| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L13 | |

| Number of page(s) | 4 | |

| Section | Letters to the Editor | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202558710 | |

| Published online | 10 February 2026 | |

Letter to the Editor

How supermassive black holes shape central entropies in galaxy clusters

Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) An der Sternwarte 16 14482 Potsdam, Germany

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

20

December

2025

Accepted:

26

January

2026

A significant fraction of galaxy clusters show central cooling times of less than 1 Gyr and associated central cluster entropies below 30 keV cm2. We provide a straightforward explanation for these low central entropies in cool core systems and how this is related to accretion onto supermassive black holes (SMBHs). Assuming a time-averaged equilibrium between active galactic nucleus (AGN) jet heating of the radiatively cooling intracluster medium and Bondi accretion, we derived an equilibrium entropy that scales with the SMBH and cluster mass as K ∝ M∙4/3M500c−1. At fixed cluster mass, overly massive SMBHs would raise the central entropy above the cool core threshold, thus implying a novel way of limiting SMBH masses in cool-core clusters. We find a limiting mass of 1.4 × 1010 M⊙ in a cool-core cluster of mass 1015 M⊙. We carried out three-dimensional hydrodynamical simulations of an idealised Perseus-like cluster with AGN jets and find that they reproduce the predictions of our analytic model, once corrections for elevated jet entropies are applied when calculating X-ray emissivity-weighted cluster entropies. Our findings have significant implications for modelling galaxy clusters in cosmological simulations: a combination of overmassive SMBHs and high heating efficiencies precludes the formation of cool-core clusters.

Key words: methods: analytical / methods: numerical / galaxies: clusters: intracluster medium / galaxies: jets

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Galaxy clusters exhibit increasing entropy profiles with radius in the outskirts that are predominantly caused by cosmological gas accretion onto clusters (Voit et al. 2005). At smaller radii, the entropy profiles are diverse and show a bimodal distribution in core entropy values (Cavagnolo et al. 2009; Hudson et al. 2010), which are separated by a critical cluster electron entropy of

where kB denotes Boltzmann’s constant, and Te and ne denote the electron temperature and density, respectively. Clusters with central entropy values exceeding Ke, crit are non-cool core systems with comparatively hot cores that are characterised by long central gas cooling times (τcool > 1 Gyr). By contrast, clusters with central entropy values below Ke, crit show a temperature dip towards the centre (Vikhlinin et al. 2006) and have short central gas cooling times (τcool < 1 Gyr).

In the absence of heating, the cores of cool-core clusters would be expected to cool rapidly and sustain star formation at rates of up to several hundred M⊙ yr−1 (see Peterson & Fabian 2006, for a review). Observationally, however, both gas cooling and star formation occur at levels far below those predicted by classical, unimpeded cooling-flow models. High-resolution observations with Chandra and XMM-Newton reveal a smooth decline in gas temperature towards cluster centres, yet show little evidence of emission from gas cooler than ∼1 keV (see the multi-temperature models of Hudson et al. 2010). This suggests that radiative cooling is balanced by a heating mechanism, most likely linked to feedback from the active galactic nucleus (AGN), as indicated by jet-inflated radio lobes spatially coincident with X-ray cavities and a positive correlation between lobe enthalpy and central intracluster medium (ICM) entropy (Fig. 6 of Pfrommer et al. 2012), which demonstrates that a single AGN outburst is unable to transform a cool core to a non-cool-core cluster on the buoyant rise time. Note that part of the observed deficit of soft X-ray emission may be attributable to X-ray absorption (Fabian et al. 2022). Nevertheless, the coupled evolution of gas cooling, star formation, and nuclear activity therefore appears to operate within a self-regulated feedback loop (Voit & Donahue 2005; McNamara & Nulsen 2007, 2012; Fabian 2012). Understanding what sets the central entropy structure in galaxy clusters is a key part of understanding the cooling-flow problem (Peterson et al. 2003).

Simulations of galaxy clusters have long struggled to reliably predict the central entropy profiles. Initial attempts suffered from different numerical methodologies producing unphysical central entropy profiles in non-radiative simulations (steep power-law profiles in smoothed-particle hydrodynamics and overly extended cores with adaptive mesh-refinement; Frenk et al. 1999; Voit et al. 2005), overshadowing the possible physical mechanisms causing entropy cores. The inclusion of radiative cooling, AGN heating, and cosmic rays (e.g. Sijacki & Springel 2006; Cattaneo & Teyssier 2007; Sijacki et al. 2008; Ehlert et al. 2018) added to the complexity. The modelling of AGN feedback in particular added a significant degree of freedom to numerical models, creating difficulties in precisely attributing reported differences. To this day, numerical models struggle to reliably reproduce the central entropy cores of groups and clusters (e.g. Barnes et al. 2017, 2018; Altamura et al. 2023; Pakmor et al. 2023; Hernández-Martínez et al. 2025), with some simulations reporting cool-core clusters emerging in clusters below 1015 M⊙ but not above (Fig. 8 of Lehle et al. 2024). Importantly, no model fully reproduces the observed central entropy statistics.

In light of these mixed simulation results, we revisited the problem of central entropy profiles in galaxy clusters from an analytic perspective (see e.g. Nulsen 2004; Binney 2005; Voit & Donahue 2005, 2015), with a particular focus on the behaviour of hydrodynamical simulations. To this end, we used an isolated galaxy cluster with a self-regulated AGN jet heating model (Ehlert et al. 2023; Weinberger et al. 2023, advancing earlier work by Weinberger et al. 2017a) to test our analytic considerations. The Letter is structured as follows: In Sect. 2 we derive the central entropy of a cool-core galaxy clusters from a set of simple assumptions. We test this model using hydrodynamical simulations in Sect. 3 and conclude in Sect. 4.

2. Analytic model

Consider a cool-core cluster with a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at its centre. We assumed the accretion rate (Ṁ) follows the Bondi–Hoyle–Lyttleton formula (Hoyle & Lyttleton 1939; Bondi & Hoyle 1944; Bondi 1952; Edgar 2004):

Here G denotes the gravitational constant, M• is the SMBH mass, P and ρ denote the surrounding pressure and density, and  and K = P ρ−γ are the sound speed and pseudo-entropy, respectively, where γ = 5/3 is the adiabatic index of the gas. In the last step, we assumed that the SMBH has a negligible velocity in the cluster potential minimum in comparison to the sound speed: v ≪ cs. Observationally, the cluster electron entropy,

and K = P ρ−γ are the sound speed and pseudo-entropy, respectively, where γ = 5/3 is the adiabatic index of the gas. In the last step, we assumed that the SMBH has a negligible velocity in the cluster potential minimum in comparison to the sound speed: v ≪ cs. Observationally, the cluster electron entropy,

is a directly accessible quantity. Here, we assume that the electron temperature (Te) equals the ion temperature (T), an electron abundance of Xe = ne/nH = 1.16, and a mean atomic weight of μ = 0.6 for a fully ionised primordial gas with hydrogen mass fraction XH = 0.76. The proton mass is denoted by mp. The accretion rate can therefore be written as

A fraction (ϵ) of the accreted rest mass energy is accelerated as a collimated jet out to kiloparsec scales and heats the surrounding ICM in the cluster core (see e.g. Voit & Donahue 2005, for a discussion on the entropy increase due to an AGN jet outburst), yielding a heating rate of

where c is the vacuum speed of light. We can compute the equilibrium central entropy by assuming that the energy injection from the jets matches the cooling luminosity if averaged over timescales longer than the jet duty cycle, Lcool = Ė (Bîrzan et al. 2004; Dunn & Fabian 2006; Hlavacek-Larrondo et al. 2015):

Identifying the ICM cooling luminosity with the bolometric X-ray luminosity, Lcool = Lbol, we can express Lbol in terms of a characteristic cluster mass by means of observed galaxy cluster scaling relations (using the relation by Chiu et al. 2022, which is consistent with that of Mantz et al. 2010),

and so can write the cluster electron entropy in terms of SMBH mass and cluster mass:

This implies a limiting SMBH mass of 1.4 × 1010 M⊙ in a cool-core cluster of mass 1015 M⊙ (assuming ϵ = 0.2, adopted from the kinetic feedback efficiency in Weinberger et al. 2017b). Conversely, for a fixed SMBH mass, the core entropy increases towards smaller galaxy clusters. However, the central galaxies in these systems are found to host significantly less massive SMBHs, which may overcompensate for the decrease in halo mass (Booth & Schaye 2010). This highlights the need for a deeper understanding of the relationship between SMBH and halo masses in this regime.

3. Comparison to simulations

To test if our model holds in a more realistic setting, we ran three-dimensional hydrodynamical simulations as presented in Weinberger et al. (2023), using the isolated Perseus cluster analogue initial conditions presented in Ehlert et al. (2023). We restricted ourselves to simulations with slightly lower resolutions in the ICM than the fiducial model in Ehlert et al. (2023), i.e. a target gas mass resolution of 107 M⊙ because this is sufficient to show the steady-state behaviour and we aim to match achievable resolutions in cosmological zoom simulations of galaxy clusters. The spatial resolution in the jet was kept identical to the fiducial resolution of Ehlert et al. (2023) at 0.65 kpc. While there are some differences in the cold gas properties between magneto-hydrodynamic and purely gas-dynamical models, both simulations self-regulate to a similar ICM (Ehlert et al. 2023).

To study the scalings predicted in the central entropy model, we ran simulations with different SMBH masses, from M• = 109 M⊙ h−1 to M• = 3 × 1011 M⊙ h−1, using h = 0.67. Since efficiency (ϵ) and SMBH mass squared (M•2) are degenerate (the SMBH growth through accretion is negligible in this setup), we fixed the efficiency at ϵ = 0.2. We let the simulation equilibrate for 0.55 Gyr and analysed five snapshots between 0.55 Gyr and 1 Gyr to study the dynamical equilibrium and its scatter.

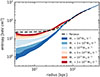

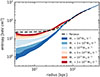

Figure 1 shows the entropy profile of X-ray-emitting gas (0.2 keV < kBT < 10 keV) calculated using the emission-weighted electron number density and the emission-weighted temperature profiles. The coloured regions show the 16th to 84th percentiles of the entropy values at different times. The electron entropy at small radii clearly depends on the SMBH mass, with lower-mass SMBHs leading to lower central entropies and more massive SMBHs equilibrating at higher entropy values. Quantitatively, however, the SMBH mass is varied by a factor of 300, which, according to Eq. (9), would imply an equilibrium entropy change of roughly 2000. In contrast, the X-ray emissivity-weighted entropy differs by only about 30. This discrepancy arises from the difference between the X-ray emissivity-weighted entropy and the entropy inferred from the accretion rate: the accretion routine is measuring the surrounding gas properties in a kernel-weighted average of all gas cells in a spherical shell enclosing 64 weighted neighbours (see Weinberger et al. 2023, for details). This notably includes recently launched jets that fill parts of this region, reducing the measured density and increasing the sound speed1. We can correct for this effect by measuring the average jet volume filling fraction, α (defined as the volume occupied by cells with a jet scalar exceeding 10−3 normalised by the total volume within a radius), while assuming the remainder is filled with gas of cluster electron entropy Ke, ICM,

|

Fig. 1. Entropy profiles of X-ray-emitting gas of Perseus analogue self-regulated simulations with different SMBH masses (see legend). The coloured area indicates the 16th to 84th percentile of snapshots at times between t = 0.55 Gyr and t = 1 Gyr. The dotted line denotes 30 keV cm2, an empirical dividing line between cool-core and non-cool-core clusters. The dashed line denotes the entropy profile of the Perseus cluster from Churazov et al. (2003), rescaled to h = 0.67. The central entropy establishes an equilibrium value that is dependent on SMBH mass. |

Here we assumed that the jet material is in pressure equilibrium with the ICM and that its mass is negligible. In the simulation, we measure α = {0.67,0.63,0.85} for M• = {109,1010,1011} M⊙ h−1. Using Eqs. (9) and (12), and the cooling luminosity in the central 100 kpc, we obtain an equilibrium ICM entropy of Ke, ICM = {0.2,6,41} keV cm2, respectively.

Figure 2 shows a temperature–density phase diagram, colour-coded by the mass in each bin for three of the simulations, for conciseness. The solid grey line indicates an entropy of 30 keV cm2, and the dashed orange line indicates the respective equilibrium ICM entropy (which is constant along this line and decreases towards the lower right). The phase distribution of the gas shows two important features: (1) The yellow-green narrow band shows the ICM, with the low-density part at large radii and higher densities corresponding to smaller radii (as the temperature change in this phase is small). (2) The diagonal blue feature ranging from low densities and very high temperatures to higher densities and lower temperatures is a signature of jets mixing isobarically with the surroundings. The most relevant aspect for self-regulation is the central entropy value, i.e. where the temperature–density relation is truncated to the right in this diagram as a result of feedback. As is evident in Fig. 2, the simulations differ markedly in this respect: the setup with the lower-mass SMBH exhibits substantially higher central ICM densities, lower central temperatures, and consequently reduced central entropies. Some of the low-entropy material undergoes thermal instability, reaching even higher densities and lower temperatures, and eventually forms stars. The derived equilibrium ICM entropies are an excellent lower limit to the entropies reached by most of the gas.

|

Fig. 2. Temperature vs density phase diagram, colour-coded by mass. The grey line indicates an electron entropy of 30 keV cm2, and the dashed orange line indicates the equilibrium ICM entropy predicted by our model (see text for details). Most of the gas mass is above our equilibrium entropy value, implying that efficient AGN jet feedback sets a SMBH mass-dependent entropy floor in the central ICM. |

4. Discussion and conclusions

We have derived the central cluster entropy in a cool-core galaxy cluster assuming an AGN jet heating–cooling balance in a time-averaged sense, Bondi-like accretion from kiloparsec scales, and a fixed jet feedback efficiency. In particular, we show here that self-regulated systems, which accrete close to the Bondi rate, have a steep scaling with SMBH mass to the point where overly massive SMBHs preclude the formation of cool-core clusters because of their efficient feedback. This provides a novel way of providing an upper limit to SMBH masses of 1.4 × 1010 M⊙ in a cool-core cluster of mass 1015 M⊙, assuming a constant jet efficiency of 0.2. This argument complements accretion-based upper limits on SMBH masses (Natarajan & Treister 2009; King 2016). Such a correlation between central cluster entropy and black hole mass could, however, be weakened by variable efficiencies (González Villalba et al. 2025) caused by a scatter in black hole spins (Sala et al. 2024) or environmental dependences of jet propagation.

We carried out three-dimensional hydrodynamical simulations of an idealised Perseus-like galaxy cluster with AGN jets and find that an increasing SMBH mass implies an elevated central entropy value, for a fixed AGN jet efficiency. We found that successfully reproducing the predictions of our analytic model required corrections for elevated jet entropies when calculating X-ray emissivity-weighted cluster entropies. We note that our sub-grid model for SMBH accretion couples to the combined entropy of the ambient ICM and the jet. By construction, this reduces the Bondi accretion rate and, together with the more preventive nature of jet feedback compared to a ‘kinetic-wind model’, leads to a gentler heating of the surrounding ICM (Weinberger et al. 2023), thereby enabling the formation of cool cores with central entropies well below 30 keV cm2. The ability to displace part of the material in the accretion region while keeping some ICM gas in place is a consequence of details in the numerical choices of the employed jet model and prevents an over-heating to entropies above 30 keV cm2 in Fig. 1. Notably, this behaviour is not guaranteed in other feedback models, and heating to non-cool-core states can occur.

Our findings have important implications for cosmological models of galaxy cluster evolution that are simulated with a ‘kinetic-wind model’ (Weinberger et al. 2017b). We have shown that high AGN feedback efficiencies in combination with overmassive SMBHs (either via overly optimistic accretion histories or via the over-merging of massive SMBHs; Bahé et al. 2022) lead to central entropies in massive galaxy clusters that exceed the cool-core threshold. We speculate that the absence or rarity in particular of strong, high-mass cool-core clusters in some simulation models (e.g. Pakmor et al. 2023) can indeed be explained by this effect. Future work will further address the role of cosmological assembly and halo growth on the equilibrium state discussed here. Note that the efficiency parameter in this work, ϵ, represents the product of a possible Bondi-boost factor, the radiative efficiency (in some models), and the feedback efficiency (Weinberger et al. 2017b; Henden et al. 2018).

Finally, the analytic scaling of core entropy with SMBH mass presented in this work heavily relies on our assumptions of a Bondi-like accretion. This approach was used to account for the behaviour seen in hydrodynamical simulations, which frequently utilise a version of this formula. Future work will extend this study to alternative accretion models (Weinberger et al. 2025) and investigate the physical origin of the relatively small differences reported between chaotic cold accretion and Bondi accretion in galaxy cluster simulations (Meece et al. 2017; Ehlert et al. 2023).

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous referee for the suggestions that helped to improve the manuscript. RW acknowledges funding of a Leibniz Junior Research Group (project number J131/2022). CP acknowledges support by the European Research Council under ERC-AdG grant PICOGAL-101019746 and from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) as part of the DFG Research Unit FOR5195 – project number 443220636.

References

- Altamura, E., Kay, S. T., Bower, R. G., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 520, 3164 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bahé, Y. M., Schaye, J., Schaller, M., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 516, 167 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D. J., Kay, S. T., Bahé, Y. M., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 471, 1088 [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D. J., Vogelsberger, M., Kannan, R., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 481, 1809 [Google Scholar]

- Binney, J. 2005, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A, 363, 739 [Google Scholar]

- Bîrzan, L., Rafferty, D. A., McNamara, B. R., Wise, M. W., & Nulsen, P. E. J. 2004, ApJ, 607, 800 [Google Scholar]

- Bondi, H. 1952, MNRAS, 112, 195 [Google Scholar]

- Bondi, H., & Hoyle, F. 1944, MNRAS, 104, 273 [Google Scholar]

- Booth, C. M., & Schaye, J. 2010, MNRAS, 405, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, A., & Teyssier, R. 2007, MNRAS, 376, 1547 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cavagnolo, K. W., Donahue, M., Voit, G. M., & Sun, M. 2009, ApJS, 182, 12 [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, I.-N., Ghirardini, V., Liu, A., et al. 2022, A&A, 661, A11 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Churazov, E., Forman, W., Jones, C., & Böhringer, H. 2003, ApJ, 590, 225 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, R. J. H., & Fabian, A. C. 2006, MNRAS, 373, 959 [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R. 2004, New Astron. Rev., 48, 843 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert, K., Weinberger, R., Pfrommer, C., Pakmor, R., & Springel, V. 2018, MNRAS, 481, 2878 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlert, K., Weinberger, R., Pfrommer, C., Pakmor, R., & Springel, V. 2023, MNRAS, 518, 4622 [Google Scholar]

- Fabian, A. C. 2012, ARA&A, 50, 455 [Google Scholar]

- Fabian, A. C., Ferland, G. J., Sanders, J. S., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 515, 3336 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk, C. S., White, S. D. M., Bode, P., et al. 1999, ApJ, 525, 554 [Google Scholar]

- González Villalba, J. A., Dolag, K., & Biffi, V. 2025, A&A, 694, A232 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Henden, N. A., Puchwein, E., Shen, S., & Sijacki, D. 2018, MNRAS, 479, 5385 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Martínez, E., Dolag, K., Steinwandel, U. P., et al. 2025, A&A, submitted [arXiv:2507.15858] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavacek-Larrondo, J., McDonald, M., Benson, B. A., et al. 2015, ApJ, 805, 35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, F., & Lyttleton, R. A. 1939, Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc., 35, 405 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, D. S., Mittal, R., Reiprich, T. H., et al. 2010, A&A, 513, A37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- King, A. 2016, MNRAS, 456, L109 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lehle, K., Nelson, D., Pillepich, A., Truong, N., & Rohr, E. 2024, A&A, 687, A129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mantz, A., Allen, S. W., Ebeling, H., Rapetti, D., & Drlica-Wagner, A. 2010, MNRAS, 406, 1773 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, B. R., & Nulsen, P. E. J. 2007, ARA&A, 45, 117 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara, B. R., & Nulsen, P. E. J. 2012, New J. Phys., 14, 055023 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meece, G. R., Voit, G. M., & O’Shea, B. W. 2017, ApJ, 841, 133 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan, P., & Treister, E. 2009, MNRAS, 393, 838 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nulsen, P. 2004, in The Riddle of Cooling Flows in Galaxies and Clusters of galaxies, eds. T. Reiprich, J. Kempner, & N. Soker, 259 [Google Scholar]

- Pakmor, R., Springel, V., Coles, J. P., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 524, 2539 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J. R., & Fabian, A. C. 2006, Phys. Rep., 427, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J. R., Kahn, S. M., Paerels, F. B. S., et al. 2003, ApJ, 590, 207 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pfrommer, C., Chang, P., & Broderick, A. E. 2012, ApJ, 752, 24 [Google Scholar]

- Sala, L., Valentini, M., Biffi, V., & Dolag, K. 2024, A&A, 685, A92 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sijacki, D., & Springel, V. 2006, MNRAS, 366, 397 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sijacki, D., Pfrommer, C., Springel, V., & Enßlin, T. A. 2008, MNRAS, 387, 1403 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vikhlinin, A., Kravtsov, A., Forman, W., et al. 2006, ApJ, 640, 691 [Google Scholar]

- Voit, G. M., & Donahue, M. 2005, ApJ, 634, 955 [Google Scholar]

- Voit, G. M., & Donahue, M. 2015, ApJ, 799, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Voit, G. M., Kay, S. T., & Bryan, G. L. 2005, MNRAS, 364, 909 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, R., Ehlert, K., Pfrommer, C., Pakmor, R., & Springel, V. 2017a, MNRAS, 470, 4530 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, R., Springel, V., Hernquist, L., et al. 2017b, MNRAS, 465, 3291 [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, R., Su, K.-Y., Ehlert, K., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 523, 1104 [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger, R., Bhowmick, A., Blecha, L., et al. 2025, A&A, 700, A52 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Entropy profiles of X-ray-emitting gas of Perseus analogue self-regulated simulations with different SMBH masses (see legend). The coloured area indicates the 16th to 84th percentile of snapshots at times between t = 0.55 Gyr and t = 1 Gyr. The dotted line denotes 30 keV cm2, an empirical dividing line between cool-core and non-cool-core clusters. The dashed line denotes the entropy profile of the Perseus cluster from Churazov et al. (2003), rescaled to h = 0.67. The central entropy establishes an equilibrium value that is dependent on SMBH mass. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Temperature vs density phase diagram, colour-coded by mass. The grey line indicates an electron entropy of 30 keV cm2, and the dashed orange line indicates the equilibrium ICM entropy predicted by our model (see text for details). Most of the gas mass is above our equilibrium entropy value, implying that efficient AGN jet feedback sets a SMBH mass-dependent entropy floor in the central ICM. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.