| Issue |

A&A

Volume 701, September 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A15 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Celestial mechanics and astrometry | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202452534 | |

| Published online | 28 August 2025 | |

Comparison of the Gaia-CRF3 and planetary ephemerides via asteroid observations

1

School of Astronomy and Space Science, Key Laboratory of Modern Astronomy and Astrophysics (Ministry of Education), Nanjing University,

163 Xianlin Avenue,

210023

Nanjing,

PR China

2

University of Chinese Academy of Sciences,

Nanjing

211135,

PR China

3

Research Center for Computing, National Research and Innovation Agency,

Bogor,

Indonesia

★ Corresponding author: jcliu@nju.edu.cn

Received:

8

October

2024

Accepted:

14

July

2025

Context. The Gaia satellite provides high-precision astrometric observations of Solar System objects, achieving positional accuracies at the milliarcsecond (mas) level. As the Gaia Celestial Reference Frame (Gaia-CRF3) serves as the optical realization of the International Celestial Reference System (ICRS), these observations offer a new means to assess the alignment between planetary ephemerides and the ICRS.

Aims. We aim to evaluate the orientation and rotational alignment between Gaia-CRF3 and the dynamical reference frame defined by planetary ephemerides.

Methods. We analyzed a sample of 1001 asteroids with high-quality Gaia observations. Their osculating orbits were computed using data independent of Gaia, under the Solar System dynamical model DE440, and were propagated to the epochs of Gaia observations. Positional differences between the propagated ephemerides and Gaia astrometry were used to estimate orientation offsets and rotation rates.

Results. Using a least-squares fit based on along-scan (AL) residuals, we derived orientation offsets of about 10 mas and rotation rates less than 0.5 mas yr−1 in the equatorial coordinate system. The robustness of these solutions was verified through iterative fitting and validated by both model-based and sample-based tests. When Gaia observations are incorporated into the orbit determination process, the orientation offset decreases dramatically to approximately 0.2 mas.

Conclusions. Our analysis reveals orientation offsets of approximately 10 mas, significantly larger than the reported DE440-ICRF3 discrepancies. This discrepancy likely stems from systematic biases inherent in historical asteroid astrometry. The inclusion of Gaia observations reduces these offsets to the sub-milliarcsecond level, demonstrating their crucial role in aligning dynamical ephemerides with the ICRS.

Key words: astrometry / ephemerides / reference systems / minor planets, asteroids: general

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

In 1998, the International Celestial Reference System (ICRS) replaced Fundamental Katalog No. 5 (FK5) as the primary celestial reference system (Feissel & Mignard 1998). According to IAU Resolution B3 (2021)1, the latest realizations of the ICRS are the third International Celestial Reference Frame (ICRF3; Charlot et al. 2020), based on very long baseline interferom-etry (VLBI) observations, and the Gaia Celestial Reference Frame (Gaia-CRF3), derived from Gaia observations of QSO-like sources (Gaia Collaboration 2023b). The alignment between ICRF3 and Gaia-CRF3 is accurate to within several tens of microarcseconds (µas) (Gaia Collaboration 2022).

In addition to kinematically nonrotating reference frames such as the ICRF, high-precision planetary ephemerides, historically referred to as dynamical reference frames, are also essential for space navigation and interplanetary exploration. Establishing a precise link between planetary ephemerides and kinematic reference frames is of critical importance. One of the most widely used sets of high-precision planetary ephemerides is the Development Ephemeris (DE) series, produced by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Earlier versions (e.g., DE102, DE200, DE202) were referenced to the dynamical equator and equinox (B1950.0/J2000.0). Starting with DE403, the planetary and lunar ephemerides have been aligned with the ICRS through a link to the ICRF (Standish 1995). For the inner Solar System, this alignment was achieved via VLBI observations of spacecraft orbiting planets, using quasars with well-determined positions in the ICRF as reference points (Newhall et al. 1986). In the latest DE series ephemerides, DE440 (Park et al. 2021), the inner planet orbits are tied to ICRF3 via VLBI observations of space-craft orbiting Venus and Mars (Folkner & Border 2015; Konopliv et al. 2016), while the orbits of Jupiter and Saturn are linked to ICRF3 through VLBA observations of the Juno and Cassini spacecraft (Jones et al. 2020). For the outer Solar System, additional constraints have been obtained from CCD observations of stellar occultations and close encounters involving Neptune and Uranus (da Silva Neto et al. 2005).

Beyond the major planets and the Moon, asteroids play a crucial role in the dynamics of the Solar System. Incorporating asteroid observations in an extragalactic reference frame provides an additional means to refine the link between dynamical models and kinematic reference systems. During the Hipparcos era, Bec-Borsenberger et al. (1995) used optical observations of asteroids to investigate the connection between the DE200 dynamical ephemerides and the Hipparcos reference frame. Subsequent studies have employed observations of asteroids in the extragalactic reference frames, as well as close encounters between asteroids and quasars (Chernetenko 2008; Nedelcu et al. 2010), but these results are limited by the insufficient number of available observations or close encounters. With the advent of Gaia, highly accurate astrometric observations of a vast number of Solar System objects (SSOs) are now available (Gaia Collaboration 2018, 2023a; Tanga et al. 2023). Given that Gaia-CRF3 has been adopted as the optical realization of the ICRS, it provides a unique opportunity to develop methods of investigating the link between planetary ephemerides and the ICRF using asteroid observations.

In this study, we present a new method of quantifying the alignment between dynamical ephemerides and the Gaia-CRF3 by fitting orientation parameters using asteroid astrometry. Section 2 introduces the Gaia SSO dataset, the orbit determination process, and the ephemeris position calculations. The estimated orientation offsets, rotation rates, and robustness assessments are presented in Section 3. In Section 4, we compare our results with previous studies, investigate the effects of model choices and sample selection, and examine the improvement of Gaia data on the alignment. A summary of our main conclusions is given in Section 5.

2 Data

2.1 Gaia observations

The Gaia mission has provided dedicated astrometric observations of SSOs since Data Release 2 (DR2), reporting positions at the CCD level as apparent coordinates (αG, δG) in the Gaia reference frame (Gaia Collaboration 2018; Tanga et al. 2023). These coordinates are measured with respect to the Gaia spacecraft and represent purely astrometric positions, uncorrected for physical effects such as annual aberration, light-time delay, or gravitational deflection. Most recently, the Focused Product Release (FPR) has significantly expanded the available SSO dataset, publishing over 46 million observations for approximately 156 000 objects, spanning the first 66 months of the mission (from mid-2014 to January 2020) (Gaia Collaboration 2023a). This temporal coverage ensures at least one complete orbital period for most main-belt asteroids (MBAs), while maintaining nearly uniform sky sampling.

For the present study, we initially selected a subset of 1051 asteroids that have at least one observation within the Gaia G-band magnitude range of 13–15, where the astrometric precision is optimal. At G ≈ 14, for instance, the along-scan (AL) positional uncertainty can reach as low as ~0.2 mas. Since the FPR catalog itself does not report apparent G magnitudes, this selection was based on the Gaia DR3 SSO catalog, which provides photometric information.

To avoid introducing systematic biases into our frame alignment analysis, we excluded 50 known or suspected binary asteroid systems identified by Liberato et al. (2024), as photocenter-barycenter displacements in such objects can significantly distort the measured positions. The resulting cleaned sample comprises 1001 single asteroids, designated as the G1315 sample. This final sample is dominated by MBAs (979 objects), with additional members including 2 near-Earth objects, 19 Mars-crossers, and 1 Jupiter Trojan. For these selected asteroids, we extracted all available observations from the FPR catalog. It is important to note that although the selection required at least one observation within the G = 13–15 magnitude interval, individual targets may still show variability outside this range. This is due to natural changes in apparent brightness caused by variations in heliocentric and geocentric distances, as well as phase angle effects during the observation period. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between G magnitude and AL error for the G1315 sample, highlighting the typical precision achieved by Gaia across different brightness levels.

|

Fig. 1 AL positional uncertainty as a function of G-band magnitude for the G1315 asteroid sample in Gaia DR3. |

2.2 Ephemeris position computation

2.2.1 Orbit determination

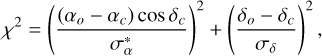

In this work, we developed software named “NJU_OD” for orbit determination and position propagation. Orbits were determined using a weighted least-squares method (Milani & Gronchi 2010), incorporating a dynamic outlier removal scheme. The observational data used for the orbit determination and initial orbital elements were obtained from the Minor Planet Center (MPC2). To ensure that the computed ephemeris positions remain independent of Gaia data, all Gaia-based observations were carefully excluded from the MPC dataset. For all observations from MPC, we applied the “vfcc17” error model (Vereš et al. 2017) to assign astrometric uncertainties. The outlier rejection procedure follows the Asteroids Dynamic Site (AstDyS) scheme, discarding observations with a normalized residual squared χ2 > 10, and restoring those with χ2 < 9.11. The residual metric is defined as

(1)

(1)

where (αo, δo) and (αc, δc) are the observed and computed positions in the equatorial coordinate system, and  , σδ are the associated 1σ uncertainties.

, σδ are the associated 1σ uncertainties.

The dynamical model is based on the DE440 ephemerides (Park et al. 2021), selected for two reasons: (1) the JPL DE series provides the dynamical realization of the celestial reference system as defined by the IERS Conventions (Petit & Luzum 2010), and (2) DE440 is the latest and most accurate version in the DE series. Gravitational perturbations from 16 of the most massive MBAs were included using the SB441-N16 supplement from JPL (Farnocchia 2021). Table 1 summarizes the adopted perturbing bodies and their respective masses. Both DE440 and SB441-N16 were obtained from the JPL ephemerides repository3. Furthermore, the SPICE Toolkit (Acton 1996; Acton et al. 2018), provided by the Navigation and Ancillary Information Facility (NAIF), was employed for processing the ephemerides. For the four perturbers (asteroids 65, 87, 88, and 107) that are also members of the G1315 sample, their self-perturbations were excluded in their individual orbit determination and propagation. Relativistic corrections were applied using the Einstein-Infeld-Hoffmann (EIH) formalism (Einstein et al. 1938), which accounts for post-Newtonian effects in the equations of motion. Nongravitational forces, such as thermal recoil (e.g., the Yarkovsky effect), were not considered in this analysis, as their influence is negligible over the relatively short propagation timescales involved.

Statistics of the 16 most massive perturbers in the main asteroid belt (Farnocchia 2021).

2.2.2 Position of the Gaia satellite

As is described in Section 2.1, Gaia asteroid observations are reported as apparent positions relative to the Gaia satellite. However, since the JPL planetary ephemerides do not include the position of the Gaia spacecraft, additional information is required to convert ephemeris positions into the Gaia-centric frame. The Gaia FPR catalog provides both barycentric and geocentric positions of the satellite for each observation epoch.

It is important to note that the Gaia reference frame is constructed using the INPOP10e planetary ephemerides (Fienga et al. 2016), whereas our dynamical model is based on DE440. Between these two ephemerides, there exists a discrepancy of approximately 154 km in the Solar System barycenter (SSB)-Earth vector during the Gaia observation time span, primarily due to differences in the treatment of trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs).

To mitigate this inconsistency, we adopted the geocentric position of the Gaia satellite rather than the barycentric one. Since the Earth-Gaia vector is independent of the underlying planetary ephemerides model, using geocentric positions avoids introducing systematic offsets in the alignment analysis (Deram et al. 2022). Therefore, the geocentric Gaia position is preferred in this work to ensure consistency with the DE440-based dynamical framework and to minimize model-dependent biases.

To ensure rigor, we evaluated the potential impact of the orientation offset between the INPOP10e and DE440 ephemerides on the Earth-Gaia vector. Liu et al. (2023a) found a sub-milliarcsecond rotation of the INPOP10e position system relative to DE440 in the equatorial coordinate system using pulsar timing astrometry. Note that the length of the Gaia-Earth vector is approximately 0.01 astronomical unit (au). A 0.5 mas rotation would cause Gaia’s geocentric position in DE440 to deviate by about 4 meters from that in INPOP10e. For observations of MBAs, this deviation results in position offsets of at most 5 µas, which is negligible compared to the current accuracy of Gaia SSO observation. This indicates that using the Gaia geocentric position in our calculations has no significant impact on the results.

2.2.3 Correction on ephemeris position

To ensure consistency with Gaia’s apparent astrometric measurements, we applied several corrections to the computed ephemeris position. First, light-time delay and gravitational deflection were taken into account. Gravitational bending by the Sun and planets was computed using the model of Klioner (2003). Since planetary deflections are negligible at the sub-5 µas level, only solar deflection was applied.

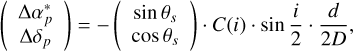

Considering that Gaia observations present the photocenter of the asteroids at each epoch, while ephemeris positions give coordinates of the mass center, we also corrected for the phase effect. For simplicity, all asteroids were assumed to be spherical, and light scattering on their surfaces followed the reciprocity principle. The offset in the tangent plane is such that (Seidelmann 1992)

(2)

(2)

where θs is the position angle of the solar point in the tangent plane, i the solar phase angle, d the diameter of the asteroid, and D the distance from the Gaia satellite to the asteroid at the observation epoch. The asteroid diameter, d, was sourced from the JPL Small-Body Database4. The function, C(i), depends on the actual brightness distribution over the visible surface, for which we used the expression from Hestroffer (1998):

(3)

(3)

For most asteroids, the position shift caused by the phase effect is less than 1 mas. When diameter estimates were unavailable in the JPL Small-Body Database, we omitted the correction by assuming d = 0.

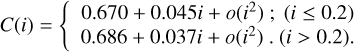

2.3 Timescale

In the Gaia catalog, observation epochs are expressed in barycentric coordinate time (TCB), in accordance with the Barycentric Celestial Reference System (BCRS) and the relativistic framework adopted by the mission (Tanga et al. 2023). However, the DE440 planetary ephemerides and MPC orbital elements are referenced to barycentric dynamical time (TDB).

To reconcile these differences, all computations for orbit determination and propagation were carried out in TDB, requiring conversion from TCB to TDB for epoch alignment.

Following IAU Resolution 2006 B35, the TCB-to-TDB transformation is given by

(4)

(4)

where JDTCB is the TCB Julian date and where LB = 1.550519768 × 10−8, T0 = 2443144.5003725, and TDB0 = −6.55 × 10−5 s are defining constants. This conversion ensures temporal consistency between the observational data and the computed ephemerides.

3 Results

3.1 Overview of position differences

After performing orbit determination using MPC data, we propagated the orbits to the Gaia observation epochs and compared the ephemeris positions (αE, δE) of G1315 with their observed positions (αG, δG) from Gaia. Due to the design of the Gaia satellite, single-epoch observations are predominantly one-dimensional: the AL direction has milliarcsecond-level precision, whereas the across-scan (AC) direction exhibits significantly lower accuracy, typically on the order of several hundred milliarcseconds (Gaia Collaboration 2016; Tanga et al. 2023). Consequently, we transformed the positional differences in right ascension and declination into the AL and AC directions of Gaia’s scanning plane, focusing primarily on the differences in the AL direction (∆AL). The transformation from (∆α*, ∆δ) to (∆AL, ∆AC) follows Gaia Collaboration (2018):

(5)

(5)

where θ is the position angle of Gaia scan direction at the observation epoch in the equatorial reference frame, defined as the angle between the AL direction and the direction to the north pole.

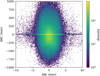

The upper panel of Fig. 2 displays the distribution of positional differences between Gaia observations and ephemerides in the AL and AC directions for G1315. It is evident that the deviations in the AL direction are approximately an order of magnitude smaller than the ones in the AC direction, reflecting the intrinsic difference in astrometric precision between the two directions in Gaia data. The lower panel shows the frequency distribution of ∆AL. Most of the differences are at the level of several tens of milliarcseconds, and the distribution appears nearly symmetric, indicating no significant systematic bias. While the majority of the residuals are below 100 mas, a small fraction of transits exhibit markedly larger discrepancies, with ∆AL exceeding larcsecond. Given that the typical formal uncertainties of the osculating ephemeris positions are at the 10–30 mas level, such outliers are unlikely to result from random noise alone. To mitigate their influence on the fitting results, we excluded these anomalous transits from subsequent analyses. In total, 406 transits were removed, accounting for approximately 0.6% of all transits in the dataset.

|

Fig. 2 Distribution of positional differences between Gaia observations and ephemerides in the AL, AC plane for G1315. The frequency distribution along the AL axis is reproduced in the bottom panel. |

3.2 Modeling the position differences and weighted least-squares fitting

To characterize the orientation offset between the Gaia-CRF3 and the ephemerides, we adopted a model including three rotation angles and three rotation rates. The positional differences were modeled as (Bec-Borsenberger et al. 1995; Chernetenko 2008)

![$\eqalign{ & \Delta {\alpha ^*} = \sin \,\delta \,\cos \,\alpha \left[ {{_x} + {\omega _x}\left( {t - {t_0}} \right)} \right] + \sin \,\delta \,\sin \,\alpha \left[ {{_y} + {\omega _y}\left( {t - {t_0}} \right)} \right] \cr & \,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\, - \cos \,\delta \,\left[ {{_z} + {\omega _z}\left( {t - {t_0}} \right)} \right], \cr} $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa52534-24/aa52534-24-eq7.png) (6)

(6)

![$\Delta \delta = - \sin \,\alpha \left[ {{_x} + {\omega _x}\left( {t - {t_0}} \right)} \right] + \cos \,\alpha \left[ {{_y} + {\omega _y}\left( {t - {t_0}} \right)} \right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa52534-24/aa52534-24-eq8.png) (7)

(7)

where ∆α* = (αG − αE) cos δ and Δδ = δG – δE represent the two-dimensional positional differences. The parameters ϵx, ϵy, ϵz describe the orientation offsets around the x, y, and z axes of the ICRS, respectively, while ωx, ωy, ωz are the corresponding rotation rates. The reference epoch, t0, was set to JD 2457 388.499779143 in the TDB timescale, consistent with the J2016.0 reference epoch of the Gaia-CRF3 frame.

As is discussed in Sect. 3.1, Gaia asteroid observations are nearly one-dimensional. Therefore, we transformed the position differences (∆α*, ∆δ) in Eqs. (6) and (7) into ∆AL to derive the effect of the frame orientation on AL coordinates. Combining Eqs. (6), (7), and (5), the relation between ∆AL and the orientation offset is

![$\matrix{ {\Delta AL = \left( {\sin \,\theta \,\sin \,\delta \,\cos \,\delta - \cos \,\theta \,\sin \,\alpha } \right)\left[ {{_x} + {\omega _x}\left( {t - {t_0}} \right)} \right]} \cr { + \left( {\sin \,\theta \,\sin \,\delta \,\sin \,\delta - \cos \,\theta \,\cos \,\alpha } \right)\left[ {{_y} + {\omega _y}\left( {t - {t_0}} \right)} \right]} \cr { - \sin \,\theta \,\,\cos \,\delta \left[ {{_z} + {\omega _z}\left( {t - {t_0}} \right)} \right].} \cr } $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa52534-24/aa52534-24-eq9.png) (8)

(8)

We then estimated the frame orientation parameters through weighted least-squares fitting:

(9)

(9)

where x = (ϵx, ϵy, ϵz, ωx, ωy, ωz) contains the fitting parameters, and y = (ΔAL1, ΔAL2, …,∆ALN) is the vector of observed AL differences for N data points. The matrix A contains the corresponding coefficients from Eq. (8).

The weight matrix, W, is defined as the inverse of the covariance matrix of the AL position differences:

(10)

(10)

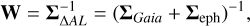

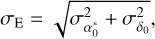

where ΣGaia and Σeph represent the uncertainties from Gaia observations and ephemeris positions, respectively. For ΣGaia, we adopted the formal errors provided by Tanga et al. (2023), including both random and systematic components. For observations within a single transit, the Gaia uncertainty matrix takes the following form:

(11)

(11)

where σ1, σ2,…, σ9 denote the random AL uncertainties of individual observations within the transit, and σs represents the systematic uncertainty, assumed to be common across the transit.

The formal uncertainties of ephemeris positions are not directly available during the orbit propagation process. In this work, we approximate the uncertainty, σE, for each asteroid as the geometric mean of the 1σ uncertainties in right ascension and declination at the reference epoch:

(12)

(12)

where ( ,

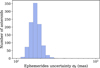

,  ) represent the positional uncertainties of the osculating coordinates (α0, δ0) Additionally, we assume that the errors in the propagated ephemerides are uncorrelated, resulting in a diagonal covariance matrix, Σeph. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of σE for the G1315 asteroid sample, with most uncertainties falling in the range of 10–30 mas. It is worth noting that these uncertainties reflect only random errors, as potential systematic effects were not accounted for in the fitting process.

) represent the positional uncertainties of the osculating coordinates (α0, δ0) Additionally, we assume that the errors in the propagated ephemerides are uncorrelated, resulting in a diagonal covariance matrix, Σeph. Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of σE for the G1315 asteroid sample, with most uncertainties falling in the range of 10–30 mas. It is worth noting that these uncertainties reflect only random errors, as potential systematic effects were not accounted for in the fitting process.

Table 2 presents the fitting results for the rotational alignment between the Gaia-CKF3 and the dynamical ephemerides. The orientation offsets in all three axes are measured at the milliarcsecond level, with a total offset of about 10 mas. These values exceed the random errors in the Gaia asteroid observations, suggesting the presence of systematic discrepancies in the ephemeris positions. The three components of the rotational rate are all below 0.4 milliarcseconds per year (mas yr−1). Over the period of the Gaia FPR catalog, these rotation rates will not significantly alter the orientation offsets.

The lower section of the table presents the correlation coefficients among these parameters. Notably, a strong anticorrelation is observed between ϵx and ωx (−0.68), indicating that uncertainties in the orientation offset along the x axis significantly impact the estimated rotational rate about the same axis. Similarly, ϵy and ωy are correlated at −0.66, while ϵz and ωz exhibit a correlation of −0.66. This strong anticorrelation is primarily due to the short period of Gaia observations, and it is expected to be improved with future data releases. The remaining correlations are generally weak (<0.15), suggesting that the other parameters were determined independently.

|

Fig. 3 Distribution of the ephemerides uncertainties, σE, for G1315 asteroids. |

Fitting results of the rotational alignment between the Gaia-CRF and the dynamical ephemerides frame, derived from the position differences between Gaia observation and ephemerides.

3.3 Robustness of fitting

In Sect. 3.1, we initially excluded one transit containing observations with ∆AL > 1″ to mitigate the influence of extreme outliers. To further assess the robustness and stability of the derived parameters, we implemented an iterative fitting scheme aimed at reducing the influence of the most deviant data.

Given that Gaia observations within the same transit are not statistically independent due to shared systematic effects and correlated uncertainties, we treated each transit, rather than individual CCD observations, as the basic unit in the iteration. At each step, we computed a quasi-normalized residual sum of squares,  , for each transit, i:

, for each transit, i:

(13)

(13)

where n is the number of CCD-level observations in transit i, yi = (ΔALi1, ΔALi2,…, ΔALin) denotes the vector of AL residuals, x is the vector of fit parameters, and Ai and Wi are the design and weight matrices, respectively, for that transit.

At each iteration, the transit with the largest  , value was identified and removed from the dataset. The fitting was then repeated on the updated set of observations. This process was repeated until convergence was achieved; that is, until the change in the fit parameters between successive iterations became smaller than a fixed threshold (<10−6).

, value was identified and removed from the dataset. The fitting was then repeated on the updated set of observations. This process was repeated until convergence was achieved; that is, until the change in the fit parameters between successive iterations became smaller than a fixed threshold (<10−6).

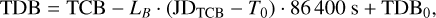

Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of the fit orientation offsets (ϵx, ϵy, ϵz) and rotation rates (ωx, ωy, ωz) throughout the iteration process. The fit parameters exhibit only minor fluctuations, all remaining well within their respective lσ formal uncertainties. Thus, the global solution is not unduly affected by a small number of outlier transits, supporting the robustness and reliability of the inferred orientation and rotation parameters.

|

Fig. 4 Iterative fitting results for orientation offsets and rotation rates. |

4 Explanation of the orientation offset

4.1 Comparison with previous works

Bec-Borsenberger et al. (1995) investigated the rotational alignment between the Hipparcos reference frame and the dynamical frame defined by the DE200 ephemerides, using astrometric observations of 48 minor planets. They reported orientation offsets of approximately (30.37, −19.32, −89.09) mas and rotation rates of (10.78, −9.49, 14.01) mas yr−1. In comparison, our results exhibit significantly smaller values, with orientation offsets at the level of a few to 10 mas and rotation rates around 1.4 mas yr−1. This marked improvement can be attributed to two main factors. First, we adopted the latest DE440 ephemerides, which offer a substantially higher accuracy than DE200, especially in the inner Solar System. The orientation offset between DE440 and DE200 alone exceeds 10 mas (Liu et al. 2023a), constituting a major source of discrepancy. Second, the consistency among different realizations of the ICRS has improved in recent years, and therefore a smaller offset between Gaia-CRF3 and DE440 is to be expected. In addition, our work contains precise observations of asteroids from the last 30 years, substantially improving the accuracy of asteroid orbit determination.

Folkner & Border (2015) assessed the alignment between DE ephemerides and the ICRF2 using VLBI tracking of space-craft orbiting Venus and Mars, concluding that the inner planets are aligned to the celestial reference frame within 0.2 mas. Similarly, Park et al. (2015) employed VLBA observations of Mars orbiters and found that the dynamical system of Earth and Mars in DE43O aligns with ICRF2 to within 0.3 mas. These VLBI-based studies represent the most precise available measurements of dynamical-to-celestial frame ties. Using pulsar timing and VLBI astrometry of millisecond pulsars, Liu et al. (2023b) estimated the orientation between the VLBI frame and the DE440-based dynamical frame. They reported offsets of (−0.9 + 0.2, −0.6 + 0.2, −0.3 + 0.2) mas about the x, y, and z axes, respectively. These values are significantly smaller than the offsets derived in our study, likely reflecting differences in methodology. Our indirect approach, which relies on asteroid orbit determination, introduces additional systematic uncertainties from asteroid observational data quality, temporal coverage limitations, and dynamical model completeness. Additionally, since the alignment estimation between Gaia-CKF3 and planetary ephemerides via asteroids is indirect, the selection and distribution of asteroid samples can affect the fitting results. Similar sample-dependent issues have also been discussed in Liu et al. (2023b) for pulsar-based analyses.

4.2 Impact of sample selection and dynamical model

Building on our G1315 sample selection criteria described in Sect. 2, we examined an alternative sample to evaluate the sensitivity of our results to sample selection. The supplementary sample SB343 consists of 343 massive MBAs incorporated in the dynamical model of DE440 planetary ephemerides (Park et al. 2021). These bodies represent a substantial fraction of the asteroid belt’s total mass, providing a robust dataset for evaluating systematics in asteroid ephemerides.

The orbital fitting results for the SB343 sample are presented in Table 3, obtained through identical reduction procedures with G1315. Our comparative analysis reveals significant differences between the samples: the SB343 results show a ~9 mas discrepancy in ϵx compared to G1315, while ϵy and ϵz differences remain smaller (~0.5 mas). Similar variations appear in the derived rotation rates, demonstrating the sensitivity of reference frame alignment to sample selection. Despite these variations, the total orientation offset, ϵ, shows consistent magnitude between samples (10.41 mas for SB343 versus 12.49 mas for G1315). This consistency strongly suggests that the ~10 mas offset between dynamical ephemerides and Gaia-CRF3 represents a genuine systematic discrepancy rather than an artifact of sample selection.

To evaluate the influence of the dynamical model on frame alignment, we further performed an additional analysis using the INPOP 10e planetary ephemerides (Fienga et al. 2016). This comparison is particularly relevant since Gaia-CRF3 was constructed using INPOP 10e, where we expect improved alignment. In this solution, we maintained identical observational data and dynamical modeling parameters to the G1315 reference solution, except for the perturbations from massive asteroids as these are not provided in INPOP10e.

The estimated orientation and rotation parameters from this INPOP10e-based solution are also presented in the last two rows in Table 3. Compared to the DE44O-based solution, the orientation offsets obtained with INPOP10e are moderately smaller, particularly in the ϵz component. However, the offsets remain at the milliarcsecond level, indicating that additional systematic effects may still contribute significantly to the observed frame misalignment.

Fitting results of the rotational alignment between the Gaia reference frame and the dynamical ephemerides frame, derived from different solutions.

|

Fig. 5 Comparison of osculating Keplerian elements between NJU_OD results and Gaia-FPR for the G1315 sample, expressed as [FPR – NJU_OD], The MPC-only solution uses observations solely from the MPC, while MPC+Gaia additionally includes astrometry from the Gaia FPR. All orbits are referenced to the FPR epoch. |

4.3 Orbit improvement with Gaia data

Alongside astrometric observations, Gaia also provides independent orbit solutions derived solely from its own data. In the latest FPR, these Gaia-based orbits show good agreement with those from JPL (Gaia Collaboration 2023a). This highlights the significant contribution of Gaia’s high-precision data to asteroid orbit determination. In this section, we incorporate Gaia astrometry into our orbit determination process to evaluate its impact on both orbital accuracy and alignment with the Gaia-CRF3 frame. For clarity, we refer to the solution without Gaia data as “MPC-only” and the solution including Gaia observations as “MPC+Gaia”.

Figure 5 compares the osculating Keplerian elements of both solutions to the official Gaia FPR results, using a consistent reference epoch. For the semimajor axis (α), both solutions achieve an excellent agreement with the FPR results at the level of 10−9, reflecting the dominant role of long observational time spans in constraining α. Specifically, the century-long data from MPC outweigh the ~5.5-year span of the Gaia FPR. In contrast, for eccentricity (e) and angular elements, the MPC+Gaia solution shows a significantly improved agreement with FPR (with most differences below 10 mas), demonstrating the impact of Gaia’s astrometric precision.

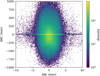

The post-fit residuals shown in Figure 6 further illustrate the improvement brought by Gaia data, particularly in the AL direction, where residuals are reduced to just a few milliarcseconds. This level of residuals is also consistent with the typical astro-metric uncertainties of Gaia asteroid observations. Additionally, a rotation fit to the post-fit residuals yields a rotation amplitude of approximately 0.2 mas (see Table 4), comparable to previously reported offsets between planetary ephemerides and the ICRF. This suggests that minor systematics in the historical MPC data likely contribute to the larger rotation seen in Table 2. Notably, such discrepancies become largely negligible once the orbit solutions are reprocessed using Gaia astrometry, underscoring its value for high-precision orbit determination.

Some of the residual systematics observed in historical data may stem from inconsistencies among the stellar reference catalogs used over the past decades. Several studies have demonstrated that regional biases in stellar positions and proper motions can lead to systematic errors in asteroid astrometry, which can be mitigated through catalog-based corrections (Chesley et al. 2010; Farnocchia et al. 2015). For instance, Eggl et al. (2020) applied Gaia DR2 data to correct historical asteroid observations. In the present work, we chose not to apply these corrections in order to preserve the independence of our comparison with the Gaia FPR solutions. This choice may partly explain the slightly larger rotation signal obtained in our analysis. However, it is unlikely to be the sole contributor, and a more comprehensive investigation into systematics in legacy astrometry is still needed.

|

Fig. 6 Post-fit residuals of Gaia observations for the MPC+Gaia orbit solution, shown in the AL and AC directions. |

Estimated frame orientation and rotation parameters from the residuals of the MPC+Gaia solution.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we conducted a systematic evaluation of the alignment between the Gaia-CRF3 celestial reference frame and the dynamical reference frame defined by planetary ephemerides DE440, using high-precision asteroid astrometry from the Gaia FPR. Based on a sample of 1001 well-observed asteroids, we analyzed the positional residuals between the FPR observations and propagated orbits derived independently of Gaia, and applied a weighted least-squares fit to determine orientation offsets and rotation rates. The derived orientation offsets at the reference epoch J2016.0 are (ϵx, ϵy, ϵz) = (−6.41 ± 0.10, −6.34 ± 0.10, −8.51 ± 0.11) mas, indicating a significant misalignment between Gaia-CRF3 and the dynamical ephemerides. The corresponding rotation rates, (ωx, ωy, ωz) = (−0.10 ± 0.05, 0.36 ± 0.05, 0.07 ± 0.05) mas yr−1, suggest no appreciable secular drift over the 66-month observational period. Iterative robustness tests, involving the rejection of outlier transits, demonstrate that the final solution is stable, with all parameters converging within 1σ.

While previous studies have reported orientation offsets of less than 1 mas between the DE planetary ephemerides and the ICRF, and the alignment between Gaia-CRF3 and ICRF3 is accurate to the microarcsecond level, the larger offsets found here imply the presence of additional systematic effects. Alternative solutions using different asteroid samples (G1315 and SB343) and independent dynamical models (DE440 and INPOP10e) yielded comparable total rotation to the DE-based solution, demonstrating that neither sample selection effects nor planetary ephemerides variations constitute the primary source of the observed frame misalignment. We identify reference frame inconsistencies in historical asteroid observations as the most probable contributor. This hypothesis is supported by a supplemental analysis using orbits determined from both Gaia and MPC observations, in which incorporating Gaia data reduces orientation offsets to 0.2 mas. The ~10 mas discrepancy in our primary solutions thus likely reflects accumulated frame biases in historical asteroid observations.

These findings highlight the power of Gaia’s asteroid astrometry in assessing the alignment of planetary ephemerides with the ICRF at the milliarcsecond level. Future Gaia data releases are expected to further improve both the precision of asteroid orbit determination relative to the Gaia-CRF and the alignment of dynamical ephemerides with the ICRS.

Acknowledgements

This work is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under grant Nos. 12373074 and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA0350300). We also acknowledge the science research grants from the China Manned Space Project with NO.CMS-CSST-2021-A11 and NO. CMS-CSST-2021-B10. This work presents results from the European Space Agency (ESA) space mission Gaia. Gaia data are being processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC). Funding for the DPAC is provided by national institutions, in particular the institutions participating in the Gaia MultiLateral Agreement (MLA). The Gaia mission website is https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia. The Gaia archive website is https://archives.esac.esa.int/gaia. We are particularly grateful to Dr. Wei Tian (Associate Researcher, Shanghai Astronomical Observatory) for his insightful discussions and constructive suggestions that significantly improved this work. We also sincerely thank the anonymous referee for his/her careful review and valuable comments, which greatly helped improve the clarity and quality of the manuscript.

References

- Acton, C., Bachman, N., Semenov, B., & Wright, E. 2018, Planet. Space Sci., 150, 9 [Google Scholar]

- Acton, C. H. 1996, Planet. Space Sci., 44, 65 [Google Scholar]

- Bec-Borsenberger, A., Bange, J. F., & Bougeard, M. L. 1995, A&A, 304, 176 [Google Scholar]

- Charlot, P., Jacobs, C. S., Gordon, D., et al. 2020, A&A, 644, A159 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chernetenko, Y. A. 2008, Astron. Lett., 34, 266 [Google Scholar]

- Chesley, S. R., Baer, J., & Monet, D. G. 2010, Icarus, 210, 158 [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Neto, D. N., Assafin, M., Andrei, A. H., & Vieira Martins, R. 2005, ESA SP, 576, 285 [Google Scholar]

- Deram, P., Fienga, A., Verma, A. K., Gastineau, M., & Laskar, J. 2022, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 134, 32 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eggl, S., Farnocchia, D., Chamberlin, A. B., & Chesley, S. R. 2020, Icarus, 339, 113596 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A., Infeld, L., & Hoffmann, B. 1938, Ann. Math., 39, 65 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Farnocchia, D. 2021, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Tech. Rep. [Google Scholar]

- Farnocchia, D., Chesley, S. R., Chamberlin, A. B., & Tholen, D. J. 2015, Icarus, 245, 94 [Google Scholar]

- Feissel, M., & Mignard, F. 1998, A&A, 331, L33 [Google Scholar]

- Fienga, A., Manche, H., Laskar, J., Gastineau, M., & Verma, A. 2016, Notes Scientifiques et Techniques de l'Institut de Mecanique Celeste, 104 [Google Scholar]

- Folkner, W. M., & Border, J. S. 2015, Highlights Astron., 16, 219 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration (Prusti, T., et al.) 2016, A&A, 595, A1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration (Spoto, F., et al.) 2018, A&A, 616, A13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration (Klioner, S. A., et al.) 2022, A&A, 667, A148 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration (David, P., et al.) 2023a, A&A, 680, A37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration (Vallenari, A., et al.) 2023b, A&A, 674, A1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hestroffer, D. 1998, A&A, 336, 776 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, D. L., Folkner, W. M., Jacobson, R. A., et al. 2020, AJ, 159, 72 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Klioner, S. A. 2003, AJ, 125, 1580 [Google Scholar]

- Konopliv, A. S., Park, R. S., & Folkner, W. M. 2016, Icarus, 274, 253 [Google Scholar]

- Liberato, L., Tanga, P., Mary, D., et al. 2024, A&A, 688, A50 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N., Zhu, Z., Antoniadis, J., Liu, J. C., & Zhang, H. 2023a, A&A, 674, A187 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N., Zhu, Z., Antoniadis, J., et al. 2023b, A&A, 670, A173 [Google Scholar]

- Milani, A., & Gronchi, G. F. 2010, Theory of Orbital Determination (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcu, D. A., Birlan, M., Souchay, J., et al. 2010, A&A, 509, A27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Newhall, X. X., Preston, R. A., & Esposito, P. B. 1986, IAU Symp., 109, 789 [Google Scholar]

- Park, R. S., Folkner, W. M., Jones, D. L., et al. 2015, AJ, 150, 121 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Park, R. S., Folkner, W. M., Williams, J. G., & Boggs, D. H. 2021, AJ, 161, 105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Petit, G., & Luzum, B. 2010, IERS Technical Note, 36, 1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Seidelmann, P. K. 1992, Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac (USA: University Science Books) [Google Scholar]

- Standish, E. M. 1995, JPL Interoffice Memorandum, 314.10-127, Technical Report [Google Scholar]

- Tanga, P., Pauwels, T., Mignard, F., et al. 2023, A&A, 674, A12 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Vereš, P., Farnocchia, D., Chesley, S. R., & Chamberlin, A. B. 2017, Icarus, 296, 139 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Statistics of the 16 most massive perturbers in the main asteroid belt (Farnocchia 2021).

Fitting results of the rotational alignment between the Gaia-CRF and the dynamical ephemerides frame, derived from the position differences between Gaia observation and ephemerides.

Fitting results of the rotational alignment between the Gaia reference frame and the dynamical ephemerides frame, derived from different solutions.

Estimated frame orientation and rotation parameters from the residuals of the MPC+Gaia solution.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 AL positional uncertainty as a function of G-band magnitude for the G1315 asteroid sample in Gaia DR3. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Distribution of positional differences between Gaia observations and ephemerides in the AL, AC plane for G1315. The frequency distribution along the AL axis is reproduced in the bottom panel. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Distribution of the ephemerides uncertainties, σE, for G1315 asteroids. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Iterative fitting results for orientation offsets and rotation rates. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Comparison of osculating Keplerian elements between NJU_OD results and Gaia-FPR for the G1315 sample, expressed as [FPR – NJU_OD], The MPC-only solution uses observations solely from the MPC, while MPC+Gaia additionally includes astrometry from the Gaia FPR. All orbits are referenced to the FPR epoch. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Post-fit residuals of Gaia observations for the MPC+Gaia orbit solution, shown in the AL and AC directions. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.