| Issue |

A&A

Volume 705, January 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A121 | |

| Number of page(s) | 12 | |

| Section | Planets, planetary systems, and small bodies | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555785 | |

| Published online | 14 January 2026 | |

Two faces of L-type asteroids

Evidence from UV-VisNIR spectra and CO/CV chondrites

1

Université Marie et Louis Pasteur,

CNRS, Institut UTINAM (UMR 6213), équipe Astro,

25000

Besançon,

France

2

European Southern Observatory,

Alonso de Córdova 3107,

1900

Casilla Vitacura, Santiago,

Chile

3

European Space Agencay, NEO Coordination Centre,

Largo Galileo Galilei, 1,

00044

Frascati (RM),

Italy

4

Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, Université Paris-Saclay,

CNRS,

91405

Orsay,

France

5

Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble,

Université Grenoble Alpes,

38000

Grenoble,

France

6

Université Côte d’Azur, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur,

CNRS,

Laboratoire Lagrange,

France

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

2

June

2025

Accepted:

31

October

2025

Context. L-types are a rare class of asteroids whose spectra indicate similarities with CO and CV chondrites, suggesting high abundances of refractory inclusions, particularly with respect to the calcium-aluminium-rich inclusion. This implies that their parent bodies were among the earliest chondrites to form.

Aims. We aim to identify L-types within selected asteroid families and to provide the first UV-VisNIR spectral characterisation of asteroids in this class. We further assess the spectral variability among L-types and evaluate the suitability of ESA Gaia UV-visible spectra for their identification.

Methods. We obtained VLT/X-shooter spectra of nine asteroids associated with L-type families. We classified them taxonomically using their UV-VisNIR spectra combined with the visual albedo and compared them to Gaia spectra and to ordinary, CO, and CV chondrites.

Results. Among the nine asteroids, we identified four L- and two M-types (Mahlke taxonomy), exhibiting diverse spectral features. Placing them into context of other L-types and known Barbarians using literature data, we find that L-types cluster into two groups based on spectra and albedo. One group depicts a deep 2 μm absorption and is denoted LL, while a second group shows a shallow or absent 2 μm feature and is denoted LM. We find a similar bimodality among CO and CV chondrites. Their steep UV-visible slopes and 1 μm features enable us to distinguish L- from S-types in Gaia’s spectral range.

Conclusions. The expanding census of L-types reveals a dispersed, possibly bimodal spectral distribution across multiple families, indicative of heterogeneity of the CO and oxidised CV chondrites parent bodies. Both the Aquitania and Brangäne family appear to come from such heterogeneous planetesimals. The Watsonia family is uniform and best represented by reduced CV chondrites. On the other hand, L-types with profound 2 μm absorptions such as (234) Barbara appear to be unsampled in the meteorite collection. Upcoming Gaia DR4 spectra and the ongoing SPHEREx mission will offer deeper insights into the distribution and mineralogical properties of this enigmatic class.

Key words: meteorites, meteors, meteoroids / minor planets, asteroids: general

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

L-types are a rare and compelling class of asteroids distributed throughout the main belt (DeMeo & Carry 2014). Their visible reflectance spectra show steep, positive (‘red‘) slopes that flatten into neutral slopes at near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths, accompanied by a broad absorption feature near 2 μm (Burbine et al. 1992; DeMeo et al. 2009; Mahlke et al. 2022). This 2 μm band varies in depth among L-types, from prominent to almost absent. Additionally, some display a subtle 1 μm feature attributed to olivine (Mahlke et al. 2022). Currently, about 40 to 50 L-types have been identified, although most lack full visible-near-infrared (VisNIR) spectral coverage, making their classifications uncertain.

The 2 μm absorption has been linked to calcium-aluminium-rich inclusions (CAIs) (Burbine et al. 1992; Sunshine et al. 2008; Devogèle et al. 2018), the first solids to condense in the solar nebula and a reference point for solar system chronology (Amelin et al. 2002; Piralla et al. 2023). Overall, CAIs are rich in spinel (MgAl2O4), which can incorporate Fe2+ during parent body metamorphism, giving rise to absorptions near 2 μm (Cloutis et al. 2012b). L-type spectra show similarities to CAI-rich CO and CV chondrites (Burbine et al. 1992; Sunshine et al. 2008; Devogèle et al. 2018; Mahlke et al. 2023), which contain the highest abundances of refractory inclusions among carbonaceous meteorites (Scott & Krot 2014). Modelling results suggest that some L-types may contain 20 vol% to 40 vol% CAIs (Sunshine et al. 2008; Devogèle et al. 2018), exceeding the amounts found in CO and CV chondrites, while for others, spectral comparisons have identified analogues among CO chondrites and the oxidised Allende-like subclass of CV chondrites (CVOxA) (Mahlke et al. 2023). These associations underscore the potential of L-types to preserve information on material composition and transport in the early Solar System (Hellmann et al. 2023; Marschall & Morbidelli 2023).

The L-type class, defined based on VisNIR spectroscopy, appears closely related to the class of so-called ‘Barbarians’, defined on visible polarimetry and named after (234)Barbara (Cellino et al. 2006). These asteroids show anomalously large inversion angles in their polarimetric phase curves. At least 23 Barbarians have been identified (Cellino et al. 2014; Devogèle et al. 2018; Bendjoya et al. 2022). Similar large inversion angles are observed experimentally in CO and CV chondrites (Frattin et al. 2019), likely due to the high refractive index of spinel-bearing assemblages (Devogèle et al. 2018; Masiero et al. 2023). Thus, CAIs appear central to both the spectral properties of L-types and the polarimetric behaviour of Barbarians, suggesting the two may represent a single population.

However, the limited number of known L-types hinders robust conclusions about their distribution and composition in the Main Belt. Distinguishing L-types requires full VisNIR spectra, as they can be easily confused with S-types and other classes based on partial coverage. It is therefore crucial to expand the census of L-types both in terms of number of known objects and their spectral coverage.

Here, we present European Southern Observatory (ESO) VLT/X-shooter observations aimed at identifying new L-types and at characterising their mineralogy using the full ultraviolet (UV)-VisNIR coverage provided by X-shooter. These observations further serve to build a reference set for the identification of L-types using Gaia and SPHEREx. In Section 2, we describe the observations and spectral analysis methods. Section 3 presents taxonomic classifications and meteorite comparisons. In Section 4, we examine the spectral diversity among L-types and their associations to CO and CV chondrites. We present our conclusions in Section 5.

2 Methodology

In this section, we describe the target selection and observational campaign, reduction and taxonomic classification of the acquired spectra, comparison with meteorite spectra, and the sources of ancillary data for the following analysis. We opted for observations with ESO VLT/X-shooter as (1) the 8 m VLT telescope enables us to target relatively faint asteroids and (2) it provides simultaneous acquisition of the UV-VisNIR range (0.30 μm to 2.48 μm) (Vernet et al. 2011), offering comparability to Gaia and SPHEREx observations and reducing uncertainty in the spectral slope that arises when spectral segments are obtained at separate epochs.

2.1 Target selection

To identify suitable targets of observations, we first selected all family members of the five families known to host L-type asteroids: Aquitania, Brangäne, Henan, Tirela/Klumpkea, and Watsonia (Masiero & Cellino 2009; Brož et al. 2013; Cellino et al. 2014; Milani et al. 2014; Vinogradova 2019; Balossi et al. 2024). To reject possible interlopers, we required that the targets have albedos between 0.1 to 0.2 within errors and Gaia spectra displaying a moderate to steep slope in the visible and a possible drop-off towards 1 μm, following the L-type class definition of Mahlke et al. (2022). We further rejected all targets with existing NIR spectra in the literature, as we aimed to increase the number of spectrally characterised family members. Finally, we restricted the targets to those observable from ESO Paranal (IAU code 309) during the P113 semester with a visual magnitude V below 18, ensuring that observations including overheads can be carried out within one hour and facilitating the scheduling of observations at ESO. After applying these criteria on all 4895 members of the L-type families, we were left with 13 targets.

Observational conditions during target acquisition.

2.2 Observations with X-shooter

We obtained eight hours observation time during the P113 semester with X-shooter1. Rather than assigning fixed times, nightly observing schedules at ESO are flexible and rely on observing windows defined by the observers. For each target, we defined the observing window as the time span between the two dates on either side of peak brightness when the asteroid becomes 0.5 mag fainter in V, giving an observing window of approximately three to four weeks for each target. All asteroid observations were scheduled in concatenation with observations of solar analogues for calibration of the solar spectral component. Solar analogues were chosen from a compiled list of stars (Datson et al. 2014; Porto de Mello et al. 2014; Mittag et al. 2016) based on their angular separation to the asteroidal target to minimise the telescope slew time between the two observations. Solar analogue visibility and angular separation to the asteroid were computed using LTE’s Miriade Vision service2 (Carry & Berthier 2018). The X-shooter spectrometer slits were aligned with the parallactic angle during observations.

Observations were carried out between April and September 2024 by the ESO Paranal instrument operators in service mode. We observed nine of the thirteen possible targets, while the remaining four could not be scheduled. The observational circumstances are summarised in Table 1.

2.3 Data reduction

X-shooter observes with three instrumental arms to acquire the UV, visible, and NIR spectra simultaneously. These spectral segments are provided individually in flux-calibrated form by ESO. To produce the science-ready asteroidal spectra, we first applied the molecfit pipeline provided by ESO to each observed spectral segment, correcting for telluric absorption features and airmass differences (Smette et al. 2015). We then identified and removed outliers by applying a 2 σ clipping on each slope-removed spectral segment. In regions of strong telluric absorption, we applied stricter clipping limits, based on our visual impression of the spectra.

Next, we divided each segment by its respective solar analogue spectrum (refer to Table 1). This accounts for the solar component in the asteroidal spectra and decreases telluric absorption features, most notably between 1.3 μm to 1.5 μm and 1.75 μm to 2.0 μm. We then merged the three spectral segments by additively matching them in reflectance, using the mean reflectance values of the 100 bins closest to the endpoints at 0.55 μm and 1 μm. Next, we leveraged the high spectral resolution (R=5400 in UV arm for a slit width of 1′′; R=8900 in visible arm for a slit width of 0.9′′; R=5600 in NIR arm for a slit width of 0.9′′) of X-shooter by rebinning the spectral segments to widths of {2, 4, 8}nm, depending on our visual impression of the noise level present in the data. The rebinning increases the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) by factors between 2.5 and 10, depending on the spectral range and bin width. This spectral resolution is still much finer than the width of absorption features observed in asteroid spectra (typically tens of nm). Finally, we normalised all the spectra to unity at 0.55 μm. The final spectra are shown in Figure 1.

The required close match in airmass during observations of the asteroid and the solar analogue is not always feasible, resulting in some cases where low to significant telluric absorption features remain in the asteroidal spectra. For (1426) Riviera and (3682) Welther, we did not achieve a satisfactory correction for telluric absorption between ∼ 1.3 μm to 1.5 μm and ∼ 1.8 μm to 2.0 μm, and we chose to remove the range entirely and to instead interpolate the spectrum with a cubic spline fit in this narrow range, highlighted in grey in Figure 1. While the observation of multiple solar analogues per asteroid would improve the telluric correction and the overall reduction, this was not possible within the constraints of the observing time. This had a notable impact on the correction of the spectrum of (3682) Welther, where a typo during the observation preparation led to the observation of a non-solar-analogue star in concatenation with the asteroid. Instead, we used the solar analogue observed for (30379) Molaro to calibrate the spectrum of (3682) Welther. We selected this solar analogue based on (1) the visible reduction of the telluric features and (2) our minimisation of the difference in the slope of the reduced X-shooter spectrum and the existing spectrum of (3682) Welther acquired by the S3OS2 survey (Lazzaro et al. 2004). Thanks to this independent verification, we are confident that our spectrum of (3682) Welther remains reliable, despite the sub-optimal calibration.

|

Fig. 1 Asteroid spectra acquired with VLT/X-shooter (black line). We further show the Gaia DR3 spectrum of each asteroid (grey markers), having removed the first and last Gaia data point. For asteroids (1426) Riviera and (3682) Welther, we removed values that are strongly affected by telluric absorption features (shaded grey area) and interpolated the spectra in these regions. For (3682) Welther, we further show the spectrum acquired by the S3OS2 survey (blue line) that we used to choose the alternative solar analogue spectrum (refer to text for details). |

2.4 Literature data

We used different types of asteroid data from the literature to complement the X-shooter observations. This included reflectance spectra from the third data release (DR3) of Gaia (Gaia Collaboration 2023) and other surveys, albedos, family associations (refer to Table 2), and polarimetric classifications (see Table A.1). We obtained the reflectance spectra from the literature using classy3. We provide references for these observations in Appendix A. All remaining properties were retrieved from the Solar system Open Database Network (SsODNet) using rocks (Berthier et al. 2023)4. The asteroid albedos are computed by SsODNet using the latest estimates of the absolute magnitude and the most reliable diameter estimate (mostly from the WISE/NEOWISE survey, Masiero et al. 2021; Berthier et al. 2023).

Properties of X-shooter targets.

2.5 Taxonomic classification

The large wavelength coverage of X-shooter allows us to classify the spectra in three taxonomic schemes:

Tholen (1984), hereafter T84, classifies asteroids based on UV-visible spectrophotometry using seven bands from 0.34 μm to 1.04 μm. The albedo was accounted for in a secondary step to separate E-, M-, and P-types as well as Band C-types. The scheme requires complete coverage of the wavelength range for classification.

DeMeo et al. (2009), hereafter DM09, a VisNIR classification scheme defined from 0.45 μm to 2.45 μm. The classification does not consider albedo and requires complete coverage of the VisNIR range.

Mahlke et al. (2022), hereafter M22, a classification scheme using VisNIR observations from 0.45 μm to 2.45 μm and the albedo. It supports the classification of partial observations (e.g. visible-only spectra without albedo) and provides probabilistic classifications. Compared to DM09, the classification by M22 is based on an order of magnitude more spectra.

We used classy to classify spectra in all three taxonomic schemes (Mahlke 2024). classy applies principal component analysis (PCA) and decision trees following T84 and DM09 to arrive at the respective classifications, as opposed to the more common but less accurate χ2 matching with the class template spectra.

2.6 Meteorite analogues

To compare the X-shooter spectra to meteorite analogues, we used the reflectance spectra of 90 ordinary, 16 CO, and 23 CV chondrites from Eschrig et al. (2021, 2022), accessible via SSHADE (Schmitt et al. 2018)5. The CV chondrites can be subdivided into six reduced (CVRed), nine oxidised Allende-like (CVOxA), and eight oxidised Bali-like (CVOxB) chondrites. Similarly, the 90 ordinary chondrites (OCs) can be split over 26 H, 21 L, and 43 LL chondrites. All spectra were acquired with the SHADOWS spectro-goniometer (Potin et al. 2018) at IPAG, Grenoble.

To identify the closest meteorite analogue for a given asteroid, we quantitatively compared them by minimising the L2 norm between their spectra. To emphasise the comparison on the presence and shape of absorption features, the minimisation accounts for small differences in slope and scale between the spectra with three free parameters that are varied during the minimisation procedure. The slope of the asteroid spectrum is adjusted by dividing it by an exponential function (Brunetto et al. 2006), which takes the form of

(1)

where k and cs are free parameters. This approach is explored and validated in Mahlke et al. (2023) for CO and CV chondrites. Additionally, a linear transformation is applied to the slopecorrected meteorite spectrum, in case the slope removal yields a suboptimal vertical alignment (normalisation) of the spectra,

(1)

where k and cs are free parameters. This approach is explored and validated in Mahlke et al. (2023) for CO and CV chondrites. Additionally, a linear transformation is applied to the slopecorrected meteorite spectrum, in case the slope removal yields a suboptimal vertical alignment (normalisation) of the spectra,

(2)

where a is an additive offset and treated as free parameters. The best-fit parameters are determined by minimising the L2 norm between the asteroid spectrum and the modified meteorite spectrum,

(2)

where a is an additive offset and treated as free parameters. The best-fit parameters are determined by minimising the L2 norm between the asteroid spectrum and the modified meteorite spectrum,

![$L_{2}=\sqrt{\sum_{i}\left[R_{\mathrm{ast}}\left(\lambda_{i}\right)-R_{\mathrm{met}}^{\prime}\left(\lambda_{i}\right)\right]^{2}}.$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa55785-25/aa55785-25-eq3.png) (3)

Prior to the minimisation, we fit the asteroid spectrum with Equation (1) and removed the slope component by division, followed by the normalisation of all spectra to unity at 0.7 μm. This ensures that the spectra are close in L2 distance to begin with, facilitating the minimisation routine. The minimisation is performed in two steps: an initial global search using differential evolution, followed by a local refinement using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm.

(3)

Prior to the minimisation, we fit the asteroid spectrum with Equation (1) and removed the slope component by division, followed by the normalisation of all spectra to unity at 0.7 μm. This ensures that the spectra are close in L2 distance to begin with, facilitating the minimisation routine. The minimisation is performed in two steps: an initial global search using differential evolution, followed by a local refinement using the Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm.

|

Fig. 2 Projection of asteroid spectra in the second and fourth principal components of Tholen (1984). Black crosses show the X-shooter scores, the numbers indicate the respective asteroid. Grey dots show the scores of the spectra used to define the taxonomy. Black letters show the mean scores of the taxa. L-types (following DM09 and M22) are highlighted in blue, Barbarians with red circles. |

3 Results

In this section, we compare the X-shooter spectra to their counterparts in the Gaia DR3 and present the taxonomic classification and comparison to meteorite spectra of the acquired spectra. We note that there are effectively two kinds of spectra visible in Figure 1: (1) spectra with absorption features around 0.9 μm and 2 μm ((1426) Riviera, (19156) Heco, and (57526) 2001 SD316); and (2) spectra with less pronounced features around 1 μm and 2 μm and variable slopes in the VisNIR.

3.1 Comparison to Gaia DR3

Overall, the Gaia spectra and X-shooter observations are in broad agreement. The spectra of (1426) Riviera, (19156) Heco, and (57526) 2001 SD316 show consistent absorptions around 1 μm, while the remaining targets are featureless in the UV-visible range in all observations. The UV is generally in agreement, apart from the first Gaia band, known to be affected by strong systematics. However, consistent reddening of the Gaia spectra with respect to the X-shooter observations is present longwards of ∼ 0.8 μm. These reddening spectra has been described previously in Gaia Collaboration (2023), Galinier et al. (2023), and Oszkiewicz et al. (2023). To our knowledge, no correction has been found. Systematic reddening is further present in the Gaia spectra towards the UV; however, classy automatically applies the correction from Tinaut-Ruano et al. (2023). Due to these discrepancies, we do not include the Gaia spectra in the following taxonomic classification.

3.2 Taxonomic classification

3.2.1 UV-visible following T84

In Figure 2, we show the reduced space spanned by the second and fourth principal components (PCs) of T84, which retain 29% of variance observed in the Eight-Color Asteroid Survey (ECAS) spectra that the taxonomy is based on. PC2 is proportional to the UV-visible slope, whereas PC 4 is representative of a pyroxene-like absorption feature at 0.9 μm.

T84 did not define an L-type class, however, the ECAS sample contained seven asteroids that are L-types based on their VisNIR classification in DM09 and M22. These asteroids are highlighted in blue in Figure 2. We similarly indicate the position of confirmed Barbarians in this space by means of their ECAS spectra scores, using polarimetric data from Cellino et al. (2014), Devogèle et al. (2018), and Bendjoya et al. (2022). The known L-types and Barbarians show elevated scores in the second PC with respect to S-types, corresponding to a steeper UV-visible slope, attributed to charge transfer absorptions in Fe2+−, Fe3+-bearing minerals (Gaffey & McCord 1978). They further show smaller PC 4 scores than S-types as the drop-off towards 1 μm is less pronounced and occurs towards a longer wavelength (1 μm, associated to olivine), as opposed to 0.9 μm (associated to pyroxene) for S-types.

Based on their UV-visible appearance, all X-shooter spectra are classified as S-types in T84, primarily due to their similarity in PC1 (not shown in Figure 2). However, we observed that at least two of our targets, (3682) Welther and (39745) 1997 AK17, are located among several L-types and Barbarians; whereas three more ((6476) 1987 VT, (21100) 1992 OB, and (30379) Molaro) are located in close proximity to the L-type region. The PC4 scores of these targets are significantly lower than the average S-type score.

|

Fig. 3 Same as Figure 2, but showing the first two principal components of DeMeo et al. (2009). The arrow indicates how increasing 2 μm absorption depth in the spectra affects their scores. The asteroid numbers are colour-coded by their best matching class. |

3.2.2 VisNIR following DM09

In Figure 3, we show the space spanned by the first two PCs of DM09, which retain 87% of variance of the slope-removed spectra used to define the taxonomy. PC 1 and PC 2 both represent pyroxene-rich compositions.

The classification of the X-shooter spectra following DM09 yields a mixture of K-, L-, S-, and X-types (refer to Table 2). (1426) Riviera, (19156) Heco, (21100) 1992 OB, and (57526) 2001 SD316 fall among the S-types and are classified as Sw (‘weathered’ S), Sq, and Srw respectively. For all but (21100) 1992 OB, S-type classifications are reasonable, as we observe a clear 1 μm absorption and evidence for a 2 μm feature, consistent with ordinary-chondritic composition (Nakamura et al. 2011). However, (21100) 1992 OB does not present similar absorptions, and its classification as Sw is likely due to its projection into a sparsely-populated region of the classification space, neither resembling S-types nor L-types, as defined in DM09.

In a similar manner, the remaining four X-shooter spectra fall between the K-, D-, T-, and L-types, into a region where only few of the 371 spectra used to define the taxonomy are located. (6476) 1987 VT and (72431) 2001 CD42 are classified as K-types; however, neither of them show the strong olivine absorption at 1 μm characteristic of this class. The classification of (30379) Molaro and (39745) 1997 AK17 as L-types is more consistent with their appearance. Both asteroids cluster in close proximity to the Barbarians in the DM09 space.

|

Fig. 4 Same as Figures 2 and 3, but showing the second and fourth latent component of Mahlke et al. (2022). |

3.2.3 VisNIR and albedo following M22

In Figure 4, we show the space spanned by the second and fourth latent components (LCs) of M226. The second LC presents pyroxene-like absorption features (refer to Fig. 5 in Mahlke et al. (2022)), meaning that spectra with pronounced 2 μm features will have increased scores in this component. The fourth LC largely resembles an olivine spectrum.

Consistent with DM09 and T84, the X-shooter spectra of (1426) Riviera, (19156) Heco, and (57526) 2001 SD316 are classified as S-types. Compared to DM09, (30379) Molaro, and (39745) 1997 AK17 remain L-types here, while (21100) 1992 OB and (72431) 2001 CD42 are also considered L-types here. (6476) 1987 VT and (3682) Welther are classified as M-types.

Nevertheless, the latter two asteroids also fall among the Barbarians in the M22 latent space. In Section 4, we place the four L- and two M-types observed here into the context of the L-type population. To summarise, Figure 5 shows the acquired X-shooter spectra in comparison to the template spectra of the most similar classes in T84, DM09, and M22. The upper part shows that the S-type classification of (1426) Riviera, (19156) Heco, and (57526) 2001 SD316 is in general agreement with the templates. The lower part shows the spectra of the remaining targets and a variety of templates.

3.3 Meteorite analogues

Next, we identified the closest meteorite analogue of each target using the L2-minimisation method described in Section 2.6. We compared the S-type spectra with OCs and the L/M-type spectra with CO and CV chondrites (Burbine et al. 1992; Nakamura et al. 2011). In Figure 6, we show the best three meteorite matches for each asteroid. All asteroid spectra are shown after the exponential slope component was removed (Equation (1)) to emphasise their spectral features. In Table 2, we summarise the matches.

After slope-removal, we observe two different shapes among the L/M-types. (3682)Welther, (6476) 1987 VT, (72431) 2001 CD42, and (21100) 1992 OB exhibit absorption features around 1 μm and 2 μm, whereas (30379) Molaro and (39745) 1997 AK17 appear featureless around 1 μm, instead presenting subtle 2 μm features and overall convex shapes.

For the OC-S-type comparison, we compute the L2 distance on the interval between 0.7 μm and 1.7 μm as the 2 μm region is affected by telluric absorption and drop-offs in the detector efficiency beyond 2.25 μm (Vernet et al. 2011). The high S/N of the 1 μm feature in the S-type spectra provides confidence that the comparison is still meaningful. For the CO/CV-L/Mtype comparison, we compare the spectra between 0.7 μm and 2 μm, again based on the S/N of the asteroidal spectra beyond 2 μm. We did not consider wavelengths below 0.7 μm due to the effect of terrestrial weathering on the meteorite spectra in this region (Salisbury & Hunt 1974; Cloutis et al. 2012b).

Four out of six L/M-type asteroids are matched to CVRed and CVOxA chondrites. However, neither match is perfect, and in particular (30379) Molaro and (39745) 1997 AK17 do not show good fits due to the lack of 1 μm feature in these asteroids. For (72431) 2001 CD42, two out of three best matches are CVOxA, and the third is a CVRed type. However, all three matches appear compatible with the asteroid, and we record CV as match, not a specific subgroup. For (21100) 1992 OB, there is a shift in the 1 μm absorption between the asteroid and the meteorites. We note that the VIS and NIR spectra provided by X-shooter are merged around 1 μm, which proved particularly challenging for this asteroid as there were large drop-offs in both spectral segments around the 1 μm. The shift may thus be artificial and we record CV as best match. (6476) 1987 VT presents the most convincing matches, with two CO and one CVOxA chondrites. Both the 1 μm and 2 μm feature are matched well. (3682) Welther is similarly matched well by two CO and one CVOxB chondrite up to 1.7 μm; however, we restricted the matching to this due to the strong telluric absorption at longer wavelengths, which is apparent in the divergent nature of the three best matches in the NIR. As for (6476) 1987 VT, we record CVOx and CO as best matches.

Regarding the three S-types, five out of nine best matches are H chondrites. For (1426) Riviera and (57526) 2001 SD316, H chondrites provide the most convincing matches. For (19156) Heco, we find good matches among H, L, and LL chondrites, and we thus did not assign it to a specific subclass. Nevertheless, we may conclude that (19156) Heco likely has a different composition than (1426) Riviera and (57526) 2001 SD316, judging by the wider shape of its 1 μm feature.

|

Fig. 5 Acquired X-shooter spectra in comparison to relevant class templates of T84, DM09, and M22. The top row shows X-shooter spectra presenting a 0.9 μm feature, the bottom row shows spectra that do not. The targets of the X-shooter spectra are indicated next to the spectra by their asteroid number in the corresponding colour. |

|

Fig. 6 Comparison of asteroid spectra obtained with VLT/X-shooter with ordinary, CO, and CV chondrites. For each asteroid, we show the three best matching meteorite spectra. The asteroid spectra are shown after removing an exponential slope component. Vertical lines show the wavelength range used for the comparison. |

4 Discussion

In this section, we discuss the spectral variability of L-types by combining our X-shooter observations with literature spectra of L-types, Barbarians, and CO and CV chondrites. We further discuss the perspectives of L-type identification with ESA’s Gaia and NASA’s SPHEREx.

4.1 L-type asteroid families

Our study confirms the presence of L-types in the Aquitania, Brangäne, Tirela/Klumpkea, and Watsonia (refer to Table 2 and Section 4.2). For Henan, we find a possible S-type interloper, (19156) Heco. Apart from family namesake (2085) Henan, an L-type according to DM09 and M22, this is to our knowledge only the second VisNIR spectrum, leaving doubt about the family’s L-type status.

Balossi et al. (2024) have recently revisited the family membership of all asteroids in the Tirela/Klumpkea and Watsonia families using Gaia DR3 observations. In Balossi et al. (2025), the authors confirmed the existence of a family in the region of (2085) Henan, whose largest member is in fact the L-type (460) Scania. again using orbital elements supported by spectral observations as basis of their analysis. In this updated family list, (19156) Heco does not appear, consistent with its classification as S-type here. In the following, we continue our analysis using the Scania family definition by Balossi et al. rather than the Henan family.

4.2 Spectral diversity among L-types: Reconciling taxonomy and mineralogy

All six L- and M-types we identified with X-shooter fall taxonomically on the edges or between established classes in T84, DM09, and M22 (refer to Figures 2 to 4). Neither of them resembles a larger group of spectra among all the spectra used to define these taxonomies. We thus observe a continuation of the trend of spectral diversity among L-types that was already apparent in previous observational and taxonomical studies (Devogèle et al. 2018; Mahlke et al. 2022). This diversity exceeds taxonomic class boundaries: while (3682) Welther and (6476) 1987 VT are classified as X/K- and M-types in DM08 and M22, respectively, we consider them to be closer to L-types in mineralogy based on (1) their 1 μm and 2 μm features (K-types do not show 2 μm absorption and M-types are featureless or with pyroxene as opposed to olivine features); and (2) their association with the Aquitania and Watsonia families.

To investigate this taxonomic discrepancy further, we combined spectroscopy with polarimetry and asteroids dynamics by compiling VisNIR (covering 0.45 μm to 2.45 μm) spectra of main belt asteroids that are known L-types (following M22), Barbarians, or in one of the five L-type host families (Aquitania, Brangäne, Scania, Tirela/Klumpkea, and Watsonia) using classy. We retrieved 30 spectra for 29 asteroids, including our five X-shooter spectra. We reject a spectrum of (1021) Flammario as it appears to be a C-type interloper in the Aquitania family. The sources of all spectra are given in Appendix A. Asteroid (679) Pax is included twice in this sample, and we chose to include both spectra to show sample variability.

A total of 14 of these asteroids are confirmed Barbarians, while insufficient polarimetric observations for the remaining asteroids make it too challenging to ascertain their status (see Table A.1). We assume here that L-types and Barbarians represent the same population of asteroids, following the interpretation that the 2 μm band and the polarimetry are both a compositional indicator of CAI (Devogèle et al. 2018; Masiero et al. 2023). Thus, we refer to all these asteroids as L-types, though they may be classified differently in DM09 or M22.

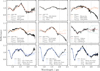

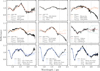

We then project the spectra into the taxonomical space of M22, refer to Figure 7. On the left hand side, we show the scores along the first and second LCs, where the first corresponds to an increase in the VisNIR slope and the second is proportional to 1 μm and 2 μm absorption depth as well as the albedo. The right hand side show the scores in the fourth LC on the x-axis, which resembles an olivine spectrum. We see that L-types are highly variable in terms of their slope, their 1 μm feature, and their 2 μm feature. In their extreme appearances, they resemble either feature-poor (P- or M-type) and feature-rich (S-type) asteroids. This diversity highlights the difficulty of a spectral definition of L-types, especially when aiming to reconcile the spectral class definition with all spectra of Barbarian asteroids, as further outlined in Mahlke et al. (2022). As a consequence, several asteroids that are canonical L-types and known Barbarians, such as (729) Watsonia and (980) Anacostia, are not classified as L in M22 (instead M and S respectively), based on the taxonomic imperative that classes are based on observations, not interpretations. Nevertheless, we emphasise that these asteroids are clearly related to the asteroids (e.g. via polarimetric evidence, Devogèle et al. (2018)) with more typical L-type spectra and should be regarded beyond their taxonomic classification.

The projection on the right hand side of Figure 7 refers to the L-types in terms of their main features around 1 μm and 2 μm. We observe an anti-correlation in the latent scores and a bimodal distribution. We refer to these two groups as LL and LM. In Figure 8, we show the mean spectrum and albedo plus standard deviation of each group. The LL group (dark blue in Figure 7) presents higher albedos, a more pronounced 2 μm band, and variable NIR slopes, spectrally resembling the class archetypes such as (234) Barbara and (387) Aquitania LM asteroids (light blue in Figure 7). They have a generally red appearance similar to M-types, with lower slope variability, lower albedos, and a less pronounced 2 μm absorption compare to the LL asteroids. A hint of an olivine-like absorption is visible in both groups around 1 μm, as highlighted in Figure 8. We emphasise that the chosen nomenclature LL/LM only serves a descriptive purpose here: LL resembles the archetypal L-types more closely, while LM approach M-types in their appearance. However, LM remain distinct from M-types, clearly set apart by their olivine-like 1 μm feature and their association with Barbarian asteroids, indicating compositions rich in CAIs as the LL group.

As shown in Figure 7, (234) Barbara and (5840) Raybrown can be seen as endmembers of the LL group, whereas the Watsonia family members (729) Watsonia and (1372) Haremari as well as asteroid (611) Valeria represent the LM endmembers. Curiously, both groups contain members of the Aquitania (LL: (387) Aquitania, (30379) Molaro, LM: (599) Luisa, (3682) Welther) and Brangäne families LL: (39745) 1997 AK17, LM: (606) Brangäne). The presence of Barbarian asteroids and family members across both groups again suggests that, while spectrally distinct, similar compositions can be found in both groups. On the other hand, Scania family members are exclusively found in the LL group. Balossi et al. (2025) show that the L-types (5840) Raybrown and (7763) Crabeels, previously considered to be interlopers in the S-type Agnia family, are in fact members of the Scania family.

Future surveys could reveal intermediate spectra and fill in the continuum, however, at this point, it appears unlikely that the asteroids included in the present study would represent edge cases of a hitherto un-sampled centre population. Therefore, we consider this separation to be a real bimodal distribution and not a sampling effect.

|

Fig. 7 Distribution of L-type asteroid and CO-CV chondrite spectra in the taxonomical space of M22. Asteroid spectra are shown as filled symbols, with two shades of blue depending on whether they fall into the LL or the LM group. The symbol indicates the family a given asteroid belongs to. Meteorite spectra scores are shown as open triangles, colour-coded by their respective class and subclass. Arrows show compositional interpretations of the axes of the space and an approximate vector for the effect of increasing space weathering on the score of a spectrum. Grey circles show the scores of spectra used to define the taxonomy in M22, black letters give the mean positions of taxonomic classes in the respective subspace. |

|

Fig. 8 Mean values and standard deviation of the reflectance spectra (top) and albedo (bottom) of the CO-CV chondrite subclasses and asteroid groups discussed in this work. The spectra were normalised to unity at 0.55 μm and shifted vertically for comparability. Vertical lines indicate olivine absorption minima from Sunshine & Pieters (1998). |

4.3 Representation of L-types among CO and CV chondrites

To investigate a mineralogical origin of the observed bimodality among L-types, we projected the reflectance spectra of CO and CV chondrites from Eschrig et al. (2021) into the M22 taxonomic space. As M22 incorporates albedo, we estimated the equivalent geometric albedos for the meteorites from their reflectance at 0.5 μm following Beck et al. (2021). The resulting distribution is shown alongside the L-type asteroids in Figure 7.

A clear offset is observed in the first LC, with asteroids generally exhibiting higher scores (redder slopes) than the meteorites. This aligns with laboratory simulations showing that space weathering tends to redden the surfaces of CO and CV chondrites (Lantz et al. 2017; Mahlke et al. 2024). We indicate the approximate effect of space weathering by vectors in Figure 7, demonstrating that increased surface age (reddening) primarily increases the first latent scores, while slightly decreasing the second and fourth scores. This largely accounts for the observed offset between the fresh meteorite surfaces and the weathered asteroid surfaces. However, we see that space weathering alone cannot explain the spectral diversity within the L-types, especially given that members of the same dynamical family (implying broadly similar surface ages) are found in both the LL and LM groups (e.g. Aquitania, Brangäne).

Regarding the distribution in the second LC, which is related to absorption feature depths at 1 μm and 2 μm and the albedo, we see that CO chondrites exhibit a bimodal distribution, mirroring the LL/LM split. We denote these CO subgroups as COr (feature-rich, higher score) and COp (feature-poor, lower score). This nomenclature is motivated by the mean spectra and albedos shown in Figure 8: the COr group displays significantly stronger 1 μm and 2 μm absorption features and higher albedos compared to the COp group, analogous to the differences between LL and LM asteroids, although the features in meteorites are more pronounced than in the weathered asteroids. The petrologic types (PTs) of these chondrites (indicating degrees of aqueous alteration and thermal metamorphism) were determined via Raman spectroscopy in Bonal et al. (2016). Among the COp group, six out of ten have petrographic types between PTs between 3.0 and 3.1, three have PTs between 3.6 and 3.7 (indicating more advanced thermal metamorphism), and one is undetermined. Among the COr group, there is one chondrite where Bonal et al. (2016) noted a PT of ≥3.6 and five for which PT determination was not possible, either due to high thermal metamorphism or terrestrial weathering. For three out of five of these undetermined ones, the Meteoritical Bulletin Database notes PTs between 3.5 and 3.6 (refer to Appendix B). Thus, we see indications that the COr/COp split is driven by varying degrees of thermal metamorphism. In a study of 16 CO chondrites, Cloutis et al. (2012a) identified similar spectral trends with increasing PT.

CV chondrites show a more continuous distribution in the M22 taxonomic space, however, regarding their mean spectral appearance in Figure 8, we again observed a separation of feature-rich (CVOxA) and feature-poor (CVRed, CVOxB) spectra. The subclass albedo distributions are not seen to separate fully; however, the mean albedos follow the trend of decreasing albedo with decreasing feature strength, as observed among CO chondrites and L-types.

The spectral characteristics of the LL group (higher albedo, prominent 2 μm and strong UV absorption) show a strong resemblance to the COr and CVOxA chondrites (see Figure 8). This connection is consistent with the high abundance of refractory inclusions found in particular in CO chondrites (Scott & Krot 2014). Although the olivine-like 1 μm feature is weaker in LL spectra compared to the meteorite spectra, it might be masked or subdued by space weathering effects (Chrbolková et al. 2021).

However, we do see several indications that COr and CVOxA chondrites do not represent the full mineralogical diversity of the LL group; namely, it is clear that endmembers such as (234)Barbara and (5840) Raybrown are not represented by these (or any other) meteorites. The primary indicator is the albedo distribution shown in Figure 8, where LL show mostly larger values than COr and CVOxA chondrites. Space weathering simulations of CO and CV chondrites have shown a slight decrease (∼ 0.02−0.03) in albedo with increasing surface age (Lantz et al. 2017; Mahlke et al. 2024); as such, we would expect the meteorites to be generally brighter than the asteroids. (234) Barbara has an albedo of 0.18 (Berthier et al. 2023), far exceeding the values of COr and CVOxA chondrites. The mismatch in albedos also affects the distributions of LL and COr/CVOxA in Figure 7, which, as noted above, cannot be reconciled by displacements along the space weathering vector alone. In particular, the elevated LC2 scores of the endmember asteroids cannot be obtained. While in part due to the albedo, this discrepancy is further due to deep 2 μm absorptions, as is the case for (234) Barbara and (5840) Raybrown. Both elevated albedos and deep 2 μm absorptions can be explained by increasing abundances of CAI on the surfaces of these asteroids (Devogèle et al. 2018; Masiero et al. 2023). Thus, we conclude that the largest CAI abundances of LL group asteroids are not represented by any CO or CV chondrite or any other meteorite.

We note that, in Mahlke et al. (2023), we identified CVOxA QUE 94688 as a possible analogue of (234) Barbara based on similarity of their slope-remove VisNIR spectra (refer to Figure 6 in Mahlke et al. 2023). Compared to that analysis, we include the albedo here as an additional comparison parameter, which ultimately suggests that (234) Barbara is among the LL that is not sampled among CO and CV chondrites.

For the LM group, which exhibits lower albedos and weaker spectral features, both COp chondrites and CVRed and CVOxB emerge as potential analogues based on their spectral shapes and albedos shown in Figure 8. This aligns with our previous findings (Mahlke et al. 2023) and the results from Section 3.3.

4.4 CO-CV parent bodies among L-type families

The presence of members from the same family (Aquitania, Brangäne) across both the LL and LM groups suggests a close compositional link among at least some members of both groups. It further indicates heterogeneity within the parent bodies of the respective families. This is consistent with previous studies of CV chondrites, indicating parent body heterogeneity (e.g. Greenwood et al. 2010). Gattacceca et al. (2020) suggest that CV chondrites sample two parent bodies: one represented by the CVRed and another by the CVOx groups. Thermal stratification of the CVOx parent body may lead to the diverse spectral signatures that we observe among CVOxA and CVOxB groups. A similarly layered or zoned heterogeneity of the CO chondrite parent body could explain the bimodality and diversity seen among COr and COp chondrites, if the groups are correlated with a degree of thermal metamorphism, as our sample suggests. Under these assumptions, families such as Aquitania and Brangäne with members in both LL and LM groups are candidates for the CO and CVOx parent bodies. The Watsonia family, whose members are exclusively in the LM group, might represent the parent body of the CVRed chondrites. However, mineralogical evidence also support a single parent CV body (Ganino & Libourel 2017). Establishing spectral homo- or heterogeneity in associated asteroid families can provide further constraints to solve this puzzle. Finally, the proposed Scania family (Balossi et al. 2025), exclusively represented among the LL, might be entirely unsampled.

Brož et al. (2024) investigated the source regions of carbonaceous chondrites in the main belt using dynamical simulations. While Brangäne is given as promising source of meteorites, consistent with our findings here, the authors concluded that Watsonia is an unlikely source of carbonaceous chondrite falls today given its age. Nevertheless, following Brož et al. (2024), another source of carbonaceous chondrites might come from the Baptistina family. While the authors ruled out a CO/CV composition for this family based on observed shift of the 1 μm feature in the spectrum of (298) Baptistina towards 1.00 μm (compared to 1.05 μm for an olivine-rich composition), the VisNIR spectrum of (298) Baptistina bears resemblance to that of (729) Watsonia (Lazzarin et al. 2004; Binzel et al. 2019) and the albedo offers a good match to the LM group. While other asteroids in this family show S-type spectra in the NIR and elevated albedos, the Baptistina family is embedded in the Flora family and likely presents a large fraction of interlopers. Further spectral investigations of this family are warranted to draw a firmer conclusion.

4.5 Large-scale identification and characterisation of L-types

A challenge in the identification of L-types is the requirement to observe both visible and NIR spectra to exclude possible other classes, such as S-types. This slows down their process of identification. Two ongoing space missions will provide major steps forward: ESA’s Gaia, providing asteroid spectra from 0.3 μm to 1 μm, and NASA’s SPHEREx, acquiring spectrophotometry from 0.75 μm to 5 μm. The potential of Gaia for L-type identification is less evident due to its limited wavelength coverage. Nevertheless, our study shows that L-types can be reliably separated from other asteroids, in particular S-types, as their appearance around 1 μm in combination with their UV-visible slope is sufficiently distinct. First, we see that known L-types in the ECAS observations cluster separately from S-types. Second, our X-shooter spectra of L-types cluster in the same region (for both, refer to Figure 2). The possibly reduced systematics and increased sample size of Gaia DR4 (end of 2026) should improve the identification of unknown L-types in this reduced space.

However, Gaia’s limited spectral coverage restricts the identification of weaker 2 μm features, severely limiting the mineralogical characterisation. The recently launched SPHEREx mission (Crill et al. 2024) promises a significant advance in this question, especially beyond 2.5 μm where JWST observations suggest that more diagnostic features are located (Gomez Barrientos et al. 2024).

The combination of the Gaia and SPHEREx datasets will thus be critical to refining the spectral census and description of L-types, clarifying their distribution, and testing the hypothesised bimodality within this ancient asteroid population. In addition, these observations will benefit from albedos provided by the WISE and upcoming NEO Surveyor missions (Mainzer et al. 2011, 2023). Albedos of L-types are generally between 0.1 and 0.2 (Figure 8), outside the ranges of the numerous S-complex (generally >0.2) and the C-complex (generally <0.1).

5 Conclusion

In this study, we present new UV-VisNIR spectra for nine asteroids belonging to dynamical families previously associated with L-type asteroids, obtained with VLT/X-shooter. Our analysis yielded the following key findings.

We identified four new L- asteroids, significantly increasing the sample of this rare class with high-quality, broad wavelength coverage from the UV to the NIR. Two targets were classified as M-types, nevertheless, we find strong evidence that they are close to L-types in mineralogy. Three targets were confirmed as S-types, representing ordinary-chondritic compositions, including one possible interloper in the Henan family.

The four L- and two M-types exhibit considerable diversity, confirming the spectral variability previously noted for this population. These spectra lack strong representations among the defining spectra of taxonomies such as DM09 and M22.

Combining our new observations with literature data, we identified a potential bimodal distribution among the broader L-type/Barbarian population. These two groups, termed LL and LM, are separated primarily by their 2 μm band depth and albedo, with the LL group showing stronger features and higher albedo.

A similar spectral and albedo bimodality (COr/COp) was observed among CO chondrites when projected into the M22 taxonomic space. Comparisons between the asteroid groups and meteorite data suggest the LL/LM bimodality is best matched by variations within the CO chondrite group (COr potentially linked to LL, COp to LM); although CV chondrites remain plausible analogues (LL: CVOxA, LM.: CVRed/CVOxB). The Aquitania and Brangäne families may represent remnants of heterogeneous CO or CVOx parent bodies, while the Watsonia family is a candidate source of CVRed chondrites.

The distinct spectral properties of L-types, particularly their steep UV-visible slope compared to S-types, show promise for large-scale surveys such ESA Gaia to enable their identification, despite its limited wavelength coverage.

Our results strengthen the link between L-type asteroids and carbonaceous chondrites, particularly CO chondrites, suggesting these asteroids sample parent bodies formed early in Solar System history, potentially containing high abundances of refractory materials, such as CAIs. The observed bimodality points towards significant heterogeneity within these parent bodies, possibly related to varying degrees of thermal metamorphism.

Future advancements in the asteroid spectral census, particularly the forthcoming Gaia DR4 and long-wavelength data from the SPHEREx mission, complemented by albedo from WISE/NEO Surveyor, will be critical. These datasets will allow for a more robust census of the L-type population, a clearer assessment of the proposed spectral bimodality, and refined mineralogical characterisation, offering deeper insights into the nature and distribution of these enigmatic relics from the early Solar System.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Alice Aléon-Toppani for advice on the CV-CO-L-type comparison and Roberto Balossi for insights into the Scania family. We further thank the anonymous referee for constructive comments that improved the manuscript. Based on observations collected at the European Southern Observatory under ESO programmes 113.26 HB.001 and 113.26 HB.002. This work was supported by the Programme National de Planétologie (PNP) of CNRS-INSU co-funded by CNES. This research has made use of LTE’s Miriade VO tool and LTE’s SsODNet VO service.

References

- Amelin, Y., Krot, A. N., Hutcheon, I. D., & Ulyanov, A. A., 2002, Science, 297, 1678 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Balossi, R., Tanga, P., Sergeyev, A., Cellino, A., & Spoto, F., 2024, A&A, 688, A221 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Balossi, R., Tanga, P., Delbo, M., Cellino, A., & Spoto, F., 2025, A&A, 702, A239 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, P., Schmitt, B., Potin, S., Pommerol, A., & Brissaud, O., 2021, Icarus, 354, 114066 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bendjoya, P., Cellino, A., Rivet, J.-P., et al. 2022, A&A, 665, A66 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Berthier, J., Carry, B., Mahlke, M., & Normand, J., 2023, A&A, 671, A151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Binzel, R. P., DeMeo, F., Turtelboom, E., et al. 2019, Icarus, 324, 41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bonal, L., Quirico, E., Flandinet, L., & Montagnac, G., 2016, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 189, 312 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brož, M., Morbidelli, A., Bottke, W. F., et al. 2013, A&A, 551, A117 [Google Scholar]

- Brož, M., Vernazza, P., Marsset, M., et al. 2024, A&A, 689, A183 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetto, R., Vernazza, P., Marchi, S., et al. 2006, Icarus, 184, 327 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burbine, T. H., Gaffey, M. J., & Bell, J. F., 1992, Meteoritics, 27, 424 [Google Scholar]

- Carry, B., & Berthier, J., 2018, Planet. Space Sci., 164, 79 [Google Scholar]

- Cellino, A., Belskaya, I., Bendjoya, P., et al. 2006, Icarus, 180, 565 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cellino, A., Bagnulo, S., Tanga, P., Novaković, B., & Delbó, M., 2014, MNRAS, 439, L75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chrbolková, K., Brunetto, R., Ďurech, J., et al. 2021, A&A, 654, A143 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutis, E. A., Hudon, P., Hiroi, T., Gaffey, M. J., & Mann, P. 2012a, Icarus, 220, 466 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutis, E. A., Hudon, P., Hiroi, T., et al. 2012b, Icarus, 221, 328 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crill, B. P., Werner, M., Akeson, R., et al. 2024, Proceedings of Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2020: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter Wave, 114430I [arXiv:2404.11017v1] [Google Scholar]

- Datson, J., Flynn, C., & Portinari, L., 2014, MNRAS, 439, 1028 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DeMeo, F. E., & Carry, B., 2014, Nature, 505, 629 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DeMeo, F. E., Binzel, R. P., Slivan, S. M., & Bus, S. J., 2009, Icarus, 202, 160 [Google Scholar]

- Devogèle, M., Tanga, P., Cellino, A., et al. 2018, Icarus, 304, 31 [Google Scholar]

- Eschrig, J., Bonal, L., Beck, P., & Prestgard, T., 2021, Icarus, 354, 114034 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eschrig, J., Bonal, L., Mahlke, M., et al. 2022, Icarus, 381, 115012 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fornasier, S., Clark, B., Dotto, E., et al. 2010, Icarus, 210, 655 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Frattin, E., Muñoz, O., Moreno, F., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 484, 2198 [Google Scholar]

- Gaffey, M., & McCord, T., 1978, Space Sci. Rev., 21 [Google Scholar]

- Galinier, M., Delbo, M., Avdellidou, C., Galluccio, L., & Marrocchi, Y., 2023, A&A, 671, A40 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration (Galluccio, L., et al.,) 2023, A&A, 674, A35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ganino, C., & Libourel, G., 2017, Nat. Commun., 8, 261 [Google Scholar]

- Gattacceca, J., Bonal, L., Sonzogni, C., & Longerey, J., 2020, EPSL, 547, 116467 [Google Scholar]

- Gomez Barrientos, J., de Kleer, K., Ehlmann, B. L., Tissot, F. L. H., & Mueller, J., 2024, ApJ, 967, L11 [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, R., Franchi, I., Kearsley, A., & Alard, O., 2010, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 74, 1684 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmann, J. L., Schneider, J. M., Wölfer, E., et al. 2023, ApJ, 946, L34 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, C., Brunetto, R., Barucci, M. A., et al. 2017, Icarus, 285, 43 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro, D., Angeli, C., Carvano, J., et al. 2004, Icarus, 172, 179 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarin, M., Marchi, S., Barucci, M., Di Martino, M., & Barbieri, C., 2004, Icarus, 169, 373 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlke, M., 2024, Simplified access of asteroid spectral data and metadata using Classy, Conference Abstract (EPSC 2024) [Google Scholar]

- Mahlke, M., Carry, B., & Mattei, P.-A., 2022, A&A, 665, A26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlke, M., Eschrig, J., Carry, B., Bonal, L., & Beck, P., 2023, A&A, 676, A94 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mahlke, M., Aléon-Toppani, A., Lantz, C., et al. 2024, Analogues of enigmatic L-types: The effect of space weathering on CV, CO, CK, and CL chondrites, Conference Abstract (EPSC 2024) [Google Scholar]

- Mainzer, A., Bauer, J., Grav, T., et al. 2011, ApJ, 731, 53 [Google Scholar]

- Mainzer, A. K., Masiero, J. R., Abell, P. A., et al. 2023, PSJ, 4, 224 [Google Scholar]

- Marschall, R., & Morbidelli, A., 2023, A&A, 677, A136 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Masiero, J., & Cellino, A., 2009, Icarus, 199, 333 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Masiero, J. R., Mainzer, A. K., Bauer, J. M., et al. 2021, PSJ, 2, 162 [Google Scholar]

- Masiero, J. R., Devogèle, M., Macias, I., Castaneda Jaimes, J., & Cellino, A., 2023, PSJ, 4, 93 [Google Scholar]

- Milani, A., Cellino, A., Knežević, Z., et al. 2014, Icarus, 239, 46 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mittag, M., Schröder, K.-P., Hempelmann, A., González-Pérez, J. N., & Schmitt, J. H. M. M., 2016, A&A, 591, A89 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, T., Noguchi, T., Tanaka, M., et al. 2011, Science, 333, 1113 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oszkiewicz, D., Klimczak, H., Carry, B., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 519, 2917 [Google Scholar]

- Piralla, M., Villeneuve, J., Schnuriger, N., Bekaert, D. V., & Marrocchi, Y., 2023, Icarus, 394, 115427 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Porto de Mello, G. F., da Silva, R., da Silva, L., & de Nader, R. V. 2014, A&A, 563, A52 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Potin, S., Brissaud, O., Beck, P., et al. 2018, Appl. Opt., 57, 8279 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury, J. W., & Hunt, G. R., 1974, J. Geophys. Res., 79, 4439 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B., Bollard, P., Albert, D., et al. 2018, SSHADE: “Solid Spectroscopy Hosting Architecture of Databases and Expertise” and its databases., OSUG Data Center. Service/Database Infrastructure [Google Scholar]

- Scott, E. R. D., & Krot, A. N., 2014, in Meteorites and Cosmochemical Processes, 1, ed. A. M. Davis, 65 [Google Scholar]

- Smette, A., Sana, H., Noll, S., et al. 2015, A&A, 576, A77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sunshine, J. M., & Pieters, C. M., 1998, JGR: Planets, 103, 13675 [Google Scholar]

- Sunshine, J. M., Connolly, H. C., McCoy, T. J., Bus, S. J., & La Croix, L. M., 2008, Science, 320, 514 [Google Scholar]

- Tholen, D. J., 1984, PhD thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson [Google Scholar]

- Tinaut-Ruano, F., Tatsumi, E., Tanga, P., et al. 2023, A&A, 669, L14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Vernet, J., Dekker, H., D’Odorico, S., et al. 2011, A&A, 536, A105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova, T. A., 2019, MNRAS, 484, 3755 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

Unlike T84 and DM09, M22 did not use PCA to derive the taxonomy, instead using a Mixture of Common Factor Analysers (MCFA) model. Both methods project the data into a lower-dimensional space. Unlike the principal space derived with PCA, however, the latent space derived with MCFA maximises both the variance of the reduced data and their representation as samples of latent populations following Gaussian distributions. While we note this theoretical difference, in practice, the latent and principal spaces are quite similar and can be thought of variance-maximising projections.

Appendix A Sources of literature spectra

In Table A.1, we list the asteroids regarded in Section 4 and their relevant properties.

Appendix B C Or and C Op split

In Table B.1, we list the meteorites regarded in Section 4 and their relevant properties.

CO chondrites regarded in this work.

References. All spectra are sourced from Eschrig et al. (2021).

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Asteroid spectra acquired with VLT/X-shooter (black line). We further show the Gaia DR3 spectrum of each asteroid (grey markers), having removed the first and last Gaia data point. For asteroids (1426) Riviera and (3682) Welther, we removed values that are strongly affected by telluric absorption features (shaded grey area) and interpolated the spectra in these regions. For (3682) Welther, we further show the spectrum acquired by the S3OS2 survey (blue line) that we used to choose the alternative solar analogue spectrum (refer to text for details). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Projection of asteroid spectra in the second and fourth principal components of Tholen (1984). Black crosses show the X-shooter scores, the numbers indicate the respective asteroid. Grey dots show the scores of the spectra used to define the taxonomy. Black letters show the mean scores of the taxa. L-types (following DM09 and M22) are highlighted in blue, Barbarians with red circles. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Same as Figure 2, but showing the first two principal components of DeMeo et al. (2009). The arrow indicates how increasing 2 μm absorption depth in the spectra affects their scores. The asteroid numbers are colour-coded by their best matching class. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Same as Figures 2 and 3, but showing the second and fourth latent component of Mahlke et al. (2022). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Acquired X-shooter spectra in comparison to relevant class templates of T84, DM09, and M22. The top row shows X-shooter spectra presenting a 0.9 μm feature, the bottom row shows spectra that do not. The targets of the X-shooter spectra are indicated next to the spectra by their asteroid number in the corresponding colour. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Comparison of asteroid spectra obtained with VLT/X-shooter with ordinary, CO, and CV chondrites. For each asteroid, we show the three best matching meteorite spectra. The asteroid spectra are shown after removing an exponential slope component. Vertical lines show the wavelength range used for the comparison. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Distribution of L-type asteroid and CO-CV chondrite spectra in the taxonomical space of M22. Asteroid spectra are shown as filled symbols, with two shades of blue depending on whether they fall into the LL or the LM group. The symbol indicates the family a given asteroid belongs to. Meteorite spectra scores are shown as open triangles, colour-coded by their respective class and subclass. Arrows show compositional interpretations of the axes of the space and an approximate vector for the effect of increasing space weathering on the score of a spectrum. Grey circles show the scores of spectra used to define the taxonomy in M22, black letters give the mean positions of taxonomic classes in the respective subspace. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Mean values and standard deviation of the reflectance spectra (top) and albedo (bottom) of the CO-CV chondrite subclasses and asteroid groups discussed in this work. The spectra were normalised to unity at 0.55 μm and shifted vertically for comparability. Vertical lines indicate olivine absorption minima from Sunshine & Pieters (1998). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.