| Issue |

A&A

Volume 701, September 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A180 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Astrophysical processes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555920 | |

| Published online | 12 September 2025 | |

A deep search for radio pulsations from the 1.3 M⊙ compact-object binary companion of young pulsar PSR J1906+0746

1

Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, Science Park 904, 1098 XH Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2

ASTRON, the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Oude Hoogeveensedijk 4, 7991 PD Dwingeloo, The Netherlands

⋆ Corresponding authors: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

12

June

2025

Accepted:

22

July

2025

Double pulsar systems offer unrivaled advantages for the study of astrophysics and fundamental physics. Only one such system has been visible so far, however: PSR J0737−3039. Its component pulsar B has now rotated out of sight due to the general relativistic effect of geodetic precession. We know, however, that these precession cycles can also pivot pulsars into sight, and that this precession occurs at similar strength in PSR J1906+0746. This source is a young, unrecycled radio pulsar that orbits a compact object with mass ∼1.32 M⊙. We present a renewed campaign to detect radio pulsations from this companion two decades after the previous search. The two key reasons driving this reattempt are the possibility that the companion radio beam has since precessed into our line of sight, and the improved sensitivity now offered by the FAST radio telescope. In 28 deep observations, we did not detect a credible companion pulsar signal. After comparing the possible scenarios, we conclude the companion is still most likely a pulsar that does not point at us. We next present estimates for the sky covered by such systems throughout their precession cycle. We find that for most system geometries, the all-time beaming fraction is unity, that is, observers in any direction can see the system at some point. We conclude that it is still likely that PSR J1906+0746 will be visible as a double pulsar in the future.

Key words: pulsars: general / pulsars: individual: PSR J1906+0746

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Double pulsar systems are highly valuable for strong-field tests of general relativity (GR) and for stellar evolution studies (as reviewed in, e.g., Kramer & Stairs 2008). To date, the only double pulsar system that is (or more accurately: has been) visible is PSR J0737−3039A/B. It consists of a recycled millisecond pulsar (MSP), PSR J0737−3039A (Burgay et al. 2003), and a young, normal pulsar, PSR J0737−3039B (Lyne et al. 2004). Observations of PSR J0737−3039A/B helped us to improve our understanding of the pulsar wind, the plasma surrounding it, the orbital modulation, and the pulsar magnetosphere (Lyne et al. 2004). It further enabled tests of GR and of modified gravity by precise measurements of the post-Keplerian (PK) parameters (Kramer et al. 2006). The spin precession rates of A and B were constrained (Perera et al. 2010). It furthered our understanding of the origin and evolution of double neutron star (DNS) systems and improved our estimates of the DNS coalescence rate for ground-based gravitational-wave (GW) detectors.

The huge scientific potential of these double pulsar systems prompts us to look for more, even though (or especially because) they are rare. One important factor in the visibility of double pulsar systems is geodetic precession (Damour & Ruffini 1974). This GR effect causes changes in the direction in which the pulsar beams are emitted on timescales of mere years. This causes great variation in the visibility and detectability of these systems from one decade to the next. PSR J0737−3039B, for example, is no longer visible (Noutsos et al. 2020). On the other hand, systems that were single pulsars at detection may since have temporarily changed to double-pulsar systems. Out of a number of such candidate binaries, one very promising system is PSR J1906+0746 (Lorimer et al. 2006; van Leeuwen et al. 2006, 2015). PSR J1906+0746. This young pulsar (∼112 kyr) is on a very short 3.98 h orbit around another compact object. Since the discovery in the Arecibo L-Band Feed Array pulsar (PALFA) survey with Arecibo in 2004, precise timing solutions (Kasian 2012; van Leeuwen et al. 2015; Vleeschower 2024) have determined the exact parameters of the masses of the system and established the companion mass to be 1.32 M⊙. As noted initially by Lorimer et al. (2006) and again by Yang et al. (2017), the PSR J1906+0746 system shares similarities with PSR 0737−3039A/B in many aspects. The similarities include important measures such as the neutron star masses, eccentricity, orbital period, geodetic precession rate, and the strong magnetic field of the young pulsar in both systems. Intriguingly, the recycled pulsars in systems like this are a priori more likely to be visible because their radio flux densities are generally have higher and their lifetimes are longer than those of normal pulsars (Lyne & Graham-Smith 2012; Yang et al. 2017). PSR J0737−3039A is indeed visible. No recycled pulsar has yet been observed in the PSR J1906+0746 system, however.

Earlier deep searches with Arecibo found no radio pulsations from the companion to PSR J1906+0746. This indicates that the companion might be a white dwarf (WD), a pulsar whose radio beam does not intersect our line of sight (LOS), or a faint pulsar with a radio luminosity below 0.1 mJy kpc2 (Lorimer et al. 2006). A targeted search with Chandra on PSR J1906+0746 did not detect any significant signal from the system either (i.e., from either the young pulsar, the MSP, or their interaction; Kargaltsev & Pavlov 2009). Nevertheless, the high geodetic precession rate of ∼2.19° yr−1 (predicted by GR; see the equations in Kramer & Wex 2009; Wang 2025) means that the radio beam of the presumptive companion pulsar might precess into our LOS in the future (unless the spin axis of the companion is aligned with the total orbital angular momentum axis of the system, as is the case for PSR J0737−3039A; Ferdman et al. 2013). It is therefore meaningful now to re-examine the visibility of the companion, 18 years after the previous searches. To do this, we used > 2 years of highly sensitive Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST; Jiang et al. 2020) observations from our PSR J1906+0746 campaign (Wang et al., in prep.) that were taken between March 2022 and July 2024.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we introduce the FAST observations of PSR J1906+0746. The data reduction, the search pipeline for a companion pulsar that is based on PRESTO, the orbital demodulation methods, and the analysis of the possible companion signal are presented in Sect. 3. We discuss the implications in Sect. 4.

2. Observations and data reduction

2.1. Observations

FAST, located in Guizhou, China, is the largest and most sensitive single-dish radio telescope in the world. We analyzed 28 observations taken between March 2022 and July 2024 (Wang et al., in prep.). With the 19-beam (central) receiver, we used the tracking mode to observe PSR J1906+0746, and we used the on-off mode to observe the flux calibrator PKS 2209+080. The bandwidth of the FAST pulsar backend is 500 MHz around a central frequency of 1250 MHz. The number of channels is 4096. The data are recorded in the search mode with a sampling time of 49.152 μs. During the initial 1 minute of data taking on the pulsar, the noise diode continued to fire and thus tied the observation to the flux calibration source. Offline, the data were cleaned from radio frequency interference (RFI), were incoherently dedispersed, and calibrated for polarization and flux.

2.2. Data reduction

We used PRESTO1 (Ransom 2011) to produce the time series from the filterbank files (i.e., we dedispersed and integrated over all frequencies), and we next converted the time series into power spectra using fast Fourier transforms (FFTs), and we searched these. We started by employing rfifind to find and remove the most prominent RFI. We next identified topocentric periodic RFI without dispersion measure (DM). The frequencies of this RFI and of PSR J1906+0746 were added to a so-called zap list of frequencies, such that they could be blanked in the subsequent stages.

We then used prepsubband to dedisperse the time series using DM = 217.7508 pc cm−3 and corrected for it such that it was valid for the Solar System barycenter. These barycentered time series were input to the orbital demodulation as described in the next subsection. The outputs were time series that were corrected for the frame of motion of the companion. We used a fast Fourier transformation for them and corrected for excess red noise. Finally, we searched the resulting power spectra for periodic candidates2 would be much reduced in our 49.152 μs samples. using accelsearch, summing 1−16 harmonics to cover narrow and wide pulses. As the orbits had already been demodulated, we did not employ a further acceleration search in this step. The candidates with the highest S/N were analyzed further, as described in Sect. 3.1.

2.3. Orbital demodulation

The system is a tight binary, and the companion is continuously and strongly accelerated. Our ∼2 h observations span a significant part of the 3.98 h orbit. This ever-changing Doppler shift of the companion spin frequency throughout the orbit means that any stable companion periodicity is washed out in the observed data. For systems with well-measured parameters, however, this smearing can be counteracted by taking out the expected orbital motion from the barycentered dedispersed time series (Lyne et al. 2004). We used pysolator3 (Ridolfi 2020) for this purpose. It removes the Rømer delay predicted for the companion orbit and resamples the time series to transform the signal to the center of mass of the binary system.

The exact ephemeris of the known pulsar, including the eccentricity of 0.085 and the mass fraction q, is essential input for this transformation. The mass fraction is needed to calculate the semimajor axis xc for the companion from that of the pulsar xp, for which we used xc = qxp. For PSR J1906+0746, the pulsar mass mp = 1.291 ± 0.006 M⊙ and the companion mass mc = 1.322 ± 0.006 M⊙ (van Leeuwen et al. 2015). The q range that covers this 1σ mass uncertainty must therefore be [0.952, 1.002]. To remain completely sensitive to companion spin frequencies as high as 1000 Hz in even our longest 4-h observations, the step in q must be 0.0001 at most. Using the ephemeris from the long-term timing of PSR J1906+0746 by Vleeschower et al. (in prep.) and the q range described above, we produced demodulated companion trial time series for each observation.

3. Results

3.1. Candidate vetting

For each of our 28 observations, we produced characteristic (prepfold) plots for the candidates with the highest S/N in the periodicity search. A total of 4 × 104 such candidates were visually inspected. For each good candidate, we folded the original raw data, now without first integrating over frequency, to examine the structure of the frequency domain. Pulsars are generally broadband, while RFI is usually narrowband.

3.2. Candidates

3.2.1. The 2.059 s candidate

We found a strong candidate with a period of 2.0594338 s first in the 20230716 observation (see Fig. 1a), and soon thereafter, it was confirmed at four other epochs. The period disagrees with the expected MSP, however, and would require a nonstandard evolution scenario if it were proven to be real. After folding the candidate from the raw data, we found it to be a narrowband periodic signal in the 1309.4−1312.6 MHz frequency band (Fig. 2). We conclude that this is RFI, likely arising from a radar system or a navigation satellite. Another two candidates at other periods were subsequently found to stem from the same frequency band. This long-duration narrowband RFI was too weak to be clipped by rfifind and accelsearch, which means that it will likely appear in other FAST pulsar search projects. These studies are advised to incorporate RFIClean (Maan et al. 2021) in their search pipeline.

|

Fig. 1. prepfold diagnostic plot. The candidate stands out when it displays a pulsar-like integrated profile (top subpanels; two rotations shown) and a near-constant period when it is demodulated at the orbit of the trial companion (bottom subpanels). Left (a): Candidate with a period of 2.059 s. Middle (b): Candidate with a period of 4.019 s. Right (c): Candidate with a period of 42 ms. |

|

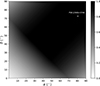

Fig. 2. Flux density of the 2.059 s candidate against frequency and pulse phase, folded with dspsr. The zoom-in plot shows the origin of the falsified candidate: It is narrowband RFI around 1310 MHz. |

3.2.2. The 4.018–4.045 s candidate

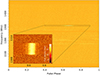

A bright, apparently modulated candidate with a spin period of 4.033 s was initially found in the 20231016 observation. It was at first considered to be the 28th harmonic of PSR J1906+0746, but further investigation found candidates with similar spin periods in a number of other observations that were clearly not the harmonic. At its highest, the candidate reaches a S/N of 24σ (see Fig. 1b). It shares the same strong and weak points as the previous candidate. The raw data again showed it to be periodic RFI, now around 1090 MHz, with a complex frequency-phase structure (Fig. 3); based on the frequency, these are possibly aircraft transponders.

|

Fig. 3. A zoom-in on the frequency range around the 4.019 s candidate. We show the flux density against frequency and pulse phase. |

3.2.3. The 42 ms candidate

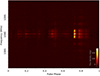

A faster candidate with a period 41.9379 ms was detected in the dedispersed time series of observation 20221110 (see Fig. 1c) at 8σ. This period fits the mildly recycled pulsar well that is expected to accompany PSR J1906+0746 (see van Leeuwen et al. 2015 for a list of these systems). The candidate is especially convincing because its period (denoted by the persistent apparent vertical line in the bottom subplot of Fig. 1c) is only stable in the demodulated time series at a very specific companion mass between 0.9867 < q < 0.9899, for example, the q value for Fig. 1c is 0.98767, which led to a PRESTO significance level of P(Noise) < 2 × 10−15 or 7.9σ. This limited mass-ratio range strongly suggests an astrophysical origin, which is hard to mimic. No pulsar (or RFI) is visible in the frequency-phase diagram (Fig. 4) we composed by dedispersing the original RFI-cleaned filterbank file at full time and frequency resolution, however. Folding it with the ephemeris expected for the candidate orbit, we obtained the trial mass ratio q. Furthermore, the candidate is not found at any other epoch. We therefore conclude that the visual notability of this candidate is due to a chance alignment of noise outliers in the low-resolution time-frequency plot (Fig. 1c). This diagnostic plot is composed of 64 profile bins by 64 subintegrations. The number of trials was much larger than this because it is spanned by the search ranges over period, period derivative, and mass ratio q. Based on experience in previous pulsar surveys (e.g., Coenen et al. 2014; van Leeuwen et al. 2020), 8σ chance outliers like this are common and are hardly ever confirmed.

|

Fig. 4. Frequency-phase plot of the flux density for the 42 ms candidate, folded taking the effects of the implied orbit into account. No significant periodic signal is seen. |

4. Discussion

We discuss the upper limits we obtained below (Sect. 4.1), the chances that the companion is a white dwarf or radio-quiet neutron star (Sects. 4.2 and 4.3), and the forecast for the visibility of a companion pulsar (Sects. 4.4 and 4.5).

4.1. Upper limit on the companion flux density

To estimate the upper limit on the source flux density (the minimum detectable flux density Smin), we used the standard radiometer equation for periodic narrow signals (following, e.g., van Leeuwen & Stappers 2010),

where βDF4 is the telescope degradation factor, S/Nmin is the S/N threshold for the pulsar detection, Tsys = Trec + Tsky is the overall system temperature, G is the telescope gain, np is the number of the polarization, Δν is the bandwidth of the observing frequency, tint is the integration time, and W and P are the pulse width and spin period of the pulsar, respectively. The effective pulse width W of a radio pulsar is broadened due to several effects (Mikhailov et al. 2017),

where W50/P is the pulsar duty cycle (isolated here because it varies less than W50 itself), tscat ≤ 0.01 ms is the scattering time, and tsamp = 0.049152 ms and tDM ≃ 0.11293 ms are the broadening and dispersion smearing of the sampling time, respectively. For cases when W ≳ P, Eq. (1) is no longer valid. Given the relatively high observing frequency and moderate DM, instrumental effects are unlikely to cause the effective width to exceed the period, and we discuss the influence of the intrinsic duty cycle on our search sensitivity below. We remain sensitive to any companions with a duty cycle longer than unity, which would appear as one diminished harmonic in the power spectrum, as we also searched for single-harmonic candidates (Sect. 2.2).

For FAST, the degradation factor βDF ≃ 1.5 and the total bandwidth Δν ≃ 400 MHz (after taking the channels excluded by RFI removal into account). For the most sensitive observation, we took the 4-hour observation on 1 July 2022 as an example. The zenith angle during this observation varied between 20° and 40°. Based on Jiang et al. (2020), we estimated the average G ≃ 15.6 K Jy−1 and Tsys ≃ 25.5 K. Consequently, for S/Nmin = 10 and a typical MSP duty cycle of W50/P = 0.10 (following Mikhailov et al. 2017), we find Smin ≃ 2.4 × 10−6 Jy.

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the system sensitivity for this most sensitive and for the least sensitive observation on 27 December 2023.

|

Fig. 5. FAST observation and performance evaluation for our observations. Panels (a) and (c) delineate the relation between telescope gain G, system temperature Tsys, and the zenith angle for the central beam (M01) at 1100 MHz, 1250 MHz, and 1400 MHz, respectively. The middle panel (b) shows the evolution of the zenith angle during our 20220701 4 h and 20231227 1.5 h observations. The estimated mean G and Tsys are indicated with vertical lines in panels (a) and (c). The FAST parameters were taken from Jiang et al. (2020). The evolution of the gain in panel (a) arises because the aperture efficiency is mostly unchanged until a zenith angle of 26.4° and then starts to decrease. For zenith angles larger than 15°, local side lobe RFI increases Tsys (c). |

Figure 6 next shows our search sensitivity limit Smin as a function of spin period P for the most and least sensitive cases and for W50/P values of 0.05, 0.10, and 0.30. Smin clearly increases when the pulsar spins very fast because the other factors in Eq. (2) start to dominate and effectively smear the pulse profile out. The fastest-spinning neutron star observed so far is PSR J1748−2446ad. Its spin frequency is 716 Hz (Hessels et al. 2006). One theoretical limit for the pulsar spin frequency is given by fmax ≃ 1045 (M/M⊙)1/2(10 km/R)3/2 Hz (Lattimer & Prakash 2004). For the companion of PSR J1906+0746, Mc = 1.322 M⊙, and R is most likely in the range 10−14 km (Özel & Freire 2016). Hence, we have a fmax ≃ 1202 Hz (or period 0.83 ms). This is, however, a mostly theoretical limit in our case. Binary evolution theory suggests that the companion that we searched for probably is an only mildly recycled pulsar, with a spin period most likely between 10 ms and 100 ms. Therefore, only the flat part of the Smin − P curves in Fig. 6 are used in furtherdiscussions.

|

Fig. 6. Search sensitivity limit as a function of the pulsar spin period P. We took the intrinsic W50/P to be 0.05, 0.10, and 0.30; the instrumental broadening and DM smearing were included when we calculated the effective pulse width. The vertical dashed line shows the fastest-spinning pulsar ever found. |

To place these limits in perspective, we converted them into a pseudo-luminosity, which we then compared with the known pulsar (sub)populations. This pseudo-luminosity Lpseudo = Smind2 depends on the pulsar distance d, which was determined to be  kpc from HI absorption (van Leeuwen et al. 2015; the earlier DM-based distance was ∼5.4 kpc). The search completeness as a function of Lpseudo is shown in Fig. 7. The cumulative distribution for all pulsars, all MSPs, and eight recycled pulsars in relativistic DNSs from Australia Telescope National Facility (ATNF) are plotted.

kpc from HI absorption (van Leeuwen et al. 2015; the earlier DM-based distance was ∼5.4 kpc). The search completeness as a function of Lpseudo is shown in Fig. 7. The cumulative distribution for all pulsars, all MSPs, and eight recycled pulsars in relativistic DNSs from Australia Telescope National Facility (ATNF) are plotted.

|

Fig. 7. Search completeness as a function of the pseudo-luminosity Lpseudo = Smind2. The cumulative distribution of Lpseudo for three (sub)sets of pulsars in the ATNF catalog are shown: all (blue), MSPs (P < 20 ms; purple), and recycled pulsars in relativistic DNS systems (black). To estimate the Lpseudo of the companion, we used the HI-absorption derived distance (7.4 kpc), we assumed an intrinsic W50/P of 0.10, and we considered the most (red) and least (gray) sensitive observations. For recycled pulsars in relativistic DNS systems, our search is 100% complete. For the general pulsar population, our search completeness exceeds 90%. |

For recycled pulsars in relativistic DNSs, which is the type of companion we expect, our search completeness Csearch (%) reaches 100%. This means even at this distance, we would have detected every known recycled pulsar in a relativistic DNSs. The general pulsar population also contains some faint pulsars with a Lpseudo below 0.1 mJy kpc2; we reach a Csearch (%) ≃ 94% for even the general population.

Based on these considerations, we conclude that no periodic pulsar signals are present in our data.

4.2. Possible explanations for the nondetection of the companion signal

Our nondetection again suggests that the companion is either not a neutron star (but a massive WD instead) or is a neutron star that does not emit radio emission. Alternatively, it might be a pulsar whose beam misses our LOS. The statistics of the last option are discussed in detail in the next section.

In the first option listed above, the PSR J1906+0746 system would contain a young pulsar with an older WD companion. As the most massive component of the original binary star system first explodes in a supernova and normally produces the most massive compact object, the most massive component in a relativistic binary is generally expected to be the oldest.

The young relativistic pulsar PSR J1141−6545 is on an eccentric orbit of ∼4.74 h, however, around an older 1.08 M⊙ WD companion (Venkatraman Krishnan et al. 2019). The companion was identified as a WD through its detection in the optical (Antoniadis et al. 2011). The temporal evolution of the orbital inclination of this pulsar indicates that the WD rotates fast (Venkatraman Krishnan et al. 2020). The companion of PSR J1906+0746 is significantly more massive, mc = 1.32 M⊙, and hence, it is more likely to be a neutron star. Based on this, PSR B2303+46 is another young pulsar and old WD system (van Kerkwijk & Kulkarni 1999); here, the WD mass is 1.3 M⊙. Based on the mass alone, the companion might still be an exceptionally massive WD. For a mildly recycled neutron star, the companion mass is well within the expected range (van Leeuwen et al. 2015), so that this remains more likely.

The eccentricity of PSR J1906+0746 (e = 0.085) is lower than that of the pulsar-WD systems PSR J1141−6545 (e = 0.172) and PSR B2303+46 (e = 0.658), but it is closer to that of the double pulsar PSR J0737−3039A (e = 0.088). This sample admittedly contains only a few systems, and the binary evolution history for these sources likely differs somewhat as well (see, e.g., Davies et al. 2002).

In the second option listed above, the companion is a neutron star that does not emit at all. The reason might be that it was mildly recycled, but then spun down until it again crossed the death line (cf. Fig. 8; also van Leeuwen & Verbunt 2004). This would signify a long delay between the formation of the two pulsars (PSR J1906+0746 is very young, after all, while the companion would need to be exceedingly old, > 1 Gyr), and some evidence supports this in the P−Ṗ diagram (Fig. 8). A number of mildly recycled pulsars (e.g., PSR J1518+4904, J1018−1523, and J1759+5036) have reached the death line, and none have been found beyond. This shows that this subpopulation eventually also switches off.

|

Fig. 8. P−Ṗ diagram. The distribution of different types of companions in the binaries is shown. The known pulsars in relativistic and/or DNS systems are labeled in the text with different colors. The diagram was made using psrqpy (Pitkin 2018) based on the pulsar catalog of the ATNF5 (Manchester et al. 2005). |

Other “radio-quiet” neutron stars have been hypothesized to never emit at all in radio (see Pastor-Marazuela et al. 2023, and references therein). This group, however, cannot be very large, as there arguably are already more radio-bright neutron stars than can be provided by the Galactic supernova rate.

We conclude that the companion might be a neutron star that does not emit at all. More likely, however, it does emit, but beamed away from us. We pursue this study further below after a brief discourse on the P−Ṗ diagram.

[5]https://www.atnf.csiro.au/research/pulsar/psrcat/

4.3. Further insights from the P−Ṗ diagram

In the P−Ṗ diagram (Fig. 8), the young normal pulsars in relativistic binaries stand out in the top right corners (marked with red names). These are the systems mentioned in Sect. 4.2, plus PSR J1755−2550, a relatively young pulsar with a similar eccentricity (e ∼ 0.089) as PSR J1906+0746, but a rather uncertain companion mass between 0.4 and 2.0 M⊙ (Ng et al. 2018). These sources are not recycled, and their active lifetimes are shorter than those of MSPs. Of these, PSR J1906+0746 is the youngest.

To allow us to focus our discussion on the relevant pulsars and companions, we followed the ATNF catalog (Manchester et al. 2005) and categorized the binary companions in this diagram into five species: neutron star, white dwarf, ultralight companion or planet, and main-sequence star. The known pulsars in relativistic and/or DNS systems (see van Leeuwen et al. 2015 and references therein) are labeled by text of different colors.

The sources with a neutron-star companion cluster between 20−100 ms (Fig. 8, blue markers). As this is where we also expect a pulsar companion to PSR J1906+0746, we focused on this period range (see Sect. 3.2.3). We did not detect a pulsar in our search, however. One of the best-known and most frequently studied systems in this cluster is the Hulse-Taylor binary, PSR B1913+16. In this system, the recycled pulsar is visible, but searches for the unrecycled younger pulsar were unsuccessful (see, e.g., Taylor et al. 1976). The visibility of the components in PSR B1913+16 therefore is the exact opposite of PSR J1906+0746. The nondetection of the companion to PSR B1913+16 can be explained by the same reasons that hold for a nondetected neutron-star companion to PSR J1906+0746; but as the unrecycled companion to PSR B1913+16 is expected to be relatively short lived, it is especially likely that it has passed the death line.

4.4. Probability that the companion is visible, and constraints on the viewing geometry

We estimated the probability that in a certain single moment, the companion might be visible from Earth as a function of magnetic inclination angles α and spin-orbit misalignment δ. The probability was calculated as the fraction of one precession cycle that the beam points at us. We assumed the total beam size in the latitudinal direction to be 40° for both main pulse (MP) and interpulse (IP) (as in Desvignes et al. 2019; Wang et al., in prep.) and that we observe using an ideal telescope (i.e., that we can always detect the pulsar when our LOS cuts through the beam). The probability contours for observing the two poles and at least one pole are shown in Fig. 9.

|

Fig. 9. Probability of seeing the companion at a single arbitrary time as a function of magnetic inclination angle α and spin-orbit misalignment δ. The orbital inclination angle i was fixed to 43.7°. Both α and δ are symmetrical about 90°; we therefore only show the [0°, 90°] × [0°, 90°] quadrant. For PSR J1906+0746, (α, δ) is (80.54°, 72.55°) from Wang et al. (in prep.). Its location is marked with a star. Upper panel: Probability of observing emission from at least one pole. Bottom panel: Probability of observing emission from the two poles. The assumptions here are (1) the beam extent in the latitudinal direction is 40° for MP and IP (equivalently, the impact parameter β is [−20°, 20°]); (2) we observe using an ideal telescope, and the probability is derived from a purely geometrical consideration. |

When δ = 0°, there is no practical effect from the geodetic precession; in this case, we can see the companion either always or never, depending on α. In general, when the second neutron star is formed, the mass loss and the kick associated with the supernova explosion will usually cause a misalignment between the spin axis of the existing recycled pulsar and the orbital angular momentum (Tauris et al. 2017). If this misalignment was significant (e.g., δ ≥ 20°), the recycled companion to PSR J1906+0746 might still become visible in the future. A range of misalignment angles were measured or suggested for similar systems. In one such system, PSR J0737−3039A, the angle is low, 3.2° (Ferdman et al. 2013), which suggests a symmetric supernova or one imparting a kick opposite to its pre-explosion orbital velocity (Willems & Kalogera 2004). On the other hand, Fonseca et al. (2014) reported the preferred angle for PSR B1534+12 as 27 ± 3°. Some subtle selection effect might be at play, however, because the recycled pulsar was discovered first in these cases, while in our case, the young pulsar was discovered first.

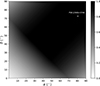

The precession rate of the presumed companion pulsar is ∼2.19° yr−1. Although the spin-orbit misalignment angle δ of the companion is unknown, we qualitatively constrained a number of general δ and α scenarios, based on the nondetections between 2006 and 2024. We calculated the evolution of the impact parameter β (the angle between the magnetic axis and the LOS) for the companion for different δ (0°, 5°, 20°, 50°, and 90°) and different values of α (0°, 45°, and 90°) using the Kramer & Wex (2009) precessional model. The results are shown in Fig. 10. This provides constraints on the viewing geometry if the companion is indeed a pulsar: When α is very small, δ is unconstrained (Fig. 10a); a moderate α (e.g. 45°) favors a large δ (≳50°), as visible in (Fig. 10b); while if the viewing geometry is nearly orthogonal, the current time span (∼7000 days) is not yet quite enough to constrain δ (Fig. 10c).

|

Fig. 10. Evolution of the impact angle β in one precession cycle for the putative companion pulsar for different magnetic inclination angles α and spin-orbit angles δ (0°, 5°, 20°, 50°, and 90°). In panel (a), α = 0°, in panel (b), the angle is 45°, and in panel (c), it is 90°. For panels (a) and (b), βMP and βIP are plotted using solid and dashed lines, respectively; for panel (c), the βMP and βIP curves coincide. The invisible β regions are filled with gray shadow. Since the reference precessional orbital phase Φ0 of the companion is unknown, the reference MJD0 is chosen to be the epoch that Φ0 = 0°. For reference, a scale bar that shows the observing duration of PSR J1906+0746 (∼7000 days) is plotted at the bottom of panel (a). This span can occur anywhere in the cycle. |

While this misalignment angle δ of the invisible companion is hard to determine a priori, some information can in principle be inferred from the eccentricity of the system, a quantity that can be determined from the visible binary component. This is so because the eccentricity and the misalignment angle are in large part determined by the supernova kick that created the second neutron star. In the double pulsar PSR J0737−3039A, for example, both are low (e = 0.088 and δ = 3.2°), while in PSR B1534+12, both are higher (e = 0.27 and δ = 27°). The low eccentricity of PSR J1906+0746 of e = 0.085 thus probably also influences the prior on the misalignment angle δ of its companion by some fraction that is currently unknown to us.

4.5. All-time beaming fraction of a precessing pulsar

The pulsar beaming fraction (the portion of the unit sky over which a pulsar is visible) has been studied in the past, especially in the context of pulsar energetics and population studies. This fraction was not studied before for a precessing pulsar, however. As the spin axis tilts, different parts of the sky are illuminated by the pulsar beam.

We considered a pulsar with a magnetic inclination angle α, misalignment δ, and a paddle beam with latitudinal radius ρ (cf. Wang et al., in prep.). The all-time beaming fraction fb, tot represents the fraction of the sky from which the precessing pulsar is visible at some point. It is the union of all instantaneous beaming fractions fb(t) at times t. This fb, tot is given by (sin θ2 − sinθ1)/2, where θ1, θ2 are the lower and upper latitudes of the illuminated strip in the orbital plane frame (where the Ltot aligns with the z direction), respectively. Figure 11 shows the values of fb, tot.

|

Fig. 11. All-time beaming fraction fb, tot of a precessing pulsar as a function of magnetic inclination angle α and spin-orbit misalignment δ. The latitudinal beam radius ρ is 20°. The location of PSR J1906+0746 in the α − δ space is marked as in Fig. 9. |

PSR J1906+0746 has an all-time sky coverage of one. This means that during one precession cycle, it will not only sweep over Earth (as we know), but also over all potential other observers. It can thus be discoverable from all directions at some point. It is apparent that α and δ are the determining factors for the all-time beaming fraction fb, tot: When a pulsar has a large combination of α + δ, it can illuminate almost the entire sky during one precessing cycle in O(102) years for typical DNS systems. this strongly suggests that if we continue to observe, we will eventually discover all these currently hidden pulsars.

5. Conclusion

In > 2 years of monthly highly sensitive FAST observation we did not detect pulsations from the companion of PSR J1906+0746. The mass of the companion fits a recycled neutron star best, but a massive white dwarf is not ruled out. This companion neutron star most likely emits in the radio, but its beam does not sweep across Earth. We find that for most combinations of the spin-orbit misalignment (very probably present, given the supernova kick likely imparted on PSR J1906+0746) and the magnetic inclination angle, we may well observe the companion pulsar at some time in the future. We conclude that it remains highly meaningful to extend the search we presented over a much longer time span.

We defer a single-pulse search to potential future work. While a number of MSPs emit giant pulses (GPs; see, e.g., Bilous et al. 2015 and references therein), all were discovered through their periodicity. One benefit of single-pulse searches is that they do not require orbital demodulation; but the downside is that GPs are often narrow and their signal-to-noise ratio (S/N).

Acknowledgments

We thank Alessandro Ridolfi for sharing pysolator. We thank Chenchen Miao and Pei Wang for assistance with the FAST data transfer, and Gregory Desvignes, Ingrid Stairs, Laila Vleeschower Calas, Ben Stappers, Michael Kramer, Di Li, and Weiwei Zhu for their support at various proposal stages. This research was supported by Vici research project “ARGO” (grant number 639.043.815), and through CORTEX (NWA.1160.18.316), under the research programme NWA-ORC; both financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO). This work has used the data from the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope (FAST) under proposals PT2021_0001, PT2022_0024 and PT2023_0010. FAST is a Chinese national mega-science facility, operated by the National Astronomical Observatories of Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC).

References

- Antoniadis, J., Bassa, C. G., Wex, N., Kramer, M., & Napiwotzki, R. 2011, MNRAS, 412, 580 [Google Scholar]

- Bilous, A. V., Pennucci, T. T., Demorest, P., & Ransom, S. M. 2015, ApJ, 803, 83 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burgay, M., D’Amico, N., Possenti, A., et al. 2003, Nature, 426, 531 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coenen, T., van Leeuwen, J., Hessels, J. W. T., et al. 2014, A&A, 570, A60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Damour, T., & Ruffini, R. 1974, C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris, 279, 971 [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M. B., Ritter, H., & King, A. 2002, MNRAS, 335, 369 [Google Scholar]

- Desvignes, G., Kramer, M., Lee, K., et al. 2019, Science, 365, 1013 [Google Scholar]

- Ferdman, R. D., Stairs, I. H., Kramer, M., et al. 2013, ApJ, 767, 85 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, E., Stairs, I. H., & Thorsett, S. E. 2014, ApJ, 787, 82 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hessels, J. W. T., Ransom, S. M., Stairs, I. H., et al. 2006, Science, 311, 1901 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P., Tang, N.-Y., Hou, L.-G., et al. 2020, RAA, 20, 064 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kargaltsev, O., & Pavlov, G. G. 2009, ApJ, 702, 433 [Google Scholar]

- Kasian, L. 2012, Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M., & Stairs, I. H. 2008, ARA&A, 46, 541 [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M., & Wex, N. 2009, Class. Quant. Grav., 26, 073001 [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, M., Stairs, I. H., Manchester, R. N., et al. 2006, Science, 314, 97 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lattimer, J. M., & Prakash, M. 2004, Science, 304, 536 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lorimer, D. R., Stairs, I. H., Freire, P. C., et al. 2006, ApJ, 640, 428 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lyne, A., & Graham-Smith, F. 2012, Pulsar Astronomy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Lyne, A. G., Burgay, M., Kramer, M., et al. 2004, Science, 303, 1153 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maan, Y., van Leeuwen, J., & Vohl, D. 2021, A&A, 650, A80 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Manchester, R. N., Hobbs, G. B., Teoh, A., & Hobbs, M. 2005, AJ, 129, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- Mikhailov, K., van Leeuwen, J., & Jonker, P. G. 2017, ApJ, 840, 9 [Google Scholar]

- Ng, C., Kruckow, M. U., Tauris, T. M., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 476, 4315 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Noutsos, A., Desvignes, G., Kramer, M., et al. 2020, A&A, 643, A143 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Özel, F., & Freire, P. 2016, ARA&A, 54, 401 [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Marazuela, I., Straal, S. M., van Leeuwen, J., & Kondratiev, V. I. 2023, A&A, 672, A151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Perera, B. B. P., McLaughlin, M. A., Kramer, M., et al. 2010, ApJ, 721, 1193 [Google Scholar]

- Pitkin, M. 2018, J. Open Source Softw., 3, 538 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ransom, S. 2011, Astrophysics Source Code Library [record ascl:1107.017] [Google Scholar]

- Ridolfi, A. 2020, Astrophysics Source Code Library [record ascl:2003.012] [Google Scholar]

- Tauris, T. M., Kramer, M., Freire, P. C. C., et al. 2017, ApJ, 846, 170 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, J. H., Hulse, R. A., Fowler, L. A., Gullahorn, G. E., & Rankin, J. M. 1976, ApJ, 206, L53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Kerkwijk, M. H., & Kulkarni, S. R. 1999, ApJ, 516, L25 [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, J., & Stappers, B. W. 2010, A&A, 509, 7 [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, J., & Verbunt, F. 2004, IAU Symp., 218, 41 [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, J., Cordes, J. M., Lorimer, D. R., et al. 2006, Chin. J. Astron. Astrophys., 6, 020 [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, J., Kasian, L., Stairs, I. H., et al. 2015, ApJ, 798, 118 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, J., Mikhailov, K., Keane, E., et al. 2020, A&A, 634, A3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman Krishnan, V., Bailes, M., van Straten, W., et al. 2019, ApJ, 873, L15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman Krishnan, V., Bailes, M., van Straten, W., et al. 2020, Science, 367, 577 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vleeschower, L. 2024, Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Manchester, UK [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Y. 2025, Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- Willems, B., & Kalogera, V. 2004, ApJ, 603, L101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.-Y., Zhang, C.-M., Li, D., et al. 2017, ApJ, 835, 185 [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. prepfold diagnostic plot. The candidate stands out when it displays a pulsar-like integrated profile (top subpanels; two rotations shown) and a near-constant period when it is demodulated at the orbit of the trial companion (bottom subpanels). Left (a): Candidate with a period of 2.059 s. Middle (b): Candidate with a period of 4.019 s. Right (c): Candidate with a period of 42 ms. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Flux density of the 2.059 s candidate against frequency and pulse phase, folded with dspsr. The zoom-in plot shows the origin of the falsified candidate: It is narrowband RFI around 1310 MHz. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. A zoom-in on the frequency range around the 4.019 s candidate. We show the flux density against frequency and pulse phase. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Frequency-phase plot of the flux density for the 42 ms candidate, folded taking the effects of the implied orbit into account. No significant periodic signal is seen. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. FAST observation and performance evaluation for our observations. Panels (a) and (c) delineate the relation between telescope gain G, system temperature Tsys, and the zenith angle for the central beam (M01) at 1100 MHz, 1250 MHz, and 1400 MHz, respectively. The middle panel (b) shows the evolution of the zenith angle during our 20220701 4 h and 20231227 1.5 h observations. The estimated mean G and Tsys are indicated with vertical lines in panels (a) and (c). The FAST parameters were taken from Jiang et al. (2020). The evolution of the gain in panel (a) arises because the aperture efficiency is mostly unchanged until a zenith angle of 26.4° and then starts to decrease. For zenith angles larger than 15°, local side lobe RFI increases Tsys (c). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Search sensitivity limit as a function of the pulsar spin period P. We took the intrinsic W50/P to be 0.05, 0.10, and 0.30; the instrumental broadening and DM smearing were included when we calculated the effective pulse width. The vertical dashed line shows the fastest-spinning pulsar ever found. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Search completeness as a function of the pseudo-luminosity Lpseudo = Smind2. The cumulative distribution of Lpseudo for three (sub)sets of pulsars in the ATNF catalog are shown: all (blue), MSPs (P < 20 ms; purple), and recycled pulsars in relativistic DNS systems (black). To estimate the Lpseudo of the companion, we used the HI-absorption derived distance (7.4 kpc), we assumed an intrinsic W50/P of 0.10, and we considered the most (red) and least (gray) sensitive observations. For recycled pulsars in relativistic DNS systems, our search is 100% complete. For the general pulsar population, our search completeness exceeds 90%. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. P−Ṗ diagram. The distribution of different types of companions in the binaries is shown. The known pulsars in relativistic and/or DNS systems are labeled in the text with different colors. The diagram was made using psrqpy (Pitkin 2018) based on the pulsar catalog of the ATNF5 (Manchester et al. 2005). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9. Probability of seeing the companion at a single arbitrary time as a function of magnetic inclination angle α and spin-orbit misalignment δ. The orbital inclination angle i was fixed to 43.7°. Both α and δ are symmetrical about 90°; we therefore only show the [0°, 90°] × [0°, 90°] quadrant. For PSR J1906+0746, (α, δ) is (80.54°, 72.55°) from Wang et al. (in prep.). Its location is marked with a star. Upper panel: Probability of observing emission from at least one pole. Bottom panel: Probability of observing emission from the two poles. The assumptions here are (1) the beam extent in the latitudinal direction is 40° for MP and IP (equivalently, the impact parameter β is [−20°, 20°]); (2) we observe using an ideal telescope, and the probability is derived from a purely geometrical consideration. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10. Evolution of the impact angle β in one precession cycle for the putative companion pulsar for different magnetic inclination angles α and spin-orbit angles δ (0°, 5°, 20°, 50°, and 90°). In panel (a), α = 0°, in panel (b), the angle is 45°, and in panel (c), it is 90°. For panels (a) and (b), βMP and βIP are plotted using solid and dashed lines, respectively; for panel (c), the βMP and βIP curves coincide. The invisible β regions are filled with gray shadow. Since the reference precessional orbital phase Φ0 of the companion is unknown, the reference MJD0 is chosen to be the epoch that Φ0 = 0°. For reference, a scale bar that shows the observing duration of PSR J1906+0746 (∼7000 days) is plotted at the bottom of panel (a). This span can occur anywhere in the cycle. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 11. All-time beaming fraction fb, tot of a precessing pulsar as a function of magnetic inclination angle α and spin-orbit misalignment δ. The latitudinal beam radius ρ is 20°. The location of PSR J1906+0746 in the α − δ space is marked as in Fig. 9. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.