| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A187 | |

| Number of page(s) | 13 | |

| Section | Atomic, molecular, and nuclear data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556913 | |

| Published online | 12 February 2026 | |

Fine and hyperfine (de-)excitation of C4H (X2Σ+) by collisions with He at low temperatures

1

Institute of Physics, Faculty of Physics, Astronomy and Informatics, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń,

Grudziadz Street 5,

87-100

Toruń,

Poland

2

Faculty of Chemistry, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń,

ul. Gagarina 7,

87-100

Toruń,

Poland

3

Université de Tunis, Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Ingénieurs de Tunis, Laboratoire de Spectroscopie et Dynamique Moléculaire (LSDM),

5 Av. Taha Hussein,

1008

Tunis,

Tunisia

4

Université Gustave Eiffel, COSYS/IMSE,

5 Bd Descartes,

77454

Champs sur Marne,

France

★ Corresponding authors: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

19

August

2025

Accepted:

9

December

2025

We present a quantum scattering study of the fine and hyperfine rotational (de-)excitation of the linear carbon-chain radical C4H (X2Σ+) in collisions with helium atoms at low temperatures relevant to the interstellar medium (ISM). For those purposes, a new highly accurate two-dimensional potential energy surface (2D-PES) for the C4H–He weakly bound complex was generated using the spin-restricted explicitly correlated coupled-cluster RCCSD(T)-F12 approach in conjunction with the aug-cc-pVTZ basis sets and full counterpoise corrections. The resulting 2D-PES exhibits pronounced anisotropy, featuring a global minimum at a T-shaped configuration and a secondary local minimum at linear geometry. Such anisotropy significantly affects the collisional dynamics. Based on this 2D-PES, we performed quantum close-coupling scattering calculations followed by angular momentum recoupling techniques to obtain state-to-state inelastic cross sections and temperature-dependent rate coefficients for transitions between the fine and hyperfine structure levels of C4H radical. Our computations reveal a marked preference for Δj = ΔN = ±2 fine-structure transitions, governed by the dominant second-order anisotropic term in the Legendre expansion of the interaction potential. Additionally, hyperfine-resolved rate coefficients display enhanced probabilities for transitions with ΔF = Δj, particularly at high rotational levels. This study provides the first set of fine- and hyperfine-resolved rate coefficients for the C4H–He system, offering essential input for non-local thermodynamic equilibrium modeling of C4H absorption and emission in cold astrophysical environments. Indeed, the present set of data should enable more accurate interpretations of observational spectra from cold molecular clouds and circumstellar envelopes, and contribute to our understanding of the excitation dynamics and chemical evolution of carbon-chain radicals in the ISM.

Key words: molecular data / molecular processes / scattering / methods: numerical / ISM: abundances

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Carbon-chain molecules, which account for around 40% of identified interstellar species to date, are essential components of the molecular cosmos (McGuire 2022). Within this diverse group, the family of hydrogen-terminated carbon-chain radicals, designated CnH (where n ≥ 1), as well as their ionized counterparts, have been detected in a variety of astrophysical environments, including cold dark clouds, active star-forming regions and the extended envelopes surrounding stars. For instance, the C4H radical, of interest in the present work, was first detected toward circumstellar envelopes of carbon-rich evolved stars IRC +10216 in 1978 by Guélin et al. (1978) and in Taurus dark clouds TMC-1 by Irvine et al. (1981) in 1981, against Cassiopeia A by Bell et al. (1983) in 1983. This was confirmed later; for instance, by Liu et al. (2024) and by Kaifu et al. (2004). In brief, the C4H detected transitions were recorded across a broad range of sources, confirming that C4H is one of the most widely distributed carbon-chain radicals in the interstellar medium (ISM). For instance, the detection of the C4H radical toward the carbon-rich star IRC+10216 was achieved through the identification of four distinct millimeter-wave emission doublets corresponding to the N = 9 → 8, 10 → 9, 11 → 10, and 12 → 11 rotational transitions (Guélin et al. 1978). These lines exhibit a spin-doublet structure caused by the interaction of the unpaired electron spin with molecular rotation, each pair being split by about 39 MHz. The observed frequencies matched theoretical predictions for a large linear radical with a 2Σ+ electronic ground state. Using dipole moments from ab initio theory computations (0.9 D for C4H, 2.2 D for C3N) and assuming optically thin emission with rotational temperatures between 60 K and 600 K, the column density of C4H in IRC+10216 is estimated to lie between 4 × 1014 and 3 × 1015 cm−2, making it potentially about four times more abundant than C3N despite similar line strengths. Besides, out of 12 dark clouds surveyed, 11 showed C4H emission. In chemically rich regions such as L1544 and L1521F, all six hyperfine components were detected, with the strongest lines exceeding 600 mK (notably the F = 3 → 2 transition at 19015.144 MHz), while weaker components such as F = 1 → 1 and F = 2 → 2 still reached ~40–70 mK. In other clouds such as L1251, Barnard 1, IRAM04191, and L1082A, detections were more limited, often restricted to the brightest hyperfine line, with peak intensities of only 20–90 mK (Gupta et al. 2009). Outside of dark clouds, C4H was identified only in the translucent cloud CB17(L1389) and in the carbon-rich circumstellar envelope CRL2688, again via the N = 2 → 1 transitions. In all cases, the detections were made in the K band (18–22 GHz) except for a few sources (e.g., L183, Barnard 1) observed in the 8–10 GHz band, where the N = 1 → 0 lines were used. The survey thus extended the known presence of C4H to six new dark clouds and confirmed its detectability across a range of environments, with the N = 2 → 1 fine- and hyperfine-structure lines serving as the primary observational tracers. This systematic detection of all six hyperfine components across multiple astrophysical environments demonstrates both the diagnostic power of C4H rotational spectroscopy and its robustness as a tracer of cold carbon-chain chemistry, providing essential observational constraints for theoretical work on fine and hyperfine (de-)excitation of C4H (X2Σ+) in low-temperature collisions with He and H2.

CnH (where n ≥ 1) molecular species originate through shared chemical pathways (Bettens & Herbst 1997; Walsh et al. 2009). Consequently, carbon-chains serve to understand the complex chemical reactions in interstellar space (Hassel et al. 2008; Taniguchi et al. 2024). For instance, numerous formation pathways have been proposed to explain their cosmic abundance. These include chemical reactions between neutral species (Hasegawa et al. 1992; Smith et al. 2004; Canosa et al. 2007) and ion-molecule reactions originating from different molecular precursors (Herbst & Leung 1989; Sakai et al. 2013), such as reactive collisions between Cn chains and H − followed by electron detachment (Senent & Hochlaf 2013).

Formations of longer carbon-chain molecules generated from basic chemical species need more reaction steps than those of shorter ones. Hence, the abundances of the C2nH molecules in a source are expected to show a gradual decrease along with the increase in the carbon-chain length regardless of whether neutral-neutral or ion-neutral reactions are occurring there. Nevertheless, the column densities of C4H in TMC-1 CP and in IRC+10216 are comparable to those of C2H, although they are two orders of magnitude larger than those of C6H (Suzuki et al. 1986; Cernicharo et al. 1987; Saito et al. 1987). The similar column densities of C4H and C2H are intriguing, motivating an in-depth investigation of the C4H radical and an accurate estimation of its abundance in astrophysical media. This is needed to understand, at the molecular level, carbon-chain chemistry, both neutral and ionic, in the ISM.

H-terminated carbon chains with even carbon atoms, such as the C4H radical, exhibit a close lying pattern of low-energy electronic states, resulting in a complex electronic structure due to the multiple possible couplings between the states (Senent & Hochlaf 2013; Mehnen et al. 2018). For instance, the C4H molecule has 2Σ+ and 2Π low-lying electronic states, and ordering them in energy depends on the nuclear configurations. Therefore, these states each cross several geometries forming conical intersections. At equilibrium, the multireference configuration interaction computations by Graf et al. (2001) showed that the ground state of C4H is of X2Σ+ in nature followed up in energy by the A2Π with an estimated excitation energy of ~0.03 eV, as was confirmed experimentally (Zhou et al. 2007; Mazzotti et al. 2011). These two states give rise to a strong vibronic coupling between both states (Yamamoto et al. 1987), where a mixing of 10% of the X2Σ+ wave function was found into the A2A′ component of the A2Π state (Graf et al. 2001). Both states are coupled vibronically and by spin-orbit at these crossings (Yamamoto et al. 1987; Oyama et al. 2020). Moreover, the A2Π is subject to the Renner-Teller effect coupled again with spin-orbit. Indeed, this doubly degenerate electronic state (Graf et al. 2001) splits into two components upon bending of the molecule, forming a pair of 2A′ and 2A″ states. These states are degenerate for planar configurations and evolve into conical intersections for C1 geometries. Accordingly, an accurate spectroscopic characterization of C4H requires consideration of the multiconfigurational characters of the wave functions of 2Σ+ and 2Π states, the Renner-Teller effect, and vibronic couplings, in addition to the nonzero spin-orbit interaction present in these doublet electronic states. This is challenging, although the C4H radical is relatively small in size.

From a theoretical point of view, such complex spectroscopic features can only be interpreted if the quantum nature of the atomic nuclei is considered together with the possible couplings between nuclear and electronic degrees of freedom. This is achieved after taking into account the rotational-vibrational and electronic angular momentum couplings via the use of approaches capable of going beyond the standard Born-Oppenheimer approximation, in which the nuclear and electronic motions in a molecule are considered. The inclusion of such couplings is mandatory for an accurate description of the spectral positions and lines in its vicinity.

In the ISM, the populations of the rovibrational levels of the molecular species are not only controlled by the temperature of the interstellar gas and the radiative processes but also by the collisional processes that govern the excitations and de-excitations between the molecular energy levels. The ISM, that occupies about 10% of the mass of our galaxy, is essentially composed of 90% of hydrogen in atomic or molecular form and 10% of helium; the other elements are present only in traces. Therefore, studying the interactions of abundant molecules in the ISM with H2 and He is of great interest for an astrophysical diagnosis. Contrary to the radiative phenomena, collisional excitation phenomena are not easy to measure in a laboratory. To determine the physico-chemical conditions of the astrophysical environments under investigation, it is thus essential to have an accurate knowledge of the collisional processes, which are characterized by temperature-dependent transition probabilities between energy states; namely, the collision rates.

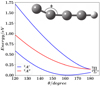

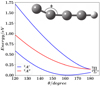

This paper focuses on the rotational excitation and de-excitation processes involving fine and hyperfine structure levels of interstellar C4H by collisions with helium atoms. Based on a newly developed potential energy surface generated along the (R, θ) Jacobi coordinates (Figure 1), we present the results of quantum scattering calculations followed by angular momentum recoupling techniques to provide a set of state-to-state rate coefficients for rotational transitions of C4H in the temperature range relevant to interstellar environments. These data should be helpful for precisely determining the abundance of this radical in the ISM, with the aim of improving astrochemical models and consequently better understanding the formation and evolution of this radical in this media.

|

Fig. 1 Coordinate system of the C4H–He complex. |

2 Generation of the C4H–He interaction potential

2.1 Electronic structure computations

In this study, we investigate the low-temperature rotational (de-)excitation of the C4H radical in collisions with He atoms. Since our focus is mainly on collision energies below the thresholds for vibrational excitation, C4H is modeled as a rigid rotor, excluding any contributions from stretching and bending vibrational modes beyond their zero-point energies. In parallel with previous studies, such as those by Faure & Josselin (2008) on H2O + H2 collisions and Spielfiedel et al. (2012) on C2H + He collisions, the approximation of decoupled rotational and bending vibrational modes is considered qualitatively valid for treating pure rotational excitations. Although neglecting rotation-vibration coupling may lead to a slight overestimation of cross sections for energetically accessible rovibrational channels, its impact on low-temperature rate coefficients is expected to be minimal. This is primarily due to the Boltzmann distribution over rotational levels, which significantly reduces the contribution of higher-energy rovibrational states to the overall rate at low temperatures.

The harmonic vibrational frequencies of the butadiynyl radical (X2Σ+) were determined by Graf et al. (2001) using high-level ab initio calculations. They reported fundamentals: v1 (C–H stretch) = 3608 cm−1, v2 (symmetric C≡C stretch) = 2301 cm−1, v3 (antisymmetric C≡C stretch) = 2131 cm−1, v4 (C–C stretch) = 924 cm−1, v5 (C–H bend) = 578 cm−1, v6 (C–C–C bend) = 379 cm−1, and v7 (C–C–C bend) = 178 cm−1. Thus, the lowest vibrational threshold lies near 178 cm−1. Below this first vibrational threshold, the rigid-rotor approximation is expected to provide an excellent description. This situation is similar to that encountered for the C2H radical, which is also linear and relatively rigid. In their detailed study of C2H–He collisions, Spielfiedel et al. (2012) treated the molecule as a rigid rotor and explicitly argued that neglecting rotation-bending coupling is justified below the first vibrational threshold (~372 cm−1) for C2H. They showed that even when this channel opens, the effect of rotation-vibration coupling is limited: cross sections may be slightly overestimated, but because of Boltzmann averaging, the impact on rate coefficients at low temperatures is only at the level of a few percent. For comparison with the floppy C3 molecule, its first bending mode lies at about 60 cm−1, which is nearly three times smaller than that of C4H (~180 cm−). This much lower bending energy makes C3 significantly more flexible and more susceptible to rovibrational coupling effects, resulting a priori in large deviations between rigid-rotor and full rovibrational calculations. The comparison of a rigid-bender and of rigid monomer approximation (RMA) close-coupling treatments Stoecklin et al. (2015) showed that the elastic cross sections are valid using RMA even for transitions between rotational levels involving the C3 bending level, in particular those located below in energy. By analogy, and noting that linear C4H is more rigid than the bent and floppier C3 radical, we expect the rigidrotor approximation to be very reliable for C4H–He collisions below ~180 cm−1. In fact, the first portion of our computed cross sections and rate coefficients, which cover this low-energy range, is fully adequate for non-local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) astrophysical modeling, the main purpose of our work. At higher collision energies (e.g. ~600 cm−1), neglecting rovibrational coupling could lead to some overestimation of cross sections, as in the case of C2H, but because higher-energy contributions are strongly suppressed in the thermal average at low and moderate temperatures, the resulting uncertainty in the rate coefficients remains small. We therefore estimate the overall error introduced by the rigid-rotor treatment in our dataset to be at most a few percent for the temperatures of astrophysical interest.

Upon interaction with the He atom, the degeneracy at linearity of the A2Π state is removed, resulting in two adiabatic electronic states of 2A′ and 2A″ symmetry in the Cs point group. The electronic wavefunctions of the two 2A′ components correlating asymptotically to C4H (X2Σ+) + He and C4H (A2Π) + He may exhibit significant mixing. Therefore, it is critical to confirm the validity of the rigid rotor approximation and the chosen single-reference electronic structure method. Figure 2 shows one-dimensional cuts of the PESs for the isolated C4H radical as a function of the external CCC bending angle, illustrating the energetic separation of its lowest electronic states. At linearity, the electronic states are X2Σ+ and A2Π. Upon bending (a nonlinear distortion), the A2Π state splits into two adiabatic electronic states (2A′ and 2A″ symmetry in the Cs point group). While the ground state also adopts 2A′ symmetry, Figure 2 clearly shows that the (X2Σ+) potential is well separated in energy from the A2Π components for C4H geometries close to equilibrium. This energy gap allows us to justify two crucial aspects for our study: i) the validity of the use of a single-reference electronic structure technique (RCCSD(T)) to compute the C4H–He interaction potential, as wavefunction mixing between the ground and excited states is negligible near the equilibrium geometry; and ii) the rigid rotor approximation for the low-temperature rotational scattering calculations, as the internal bending vibration is high enough in energy to be uncoupled from the low-energy dynamics.

C4H radical is a molecule that possesses a complex electronic structure, since the X2Σ+ and A2Π wave functions are expected to have a pronounced multiconfigurational character that should be accounted for a priori by the use of an advanced post-Hartree–Fock method for electronic structure computations. To accurately determine the energies of the lowest 2A′ state of C4H–He, our procedure involved an initial restricted Hartree–Fock (RHF) calculation followed by complete active space self-consistent field (CASSCF) calculations in the Cs point group. The three lowest doublet electronic states of this complex were averaged together at CASSCF. These states included two states with 2A′ symmetry and one with 2A″ symmetry. These CASSCF calculations utilized 17 molecular orbitals, with the four core 1s(a′) orbitals kept doubly occupied. The active space comprised 13 orbitals, where the a″ symmetry orbital was doubly occupied in the two 2A′ states and singly occupied in the 2A″ state.

Across the entire range of investigated C4H–He nuclear geometries, the coefficient of the dominant configuration state function (CSF) in the CASSCF wavefunction describing the ground 2A′ electronic state was consistently verified to exceed 0.9. This dominance further validates the use of a single-reference determinant as a suitable zeroth-order approximation, thereby justifying the application of high-accuracy single-reference coupled cluster theory for this system.

To evaluate the reliability of the single-reference RCCSD(T) treatment, we computed the T1, D1, and D2 diagnostics for the C4H–He complex at selected geometries. The values obtained (T1 = 0.0161, D1 = 0.0346, and D2 = 0.2066) lie well within the accepted thresholds for systems with a negligible multi-reference character. These results confirm that the electronic structure of the complex is adequately described by a single-determinant reference wavefunction and justify the use of the RCCSD(T) method for the potential energy surface calculations.

Subsequently, a restricted-spin explicitly correlated coupled-cluster method with single, double, and non-iterative triple excitations (RCCSD(T)-F12, approximation a), as was described by Knizia et al. (2009), was employed to compute the X2 A′ ground state PES of the C4H–He interacting system. For these coupled-cluster calculations, the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set (Dunning Jr 1989; Kendall et al. 1992) and corresponding density fitting (DF) basis sets (Yousaf & Peterson 2008) were used for the H, He, and C atoms. All electronic structure computations were performed using the MOLPRO 2021 software package (Werner et al. 2020). Afterward, we addressed the inherent basis set superposition error (BSSE) at each molecular geometry using the counterpoise correction protocol, as originally formulated by Boys & Bernardi (1970). Within this methodology, the intermolecular interaction energy (V(R, θ)) between two entities, C4H and He, is given as

![$\[V(R, \theta)=E_{\mathrm{C}_4 \mathrm{H}-\mathrm{He}}(R, \theta)-E_{\mathrm{C}_4 \mathrm{H}}(R, \theta)-E_{\mathrm{He}}(R, \theta),\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq1.png) (1)

(1)

where EC4H–He(R, θ), EC4H(R, θ), and EHe(R, θ) are the total energies of C4H–He, C4H, and He, respectively. These energies were calculated in the full basis set of the C4H–He complex.

To reduce the size inconsistency inherent in RCCSD(T)-F12 calculations arising from the inclusion of non-full triple excitations (Knizia et al. 2009; Lique et al. 2010; Hendaoui & Mehnen 2025), the interaction potential was refined. Thus, the calculated interaction energies were subjected to an energy shift. Specifically, each energy point was adjusted up by its value at a large intermolecular separation of R = 100 Bohr (approximately −5.87 cm−1). This correction ensures that the potential energy surface asymptotically approaches zero.

|

Fig. 2 MRCI + Q/aug-cc-pV(5 + d)Z 9D-PES one-dimensional cuts of the lowest electronic states of C4H. The distances are set at their values as computed at the RCCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVQZ level by Senent & Hochlaf (2009), i.e., C1−C2 = 1.2147, C2 − C3 = 1.3759, C3–C4 = 1.2102, and C4–H = 1.0630, in Å. |

2.2 Benchmarks

We conducted a set of benchmark calculations to further assess the reliability of the RCCSD(T)-F12a/aug-cc-pVTZ approach for characterizing the C4H–He interaction. In particular, we used the standard coupled cluster RCCSD(T) method (Hampel et al. 1992) extrapolated to the complete basis set (CBS) to compute the one-dimensional cuts of the C4H–He PES versus R for θ = 0°, 90°, and 180° (Figure 3). These curves also enable us to discuss the SAPT(MC) potentials (vide infra). Specifically, we computed a series of RCCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVXZ (X = T, Q, 5) single-point energies and subsequently extrapolated the respective total energies to the CBS limit using the established two-parameter exponential function proposed by Peterson et al. (1994):

![$\[E_X=E_{C B S}+A ~\exp [-(X-1)]+B ~\exp \left[-(X-1)^2\right],\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq2.png) (2)

(2)

where EX represents the electronic energy calculated with the aug-cc-pVXZ basis set, ECBS is the extrapolated energy at the CBS limit, and A and B are adjustable parameters determined by fitting the calculated energies for cardinal numbers X (typically T, Q, and 5).

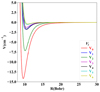

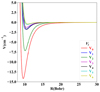

The RCCSD(T)-F12a/aug-cc-pVTZ radial potential profiles presented in Figure 3 show excellent agreement with those obtained at the RCCSD(T)/CBS level. Although slight discrepancies in the potential energy minima are observed, they remain below 1 cm−1 and are expected to have a negligible impact on subsequent scattering calculations. The RCCSD(T)-F12a/aug-cc-pVTZ approach indeed provides results that are comparable to those obtained from conventional RCCSD(T) calculations extrapolated to the CBS limit, but at a significantly reduced computational cost, as has been highlighted (Knizia et al. 2009). The explicit inclusion of terms that depend on the interelectronic distance within the F12 methods leads to a much faster convergence of the correlation energy with respect to the basis set size, allowing for the use of smaller basis sets such as aug-cc-pVTZ to reach near-CBS quality results. This is in line with the findings in the literature. Indeed, it is proven that the (R)CCSD(T)-F12/aug-cc-pVTZ method represents a computationally efficient strategy for achieving high accuracy in electronic structure calculations for carbon-chain-bearing weakly bound complexes (Lique et al. 2010; Al Mogren et al. 2014; Hochlaf 2017; Mehnen & Hendaoui 2025).

To validate the long-range (LR) behavior of the C4H–He interaction potential, we performed symmetry-adapted perturbation theory (SAPT) analysis with a multiconfigurational reference, a method capable of accurately describing intermolecular interactions involving open-shell systems exhibiting a strong electronic correlation (Hapka et al. 2021). In particular, this method is suited for accurately treating systems with a multireference character and a fortiori the case of C4H as was discussed above. In this approach, the monomer wavefunctions are treated at the CASSCF level. As is shown in Figure 3, the LR accuracy of the RCCSD(T)-F12/aug-cc-pVTZ two-dimensional potential was evaluated by comparing it with the LR interaction energies obtained from the SAPT(MC) approach for radial cuts at θ = 0°, 90°, and 180°. The deviations between the two methods were smaller than 0.5 cm−1, indicating excellent agreement. Such a high level of accuracy between RCCSD(T)-F12 and SAPT calculations has also been reported for several neutral and ionic species interacting with helium, including MgS (Hendaoui et al. 2025), c-CaC2 (Hendaoui & Mehnen 2025), c-SiC2 (Mehnen & Hendaoui 2025), H2Cl+ (Mehnen et al. 2024a), and H2CCCH+ (Mehnen et al. 2024b). Moreover, these SAPT(MC) computations enabled the identification of the primary components governing the LR interaction between C4H and He. Specifically, the dominant contributions were determined to be dipole-induced dispersion and dipole-induction interactions, both of which result in LR interaction energies exhibiting an R−6 dependence on the intermolecular separation.

Figure 3 shows the calculated SAPT(MC) radial cuts of the PES along the intermolecular distance for θ = 0°, 90°, 180° and their comparison to those obtained using RCCSD(T)–F12a/aug–cc–pVTZ, RCCSD(T)–F12b/aug-cc-pVTZ as well as with the RCCSD(T)/CBS extrapolated results. Figure 3 reveals that, for large intermonomer seperations, there is excellent agreement between SAPT(MC) and the high-level RCCSD(T)/CBS potentials, with a small difference of less than 0.5 cm−1 in the LR region of the potential. Nevertheless, the differences are relatively large in the short-range region (i.e., near the potential minimum), as is expected for SAPT calculations (Ajili et al. 2022; Derbali et al. 2023), in particular for complex nonlinear configurations. Therefore, SAPT(MC) is a reliable method of constructing accurate LR interaction potentials of van der Waals systems where electron correlation and multireference effects are significant. To further validate the LR behavior of the two-dimensional potential energy surface (2D-PES), the asymptotic region of the isotropic component, V0, was compared to the expected −C6/R6 dependence, where C6 denotes the leading induced dipole-induced dipole coefficient characterizing the C4H–He interaction. Based on these benchmarks, we confirm once more that the RCCSD(T)-F12a/aug-cc-pVTZ technique is highly effective for accurately mapping the interaction potential of long carbon chains interacting with He, providing a robust framework for further studies on collisional dynamics and related applications (Lique et al. 2010).

|

Fig. 3 One-dimensional cuts of the C4H–He complex lowest 2A′ PES along the R (in Å) Jacobi coordinate for selected configurations as computed at different levels of theory; (a) θ = 0°, (b) θ = 90°, (c) θ = 180°. See text for more details. |

2.3 Generation and analytical expansion of the interaction potential

The 2D-PES of the C4H (X2Σ+) − He complex describing the interaction between the linear C4H and He is generated along the Jacobi coordinates (R, θ) (Figure 1). R represents the distance from the He atom to the center of mass of the C4H molecule, and θ is the angle formed by the vector ![$\[\overrightarrow{\mathrm{R}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq3.png) and the C4H molecular axis. The linear C4H molecule is aligned along the Z axis, and the entire C4H–He system is located on the XZ plane. The C4H radical’s internal geometry is fixed at its linear ground state equilibrium value: C1 − C2 = 1.2147, C2 − C3 = 1.3759, C3 − C4 = 1.2102, and C4–H = 1.0630, in Å as computed by Senent & Hochlaf (2009) at the RCCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVQZ level.

and the C4H molecular axis. The linear C4H molecule is aligned along the Z axis, and the entire C4H–He system is located on the XZ plane. The C4H radical’s internal geometry is fixed at its linear ground state equilibrium value: C1 − C2 = 1.2147, C2 − C3 = 1.3759, C3 − C4 = 1.2102, and C4–H = 1.0630, in Å as computed by Senent & Hochlaf (2009) at the RCCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVQZ level.

To construct the 2D-PES, a complete set of 969 single-point energy calculations, for nonequivalent geometries, was performed. These calculations cover a range of nuclear configurations, including equilibrium geometry, as well as shortand long-range interaction regions of the C4H–He complex. The intermolecular radial coordinate, R, was assigned 51 discrete values, ranging from 4.0 Bohr to 50.0 Bohr, with a finer step of 0.2 Bohr used in the short-range region. The intermolecular angular coordinate, θ, was sampled uniformly from 0° to 180° in 10° increments.

In order to be incorporated into quantum scattering calculations, the 2D-PES for the C4H–He interaction first had to be expressed analytically. This was achieved by fitting the ab initio computed interaction energies for different nuclear configurations to a suitable functional form commonly used for linear molecule-atom systems, using a least-squares fitting approach. To solve the close-coupling equations, the resulting analytical potential was then expanded in terms of Legendre polynomials as follows:

![$\[\mathrm{V}(R, \theta)=\sum_{l=0}^{l_{\max }} V_l(R) P_l(\cos~ \theta),\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq4.png) (3)

(3)

where Pl is the Legendre polynomial of order l.

Using an ab initio computed energy grid with the chosen 37 θ angular configurations, the angular dependence was represented by a basis set of 36 Legendre polynomials, extending up to a maximum degree of lmax = 35. The precision of the least-squares fitting procedure was evaluated by evaluating the differences between the original ab initio energies and the energies reconstructed using Eq. (3) on the same grid.

To rigorously assess the quality of the fit PES, we did not rely on the same points used in the fitting process. Instead, an independent validation set of ab initio geometries (R, θ) was employed. This ensured that the evaluation was unbiased and confirmed that the PES was not overfit. The accuracy of the representation was quantified using both the mean relative error (MRE) and the root mean square error (RMSE), defined as

![$\[\text { RMSE }=\sqrt{\frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N\left(\frac{V_i^{{fit }}-V_i^{a b ~ initio}}{V_i^{a b ~initio}}\right)^2},\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq5.png) (4)

(4)

where ![$\[V_{i}^{f i t}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq6.png) and

and ![$\[V_{i}^{a b ~initio}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq7.png) are the fit and reference interaction energies at each test geometry, and N is the number of energies in the validation set. While the MRE provides a relative measure of accuracy, the RMSE is less sensitive to regions where the interaction energy is very small, and thus offers a more robust global assessment. Both matrices showed excellent agreement, confirming the reliability of the fit PES for the C4H–He system. In the present study, the values of MRE and RMSE are 0.2 and 0.5%, respectively. The full set of Vl(R) terms as a function of the radial coordinate (R) are listed in Table S1 of the supplementary material.

are the fit and reference interaction energies at each test geometry, and N is the number of energies in the validation set. While the MRE provides a relative measure of accuracy, the RMSE is less sensitive to regions where the interaction energy is very small, and thus offers a more robust global assessment. Both matrices showed excellent agreement, confirming the reliability of the fit PES for the C4H–He system. In the present study, the values of MRE and RMSE are 0.2 and 0.5%, respectively. The full set of Vl(R) terms as a function of the radial coordinate (R) are listed in Table S1 of the supplementary material.

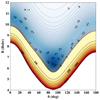

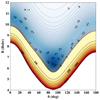

For illustration, Figure 4 shows the first seven Vl terms (for l ≤ 6) along the radial coordinate (R). V0 represents the isotropic term of the potential, and Vl>0 describe the anisotropy of the interacting potential. This figure shows that the latter make a relatively important contribution, in particular the V2 term. This will induce propensity rules for the (de-)excitation transitions, as was confirmed after dynamical treatment of nuclear motions (vide infra).

|

Fig. 4 Vl(R) terms as a function of the radial coordinate (R) for values of l up to 6. |

|

Fig. 5 2D contour plot of the C4H–He 2D-PES as a function of the intermolecular distance (R) and the angular coordinate (θ). The energy values, expressed in inverse centimeters, are referenced with respect to the energy of the C4H + He system at the asymptotic dissociation limit. Negative energies are represented by blue contours with energy steps of 1 cm−1, while the positive energies are depicted using yellow and red contours with energy steps of 200 cm−1. |

2.4 PES features

Figure 5 presents the 2D contour plot of the C4H–He interaction potential along the R and θ Jacobi coordinates. This figure confirms the strong anisotropy of this PES along both coordinates. We locate three minima: (i) GM, which is the global minimum with a T-shaped structure. GM is found at R = 6.4 Bohr and θ = 91°. It is associated with a potential well of −37.39 cm−1. (ii) LM1 is a local minimum where He is lying in the C4H internuclear from the H side (i.e., CCCCH–He structure) for θ = 0° and at R = 10.5 Bohr. The corresponding potential well depth is ~−26.02 cm−1. (iii) LM2 is also a linear C4H–He complex where the He atom is attached to the C4H radical from the C side (i.e., He − CCCCH structure). It can be found at the shallow potential well for θ = 180° at R = 10.1 Bohr. GM and LM1 are separated by an isomerization energy barrier located at R = 8.2 Bohr and θ = 55°, with an energy of −19.144 cm−1 relative to the dissociation limit and 18.25 cm−1 relative to the global minimum. Also, a transition state at R = 9.3 Bohr, θ = 145°, and V = −16.713 cm−1 connects GM and LM2.

Let us now compare our 2D-PES for C4H–He with the available interaction PESs of relevant systems. For the linear C4 − He complex, Lique et al. (2010) found three minima with two local ones for linear configurations (θ = 0° and 180°) and one global minimum for T-shaped geometry (θ = 90°) similar to the present case. Their global minimum is associated with a potential well of 44.3 cm−1 in depth, which is slightly deeper than the GM of C4H–He (by about 7 cm−1). For the C2H–He complex, Spielfiedel et al. (2012) found a unique minimum on their PES, with a shallower potential well depth of about −24 cm−1. This complex has a linear configuration where the He is attached to the H (i.e., CCH − He structure) similar to LM1 of C4H–He. This is about 1 cm−1 shallower than the local minimum in our PES for the linear configuration CCCCH–He. For the C3 − He complex, Abdallah et al. (2008) found a unique potential well on their PES, which corresponds to a global minimum at the T-shaped configuration with a potential well depth of 25.87 cm−1, which is 18.43 and 11.52 cm−1 shallower than those found for C4 − He and C4H–He, respectively. For the C2 − He complex, Najar et al. (2008) found two minima at linear configurations connected by a transition state at a T-shaped configuration. The C2–He global minimum is shallower by 17.39, 24.3, and 23.87 cm−1 than those of C4H–He, C4–He, and C3–He, respectively.

Besides, the comparison of the C4H–He PES with those of other carbon-based complexes reveals insightful trends about how molecular size and structure influence interaction potentials with helium. The C4H–He complex displays a strongly anisotropic PES. Notably, the global minimum of C4H–He (−37.39 cm−1) is significantly deeper than that of C2H–He (−24 cm−1), indicating a stronger interaction due to the increased size and polarizability of the larger carbon chains. Interestingly, while C4–He exhibits an even deeper global minimum (−44.3 cm−1), the presence of hydrogen atom within C4H–He slightly reduces the interaction strength, possibly due to electronic effects that influence the potential well depth. The C3–He complex, with a global minimum at −25.87 cm−1, shows a weaker interaction compared to both C4–He and C4H–He, which suggests a progressive enhancement in interaction strength while increasing carbon chain length. In contrast, the C2–He weakly bound system behaves differently, with two global minima at linear geometries and a shallower well (−20 cm−1), differing from the T-shaped preference observed in larger systems. This trend highlights how the molecular geometry and the number of carbon atoms significantly modulate the anisotropy and depth of interaction potentials with helium, with C4H–He representing a transitional case where both linear and T-shaped configurations are energetically favorable, though the T-shaped configuration remains dominant.

It turns out from this comparison that although some potential features are common to Cn and CnH species interacting with He, there are diverse potentials. One needs to generate the specific potential to accurately characterize the corresponding Cn/CnH − complexes. Consequently, these PES features influence the inelastic scattering cross sections and energy transfer efficiencies, particularly under low-temperature conditions. Indeed, these similarities and differences in the PES features of the carbon chain containing weakly bound systems are reflected in their cross sections and rates while colliding with H2 or He.

3 Low-energy collisions between C4H (X2Σ+) and He

3.1 Fine and hyperfine structure of C4H(X2Σ+)

For the C4H molecule in its X2Σ+ electronic ground state, the nuclear rotational angular momentum and the electronic spin couple according to Hund’s case (b) limit. This coupling results in fine structure levels characterized by the quantum number j, which is the sum of the nuclear rotational angular momentum, N, and the electronic spin, S(j = N + S). Given that the electronic state is of 2Σ+ symmetry species, the electronic spin S is 1/2, leading to two possible values of j for a given N: j = N + 1/2 and j = N − 1/2.

The total energy, E, of the C4H–He collision system is the sum of the C4H molecule’s internal rotational energy, ENj, and the kinetic energy of the He projectile, Ek:

![$\[E=E_k+E_{N_j},\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq8.png) (5)

(5)

where the fine structure of the C4H rotational energy levels is given by the following expression (Alexander 1982):

![$\[\begin{aligned}E_{N_j}= ~& B_0 N(N+1)-D_0 N^2(N+1)^2 \\& +\frac{1}{2} \gamma_0[j(j+1)-N(N+1)-S(S+1)],\end{aligned}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq9.png) (6)

(6)

where B0 represents the rotational constant in the ground vibrational level, D0 is the centrifugal distortion constant in the ground vibrational level, and γ0 is the spin-rotation coupling constant.

The fine energy levels of the C4H radical used in the present calculations were determined using Eq. (3). These energies were evaluated based on the spectroscopic constants: the rotational constant, B0 = 0.1587 cm−1, the centrifugal distortion constant, D0 = 2.8773 × 10−8 cm−1, and the spin-rotation constant, γ0 = +0.6(2) × 10−3 cm−1 (Dismuke et al. 1975; Cummins et al. 1980; Gottlieb et al. 1983). Besides, the hydrogen nucleus possesses a nonzero nuclear spin: I = 1/2. The interaction between this nuclear spin, I, and the total molecular angular momentum, j, leads to a hyperfine splitting of each fine structure level into two hyperfine levels. These hyperfine levels are characterized by the quantum number, F, which arises from the coupling of I and j(F = I + j), and takes values ranging from |I − j| to |I + j|. For C4H, the hyperfine coupling constants are b = 5.059 × 10−4 cm−1 and c = 1.334 × 10−4 cm−1 (Wilson & Green 1977).

Table S2 lists the energies of the fine and hyperfine structure levels of the C4H radical in its ground electronic state, X2Σ+, up to approximately 67 cm−1, which were considered in the present study. The resulting pattern of both fine and hyperfine levels is systematically arranged and clearly shown in Table S2. This table illustrates that the fine levels arise from the interaction between the rotational motion of the molecule and the unpaired electron spin, which is characteristic of open-shell species in a Σ electronic state. As can be seen there, the fine levels are split into closely spaced doublets due to spin-rotation coupling. This splitting increases with the rotational quantum number, N, as is expected for linear radicals in a 2Σ+ state. Each rotational level, N, is split into two fine components with a total angular momentum of J = N ± 1/2. Furthermore, for levels where hyperfine structure is resolved, the additional splitting due to the nuclear spin of the hydrogen atom (with I = 1/2) is apparent, giving rise to multiple hyperfine components for each fine level. The systematic nature of this splitting provides valuable insights into the coupling mechanisms at play and confirms the expected behavior based on effective Hamiltonian models. This detailed structure aids in accurate spectral assignments and supports a precise characterization of the molecule’s internal dynamics.

3.2 Quantum scattering calculations

The collision dynamics between the C4H molecule in its X2Σ+ electronic ground state and a helium atom are modeled as a quantum scattering problem. According to Corey & McCourt (1983), the electronic spin remains a spectator during these collisions, as the interaction potential is purely electrostatic, and thus unaffected by electronic spin degrees of freedom. To compute the spin-independent scattering matrix, ![$\[S_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq10.png) , the total angular momentum quantum number, J, is introduced, coupling the rotational angular momentum, N, of C4H with the orbital angular momentum, l, of the collision complex, where J = N + l. The primed indices, N′ and l′, denote the corresponding quantum numbers after the collision. The transition matrix elements,

, the total angular momentum quantum number, J, is introduced, coupling the rotational angular momentum, N, of C4H with the orbital angular momentum, l, of the collision complex, where J = N + l. The primed indices, N′ and l′, denote the corresponding quantum numbers after the collision. The transition matrix elements, ![$\[T_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq11.png) , are defined in terms of the scattering matrix elements,

, are defined in terms of the scattering matrix elements, ![$\[S_{N^{\prime} l^{\prime}, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq12.png) , through the following relation:

, through the following relation:

![$\[T_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^J=\delta_{N^{\prime} N^{\prime}, l^{\prime} l^{\prime}}-S_{N^{\prime} l^{\prime}, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^J,\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq13.png) (7)

(7)

where δNN′,ll′ is the product of Kronecker deltas δNN′ δll′. This product equals unity if and only if both the rotational quantum number, N, equals N′ and the orbital angular momentum quantum number, l, equals l′, and is zero otherwise.

Following the approach developed by Corey & McCourt (1983); Corey (1984), the spin-independent transition matrix elements, ![$\[T_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq14.png) , obtained from scattering calculations that neglect spin, can be recoupled to yield the spin-resolved matrix elements,

, obtained from scattering calculations that neglect spin, can be recoupled to yield the spin-resolved matrix elements, ![$\[T_{N l, N^{\prime} l}^{K}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq15.png) , which govern transitions between the fine-structure levels of the C4H (X2Σ+)molecule.

, which govern transitions between the fine-structure levels of the C4H (X2Σ+)molecule.

![$\[\begin{aligned}T_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^K= & (2 K+1)(-1)^{N+l^{\prime}} \sum_J(-1)^J(2 J+1) \\& \times\left\{\begin{array}{ccc}N^{\prime} & N & K \\l^{\prime} & l & J\end{array}\right\} T_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^J.\end{aligned}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq16.png) (8)

(8)

The tensor order, K, can be identified with the amount of angular momentum transferred between the initial and final molecular states during the collision; it is bounded by |N − N′| ≤ K ≤ |N + N′|. Therefore, the inelastic cross sections, ![$\[\sigma_{N_j \rightarrow N_{j^{\prime}}^{\prime}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq17.png) , for transitions between specific fine-structure levels, denoted by the initial state, Nj, and the final state,

, for transitions between specific fine-structure levels, denoted by the initial state, Nj, and the final state, ![$\[N_{j^{\prime}}^{\prime}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq18.png) , are obtained through the recoupling approach of Corey et al. (1986), as follows:

, are obtained through the recoupling approach of Corey et al. (1986), as follows:

![$\[\sigma_{N_j \rightarrow N_{j^{\prime}}^{\prime}}=\frac{\pi}{k_N^2}\left(2 j^{\prime}+1\right) \sum_K\left\{\begin{array}{rrr}N^{\prime} & N & K \\j^{\prime} & j & S\end{array}\right\}^2 P^K\left(N, N^{\prime}\right),\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq19.png) (9)

(9)

where all-spin-free tensor opacities, PK (N, N′), are expressed as follows:

![$\[P^K\left(N, N^{\prime}\right)=\frac{1}{2 N+1} \sum_{l l^{\prime}}\left|T_{N l N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^K\right|^2.\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq20.png) (10)

(10)

In the equations above, the 6j Wigner symbol, denoted as {:::}, describes the recoupling required to represent transitions between the fine-structure levels of C4H. Specifically, it inherently incorporates the coupling of the initial rotational (N) and spin (S) angular momenta to form the initial total molecular angular momentum (j). Simultaneously, it connects the initial and final rotational angular momenta (N and N′) and the initial and final total molecular angular momenta (j and j′) in the construction of a rank K tensor (Alexander et al. 1986). The cross sections for transitions between hyperfine levels can be determined from the nuclear spin-independent T-matrix elements by employing the angular momentum recoupling methodology developed by Alexander & Dagdigian (1985). This approach is fully validated by the extremely small energy separation between hyperfine levels. Therefore, the inelastic cross sections for transitions from an initial hyperfine level, NjF, to a final hyperfine level, N′ j′ F′, were derived as follows:

![$\[\begin{aligned}\sigma_{N j F \rightarrow N^{\prime} j^{\prime} F^{\prime}}= & \frac{\pi}{k_{N j F}^2}(2 j+1)\left(2 j^{\prime}+1\right)\left(2 F^{\prime}+1\right) \\& \times \sum_K\left\{\begin{array}{rrr}j & j^{\prime} & K \\F^{\prime} & F & I\end{array}\right\}^2\left\{\begin{array}{rrr}N & N^{\prime} & K \\j^{\prime} & j & S\end{array}\right\}^2 \\& \times P^K\left(N, N^{\prime}\right),\end{aligned}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq21.png) (11)

(11)

where PK (N, N′) is the all-spin-free tensor opacity as expressed by Eq. (8).

In this work, to investigate the inelastic collision dynamics of the C4H (X2Σ+) − He system, the scattering problem was first simplified to the collision case of a molecule in the X1 Σ+ electronic state with a helium atom. This reduction allowed for the computations of the spin-independent scattering matrix, ![$\[S_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq22.png) , for C4H interacting with He on our newly generated PES, where this radical is considered in a singlet electronic spin state (i.e., 1Σ+) rather than a 2Σ+. Then, spin-independent state-to-state rotational excitation and de-excitation cross sections are calculated using a fully quantum mechanical close-coupling (CC) approach (Arthurs & Dalgarno 1960; Flower 2007), as implemented in the MOLSCAT 2022 software package (Hutson & Le Sueur 2019). For these dynamical calculations, we implemented the analytical form of the 2D-PES of the C4H–He system described above. This PES was directly coupled to the CC equations solver to determine the spin-independent scattering matrix,

, for C4H interacting with He on our newly generated PES, where this radical is considered in a singlet electronic spin state (i.e., 1Σ+) rather than a 2Σ+. Then, spin-independent state-to-state rotational excitation and de-excitation cross sections are calculated using a fully quantum mechanical close-coupling (CC) approach (Arthurs & Dalgarno 1960; Flower 2007), as implemented in the MOLSCAT 2022 software package (Hutson & Le Sueur 2019). For these dynamical calculations, we implemented the analytical form of the 2D-PES of the C4H–He system described above. This PES was directly coupled to the CC equations solver to determine the spin-independent scattering matrix, ![$\[S_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq23.png) , involving the low-lying rotational levels of the C4H molecule.

, involving the low-lying rotational levels of the C4H molecule.

Integral spin-independent cross sections were determined at each total energy by summing partial cross sections over the total angular momentum (J) until convergence was achieved. The scattering calculations employed the propagator method developed by Manolopoulos (1986). The reduced mass of the C4H–He collisional system is 3.7006 atomic mass units (amu). Propagation parameters were meticulously optimized to guarantee convergence of the cross sections for total energies up to 620 cm−1. The radial integration was performed over a range from 4.2 Bohr to 30 Bohr, ensuring the reliability of the computed ![$\[S_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq24.png) .

.

At present, a rotational basis set extending to jmax = 28 is found to be adequate for obtaining converged spin-independent cross sections for energies up to 620 cm−1. Besides, a careful selection of energy intervals and step sizes is implemented in order to capture any resonant structures in the cross sections. Specifically, energy steps of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, and 2 cm−1 are used across the energy ranges of 0.1–100 cm−1, 100–200 cm−1, 200 − 300 cm−1, and 300–620 cm−1, respectively. Moreover, the propagation step size is dynamically adjusted based on the collision energy to optimize the balance between computational cost and result accuracy. Therefore, the STEPS parameter in the MOLSCAT code is set as follows. For collision energies up to 100 cm−1, a STEPS value of 80 is used. This value is then reduced to 50 for the energy range of 100–300 cm−1 and further decreased to 30 for energies between 300 and 620 cm−1. This strategy ensures sufficient accuracy at lower energies where the de Broglie wavelength is longer, while reducing computational effort at higher energies. The energies of the allowed transitions are listed in Table S3.

Afterward, the spin-independent scattering matrices, ![$\[S_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq25.png) , obtained from these calculations are used to compute the transition matrix elements

, obtained from these calculations are used to compute the transition matrix elements ![$\[T_{N l, N^{\prime} l^{\prime}}^{J}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq26.png) , which govern the transitions between the fine-structure levels of the C4H (X2Σ+)molecule. We then applied the recoupling approach of Corey et al. (1986) to the opacity tensor, PK (N, N′), to drive the inelastic cross sections,

, which govern the transitions between the fine-structure levels of the C4H (X2Σ+)molecule. We then applied the recoupling approach of Corey et al. (1986) to the opacity tensor, PK (N, N′), to drive the inelastic cross sections, ![$\[\sigma_{N_{j} \rightarrow N_{j^{\prime}}^{\prime}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq27.png) , for transitions between fine-structure levels Nj and

, for transitions between fine-structure levels Nj and ![$\[N_{j^{\prime}}^{\prime}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq28.png) , as defined in Eq. (9). Our convergence tests with respect to the rotational basis set size (Nmax) demonstrated that the rotational cross sections are well converged up to 620 cm−1 for Nmax = 28. For each collision energy, the total angular momentum quantum number, Jtot, was selected to be sufficiently large to ensure convergence of the total cross sections within 0.01 Å2. At the maximum considered total energy of 620 cm−1, Jtot values extended up to 91. The computed cross sections for C4H–He fine-structure levels up to a total energy of 620 cm−1 enable the determination of the corresponding inelastic collision rate coefficients up to a temperature of 100 K for transitions involving the lowest rotational levels, up to N = 20 and j = 20.5. The corresponding rate coefficients at a given temperature, T, can be computed by thermally averaging over the collision kinetic energy (Ek) according to the following expression:

, as defined in Eq. (9). Our convergence tests with respect to the rotational basis set size (Nmax) demonstrated that the rotational cross sections are well converged up to 620 cm−1 for Nmax = 28. For each collision energy, the total angular momentum quantum number, Jtot, was selected to be sufficiently large to ensure convergence of the total cross sections within 0.01 Å2. At the maximum considered total energy of 620 cm−1, Jtot values extended up to 91. The computed cross sections for C4H–He fine-structure levels up to a total energy of 620 cm−1 enable the determination of the corresponding inelastic collision rate coefficients up to a temperature of 100 K for transitions involving the lowest rotational levels, up to N = 20 and j = 20.5. The corresponding rate coefficients at a given temperature, T, can be computed by thermally averaging over the collision kinetic energy (Ek) according to the following expression:

![$\[k_{N_j \rightarrow N_{j^{\prime}}^{\prime}}(T)=\left(\frac{8}{\pi \mu\left(k_B T\right)^3}\right)^{1 / 2} \times \int_0^{+\infty} \sigma_{N_j \rightarrow N_{j^{\prime}}^{\prime}} E_k e^{-\frac{E_k}{k_B T}} d E_k,\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq29.png) (12)

(12)

where kB is Boltzmann’s constant and the integral extends over all values of the collision energy.

Utilizing the calculated rotationally inelastic cross sections, denoted as σNjF→N′j′F(Ek), the corresponding thermal rate coefficients at a given temperature, T, can be determined by averaging over the collision kinetic energy (Ek) according to the following expression:

![$\[k_{N j F \rightarrow N^{\prime} j^{\prime} F^{\prime}}(T)=\left(\frac{8}{\pi \mu~\left(k_B T\right)^3}\right)^{1 / 2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq30.png) (13)

(13)

![$\[\times \int_0^{+\infty} \sigma_{N j F \rightarrow N^{\prime} j^{\prime} F^{\prime}} E_k e^{-\frac{E_k}{k_B T}} d E_k.\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq31.png) (14)

(14)

3.3 (De-)excitation of the C4H fine structure by He collisions

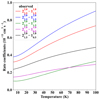

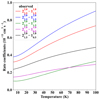

In Figures 6a and 6b, we display the kinetic energy dependence of the (de-)excitation cross sections for selected rotational transitions characterized by Δj = ΔN = 1, 2 and Δj = ΔN + 1. The excitation and de-excitation cross sections obey the principle of detailed balance, which relates them at a fixed total energy, E, as follows:

![$\[\frac{\sigma_{i \rightarrow f}(E)}{\sigma_{f \rightarrow i}(E)}=\frac{\left(2 j_f+1\right)\left(E-\varepsilon_f\right)}{\left(2 j_i+1\right)\left(E-\varepsilon_i\right)}.\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq32.png) (15)

(15)

Here, σi→f(E) and σf→i(E) denote the cross sections for transitions from state i to f, and vice versa, respectively. εi and εf represent the internal energies of states i and f. It is important to note that this relation holds at constant total energy, not at constant collision energy. Similarly, the thermal rate coefficients for excitation and de-excitation satisfy the detailed balance condition

![$\[\frac{k_{f \rightarrow i}(T)}{k_{i \rightarrow f}(T)}=\frac{g_i}{g_f} e^{\Delta E / k_B T},\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq33.png) (16)

(16)

where kf→i(T) and ki→f(T) are the temperature-dependent rate coefficients for excitation and de-excitation, respectively. The statistical weights are given by gf = 2ji + 1 and gi = 2jf + 1, corresponding to the degeneracies of the initial and final states. ΔE = εi − εf corresponds to the energy difference between the i and f states, and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

Figure 6 shows that the employed energy grid fully captures the resonance features and ensures the correct asymptotic behavior of the cross sections. The accurate description of resonances at low energies, including both Feshbach and shape resonances, demonstrates the necessity of the finely spaced energy grid used in the present scattering calculations. The Feshbach resonances result from the temporary trapping of the helium atom in the potential well, leading to the formation of quasi-bound states within the C4H–He van der Waals complex potential. In contrast, shape resonances arise from quasi-bound states formed through quantum tunneling across the centrifugal barrier ![$\[\left(\frac{l(l+1) \hbar^{2}}{2 \mu R^{2}}\right)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa56913-25/aa56913-25-eq34.png) .

.

Close examination of these cross sections reveals a pronounced propensity for transitions with Δj = ΔN = 2, with the associated rate coefficients exceeding those of Δj = ΔN = 1 transitions by up to a factor of two. This observed preference for Δj = 2 transitions can be attributed to the dominant contribution of the second-order anisotropic term (V2) in the interaction potential, as is evidenced in the analytical decomposition presented in Figure 4. In particular, the V2 term effectively couples rotational states separated by two units of angular momentum, thereby enhancing the transition probability in this channel and making transitions involving Δj = 2 energetically and dynamically more favorable, leading to higher de-excitation rates in this channel compared to Δj = 1 or Δj = ΔN + 1 processes. Moreover, it is worth highlighting a clear propensity for transitions where the change in total angular momentum (Δj) is equal to the change in rotational quantum number (ΔN). The cross sections corresponding to these Δj = ΔN transitions are indeed significantly higher than those for transitions where Δj ≠ ΔN. This specific behavior, where Δj = ΔN transitions are favored in collisions between molecules in a 2S + 1 electronic state and a rare gas atom, was theoretically predicted some time ago (Alexander et al. 1986). Subsequent studies have also observed this propensity in various other molecular systems, such as C2H colliding with He (Spielfiedel et al. 2012). Furthermore, the data reveals a propensity for transitions involving even values of N, particularly N = 2 as is illustrated in Figure 6. This observed preference arises from the near-homonuclear symmetry of the PES. This effect is a well-established experimental finding, an initial theoretical explanation of which has previously been provided by McCurdy & Miller (1977).

3.4 Hyperfine de-excitation of C4H by He collisions

Figures 7c and 7d displays the computed rate coefficients for hyperfine de-excitation of C4H induced by collisions with helium, focusing on selected transitions from N = 3 and 4, j, F → N′ = 2, j′, F′, where Δj = ΔN and Δj = ΔN + 1, respectively. The results reveal a comparable propensity for transitions with ΔN = 2 and Δj = ΔN, consistent with patterns previously identified in fine-structure resolved collisional rate coefficients. Notably, transitions where Δj = ΔF exhibit enhanced rate coefficients, and this preference becomes more pronounced with increasing N. Furthermore, for these particular ΔN = 2 and Δj = ΔN transitions, a strong tendency toward transitions with Δj = ΔF is evident, and this trend becomes more pronounced as N increases. These observed propensities align with theoretical predictions made by Alexander & Dagdigian (1985) and Corey & Alexander (1988). Notably, Spielfiedel et al. (2012) reported similar trends in their study of C2H–He collisions. In contrast, as is shown in Figure 8, for transitions where Δj = ΔN = 1 and 2, no clear propensity rule emerges. Specifically, the cross sections do not show a direct proportionality to the degeneracy of the final hyperfine level, which is given by (2F′ + 1).

The rotational spectrum of the C4H radical was systematically examined by Gupta et al. (2009) in a range of Galactic molecular environments, with a special focus on the N = 2 → 1 transitions, which provide the strongest low-frequency lines accessible in the 18–22 GHz band and are well populated in cold clouds (T ≈ 10 K). Within these transitions, two distinct fine-structure ladders were observed, each further split into hyperfine subcomponents owing to the interaction of the hydrogen nuclear spin with the unpaired electron in the X2Σ+ ground state. The first fine-structure ladder, N, j = 2, 2.5 → 1, 1.5, yielded three clearly detectable hyperfine components: F = 2 → 1 at 19014.720 MHz, F = 3 → 2 at 19015.144 MHz, and F = 2 → 2 at 19025.107 MHz. The second fine-structure ladder, N, j = 2, 1.5 → 1, 0.5, also gave three measurable hyperfine lines: F = 1 → 1 at 19044.760 MHz, F = 2 → 1 at 19054.476 MHz, and F = 3 → 2 at 19055.947 MHz. Together, these six hyperfine components formed a complete hyperfine set of N = 2 → 1 transitions of C4H (X2Σ+) targeted in the survey. As is shown in Figure 9, the rate coefficients of these transitions have a smaller magnitude (<10−11 cm3.s−1 for T < 100 K) compared to some rates discussed above. We thus strongly suggest using the transitions that have rates of >10−11 cm3.s−1 in Figure 8 to detect the C4H radical in cold astrophysical media.

|

Fig. 6 Excitation (a, c) and de-excitation (b, d) state-to-state rotational cross sections as a function of kinetic energy (a, b) and temperature-dependent rate coefficients (c, d) for transitions N, j → N′, j′ with Δj = ΔN = ±1, ±2 and Δj = ±(ΔN + 1). |

|

Fig. 7 State-to-state rotational excitation (a, c) and de-excitation (b, d) cross sections as a function of kinetic energy (a, b) and the temperature dependence of hyperfine-resolved rate coefficients (c, d) are presented for the transitions |

4 Conclusion

In this work, we have conducted a detailed quantum mechanical study of the fine and hyperfine de-excitation dynamics of the C4H radical in collisions with helium, covering the low-temperature regime characteristic of interstellar environments. We started by generating a high-quality 2D-PES for the C4H–He weakly bound complex. This PES was constructed using explicitly correlated RCCSD(T)-F12/aug-cc-pVTZ technique. Benchmarks showed that this PES accurately captures the complex anisotropic nature of the C4H–He weak interaction, revealing three energetically favorable configurations: a global minimum at the T-shaped geometry and two secondary local minima at linear configurations. This anisotropy plays a key role in determining the state-to-state inelastic cross sections and the associated rate coefficients.

Using this PES, close-coupling quantum scattering calculations were performed, followed by angular momentum recoupling techniques to obtain rotationally resolved fine-structure and hyperfine-structure cross sections and temperature-dependent rate coefficients for transitions involving the lowest 21 rotational levels (N = 0–20) of C4H as specified in Table S3. The computed rate coefficients exhibit clear propensities for fine transitions where the change in total angular momentum (Δj) equals the change in the rotational quantum number (ΔN), with Δj = ΔN = 2 transitions being particularly favored. This behavior is directly linked to the significant contribution of the second-order anisotropic term (V2) in the C4H–He 2D-PES expansion, which facilitates efficient coupling between rotational states differing by two quanta. Furthermore, the hyperfine resolved rate coefficients, derived via angular momentum recoupling, show enhanced probabilities for transitions satisfying ΔF = Δj, especially at higher rotational levels. These propensities are consistent with earlier theoretical predictions and are influenced by both the spin-rotation coupling and the weak hyperfine splitting of C4H. Besides, this work highlights the importance of considering fine and hyperfine structure in modeling collisional processes, particularly for radicals with open-shell electronic configurations.

The data presented here represent the first set of fine- and hyperfine-resolved collisional rate coefficients for the C4H–He system. These results are directly applicable to non-LTE radiative transfer modeling in the ISM and will be instrumental in interpreting observations of C4H and related carbon-chain molecules in dark clouds and circumstellar envelopes. Moreover, this study contributes to a broader understanding of the complex carbon-chain chemistry and the role of collisional excitation in shaping the molecular emission spectra of cold astrophysical environments. Future work may extend these calculations to include collisions with molecular hydrogen (H2), the dominant component of the ISM, as well as incorporate vibrational excitation effects to further refine astrophysical models.

|

Fig. 8 State-to-state rotational excitation (a, c) and de-excitation (b, d) cross sections as a function of kinetic energy (a, b) and the temperature dependence of hyperfine-resolved rate coefficients (c, d) are presented for the transitions |

|

Fig. 9 Temperature dependence of the hyperfine-resolved rate coefficients for the observed transitions. |

Data availability

The complete set of the computed rate coefficients governing the fine and hyperfine (de)-excitation processes of C4H due to inelastic collisions with He atoms will be accessible online in the BASECOL (Dubernet et al. 2013, 2024) and LAMDA (Schöier et al. 2005) databases. Additional supplementary material is available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17937199.

Acknowledgements

B.M. acknowledges support from the National Science Center, Poland (SONATINA 8, Grant No. 2024/52/C/ST9/00124). The COST Actions CA21101 – Confined Molecular Systems: from a new generation of materials to the stars (COSY) and CA21126 – Carbon molecular nanostructures in space (NanoSpace) of the European Community are acknowledged for support.

References

- Abdallah, D. B., Hammami, K., Najar, F., et al. 2008, ApJ, 686, 379 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ajili, Y., Quintas-Sánchez, E., Mehnen, B., et al. 2022, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 24, 28984 [Google Scholar]

- Al Mogren, M. M., Denis-Alpizar, O., Abdallah, D. B., et al. 2014, J. Chem. Phys., 141 [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. H. 1982, J. Chem. Phys., 76, 3637 [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. H., & Dagdigian, P. J. 1985, J. Chem. Phys., 83, 2191 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, M. H., Smedley, J. E., & Corey, G. C. 1986, J. Chem. Phys., 84, 3049 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Arthurs, A. M., & Dalgarno, A. 1960, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci., 256, 540 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, M. B., Feldman, P. A., & Matthews, H. E. 1983, ApJ, 273, L35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bettens, R. P. A., & Herbst, E. 1997, ApJ, 478, 585 [Google Scholar]

- Boys, S. F., & Bernardi, F. J. M. P. 1970, Mol. Phys., 19, 553 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Canosa, A., Páramo, A., Le Picard, S. D., & Sims, I. R. 2007, Icarus, 187, 558 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Guélin, M., Menten, K. M., & Walmsley, C. M. 1987, A&A, 181, L1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Corey, G. C. 1984, J. Chem. Phys., 81, 2678 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Corey, G. C., & Alexander, M. H. 1988, J. Chem. Phys., 88, 6931 [Google Scholar]

- Corey, G. C., & McCourt, F. R. 1983, J. Phys. Chem., 87, 2723 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Corey, G. C., Alexander, M. H., & Schaefer, J. 1986, J. Chem. Phys., 85, 2726 [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, S. E., Morris, M., & Thaddeus, P. 1980, ApJ, 235, 886 [Google Scholar]

- Derbali, E., Ajili, Y., Mehnen, B., et al. 2023, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 25, 30198 [Google Scholar]

- Dismuke, K. I., Graham, W. R. M., & Weltner Jr, W. 1975, J. Mol. Spectrosc., 57, 127 [Google Scholar]

- Dubernet, M.-L., Alexander, M., Ba, Y., et al. 2013, A&A, 553, A50 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dubernet, M., Boursier, C., Denis-Alpizar, O., et al. 2024, A&A, 683, A40 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning Jr, T. H. 1989, J. Chem. Phys., 90, 1007 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., & Josselin, E. 2008, A&A, 492, 257 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. 2007, Molecular Collisions in the Interstellar Medium, 42 (Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, C. A., Gottlieb, E. W., Thaddeus, P., & Kawamura, H. 1983, ApJ, 275, 916 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graf, S., Geiss, J., & Leutwyler, S. 2001, J. Chem. Phys., 114, 4542 [Google Scholar]

- Guélin, M., Green, S., & Thaddeus, P. 1978, ApJ, 224, L27 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, H., Gottlieb, C. A., McCarthy, M. C., & Thaddeus, P. 2009, ApJ, 691, 1494 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel, C., Peterson, K. A., & Werner, H.-J. 1992, Chem. Phys. Lett., 190, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hapka, M., Przybytek, M., & Pernal, K. 2021, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 17, 5538 [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa, T. I., Herbst, E., & Leung, C. M. 1992, ApJS, 82, 167 [Google Scholar]

- Hassel, G. E., Herbst, E., & Garrod, R. T. 2008, ApJ, 681, 1385 [Google Scholar]

- Hendaoui, H., & Mehnen, B. 2025, MNRAS, 539, 1180 [Google Scholar]

- Hendaoui, H., Varandas, A., & Mehnen, B. 2025, MNRAS, 537, 3091 [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, E., & Leung, C. M. 1989, ApJS, 69, 271 [Google Scholar]

- Hochlaf, M. 2017, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 19, 21236 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hutson, J. M., & Le Sueur, C. R. 2019, Comput. Phys. Commun., 241, 9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, W. M., Hoglund, B., Friberg, P., Askne, J., & Ellder, J. 1981, ApJ, 248, L113 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kaifu, N., Ohishi, M., Kawaguchi, K., et al. 2004, Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn., 56, 69 [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, R. A., Dunning Jr, T. H., & Harrison, R. J. 1992, J. Chem. Phys., 96, 6796 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knizia, G., Adler, T. B., & Werner, H.-J. 2009, J. Chem. Phys., 130 [Google Scholar]

- Lique, F., Kłos, J., & Hochlaf, M. 2010, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 12, 15672 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Wang, J., Liu, S., et al. 2024, ApJ, 969, 33 [Google Scholar]

- Manolopoulos, D. E. 1986, J. Chem. Phys., 85, 6425 [Google Scholar]

- Mazzotti, F. J., Raghunandan, R., Esmail, A. M., Tulej, M., & Maier, J. P. 2011, J. Chem. Phys., 134 [Google Scholar]

- McCurdy, C. W., & Miller, W. H. 1977, J. Chem. Phys., 67, 463 [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, B. A. 2022, ApJS, 259, 30 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mehnen, B., & Hendaoui, H. 2025, MNRAS, 543, 95 [Google Scholar]

- Mehnen, B., Linguerri, R., Yaghlane, S. B., Al Mogren, M. M., & Hochlaf, M. 2018, Faraday Discuss., 212, 51 [Google Scholar]

- Mehnen, B., Hendaoui, H., Ajili, Y., et al. 2024a, MNRAS, 529, 2753 [Google Scholar]

- Mehnen, B., Hendaoui, H., & Żuchowski, P. 2024b, MNRAS, 533, 1927 [Google Scholar]

- Najar, F., Abdallah, D. B., Jaidane, N., & Lakhdar, Z. B. 2008, Chem. Phys. Lett., 460, 31 [Google Scholar]

- Oyama, T., Ozaki, H., Sumiyoshi, Y., et al. 2020, ApJ, 890, 39 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, K. A., Woon, D. E., & Dunning Jr, T. H. 1994, J. Chem. Phys., 100, 7410 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Saito, S., Kawaguchi, K., Suzukim, H., et al. 1987, Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn., 39, 193 [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, N., Takano, S., Sakai, T., et al. 2013, J. Phys. Chem. A., 117, 9831 [Google Scholar]

- Schöier, F. L., van der Tak, F. F. S., van Dishoeck, E. F., & Black, J. H. 2005, A&A, 432, 369 [Google Scholar]

- Senent, M. L., & Hochlaf, M. 2009, ApJ, 708, 1452 [Google Scholar]

- Senent, M. L., & Hochlaf, M. 2013, ApJ, 768, 59 [Google Scholar]

- Smith, I. W. M., Herbst, E., & Chang, Q. 2004, MNRAS, 350, 323 [Google Scholar]

- Spielfiedel, A., Feautrier, N., Najar, F., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 421, 1891 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin, T., Denis-Alpizar, O., & Halvick, P. 2015, MNRAS, 449, 3420 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H., Ohishi, M., Kaifu, N., et al. 1986, Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn., 38, 911 [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi, K., Gorai, P., & Tan, J. C. 2024, Astrophys. Space Sci., 369, 34 [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, C., Harada, N., Herbst, E., & Millar, T. J. 2009, ApJ, 700, 752 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, H., Knowles, P. J., Manby, F. R., et al. 2020, WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci, 2, 242 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S., & Green, S. 1977, ApJ, 212, L87 [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, S., Saito, S., Guélin, M., et al. 1987, ApJ, 323, L149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf, K. E., & Peterson, K. A. 2008, J. Chem. Phys., 129 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J., Garand, E., & Neumark, D. M. 2007, J. Chem. Phys., 127 [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Coordinate system of the C4H–He complex. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 MRCI + Q/aug-cc-pV(5 + d)Z 9D-PES one-dimensional cuts of the lowest electronic states of C4H. The distances are set at their values as computed at the RCCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVQZ level by Senent & Hochlaf (2009), i.e., C1−C2 = 1.2147, C2 − C3 = 1.3759, C3–C4 = 1.2102, and C4–H = 1.0630, in Å. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 One-dimensional cuts of the C4H–He complex lowest 2A′ PES along the R (in Å) Jacobi coordinate for selected configurations as computed at different levels of theory; (a) θ = 0°, (b) θ = 90°, (c) θ = 180°. See text for more details. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Vl(R) terms as a function of the radial coordinate (R) for values of l up to 6. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 2D contour plot of the C4H–He 2D-PES as a function of the intermolecular distance (R) and the angular coordinate (θ). The energy values, expressed in inverse centimeters, are referenced with respect to the energy of the C4H + He system at the asymptotic dissociation limit. Negative energies are represented by blue contours with energy steps of 1 cm−1, while the positive energies are depicted using yellow and red contours with energy steps of 200 cm−1. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Excitation (a, c) and de-excitation (b, d) state-to-state rotational cross sections as a function of kinetic energy (a, b) and temperature-dependent rate coefficients (c, d) for transitions N, j → N′, j′ with Δj = ΔN = ±1, ±2 and Δj = ±(ΔN + 1). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 State-to-state rotational excitation (a, c) and de-excitation (b, d) cross sections as a function of kinetic energy (a, b) and the temperature dependence of hyperfine-resolved rate coefficients (c, d) are presented for the transitions |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 State-to-state rotational excitation (a, c) and de-excitation (b, d) cross sections as a function of kinetic energy (a, b) and the temperature dependence of hyperfine-resolved rate coefficients (c, d) are presented for the transitions |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Temperature dependence of the hyperfine-resolved rate coefficients for the observed transitions. |

| In the text | |