| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A249 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557647 | |

| Published online | 17 December 2025 | |

Ion-molecule routes towards cycles in TMC-1

An automated study of the C2H4 + CH2CCH+ reaction

Departamento de Astrofísica Molecular, Instituto de Física Fundamental (IFF-CSIC), C/ Serrano 123, 28006 Madrid, Spain

★ Corresponding authors: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

10

October

2025

Accepted:

31

October

2025

Cyclopentadiene (c-C5H6) is considered a key molecule in the formation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the interstellar medium (ISM). The synthesis of PAHs from simpler precursors is known as the “bottom-up” theory, which, so far, has been dominated by reactions between organic radicals. However, this mechanism struggles to account for the origin of the smallest cycles themselves. However, it struggles to account for the origin of the smallest cycles themselves. Ion-molecule reactions emerge as promising alternative pathways to explain the formation of these molecules. We investigated the reaction network of the main ionic precursor of cyclopentadiene, c-C5H7+. To this end, we established an integrated protocol that combines astrochemical modelling to identify viable formation routes under cold ISM conditions, automated reaction path searches, and kinetic simulations to obtain accurate descriptions of the reaction pathways and reliable rate constants. In particular, we examined the reaction between ethylene (C2H4) and the linear propargyl cation (CH2CCH+). Our results reveal that the formation of c-C5H7+ by radiative association is inefficient, contrary to our initial expectations. Instead, the system predominantly evolves through bimolecular channels yielding c-C5H5+ and CH3CCH2+, with the formation of c-C5H5+; this offers new insights into the reactivity that supports molecular growth in the ISM.

Key words: astrochemistry / methods: numerical / ISM: molecules / ISM: individual objects: TMC-1

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were determined to be plausible carriers of unidentified infrared emission bands in the early 1980s (Léger & Puget 1984; Allamandola et al. 1985); at that time, they were hypothesized to be present in UV-irradiated interstellar regions. The compatibility between PAHs and this set of bands, believed to be due to the unique properties of PAHs - for example charge regulators or interstellar catalysts - makes them arguably the most important family of interstellar molecules (Tielens 2005). The recent detection of a large number of PAHs in the Taurus Molecular Cloud (TMC-1; Cernicharo et al. 2021a; McGuire et al. 2021a; Cernicharo et al. 2024; Wenzel et al. 2024; Wenzel et al. 2025a,b; Cabezas et al. 2025) has shaken up the astrochemical community, which is still discussing the implications of this large reservoir, and opens a new window into the chemistry of complex molecules in the interstellar medium (ISM). The chemical processes leading to PAH formation is a widely debated subject (Kaiser et al. 2003; Joblin & Cernicharo 2018; Thomas et al. 2019; García de la Concepción et al. 2023; Goettl et al. 2025b), and there is still no satisfactory explanation of how they form in such cold and UV-shielded environments. Among the proposed mechanisms, the bottom-up scenario for molecular mass growth postulates that small hydrocarbons are first synthesized and then grow into larger structures (Agúndez et al. 2025; Goettl et al. 2025a,b; Castiñeira Reis et al. 2024).

Simple molecules such as benzene (c-C6H6) and cyclopentadiene (c-C5H6) are likely building blocks in the formation of larger aromatic hydrocarbon cycles. However, the formation of these first rings in the ISM is not yet fully understood. Therefore, an exhaustive search for new routes that could lead to the formation of these molecules is required. While neutral-neutral reactions have typically been invoked in the formation of interstellar cycles (Jones et al. 2011; Doddipatla et al. 2021; García de la Concepción et al. 2023; Yang et al. 2024a; Castiñeira Reis et al. 2024), these processes alone cannot account for the large abundances of interstellar PAHs found. In this context, ionmolecule reactivity, upon which most of the complexity build-up in cold environments is based, could explain the synthesis of aromatic cycles.

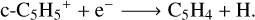

In molecular databases, the formation of cyclopentadiene is proposed to proceed through the dissociative recombination of its ionic precursor, the cyclopentadienyl cation (c-C5H7+), with electrons:

(1)

(1)

This represents a common pathway to increasingly complex carbon-bearing molecules, although most branching ratios for the possible neutral products are undetermined (Herbst 2021). This mechanism is analogous to that proposed to synthesize benzene (McEwan et al. 1999; Woods et al. 2002), whose presence in cold dense clouds is inferred from the detection of the cyano derivative (McGuire et al. 2018; Cooke et al. 2020). We note that the route to the formation of benzene has recently been questioned (Kocheril et al. 2025) and that the debate continues at the time of writing (Loison et al. 2025).

Cyclopentadiene was recently detected in the cold dark cloud TMC-1, alongside ethynyl cyclopropenylidene (c-C3HCCH) and indene (c-C9H8), by Cernicharo et al. (2021a). However, the mechanisms underlying its formation from non-cyclic hydrocarbon precursors remains under discussion (Yang et al. 2024b; Zhang et al. 2025), and current chemical models are unable to explain its observed abundance (McGuire et al. 2021b; Cernicharo et al. 2022). Determining the mechanisms responsible would inform theories of molecular mass growth in interstellar environments.

Returning to c-C5H7+, and according to the Anicich review on bimolecular gas phase cation-molecule reaction kinetics (Anicich 2003), the reaction between the propargyl cation (CH2CCH+) and ethylene (C2H4) is one of the few reactions that have been experimentally studied and reported to produce c-C5H7+ (Smyth et al. 1982). Incorporating this reaction into chemical networks has been demonstrated to improve the description of c-C5H6 in TMC-1 (Cernicharo et al. 2022). Said reaction also leads to C5H5+ + H2, but the branching ratio for the products is unknown. Ethylene has been detected in circumstellar gas surrounding the carbon-rich star IRC+10216 (Betz 1981; Fonfría et al. 2017), and its cyano derivative vinyl cyanide (CH2CHCN) was first observed in TMC-1 by Matthews & Sears (1983) and towards IRC+10216 (Agúndez et al. 2008), among several other sources. On the other hand, the propargyl cation presents two isomeric forms: linear (CH2CCH+) and cyclic (c-C3H3+). In the present work, we focus on CH2CCH+, which was recently discovered in TMC-1 (Silva et al. 2023). The cyclic isomer, which is more stable and less reactive, has not yet been detected in space since it holds a permanent dipole moment.

Our theoretical study focuses not only on verifying the formation of c-C5H7+ but also on determining how competitive the different channels of the reaction are. The study of ion-molecule reactivity is often more complex than that of neutral-neutral reactions, which typically proceed through well-defined pathways such as the loss of H or CH3 (Heitkämper et al. 2022; Balucani et al. 1999, 2018). On the other hand, ion-molecule processes are not as straightforward as neutral-neutral ones, and the atomic rearrangement is difficult to predict with exactitude. To approach this problem, we employed an automated reaction discovery method that allowed us to explore the potential energy surface (PES) of the C2H4 + CH2CCH+ system in an unbiased manner and identify all the possible reaction pathways and products within an energy threshold. Our aim is to demonstrate the potential of an automated protocol to explore the reactivity of ion-molecule systems and to obtain trustworthy results that can be directly applied to astrochemical models. In this work, we automatically built the reaction network of the c-C5H7+ molecular formula. We began by inspecting potentially relevant ion-neutral reactions leading to c-C5H7+ aided by chemical models. We then carried out quantum chemical calculations and used automated reaction path exploration techniques to identify the viable reaction pathways.

2 Methodology

Exploring the PES of complex ion-molecule reactions is a challenging task where manual searches are highly prone to error. To overcome this, we employed an unbiased search for stationary points, an area of computational chemistry that has rapidly advanced in recent years (Sameera et al. 2016; Maeda et al. 2016; Maeda & Harabuchi 2021; Van de Vijver & Zádor 2020; Martínez-Núñez et al. 2021; Maeda et al. 2023a; Türtscher & Reiher 2023) Such methodologies have been even used to explore astrochemically relevant systems (Castiñeira Reis et al. 2024; Komatsu & Suzuki 2022; Komatsu & Furuya 2023). Among the most successful approaches is the artificial force-induced reaction (AFIR) method (Maeda et al. 2016), which applies artificial pushing and pulling forces between fragments to explore reactivity.

In this work, we used the AFIR method as implemented in the GRRM23 (Global Reaction Route Mapping) program (Maeda et al. 2013, 2023a,b). AFIR generates plausible reaction pathways by introducing attractive or repulsive forces within a molecule, and whenever a new stationary point on the PES is located it is added to the pool of candidate structures from which the search continues, ultimately building a global (or semiglobal, if constraints are applied) reaction network. To avoid excessive computational cost in high-energy regions, all simulations were terminated according to some predefined stopping criterions: (i) an upper energy threshold that corresponds to the energy of the reactants including zero-point energy (ZPE), and (ii) a convergence rule in which the search was stopped when last 30 explored paths did not update the lowest 15 local minima. The central parameter controlling the amount of energy introduced into the system is the collision parameter γ, which approximates the largest barrier that can be overcome in the search. To ensure an adequate exploration of stationary points, including bimolecular dissociation channels, we employed a value of γ = 400.0 kJ mol−1 for a single biasing force (AFIR function). This corresponds to the SC-AFIR method, where ‘SC’ (single component) indicates that the search starts from a potential well, in our case the lowest-energy structure formed by the barrier-less association of C2H4 and CH2CCH+ at long range. This initial association event was simulated separately using the MC-AFIR protocol (Maeda et al. 2018), where ‘MC’ (multi-component) indicates that the two fragments, C2H4 and CH2CCH+, were placed at long distance and pulled together by a single artificial force of γ = 100 kJ mol−1. A total of 100 sampling runs were performed in this stage, and the AFIR profiles confirmed the barrier-less insertion of the fragments. All AFIR searches were performed with GRRM23, interfaced with Gaussian16 (Frisch et al. 2016) for electronic structure calculations.

The SC-AFIR calculations are performed at the ωB97XD/6-31+G* level (Chai & Head-Gordon 2008; Hehre et al. 1972; Hariharan & Pople 1973), and, as indicated above, only considering exothermic and barrier-less pathways due to the low temperatures of TMC-1. Refinement calculations are performed using a higher level of theory to characterize the stationary points, optimizing them at the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD level (Weigend & Ahlrichs 2005; Rappoport & Furche 2010, in addition to the original references of the method included above), from which we also extracted the harmonic vibrational frequencies and ZPE corrections1. Finally, the electronic energies are corrected at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ level (Purvis & Bartlett 1982; Riplinger & Neese 2013; Guo et al. 2018; Woon & Dunning 1994; Papajak et al. 2011) using a tight localization scheme (tightpno in ORCA settings). Therefore, the method employed for all the refined stationary points presented in this work can be abbreviated as DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD.

Once the PES is explored and characterized, a kinetic investigation is performed to determine the rate constants for the different pathways. The theoretical approach to determining the global rate constants relies on the ab initio transition state-based master equation under a microcanonical formalism. To build the master equation, the Rice-Ramsperger-Kassel-Marcus theory is used to calculate the unimolecular elementary steps of the reaction. Furthermore, the barrier-less channels are modelled using the phase-space theory (Pechukas & Light 1965; Truhlar 1969), in which the long-range interaction between the reactants is described by a potential form V(r) of the type

(2)

(2)

The V(r) points were obtained from rigid potential energy scans at the MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory (Møller & Plesset 1934) between distances of 4 and 25 Â. The global rate constants are derived from the individual ones using the master equation formalism implemented in the MESS code (Miller & Klippenstein 2006; Georgievskii et al. 2013).

The protocol connecting the automated search of the PES to the kinetic analysis is unsupervised thanks to a combination of in-house Python routines for the analysis, construction and refinement of the PES. In brief, the stationary points of coming from the GRRM23 code are parsed, refined at a higher level of theory, with an on-the-fly construction of the MESS input file. The integration between the different stages of our simulation is carried out within our codes using the ASH library for atomistic simulations (Bjornsson 2022) interfaced with the ORCA (v6.0.1) code (Neese et al. 2020; Neese 2025). Figure 1 illustrates the methodology followed in this work, highlighting the integration of the automated reaction path search with the rate constants calculations through our own routines.

Finally, the rate constants for each bimolecular channel are fitted into the Arrhenius-Kooij equation:

(3)

(3)

where α, β, and γ are determined from fitting the calculated rate coefficients over a given temperature range to expression (3). This way, the equation can be easily implemented in chemical models.

|

Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of our automated protocol to explore the reaction network of ion-molecule systems. |

|

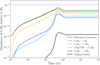

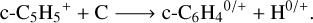

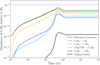

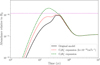

Fig. 2 Prediction of the relative abundance of cyclopentadiene (c-C5H6) as a function of time in the chemical model of TMC-1. The solid black line is the abundance predicted by the model without ion-molecule reactions, dashed lines represent how it is modified by including each of the reactions separately, and the solid green line is the total abundance when all the reactions from the dashed lines are included. The horizontal dotted line represents the observed abundance of cyclopentadiene in TMC-1, calculated from its column density (Cernicharo et al. 2021a). |

3 Results

3.1 Evaluating ion–molecule routes to synthesize c-C5H7+

As a prior step to carry out the reaction discovery calculations, we used astrochemical models to identify potentially relevant ion–molecule routes that could lead to the c-C5H7+ cation. The time-dependent gas-phase chemical model is built with the typical parameters of cold dense clouds, which consist on a particle density of H2 of 2 × 104 cm-3, a temperature of 10 K, a cosmicray ionization rate of 1.3 × 10-17 s-1 and a visual extinction of 30 mag (further details in Agúndez & Wakelam 2013). We adopted the so-called low-metal elemental abundances, where the abundance of oxygen is decreased to ensure a C/O ratio of 1, which results in a better overall agreement between calculated and observed abundances in the TMC-1 dark cloud. The chemical network is based on the gas-phase RATE22 network from the UMIST database (Millar et al. 2024).

We conducted a systematic investigation of ionic-neutral reactions leading to the formation of c-C5H7+ with atomic hydrogen (H) elimination, molecular hydrogen (H2) elimination, or through radiative association. Each route is evaluated in terms of the stability and abundance of the reactants in TMC-1, as well as whether it has been previously examined and documented in the Anicich index of bimolecular gas-phase cation-molecule reactions (Anicich 2003), thereby ensuring the feasibility of the reactions.

A rate coefficient of 10−9 cm3 s−1 is assumed for all the reactions lacking experimental data, but it should be emphasized that this procedure is only applied for the initial identification of the potential ion-molecule reactions leading to c-C5H7+ and it is not carried to the chemical models shown later in Sect. 4. This value is an upper limit for ion-molecule rate coefficients based on the measurements in Anicich (2003) so that if a reaction is not found to be relevant at this high rate, it can be discarded. If, on the other hand, a significant impact on the abundance of cyclopentadiene is observed, a more detailed study of the reaction will be performed to derive accurate rate coefficients and check the accuracy of the initial guess.

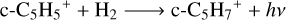

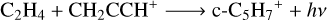

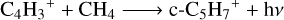

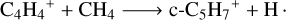

With the initial exploration of the reaction network we identified four key reactions that are able to reasonably reproduce the observed abundance of cyclopentadiene within the timescale of 105 to 106 years according to the chemical model (see Fig. 2). Cyclopentadiene is detected with a column density of (1.2 ± 0.3) ×1013 cm−2 (Cernicharo et al. 2021a), which results in a relative abundance to H2 of 1.2 × 10−9 adopting a column density of H2 of 1022 cm−2 for TMC-1 (Cernicharo & Guélin 1987). The model with the set of reactions that we selected predicts an abundance 4 × 10−10 at 105 years, which is in close agreement to the observed value. The four reactions that we identified for c-C5H7+ are the following:

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

After the formation of c-C5H7+, it is expected to suffer from electron recombination, i.e. c-C5H7+ + e- → c-C5H6 + H. The reactions (4)-(6) represent radiative associations, which consist on stabilization of the product by the emission of a photon. Radiative association is believed to play an important role in the growth of molecules in the cold ISM, where the densities can be too low for collisional stabilization (Herbst 2021). Of the four reactions, the reactions involving methane (CH4) are not considered in this work due to the presence of energy barriers of 6.1 kcal mol−1 for the C4H3+ + CH4 reaction and 9.0 kcal mol−1 for the C4H4 + CH4, obtained from MC-AFIR explorations. Therefore, we turned our attention to the study of reaction (5) and, to a lesser extent, reaction (4), for which we find kinetic entrance barriers and whose chemistry is investigated in more detail in Sect. 3.5.

3.2 Automatic exploration of the reaction network

The first step in the automated exploration of reaction (5) consists on identifying the exothermic association complexes between the reactants for each case, as the low temperatures of cold molecular clouds require the existence of open, barrier-less entrance channels for the reaction to proceed.

As previously noted in the Introduction, the propargyl cation in the C2H4+C3H3+ system can adopt either a linear (CH2CCH+) or a cyclic (c-C3H3+) structure. Among these, the cyclic isomer is the most stable form, lying by more than 30 kcal mol−1 below the linear isomer. Owing to this energy difference between isomers, c-C3H3+ is expected to be significantly less reactive and not to play a relevant role in this reaction. We performed preliminary calculations to see the bonding of both isomers with ethylene, finding that the c-C3H3+ + C2H4 association proceeds through activation energies, which cannot be overcome at the low temperatures of dense clouds. We could thus discard the cyclic isomer from the further research and only consider the CH2CCH+ + C2H4 reaction.

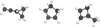

CH2CCH+ approaches C2H4 forming the triangular adduct CH2(CH2)CHcCH2 (referred to in the text as R1 and portrayed in Fig. 3) with a relative energy of -55.46 kcal mol−1. The long-range interaction potential for the CH2CCH+ + C2H4 association was calculated at the MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory. The results confirm the absence of energy barriers, in which the capture is characterized by a C4 coefficient of 25.97 au. According to phase-space theory, the C4 coefficient is related with the Langevin expression for the ion-apolar neutral reaction rate coefficients, predicting that the rates have no dependence on temperature (Woon & Herbst 2009).

From R1 we performed the automatic protocol described in Sect. 2. The final energy profile is shown in Fig. 4. The very complex PES landscape evinces that, after the formation of the initial R1 adduct, this excess of energy is used by the system to evolve through a series of intermediate wells and transition states among which three paths can be highlighted: the fall into the deepest well R2, which has a relative energy of -93.45 kcal mol−1 and corresponds to the most stable cyclic isomer of the c-C5H7+ ion, the dissociation of this well into c-C5H5+ and molecular hydrogen (H2) and the fragmentation from the well R3 into the allyl cation (CH3CCH2+) and acetylene (C2H2). When the system enters the stable well R2 it can be stabilized by emission of radiation or evolve to products (c-C5H5+ + H2) going through a submerged transition state and a post-reactant complex. The dissociation into CH3CCH2+ + C2H2 occurs directly from the well R3 by sequentially breaking two C-C bonds. To discern which pathways are more favoured, kinetic simulations are performed and detailed in Sect. 3.3. However, the presence of barrier-less, exothermic bimolecular pathways already indicates that radiative association will be a minor channel compared to bimolecular channels.

|

Fig. 3 From left to right: structures of R1, R2, and R3 (all of them isomeric forms of C5H7+). |

3.3 Rate constant derivation

The kinetic master equation is built considering the stationary points that are found during the automatic exploration of the PES (Fig. 4), all of them being accessible to the system at the low temperatures of TMC-1.

We focused on the rate constants for the two main, competitive pathways:

(8)

(8)

(9)

(9)

to which we should add the channel

(10)

(10)

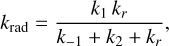

which represents the stabilization of the complex R2 by radiative association. The presence of very exothermic bimolecular channels greatly reduces the probability of radiative association (Herbst 2021) in comparison with the two bimolecular ones based in the following competition relation:

(11)

(11)

where k1 is the rate for the formation of the complex, k-1 is the rate for the dissociation of the complex back into reactants, k2 is the dissociation into new products and kr is the radiative emission rate. Then, the stabilization of the complex by emission of radiation depends on the competition between the re-dissociation and fragmentation into new products. An estimation of krad based on Tennis et al. (2021) and Herbst (1982) is derived in Appendix A, where we determine this channel to be non-competitive with the bimolecular ones with a krad ≤ 3.25 × 10−14 cm3 s−1.

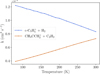

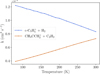

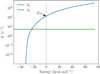

We computed the rate constants for reactions (8) and (9) in a range of temperatures from 80 to 300 K and a pressure of 10−7 atm to achieve the most realistic representation possible of the physical conditions of TMC-1. For reactions (8) and (9), the calculated rate constants are shown in Fig. 5 as a function of temperature. At the lowest temperature achievable in our system using the ab initio transition state-based master equation approach (80 K), the rate constant for the formation of c-C5H5+ is 1.2 × 10−9 cm3 s−1 and the one for the formation of CH3CCH2+ is 3.9 × 10−10 cm3 s−1. The rate constant at 80 K are still reasonable estimators of behaviour at lower temperature, especially considering that the capture Langevin rate should be temperature-independent at low temperatures2. The formation of c-C5H5+ is the dominant channel of the title reaction, with a branching ratio of 75.7% versus a 24.3% of C3H5+ at 80 K. This ratio shifts to 53.3% and 47.7%, respectively, at 300 K, but the formation of c-C5H5+ remains the main formation channel. The rate constants of both channels exhibit a significant correlation, in which the formation of CH3CCH2+ is favoured as the formation of c-C5H5+ is disfavoured with temperature. This may be due to the presence of a transition state with a low energy barrier in the complex PES.

In the experimental study by Smyth et al. (1982), the authors report the formation of C5H7+ and C5H5+ + H2 with a total rate constant of 1.1 × 10−9 cm3 s−1 at 300 K. Our calculations reveal a total rate coefficient of 1.6 × 10−9 cm3 s−1 at the same temperature, which is calculated as sum of the two competitive pathways (ktot = kc-C5H5+ + kCH3CCH2+). Despite the excellent agreement with the experimental rate constant of Smyth et al. (1982), a significant discrepancy arises from the products of the reaction found, as they do not report the formation of CH3CCH2+ + C2H2, which we find to be a significant channel. The reasons for the disagreement between theory and experiments are not known, and the explanation might be multi-causal. A possible source of disparity is the different residence times between experiments and theory. The total absence of the C2H2 + CH3CCH2+ channels prompt us to consider that secondary reactions involving these molecules might be occurring in the experimental setup, enlarging the total rate constant and including the formation of c-C5H7+. This is in contrast with our calculations that are equivalent to single collision experiments, and also to our results in Appendix A, where we use a reduced model to determine the rate constant for radiative association, finding it to be a channel about 4-5 orders of magnitude less efficient than bimolecu-lar reaction. However, we encourage contemporary experimental studies. Finally, the C2H4 + C3H3+ reaction is included in the UMIST database (Millar et al. 2024) with a total rate constant of 1.1 × 10−9 cm3 s−1 leading exclusively to C5H5+ + H2. This rate constant can be updated with our results, also including the formation of CH3CCH2+ + C2H2 with the Arrhenius-Kooij parameters shown in Table 1.

|

Fig. 4 Depiction of the reaction network of the C2H4 + CH2CCH+ reaction. The energies are calculated at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pvtz level with the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD harmonic ZPE. In the diagram, EQ ‘equilibrium structure’ refers to the wells (local minima) on the PES; TS stands for ‘transition states’ and DC ‘dissociation channels’. This nomenclature is chosen to be consistent with that provided by the GRRM code (Maeda et al. 2023b). |

3.4 c-C5H5+ as a product of the reaction and the key to new reactivity

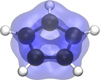

The formation of the cyclopentadienylium cation (c-C5H5+) as the main product of the C2H4 + CH2CCH+ reaction may provide a new starting point for the molecular growth in TMC-1. The molecule is a triplet in its electronic ground state, and although the PES shown in Fig. 4 is a singlet, we assumed that it radiatively relaxes after formation. Its anti-aromatic nature makes it a very unstable and reactive molecule, and it is a promising candidate to continue exploring the bottom-up formation of larger aromatic compounds. Figure 6 shows its corresponding spin density in the ground state, which is evenly distributed across all carbon atoms, suggesting that these sites are equally reactive.

For example, its neutral analogue, the cyclopentadienyl radical (c-C5H5), has already been considered as potential candidate for the bottom-up formation of PAHs in the recent works Kaiser et al. (2021), García de la Concepción et al. (2023). To study the reactivity of c-C5H5+ and verify its contribution to the interstellar chemistry, we first identified the possible products of the dissociative recombination of c-C5H5+ with electrons by performing a SC-AFIR exploration of the local and global minima along the PES of c-C5H4, adopting a value of γ = 1000.0 kJ mol−1. Initial explorations were carried out using the semi-empirical PM7 method (Stewart 2013), which provides an optimal balance between computational efficiency and accuracy for large molecular systems. The most stable structures identified in this initial phase were subsequently refined at the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD level of theory to ensure the reliability of the results, with the energies being calculated at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ level with the ZPE correction. The prediction of the electron recombination products is highly uncertain, and this is why we assume that the reaction mainly proceeds through hydrogen elimination:

(12)

(12)

The different isomeric forms of C5H4 motivate the systematic exploration of the energy profile of the C5H4 molecular formula. The SC-AFIR simulation revealed a total of 454 isomers for this system, where only the most stable ones have been detected with high abundances in the ISM, including methyl diacetylene (CH3C4H), allenyl acetylene (H2CCCHCCH; Cernicharo et al. 2021d) and the 1,4-pentadiyne (HCCCH2CCH; Fig. 7; Fuentetaja et al. 2024).

The most stable products recognized during our exploration agree with the five linear isomers of C5H4 reported in Fuentetaja et al. (2024). Only one cyclic isomer is found, with a relative energy significantly higher than the linear ones, which means that the reaction of c-C5H5+ with electrons is unlikely to preserve the cyclic structure and the fragmentation into the more stable linear fragments is favoured as exemplified in Fig. 7. Interestingly, the products of the dissociative recombination of c-C5H5+ open a new pathway for the formation of linear carbon chains that have recently been detected in TMC-1. Within the stability ladder below 10 kcal mol−1 shown in Fig. 7, only H2CCCCCH2 has not been directly observed in TMC-1, as it lacks a permanent dipole moment. Together with the high abundance of the precursor of the title reaction and its favourable kinetics, this supports a plausible top-down formation route for these species.

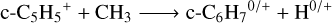

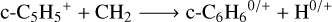

The reaction of c-C5H5+ with abundant radicals in TMC-1 can potentially induce ring expansion, leading to the formation of larger aromatic compounds. Reactions with atomic carbon (C) and methylidyne (CH) can compete with electron recombination, and we additionally tested the reactions with CH2 and CH3, to which one could add C2H, C3H, and any other carbon-bearing abundant radical. We conducted a preliminary investigation using our automated path search protocol, while a more detailed analysis of the reaction mechanisms is postponed to future work. This search revealed remarkably rich reactivity, characterized by the identification of several energetically accessible reaction pathways3:

(13)

(13)

(14)

(14)

(15)

(15)

(16)

(16)

It should be noted that if reaction (16) is proven to be effective, it would play a major role in the formation of benzyne (c-C6H4), whose ortho isomer was detected in TMC-1 by the QUIJOTE survey (Cernicharo et al. 2021b). Although several neutral-neutral routes were first proposed to account for the observed abundance of o-C6H4 (Zhang et al. 2011), its formation mechanism is still under investigation. Therefore, this reaction may very well represent an alternative pathway to benzyne formation, supporting the bottom-up formation of aromatic molecules in space.

The best observationally constrained proxy to assess the impact of reactions (13)-(16) is benzonitrile (C6H5CN), detected by McGuire et al. (2018). Therefore, we incorporated the reactions (13)-(16) into the astrochemical model of TMC-1, assuming a rate coefficient of 10−9 cm3 s−1 for each, following the same approach as in the exploration of c-C5H7+ (details in Sect. 3.1). Additionally, we considered rate constants of 10−10 cm3 s−1 in our investigation, to evaluate the sensitivity of the model to these reactions. The results, displayed in Fig. 8, show that the original model already reproduced reasonably the observed abundance of C6H5CN. The inclusion of reactions (13)-(16) significantly enhances the abundance of C6H5CN below the characteristic timescale of TMC-1 (Wakelam et al. 2006) of around 1×105 years. This time displacement in chemical models is independent of the value of the rate constants and it is in line with some of our latest results, in which the abundance of certain molecules is better reproduced at earlier times (Cernicharo et al. 2022).

|

Fig. 5 Rate constants (k) for the formation of the exothermic products of the C2H4 + CH2CCH+ reaction as a function of temperature in the range 80-300 K and a pressure of 10−7 atm. |

|

Fig. 6 Representation of the spin density distribution of the cyclopentadienylium cation (c-C5H5+) in its triplet ground state, calculated at the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD level of theory. The isovalue is set to 0.005 a.u. |

|

Fig. 7 Representation of the relative energy of the five most stable isomers of C5H4 with respect to the cyclic structure. The energies are calculated at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pvtz level with the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD harmonic ZPE. The isomers that have been detected in TMC-1 are covered with black boxes (Cernicharo et al. 2021d; Fuentetaja et al. 2024). |

3.5 The c-C5H5+ + H2 reaction

Our exploration can be extended to other ion-molecule reactions that were initially considered in Sect. 3.1. The reaction between c-C5H5+ and H2 (Eq. (4)) is predicted to have the strongest impact on the abundance of cyclopentadiene in TMC-1 according to Fig. 2. During the automated search of reaction pathways for the CH2CCH+ + C2H4 system, we identified the c-C5H5+ + H2 channel exhibiting an entrance barrier of 3 kcal mol−1. However, Fig. 4 corresponds to the singlet PES, while the ground state of c-C5H5+ is a triplet (Lee & Wright 1999). Since electronic states play a crucial role in the definition of the reaction pathways, we performed an exploration of the c-C5H5+ + H2 reaction in the triplet state to confirm its viability and identify the presence or absence of entrance barriers for this scenario.

Following the methodology employed throughout this project, we performed MC-AFIR calculations to explore the possible association complexes for the c-C5H5+ + H2 reaction in the triplet state. No evidence of barrier-less adduct formation was found, suggesting that the reaction is unlikely to occur under cold interstellar conditions. To validate this result, we constructed the reaction path for c-C5H5+ + H2, shown in Fig. 9. An entrance barrier of 30.9 kcal mol−1 was identified, which cannot be overcome in typical interstellar environments. The reaction proceeds through the formation of a post-reactant complex and an additional barrier. In the triplet state, the formation of c-C5H7+ is endothermic, thereby definitively ruling out c-C5H5+ + H2 as a viable pathway to c-C5H7+ in TMC-1.

|

Fig. 8 Prediction of the relative abundance of benzonitrile (C6H5CN) as a function of time in the chemical model of TMC-1. The solid black line is the abundance predicted by the model before including the ring expansion mechanisms, and the dashed lines represents how it is modified when considering the formation of the six-membered rings for two possible reaction rate constants, 10−9 (green) and 10−10 (red); see the main text. The horizontal dotted line represents the observed abundance of benzonitrile in TMC-1 (Cernicharo et al. 2021c). |

|

Fig. 9 Energy profile of the c-C5H5+ + H2 reaction in the triplet state. The energies are calculated at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pvtz level with the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD harmonic ZPE. |

4 Conclusions

Our results imply a series of far-reaching repercussions for the astrochemical community, in particular regarding the reactivity of aromatic hydrocarbons in the ISM.

As shown in Fig. 2, the initial model of TMC-1 predicts abundances for c-C5H6 that are several orders of magnitude lower than the observed values. Our results indicate that all the ion-neutral routes initially proposed for the synthesis of c-C5H7+ are not efficient enough to account for the observed abundance of cyclopentadiene in TMC-1, including the radiative association of C2H4 + CH2CCH+. This has several implications for the bottom-up formation scenario. First, it clearly points to the existence of as yet unidentified molecular formation pathways. Second, it may indicate that the efficiencies of the destruction channels are being overestimated. Finally, it suggests that a fraction of cyclopentadiene is inherited from preceding top-down chemistry. A combination of these factors may well provide the explanation, although we are more inclined to attribute the discrepancy to an incomplete reaction network for this species, whose chemistry remains poorly characterized. As is frequently the case in astrochemistry, we cannot rule out the possibility that the apparent underestimation of cyclopentadiene arises from a similar underestimation of its precursors, particularly the neutral species, as suggested, for example, by García de la Concepción et al. (2023).

From Fig. 4, the main reaction pathways can be inferred. The formation of CH3CCH2+ and C2H2 from the potential well R3, without going through any intermediate structures, indicates that the reverse reaction, i.e. CH3CCH2+ + C2H2, would access the PES exothermically via the barrier-less adduct R3, from which the dominant channel leads to c-C5H5+ + H2. Regarding the c-C5H5+ + H2 channel in the singlet state to form R2, an activation barrier of 3 kcal mol−1 is found, demonstrating that the reaction between c-C5H5+ and H2 is not barrier-less and would not take place under interstellar conditions. Moreover, it is safe to assume that singlet c-C5 H5 + under interstellar conditions will decay to the triplet state before partaking in any other collision.

We next examined the main product of the title reaction, c-C5H5+, finding it to have an unexpected role in the formation of detected carbon chains and cyclic molecules alike. In Sect. 3.4 we suggest that it may be a leading factor in the complex hydrocarbon chemistry in TMC-1. Eyler (1984) demonstrated experimentally that the C5H5+ cation is reactive towards neutral species such as ethyne (C2H2), ethylene (C2H4), methylacetylene (CH3CCH), and diacetylene (C4H2) at room temperature (300K). None of these reactions are included in the UMIST database and therefore are not considered in the models to evaluate their impact in colder environments. However, using our automated protocol to study them can further enhance our knowledge of the unconventional chemistry protagonized by this radical cation. The reactions of c-C5H5+ with neutral, abundant species will be further explored in the near future. So far, in the present work, we have proven the formation of the c-C5H5+ cation with fast rate coefficients at low temperatures, and therefore we propose it is a key molecule in the chemistry of the ISM, opening the door to a new reactivity that was not considered before. Our astrochemical models indicate that the reactions of c-C5 H5 + with small atoms and radicals may play a dominant role in the formation of the best known PAH precursor, benzonitrile, and therefore benzene and other PAHs in cold dense clouds.

To sum up, we emphasize the importance of the methodological advances achieved in this work. By developing a protocol that combines approximate astrochemical models to identify key reactions with state-of-the-art automated reaction route mapping (GRRM23), quantum-chemical calculations, and kinetic modelling, we were able to self-consistently improve the chemical description of TMC-1 through the formation of c-C5H5+. This ion has been identified as both a potential precursor to larger aromatic compounds and a possible contributor to the observed isomers of C5H4 in TMC-1. A major limitation, not addressed in detail here, is the computational cost associated with the automatic reaction discovery protocol, which currently prevents the simultaneous exploration of tens or hundreds of reactions. For this reason, astrochemical models are invaluable for rapidly filtering promising reactions, but they remain insufficient on their own. The development of broadly applicable machine-learned potentials for astrochemically relevant systems could greatly accelerate the exploration of PESs and, therefore, the entire protocol. Achieving this objective remains a long-term goal for our group.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank the reviewer of this manuscript, Emilio Martinez Nuñez, for his thorough revision of our work. G.M. acknowledges the support of the grant RYC2022-035442-I funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and ESF+. G.M. also received support from project 20245AT016 (Proyectos Intramurales CSIC). We acknowledge the computational resources provided by the DRAGO computer cluster managed by SGAI-CSIC, and the Galician Supercomputing Center (CESGA). The supercomputer FinisTerrae III and its permanent data storage system have been funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, the Galician Government and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). M.A., C.C. and J.C. acknowledge funding support from the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades through project PID2023-147545NB-I00, M.M., G.M. and O.R. through the project PID2024-156686NB-I00 and O.R. through the project PID2021-122549NB-C21.

References

- Agúndez, M., & Wakelam, V. 2013, Chem. Rev., 113, 8710 [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez, M., Fonfría, J. P., Cernicharo, J., Pardo, J. R., & Guélin, M. 2008, A&A, 479, 493 [Google Scholar]

- Agúndez, M., Cabezas, C., Marcelino, N., et al. 2025, A&A, 697, A82 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Allamandola, L., Tielens, A., & Barker, J. 1985, ApJ, 290, L25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anicich, V. G. 2003, Tech. Rep. JPL 03-19, Jet Propulsion Laboratory [Google Scholar]

- Balucani, N., Asvany, O., Chang, A., et al. 1999, J. Chem. Phys, 111, 7457 [Google Scholar]

- Balucani, N., Skouteris, D., Ceccarelli, C., et al. 2018, Mol. Astrophys, 13, 30 [Google Scholar]

- Betz, A. L. 1981, ApJ, 244, L103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bjornsson, R. 2022, ASH - a multiscale modelling program, https://ash.readthedocs.io/en/latest/, accessed: 2025-06-21 [Google Scholar]

- Cabezas, C., Agúndez, M., Pérez, C., et al. 2025, A&A, 701, L8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Castiñeira Reis, M., Martínez Núñez, E., & Fernández Ramos, A. 2024, Sci. Adv., 10, eadq4077 [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., & Guélin, M. 1987, A&A, 176, 299 [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Agúndez, M., Cabezas, C., et al. 2021a, A&A, 649, L15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Agúndez, M., Kaiser, R. I., et al. 2021b, A&A, 652, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Agúndez, M., Kaiser, R. I., et al. 2021c, A&A, 655, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Cabezas, C., Agúndez, M., et al. 2021d, A&A, 647, L3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Fuentetaja, R., Agúndez, M., et al. 2022, A&A, 663, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Cabezas, C., Pardo, J., et al. 2023, A&A, 672, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicharo, J., Cabezas, C., Fuentetaja, R., et al. 2024, A&A, 690, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chai, J.-D., & Head-Gordon, M. 2008, J. Chem. Phys., 128 [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, I. R., Gupta, D., Messinger, J. P., & Sims, I. R. 2020, ApJ, 891, L41 [Google Scholar]

- Doddipatla, S., Galimova, G. R., Wei, H., et al. 2021, Sci. Adv., 7, eabd4044 [Google Scholar]

- Eyler, J. R. 1984 [Google Scholar]

- Fonfría, J. P., Hinkle, K., Cernicharo, J., et al. 2017, ApJ, 835, 196 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., et al. 2016, Gaussian 16 Revision C.01, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford CT [Google Scholar]

- Fuentetaja, R., Agúndez, M., Cabezas, C., et al. 2024, A&A, 688, L15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- García de la Concepción, J. G., Jiménez-Serra, I., Rivilla, V. M., et al. 2023, A&A, 673, A118 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Georgievskii, Y., Miller, J. A., Burke, M. P., & Klippenstein, S. J. 2013, J. Phys. Chem. A, 117 [Google Scholar]

- Goettl, S. J., Ahmed, M., Mebel, A. M., & Kaiser, R. I. 2025a, Acc. Chem. Res., 5369 [Google Scholar]

- Goettl, S. J., Turner, A. M., Kaiser, R. I., et al. 2025b, Sci. Adv., 11 [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., Riplinger, C., Becker, U., et al. 2018, J. Chem. Phys., 148, 011101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, P. C., & Pople, J. A. 1973, Theor. Chim. Acta., 28, 213 [Google Scholar]

- Hehre, W. J., Ditchfield, R., & Pople, J. A. 1972, J. Chem. Phys., 56, 2257 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heitkämper, J., Suchaneck, S., García de la Concepción, J., Kästner, J., & Molpeceres, G. 2022, Front. Astron. Space Sci., 9, 1020635 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, E. 1982, Chem. Phys., 65, 185 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, E. 2021, Front. Astron. Space Sci, 8, 776942 [Google Scholar]

- Joblin, C., & Cernicharo, J. 2018, Science, 359 [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B. M., Zhang, F., Kaiser, R. I., et al. 2011, PNAS, 108, 452 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, R., Vereecken, L., Peeters, J., Bettinger, H., & Schaefer, H. 2003, A&A, 406, 385 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, R. I., Zhao, L., Lu, W., et al. 2021, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 13 [Google Scholar]

- Kocheril, G., Zagorec-Marks, C., & Lewandowski, H. 2025, Nat. Astron., 1 [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, Y., & Suzuki, T. 2022, ACS Earth Space Chem., 6, 2491 [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, Y., & Furuya, K. 2023, ACS Earth Space Chem., 7, 1753 [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. P., & Wright, T. G. 1999, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 1, 219 [Google Scholar]

- Loison, J.-C., Rossi, C., Solem, N., et al. 2025, arXiv preprint [arXiv:2506.13290] [Google Scholar]

- Léger, A., & Puget, J. 1984, A&A, 137, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, S., & Harabuchi, Y. 2021, WIREs Computat. Mol. Sci., 11 [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, S., Ohno, K., & Morokuma, K. 2013, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 15, 3683 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, S., Harabuchi, Y., Takagi, M., Taketsugu, T., & Morokuma, K. 2016, Chem. Rec., 16, 2232 [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, S., Harabuchi, Y., Takagi, M., et al. 2018, J. Comput. Chem, 39, 233 [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, S., Harabuchi, Y., Hayashi, H., & Mita, T. 2023a, Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem., 74, 287 [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, S., Harabuchi, Y., Sumiya, Y., et al. 2023b, GRRM23, see https://global.hpc.co.jp/products/grrm23/. Accessed: December 15, 2025 [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Núñez, E., Barnes, G. L., Glowacki, D. R., et al. 2021, J. Comput. Chem, 42, 2036 [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, H. E., & Sears, T. J. 1983, ApJ, 272, 149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, M. J., Scott, G. B., Adams, N. G., et al. 1999, ApJ, 513 [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, B. A., Burkhardt, A. M., Kalenskii, S., et al. 2018, Science, 359, 202 [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, B. A., Loomis, R. A., Burkhardt, A. M., et al. 2021a, Science, 371, 1265 [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, B. A., Loomis, R. A., Burkhardt, A. M., et al. 2021b, Science, 371 [Google Scholar]

- Millar, T., Walsh, C., Van de Sande, M., & Markwick, A. 2024, A&A, 682, A109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J. A., & Klippenstein, S. J. 2006, J. Phys. Chem. A, 110 [Google Scholar]

- Møller, C., & Plesset, M. S. 1934, Phys. Rev., 46, 618 [Google Scholar]

- Neese, F. 2025, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Mol. Sci., 15, e70019 [Google Scholar]

- Neese, F., Wennmohs, F., Becker, U., & Riplinger, C. 2020, J. Chem. Phys., 152, 224108 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Papajak, E., Zheng, J., Xu, X., Leverentz, H. R., & Truhlar, D. G. 2011, J. Chem. Theory Comput., 7, 3027 [Google Scholar]

- Pechukas, P., & Light, J. C. 1965, J. Chem. Phys., 42, 3281 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard, B. P., Altarawy, D., Didier, B., Gibson, T. D., & Windus, T. L. 2019, J. Chem. Inf. Model., 59, 4814 [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, G. D., & Bartlett, R. J. 1982, J. Chem. Phys., 76, 1910 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rappoport, D., & Furche, F. 2010, J. Chem. Phys., 133, 134105 [Google Scholar]

- Riplinger, C., & Neese, F. 2013, J. Chem. Phys., 138 [Google Scholar]

- Sameera, W. M. C., Maeda, S., & Morokuma, K. 2016, Acc. Chem. Res., 49, 763 [Google Scholar]

- Silva, W., Cernicharo, J., Schlemmer, S., et al. 2023, A&A, 676, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, K. C., Lias, S., & Ausloos, P. 1982, Combust. Sci. Technol., 28, 147 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, J. J. 2013, J. Mol. Model, 19, 1 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennis, J., Loison, J.-C., & Herbst, E. 2021, ApJ, 922, 133 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, A. M., Doddipatla, S., Kaiser, R. I., Galimova, G. R., & Mebel, A. M. 2019, Sci. Rep., 9, 17595 [Google Scholar]

- Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2005, The Physics and Chemistry of the Interstellar Medium, 1st edn. (Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Truhlar, D. G. 1969, J. Chem. Phys., 51, 4617 [Google Scholar]

- Türtscher, P. L., & Reiher, M. 2023, J. Chem. Inf. Model., 63, 147 [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vijver, R., & Zádor, J. 2020, Comput. Phys. Commun., 248, 106947 [Google Scholar]

- Wakelam, V., Herbst, E., & Selsis, F. 2006, A&A, 451, 551 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Weigend, F., & Ahlrichs, R. 2005, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 7 [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, G., Gong, S., Xue, C., et al. 2024, Science, 386 [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, G., Speak, T. H., Changala, P. B., et al. 2025a, Nat. Astron., 9, 262 [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, G., Gong, S., Xue, C., et al. 2025b, ApJ, 984 [Google Scholar]

- Woods, P. M., Millar, T., Zijlstra, A., & Herbst, E. 2002, ApJ, 574, L167 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Woon, D. E., & Dunning, T. H. 1994, J. Chem. Phys., 100 [Google Scholar]

- Woon, D. E., & Herbst, E. 2009, ApJS, 185, 273 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z., He, C., Goettl, S. J., et al. 2024a, Nat. Astron., 8, 856 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z., Medvedkov, I. A., Goettl, S. J., et al. 2024b, PNAS, 121 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F., Parker, Dorianand Kim, Y. S., Kaiser, R. I., & Mebel, A. M. 2011, ApJ, 728, 141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-F., Li, W., Wang, C.-Y., et al. 2025, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., 27, 4934 [Google Scholar]

The def2-TZVPD basis set is included in GAUSSIAN 16 from the corresponding entry of the Basis Set Exchange Library https://www.basissetexchange.org/ (Pritchard et al. 2019).

Only the capture event is strictly temperature-independent through the Langevin rate. In contrast, all unimolecular isomerizations within the wells depend on the available energy budget, which includes thermal contributions. At low temperatures this contribution becomes less significant, thereby supporting the validity of the rate constants derived down to 80 K.

Appendix A Derivation of the radiative association rate constant for the C5H7+ channel

In the main text we conclude that the radiative association channel for the CH2CCH+ + C2H4 reaction, leading to C5H7+ is negligible in comparison with the bimolecular channels. Determining the radiative association rate constant (krad) in a PES landscape as complex as the one shown in Fig. 4 is a daunting task. Therefore, in this appendix we derive the simplified value for such a rate constant that we used for comparison in the main text and report in Table 1. Considering that there are open bimolecular channels in the reaction, we can take the back dissociation rate constant k−1 out of Eq. 11 of the main text:

(A.1)

(A.1)

where all previously defined quantities are retained. In our approximate scheme to determine krad, a few simplifying assumptions were introduced. First, although the association complex resulting from the CH2CCH+ + C2H4 reaction corresponds to R1 (Fig. 3a), we assumed for the purpose of our derivation that the complex is captured in R2 with the same capture rate constant (k1). This is justified because R2 represents the deepest well on the sampled PES and the configuration from which radiative emission would most likely yield the product of interest, c-C5H7+. Second, we assumed that k2, which in principle accounts for all possible bimolecular transitions out of the PES, leads exclusively to the formation of c-C5H5+ + H2, without involving any pre-reactive complexes, in contrast with the full scheme shown in Fig. 4. Within this framework, we effectively decouple the radiative association probability from potential isomerizations across the entire PES, thereby reducing the ‘effective’ surface to that depicted in Fig. A.1. These approximations are valid only when krad is several orders of magnitude smaller than the competing channels, which, as will be shown below, is indeed the case. In Eq. A.1, k1 and k2 are obtained from our master equation analysis: k1 represents the capture rate constant, while k2 corresponds to the (microcanonical) forward rate constant leading to c-C5H5 + H2 (i.e. the pre-reactive complex). Therefore, in order to apply Eq. A.1, it only remains to determine kr.

|

Fig. A.2 Radiative and unimolecular forward rate constants for the competing processes of the formation of c-C5H7+ or c-C5H5+ + H2;, the energy of the activated complex (Evib) is taken as the origin zero energy. Energies below 0 kcal mol−1 are not physically feasible for this system. |

Following Herbst (1982) and more recently Tennis et al. (2021), the rate constant for the radiative emission rate, assuming that the activated complex can be stabilized by the emission of a single photon, assuming harmonic approximation and statistical distribution of the association energy between the reactants is

(A.2)

(A.2)

In the above equation, Evib is the vibrational energy of the activated complex (R2 in this case), which is the well energy (93.5 kcal mol−1 with the addition of any additional collision energy), s is the number of molecular vibrations partaking in the ergodic energy distribution,  are the Einstein spontaneous emission coefficients for each vibration (i), h is the Planck constant and νi the fundamental frequency of mode i. The

are the Einstein spontaneous emission coefficients for each vibration (i), h is the Planck constant and νi the fundamental frequency of mode i. The  can be determined as

can be determined as

(A.3)

(A.3)

where, in addition to the speed of light constant (c), the only remaining quantity to define is Ii that is the infrared intensity of each normal mode. The results for kr can be visualized in Fig. A.2. From the graph, it is evident that at Evib, k1 clearly dominates, which represents the optimistic case for radiative association where the relative energy for the collision is zero, and the available energy to the system is only the association energy at R2. Plugging the obtained numbers into Eq. A.1, we obtain a radiative association rate constant of krad≤3.25×10−14 cm3 s−1, which remains rather constant at low temperatures, but that should decay even further when k1 rises at higher temperature. The krad is around 4-5 orders of magnitude lower than the competing process. This is the value of the rate constant reported in Table 1 and used to establish comparisons in the main text. To conclude, we also tested the validity of the method shown in (Tennis et al. 2021) with a more accurate representation of the radiative transfer process, proposed in Cernicharo et al. (2023). The value of kr according to Cernicharo et al. (2023) is determined to be 3.86 ×102 s−1, compared to 1.53 ×102 s−1 obtained from Eq. A.2. No significant differences were observed between the models in terms of the radiative emission rate constant (i.e. the parameter that would change in Eq. A.1), which indicates that our results from the simplified model are reliable.

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of our automated protocol to explore the reaction network of ion-molecule systems. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Prediction of the relative abundance of cyclopentadiene (c-C5H6) as a function of time in the chemical model of TMC-1. The solid black line is the abundance predicted by the model without ion-molecule reactions, dashed lines represent how it is modified by including each of the reactions separately, and the solid green line is the total abundance when all the reactions from the dashed lines are included. The horizontal dotted line represents the observed abundance of cyclopentadiene in TMC-1, calculated from its column density (Cernicharo et al. 2021a). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 From left to right: structures of R1, R2, and R3 (all of them isomeric forms of C5H7+). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Depiction of the reaction network of the C2H4 + CH2CCH+ reaction. The energies are calculated at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pvtz level with the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD harmonic ZPE. In the diagram, EQ ‘equilibrium structure’ refers to the wells (local minima) on the PES; TS stands for ‘transition states’ and DC ‘dissociation channels’. This nomenclature is chosen to be consistent with that provided by the GRRM code (Maeda et al. 2023b). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Rate constants (k) for the formation of the exothermic products of the C2H4 + CH2CCH+ reaction as a function of temperature in the range 80-300 K and a pressure of 10−7 atm. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Representation of the spin density distribution of the cyclopentadienylium cation (c-C5H5+) in its triplet ground state, calculated at the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD level of theory. The isovalue is set to 0.005 a.u. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Representation of the relative energy of the five most stable isomers of C5H4 with respect to the cyclic structure. The energies are calculated at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pvtz level with the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD harmonic ZPE. The isomers that have been detected in TMC-1 are covered with black boxes (Cernicharo et al. 2021d; Fuentetaja et al. 2024). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Prediction of the relative abundance of benzonitrile (C6H5CN) as a function of time in the chemical model of TMC-1. The solid black line is the abundance predicted by the model before including the ring expansion mechanisms, and the dashed lines represents how it is modified when considering the formation of the six-membered rings for two possible reaction rate constants, 10−9 (green) and 10−10 (red); see the main text. The horizontal dotted line represents the observed abundance of benzonitrile in TMC-1 (Cernicharo et al. 2021c). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Energy profile of the c-C5H5+ + H2 reaction in the triplet state. The energies are calculated at the DLPNO-CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pvtz level with the ωB97XD/def2-TZVPD harmonic ZPE. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.1 Reduced PES (originally from Fig. 4) used in the radiative association model. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.2 Radiative and unimolecular forward rate constants for the competing processes of the formation of c-C5H7+ or c-C5H5+ + H2;, the energy of the activated complex (Evib) is taken as the origin zero energy. Energies below 0 kcal mol−1 are not physically feasible for this system. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.