| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A27 | |

| Number of page(s) | 22 | |

| Section | Planets, planetary systems, and small bodies | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556262 | |

| Published online | 05 December 2025 | |

DIPSY: A new Disc Instability Population SYnthesis

I. Modelling, evolution of individual systems, and tests

1

Space Research and Planetary Sciences, Physics Institute, University of Bern,

Gesellschaftsstrasse 6,

3012

Bern,

Switzerland

2

Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern,

Gesellschaftsstrasse 6,

3012

Bern,

Switzerland

3

Department of Astrophysics, Universität Zürich,

Winterthurerstrasse 190,

8057

Zürich,

Switzerland

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

4

July

2025

Accepted:

10

September

2025

Context. Disc instability (DI) is a model aimed at explaining the formation of companions through the fragmentation of the circum-stellar gas disc. Furthermore, DI could explain the formation of part of the observed exoplanetary population. Our understanding of DI is still incomplete given the complex nature of the process and challenges related to its modelling.

Aims. We aim to provide a new comprehensive global model for the formation of companions via DI. The model includes the formation of the star-and-disc system through infall from the molecular cloud core (MCC) as well as the evolution of companions that might emerge via fragmentation in it. This approach allows us to study a large parameter space, perform population synthesis calculations, and make predictions that can be compared with observations. This makes it possible to put the models for the different sub-processes included in the global model to the observational test.

Methods. We have developed a global formation and evolution model for companions formed via DI: DIPSY. The model solves the 1D vertically integrated viscous evolution equation of the protostellar and protoplanetary disc with a variable α viscosity. It includes infall from the MCC, stellar irradiation, internal and external photoevaporation, and exchange of both mass and angular momentum between disc and companions. The latter leads for the companions to orbital migration and damping of the eccentricities and inclinations. As it evolves, the disc is continuously monitored for self-gravity and fragmentation. When the conditions are satisfied, one (or several) clumps are inserted. The evolution of the clumps is then followed in detail. Clump contraction, including the second collapse is considered by using interior evolution tracks. Thermal irradiation by the disc, mass growth by gas accretion, and mass loss via Roche lobe overflow are also included. The interaction of clumps with each other is included with a full N-body integrator which can lead to collisions, scattering, or ejections.

Results. We showcased the model by performing a number of simulations for various initial conditions, from simple non-fragmenting systems to complex systems with many fragments.

Conclusions. We confirm that the DIPSY model is a comprehensive and versatile global model of companion formation via DI. It enables studies of the formation of companions with planetary to low stellar masses around primaries with final masses that range from the brown dwarf to the B-star regime. We conclude that it is necessary to consider the many interconnected processes such as gas accretion, orbital migration, and N-body interactions, as they strongly influence the inferred population of forming objects. It is also clear that model assumptions play a key role in the determination of the systems undergoing formation.

Key words: planets and satellites: dynamical evolution and stability / planets and satellites: formation / planets and satellites: gaseous planets / protoplanetary disks / planet–disk interactions

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Planet formation occurs in discs around young stars and two main pathways for this process have been proposed: core accretion (CA, Safronov 1972; Pollack et al. 1996; Hubickyj et al. 2005; Alibert et al. 2005) and disc instability (DI, Kuiper 1951; Mizuno et al. 1978; Cameron 1978; Boss 1997, 2003). In the case of DI (also known as gravitational instability, GI), a cir-cumstellar disc fragments under its own gravity to form one or several gravitationally bound objects. These so called ‘clumps’ have masses of the order of 1 Jovian mass, sizes of ~ 1 au (astronomical unit), and they are close to hydrostatic equilibrium. The subsequent evolution of the clumps determines whether they survive and become compact companions. Companions formed this way can lie in the planetary, brown dwarf, or stellar mass regime.

This includes a number of physical processes that are discussed in detail below.

Originally, DI was proposed as a model for the formation of the Solar System (Kuiper 1951). It was later superseded by CA as the standard model for planet formation, due to a number of (potential) limitations. We review these limitations in the following and discuss their relevance.

One of these limitations is very rapid inward migration. Baruteau et al. (2011) studied the migration of massive planets in gravito-turbulent discs in 2D hydrodynamic simulations, including self-gravity. They found that these objects migrate to the inner disc on a type I timescale, without opening a gap. It was therefore concluded that these planets are unlikely to remain at large separations, at least for the underlying model assumptions (simplified cooling prescription and only a single planet per system). More recently, Rowther & Meru (2020) performed 3D self-gravitating smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) simulations of single migrating planets in gravitationally unstable discs. They applied a variable cooling parameter to account for the expected longer cooling time in the inner disc. The authors found that this effect enables planets to open a gap as soon as they reach the gravitationally stable region in the inner disc; thus, they are able to survive on long timescales. Both studies, however, neglected the effect of additional companions. Gravitational interactions between these companions could also facilitate the survival of at least some objects (Emsenhuber et al. 2021a).

Another related limitation is tidal destruction by Roche lobe overflow (e.g. Kratter & Murray-Clay 2011). When a clump moves close to the primary due to migration or it approaches is periapsis on an eccentric orbit, it can be tidally disrupted (see also Sect. 3.6). Whether this occurs depends on the clump evolution (size and mass). As a clump contracts (Sect. 3.4, its temperature rises. Once the central temperature exceeds ≈2000Κ, the clump undergoes a dynamical collapse (corresponding to the second collapse in star formation), which makes it stable against tidal disruption (Bodenheimer 1974). The pre-collapse timescale depends strongly on the clump’s mass, with massive clumps collapsing sooner (Helled & Bodenheimer 2011). Gas accretion can also shorten this timescale (Vazan & Helled 2012). Furthermore, tidal destruction can be avoided if the planet does not move too close to the primary, which can happen if it opens a gap (e.g. Rowther & Meru 2020). Similarly, a clump could become unbound and dissolve again due to irradiation from its environment (i.e. the thermal bath effect, Vazan & Helled 2012). This fate could be avoided if the clump contracts fast enough.

An additional limitation of DI sometimes brought forward is that it would not be able to form a heavy-element core. While this is not specifically required, core formation is certainly a possibility in a clump (Decampli & Cameron 1979; Boss 1998; Baehr & Klahr 2019). Helled & Schubert (2008) investigated the sedimentation of silicate grains inside isolated clumps of different masses. They found that protoplanets with masses below 5M4 (Jovian masses) allow for grain sedimentation and core formation, while more massive ones are hotter and in such cases, core formation via grain settling would not be possible. However, cores in more massive clumps could be a result of fragmentation near spiral arms where dust is accumulated (Baehr & Klahr 2019). The accretion of heavy elements post formation could further support this process (Helled et al. 2006).

Another important challenge in studying DI is the computational cost. The huge density contrast between the circumstellar disc and the clump’s interior is very challenging numerically when studying fragmenting discs (Boley et al. 2010; Galvagni et al. 2012). Advanced hydrodynamical codes are expected to allow for progress in this area in the future (see e.g. Matzkevich et al. 2024).

However, none of these limitations alone are expected to prevent the formation of companions in DI in a general way. Still, at present, these limitations in our understanding of several physical processes occurring during DI are significant. One way to make progress in to create more realistic model companion formation in the DI scenarios in the future by combining models of the relevant physical processes and including their interplay into a global model. This output can then be confronted with observational results. Differences between these global model predictions and the observations can then be used to constrain the underlying specialized models and eventually improve our understanding. This is our aim in constructing the model presented in this work.

In recent years, DI has again received growing interest as the number of planetary mass companions on wide orbits has increased (Kratter et al. 2010b; Nielsen et al. 2019). Other classes of planets that are difficult to explain in the classical CA paradigm have also been identified. These include giant planets around very low-mass stars, such as GJ 3512 b (Morales et al. 2019; Kurtovic et al. 2021; Mercer & Stamatellos 2020), and massive planets in very young systems, possibly including AB Aur b (Currie et al. 2022). Overall, CA has been studied extensively, also on a population level (Ida & Lin 2004; Emsenhuber et al. 2021b, see also the reviews in Benz et al. 2014; Mordasini 2018; Burn & Mordasini 2024). Population synthesis projects also exist in the disc instability paradigm (Forgan et al. 2018; Nayakshin & Fletcher 2015). However, these projects are often less mature and/or do not include all the relevant physical processes. Disc instability is expected to mainly populate the brown dwarf (BD) and stellar mass regime (e.g. Rafikov 2005; Kratter et al. 2010a,b; Rice et al. 2015; Xu et al. 2025). The exact shape of the population formed in DI is still unknown. In particular, it is unclear to what extent DI has the capacity to form planetary-mass objects.

A numerical model that includes as many of the relevant physical processes as possible is needed to answer these questions. In particular, it is important to include the early phase of disc formation in a collapsing molecular cloud core (MCC). Here, we present a new global model for Disc Instability Population SYnthesis (DIPSY) that includes a number of improvements over previous global models. While being rich in physical mechanism, it is low-dimensional numerically, so that it can still be used to make quantitative statistical predictions that can be compared to observations. We built on previous works, where an earlier version of the model was used in population syntheses of circumstellar discs (Schib et al. 2021, 2023). The current large model update introduces clumps into the disc if the conditions for fragmentation are satisfied and follows their evolution in detail.

This is the first of a series of papers. In Schib et al. (2025) (Paper II), we applied this model to perform a large-scale population synthesis. The current paper is organised as follows. In Sect. 2, we describe the model for the primary star and the cir-cumstellar disc, including the formation stage through infall, the transport of angular momentum, the treatment of self-gravity, the evolution of the central star, and the temperature model. Section 3 details the treatment of fragmentation as well as the evolution of the clumps. This includes the initial clump mass, mass growth by gas accretion, clump contraction, disc irradiation of the clumps, and mass loss. In Sect. 4, we discuss the exchange of angular momentum with the disc (leading to orbital migration and eccentricity+inclination damping) as well as gravitational interactions among clumps (N-body). Section 5 demonstrates the capabilities of the model by presenting and discussing several systems of varying complexity. In Sect. 6, we discuss the assumptions and limitations of the model. We present a summary and our conclusions in Sect. 7.

2 Disc model

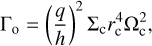

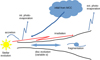

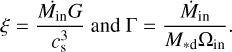

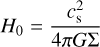

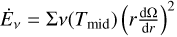

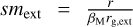

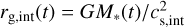

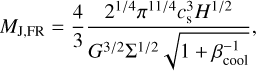

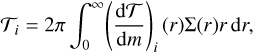

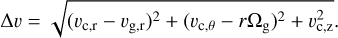

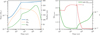

The disc model yields a description for the formation and evolution of the circumstellar disc and forms a central part of the overall global model. Figure 1 gives a schematic overview of the processes occurring in the disc. As illustrated in the figure, the model includes the time evolution of the disc and the primary star. The star and the disc interact via accretion, irradiation, and internal photoevaporation. The disc further interacts with the environment by infall from the MCC and external photoevaporation.

Adaptations of the disc model used in this work were already employed in previous work: Schib et al. (2021, 2022, 2023). We refer to these papers as S21, S22, and S23. Here, we use a modified and extended version, as described below. While we focus on the new aspects of the model, for completeness, we describe all the relevant elements of the model. We used cylindrical polar coordinates, with r denoting the radial direction (distance from the star). We considered a single primary star of (variable) mass M* at the origin. The heliocentric disc’s mid-plane is located at z = 0au. The disc is assumed to be rotationally symmetric and is described via the vertically integrated surface density, Σ ≡ Σ(r, t), which evolves with time t (Sect. 2.1). The simulations do not start from a fully formed star-and-disc system. Instead, the star and disc are initialised with a negligible mass and are fed by infalling material from the MCC (Sect. 2.5). The star is evolved according to pre-calculated stellar evolution tracks (Sect. 2.4).

The disc is assumed to be subject to internal EUV as well as external FUV photoevaporation. Together with accretion, this ultimately leads to the disc’s dispersal (Sect. 2.7).

|

Fig. 1 Schematic representation of the star and disc system, including its physical processes. |

2.1 Disc evolution

The evolution of the disc’s surface density Σ is calculated by solving the diffusion equation (Lüst 1952 and Lynden-Bell & Pringle 1974):

![${{\partial \Sigma } \over {\partial t}} = {1 \over r}{\partial \over {\partial r}}\left[ {3{r^{1/2}}{\partial \over {\partial r}}\left( {v\Sigma {r^{1/2}}} \right) - {{2\Lambda \Sigma } \over \Omega }} \right] + S.$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq1.png) (1)

(1)

The quantity ν denotes the kinematic viscosity. We applied the alpha-parametrisation (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973, Sect. 2.2). Then, Λ is the torque density distribution used to describe the two-way exchange of angular momentum between the disc and companions (Sect. 4.1). The angular frequency, Ω ≡ Q(r, t), includes a contribution from the disc’s auto-gravitation (Sect. 2.3). S ≡ S (r, t) stands for a source and sink term:

(2)

(2)

The contributions to S are: Sinf the source term for the infalling material from the MCC (Sect. 2.5), Sevap the sink term for photoevaporation (Sect. 2.7), Sacc the sink term for mass accreted by companions (Sect. 3.3) and Sloss the source term for mass returned to the disc by companions undergoing mass loss (Sect. 3.6). Equation (1) is solved using the implicit donor cell advection-diffusion scheme with piecewise constant values from Birnstiel et al. (2010). We used a grid with 2800 logarithmically space grid points extending from 3 × 10−2 au to 3 × 104 au. At the inner edge, the disc is truncated at 0.05 au. The mass flowing across the truncation radius is added to the star, with 10 % considered lost in outflows (Vorobyov 2010).

2.2 Viscosity

The kinematic viscosity ν is parametrised as (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973):

(3)

(3)

where cs is the isothermal sound speed:

(4)

(4)

Here, kB denotes the Boltzmann constant, T is the disc’s mid-plane temperature (Sect. 2.6), μ ≡ 2.3 is the mean molecular weight and u is the atomic mass unit. For the calculation of α, we considered different regimes as described below.

2.2.1 Global instability of the disc

At early times, the disc is supplied by infalling material from the MCC and can become comparable in mass to the star. In this regime, a global gravitational instability can occur (e.g. Harsono et al. 2011). Kratter et al. (2010a)1 performed a parameter study of rapid accretion in a series of grid-based 3D hydrodynamic simulations. Their results indicated that the disc’s behaviour can be characterised by two dimensionless parameters, ξ and Γ. They parametrised α in the regime in question as follows:

(5)

(5)

We applied this prescription during the infall phase and follow the authors by setting kΣ = 3/2 and lj = 1. The parameters ξ (relating the mass accretion rate of infall to the disc’s sound speed) and Γ (relating the accretion timescale of the infalling gas to its orbital timescale) are given by:

(6)

(6)

Here, Ṁin is the infall rate, M*d the combined mass of the star and the disc, and Ωin the angular frequency of the infalling gas at the location where it hits the disc. The sound speed, cs, is also evaluated at the same location; ξ and Γ are calculated at each time step in our model. This makes αd constant in r but varying in time.

2.2.2 Transport of angular momentum by spiral arms

Once the infall phase has ended, the prescription from Sect. 2.2.1 is no longer applicable (ξ = 0). However, the disc can still be sufficiently massive to be self-gravitating. In this regime, the transport of angular momentum is governed by spiral arms. We applied the following parametrisation (Zhu et al. 2010; Kimura et al. 2016):

(7)

(7)

by setting α globally and using the minimum of QToomre (given in Eq. (28)) across the disc. This treatment may somewhat over-predict the transport of angular momentum through spiral arms. We found that using a radially varying prescription (see also Kratter et al. 2008) leads to pile-ups of material outside of the unstable regions, which can cause an extreme number of fragmentation event (given that we already observed ~100 events in some cases). Therefore, in this work, we kept the assumption we used in Schib (2021); Schib et al. (2023) However, this is an important topic that needs further investigation.

2.2.3 Background viscosity

In the absence of global instabilities or spiral arms, we applied a background viscosity, αBG. In principle, the model can handle any reasonable value for αBG. In the simulations presented in Sect. 5 we applied a value of αBG = 10−2 throughout the disc in order to reproduce observed disc lifetimes and for consistency with S21; S23 and Paper II. This choice should integrate all mechanisms for the transport of angular momentum, such as effects of disc winds (Bai & Stone 2013; Turner et al. 2014; Suzuki et al. 2016; Weder et al. 2023) or hydrodynamic instabilities like the vertical shear instability (see e.g. Urpin & Brandenburg 1998; Klahr et al. 2023). The value of αBG may seem on the higher side compared to values on the order of 10−3 seen in the literature (Flaherty et al. 2017, 2018). We discuss this topic further in Sect. 6.1. In Appendix A, we study two additional calculations with a lower background viscosity.

In summary, we set α as the maximum of a gravitational αG and αBG,

(8)

(8)

where αG is equal to αd during the infall and to αGI afterwards.

2.3 Auto-gravitation

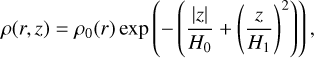

Since our discs are comparable in mass to their host star at early times, the disc’s self-gravity (auto-gravitation) must be considered. We followed the approach of Hueso & Guillot (2005) and assumed that the disc is in vertical hydrostatic equilibrium,

(9)

(9)

The right-most term is the contribution from the disc’s gravity. Then, ρ ≡ ρ(r, z) and p ≡ p(r, z) are the volume density and pressure, respectively. The disc self-gravity leads to a modification of the angular frequency relative to the Keplerian case,

![$\Omega \left( {r,t} \right) = {\left[ {{{G{M_*}} \over {{r^3}}} + {1 \over r}{{{\rm{d}}{V_{\rm{d}}}} \over {{\rm{d}}r}}} \right]^{1/2}}.$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq10.png) (10)

(10)

In Eq. (10), Vd is the gravitational potential of the disc given by (Hueso & Guillot 2005):

![${V_{\rm{d}}}\left( r \right) = \mathop \smallint \limits_{{R_*}}^\infty - G{{4{\rm{K}}\left[ { - {{4r/{r_1}} \over {{{\left( {r/{r_1} - 1} \right)}^2}}}} \right]} \over {\left| {\left( {r/{r_1} - 1} \right)} \right|}}\Sigma \left( {{r_1}} \right){\rm{d}}{r_1},$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq11.png) (11)

(11)

where R* is the stellar radius, K the elliptic integral of the first kind. The solution of Eq. (9) becomes

(12)

(12)

with ρ0(r) ≡ ρ(r, 0), where

(13)

(13)

is the contribution of the disc’s self-gravity and

(14)

(14)

is that of the star. Requiring

(15)

(15)

Thus, in our convention, we have

(16)

(16)

which leads to the expression of the vertical pressure scale height,

(17)

(17)

We refer to Sect. 2.2 of S21, Sect. 3.4.1 of Hueso & Guillot (2005) as well as Huré (2000) and Paczynski (1978) for additional comments and subtleties of this treatment of autogravitation.

The disc’s auto-gravitation also has important implications for embedded companions. They are also subject to the additional acceleration resulting from Vd and will no longer orbit on Keplerian trajectories (see Sect. 4.2). Therefore, it would not make sense to use the usual orbital elements, since these assume Keplerian orbits. Instead, we usually use the separation, r, from the origin to describe a companion’s position. A companion on an eccentric Keplerian orbit (with semi-major axis a and eccentricity e) will have a deficit in angular momentum with respect to an equal mass companion with the same semi-major axis on a circular orbit. The angular momentum is reduced by a factor  . We can thus define an ‘eccentricity’ that works in the presence of auto-gravitation by demanding that the angular momentum deficit relative to a circular2 orbit remains the same.

. We can thus define an ‘eccentricity’ that works in the presence of auto-gravitation by demanding that the angular momentum deficit relative to a circular2 orbit remains the same.

2.4 Stellar evolution

We applied the stellar evolution tables from Yorke & Bodenheimer (2008) where the radius and luminosity of an isolated protostar are tabulated. We interpolated these tables linearly for a given mass and age. In addition to the star’s intrinsic luminosity, Lint, we included a contribution, Lacc, from accretion of disc material onto the star to calculate the total luminosity,

(18)

(18)

with the stellar accretion rate, Ṁ*, that is given by the disc model. The efficiency factor of stellar accretion heating, facc, is set to 1/12 in order to reproduce on average the distribution of observed luminosities of class 0 systems (Tobin et al. 2020, S23).

2.5 Infall

Our simulations were initialised with a seed star and disc. Then the disc was fed by gas infalling from a collapsing MCC. A number of simple prescription how to calculate the source term of infalling material in a spherically symmetric setting exist. Examples are the classical Shu collapse model (Shu 1977) or the Bonnor-Ebert sphere model (Ebert 1955; Bonnor 1956). More complex infall models have been developed on the basis of these ideas, such as the TSC model (Cassen & Moosman 1981; Terebey et al. 1984). While these models provide a relatively simple and intuitive description of the disc formation process, they largely neglect its complex and turbulent nature. Hydrodynamic simulations of star formation show that high angular momentum impacts the disc early, something that is not seen in inside-out collapse. Magnetic fields add another level of complexity that we discuss in the following.

To take into account the chaotic nature of the star formation process, we based our source term on the hydrodynamic population synthesis study of discs by Bate (2018). The paper analyses the evolution and properties of discs formed in a 3D hydrodynamic star cluster simulation. Stellar masses, disc masses, and disc radii are given as a function of time for 183 synthetic protostars. In S21 we discuss in detail how we select a sample of these systems in order to construct probability distributions for initial stellar mass, disc mass, infall rate and disc size. The first three of these quantities are considered correlated: we used multi-variate distributions to obtain the initial values for these quantities. This data was then used as input quantity to perform a population synthesis of forming discs and analyse their properties. As found in S21 this baseline run ‘hydro’ leads to massive (~0.3 M⊙) and large (~200au) discs. Almost half of these discs were found to fragment. However, magnetic fields, which were not considered in Bate (2018), are thought to alter the disc formation process. Discs are found to be smaller in magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) collapse simulations than in pure hydrodynamic simulations, though the specifics depend on which aspects of magnetic fields are considered. In order to investigate this effect, another run based on MHD was performed in S21. There, we imposed much smaller infall radii (the location where the infalling material hits the disc) in such a way that the distribution of early disc sizes agrees with the prediction of an MHD simulation of disc formation (Hennebelle et al. 2016). The discs formed in this simulation are less massive (~0.1 M⊙), much smaller (~40au) and none of them fragment. Interestingly, the sizes of observed Class 0 discs (Tobin et al. 2020) lies between the early disc size in ‘hydro’ and ‘MHD’ runs. This led us to perform an additional set of simulations with an additional modification of the infall radii set to fit the observed Class 0 disc sizes. Together with the choice of face (Eq. (19)), this leads to the run ‘OBS_REDIRR’ presented in S23, which exhibits a distribution of both early disc radii and luminosities in agreement with observations. In other words, in this work we use infall radii that lead to discs with sizes that agree with the observations of Tobin et al. (2020). The infall radii found in this way are discussed in Paper II. The source term for the infall Sinf is given by (Eq. (32) of S21):

![${S_{\inf }}\left( {r,t} \right) = {{{{\dot M}_{{\rm{in}}}}} \over {2\sqrt 2 {\pi ^{3/2}}{R_{\rm{i}}}{\sigma _{\rm{i}}}}}\exp \left[ { - \left( {{{r - {R_{\rm{i}}}\left( t \right)} \over {\sqrt 2 {\sigma _{\rm{i}}}}}} \right)} \right].$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq21.png) (20)

(20)

Here, Ri is the infall location and the width σi is chosen as Ri/3.

2.6 Temperature model

Our temperature model is based on the vertical energy conservation of the disc which is in hydrostatic equilibrium (Eq. (9)). We considered the effects of the following processes: viscous heating, irradiationfromthe central star(including anaccretionterm, Eq. (18)), shock heating from the gas falling from the MCC onto the disc and a constant background irradiation from the environment. We follow Nakamoto & Nakagawa (1994); Hueso & Guillot (2005) and consider both optically thick and an optically thin regimes and assume an energy balance at the disc’s surface,

(21)

(21)

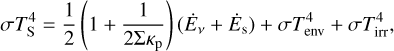

where TS is the disc’s surface temperature. This leads to an expression for the disc’s mid-plane temperature:

![$\matrix{ {\sigma T_{{\rm{mid}}}^4} \hfill & = \hfill & {{1 \over 2}\left[ {\left( {{{3\Sigma {\kappa _{\rm{R}}}} \over 8} + {1 \over {2\Sigma {\kappa _{\rm{P}}}}}} \right){{\dot E}_v} + \left( {1 + {1 \over {2\Sigma {\kappa _{\rm{P}}}}}} \right){{\dot E}_{\rm{s}}}} \right]} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {} \hfill & { + \,\sigma T_{{\rm{env}}}^4} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & {} \hfill & { + \,\sigma T_{{\rm{irr}}}^4.} \hfill \cr } $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq23.png) (22)

(22)

In Eq. (22), κR ≡ κR(ρ0, Tmid) and κP ≡ κΡ(ρ0, Tmid) are the Rosseland and Planck mean opacities. Then, κP and κR are calculated based on Malygin et al. (2014) for the gas and Semenov et al. (2003) for the dust. The calculation is done analogous to Marleau et al. (2017, 2019), assuming ‘normal silicate’ dust grains made of homogeneous spheres (per the NRM model in Semenov et al. 2003). We assume a dust-to-gas ratio of 0.01. In Eq. (22),  is the viscous heating term,

is the viscous heating term,  the shock heating term due to infall (Kimura et al. 2016). The temperature contribution due to stellar irradiation, Tirr, is calculated as in Hueso & Guillot (2005):

the shock heating term due to infall (Kimura et al. 2016). The temperature contribution due to stellar irradiation, Tirr, is calculated as in Hueso & Guillot (2005):

![${T_{{\rm{irr}}}} = {T_*}{\left[ {{2 \over {3\pi }}{{\left( {{{{R_*}} \over r}} \right)}^3} + {1 \over 2}{{\left( {{{{R_*}} \over r}} \right)}^2}\left( {{{{\rm{d}}\ln \left( H \right)} \over {{\rm{d}}ln\left( r \right)}} - 1} \right)} \right]^{1/4}},$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq26.png) (23)

(23)

where the effective stellar temperature T* is calculated as

(24)

(24)

with L* from Eq. (18). In Eq. (23), we set d ln(H)/d ln(r) ≡ 9/7 (Chiang & Goldreich 1997; Fouchet et al. 2012).

2.7 Photoevaporation and disc dispersal

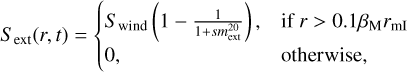

We assumed that the discs are subject to external and internal photoevaporation. Our model of external photoevaporation is based on Matsuyama et al. (2003), which considers FUV irradiation by massive stars. We applied the following sink term,

(25)

(25)

with a smoothing term  and

and  the gravitational radius. We set cs,ext = 2.5 km s−1, βM = 0.14 and Swind = 2.8 × 10−8 g cm−1 yr−1, giving an evaporation rate of 10−8 M⊙ yr−1 for a disc that extends to 1000 au. This value is relatively low, though comparable with previous work (Armitage et al. 2003; Mordasini et al. 2009).

the gravitational radius. We set cs,ext = 2.5 km s−1, βM = 0.14 and Swind = 2.8 × 10−8 g cm−1 yr−1, giving an evaporation rate of 10−8 M⊙ yr−1 for a disc that extends to 1000 au. This value is relatively low, though comparable with previous work (Armitage et al. 2003; Mordasini et al. 2009).

For the internal photoevaporation, we closely follow Clarke et al. (2001), an EUV model based on the ‘weak stellar wind’ case studied in Hollenbach et al. (1994). We used a sink term given by

(26)

(26)

with a sound speed cs,int = 11.1 km s−1,

smint is a smoothing factor of

(27)

(27)

where rint = 0.07 rg,int,  .

.

|

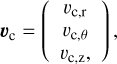

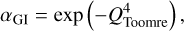

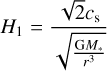

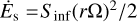

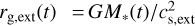

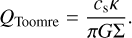

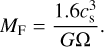

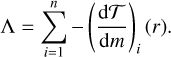

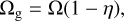

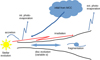

Fig. 2 Schematic overview of the physical processes related to fragmentation and the evolution of companions that are included in the global model. |

3 Fragmentation and clump evolution

In this section, we discuss the topic of fragmentation, and how we handled it in the model. This includes the formation of a clump and its subsequent evolution. Figure 2 gives a schematic overview of the relevant processes. When the disc fragments, one or several clumps are inserted. The clumps can accrete gas (Sect. 3.3) and evolve in their internal structure according to pre-calculated clump evolution tracks (Sect. 3.4) under the influence of disc irradiation (Sect. 3.5). Mass loss of clumps is discussed in Sect. 3.6. Clumps can undergo orbital migration (Sect. 4.1) and interact gravitationally with each other (Sect. 4.2).

3.1 Fragmentation

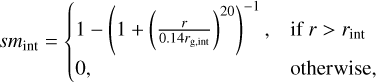

Fragmentation is the breaking up, due to self-gravity, of parts of the disc into bound objects which we call clumps or fragments. The degree to which a disc is self-gravitating can be quantified by the QToomre parameter (Toomre 1964):

(28)

(28)

It results from the stability analysis of a thin, differentially rotating fluid sheet. A QToomre < Qcrit ~ 1 permits exponentially growing modes. In Eq. (28), κ denotes the epicyclic frequency:

(29)

(29)

equal to Ω only in Keplerian discs. For fragmentation, QToomre < Qcrit is not sufficient. Such discs can remain in a state of marginal stability, where the transport of angular momentum is dominated by spiral arms (Hohl 1971; Bertin & Romeo 1988; Lodato & Rice 2004; Cossins et al. 2009; Forgan et al. 2011; Rice 2016). A disc fragments only if saturation mechanisms fail to prevent the growth of perturbations. There is a wealth of literature on fragmentation, including Goldreich & Lynden-Bell (1965); Gammie (2001); Matzner & Levin (2005); Lodato & Rice (2005); Kratter & Matzner (2006). An extensive review can be found in Kratter & Lodato (2016). In our context, it is important to consider two regimes of fragmentation.

3.1.1 Infall-dominated regime of fragmentation

During the infall phase, material from the MCC can reach the disc at a rate greater than it can be transported away. If this occurs, the disc invariably fragments (Boley 2009). We call this the ‘infall-dominated’ regime. The ξ and Γ parameters introduced in Sect. 2.2.1 can be employed to check if we are in this regime. The condition is given in Kratter et al. (2010a) (see also Sect. 3.6 of Kratter & Lodato 2016):

(30)

(30)

In our model, we assume the disc fragments if QToomre < 1 in the infall-dominated regime.

3.1.2 Cooling-dominated regime of fragmentation

If the condition from Eq. (30) is not satisfied (in particular after the infall phase), the disc fragments only if it can cool efficiently. Gammie (2001) performed shearing sheet simulations of a razor thin disc to demonstrate that this is the case, if the cooling timescale is less than a few times the orbital timescale, following the expression

(31)

(31)

a condition known as the Gammie criterion. βc ≈ 3 is the critical cooling parameter as determined by Deng et al. (2017), see also Baehr et al. (2017). We employ the following cooling timescale (Mordasini et al. 2012):

(32)

(32)

where τeff = κRΣ/2 + 2/(κRΣ) is an effective optical depth, γ ≡ 1.45 is the adiabatic index. We therefore assume that the disc fragments if QToomre < 1 and Eq. (31) are satisfied simultaneously.

In summary, our condition for fragmentation is as follows: QToomre < 1 and either Eq. (30) or (31) must be satisfied. These conditions are checked throughout the disc at every time step.

3.2 Initial fragment mass and insertion of fragments

If the disc fragments, the initial fragment mass MF (given in Eq. (36)) is removed from the disc at the location (annulus), where QToomre is minimal at the time of fragmentation. (For population synthesis calculations, the procedure is slightly different, as explained in Sect. 4.4 of Paper II). The clump’s properties (aside its mass and age) are determined by means of evolution tracks, as described in Sect. 3.4. A clump of the same mass is inserted at this location rc. In order to avoid unphysical effects by removing mass from the disc instantly, we instead removed the initial fragment mass on a fiftieth of an orbital timescale. We found that varying this value over reasonable ranges does not strongly affect the outcomes. We apply the following sink term in Eq. (2):

(33)

(33)

with Ṁinsert = 50MFO(rc)/(2π). For  , we chose

, we chose  (the exact value of this width is not very important).

(the exact value of this width is not very important).

How massive emerging clumps are is important, since the pre-collapse timescale has a strong mass dependency (Sect. 3.6). A rough estimate for the initial fragment mass is the Toomre mass (Nelson 2006):

(34)

(34)

Forgan & Rice (2011) performed more detailed calculations and derived a measure for the local Jeans mass inside the spiral structure of a self-gravitating disc. In our conventions (note the comments in Sect. 2.9.2 in S21) it is equivalent to

(35)

(35)

where βcool = tcoolΩ. The cooling timescale tcool is given in Eq. (32). A different estimate of the initial fragment mass is given in Boley et al. (2010). The authors performed a calculation that considers the density perturbation near the corotation of a spiral arm. They initial clump mass in the context of a fragmenting spiral arm was found to be

(36)

(36)

We observe that there is a substantial difference between these three estimates, with MF being by far the lowest. For a Keplerian disc with QToomre = 1, we have

where  is the Jeans mass given in Eq. (13) of Nelson (2006). Boley (2009) performed 3D SPH simulations with radiative cooling and found good agreement of their analytic expression (MF) with the simulation results. This has also been investigated by Tamburello et al. (2015), albeit in a different context. These authors performed simulations of isolated galaxies using an N-body + SPH code and also found initial fragment masses comparable to or even lower than MF. A possible interpretation of the much higher value of MJ,FR is that it does not represent the mass of a clump at the time of fragmentation, but instead, after a few orbits, where it could have accreted a substantial amount of gas. When including magnetic fields, we note that the gravitational instability dynamo may lead to even lower fragment masses (Deng et al. 2021; Kubli et al. 2023). Given these results, we use MF as the nominal initial mass for our clumps. The influence of a higher initial fragment mass is investigated in Paper II.

is the Jeans mass given in Eq. (13) of Nelson (2006). Boley (2009) performed 3D SPH simulations with radiative cooling and found good agreement of their analytic expression (MF) with the simulation results. This has also been investigated by Tamburello et al. (2015), albeit in a different context. These authors performed simulations of isolated galaxies using an N-body + SPH code and also found initial fragment masses comparable to or even lower than MF. A possible interpretation of the much higher value of MJ,FR is that it does not represent the mass of a clump at the time of fragmentation, but instead, after a few orbits, where it could have accreted a substantial amount of gas. When including magnetic fields, we note that the gravitational instability dynamo may lead to even lower fragment masses (Deng et al. 2021; Kubli et al. 2023). Given these results, we use MF as the nominal initial mass for our clumps. The influence of a higher initial fragment mass is investigated in Paper II.

During the short period where the fragment is set up, it is kept at a constant separation and is not allowed to interact with the disc (except for the mass removal). No other fragments are allowed to form inside of a Hill radius (for MF) during this time.

3.3 Gas accretion

We applied the model for gas accretion as presented in S22. This model is based on the Bondi and Hill accretion regimes investigated in D’Angelo & Lubow (2008) (DL08). These authors performed 3D nested grid hydrodynamic simulations of migrating planet undergoing rapid gas accretion. They estimated the accretion rate onto the companion in their Eq. (9), expressed as

(37)

(37)

Here, Rf is the radius of the feeding zone of a companion of mass Mc at a separation rc. It is taken to be the smaller of either the Bondi radius  or the Hill radius3

or the Hill radius3  . The accretion rates in the Bondi and Hill regime then become:

. The accretion rates in the Bondi and Hill regime then become:

(38)

(38)

(39)

(39)

where CB and CH are dimensionless coefficients of order unity. DL08 found that the accretion rate onto the protoplanet agrees well with min (ṀB, ṀH) as long as the disc is able to supply enough gas. Once the local reservoir is depleted, the accretion rate drops.

In S22, we derived an accretion model based on Eq. (37). Instead of using global values of Σ and Ω, we calculate the contributions from each grid cell inside the feeding zone separately. The gas is then removed self-consistently from the disc at the location from where it was accreted. We obtain the following accretion rate (Eq. (D.5) in S22):

![$\matrix{ {{{\dot M}_{{\rm{B,H}}}} = \sqrt \pi {C_{{\rm{B,H}}}}\mathop \smallint \limits_{{r_{\rm{c}}} - {R_{\rm{f}}}}^{{r_{\rm{c}}} + {R_{\rm{f}}}} {\rho _0}\left( r \right){H_1}\exp \left( {{{H_1^2} \over {H_0^2}}} \right)} \hfill \cr {\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\, \times \left( {{\rm{erf}}\left[ {{{\sqrt {R_{\rm{f}}^2 - {{\left( {r - {r_{\rm{c}}}} \right)}^2}} } \over {{H_1}}} + {{{H_1}} \over {2{H_0}}}} \right] - {\rm{erf}}\left[ {{{{H_1}} \over {2{H_0}}}} \right]} \right){\upsilon _{{\rm{rel}}}}\,{\rm{d}}r.} \hfill \cr } $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq53.png) (40)

(40)

In Eq. (40), CB,H denotes the numerical factor, calibrated with the results from DL08 to be CB = 10 and CH = 0.19, respectively in S22. The quantities H0 and H1 are related to the disc’s auto-gravitation and are described in Sect. 2.3. υrel = |rΩ – rcΩc| is the velocity of the gas relative to the companion.

In S22, we compare the accretion model, together with our migration model with the results from two different hydro-dynamic simulations of accreting, migrating companions. We typically find a reasonable agreement for a range of parameters.

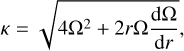

3.4 Clump evolution tracks

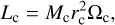

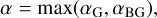

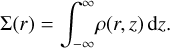

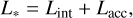

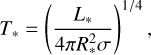

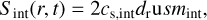

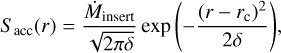

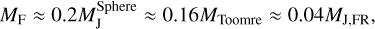

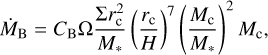

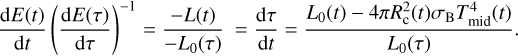

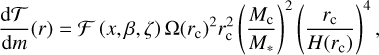

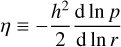

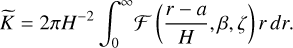

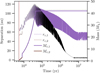

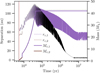

Just after formation, clumps are extended, au-sized objects of low density. They will contract and heat up on a timescale that strongly depends on their mass. During the time that a clump is young and extended, it is prone to tidal destruction. However, if the interior reaches temperatures of ~2000 K, the clump undergoes a dynamical collapse due to the dissociation of molecular hydrogen (Bodenheimer 1974). The radius then shrinks by about three orders of magnitude to a few Jovian radii (R4). In order to account for this evolution, we employed interior evolution tracks of isolated clumps. These tracks are the result of 1D calculations of clumps published in Humphries et al. (2019). The code used solves the standard stellar structure equations on a fully implicit, adaptive grid (Helled et al. 2006, 2008; Vazan & Helled 2012; Vazan et al. 2013, 2015). It assumes a protosolar hydrogen-helium composition and the Saumon et al. (1995) equation of state. Heat transport inside the clump is modelled by convection, conduction or radiation, depending on the local conditions. In the radiative regions, opacities from Pollack et al. (1985) are used. The clumps evolve in isolation (i.e. with a zero pressure boundary condition), which means that no exchange of mass or irradiation are considered. Tracks are available for a number of masses, ranging from 0.5 M4 to 12M4. Since the clump masses in our simulations evolve with time, we linearly interpolate the quantities from the evolution tracks. This allows us to determine the clumps’ (and later compact objects’) properties, such as radius and temperature, at any time during their evolution. Figure 3 shows the time evolution of the radius, central density and central temperature for a selection of clump masses. Also shown is the pre-collapse time for all masses. We define the pre-collapse time as the age of the clump when its central temperature reaches 2000 K. At this time, the clump radius plummets, while the central density and temperature increase.

|

Fig. 3 Evolution tracks of isolated clumps. Top left: clump radius. Top right: central density. Bottom left: central temperature. Bottom right: precollapse time for all clump masses. These tracks were first published in Humphries et al. (2019). |

3.5 Clump irradiation

Our evolution tracks were calculated for isolated clumps. However, when clumps form, they are embedded in the surrounding circumstellar disc. The clumps are therefore irradiated by the surrounding disc material. This influences their evolution, and this effect is not considered in the tracks.

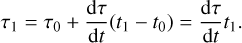

In the absence of tabulated tracks including irradiation we follow an approximate approach inspired by Humphries et al. (2019)4. The authors assume that, because of the irradiation, the clump’s evolution is slowed down: The clump’s ‘internal time’, τ, passes more slowly than the physical time t depending on the incident radiation. For the clump’s total energy Ε we have:

(41)

(41)

where L0(τ) is the clumps radiative luminosity in isolation. If the clump is embedded in the disc, its energy balance is modified by the incident irradiation from the disc, and at time t it must hold:

(42)

(42)

where the right-most term denotes the radiation incident on the clump from the disc (Rc is the clump’s radius and Tmid is the disc’s mid-plane temperature evaluated at the clump’s location).

The clump’s radius and luminosity for a given clump mass and age are linearly interpolated from the evolution tables (Sect. 3.4). Equation (42) expresses that, in order to infer the clump’s effective luminosity L, its luminosity in isolation must be reduced by the incident luminosity from the disc. In order to find the relationship between t and τ, we divide Eq. (42) by Eq. (41) and obtain

(43)

(43)

In the second equality we required dE(t) = dE(τ) since we want to evaluate the evolution tables at a time where the change in total energy of the isolated case is the same as in the irradiated case. Equation (43) allows us to infer τ for a given time t. For example for τ0 = t0 = 0 s, at t1, we get

(44)

(44)

Knowing the relationship between t and τ allows us to calculate the properties of the irradiated clump: for a clump with internal age τ1 the evolution tables are evaluated at  .

.

This approach is a reasonable approximation when Tmid is much lower than the clump’s effective temperature Teff; however, it becomes problematic if the two reach comparable values. For example, if they are the same, Eq. (43) gives τ = const. In other words, the clump stops evolving. In a realistic scenario, we would expect the clump to adapt to a different interior structure, possibly with a larger radius or losing some of its mass. The situation becomes even more problematic if Tmid exceeds Teff. In practice, we kept τ constant in this case, and instead compared Tmid with the clump’s central temperature. If the disc’s temperature exceeds even that, we assumed that the clump is thermally destroyed (Cameron et al. 1982; Vazan & Helled 2012). Once available from dedicated evolutionary simulations, we will use evolution tracks including irradiation in future iterations of the global model.

3.6 Mass loss

When a clump moves closer to the star, its Hill radius RH decreases. At some point, the clump’s physical radius given by the tracks can become larger than its Hill radius. We assumed that in this case the clump loses the mass outside of its Hill sphere (Roche lobe overflow). In our model, Rc is compared with RH at each time step. If Rc > RH, the clump’s mass is reduced by a small amount and Rc is redetermined from the evolution tables. The new radius is again compared with RH for the reduced mass. This process is repeated until Rc ≤ RH. In some cases, no stable configuration is found, which implies that the clump was entirely disrupted (tidal destruction). Any mass lost in this process is returned to the disc at the clump’s location via a source term (Sloss in Eq. (1)). The same happens if a clump is destroyed due to thermal disruption (Sect. 3.5).

4 Clump–disc and clump–clump interactions

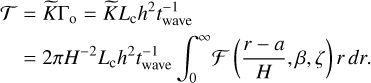

4.1 Gas disc-driven orbital migration

A companion embedded in a circumstellar disc interacts gravitationally with the disc gas. The exchange of angular momentum leads to orbital migration (Goldreich & Tremaine 1980). Classically, gas disc migration has been divided into two main regimes. In the type I regime, the surface density remains largely unperturbed by the presence of the companion. In a non-self-gravitating disc, this is the case for planets up to a few to a few tens of Earth masses (Μ⊕). The exact value depends on the stellar mass and disc properties. Type I migration is complex and is strongly affected by the disc’s thermodynamics. Some of the contribution to the total torque comes from Lind-blad resonances and is typically negative (inwards) (Goldreich & Ward 1973). Additional contributions come from the co-rotation region and these can be both negative and positive, such that the net migration can be both inwards and outwards (Paardekooper & Mellema 2006). An important aspect in determining whether outward migration is possible is the saturation of the co-rotation torque at higher masses, since the saturation works against outward migration (Paardekooper et al. 2011). More massive companions start to perturb the surface density significantly until they clear a gap in the vicinity of their orbit. They are then said to migrate in type II. The simple picture consisting of type I and type II migration is helpful when studying planets formed in CA. Such planets are assembled from initial masses of ≪ 1 Μ⊕ that need to accrete mass for many orbits to eventually open a gap. Prescriptions for the type I migration (e.g. Tanaka et al. 2002; Paardekooper et al. 2010, 2011) can then be applied until some criterion for gap opening is fulfilled (Crida et al. 2006; Kanagawa et al. 2018). Above gap-opening masses, type II prescriptions can then be applied (Dittkrist et al. 2014; Kanagawa et al. 2018).

In DI, the situation is different. Fragments are born with high masses ~M4 and they may migrate too fast to carve a deep gap despite their high masses. Furthermore, migration is expected to be to some degree stochastic (Baruteau et al. 2011; Kubli et al. 2025). The conventional formulae for type I migration assuming a steady state cannot be applied, and the conditions for gap opening are still uncertain (Malik et al. 2015; Müller et al. 2018; Rowther & Meru 2020). Furthermore, while the transfer of angular momentum from a ~Μ⊕ planet on the disc gas may be negligible, this is not the case for a clump of several M4.

4.1.1 Torque densities

In order to overcome these limitations, we applied the migration model from S22. The migration model uses torque densities to account for the two-way exchange of angular momentum between the disc and the companions. The torque density distribution per unit disc mass,  , for companion i is defined such that

, for companion i is defined such that

(45)

(45)

where Ti is the total torque on companion i: the sum of the contributions from all radial locations in the disc. In the evolution equation (Eq. (1)) we thus have for n companions:

(46)

(46)

In principle, this formalism fully integrates the exchange of angular momentum between the disc and the companions in our model. Hereafter, we drop the subscript i and consider the case of an individual planet for readability.

We note, however, that two important questions remain unanswered regarding (1) the shape of  and (2) what happens with planets on eccentric orbits.

and (2) what happens with planets on eccentric orbits.

For the first question, possible choices are the classical impulse approximation (Lin & Papaloizou 1979a,b, 1986) or an improved formalism (Armitage et al. 2002). These approaches can work reasonably well in a pure type II regime where a gap has already been fully opened. However, they do not work well in type I or in the transition between type I and type II because the approach explicitly excludes co-rotation torques. As discussed above, co-rotation torques are important there. Fortunately, torque densities are well suited for the type I regime as well – provided they include co-rotation torques. A model that accomplishes this is presented in D’Angelo & Lubow (2010). The authors performed 3D nested grid hydrodynamic simulations of locally isothermal discs. They provided a functional form of the torque density distribution parametrised by the disc’s surface density and temperature gradients,

(47)

(47)

is a dimensionless function describing the shape of the torque density. In Eq. (48), β = –d ln Σ/d ln r and ζ = –d in T/d ln r,  is a scaling factor. The parameters p1 to p8 depend on β and ζ and set the amplitude and width of the torque density. They are determined by D’Angelo & Lubow (2010) via fits to their simulations. This form of the torque density is adequate to the type I regime, D’Angelo & Lubow (2010) study 1 Μ⊕-planets in most of their simulations. However, they also explored what happens in the case of gap-opening planets. They showed that when the planetary mass increases, the amplitude (scaled) torque density decreases, although only by a factor of order unity.

is a scaling factor. The parameters p1 to p8 depend on β and ζ and set the amplitude and width of the torque density. They are determined by D’Angelo & Lubow (2010) via fits to their simulations. This form of the torque density is adequate to the type I regime, D’Angelo & Lubow (2010) study 1 Μ⊕-planets in most of their simulations. However, they also explored what happens in the case of gap-opening planets. They showed that when the planetary mass increases, the amplitude (scaled) torque density decreases, although only by a factor of order unity.

4.1.2 High mass torque

In addition to the decreasing amplitude, as the planetary mass approaches 1 Μ4, an inversion of the torque density starts to appear near the position of the planet (their Fig. 15). The exact shape of this inversion, which depends strongly on the planet’s mass is, however, not very important. What is important is that the torque is small near the planet. In S22 we studied this effect by applying a torque model named the ‘high-mass torque model’ resulting from an interpolation of Fig. 15 in D’Angelo & Lubow (2010) to accreting, migrating planets. We argued that the inversion of the torque density prevents premature gap opening and compared the migration tracks of these 1D simulations with the 3D nested grid hydrodynamic simulations of DL08, finding reasonable agreement for a range of parameters. We also showed that without the modifications related to the planet’s mass, a gap opens too fast and migration slow down too quickly. While the torque model performs well in comparison with locally isothermal 3D simulations, it cannot reproduce features such as the outward migration that depend on the (non-)saturation of the co-rotation torque. We propose a simple method to overcome this limitation in Appendix F of S22. For the present study, these effects should not be important, since we are dealing with massive objects for which the co-rotation torque saturates. Therefore, we applied the high mass torque from S22 in Eq. (45). Since we also applied this shape of the torque density to higher-mass companions, we prevented the inversion close to the companion by setting  near the companion (Hallam & Paardekooper 2017). We note that despite our treatment of the torque densities at high masses, their application to 1D discs leads to gap shapes that are different from what is seen in hydrodynamic simulations. This is seen in simulations running for hundreds of orbits and the gaps in 1D tend to become too deep and too narrow. We discuss this issue and its possible consequences in Sect. 6.2 and will address this topic in future research.

near the companion (Hallam & Paardekooper 2017). We note that despite our treatment of the torque densities at high masses, their application to 1D discs leads to gap shapes that are different from what is seen in hydrodynamic simulations. This is seen in simulations running for hundreds of orbits and the gaps in 1D tend to become too deep and too narrow. We discuss this issue and its possible consequences in Sect. 6.2 and will address this topic in future research.

4.1.3 Eccentric and inclined orbits

The second question raised in Sect. 4.1.1 about companions on eccentric orbits is particularly important for multiple systems. Even if all companions (like newly formed clumps) were initially on (approximately) flat, circular orbits, the mutual gravitational interaction of the companions tends to increase their eccentricity and inclinations. Furthermore, in the context of DI, we expect the clumps to be on initially eccentric orbits, since they are born near the corotation of spiral arms.

Strictly speaking, the torque density formulation discussed in Sect. 4.1.1 is only applicable for nearly circular, flat orbits. The same is true for the type I migration formulae mentioned in Sect. 4.1. These must be modified (Cresswell & Nelson 2008; Bitsch & Kley 2010; Fendyke & Nelson 2014; Coleman & Nelson 2014). The treatment in the context of torque densities is not trivial.

To our knowledge, no published torque densities for eccentric, inclined orbits exist (but see Fairbairn & Dittmann 2025). However, simply applying, for example, the torque density corresponding to a companion’s semi-major axis to the disc when the companion is on a strongly eccentric orbit violates the conservation of angular momentum. Numerical experiments show that doing so tends to add angular momentum to the system, which can lead to unphysical fragmentation events and other complications. We stress that such difficulties arise only if the companion’s torque is applied on the disc through Eq. (1). An additional complication arises in relation to the damping of eccentricities and inclinations. This damping is expected as long as the companions are embedded in a gas disc. For massive companions in type II migration, hydrodynamic simulations show that damping occurs on timescales shorter than the migration timescale (Kley et al. 2004; Kley 2019). In this situation, the so-called K-damping is often applied (Lee & Peale 2002), where the damping timescale is set to 1/K times the migration timescale. K is typically of the order of ten Emsenhuber et al. (2021a). The damping is then applied to the companion as an additional acceleration in the N-body integrator. In the context of our model, this becomes problematic, since it means applying a torque or force to a companion without applying the opposite equal to the disc. Again, this leads to unphysical effects in the disc evolution.

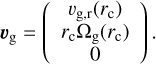

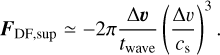

For this reason, we developed a more robust way to model migration and damping for massive companions. It is based on the formulation of planet-disc interaction in the framework of dynamical friction presented in Ida et al. (2020). The authors studied planet-disc interactions in the subsonic and supersonic regimes and compared and discussed in detail various approaches to calculate damping found in the literature. Based on this discussion and on the results of a hydrodynamic simulation, they provided a simple prescription for the damping timescales of semi-major axis, eccentricity and inclination for low-mass planets. In order for this approach to be applicable in our model, we need to demonstrate that, in the limit or circular orbits, we retrieve the same torque as the one obtained from the high mass torque (Sect. 4.1.2). Furthermore, it also needs to be applicable for massive companions.

Ida et al. (2020) assumed discs with smooth surface densities in their Sect. 4 to arrive at equations of motion that can be expressed in terms of the migration timescale (their Eq. (46)). In order to apply the dynamical friction formalism to gap-opening companions, we need to relax this assumption. Instead, we start from their Eqs. (29) and (32). Their Eq. (29) gives the (specific) force from dynamic friction in the subsonic limit (Tanaka & Ward 2004):

(49)

(49)

with the characteristic (inverse) timescale of

(50)

(50)

we have the mass ratio of the companion to the star,

(51)

(51)

and the velocity of the companion relative to the gas,

(54)

(54)

and, assuming an unpertured disc velocity field,

(56)

(56)

These are the velocities of the companion and the gas (at the companion’s separation), respectively, in cylindrical coordinates. For Δυ ≡ |Δυ| we get

(57)

(57)

The angular frequency of the gas, Ωg is given by

(58)

(58)

with Ω from Eq. (10). The factor

(59)

(59)

accounts for the deviation of the gas velocity from the purely gravitational value due to the pressure gradient. For smooth discs this effect is very small, but it is important here because otherwise the θ-component of Δυ vanishes for a companion on a circular orbit. For the supersonic limit, Ida et al. (2020) apply the expression from Muto et al. (2011) (their Eq. (32), simplified):

(60)

(60)

Summation of timescales then leads to (as in their Eq. (35)):

![${F_{{\rm{DF}}}} = {{\Delta \upsilon } \over {\Delta \upsilon }}{\left[ {{1 \over { - 0.78\Delta \upsilon t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}}} + {1 \over { - 2\pi \Delta \upsilon t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}}}{{\left( {{{\Delta \upsilon } \over {{c_{\rm{s}}}}}} \right)}^3}} \right]^{ - 1}}.$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq79.png) (61)

(61)

As discussed in Ida et al. (2020), the dynamical friction formalism can recover the migration rate in the subsonic case, but only to an order of magnitude. This is because in the subsonic regime, the contribution by density waves is important. A way to include this contribution without assuming low masses is to modify Eq. (61). To do this, a relationship between the total torque calculated through Eq. (45) and  is needed. We write the total torque on a companion as:

is needed. We write the total torque on a companion as:

(62)

(62)

where  is a dimensionless prefactor. With the migration timescale, τ:

is a dimensionless prefactor. With the migration timescale, τ:

(63)

(63)

is the orbital angular momentum of the companion, which can be expressed as

(65)

(65)

If we assume Σ(r) ~ Σc in Eq. (45) and substitute from Eq. (47), then formally we can write:

(66)

(66)

Now Eq. (61) can be modified. We replace the factor –0.78 by  . In order to see that this choice is reasonable, we consider the θ-component for a circular orbit. Then we have Δυ/cs << 1 and Δυ = υc,θ – rcΩg = rcηΩ, and thus:

. In order to see that this choice is reasonable, we consider the θ-component for a circular orbit. Then we have Δυ/cs << 1 and Δυ = υc,θ – rcΩg = rcηΩ, and thus:

![$\matrix{ {{F_{{\rm{DF}},\theta }}} \hfill & = \hfill & {{{\left[ {{\eta \over {\mathop K\limits^ {h^2}{r_{\rm{c}}}\eta \Omega t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}}}} \right]}^{ - 1}}} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & = \hfill & {{{\mathop K\limits^ {h^2}r_{\rm{c}}^2{M_{\rm{c}}}{\Omega _{\rm{c}}}t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}} \over {{M_{\rm{c}}}{r_{\rm{c}}}}}} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & = \hfill & {{{\mathop K\limits^ {L_{\rm{c}}}{h^2}t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}} \over {{M_{\rm{c}}}{r_{\rm{c}}}}}} \hfill \cr {} \hfill & = \hfill & {{T \over {{M_{\rm{c}}}{r_{\rm{c}}}}}.} \hfill \cr } $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq89.png) (68)

(68)

In the first step, we use Ω = Ω for a circular orbit. In the second step, we substitute the expression from Eq. (64) and in the third, we drew from Eq. (67). Thus, we retrieve the acceleration of the companion when subject to the torque from Eq. (45). In the general case, we therefore apply the following acceleration (see Sect. 4.2 for the sign of T):

![${F_{{\rm{TD,DF}}}} = {{\Delta \upsilon } \over {\Delta \upsilon }}{\left[ {{{{M_{\rm{c}}}{r_{\rm{c}}}} \over T} - {1 \over {2\pi \Delta \upsilon t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}}}{{\left( {{{\Delta \upsilon } \over {{c_{\rm{s}}}}}} \right)}^3}} \right]^{ - 1}}.$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq90.png) (69)

(69)

It includes the contribution to migration by density waves, is not limited to smooth discs and reproduces the supersonic limit.

Equation (69) also illustrates what we have discussed above: in case of circular orbits, the torques on companion and disc are equal but opposite. Conversely, on eccentric orbits, υc,θ is typically different from rΩg. Therefore, it would not be correct to apply the torque from Eq. (45) to the disc. Instead, when applying the torque to the disc, it is scaled by the sine of the angle between the position vector rc and the velocity vector, υg,

(70)

(70)

This ensures that the torque on the disc is reduced for eccentric orbits and gives the correct limit for radial motion (zero torque on the disc).

We note that our treatment of synchronising the torques between the companion and the disc fully accounts for accelerations only in θ direction. Applying torques in r- and z- direction would make the disc locally eccentric/inclined. This is not possible in our model which corresponds to a rotationally symmetric disc centred in the z = 0 plane.

4.2 Gravitational interaction

In addition to the tidal interaction with the gas disc, companions also interact with each other gravitationally. We employ the mercury N-body code (Chambers 1999) to model such interactions. It is a symplectic integrator that applies a hybrid method in order to correctly handle close encounters. mercury is called in each main time step. Since the companion positions are updated in the N-body code, the result of the companions’ interaction with the gas disc must also be included there. This is done by means of additional (specific) forces. The form of these forces related to gas disc migration as well as i- and e-damping is discussed in Sect. 4.1. Here we give the final expressions that are passed to the N-body code. There is a subtlety to the application of these forces. It is done in cylindric, heliocentric coordinates. This means that the companions’ positions and velocities first need to be transformed from democratic to heliocentric coordinates, and then decomposed into tangential and radial components. After the application, the transformation needs to be inverted. The force in r-direction is

![${F_{\rm{r}}} = {{{\upsilon _{{\rm{c,r}}}} + {{\dot m} \over {2\pi r{\Sigma _{\rm{c}}}}}} \over {\Delta \upsilon }}{\left[ { - {{{M_{\rm{c}}}{r_{\rm{c}}}} \over {\left| T \right|}} - {1 \over {2\pi \Delta \upsilon t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}}}{{\left( {{{\Delta \upsilon } \over {{c_{\rm{s}}}}}} \right)}^3}} \right]^{ - 1}} - {d \over {dr}}{V_{\rm{d}}}\left( r \right).$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq92.png) (71)

(71)

The first summand in Eq. (71) is almost as in the r-component of Eq. (69), (we substituted  for υg,r, with ṁ ≡ ṁ(r) the gas accretion rate in the disc)5. The difference is the sign of the first summand in the square brackets. This term is always negative since it corresponds to the damping, which needs to be in the direction opposite to the companion’s relative motion. The second summand in Eq. (71) is the additional acceleration resulting from the disc’s gravitational potential. In θ-direction we have the force:

for υg,r, with ṁ ≡ ṁ(r) the gas accretion rate in the disc)5. The difference is the sign of the first summand in the square brackets. This term is always negative since it corresponds to the damping, which needs to be in the direction opposite to the companion’s relative motion. The second summand in Eq. (71) is the additional acceleration resulting from the disc’s gravitational potential. In θ-direction we have the force:

![${F_\theta } = {{{\upsilon _{{\rm{c}},\theta }} - {r_{\rm{c}}}{\Omega _{\rm{g}}}\left( {{r_{\rm{c}}}} \right)} \over {\Delta u}}{\left[ {{{{M_{\rm{c}}}{r_{\rm{c}}}} \over T} - {1 \over {2\pi \Delta \upsilon t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}}}{{\left( {{{\Delta \upsilon } \over {{c_{\rm{s}}}}}} \right)}^3}} \right]^{ - 1}},$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq94.png) (72)

(72)

exactly as in the θ-component of Eq. (69). Migration is typically directed inward (T < 0), although it can also become positive. For the z-direction, we obtained

![${F_{\rm{z}}} = {{{\upsilon _{{\rm{c,z}}}}} \over {\Delta u}}{\left[ { - {{{M_{\rm{c}}}{r_{\rm{c}}}} \over {\left| T \right|}} - {1 \over {2\pi \Delta \upsilon t_{{\rm{wave}}}^{ - 1}}}{{\left( {{{\Delta \upsilon } \over {{c_{\rm{s}}}}}} \right)}^3}} \right]^{ - 1}} - sign\left( {{z_{\rm{c}}}} \right)2\pi G{\Sigma _{{\rm{enc}}}},$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa56262-25/aa56262-25-eq95.png) (73)

(73)

with the same sign in the T-term as in Eq. (71). zc is the companion’s z-coordinate. In Eq. (73), the last summand is the acceleration an inclined companion experiences due to the disc’s gravity. We assumed that this acceleration results from an infinitely extended, thin disc with the surface density Σenc enclosed by the companion. We note that this additional term does not damp the inclination of the companion, since it is directed against υc,z only if zc and υc,z have the same sign.

4.3 Collisions

When the companions interact gravitationally they can experience close encounters, leading to scatterings, or collisions. In this study, we treated all collisions as perfect mergers: when two companions come closer than the sum of their radii, a perfectly inelastic collision is assumed to occur. This may appear as an extreme assumption since it neglects the possibility of eruptive or hit-and-run collisions that would change the orbits of the bodies in question without completely destroying one of them. This is especially true for clumps due to their large extension. Indeed, it was shown that collisions between clumps can lead to various outcomes depending on the assumed conditions (see Matzkevich et al. 2024 for details). However, we found that most clump-clump collision typically occur below the mutual escape speed. In this regime (see also Wimarsson et al. (2025) for a similar collisional regime in a different context), perfect merging may be a reasonable assumption (e.g. Leinhardt & Stewart 2012; Chau et al. 2021). We study collisions further in Paper II.

Overall, the global disc instability formation model presented here contains – in the low dimensional approximation – a significant number of physical processes that are coupled in a self-consistent way. At the same, it is still a strong simplification of the actual companion formation and evolution process. We discuss important limitations in Sect. 6.

5 Formation of individual systems

Thanks to its low-dimensional character, it is possible to employ the global model for population syntheses. However, before studying the result of the model in a statistical sense in Paper II, it is important to discuss the evolution of several individual systems, studying outcomes of increasing complexity. Thus, we began by looking at the simple case of a system that does not fragment. Then we studied a system with a single fragmentation event that only produces one clump. Next, we looked at a system with two fragmentation events. Finally, we investigated a more complex system evolution with multiple fragmentation events and several interacting clumps.

|

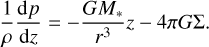

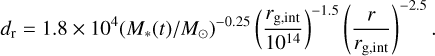

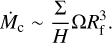

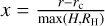

Fig. 4 Evolution of a system that becomes self-gravitating but that does not fragment. Left panel: stellar mass, disc mass and disc size as a function of time. Right panel: minimum QToomre and α as a function of time. The black vertical line shows the end of infall. It should be noted that there two distinct y-axes in both panels to which the different quantities belong to. |

5.1 A non-fragmenting system

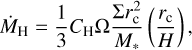

Figure 4 shows the time evolution of a system where the disc becomes self-gravitating (i.e. where QToomre approaches unity and spiral waves would form) but where no fragmentation occurs. As we shall see in Paper II, such an outcome is the most probable one: while almost all discs are found to have early on a self-gravitating phase, only 10–20% fragment. Thus, only the disc part of the model is used. This system is initialised at 1 kyr with a stellar seed of ≈6.5 × 10−2 M⊙ and a disc of (≈2 × 10−2 M⊙). It experiences infall at ≈3 × 10−5 M⊙yr−1 until t ≃ 36 kyr. The left panel of Fig. 4 displays the stellar and disc masses as a function of time.

The disc mass is initially less than a third of the stellar mass. Due to the rapid infall, the disc mass increases quickly to two thirds the stellar mass. This leads to a very fast transport of angular momentum via the global instability of the disc (Sect. 2.2.1). The associated α parameter is shown in the right panel of the figure. It reaches almost 0.3 in the early phase. The QToomre parameter, also shown in the right panel, drops to low values, but remains just above unity. After the infall phase terminates (indicated with a thin vertical line), α drops quickly, although it remains elevated above background αBG for more than 100 kyr. This coincides well with the overall minimum value of QToomre, which is lower than about 1.5 in the same period. We expect such a system to exhibit spiral arms for about 100 kyr. Here, we see the typical auto-regulation of self-gravitating discs: as QToomre approaches unity, spiral waves develop which efficiently transport away mass and angular momentum. In our model, this is expressed by the increase of α reaching a high value of almost 0.3. This increases in turn QToomre via a higher disc temperature and reduced surface density. In this system, fragmentation is prevented this way. It is also a typical behaviour that the overall lowest QToomre is reached directly after the end of infall, because at this moment, the heating (and thus stabilisation) of the disc by shock heating of the disc’s surface by infalling gas vanishes.

5.2 A simple fragmenting system

The next system we investigate has a lower total mass than the one discussed above, although the behaviour of stellar mass and disc mass is qualitatively similar (top left panel of Fig. 5). The initial values are 0.02 M⊙ and 0.04 M⊙ for stellar mass and disc mass, respectively, with infall at 4.9 × 10−5 M⊙ yr−1 until 5.5 kyr. In this case (with a very high disc-to-star mass ratio) the unstable initial state leads to accretion bursts. This is seen as an oscillatory feature in QToomre and α. We checked that these oscillations are not numerical in nature by rerunning the simulation at a much lower time step. The thin black dash-dotted line in the top right panel of the figure, shows the accretion rate of disc material on the star mdot (in units of 10−4 M⊙ yr−1 vs the left y-axis). The accretion rate also shows strong oscillations between 1 and 2 kyr. The final stellar mass is ≈0.2 M⊙.

In Fig. 5, the end of the infall phase is again marked with a black vertical line. In this case, given the combination of quantities setting QToomre, a value slightly less than unity is reached and a fragment is formed with an initial mass (set according to Eq. (36) based on the local disc conditions) of 0.9 M4 at 44 au. The middle left panel shows the time evolution of mass (solid line) and separation (dashed line) of the fragment. The red vertical line at ≈6 kyr marks the fragmentation event. Initially, the fragment migrates inwards rapidly, while accreting gas from the disc. At approximately 10 kyr (or after about six initial orbits), the migration is slowed down. At this time, the forming companion has already accreted almost 4 M4 of gas. The middle right panel shows a zoom-in on the same data with a linear x-axis, revealing more details of what is happening in the early phase. The accretion rate is at its maximum of 103 M4 yr−1 during the early phase due to the massive disc and the fast transport. The rapid inward migration is slowed down after ≈ 10 kyr with the onset of the formation of a gap.

The fragment in Fig. 5 starts with a moderate initial angular momentum deficit (corresponding to an eccentricity of ≈0.08, see Sect. 2.3) and does not exhibit strong oscillations in its separation at 6 kyr (middle right panel). To understand the role of different initial orbital eccentricities, we run two variant simulations which only differs by the initial eccentricity. They are shown only in the middle right panel. In the first variant simulation, we studied how the fragment would behave with a higher initial ‘eccentricity’ (see Sect. 2.3) of 0.25, shown by the thin dotted line in the middle right panel. The fragment starts from apocentre and initially moves inwards quickly, but is essentially circularised through damping in a single orbit. The difference in separation after 5 kyr is less than 1 au. In the second variant simulation (dashed black line), a fragment with double that eccentricity (corresponding to 0.5, higher than the maximum used for the population synthesis) is inserted. In this case, cir-cularisation happens in about three orbits and the fragment has moved ≈ 2 au further inwards (at 25 kyr) compared the one with lowest angular momentum deficit. This indicates that the initial eccentricity does not have a major impact on companions formed by DI, at least in the single fragment case. We discuss this further in Paper II.