France et al. 2016; Peacock et al. 2019; Sanz-Forcada et al. 2025; Wilson et al. 2025). We adopted the HAT-P-11, GJ 3470 and GJ 436 SEDs at λ≲1,200 Å from the X-Exoplanets database (Sanz-Forcada et al. 2025). For the longer wavelengths, we utilized the best available SEDs obtained through the Mega-MUSCLES project (France et al. 2016). Specifically, for HAT-P-11 (stellar type K4, 29 days of rotation period) we adopted data for Epsilon Indi (K4-5, 35 days), for GJ 3470 (M1.5, 21 days) we adopted data for GJ 649 (M1, 23 days), and for GJ 436 (M3.5 V) we adopted the corresponding SED reported in the MUSCLES database. Assessing the reliability of the SEDs is challenging, partly because the available direct information is limited and partly because the stellar radiative output is itself variable over multiple timescales. Our uniform treatment of the host stars’ spectra aims to minimize potential biases in the results introduced by arbitrarily combining various stellar spectrum sources. Figure B.3 shows the stellar fluxes received by the planets at their orbital positions and Table B.1 summarizes some integrated quantities.

|

Fig. B.3. Stellar fluxes incident on the planets, degraded to low resolution for clarity of presentation. Black: HAT-P-11 b; Magenta: GJ 3470 b; Cyan: GJ 436 b. |

Some integrated properties of the adopted stellar SED at the planet orbits.

B.5. Hydrodynamic modelling

The calculations were performed with a numerical model that solves simultaneously the mass, momentum and energy conservation equations of a gas in a one-dimensional spherical-shell atmosphere. It includes about 210 chemical-collisional-radiative processes and 20 species of hydrogen and helium plus thermal electrons. The list of species does not include heavier elements (metals). We will explore the significance of metal-based chemistry in the future. The effect of non-thermal electrons produced by ionizing radiation on the chemistry and the radiative transfer is considered self-consistently (García Muñoz & Bataille 2024) without introducing ad hoc efficiencies. The model is well suited for investigating the transition from a molecular, H2-dominated gas to an atomic, mostly ionized plasma.

The original implementation (García Muñoz 2025) is extended to include reaction R2 for an LTE population of H2. We additionally extended the helium chemistry network and the corresponding radiative transfer by adding the double-charge ion He2+ (energy E(He2+)−E(He+) = 54.4 eV; He+ remains the only form of the single-charge ion and is assumed to represent the ground electronic state), and the radiative He++hν↔He2++e− and charge-exchange He2++H→He++H+ processes. Both the photoionization cross sections from the electronic ground state of He+ and the total radiative recombination rate coefficients are borrowed from the NORAD database (Nahar 2010, 2020). For reference, Table B.2 summarizes the radiative recombination rate coefficients at a few temperatures. He+ photoionization conceivably contributes to the gas opacity at high altitudes and modifies the ion abundance there. Our calculations show however that this affects negligibly the atmosphere where the He I triplet line is formed. We calculated the charge-exchange rate coefficient directly from the cross sections (West et al. 1982). Its value is well approximated from 200 to 10,000 K by the temperature-independent value 1.70×10−13 cm3s−1. This is consistent with the value recommended in a compilation (Arnaud & Rothenflug 1985) but more than an order of magnitude larger than the value recommended in another compilation (Kingdon & Ferland 1996).

The quoted mass loss rates are calculated from ṁ = 4πρur2, where ρ is the volume density of the gas, u is its bulk velocity and r is the radial distance to the center of the planet. We solve the gas flow along the substellar line, without attenuating the incident stellar flux to take into account slanted irradiation near the terminators. This may artificially boost the mass loss rate over its true value by a case-dependent factor of ∼2. The actual value can only be determined by means of multi-dimensional calculations, which are beyond the scope of this work.

Rate coefficient for He2++e−→He++hν.

B.6. Spectral modelling

We calculated the transmission depths using a previously presented methodology (García Muñoz 2025). The calculation takes into account the Doppler shift introduced by the gas escaping towards and away from the observer in the assumed spherical shell geometry. Figure B.4 summarizes the transmission spectra for the simulations presented in Fig. 1.

|

Fig. B.4. Synthetic spectra based on the atmospheric models of Fig. 1 (black: same pattern code) and measured spectra and uncertainties (red: Masson et al. 2024). |

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Profiles of temperature and neutral densities (top), ion densities (middle), and the He(23S) metastable state density (bottom) for the three warm exo-Neptunes. Solid, dotted, dashed, and dotted-dashed curves refer to calculations based on kR2, v = 0, kR2, LTEthe, kR2, LTEexp, min, and kR2, LTEexp, max, respectively. Gray boxes in the bottom panel show the range of opaque radii calculated here (Table 1). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.1. Same as Fig. 1, but for the virtual sub-Neptune motivated by GJ 436 b described in the text. The He I triplet line is one of the few atmospheric features detectable on sub-Neptunes with current technology (as in the case of GJ 3090 b, Ahrer et al. 2025). The limited set of simulations presented in this figure confirm that H2 is likely to survive to far distances on them, which has a significant effect on the He I triplet line strength. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.2. Excess absorption predicted for a GJ 436 b-like exoplanet under a range of XUV fluxes. On its current orbit, GJ 436 b receives a XUV flux of about 278 erg cm−2s−1 (Table B.1). Simulations based on the various rate coefficients for reaction R2. For small XUV fluxes, the EA varies by up to a factor of 2 depending on the rate coefficient for reaction R2 that is adopted. For strong XUV fluxes, the choice of reaction rate coefficient is, in relative terms, weaker. This figure complements the EA quoted in Table 1 for HAT-P-11 b, GJ 3470 b, and GJ 436 b. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.1. Thermal (LTE) rate coefficients for reaction R2 implemented in our simulations (see text for details). Also, relative abundances fv for H2(v≤2) are shown as the dotted lines. The experiment-based rate coefficients are consistent with the measurements at temperatures between 400 and 700 K (Johnsen et al. 1980). For reference, the low-temperature measurements (Schauer et al. 1989) recommended for astrochemical applications (McElroy et al. 2013) are ∼3×10−14 cm3s−1. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.2. LTE rate coefficients for reaction R2. Top: theory-based value. Middle and Bottom: Experiment-based values; Johnsen et al. (1980) measurements are shown for reference. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.3. Stellar fluxes incident on the planets, degraded to low resolution for clarity of presentation. Black: HAT-P-11 b; Magenta: GJ 3470 b; Cyan: GJ 436 b. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.4. Synthetic spectra based on the atmospheric models of Fig. 1 (black: same pattern code) and measured spectra and uncertainties (red: Masson et al. 2024). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.