| Issue |

A&A

Volume 703, November 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A200 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554729 | |

| Published online | 20 November 2025 | |

Role of the δ meson in the equation of state and direct Urca cooling of neutron stars

1

CFisUC, Department of Physics, University of Coimbra, 3004-516 Coimbra, Portugal

2

Université de Caen Normandie, CNRS/IN2P3, LPC Caen, 14050 Caen, France

3

IUF, service du Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche, 1 rue Descartes, 75231 Paris Cedex 5, France

⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

24

March

2025

Accepted:

13

September

2025

Context. The direct Urca (dUrca) process is a key mechanism driving rapid neutrino cooling in neutron stars. Its baryon density activation threshold is determined by the microscopic model for nuclear matter. Nuclear interactions shape the dUrca threshold, and it is essential to understand this for interpreting the thermal evolution of neutron stars, in particular in light of recent studies of exceptionally cold objects.

Aims. We investigated the impact of incorporating the scalar-isovector δ meson into the neutron star equation of state. This alters the internal proton fraction and consequently affects the dUrca cooling threshold. Proton superfluidity is known to suppress dUrca rates, and we therefore also examined the interplay between the nuclear interaction mediated by the δ meson and the 1S0 proton-pairing gap.

Methods. We performed a Bayesian analysis using models built within a relativistic mean-field approximation that incorporated constraints from astrophysical observations, nuclear experiments, and known results of ab initio calculations of pure neutron matter. We then imposed a constraint on the dUrca threshold based on studies of fast-cooling neutron stars.

Results. The inclusion of the δ meson expands the range of possible internal compositions and directly influences the stellar mass required for the central density to reach the dUrca threshold. Furthermore, we find that the observation of relatively young and cold neutron stars provides insights into the 1S0 proton superfluidity in the core of neutron stars.

Key words: dense matter / equation of state / stars: neutron

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

The advent of multimessenger astronomy, in particular, the detection of gravitational waves, has provided new tools for investigating the equation of state (EoS) of neutron stars (NSs), and it renewed interest in understanding their internal composition. The observation of GW170817 by Abbott et al. (2017a, 2019), combined with mass and radius inferences of PSR J0030+0451 (Riley et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2019), PSR J0740+6620 (Riley et al. 2021; Miller et al. 2021), and PSR J0437+4715 (Choudhury et al. 2024a,b) by the Neutron Star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) experiment, has placed constraints on the high-density regime of the EoS. These constraints can be complemented by information from the low-density regime provided by nuclear experiments and ab initio calculations (see Hebeler et al. 2013; Huth et al. 2021; Adhikari et al. 2021, 2022). These constraints have been extensively used in the literature to largely explore the EoS parameter space with a variety of approaches. Agnostic methods include piecewise polytropes (Read et al. 2009), spectral parameterizations (Lindblom 2010; Lindblom & Indik 2012, 2014), Gaussian process-based sampling (Landry & Essick 2019; Essick et al. 2020; Landry et al. 2020), and neural networks (Han et al. 2023). Other approaches involve nonrelativistic (Margueron & Gulminelli 2019; Mondal et al. 2023; Montefusco et al. 2025) and relativistic (Providência et al. 2019; Char et al. 2023; Malik et al. 2024; Scurto et al. 2024) mean-field (RMF) calculations.

Marino et al. (2024) recently suggested based on the analysis of data from XMM-Newton and Chandra that the direct Urca (dUrca) process may be necessary to explain the observed temperatures of three exceptionally cold and relatively young NSs. The presence of fast-cooling objects like this was suggested before through the study of isolated NSs by Potekhin et al. (2015), Potekhin & Chabrier (2018) and of transiently accreting NSs (Potekhin et al. 2023). The existence of these objects may place nontrivial constraints on the NS EoS because enhanced cooling mechanisms such as neutrino emission through dUrca processes are required to fit theoretical models to observational data. While this enhanced cooling might alternatively be explained with the presence of exotic matter such as hyperons or quark matter (Prakash et al. 1992, 1996; Fortin et al. 2021), the possibility that it might be caused by the nucleonic direct Urca process needs to be studied in detail. Proton superfluidity in the core is known to suppress fast dUrca processes when the temperature is below the pairing gap (see Page & Applegate 1992; Levenfish & Yakovlev 1994; Wei et al. 2019; Sedrakian & Clark 2019).

In a previous interesting attempt to constrain superfluidity from observational cooling data by Beloin et al. (2018), some assumptions were made, such as neglecting the mass distribution of isolated NSs and the uncertainty in the EoS. The pairing gaps depend on density and composition, however, and thus on the stellar mass and EoS both. To investigate the complex interplay between EoS and composition, we therefore introduced hypothetical constraints on the mass threshold for the onset of the dUrca process and analyzed how these constraints affect the posterior distributions of astrophysical observables, the EoS, and the pairing properties of nuclear matter.

To this end, we followed the approach of Wei et al. (2020) and Das et al. (2024) for pairing and assumed a simplified model for the 1S0 proton-pairing gap. This is essentially a rescaled version of the BCS pairing gap computed by Lombardo & Schulze (2001).

To account for the uncertainties in the composition, we built a large family of stable and causal nuclear EoSs within the RMF approach, in which the nuclear interaction is mediated by the exchange of virtual mesons. In most applications of this formalism (see Serot & Walecka 1986; Providência et al. 2019; Pais et al. 2015; Char et al. 2023; Scurto et al. 2024; Malik et al. 2024), three mesons are typically considered: the scalar-isoscalar meson σ, the vector-isoscalar meson ω, and the vector-isovector meson ρ. In this standard implementation, however, the absence of isospin dependence in the mass term leads to identical effective Dirac masses for protons and neutrons, which is not expected from microscopic calculations (see van Dalen et al. 2005; Wang et al. 2023). To address this limitation, several studies have introduced a fourth meson, the scalar-isovector meson δ (see Liu et al. 2002; Gaitanos et al. 2004; Menezes & Providência 2004; Pais et al. 2009; Roca-Maza et al. 2011). The δ meson also plays a strong role in the symmetry energy and its derivatives Liu et al. (2002), Gaitanos et al. (2004), and this affects the proton fraction of the system.

While the existence of a mass splitting is firmly established, its actual value and density dependence is largely unconstrained (see, e.g., Margueron et al. 2018a for a discussion). The impact of the δ meson on the EoS has recently been investigated by Santos et al. (2025), who selected three models without the δ meson from previous works and extended them by including this additional meson. They found that this interaction channel has a strong effect on the macroscopic properties of the stars, namely the radius and tidal deformability of low- and intermediate-mass stars, and also on their proton content in the core, which is a key variable for the possibility of nucleonic dUrca.

Motivated by these results, we conducted a comprehensive Bayesian analysis on two sets of RMF models (with and without the δ meson) and largely varied their unknown effective coupling to the nucleons to understand the role of this additional meson on stellar properties. In particular, we show that including the δ meson enhances the flexibility of the models, which broadens the range of proton fractions at high densities with respect to previous Bayesian studies (e.g., Malik et al. 2022).

The structure of the paper is as follows. In the next section, we present the RMF formalism we adopted. Sect. 3 outlines the framework we used for the Bayesian analysis. In Sect. 4 we discuss the results of the comparison between the models with and without the δ meson. Sect. 5 introduces the constraints on the dUrca threshold and the proton-pairing gap and examines their effects. In Sect. 6 we summarize our results. More details on the RMF formalism and the predictions for observables related to nuclear physics are reported in the appendices.

2. Construction of the equation of state

To set up our family of EoSs, we worked within the RMF approximation, in which virtual mesons mediate the interaction between nucleons. Specifically, we compared the results obtained from two sets of EoS models, each based on a different structure of the Lagrangian density that describes the system. The first set, referred to as Set A, includes three mesonic fields that mediate the nucleon interactions: the scalar-isoscalar meson σ, the vector-isoscalar meson ω, and the vector-isovector meson ρ. The second set, referred to as Set B, extends this framework by incorporating an additional meson, the scalar-isovector meson δ. In the following sections, we discuss the results we obtained from these two sets and explore the effects of the δ meson on the EoS and astrophysical predictions.

Our RMF procedure is based on the standard phenomenological Lagrangian density form,

where ℒL is the leptonic contribution, and ℒσ, ω, ρ, δ are the contributions of the pure mesonic fields (see Appendix A for details).

We focused on the first term, which describes the nucleons,

where the Dirac field ψ = (ψn, ψp)T carries an isospin index (τ are Pauli matrices acting in isospin space), and

is the effective nucleon mass, with M = Mp = Mn = 938.9 MeV the bare nucleon mass1. The main effect of δ = (0, 0, δ3) is to introduce an isospin dependence on the effective mass, M* = diag(Mn, Mp), with

for the neutrons and protons, respectively (see, e.g., Liu et al. 2002; Menezes & Providência 2004; Pais et al. 2009; Roca-Maza et al. 2011). The case without the additional meson can be recovered by switching off the coupling between the δ meson and the nucleons by setting gδ = 0: This automatically implies that δ3 = 0 (see Eq. (A.9)).

Furthermore, we considered the nucleon-meson couplings as functions of the total baryonic density by adopting the density dependence previously used by Malik et al. (2022),

where x = n/nsat is the baryon number density n measured in units of nsat, which is the saturation density of symmetric matter. The parameters ai, bi, and ci are free and were varied to sample various nuclear models. Their specific value defines each model within the two sets A and B. Hence, each model is uniquely specified by 9 parameters for Set A (without the δ meson) and 12 parameters for Set B (with the δ meson, which induces the effective mass splitting).

We demonstrate that incorporating the δ meson allows the density dependence in (5) to reproduce nearly the entire range of results obtained by Char et al. (2023), Scurto et al. (2024), who used the more general GDFM formulation of Gogelein et al. (2008)2.

3. Bayesian setup

We now present the method we used for our Bayesian analysis, which closely follows the approach detailed by Scurto et al. (2024). We first briefly introduce the way the initial sets of EoSs are built, and then show how the posterior distributions are obtained.

3.1. Construction of the prior

We begin by outlining the procedure we used to construct the prior distribution. As discussed above, our goal was to compare results obtained from two prior sets: Set A, where the interaction mediated by the δ meson is switched off, and Set B, where it is accounted for.

Following Scurto et al. (2024), instead of directly sampling all coupling parameters that appear in ℒ, we sampled a combination of nuclear matter parameters (NMPs; defined in Appendix B) and coupling parameters using uniform distributions. The ranges we used for the sampling are shown in Appendix A. The remaining coupling parameters were then computed using analytical relations that can be found in Appendix B. The chosen parameters are very little correlated, and the sampling ranges were set to explore a broad parameter space while ensuring physically meaningful models.

The sampled models were then filtered based on the following criteria: Each equation of state must have a monotonically increasing energy density and pressure for neutron and beta-equilibrated matter, must only show the expected minimum in the energy per baryon of symmetric matter at saturation, and it must yield a minimum χ2 in the nuclear mass fit we used to calculate the crust (see Scurto et al. 2024 for details). After filtering, we obtained two prior distributions, each containing 106 models.

3.2. Posterior distribution

With the prior distributions established, we derived the posterior distributions by incorporating constraints from astrophysical observations, nuclear experiments, and ab initio calculations. The posterior probability for a given EoS is

where X represents the 9 (12) parameters defining the EoS, which are listed in detail in Table B.2, and the label k runs over the set of constraints c. The probability distributions for observables Y(X) were obtained through marginalization over the parameter space (N = 9 for Set A, and N = 12 for Set B)

In the following, we briefly recall the constraints we used.

3.2.1. Astrophysical constraints

The astrophysical constraints are the same as in Scurto et al. (2024), Davis et al. (2024), Montefusco et al. (2025), including: the maximum mass constraint from PSR J0348+0432 reported by Antoniadis et al. (2013), the tidal deformability constraint by GW170817 taken from Abbott et al. (2017a,b, 2019)3, and the radius constraints from NICER observations were included for PSR J0030+0451 Riley et al. (2019), Miller et al. (2019), PSR J0740+6620 Riley et al. (2021), Miller et al. (2021), and PSR J0437+4715 Choudhury et al. (2024a,b). While the most recent constraint from 2024 remains debated, we found its impact on the posterior distributions to be negligible when all other constraints (astrophysical and nuclear) were taken into account.

3.2.2. Nuclear experimental constraints

The nuclear experimental constraint followed Scurto et al. (2024), who applied a Gaussian likelihood model P({μi, σi}|X) to the four NMPs (ρsat, Esat, Ksat, and Jsym) and to the combination

The Gaussian parameters {μi, σi} are listed in detail in Table B.1 and reflect the expectation and uncertainty of the five parameters taken from Margueron et al. (2018b), who obtained an indirect constraint on these quantities by comparing the experimental results with the predictions of different nuclear physics models. To implement the constraints on the NMPs, we assumed uncorrelated distributions,

where i runs over the set (nsat, Esat, Ksat, Jsym, and Kτ)4.

3.2.3. Chiral EFT constraints

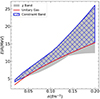

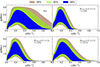

The ab initio constraints on the energy per baryon of neutron matter were taken from Huth et al. (2021), who synthesized results from several previous calculations (Hebeler et al. 2013; Tews et al. 2013; Lynn et al. 2016; Drischler et al. 2019, 2021). A likelihood model was constructed assuming the energy band defined by Huth et al. (2021) as a flat 68% probability distribution that extens according to Equation (36) of Scurto et al. (2024). For the lower bound of the band, we took the maximum between the lower bound of the band shown in Fig. 1 of Huth et al. (2021) and the energy per baryon of the unitary gas from Tews et al. (2017), as previously done by Montefusco et al. (2025) (see also Sammarruca 2023). The corresponding energy band we used in the constraint is shown in Fig. 1.

|

Fig. 1. Energy per particle of pure neutron matter as a function of the density for the χ-EFT constraint we used (blue band), of the calculations shown in Fig. 1 of Huth et al. (2021) (gray band), and of the unitary gas limit (solid red line). |

4. Comparison between Set A and Set B

We now compare the results we obtained for Set A and Set B.

In Fig. 2 we present the prior and posterior distributions for the mass and central density of the most massive star supported by each EoS, as well as the radius, tidal deformability, and central density of a 1.4 M⊙ star. The distributions of the parameters related to the most massive star remain largely unaffected by the isospin mass splitting. This outcome agrees with the findings of Scurto et al. (2024), who indicated that these quantities are more strongly correlated with the isoscalar sector, which is not significantly affected by the δ meson. Conversely, the properties of the 1.4 M⊙ star are noticeable modified by the additional meson, with broader distributions for the radius and deformability. This allows lower values in the case of Set B.

|

Fig. 2. Marginalized posterior of the maximum mass (first panel), the central density of the most massive star (second panel), the radius (third panel), the tidal deformability (fourth panel), and the central density (fifth panel) of an NS with a mass of 1.4 M⊙ for the prior (dotted) and posterior (solid) distributions for Set A (blue) and Set B (green). |

The distribution of the central density is also broader and slightly shifted toward higher densities in the case of Set B. In both cases, however, the peak of the posterior distribution for a canonical 1.4 M⊙ star lies between two and three times the nuclear saturation density. This relatively low value highlights the importance of including nuclear physics constraints in the Bayesian analysis alongside the astrophysical constraints.

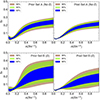

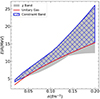

The significance of this result is highlighted in Fig. 3, where we show the 90% quantiles of the prior and posterior distributions for the M − R and M − Λ relations for both sets. In the case of the M − R relation, we also overlay the three NICER constraints. This demonstrates that the models featuring a smaller radius, present in Set B, play a crucial role in ensuring compatibility with the constraint from PSR J0437+4715, which favors more compact objects (difficult to generate within our RMF formalism). Fig. 3 also illustrates that the priors for Set A are entirely enclosed within those of Set B, which reinforces the hypothesis that the δ meson enhances the model flexibility.

|

Fig. 3. 90% quantiles for the distribution of the mass as a function of the radius (top panels) and as a function of the tidal deformability (bottom panels) for the prior (left) and posterior (right) distributions for Set A (blue) and Set B (green). In the M − R plots, we also show the 68% and 90% quantiles for the three NICER constraints. |

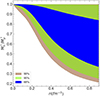

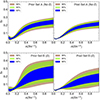

Fig. 4 displays the distribution of the proton fraction yp = np/(nn + np) as a function of density for both sets. A direct comparison with the results of Scurto et al. (2024) immediately reveals the effect of changes in the EoS model. Specifically, for Set A, the absence of the cubic term in the density-dependent couplings (see Eq. (5)) results in a narrower distribution of yp. This occurs because the models show no sharp increase in proton fraction around 0.4 fm−3. We observed this feature in our previous study. In contrast, when considering Set B, we find that the introduction of the δ meson not only restores the broadness of the distribution seen previously, but also smooths the proton fraction behavior. Additionally, the distribution extends symmetrically toward both higher and lower values of yp at higher densities, yielding models with yp below 0.1 at high densities. These were absent in the previous study.

|

Fig. 4. 68%, 95%, and 99% quantiles for the distribution of the proton fraction as a function of the baryonic density for the prior (left) and posterior (right) distributions for Set A (top) and Set B (bottom). |

The existence of models with this low yp can be explained by examining Fig. 5, which presents the ratio of neutron and proton Dirac masses as a function of density for neutron matter in Set B. The figure reveals that through the δ meson, the effective Dirac mass of the proton can become nearly two and a half times higher for the 68% quantile and up to five times higher than that of the neutron for the 99% quantile. This substantial mass difference favors neutron-rich matter, thereby explaining the very low proton fractions observed in the previous plot.

|

Fig. 5. 68%, 95%, and 99% quantiles for the posterior distribution of the ratio of the neutron and proton Dirac effective masses as a function of the baryonic density of purely neutron matter for Set B. |

Finally, we present in Fig. 6 the distributions for the mass, density, and proton fraction at which the threshold for the dUrca process is reached. The dUrca threshold for the proton fraction is given by Klahn et al. (2006) as

|

Fig. 6. Marginalized posterior of the mass at which the dUrca threshold is met (left) and the 2D marginalized posterior for the baryonic density and proton fraction for the same threshold for the prior (dotted) and posterior (solid) distributions for Set A (black) and Set B (blue). |

where xe = ne/(ne + nμ) is the leptonic electron fraction. The threshold density ndUrca is defined via yp(ndUrca) = yp, dUrca, and the threshold mass MdUrca corresponds to the mass of a star with a central density ndUrca.

The distributions in Fig. 6 for Set A are significantly narrower than those of Set B. Additionally, the posterior constraint for both sets shifts the peak of the mass distribution toward higher values. This effect is more pronounced in Set B because the distribution of Set A is narrower, which results in a lack of models with high MdUrca. The shift in threshold mass is directly linked to the corresponding shift in the joint distribution of ndUrca and yp, dUrca. Similarly, the posterior distribution shifts toward higher density values, and this trend can be traced back to Fig. 4: In agreement with Scurto et al. (2024), the constraints we applied to obtain the posterior (particularly the χ-EFT constraint) tend to disfavor models with a steep increase in the proton fraction.

5. Direct Urca constraint

Recent studies of NS cooling by Marino et al. (2024) reinforced the findings of previous works (Potekhin & Chabrier 2018; Potekhin et al. 2023) and highlighted the necessity of fast-cooling processes to account for the observed young but cold NSs. Based on this premise, we assumed that dUrca processes are essential and treated this as a hypothetical constraint. Following Margueron et al. (2018a), we compared the predictions obtained under different assumptions regarding the onset of the dUrca threshold.

We considered three possible scenarios. In the first, labeled “Always”, we assumed that the dUrca threshold is already met at low masses (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙). In the second, termed “Sometimes”, the threshold falls within the observed mass range of NSs (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙), as suggested by Marino et al. (2024). Finally, in the “Never” scenario, the threshold was either reached at masses exceeding the observed range (MdUrca > 2.1 M⊙) or was not met at all.

Margueron et al. (2018a) showed that the hypothesis on the dUrca does not significantly affect the distribution of the isoscalar sector of the NMPs. In the isovector sector, however, the dUrca constraint has a significantly stronger effect on the NMPs. For both sets, a lower dUrca threshold leads to higher values of Jsym, Lsym, and Ksym, as shown in Fig. 7. This behavior agrees with the trends seen in Fig. 6, where the posterior distribution in Set A (black line) is closer to the Always and Sometimes scenarios, whereas in Set B, it agrees better with the Sometimes and Never cases. This difference arises because in Set A, the posterior distribution of MdUrca is shifted toward lower values, with a limited number of models exhibiting a very high threshold mass. Conversely, in Set B, the mass distribution is shifted toward higher values, with fewer models having a low threshold mass.

|

Fig. 7. 68% (blue) 95% (green), and 99% (brown) quantiles for the 2D posterior distributions of Jsym (left), Lsym (center), and Ksym (right) with MdUrca for Set A (top row) and Set B (bottom row). |

Finally, we present in Fig. 8 the distributions of astrophysical observables. The quantities related to the most massive star are not strongly affected by the dUrca constraint. This can be attributed to the fact that these quantities are more strongly correlated with the NMPs in the isoscalar sector, which is not significantly influenced by the dUrca constraint. Conversely, the observables associated with the 1.4 M⊙ star are more constrained in Set B. Notably, the secondary peaks in the posterior distribution that appear at smaller radii, tidal deformabilities, and higher central densities are almost entirely associated with models from the Never scenario and vanish in the Always and Sometimes scenarios. This is consistent with the fact that Set A lacks models with very high dUrca threshold masses and models with small radii and tidal deformabilities for the 1.4 M⊙ star.

|

Fig. 8. Marginalized posterior of the astrophysical observables shown in Fig. 2 for Set A (top row) and Set B (bottom row). We show the results for the posterior without any assumption on the dUrca threshold (solid black line) as well as those including the three assumptions on the threshold Always (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙), Sometimes (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙), and Never (MdUrca > 2.1 M⊙) (dotted blue line, dashed orange line, and dash-dotted green line, respectively). |

Superfluidity plays a crucial role in the cooling of NSs, as discussed, for instance, by Yakovlev et al. (1999) (see Potekhin et al. 2015 for a review). In particular, proton superfluidity in the core suppresses the dUrca process, as shown by Wei et al. (2019). Because of the strong theoretical uncertainty on the effect of the medium polarization on the gap discussed by Lombardo & Schulze (2001), Drissi & Rios (2022), Pavlou et al. (2017), Benhar & De Rosi (2017), Gandolfi et al. (2022), we introduced a simplified model for the 1S0 proton-pairing gap Δ following Wei et al. (2020), Das et al. (2024). This is a rescaled version of the BCS pairing gap as calculated by Lombardo & Schulze (2001),

where ΔBCS represents the BCS pairing gap, np is the proton density, and sn and sΔ are free scaling parameters that encode the uncertainty on the polarization corrections to the BCS result. The gap was implemented by generating 100 pairs of sn and sΔ values for each model in both sets, drawing them from uniform distributions with limits 0.4 ≤ sn ≤ 1.4 and 0.2 ≤ sΔ ≤ 1.0 that we took from Das et al. (2024).

In principle, enhanced cooling via dUrca should be accounted for throughout the entire cooling history of a NS. Our approach would need to be coupled with a full cooling code to properly assess the relevance of different cooling processes, however (Potekhin et al. 2015), which is beyond the scope of this study. Studies of the thermal evolution of NSs by Yakovlev et al. (2005) and Page et al. (2004) indicated that they rapidly cool to surface temperatures of approximately T = 106.5 K. According to thermal profile studies by Gudmundsson et al. (1983), this corresponds to core temperatures of about T = 109 K.

Building on these findings, to gain at least a qualitative understanding of the constraints that potential evidence of enhanced cooling might impose on the underlying microphysics, we considered three schematic stellar temperature scenarios: a hot star (T = 1010 K), a warm star (T = 109 K), and a cold star (T = 108 K). For each case, we assumed that the dUrca process was suppressed as long as the gap remained above a threshold that was estimated by Bardeen et al. (1957) (see also Chamel & Haensel 2008),

where kB is the Boltzmann constant. At each temperature, the density for the dUrca threshold was determined as the maximum between ndUrca (as defined in the previous section) and nΔ, where nΔ is the density at which the proton density in the gap equation (11) satisfies the above condition, Eq. (12).

We underline that regardless of the value of the two scaling parameters, the density at which the gap satisfies Eq. (12) for T = 108 K is always close to the density at which the gap goes to zero. This means that any considered temperature below this value would yield almost indistinguishable results, and the T = 108 K case can safely be considered as T ≤ 108 K.

The introduction of the proton-pairing gap creates a temperature dependence of the dUrca threshold that causes a broadening like the one requested in the statistical analysis of cooling and heating sources by Beznogov & Yakovlev (2014).

By applying the same three assumptions for the dUrca threshold as in the previous section, we obtained more realistic estimates for the posterior EoS distribution while simultaneously imposing constraints on the pairing gap. The uncertainty on the gap is large, and the distributions for the astrophysical observables and the properties of nuclear matter are therefore not significantly modified with respect to what is shown above. On the other hand, the gap itself is significantly constrained by the three scenarios we considered for the dUrca process.

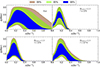

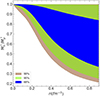

In Figs. 9 and 10, we show the posterior distribution of the pairing gap as a function of baryonic density. We compare results without any dUrca constraint to those under the Always and Sometimes dUrca threshold scenarios, respectively. We considered the three stellar temperatures discussed above.

|

Fig. 9. 68% (blue) 95% (green), and 99% (brown) quantiles for the posterior distributions of the pairing gap as a function of the baryonic density of beta-equilibrated matter for Set B. We show the results for the posterior without assumptions on the dUrca threshold (top left), as well as when the Always (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙) assumption for the dUrca threshold is made for a star at T = 108 K (top right), T = 109 K (bottom left), and T = 1010 K (bottom right). |

|

Fig. 10. 68% (blue) 95% (green), and 99% (brown) quantiles for the posterior distributions of the pairing gap as a function of the baryonic density of beta-equilibrated matter for Set B. We show the results for the posterior without assumptions on the dUrca threshold (top left), as well as when the Sometimes (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙) assumption for the dUrca threshold is made for a star at T = 108 K (top right), T = 109 K (bottom left), and T = 1010 K (bottom right). |

We only show the results for Set B because while the distribution in the case without the dUrca constraint appears to be narrower in the case of Set A, the distributions for Set A and Set B appear to be almost indistinguishable when the dUrca constraint is considered. The two figures show that when the dUrca constraint is imposed, the distribution narrows considerably along the x-axis compared to the unconstrained case.

This effect is significantly stronger within the Always hypothesis, as expected, because the constraint is more stringent. It is important to stress that the Sometimes scenario is the most realistic scenario according to astrophysical observations, however (see Beznogov & Yakovlev 2014; Potekhin & Chabrier 2018; Potekhin et al. 2023; Marino et al. 2024). We do not show the results in the Never scenario because it is the least constraining for the pairing gap.

As expected, the effect on the pairing gap is more pronounced for low temperatures T ≤ 108 K as significant temperatures for the cooling process, which is the most realistic scenario. The value of the peak of the gap is not strongly constrained either. These results can be better understood by considering the effect of the constraint on the two scaling parameters of Eq. (11) (shown in Appendix C).

6. Conclusions

We analyzed the effect of the considerable uncertainty in the neutron–proton effective mass splitting by introducing an additional scalar–isovector meson coupling in the RMF formalism, namely the δ meson. Following Scurto et al. (2024), we performed a Bayesian analysis to compare results obtained with and without this additional meson. Our findings indicate that the δ meson significantly affects both nuclear matter properties and NS observables. For example, its inclusion broadens the distribution of NMPs in the isovector sector, which shifts the expectation of Lsym and Ksym to lower values.

For NS observables, we found that while the properties of the most massive star remain largely unchanged, the presence of the δ meson results in broader distributions for the radius and tidal deformability of stars with masses of about 1.4 M⊙. Moreover, when the δ meson was included, the proton fraction distribution in beta-equilibrated matter became significantly broader at higher densities, and models with yp < 0.1 at 1 fm−3 became possible. This effect extends to the distribution of the dUrca process threshold, which increased notably in the set that included δ. The peak of the mass threshold distribution shifted to higher values.

The substantial effect of the δ meson on the dUrca threshold motivated us to introduce a hypothetical constraint on the mass threshold for this process. The comparison of three different scenarios against this constraint revealed that different assumptions for the threshold onset yielded varying predictions for the mean values of NMPs in the isovector sector.

Finally, we introduced a simple and flexible model for the 1S0 proton-pairing gap (Das et al. 2024). We demonstrated that the dUrca threshold constraint can be used to predict the in-medium effects on the pairing gap, which are known to modify the simple prediction of the BCS theory, but are not fully assessed. In particular, when we assumed that the dUrca threshold lay within the range 1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙, the density at which the gap vanishes was strongly constrained and thereby limited the possible density interval associated with the superconducting phase. This might ahve interesting consequences for the cooling history of NSs. We plan to investigate this with more realistic cooling simulations in future work.

The difference between the two approaches lies in the additional x3 term in the GDFM expression for the gi parameters. Here, the choice of different density-dependent parameters gi compared to that of Char et al. (2023), Scurto et al. (2024) is motivated by the need to avoid the irregular behavior of the symmetry energy induced by the cubic term, as observed by Scurto et al. (2024).

See Appendix B of Montefusco et al. (2025) for a detailed description of how this constraint is implemented.

A complete Bayesian inference of the NMPs starting directly from nuclear observables was recently performed by Klausner et al. (2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Laboratory for Advanced Computing at the University of Coimbra for providing computing resources that have contributed to the research results reported within this paper. URL: https://www.uc.pt/lca. L.S. acknowledges the PhD grant 2021.08779.BD (FCT, Portugal) with DOI identifier 10.54499/2021.08779.BD. Partial support from the IN2P3 Master Project NewMAC and the ANR project GW-HNS (ANR-22-CE31-0001-01). This work was also partially supported by national funds from FCT (Fundaȩão para a Ciância e a Tecnologia, I.P, Portugal) under projects UIDB/04564/2020 and UIDP/04564/2020, with DOI identifiers 10.54499/UIDB/04564/2020 and 10.54499/UIDP/04564/2020, respectively, and the project 2022.06460.PTDC with the associated DOI identifier 10.54499/2022.06460.PTDC. H.P. acknowledges the grant 2022.03966.CEECIND (FCT, Portugal) with DOI identifier 10.54499/2022.03966.CEECIND/CP1714/CT0004.

References

- Abbott, B. P., Abbott, R., Abbott, T. D., et al. 2017a, ApJ, 848, L13 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, B. P., Abbott, R., Abbott, T. D., et al. 2017b, Phys. Rev. Lett., 119, 161101 [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, B. P., Abbott, R., Abbott, T. D., et al. 2019, Phys. Rev. X, 9, 011001 [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, D., Albataineh, H., Androic, D., et al. 2021, Phys. Rev. Lett., 126, 172502 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, D., Albataineh, H., Androic, D., et al. 2022, Phys. Rev. Lett., 129, 042501 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoniadis, J., Freire, P. C. C., Wex, N., et al. 2013, Science, 340, 6131 [Google Scholar]

- Bardeen, J., Cooper, L. N., & Schrieffer, J. R. 1957, Phys. Rev., 108, 1175 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beloin, S., Han, S., Steiner, A. W., & Page, D. 2018, Phys. Rev. C, 97, 015804 [Google Scholar]

- Benhar, O., & De Rosi, G. 2017, J. Low Temp. Phys., 189, 250 [Google Scholar]

- Beznogov, M. V., & Yakovlev, D. G. 2014, MNRAS, 447, 1598 [Google Scholar]

- Carreau, T., Gulminelli, F., & Margueron, J. 2019, Eur. Phys. J. A, 55, 188 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chamel, N., & Haensel, P. 2008, Liv. Rev. Relat., 11, 10 [Google Scholar]

- Char, P., Mondal, C., Gulminelli, F., & Oertel, M. 2023, Phys. Rev. D, 108, 103045 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, D., Salmi, T., Vinciguerra, S., et al. 2024a, ApJ, 971, L20 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, D., Salmi, T., Vinciguerra, S., et al. 2024b, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13766753 [Google Scholar]

- Das, H. C., Wei, J.-B., Burgio, G. F., & Schulze, H. J. 2024, Phys. Rev. D, 109, 123018 [Google Scholar]

- Davis, P. J., Thi, H. D., Fantina, A. F., et al. 2024, A&A, 687, A44 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh Thi, H., Fantina, A. F., & Gulminelli, F. 2021, Eur. Phys. J. A, 57, 296 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drischler, C., Hebeler, K., & Schwenk, A. 2019, Phys. Rev. Lett., 122, 042501 [Google Scholar]

- Drischler, C., Holt, J. W., & Wellenhofer, C. 2021, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci., 71, 403 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drissi, M., & Rios, A. 2022, Eur. Phys. J. A, 58, 90 [Google Scholar]

- Dutra, M., Lourenço, O., Avancini, S. S., et al. 2014, Phys. Rev. C, 90, 055203 [Google Scholar]

- Essick, R., Landry, P., & Holz, D. E. 2020, Phys. Rev. D, 101, 063007 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin, M., Raduta, A. R., Avancini, S., & Providência, C. 2021, Phys. Rev. D, 103, 083004 [Google Scholar]

- Gaitanos, T., Di Toro, M., Typel, S., et al. 2004, Nucl. Phys. A, 732, 24 [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi, S., Palkanoglou, G., Carlson, J., Gezerlis, A., & Schmidt, K. E. 2022, Condens. Mat., 7, 19 [Google Scholar]

- Gogelein, P., van Dalen, E. N. E., Fuchs, C., & Muther, H. 2008, Phys. Rev. C, 77, 025802 [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson, E., Pethick, C., & Epstein, R. 1983, ApJ, 272, 286 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.-Z., Tang, S.-P., & Fan, Y.-Z. 2023, ApJ, 950, 77 [Google Scholar]

- Hebeler, K., Lattimer, J. M., Pethick, C. J., & Schwenk, A. 2013, ApJ, 773, 11 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Huth, S., Wellenhofer, C., & Schwenk, A. 2021, Phys. Rev. C, 103, 025803 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Klahn, T., Blaschke, D., Typel, S., et al. 2006, Phys. Rev. C, 74, 035802 [Google Scholar]

- Klausner, P., Colò, G., Roca-Maza, X., & Vigezzi, E. 2025, Phys. Rev. C, 111, 014311 [Google Scholar]

- Landry, P., & Essick, R. 2019, Phys. Rev. D, 99, 084049 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Landry, P., Essick, R., & Chatziioannou, K. 2020, Phys. Rev. D, 101, 123007 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Levenfish, K. P., & Yakovlev, D. G. 1994, Astron. Lett., 20, 43 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom, L. 2010, Phys. Rev. D, 82, 103011 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom, L., & Indik, N. M. 2012, Phys. Rev. D, 86, 084003 [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom, L., & Indik, N. M. 2014, Phys. Rev. D, 89, 064003 [Erratum: Phys. Rev. D 93, 129903 (2016)] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B., Greco, V., Baran, V., Colonna, M., & Di Toro, M. 2002, Phys. Rev. C, 65, 045201 [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo, U., & Schulze, H. J. 2001, Lect. Notes Phys., 578, 30 [Google Scholar]

- Lynn, J. E., Tews, I., Carlson, J., et al. 2016, Phys. Rev. Lett., 116, 062501 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik, T., Agrawal, B. K., & Providência, C. 2022, Phys. Rev. C, 106, L042801 [Google Scholar]

- Malik, T., Pais, H., & Providência, C. 2024, A&A, 689, A242 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron, J., & Gulminelli, F. 2019, Phys. Rev. C, 99, 025806 [Google Scholar]

- Margueron, J., Hoffmann Casali, R., & Gulminelli, F. 2018a, Phys. Rev. C, 97, 025806 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Margueron, J., Hoffmann Casali, R., & Gulminelli, F. 2018b, Phys. Rev. C, 97, 025805 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marino, A., Dehman, C., Kovlakas, K., et al. 2024, Nat. Astron., 8, 1020 [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, D. P., & Providência, C. 2004, Phys. Rev. C, 70, 058801 [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. C., Lamb, F. K., Dittmann, A. J., et al. 2019, ApJ, 887, L24 [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M. C., Lamb, F. K., Dittmann, A. J., et al. 2021, ApJ, 918, L28 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, C., Antonelli, M., Gulminelli, F., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 524, 3464 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Montefusco, G., Antonelli, M., & Gulminelli, F. 2025, A&A, 694, A150 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Page, D., & Applegate, J. H. 1992, ApJ, 394, L17 [Google Scholar]

- Page, D., Lattimer, J. M., Prakash, M., & Steiner, A. W. 2004, ApJS, 155, 623 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pais, H., Santos, A., & Providência, C. 2009, Phys. Rev. C, 80, 045808 [Google Scholar]

- Pais, H., Chiacchiera, S., & Providência, C. 2015, Phys. Rev. C, 91, 055801 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou, G. E., Mavrommatis, E., Moustakidis, C., & Clark, J. W. 2017, Eur. Phys. J. A, 53, 96 [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J. M., Chamel, N., Potekhin, A. Y., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 481, 2994 [Erratum: MNRAS 486, 768 (2019)] [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Potekhin, A. Y., & Chabrier, G. 2018, A&A, 609, A74 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Potekhin, A. Y., Pons, J. A., & Page, D. 2015, Space Sci. Rev., 191, 239 [Google Scholar]

- Potekhin, A. Y., Gusakov, M. E., & Chugunov, A. I. 2023, MNRAS, 522, 4830 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, M., Prakash, M., Lattimer, J. M., & Pethick, C. J. 1992, ApJ, 390, L77 [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, M., Reddy, S., Lattimer, J. M., & Ellis, P. J. 1996, Acta Phys. Hung. A, 4, 271 [Google Scholar]

- Providência, C., Fortin, M., Pais, H., & Rabhi, A. 2019, Front. Astron. Space Sci., 6, 00013 [Google Scholar]

- Read, J. S., Lackey, B. D., Owen, B. J., & Friedman, J. L. 2009, Phys. Rev. D, 79, 124032 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Riley, T. E., Watts, A. L., Bogdanov, S., et al. 2019, ApJ, 887, L21 [Google Scholar]

- Riley, T. E., Watts, A. L., Ray, P. S., et al. 2021, ApJ, 918, L27 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Roca-Maza, X., Vinas, X., Centelles, M., Ring, P., & Schuck, P. 2011, Phys. Rev. C, 84, 054309 [Erratum: Phys. Rev. C 93, 069905 (2016)] [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sammarruca, F. 2023, Phys. Rev. C, 108, 044310 [Google Scholar]

- Santos, L. G. T. D., Malik, T., & Providência, C. 2025, Phys. Rev. C, 111, 035805 [Google Scholar]

- Scurto, L., Pais, H., & Gulminelli, F. 2023, Phys. Rev. C, 107, 045806 [Google Scholar]

- Scurto, L., Pais, H., & Gulminelli, F. 2024, Phys. Rev. D, 109, 103015 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sedrakian, A., & Clark, J. W. 2019, Eur. Phys. J. A, 55, 167 [Google Scholar]

- Serot, B. D., & Walecka, J. D. 1986, Adv. Nucl. Phys., 16, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Tews, I., Krüger, T., Hebeler, K., & Schwenk, A. 2013, Phys. Rev. Lett., 110, 032504 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tews, I., Lattimer, J. M., Ohnishi, A., & Kolomeitsev, E. E. 2017, ApJ, 848, 105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thi, H. D., Carreau, T., Fantina, A. F., & Gulminelli, F. 2021a, A&A, 654, A114 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Thi, H. D., Mondal, C., & Gulminelli, F. 2021b, Universe, 7, 373 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Dalen, E. N. E., Fuchs, C., & Faessler, A. 2005, Phys. Rev. Lett., 95, 022302 [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M., Audi, G., Kondev, F. G., et al. 2017, Chin. Phys. C, 41, 030003 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., Tong, H., Zhao, Q., et al. 2023, Phys. Rev. C, 108, L031303 [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J. B., Burgio, G. F., & Schulze, H. J. 2019, MNRAS, 484, 5162 [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.-B., Burgio, F., & Schulze, H.-J. 2020, Universe, 6, 115 [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev, D. G., Levenfish, K. P., & Shibanov, Y. A. 1999, Phys. Usp., 42, 737 [Google Scholar]

- Yakovlev, D. G., Gnedin, O. Y., Gusakov, M. E., et al. 2005, Nucl. Phys. A, 752, 590 [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Details of the RMF Formalism

In this appendix, we provide a detailed exposition of the formalism employed in the construction of the EoS models used in this study. We start by showing the terms in Eq. (1). The second term in Eq. (1) represents an ideal Fermi gas of muons and electrons,

The mesonic terms in the Lagrangian are given by the standard expressions

with the tensors written as

The nucleon-meson couplings gi are given by the expression in Eq. 5. The coupling parameters uniquely define each model of the two sets (Set A and Set B) used in this study. The way these parameters (together with some of the NMPs) are generated is detailed in Appendix B.

In the mean-field approximation, the mesonic fields are replaced by their ground state expectation value, so that for each meson only the third vector component and the zeroth isovector component are different from zero. These components must satisfy the classical Euler-Lagrange equations:

In the above equations, n = nn + np is the total baryon number density, ns = nsn + nsp is the total scalar density, while n3 = np − nn and ns3 = nsp − nsn. The two scalar densities are obtained as

kFi being the Fermi momentum of neutrons (i = n) and protons (i = p). The nucleonic chemical potentials are given by

where i = p, n, the plus sign is for protons and the minus is for neutrons and where ΣR is the rearrangement term arising from the density dependence of the couplings:

Finally, the energy density and pressure are given by

and

where

and

Charge neutrality ρp = ρe + ρμ and the weak equilibrium conditions

complete the equations set for homogeneous matter in the core.

For the inhomogeneous crust, we follow the same prescription as in Scurto et al. (2024). In the outer crust, the BSK22 equation of state Pearson et al. (2018) is adopted for all equations of state in our sets, while in the inner crust, a CLD approximation consistent with the RMF formalism used for the core is employed Pais et al. (2015), Scurto et al. (2023). In this CLD formalism, each Wigner-Seitz cell is composed of a constant electron background of energy density ℰL, a high-density (“cluster”) part, labeled I, and a low-density (“gas”) part, labeled II, both considered as homogeneous portions of nuclear matter at respective baryon densities nI and nII.

The equilibrium configuration of the two phases is determined by minimizing the energy density of the cell,

which includes the surface and Coulomb terms. The minimization of ℰ is performed with respect to four variables: the linear size of the cluster, Rd, the baryonic density nI, the proton density npI of the high-density phase, and its volume fraction f. To reduce computational time, we consider only spherical clusters, as previous studies Thi et al. (2021a) have shown that the inclusion of exotic geometries “pasta” phases) has a minor effect on both the EoS and the crust-core transition point. The Coulomb and surface terms in Eq. (A.22) are given by

where

and the surface tension σ reads

Here, yp, I is the proton fraction (yp = np/n) of the dense phase, while the parameters σ0 and b are optimized for each model, through a fit over the measurements of the nuclear masses Wang et al. (2017), as previously done in Carreau et al. (2019), Dinh Thi et al. (2021), Thi et al. (2021b), Scurto et al. (2024).

Appendix B: Definitions, distributions and analytical expressions for the NMPs

In this appendix, we give the definition for the NMPs, and show their posterior distributions when the constraints are applied. We also detail their analytical expressions, including the contribution of the δ meson, used in the construction of the prior.

We start by defining the saturation energy Esat as the minimum of the energy per baryon in symmetric nuclear matter, and the saturation density nsat as the baryon density at which this minimum occurs. The symmetry energy is defined as

with ϵ the energy per baryon as a function of the total baryonic density n and the proton fraction yp, such that Esym = 𝒮(nsat). All the other NMPs are obtained as derivatives:

with k = 2 for Ksat, k = 3 for Qsat, and k = 4 for Zsat, and

with k = 1 for Lsym, k = 2 for Ksym, k = 3 for Qsym, and k = 4 for Zsym.

In Table B.1 we report the mean values and standard deviations adopted in the Bayesian analysis to constrain some of these parameters, based on the results of various nuclear physics experiments. We then examine how the distributions of the NMPs are modified by the imposed constraints. Fig. B.1 shows the prior and posterior distributions of the NMPs for both sets. The distributions of the isoscalar sector parameters are nearly identical, as expected from the isovector nature of the δ meson. In contrast, significant differences appear in the symmetry NMPs, most notably in the distributions of Lsym and Ksym.

|

Fig. B.1. Marginalized posterior of the NMPs for the prior (dotted) and posterior (solid) distributions for Set A (blue) (without δ meson) and Set B (green) (with δ meson). |

Values of the mean and standard deviation for the NMPs used in the evaluation of the constraint on these parameters, taken from Margueron et al. (2018b).

We observe that the presence of the δ meson in Set B leads to broader distributions. Additionally, for both Lsym and Ksym, the peak of the distribution shifts to lower values compared to Set A. The results for Set B align well with those reported in Scurto et al. (2024), indicating that the inclusion of the δ meson provides the same degree of flexibility previously achieved through a more complex density-dependent couplings. We also find that the constraints imposed in the posterior calculation tend to prefer lower values for both Lsym and Ksym, in agreement with Scurto et al. (2024).

Finally, we show here the analytical expressions for the lower order NMPs, used for the generation of our two sets, including the contribution of the δ meson.

These analytical expressions were used in the generation of the initial sets of models. In particular, each equation of state in each set is generated by sampling a subset of the coupling parameters from uniform distributions, together with some of the NMPs. The generated coupling parameters are chosen as the ones that show the smallest correlation with the lower order NMPs. In Table B.2 we show the ranges used for the generation of the parameters. The missing coupling parameters are then obtained by imposing simultaneously the values of the generated NMPs in the analysical expressions below, as done in (Scurto et al. 2024). Due to the isovector nature of the δ, the equation for the NMPs in the isoscalar sector remains unchanged for the equations shown in Dutra et al. (2014), Scurto et al. (2024), which we report here:

The minimum and maximum values of the uniform prior distributions of the nuclear matter properties and couplings for Sets A and B.

In the above, the kinetic contributions to the energy per baryon are given by Ekin, i = ℰkin, i/ni, where ℰkin, i is given in the previous section. We remind that Eq. B.5 connects the saturation density to the couplings by imposing the vanishing of pressure.

The equations for the NMPs in the isovector sector, on the other hand, are significantly modified by the presence of the new meson. We report them in the following, including also the equation for Ksym for completion, even if it was not used for the construction of the prior. For Jsym we have:

where

For Lsym we have:

where

Finally, for Ksym we have:

where

and

with

Appendix C: Predictions on the gap scaling parameters

In this appendix, we explore the effect of the hypothetical constraint on the dUrca threshold on the two scaling parameters used in the expression of the pairing gap shown in Eq. 11.

In Fig. C.1 and C.2, we show the resulting distributions for sn and sΔ. For sn, we find that in the T = 108 K and T = 109 K cases, both the “Always” and “Sometimes” scenarios impose strong constraints, favoring lower values of sn, as expected. The results for Set A and Set B are largely similar, with the main difference being the shape of the “Never” distribution at the highest temperature. This difference arises because Set A contains fewer models with high ndUrca, so in this set the “Never” distribution is dominated by models with larger nΔ, which correspond to higher values of sn.

|

Fig. C.1. Marginalized posterior of the sn parameter for Set A (top row) and Set B (bottom row) and for the three considered star temperatures, namely T = 108K (left panels),T = 109K (central panels) and T = 1010K (right panels). We show the results for the three assumptions on the threshold “Always” (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙), “Sometimes” (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙) and “Never” (MdUrca > 2.1 M⊙) (blue dotted, orange dashed and green dash-dotted, respectively). |

|

Fig. C.2. Marginalized posterior of the sΔ parameter for Set A (top row) and Set B (bottom row) and for the three considered star temperatures, namely T = 108K (left panels), T = 109K (central panels) and T = 1010K (right panels). We show the results for the three assumptions on the threshold “Always” (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙), “Sometimes” (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙) and “Never” (MdUrca > 2.1 M⊙) (blue dotted, orange dashed and green dash-dotted, respectively). |

For sΔ, the T = 108 K case does not provide any significant constraints, as the density at which the gap vanishes is independent of sΔ. At the intermediate temperature, the constraint on sΔ is noticeably weaker compared to that on sn, with the entire parameter range being included in the distributions for all three dUrca scenarios. The peak observed in the “Never” distribution at the highest temperature follows the same pattern as in the sn distribution.

The stronger effect of the constraint observed in the case of sn compared to the one on sΔ explains the results in Fig. 10, where the density range in which the gap is different from zero is significantly more constrained than the value of its peak.

All Tables

Values of the mean and standard deviation for the NMPs used in the evaluation of the constraint on these parameters, taken from Margueron et al. (2018b).

The minimum and maximum values of the uniform prior distributions of the nuclear matter properties and couplings for Sets A and B.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Energy per particle of pure neutron matter as a function of the density for the χ-EFT constraint we used (blue band), of the calculations shown in Fig. 1 of Huth et al. (2021) (gray band), and of the unitary gas limit (solid red line). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Marginalized posterior of the maximum mass (first panel), the central density of the most massive star (second panel), the radius (third panel), the tidal deformability (fourth panel), and the central density (fifth panel) of an NS with a mass of 1.4 M⊙ for the prior (dotted) and posterior (solid) distributions for Set A (blue) and Set B (green). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. 90% quantiles for the distribution of the mass as a function of the radius (top panels) and as a function of the tidal deformability (bottom panels) for the prior (left) and posterior (right) distributions for Set A (blue) and Set B (green). In the M − R plots, we also show the 68% and 90% quantiles for the three NICER constraints. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. 68%, 95%, and 99% quantiles for the distribution of the proton fraction as a function of the baryonic density for the prior (left) and posterior (right) distributions for Set A (top) and Set B (bottom). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. 68%, 95%, and 99% quantiles for the posterior distribution of the ratio of the neutron and proton Dirac effective masses as a function of the baryonic density of purely neutron matter for Set B. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Marginalized posterior of the mass at which the dUrca threshold is met (left) and the 2D marginalized posterior for the baryonic density and proton fraction for the same threshold for the prior (dotted) and posterior (solid) distributions for Set A (black) and Set B (blue). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. 68% (blue) 95% (green), and 99% (brown) quantiles for the 2D posterior distributions of Jsym (left), Lsym (center), and Ksym (right) with MdUrca for Set A (top row) and Set B (bottom row). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Marginalized posterior of the astrophysical observables shown in Fig. 2 for Set A (top row) and Set B (bottom row). We show the results for the posterior without any assumption on the dUrca threshold (solid black line) as well as those including the three assumptions on the threshold Always (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙), Sometimes (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙), and Never (MdUrca > 2.1 M⊙) (dotted blue line, dashed orange line, and dash-dotted green line, respectively). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9. 68% (blue) 95% (green), and 99% (brown) quantiles for the posterior distributions of the pairing gap as a function of the baryonic density of beta-equilibrated matter for Set B. We show the results for the posterior without assumptions on the dUrca threshold (top left), as well as when the Always (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙) assumption for the dUrca threshold is made for a star at T = 108 K (top right), T = 109 K (bottom left), and T = 1010 K (bottom right). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10. 68% (blue) 95% (green), and 99% (brown) quantiles for the posterior distributions of the pairing gap as a function of the baryonic density of beta-equilibrated matter for Set B. We show the results for the posterior without assumptions on the dUrca threshold (top left), as well as when the Sometimes (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙) assumption for the dUrca threshold is made for a star at T = 108 K (top right), T = 109 K (bottom left), and T = 1010 K (bottom right). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.1. Marginalized posterior of the NMPs for the prior (dotted) and posterior (solid) distributions for Set A (blue) (without δ meson) and Set B (green) (with δ meson). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. C.1. Marginalized posterior of the sn parameter for Set A (top row) and Set B (bottom row) and for the three considered star temperatures, namely T = 108K (left panels),T = 109K (central panels) and T = 1010K (right panels). We show the results for the three assumptions on the threshold “Always” (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙), “Sometimes” (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙) and “Never” (MdUrca > 2.1 M⊙) (blue dotted, orange dashed and green dash-dotted, respectively). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. C.2. Marginalized posterior of the sΔ parameter for Set A (top row) and Set B (bottom row) and for the three considered star temperatures, namely T = 108K (left panels), T = 109K (central panels) and T = 1010K (right panels). We show the results for the three assumptions on the threshold “Always” (MdUrca < 1.3 M⊙), “Sometimes” (1.3 M⊙ ≤ MdUrca ≤ 2.1 M⊙) and “Never” (MdUrca > 2.1 M⊙) (blue dotted, orange dashed and green dash-dotted, respectively). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{L} _N=\bar{\psi } \left[\gamma _\mu (i \partial ^\mu -g_\omega V^\mu -\frac{g_\rho }{2}\boldsymbol{\tau }\cdot \mathbf b ^\mu )-M^*\right]\psi , \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq2.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \mathcal{L} _L=\sum _{l=e,\mu }\bar{\psi }_l \left[i\gamma _\mu \partial ^\mu -m_l\right] \psi _l. \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq13.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned}&E_{sat}= \Bigg [E_{kin,n}+E_{kin,p}+ \nonumber \\&\qquad \quad +\Bigg (\frac{1}{2}m_\sigma ^2\phi _0^2 +\frac{1}{2}m_\omega ^2\omega _0^2+\frac{1}{2}m_\rho ^2b_{3,0}^2\Bigg ) \frac{1}{n}-M\Bigg ]\Bigg \vert _{n=n_{sat},n_3=0} \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq42.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned}&P_{sat}=0=\Bigg [P_{kin,n} + P_{kin,p}-\frac{1}{2}m_\sigma ^2\phi _0^2+\frac{1}{2}m_\omega ^2\omega _0^2+\nonumber \\&\qquad \qquad \qquad \quad +\frac{1}{2}m_\rho ^2b_{3,0}^2+\rho \Sigma _R\Bigg ]\Bigg \vert _{n=n_{sat},n_3=0} \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq43.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned}&K_{sat}=9\Bigg [n\frac{\partial \Sigma _R}{\partial n} +\frac{2g_\omega n^2}{m_\omega ^2}\frac{\partial g_\omega }{\partial n} +\frac{g_\omega ^2 n}{m_\omega ^2}\nonumber \\&\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \frac{k_F^2}{3E_F}+\frac{n M^*}{E_F}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg ]\Bigg \vert _{n=n_{sat},n_3=0} \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq44.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} J_{sym}=\Bigg [\frac{k_F^2}{6E_F}+\frac{g_\rho ^2}{8m_\rho ^2}\rho -J_{sym}^\delta \Bigg ] \Bigg \vert _{n=n_{sat},n_3=0} \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq45.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} C_\delta&=2\Bigg [2E_F\Bigg (1+\Bigg (\frac{g_\delta }{m_\delta }\Bigg )^2X_\delta \Bigg )\frac{\partial E_F}{\partial n}+E_F^2\Bigg (\frac{g_\delta }{m_\delta }\Bigg )^2\nonumber \\&\Bigg (\Bigg (\frac{2}{g_\delta }\frac{\partial g_\delta }{\partial n}+\frac{2}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg ) X_\delta +\frac{k_F^2}{E_F^3}\Bigg (1-\frac{3n}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg )\Bigg )\Bigg ]\nonumber \\&\Bigg [2E_F^2\Bigg (1+\Bigg (\frac{g_\delta }{m_\delta }\Bigg )^2X_\delta \Bigg )\Bigg ]^{-1}. \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq51.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned}&K_{sym}^\rho =-\frac{\pi ^2}{12{E_F^*}^3k_F}\left(\frac{\pi ^2}{k_F} + 2M^*\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\right) - \frac{\pi ^4}{12E_F^*k_F^4} +\frac{g_\rho }{2m_\rho ^2} \frac{\partial g_\rho }{\partial n}\nonumber \\&-\Bigg [\frac{\pi ^4}{24{E_F^*}^3k_F^2} - \frac{k_F\pi ^2}{8{E_F^*}^5}\left(\frac{\pi ^2}{k_F} + 2M^*\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\right)\Bigg ] \cdot \Bigg (1 + \frac{2M^*k_F}{\pi ^2}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg )\nonumber \\&+ \frac{n}{4m_\rho ^2}\left(\frac{\partial g _\rho }{\partial n}\right)^2-\frac{k_F\pi ^2}{12{E_F^*}^3}\cdot \Bigg [\frac{M^*}{k_F^2}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n} + \frac{2k_F}{\pi ^2}\left(\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\right)^2 +\nonumber \\&\frac{2k_F M^*}{\pi ^2}\frac{\partial ^2 M^*}{\partial n^2}\Bigg ]+\frac{g_\rho n}{4m_\rho ^2}\frac{\partial ^2 g_\rho }{\partial n^2} \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq53.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} K_{sym}^\delta =J_{sym}^\delta \Bigg \{A_\delta ^2+2\Bigg [\frac{1}{g_\delta }\frac{\partial ^2g_\delta }{\partial n^2}-\Bigg (\frac{1}{g_\delta }\frac{\partial g_\delta }{\partial n}\Bigg )^2\Bigg ] +2D_\delta -B_\delta ^2+C_\delta ^2-E_\delta \Bigg \}, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq54.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned}&E_\delta =2\Bigg [2\Bigg (\frac{\partial E_F}{\partial n}\Bigg )^2\Bigg (1 +\Bigg (\frac{g_\delta }{m_\delta }\Bigg )^2X_\delta \Bigg )+2E_F\Bigg (1 +\Bigg (\frac{g_\delta }{m_\delta }\Bigg )^2X_\delta \Bigg ) \frac{\partial ^2 E_F}{\partial n^2}\nonumber \\&+4E_F\frac{\partial E_F}{\partial n}\Bigg (\frac{g_\delta }{m_\delta }\Bigg )^2 \Bigg (\Bigg (\frac{2}{g_\delta }\frac{\partial g_\delta }{\partial n}+\frac{2}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg ) X_\delta +\frac{k_F^2}{E_F^3}\Bigg (1-\frac{3n}{M^*} \frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg )\Bigg )\nonumber \\&+2E_F^2\Bigg (\frac{g_\delta }{m_\delta }\Bigg )^2F_\delta \Bigg ] \Bigg [2E_F^2\Bigg (1+\Bigg (\frac{g_\delta }{m_\delta } \Bigg )^2X_\delta \Bigg ]^{-1},\end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq56.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned}&F_\delta =X_\delta \Bigg (\frac{1}{g_\delta } \frac{\partial ^2g_\delta }{\partial n^2} +\Bigg (\frac{1}{g_\delta } \frac{\partial g_\delta }{\partial n}\Bigg )^2\Bigg ) +2\frac{1}{g_\delta } \frac{\partial g_\delta }{\partial n} \Bigg (X_\delta \frac{2}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\nonumber \\&+\frac{k_F^2}{E_F^3}\Bigg (1-\frac{3n}{M^*} \frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg )\Bigg )+\frac{1}{2} \Bigg [2X_\delta \Bigg (\frac{1}{M^*}\frac{\partial ^2 M^*}{\partial n^2}-\frac{1}{M^{*2}}\Bigg (\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg )\Bigg )\nonumber \\&+\frac{2}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg (X_\delta \frac{2}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n} +\frac{k_F^2}{E_F^3}\Bigg (1-\frac{3n}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg )\Bigg )\nonumber \\&-\frac{3k_F^2}{E_F^3}\Bigg (\frac{1}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}+\frac{n}{M^*}\frac{\partial ^2 M^*}{\partial n^2} -\frac{n}{M^{*2}}\Bigg (\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg )^2\Bigg ) +\Bigg (1-\frac{3n}{M^*}\frac{\partial M^*}{\partial n}\Bigg )\nonumber \\&\Bigg (\frac{2k_F}{E_F^3}\frac{\partial k_F}{\partial n}-\frac{3k_F^2}{E_F^4}\frac{\partial E_F}{\partial n}\Bigg )\Bigg ] \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54729-25/aa54729-25-eq57.gif)