| Issue |

A&A

Volume 700, August 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A209 | |

| Number of page(s) | 17 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555463 | |

| Published online | 21 August 2025 | |

Beyond traditional diagnostics: Identifying active galactic nuclei using spectral energy distribution fitting in DESI data

1

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna (ULL), 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

2

Institute of Space Sciences (ICE, CSIC), Campus UAB, Carrer de Can Magrans, s/n, 08193 Barcelona, Spain

3

Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), c/ Esteve Terradas 1, Edifici RDIT, Campus PMT-UPC, 08860 Castelldefels, Spain

4

Department of Physics & Astronomy, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK

5

Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation, University of Portsmouth, Dennis Sciama Building, Portsmouth PO1 3FX, UK

6

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Siena College, 515 Loudon Road, Loudonville, NY 12211, USA

7

National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences, A20 Datun Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, P. R. China

8

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, 1 Cyclotron Road, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA

9

Department of Physics, Boston University, 590 Commonwealth Avenue, Boston, MA 02215, USA

10

Dipartimento di Fisica Aldo Pontremoli, Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Celoria 16, I-20133 Milano, Italy

11

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, Via Brera 28, 20122 Milano, Italy

12

Department of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Utah, 115 South 1400 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, USA

13

Instituto de Física, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Circuito de la Investigación Científica, Ciudad Universitaria, Cd. de México C. P. 04510, Mexico

14

NSF NOIRLab, 950 N. Cherry Ave., Tucson, AZ 85719, USA

15

Departamento de Física, Universidad de los Andes, Cra. 1 No. 18A-10, Edificio Ip, CP 111711 Bogotá, Colombia

16

Observatorio Astronómico, Universidad de los Andes, Cra. 1 No. 18A-10, Edificio H, CP 111711 Bogotá, Colombia

17

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, PO Box 500 Batavia, IL 60510, USA

18

Department of Physics, The University of Texas at Dallas, 800 W. Campbell Rd., Richardson, TX 75080, USA

19

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Irvine 92697, USA

20

Sorbonne Université, CNRS/IN2P3, Laboratoire de Physique Nucléaire et de Hautes Energies (LPNHE), FR-75005 Paris, France

21

Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats, Passeig de Lluís Companys, 23, 08010 Barcelona, Spain

22

Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Edifici Cn, Campus UAB, 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona), Spain

23

Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (CSIC), Glorieta de la Astronomía, s/n, E-18008 Granada, Spain

24

Departament de Física, EEBE, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, c/Eduard Maristany 10, 08930 Barcelona, Spain

25

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Sejong University, 209 Neungdong-ro, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 05006, Republic of Korea

26

CIEMAT, Avenida Complutense 40, E-28040 Madrid, Spain

27

Department of Physics, University of Michigan, 450 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA

28

University of Michigan, 500 S. State Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA

29

Department of Physics & Astronomy, Ohio University, 139 University Terrace, Athens, OH 45701, USA

⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

9

May

2025

Accepted:

4

June

2025

Aims. Active galactic nuclei (AGN) are typically identified through their distinctive X-ray or radio emissions, mid-infrared (MIR) colors, or emission lines. However, each method captures different subsets of AGN due to signal-to-noise (S/N) limitations, redshift coverage, and extinction effects, underscoring the necessity for a multiwavelength approach for comprehensive AGN samples. This study explores the effectiveness of spectral energy distribution (SED) fitting as a robust method for AGN identification.

Methods. Using CIGALE optical-MIR SED fits on DESI Early Data Release galaxies, we compare SED-based AGN selection (AGNFRAC ≥ 0.1) with traditional methods including BPT diagrams, WISE colors, X-ray, and radio diagnostics.

Resuts. The SED fitting identifies ∼70% of narrow- and broad-line AGN and 87% of WISE-selected AGN. Incorporating high S/N WISE photometry reduces star-forming galaxy contamination from 62% to 15%. Initially, ∼50% of SED-AGN candidates are undetected by standard methods, but additional diagnostics classify ∼85% of these sources, revealing low-ionization nuclear emission-line regions and retired galaxies potentially representing evolved systems with weak AGN activity. Further spectroscopic and multiwavelength analysis will be essential to determine the true AGN nature of these sources.

Conclusions. SED fitting provides complementary AGN identification, unifying multiwavelength AGN selections. This approach enables more complete – albeit somewhat contaminated – AGN samples, which are essential for upcoming large-scale surveys where spectroscopic diagnostics may be limited.

Key words: catalogs / galaxies: active / galaxies: evolution / galaxies: general / galaxies: nuclei / galaxies: Seyfert

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Supermassive black holes with masses of more than a million times that of the Sun (e.g., Kormendy & Ho 2013) are believed to inhabit the centers of galaxies, including the Milky Way (e.g., Ghez et al. 2008; Genzel et al. 2010). Despite the key role supermassive black holes are thought to play in galaxy formation and evolution, determining their origin and impact on host galaxies remains a major challenge in modern astrophysics. When supermassive black holes actively accrete as active galactic nuclei (AGN), they are brighter and easier to detect and thus serve as proxies for studying supermassive black hole properties. Thus, identifying AGNs is crucial for understanding galaxy evolution, black hole growth, and cosmic feedback processes (see Harrison & Ramos Almeida 2024 for a review).

Despite their important role, establishing a uniform method for identifying AGNs is challenging, as different selection techniques lead to different samples that may not even overlap with each other. The AGNs are usually identified based on: (i) their optical emission lines (e.g., Baldwin et al. 1981; Kewley et al. 2001; Kauffmann et al. 2003) and variability (e.g., Pai et al. 2024), (ii) X-ray emission (e.g., Brandt & Alexander 2015), (iii) mid-infrared (MIR) emission (e.g., Lacy et al. 2004; Stern et al. 2005; Jarrett et al. 2011; Stern et al. 2012; Assef et al. 2013; Lacy et al. 2015; Hviding et al. 2022) and variability (e.g., Bernal et al. 2025), and (iv) radio emission (e.g., Heckman & Best 2014; Padovani 2016; Tadhunter 2016). Optical spectroscopic selection identifies AGNs by detecting broad (BL-AGN, i.e., type 1 AGN) or narrow (NL-AGN, i.e., type 2 AGN) emission lines, indicative of high-energy processes near the black hole (e.g., Baldwin et al. 1981). However, star formation elevated by a diffuse ionized gas, photoionization by hot stars, metallicity (as indicated by strong forbidden lines such as [N II]λ6583, [S II]λ6716, 6731, and [O III]λ5007), or shocks can be misclassified as AGN (e.g., Wylezalek et al. 2018). X-ray selection is highly effective because AGNs typically exhibit strong X-ray emission that is less likely to be contaminated by star formation processes. However, X-ray surveys are often limited by sensitivity and coverage and may miss obscured AGNs (e.g., Gilli et al. 2007; Burlon et al. 2011; Mazzolari et al. 2024). The MIR selection uses color criteria to distinguish AGNs from star-forming galaxies due to the characteristic dust emission heated by the AGNs (Stern et al. 2005; Assef et al. 2013). The high-energy radiation emitted from the accretion disk heats up the surrounding dust, causing it to emit infrared radiation, particularly in the MIR regime (5 − 30 μm). The MIR emission has already proven its usefulness in AGN selection, though it is biased toward the selection of AGNs that dominate over the emission from the host galaxies. Radio selection relies on strong synchrotron emission from relativistic jets, but this method is biased toward radio-loud AGNs, which are a minority of the AGN population. Moreover, radio selection can pick up star-forming regions with strong radio emission (Padovani 2016). To summarize, accurate AGN identification is often challenging, as each of these common methods captures different subsets of the AGN population and is subject to its own limitations and biases.

The aforementioned limitations of traditional selection methods highlight the need for a multiwavelength approach to reliably and comprehensively identify AGNs. The advent of large multiwavelength surveys has triggered the use of spectral energy distribution (SED) fitting to constrain AGNs and their host galaxy properties for statistical samples. Recently, the SED fitting approach has revealed the potential not only to derive reliable properties of AGNs and their host properties (e.g., Marshall et al. 2022; Mountrichas et al. 2021a; Burke et al. 2022; Best et al. 2023), but also to identify AGNs based on their multiwavelength information (e.g., Thorne et al. 2022; Best et al. 2023; Yang et al. 2023; Prathap et al. 2024). The AGN SED modeling techniques are also used as the base for the target selection of forthcoming wide-field spectroscopic surveys such as 4MOST (Merloni et al. 2019) and VLT-MOONS (Maiolino et al. 2020).

In this paper, we identify AGNs in the DESI survey using the CIGALE SED fitting code, modeling optical to MIR photometry for millions of sources across diverse types and redshifts. In particular, DESI has already revealed unprecedented samples of dust-reddened quasars (Fawcett et al. 2023) or changing-look AGNs (Guo et al. 2024a,b, 2025). DESI Value-Added Catalog (VAC) of AGNs selected based on their multiwavelength information (Juneau et al. in preparation) provides so far the largest AGN spectroscopic sample1. This will allow for a more detailed study of the role of AGNs in galaxy evolution.

Our study explores the potential of SED-based AGN identification and assesses the necessity of MIR data in minimizing the misclassification of star-forming galaxies as AGNs. By integrating multiwavelength data, we aim to contribute to a more accurate and complete catalog of AGNs in the DESI survey. The structure of the paper is as follows: In Sect. 2.1, we provide an overview of the DESI data. In Sect. 3, we describe the AGN selection using different standard techniques. Results with discussion are presented in Sect. 4. Lastly, Sect. 5 summarizes the efficiency of SED-based AGN identification.

Throughout this paper, we assume WMAP7 cosmology (Komatsu et al. 2011), with Ωm = 0.272 and H0 = 70.4. We also consider the photometry in AB magnitudes (Oke & Gunn 1983).

2. DESI data

2.1. Overview of DESI

DESI is a robotic, 5000-fiber multiobject spectroscopic surveyor operating on the Mayall 4-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory (DESI Collaboration 2022). DESI is capable of obtaining simultaneous spectra covering a range of 3600 − 9800 Å with a resolution of R = 2000 − 5500 of almost 5000 objects over a ∼3deg2 field (DESI Collaboration 2016a,b; Miller et al. 2023; Poppett et al. 2024). DESI is currently conducting a five-year survey to observe approximately 36 million galaxies (Hahn et al. 2023; Raichoor et al. 2023; Zhou et al. 2023) and 3 million quasars (Chaussidon et al. 2023) over 14 000 deg2 (DESI Collaboration 2024a, 2025). This campaign will provide ten times more spectra than the SDSS (York et al. 2000; Almeida et al. 2023) sample of extragalactic targets and substantially deeper than prior large-area surveys (DESI Collaboration 2024a). With the aim of determining the nature of dark energy, DESI will provide the most precise measurement of the expansion history of the universe ever obtained (Levi et al. 2013).

DESI began operations in December 2020, with a five-month survey validation (SV; DESI Collaboration 2024b) preceding the start of the main survey. The entire SV data, internally known as Fuji, was publicly released as the DESI Early Data Release (EDR; DESI Collaboration 2024a), while the First Data Release (DR1; DESI Collaboration 2025) was released in March 2025. This work relies on the EDR data as the complementary studies of the VAC presented in Siudek et al. (2024). The expansion to DR1 is left for future work. The DR1 already demonstrates the DESI potential through cosmological results from the full-shape analysis (DESI Collaboration 2024c).

The scale of DESI observations is supported by software pipelines and products, which include imaging from the DESI Legacy Imaging Surveys (Zou et al. 2017; Dey et al. 2019), a fully automatic spectroscopic reduction pipeline (Guy et al. 2023; Schlafly et al. 2023), followed by a template-fitting pipeline to derive classifications and redshifts for each targeted source (Redrock2; Anand et al. 2024; Bailey et al. in prep.), and for the special case of quasars (Brodzeller et al. 2023). Redrock provides the redshift (Z), redshift uncertainty (ZERR), a redshift warning bitmask (ZWARN), and a spectral type (SPECTYPE) to every target based on the best fit. The photometry in g, r, and z bands is estimated from the Legacy survey (DR9) images with the Tractor3 inference modeling code (Lang et al. 2016). Mid-infrared photometry is derived via forced photometry of the unWISE co-adds based on this optical model (Meisner et al. 2021).

2.2. DESI EDR VAC of physical properties

The DESI EDR redshift catalog consists of 2 847 435 sources (DESI Collaboration 2024a). For a sample of 1 337 250 galaxies and quasars (with SPECTYPE = GALAXY | QSO) characterized by reliable redshifts (ZWARN = 0 or 4 and that do not have any fiber issues (COADD_FIBERSTATUS = 0), we created a VAC of physical properties, including stellar masses and star formation rates (SFRs) as well as AGN features (Siudek et al. 2024). Here, we present a short summary of the VAC and refer the reader to Siudek et al. (2024) for the full description.

Physical properties of DESI galaxies are derived by performing SED fitting using Code Investigating GALaxy Emission (CIGALE v2022.1; Boquien et al. 2019), relying on the optical-MIR photometry and spectroscopic redshifts. CIGALE has already proven its efficiency in deriving physical properties of galaxies hosting AGN (e.g., Salim et al. 2016; Małek et al. 2018; Osborne & Salim 2024; Csizi et al. 2024), as well as high-z AGN (e.g., Conselice et al. 2023; Yang et al. 2023; Burke et al. 2024; Mezcua et al. 2023, 2024). CIGALE uses a library of models to fit the SED of galaxies, where the best fit is found based on the reduced χ2 minimization among all the possible combinations of the SED models. The library of models is created under the assumption of a delayed star formation history (SFH) with an optional exponential burst (Ciesla et al. 2015), and the Bruzual & Charlot (2003) single stellar population (SSP) models adopting a Chabrier (2003) initial mass function (IMF). We assume solar metallicity and use Fritz et al. (2006) models to account for possible AGN contribution. The grid of input parameters used to generate the model library follows the configuration adopted in the DESI EDR VAC (Siudek et al. 2024), and is summarized in Table A.1. The generated models cover a wide range of objects, including galaxies without AGN contribution, as well as BL- and NL-AGN. This provides flexibility and allows us to build the catalog of physical properties for both AGN and non-AGN host galaxies. The SEDs of observed galaxies are created from the ground-based optical and near-infrared (NIR) photometry (i.e., grz photometry, which we refer to as optical) complemented by observations from MIR bands at 3.4, 4.6, 12 and 22 μm provided by the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE; Wright et al. 2010), a mission extension NEOWISE-Reactivation forced-photometry (Mainzer et al. 2014).

It is important to note that the precise AGN classification of individual sources–especially those with low AGN fractions–as well as the stellar masses and SFRs may depend on the model assumptions, and the incorporation of the WISE photometry (see Siudek et al. 2024 for a discussion). Based on the representative sample of ∼50 000 galaxies including passive, star-forming, and AGN galaxies, Siudek et al. (2024) find that without WISE photometry the AGN fraction is overestimated (AGNFRAC ≥0.1) for 68% of star-forming galaxies selected based on the [NII]-BPT emission line diagnostic diagram (see details in Sect. 3.1). Requiring a high S/N in the WISE observations (forced by FLAGINFRARED = 4) reduces this to 19%. This suggests that the MIR information is crucial to properly identify AGN via SED fitting. Siudek et al. (2024) also show that the overestimation of the AGNFRAC for the star-forming galaxies without WISE information has a negligible effect on their stellar mass or SFR estimates. We further discuss the dependence of the AGN identification on the model choice in Appendix C.

3. Sample selection based on the AGN diagnostics

In this study, we relied on a sample of 510 938 DESI EDR galaxies at z ≤ 0.5 from the VAC of physical properties4. We removed sources with poor photometric quality, defined as those with LOGM = 0, and sources with poor SED fits, defined as those with CHI2 > 17 (see Siudek et al. 2024). These criteria, along with the redshift limit (Z ≤ 0.5), define our parent sample. No additional cuts were applied at this stage; further selection criteria (e.g., S/N for emission-line quality or WISE-based selections) are introduced in the relevant sections.

To validate the performance of the SED-based AGN identification in recovering true AGN populations, we used a set of classical AGN diagnostics as reference. These include emission-line diagnostics (BPT-AGN), MIR colors (WISE-AGN), and high-energy diagnostics such as X-ray and radio emission. These methods were applied to galaxies at z ≤ 0.5, where line measurements and MIR photometry are most reliable. While the MIR color-based AGN selection draws from a subset of the photometric data available to full SED fitting, it remains a valuable cross-check. Its inclusion in this analysis serves primarily as a benchmark, given its common use and well-calibrated thresholds (e.g., Stern et al. 2012; Assef et al. 2013). We did not position it on equal footing with spectroscopy-based diagnostics or full SED fitting, as the latter incorporate broader wavelength coverage and physical modeling. Nonetheless, MIR color selection remains relevant for assessing completeness and consistency in AGN selection across surveys. To construct the BPT diagrams and BL-AGN sample, we used the emission line measurements from the DESI EDR FastSpecFit Spectral Synthesis and Emission-Line catalog (FastSpecFit version 3.2 Fuji production5; Moustakas et al. 2023; Moustakas et al. in prep.). FastSpecFit is a stellar continuum and emission-line fitting code optimized to model jointly DESI optical spectra and broadband photometry using physically motivated stellar continuum and emission-line templates6. The selection of the AGN sample is summarized in Sect. 3.5.

3.1. BPT diagram

The BPT diagrams (Baldwin et al. 1981) are widely used diagnostics relying on the strength of Balmer lines to forbidden nebular transitions to differentiate between star-forming galaxies and AGN. In this work, we used three diagrams based on the ratios of [NII]λ6583/Hα versus [OIII]λ5007/Hβ ([NII]-BPT), [SII]λ6717,6731/Hα versus [OIII]λ5007/Hβ ([SII]–BPT), and [OI]λ6583/Hα versus [OIII]λ6300/Hβ ([OI]-BPT) similarly as Mezcua & Domínguez Sánchez (2024). The [NII]-BPT diagram is sensitive to metallicity, making AGN identification in metal-poor galaxies difficult (e.g., Groves et al. 2006; Cann et al. 2019). The [SII]-BPT offers better separation at intermediate metallicities but struggles with composite galaxies. The [OI]-BPT is more robust across metallicities but relies on a weak line that is often hard to detect in faint or low-metallicity galaxies (Polimera et al. 2022). Recently, Ji & Yan 2020 proposed a simple reprojection of the [NII]-, [SII]-, and [OI]-BPTs that shows the potential to remove the ambiguity for the true composite objects. We leave the examination of this approach for future work.

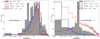

The [NII]-, [SII]-, and [OI]-BPTs for the DESI galaxies are shown in Fig. 1. We used the narrow components of the Balmer lines and applied a flux S/N ≥ 3 to all the emission lines in each diagram, except for [OI]λ6300, where a flux S/N ≥ 1 was adopted. The [OI]λ6300 line is weaker, and imposing a higher S/N threshold could exclude valid candidates (Cid Fernandes et al. 2010). The S/N cuts were applied separately for each diagram, meaning that the galaxies included in each BPT diagram could differ.

|

Fig. 1. Emission line diagnostic diagrams for DESI galaxies: N[II]-BPT (left), [SII]-BPT (middle), and [OI]-BPT (right). The demarcation lines separate star-forming galaxies, composites, and AGNs (for simplicity, we refer to Seyfert 2 galaxies as AGNs). |

We also used the WHAN diagram introduced by Cid Fernandes et al. (2010) that considers equivalent width (EW) of Hα (EW(Hα)) versus [NII]λ6583/Hα line ratios. The WHAN diagram differentiates AGN (with EW(Hα) ≥ 3 and log [NII]/Hα > −0.4) from galaxies with hot old (post-AGB) stars that can mimic Low-ionization nuclear emission-line region (LINERs). To ensure reliable measurements, we required a flux S/N ≥ 3 for all relevant lines (Hα and [NII]λ6583), as well as for EW(Hα). Consequently, the WHAN sample is not necessarily the same as the one used for the BPT diagrams, as the S/N cuts were applied independently.

3.2. BL-AGN selection

We identified BL-AGN at z ≤ 0.5 based on the presence of a broad Hα component. Following the criteria outlined in Pucha et al. (2025), we required S/N ≥ 3 for the total Hα flux (S/NHALPHA_FLUX), the broad Hα component (S/NHALPHA_BROAD), and the amplitude-over-noise (AoN) of the broad component (AoNHALPHA_BROAD).

3.3. WISE selection

To select MIR-AGN, we relied on the WISE color-color diagram W2 − W3 versus W1 − W2 proposed by Hviding et al. (2022). We restricted the sample to galaxies with S/N ≥ 3 in all WISE bands used in the diagram, and to z ≤ 0.5. We note that the forced WISE photometry can suffer from confusion and other systematic errors, which can impact the quality of the fitting and the resulting inference as well as the WISE S/N cuts. In addition, Legacy Surveys WISE photometry is quite shallow, particularly in W3 and W4, and for emission-line and other higher-redshift galaxies, which impacts the ability to identify AGNs from broadband SED modeling. The selection criteria proposed by Hviding et al. (2022) are more sensitive to low luminosity and heavily obscured AGN than the traditional cuts given by Jarrett et al. (2011) or Stern et al. (2012). However, WISE-AGN samples may be contaminated by star-forming galaxies diluting the WISE color-selected AGNs (Hainline et al. 2016).

3.4. X-ray and radio counterparts

We searched for X-ray counterparts within 5 arcsec of the optical position of each source as given by the DESI Legacy Imaging Surveys, making use of the Chandra source catalog (CSC DR2; Evans et al. 2010, 2024), the XMM-Newton Serendipitous source catalog (4XMM-DR13; Webb et al. 2020), and the all-sky survey catalog from the extended ROentgen Survey with an Imaging Telescope Array (eROSITA) on the Spectrum-Roentgen-Gamma (SRG) mission (eRASS1; Merloni et al. 2024). To identify the radio counterparts within 5 arcsec from the sources, we relied on the second data release of the LOFAR Two-metre Sky Survey (LoTSS DR2; Shimwell et al. 2022), the Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-cm (FIRST) Survey final catalog (Helfand et al. 2015), and the 1.4 GHz National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO) Very Large Array (VLA) Sky Survey (NVSS; Condon et al. 1998).

3.5. AGN sample

We applied the optical and MIR selection criteria described above to classify 510 939 DESI EDR galaxies into four types. These four classes are used as a reference to estimate the optimal threshold on AGNFRAC for identifying AGNs based on the SED fitting:

-

BPT-AGN: defined as AGNs or composites in the [NII]-BPT, AGNs on the WHAN diagram, and AGNs on the [SII]- or [OI]-BPT. Number of selected sources: 6019.

-

BPT-SF: defined as star-forming on the [NII]-, [SII]-, and [OI]-BPTs diagrams. Number of selected sources: 122 731.

-

BL-AGN: defined as sources with a broad Hα emission line. Number of selected sources: 4065.

-

WISE-AGN: defined as AGNs based on the WISE color diagram. Number of selected sources: 9253.

Each class includes galaxies at z ≤ 0.5, spanning a wide range of stellar masses. As shown in Fig. 2, the BPT-SF population predominantly consists of lower-mass, lower star-formation galaxies at lower redshifts. Additionally, since SFRs were derived from CIGALE using AGN-inclusive templates, even BPT-SF galaxies may show slightly suppressed SFRs if the fit assigns any AGN contribution – this is especially relevant in ambiguous or composite systems. We explore whether the χ2 distribution varies across different AGN and star-forming galaxy classifications (bottom right panel in Fig. 2). Contrary to some earlier works (e.g., Berta et al. 2013), where elevated χ2 values – especially in stellar or star-forming-only fits – could signal the presence of a hidden AGN (e.g., visible in the NIR excess), we find that the distributions of reduced χ2 are remarkably similar for BPT-AGN, WISE-AGN, BL-AGN, and BPT-SF galaxies. This is likely due to the inclusion of AGN templates in the CIGALE fits, which improves the overall model match even in AGN-dominated sources. This suggests that χ2 is not a discriminant for AGN identification in our case, provided that proper AGN templates are used during the fitting process. Figure 3 and Table 1 highlight the diversity and overlap between AGN identified through different selection techniques: BPT-AGN, BL-AGN, and WISE-AGN. The significant areas of non-overlap (e.g., 66.8% of WISE-AGN are identified only by WISE colors) underscore that each method may be sensitive to different types of AGN and highlight the need for a multiwavelength approach to identify the complete AGN sample, as already investigated by e.g., Cann et al. (2019) and Hviding et al. (2022).

|

Fig. 2. Distribution of z (top left panel), stellar mass (top right panel), SFR (bottom left panel), and χ2 (bottom right panel) for the AGN and star-forming samples. |

|

Fig. 3. Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between the AGNs selected using different methods: BPT-AGN (violet circle), BL-AGN (green circle), and WISE-AGN (yellow circle). The areas of overlap between circles indicate the AGNs identified by multiple methods, highlighting the diversity and overlap in AGN classification across different diagnostic techniques. |

4. Results and discussion

In this section, we validate the AGN fraction (AGNFRAC) estimated via SED fitting of optical (grz) and MIR (W14) observations as a proxy for identifying AGNs compared to standard techniques. As a large fraction of AGNs is not detected in optical surveys due to either distance or dust obscuration (e.g., Truebenbach & Darling 2017), we validate how crucial it is to include the MIR photometry in SED fits to recreate the AGN contribution in galaxies. We also identify AGN candidates selected by the SED method that do not appear on traditional AGN diagrams.

4.1. SED fitting: AGN fraction

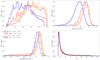

Usually, SED-based AGN selection is based on a fixed threshold on the AGN fraction derived from SED fitting (Thorne et al. 2022; Best et al. 2023; Bichang’a et al. 2024; Das et al. 2024). The AGN fraction is defined here as the fraction of the IR emission coming from the AGN to the total IR emission. We relied on the AGN and star-forming galaxy sample selected based on traditional techniques (see Sect. 3.5) to find the best threshold for AGN selection. Figure 4 shows the distribution of AGNFRAC for galaxies with different infrared coverages. We split the sample based on the FLAGINFRARED value, which indicates the number of WISE bands with high S/N (S/N ≥ 3): a value of 4 means detections in all four bands, while lower values correspond to fewer reliable measurements. Although AGNFRAC uncertainties are computed by CIGALE, they are not included in the DESI EDR VAC and in this analysis because, in cases with faint AGN emission or limited infrared data, the error estimates can become poorly constrained and unreliable for robust statistical use. This limitation is inherent to SED fitting in such regimes and does not affect the broader AGN selection performance (see also Ciesla et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2020, and Mountrichas et al. 2021b). In the left panel (galaxies observed in at most two WISE bands with S/N ≥ 3, i.e., with FLAGINFRARED ≤ 2), AGNs and star-forming galaxies show nearly indistinguishable AGNFRAC distributions (typical values around 0.3), indicating unreliable AGN fraction estimates when only one or two WISE bands are available. In contrast, the right panel (galaxies observed in all four WISE bands with S/N ≥ 3, i.e., with FLAGINFRARED = 4) reveals clear separation: star-forming galaxies show low AGNFRAC values (median = 0.02), while AGN classes (BPT-AGN, BL-AGN, WISE-AGN) have broader distributions with higher medians (0.19, 0.12, and 0.25, respectively). Notably, BPT-AGN exhibit a bimodal distribution peaking at 0 and 0.1.

|

Fig. 4. Distribution of the AGN fraction, defined as the fraction of the IR emission originating from the AGN relative to the total IR emission (AGNFRAC), for BPT-selected star-forming galaxies (BPT-SF), BPT-selected AGNs, WISE-selected AGNs, and BL-AGNs observed in at most two WISE bands with S/N ≥ 3 (FLAGINFRARED ≤ 2; left plot) or at all four WISE bands (FLAGINFRARED = 4; right plot). The median AGNFRAC values are reported in the legend. |

To further evaluate the discriminative power of AGNFRAC, we performed a classification analysis using receiver operating characteristic (ROC; Bradley 1997) curves across our samples. The performance metrics and threshold analysis (see Appendix D) suggest that AGNFRAC is an effective AGN indicator only when applied to sources with reliable infrared measurements.

Taking into account the strong correlation between AGNFRAC and the availability of WISE photometry with S/N ≥ 3 (see also Sect. 4.2), we recommend applying a selection criterion of AGNFRAC ≥ 0.1 combined with FLAGINFRARED = 4 to define AGN based on SED fitting (SED-AGN). This threshold is motivated both by the observed peak in AGNFRAC distributions for spectroscopically confirmed AGN classes (see Fig. 4) and by its optimal diagnostic performance in the ROC analysis (see Appendix D). For more inclusive samples, the infrared quality condition can be relaxed to FLAGINFRARED ≥ 3, which preserves the general distribution shape and yields similar median AGNFRAC values.

4.2. Importance of the MIR photometry

As shown in the previous section, the distribution of AGNFRAC is sensitive to the availability of WISE photometry. We further verify the dependence of the BPT classification on the availability of WISE photometry. Figure 5 shows the [NII]-BPT diagram for galaxies observed in all four WISE bands with S/N ≥ 3 (i.e., FLAGINFRARED = 4; right panel) and galaxies with at most two WISE observations with S/N ≥ 3 (i.e., FLAGINFRARED ≤ 2; left panel). The distribution of AGNFRAC is almost uniform on the BPT diagram for galaxies without high S/N WISE photometry. In contrast, for galaxies with FLAGINFRARED = 4, the AGNFRAC gradually changes from ≲0.1 in the star-forming galaxies locus to ≳0.4 in the region attributed to AGN.

|

Fig. 5. BPT diagram for DESI galaxies observed in at most two MIR bands with S/N ≥ 3 (i.e., FLAGINFRARED ≤ 2; left panel) and with all four WISE bands with S/N ≥ 3 (i.e., FLAGINFRARED = 4; right panel). The demarcation lines separating star-forming galaxies, composites, AGNs, and LINERs as proposed by Kewley et al. (2001), Kauffmann et al. (2003), and Schawinski et al. (2007) are marked with dashed, solid, and dash-dotted lines, respectively. The plots are color-coded by the AGN fraction (AGNFRAC is defined as the fraction of the IR originating from the AGN relative to the total IR emission). The AGN fraction increases toward the BPT region associated with AGNs and LINERs when all four WISE bands with S/N ≥ 3 are included in the SED fits. A lack of S/N ≥ 3 in all four MIR bands may result in an artificial overestimation of the AGN fraction (AGNFRAC ≥0.1) for a majority (62%) of star-forming galaxies. |

Using the AGN fraction derived with CIGALE as the criterion to select AGN (AGNFRAC ≥ 0.1), we recovered 74% of the BPT-selected AGNs (69% if limiting to the sample with FLAGINFRARED = 4). However, at the same time, 62% of star-forming galaxies are also identified as AGN (i.e., fulfilling the criterion AGNFRAC ≥ 0.1). The percentage of misclassified star-forming galaxies drops to 15% for a sample with FLAGINFRARED = 4. We note that Siudek et al. (2024) show that the overestimation of the AGN fraction for misclassified star-forming galaxies (with AGNFRAC ≥ 0.1) does not affect the estimates of the stellar masses and SFRs (see Sect. 2.2).

Figure 6 shows the WISE diagram as a function of the AGNFRAC depending on the availability of the WISE photometry. There is no visual difference in the dependence on the AGNFRAC whether the sample is limited to S/N ≥ 3 in W1-3; i.e., FLAGINFRARED = 3 or all WISE bands (W1-4; i.e., FLAGINFRARED = 4), but the sample size differs significantly. The sample selected with FLAGINFRARED ≥ 3 includes 9 253 sources, while restricting to FLAGINFRARED = 4 results in 4 974 galaxies. Without any restriction on the FLAGINFRARED, the WISE-AGN are recovered well with SED selection (79% of WISE-AGN are identified as SED-AGN). At the same time, 40% of non-AGN are identified as SED-AGN. Only when applying a stricter cut on WISE photometry (FLAGINFRARED = 4) does the identification of 86% of WISE-AGN and a reduction in the misclassified AGN to 33% occur.

|

Fig. 6. WISE diagram as a function of the AGN fraction for DESI galaxies observed with S/N ≥ 3 at W1 − 3 (left panel) or at all WISE bands (i.e., FLAGINFRARED = 4; right panel). The region of AGNs is marked by a dotted red line and follows the criterion proposed by Hviding et al. (2022). The WISE-selected AGNs are characterized by a higher AGN fraction than non-AGN galaxies except for the SED-MIR-AGN candidates, which are characterized by a high AGN fraction (AGNFRAC ≳ 0.5 at the right panel). We note that 96% of these SED-MIR-AGNs missed by the WISE diagram are identified as AGNs by the TBT diagram. |

We find a similar correlation between AGNFRAC and WISE colors as found for the BPT selection: the region attributed to AGNs is characterized by a high AGN fraction (with a median AGNFRAC = 0.25). Outside the AGN selection region, the AGN fraction is low (AGNFRAC ≲ 0.07). However, there are two regions attributed to higher AGN fraction (AGNFRAC ∼ 0.5) on the right-low end and left-upper of the AGN envelope. While the upper-left region is sparsely populated and can be neglected, the tail in W2-W3 (W2 − W3 ≲ 2.5) across 0.5 ≲ W1 − W2 ≲ 0 color gathers 2017 galaxies (i.e., half of the WISE-AGN sample; SED-MIR-AGN candidates hereafter).

The SED-MIR-AGN candidates are in the majority (91%) characterized by high AGN fraction (AGNFRAC ≳ 0.5)7. They are massive passive galaxies (with median log(Mstar/M⊙) ∼ 11 and median log(SFR/M⊙ yr−1) ∼ −6). SED-MIR-AGN candidates show tentative8 signatures of [NeIII]λ3869 emission (with median full width at half maximum similar to the one found for AGN, i.e., FWHM ∼ 320 km s−1, while for non-AGN FWHM is ∼ 230 km s−1). The [NeIII]λ3869 emission together with [OII]λλ3727, 3729 emission line and g-z rest-frame color forms another AGN diagnostic diagram (TBT diagram; Trouille et al. 2011). Trouille et al. (2011) showed that the TBT diagram is efficient in recreating [NII]-BPT selection (98.7% of BPT-AGNs are identified as TBT-AGNs and 97% of the BPT-SF as TBT-SF) at the same time outperforming the BPT in identifying X-ray selected AGN (TBT identifies 97% of the X-ray AGN as TBT-AGNs, while BPT only 80%). Almost all SED-MIR-AGN candidates (94%) are identified as AGNs according to the TBT diagram; however, we cannot be confident in their AGN nature, as only 65 have [NeIII]λ3869 detected with S/N ≥ 3. The weak and noisy [NeIII]λ3869 measurement may bias this conclusion.

4.3. SED-AGN sample

Table 2 shows that the SED-AGN sample, defined by galaxies with AGNFRAC ≥ 0.1 and FLAGINFRARED = 4 at z ≤ 0.5, identifies a significant number of AGNs (≳70%) selected using traditional methods. This overlap suggests that the SED-fitting approach is capable of capturing a broad range of AGN types. As detailed in Table 2, the SED-based classification successfully identifies around 70% of BL-AGN and BPT-AGN and over 85% of WISE-AGN. This high level of correspondence demonstrates the robustness of the SED method in capturing classical AGN types. However, about 15% of star-forming galaxies (BPT-SF) are also classified as AGN by the SED method, indicating some level of contamination from non-AGN sources.A particularly notable result is that over half of the SED-AGN sample (∼52%) is not identified by any of the main AGN selection methods (BL-AGN, BPT-AGN, WISE-AGN, or BPT-SF). This raises an important question: is the SED-based method producing a high rate of false positives, or is it effectively uncovering a population of AGN that are missed by traditional diagnostics? To better understand the nature of the SED-AGN sample, we expanded our analysis beyond the standard AGN selection techniques. Specifically, we incorporate additional AGN classifications derived from all three BPTs, X-ray, and radio AGN diagnostics. This broader approach allows for a more comprehensive assessment of the AGN content within the SED-selected population.

Efficiency of the SED-AGN classification relative to the standard AGN identification methods, where N gives the number of AGNs identified by a given method among galaxies with FLAGINFRARED = 4 at z ≤ 0.5.

When incorporating these additional AGN identification methods, the fraction of galaxies classified solely by the SED criteria (SED-AGN-only) decreases significantly–from 51.78% to 16.14% (see Table 3), highlighting both the complementary value and the limitations of the SED-based method. The SED-based approach appears to at least partially recover AGN populations that are overlooked by traditional diagnostics, emphasizing the value of SED fitting in building a more complete and inclusive AGN census. However, at the same time, a non-negligible fraction of the SED-AGN sample (∼15%) overlaps with star-forming galaxies (BPT-SF), suggesting some level of contamination. Moreover, the AGN nature of sources classified solely as SED-AGN-only remains unconfirmed (see discussion below), challenging the use of SED fitting for constructing clean and pure AGN samples.

The SED-based technique identifies roughly 50% of LINERs as selected by the BPT diagrams. The interpretation of LINERs remains actively debated in the literature, with studies supporting both AGN (e.g., Heckman 1980; Kewley et al. 2006) and stellar photoionization scenarios (e.g., Stasińska et al. 2006; Sarzi et al. 2010). The overlap with LINERs suggests that the SED-AGN method is sensitive to a diverse AGN population, including those in different evolutionary stages or in obscured environments. The SED-based method maintains a relatively low level of contamination except in the WHAN diagram. The SED-AGN identifies not only 40% of WHAN-AGN but also 67% of retired galaxies. Interestingly, the majority (96%) of these retired SED-AGN are actually “liny” (i.e., showing the presence of the emission lines; 0.5 ≤ (EW(Hα) < 3 Å). The WHAN diagram is known to struggle with distinguishing low-luminosity AGN from “liny” retired galaxies, where line emission could originate from past AGN activity or low-level star formation (Cid Fernandes et al. 2010, 2011; Herpich et al. 2018). This raises the possibility that the SED-AGN method may identify galaxies transitioning from AGN activity to a more passive state, causing them to appear as retired on the WHAN diagram. Supporting this interpretation, Herpich et al. (2018) suggested that “liny” retired galaxies might have undergone recent star formation, and their emission line gas could originate from the AGN activity. Similarly, Agostino et al. (2023) show that nearly one-third of X-ray AGN fall in the WHAN “retired” locus. In our sample, out of 2386 SED-AGN classified as retired in WHAN, 515 (22%) are independently confirmed as AGN via other diagnostics, further questioning their classification as fully passive systems.

The X-ray data (see Sect. 3.4) reveal 882 sources with X-ray emission. Using the star formation rates derived from CIGALE SED fitting and the relation from Lehmer et al. (2010), we estimate the expected 2–10 keV luminosity from star formation and find that 793 galaxies exceed this by more than 3σ, confirming AGN-like X-ray emission (see also Mezcua et al. 2018). The SED-based method identifies ∼50% of these X-ray AGN, even though X-ray data are not used in the fitting, demonstrating good sensitivity to AGN across different regimes. To understand why the other 50% are missed, we examine their classification using other methods. Most are also missed by traditional BPT, and WISE diagnostics, with nearly 40% falling into the WHAN-AGN region. This suggests that the missed X-ray AGN are generally low-luminosity or obscured, escaping both SED and classical diagnostics, and reinforces the known difficulty of identifying such AGN without deep X-ray data. This is consistent with previous studies such as Trouille et al. (2011) and Juneau et al. (2011, 2013), which showed that only ∼20–30% of X-ray AGN fall in the AGN region of the BPT diagram, with many appearing as star-forming or composite systems instead. These studies concluded that emission-line diagnostics become increasingly incomplete for identifying obscured or radiatively inefficient AGN. Our results are in agreement with these findings, and show that SED fitting adds significant value by recovering ∼50% of X-ray AGN, highlighting its effectiveness in such regimes.

Of 13 450 galaxies with radio detections (see Sect. 3.4), 5326 exhibit radio luminosities either above 5 × 1023 W/Hz or more than 3σ above what is expected from star formation (e.g., Mezcua et al. 2019), classifying them as radio AGN. The SED fitting recovers 40% of these sources. Similar to the X-ray case, the radio AGN missed by SED tend to be weakly active or obscured, with most showing no overlap with BPT, or WISE diagnostics, and ∼45% falling within the WHAN-AGN region. This again highlights the complementary but incomplete nature of the SED-based classification and reinforces the need for multiwavelength data to uncover the full AGN population. Moreover, the SED fitting depends on model assumptions, which affect the AGN classification (see Table C.1 for details).

Figure 7 shows the stacked spectra of BPT-AGN, WISE-AGN, SED-AGN, and BPT-SF galaxies. The spectra were stacked using mean normalization, preserving the relative fluxes of the emission lines, which is essential for a reliable comparison of spectral features across different samples. The SED-AGN stack shows similarity to the BPT-AGN and WISE-AGN stacks, particularly evident in the characteristic AGN emission line ratios, such as [NII]/Hα. Unlike the BPT-SF sample, where the [NeV]λ3427 emission is absent, the presence and relative strength of [NeV]λ3427 in SED-AGN align more closely with the AGN-dominated spectra. High-ionization lines, such as [NeV]λ3427, require energies well above the limit of stellar emission (55 eV; e.g., Leitherer et al. 1999; Izotov et al. 2004) and can be an efficient tracer of the AGN (e.g Gilli et al. 2010; Negus et al. 2023; Barchiesi et al. 2024).

|

Fig. 7. Stacked spectra of BPT-AGN, WISE-AGN, SED-AGN, and BPT-SF. The stacked spectrum of SED-AGN galaxies highlights the characteristic AGN emission line ratios, suggesting their AGN nature. The stacked spectrum is created using the mean for normalization, preserving the relative fluxes of the emission lines. |

4.4. SED-AGN-only: Properties of the host galaxies

Despite the effectiveness of the SED-based technique, 4054 out of 25 123 SED-AGN galaxies (16.14%, see Table 3) are classified as SED-AGN-only, meaning they are not confirmed by any other AGN selection method. To further explore the nature of these SED-AGN-only galaxies, we analyze their properties in comparison to properties of the BPT-AGN, WISE-AGN, SED-AGN, and BPT-SF galaxies9 as summarized in Table 4. These SED-AGN-only galaxies tend to be more massive, with median stellar masses comparable to those of BPT-AGN and WISE-AGN hosts (log(Mstar/M⊙) ∼ 10.75). However, they exhibit significantly lower star formation rates (log(SFR/M⊙yr−1) ∼ −2) than BPT-AGN and WISE-AGN, suggesting that they are generally passive galaxies.

Comparison of the main properties: redshift, stellar masses (LOGM), and SFRs (LOGSFR) from the VAC of physical properties, and D4000 from FastSpecFit.

To confirm the passive nature of SED-AGN-only hosts, we also check the 4000 Å break (D4000), an indicator of the age of the stellar population: a high D4000 value (D4000 > 1.5) indicates older stars and high metallicity, while a lower value (D4000 ≤ 1.5) suggests younger, star-forming populations (e.g., Kauffmann et al. 2003; Siudek et al. 2017, 2018a). The high D4000 values of the SED-AGN-only (D4000 = 1.76) indicate that old stars dominate the light from these galaxies. Moreover, we find that the majority (78%) of the AGN-SED-only show red colors on the U-V versus V-J diagram (Whitaker et al. 2012; Siudek et al. 2024), consistent with their passive nature. This contrasts sharply with other classes, where the fraction of red galaxies is much lower, ranging from 0% in star-forming galaxies to 13% in BPT-AGN. Additionally, the optical part of the SEDs of SED-AGN-only galaxies is dominated by old stellar populations, while AGN contribution is seen in the MIR (see Appendix B). This analysis suggests that SED-AGN-only galaxies may represent a population of galaxies transitioning away from active star formation, possibly hosting weak or fading AGN activity that other methods fail to detect.

We also verify whether there are signatures of non-AGN nature among SED-AGN-only. Only 15 of the SED-AGN (< 1%) are characterized by line ratios characteristic of shock excitation, such as [SII](λ6717 + λ6731)/Hα> 0.4 or [OI]/Hα > 0.1, which are traditionally associated with supernova remnants or other shock-heated regions rather than photoionization by an AGN (e.g., Dodorico et al. 1978; Rich et al. 2010; Comerford et al. 2022). This suggests that contamination from non-AGN processes in the SED-AGN-only sample isminimal.

5. Summary

We identified AGNs based on the AGN fraction (AGNFRAC ≥ 0.1) derived from SED fitting with CIGALE applied to DESI EDR galaxies at z ≤ 0.5. As discussed in Sect. 1, traditional AGN identification diagnostics, such as the BPT diagram, are limited by luminosity biases, often leading to incomplete samples. In contrast, the SED-based approach, leveraging a multiwavelength strategy, promises a morecomprehensive identification of AGNs. Our key findings are summarized as follows:

-

Importance of WISE photometry: MIR photometry is essential for robust AGN identification via AGNFRAC. When high S/N (S/N ≥ 3) WISE photometry is limited (i.e., FLAGINFRARED ≤ 2), 62% of BPT-selected star-forming galaxies are incorrectly classified as AGNs. Including all four WISE bands with S/N ≥ 3 (FLAGINFRARED = 4) reduces this contamination to 15%. Meanwhile, 70% of BPT-AGN are consistently recovered, irrespective of the WISE photometry S/N (see Sect. 4.2).

-

MIR-AGN candidates beyond WISE diagram: The SED fitting method identifies a distinct subset of strong AGN candidates (SED-MIR-AGN) that fall outside the canonical AGN region on the WISE diagram. These sources are confirmed as AGN in 98% of cases via the TBT diagram, although weak and noisy [NeIII]λ3869 emission limits definitive confirmation (see Sect. 4.2).

-

Comparison with standard AGN selection methods: Our SED-based AGN classification shows substantial agreement with traditional techniques, recovering approximately 70% of both BL-AGNs and BPT-AGNs, and over 85% of WISE-selected AGNs. However, the method has a 15% contamination rate from star-forming galaxies.

-

SED fitting as a unifying AGN diagnostic: The SED approach uncovers a population of AGNs (SED-AGN-only) missed by standard diagnostics. Relying solely on BPT-AGN, WISE-AGN, and BPT-SF selections fails to identify ∼52% of SED-AGNs (see Table 2). Incorporating multiple selection methods reduces this fraction to ∼16% (see Table 3). While promising, the SED-AGN-only population includes uncertain cases (e.g., LINERs, “liny” retired galaxies) and may still be affected by a ∼15% contamination from star-forming galaxies.

-

Dependence on model assumptions: The efficiency and purity of SED-based AGN selection are moderately sensitive to modeling choices (see Table C.1 and Fig. D.1). Changes to dust attenuation laws and AGN templates can alter the balance between completeness and contamination, while variations in IMF, SFH, and SSP models have smaller effects. We note that allowing metallicity to vary as a free parameter achieves similar or even slightly better performance, further reducing contamination from star-forming galaxies and marginally improving AGN selection efficiency. The use of MIR data is crucial–removing WISE W3 and W4 bands leads to severe contamination by star-forming galaxies.

This work demonstrates the importance of multiwavelength data fusion for robust AGN identification, with direct implications for upcoming large-scale surveys. The Euclid mission will provide deep NIR photometry across 14 000 deg2 (Euclid Collaboration: Mellier et al. 2025); LSST will deliver unprecedented optical depth and time-domain coverage (Ivezić et al. 2019); and the Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and ices Explorer (SPHEReX) will perform an all-sky spectroscopic survey with near-immediate public data release (Doré et al. 2014; Crill et al. 2020). However, mismatched depths and sky coverage among these facilities present challenges for optimal data fusion (e.g., Melchior et al. 2021; Huertas-Company & Lanusse 2023).

Our 70–80% recovery rate using DESI Legacy Surveys and WISE photometry demonstrates that systematic multiwavelength approaches can effectively overcome individual survey limitations. To further enhance AGN selection, machine-learning techniques are proving increasingly powerful. Semi-supervised clustering applied to medium-resolution spectroscopy can automatically separate narrow-line and broad-line AGN with high accuracy (Siudek et al. 2018a,b, 2022; Dubois et al. 2024). Autoencoder architectures successfully recover AGN candidates missed by traditional BPT diagnostics due to low-S/N line measurements (Alcolea et al., in preparation), while diffusion-based models identify AGNs from single-band morphological analyses of Euclid optical images (Euclid Collaboration: Stevens et al. 2025). Foundation models may further unify multiwavelength AGN detection, though their full potential remains to be explored (Euclid Collaboration: Siudek et al. 2025).

The multiwavelength approach, such as the systematic incorporation of SPHEReX spectroscopic data into LSST AGN selection pipelines, analogous to the DESI Legacy Surveys and WISE approach presented here, could reduce the 15% star-forming galaxy contamination observed in optical-only classifications. More broadly, a multimodal approach that combines morphological, spectral, and photometric data may be key to robust AGN identification in the era of next-generation surveys.

Data availability

The VAC of physical properties of DESI EDR galaxies is publicly available at https://data.desi.lbl.gov/doc/releases/edr/vac/cigale/. The presented analysis is conducted on v1.4 based on the redshift coming from the QSO afterburner pipeline relying on the QuasarNet and the broad Mg II finder pipelines. The data behind the figures are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15622223.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the anonymous referee for insightful comments. This work has been supported by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange (Bekker grant BPN/BEK/2021/1/00298/DEC/1) and the State Research Agency of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (grant PGC2018-100852-A-I00 and PID2021-126838NB-I00). M.M. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation through the project PID2021-124243NB-C22, and the program Unidad de Excelencia María de Maeztu CEX2020-001058-M. H.Z. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC; grant Nos. 12120101003 and 12373010) and National Key R&D Program of China (grant Nos. 2023YFA1607800, 2022YFA1602902) and Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Science (Grant Nos. XDB0550100). This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of High-Energy Physics, under Contract No. DE–AC02–05CH11231, and by the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility under the same contract. Additional support for DESI was provided by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), Division of Astronomical Sciences under Contract No. AST-0950945 to the NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory; the Science and Technology Facilities Council of the United Kingdom; the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; the Heising-Simons Foundation; the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA); the National Council of Humanities, Science and Technology of Mexico (CONAHCYT); the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of Spain (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033), and by the DESI Member Institutions: https://www.desi.lbl.gov/collaborating-institutions. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U. S. National Science Foundation, the U. S. Department of Energy, or any of the listed funding agencies. The authors are honored to be permitted to conduct scientific research on Iolkam Du’ag (Kitt Peak), a mountain with particular significance to the Tohono O’odham Nation. The DESI Legacy Imaging Surveys consist of three individual and complementary projects: the Dark Energy Camera Legacy Survey (DECaLS), the Beijing-Arizona Sky Survey (BASS), and the Mayall z-band Legacy Survey (MzLS). DECaLS, BASS and MzLS together include the data obtained, respectively, at the Blanco telescope, Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory, NSF’s NOIRLab; the Bok telescope, Steward Observatory, University of Arizona; and the Mayall telescope, Kitt Peak National Observatory, NOIRLab. NOIRLab is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA) under a cooperative agreement with the National Science Foundation. Pipeline processing and analyses of the data were supported by NOIRLab and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Legacy Surveys also uses data products from the Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (NEOWISE), a project of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Legacy Surveys was supported by: the Director, Office of Science, Office of High Energy Physics of the U.S. Department of Energy; the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, a DOE Office of Science User Facility; the U.S. National Science Foundation, Division of Astronomical Sciences; the National Astronomical Observatories of China, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation. LBNL is managed by the Regents of the University of California under contract to the U.S. Department of Energy. The complete acknowledgments can be found at https://www.legacysurvey.org/.

References

- Agostino, C. J., Salim, S., Boquien, M., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 526, 4455 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A., Anderson, S. F., Argudo-Fernández, M., et al. 2023, ApJS, 267, 44 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anand, A., Guy, J., Bailey, S., et al. 2024, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2405.19288] [Google Scholar]

- Assef, R. J., Stern, D., Kochanek, C. S., et al. 2013, ApJ, 772, 26 [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J. A., Phillips, M. M., & Terlevich, R. 1981, PASP, 93, 5 [Google Scholar]

- Barchiesi, L., Vignali, C., Pozzi, F., et al. 2024, A&A, 685, A141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, S., Sánchez-Sáez, P., Arévalo, P., et al. 2025, A&A, 694, A127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Berta, S., Lutz, D., Santini, P., et al. 2013, A&A, 551, A100 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Best, P. N., Kondapally, R., Williams, W. L., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 523, 1729 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bichang’a, B., Kaviraj, S., Lazar, I., et al. 2024, MNRAS, submitted [arXiv:2406.11962] [Google Scholar]

- Boquien, M., Burgarella, D., Roehlly, Y., et al. 2019, A&A, 622, A103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, A. P. 1997, Pattern Recog., 30, 1145 [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, W. N., & Alexander, D. M. 2015, A&ARv, 23, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Brodzeller, A., Dawson, K., Bailey, S., et al. 2023, AJ, 166, 66 [Google Scholar]

- Bruzual, G., & Charlot, S. 2003, MNRAS, 344, 1000 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, C. J., Liu, X., Shen, Y., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 516, 2736 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, C. J., Liu, Y., Ward, C. A., et al. 2024, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2402.06882] [Google Scholar]

- Burlon, D., Ajello, M., Greiner, J., et al. 2011, ApJ, 728, 58 [Google Scholar]

- Calzetti, D., Armus, L., Bohlin, R. C., et al. 2000, ApJ, 533, 682 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cann, J. M., Satyapal, S., Abel, N. P., et al. 2019, ApJ, 870, L2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrier, G. 2003, PASP, 115, 763 [Google Scholar]

- Charlot, S., & Fall, S. M. 2000, ApJ, 539, 718 [Google Scholar]

- Chaussidon, E., Yèche, C., Palanque-Delabrouille, N., et al. 2023, ApJ, 944, 107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cid Fernandes, R., Stasińska, G., Schlickmann, M. S., et al. 2010, MNRAS, 403, 1036 [Google Scholar]

- Cid Fernandes, R., Stasińska, G., Mateus, A., & Vale Asari, N. 2011, MNRAS, 413, 1687 [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla, L., Charmandaris, V., Georgakakis, A., et al. 2015, A&A, 576, A10 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla, L., Gómez-Guijarro, C., Buat, V., et al. 2023, A&A, 672, A191 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Comerford, J. M., Negus, J., Barrows, R. S., et al. 2022, ApJ, 927, 23 [Google Scholar]

- Condon, J. J., Cotton, W. D., Greisen, E. W., et al. 1998, AJ, 115, 1693 [Google Scholar]

- Conselice, C. J., Singh, M., Adams, N., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 525, 1353 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crill, B. P., Werner, M., Akeson, R., et al. 2020, SPIE Conf. Ser., 11443, 114430I [Google Scholar]

- Csizi, B., Tortorelli, L., Siudek, M., et al. 2024, A&A, 689, A37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dale, D. A., Helou, G., Magdis, G. E., et al. 2014, ApJ, 784, 83 [Google Scholar]

- Das, S., Smith, D. J. B., Haskell, P., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 531, 977 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DESI Collaboration (Aghamousa, A., et al.) 2016a, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:1611.00036] [Google Scholar]

- DESI Collaboration (Aghamousa, A., et al.) 2016b, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv: 1611.00037] [Google Scholar]

- DESI Collaboration (Abareshi, B., et al.) 2022, AJ, 164, 207 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DESI Collaboration (Adame, A. G., et al.) 2024a, AJ, 168, 58 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DESI Collaboration (Adame, A. G., et al.) 2024b, AJ, 167, 62 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DESI Collaboration (Adame, A. G., et al.) 2024c, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv: 2411.12022] [Google Scholar]

- DESI Collaboration (Abdul-Karim, M., et al.) 2025, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2503.14745] [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A., Schlegel, D. J., Lang, D., et al. 2019, AJ, 157, 168 [Google Scholar]

- Dodorico, S., Benvenuti, P., & Sabbadin, F. 1978, A&A, 63, 63 [Google Scholar]

- Doré, O., Bock, J., Ashby, M., et al. 2014, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:1412.4872] [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T., Aniano, G., Krause, O., et al. 2014, ApJ, 780, 172 [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, J., Siudek, M., Fraix-Burnet, D., & Moultaka, J. 2024, A&A, 687, A76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Euclid Collaboration (Mellier, Y., et al.) 2025, A&A, 697, A1 [Google Scholar]

- Euclid Collaboration (Siudek, M., et al.) 2025, A&A, in press, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554611 [Google Scholar]

- Euclid Collaboration (Stevens, G., et al.) 2025, A&A, submitted [arXiv:2503.15321] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, I. N., Primini, F. A., Glotfelty, K. J., et al. 2010, ApJS, 189, 37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, I. N., Evans, J. D., Martínez-Galarza, J. R., et al. 2024, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2407.10799] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, V. A., Alexander, D. M., Brodzeller, A., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 525, 5575 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, J., Franceschini, A., & Hatziminaoglou, E. 2006, MNRAS, 366, 767 [Google Scholar]

- Genzel, R., Eisenhauer, F., & Gillessen, S. 2010, Rev. Mod. Phys., 82, 3121 [Google Scholar]

- Ghez, A. M., Salim, S., Weinberg, N. N., et al. 2008, ApJ, 689, 1044 [Google Scholar]

- Gilli, R., Comastri, A., & Hasinger, G. 2007, A&A, 463, 79 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gilli, R., Vignali, C., Mignoli, M., et al. 2010, A&A, 519, A92 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Groves, B. A., Heckman, T. M., & Kauffmann, G. 2006, MNRAS, 371, 1559 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.-J., Zou, H., Fawcett, V. A., et al. 2024a, ApJS, 270, 26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W. J., Zou, H., Greenwell, C. L., et al. 2024b, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2408.00402] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, W.-J., Pan, Z., Siudek, M., et al. 2025, ApJ, 981, L8 [Google Scholar]

- Guy, J., Bailey, S., Kremin, A., et al. 2023, AJ, 165, 144 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, C., Wilson, M. J., Ruiz-Macias, O., et al. 2023, AJ, 165, 253 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hainline, K. N., Reines, A. E., Greene, J. E., & Stern, D. 2016, ApJ, 832, 119 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, C. M., & Ramos Almeida, C. 2024, Galaxies, 12, 17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, T. M. 1980, A&A, 87, 152 [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, T. M., & Best, P. N. 2014, ARA&A, 52, 589 [Google Scholar]

- Helfand, D. J., White, R. L., & Becker, R. H. 2015, ApJ, 801, 26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herpich, F., Stasińska, G., Mateus, A., Vale Asari, N., & Cid Fernandes, R. 2018, MNRAS, 481, 1774 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Huertas-Company, M., & Lanusse, F. 2023, PASA, 40, e001 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hviding, R. E., Hainline, K. N., Rieke, M., et al. 2022, AJ, 163, 224 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ivezić, Ž., Kahn, S. M., Tyson, J. A., et al. 2019, ApJ, 873, 111 [Google Scholar]

- Izotov, Y. I., Noeske, K. G., Guseva, N. G., et al. 2004, A&A, 415, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, T. H., Cohen, M., Masci, F., et al. 2011, ApJ, 735, 112 [Google Scholar]

- Ji, X., & Yan, R. 2020, MNRAS, 499, 5749 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Juneau, S., Dickinson, M., Alexander, D. M., & Salim, S. 2011, ApJ, 736, 104 [Google Scholar]

- Juneau, S., Dickinson, M., Bournaud, F., et al. 2013, ApJ, 764, 176 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffmann, G., Heckman, T. M., Tremonti, C., et al. 2003, MNRAS, 346, 1055 [Google Scholar]

- Kewley, L. J., Heisler, C. A., Dopita, M. A., & Lumsden, S. 2001, ApJS, 132, 37 [Google Scholar]

- Kewley, L. J., Groves, B., Kauffmann, G., & Heckman, T. 2006, MNRAS, 372, 961 [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, E., Smith, K. M., Dunkley, J., et al. 2011, ApJS, 192, 18 [Google Scholar]

- Kormendy, J., & Ho, L. C. 2013, ARA&A, 51, 511 [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, M., Storrie-Lombardi, L. J., Sajina, A., et al. 2004, ApJS, 154, 166 [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, M., Ridgway, S. E., Sajina, A., et al. 2015, ApJ, 802, 102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, D., Hogg, D. W., & Mykytyn, D. 2016, Astrophysics Source Code Library [record ascl:1604.008] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmer, B. D., Alexander, D. M., Bauer, F. E., et al. 2010, ApJ, 724, 559 [Google Scholar]

- Leitherer, C., Schaerer, D., Goldader, J. D., et al. 1999, ApJS, 123, 3 [Google Scholar]

- Levi, M., Bebek, C., Beers, T., et al. 2013, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:1308.0847] [Google Scholar]

- Mainzer, A., Bauer, J., Cutri, R. M., et al. 2014, ApJ, 792, 30 [Google Scholar]

- Maiolino, R., Cirasuolo, M., Afonso, J., et al. 2020, The Messenger, 180, 24 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Małek, K., Buat, V., Roehlly, Y., et al. 2018, A&A, 620, A50 [Google Scholar]

- Maraston, C. 2005, MNRAS, 362, 799 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A., Auger-Williams, M. W., Banerji, M., Maiolino, R., & Bowler, R. 2022, MNRAS, 515, 5617 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzolari, G., Gilli, R., Brusa, M., et al. 2024, A&A, 687, A120 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Meisner, A. M., Lang, D., Schlafly, E. F., & Schlegel, D. J. 2021, Res. Notes Am. Astron. Soc., 5, 168 [Google Scholar]

- Melchior, P., Joseph, R., Sanchez, J., MacCrann, N., & Gruen, D. 2021, Nat. Rev. Phys., 3, 712 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Merloni, A., Alexander, D. A., Banerji, M., et al. 2019, The Messenger, 175, 42 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Merloni, A., Lamer, G., Liu, T., et al. 2024, A&A, 682, A34 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mezcua, M., & Domínguez Sánchez, H. 2024, MNRAS, 528, 5252 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mezcua, M., Civano, F., Marchesi, S., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 478, 2576 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mezcua, M., Suh, H., & Civano, F. 2019, MNRAS, 488, 685 [Google Scholar]

- Mezcua, M., Siudek, M., Suh, H., et al. 2023, ApJ, 943, L5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mezcua, M., Pacucci, F., Suh, H., Siudek, M., & Natarajan, P. 2024, ApJ, 966, L30 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T. N., Doel, P., Gutierrez, G., et al. 2023, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2306.06310] [Google Scholar]

- Mountrichas, G., Buat, V., Georgantopoulos, I., et al. 2021a, A&A, 653, A70 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mountrichas, G., Buat, V., Yang, G., et al. 2021b, A&A, 646, A29 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, J., Scholte, D., Dey, B., & Khederlarian, A. 2023, Astrophysics Source Code Library [record ascl:2308.005] [Google Scholar]

- Negus, J., Comerford, J. M., Sánchez, F. M., et al. 2023, ApJ, 945, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oke, J. B., & Gunn, J. E. 1983, ApJ, 266, 713 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, C., & Salim, S. 2024, ApJ, 962, 59 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Padovani, P. 2016, A&ARv, 24, 13 [Google Scholar]

- Pai, A., Blanton, M. R., Moustakas, J., et al. 2024, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2407.05508] [Google Scholar]

- Polimera, M. S., Kannappan, S. J., Richardson, C. T., et al. 2022, ApJ, 931, 44 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Poppett, C., Tyas, L., Aguilar, J., et al. 2024, AJ, 168, 245 [Google Scholar]

- Prathap, J., Hopkins, A. M., Robotham, A. S. G., et al. 2024, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2402.11817] [Google Scholar]

- Pucha, R., Juneau, S., Dey, A., et al. 2025, ApJ, 982, 10 [Google Scholar]

- Raichoor, A., Moustakas, J., Newman, J. A., et al. 2023, AJ, 165, 126 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rich, J. A., Dopita, M. A., Kewley, L. J., & Rupke, D. S. N. 2010, ApJ, 721, 505 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Salim, S., Lee, J. C., Janowiecki, S., et al. 2016, ApJS, 227, 2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Salpeter, E. E. 1955, ApJ, 121, 161 [Google Scholar]

- Sarzi, M., Shields, J. C., Schawinski, K., et al. 2010, MNRAS, 402, 2187 [Google Scholar]

- Schawinski, K., Thomas, D., Sarzi, M., et al. 2007, MNRAS, 382, 1415 [Google Scholar]

- Schlafly, E. F., Kirkby, D., Schlegel, D. J., et al. 2023, AJ, 166, 259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shimwell, T. W., Hardcastle, M. J., Tasse, C., et al. 2022, A&A, 659, A1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Siudek, M., Małek, K., Scodeggio, M., et al. 2017, A&A, 597, A107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Siudek, M., Małek, K., Pollo, A., et al. 2018a, A&A, 617, A70 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Siudek, M., Małek, K., Pollo, A., et al. 2018b, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:1805.09905] [Google Scholar]

- Siudek, M., Lisiecki, K., Mezcua, M., et al. 2022, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2211.11792] [Google Scholar]

- Siudek, M., Pucha, R., Mezcua, M., et al. 2024, A&A, 691, A308 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Stalevski, M., Fritz, J., Baes, M., Nakos, T., & Popović, L. Č. 2012, MNRAS, 420, 2756 [Google Scholar]

- Stalevski, M., Ricci, C., Ueda, Y., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 458, 2288 [Google Scholar]

- Stasińska, G., Cid Fernandes, R., Mateus, A., Sodré, L., & Asari, N. V. 2006, MNRAS, 371, 972 [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D., Eisenhardt, P., Gorjian, V., et al. 2005, ApJ, 631, 163 [Google Scholar]

- Stern, D., Assef, R. J., Benford, D. J., et al. 2012, ApJ, 753, 30 [Google Scholar]

- Tadhunter, C. 2016, A&ARv, 24, 10 [Google Scholar]

- Thorne, J. E., Robotham, A. S. G., Davies, L. J. M., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 509, 4940 [Google Scholar]

- Trouille, L., Barger, A. J., & Tremonti, C. 2011, ApJ, 742, 46 [Google Scholar]

- Truebenbach, A. E., & Darling, J. 2017, MNRAS, 468, 196 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, N. A., Coriat, M., Traulsen, I., et al. 2020, A&A, 641, A136 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, K. E., van Dokkum, P. G., Brammer, G., & Franx, M. 2012, ApJ, 754, L29 [Google Scholar]

- Wright, E. L., Eisenhardt, P. R. M., Mainzer, A. K., et al. 2010, AJ, 140, 1868 [Google Scholar]

- Wylezalek, D., Zakamska, N. L., Greene, J. E., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 474, 1499 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G., Boquien, M., Buat, V., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 491, 740 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G., Caputi, K. I., Papovich, C., et al. 2023, ApJ, 950, L5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- York, D. G., Adelman, J., Anderson, J. E., Jr, et al. 2000, AJ, 120, 1579 [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, R., Dey, B., Newman, J. A., et al. 2023, AJ, 165, 58 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H., Zhou, X., Fan, X., et al. 2017, PASP, 129, 064101 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: SED fitting parameters

To ensure transparency and reproducibility, we provide in Table A.1 the full set of input parameters and grid values used in the SED fitting process with CIGALE. These parameters follow the configuration adopted in the DESI EDR VAC (Siudek et al. 2024). As CIGALE-based analyses are sensitive to the choice and priors of model parameters, we use a grid that balances physical coverage with computational feasibility.

Default grid of input parameters used in SED fitting with CIGALE.

Appendix B: The SEDs for representative examples

Figure B.1 shows the SEDs for representative examples from each category: a typical star-forming galaxy, a WISE/BPT-AGN, and a SED-AGN-only galaxy. The star-forming galaxy exhibits a strong stellar component, with the SED peaking in the optical and NIR regions. The dust emission, indicated by the infrared excess, reflects ongoing star formation. The AGN contribution is negligible, consistent with the expected characteristics of a purely star-forming galaxy. The WISE/BPT-AGN, in contrast, shows significant AGN activity, particularly in the MIR range. The SED reveals a combination of strong stellar emission and enhanced IR output due to AGN-heated dust. This suggests that while the galaxy is actively forming stars, the AGN is also contributing significantly to the overall energy output. The SED-AGN-only galaxy presents a distinct profile, with a relatively weak stellar component and a dominant AGN contribution in the MIR. The optical part of the SED suggests a lower star formation rate or an older stellar population. The strong MIR excess is primarily driven by the AGN, indicating that these galaxies are likely passive, where AGN activity dominates. These SED comparisons highlight the unique nature of SED-AGN-only galaxies, possibly representing a population of passive galaxies where the AGN is the dominant source of energy.

Appendix C: Dependence on model assumptions

When constructing the model grid for the SED fitting (see Sect. 2.2), several assumptions are made regarding the SFH, metallicity, and dust attenuation laws. Here, we test the robustness of AGN identification against changes in these model assumptions using a representative sample of approximately 50 000 galaxies from DESI EDR, covering a broad range of galaxy types (see Appendix D1 in Siudek et al. (2024) for a description of the representative sample).

Table C.1 summarizes the efficiency of AGN identification under different model choices relative to the default configuration. We always change only one parameter at a time, keeping all others fixed (e.g., when applying a nonparametric SFH from Ciesla et al. 2023, we retain the IMF from Chabrier 2003 and SSP models from Bruzual & Charlot 2003). For a full description of our model components, see Sect. 6 in Siudek et al. (2024). We find the following:

-

Changes in the IMF to Salpeter (1955) or the dust emission model to Dale et al. (2014) have negligible impact on the AGN selection efficiency.

-

Adopting the Charlot & Fall (2000) dust attenuation model reduces contamination by star-forming galaxies, but also decreases completeness for BPT-AGN and WISE-AGN.

-

Using a nonparametric SFH (Ciesla et al. 2023) or the SSP models from Maraston (2005) slightly increases the AGN identification rate, but at the cost of slightly increased contamination from star-forming galaxies.

-

Allowing metallicity to vary as a free parameter improves the completeness of the AGN selection and reduces contamination.

-

Switching the AGN emission model to SKIRTOR (Stalevski et al. 2012, 2016) enhances completeness, notably for broad-line AGN (up to 92% recovery) and WISE-AGN (97%), but at the cost of increased contamination from star-forming galaxies.

The choice of model ultimately depends on the scientific goals. Increased contamination from star-forming galaxies is generally undesirable in AGN-focused studies, as it reduces sample purity and can bias physical interpretations. However, any model-driven enhancement or suppression of certain populations should be interpreted cautiously, as it may not reflect the true galaxy demographics. Thus, model selection should reflect the intended use–whether to maximize AGN completeness (e.g., for demographic studies) or to ensure purity (e.g., for SED-based analyses). In the next section we further quantify the performance of the AGN identification depending on the model assumptions.

Impact of model assumptions on the efficiency of SED-based AGN classification.

We additionally note that when WISE W3 and W4 bands are excluded from the SED fitting, the contamination from star-forming galaxies rises significantly, with recovery rates dropping for BPT-AGN, WISE-AGN, and broad-line AGN. In extreme cases where no MIR information is used, virtually all galaxies are classified as AGN (AGNFRAC≥0.1), illustrating the critical importance of MIR data in controlling contamination.

Appendix D: AGN selection using AGNFRAC

We assess the performance of the AGNFRAC parameter, derived from SED fitting, as a tool for AGN classification by performing a ROC analysis for: (i) sources with high-quality mid-IR photometry (FLAGINFRARED = 4) and (ii) those with poor or missing WISE coverage (FLAGINFRARED ≤2). A ROC curve is a representation of the true positive rate (TPR) versus the false positive rate (FPR) for different classification thresholds. The TPR and FPR are defined as