| Issue |

A&A

Volume 700, August 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A147 | |

| Number of page(s) | 11 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202453098 | |

| Published online | 19 August 2025 | |

The mixing of internal gravity waves and lithium production in intermediate-mass asymptotic giant branch stars

School of Physical Science and Technology, Xinjiang University,

Urumqi

830046,

China

★ Corresponding authors: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

20

November

2024

Accepted:

19

June

2025

Context. Intermediate-mass asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars may have significant influence in the evolution of lithium (Li) in the Galaxy. During the AGB phase, stars eject surface material into interstellar matter (ISM) by stellar winds, and the Li content in their surfaces and winds decisively influences the AGB stars’ contribution of Li to ISM. Turbulent convection within stars - driven by internal gravity waves (IGWs) excited by convective motions - can transmit energy outward and induce mixing in non-convective regions, profoundly affecting the chemical composition of stellar surfaces and winds.

Aims. We aim to investigate the effects of IGWs on Li production of the AGB stars. We intend to demonstrate the validity of extra mixing triggered by IGWs in the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope of intermediatemass AGB stars and investigate its impact on Li production in these stars. In this paper, we use this model combined with initial mass functions to derive the total Li production from intermediate-mass AGB stars.

Methods. We used the Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics to construct stellar models from the zero-age main sequence to the end of the AGB. This simulation incorporated IGW-induced mixing coefficients and element diffusion effects. Grids were established to calculate the production of Li for AGB stars with different masses and metallicities. Subsequently, employing the method of population synthesis, we used linear interpolation in grids to estimate the contribution rate of Li production to the Galactic Li from a sample size of 107 stars.

Results. Simulated results demonstrate that IGWs triggered during each Helium-shell flash induces extra mixing in non-convective regions. In our model, an IGW induces extra mixing that transports material from the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope to the convective envelope, allowing 7Be originally located below the convective envelope to be transported into the convective envelope, where 7Be decays into 7Li. The positive effects of IGW mixing on the Li yield diminish with increasing initial mass. For models with the same initial mass, the positive impact of IGW mixing increases with metallicity. In our calculations, most AGB stars with initial masses between 3.5 M⊙ and 7.5 M⊙ can produce a positive Li yields. Using the synthesispopulation method, we estimate that the total Li yields produced by AGB stars with IGW mixing are of about 15 M⊙, which is twice that without IGW mixing. The contribution of these models to total galactic Li is around 10%. It means that an AGB star may be a non-negligible source for Li production.

Conclusions. Through this extra-mixing mechanism induced by IGWs, AGB stars can achieve a maximum A(Li) over 5, and intermediate-mass AGB stars significantly contribute to Li in the Galactic ISM. These findings underscore the crucial role of IGWs in stellar evolution, particularly in enhancing Li production.

Key words: stars: abundances / stars: AGB and post-AGB / stars: evolution / ISM: abundances

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Lithium (Li) is one of the three elements formed during the Big Bang. As the age of the Universe advances, the abundance of Li in interstellar matter (ISM) has risen from the primordial Li abundance formed during the Big Bang, A(Li)=2.72 (Życzkowski et al. 1998; Coc et al. 2014), to the current meteorite abundance A(Li)=3.26 (Asplund et al. 2009; Lodders et al. 2009). Prantzos (2012) considered that half of the Galactic Li comes from stars; this includes low-mass red giants (initial mass between 1 ~ 2 M⊙), asymptotic giant branch (AGB) stars (initial mass between 2 and 6 M⊙), and novae. Otherwise, AGB stars with initial mass over 6 M⊙ also exhibit higher Li production (Ventura & D’Antona 2010; Lau et al. 2012). This indicates that AGB stars with masses between 2 and 8 M⊙ are all potential contributors to significant Li enrichment in the Galaxy, especially the intermediate-mass AGB stars capable of undergoing the hot-bottom-burning (HBB) process, with initial masses between 3 M⊙ (depending on metallicities) and 8 M⊙ (Travaglio et al. 2001; Karakas & Lugaro 2016). Current research results indicate that novae explosions contribute the most to the production of the Galactic Li. Estimates from various studies have suggested a lower bound of 10% (Rukeya et al. 2017; Starrfield et al. 2024) to a higher bound 70% (Gao et al. 2024). A Li-rich Giant (for which A(Li) is >1.5) (Iben 1967) could also be a potential source of Li. Extensive observational evidence confirms that low-mass red giants during the red clump after the helium flash(He-flash) can also enter a Li-rich or even super-Li-rich phase (Yan et al. 2018; Deepak & Reddy 2019; Singh et al. 2019; Kumar & Reddy 2020; Singh et al. 2021; Martell et al. 2021). However, they have low mass-loss rates, and their Li-rich phase only lasts for a short time. Stellar models of intermediate initial mass that experience the AGB are considered to be potential sources of Li (Sackmann & Boothroyd 1992; Ventura & D’Antona 2009). In the stellar interior, the production of Li primarily comes from the decay of 7Be, and the production of 7Be depends on the 3He(α, γ)7Be reaction, which occurs at temperatures over 4 × 107 K. 7Be(p, α)4He occurs at temperatures over 8 × 107 K, and 7Be decays into 7Li through nuclear reactions. 7Be(p, α)4He occurs at temperatures over 8 × 107 K, and 7Be decays into 7Li through nuclear reactions, 7Be(e, v)7Li, with a half-life of 53 days at low temperatures (Fowler et al. 1955; Cameron 1955; Simonucci et al. 2013). Otherwise, 7Li is destroyed when a temperature is higher than 2.5 × 106 K. It means that 7Li hardly survives in the stellar interior where 7Be is produced. Therefore, Cameron & Fowler proposed that 7Be produced in the stellar interior must be transported rapidly into the cool envelope (where the temperature is lower than 2.5 × 106 K) via convection to prevent the decay-generated 7Li from being destroyed, which is called the Cameron & Fowler(CF) mechanism (Cameron & Fowler 1971). Intermediate-mass stars of the thermal-pulses asymptotic giant branch (TP-AGB) have temperatures at the bottom of their convective envelopes high enough to trigger nuclear reactions producing 7Be and the CNO cycle, leading to the HBB process. These stars transport nuclear-reaction products to the stellar surface via convection, resulting in Li-rich and O-rich stars(C/O < 1 in surface). The discovery of Li-rich AGB stars with S-process enrichment and O-rich compositions in the Magellanic Cloud (MC) has confirmed this theory (Wood et al. 1983; Smith & Lambert 1989, 1990; Plez et al. 1993). In previous investigations, the Li production in AGB stars was found to be influenced by parameters such as convection, mixing, and mass-loss rates. Higher mass-loss rates generally lead to greater Li production (Travaglio et al. 2001; Romano et al. 2001). Based on the IRAS two-colour diagram, García-Hernández et al. (2007, 2013) and Pérez-Mesa et al. (2019) detected the Li abundances of 30 O-rich AGB stars in the Milky Way. They found that 14 of them are Li-rich AGB stars, and the highest A(Li) among these stars reaches 4.3 dex. Spectral analysis indicates that all samples within the Milky Way exhibit a mass-loss rate of less than 10−6 M⊙ yr−1 (Zamora et al. 2014; Pérez-Mesa et al. 2017, 2019). The presence of Li-rich and O-rich stars confirm that these stars have undergone the HBB process. This observational result confirms the unreliability of simulation results under conditions of high mass-loss rates. The treatment of convection has also been a critical factor influencing Li production. Bigger mixing length parameters lead to the higher efficiency of convection (Canuto et al. 1996). On the other hand, theoretically, full-spectrum-of-turbulence models (Canuto & Mazzitelli 1991) with higher convection efficiency also exhibit higher A(Li) during the HBB process (Mazzitelli et al. 1999; Ventura & D’Antona 2005). Furthermore, some extra-mixing mechanisms have been shown to effectively enhance surface 7Li abundance in the AGB, such as thermohaline mixing (Stancliffe et al. 2010; Martell et al. 2021), proton ingestion events in low-mass stars (Iwamoto et al. 2004; Choplin et al. 2024), and rotationally induced mixing (Talon & Charbonnel 1998). Magnetic and internal gravitational waves (IGWs) are also considered as possible sources of an extra-mixing mechanism (Lagarde & Charbonnel 2010). During the TP-AGB stage, stars have both the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope. Through the convective envelope, they transport nuclear reaction products from the interior to the surface and eventually eject these products into the ISM. The convective thermal pulse primarily occurs within the helium shell (He shell) during helium burning (He burning). Stars in the TP-AGB experience a cycle where the He shell is repeatedly ignited until the outer envelopes are completely ejected. With each pulse, the peak luminosity during He-shell burning increases.

The IGW triggered by turbulent convection within stars is considered one of the reasons for the onset of the extra-mixing mechanism (Montalban 1994). The ignition process of the He shell in stars in the AGB creates conditions for the excitation of IGWs. This leads to the generation of an extra-mixing coefficient in the non-convective zones of stars, bringing 7Li to the surface and ultimately enhancing Li production. To our knowledge, there are seldom any investigations into the effect of IGWs on Li yields for intermediate-mass AGB stars.

In this paper, we demonstrate that the excitation of IGWs during He-shell burning can induce mixing in the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse to the convective envelope. We provide the production of Li and its contribution to the Galactic Li mass under reliable mass-loss rate simulations. Section 2 introduces model parameters and demonstrates the validity of IGW-induced mixing. Section 3 demonstrates the impact of mixing mechanisms on Li production in AGB stars and compares our results with observations. In Section 4, we present the conclusions of this study.

2 Model

We used Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astro-physics (MESA,[rev22.11.1]; (Paxton et al. 2011, 2013, 2015, 2018, 2019; Paxton 2021)) to construct one-dimensional intermediate-mass stellar models. MESA adopts the equation of state of Rogers & Nayfonov (2002) and Timmes & Swesty (2000) and the opacity of Iglesias & Rogers (1993, 1996) and Ferguson et al. (2005).

2.1 Model parameters

Different metallicities are selected as Z=0.014, Z=0.004, Z=0.0014, and Z=0.00014. Stellar initial masses in the models are 3.5 M⊙ to 7.5 M⊙ depending on the different metallicities. The convective efficiency inside stars depends on parameter settings. In our model, the mixing-length parameter is set as 1.9.

2.1.1 Overshooting

Exponential overshooting at the bottom of both the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope also to be considered. According to Herwig (2000) and Freytag et al. (1996), the diffusion coefficient in the overshooting region is

(1)

(1)

Here, D0 is the diffusion coefficient at the boundary of the convection zone, z is the distance to the boundary of convection zone, and Hp is the pressure scale height. Following Herwig et al. (1999), the overshooting parameter, f, is set as 0.016.

2.1.2 Nuclear network

For the nuclear network, we used AGB.net, which includes nuclear reactions from 1H to 22Ne. We adopted nuclear reaction rates compiled by JINA REACLIB (Cyburt et al. 2010). The 7Be(e, v)7Li reaction was adopted by Simonucci et al. (2013); before that, it was made available in machine-readable form by Vescovi et al. (2019). This reaction rate incorporates a revision to the electron capture rate at temperatures below 107 K. Our treatment of electron screening is based on Alastuey & Jancovici (1978) and Itoh et al. (1979).

2.1.3 Mass-loss prescription

The mass-loss formula in Bloecker (1995) (B95) was adopted for the AGB. The mass-loss rate is given by

(2)

(2)

where MR is given by Reimers (1975):

(3)

(3)

Here, η is a dimensionless free parameter scaling the massloss efficiency. We set η=0.01. This value has been adopted in multiple previous models (Romano et al. 2001; Ventura et al. 2000).

2.1.4 Element-diffusion mechanism

Element diffusion was also considered; this can partially explain the mechanism behind the production of Li-rich giants near the tip of the red giant branch (RGB). The enrichment of Li in these stars can be explained by considering the element diffusion mechanism (Paxton et al. 2015, 2018) within a certain constant diffusion coefficient. This further explains the production mechanism of super-Li-rich giants (Gao et al. 2022). In stellar interiors, the primary factors influencing element diffusion in stars include the pressure gradient (gravity), temperature gradient, composition gradient, and radiation pressure, with gravitational sedimentation being the main driving force. MESA employs the method proposed by Thoul et al. (1994), which solves the entire system of equations defined in Burgers (1969) within a matrix structure without imposing restrictions on the number of elements considered. By inputting the number density, ns; temperature, T; gradients, d ln ns/dr, d ln T/dr; material mass (in atomic mass units), As; mean charge, Zs, of the material in its average ionisation state; and resistive coefficients Kst, z′st, and z″st (Paxton et al. 2015), MESA computes elemental diffusion in stellar interiors, incorporating specific diffusion coefficients derived from Paquette et al. (1986) and Stanton & Murillo (2016).

2.1.5 Initial composition

The contribution of stars to the Galactic Li inventory depends on both Li production during stellar evolution and Li consumption from the ISM during star formation. The initial Li mass in stars is calculated by multiplying the stellar initial mass by the initial Li abundance, which varies with metallicity. In the present work, according to the observations, the initial A(Li) was set to 3.26 for stars with Z=0.014, 2.24 for stars with low-metallicities (Z=0.00014 or Z=0.0014) (Molaro et al. 1997; Spite et al. 1996), and 2.5 for stars with Z = 0.004 (Fulbright 2000; Travaglio et al. 2001). All models begin their evolution from the zero-age main sequence.

2.2 Extra mixing excited by IGWs

During the TP-AGB stage, the He shell undergoes repeated burning and extinguishing cycles. The peak helium luminosity during each burning event gradually increases with each subsequent burning (He-shell flash). During a He-shell flash, the energy produced by the flash powers a convective region (the convective thermal pulse) in the He-burning shell (Karakas & Lattanzio 2014). The hydrogen-rich convective envelope remains in a convective state (the convective envelope). A radiative zone exists between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope throughout the period from the He-shell flash to the third dredge-up process. An IGW is considered to be triggered by internal turbulent convective motions in stars (Press 1981; Lecoanet & Quataert 2013), the energy transmitted outwards by IGWs after overcoming the gravitational potential of a certain region, can lead to that region being in a mixed state. The IGW model has successfully explained variations in Li abundance in solar and low-mass stars (Garcia Lopez & Spruit 1991; Charbonnel & Talon 2005). IGWs triggered during the first He flash in red giants can induce mixing between the hydrogenburning zone and the convective envelope and bring 7Be from the hydrogen-burning zone into the convective envelope (Schwab 2020). This can partially explain the mechanism behind the production of Li-rich giants near the tip of the RGB. The existence of super-Li-rich giants can be further explained by additionally incorporating the element diffusion primarily driven by gravitational settling (Gao et al. 2022) and the neutrino, magnetic, moment-induced extra cooling effect (Lu et al. 2025).

|

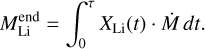

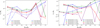

Fig. 1 Helium-luminosity over time during TP-AGB for the Z=0.014, 4M⊙, and 7 M⊙ models. For the x-axis, τAGB represents evolutionary time after the beginning of the AGB phase at which the core He burning is just exhausted. |

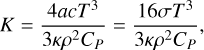

2.2.1 Evidence that IGWs can trigger extra mixing

Here we consider that IGWs triggered by He-shell burning during the TP-AGB phase can also induce mixing in the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope. In Fig. 1, we present the plot showing the heliumluminosity evolution over time for Z=0.014, 4M⊙, and 7 M⊙ stars during the TP-AGB phase. After several initial pulses, the maximum He-burning luminosity during each pulse exceeded 107L⊙. In the final pulses, they may even reach 108L⊙. Press (1981) investigated the mixing induced by IGWs in the stellar interior. In their model, a region with the mixing height H and volume V must overcome gravitational potential energy, which requires energy provided by IGWs of H2N2ρV, where ρ is the density and N is the Brunt-Väisälä frequency. To sustain the mixed state, this energy must be updated within the thermal diffusion timescale H2/K. Dividing the two quantities shows that the power required to maintain mixing is N2KρV, which is independent of the height H. For the unit mass, this value becomes N2K. Therefore, the power Lmix required to sustain a constant mass-mixing state should be equal to

(4)

(4)

where m is the mass, and K is the thermal diffusion coefficient given by

(5)

(5)

where σ = ac/4 is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, T is the temperature, κ is the opacity, and CP is the constant pressure-specific heat capacity.

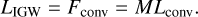

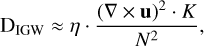

An IGW is triggered by turbulent convection. Based on Lecoanet & Quataert (2013) and Schwab (2020), the wave luminosity of IGWs in convective regions is given by

(6)

(6)

Here, M is the convective Mach number. Lconv means convective luminosity. In order to sustain mixing within a region, the power of the IGW must exceed the threshold, Lmix, required to maintain mixing in that region.

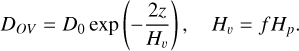

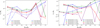

Figure 2 depicts the internal structure of the star shortly after ignition in the He shell. The shaded areas represent the convective regions. This includes the convective thermal pulse inside and the convective envelope outside. A radiative zone exists between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope. Combined with Eq. (4), we took the top of the convective thermal pulse as the lower integration limit and performed a mass integral of N2K. The position of the upper integration limit corresponds to the IGW power required to sustain mixing up to that region. When the upper limit is set at the bottom of the convective envelope, we derived the IGW power needed to maintain mixing across the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope. After normalising the units of luminosity and power, this value is approximately 104L⊙.

In Fig. 2, it can be observed that during the TP-AGB stage of intermediate-mass stars, the LIGW in the He-shell region reaches 104L⊙ to 105L⊙ and exceeds the Lmix value. This implies that IGWs can induce mixing in the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope.

2.2.2 Mixing-coefficient setting

The mixing induced by IGWs requires specific mixing coefficients in each region. Schwab (2020) applied fixed Dmix = 1010 cm2 s−1 and Dmix = 1014 cm2 s−1 in the context of mixing coefficients in low-mass stars. However, artificially setting the diffusion coefficient may not be accurate. In this work, we adopted the framework proposed by Herwig et al. (2023). We used the mixing coefficient Dmix generated by the mixing zone excited by IGWs:

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

where u represents the convective velocity. The dimensionless coefficient η is set to 0.1, with its value determined by 3D hydrodynamical simulations (Garaud & Kulenthirarajah 2016).

Similar to the approach of Schwab (2020) in modelling the first He flash of low-mass stars, we set LHe = 104L⊙ as the threshold for IGW mixing to confine its activation, specifically during the He-shell ignition phase. This luminosity threshold is only exceeded transiently during the brief He-shell ignition event. We applied IGW mixing in the regions where LHe >104L⊙. Additionally, we considered an element diffusion mechanism that is primarily driven by gravity sedimentation (Thoul et al. 1994; Paxton et al. 2018). In this paper, we focused on the diffusion of the eight main elements during the AGB phase, including 1H, 4He, 7Be, 7Li, 12C, 13C, 14N, and 16O.

|

Fig. 2 Internal structure of 4 M⊙ star with Z=0.014 at the moment of He-shell ignition during TP-AGB stage. Here, r is the radial distance from the core and R is the stellar radius. In the upper panel, the values corresponding to the left vertical axis are represented by solid lines, while the dashed lines correspond to the values on the right vertical axis. The lower panel shows Dmix in these zones. The grey shaded area represents the convective zone. Lmix represents the power required to trigger mixing up to this zone. |

3 Results

We demonstrate the impact of IGW-mixing mechanisms on Li production, present a Li-yield grid, estimate the contribution rate of AGB stars to Galactic Li, and compare with observational results.

|

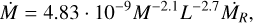

Fig. 3 Internal structure and elemental abundances from convective thermal pulse to the convective envelope in the AGB for 4 M⊙ with Z=0.014. The grey shaded area represents the convective zone, and the middle region is the convection-interruption zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope. The left panel shows the case with IGW mixing considered, and the right panel shows the case without IGW mixing. For the x-axis, Mr represents the Lagrangian mass coordinate; MHe is the Lagrangian mass coordinate of the outer boundary of the convective thermal pulse. |

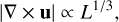

3.1 The impact of IGW mixing on Li abundance

Figure 3 shows a comparison of models with and without consideration of IGW mixing for a star with an initial mass of 4 M⊙ and Z=0.014 by the element abundances, mixing coefficients, temperatures, and convective zones near the He shell during the TP-AGB phase. Without IGW mixing, the mixing in the non-convective regions hardly occurs because of the too low Dmix. Even when considering convective overshooting effects, the mixing region can only expand slightly. As shown by the red line in Fig. 3, there is a large amount of 7Be produced in the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope. Based on the CF mechanism (Fowler et al. 1955; Cameron & Fowler 1971), the region around 4 ~ 8 × 107K is the primary production zone for 7Be. Without IGW mixing, a significant portion of this region is located below the convective envelope; thus, a substantial amount of internal 7Be from this region cannot be transported into the convective envelope. This is particularly evident in stars whose initial masses just about satisfy the requirements for the HBB mechanism. Below the convective envelope, there still exists a region where the temperature is suitable for the 3He(α, γ)7Be(e, v)7Li reaction and where the abundance of 3He is relatively high. This is precisely why this region is enriched with 7Be. In the models with IGW mixing, the mixing in the non-convective regions can also work efficiently because Dmix is higher than 1010 cm2 s−1.

Similarly, Fig. 4 shows the internal structure for 7 M⊙ stars. Although the mixing induced by IGWs in the 7 M⊙ model is similar to that in the 4 M⊙ model, the Li production in the 7 M⊙ model with IGW mixing remains comparable to that without IGW mixing. This occurs because the bottom temperature of the convective envelope in the 7 M⊙ model exceeds 4 × 107 K, satisfying the conditions for 7Be production and enabling efficient Li synthesis even without IGW mixing. For a star with 4 M⊙, the mass of the IGW-mixing region below the convective envelope is approximately 2 × 10−4 M⊙, and the mass of 7Be is about 2 × 10−11 M⊙. In the case of 7 M⊙, the mass of 7Be below the convective zone is only about 10−13 M⊙. Furthermore, the effectiveness of the IGW mixing decreases continuously with an increasing number of pulses. Considering that larger mass stars require more pulses for the He shell to achieve higher helium luminosity, internal 3He may be depleted before IGW mixing effectively operates. On the other hand, larger initial-mass stars have higher temperatures at the bottom of their convective envelope, making the HBB mechanism more effective. Therefore, IGW mixing does not significantly enhance the production of Li in higher initial mass stars.

Figure 5 compares the temporal evolution of surface 7Li abundances and cumulative yields (calculated via Eqs. (9) and (10)) for initial mass between 4 M⊙ and 7 M⊙ stars with and without IGW mixing throughout the entire TP-AGB phase. In our model, the peak value of A(Li) during the AGB phase exceeds 5. This result is consistent with that of Karakas & Lugaro (2016), which prescribed a fixed mixed mass below the convective envelope in AGB models. Based on our simulations, IGW mixing is likely this extra mixing assumed by Karakas & Lugaro (2016). Since the effect of IGW mixing is more efficient in lower mass stars, the Li enhancement effect is most significant in stars whose initial mass only just meets the critical value for the HBB mechanism. We also find that regardless of whether the IGW-mixing mechanism is considered or not, the peak in surface 7Li abundance occurs during the early pulses. While for cases involving IGW mixing, the Li abundance during the same evolutionary phase is higher than that in the models without IGWs. Although the difference remains below 1 dex, the logarithmic nature of the A(Li) scale implies that even a modest difference in abundance corresponds to a significant enhancement in the mass fraction of Li at the stellar surface and in stellar winds. Apart from the 7 M⊙ model, with IGW mixing, the Li production increases by several levels to an order of magnitude compared to scenarios without IGW mixing. Since stellar-mass ejection primarily occurs during the AGB phase, achieving a positive Li yield requires the A(Li) at this time to exceed the initial value by at least a certain amount and to persist for a specific duration. Taking the models with Z=0.014 as an example, combined with the initial A(Li) value of 3.26, the total Li mass ejected by the star over its entire life cycle must exceed 7.27 × 10−9 M⊙. Otherwise, the Li production would be insufficient to compensate for the Li consumed from the ISM during star formation.

|

Fig. 5 Variation of 7Li abundance and total Li yields YLi (subtracting the initial Li mass) over time during the AGB stage for stars of different masses under solar metallicity. We used dashed lines to represent the case without IGW mixing, and the meaning of the x-axis is the same as in Fig. 1. |

3.2 Comparison with observational samples

Based on current observations, there are about 22 Li-rich AGB stars, with 14 located in the Milky Way (Garcíia-Hernández et al. 2013; Pérez-Mesa et al. 2019) and eight in the Magellanic Cloud (Wood et al. 1983; Smith & Lambert 1989, 1990; Plez et al. 1993; Uttenthaler et al. 2011). Their Li abundances, A(Li), are all above 1.5 dex, with R Nor (Uttenthaler et al. 2011) and R Cen (Pérez-Mesa et al. 2019) reaching 4.6 dex and 4.3 dex, respectively. All these stars are O-rich and exhibit s-process element enrichment, suggesting the occurrence of an HBB mechanism. Based on the observations of the Rb 1 7800 Â absorption line, the mass-loss rates of the samples in the Milky Way are all less than 10−6 M⊙ yr−1. When the mass-loss rates exceed 10−6 M⊙ yr−1, the Rb I absorption lines in the Milky Way-observed samples become excessively strong (Zamora et al. 2014; Pérez-Mesa et al. 2017). Fig. 6 shows the evolution of A(Li) on the stellar surface with mass-loss rates. During the AGB phase, the star’s massloss rates increase with each pulse oscillation, accompanied by an increase in Li abundance due to the HBB mechanism and a decrease in Li abundance after the depletion of 3He. In our model, after entering the AGB phase, there is a distinct stage where the mass-loss rates remain below 10−6 M⊙ yr−1. Moreover, under reasonable mass-loss rates, a super-Li-rich phase with A(Li) > 3 can exist.

Figure 7 shows the comparison of our simulation results with observational data for both the Milky Way and the Magellanic Clouds at different metallicities. During the TP-AGB phase, as the number of pulses and time increase, the star’s effective temperature oscillates and gradually decreases. Therefore, the effective temperature can effectively reflect the evolutionary progress of the star during the TP-AGB phase. Our results with or without IGW mixing can cover observational samples well.

|

Fig. 6 Variation of surface 7Li abundance (y-axis) and mass-loss rates (x-axis) during TP-AGB phase for solar-metallicity stars with different initial masses in our model. We indicate the position with a mass-loss rate of 10−6 M⊙ yr−1 with a red dashed line. |

3.3 Li yields for AGB stars

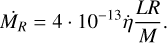

We used the following calculation method to derive Li yields:

(9)

(9)

Here, ***(eq11)*** represents the mass of Li in the star at the initial moment, XLi(t) is the surface Li abundance at time t, Ṁ is the mass-loss rate, and τ is the moment marking the end of the AGB phase of the star. Table 1 gives the results of the net production of Li after the AGB phase for stars with metallicities of Z=0.014, Z=0.004, Z=0.0014, and Z=0.00014 and initial masses ranging from 3.5 M⊙ to 7.5 M⊙. Based on a standard stellar-evolution model, the majority of Li in the whole star is consumed when it undergoes the first dredge-up (Deepak & Reddy 2019; Gao et al. 2022). Therefore, stars are considered as a negative contribution to Li in the ISM. However, based on our results shown in Table 1, the positive contribution to Li in the ISM may appear when the stars have enough mass to undergo the HBB mechanism during the TP-AGB stage. We find that stars with an initial mass just meeting the HBB condition have a relatively high Li production. Li production initially decreases with increasing stellar mass, but rises again for stars above 6 M⊙, this trend being consistent with previous findings (Ventura & D’Antona 2010). For stars with lower initial masses, IGW mixing is more effective. This is not only because the higher temperature at the bottom of the convective envelope overwhelms the IGW-mixing effect in higher mass stars, but also because lower mass stars attain higher helium luminosities during the He shell ignition phase of the TP-AGB. When a star has an initial mass higher than 6 M⊙, the temperature at the bottom of the convective envelope is high enough that 7Be can be directly produced. Therefore, the Li yields rise again. Stars with initial masses between 3.5 and 6 M range exhibit a higher birth rate compared to stars with initial masses above 6 M⊙, and their Li production contributes significantly to the ISM. Overall, the positive impact of IGW mixing generally decreases with increasing stellar mass and might be more pronounced in low-mass stars. Although the IGW mixing mechanism is more pronounced during the RGB and RC phases of low-mass stars, the limited duration of mixing relative to the total evolutionary phases and the low mass-loss rates during these stages may result in insufficient yields to significantly impact the composition of the ISM (Gao et al. 2022).

represents the mass of Li in the star at the initial moment, XLi(t) is the surface Li abundance at time t, Ṁ is the mass-loss rate, and τ is the moment marking the end of the AGB phase of the star. Table 1 gives the results of the net production of Li after the AGB phase for stars with metallicities of Z=0.014, Z=0.004, Z=0.0014, and Z=0.00014 and initial masses ranging from 3.5 M⊙ to 7.5 M⊙. Based on a standard stellar-evolution model, the majority of Li in the whole star is consumed when it undergoes the first dredge-up (Deepak & Reddy 2019; Gao et al. 2022). Therefore, stars are considered as a negative contribution to Li in the ISM. However, based on our results shown in Table 1, the positive contribution to Li in the ISM may appear when the stars have enough mass to undergo the HBB mechanism during the TP-AGB stage. We find that stars with an initial mass just meeting the HBB condition have a relatively high Li production. Li production initially decreases with increasing stellar mass, but rises again for stars above 6 M⊙, this trend being consistent with previous findings (Ventura & D’Antona 2010). For stars with lower initial masses, IGW mixing is more effective. This is not only because the higher temperature at the bottom of the convective envelope overwhelms the IGW-mixing effect in higher mass stars, but also because lower mass stars attain higher helium luminosities during the He shell ignition phase of the TP-AGB. When a star has an initial mass higher than 6 M⊙, the temperature at the bottom of the convective envelope is high enough that 7Be can be directly produced. Therefore, the Li yields rise again. Stars with initial masses between 3.5 and 6 M range exhibit a higher birth rate compared to stars with initial masses above 6 M⊙, and their Li production contributes significantly to the ISM. Overall, the positive impact of IGW mixing generally decreases with increasing stellar mass and might be more pronounced in low-mass stars. Although the IGW mixing mechanism is more pronounced during the RGB and RC phases of low-mass stars, the limited duration of mixing relative to the total evolutionary phases and the low mass-loss rates during these stages may result in insufficient yields to significantly impact the composition of the ISM (Gao et al. 2022).

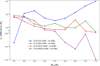

In the last column of Table 1, we show the influence of IGW on the Li yields. Since some models exhibit negative yields, we display difference instead of ratio. We find the positive impact of IGW mixing decreases with increasing initial mass, particularly in terms of the enhancement magnitude for models without IGW mixing. We also note that in the case of low-metallicity models, the yields of some non-IGW models exceed those of the IGW models. This could be attributed to the higher temperature at the bottom of the convective envelope in metal-poor stars, from which even surpasses 8 × 107 K. Under such conditions, the mixing applied in the non-convective zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope actually transports 7Be from the convective envelope into hotter interior regions, where 7Be is depleted. In the previous investigations, Li yields produced by AGB stars have been calculated; this was done by Ventura et al. (2000) and Romano et al. (2001). Fig. 8 gives the comparison between our work and theirs, as well as between our IGW model and the model without IGW mixing. Fig. 9 displays the Li-yield gap with and without IGW mixing across different metallicities and initial masses in our models, using data from the last column of Table 1. Obviously, a comparative analysis between models with and without IGW mixing reveals that the influence of IGW mixing becomes more pronounced at lower initial masses. For systems with reduced metallicity, the overall trend exhibits a slight shift towards even lower mass regimes. In our model, with similar initial mass and metallicity, Li yields in our models are an order of magnitude higher than those in Ventura et al. (2000) and Romano et al. (2001). Notably, in the models with an initial mass of 3.5-5 M⊙, the former is one order of magnitude higher than the latter. The extra mixing triggered by IGWs plays a non-negligible role, which is shown in Figs. 3-5. The yields from some of our models without IGW mixing also exceed those of previous results. This discrepancy could be attributed to revisions in the 7Be(e, v)7Li nuclear reaction rates used by this work, where the Simonucci et al. (2013) reaction rates were adopted. In previous models of Ventura et al. (2000) and Romano et al. (2001), the nuclear reaction rates significantly underestimated the electron capture rates at temperatures below 107 K, which could lead to discrepancies in the calculation of 7Li production.

We employed the synthesis-population method to estimate the Galactic Li yields (Li et al. 2024; He et al. 2024; Lü et al. 2020; Zhu et al. 2023). Based on Chomiuk & Povich (2011), the star formation rate in the Milky Way is 1.9 M⊙ yr−1. Assuming the initial mass function (IMF) of Kroupa (2001), we created 107 single stars, of which 1.6% have masses between 3.5 and 7.5 M⊙. By the linear interpolation in the models with Z=0.014 in Table 1, we were able to estimate the Li yields (YLi) produced by these intermediate-mass AGB stars. Assuming a constant star formation rate and a 13.7 Gyr age for the Milky Way, we can estimate that total Li yields produced by these AGB stars in the Galactic ISM are about 15 M⊙. In our non-IGW models, the total Li yield produced by these AGB stars is 8 M⊙, which is half that of IGW models. In a comparison to the estimates of Ventura et al. (2000) and Romano et al. (2001), the total Li yield in our IGW model is ten times higher than theirs, which we show in Table A.1. Hernanz et al. (1996) and Molaro et al. (2016) estimated that there is about 150 M⊙ Li in the ISM of the Milky Way. The contribution of Li produced by our 3.5 ~ 7.5 M⊙3 AGB stars to the total Li in the ISM is about 10%. Although it may be smaller than the contribution of Li produced by novae (Gao et al. 2024), it is also non-negligible.

Yields (M⊙) and contribution (%) of various sources to Li in the Galactic ISM.

|

Fig. 7 Comparison of observed and modelled Li-rich AGB samples in the Milky Way and the Magellanic Clouds. The upper panel shows the Milky Way sample with effective temperature versus 7Li abundance, with Teff errors of ±100K and 7Li abundance errors of ±0.3dex. The lower panel shows the Magellanic Cloud sample with Teff errors of ±300K and 7Li abundance errors of ±0.5dex. The models with IGW mixing are all displayed on the left, while the models without IGW mixing are displayed on the right. |

|

Fig. 8 Li yields YLi for AGB stars with different initial masses and metallicities. In the left panel, the results with IGW mixing are given by solid coloured lines, while those without IGW mixing are showed by dashed coloured lines. In the right panel, the results of this work are shown by solid coloured lines, while those of other works are shown by dashed coloured lines. |

|

Fig. 9 Li-yield YLi differences (y-axis) with and without IGW mixing under different metallicities and initial mass (x-axis) conditions. |

4 Conclusions

We demonstrate that IGWs excited by the He-shell ignition events in AGB stars can induce extra-mixing in the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope. Using MESA involving an extra mixing triggered by IGW, we investigated the Li-rich AGB stars. In intermediate-mass stars where the HBB mechanism can occur, the IGW mixing extends the mixing region below the convective envelope. This can create an extra transport channel for 7Be and allows more internal 7Be in the radiative zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope to be transported to the convective envelope. The positive effects of IGW mixing diminish with increasing initial mass. For higher mass stars, the temperature at the bottom of the convective envelope is sufficiently high to sustain 7Be production and facilitate its transport to the surface. Consequently, IGW mixing exerts a weaker positive effect on Li yields compared to lower mass stars. Using the IMF and a stellar birth rate in the Milky Way, the total Li yield from AGB stars is calculated to be 15 M⊙, approximately twice that of the non-IGW case. In previous models, AGB stars were not considered significant contributors of Li to the Galaxy under normal massloss rates. Significant contributions of Li to the galaxy from AGB stars require artificially adjusted mass-loss rates, which are often inconsistent with observational constraints. In our model, under normal mass-loss rates, AGB stars make a significant contribution to the Galactic Li. Although it is still lower than the 70% contribution from nova eruptions, for the ISM this is a contribution that cannot be ignored (it reaches 10%).

Acknowledgements

This work received the support of the Nation Natural Science Foundation of China under grants 12163005, U20311204, 12373038, and 12288102; the Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang No. 2022TSYCLJ0006 and 2022D01D85; the Outstanding Graduate Innovation Project of Xinjiang University with No.XJDX2025YJS039; and the science research grants from the china Manned Space Project with No. CMS-CSST-2021-A10.

Appendix A Table with data for the Li yield

The Li yield grid and the effect of IGW mixing on Li yield.

References

- Alastuey, A., & Jancovici, B. 1978, ApJ, 226, 1034 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Asplund, M., Grevesse, N., Sauval, A. J., & Scott, P. 2009, ARA&A, 47, 481 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bloecker, T. 1995, A&A, 297, 727 [Google Scholar]

- Burgers, J. M. 1969, Flow Equations for Composite Gases (New York: Academic Press) [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A. G. W. 1955, ApJ, 121, 144 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A. G. W., & Fowler, W. A. 1971, ApJ, 164, 111 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Canuto, V. M., & Mazzitelli, I. 1991, ApJ, 370, 295 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Canuto, V. M., Goldman, I., & Mazzitelli, I. 1996, ApJ, 473, 550 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Charbonnel, C., & Talon, S. 2005, Science, 309, 2189 [Google Scholar]

- Chomiuk, L., & Povich, M. S. 2011, AJ, 142, 197 [Google Scholar]

- Choplin, A., Siess, L., Goriely, S., & Martinet, S. 2024, Galaxies, 12, 66 [Google Scholar]

- Coc, A., Uzan, J.-P., & Vangioni, E. 2014, J. Cosmology Astropart. Phys., 2014, 050 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cyburt, R. H., Amthor, A. M., Ferguson, R., et al. 2010, ApJS, 189, 240 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Deepak, & Reddy, B. E. 2019, MNRAS, 484, 2000 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J. W., Alexander, D. R., Allard, F., et al. 2005, ApJ, 623, 585 [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, W. A., Burbidge, G. R., & Burbidge, E. M. 1955, ApJ, 122, 271 [Google Scholar]

- Freytag, B., Ludwig, H. G., & Steffen, M. 1996, A&A, 313, 497 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Fulbright, J. P. 2000, AJ, 120, 1841 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J., Zhu, C., Yu, J., et al. 2022, A&A, 668, A126 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J., Zhu, C., Lü, G., et al. 2024, ApJ, 971, 4 [Google Scholar]

- Garaud, P., & Kulenthirarajah, L. 2016, ApJ, 821, 49 [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, D. A., García-Lario, P., Plez, B., et al. 2007, A&A, 462, 711 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, D. A., Zamora, O., Yagüe, A., et al. 2013, A&A, 555, L3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Lopez, R. J., & Spruit, H. C. 1991, ApJ, 377, 268 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- He, G., Zhu, C., Lü, G., et al. 2024, Res. Astron. Astrophys., 24, 105007 [Google Scholar]

- Hernanz, M., Jose, J., Coc, A., & Isern, J. 1996, ApJ, 465, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig, F. 2000, A&A, 360, 952 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig, F., Blöcker, T., Langer, N., & Driebe, T. 1999, A&A, 349, L5 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Herwig, F., Woodward, P. R., Mao, H., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 525, 1601 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iben, I. Jr. 1967, ApJ, 147, 624 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, C. A., & Rogers, F. J. 1993, ApJ, 412, 752 [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, C. A., & Rogers, F. J. 1996, ApJ, 464, 943 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, N., Totsuji, H., Ichimaru, S., & Dewitt, H. E. 1979, ApJ, 234, 1079 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto, N., Kajino, T., Mathews, G. J., Fujimoto, M. Y., & Aoki, W. 2004, ApJ, 602, 377 [Google Scholar]

- Karakas, A. I., & Lattanzio, J. C. 2014, PASA, 31, e030 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Karakas, A. I., & Lugaro, M. 2016, ApJ, 825, 26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kroupa, P. 2001, MNRAS, 322, 231 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, Y. B., & Reddy, B. E. 2020, J. Astrophys. Astron., 41, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lagarde, N., & Charbonnel, C. 2010, in SF2A-2010: Proceedings of the Annual meeting of the French Society of Astronomy and Astrophysics, eds. S. Boissier, M. Heydari-Malayeri, R. Samadi, & D. Valls-Gabaud, 253 [Google Scholar]

- Lau, H. H. B., Doherty, C. L., Gil-Pons, P., & Lattanzio, J. C. 2012, Mem. Soc. Astron. Ital. Suppl., 22, 247 [Google Scholar]

- Lecoanet, D., & Quataert, E. 2013, MNRAS, 430, 2363 [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., Zhu, C., Lü, G., et al. 2024, ApJ, 969, 160 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lodders, K., Palme, H., & Gail, H. P. 2009, Landolt Börnstein, 4B, 712 [Google Scholar]

- Lü, G., Zhu, C., Wang, Z., et al. 2020, ApJ, 890, 69 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X., Zhu, C., Lü, G., et al. 2025, Phys. Rev. D, 111, 103004 [Google Scholar]

- Martell, S. L., Simpson, J. D., Balasubramaniam, A. G., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 5340 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzitelli, I., D’Antona, F., & Ventura, P. 1999, A&A, 348, 846 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Molaro, P., Bonifacio, P., & Pasquini, L. 1997, MNRAS, 292, L1 [Google Scholar]

- Molaro, P., Izzo, L., Mason, E., Bonifacio, P., & Della Valle, M. 2016, MNRAS, 463, L117 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Montalban, J. 1994, A&A, 281, 421 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette, C., Pelletier, C., Fontaine, G., & Michaud, G. 1986, ApJS, 61, 177 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B. 2021, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5798242 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Bildsten, L., Dotter, A., et al. 2011, ApJS, 192, 3 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Cantiello, M., Arras, P., et al. 2013, ApJS, 208, 4 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Marchant, P., Schwab, J., et al. 2015, ApJS, 220, 15 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Schwab, J., Bauer, E. B., et al. 2018, ApJS, 234, 34 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton, B., Smolec, R., Schwab, J., et al. 2019, ApJS, 243, 10 [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Mesa, V., Zamora, O., García-Hernández, D. A., et al. 2017, A&A, 606, A20 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Mesa, V., Zamora, O., García-Hernández, D. A., et al. 2019, A&A, 623, A151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Plez, B., Smith, V. V., & Lambert, D. L. 1993, ApJ, 418, 812 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prantzos, N. 2012, A&A, 542, A67 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Press, W. H. 1981, ApJ, 245, 286 [Google Scholar]

- Reimers, D. 1975, in Problems in Stellar Atmospheres and Envelopes, eds. B. Baschek, W. H. Kegel, & G. Traving, 229 [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, F. J., & Nayfonov, A. 2002, ApJ, 576, 1064 [Google Scholar]

- Romano, D., Matteucci, F., Ventura, P., & D’Antona, F. 2001, A&A, 374, 646 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rukeya, R., Lü, G., Wang, Z., & Zhu, C. 2017, PASP, 129, 074201 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sackmann, I. J., & Boothroyd, A. I. 1992, ApJ, 392, L71 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab, J. 2020, ApJ, 901, L18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Simonucci, S., Taioli, S., Palmerini, S., & Busso, M. 2013, ApJ, 764, 118 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R., Reddy, B. E., Bharat Kumar, Y., & Antia, H. M. 2019, ApJ, 878, L21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R., Reddy, B. E., Campbell, S. W., Kumar, Y. B., & Vrard, M. 2021, ApJ, 913, L4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V. V., & Lambert, D. L. 1989, ApJ, 345, L75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, V. V., & Lambert, D. L. 1990, ApJ, 361, L69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spite, M., Francois, P., Nissen, P. E., & Spite, F. 1996, A&A, 307, 172 [Google Scholar]

- Stancliffe, R. J., Angelou, G. C., & Lattanzio, J. C. 2010, in IAU Symposium, 268, Light Elements in the Universe, eds. C. Charbonnel, M. Tosi, F. Primas, & C. Chiappini, 405 [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, L. G., & Murillo, M. S. 2016, Phys. Rev. E, 93, 043203 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Starrfield, S., Bose, M., Iliadis, C., et al. 2024, ApJ, 962, 191 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Talon, S., & Charbonnel, C. 1998, A&A, 335, 959 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Thoul, A. A., Bahcall, J. N., & Loeb, A. 1994, ApJ, 421, 828 [Google Scholar]

- Timmes, F. X., & Swesty, F. D. 2000, ApJS, 126, 501 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Travaglio, C., Randich, S., Galli, D., et al. 2001, ApJ, 559, 909 [Google Scholar]

- Uttenthaler, S., van Stiphout, K., Voet, K., et al. 2011, A&A, 531, A88 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, P., & D’Antona, F. 2005, A&A, 431, 279 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, P., & D’Antona, F. 2009, A&A, 499, 835 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, P., & D’Antona, F. 2010, MNRAS, 402, L72 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura, P., D’Antona, F., & Mazzitelli, I. 2000, A&A, 363, 605 [Google Scholar]

- Vescovi, D., Piersanti, L., Cristallo, S., et al. 2019, A&A, 623, A126 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, P. R., Bessell, M. S., & Fox, M. W. 1983, ApJ, 272, 99 [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.-L., Shi, J.-R., Zhou, Y.-T., et al. 2018, Nat. Astron., 2, 790 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zamora, O., García-Hernández, D. A., Plez, B., & Manchado, A. 2014, A&A, 564, L4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C.-H., Lü, G.-L., Lu, X.-Z., & He, J. 2023, Res. Astron. Astrophys., 23, 025021 [Google Scholar]

- Życzkowski, K., Horodecki, P., Sanpera, A., & Lewenstein, M. 1998, Phys. Rev. A, 58, 883 [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Helium-luminosity over time during TP-AGB for the Z=0.014, 4M⊙, and 7 M⊙ models. For the x-axis, τAGB represents evolutionary time after the beginning of the AGB phase at which the core He burning is just exhausted. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Internal structure of 4 M⊙ star with Z=0.014 at the moment of He-shell ignition during TP-AGB stage. Here, r is the radial distance from the core and R is the stellar radius. In the upper panel, the values corresponding to the left vertical axis are represented by solid lines, while the dashed lines correspond to the values on the right vertical axis. The lower panel shows Dmix in these zones. The grey shaded area represents the convective zone. Lmix represents the power required to trigger mixing up to this zone. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Internal structure and elemental abundances from convective thermal pulse to the convective envelope in the AGB for 4 M⊙ with Z=0.014. The grey shaded area represents the convective zone, and the middle region is the convection-interruption zone between the convective thermal pulse and the convective envelope. The left panel shows the case with IGW mixing considered, and the right panel shows the case without IGW mixing. For the x-axis, Mr represents the Lagrangian mass coordinate; MHe is the Lagrangian mass coordinate of the outer boundary of the convective thermal pulse. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Similar to Fig. 3, but for 7 M⊙ models. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Variation of 7Li abundance and total Li yields YLi (subtracting the initial Li mass) over time during the AGB stage for stars of different masses under solar metallicity. We used dashed lines to represent the case without IGW mixing, and the meaning of the x-axis is the same as in Fig. 1. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Variation of surface 7Li abundance (y-axis) and mass-loss rates (x-axis) during TP-AGB phase for solar-metallicity stars with different initial masses in our model. We indicate the position with a mass-loss rate of 10−6 M⊙ yr−1 with a red dashed line. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Comparison of observed and modelled Li-rich AGB samples in the Milky Way and the Magellanic Clouds. The upper panel shows the Milky Way sample with effective temperature versus 7Li abundance, with Teff errors of ±100K and 7Li abundance errors of ±0.3dex. The lower panel shows the Magellanic Cloud sample with Teff errors of ±300K and 7Li abundance errors of ±0.5dex. The models with IGW mixing are all displayed on the left, while the models without IGW mixing are displayed on the right. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Li yields YLi for AGB stars with different initial masses and metallicities. In the left panel, the results with IGW mixing are given by solid coloured lines, while those without IGW mixing are showed by dashed coloured lines. In the right panel, the results of this work are shown by solid coloured lines, while those of other works are shown by dashed coloured lines. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Li-yield YLi differences (y-axis) with and without IGW mixing under different metallicities and initial mass (x-axis) conditions. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.