| Issue |

A&A

Volume 705, January 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A183 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557209 | |

| Published online | 19 January 2026 | |

Dark-matter-powered Population III evolution: Lifetimes, rotation, and quasi-homogeneity in massive stars

1

I. Physikalisches Institut, Universitat zu Köln Zülpicher Str. 77 D-50937 Köln, Germany

2

Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia 530 McCormick Rd Charlottesville VA 22904, USA

3

Center for Astrophysics, Harvard and Smithsonian, 60 Garden St Cambridge MA 02138, USA

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

11

September

2025

Accepted:

5

November

2025

Population III stars supplied the first light and metals in the Universe, setting the pace of re-ionisation and early chemical enrichment. In dense halos, their evolution can be strongly influenced by the energy released when weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) are annihilated inside the stellar core. We followed the evolution of a 20 M⊙ Population III model with the GENEC code, adding a full treatment of spin-dependent WIMP capture and annihilation. Tracks were calculated for six halo densities from 108 to 3 × 1010 GeV cm−3 and three initial rotation rates between 0 and 0.4 v/vcrit. As soon as the capture product reaches ρχ σSD ≃ 2 × 10−28 GeV cm−1, the dark-matter luminosity rivals hydrogen fusion, stretching the main-sequence lifetime from about ten million years to more than a gigayear. The extra time allows meridional circulation to smooth out differential rotation; a star that begins at 0.4 v/vcrit finishes core hydrogen burning with near solid-body rotation and a helium core almost twice as massive as in the dark-matter-free case. Because the nuclear timescale is longer, chemically homogeneous evolution now sets in at only 0.2 v/vcrit, rather than the ≳ 0.5 v/vcrit required without WIMPs. For a star with 0.4 v/vcrit, the surface hydrogen fraction drops to X ∼ 0.27, helium rises to Y ∼ 0.73, and primary 14N increases by four orders of magnitude at He exhaustion. The star leaves the zero age main sequence cooler, at Teff ≈ 50 kK, and should display the strong N III and He II lines typical of a nitrogen-rich Wolf-Rayet analogue. Moderate rotation combined with plausible dark-matter densities can therefore drive primordial massive stars towards long-lived, quasi-homogeneous evolution with distinctive chemical and spectral signatures. Our tracks offer quantitative inputs for models of re-ionisation, for stellar archaeology, and for future attempts to constrain the microphysics of WIMPs through high-redshift observations.

Key words: stars: evolution / stars: massive / stars: Population III / dark matter / early Universe

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Understanding the nature of dark matter (DM) remains one of the most pressing challenges in astrophysics and cosmology. Observational evidence from galactic rotation curves, gravitational lensing, and cosmic microwave background anisotropies strongly suggests the existence of DM, which is believed to constitute about 85% of the matter content of the Universe (Planck Collaboration VI 2020). Despite its elusive nature, DM plays a crucial role in the formation and evolution of cosmic structures.

Among the various DM candidates, weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) are particularly compelling due to their natural emergence in extensions of the standard model of particle physics (Jungman et al. 1996; Bertone et al. 2005). WIMPs interact through gravity and potentially via weak-scale interactions, allowing them to scatter off baryonic matter and annihilate with each other. In regions of high DM density, such as the early Universe or the centres of galaxies and stars, WIMP annihilation can release significant amounts of energy (Bergström et al. 1998).

The first generation of stars, known as Population III (Pop III) stars, formed in DM halos at high redshifts (z ∼ 20–30; Bromm & Larson 2004; Maeder & Meynet 2012; Liu et al. 2025). These stars are thought to be massive and metal-free, playing a pivotal role in the re-ionisation of the Universe and the enrichment of the interstellar medium with heavy elements (Liu et al. 2021). The formation and evolution of Pop III stars are influenced by the conditions of the early Universe, including the presence of DM. In particular, the concept of ‘dark stars’ (DSs) has been proposed, where DM annihilation provides an additional energy source that can significantly alter stellar structure and evolution (Spolyar et al. 2008; Freese et al. 2010; Ilie et al. 2023b). These hypothetical stars form when the gravitational collapse of baryonic matter in early DM halos leads to the accumulation of both ordinary matter and DM particles. The annihilation of WIMPs within the star’s core can counteract gravitational contraction, resulting in stars that are cooler, larger, and have extended lifetimes compared to conventional Pop III stars (Freese et al. 2008b; Ilie et al. 2012; Rindler-Daller et al. 2015; Tan et al. 2024; Nandal et al. 2025b). The prolonged lifetimes and unique characteristics of DSs may leave observable imprints, such as distinct spectral features or anomalous elemental abundances, which could be probed by current-generation telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST; Zackrisson et al. 2010; Freese et al. 2016; Banik et al. 2019; Ilie et al. 2025).

The interaction between DM and stars has been extensively studied over the past few decades. Gould (1987) developed the theoretical framework for WIMP capture and annihilation within stars, laying the foundation for understanding how DM can influence stellar evolution. This framework was further refined to account for various stellar environments and DM properties (Press & Spergel 1985; Faulkner & Gilliland 1985). Subsequent works have explored the impact of DM on stellar evolution in greater detail, including the potential formation of DSs (Freese et al. 2008a; Ilie et al. 2012; Scott et al. 2009; Ilie et al. 2021). Studies have shown that DM annihilation can alter the temperature gradients within stars, affect nucleosynthesis processes, and modify the stellar evolution tracks on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (HRD; Taoso et al. 2008; Casanellas & Lopes 2011b,a). The effects of DM annihilation on Pop III stars, according to both rotating and non-rotating models, have significant implications for our understanding of the first stars and the role of DM in stellar physics (Yoon et al. 2008; Hirano et al. 2015; Stacy et al. 2012).

Tan et al. (2024) sub-classified Pop III stars into Pop III.1 and Pop III.2 types based on their formation environments and the influence of radiation feedback. Pop III.1 stars form in pristine environments without prior star formation, resulting in isolated, massive stars of up to several hundred solar masses (Hirano et al. 2014). In contrast, Pop III.2 stars form later, influenced by radiation and chemical feedback from earlier generations, leading to a broader mass spectrum and different formation pathways (Greif et al. 2012). The presence of DM can further complicate this classification, as DM annihilation may play a more pronounced role in the formation and evolution of Pop III.1 stars due to the higher DM densities in early halos (Natarajan et al. 2009). Recent simulations have investigated the interplay between DM annihilation and stellar rotation, suggesting that rotation can enhance the mixing processes within stars and affect the transport of angular momentum and chemical elements (Haemmerlé et al. 2020; Stacy et al. 2013). Understanding these effects is crucial for predicting the observational signatures of the first stars and their contribution to cosmic re-ionisation and early chemical enrichment (Bromm et al. 2009; Wise et al. 2012; Gondolo et al. 2022).

In this work we investigated the effects of DM annihilation on the evolution of rotating and non-rotating massive Pop III stars. Using updated stellar evolution models, we analysed how DM capture and annihilation influence stellar structure, lifetimes, and nucleosynthesis. By comparing models with and without rotation, we aim to elucidate the interplay between DM physics and stellar evolution in the context of primordial stars.

The paper is organised as follows: In Sect. 2 we describe the methods and numerical setup used in our simulations. In Sect. 3 we present the results of our models and discuss the implications for Pop III star evolution. Finally, in Sect. 5 we summarise our findings and outline prospects for future work.

2. Methods

In this work we modelled the impact of DM annihilation on Pop III stellar evolution by incorporating the capture and annihilation of WIMPs into the Geneva stellar evolution code (GENEC). Our formalism builds on that of Taoso et al. (2008), hereafter T08) while reflecting improvements in the underlying physics and numerical techniques (Ekström et al. 2012; Nandal et al. 2024, 2025a). In the following, we detail the methodology and present the relevant equations, clarifying all assumptions and definitions.

The evolution of the total number of WIMPs in the star, Nχ, is governed by

where Cc is the capture rate via WIMP–baryon scattering, Cs is the self-capture rate due to WIMP–WIMP interactions, A is the annihilation coefficient, representing the rate at which pairs of WIMPs annihilate, and E denotes the evaporation rate. For the massive stars studied here, both self-capture and evaporation are negligible; hence, these terms are set to zero in our models. The total number of WIMPs is defined as

with nχ (r) being the local WIMP number density and R∗ the stellar radius.

We adopted a Gaussian profile to describe the spatial distribution of WIMPs within the star:

where the characteristic radius,

marks the region where WIMP–baryon interactions are most effective. Here Tc and ρc are the central temperature and density, mχ is the WIMP mass, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and G is the gravitational constant.

2.1. Capture rate

Weakly interacting massive particles entering the star lose kinetic energy via scattering off baryons until they become gravitationally bound. The local differential capture rate is expressed as

The variables are defined as follows:

In these expressions, ρi(r) is the density profile of element i (with atomic mass Mi), σχ,N is the WIMP–baryon scattering cross-section (which can be spin-dependent or spin-independent), and ρχ and  are, respectively, the ambient WIMP density and velocity dispersion. The stellar velocity v∗ is assumed to be equal to

are, respectively, the ambient WIMP density and velocity dispersion. The stellar velocity v∗ is assumed to be equal to  . The escape velocity, v(r), is computed from

. The escape velocity, v(r), is computed from

where M(r′) is the mass enclosed within radius r′. The total capture rate is finally obtained by integrating Eq. (4) over the entire stellar volume:

2.2. Annihilation rate

Assuming that WIMPs are their own antiparticles (Jungman et al. 1996; Aprile et al. 2017), they can annihilate in the dense stellar core. The local energy generation rate per unit mass due to WIMP annihilation is given by

where ⟨σv⟩ is the thermally averaged annihilation cross-section, c is the speed of light, and ρ(r) is the local baryon density. The integrated annihilation coefficient is then defined as

We assumed that the totality of the annihilation energy is processed by the star. Hence,

is the net luminosity deposited in the star. Freese et al. (2010), Rindler-Daller et al. (2015), and Ilie et al. (2021, 2025) consider that a third of the energy is lost by neutrinos escaping the star.

2.3. Normalisation and equilibrium

A key unknown in our formulation is the normalisation constant (n0) of the WIMP density profile. To determine n0, we assumed that after a characteristic timescale,

the system attains equilibrium such that the rate of WIMP annihilation balances out the capture rate. Under the simplifying assumption that self-capture and evaporation are negligible, the equilibrium condition can be approximated by

Once Cc is computed via Eq. (6), n0 is adjusted in GENEC so that the energy injection from WIMP annihilation, as given by Eq. (7), satisfies this equilibrium condition. Although this approach involves approximations regarding the equilibrium timescale tχ, the resulting uncertainties remain within acceptable limits for our analysis. This methodology self-consistently integrates DM capture and annihilation into the stellar energy budget, allowing us to investigate how WIMP annihilation modifies stellar structure and evolution.

3. Results

We summarise the suite of 20 M⊙ Pop III star models in Table 1. Columns 1–4 list the model name and key initial parameters: ambient WIMP density ρχ, initial rotation (as a percentage of the critical velocity vcrit), and the spin-dependent WIMP scattering cross-section σSD. Columns 5–7 give selected results at the end of core hydrogen burning: the helium core mass MHe, the equatorial surface velocity veq, and the stellar lifetime. Non-rotating models (v/vcrit = 0%) are listed in the upper part of the table, followed by rotating cases (20%, 40%, and 60% of vcrit). In cases where the main-sequence (MS) evolution did not fully converge (defined here by central hydrogen mass fraction Xc reaching 10−3), the table entries are marked with an ‘X’. As seen in Table 1, increasing the ambient WIMP density (for fixed σSD) dramatically extends the MS lifetime of a 20 M⊙ star. For example, in the non-rotating sequence at σSD = 10−38 cm2, the lifetime grows from ∼9.6 Myr with no DM up to ∼8.44 × 103 Myr at the highest DM density (ρχ = 3 × 1010GeVcm−3). The helium core mass MHe remains around 5 M⊙ for those non-rotating models that complete H-burning, indicating that despite the vastly different MS durations, they synthesise similar helium cores. In contrast, the rotating models (which is discussed in Sect. 3.2) develop larger MHe and higher veq by MS termination due to rotational mixing. A second set of non-rotating models (Table 1, last rows) explores a lower cross-section σSD = 10−40 cm2 with proportionally increased ρχ: these yield evolution outcomes very similar to the σSD = 10−38 cases, reflecting the primary dependence on the product ρχσSD.

Simulation parameters.

3.1. Non-rotating models

3.1.1. Hertzsprung-Russell evolution

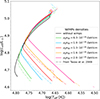

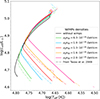

Figure 1 illustrates the evolutionary tracks of the non-rotating models in the HRD. Increasing the ambient WIMP density shifts the zero age main sequence (ZAMS) to markedly lower effective temperatures and slightly lower luminosities. Physically, the additional energy injection from WIMP annihilation in the stellar core inflates the star, increasing internal radiative pressure and yielding a larger radius (cooler Teff) at the ZAMS. Throughout the early MS, the energy output is dominated by WIMP annihilation rather than nuclear fusion. Consequently, the star undergoes only minimal hydrogen burning during this phase, and its track in the HRD remains near the ZAMS locus for an extended period. In the HRD (Fig. 1), this behaviour is seen as an initial clustering of the tracks at relatively cool Teff for high ρχσSD models. As evolution proceeds, however, the DM energy input gradually becomes less dominant. Once a significant amount of hydrogen is converted into helium in the core, the WIMP capture rate drops (since we assume purely spin-dependent capture; helium, with no nuclear spin, is ineffective at capturing WIMPs). Thereafter, nuclear energy production steadily increases and the star resumes a more conventional MS evolution. Accordingly, the HRD tracks for different ρχσSD eventually bend back towards higher Teff, converging with the track of a star without DM by the end of the MS. Aside from an initial offset in ZAMS position, the overall morphology of our HRD tracks with DM is similar to that found by Taoso et al. (2008, dashed curves in Fig. 1). Small quantitative differences (e.g. a slight shift in our ZAMS location) can be attributed to updates in the GENEC code since T08. Importantly, once WIMP annihilation becomes subdominant late in the MS, all tracks, with and without DM, converge to the same Hertzsprung–Russell endpoint.

|

Fig. 1. HRD from this work (solid lines) and T08 (dashed lines) for a static 20 M⊙ Pop III star surrounded by different WIMP densities (see the colour code). |

3.1.2. Main-sequence lifetimes

The non-rotating series in Table 1 quantifies the dramatic lifetime extension produced by WIMP heating. The reference model without DM completes core–hydrogen burning in 9.6 Myr, whereas a mild enhancement ρχ = 6.3 × 109 GeV cm−3 (63d9, ρχσSD = 6.3 × 10−29 GeV cm−1) already doubles the lifetime to 23.5 Myr. Further increases give 50.9 Myr at 1.0 × 1010 (1d10), 7.2 × 102 Myr at 2.0 × 1010 (2d10), and 8.4 Gyr at 3.0 × 1010 (3d10)–a factor of 103 relative to the standard Pop III case. The alternate sequence with σSD = 10−40 cm2 reproduces the same lifetimes when ρχ is increased by the same factor, demonstrating that the controlling parameter is the product ρχσSD.

The reference model without DM completes core–hydrogen burning in 9.6 Myr, whereas a mild enhancement ρχσSD = 6.3 × 10−29 GeV cm−1 (63d29) already doubles the lifetime to 23.5 Myr. Further increases give 50.9 Myr at 1.0 × 10−28 (1d28), 7.2 × 102 Myr at 2.0 × 10−28 (2d28), and 8.4 Gyr at 3.0 × 1028 (3d28) —a factor of 103 relative to the standard Pop III case. The alternate sequence with σSD = 10−40 cm2 reproduces the same lifetimes when ρχ is increased by the same factor, demonstrating that the controlling parameter is the product ρχσSD.

During the early MS, energy injection from WIMP annihilation maintains a comparatively cool, low-density core; hydrogen fusion therefore proceeds slowly, and the stellar structure evolves on an extended nuclear timescale. As hydrogen is converted to helium, spin-dependent capture weakens, nuclear burning gradually overtakes the DM contribution, and the model ultimately resumes a standard terminal-age MS path. For ρχσSD ≳ 10−28 GeV cm−1 the MS duration exceeds a gigayear, implying that such WIMP-supported Pop III stars could persist to low redshifts if their DM environment remains undisturbed.

3.1.3. Internal structure

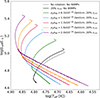

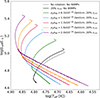

Figure 2 presents the response of the stellar core to increasing WIMP capture for seven central hydrogen mass fraction during the MS phase (from Xc = 0.70 to 0.005). The left-hand panel shows the central temperature Tc for a non-rotating star, while the right-hand panel displays a star rotating with initial velocity 20% of v. Both models are plotted against the product ρχσSD, which parametrises the WIMP capture rate.

|

Fig. 2. Central temperature as a function of WIMP density for a 20 M⊙ Pop III star without rotation (left) and with a rotation 20% of vcrit (right). Curves corresponding to different evolutionary stages (defined by the central hydrogen abundance) are plotted with spline interpolation; the dashed curves are taken from T08. |

At ZAMS (Xc = 0.70) the model without DM occupies (Tc, ρc)≃(8.0 × 107 K, 1.2 × 102 g cm−3). A tenfold increase in ρχσSD lowers each quantity by roughly one quarter, and at 3 × 10−28 GeV cm−1 both are reduced by nearly a factor of two, indicating that instead of hydrogen fusion, WIMP annihilation provides the dominant luminosity. The mid-MS curves (Xc = 0.40) illustrate how this stabilising influence persists. In the standard model the core has already contracted and heated to (9.5 × 107 K, 1.5 × 102 g cm−3), whereas DM–rich cores remain within ∼10% of their ZAMS state, confirming that the additional energy source largely suppresses Kelvin–Helmholtz contraction during the first few 107 yr.

Once hydrogen is exhausted, spin-dependent capture ceases and the tracks for all ρχσSD converge to a narrow locus around Tc ≃ 1.0–1.1 × 108 K and ρc ≃ 1.6–1.8 × 102 g cm−3. Thus, despite large differences during most of the extended MS, each model ultimately attains the core conditions required for helium ignition after WIMP heating subsides. In effect, DM energy support delays–but does not prevent–the standard contraction–heating sequence; the star therefore resumes canonical Pop III evolution once its hydrogen reservoir no longer sustains efficient WIMP capture.

3.2. Rotating models

Rotating Pop III models were evolved with GENEC ’s standard meridional-circulation and shear prescription. We first compared stars that begin at 20 % vcrit with the non-rotating sequence, then increased the spin to 40 and 60 % vcrit. Unless stated otherwise, the spin-dependent cross-section was σSD = 10−38 cm2. The companion grid with σSD = 10−40 cm2 reproduces the same trends after ρχ is raised by the same factor and is noted briefly in Sect. 3.1.2.

3.2.1. Moderate rotation (20 % vcrit) versus no rotation

The right-hand side of Fig. 2 shows the central temperature as a function of the product ρχσcrit for a Pop III rotating star 20% of vcrit. In opposition to the static case the temperature stays lower at every step during the MS. With the mixing the energy produce by WIMPs annihilation is transported outwards, keeping the core cooler.

Figure 3 shows that rotation leaves the ZAMS almost unchanged but shifts the subsequent DS phase upwards in luminosity. wtt_0.2v is ≃0.05 dex brighter and 5.0 × 102 K hotter, from the static model, at hydrogen exhaustion. With 1d28_0.2v the luminosity offset rises to 0.20 dex, while the temperature excess falls to 1.1 × 104 K because centrifugal support partly counteracts DM-driven contraction.

|

Fig. 3. Similar to Fig. 1 but with an initial rotation velocity of 20 % vcrit. The grey curve represents the non-rotating tracks. |

The higher L reflects a larger convective core: rotational mixing carries fresh H inwards and He outwards, raising the nuclear luminosity that supplements WIMP heating. Consequently the envelope expands less than in the non-rotating case, keeping the surface hotter for a given ρχ.

Quantitatively, the helium-core mass at MS exit grows from 5.06 M⊙ (wtt) to 5.29 M⊙ for wtt_0.2v, and from 5.19 M⊙ to 7.32 M⊙ for 1d28_new and 1d28_0.2v, respectively. The factor of 1.4 increase sets the stage for still greater differences at higher spin.

3.2.2. Faster rotation: 40–60 % vcrit

The 40% vcrit (63d29_0.4v) track in Fig. 4 is ≃0.3 dex more luminous and ∼1.6 × 104 K hotter than the 20% (63d29_0.2v) track at the terminal-age MS (Xc ≃ 10−3). The luminosity rise follows directly from the larger helium core: MHe = 13.28 M⊙ versus 7.32 M⊙, a factor of 1.8 increase that boosts the nuclear energy release once WIMP heating subsides. Centrifugal support lowers the effective gravity at the stellar surface by ≈12% (evaluated at the equator), reducing the photospheric temperature despite the higher L. Rotationally induced meridional circulation also transports entropy outwards, inflating the envelope by ∼20% in radius relative to the 20% model. The net result is a star that is brighter but slightly cooler, sliding upwards and rightwards in the HRD. A higher DM supply (ρχσSD = 1.0 × 10−28 GeV cm−1 (1d28_0.4v)) produces an identical differential shift.

|

Fig. 4. HRD of a Pop III star of 20 M⊙, from the ZAMS to the end of the MS, for a WIMP density of ρχσSD = 6.3 ⋅ 10−29 GeV ⋅ cm−1, for an initial velocity at 20% and 40% of the critical velocity of the star. |

Figure 5 demonstrates that DM longevity enhances the surface spin-up driven by internal angular-momentum transport. At ρχ = 6.3 × 109 GeV cm−3 the 40 %model (63d29_0.4v) attains Ω/Ωcrit = 0.99 at the end of MS, whereas the same model without DM has reached only 0.9 by that age. The higher DM density extends the Kelvin–Helmholtz spin-up phase to ∼700 Myr, doubling the time available for meridional circulation to transfer core angular momentum outwards. In the 60% sequence the stellar surface meets the break-up limit at ≃90 Myr, long before the core hydrogen fraction falls below 0.6; the computation therefore halts. This behaviour implies that any Pop III star born with v ≳ 0.5 vcrit in a DM halo of ρχσSD = 1 ⋅ 10−28 GeV ⋅ cm−1 will likely reach critical rotation well inside its DM-supported phase.

|

Fig. 5. Surface Ω/Ωcrit versus time for 20 (bottom), 40 (middle), and 60% (top) vcrit models at several WIMP densities, with a colour scheme similar to that of Fig. 3. |

Internal rotation profiles in Fig. 6 show how DM-induced longevity enforces nearly solid-body rotation. All models present a constant rotation profile at the mid-MS (Xc = 0.37), while at the end-MS the contrast between the centre and surface is ≃15% for ρχσSD < 1.0 × 10−28 GeV cm−1 and ≲1% for the all other models, highlighting that DM energy input, by prolonging the MS by several orders of magnitude, gives rotation enough time to homogenise the interior angular momentum.

|

Fig. 6. Angular-velocity profile, Ω(m), at mid-MS (left) and MS end (right) for different WIMP densities and initial velocities. |

3.2.3. Main-sequence lifetimes

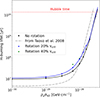

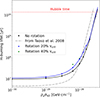

Lifetimes in Fig. 7 underline the synergy of rotation and DM. At ρχσSD = 6.3 × 10−29 GeV cm−1 the MS lasts 23.5, 34.1, and 48.4 Myr for 0, 20, and 40% vcrit, respectively; at ρχσSD = 1.0 × 10−28 GeV cm−1 the sequence reads 50.9, 84.2, and 92.0 Myr. The absolute gain from rotation is largest at intermediate DM supply, where nuclear burning still contributes appreciably and can benefit from fresh H mixed inwards. For ρχσSD ≳ 2 × 10−28 GeV cm−1 the non-rotating lifetime already exceeds 0.7 Gyr; rotation adds only a ∼10% increment because WIMP heating so completely suppresses fusion that additional mixing has little leverage. Repeating the 20 and 40% sequences with σSD = 10−40 cm2 and proportionally larger ρχ reproduces the HRDs, core masses, and lifetimes to within 3% of the values above; see Table 1.

|

Fig. 7. MS lifetime versus ρχ for 0 (black), 20 (blue), and 40% vcrit (green). The dashed grey line is taken from T08 and describes a static 20 M⊙ star. |

Rotation reinforces the effects of DM heating by (i) raising the surface luminosity at fixed ρχ, (ii) driving the star towards near-solid-body rotation, (iii) building substantially larger helium cores, and (iv) further extending the already prolonged MS lifetime. At sufficiently high spin and DM density the star approaches critical rotation well before core hydrogen exhaustion, a regime requiring dedicated treatment of centrifugal mass loss that lies beyond the scope of the present work.

3.3. Chemical abundance evolution in DM-supported Pop III stars

Figure 8 shows how DM heating and rotation reshape the chemical abundances in a 20 M⊙ Pop III star with WIMPs and rotation. Four evolutionary checkpoints are shown: mid–H burning (Xc ≃ 0.37), end of H burning (Xc ≃ 10−3), mid–He burning (Yc ≃ 0.50), and end of He burning (Yc ≃ 10−3). The centre is fully convective so the central abundance, noted Ac with A an arbitrary element, is the same across the core. As is taken at the stellar surface.

|

Fig. 8. Abundances of the main elements inside a 20 M⊙ star with ρχσSD = 1 ⋅ 10−28 GeV ⋅ cm−1 at 20% of vcrit initially. |

3.3.1. H and He abundances

For a star without DM and rotation the surface abundances remain constant during evolution with Xs = 0.75 and Ys = 0.25. Table 2 shows that these abundances do not vary between models without WIMPs, either with rotation (wtt_0.2v) or without rotation (wtt), and the model with WIMPs but no rotation (1d28_new). The only differences appear in the model combining WIMPs and rotation, 1d30_0.2v. In the middle of the MS the gradient from core to surface decreases from ΔX = ΔY = 0.38 to ΔX = ΔY = 0.20, caused by higher He and lower H surface abundances due to homogenisation.

Abundances at the core and at the surface as well as the gradient between abundances (ΔA = |Ac − As|) for both different elements and different initial conditions of a 20 M⊙ Pop III star.

At higher spins (1d28_0.4v, not in Table 2), rotation alone nearly achieves full homogenisation, with ΔX = ΔY = 0.10 in the middle of MS (Xs = 0.47, Ys = 0.53). At higher WIMP density (3d28_0.2v, not in Table 2) full homogenisation is almost reached, with ΔX = ΔY = 0.02 in the middle of MS (Xs = 0.40, Ys = 0.60). Adding DM to rotation extends the period over which the star remains mixed. Observable effects include helium-enriched surfaces and weaker core–envelope composition contrasts, both of which alter ionising spectra and late-stage yields.

3.3.2. CNO abundance patterns and primary nitrogen

Figure 8 and Table 2 show the mass fractions of the main CNO isotopes (12C, 14N, and 16O); neon is not included. The figure shows a sharp CNO spike confined inside the helium core (m/M ≲ 1/3). During the MS the abundances remain below 10−8 for X12C, 10−7 for X14N, and 10−9 for X16O, which is consistent across all initial conditions. Models without rotation keep metal-free envelopes, while model wtt_0.2v reaches X12C = 2.8 × 10−14, X14N = 6.6 × 10−12, and X16O = 1.3 × 10−13 at the end of the MS. Adding DM with rotation, in model 1d28_0.2v, raises the surface abundances by a factor of ≈102 at the end of the MS, giving X12C = 1.33 × 10−12, X14N = 2.7 × 10−10, and X16O = 4.8 × 10−12.

As with H and He, stronger rotation and higher WIMP density enhance mixing and increase the CNO surface abundances. In model 1d28_0.4v the values are X12C = 4.4 × 10−11, X14N = 6.9 × 10−9, and X16O = 9.6 × 10−11. In model 3d28_0.2v the values are X12C = 2.6 × 10−11, X14N = 4.3 × 10−9, and X16O = 6.3 × 10−11. Higher rotation mixes the heavier elements (12C, 14N, and 16O) more efficiently than higher WIMP density, which instead enhances the mixing of H and He by producing lower gradients for these elements.

3.3.3. Supernova remnant yields

We did not push the computations until the end of core Si burning to better produce remnant masses, and we are aware that physics of calculating remnant masses is uncertain. However, we can nonetheless provide a first-order estimate on the remnant masses using the two formulations widely available in the literature. The first is Maeder (1992), where they find a remnant mass of 2.14 M⊙ for an initial non rotating star of 20 M⊙ (their Table 4). They computed this mass by considering that all the skin layers have been ejected by the supernova explosion. Second one is Patton et al. (2022), they use non rotating models but take binary interactions into account. They find a mass of ≈5.7 M⊙ (Fig. 1). The discrepancy between the two values comes from different methodology to determine the remnant mass, and highlight the difficulty in estimating these values.

In this work we computed the mass of each element expected in the future supernova remnant (SNR) yields. For this we integrated the mass at the end of He burning (Yc ≃ 10−3) from the edge of the helium core (X14C < 10−3) to the surface for each element. The results are summarised in Table 3. The integrated masses of H and He are ∼9 M⊙ and ∼6 M⊙, except for model 1d28_0.2v where the values are ∼5 M⊙ and ∼8 M⊙. This corresponds to an external layer that is 45% poorer in H and 33% richer in He. Nitrogen follows a similar trend, with a mass five times higher for 1d28_0.2v. Oxygen yields are two orders of magnitude larger in rotating stars, wtt_0.2v and 1d28_0.2v (> 10−6 compared to ∼3 × 10−8), and in 1d28_0.2v they are eight times higher than in the DM-free rotating model wtt_0.2v.

Mass fraction for H, He, C, N, O, and Ne outside the helium core supposedly ending up in the SNR.

For the other elements the trends are less clear. The highest carbon yield is in model wtt (7.3 × 10−5) and the lowest is in wtt_0.2v (1.8 × 10−5). The trend reverses in DM models, but the difference is negligible. Neon yields are one order of magnitude higher in 1d28_0.2v (4.7 × 10−10) compared to wtt_0.2v (2.7 × 10−11), while they remain relatively similar in the static models wtt and 1d28 (9.6 × 10−10 and 2.7 × 10−10).

If we consider that the remnant mass will be the remaining helium core while the surface layers are ejected by the supernova explosion (similarly as in Maeder 1992), we get 4.8 M⊙ for wtt, 5.1 M⊙ for 1d28_new, 5.0 M⊙ for wtt_0.2v, and 7 M⊙ for 1d28_0.2v. The masses are more similar to Patton et al. (2022) than Maeder (1992), and with a remnant mass ≈40% higher for the star with DM and rotation. However, these results are to be taken carefully as we do not compute the models until pre-supernova stage.

In conclusion, the chemical composition of SNRs may provide a way to probe DM in Pop III stars. The rotating model with WIMPs is the most promising as it shows increased He, N, and O yields together with lower H. Carbon and neon are not good tracers because their SNR abundances differ little from DM-free models. The remnant masses could be a way to detect those objects as well, albeit more work needs to be done regarding this topic.

3.3.4. DM-induced mixing of H and He

The integrated masses of H and He are ∼9 M⊙ and ∼6 M⊙, respectively, except for 1d28_0.2v where the integrated masses are ∼5 M⊙ and ∼8 M⊙, respectively, i.e. the external part of the star is 45% poorer in H and 33% richer in He. N has a similar trend with a mass 5 times higher for 1d28_0.2v. The oxygen yields are two orders of magnitude more massive for rotating stars, wtt_0.2v and 1d28_0.2v (> 10−6 compare to ∼3 ⋅ 10−8), especially for 1d28_0.2v, which is 8 times higher than the DM-less rotating star wtt_0.2v.

For the two other elements, finding a general trend is more difficult. The highest carbon yields is present for wtt (7.3 ⋅ 10−5) while the lowest is present for wtt_0.2v (1.8 ⋅ 10−5). The opposite is true when the star is surrounded by DM, but with a negligible difference. The Neon yield is one order of magnitude higher for 1d28_0.2v model (4.7 ⋅ 10−10) compare to wtt_0.2v (2.7 ⋅ 10−11), while they are relatively similar for the static stars, wtt and 1d28 (9.6 ⋅ 10−10 and 2.7 ⋅ 10−10).

In conclusion, a way to look for DM in Pop III stars is to look at the chemical composition of the SNR from those stars. The rotating model with WIMPs is the most promising as it exhibits an increase in He, N and O, while decreasing for H. C and Ne do not seem to be good tracers to detect stars surrounded by DM as their proportion in SNR do not differ significantly from the DM-less models.

4. Discussion

The 20 M⊙ mass prescription chosen in this work is a suitable candidate for type II supernova (core collapse supernova). Additionally, 20 M⊙ is a classical choice when looking at initial mass functions not only for in local universe but also for high redshift universe, this means if stars powered by DM exist, it would be a much higher chance to observe such a star (ξ(m)Δm ≈ 6 × 10−3). Lastly, the lifetime of this star without any DM is long enough for any rotation processes to be significant (≈9 Myr for static and ≈10 Myr for rotating star (Ekström et al. 2012). As an example, if we were to take a 60 M⊙ star, its lifespan would decrease to a few million years and the chemical mixing would be less significant. A rotating 20 M⊙ star, whose internal structure is composed of a convective core and a radiative envelope, does not produce a homogeneous evolution. However, adding DM to this star, we indeed find homogeneous evolution due to lifetime extension, and allowing the transport of chemicals even through the radiative zones. In addition, the likelihood of finding a 20 M⊙ star, despite there being hints of a top heavy initial mass function for Pop III stars, is much higher than, for instance, 60 M⊙ stars (Chen et al. 2020). This makes the 20 M⊙ model a viable case for comparison in this work.

The annihilation of WIMPs reshapes the internal composition of our 20 M⊙ grid. The non-rotating control model builds a steep H–He discontinuity with ΔX ≃ 0.38 at m/M ≃ 0.22 and retains a pristine envelope at X ≈ 0.75. When DM heating is included with vini = 0.40 vcrit the star evolves quasi-homogeneously and the gradient falls to ΔX ≃ 0.10 at H exhaustion. The surface nitrogen mass fraction rises from 6.6 × 10−12 to 2.7 × 10−10 at the end of MS. These values exceed the primary nitrogen reported by Yoon et al. (2008) for the same mass. The non-rotating DM case shows weaker enrichment and thus confirms that DM and rotation together drive the extreme CNO yields.

Lifetimes scale with the product ρχσSD as anticipated by Taoso et al. (2008). The reference model without DM leaves the MS after 9.6 Myr. At ρχ = 6.3 × 109 GeV cm−3 the lifetime doubles to 23.5 Myr, matching the 20 M⊙ result of Scott et al. (2009) to within 5%. Raising the density to 1.0 × 1010 extends the lifetime to 50.9 Myr, i.e. by a factor of 5.3, which agrees with the 4.9 reported by Casanellas & Lopes (2011a). Beyond 2 × 1010 our models fail to exhaust hydrogen within a Hubble time, reproducing the threshold identified by Taoso et al. (2008). Switching to σSD = 10−40 cm2 and scaling ρχ by 100 recovers identical lifetimes, confirming that τMS depends only on the capture product.

Rotation changes the outcome only when DM prolongs the nuclear timescale. A vini = 0.40 vcrit model without DM ends core-H burning with Ωcore/Ωsurf ≃ 3 and MHe = 6.8 M⊙. Introducing ρχ = 1.0 × 1010 GeV cm−3 lowers the ratio to 1.08 (8%) and raises the core mass to 13.3 M⊙. These values fulfil the quasi-chemically homogeneous condition τmix < τnuc proposed by Yoon et al. (2008). With DM, the same state appears at 0.20 vcrit. This halves the chemically homogeneous evolution threshold compared with the ≳0.50 vcrit requirement in DM-free Pop III models. We conclude that WIMP energy support, rather than centrifugal mixing alone, dictates the onset of chemical homogeneity in primordial massive stars.

Figure 2 shows the central temperature Tc versus ρχσSD for a rotating 20 M⊙ Pop III model with WIMP annihilation, with stages defined by Xc and dashed reference curves from T08. At the ZAMS the WIMP model is 26% cooler and 55% larger with Teff ≈ 50 kK and R ≈ 2.8 R⊙ compared to the DM–free model with Teff ≈ 63 kK and R ≈ 1.8 R⊙. This inflation follows from annihilation heating, which supplies part of the luminosity and lowers the nuclear rate, and Tc, which in turn increases the core entropy. At later times the annihilation rate drops and static models differ by only 2–8% in radius and by less than 3% in temperature so their structures converge. In the rotating WIMP model the trend reverses after the early MS and the radius becomes smaller by up to 17% while Teff becomes higher by 14–20%. Rotation maintains strong mixing and flattens the μ gradient, which enriches the envelope in He and lowers the opacity. Therefore, the Teff rises at fixed luminosity and the star contracts. The core remains cooler throughout, because mixing spreads the annihilation power and throttles nuclear burning.

5. Conclusions

We have computed the first grid of 20 M⊙ Pop III models that self-consistently include WIMP capture, annihilation, and rotation. The grid spans six ambient DM densities (108–3 × 1010 GeV cm−3) and three initial spins (0, 0.20, and 0.40 vcrit), enabling a controlled comparison of non-rotating, rotating, DM-free, and DM-rich tracks.

-

Main-sequence longevity. WIMP annihilation lengthens the lifetime of a 20 M⊙ Pop III star from ∼10 Myr to gigayear scales once the capture product exceeds ρχσSD ∼ 2 × 10−28 GeV cm−1. The vastly slower nuclear clock lets rotation and mixing act for orders of magnitude longer, reshaping subsequent feedback on the host halo.

-

Rotation driven towards solid body and helium-core growth. In DM-rich tracks, a model born at 0.40 vcrit ends core-H burning with only a few-percent shear and a helium core roughly twice the mass of its DM-free counterpart. Near-rigid rotation suppresses shear instabilities yet sustains meridional circulation, enhancing fuel transport and setting the stage for energetic late phases.

-

Central structure stabilisation. Continuous DM heating holds Tc and ρc nearly constant during most of the hydrogen burning, delaying Kelvin–Helmholtz contraction until spin-dependent capture ceases. This stabilisation maintains a low-density core that favours efficient mixing and prolongs the homogeneous phase.

-

Chemically homogeneous evolution at moderate spin rates. DM support lengthens τnuc such that Eddington–Sweet circulation overwhelms it even at 0.20 vcrit, while DM-free stars need ≳0.50 vcrit. Quasi-homogeneity flattens the H–He profile, keeps fresh fuel in the core, and produces progenitors suitable for collapsar-type explosions.

-

Surface H/He and CNO patterns with primary nitrogen. Rotation and DM mixing lowers the surface hydrogen to X ∼ 0.53, raises helium to Y ∼ 0.47, and boosts 12C, 14N, and 16O by two orders of magnitude relative to classical Pop III stars.

-

Spectral signatures. The best chance we have of detecting DM is to study rotating Pop III stars believed to be surrounded by DM. They live longer than their static counterparts and will produce SNRs rich in He, N, and O and poor in H; this is due to modified outer layer abundances that are in turn due to more efficient mixing. Additionally, these stars begin their evolution as cool and bloated objects at the ZAMS but become hotter and more compact throughout the evolution compared to classical baryonic Pop III stars.

Future work will expand the mass range to 40–120 M⊙ and probe halo densities above 3 × 1010 GeV cm−3. Spin-independent capture on metals will be added to follow late evolutionary phases. Magnetic torques and mass loss will be coupled to test whether DM-supported fast rotators reach critical spin and launch chemically enriched winds. Synthetic spectra across the UV–IR range will quantify N III and He II diagnostics and calibrate ionising photon budgets for re-ionisation models. Yield calculations will track 22Ne and heavy-element production, which will be compared with N-rich extremely metal-poor stars. Finally, models of 103–105 M⊙ protostars with sustained DM heating will explore the formation of supermassive DSs and the seeds of early quasars, which could be observed by the JWST (see Ilie et al. 2023a for an analysis of recent observations of quasars that could be DS products).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Marco Taoso and Prof. Georges Meynet for their valuable comments and feedback on the aspects of DM annihilation and rotation. Anaïs Pauchet would like to thank her supervisor Pr. Stefanie Walch for her supervision and encouragement towards the project. AP was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – Project-ID 500700252 – SFB 1601. DN was supported by the Swiss National Science Fund (SNSF) Postdoctoral Fellowship, grant number: P500-2235464 and by the Virginia Initiative of Theoretical Astronomy (VITA) Fellowship.

References

- Aprile, E., Aalbers, J., Agostini, F., et al. 2017, Phys. Rev. Lett., 119, 181301 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Banik, N., Tan, J. C., & Monaco, P. 2019, MNRAS, 483, 3592 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bergström, L., Ullio, P., & Buckley, J. H. 1998, Astropart. Phys., 9, 137 [Google Scholar]

- Bertone, G., Hooper, D., & Silk, J. 2005, Phys. Rep., 405, 279 [Google Scholar]

- Bromm, V., & Larson, R. B. 2004, ARA&A, 42, 79 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bromm, V., Yoshida, N., Hernquist, L., & McKee, C. F. 2009, Nature, 459, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Casanellas, J., & Lopes, I. 2011a, ApJ, 733, L51 [Google Scholar]

- Casanellas, J., & Lopes, I. 2011b, MNRAS, 410, 535 [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. H., Chen, K. J., Tsai, S. H., & Whalen, D. 2020, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2010.02212] [Google Scholar]

- Ekström, S., Georgy, C., Eggenberger, P., et al. 2012, A&A, 537, A146 [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner, J., & Gilliland, R. L. 1985, ApJ, 299, 994 [Google Scholar]

- Freese, K., Bodenheimer, P., Spolyar, D., & Gondolo, P. 2008a, ApJ, 685, L101 [Google Scholar]

- Freese, K., Spolyar, D., & Aguirre, A. 2008b, JCAP, 2008, 014 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Freese, K., Ilie, C., Spolyar, D., Valluri, M., & Bodenheimer, P. 2010, ApJ, 716, 1397 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Freese, K., Rindler-Daller, T., Spolyar, D., & Valluri, M. 2016, Rep. Prog. Phys., 79, 066902 [Google Scholar]

- Gondolo, P., Sandick, P., Shams Es Haghi, B., & Visbal, E. 2022, ApJ, 935, 11 [Google Scholar]

- Gould, A. 1987, ApJ, 321, 560 [Google Scholar]

- Greif, T. H., Bromm, V., Clark, P. C., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 424, 399 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Haemmerlé, L., Mayer, L., Klessen, R. S., et al. 2020, Space Sci. Rev., 216, 48 [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, S., Hosokawa, T., Yoshida, N., et al. 2014, ApJ, 781, 60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, S., Hosokawa, T., Yoshida, N., Omukai, K., & Yorke, H. W. 2015, MNRAS, 448, 568 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ilie, C., Freese, K., Valluri, M., Iliev, I. T., & Shapiro, P. R. 2012, MNRAS, 422, 2164 [Google Scholar]

- Ilie, C., Levy, C., Pilawa, J., & Zhang, S. 2021, Phys. Rev. D, 104, 123031 [Google Scholar]

- Ilie, C., Freese, K., Petric, A., & Paulin, J. 2023a, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2312.13837] [Google Scholar]

- Ilie, C., Paulin, J., & Freese, K. 2023b, Proc. Nat. Academy Sci., 120, e2305762120 [Google Scholar]

- Ilie, C., Shafaat Mahmud, S., Paulin, J., & Freese, K. 2025, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2505.06101] [Google Scholar]

- Jungman, G., Kamionkowski, M., & Griest, K. 1996, Phys. Rep., 267, 195 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B., Sibony, Y., Meynet, G., & Bromm, V. 2021, MNRAS, 506, 5247 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B., Kessler, D., Gessey-Jones, T., et al. 2025, MNRAS, 541, 3113 [Google Scholar]

- Maeder, A. 1992, A&A, 264, 105 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Maeder, A., & Meynet, G. 2012, Rev. Modern Phys., 84, 25 [Google Scholar]

- Nandal, D., Meynet, G., Ekström, S., et al. 2024, A&A, 684, A169 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nandal, D., Buldgen, G., Whalen, D. J., et al. 2025a, A&A, 701, A262 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nandal, D., Topalakis, K., Tan, J. C., et al. 2025b, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2507.00870] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, A., Tan, J. C., & O’Shea, B. W. 2009, ApJ, 692, 574 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, R. A., Sukhbold, T., & Eldridge, J. J. 2022, MNRAS, 511, 903 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Planck Collaboration VI. 2020, A&A, 641, A6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Press, W. H., & Spergel, D. N. 1985, ApJ, 296, 679 [Google Scholar]

- Rindler-Daller, T., Montgomery, M. H., Freese, K., Winget, D. E., & Paxton, B. 2015, ApJ, 799, 210 [Google Scholar]

- Scott, P., Fairbairn, M., & Edsjö, J. 2009, MNRAS, 394, 82 [Google Scholar]

- Spolyar, D., Freese, K., & Gondolo, P. 2008, Phys. Rev. Lett., 100, 051101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy, A., Greif, T. H., & Bromm, V. 2012, MNRAS, 422, 290 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy, A., Greif, T. H., Klessen, R. S., Bromm, V., & Loeb, A. 2013, MNRAS, 431, 1470 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J. C., Singh, J., Cammelli, V., et al. 2024, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2412.01828] [Google Scholar]

- Taoso, M., Bertone, G., Meynet, G., & Ekström, S. 2008, Phys. Rev. D, 78, 123510 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wise, J. H., Turk, M. J., Norman, M. L., & Abel, T. 2012, ApJ, 745, 50 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.-C., Iocco, F., & Akiyama, S. 2008, ApJ, 688, L1 [Google Scholar]

- Zackrisson, E., Scott, P., Rydberg, C.-E., et al. 2010, ApJ, 717, 257 [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Abundances at the core and at the surface as well as the gradient between abundances (ΔA = |Ac − As|) for both different elements and different initial conditions of a 20 M⊙ Pop III star.

Mass fraction for H, He, C, N, O, and Ne outside the helium core supposedly ending up in the SNR.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. HRD from this work (solid lines) and T08 (dashed lines) for a static 20 M⊙ Pop III star surrounded by different WIMP densities (see the colour code). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Central temperature as a function of WIMP density for a 20 M⊙ Pop III star without rotation (left) and with a rotation 20% of vcrit (right). Curves corresponding to different evolutionary stages (defined by the central hydrogen abundance) are plotted with spline interpolation; the dashed curves are taken from T08. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Similar to Fig. 1 but with an initial rotation velocity of 20 % vcrit. The grey curve represents the non-rotating tracks. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. HRD of a Pop III star of 20 M⊙, from the ZAMS to the end of the MS, for a WIMP density of ρχσSD = 6.3 ⋅ 10−29 GeV ⋅ cm−1, for an initial velocity at 20% and 40% of the critical velocity of the star. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Surface Ω/Ωcrit versus time for 20 (bottom), 40 (middle), and 60% (top) vcrit models at several WIMP densities, with a colour scheme similar to that of Fig. 3. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Angular-velocity profile, Ω(m), at mid-MS (left) and MS end (right) for different WIMP densities and initial velocities. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. MS lifetime versus ρχ for 0 (black), 20 (blue), and 40% vcrit (green). The dashed grey line is taken from T08 and describes a static 20 M⊙ star. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Abundances of the main elements inside a 20 M⊙ star with ρχσSD = 1 ⋅ 10−28 GeV ⋅ cm−1 at 20% of vcrit initially. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$$ \begin{aligned} \frac{\mathrm{d}C_c(r)}{\mathrm{d}V}&= \left(\frac{6}{\pi }\right)^{1/2} \sigma _{\chi ,N} \frac{\rho _i(r)}{M_i} \frac{\rho _\chi }{m_\chi } \frac{v^2(r)}{\bar{v}^2} \frac{\bar{v}}{2\eta A^2} \nonumber \\&\quad \times \left\{ \left(A_+A_- - \frac{1}{2}\right) \left[\chi (-\eta ,\eta ) - \chi (A_-, A_+)\right] \right. \nonumber \\&\quad \left. + \frac{1}{2}A_+ e^{-A_-^2} - \frac{1}{2}A_- e^{-A^2_+} - \frac{1}{2} \eta e^{-\eta ^2} \right\} . \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa57209-25/aa57209-25-eq5.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} A^2&= \frac{3\,v^2(r)\,\mu }{2\bar{v}^2\,\mu _-^2}, \qquad&A_\pm&= A \pm \eta , \\ \eta ^2&= \frac{3\,v_*^2}{2\bar{v}^2}, \qquad&\chi (a,b)&= \frac{\sqrt{\pi }}{2}\left[{\text{ Erf}}(b)-{\text{ Erf}}(a)\right], \\ \mu _i&= \frac{m_\chi }{M_i}, \qquad&\mu _-&= \frac{\mu _i-1}{2}. \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa57209-25/aa57209-25-eq6.gif)