| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L20 | |

| Number of page(s) | 4 | |

| Section | Letters to the Editor | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202658990 | |

| Published online | 17 February 2026 | |

Letter to the Editor

Model selection with the Pantheon+ Type Ia supernova sample

1

Department of Physics, The University of Arizona Tucson Arizona 85721, USA

2

Department of Physics, The Applied Math Program, and Department of Astronomy, The University of Arizona Tucson Arizona 85721, USA

3

Purple Mountain Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences Nanjing 210023, China

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

15

January

2026

Accepted:

4

February

2026

Context. Recent discoveries, for example by JWST and DESI, have elevated the level of tension with inflationary Λ cold dark matter (ΛCDM). For example, the empirical evidence now suggests that the standard model violates at least one of the energy conditions from general relativity, which were designed to ensure that systems have positive energy, attractive gravity, and non-superluminal energy flows.

Aims. We used a recently compiled Type Ia supernova sample to examine whether ΛCDM violates the energy conditions in the local Universe, and carried out model selection with its principal competitor, the Rh = ct universe.

Methods. We derived model-independent constraints on the distance modulus based on the energy conditions and compared them with the Hubble diagram predicted by both ΛCDM and Rh = ct, using the Pantheon+ Type Ia supernova catalogue.

Results. We find that ΛCDM violates the strong energy condition over the redshift range z ⊂ (0, 2), whereas Rh = ct satisfies all four energy constraints. At the same time, Rh = ct is favoured by these data over ΛCDM with a likelihood of ∼89.8% versus ∼10.2%.

Conclusions. The Rh = ct model without inflation is strongly favoured by the Type Ia supernova data over the current standard model, while simultaneously adhering to the general relativistic energy conditions at both high and low redshifts.

Key words: cosmology: observations / cosmology: theory / dark energy

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Inflationary Λ cold dark matter (ΛCDM; Starobinskiǐ 1979; Guth 1981; Linde 1982) has been quite successful in accounting for many cosmological observations over the past few decades, most notably the multi-peak structure in the angular power spectrum of the cosmic microwave background. Though ΛCDM, like essentially all cosmological models today, is based on the Friedmann-Lema tre-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric, it is largely an empirical model, relying on 11 to 12 observationally optimized parameters. New data acquired with Planck (Planck Collaboration VI 2020), the dark energy spectroscopic instrument (DESI; DESI Collaboration 2024) and, most recently, the James Webb space telescope (JWST; Pontoppidan et al. 2022; Finkelstein et al. 2022; Mascia et al. 2024; Carniani et al. 2024), have raised major concerns regarding its status as a ‘true’ standard model (Melia 2020, 2025). For example, the discovery of supermassive black holes (Melia 2024) and well-formed galaxies (Melia 2023a) merely a few hundred million years after the Big Bang refute its predicted timeline, affirming other inconsistencies and growing tension at lower redshifts.

tre-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric, it is largely an empirical model, relying on 11 to 12 observationally optimized parameters. New data acquired with Planck (Planck Collaboration VI 2020), the dark energy spectroscopic instrument (DESI; DESI Collaboration 2024) and, most recently, the James Webb space telescope (JWST; Pontoppidan et al. 2022; Finkelstein et al. 2022; Mascia et al. 2024; Carniani et al. 2024), have raised major concerns regarding its status as a ‘true’ standard model (Melia 2020, 2025). For example, the discovery of supermassive black holes (Melia 2024) and well-formed galaxies (Melia 2023a) merely a few hundred million years after the Big Bang refute its predicted timeline, affirming other inconsistencies and growing tension at lower redshifts.

A well-known inconsistency in this model is the discordant measurement of the Hubble constant at high and low redshifts. Planck observes a value 67.4 ± 0.5 km s−1 Mpc−1 (Planck Collaboration VI 2020), which disagrees by more than 7σ with the value determined using Cepheid-calibrated Type Ia supernovae (SNe), i.e. 73.04 ± 1.04 km s−1 Mpc−1 (Riess et al. 2022). The uncertainties in these measurements have dropped as the precision has improved, so it is unlikely that the discrepancy is due to systematics. It appears that some unknown physics beyond ΛCDM is responsible for this tension.

In contrast, the Rh = ct cosmology is affected by virtually none of the inconsistencies and flaws of the ΛCDM model (Melia 2020, 2025). Over 35 different comparative tests showing that Rh = ct is favoured over ΛCDM at all redshifts have now been carried out. This alternative FLRW cosmology is better motivated theoretically, and adheres to all the known constraints from general relativity, thermodynamics, and particle physics. For example, it alone satisfies the zero active mass condition, which is required for a proper use of the FLRW ansatz.

An additional strong factor in its favour is that it does not require inflation to explain the uniformity of the cosmic microwave background temperature across the sky (Melia 2013) while still fully adhering to the energy conditions. An inflationary spurt from t = 10−35 s to 10−32 s is required in ΛCDM to solve the horizon problem, though the inflaton field violates at least one of the energy conditions in the early Universe.

The purpose of this Letter is to demonstrate that the early Universe is not the only time when ΛCDM violates these important energy constraints in general relativity. Type Ia SNe, HII galaxies, and cosmic chronometers have all hinted that ΛCDM violates them at low redshifts as well (Santos et al. 2007), while Rh = ct does not (Chandak et al. 2025). We used the latest Type Ia SN catalogue for model selection between these two cosmologies, and robustly tested their fits against the energy conditions at z ≲ 2.

2. Background

Type Ia SNe have been used previously for model selection between ΛCDM and Rh = ct (Wei et al. 2015; Melia et al. 2018). But we now have access to the best spectroscopically confirmed measurements in the Pantheon+ sample (Scolnic et al. 2022), which we used in our analysis. The novelty in our approach is that we also introduce model-independent bounds on the distance modulus based on the strong energy condition (SEC) from general relativity. The energy conditions were introduced to ensure that the chosen stress-energy tensor in Einstein’s equations does not contain negative energy densities (the null and the weak energy conditions), and to ensure that the source of gravity is attractive (the SEC) and does not lead to superluminal energy flows (the dominant energy condition).

The Rh = ct universe (Melia 2007; Melia & Shevchuk 2012) has emerged as the best challenger to the current standard model. It has by now been tested with 35 different datasets, successfully accounting for observations better than ΛCDM, often with likelihoods of ∼90 − 95% versus ∼5 − 10% (a recent comprehensive list of tests can be found in Melia 2020 and Melia 2025). Moreover, not only does Rh = ct account for the data better, it does so while adhering to all known fundamental physical constraints, including the zero active mass condition required for the validity of the FLRW ansatz (Melia 2022). One of its principal advantages is that it requires only one free parameter – the Hubble constant, H0 – while ΛCDM relies on the optimization of 11 − 12 different variables.

The energy conditions from general relativity have most famously been applied to the singularity theorems of Penrose (Penrose 1965) and Hawking (Hawking & Ellis 1973) and to the positive mass theorem (Schoen & Yau 1979). As we shall see, the energy condition most relevant to the present analysis is the SEC, which is formally derived as follows.

The SEC requires gravity to be attractive, i.e that matter gravitates towards matter. The inflaton field, for example, easily violates this condition because it produces antigravity. When invoking the inflationary concept, one must acknowledge the fact that, unlike every other known particle and field, it and a cosmological constant would be the only physical entities generating antigravity. The SEC can be represented mathematically via a convergence constraint on the Ricci tensor, Rμν, for a time-like observer with four velocity uμ (Martín-Moruno & Visser 2017),

Using Einstein’s field equations, this can be converted into a constraint on the stress-energy tensor itself,

where gμν represents the metric coefficients and T = Tμν gμν is the trace of Tμν. Using the perfect fluid approximation, with Tμν = diag (ρ, p, p, p), this condition leads to the following constraint(s) on the total pressure (p) and energy density (ρ) of the system (Melia 2023b):

In an FLRW universe, the SEC constrains the expansion to be non-accelerating. Hence, any acceleration in the standard model is a direct violation of this energy condition. One sometimes encounters the argument that such a violation by inflation thus invalidates the SEC. But assigning priority to inflation over this general relativistic constraint appears to be premature, given that the reality of inflation has never been established conclusively. In fact, modern high-precision measurements tend to disfavour inflation (see e.g. Ijjas et al. 2013; Liu & Melia 2020).

The fact that the SEC is violated both by an inflaton field and dark energy in the guise of a cosmological constant means that ΛCDM is inconsistent with classical general relativity at both high and low redshifts. For a more detailed explanation about the application of energy conditions to cosmology, see Melia (2023b), Chandak et al. (2025), and the comprehensive account in Melia (2025).

In this Letter we demonstrate the seriousness of this violation based on Eqs. (1) and (3) at z ≲ 2. But dark energy need not be a cosmological constant. In the Rh = ct model, it is dynamic, presumably an extension to the standard model of particle physics. This is why the cosmic expansion at all redshifts is fully consistent with the energy conditions in Rh = ct, as opposed to the tension created in the standard model.

3. Data and analysis

The Pantheon+ sample contains 1701 spectroscopically confirmed Type Ia SNe compiled from over 18 different surveys (see Table 1 of Scolnic et al. 2022). The data release was accompanied by a description of the empirical light-curve fits that were used to determine the peak magnitudes (x0), light-curve shapes (x1), colours (c), and the time of peak brightness (t0) of each SN. These can be used with a background cosmology to generate distance moduli using the modified Tripp relation (Tripp 1998),

where α, β, and MB are three model-dependent nuisance parameters to be optimized simultaneously with the background cosmology.

For each SN, the theoretical distance modulus is

where DL(z) is the model-dependent luminosity distance in terms of the redshift (z). In flat-ΛCDM,

assuming spatial flatness and a negligible radiation pressure. In Rh = ct, we have instead

We followed the procedure described in Wei et al. (2015), based on the method of maximum likelihood estimation, to optimize the nuisance parameters simultaneously with each cosmological model. However, H0 was simply set to 70 km s−1 Mpc−1 in both cases because its value is degenerate with MB. In other words, these two parameters cannot be optimized separately because they are directly coupled via Eqs. (4) and (6). Our optimized value for MB is thus consistent with this fiducial choice.

We maximized the likelihood function

where Γ = (μobs − μth), and C is the full (N × N) covariance matrix (with N the number of SNe) given by

Here, Cstat is the total statistical uncertainty recomputed for each cosmology and Csys is the covariance from systematic uncertainties provided as part of the data release. The statistical uncertainties were computed including contributions from (i) the uncertainties and covariances of the light-curve fit parameters, σl.c.; (ii) the redshift uncertainties that were propagated onto the distance modulus, σDL(zi); (iii) the uncertainties in peculiar velocities, σpec = 5σz, i/(zilog10); (iv) lensing effects, σlens = 0.055 × zi; and (v) an intrinsic dispersion, σint, that we optimized along with the nuisance parameters. As it turns out, however, its value has no significant effect on our results. Of these five, the first two are cosmology-dependent, and hence Cstat was computed simultaneously with the optimization

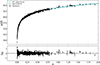

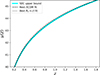

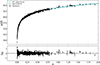

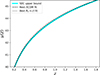

We used the Python Markov chain Monte Carlo module EMCEE (Foreman-Mackey et al. 2013) to generate the best fits in each model. The best-fit Hubble diagrams and their residuals are shown in Figs. 1 and 3, along with the upper bound to μth derived from the SEC. These bounds on the distance modulus due to the energy conditions were derived in Chandak et al. (2025). The optimized parameters are shown in Table 1, and the corner plots are presented in Fig. 2. The optimized fits and the SEC bound are presented again without the data and residuals for greater clarity in Fig. 4.

Optimized parameters and model selection.

|

Fig. 1. Distance modulus for the Type Ia SNe in the Rh = ct model. The predicted (dashed) curve is coincident with the SEC limit (blue curve), as highlighted in the plot without the data (Fig. 4). |

|

Fig. 2. 1D probability distributions and 2D regions with the 1 − 2σ contours for the parameters MB, α, and β in ΛCDM (blue) and in Rh = ct (red), corresponding to the fits in Figs. 1 and 3. Note that not all best-fit values are the same in the two models. |

|

Fig. 3. Distance modulus for the Type Ia SNe in flat-ΛCDM. The model prediction (dashed curve) violates the SEC limit (blue curve) in the redshift range z ⊂ (0.125, 2), as shown more clearly without the data in Fig. 4. |

|

Fig. 4. Optimized theoretical curves from Figs. 1 and 3, together with the SEC upper bound (blue), showing full compliance by Rh = ct (dotted) and a violation by flat-ΛCDM (dashed). |

4. Hubble diagrams and model selection

An inspection of Figs. 1 and 3, and a comparison of the error distributions in Fig. 2, demonstrates that the two models fit the data quite well. For example, the residuals in Figs. 1 and 3 are virtually indistinguishable, keeping in mind that the data are somewhat model-dependent since they rely in part on the optimization of Eq. (4). In other words, the data themselves are not identical in these two plots, but the residuals are very similar. The quality of these fits is also attested to by the optimized parameters shown in Table 1 and the side-by-side assessment of the error distributions in Fig. 2. Not only are the (common) parameters very similar in the two models, but their 1σ and 2σ errors imply a comparable quality of the fits.

However, while both Rh = ct and flat-ΛCDM satisfy the null, weak, and dominant energy conditions (not shown here, but see Chandak et al. 2025 for more details), only Rh = ct also satisfies the SEC. The standard model clearly does not. In ΛCDM, dark energy is typically represented as a cosmological constant, which is known to violate the SEC.

But these fits reveal much more than merely this difference with respect to the SEC. They show that the linear fit in Rh = ct is strongly favoured by the Type Ia SN data over flat-ΛCDM, as indicated by the Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz 1978). The ΔBIC ≈ 4 yields a probability of ∼89.8% for Rh = ct versus only ∼10.2% for flat-ΛCDM. The accelerated expansion predicted by ΛCDM is thus not favoured by Type Ia SNe. This outcome adds considerable weight to the already large body of evidence, drawn from much of the available data, that Rh = ct is favoured by the observations over the current standard model. These include measurements based on HII galaxies, cosmic chronometers, compact quasar cores, the angular diameter distance to lensed sources, the cosmic microwave background, and other such sources.

5. Conclusion

Type Ia SNe have been key in uncovering the expansion of the local Universe and the existence of dark energy. They were also used to highlight the presumed acceleration at z ≲ 0.7 in the context of flat-ΛCDM (Garnavich et al. 1998; Perlmutter & Aldering 1998; Riess et al. 1998; Schmidt et al. 1998). But our updated analysis demonstrates that – while dark energy unquestionably exists, though not as a cosmological constant – these data actually favour the linear expansion expected in Rh = ct. We have also affirmed the conclusion drawn in Chandak et al. (2025), based on the use of HII galaxies and cosmic chronometers, that an accelerated expansion in the local Universe violates the SEC, while the predicted Hubble diagram in Rh = ct is fully compliant with all the energy conditions from general relativity.

The most compelling statement we can make is that an expansion adhering to the energy conditions actually provides the better fit to the Type Ia SN data, strengthening both the theoretical basis for the energy conditions themselves and the interpretation of the cosmological observations. Indeed, it is the model that relies on speculative antigravity (i.e. ΛCDM) that is disfavoured by the data.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous referee for helpful comments. FM is also grateful to Amherst College for its support through a John Woodruff Simpson Lectureship. This work is partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant Nos. 12422307 and 12373053).

References

- Carniani, S., Hainline, K., D’Eugenio, F., et al. 2024, Nature, 633, 318 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chandak, N., Melia, F., & Wei, J. 2025, Eur. Phys. J. C, submitted [Google Scholar]

- DESI Collaboration (Adame, A. G., et al.) 2024, AJ, 168, 58 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. L., Bagley, M. B., Arrabal Haro, P., et al. 2022, ApJ, 940, L55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman-Mackey, D., Hogg, D. W., Lang, D., & Goodman, J. 2013, PASP, 125, 306 [Google Scholar]

- Garnavich, P. M., Jha, S., Challis, P., et al. 1998, ApJ, 509, 74 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guth, A. H. 1981, Phys. Rev. D, 23, 347 [Google Scholar]

- Hawking, S. W., & Ellis, G. F. R. 1973, The Large-scale Structure of Space-time (Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Ijjas, A., Steinhardt, P. J., & Loeb, A. 2013, Phys. Lett. B, 723, 261 [Google Scholar]

- Linde, A. D. 1982, Phys. Lett. B, 108, 389 [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., & Melia, F. 2020, Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. A, 476, 20200364 [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Moruno, P., & Visser, M. 2017, Fundam. Theories Phys., 189, 193 [Google Scholar]

- Mascia, S., Roberts-Borsani, G., Treu, T., et al. 2024, A&A, 690, A2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F. 2007, MNRAS, 382, 1917 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F. 2013, A&A, 553, A76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F. 2020, The Cosmic Spacetime (Oxford: Taylor and Francis) [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F. 2022, Mod. Phys. Lett. A, 37, 2250016 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F. 2023a, MNRAS, 521, L85 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F. 2023b, Annalen der Physik, 535, 2300157 [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F. 2024, Phys. Dark Universe, 46, 101587 [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F. 2025, The Physics of Cosmology (Amsterdam: Elsevier Press) [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F., & Shevchuk, A. S. H. 2012, MNRAS, 419, 2579 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Melia, F., Wei, J.-J., Maier, R. S., & Wu, X.-F. 2018, EPL (Europhysics Letters), 123, 59002 [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, R. 1965, Phys. Rev. Lett., 14, 57 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Perlmutter, S., Aldering, G., della Valle, M., et al. 1998, Nature, 391, 51 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Planck Collaboration VI. 2020, A&A, 641, A6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pontoppidan, K. M., Barrientes, J., Blome, C., et al. 2022, ApJ, 936, L14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Riess, A. G., Filippenko, A. V., Challis, P., et al. 1998, AJ, 116, 1009 [Google Scholar]

- Riess, A. G., Yuan, W., Macri, L. M., et al. 2022, ApJ, 934, L7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J., Alcaniz, J. S., Pires, N., & Rebouças, M. J. 2007, Phys. Rev. D, 75, 083523 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, B. P., Suntzeff, N. B., Phillips, M. M., et al. 1998, ApJ, 507, 46 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen, R., & Yau, S.-T. 1979, Phys. Rev. Lett., 43, 1457 [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, G. 1978, Ann. Stat., 6, 461 [Google Scholar]

- Scolnic, D., Brout, D., Carr, A., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, 113 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Starobinskiǐ, A. A. 1979, Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett., 30, 682 [Google Scholar]

- Tripp, R. 1998, A&A, 331, 815 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.-J., Wu, X.-F., Melia, F., & Maier, R. S. 2015, AJ, 149, 102 [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Distance modulus for the Type Ia SNe in the Rh = ct model. The predicted (dashed) curve is coincident with the SEC limit (blue curve), as highlighted in the plot without the data (Fig. 4). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. 1D probability distributions and 2D regions with the 1 − 2σ contours for the parameters MB, α, and β in ΛCDM (blue) and in Rh = ct (red), corresponding to the fits in Figs. 1 and 3. Note that not all best-fit values are the same in the two models. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Distance modulus for the Type Ia SNe in flat-ΛCDM. The model prediction (dashed curve) violates the SEC limit (blue curve) in the redshift range z ⊂ (0.125, 2), as shown more clearly without the data in Fig. 4. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Optimized theoretical curves from Figs. 1 and 3, together with the SEC upper bound (blue), showing full compliance by Rh = ct (dotted) and a violation by flat-ΛCDM (dashed). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$$ \begin{aligned} \mu _{\rm {th}}(z) = 5\log \bigg [\frac{D_L (z)}{Mpc} \bigg ] + 25, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa58990-26/aa58990-26-eq10.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{(2\pi )^N \det C}} \times \exp \bigg [{-\frac{1}{2} \Gamma ^T C^{-1} \Gamma }\bigg ], \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa58990-26/aa58990-26-eq13.gif)