| Issue |

A&A

Volume 705, January 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L6 | |

| Number of page(s) | 4 | |

| Section | Letters to the Editor | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557449 | |

| Published online | 08 January 2026 | |

Letter to the Editor

Evolution of ultracompact neutron star–helium star binaries

1

Instituto de Astrofísica de La Plata, IALP, CCT-CONICET-UNLP, Argentina and Facultad de Ciencias Astronómicas y Geofísicas de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque s/n, 1900 La Plata, Argentina

2

Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto de Astronomia, Geofísica e Ciências Atmosféricas Departamento de Astronomia, R. do Matão, 1226, Cidade Universitária, 05508-090 São Paulo, SP, Brazil

⋆⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

26

September

2025

Accepted:

25

November

2025

Context. Ultracompact binaries (detached and X-ray-emitting) are regularly detected and studied; however, it is not known whether even more compact configurations featuring degenerate stars exist. The recent discovery of PSR J1928+1815, which has a helium companion in a 3.6 h orbit, suggests a hitherto largely unexplored evolution toward “hyper-compact” configurations with Porb of ≤1 min.

Aims. This work aims to establish whether helium companions drive systems into hyper-compact configurations, and to clarify the evolutionary status of PSR J1928+1815.

Methods. We modeled the evolution of binary systems formed by a neutron star and a helium star that possibly previously experienced a common envelope phase. After an initial mass transfer episode, the donor detaches and this leads to the formation of a system with a white dwarf companion. We followed the evolution after detachment, when the donor becomes a compact degenerate star, up to the onset of the final Roche lobe overflow in hyper-compact conditions of the binary.

Results. We show that a sufficiently light helium secondary is compatible with the current state of PSR J1928+1815. After undergoing a Roche lobe overflow, the system first evolves into a detached configuration, with orbital periods in the range of the observed value of the PSR J1928+1815 system, and later into a hyper-compact configuration. We predict extremely short orbital periods for the latter state.

Conclusions. Our results indicate that the PSR J1928+1815 system is young (≲107 yr), since the second epoch that could match the observed orbital period is unable to explain the length of pulsar eclipses. We find that the evolution of such systems toward extremely short orbital periods (Porb) of ≲1 min is unavoidable unless the secondary becomes massive enough to explode as an electron-capture supernova. The hyper-compact stage is not prevented by evaporation, and strong gravitational wave emission is expected during this phase, with the system eventually ending up as a bright optical and gamma-ray transient.

Key words: binaries: close / stars: evolution / pulsars: general

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

The evolution of binaries that comprise at least one compact star is interesting both in its own right and because they can be strong X-ray and gravitational wave (GW) sources. While the existence and main features of ultracompact detached binaries (UCBs) and ultracompact X-ray binaries (UCXBs) are now well established, several evolutionary channels for compact binary systems remain largely unexplored (Tauris & van den Heuvel 2023). One recent important discovery has been the detection of a neutron star (NS)–helium star system in a tight orbit with Porb = 3.6 h by Yang et al. (2025; hereafter Y+25). The NS shows pulsar emission, which is identified as PSR J1928+1815. The pulsar companion has a mass > 1 M⊙. Since the orbit is tight (its semiaxis ≈1.5 R⊙) and the pulsar is eclipsed in 17% of the orbit, the companion must be something bigger than a white dwarf (WD) or another NS, and is most likely a helium star. While it has been conjectured that such a system should exist, this is the first observational confirmation. The most likely origin is a relatively recent common envelope phase that stripped away the hydrogen of the non-degenerate secondary star (Tauris & van den Heuvel 2023; Y+25). Therefore, it is timely to ask about the future evolution and specific features of this and similar binaries yet to be discovered.

Work has already been conducted on NS–helium star binaries (see, e.g., Wang et al. 2021). The recent detection of a concrete example by Y+25 serves as a benchmark and the initial point of the evolution of compact binaries toward some extremely compact configurations. In this study we modeled the evolution of NS–helium star binary systems, and here we report our main results. One of our main aims was to find plausible progenitors for the PSR J1928+1815 system and determine its present evolutionary status. We followed the full evolution of several systems, most of them up to the moment at which their evolved donor companion (a cool WD at this stage) reached orbital periods (Porb)≲1 min before the onset of the final Roche lobe overflow (RLOF). This evolution gives rise to a class of extreme systems, which we call “hyper-compact binaries” (HCBs) to distinguish them from the already known UCB and UCXB classes. Eventually, the HCB undergoes a WD–NS merger (or the WD explodes after electron capture), a stage that is not yet fully understood or properly characterized.

This Letter is organized as follows: In Sect. 2 we describe our evolutionary simulations and present the main results. In Sect. 3 we describe the conditions under which the donor star remnant in an HCB undergoes RLOF. Then, in Sect. 4 we discuss the possible further evolution of the HCB when it reaches the RLOF phase as a WD–NS pair. Finally, in Sect. 5 we give some concluding remarks. A more detailed account of our results will be presented elsewhere.

2. Calculations

It is well known that binaries with hydrogen main-sequence stars as secondaries cannot have periods as short as ∼1 hour. In a detached binary, the donor star radius (R2) must be smaller than its Roche lobe radius (RL). The condition R2 < RL directly leads to a minimum period (Pmin) that can be expressed as Pmin = 9 (ρ/ρ⊙)−1/2 h. Typical main-sequence densities of ∼1 ρ⊙ – where ρ⊙ is the central density of the Sun, ≈150 g cm−3 – render minimal periods of approximately a few hours (this argument will be refined and employed below). Evolved stars with typical central densities ≈103 − 104 g cm−3 on the helium zero age main sequence, or even WDs, would be appropriate donors for compact binaries with the shortest periods when the ultimate RLOF occurs. The PSR J1928+1815 system is compatible with this picture, and its evolved nature would allow a much more compact final configuration, as we show below.

We began by considering an NS with a typical mass (MNS; Horvath et al. 2017, 2023) of 1.4 M⊙ and a helium star with masses and periods in a range of values in order to account for the present status of PSR J1928+1815 and simultaneously achieve a global view of the evolution of this kind of system. This system could be the result of a recent common envelope phase exit (Y+25). To explore the general characteristics of the evolution of helium star–NS binary systems, we considered donors with initial masses (M2, i) of 0.50, 0.75, 1.00, 1.25, 1.50, 1.75, and 2.00 M⊙ together with the NS companion of 1.40 M⊙ on circular orbits with initial periods (Porb, i) of 1.2, 1.8, 2.4, 3.6, 4.8, 6.0, 7.2, 8.4, and 9.6 hours. We assumed solar heavy-element abundances and neglected the effects of rotation on the stellar structure. We considered in the calculations mass loss due to winds, as in Jeffery & Hamann (2010), and evaporation due to pulsar irradiation, as described in Stevens et al. (1992), with an efficiency factor of 0.1. We stopped our simulations if the mass of the donor was < 0.015 M⊙, if the age exceeded 14 Gyr, or if the orbital period became extremely short (Porb, i ≤ 1 min). We employed the binary evolution code presented in Benvenuto & De Vito (2003). The considered range of masses and periods allowed us to study a plausible scenario for the occurrence and final asymptotic fate of PSR J1928+1815 and similar systems, yet to be discovered. In most cases, a carbon-oxygen (CO) WD formed, although oxygen-neon-magnesium (ONeMg) WDs formed in some cases. Regardless of the interior composition, most systems ultimately underwent a NS–WD merger (see below). For results corresponding to the evolution of binary systems containing an NS and a more massive helium star companion, see Guo et al. (2025).

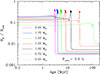

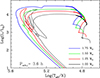

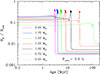

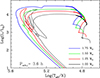

Since PSR J1928+1815 is eclipsed in 17% of its orbit, the helium companion has likely not yet undergone a RLOF. Otherwise, it would have quickly evolved to pre-WD conditions, and the eclipse would be much shorter. This is expected considering that, as already stated by Y+25, the eclipse is due to the material surrounding the donor star; they constrained the mass of the pulsar companion to 1.0 M⊙ − 1.6 M⊙, although slightly higher masses are possible (see Fig. 2 of Y+25). Consequently, the initial period was likely similar the present one, Porb, i = 3.6 h. In Fig. 1 we show the ratio of the radius of the donor star to the orbital radius for all the models with this value of Porb, i. Notice that this ratio is in a range that is compatible with the occurrence of eclipses at stages prior to the first RLOF, but after the RLOF it falls very fast, making it hardly detectable. Models with companion masses of 1.00, 1.25, 1.50, and 1.75 M⊙ are plausible progenitors. In Figs. 2 and 3 we present further details of the evolution of these models. These stars burn their helium cores and, after their exhaustion, undergo RLOF. The donor star transfers mass to the NS companion at a rate so high (with peaks of 10−7 M⊙ yr−1 to 10−5 M⊙ yr−1, increasing with the mass of the donor) that it exceeds the Eddington rate ( yr−1), i.e., the upper limit to the accretion rate attainable for an NS. Consequently, most of the matter is lost from the system. After detachment, the effective temperatures of the donor become very high. Due to this mass transfer, the orbit widens until the donor star detaches, and afterward it shrinks monotonically due to GW radiation. This scenario results in

yr−1), i.e., the upper limit to the accretion rate attainable for an NS. Consequently, most of the matter is lost from the system. After detachment, the effective temperatures of the donor become very high. Due to this mass transfer, the orbit widens until the donor star detaches, and afterward it shrinks monotonically due to GW radiation. This scenario results in  values during the helium main sequence evolution that are consistent with the determination of

values during the helium main sequence evolution that are consistent with the determination of  s s−1 for PSR J1928+1815 (Y+25). We found

s s−1 for PSR J1928+1815 (Y+25). We found  s s−1 for models with initial masses (M2, i)=1.00, 1.25, 1.50, and 1.75 M⊙, respectively.

s s−1 for models with initial masses (M2, i)=1.00, 1.25, 1.50, and 1.75 M⊙, respectively.

|

Fig. 1. Ratio of the radius of the donor star to the orbital radius for all the models with Porb, i = 3.6 h. The observed eclipse is possible before the RLOF episode (highlighted with thicker lines) for masses between 1 and 2 M⊙. After RLOF, the secondary shrinks very fast toward a WD configuration. This latter scenario does not match observations of the PSR J1928+1815 eclipse at this stage. |

|

Fig. 2. Evolution of systems that are plausible progenitors of the PSR J1928+1815 system. Thick portions of the tracks (on the right) correspond to conditions in which the donor star is undergoing RLOF. For luminosities (L) < 10 L⊙, the evolution follows WD cooling tracks up to the onset of a RLOF under HCB conditions. |

|

Fig. 3. Left: Evolution of the orbital period for the systems presented in Fig. 2. A rapid increase in the period occurs when mass transfer begins (almost vertical path on the right). After the donor star detaches with the maximum orbital period, GW radiation drives the orbit to shrink, eventually leading to the occurrence of another RLOF under HCB conditions. Right: Orbital period of these systems as a function of the donor mass. |

The subsequent evolution of the system is mainly driven by GW radiation. The donor detaches with an interior structure corresponding to a CO WD that cools as the orbit shrinks. In the case of PSR J1928+1815 and similar systems, sooner or later (depending on the initial conditions), the orbit will shrink (see Fig. 3), leading to an HCB in which a cool WD eventually undergoes RLOF and starts transferring mass to its NS companion. As shown below, this happens when Porb ≲ 1 minute.

In Fig. 4 we present the final masses and types of remnants as a function of the initial mass and orbital period for each model. Most of the systems reach HCB conditions and subsequent WD–NS merging. Remarkably, most of the models have a CO-rich interior, but for the most massive donor and the three longest initial periods, the remnant interior is ONeMg-rich. This necessarily has very important consequences for the characteristics of the WD–NS merger and the occurrence of nuclear reaction-driven transients, not addressed here.

|

Fig. 4. Final masses and types of donor remnants as a function of the initial mass and orbital period. Models connected with black lines have the same initial masses, given as labels in solar units. Filled blue squares correspond to UCXBs that avoid final WD–NS merging. Hollow blue squares denote models that do not undergo RLOF before WD–NS merging. Hollow (filled) red circles correspond to models that yield CO (ONeMg) WD–NS merging, while hollow cyan circles denote CO WD binaries that do not have time to reach the HCB stage. Filled green squares denote the plausible progenitors of PSR J1928+1815 that eventually experience CO WD–NS merging. |

We should point out some very important differences between the helium star scenario and the scenario in which the donor star initially has at least some outer hydrogen-rich layers. In the latter case, for suitable initial conditions, Porb shortens to a value as little as a few minutes, and the system reaches a UCXB state; the Porb then becomes longer again and the donor achieves a very low mass (see Fig. 1 of Sengar et al. 2017 and Fig. 6 of Echeveste et al. 2024). Systems with helium donors undergo this kind of evolution only for very low initial masses and orbital periods; see Fig. 4 and Wang et al. (2021). In the case of donors with hydrogen-rich layers, effective temperatures are far lower, making the outer layers more opaque and leading to the formation of convective zones. This, in turn, allows for the action of magnetic braking (see, e.g., Echeveste et al. 2024) and, eventually, irradiation feedback (Büning & Ritter 2004). In the case of the helium donor stars considered here, the outer layers are radiative, precluding the action of both effects1. Remarkably, evaporation plays a very minor role in these cases: to avoid the shrinkage of the orbit and the occurrence of an HCB and a final RLOF, evaporation would need to be three orders of magnitude stronger. Thus, for the case of helium donors with M ≳ 1 M⊙ and Porb, i ≳ 2.4 h, the formation of an HCB and a subsequent WD–NS merger seem unavoidable and remain a robust evolutionary prediction.

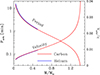

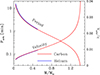

3. Roche lobe overflow in hyper-compact conditions

The minimum period at which HCBs undergo a final RLOF can be easily estimated. If we assume a circular orbit with semiaxis a, then, according to Kepler’s third law, Ω2 = G (MNS + MWD)/a3, where Ω is the orbital angular velocity, G is the gravitational constant, and MNS and MWD are the masses of the WD and the NS, respectively. The donor star, now a cool WD, will fill its lobe when its radius (RWD) equals that of the lobe (RL). The equivalent radius of a sphere with the volume of the lobe is RL = a F(q), where F(q)=0.49 q2/3[0.6 q2/3 + ln(1 + q1/3)]−1 and q = MWD/MNS (Eggleton 1983). Now, we can compute the orbital period at which the WD undergoes RLOF and the system becomes a hyper-compact X-ray binary (only slightly dependent on the WD composition). Here we used a mass–radius relation given in Hamada & Salpeter (1961) and studied two cases of homogeneous composition: helium and carbon. The results are given in Fig. 5. Our models are in agreement with this simple treatment. The onset of mass transfer immediately leads to extreme  rates of ≳10−2 M⊙ yr−1. This mass transfer episode cannot proceed stably, and its study requires careful treatment, which was not attempted in this work.

rates of ≳10−2 M⊙ yr−1. This mass transfer episode cannot proceed stably, and its study requires careful treatment, which was not attempted in this work.

|

Fig. 5. Orbital period at the onset of RLOF between a WD and an NS of 1.4 M⊙ as a function of the WD mass. Carbon and helium compositions are considered. The mass–radius relation given by the Hamada & Salpeter (1961) zero-temperature models is assumed. The orbital velocity at the onset of RLOF is given. The motion is very fast but non-relativistic. |

4. A glimpse of the final outcome

The shortest periods (≤1 min) achieved by the WD–NS systems before the onset of the RLOF conditions is one of the main results of this study and is the expected long-term evolution of the PSR J1928+1815 system. Clearly, this should not be the final state; but a subsequent final merger, an explosion of the WD or a common envelope stage is likely.

The mergers of WD–NS pairs have long been investigated. Bobrick et al. (2017) performed simulations of mass transfer in WD–NS binaries, finding that only binaries containing very light, helium WDs with MWD ≤ 0.2 M⊙ can support stable mass transfer and evolve into UCXBs, a result that is in agreement with our calculations. Zenati et al. (2019) studied WD–NS mergers in 2D hydrodynamical simulations for NSs with masses of 1−2 M⊙ and WDs with masses of 0.375−0.7 M⊙ and allowing for different internal compositions. They found weak nuclear burning transients of (1048 − 1049 ergs) and low 56Ni yields (up to 10−3 M⊙) compared to thermonuclear supernovae. It has been proposed that bright (GRB 230307A; Wang et al. 2024) and long-duration (GRB 211211A, Liu et al. 2025) gamma-ray bursts are due to WD–NS mergers. Kaltenborn et al. (2023) investigated WD–NS mergers with particular attention to the formation and properties of an accretion disk and its emissions; they followed the nuclear evolution of the object in detail, finding it can produce bright short-lived optical transients together with gamma-ray bursts.

A last issue, relevant for HCBs, is related to GW emission. For very short periods, ≤1 min, just before the onset of the RLOF, the GW emission would yield an amplitude  , with fGW the maximum frequency of GWs ∼1.6 × 10−2 Hz. The quantity ℳ is the chirp mass of the system and is equal to

, with fGW the maximum frequency of GWs ∼1.6 × 10−2 Hz. The quantity ℳ is the chirp mass of the system and is equal to  . The estimated maximum amplitude is then

. The estimated maximum amplitude is then

which would put HCBs in the class of “resolvable galactic binaries” or “extreme mass ratio inspirals” to be targeted by the LISA space mission (Piarulli et al. 2025), TianQin (Fan et al. 2024), or the B-DECIGO facility in the future (Ando 2024). In any case, the ultimate phases of the NS–WD merging would be very interesting to observe.

5. Concluding remarks

We have presented the evolution of low-mass NS–helium star binary systems. This effort was prompted by the recent discovery of the PSR J1928+1815 system (Y+25), which has a 3.6 h orbital period and a companion mass ≥1 M⊙. Y+25 concluded that the system was likely in a detached phase and that it would eventually experience a mass transfer episode much later. We explored a range of values for the initial donor and orbital periods to gain a broader understanding of the global behavior of these systems. According to our models, the progenitor of PSR J1928+1815 could have been a system with an initial donor mass of 1.00 to 1.75 M⊙ and Porb, i = 3.6 h before RLOF (see Fig. 4). Notably, the  of our models falls in the (albeit very uncertain) range determined from observations. Our calculations indicate that the system is young, ≲107 yr.

of our models falls in the (albeit very uncertain) range determined from observations. Our calculations indicate that the system is young, ≲107 yr.

Remarkably, the descendants of NS–helium star binary evolution, i.e., UCXBs, are formed only from systems with low masses and very short orbital periods. Otherwise, the orbit would continuously shrink and the system would become an HCB, undergo a RLOF, and produce a WD–NS merger, leading to a transient event. This is in sharp contrast with the case of the evolution of UCXBs formed from hydrogen-rich donors, for which the orbital period reaches a minimum value of a ∼ few minutes and then gets longer. Furthermore, the HCBs in their final states will be strong GW emitters, and likely sources in the 10−2 Hz band. The hunt for evolved systems of this type would be an observational challenge, even after the establishment of low-frequency GW facilities. In fact, the total population in the galaxy is expected to be small (Guo et al. 2025), of the order of a few dozen, and hyper-compact periods will have to be searched for carefully.

If these helium stars were isolated or in a much wider orbit than considered here, they would reach lower effective temperatures and develop outer convective layers; see, e.g., Habets (1986).

References

- Ando, M. 2024, 32nd General Assembly International Union (IAUGA 2024), Capetown, South Africa [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuto, O. G., & De Vito, M. A. 2003, MNRAS, 342, 50 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrick, A., Davies, M. B., & Church, R. P. 2017, MNRAS, 467, 3556 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Büning, A., & Ritter, H. 2004, A&A, 423, 281 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Echeveste, M., Novarino, M. L., Benvenuto, O. G., & De Vito, M. A. 2024, MNRAS, 530, 4277 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eggleton, P. P. 1983, ApJ, 268, 368 [Google Scholar]

- Fan, H. M., Lyu, X. Y., Zhang, J. D., et al. 2024, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2410.12408] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., Wang, B., Li, X., Liu, D., & Tang, W. 2025, ApJ, 992, 144 [Google Scholar]

- Habets, G. M. H. J. 1986, A&A, 167, 61 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada, T., & Salpeter, E. E. 1961, ApJ, 134, 683 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, J. E., & Valentim, R. 2017, in Handbook of Supernovae, eds. A. W. Alsabti, & P. Murdin (Springer), 1317 [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, J. E., Rocha, L. S., Bernardo, A. L., de Avellar, M. G., & Valentim, R. 2023, Astrophysics in the XXI Century with Compact Stars (World Scientific), 1 [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery, C. S., & Hamann, W. R. 2010, MNRAS, 404, 1698 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenborn, M. A. R., Fryer, C. L., Wollaeger, R. T., et al. 2023, ApJ, 956, 71 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.-X., Lü, H.-J., Chen, Q.-H., Du, Z.-W., & Liang, E.-W. 2025, ApJ, 988, L46 [Google Scholar]

- Piarulli, M., Buscicchio, R., Pozzoli, F., et al. 2025, Phys. Rev. D, 111, 103047 [Google Scholar]

- Sengar, R., Tauris, T. M., Langer, N., & Istrate, A. G. 2017, MNRAS, 470, L6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, I. R., Rees, M. J., & Podsiadlowski, P. 1992, MNRAS, 254, 19P [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tauris, T., & van den Heuvel, E. 2023, Physics of Binary Star Evolution. From Stars to X-ray Binaries and Gravitational Wave Sources, 1st edn. (Princeton University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B., Chen, W.-C., Liu, D.-D., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 506, 4654 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. I., Yu, Y.-W., Ren, J., et al. 2024, ApJ, 964, L9 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. L., Han, J. L., Zhou, D. J., et al. 2025, Science, 388, 859 [Google Scholar]

- Zenati, Y., Perets, H. B., & Toonen, S. 2019, MNRAS, 486, 1805 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Ratio of the radius of the donor star to the orbital radius for all the models with Porb, i = 3.6 h. The observed eclipse is possible before the RLOF episode (highlighted with thicker lines) for masses between 1 and 2 M⊙. After RLOF, the secondary shrinks very fast toward a WD configuration. This latter scenario does not match observations of the PSR J1928+1815 eclipse at this stage. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Evolution of systems that are plausible progenitors of the PSR J1928+1815 system. Thick portions of the tracks (on the right) correspond to conditions in which the donor star is undergoing RLOF. For luminosities (L) < 10 L⊙, the evolution follows WD cooling tracks up to the onset of a RLOF under HCB conditions. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Left: Evolution of the orbital period for the systems presented in Fig. 2. A rapid increase in the period occurs when mass transfer begins (almost vertical path on the right). After the donor star detaches with the maximum orbital period, GW radiation drives the orbit to shrink, eventually leading to the occurrence of another RLOF under HCB conditions. Right: Orbital period of these systems as a function of the donor mass. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Final masses and types of donor remnants as a function of the initial mass and orbital period. Models connected with black lines have the same initial masses, given as labels in solar units. Filled blue squares correspond to UCXBs that avoid final WD–NS merging. Hollow blue squares denote models that do not undergo RLOF before WD–NS merging. Hollow (filled) red circles correspond to models that yield CO (ONeMg) WD–NS merging, while hollow cyan circles denote CO WD binaries that do not have time to reach the HCB stage. Filled green squares denote the plausible progenitors of PSR J1928+1815 that eventually experience CO WD–NS merging. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Orbital period at the onset of RLOF between a WD and an NS of 1.4 M⊙ as a function of the WD mass. Carbon and helium compositions are considered. The mass–radius relation given by the Hamada & Salpeter (1961) zero-temperature models is assumed. The orbital velocity at the onset of RLOF is given. The motion is very fast but non-relativistic. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.