| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A117 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Astrophysical processes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555403 | |

| Published online | 04 February 2026 | |

Looking for observational signatures of early binary black hole systems

1

Université Paris Cité, CNRS, Astroparticule et Cosmologie F-75013 Paris, France

2

Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Cité, CEA, CNRS, AIM 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

6

May

2025

Accepted:

15

November

2025

Context. Many recent studies have focused on the observables associated with near-merger binary black-holes (BBHs) embedded in a circumbinary disk, but we still lack knowledge of the observables of BBHs in their early stage. In this stage, the separation between the two black holes is so large that both black holes could potentially retain the individual accretion disks that existed before the BBH was created. For such early BBH systems, it is interesting to look for observables originating in these individual disks, as their structure is likely to differ from that of mini-disks that are often observed in simulations of later BBH stages.

Aims. In a companion paper, we presented a set of hydrodynamical simulations of an individual disk surrounding a primary black hole while it was affected by a secondary black hole in an early BBH system. This created three well-known characteristic features in the disk structure. Here, we explore the imprints of these three features on the observables associated with the thermal emission of the preexisting black hole disk. Our aim was twofold: we first determined which observables were best suited for detecting these early systems, and second, we determined what we might extrapolate about these systems based on observations.

Methods. We used general relativistic ray-tracing in order to produce synthetic observations of the thermal emission emitted by early BBHs with different mass ratio and separations in order to search for distinctive observational features of early systems.

Results. We found that, in the case of early BBHs with preexisting disk(s), a necessary, although not unique, observational feature is the truncation of their disk(s).

Conclusions. This observable might be used for an automated search of potential BBHs and to potentially rule out some existing candidates.

Key words: accretion, accretion disks / binaries: general / stars: black holes

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

As existing and future gravitational wave (GW) detectors will provide rather uncertain sky localisations for the earliest detections of the sources, it is therefore interesting to know the radiative emission of a pre-merger binary black hole (BBH) system. Indeed, it would help us to find BBHs faster within the GW localisation box through scans with electromagnetic telescopes. At the same time, this knowledge will give us access to the structure and dynamics of the gas from the early to the last stage of the BBH merger. As we want to be able to explore the consequences of this strong, and rapidly evolving, gravity on the accretion-ejection structures, the best system to follow would be a BBH of ∼40 M⊙ because these BBHs will go through a wide dynamical range within the months prior to the merger, which would allow us to explore the transition from early in the binary formation to the last stages of the merger. The problem is that these systems might not be in a gas-rich environment and are therefore not propitious for electromagnetic detection. Hence, if we want to study the dynamical evolution of the accretion-ejection structure at different stages of the pre-merger, it is therefore more interesting to study more massive systems and search for a sample of these systems at different stages instead of following one system through its entire life span. In that respect, we not only needed to determine the relevant observables associated with each stage, but also verify which are easier to detect through a full scan of the sky or a targeted search. This paper is part of a series, each focusing on a different stage1 of the pre-merger system and searches for the optimal detection technic and period for the system. The focus so far was on late pre-merger systems, that are embedded in a circumbinary disk, and on their observables (Shi et al. 2012; Noble et al. 2012; D’Orazio et al. 2013; Farris et al. 2014; Noble et al. 2021; Mignon-Risse et al. 2025). As many of these observables are related to features of the circumbinary disk (CBD, Shi et al. 2012; Mignon-Risse et al. 2025) and are not intrinsic to the BBH, it seems important to look for observational signatures of BBHs in the absence of a CBD. Indeed, in the early phase of a galaxy merger, both black holes could feel each others’ pull before any gas could have the time to circularize around such a wide binary, hence the early stage. Alternatively, the CBD actually exists but is too faint to be detectable due to the lack of gas in the vicinity. Its observable, therefore, cannot be used to identify the BBH. At the same time, the individual black holes might still have retained their preexisting disks, and the imprint of the other black hole on these disks might lead to a new method to detect early BBHs.

One of the reasons this early pre-merger phase has not been as extensively studied as the CBD phase is that new observations of an early systems would not lead to a merger occurring over a human timescale for supermassive BBHs and secondly stellar mass systems seem to be located in a more rarefied gas environment, hence lacking electromagnetic emission. Nevertheless, these early systems provide the physical conditions from which circumbinary structures are formed. The ability to detect these early systems would give us information on the earliest stage of the merger journey, especially about the evolution of the accretion-ejection structures up to the merger. Ultimately, this knowledge might be used to improve near-merger simulations, which might then be used to identify systems closer to their merger. Access to the observables in the early stage would also be helpful for archival searches ahead of the LISA mission because many of the objects that would merge within the LISA mission have spent some time in the early stage during the time span of existing archival data. In the context of stellar mass BBHs, it is noteworthy that this detection of an early system with a gas-rich environment system, as unlikely as it is, would be an invaluable asset because we would be able to follow the system up to the merger (which would occur between 10 to 50 years after the first detection), which would provide access to its electromagnetic emission prior to the merger. This is a pathway to the formation of the circumbinary structure.

In the companion paper, Casse et al. (2025), we investigated the effect of the gravity of one of the black holes composing an early BBH upon the accretion disk surrounding the other black hole. The simulations presented in Casse et al. (2025) were the first to depict the full structure of preexisting disks in early BBHs from their last stable orbit to their outer edges for a wide variety of black hole mass ratios and separations. In agreement with the earliest studies of binary systems (Paczynski 1977; Papaloizou & Pringle 1977; Eggleton 1983; Sawada et al. 1986; Spruit 1987; Whitehurst & King 1991; Artymowicz & Lubow 1994; Lubow 1994; Godon et al. 1998; Pichardo et al. 2005; Miranda & Lai 2015; Martin & Lubow 2011; Ju et al. 2016; Zhu et al. 2016; Rafikov 2016; Bae & Zhu 2018; Westernacher-Schneider et al. 2024), we identified three main effects on preexisting disks that are likely to alter their electromagnetic thermal emissions. With the help of the analytical fits provided by Casse et al. (2025) that quantified these features, we assess the detectability of these effects in order to determine whether they might contribute to the identification of early BBH systems. Our paper is organized as follows. We first briefly present the results from Casse et al. (2025) that quantified the effect of the secondary disruptor upon the disk surrounding the primary black hole and show on which timescales they occur. In the following sections, we present the observational consequences of these three effects and assess their potential for identifying early BBH systems with preexisting disk(s). Section 5 discusses a necessary observable of these systems and the information that could be learned from this detection. In particular, we focus on the outer disk detection in NGC 4395, which calls for further investigation. In the last section, we briefly explore the effect of the presence of early BBH components, namely the two potential preexisting disks and CBD, on the observables.

2. Imprint of a secondary black hole on the circumprimary disk

For the remainder of the paper, we focus on BBH systems with a large separation, that is, larger than 103rg1 (see the definition of the gravitational radius of the most massive black hole of the BBH system rg1 in Fig. 1). We deemed these separations large in comparison with the typical size of accretion disks in active galactic nucleus (AGN), whose outer radii do not tend to be larger than a few thousand gravitational radii (Jha et al. 2022).

|

Fig. 1. Schematic view of the main stages of a binary black hole system. The black hole masses are denoted by M1 and M2 with their initial separation D12 ≫ 103rg1 where rg1 = GM1/c2 is the gravitational radius of the most massive black hole of the BBH (G is the gravitational constant and c the speed of light in vacuum). |

We defined the early stage as the transitional period before a circumbinary disk is fully formed and interacts with the binary. In early BBH systems, we expect a large cavity of about twice the separation (Artymowicz & Lubow 1994) that allows the survival of a part of any preexisting disks around each of the black holes. Fig. 1 presents a schematic view of the evolution of two black holes with their preexisting disks, starting from their pre-binary state to the early BBH stage in which we are interested, and finally, to the near-merger stage, the most frequently studied phase of BBH where black holes rapidly inspiral toward each other while they are embedded in a CBD.

In this early BBH stage, each black hole keeps its preexisting disk, if it had any, as they inspiral. To determine the fate of these original disks, in particular, how long they remain stable and whether they have any distinguishable features, we used the results from previously published hydrodynamical numerical simulations of the accretion disk surrounding the most massive black hole of the binary and taking into account the gravitational influences of the two black holes upon that disk. Casse et al. (2025) provided analytical fits of the outer disk extension as well as its eccentricity for a wide range of black hole mass ratios and separations. This enabled us to assess the extension and eccentricity of the two preexisting disks, if they exist, in an early BBH system. As an illustration, the two preexisting disks shown in the early BBH stage in Fig. 1 originated from snapshots of hydrodynamical simulations from Casse et al. (2025) and show the overall disk structure under the effect of the two black holes.

2.1. 2D fluid simulations of the early phase

In Casse et al. (2025) we explored through numerical simulation how would the pre-existing disk around a black hole be affected by a coplanar secondary black hole in a bound circular orbit with a period of

with rg1 the gravitational radius, and M1 the mass of the primary black hole on which the simulation is centered, D12 the distance between the two black holes, and q = M2/M1 the black hole mass ratio. We here only considered the case when the secondary object is less massive than the primary, that is, q ≤ 1.

As we searched for the effect on the outer edge of the disk, the fluid simulations were made in the frame associated with the primary black hole, where its gravity was modeled using a pseudo-Newtonian potential (see Eq. (6) in Casse et al. 2025), while the gravitational force of the remote secondary black hole was included using a classical Newton law. We performed the ray-tracing of those fluid simulations in a fully general relativistic framework because this was shown to be sufficient for producing reliable synthetic observations of the disk far from the black hole (Casse et al. 2017). This choice prevented us from assessing the effect of the secondary black hole and the spin of the primary black hole on the inner region of the primary disk, but it enabled us to consider the dynamics of the outer disk over a large number of periods of the binary system. These approximations will be relaxed in a forthcoming paper that will be fully devoted to the inner region of the primary’s disk whose observables will likely be detectable in much higher-energy bands than the effects presented here. Similarly, we kept the secondary black hole on a circular orbit in the same plane as the primary’s disk in order to study the minimum possible effect. Indeed, we did not take the potential warping of the outer edge into account, which would amplify several of the effects we present here.

2.2. Features of a circumprimary disk in an early binary black hole system

In the simulations reported by Casse et al. (2025), we found that the resulting outer edge of the disk is affected by the secondary and takes a typical shape, as shown in the middle panel of Fig. 1. This led us to three qualitative effects that are strongly linked with the presence and parameters of the secondary disruptor.

-

First, we showed in Casse et al. (2025) (see, e.g., their Fig. 2) that not only does a secondary disruptor shave off the outer edge of the preexisting circumprimary disk, but the position of the outer edge was linked with the mass and position of this secondary object through a relation that is well fit for mass ratios of 10−3 ≤ q ≤ 1 by rout = f(q) D12, where f(q)2 is a decreasing function of the mass ratio q. While this is not the only mechanism that can truncate an outer disk, a secondary object that lies close enough always shaves the outer disk off.

-

Second, after circularization of the binary, the resulting smaller disk is not axisymmetrical, but shows an elliptical distortion that follows the secondary disruptor. We showed in Fig. 7 of Casse et al. (2025) that this eccentricity is quite high, at e ≃ 0.6, for a secondary in circular orbit with a mass ratio above q = 2 × 10−2, and it decreases for a lower mass ratio.

-

Last, an m = 2 spiral is present throughout most of the simulation, but its amplitude is small, which makes it hard to see in the last few frames in Fig. 2 from Casse et al. (2025).

While these three effects have different amplitudes and timescales, they are all related to the orbital parameters of the secondary, and, if detectable, they might lead to the identification of systems in the early BBH stage.

The simulations presented by Casse et al. (2025) only considered the preexisting disk around the most massive black hole of the system. Nevertheless, by symmetry, the same results apply to the preexisting disk of the second black hole, if it exists.

2.3. Ray-tracing with Gyoto

In order to explore the observational consequences of the three aforementioned effects, we first computed the spectral energy distribution (SED) of the resulting truncated disk. We did this with the general relativistic (GR) ray-tracing code gyoto (Vincent et al. 2011), which we previously used in conjunction with the same pseudo-Newtonian hydrodynamical code as in Casse et al. (2025). Casse et al. (2017) showed that it is not necessary to use fully GR fluid dynamics to study the disk far away from a black hole, but GR ray-tracing is still needed in order to fully capture what a distant observer would see. Because the fluid simulation was made in the Paczynsky & Wiita pseudo-Newtonian approximation (Paczynsky & Wiita 1980), and therefore without spin for the black hole, we computed the null geodesic in the Schwarzschild metric.

We are interested in the thermal emission of the truncated preexisting circumprimary disk which lead us to use the already implemented blackbody disk emission module from gyoto in conjunction with the disk characteristics found in the fluid simulations. This reproduced a simple α-disk model (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973) with a power-law temperature distribution

with ṀE the Eddington accretion rate. This is also fully compatible with the diskbb3 model that is often used to fit observational data.

3. Evolution of the spectral energy distribution of one black hole and its preexisting disk

The first and strongest effect we saw in the simulations is the truncation of the circumprimary outer disk, linked with the position of the secondary black hole along the inspiral motion of the binary system4. It is therefore interesting to assess the observational consequences of a shrinking outer edge of the preexisting circumprimary disk during the early merger stage. This is especially interesting because the outer edge of the circumprimary disk is directly linked with the binary parameters and the time to merger2.

3.1. Spectral energy distribution of a truncated disk

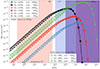

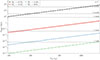

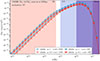

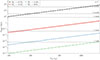

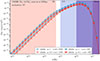

Using the results of the hydrodynamic simulations presented in Casse et al. (2025), we produced synthetic observations using gyoto in order to explore the effect of the missing outer disk on the overall spectral energy distribution (SED) of the preexisting circumprimary disk, assuming standard thermal emission for the disk (see Sect. 2.3 for details). These computations are also useful for identifying the most auspicious energy band in the multicolor blackbody spectrum for a detection in the early phase. In order to determine these energy bands, Fig. 2 shows the changes in the SED as the outer disk is shaved off for a range of primary masses between 103 M⊙ and 4 × 107 M⊙ located at a distance of 90 Mpc, as well as for a lower mass of 40 M⊙ at 10 kpc. As expected, when some of the outer disk is removed, the overall SED decreases at lower frequencies. The exact energy at which the emission starts to drop depends on the temperature of the missing outer disk, which depends on the mass of the central object. For supermassive BBHs with masses above 106 M⊙, the changes are mostly visible in the infrared, while primary black holes with masses lower than 106 M⊙ exhibit an SED modification that starts at the lower end of the UV band. This contrasts with the late phase of the merger, in which a circumbinary disk is present and in which most of the changes in the SED are predicted at a higher energy (Roedig et al. 2014; Farris et al. 2015; Tang et al. 2018; D’Ascoli et al. 2018; Gutiérrez et al. 2022; D’Orazio & Charisi 2023; Krauth et al. 2024; Cocchiararo et al. 2024; Franchini et al. 2024).

|

Fig. 2. Evolution of the SED as the outer edge of the preexisting disk is sculpted away for different masses of supermassive BBHs and radius evolution in the equal-mass case. All the supermassive sources are located at 90.3 Mpc, and the 40 M⊙ is at 10 kpc. They are all observed at an inclination of 70° to be easily compared. |

3.2. Constraint from the time to merger

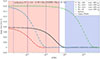

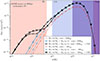

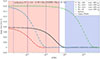

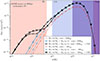

While the changes from the removal of the outer disk shown in Fig. 2 appear to be significant enough to be detectable, the timescale on which the outer radius changes needs to be considered. This process occurs on the same timescale as the inspiral of the binary, which depends on the mass of the binary. In order to identify which BBH system might exhibit an observable SED alteration, we used the results from Casse et al. (2025) to link the time to merger to the position of the outer radius of the circumprimary disk. In Casse et al. (2025), we considered early BBH systems whose separations were up to a few thousand BBH gravitational radii, which is consistent with an inspiral motion that is dominated by gravitational wave emission. We aimed to determine the system that might be followed through the alteration of its SED, so Fig. 3 shows around 100 years5 prior to the merger and displays the probable outer radius of the preexisting circumprimary disk for a selection of equal-mass systems with a black hole primary mass ranging from 40 to 107 M⊙. In this plot the vertical dashed lines represent the outer disk radius for the system used as examples in Fig. 2 while the horizontal lines show the 100 years and 50 years time to merger. These arbitrary time limits are on the same order of magnitude as historical data and stand as a time limit for our ability to detect the movement of the outer edge of the circumprimary disk. We also represented the 10-year time limit, which corresponds to the more recent data.

|

Fig. 3. Evolution track linking the outer edge of the preexisting primary’s disk and the time to merger for several equal-mass cases from low-mass systems to the lower end of supermassive systems. |

Fig. 3 shows that the higher-mass systems with primary masses higher than 106 M⊙ are already expected to have a very truncated original disk 100 years prior to their merger, and they probably already have a CBD. All of this would change the SED of the full system (see Sect. 6). It seems quite unlikely that we will be able to observe any significant evolution of the outer disk of these systems. This is especially the case because the older observations would not have the same precision as more recent infrared data, but we would also need to add the typical stochastic noise of AGN. Moreover, it is worth noting that for these higher-mass systems, the black hole separation is close to the lower limit we can explore with our simulations, and some other effects, linked to the formation of a circumbinary accretion structure, for example, might lead to a different set of observables that were not studied in Casse et al. (2025) and are therefore not present in the SEDs we computed here. Similarly, when the supermassive binary black hole separation is larger than shown in Fig. 3, the change of the outer edge of the disk over 100 years is negligible and will therefore not lead to any detection.

On the other side of the mass spectrum, stellar mass BBH change strongly enough on a timescale of about 50 years. This might be searched for in historical data, especially because the orbit shrinks faster (and the outer disk is removed faster) closer to the merger, and some effect might even be detectable within the last 10 years of astrophysical data. A blind search through the optical and infrared data archives like this might be automated. Even though a low-mass BBH system with enough gas is not likely, there is much to gain from the detection of the shaving of the outer disk in these systems.

Similarly, intermediate-mass systems would also be a good target for these blind searches through the archive. Although they evolve more slowly than stellar mass systems, they are still expected to show a significant variation of the outer edge of the circumprimary disk over 100 years. As an example, a 2 × 103 M⊙ BBH system evolves from rout ≃ 800 rg1 to its merger over 100 years, which could lead to a potentially detectable change in the spectrum. These systems might still have their preexisting disk or might have disks that formed through increased tidal disruption events as the binary separation decreases.

As a conclusion and even though the shrinking outer edge of the disks in BBH system is expected to be a universal trend in the early phase, it appears difficult to follow its evolution for the most massive systems because of the timescale involved in this process. The only systems for which this timescale makes their detection conceivable are systems with potentially little gas, such as a stellar mass binary black hole, or systems involving the elusive intermediate-mass black holes.

4. Effect at the BBH orbital timescale on the SED of the primary black hole

The timescale on which the orbit shrinks is too long to be detected early on for supermassive BBH systems. We therefore investigated phenomena that occur on a timescale related to the secondary orbital period (see Eq. (1)). While this is still a multi-year timescale for the widest separations and highest masses (see Fig. 4), it is much shorter than the merger timescale, so that related phenomena might be tracked with carefully planned observations. Moreover, the secondary orbital period is of the order of tens of days for a 107 M⊙ BBH system at a separation below a few hundred rg1 or below 4 × 103rg1 for a 105 M⊙ system. Thus, the associated periodic patterns might be detectable for a wide range of binary parameters.

|

Fig. 4. Evolution of the secondary black hole orbital period as function of the binary separation for an equal-mass binary. |

4.1. Effect of the presence of the spiral arms

Spiral arms are present in a wide variety of systems with different origins, such as disk instabilities (Varniere et al. 2011) or a gravitational disruptor, regardless of whether they are bound to the system (Quillen et al. 2005). They therefore cannot be used as a final diagnostic of the existence of a binary system. Nevertheless, they are present in case of a binary and might be used to identify stronger BBH candidates among systems for which a binary is suspected.

Spiral arms can be primarly searched for in two ways, depending on how strong these arms are and how large the system is. The most common way to search for a strong spiral structure is through its effect on the light curve because spiral arms create a modulation in the flux (Varniere & Vincent 2016). This detection method cannot be used here because the spiral arms are very faint and do not lead to a detectable level of modulation even for high-inclination systems.

The second method is through direct detection of the spiral arm, which works well for a massive companion, regardless of whether it is bound to the system, as was shown by Quillen et al. (2005). Even more recently, spiral arms caused by a companion were confirmed in a young stellar object (Xie et al. 2023). This method requires a large enough system because the outer disk must be observed directly, but it also requires that the system is suspected of being a binary system because a long-term observation campaign is needed to follow at least part of the secondary orbital motion. These two reasons mean that it is unlikely that we will be able to detect this effect for most early BBHs because the system needs to be a BBH candidate and also in a stage with favorable parameters.

The direct effect of the spiral arms alone, therefore, does not appear to be a good diagnostic for the early-merger BBH. Another option that we did not explore here is to search for the effect of this spiral on the reflection spectrum, in particular, on the iron line profile. Karas et al. (2001) showed that the nonaxisymmetry of a spiral might lead to detectable features for a future X-ray mission. This might be worth exploring, in particular, for systems with a high signal-to-noise ratio because the spiral arms shown in our simulations would lead to small and narrow features.

4.2. A closer look at the effect of the ellipse precession

The second effect that occurs on the orbital timescale of the secondary disruptor is the precession of the elliptical outer edge of the disk once the binary is circularized. This is especially interesting because the eccentricity of the outer disk induced by a second black hole in a circular orbit can reach e ∼ 0.6 for q > 10−2, as shown in Fig. 7 in Casse et al. (2025), and any nonaxisymmetry in the system is amplified by the GR boost as photons pass close to the black hole. Therefore, even with the low density of the elliptical part of the disk shown in Fig. 1, the level of the resulting modulation of the light curve is worth determining. Indeed, the change will follow the orbit of the second black hole, and it will thus create a periodic change in the shape of the energy spectrum that might help us determine the parameters of the secondary object.

Because the change in the SED is over several orders of magnitude in frequency and flux, it is easier to plot the contrast between the high and low phases of the modulation rather than the overall energy spectrum. As a result, Fig. 5 shows the maximum effect of the precession of the outer disk on the shape of the energy spectrum. As expected, the effect is small, with an amplitude lower than 1% along the orbit of the secondary for an outer radius of the disk at 200 rg1. The amplitude of the effect increases with the shrinking outer edge, which means that the effect will be easier to detect as the system approaches the merger.

|

Fig. 5. Relative difference between the preexisting circumprimary disk energy spectrum associated with the two extreme positions of its elliptical outer edge with respect to the observer for various BBH masses. |

For supermassive BBHs, the changes are mostly expected in the infrared, and only the lower masses exhibit changes in the visible spectrum. Stellar mass BBHs are more interesting because a wide energy range is affected, from the very soft X-ray band to the far-infrared. The James Webb telescope will be able to reach many systems from stellar masses to supermassive systems.

Because the effect has a low amplitude, it will be difficult to use this variability in the shape of the energy spectrum as a diagnostic for the presence of an early binary system. Nevertheless, because the effect grows stronger as the merger approaches, it can be used as an additional test for BBH candidates, especially as other phenomena, such as those that generate spiral arms, will modulate the disk emission at the same frequency and hence increase the overall level of the detectable modulation. In particular, when we focus on binary systems with orbital periods of up to a few tens of days, we might have access to observations that cover many binary orbits. This would in turn allow us to fold its light curve to determine if such frequency is present with an improved signal-to-noise ratio. We might also search for this periodicity with future wide-field or full-scan telescopes, such as the Roman telescope.

5. The necessary observable of the missing outer disk

When we search for a way to identify early BBHs, the first thought is to search for the changes in the emission of the preexisting disk of each black hole related to the inspiral of the binary. This leads to several problems related to the long timescale on which one outer preexisting disk varies and to the small effects related to the faster binary period6. While none of the effects presented here can be used as an unequivocal signature of a binary system, the outer disk truncation represents a necessary observable that might refute potential BBH candidate sources with individual accretion disk(s), and it should be added as a test performed on all BBH candidates to determine whether their outer disk is indeed coherent with the inferred system size, mass ratio, and time to merger.

5.1. A new way to search for early BBH candidates

5.1.1. General procedure

In the quest for BBH systems, the next step might be to explore all systems with a smaller outer disk edge than average in order to determine the implications for the system as an early BBH and to possibly trigger a search for other diagnostics.

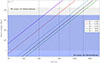

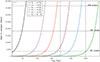

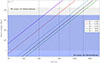

When we know the position of the outer edge of the circumprimary disk, we can invert the relation between rout and the binary parameters to determine all the mass ratios and binary separations that agree with the reduced size of the disk. Fig. 6 illustrates the binary parameter range, (q, D12), that corresponds to four virtual observationally inferred outer edge radii (rout = 300, 500, 103, 1.7 × 103rg1). As an example, we show in Fig. 6 a shaded area that encompasses the separation parameter range corresponding to a circumprimary disk with an outer edge where rout = 1.7 × 103rg1. According to our results, the secondary black hole for this case would be located at a distance between about 3 × 103 and 5.5 × 103rg1, depending on the mass ratio of the BBH system. While the mass of the secondary black hole is impossible to constrain in this way, its separation from the primary is limited to approximately two to three times the outer edge of the disk.

|

Fig. 6. Possible parameter space for the secondary disruptor for a given outer edge rout. We show the line along which the secondary should lie for rout = (300, 500, 103, 1.7 × 103) rg1. Without prior knowledge of either the separation or the mass ratio, we obtain the shaded rectangle as the potential zone for the secondary at the origin of the shrinking of the outer edge. |

With the location of the potential secondary black hole, we can start to search for it through its effect on the circumprimary disk with a particular emphasis on variability because the BBH timescale, PBBH (see Eq. (1)), strongly depends on the mass and separation of the binary system. This variability, together with a reduced AGN disk, suggests a secondary object whose mass might be estimated through the value of the variability period. Even the nondetection of this variability might place additional limits on the allowed parameter space for the potential binary, which in turn might either reject this possibility as a source of the truncation or help find a potential candidate.

5.1.2. The case of NGC 4395

Recently, McHardy et al. (2023) presented the ‘first detection of the outer edge of an AGN accretion disk’ in the low-mass AGN NGC 4395. Based on results from HiPERCAM, the best reprocessing model gave a truncated disk with an outer edge of about 1.7 × 103rg with an error of ∼100 rg. While there is no indication of a secondary disruptor near NGC 4395, the detection of an outer edge for an AGN shows that it will be possible in the future to test supermassive BBH candidates similarly. We therefore explored the possible binary parameters if this outer edge was indeed caused by a secondary disruptor. The shaded area in Fig. 6 shows the parameter space of a secondary that would lead to a 1.7 × 103rg1 truncation for the circumprimary disk, namely a binary separation between ∼3000 − 6000rg1 for a wide range of mass ratios. While this possibility was not explored in their original paper, it would be interesting to determine whether any object is located at these distances, or if an indication of the orbital frequency can be detected in the observables. This is especially interesting because NGC 4395 is a low-mass AGN, and the orbital frequency of the secondary is therefore a few days7 at most, which is detectable.

5.2. From the elusive intermediate-mass to the stellar mass black hole binaries

While even 10 years ago we were only hoping to detect gravitational waves from binary black hole merger, gravitational waves have now become one of the best messengers with which to study black hole systems. We still lack electromagnetic pre-merger BBH detections, in part because the timescale between detection and merger of the running gravitational wave observatory is too short to catch the source before merger.

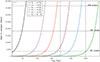

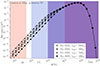

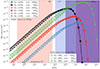

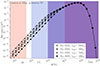

We therefore need another trigger to find these pre-merger sources with enough time for a multiwavelength follow-up. It is therefore interesting to determine the emission of early pre-merger intermediate-mass black hole binaries even though these systems do not have a firm detection yet. Although they might not have enough gas to render the black hole ‘identifiable’ as such, it might be enough to trigger a search for a smaller than average disk. We also expect strong changes in the SED from the UV to infrared (see Fig. 2) following the fast evolution of the outer edge of the circumprimary disk for intermediate-mass binary black holes, and lower, as shown in Fig. 7. These changes are an interesting criterion for a blind automated search through the optical and infrared archival data, and a positive results would give us access to a wealth of data with observations spanning 10–50 years before the merger.

|

Fig. 7. Evolution of the time to merger as function of rout of the circumprimary disk for low equal-mass binary black holes. The shaded area represents 10 years of observations prior to merger, and the hatched area represents 50 years to merger (minus one day for visual clarity). |

The effect of a secondary black hole on the SED is even more striking in systems with the lowest mass if there is enough gas in the system for at least one of the black holes to have a disk8. Fig. 8 shows the overall expected change in the SED of a 40 M⊙ primary black hole over about 50 years prior to merger (crosses versus star), as well as some intermediary times (diamond at ∼3.5 years and inverted triangle ∼6 months to merger). While a cross correlation with older observations might be difficult, especially for sources at a great distance, the effect accelerates closer to the merger, and the difference between the diamonds and the stars is less than 4 years, which is well within the lifetime of one instrument. This again depends on whether one of the black holes at least has a disk, and while this is not likely, even one detection would give us much information about pre-merger systems.

|

Fig. 8. Effect of the decreasing rout on the energy spectrum of the circumprimary disk in a system with a primary black hole of 40 M⊙. The time at which the spectra are shown is represented in Fig. 7 as the perpendicular line that spans more than 50 years. |

A search for these systems might also be conducted in preparation for the LISA mission, which will be able to detect the gravitational emission for the lower mass BBHs a few months before the merger (Mangiagli et al. 2020, 2022). Because of the large localization box, having already identified potential BBH candidates would help us to ensure the best pre-merger electromagnetic follow-up if any gas is present in the system.

6. Effect on the observables of the full binary system

We have so far considered the effect of the different phenomena presented in Sect. 2.2 on the observables of a system comprised of one black hole and its preexisting disk. While this might represent a very early case in which the angular separation between the two black holes might allow for separate observations, we presented this mostly to show the individual effects. We study the more general case below, when we are unable to separate the components of the binary system.

6.1. Effect of the secondary black hole on the observation

We now consider a secondary black hole with a preexisting disk, but still no detectable circumbinary disk, either because it is not yet fully formed or it is too faint. All the results from Casse et al. (2025) summarized in Sect. 2.2 as well as the results presented above are also valid for the disk of the secondary black hole. The two outer edges will be shrunken as the binary inspirals closer together, and their SED will exhibit a similar decrease in the lower-energy band.

In order to show this effect and facilitate comparison with the previous plot, we chose to keep the mass of the primary black hole at 4 × 107 M⊙, as in Fig. 2, and also at the same rout for the primary black hole. Fig. 9 shows the evolution of the SED for two binary black hole systems, the ‘extreme’ case of an equal-mass case, and a lower mass ratio of q = 0.1. The equal-mass case is easy because each black hole and its preexisting disk are interchangeable. The flux is therefore twice the same. For the other mass ratio, we first used the relation reported by Casse et al. (2025) between rout, 1, q, and D122 to obtain the separation between the two black holes, which we then translated into units of the gravitational radius of the secondary black hole rg2 = GM2/c2 = qrg1. Based on this, we computed the position of the disk truncation of the secondary black hole. For simplicity, we assumed that the disk of the secondary was in a similar state, with a mass-scaled temperature from the α-disk model (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973) and following Eq. (2).

|

Fig. 9. Evolution of the SED when the two black holes and their eroded preexisting disks are visible in the same observation for two mass ratios q = 1 and q = 0.1. |

As expected, Fig. 9 shows that even when we cannot isolate one of the black holes, we will still be able to see the drop in the lower energy band of the SED, and it will even be greater than the drop in Fig. 2 in the equal-mass case. The q = 1 SED from Fig. 9 is the ‘best-case scenario’ for the detectability, when the two effects add up at every energy, while Fig. 2 represents the worst-case scenario, in which the secondary disk does not contribute significantly to the SED.

6.2. Effect of the CBD on the observation

While we focused on the search for observable signatures of BBHs having no, or at least not detectable, CBD, we add for completion the change induced by a CBD on the SED presented above for two black holes and their disks. First, the shrinking is only related to the gravitational impact of the secondary and would therefore still exist when the binary is surrounded by a CBD, but the emission from the CBD would need to be taken into account.

To facilitate comparison, we again chose an equal-mass binary with the primary black hole at 4 × 107 M⊙, and we also kept the same evolution in rout as in the previous figures. For simplicity, we chose the CBD to be in a similar state as the previous disks, but orbiting the center of mass of the binary at twice the binary separation. We also used the same mass-scaled α-disk model (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973), but for the total binary mass (see Eq. (2)). Depending on how much material was available in the environment around the two black holes and disks, this simple approach might be an over- or underestimation of the density in the CBD in the early BBH stage, but it gives an order of magnitude for the SED.

Nevertheless, Fig. 10 shows that we recovered the ‘notch’ that is often presented as the diagnostic of the configuration of two inner disks and a CBD with a cavity in between. We also detect, as a consequence of the inspiral and the shrinking of the outer edge of the two black hole disks, that

|

Fig. 10. Spectral energy distribution for an equal-mass black hole with an original eroded disk and a detectable CBD. |

While the effect of the shrinking outer disk is detectable in a more limited energy range because of the CBD, it also gives us a stronger observable of inspiraling BBHs when it is associated with this moving ‘notch’. The two movements of the inner edge of the CBD and the outer edge of each black hole disks are on the same timescale, and all the considerations from the previous section are therefore still valid when both effects are taken into account.

7. Conclusions

With the first detection of gravitational waves from a compact object merger, the hunt for pre-merger BBHs received much attention from the community because their existence was finally confirmed observationally. In order to detect these systems, we must first characterize their observables, and we must in particular assess their unicity. The most promising observable found so far, that might help us to identify near-merger BBHs is only linked to the variability of their circumbinary disk. We studied earlier systems, which allowed us to present a complementary observable linked this time with the preexisting black hole disk and the effect on them of the two black holes.

In a companion paper, Casse et al. (2025), we used numerical simulations to explore the effect of a gravitationally bound secondary black hole on the original accretion disk surrounding the primary black hole. We not only confirmed the presence, but also quantified three qualitative effects that occur on two different timescales, and all of them are strongly linked with the characteristics of the secondary black hole.

Based on these previous results, we computed synthetic observations of early BBH systems. We studied the consequences of these effects on the thermal emission of a preexisting circumprimary disk and determined whether it might lead to early BBH detections. We found that the spiral wave in the circumprimary disk and the eccentricity of its outer edge (both occurring on the orbital timescale of the secondary black hole) have too weak of an effect to be significant signatures of an early BBH. Nevertheless, these two effects will increase closer to the merger, and they might eventually become detectable, or, they might, by their absence, provide a way to estimate an upper-limit of the time-to-merger of a system.

More interestingly, we found a necessary observable for an early (wide binary with a separation greater than 103rg1) BBH with a preexisting disk(s). A near equal-mass companion (q ≥ 10−3, Casse et al. 2025) will slowly shave the preexisting circumprimary outer disk as they approach one another, and this means that the missing outer disk is a strong signature of an early BBH system. While this phenomenon is not unique to gravitationally bound systems, as the flyby of another massive object would create a similar though transitory effect, it will nevertheless exist in a binary system. It should therefore be used when possible as a test of the presence of a binary for all early BBH candidates to search for any incoherence between the inferred system parameters and the expected disk size.

When the binary reached a stage in which the emission from the circumbinary disk is detectable while the separation is also wide enough for each black hole to still have their preexisting disk, it becomes more interesting to focus the search for these systems on the changes in the SED around the ‘notch’ area. Indeed, not only the effect of the shrinking outer disk is still detectable, if in a narrower energy band, but the ‘notch’ will also be moving toward higher energies as the binary inspirals.

While it is hard to determine the radial extent of an AGN disk, it could be used to flag early BBH candidates among supermassive black hole systems, making it an interesting goal. This is especially true if a method could be automated to search through archival data for ‘smaller’ than average or receding disks in order to flag potential early BBH candidates, which might then be independently targeted to prepare for a future GW mission such as LISA.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, PV, upon request and will also be part of a data release in mid 20269.

Acknowledgments

The numerical simulations we have presented in this paper were produced on the DANTE platform (APC, France) and on the high-performance computing resources from GENCI – IDRIS (grants A0150412463 and A0170412463). Part of this study was supported by the LabEx UnivEarthS, ANR-10-LABX-0023 and ANR-18-IDEX-0001.

References

- Artymowicz, P., & Lubow, S. H. 1994, ApJ, 421, 651 [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J., & Zhu, Z. 2018, ApJ, 859, 118 [Google Scholar]

- Casse, F., Varniere, P., & Meliani, Z. 2017, MNRAS, 464, 3704 [Google Scholar]

- Casse, F., Varniere, P., Arthur, L., & Dodu, F. 2025, A&A, 698, A59 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cocchiararo, F., Franchini, A., Lupi, A., & Sesana, A. 2024, A&A, 691, A250 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ascoli, S., Noble, S. C., Bowen, D. B., et al. 2018, ApJ, 865, 140 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- D’Orazio, D. J., & Charisi, M. 2023, Observational Signatures of Supermassive Black Hole Binaries [Google Scholar]

- D’Orazio, D. J., Haiman, Z., & MacFadyen, A. 2013, MNRAS, 436, 2997 [Google Scholar]

- Eggleton, P. P. 1983, ApJ, 268, 368 [Google Scholar]

- Farris, B. D., Duffell, P., MacFadyen, A. I., & Haiman, Z. 2014, ApJ, 783, 134 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Farris, B. D., Duffell, P., MacFadyen, A. I., & Haiman, Z. 2015, MNRAS, 446, L36 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Franchini, A., Bonetti, M., Lupi, A., & Sesana, A. 2024, A&A, 686, A288 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Godon, P., Livio, M., & Lubow, S. 1998, MNRAS, 295, L11 [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, E. M., Combi, L., Noble, S. C., et al. 2022, ApJ, 928, 137 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jha, V. K., Joshi, R., Chand, H., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 511, 3005 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ju, W., Stone, J. M., & Zhu, Z. 2016, ApJ, 823, 81 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Karas, V., Martocchia, A., & Subr, L. 2001, PASJ, 53, 189 [Google Scholar]

- Krauth, L. M., Davelaar, J., Haiman, Z., et al. 2024, Phys. Rev. D, 109, 103014 [Google Scholar]

- Lubow, S. H. 1994, ApJ, 432, 224 [Google Scholar]

- Mangiagli, A., Klein, A., Bonetti, M., et al. 2020, PRD, 102, 084056 [Google Scholar]

- Mangiagli, A., Caprini, C., Volonteri, M., et al. 2022, Phys. Rev. D, 106, 103017 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R. G., & Lubow, S. H. 2011, MNRAS, 413, 1447 [Google Scholar]

- McHardy, I. M., Beard, M., Breedt, E., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 519, 3366 [Google Scholar]

- Mignon-Risse, R., Varniere, P., & Casse, F. 2025, A&A, 704, A299 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, R., & Lai, D. 2015, MNRAS, 452, 2396 [Google Scholar]

- Noble, S. C., Mundim, B. C., Nakano, H., et al. 2012, ApJ, 755, 51 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Noble, S. C., Krolik, J. H., Campanelli, M., et al. 2021, ApJ, 922, 175 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paczynski, B. 1977, ApJ, 216, 822 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paczynsky, B., & Wiita, P. J. 1980, A&A, 88, 23 [Google Scholar]

- Papaloizou, J., & Pringle, J. E. 1977, MNRAS, 181, 441 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo, B., Sparke, L. S., & Aguilar, L. A. 2005, MNRAS, 359, 521 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quillen, A. C., Varnière, P., Minchev, I., & Frank, A. 2005, AJ, 129, 2481 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rafikov, R. R. 2016, ApJ, 831, 122 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Roedig, C., Krolik, J. H., & Miller, M. C. 2014, ApJ, 785, 115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sawada, K., Matsuda, T., & Hachisu, I. 1986, MNRAS, 221, 679 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shakura, N. I., & Sunyaev, R. A. 1973, A&A, 24, 337 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.-M., Krolik, J. H., Lubow, S. H., & Hawley, J. F. 2012, ApJ, 749, 118 [Google Scholar]

- Spruit, H. C. 1987, A&A, 184, 173 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y., Haiman, Z., & MacFadyen, A. 2018, MNRAS, 476, 2249 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Varniere, P., & Vincent, F. H. 2016, A&A, 591, A36 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Varniere, P., Tagger, M., & Rodriguez, J. 2011, A&A, 525, A87 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Varniere, P., Mignon-Risse, R., & Casse, F. 2025, MNRAS, 538, 1055 [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, F. H., Paumard, T., Gourgoulhon, E., & Perrin, G. 2011, CQG, 28, 225011 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Westernacher-Schneider, J. R., Zrake, J., MacFadyen, A., & Haiman, Z. 2024, ApJ, 962, 76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehurst, R., & King, A. 1991, MNRAS, 249, 25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C., Ren, B. B., Dong, R., et al. 2023, A&A, 675, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z., Ju, W., & Stone, J. M. 2016, ApJ, 832, 193 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

See Mignon-Risse et al. (2025), Varniere et al. (2025) for observables related to the near merger stage when the BBH is embedded in a circumbinary disk.

By symmetry, any preexisting disk around the secondary is truncated by the primary, following the same principle (see Sect. 2.2).

As a side note, the variability related to the potential CBD would be on a longer timescale than the binary period because the edge of the CBD is about twice the binary separation (see for example Noble et al. 2012).

Which will be available for download at https://apc.u-paris.fr/~pvarni/eNOVAs/LCspec.html

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Schematic view of the main stages of a binary black hole system. The black hole masses are denoted by M1 and M2 with their initial separation D12 ≫ 103rg1 where rg1 = GM1/c2 is the gravitational radius of the most massive black hole of the BBH (G is the gravitational constant and c the speed of light in vacuum). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Evolution of the SED as the outer edge of the preexisting disk is sculpted away for different masses of supermassive BBHs and radius evolution in the equal-mass case. All the supermassive sources are located at 90.3 Mpc, and the 40 M⊙ is at 10 kpc. They are all observed at an inclination of 70° to be easily compared. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Evolution track linking the outer edge of the preexisting primary’s disk and the time to merger for several equal-mass cases from low-mass systems to the lower end of supermassive systems. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Evolution of the secondary black hole orbital period as function of the binary separation for an equal-mass binary. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Relative difference between the preexisting circumprimary disk energy spectrum associated with the two extreme positions of its elliptical outer edge with respect to the observer for various BBH masses. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Possible parameter space for the secondary disruptor for a given outer edge rout. We show the line along which the secondary should lie for rout = (300, 500, 103, 1.7 × 103) rg1. Without prior knowledge of either the separation or the mass ratio, we obtain the shaded rectangle as the potential zone for the secondary at the origin of the shrinking of the outer edge. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Evolution of the time to merger as function of rout of the circumprimary disk for low equal-mass binary black holes. The shaded area represents 10 years of observations prior to merger, and the hatched area represents 50 years to merger (minus one day for visual clarity). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Effect of the decreasing rout on the energy spectrum of the circumprimary disk in a system with a primary black hole of 40 M⊙. The time at which the spectra are shown is represented in Fig. 7 as the perpendicular line that spans more than 50 years. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9. Evolution of the SED when the two black holes and their eroded preexisting disks are visible in the same observation for two mass ratios q = 1 and q = 0.1. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10. Spectral energy distribution for an equal-mass black hole with an original eroded disk and a detectable CBD. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.