| Issue |

A&A

Volume 702, October 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A115 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554568 | |

| Published online | 14 October 2025 | |

Detectability of compact intermediate-mass black hole binaries as low-frequency gravitational wave sources: The influence of dynamical friction of dark matter

1

National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 20A Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing, 100101

People’s Republic of China

2

School of Astronomy and Space Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, 100049

People’s Republic of China

3

School of Science, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, 266525

People’s Republic of China

4

School of Physics and Electrical Information, Shangqiu Normal University, Shangqiu, 476000

People’s Republic of China

⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

17

March

2025

Accepted:

1

August

2025

Context. The spin of a black hole (BH) can significantly alter the density of dark matter (DM) in its vicinity, creating a density mini-spike. The dynamical friction (DF) between DM and the companion star of a BH can provide an efficient loss of angular momentum, driving the BH-main-sequence (MS) star binary to evolve toward a compact orbital system.

Aims. We investigate the influence of DF from DM on the detectability of intermediate-mass black hole (IMBH)-MS binaries as low-frequency gravitational-wave (GW) sources.

Methods. Taking into account DF from DM, we employed the detailed binary evolution code MESA to model the evolution of a large number of IMBH-MS binaries.

Results. Our simulation shows that DF from DM can drive IMBH-MS binaries to evolve toward low-frequency GW sources when the donor-star mass is low, the spike index is high, or the initial orbital period is short. When the spike index is γ = 1.60, IMBH-MS binaries with donor-star masses of 1.0 − 3.4 M⊙ and initial orbital periods of 0.65 − 16.82 days can evolve toward visible LISA sources within a distance of 10 kpc.

Conclusions. The DF from DM can enlarge the initial parameter space and prolong the bifurcation periods. In the low-frequency GW source stage, the X-ray luminosities of IMBH X-ray binaries are ∼1035 − 1036 erg s−1, making them ideal multi-messenger objects.

Key words: gravitational waves / stars: black holes / stars: evolution / dark matter

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Stellar-mass black holes (BHs with masses of ∼10 − 100 M⊙) are the evolutionary products of massive stars. Supermassive BHs (with a mass of ∼106 − 109 M⊙) are generally located at the centers of galaxies and are thought to be the energetic central engines of active galactic nuclei. In the mass gap (∼102 − 105 M⊙) between stellar-mass BHs and supermassive BHs, a transitional population called intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs) may exist. In theory, IMBHs may form through direct collapse from very massive Population III stars (Madau & Rees 2001), runaway stellar collisions in dense star clusters (Portegies Zwart & McMillan 2002; Portegies Zwart et al. 2004a), gradual growth via stellar-mass BH mergers (O’Leary et al. 2006), and accretion onto preexisting seed BHs at cluster centers (Vesperini et al. 2010).

Intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs) have been invoked to explain ultraluminous X-ray sources (ULXs) with isotropic X-ray luminosities exceeding 1039 erg s−1 (Colbert & Mushotzky 1999; Feng & Soria 2011). Some studies have proposed that IMBHs power the ULX source in MGG-11 (Kaaret et al. 2001) and the hyperluminous X-ray source (LX > 1041 erg s−1) M82 X-1 in the starburst galaxy M82 (Pasham et al. 2014). The cool thermal emission components identified in the X-ray spectral analysis of some ULXs appear to be well interpreted by the IMBH accretion disk models (Miller et al. 2004). The detection of transient radio emission from the candidate IMBH ESO 243-49 HLX-1 constrained the BH mass to 9 × 103 − 9 × 104 M⊙ (Webb et al. 2012), which lies within the expected IMBH mass range.

To produce a stable, strong X-ray luminosity in a ULX, an IMBH should accrete material from a tidally captured or exchange-encountered main-sequence (MS) star via Roche lobe overflow (RLOF). Hopman et al. (2004) argued that an IMBH in the center of MGG-11 can capture a passing MS star or giant in a tidal event and produce a ULX source-like luminosity through RLOF of the donor star after orbital circularization on a timescale longer than 107 yr. Detailed stellar evolution simulations have indicated that the accretion of an IMBH from its companion star can power X-ray luminosities exceeding 1040 erg s−1 on timescales of several Myr (Portegies Zwart et al. 2004a; Li 2004). Compared with stellar-mass BHs, the higher BH masses and wider orbits in IMBH X-ray binaries tend to result in larger accretion disks and lower disk temperatures, making them most likely to appear as transient sources due to thermal-viscous instability (Kalogera et al. 2004). Based on 30 000 binary evolution models of IMBH X-ray binaries, Madhusudhan et al. (2006) found that only systems with a donor-star mass greater than 8 M⊙ and initial orbital separations of about 6 − 30 times the radii of donor stars can appear as active ULXs with luminosities greater than 1040 erg s−1. Using N-body simulations of young clusters such as MGG-11 of M82, Baumgardt et al. (2006) reported that IMBHs have a high probability of capturing stars through tidal energy dissipation and subsequently evolving into the IMBH X-ray binaries described above.

At cosmological distances, a broad population of IMBHs may be revealed by multiband observations with spaceborne and ground-based gravitational wave (GW) detectors (Jani et al. 2020). Observationally, IMBH X-ray binaries can appear not only as ULXs but also as low-frequency GW sources detected by spaceborne GW detectors such as LISA (Amaro-Seoane et al. 2023), TianQin (Luo et al. 2016), and Taiji (Ruan et al. 2020). If the initial orbital periods are shorter than the bifurcation periods, IMBH binaries consisting of an IMBH and an MS companion star could evolve toward IMBH X-ray binaries with compact orbits, which can be detected by spaceborne GW detectors (Portegies Zwart et al. 2004b; Chen 2020). However, the detection of compact IMBH X-ray binaries by LISA is difficult, as their maximum number in the Galaxy is expected to be fewer than ten during a four-year mission duration (Chen 2020). In fact, the formation of compact IMBH X-ray binaries strongly depends on the loss mechanism of angular momentum. If an efficient loss mechanism for angular momentum exists, the number of compact IMBH X-ray binaries detected as low-frequency GW sources should significantly increase.

The adiabatic growth of a supermassive BH at the center of a galaxy by standard accretion of dust and gases could alter the distribution of dark matter (DM) and create a high-density cusp, i.e., a DM spike (Gondolo & Silk 1999; Gnedin & Primack 2004; Merritt 2004; Sadeghian et al. 2013). Rotation significantly increases the density of DM close to the BH, resulting in the formation of mini-spikes around a spinning IMBH (Ferrer et al. 2017). When the donor star of an IMBH is orbiting within a collisionless DM background, the gravitational interaction between the star and the DM will slow the star, resulting in the effect of dynamical friction (DF). The mini-spikes produce an efficient DF effect, which then influences the orbital evolution of IMBH binaries. Eda et al. (2015) found that the DF from DM can significantly influence the GW waveform of extreme mass-ratio inspirals. Compared to binary systems driven purely by GW, DM from DF can lead to different evolutionary tracks, depending on local DM density and orbital separation (Gómez & Rueda 2017). Taking into account the DF from DM, the merger timescale of intermediate or extreme mass ratio inspirals is reduced by 2 − 3 orders of magnitude (Yue et al. 2019). Recently, it has been proposed that the abnormally rapid orbital decay of two BH low mass X-ray binaries, A0620-00 and XTE J1118 + 480, was caused by DF from DM with specific spike indices γ, providing indirect evidence of DM spikes around stellar-mass BHs (Chan & Lee 2023). These studies imply that DF from DM drives BH X-ray binaries to evolve toward binary systems with compact orbits, playing an important role in their orbital evolution.

Until now, no detailed binary evolution model of IMBH binaries including DF from DM has been available in the literature. In this work, we investigate the detectability of IMBH binaries as low-frequency GW sources when DF from DM is included. We describe the stellar evolution code and input physics in Section 2. The detailed simulated results are presented in Section 3. Finally, we provide discussion and conclusions in Sections 4 and 5, respectively.

2. Stellar evolution code and input physics

2.1. Stellar evolution code

To investigate whether some IMBH binaries can evolve toward low-frequency GW sources, we used an updated binary version of the Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics code (MESA, r12115, Paxton et al. 2011, 2013, 2015, 2018, 2019) to calculate the evolution of IMBH binaries consisting of an IMBH and a MS companion star. The BH was assumed to be a point mass with a mass of MBH = 1000 M⊙, and the companion star is considered to be a Population I star with a solar composition, in which X = 0.70, Y = 0.28, and Z = 0.02. The MESA code simulates the nuclear synthesis of the MS star and the orbital evolution of the system. Tidal interactions acting on an MS star near RLOF can circularize the orbit on a timescale of ∼ 104 yr (Claret & Cunha 1997), which is much shorter than the evolutionary timescale before RLOF. Furthermore, mass transfer also circularizes the orbit, with residual eccentricity on a timescale much shorter than the mass transfer timescale (Sepinsky et al. 2010). Therefore, the orbits of all IMBH binaries are thought to be circular throughout their evolution.

If the donor star orbits within the tidal radius of the IMBH, the star may be destroyed in a tidal disruption event (TDE). The tidal radius of an IMBH is (Hopman et al. 2004)

where Md and Rd are the mass and radius of the donor star, respectively. Once the donor star spirals within the BH’s tidal radius, the calculation is stopped because the X-ray binary phase is considered complete. Otherwise, the detailed stellar evolution model in MESA continues running until the time step falls below a minimum limit or the stellar age exceeds the Hubble time (14 Gyr).

Once nuclear evolution initiates additional carbon-oxygen burning during and after helium burning, Type 2 opacities are adopted. We used a mixing length parameter α = l/Hp = 2, where l and Hp are the mixing length and the height of the local pressure scale of the MS companion star, respectively. In the numerical calculation, the time step options mesh−delta−coeff = 1.0, and varcontrol−target = 10−4 were used.

During mass transfer, the mass growth rate of the IMBH is limited by the Eddington accretion rate. Excess material is assumed to be ejected as isotropic winds near the IMBH, carrying away its specific orbital angular momentum. Our calculations indicate that a super-Eddington mass transfer is impossible for a low-mass or intermediate-mass donor star. Furthermore, we considered three other mechanisms of angular momentum loss, including gravitational radiation (GR), magnetic braking, and DF from DM (see also Section 2.2). If the donor star develops a convective envelope and has a radiative core, the standard magnetic braking model with γmb = 3 given by Rappaport et al. (1983) was adopted.

2.2. Dynamical friction from dark matter

Similarly to supermassive BHs, the density distribution of DM around an IMBH is described as a piecewise function as follows (Sadeghian et al. 2013; Lacroix 2018):

where r is the radial distance from the BH, Rsh = 2GMBH/c2 (where G is the gravitational constant and c is the speed of light in vacuo) is the Schwarzschild radius, rsp denotes the DM spike radius. Beyond the spike radius, the DM density around the BH follows a constant distribution with density ρ0, which may vary across different Galactic positions. However, this variation is trivial outside the Galactic center (McMillan 2017). In the calculation, the density of the DM background is taken as ρ0 = ρ⊙ (Lacroix 2018), where ρ⊙ = 0.33 ± 0.03 GeV cm−3 is the DM density near the Sun. We adopt the standard assumption rsp = 0.2rin (Fields et al. 2014; Eda et al. 2015), where rin is the influence radius of a BH. The total mass of DM inside the influence radius is 2MBH (Merritt 2004), expressed as

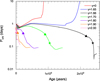

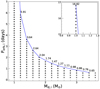

Figure 1 shows the DM density profiles around an IMBH of 1000 M⊙. The mini-spike around an IMBH leads to a distribution of high DM density, where a higher spike index tends to produce a higher DM density in the vicinity of the IMBH. For a system consisting of a 1000 M⊙ IMBH and a 1 M⊙ MS star in a 1.0-day orbit, the DM densities with γ = 1.0 − 2.0 at the position of the donor star are in the range of ∼106 − 1013 GeV cm−3, i.e., 6 − 13 orders of magnitude higher than ρ0.

|

Fig. 1. Dark matter density profiles with different spike indices around an IMBH of MBH = 1000 M⊙. The vertical dashed orange line indicates a radius of r = 2.93 × 1012 cm, which is the orbital separation of a system consisting of a 1000 M⊙ IMBH and a 1 M⊙ MS star in a 1.0-day orbit. |

The orbital energy dissipation rate due to DF from DM is given by (Yue et al. 2019)

where μ = MBHMd/(MBH + Md) is the reduced mass of the system, ξ(σ) is a numerical factor determined by the distribution function and the velocity dispersion of DM,  is the Coulomb logarithm (Kavanagh et al. 2020), and v is the orbital velocity of the companion star.

is the Coulomb logarithm (Kavanagh et al. 2020), and v is the orbital velocity of the companion star.

According to  , where Ω is the orbital angular velocity, the loss rate of the orbital angular momentum due to DF from DM can be written as (Qin & Chen 2024)

, where Ω is the orbital angular velocity, the loss rate of the orbital angular momentum due to DF from DM can be written as (Qin & Chen 2024)

where q = Md/MBH, Porb, and a are the mass ratio, orbital period, and orbital separation of IMBH binaries, respectively.

2.3. Detectability of IMBH binaries as low-frequency GW sources

Once IMBH binaries evolve into systems with narrow orbits, they produce low-frequency GW signals with frequency fgw = 2/Porb, potentially detectable by spaceborne GW detectors such as LISA. The maximum GW frequency derivative is  (see also Figure 9; for semi-detached systems, fgw,max ∼ 10−14 Hz s−1). Consequently, the frequency change is fgw,max ∼ 10−18 Hz s−1 over a LISA mission duration of Δ fgw ∼10−6 Hz. Therefore, these low-frequency GW sources can be considered to be in circular orbits with monotonically varying frequency. Considering an average orbital orientation and polarization for a binary GW source, the GW amplitude at a distance of d is (Evans et al. 1987)

(see also Figure 9; for semi-detached systems, fgw,max ∼ 10−14 Hz s−1). Consequently, the frequency change is fgw,max ∼ 10−18 Hz s−1 over a LISA mission duration of Δ fgw ∼10−6 Hz. Therefore, these low-frequency GW sources can be considered to be in circular orbits with monotonically varying frequency. Considering an average orbital orientation and polarization for a binary GW source, the GW amplitude at a distance of d is (Evans et al. 1987)

where ℳ = (MBHMd)3/5/(MBH + Md)1/5 is the chirp mass. By integrating the signal power over the mission duration, the characteristic strain can be derived as T = 4 yr (Finn & Thorne 2000; Tauris 2018). Therefore, the characteristic strain of low-frequency GW signals produced by IMBH binaries is given by (Chen 2020)

For simplicity, IMBH binaries are considered low-frequency GW sources detectable by LISA if their calculated characteristic strain exceeds the LISA sensitivity curve from analytic estimations (Robson et al. 2019). We emphasize that equation (7) does not represent the characteristic strain in the frequency domain. However, the calculated evolutionary track in the characteristic strain versus instantaneous GW frequency diagram provides an order-of-magnitude estimate of the expected strain during the evolution of IMBH binaries.

3. Simulated results

Whether IMBH-MS binaries can evolve toward low-frequency GW sources strongly depends on the rate of angular momentum loss. According to Equation (5), the loss rate of angular momentum is closely related to three parameters: Md, ρDM, and Porb. We first investigate the influence of these three parameters on the evolution of IMBH-MS binaries.

3.1. Influence of donor-star masses

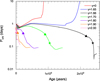

Figure 2 shows the evolution of four IMBH-MS binaries with Md, i = 1.0 − 2.8 M⊙, Porb,i = 1 day, and γ = 1.6. For a relatively small spike index of 1.6, systems with Md, i ≥ 2.8 M⊙ eventually evolve into wide-orbit systems. In contrast, binaries with a low donor star mass (Md, i ≤ 2.7 M⊙) evolve into compact X-ray binaries, which become visible to LISA as low-frequency GW sources on timescales of 400 − 700 Myr. When these sources are visible to LISA at a distance of 1 kpc, the donor-star masses decrease to Md ∼ 0.7 − 1.0 M⊙, and the orbital periods decrease to ≲0.4 days, corresponding to GW frequencies ≳0.06 mHz.

The total orbital angular momentum of an IMBH-MS binary is J = MBHMd/(MBH + Md)a2Ω. Ignoring the mass loss during the mass transfer, i.e., ṀBH = 0, from Kepler’s third law (G(MBH + Md)/a3 = 4π2/Porb2) we derive

where q = Md/MBH is the mass ratio of the binary. Because Ṁd < 0 and q < 1, the second term on the right-hand side of equation (8) is positive. Therefore, mass transfer causes an orbital expansion effect when the mass is transferred from the less massive donor star to the more massive BH. However, the loss of angular momentum leads to an orbital decay effect (see also the first term on the right-hand side of equation (8)). Consequently, the evolutionary outcome of an IMBH binary strongly depends on the competition between these two effects. A smaller spike index directly leads to a lower DM density, which then indirectly produces a lower rate of angular momentum loss due to DF from DM. Therefore, a small spike index cannot drive IMBH binaries with massive donor stars to evolve toward low-frequency GW sources. In Figure 2, the early evolution of three systems with Md, i = 1.0, 2.0, and 2.7 M⊙ is dominated by DF from DM. They undergo rapid orbital shrinkage and evolve into compact orbit binaries. However, the orbital expansion effect in the system with Md, i = 2.8 M⊙ gradually overcomes the orbital decay effect caused by DF from DM, driving it to evolve toward a wide-orbit system.

|

Fig. 2. Evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with an initial orbital period of Porb,i = 1.0 day and varying initial donor-star masses. Top panel: Orbital period vs. stellar age. Bottom panel: Orbital period vs. donor-star mass for γ = 1.60. Open circles, solid triangles, and solid stars indicate the onset of RLOF and the points at which IMBH binaries become visible by LISA at distances of 1 kpc and 10 kpc, respectively. Sources marked by open triangles become undetectable by LISA at 1 kpc. |

In Figure 3, we adopt a large spike index (γ = 1.8) to investigate the evolution of the IMBH-MS binaries with Md, i = 3.0 − 6.0 M⊙ and Porb,i = 1 day. Their evolutionary tendency is very similar to that in Figure 2, in which a lower initial donor-star mass tends to result in the formation of more compact X-ray binaries and low-frequency GW sources. For γ = 1.80, the higher DM density produces a higher rate of angular momentum loss, and hence DF from DM can dominate the evolution of some IMBH binaries with massive donor stars. Therefore, two systems with Md, i = 5.5 and 3.0 M⊙ evolve into compact IMBH X-ray binaries and low-frequency GW sources. When these IMBH X-ray binaries appear as low-frequency GW sources at a distance of 1 kpc, the donor-star masses are distributed in a range of ∼0.4 − 1.0 M⊙ and the orbital periods are ≲0.4 days. Three IMBH binaries with relatively high donor-star mass (Md, i = 5.6, 5.7, and 6.0 M⊙) initially evolve into systems with wide orbits because of the strong orbital expansion effect caused by mass transfer. However, the two systems with Md, i = 5.7 and 6.0 M⊙ would decouple their Roche lobes and become detached systems consisting of an IMBH and a white dwarf (WD) within a Hubble timescale. Subsequently, GR drives these two systems to experience a rapid orbital shrinkage and eventually evolve into low-frequency GW sources detectable by LISA at distances of 1 kpc and 10 kpc, respectively.

|

Fig. 3. Evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with Porb,i = 1.0 day and varying donor-star masses. Top panel: Orbital period vs. stellar age. Bottom panel: Orbital period vs. donor-star mass for γ = 1.80. Symbols are the same as in Figure 2. |

To test whether these IMBH-MS binaries can evolve into low-frequency GW sources, Figure 4 presents the evolutionary tracks of the systems in Figures 1 and 2 in the characteristic strain versus GW frequency diagram. In the top panel, three systems with Md, i = 1.0, 2.0, and 2.7 M⊙ and Porb,i = 1.0 day evolve to penetrate the sensitivity curves of LISA and Taiji at a GW frequency of ∼0.1 mHz, becoming visible sources to both detectors when d = 10 kpc. Because of a short arm length, it is difficult for TianQin to detect GW signals from these three systems. In the bottom panel, four systems with massive donor stars evolve into visible LISA and Taiji sources (TianQin can detect only three of these, with the Md, i = 3.0 M⊙ system remaining undetectable at a distance of 10 kpc). The system with Md, i = 5.6 M⊙ does not evolve into a visible source for any of the detectors. During the low-frequency GW stage, the systems with Md, i = 5.7 and 6.0 M⊙ have the same slope as Δ(log hc)/Δ(log fgw) = 7/6. This is because these two systems have evolved into detached IMBH-WD binaries, where  holds for a constant chirp mass (see also Equation (7)).

holds for a constant chirp mass (see also Equation (7)).

|

Fig. 4. Evolution of IMBH binaries with Porb,i = 1 day and varying donor-star masses. Top panel: Characteristic strain vs. GW frequency diagram when γ = 1.60; bottom panel: γ = 1.80. The blue curve shows the LISA sensitivity based on a numerical calculation for a mission duration of four years. The red and green curves correspond to the sensitivity curves of TianQin (Wang et al. 2019) and Taiji (Ruan et al. 2020), respectively. |

Following Equation (26) of Robson et al. (2019), the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of typical galactic binaries can be written as  , where Sn(f) is the noise spectral density of LISA. We calculated the S/N for seven detectable systems shown in Figure 4. In the top panel, three systems with Md, i = 1.0, 2.0, and 2.7 M⊙ have maximum S/N of ∼1, ∼1, and ∼2 when d = 10 kpc, respectively. If the detected distance decreases to 1 kpc, the maximum S/N of these three systems are ∼9, ∼10, and ∼20, respectively. Therefore, these three systems are challenging for LISA to detect at 10 kpc, but can be detected at a close distance of 1 kpc. In the bottom panel, the maximum S/N of four systems with Md, i = 3.0, 5.5, 5.6 and 5.7 M⊙ are ∼1 (this system cannot be detected by LISA), ∼5, ∼1.2 × 104, and ∼1.9 × 104 when d = 10 kpc, respectively.

, where Sn(f) is the noise spectral density of LISA. We calculated the S/N for seven detectable systems shown in Figure 4. In the top panel, three systems with Md, i = 1.0, 2.0, and 2.7 M⊙ have maximum S/N of ∼1, ∼1, and ∼2 when d = 10 kpc, respectively. If the detected distance decreases to 1 kpc, the maximum S/N of these three systems are ∼9, ∼10, and ∼20, respectively. Therefore, these three systems are challenging for LISA to detect at 10 kpc, but can be detected at a close distance of 1 kpc. In the bottom panel, the maximum S/N of four systems with Md, i = 3.0, 5.5, 5.6 and 5.7 M⊙ are ∼1 (this system cannot be detected by LISA), ∼5, ∼1.2 × 104, and ∼1.9 × 104 when d = 10 kpc, respectively.

3.2. Influence of spike indices

According to equations (2) and (5), a higher spike index results in a higher DM density and a higher loss rate of angular momentum due to DF from DM. Therefore, the spike index significantly influences the evolutionary fates of IMBH-MS binaries. Figure 5 illustrates the evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with Md, i = 3.0 M⊙ and Porb,i = 1.0 day in the orbital period versus stellar age diagram, considering various spike indices. There exists a critical spike index γcr = 1.66, below which the IMBH-MS binaries cannot evolve into low-frequency GW sources. This critical spike index is slightly higher than the corresponding value (γcr = 1.58) in stellar-mass BH X-ray binaries (Qin & Chen 2024). Moreover, a higher spike index naturally results in a higher orbital period derivative (see also the slopes of the evolutionary curves) and a shorter evolutionary timescale. When five IMBH X-ray binaries are visible for LISA within a distance of 1 kpc, their ages are 2.2, 0.9, 0.25, 0.1, and 0.01 Gyr for γ = 1.66, 1.7, 1.8, 1.9, and 2.0, respectively. Assuming standard magnetic braking (i.e., γ = 0), IMBH-MS binaries with intermediate-mass donors cannot evolve into a compact orbit system.

|

Fig. 5. Evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with Md, i = 3.0 M⊙, Porb,i = 1.0 day, and varying spike indices shown in the orbital period vs. stellar age diagram. Symbols are the same as in Figure 2. |

Among spike indices exceeding γcr, smaller values tend to form an IMBH X-ray binary with a shorter minimum orbital period. This is because a smaller spike index leads to a lower DM density at the position of the donor star, inducing a lower loss rate of angular momentum due to DF from DM and a longer evolutionary timescale. Consequently, a longer evolutionary timescale makes the donor star develop a more massive helium core, yielding a more compact donor star and shorter orbital period (see also Qin & Chen 2024).

3.3. Influence of initial orbital periods

For γ = 1.60 and Md, i = 1.2 M⊙, Figure 6 summarizes the evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with varying initial orbital periods, shown in the orbital period versus stellar age and the orbital period versus donor-star mass diagrams. A bifurcation period of Porb, i = 5.93 days exists, beyond which IMBH-MS binaries cannot evolve toward compact orbit systems within a Hubble time. The bifurcation period is defined as the longest initial orbital period in which binary systems consisting of a compact object and an MS donor star can evolve into ultracompact X-ray binaries within a Hubble time (van der Sluys et al. 2005a,b). In principle, the mass transfer from the less massive donor star to the more massive IMBH causes an orbital expansion effect, whereas the angular momentum loss due to DF from DM results in an orbital decay effect. Whether IMBH-MS binaries can evolve toward ultracompact orbit systems depends on the competition between these two effects. Consequently, the bifurcation period is closely related to the angular momentum loss mechanisms, and a more efficient mechanism of angular momentum loss tends to lead to a longer bifurcation period. When magnetic braking is a dominant mechanism of angular momentum loss, the bifurcation period of an IMBH binary consisting of a 1000 M⊙ IMBH and a 1.2 M⊙ MS donor star is between 1.9 and 3.2 days, as shown in Figure 5 of Chen (2020); however, our simulated bifurcation period is 5.93 days for the same system. This discrepancy arises from different rates for extracting orbital angular momentum, in which the loss rate of angular momentum due to DF from DM is much higher than that driven by the standard magnetic braking law in Chen (2020).

|

Fig. 6. Evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with Md, i = 1.2 M⊙, γ = 1.60, and varying initial orbital periods. Top panel: Orbital period vs. stellar age. Bottom panel: Orbital period vs. donor-star mass. Symbols are the same as in Figure 2. |

In Figure 6, the IMBH-MS binaries with initial orbital periods shorter than the bifurcation period evolve into low-frequency GW sources. When the orbital periods decrease to ∼0.2 days and ∼0.1 days, these systems can be detected by LISA at distances of 1 kpc and 10 kpc, respectively. The low-frequency GW sources evolving from IMBH-MS binaries can be divided into two populations: semidetached systems and detached systems. In the low-frequency GW stage, two compact IMBH X-ray binaries with initial orbital periods of 5.7 and 5.0 days remain semidetached systems with ongoing mass transfer, and the systems also appear as X-ray sources. The system with an initial period of 5.93 days first evolves into a detached binary consisting of an IMBH and a pre-WD (with a mass of ∼0.2 M⊙) in a relatively wide orbit with an orbital period of ∼1 day. Subsequently, GR drives this detached system to evolve toward low-frequency GW sources after the pre-WD evolves into a WD through a contraction and cooling phase.

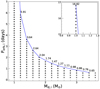

3.4. Parameter space of IMBH-MS binaries forming low-frequency GW sources

Using a fixed spike index of γ = 1.60, Figure 7 summarizes the evolutionary fates of the IMBH-MS binaries with varying initial orbital periods and initial donor-star masses. The IMBH binaries with Md, i = 1.0 − 3.4 M⊙ and Porb, i = 0.65 − 16.82 days are potential visible LISA sources at a distance of d = 10 kpc. This parameter space is much larger than that predicted by the standard magnetic braking law (see also Figure 5 in Chen 2020). The upper boundary of the initial periods corresponds to the bifurcation periods. As the donor-star mass grows, the bifurcation period decreases. This is because a higher donor-star mass produces a higher mass-transfer rate, resulting in a stronger orbital expansion effect. Similarly, IMBH-MS binaries with higher donor-star mass struggle to evolve toward compact orbit systems, yielding the right boundary. Binaries with initial orbital periods below the lower boundary cannot evolve into low-frequency GW sources within a Hubble time, or they fill their Roche lobe at the beginning of binary evolution. The left boundary originates from the law that a lower donor-star mass requires a longer evolutionary timescale, and hence, those systems cannot evolve into compact orbit systems within a Hubble timescale. When Md, i = 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 M⊙, the bifurcation periods are 16.82, 1.74, and 0.86 days, respectively. Our bifurcation periods are slightly longer than those reported in Chen (2020), which are 3.2, 1.4, and 0.7 days, respectively. Consistent with the previous subsection, this implies that the loss rate of angular momentum due to DF from DM exceeds that from the standard MB law.

|

Fig. 7. Parameter space distribution of IMBH-MS binaries that can evolve into low-frequency GW sources detectable by LISA, shown in the initial orbital period vs. initial donor-star mass diagram. A constant DM spike index of γ = 1.60 is adopted. The solid curve denotes the bifurcation periods of IMBH binaries with varying donor-star masses. The solid circles and stars represent IMBH binaries that will evolve into low-frequency GW sources detectable by LISA within distances of d = 1 and 10 kpc, respectively. Crosses indicate binaries for which RLOF already occurs at the beginning of binary evolution. When the initial periods are above the bifurcation period, those systems will evolve into IMBH binaries with long periods. |

4. Discussion

4.1. Evolution of companion stars in HR diagram

To better understand the properties and final evolutionary fates of companion stars, Figure 8 displays the evolution of several IMBH-MS binaries within the Hertzsprung–Russell (HR) diagram. In the top panel, companion stars with Md, i = 6.0, 5.7, and 5.6 M⊙ experience four, two, and one hydrogen shell flash, respectively. The pre-WD masses for these three companion stars lie within 0.2 − 0.32 M⊙ (see also Figure 3). These values are consistent with the pre-WD mass range (0.212 − 0.319 M⊙) for hydrogen shell flashes in a basic model with Z = 0.02 (see also table 2 of Istrate et al. 2016). When two systems with Md, i = 6.0 and 5.7 M⊙ evolve into low-frequency GW sources, their luminosities and effective temperatures are L ∼ 10−4 − 10−3 L⊙ and Teff ∼ 5600−7000 K, respectively, implying that these donor stars have already evolved into WDs. Conversely, the luminosities and effective temperatures of two donor stars with Md, i = 3.0 and 5.5 M⊙ are L ∼ 0.1 − 1 L⊙ and Teff ∼ 5600 K in the low-frequency GW source stage, i.e. they are still in the MS stage experiencing a central hydrogen burning. Their central hydrogen abundances are 0.6 and 0.06, respectively.

|

Fig. 8. Evolution of the companion stars in the HR diagram for IMBH-MS binaries shown in Figures 2 (top panel) and 5 (bottom panel). The open circles, solid triangles, and solid stars indicate the beginning of RLOF and the points at which IMBH binaries become detectable by LISA at distances of 1 kpc and 10 kpc, respectively. |

The bottom panel shows that only one system with Porb, i = 6.0 days undergoes two hydrogen shell flashes. Two systems with Porb, i = 5.93 and 5.94 days have already evolved into WDs with masses slightly below 0.2 M⊙ (see also Figure 5). These two masses are not in the pre-WD mass range (0.212 − 0.319 M⊙) associated with hydrogen shell flashes (Istrate et al. 2016), explaining the absence of such flashes. The luminosities and effective temperatures of two donor stars with Porb, i = 5.0 and 5.7 days are L ∼ (10−3 − 1) L⊙ and Teff ∼5000 K during the low-frequency GW source stage. Therefore, these stars are also in the MS stage, similar to the two systems with Md, i = 3.0 and 5.5 M⊙ shown in the top panel.

4.2. X-ray luminosity

When IMBH binaries appear as low-frequency GW sources, they may also be detected as strong X-ray sources. During BH accretion, there exists a high-soft state dominated by a thermal soft spectrum and a low-hard state characterized by a nonthermal hard power-law spectrum (Nowak 1995). The transition between these two states was believed to take place at a critical accretion rate, Mcrit (Körding et al. 2002). For a high accretion rate Ṁacc > Ṁcrit, the X-ray luminosity of the accretion disk is expected to increase with Ṁacc, as in a standard accretion disk. In contrast, X-ray luminosity is proportional to  due to an optically thin, advection-dominated accretion flow (Narayan & Yi 1995). Consequently, the X-ray luminosity is expressed as (Körding et al. 2002)

due to an optically thin, advection-dominated accretion flow (Narayan & Yi 1995). Consequently, the X-ray luminosity is expressed as (Körding et al. 2002)

where ϵ = 0.1 is the radiative efficiency of the accretion disk. Following Hopman et al. (2004), we adopt Ṁcrit = 10−7 M⊙ yr−1 for an IMBH with a mass of 1000 M⊙.

Figure 9 illustrates the evolution of X-ray luminosities of IMBH X-ray binaries presented in Figures 1 and 2. Before these binaries evolve into low-frequency GW sources, their X-ray luminosities exhibit a relatively low state. Once they appear as low-frequency GW sources, the X-ray luminosities rapidly increase due to rapid orbital decay. For IMBH X-ray binaries visible to LISA within distances of 1 and 10 kpc, the X-ray luminosities are ∼ 1035−1036 erg s−1. Nonfocusing X-ray telescopes have a detection threshold of ∼ 10−11 erg s−1 cm−2 for X-ray flux (Sen et al. 2021), corresponding to minimum detectable luminosities of ∼1033 and ∼ 1035 erg s−1 for distances of 1 and 10 kpc, respectively. These values are consistent with our simulated X-ray luminosities. Therefore, compact IMBH X-ray binaries are ideal multi-messenger sources observable in both the low-frequency GW band and the electromagnetic wave band. X-ray observations of these low-frequency GW sources would provide relatively accurate positions and distances. However, our simulations indicate that these low-frequency sources cannot appear as ultraluminous X-ray sources with Lx > 1039 erg s−1.

|

Fig. 9. Evolution of X-ray luminosity for IMBH X-ray binaries with initial orbital period Porb,i = 1.0 day and varying initial donor-star masses when γ = 1.60 (top panel; same as Figure 2) and γ = 1.80 (bottom panel; same as Figure 3). The solid triangles and solid stars denote the onset times at which IMBH X-ray binaries become detectable by LISA within distances of 1 and 10 kpc, respectively. The first solid triangle in the bottom panel marks the evolutionary curve for Md, i = 3.0 M⊙. |

4.3. Detectability of chirp signals

If the GW frequency derivative (ḟgw) of a low-frequency GW source can be measured, its chirp mass can be calculated as

Therefore, accurate measurement of ḟgw is crucial to determining the chirp mass. The detection limitation of the GW-frequency derivative for LISA is given by (Takahashi & Seto 2002)

where S/N is the signal-to-noise ratio of GW signals, T is the total observation time. In principle, LISA can only detect ḟ for compact binaries with sufficiently high S/N, which have already evolved close to their minimum orbital period, whereḟ is the largest. For a 4-year LISA mission and a GW source with S/N = 10, the detection limit is ḟgw,min ≈ 2.5 × 10−17 Hz s−1.

Figure 10 shows the evolution of the GW frequency derivative of the IMBH binaries in Figure 6 in the ḟgw vs. fgw diagram. The ḟ of two detached systems with Porb, i = 5.93 and 5.7 days exceed the detection limit of ḟgw,min ≈ 2.5 × 10−17 Hz s−1 within the frequency range of 0.7 − 0.9 mHz. Therefore, it can only accurately measure the GW frequency derivatives and chirp masses for IMBH binaries whose initial orbital periods are very close to the bifurcation periods. The evolutionary curves of these two systems are tilted lines with slope Δ log|ḟgw| Δ log fgw ≈ 4.3. According to equation (9), pure GW radiation predicts a relation  for a constant chirp mass in a detached system. This results in a ratio Δ log|ḟgw| Δ log fgw = 11/3, which is less than 4.3. This implies that DF from DM also contributes substantially to the orbital decay of these two IMBH binaries.

for a constant chirp mass in a detached system. This results in a ratio Δ log|ḟgw| Δ log fgw = 11/3, which is less than 4.3. This implies that DF from DM also contributes substantially to the orbital decay of these two IMBH binaries.

|

Fig. 10. Evolution of GW-frequency derivative for IMBH binaries in Figure 6 in the |ḟgw| vs. fgw diagram. The horizontal dashed blue line represents the detection limitation of LISA when S/N = 10 and T = 4 yr. |

4.4. Birth rate of Galactic IMBH binaries as low-frequency GW sources

Intermediate-mass black holes (IMBHs) could be hosted by globular clusters, young dense clusters, and dwarf galaxies. It is generally thought that young dense clusters are too young to form compact IMBH X-ray binaries. Holley-Bockelmann et al. (2008) found that only 60 of the 137 Galactic globular clusters can retain IMBHs with an initial mass of 1000 M⊙. Assuming NIMBH = 60, the birth rate of IMBH X-ray binaries as low-frequency GW sources can be expressed as

where Γ ∼ 5 × 10−8 yr−1 is the capture rate of companion stars by IMBHs (Hopman et al. 2004), P is the probability that IMBH binaries evolve into LISA sources, and tGC and tMS are the lifetimes of globular clusters and MS stars, respectively. Within our parameter space, roughly 110 IMBH binaries (see also the number of solid stars) can evolve toward low-frequency GW sources. In the range Md, i = 1.0 − 3.4 M⊙ and Porb, i = 0.65 − 16.82 days, 1040 IMBH binaries exist. Assuming uniform distributions of donor-star masses and orbital periods for tidally captured IMBH binaries, the probability is P ≈ 0.1. This probability aligns with that reported in Chen (2020). Adopting a total parameter space Md, i = 1.0 − 3.0 M⊙ and Porb,i = 0.5−3.5 days as in Chen (2020) yields P ≈ 0.2. Assuming tGC ∼ 2tMS, the birth rate of Galactic IMBH binaries as low-frequency GW sources can be estimated as ∼1.2 × 10−6 yr−1, which is twice the value of ∼6 × 10−7 yr−1 given in Chen (2020). Therefore, DF from DM with γ = 1.6 can only enhance the birth rate and widen the parameter space by a factor of ∼2.

4.5. Tidal disruption events

In a detached IMBH-WD binary, a tidal disruption event is expected once the WD enters the tidal radius of the IMBH. The radius of a WD is given by (Rappaport et al. 1987; Tout et al. 1997)

where Mwd is the WD mass and Mch = 1.44 M⊙ is the Chandrasekhar mass limit. For an IMBH-WD binary with MBH = 1000 M⊙ and Mwd = 0.3 M⊙, the radius of the WD is Rwd = 0.018 R⊙, and the tidal radius can be calculated as Rt = (MBH/Mwd)1/3Rwd = 0.27 R⊙. When the tidal radius is equal to the orbital separation, the GW frequency of this system is

Therefore, it is possible to simultaneously detect low-frequency GW signals with tens of millihertz and tidal disruption events from an IMBH-WD system.

4.6. Uncertainties of input parameters in DM spike model

In the DM spike model, we adopt a fixed spike radius rsp = 0.2rin and a DM background density distribution ρ0 = ρ⊙ = 0.33 ± 0.03 GeV cm−3. From Equation (2), larger rsp and higher ρ0 tend to result in higher DM density at the position of the donor star. Higher DM density naturally leads to more efficient loss of angular momentum, making it easier for these IMBH-MS binaries to evolve toward low-frequency GW sources. Consequently, the initial parameter space that can evolve into low-frequency GW sources is enlarged in the Md, i − Porb, i diagram.

We assumed a constant spike index in our detailed stellar evolution model. However, the interaction between the donor star and the DM via gravitational scattering would drive the DM particles into the BH, resulting in a decrease of the spike index through kinetic heating (Gnedin & Primack 2004; Merritt 2004). When gravitational scattering of stars is significant, the spike index evolves to 1.5 due to the kinetic heating process in the heating timescale (Merritt 2004; Chan & Lee 2023)

When MBH = 1000 M⊙, Md, i = 2.7 M⊙, Porb,i = 1.0 day, and γ = 1.6, we find rin ≈ 37.9 pc. The heating timescales are 15.3 and 32.8 Gyr when the system appears as a low-frequency GW source at a distance of 1 kpc (Md ∼ 0.6 M⊙) and 10 kpc (Md ∼ 0.25 M⊙), respectively. These two heating timescales are much longer than the evolutionary timescales (1.5−1.7 Gyr; see also Figure 2). Therefore, the change in the spike index can be safely ignored during the evolution of IMBH-MS binaries.

4.7. A general DF model

Our work employs the standard Chandrasekhar formulation (Chandrasekhar 1943), which neglects the contribution of fast-moving DM particles to the frictional force. According to this formulation, DF with any γ > 1.5 tends to circularize the orbits of binary systems (Gould & Quillen 2003). Including DF due to the fact that DM particles move faster than an inspiral object, the DF effect circularizes the orbit for any γ > 1.8 (Dosopoulou 2024). Recently, the threshold of the spike index that results in an increase in eccentricity was found to be 2.0 (Zhou et al. 2025); below this value, DF from fast-moving DM particles will cause the orbit to become more eccentric. However, the increased timescale for eccentricity by DF is 10^6−107 yr (see also Figure 2 of Zhou et al. (2025)), which is much longer than the circularization timescale (∼104 yr) due to the tidal interaction between an MS star near RLOF and an IMBH (Claret & Cunha 1997). Therefore, the general DF model does not significantly influence our simulated results.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we employ a detailed stellar evolution model to investigate whether DF from DM can drive IMBH-MS binaries to evolve toward low-frequency GW sources. Our main conclusions are summarized as follows.

-

The DF of DM provides an efficient mechanism for extracting orbital angular momentum and can drive some IMBH binaries with MS companions to evolve toward low-frequency GW sources. The loss rate of angular momentum is closely related to the donor star mass, the spike index, and the orbital period.

-

Considering DF from DM, IMBH binaries with low-mass companions tend to evolve into low-frequency GW sources in the X-ray stage. However, some IMBH binaries with high-mass companions can also evolve into low-frequency GW sources because of GR after becoming detached systems.

-

A higher spike index produces a higher DM density at the position of the donor star, resulting in a higher loss rate of angular momentum and a shorter evolutionary timescale. When Md, i = 3.0 M⊙ and Porb, i = 1.0 days, there exists a critical spike index γ = 1.66, below which DF cannot drive IMBH binaries to evolve toward low-frequency GW sources.

-

The IMBH-MS binaries with initial orbital periods shorter than the bifurcation periods can evolve toward low-frequency GW sources. The low-frequency GW sources whose initial orbital periods are equal to the bifurcation periods are detached systems consisting of an IMBH and a WD, while the donor stars of other GW sources are mass-transferring MS stars.

-

We identify an initial parameter space of IMBH-MS binaries that can evolve into low-frequency GW sources in the orbital period versus donor-star mass plane. For γ = 1.60, binaries with Md, i = 1.0 − 3.4 M⊙ and Porb, i = 0.65 − 16.82 days can evolve into visible LISA sources within a distance of d = 10 kpc. Compared to the standard magnetic braking model, DF from DM with γ = 1.6 can enhance the birth rate and widen the parameter space by a factor of ∼2.

-

In the low-frequency GW source stage, the X-ray luminosities of these IMBH X-ray binaries are ∼ 1035−1036 erg s−1, detectable by X-ray telescopes at 10 kpc. Only those IMBH X-ray binaries with initial orbital periods very close to the bifurcation periods have measurable GW frequency derivatives and chirp masses.

Acknowledgments

We thank the referee for a very careful reading and constructive comments that have led to the improvement of the manuscript. We also thank Thomas Tauris, Yi-Ming Hu, Sheng-Hua Yu, and Yan Wang for their helpful discussions. This work was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (under grant Nos. 12273014 and 12203051), and the Shandong Province Natural Science Foundation (under grant No. ZR2021MA013).

References

- Amaro-Seoane, P., Andrews, J., Arca Sedda, M., et al. 2023, Liv. Rev. Rel., 26, 2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgardt, H., Hopman, C., Portegies Zwart, S., & Makino, J. 2006, MNRAS, 372, 467 [Google Scholar]

- Chan, M. H., & Lee, C. M. 2023, ApJ, 943, L11 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar, S. 1943, ApJ, 97, 255 [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-C. 2020, ApJ, 896, 129 [Google Scholar]

- Claret, A., & Cunha, N. C. S. 1997, A&A, 318, 187 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert, E. J. M., & Mushotzky, R. F. 1999, ApJ, 519, 89 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dosopoulou, F. 2024, Phys. Rev. D, 110, 083027 [Google Scholar]

- Eda, K., Itoh, Y., Kuroyanagi, S., & Silk, J. 2015, Phys. Rev. D, 91, 044045 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C. R., Iben, I., Jr, & Smarr, L. 1987, ApJ, 323, 129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H., & Soria, R. 2011, New A Rev., 55, 166 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, F., Medeiros da Rosa, A., & Will, C. M. 2017, Phys. Rev. D, 96, 083014 [Google Scholar]

- Fields, B. D., Shapiro, S. L., & Shelton, J. 2014, Phys. Rev. Lett., 113, 151302 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finn, L. S., & Thorne, K. S. 2000, Phys. Rev. D, 62, 124021 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gnedin, O. Y., & Primack, J. R. 2004, Phys. Rev. Lett., 93, 061302 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, L. G., & Rueda, J. A. 2017, Phys. Rev. D, 96, 063001 [Google Scholar]

- Gondolo, P., & Silk, J. 1999, Phys. Rev. Lett., 83, 1719 [Google Scholar]

- Gould, A., & Quillen, A. C. 2003, ApJ, 592, 935 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Holley-Bockelmann, K., Gültekin, K., Shoemaker, D., & Yunes, N. 2008, ApJ, 686, 829 [Google Scholar]

- Hopman, C., Portegies Zwart, S. F., & Alexander, T. 2004, ApJ, 604, L101 [Google Scholar]

- Istrate, A. G., Marchant, P., Tauris, T. M., et al. 2016, A&A, 595, A35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jani, K., Shoemaker, D., & Cutler, C. 2020, Nat. Astron., 4, 260 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaret, P., Prestwich, A. H., Zezas, A., et al. 2001, MNRAS, 321, L29 [Google Scholar]

- Kalogera, V., Henninger, M., Ivanova, N., & King, A. R. 2004, ApJ, 603, L41 [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh, B. J., Nichols, D. A., Bertone, G., & Gaggero, D. 2020, Phys. Rev. D, 102, 083006 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Körding, E., Falcke, H., & Markoff, S. 2002, A&A, 382, L13 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, T. 2018, A&A, 619, A46 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.-D. 2004, ApJ, 616, L119 [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J., Chen, L.-S., Duan, H.-Z., et al. 2016, Class. Quant. Grav., 33, 035010 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Madau, P., & Rees, M. J. 2001, ApJ, 551, L27 [Google Scholar]

- Madhusudhan, N., Justham, S., Nelson, L., et al. 2006, ApJ, 640, 918 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, P. J. 2017, MNRAS, 465, 76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, D. 2004, Phys. Rev. Lett., 92, 201304 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. M., Fabian, A. C., & Miller, M. C. 2004, ApJ, 614, L117 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, R., & Yi, I. 1995, ApJ, 452, 710 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M. A. 1995, PASP, 107, 1207 [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, R. M., Rasio, F. A., Fregeau, J. M., Ivanova, N., & O’Shaughnessy, R. 2006, ApJ, 637, 937 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pasham, D. R., Strohmayer, T. E., & Mushotzky, R. F. 2014, Nature, 513, 74 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Bildsten, L., Dotter, A., et al. 2011, ApJS, 192, 3 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Cantiello, M., Arras, P., et al. 2013, ApJS, 208, 4 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Marchant, P., Schwab, J., et al. 2015, ApJS, 220, 15 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Schwab, J., Bauer, E. B., et al. 2018, ApJS, 234, 34 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Smolec, R., Schwab, J., et al. 2019, ApJS, 243, 10 [Google Scholar]

- Portegies Zwart, S. F., & McMillan, S. L. W. 2002, ApJ, 576, 899 [Google Scholar]

- Portegies Zwart, S. F., Baumgardt, H., Hut, P., Makino, J., & McMillan, S. L. W. 2004a, Nature, 428, 724 [Google Scholar]

- Portegies Zwart, S. F., Dewi, J., & Maccarone, T. 2004b, MNRAS, 355, 413 [Google Scholar]

- Qin, K., & Chen, W.-C. 2024, ApJ, 971, 57 [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, S., Verbunt, F., & Joss, P. C. 1983, ApJ, 275, 713 [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, S., Nelson, L. A., Ma, C. P., & Joss, P. C. 1987, ApJ, 322, 842 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Robson, T., Cornish, N. J., & Liu, C. 2019, Class. Quant. Grav., 36, 105011 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, W.-H., Liu, C., Guo, Z.-K., Wu, Y.-L., & Cai, R.-G. 2020, Nat. Astron., 4, 108 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghian, L., Ferrer, F., & Will, C. M. 2013, Phys. Rev. D, 88, 063522 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sen, K., Xu, X. T., Langer, N., et al. 2021, A&A, 652, A138 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sepinsky, J. F., Willems, B., Kalogera, V., & Rasio, F. A. 2010, ApJ, 724, 546 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, R., & Seto, N. 2002, ApJ, 575, 1030 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tauris, T. M. 2018, Phys. Rev. Lett., 121, 131105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tout, C. A., Aarseth, S. J., Pols, O. R., & Eggleton, P. P. 1997, MNRAS, 291, 732 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluys, M. V., Verbunt, F., & Pols, O. R. 2005a, A&A, 431, 647 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluys, M. V., Verbunt, F., & Pols, O. R. 2005b, A&A, 440, 973 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Vesperini, E., McMillan, S. L. W., D’Ercole, A., & D’Antona, F. 2010, ApJ, 713, L41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.-T., Jiang, Z., Sesana, A., et al. 2019, Phys. Rev. D, 100, 043003 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, N., Cseh, D., Lenc, E., et al. 2012, Science, 337, 554 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.-J., Han, W.-B., & Chen, X. 2019, ApJ, 874, 34 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.-C., Jin, H.-B., Qiao, C.-F., & Wu, Y.-L. 2025, ApJ, 986, 196 [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Dark matter density profiles with different spike indices around an IMBH of MBH = 1000 M⊙. The vertical dashed orange line indicates a radius of r = 2.93 × 1012 cm, which is the orbital separation of a system consisting of a 1000 M⊙ IMBH and a 1 M⊙ MS star in a 1.0-day orbit. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with an initial orbital period of Porb,i = 1.0 day and varying initial donor-star masses. Top panel: Orbital period vs. stellar age. Bottom panel: Orbital period vs. donor-star mass for γ = 1.60. Open circles, solid triangles, and solid stars indicate the onset of RLOF and the points at which IMBH binaries become visible by LISA at distances of 1 kpc and 10 kpc, respectively. Sources marked by open triangles become undetectable by LISA at 1 kpc. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with Porb,i = 1.0 day and varying donor-star masses. Top panel: Orbital period vs. stellar age. Bottom panel: Orbital period vs. donor-star mass for γ = 1.80. Symbols are the same as in Figure 2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Evolution of IMBH binaries with Porb,i = 1 day and varying donor-star masses. Top panel: Characteristic strain vs. GW frequency diagram when γ = 1.60; bottom panel: γ = 1.80. The blue curve shows the LISA sensitivity based on a numerical calculation for a mission duration of four years. The red and green curves correspond to the sensitivity curves of TianQin (Wang et al. 2019) and Taiji (Ruan et al. 2020), respectively. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with Md, i = 3.0 M⊙, Porb,i = 1.0 day, and varying spike indices shown in the orbital period vs. stellar age diagram. Symbols are the same as in Figure 2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Evolution of IMBH-MS binaries with Md, i = 1.2 M⊙, γ = 1.60, and varying initial orbital periods. Top panel: Orbital period vs. stellar age. Bottom panel: Orbital period vs. donor-star mass. Symbols are the same as in Figure 2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Parameter space distribution of IMBH-MS binaries that can evolve into low-frequency GW sources detectable by LISA, shown in the initial orbital period vs. initial donor-star mass diagram. A constant DM spike index of γ = 1.60 is adopted. The solid curve denotes the bifurcation periods of IMBH binaries with varying donor-star masses. The solid circles and stars represent IMBH binaries that will evolve into low-frequency GW sources detectable by LISA within distances of d = 1 and 10 kpc, respectively. Crosses indicate binaries for which RLOF already occurs at the beginning of binary evolution. When the initial periods are above the bifurcation period, those systems will evolve into IMBH binaries with long periods. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Evolution of the companion stars in the HR diagram for IMBH-MS binaries shown in Figures 2 (top panel) and 5 (bottom panel). The open circles, solid triangles, and solid stars indicate the beginning of RLOF and the points at which IMBH binaries become detectable by LISA at distances of 1 kpc and 10 kpc, respectively. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9. Evolution of X-ray luminosity for IMBH X-ray binaries with initial orbital period Porb,i = 1.0 day and varying initial donor-star masses when γ = 1.60 (top panel; same as Figure 2) and γ = 1.80 (bottom panel; same as Figure 3). The solid triangles and solid stars denote the onset times at which IMBH X-ray binaries become detectable by LISA within distances of 1 and 10 kpc, respectively. The first solid triangle in the bottom panel marks the evolutionary curve for Md, i = 3.0 M⊙. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10. Evolution of GW-frequency derivative for IMBH binaries in Figure 6 in the |ḟgw| vs. fgw diagram. The horizontal dashed blue line represents the detection limitation of LISA when S/N = 10 and T = 4 yr. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.