| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A139 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555453 | |

| Published online | 05 December 2025 | |

Constraining the nature and Galactic origin of the Be binary MWC 656

New insights from VLA, Gaia, and Fermi-LAT

1

Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, D-53121 Bonn, Germany

2

Department of Geodesy and Geoinformation, Technische Universität Wien (TU Wien), Wiedner Hauptstraße 8-10, 1040 Vienna, Austria

⋆ Corresponding authors: sdzib@mpifr-bonn.mpg.de, frederic.jaron@tuwien.ac.at

Received:

8

May

2025

Accepted:

31

October

2025

The binary star MWC 656 was initially proposed as the first confirmed system composed of a Be star and a black hole (BH). However, recent studies have challenged this interpretation, suggesting that the compact companion is unlikely to be a BH. In this study, we revisited the nature of MWC 656 by analyzing archival data across multiple wavelengths, including radio observations from the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), optical astrometry from the Gaia satellite, and high-energy γ-ray data from the Fermi-LAT. Using all available VLA observations at the X band (8.0−12.0 GHz), we produced the deepest radio map toward this system to date, with a noise level of 780 nJy beam−1. The source MWC 656 was detected with Sν = 4.6 ± 0.8 μJy and a spectral index of α = 1.2 ± 1.8, derived by sub-band imaging. The radio-X-ray-luminosity ratio of MWC 656 is consistent with both the fundamental plane of accreting BHs and with the Güdel-Benz relation for magnetically active stars, leaving the emission mechanism ambiguous. The optical astrometric results of MWC 656 indicate a peculiar velocity of 11.2 ± 2.3 km s−1, discarding it as a runaway star. Its current location, 442 pc below the Galactic plane, implies a vertical travel time incompatible with the lifetime of a B1.5-type star. Moreover, the agreement between observed and expected motion in all three velocity components argues against a deceleration scenario, suggesting that MWC 656 likely formed in situ at high Galactic latitudes. We carried out a maximum-likelihood analysis of Fermi-LAT data, but we cannot report a significant detection of γ-ray emission from this source. These results reinforce recent evidence that challenge the BH companion interpretation, and favor a non-BH compact object such as a white dwarf or neutron star.

Key words: astrometry / proper motions / binaries: general / stars: emission-line / Be / stars: individual: MWC 656

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1. Introduction

Binary systems composed of a massive star and a compact object, i.e., a black hole (BH) or a neutron star (NS), are known as high-mass X-ray binaries (HMXBs). These systems are important laboratories for studying accretion physics, compact-object formation, and high-energy processes in stellar environments (e.g., Mirabel 2007). In classical HMXBs, accretion from the stellar wind or decretion disk of the massive star onto the compact object powers the observed X-ray and sometimes radio emission. If the compact object is a BH or an accreting NS, the high-energy emission is typically driven by accretion processes. In contrast, γ-ray binaries, an energetic subclass of HMXBs, are generally powered by the interaction between the relativistic wind of a young pulsar and the circumstellar material of a Be star (Dubus 2013). These systems exhibit orbital modulation across the electromagnetic spectrum, with γ-ray emission not driven by accretion, but by shock acceleration in the pulsar-disk interaction zone. Understanding the energy source in a given system is thus crucial for constraining the nature of the compact companion. However, only a handful of HMXBs have been firmly identified as γ-ray binaries, with a few others considered as candidates. One such candidate, and the subject of this article, is MWC 656 (also known as HD 215227), a binary system in a circular orbit with a period of 59.028 ± 0.002 days (Janssens et al. 2023). The primary is a Be star of spectral type B1.5–B2 III, and its projected rotational velocity (v sin i) has been measured to be approximately 330 km s−1 (Casares et al. 2014). The nature of the companion, as discussed below, has been a subject of debate during the last decade. The inclination of the system is estimated to lie between 30° and 80° based on modeling of the optical light curve and emission-line profiles.

Lucarelli et al. (2010) reported the detection of a new and previously unidentified point-like γ-ray source from a maximum-likelihood analysis of AGILE data “at a significance level above 5σ” at the Galactic position  , with a circular error of radius

, with a circular error of radius  . The AGILE source properties were consistent with it being a high-mass binary, pulsar, quasar, or supernova, but none of these objects were found in the area of the source. Williams et al. (2010) noted that the Be star MWC 656 falls in the position of the AGILE source and concluded that it is likely a binary star with a compact object as companion and, consequently, a strong candidate counterpart of the γ-ray source. These authors also noted that because of the large Galactic latitude position of MWC 656, it was possible that the supernova event that formed the compact companion could have kicked out the binary from the Galactic plane, making it a runaway star. However, the peculiar motions they found were inconclusive, given their large errors. A later study by Casares et al. (2014) estimated a mass range from 3.8 to 6.9 M⊙ for the compact companion in MWC 656, claiming it to be the first case of a Be star in a binary with a BH. Emerging evidence, however, disagrees with these results. In particular, Janssens et al. (2023) used a similar approach to that employed by Casares et al. (2014) and found that the companion is in the range from 0.6 to 2.4 M⊙, discarding the BH companion scenario and favoring instead a white dwarf, a neutron star, or a sub-dwarf O star (sdO) as the companion. Preliminary findings from Rivinius et al. (2024), presented at a recent conference proceedings, also support this trend, although a detailed peer-reviewed analysis is still pending.

. The AGILE source properties were consistent with it being a high-mass binary, pulsar, quasar, or supernova, but none of these objects were found in the area of the source. Williams et al. (2010) noted that the Be star MWC 656 falls in the position of the AGILE source and concluded that it is likely a binary star with a compact object as companion and, consequently, a strong candidate counterpart of the γ-ray source. These authors also noted that because of the large Galactic latitude position of MWC 656, it was possible that the supernova event that formed the compact companion could have kicked out the binary from the Galactic plane, making it a runaway star. However, the peculiar motions they found were inconclusive, given their large errors. A later study by Casares et al. (2014) estimated a mass range from 3.8 to 6.9 M⊙ for the compact companion in MWC 656, claiming it to be the first case of a Be star in a binary with a BH. Emerging evidence, however, disagrees with these results. In particular, Janssens et al. (2023) used a similar approach to that employed by Casares et al. (2014) and found that the companion is in the range from 0.6 to 2.4 M⊙, discarding the BH companion scenario and favoring instead a white dwarf, a neutron star, or a sub-dwarf O star (sdO) as the companion. Preliminary findings from Rivinius et al. (2024), presented at a recent conference proceedings, also support this trend, although a detailed peer-reviewed analysis is still pending.

The association of γ-ray emission with the source MWC 656 has been challenged by the fact that the initial detection with the AGILE satellite, reported in The Astronomer’s Telegram by Lucarelli et al. (2010), could not be confirmed by independent observations (e.g., with the Fermi-LAT). Alexander & McSwain (2015) revisited the AGILE observation by carrying out a maximum-likelihood analysis. They confirmed the detection of the γ-ray source by Lucarelli et al. (2010), albeit at a lower significance level of 3σ. These authors also analyzed photon data from the Fermi-LAT, but they did not report any detection of γ-ray flux from MWC 656 in these data. Instead, they reported the discovery of a previously undetected γ-ray source, which has entered the 3FGL Fermi-LAT source catalog as 3FGL J2201.7+5047 (Acero et al. 2015), but it is not included in the latest version of the 4FGL catalog anymore (Ballet et al. 2023). A confirmation of the 5σ AGILE detection of MWC 656 was provided by Munar-Adrover et al. (2016), along with several other events at a lower significance level (> 3σ). There is, however, not any relation of these events to the orbital phase of MWC 656. Also an analysis of Fermi-LAT data carried out by these authors did not result in any significant detection, analyzing the full energy range of the Fermi-LAT, i.e., 0.1−300 GeV.

In this work, we revisited the nature of MWC 656 by conducting a multiwavelength analysis using archival observations from the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA), Gaia, and Fermi-LAT. Our aim is to reassess previous claims regarding the system’s radio properties, kinematics, and possible γ-ray emission, in light of improved data and updated analysis tools. Through this comprehensive approach, we aim to clarify the physical nature of the compact companion and the high-energy characteristics of the system.

2. Data and analysis methods

In this section, we describe the datasets and analysis procedures used to investigate the properties of MWC 656. Our study is based on archival observations from the VLA, the Gaia satellite, and Fermi-LAT. The details of the data processing and analysis techniques are described in the following subsections.

2.1. VLA data analysis

The first radio detection of MWC 656 was reported by Dzib et al. (2015b, D15 hereafter) based on observations with the VLA in its B configuration. The instrument setup covered the full X band (8 to 12 GHz) in semi-continuum mode. Seven observations were carried out from February to April 2015, covering different orbital phases of the binary system. The duration of each observing session was two hours, which is very short compared to the ∼60-day orbital period of the system. The source was detected in their first epoch with a flux density of 14.2 ± 2.9 μJy, while analysis of the individual other six epochs yielded only upper limits (see their Table 1). By combining these six epochs (2−7), D15 determined a quiescent flux level of 3.7 ± 1.4 μJy.

In July 2015, the source MWC 656 was observed again with the VLA, this time by Ribó et al. (2017, R17 hereafter). These authors used the VLA in its A configuration and also observed the full X band in semi-continuum mode. This observing session lasted for six hours. They reported an unresolved source with a flux density of 3.5 ± 1.1 μJy, consistent with the result found by D15.

To improve the overall sensitivity level on VLA images, we proceeded to combine the observations by D15 and R17. This approach is valid because of the consistency in instrumental setup and also because the source is unresolved, minimizing dependence on the observed angular resolution (i.e., the VLA configuration).

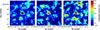

The data were calibrated using the CASA software (CASA Team 2022) following the calibration schemes described by D15 and R17. The imaging process was also carried out with CASA, and produced by combining the eight calibrated datasets. It used a natural weighting scheme with square pixels of 0 1 per side. Three final images were produced: (i) the full observed band, (ii) a lower side band (LSB) in the range from 8.0 to 10 GHz, and (iii) an upper side band (USB) covering the range from 10.0 to 12.0 GHz. During the cleaning process, the presence of a bright radio quasar on the west side of MWC 656 was taken into account (see also Moldón 2012). The resulting images are presented in Fig. 1.

1 per side. Three final images were produced: (i) the full observed band, (ii) a lower side band (LSB) in the range from 8.0 to 10 GHz, and (iii) an upper side band (USB) covering the range from 10.0 to 12.0 GHz. During the cleaning process, the presence of a bright radio quasar on the west side of MWC 656 was taken into account (see also Moldón 2012). The resulting images are presented in Fig. 1.

|

Fig. 1. MWC 656, as detected by combining all eight observed epochs in X band with VLA. (a) Image of full X band. (b) Image of LSB of X band, from 8.0 to 10.0 GHz. (c) Image of USB of X band, from 10.0 to 12.0 GHz. Contour levels are −3.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, and 5.4 the noise level of each image as listed in Table 1. The synthesized beam size, also as listed in Table 1, is shown as a white ellipse in the bottom left of each panel. |

2.2. Optical astrometry

The binary MWC 656 was identified in the Gaia DR3 catalog under the ID code 1982359580155628160 (Gaia Collaboration 2021). The measured parallax of 0.4860 ± 0.0185 mas is equivalent to a distance of 2.06 ± 0.08 kpc. This value represents a significant improvement over the commonly adopted distance for the system of 2.6 ± 1.0 kpc (Williams et al. 2010; Janssens et al. 2023). The Gaia proper motions are μα ⋅ cos(δ) = −3.478 ± 0.016 and μδ = −3.159 ± 0.017 mas yr−1. In Galactic coordinates, these proper motions are μℓ ⋅ cos(b) = −4.698 ± 0.018 and μb = −0.851 ± 0.017 mas yr−1. Additionally, the systemic radial velocity of MWC 656 is −14.1 ± 2.1 km s−1 (Casares et al. 2014).

To investigate whether MWC 656 exhibits evidence of high peculiar motion, as previously suggested by Williams et al. (2010), we analyzed its space motion relative to expectations from Galactic rotation. Although Fortin et al. (2022) previously examined the motion of MWC 656 from Gaia results, their study focused on interactions with large-scale Galactic structures and did not consider the runaway hypothesis.

The expected proper motion of MWC 656 can be estimated by adopting a simplified Galactic rotation model, in which stars in the Galactic disk move in circular orbits around the Galactic center. The coordinate system of this model is centered on the Galactic center (GC), the x-axis runs from the Sun to the GC, the y-axis is in the direction of Galactic rotation, and the z-axis is toward the north Galactic pole. We assumed a Local-Standard-of-Rest (LSR) speed of 254 km s−1 (Reid et al. 2009), and the Sun was located at a distance of 8.4 kpc from the GC (Reid et al. 2009). The solar motion relative to the LSR is taken to be (U, V, W) = (11.10, 12.24, 7.25) km s−1 (Schönrich et al. 2010).

Under these assumptions, the coordinates and heliocentric distance of MWC 656, we found a Galactic location of (x, y, z) = (−8755.4 ± 13.8, 1980.3 ± 76.9, − 442.3 ± 17.3) pc. Based on this location, the expected tangential proper motions of a star in this position are (μℓ ⋅ cos(b), μb)[expected]=(−4.30 ± 0.19, − 1.12 ± 0.15) mas yr−1, and with a systemic radial velocity of −24.3 ± 1.3 km s−1. Comparing these values with the values from optical studies, we found that the peculiar velocities of MWC 656 are (vℓ, vb, vrad)pec. = ( − 3.9 ± 1.8, + 2.5 ± 1.3, + 10.2 ± 2.5) km s−1, corresponding to a total peculiar velocity of 11.2 ± 2.3 km s−1.

An additional analysis was carried out to check the velocity difference of MWC 656 with respect to stars in its surroundings. Then, we used the data archive of Gaia and searched for stars within 10′ around the position of MWC 656 and with parallaxes between 0.455 mas (2.2 kpc) and 0.526 mas (1.9 kpc). To ensure high-quality astrometric results, we also constrained the results to stars with the renormalized unit weight error (RUWE1) parameter < 1.4 and parallax signal-to-noise ratio larger than 5. We found 62 stars with these criteria. Our analysis shows that the mean proper motions are −3.13 and −3.63 mas yr−1 in RA and Dec, respectively. Thus, the peculiar proper motions of MWC 656 with respect to its surrounding stars are −0.35 and 0.04 mas yr−1 equivalent to velocities of −3.4 and 0.4 km s−1.

2.3. Fermi-LAT data analysis

The Large Area Telescope (LAT) onboard the Fermi satellite (Fermi-LAT) has been taking data in all-sky monitoring mode since August 5, 2008 (Atwood et al. 2009). For the analysis presented here, we used data covering the period up to September 18, 2025, which represents a total dataset of 17.1 years. We used the Fermitools2 version 2.0.8 together with Fermitools-data version 0.18. We downloaded the Fermi-LAT Pass-8 photon data from the Fermi science support center3.

The data included photons from a circle of radius 15° around the position of MWC 656 and span an energy range from 0.1 to 300 GeV. We used the script make4FGLxml4 to generate a model from the 4FGL Fermi-LAT source catalog (Abdollahi et al. 2020). This initial model includes all sources that yield a 5σ significance over the integration time of the catalog. The fact that MWC 656 is not included in the catalog shows that this object is not detected as a source of γ-ray emission when combining all Fermi data. This excludes MWC 656 as a persistent γ-ray source, but transient emission is still a possibility, which we investigated with the approach described in the following.

The results presented in Munar-Adrover et al. (2016) suggest that the putative γ-ray source associated with MWC 656 has a power-law spectral shape with a photon index of γ = 2.3 ± 0.2 and is only detected up to 1 GeV of energy (see their Fig. 3). Based on these findings, we added a point source at the position of MWC 656 with a power law spectral shape to the model:

with the prefactor N0, photon index γ, and energy scale E0. We fixed the photon index to the value γ = 2.3 and left only the prefactor N0 free for the fit. Furthermore, the transient detections listed in Table 1 of Munar-Adrover et al. (2016) suggest that these events of γ-ray flares have a typical duration of 1−3 days. With this knowledge in mind, we divided the 17.1 years of available photon data into time bins of 2.9514 days, which is exactly Porb/20, adopting the updated orbital period of 59.028 d by Janssens et al. (2023). The aim of this choice is to simplify any analysis of possible orbital phase dependency of the results. We then performed an unbinned likelihood analysis in each of these 1931 time bins separately. We restricted the photon energy range to E = 0.1 − 1.0 GeV. Normalization factors of all sources within a radius of 5° were left free for the fit, and their spectral parameters were fixed to the catalog values. We used gll_iem_v07.fits as the model for the Galactic diffuse emission and iso_P8R3_SOURCE_V3_v1.txt as the template for the isotropic background emission. The prefactor and normalization were left free for the fit for these two components, respectively. We do not detect the source MWC 656 in any of these time bins. The largest test-statistic (TS) value that we obtain is 0.31, which is not even close to a value of nine, which would approximately correspond to a 3σ detection (Abdo et al. 2009). We also divided the Fermi data into ten orbital phase bins, according to the orbital period determined by Janssens et al. (2023) (i.e., the phase-bins had a width of 5.9028 d each) and performed the likelihood analysis in each of these bins. The source was not detected in any of these bins either.

3. Results and discussions

In this section, we present and discuss the results of our multiwavelength study of MWC 656, combining radio-continuum imaging with optical astrometry.

3.1. Radio properties of MWC 656

The combined dataset used to produce a new image of MWC 656 resulted in a detection with a flux density of 4.6 ± 0.8 μJy and signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 5.9, representing the most significant radio detection of the source to date. To test the robustness of the detection, we re-imaged the data excluding the first epoch from 2015, which corresponds to the brightest single detection reported by D15. The source is still clearly detected, with a flux density of 4.3 ± 0.8 μJy and a noise level of 0.84 μJy beam−1. These values are consistent with the full dataset, confirming that the detection is not driven by a single bright epoch. MWC 656 is also detected in the images of the two defined sub-bands, each with S/N ∼ 4.0. Details of the radio detections are given in Table 1.

MWC 656 and VLA image parameters.

We assume that the source flux density at these frequencies can be modeled as a power-law function of the form Sν ∝ ν+α, where α is the spectral index. Using the information provided by the two sub-bands, with central frequencies of 9.0 GHz and 11.0 GHz, we estimated the spectral index to be α = 1.2 ± 1.8.

We emphasize that the uncertainty of the spectral index is large (±1.8), such that optically thin synchrotron emission (e.g., α ≈ −0.6) lies well within 1σ. Therefore, no specific emission mechanism can be confidently favored or excluded based on the spectral slope alone. The nominal value, however, is marginally consistent with a flat or mildly inverted spectrum. In a microquasar scenario, such a radio spectrum is typical of accreting BHs in a low-hard X-ray state (Fender et al. 2004). The X-ray properties of MWC 656 found by Ribó et al. (2017) are indeed compatible with a BH in deep quiescence, as these authors point out. However, this interpretation is increasingly disfavored in light of recent MWC 656 mass estimates.

If the compact star is not a BH, as recent observations suggest, then there is still the possibility of an accreting neutron star (NS), which could explain the observed radio and X-ray properties. However, as Janssens et al. (2023) pointed out, the radio emission from Be + NS binaries has not yet been explored in the regime of such low X-ray luminosities (van den Eijnden et al. 2021). If the radio emission from MWC 656 is confirmed to originate in a jet, then, according to Massi & Kaufman Bernadó (2008), this would put constraints on the magnetic field of a neutron star in this system (see, however, van den Eijnden et al. 2021).

The monochromatic radio luminosity of MWC 656 at the observed frequency is Lν = 2.6 × 1016 erg s−1 Hz−1, adopting a distance of 2.06 kpc. The total radio luminosity at the observed bandwidth can be estimated by assuming a flat spectrum to be Lradio = 1.04 × 1026 erg s−1. On the other hand, the X-ray luminosity reported by R17 translates to LX = 1.95 × 1030 erg s−1, after rescaling it to the MWC 656 distance of 2.06 kpc assumed in this work. These values remain consistent with MWC 656 lying in the so-called fundamental plane of accreting BHs (Merloni et al. 2003; Gallo et al. 2006; Plotkin et al. 2017), but on the faint edge, as previously noted by D15 and R17. However, we note that the radio-X-ray-luminosity ratio of (LX/Lν)MWC656 = 7.5 × 1013 Hz−1 is also broadly consistent with values reported for magnetically active young stars, as described by the Güdel-Benz relation (Guedel & Benz 1993; Dzib et al. 2015a; Yanza et al. 2022). Given the current data, the origin of the radio emission remains ambiguous, and both accretion- and magnetically driven scenarios should be considered.

3.2. Astrometry

Runaway stars are defined as stars moving at high velocities, usually above 30 to 40 km s−1, relative to the LSR velocity (Moffat et al. 1998; Hoogerwerf et al. 2001). In the case of MWC 656, we derived a total peculiar velocity of 11.2 ± 2.3 km s−1, which is well below this threshold. Furthermore, the peculiar velocity of MWC 656 relative to the local stars is 3.4 km s−1. Both results confirm that the system does not meet the conventional criteria for classification as a runaway star.

The celestial coordinates and heliocentric distance of MWC 656 indicate that it is at 442 pc below the Galactic plane. Assuming that the system originated in the Galactic plane and has been continuously moving away at its present vertical velocity, derived from the Galactic proper motion μb = −0.851 ± 0.017 mas yr−1 (corresponding to vb = 8.30 ± 0.17 km s−1), it would require approximately 52 million years to reach its current altitude. This timescale is 3.5 times the main-sequence lifetime of a B1.5-type star, which is typically less than 15 million years (e.g., Ekström et al. 2012; Brott et al. 2011). This discrepancy suggests that a birth in the Galactic plane is unlikely. Moreover, the fact that the system’s velocity components in Galactic longitude, latitude, and radial directions all agree with expectations from Galactic rotation makes a deceleration scenario unlikely, as it would require simultaneous energy loss along all axes.

Fortin et al. (2022) found no evidence of interaction between the MWC 656 system and any spiral arms or open clusters, and they suggested that it may have formed in isolation. Our results support this interpretation, though with a different emphasis. The proper motion and radial velocity of MWC 656 are in good agreement with the predictions of a standard Galactic-rotation model. This implies that the system has likely not migrated far from its birthplace, and raises the possibility that it formed in situ at a significant height above the Galactic plane (i.e., outside the thin disk). Compared to earlier estimates with large uncertainties (e.g., Williams et al. 2010), our use of Gaia DR3 proper motions and updated radial velocity enables a significantly more precise derivation of the system’s peculiar motion. This precision effectively rules out a runaway scenario and reinforces the conclusion that the system likely formed at its current position, a result not accessible in earlier studies.

3.3. The nature of the MWC 656 companion

The potential in situ formation of MWC 656 at a high Galactic latitude (442 pc below the plane) invites further reflection on the evolutionary history of the system. Star formation far from the Galactic plane is relatively rare and typically limited to low-density regions with few massive stellar clusters. These conditions are unfavorable for the formation of very massive stars, and thus for BH progenitors. In contrast, the long-term evolution of intermediate-mass binaries –including episodes of mass transfer and common envelope evolution– may more plausibly result in the formation of white dwarfs or NSs. Moreover, the low peculiar velocity of MWC 656 argues against a strong natal kick, which would be more characteristic of a supernova that forms a NS or BH. Taken together, these environmental and kinematic arguments suggest that a compact companion may indeed be present, but likely not a BH.

Additional clues arise from the observed radio and X-ray emission. While such emission is often interpreted as a signature of accretion onto a compact object, the radio-X-ray-luminosity ratio of MWC 656 is also consistent with the Güdel-Benz relation, which characterizes magnetically active stars (Guedel & Benz 1993; Dzib et al. 2015a; Yanza et al. 2022). This opens the possibility that the emission originates from a low-mass pre-main-sequence or main-sequence star with a magnetically heated corona, rather than from an accreting compact object. Thus, the presence of X-ray and radio emission does not conclusively establish the nature of the companion. However, not all companion types are equally consistent with the available constraints. The orbital solution implies a companion mass between 0.6 and 2.4 M⊙ (Janssens et al. 2023), and no optical contribution from a secondary is detected (Casares et al. 2014; Janssens et al. 2023). These conditions disfavor mid- or high-mass main-sequence stars. A low-mass stellar companion remains viable, but it would require a specific inclination and evolutionary scenario to remain undetected. A white dwarf or a NS, both optically faint and radio and X-ray active under certain conditions, offers a more natural explanation. While the identity of the companion cannot yet be definitively determined, the combined astrometric, photometric, and radiative evidence favors a non-BH compact object.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we revisited the nature of the MWC 656 system with radio interferometry, optical astrometry from Gaia, and high-energy γ-ray data from Fermi-LAT. Our conclusions are listed below.

-

Combining the VLA datasets from Dzib et al. (2015b) and Ribó et al. (2017) improves the significance of the radio detection to 5.9σ, which is thereby confirmed and strengthened.

-

The estimated spectral index (S ∝ ν+α) of the radio emission is α = 1.2 ± 1.8. Although uncertain, its nominal value tentatively indicates a flat or inverted spectrum, which would be compatible with an accreting compact object (NS or BH) in quiescence. However, given the large uncertainty of α, the origin of the radio emission remains ambiguous.

-

The comparisons of radio and X-ray luminosities are consistent with both the fundamental plane of accreting BHs and with the Güdel-Benz relation for magnetically active stars. Then, the relation of these wavelengths is also ambiguous in this case.

-

The measured proper motions and radial velocity of MWC 656 are consistent with Galactic rotation and imply a peculiar velocity well below the threshold for runaway stars. This argues against a runaway origin for the system.

-

A maximum-likelihood analysis of Fermi-LAT data does not result in any detection of γ-ray emission from the region where MWC 656 is located.

Although MWC 656 was previously proposed as the first Be+BH binary, recent evidence has cast doubt on this scenario. Our results further support this re-evaluation, particularly by excluding a runaway origin based on the kinematics of the system and by finding no evidence for associated γ-ray emission in the Fermi-LAT data. Nevertheless, the large vertical distance of MWC 656 (442 pc) from the Galactic plane remains puzzling, especially given the lack of nearby regions of star formation at such Galactic latitudes. The origin of MWC 656 thus remains unclear and may point toward atypical or isolated formation pathways outside the thin disk.

Available from https://github.com/fermi-lat/Fermitools-conda

Downloaded from the user contributions section of the Fermi science support center: https://fermi.gsfc.nasa.gov/ssc/data/analysis/user/

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous referee for their thoughtful comments that helped improve this paper. We thank M. Massi and E. Ros for useful discussions and suggestions. S.A.D. acknowledges the M2FINDERS project from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant No. 101018682). This work has made use of public Fermi data obtained from the High Energy Astrophysics Science Archive Research Center (HEASARC), provided by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. The computational results presented have been achieved [in part] using the Vienna Scientific Cluster (VSC). This research was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) [P31625]. The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

References

- Abdo, A. A., Ackermann, M., Ajello, M., et al. 2009, ApJS, 183, 46 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Abdollahi, S., Acero, F., Ackermann, M., et al. 2020, ApJS, 247, 33 [Google Scholar]

- Acero, F., Ackermann, M., Ajello, M., et al. 2015, ApJS, 218, 23 [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. J., & McSwain, M. V. 2015, MNRAS, 449, 1686 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood, W. B., Abdo, A. A., Ackermann, M., et al. 2009, ApJ, 697, 1071 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ballet, J., Bruel, P., Burnett, T. H., Lott, B., & The Fermi-LAT Collaboration 2023, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2307.12546] [Google Scholar]

- Brott, I., de Mink, S. E., Cantiello, M., et al. 2011, A&A, 530, A115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- CASA Team (Bean, B., et al.) 2022, PASP, 134, 114501 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Casares, J., Negueruela, I., Ribó, M., et al. 2014, Nature, 505, 378 [Google Scholar]

- Dubus, G. 2013, A&ARv, 21, 64 [Google Scholar]

- Dzib, S. A., Loinard, L., Rodríguez, L. F., et al. 2015a, ApJ, 801, 91 [Google Scholar]

- Dzib, S. A., Massi, M., & Jaron, F. 2015b, A&A, 580, L6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ekström, S., Georgy, C., Eggenberger, P., et al. 2012, A&A, 537, A146 [Google Scholar]

- Fender, R. P., Belloni, T. M., & Gallo, E. 2004, MNRAS, 355, 1105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, F., García, F., & Chaty, S. 2022, A&A, 665, A69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration (Brown, A. G. A., et al.) 2021, A&A, 649, A1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, E., Fender, R. P., Miller-Jones, J. C. A., et al. 2006, MNRAS, 370, 1351 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guedel, M., & Benz, A. O. 1993, ApJ, 405, L63 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogerwerf, R., de Bruijne, J. H. J., & de Zeeuw, P. T. 2001, A&A, 365, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens, S., Shenar, T., Degenaar, N., et al. 2023, A&A, 677, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lucarelli, F., Verrecchia, F., Striani, E., et al. 2010, ATel, 2761, 1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Massi, M., & Kaufman Bernadó, M. 2008, A&A, 477, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Merloni, A., Heinz, S., & di Matteo, T. 2003, MNRAS, 345, 1057 [Google Scholar]

- Mirabel, I. F. 2007, Ap&SS, 309, 267 [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, A. F. J., Marchenko, S. V., Seggewiss, W., et al. 1998, A&A, 331, 949 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Moldón, F. J. 2012, Ph.D. Thesis, University of Barcelona, Spain [Google Scholar]

- Munar-Adrover, P., Sabatini, S., Piano, G., et al. 2016, ApJ, 829, 101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin, R. M., Miller-Jones, J. C. A., Gallo, E., et al. 2017, ApJ, 834, 104 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reid, M. J., Menten, K. M., Zheng, X. W., et al. 2009, ApJ, 700, 137 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ribó, M., Munar-Adrover, P., Paredes, J. M., et al. 2017, ApJ, 835, L33 [Google Scholar]

- Rivinius, T., Klement, R., Chojnowski, S. D., et al. 2024, IAU Symp., 361, 332 [Google Scholar]

- Schönrich, R., Binney, J., & Dehnen, W. 2010, MNRAS, 403, 1829 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van den Eijnden, J., Degenaar, N., Russell, T. D., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 507, 3899 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, S. J., Gies, D. R., Matson, R. A., et al. 2010, ApJ, 723, L93 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yanza, V., Masqué, J. M., Dzib, S. A., et al. 2022, AJ, 163, 276 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. MWC 656, as detected by combining all eight observed epochs in X band with VLA. (a) Image of full X band. (b) Image of LSB of X band, from 8.0 to 10.0 GHz. (c) Image of USB of X band, from 10.0 to 12.0 GHz. Contour levels are −3.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, and 5.4 the noise level of each image as listed in Table 1. The synthesized beam size, also as listed in Table 1, is shown as a white ellipse in the bottom left of each panel. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.