| Issue |

A&A

Volume 701, September 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L5 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Letters to the Editor | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554590 | |

| Published online | 05 September 2025 | |

Letter to the Editor

Starburst-driven galactic outflows

Unveiling the suppressive role of cosmic ray halos

1

Universitäts-Sternwarte, Fakultät für Physik, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Scheinerstr. 1, D-81679 München, Germany

2

Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstr. 1, D-85741 Garching, Germany

3

Excellence Cluster ORIGINS, Boltzmannstr. 2, D-85748 Garching, Germany

4

Theoretical Astrophysics, Department of Earth and Space Science, The University of Osaka, 1-1 Machikaneyama, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-0043, Japan

5

Astrophysical Big Bang Laboratory (ABBL), RIKEN Pioneering Research Institute (PRI), Wakō, Saitama 351-0198, Japan

6

Theoretical Joint Research, Forefront Research Center, The University of Osaka, 1-1 Machikaneyama, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-0043, Japan

7

Kavli IPMU (WPI), UTIAS, The University of Tokyo, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-8583, Japan

8

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 4505 S. Maryland Pkwy, Las Vegas, NV 89154-4002, USA

9

Nevada Center for Astrophysics, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 4505 S. Maryland Pkwy, Las Vegas, NV 89154-4002, USA

⋆ Corresponding authors: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

17

March

2025

Accepted:

24

August

2025

Aims. We investigate the role of cosmic ray (CR) halos in shaping the physical properties of starburst-driven galactic outflows.

Methods. We constructed a model for galactic outflows driven by a continuous central injection of energy, gas, and CRs, where the treatment of CRs accounts for the effect of CR pressure gradients on the flow dynamics. The model parameters were set by the effective properties of a starburst. By analyzing the asymptotic behavior of our model, we derived the launching criteria for starburst-driven galactic outflows and determined their corresponding outflow velocities.

Results. We find that in the absence of CRs, stellar feedback can only launch galactic outflows if the star formation rate (SFR) surface density exceeds a critical threshold proportional to the dynamical equilibrium pressure. In contrast, CRs can always drive slow outflows. Outflows driven by CRs dominate in systems with SFR surface densities below the critical threshold, but their influence diminishes in highly star-forming systems. However, in older systems with established CR halos, the CR contribution to outflows weakens once the outflow reaches the galactic scale height, making CRs ineffective in sustaining outflows in such environments.

Conclusions. Over cosmic time, galaxies accumulate relic CRs in their halos, providing additional non-thermal pressure support that suppresses low-velocity CR-driven outflows. We predict that such low-velocity outflows are expected only in young systems that have yet to build significant CR halos. In contrast, fast outflows in starburst galaxies, where the SFR surface density exceeds the critical threshold, are primarily driven by thermal energy and remain largely unaffected by CR halos.

Key words: cosmic rays / ISM: jets and outflows / intergalactic medium / galaxies: starburst

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1. Introduction

Galaxies with high star-formation surface densities often host large-scale outflow winds. Such winds have been observed in local starbursts, such as Arp 220, M82, and NGC 253 (e.g., Bolatto et al. 2013; Leroy et al. 2015; Walter et al. 2017; Barcos-Muñoz et al. 2018), and are widespread at high-redshifts, where galaxies are typically more compact and have higher star-formation rates relative to their stellar mass (see, e.g., Sugahara et al. 2019; Nianias et al. 2024; Thompson & Heckman 2024). Outflow winds play an important role in redistributing energy, momentum, and baryons between the interstellar medium (ISM) and the halos of galaxies. This makes them a key feedback component that regulates the evolution of galaxy ecosystems. Despite their importance, a complete picture of the role outflow winds play remains unsettled (see Zhang 2018; Thompson & Heckman 2024, for reviews).

Detailed multi-wavelength observations of nearby starburst galaxies with outflows have revealed certain common features, including a bi-conical shape aligned along the minor axis of their host galaxy (Veilleux et al. 2005); extensions reaching tens of kiloparsecs into the halo (Veilleux et al. 2005; Zhang 2018); a terminal “cap” at a few kiloparsecs, for example, at ∼12 kpc in M82 (see Lehnert et al. 1999; Tsuru et al. 2007); and the presence of entrained magnetic fields (e.g., Jones et al. 2019; Lopez-Rodriguez et al. 2021) and high-energy CR particles (for an overview, see Irwin et al. 2024).

Despite these apparent similarities, the physical configuration of individual galactic outflows can vary substantially. For instance, flow velocities ranging up to ∼1000 km s−1 have been reported (e.g., Bradshaw et al. 2013; Heckman et al. 2015; Cicone et al. 2016; Cazzoli et al. 2016; Xu et al. 2022; Taylor et al. 2024), while densities and mass-loading factors span over 1.5 orders of magnitude (e.g., Xu et al. 2023a; Heckman et al. 2015). This diversity can be attributed to differences in the energy, matter, and momentum being supplied to an outflow by its host galaxy (Zhang 2018; Thompson & Heckman 2024), the underlying driving microphysics (Yu et al. 2020), and environmental factors – particularly the conditions of the surrounding halo.

Hot halo gas exerts inward pressure. This can oppose the development of a galactic outflow by reducing its velocity and limiting its extension compared to systems without a halo (e.g., Shin et al. 2021). Due to its ability to confine metal-enriched outflows and restrict the dispersal of ejecta, halo gas ram pressure has been considered as instrumental in regulating baryonic recycling flows and enabling the enrichment of the circumgalactic medium (CGM) of a galaxy (Ferrara et al. 2005). In addition to this thermal pressure from the hot gas, galaxy halos may also host a reservoir of CRs. These CRs may constitute a relic population that has been transported by advection, bubbles associated with outflows, or the activity of a central supermassive black hole (see, e.g., Owen et al. 2019; Recchia et al. 2021; Shimoda & Inutsuka 2022).

Halo CRs can modify the structure of the CGM and alter baryonic flows within galaxy halos (for reviews, see Ruszkowski & Pfrommer 2023; Owen et al. 2023). Simulations of Milky Way-mass galaxies suggest that CRs provide additional pressure support to sustain a multi-phase halo gas structure at low temperatures and can propel cool gas out to hundreds of kiloparsecs (Butsky & Quinn 2018; Ji et al. 2020). CR-driven winds can even push gas beyond the virial radius (Quataert & Hopkins 2025). Due to the long CR survival time in halos, these feedback effects can continue to manifest long after the end of the mechanical processes that originally generated the CRs (Quataert & Hopkins 2025). Halo CRs can also operate alongside hot halo gas to provide an inward non-thermal pressure that counteracts developing outflows. This is illustrated in Fig. 1, which compares the suppressive effect of galaxy halos and the implications for baryonic recycling.

|

Fig. 1. Schematic of the structure of a starburst-driven outflow embedded in a galactic halo, propelled by thermal gas pressure and/or non-thermal CR pressure. The scale height of the warm ISM is indicated. All galaxies are embedded in a gravitational potential, g, which opposes the outflow. Superscripts + and − on quantities indicate whether each term contributes to or opposes the outflow, respectively. Left: In the absence of a substantial gas halo, outflowing gas is unconfined, allowing it to escape beyond the galaxy ecosystem against the galaxy’s gravitational potential. Center: As the galaxy builds up its stellar mass, feedback processes form a hot gas halo that suppresses the outflow, promoting baryonic recycling and enriching the CGM (see Ferrara et al. 2005; Shin et al. 2021). Right: When CRs are supplied to the halo, they accumulate over time, introducing a non-thermal halo component. Since non-thermal CR pressure gradients operate over larger length scales than thermal pressure gradients, an outflow erupting into the galaxy halo encounters distinct layers where thermally dominated and CR-dominated pressure gradients hinder its development. |

In this study, we examine how an extended cosmic-ray halo influences the development of galactic winds driven by cosmic-ray and thermal gas pressure, and we establish criteria for outflow breakout. Our model considers the asymptotic behavior of winds driven by continuous central feedback on scales ranging from a few up to hundreds of kiloparsecs above the disk and into the halo, over timescales of ∼10 Myr for shock breakout and 10–100 Myr for approaching the terminal velocity. Although our approach does not capture the bursty nature of star formation or CR transport in evolving magnetic fields, it provides a framework for assessing the long-term impact of cosmic-ray halos on outflow dynamics.

2. Starburst-driven outflows in galaxy halos

The collective feedback from a central galactic starburst can initiate a blastwave, which may develop into a sustained galactic wind if the starburst activity is continuous. Typically, about one supernova (SN) explodes per ∼100 M⊙ of star formation, with the exact rate dependent on the choice of the stellar initial mass function (e.g., Leitherer et al. 1999). We can therefore link the SN event rate,  , to the SFR of a galaxy by ℛSF ∼ 100 M⊙ ℛSN. Observationally, star formation activity is typically quantified using the SFR surface density, ΣSFR. This can be related to ℛSF by considering that most star formation contributing to the blastwave occurs within a cylindrical region with a radius comparable to the disk scale height, ∼Hs, of a galaxy (defined by Eq. (A.2)), i.e.,

, to the SFR of a galaxy by ℛSF ∼ 100 M⊙ ℛSN. Observationally, star formation activity is typically quantified using the SFR surface density, ΣSFR. This can be related to ℛSF by considering that most star formation contributing to the blastwave occurs within a cylindrical region with a radius comparable to the disk scale height, ∼Hs, of a galaxy (defined by Eq. (A.2)), i.e.,  . As we discuss in Appendix B, the time it takes to establish an outflow ranges from several tens to several hundreds of megayears (see also, e.g., Rathjen et al. 2023, 2025; Girichidis et al. 2024), while individual starburst episodes only last about 10 Myr (Rathjen et al. 2023). Thus it is important to note that the SFR entering our model should be interpreted as an average over many starburst episodes that collectively drive an outflow.

. As we discuss in Appendix B, the time it takes to establish an outflow ranges from several tens to several hundreds of megayears (see also, e.g., Rathjen et al. 2023, 2025; Girichidis et al. 2024), while individual starburst episodes only last about 10 Myr (Rathjen et al. 2023). Thus it is important to note that the SFR entering our model should be interpreted as an average over many starburst episodes that collectively drive an outflow.

The injection rates of mass ( , for Mej = Mej, 0 M⊙ as the typical SN ejecta mass) and energy (

, for Mej = Mej, 0 M⊙ as the typical SN ejecta mass) and energy ( , for ESN = 1051 E51 erg as the typical mechanical energy supplied by an SN) supplied to an expanding blastwave from a galactic starburst can be linked to the SFR through the mass- and energy-loading factors

, for ESN = 1051 E51 erg as the typical mechanical energy supplied by an SN) supplied to an expanding blastwave from a galactic starburst can be linked to the SFR through the mass- and energy-loading factors  and

and  , respectively, where εw is a thermalization efficiency factor accounting for energy dissipation in the system (see, e.g., Thompson et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2017; Steinwandel et al. 2024). Similarly, we account for CR energy-dissipation with εw, CR, which for simplicity we set to εw, CR = εw = ηe. For convenience, we introduced the scaling parameters ηm, −2 = ηm/0.01, ηe, −2 = ηe/0.01, and εw, −2 = εw/0.01. The supply of CRs to the wind is parametrized by fCR, representing the CR energy fraction at the galactic mid-plane. In our model, these parameters are treated as constants, remaining fixed throughout the evolution of the outflow, and the flow is considered to be driven by a combination of central thermal and kinetic energy injection and CR pressure gradients.

, respectively, where εw is a thermalization efficiency factor accounting for energy dissipation in the system (see, e.g., Thompson et al. 2016; Kim et al. 2017; Steinwandel et al. 2024). Similarly, we account for CR energy-dissipation with εw, CR, which for simplicity we set to εw, CR = εw = ηe. For convenience, we introduced the scaling parameters ηm, −2 = ηm/0.01, ηe, −2 = ηe/0.01, and εw, −2 = εw/0.01. The supply of CRs to the wind is parametrized by fCR, representing the CR energy fraction at the galactic mid-plane. In our model, these parameters are treated as constants, remaining fixed throughout the evolution of the outflow, and the flow is considered to be driven by a combination of central thermal and kinetic energy injection and CR pressure gradients.

2.1. CR halos and their effects on outflows

Several observational studies have suggested the presence of extended CR reservoirs in galactic halos. These observations include a γ-ray halo around M31 reaching to hundreds of kiloparsecs, which likely traces an interacting population of hadronic CRs (Recchia et al. 2021); γ-ray emission originating from halo clouds at kiloparsec heights around the Milky Way (Tibaldo et al. 2015); and kiloparsec-scale synchrotron emission from edge-on galaxies (e.g., Mulcahy et al. 2018; Mora-Partiarroyo et al. 2019). It has also been proposed that diffuse X-ray emission from the halos of the Milky Way, M31, and lower-mass galaxies could originate from inverse Compton scattering driven by a leptonic CR population (Hopkins et al. 2025).

The formation of CR halos is a consequence of CR production during galaxy evolution. The long energy loss times of hadronic CRs in these environments (see Appendix A.1) ensure that most of the CR energy density supplied to a galaxy halo during its development can survive to the present day. Galaxies with significant historical stellar mass buildup are expected to host rich CR halos, even if their current star formation activity is low. Observations in γ-rays tentatively support this distinction, with CR halos primarily reported around massive late-type galaxies, while lower-mass galaxies show no indication of hosting such structures (Pshirkov & Nizamov 2024).

To assess whether a CR halo can influence a developing outflow, the CR pressure contributions from both the halo and the outflow can be compared at a given altitude, z (see Appendix A; Eqs. (A.3) and (A.7)). For CRs to drive an outflow, the outward CR pressure must exceed the inward pressure from the halo CRs. When external and internal CR pressures become comparable, the driving effect of CR pressure gradients diminishes.

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the presence of a CR halo is expected to frustrate slow outflows if its scale height significantly exceeds the altitude where external and internal CR pressures are equal, zCR. In units of the disk scale height, Hs, this CR pressure equilibrium height is given by

where σ = 10 σ1 km/s is the gas velocity dispersion and v∞, 2 is the rescaled terminal flow velocity defined as v∞ = 100 v∞, 2 km/s at large distances from the galactic plane. Equation (1) indicates that zCR is typically located at low altitudes for most galaxies. This suggests that CR-driven outflows are easily suppressed by the presence of an extended CR halo, if the halo has a scale-height ≫Hs. Galactic winds in systems with a well-developed CR halo are therefore expected to experience suppression, with their driving primarily dependent on thermal and kinetic energy-injection rather than CR pressure.

2.2. Outflow breakout criterion and terminal velocity

A minimum critical SFR surface density can be defined in the absence of a CR halo for an outflow to break out from a galaxy (see Appendix A.2). This is given by

where nH, mp = n0 cm−3 is introduced as the mid-plane gas number density. In a strong star-starburst (i.e., when ΣSFR ≫ ΣSFR, c), the maximum flow speed that can develop tends toward an asymptotic limit (see Eq. (A.10)).

Cosmic ray-driven outflows can always be launched without a specific breakout criterion. However, in weak star formation scenarios (i.e., ΣSFR ≪ ΣSFR, c), only very slow flow velocities can be achieved:

In this regime, the CR pressure equilibrium height reduces to

which decreases as the CR supply to the system increases. This indicates that a CR halo strongly suppresses weak outflows that rely on CR driving (see the right panel of Fig. 1).

In the strong starburst limit (when ΣSFR ≫ ΣSFR, c), much faster terminal velocities are expected:

The CR pressure equilibrium height in this regime is then

Although the inward halo CR pressure overtakes the outward flow-driving CR pressure near the disk scale height, the independence of  from fCR suggests that outflows in this regime are momentum dominated. Such outflows are unlikely to be significantly influenced by the presence of a CR halo, with thermal gas pressure likely playing a more critical role in regulating flow dynamics (see the central panel of Fig. 1).

from fCR suggests that outflows in this regime are momentum dominated. Such outflows are unlikely to be significantly influenced by the presence of a CR halo, with thermal gas pressure likely playing a more critical role in regulating flow dynamics (see the central panel of Fig. 1).

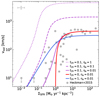

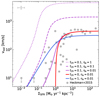

The terminal velocities predicted by our model allow for comparison with observations. Figure 2 shows terminal outflow velocities as a function of SFR surface density for a fiducial model with (dimensionless) parameters n0 = 1, σ1 = 1, and ηm, −2 = 5 and varying values of fCR and ηe, −2, as indicated in the legend. These calculations assume that all galaxies in the sample share a similar dynamical equilibrium pressure: PDE ∼ ρmpσ2 ∼ GΣ2 (Ostriker & Kim 2022), where ρmp is the galactic mid-plane gas volume density and Σ is the corresponding surface density that sets ΣSFR, c. For comparison, observed outflow velocities for a sample of nearby starburst galaxies with stellar masses in the range log10(M*/M⊙)∈[7.1 − 10.9] (Heckman et al. 2015) are also shown in the figure. Our model captures the general trend of observed flow velocities with parameter choices of εw, −2 ∼ ηe, −2 ∼ 1 and ηm, −2 ∼ Mej, 0 ∼ 5. These choices align well with the energy and mass loading factors reported in numerical simulations of galactic outflows at altitudes of a few kiloparsecs (e.g., Kim & Ostriker 2018; Rathjen et al. 2021; Steinwandel et al. 2024; Quataert & Hopkins 2025).

|

Fig. 2. Terminal outflow velocities as a function of star formation rate surface density for different choices of CR energy fractions, fCR, and energy loading factors, ηe. The model predictions are compared with data from Heckman et al. (2015), which show measured outflow velocities for a sample of nearby starburst galaxies with stellar masses in the range log10(M*/M⊙) ∈ [7.1 − 10.9]. Typical uncertainties are indicated in the top-left corner. The model with ηe ∼ 0.01 and fCR ∼ 0.1 provides a good match with the observed data. Models with higher energy loading values (ηe) generally predict outflow velocities in excess of the observations. The transition from slow outflows in weak starbursts to fast outflows in strong starbursts is best captured by models with fCR > 0. |

3. Discussion and implications

The structure of galactic winds has been extensively studied through theoretical approaches (e.g., Chevalier & Clegg 1985; Fielding & Bryan 2022; Modak et al. 2023), detailed numerical simulations (e.g., Kim & Ostriker 2018; Vasiliev et al. 2023; Quataert & Hopkins 2025), and observational studies (e.g., Krieger et al. 2019; Xu et al. 2023b; Bolatto et al. 2024). These studies have shown that galactic winds are ubiquitous, particularly among star-forming galaxies, and that galaxies with high SFRs tend to drive faster and hotter winds. However, not all galaxies show clear signatures of outflows. Some systems show that gas launched from the ISM is recycled within a galaxy ecosystem rather than expelled (Marasco et al. 2023). While the qualitative framework for wind launching is well established (see Thompson & Heckman 2024, for a review), few studies have quantified outflow launching conditions (e.g., Heckman et al. 2015; Orr et al. 2022).

Heckman et al. (2015) examined outflow speeds of galactic winds in a sample of nearby starbursts and reported a sharp drop in flow velocities when the central SFR surface density fell below a critical threshold of  . Our model shows that this critical SFR surface density arises due to the depth of the gravitational potential, which can only be overcome by sufficiently strong starbursts. The predicted value aligns with observations when considering typical dynamical equilibrium pressures set by the weight of the ISM, together with wind-loading parameters that are consistent with recent numerical studies of galactic winds in dwarf (Steinwandel et al. 2024) and spiral galaxies in the local Universe (Quataert & Hopkins 2025). However, we note that other studies have found significantly higher mass and energy loading, depending on the methodology used (e.g., Muratov et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2024).

. Our model shows that this critical SFR surface density arises due to the depth of the gravitational potential, which can only be overcome by sufficiently strong starbursts. The predicted value aligns with observations when considering typical dynamical equilibrium pressures set by the weight of the ISM, together with wind-loading parameters that are consistent with recent numerical studies of galactic winds in dwarf (Steinwandel et al. 2024) and spiral galaxies in the local Universe (Quataert & Hopkins 2025). However, we note that other studies have found significantly higher mass and energy loading, depending on the methodology used (e.g., Muratov et al. 2015; Smith et al. 2024).

Orr et al. (2022) investigated the feedback from star formation in a marginally Toomre-stable disk. They proposed that a young star cluster could launch an outflow if the starburst-driven shock reaches the disk scale height before its speed drops below the ISM’s velocity dispersion. By assuming the formation of one star cluster per orbital timescale, they derived an expression for the critical SFR surface density, which is in rough agreement with the threshold found observationally by Heckman et al. (2015). However, their study does not account for the effects of gravity, which would alter the wind-launching criterion.

Most numerical simulations of starburst-driven galactic winds show that the inclusion of CRs improves their ability to drive warm outflows with high mass-loading factors (e.g., Girichidis et al. 2016; Rathjen et al. 2021; Chan et al. 2022; Armillotta et al. 2024). This is in agreement with our results, which indicate that outflow speed in the CR-dominated regime is independent of the mass-loading factor and suggest that CR-driven winds can sustain substantial mass-loading before being significantly slowed. However, current numerical models do not typically include a pre-existing CR halo in their initial conditions. Instead, they only model the accumulation of CRs within a galaxy ecosystem over time, usually as a consequence of stellar feedback. The widespread findings of substantial feedback impacts from CR-driven outflows in the literature may reflect this limitation – a situation that has certain parallels with earlier numerical studies that lacked CGM thermal pressure, leading to unrealistically strong outflows in simulations of isolated galaxies (Shin et al. 2021).

We emphasize that CR-driven outflows are unlikely to operate efficiently in massive galaxies with deep gravitational potentials. Numerical studies (e.g., Jacob et al. 2018; Girichidis et al. 2024) have shown that in halos with Mhalo ≳ 1012 M⊙, CR-driven winds are largely suppressed. This is due to a combination of strong gravitational binding, which raises the threshold for escape, and enhanced CR energy losses via Coulomb and hadronic interactions, which limit the dynamical role of CR pressure. These findings are consistent with our model, in which the outward CR pressure gradient becomes ineffective in the presence of an established CR halo, particularly when the halo’s scale height greatly exceeds the CR pressure equilibrium height. We thus interpret the CR suppression mechanism in our model as particularly relevant for lower-mass or early-phase starburst galaxies, while in more massive systems, thermal or radiation-driven mechanisms likely dominate the wind launching process.

At high redshift, several studies have reported high outflow velocities up to 1000 km s−1 (Sugahara et al. 2019; Xu et al. 2022). In general, higher outflow speeds require higher energy loading factors and lower mass loading factors. Observations suggest that high-redshift galaxies tend to be compact and turbulent (Genzel et al. 2023), with high gas fractions and surface densities (e.g., Genzel et al. 2011) and low metallicities (Maiolino et al. 2008). Since the critical SFR surface density scales with the dynamical equilibrium pressure as  , thermally driven outflows become ineffective in a highly turbulent high surface-density environment. On the other hand, lower metallicities result in longer cooling times, leading to higher momentum loading (Oku et al. 2022). If mass-loading factors in high-redshift galaxies are comparable to those in low-redshift galaxies, then lower metallicities could explain the high observed outflow velocities in high-redshift galaxies, provided that the increased ISM weight does not suppress outflows.

, thermally driven outflows become ineffective in a highly turbulent high surface-density environment. On the other hand, lower metallicities result in longer cooling times, leading to higher momentum loading (Oku et al. 2022). If mass-loading factors in high-redshift galaxies are comparable to those in low-redshift galaxies, then lower metallicities could explain the high observed outflow velocities in high-redshift galaxies, provided that the increased ISM weight does not suppress outflows.

Curiously, the critical SFR surface density exhibits a stronger dependence on gas surface density than on the SFR surface density itself, which follows  (Kennicutt 1989). This suggests that, counterintuitively, fast thermally powered galactic outflows are expected to be more common at low surface densities, such as in dwarf galaxies, while being suppressed in extreme star-forming environments – including massive clumps in high-redshift galaxies (Genzel et al. 2011) and the proposed feedback-free starburst galaxies at z ∼ 10 (Finkelstein et al. 2023; Dekel et al. 2023). At high redshifts, CR-driven slow outflows may be more prevalent in these systems, as there would not have been sufficient time for them to establish a CR halo capable of suppressing outflows. Indeed, highly mass-loaded outflows are essential for regulating star formation and explaining the observed metallicity trends at high redshift (Toyouchi et al. 2025), which can be naturally accounted for by CR-driven outflows.

(Kennicutt 1989). This suggests that, counterintuitively, fast thermally powered galactic outflows are expected to be more common at low surface densities, such as in dwarf galaxies, while being suppressed in extreme star-forming environments – including massive clumps in high-redshift galaxies (Genzel et al. 2011) and the proposed feedback-free starburst galaxies at z ∼ 10 (Finkelstein et al. 2023; Dekel et al. 2023). At high redshifts, CR-driven slow outflows may be more prevalent in these systems, as there would not have been sufficient time for them to establish a CR halo capable of suppressing outflows. Indeed, highly mass-loaded outflows are essential for regulating star formation and explaining the observed metallicity trends at high redshift (Toyouchi et al. 2025), which can be naturally accounted for by CR-driven outflows.

We note that our model is intended to be an idealized steady-state framework that captures the asymptotic behavior of outflows under continuous feedback. While this does not resolve the detailed time-dependent evolution of bursty star formation or episodic feedback cycles, it provides a useful time-averaged description representative of either (i) long-duration starburst episodes or (ii) the cumulative effects of successive, shorter bursts over galactic dynamical timescales. A full treatment of the time dependence – including intermittent injection, CR streaming and diffusion, and adiabatic losses in 3D – will be essential in future work to extend the applicability of our model to more realistic galactic evolution scenarios.

4. Conclusions

In this study, we have constructed a galactic outflow model driven by a continuous central feedback source, and we included the effects of CR pressure in the outflow and the surrounding galaxy halo. We applied this model to a starburst galaxy to assess how the presence of a CR halo may influence outflow development. We found the following:

-

In the absence of CRs, galactic outflows are only launched if the SFR surface density exceeds a critical threshold proportional to the dynamic equilibrium pressure. At high SFR surface densities, these momentum-driven outflows approach the ejecta speed, reaching up to thousands of km s−1.

-

The CRs can always drive slow outflows. We identified two different regimes: slow CR-dominated outflows at SFR surface densities below the critical threshold and fast momentum-driven outflows at high SFR surface densities.

-

In the presence of an extended CR halo, CRs become ineffective in sustaining outflows beyond the galactic scale height, leading to the suppression of CR-driven winds.

While our simplified approach is subject to substantial limitations (see Appendix C), it provides useful insights into the qualitative behavior of starburst-driven outflows and the influence of a CR halo. However, more detailed studies – including numerical simulations with CR halos as an initial condition – are needed to properly explore the physical impacts of CRs on the dynamical processes within galaxy halos.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous referee for their insightful comments and suggestions that helped to improve the quality of this work. This research was funded in part by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2094 – 390783311. E.R.O is an international research fellow under the Postdoctoral Fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP22F22327, and also acknowledges support from the RIKEN Special Postdoctoral Researcher Program for junior scientists. This work was supported in part by the MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI grant numbers 20H00180, 22K21349, 24H00002, and 24H00241 (K.N.). K.N. acknowledges the support from the Kavli IPMU, the World Premier Research Centre Initiative (WPI), UTIAS, the University of Tokyo.

References

- Armillotta, L., Ostriker, E. C., Kim, C.-G., & Jiang, Y.-F. 2024, ApJ, 964, 99 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barcos-Muñoz, L., Aalto, S., Thompson, T. A., et al. 2018, ApJ, 853, L28 [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, M., Burkert, A., & Schartmann, M. 2015, MNRAS, 448, 1007 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bolatto, A. D., Warren, S. R., Leroy, A. K., et al. 2013, Nature, 499, 450 [Google Scholar]

- Bolatto, A. D., Levy, R. C., Tarantino, E., et al. 2024, ApJ, 967, 63 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, E. J., Almaini, O., Hartley, W. G., et al. 2013, MNRAS, 433, 194 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Buck, T., Pfrommer, C., Pakmor, R., Grand, R. J. J., & Springel, V. 2020, MNRAS, 497, 1712 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Butsky, I. S., & Quinn, T. R. 2018, ApJ, 868, 108 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cazzoli, S., Arribas, S., Maiolino, R., & Colina, L. 2016, A&A, 590, A125 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, T. K., Kereš, D., Hopkins, P. F., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 488, 3716 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, T. K., Kereš, D., Gurvich, A. B., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 517, 597 [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, R. A., & Clegg, A. W. 1985, Nature, 317, 44 [Google Scholar]

- Cicone, C., Maiolino, R., & Marconi, A. 2016, A&A, 588, A41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, A., Sarkar, K. C., Birnboim, Y., Mandelker, N., & Li, Z. 2023, MNRAS, 523, 3201 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dermer, C. D., & Menon, G. 2009, High Energy Radiation from Black Holes: Gamma Rays, Cosmic Rays, and Neutrinos [Google Scholar]

- Devine, D., & Bally, J. 1999, ApJ, 510, 197 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo, P., Bournaud, F., Martig, M., et al. 2008, A&A, 492, 31 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, A., Scannapieco, E., & Bergeron, J. 2005, ApJ, 634, L37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding, D. B., & Bryan, G. L. 2022, ApJ, 924, 82 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. L., Bagley, M. B., Ferguson, H. C., et al. 2023, ApJ, 946, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genzel, R., Newman, S., Jones, T., et al. 2011, ApJ, 733, 101 [Google Scholar]

- Genzel, R., Jolly, J. B., Liu, D., et al. 2023, ApJ, 957, 48 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Girichidis, P., Naab, T., Walch, S., et al. 2016, ApJ, 816, L19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Girichidis, P., Werhahn, M., Pfrommer, C., Pakmor, R., & Springel, V. 2024, MNRAS, 527, 10897 [Google Scholar]

- Heckman, T. M., Alexandroff, R. M., Borthakur, S., Overzier, R., & Leitherer, C. 2015, ApJ, 809, 147 [Google Scholar]

- Herenz, E. C., Kusakabe, H., & Maulick, S. 2025, PASJ, accepted [arXiv:2502.16969] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, P. F., Butsky, I. S., Panopoulou, G. V., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 516, 3470 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, P. F., Butsky, I. S., Ji, S., & Kereš, D. 2023, MNRAS, 522, 2936 [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, P. F., Quataert, E., Ponnada, S. B., & Silich, E. 2025, Open J. Astrophys., 8, 78 [Google Scholar]

- Irwin, J., Beck, R., Cook, T., et al. 2024, Galaxies, 12, 22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, S., Pakmor, R., Simpson, C. M., Springel, V., & Pfrommer, C. 2018, MNRAS, 475, 570 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S., Chan, T. K., Hummels, C. B., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 496, 4221 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. J., Dowell, C. D., Lopez Rodriguez, E., et al. 2019, ApJ, 870, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kafexhiu, E., Aharonian, F., Taylor, A. M., & Vila, G. S. 2014, Phys. Rev. D, 90, 123014 [Google Scholar]

- Karwin, C. M., Murgia, S., Campbell, S., & Moskalenko, I. V. 2019, ApJ, 880, 95 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kennicutt, R. C., Jr. 1989, ApJ, 344, 685 [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.-G., & Ostriker, E. C. 2015, ApJ, 802, 99 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.-G., & Ostriker, E. C. 2018, ApJ, 853, 173 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.-G., Ostriker, E. C., & Raileanu, R. 2017, ApJ, 834, 25 [Google Scholar]

- Koo, B.-C., & McKee, C. F. 1990, ApJ, 354, 513 [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, N., Bolatto, A. D., Walter, F., et al. 2019, ApJ, 881, 43 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Krumholz, M. R., Crocker, R. M., Xu, S., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 493, 2817 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, L., Ostriker, E. C., Kim, C.-G., Kim, J.-G., & Bryan, G. L. 2024, ApJ, 970, 18 [Google Scholar]

- Laumbach, D. D., & Probstein, R. F. 1969, J. Fluid Mech., 35, 53 [Google Scholar]

- Lehnert, M. D., Heckman, T. M., & Weaver, K. A. 1999, ApJ, 523, 575 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leitherer, C., Schaerer, D., Goldader, J. D., et al. 1999, ApJS, 123, 3 [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, A. K., Walter, F., Martini, P., et al. 2015, ApJ, 814, 83 [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Rodriguez, E., Guerra, J. A., Asgari-Targhi, M., & Schmelz, J. T. 2021, ApJ, 914, 24 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maiolino, R., Nagao, T., Grazian, A., et al. 2008, A&A, 488, 463 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Marasco, A., Belfiore, F., Cresci, G., et al. 2023, A&A, 670, A92 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Modak, S., Quataert, E., Jiang, Y.-F., & Thompson, T. A. 2023, MNRAS, 524, 6374 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Partiarroyo, S. C., Krause, M., Basu, A., et al. 2019, A&A, 632, A10 [NASA ADS] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mulcahy, D. D., Horneffer, A., Beck, R., et al. 2018, A&A, 615, A98 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Muratov, A. L., Kereš, D., Faucher-Giguère, C.-A., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 454, 2691 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nianias, J., Lim, J., & Yeung, M. 2024, ApJ, 963, 19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oku, Y., Tomida, K., Nagamine, K., Shimizu, I., & Cen, R. 2022, ApJS, 262, 9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Orr, M. E., Fielding, D. B., Hayward, C. C., & Burkhart, B. 2022, ApJ, 932, 88 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ostriker, E. C., & Kim, C.-G. 2022, ApJ, 936, 137 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ostriker, J. P., & McKee, C. F. 1988, Rev. Mod. Phys., 60, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Owen, E. R., Jacobsen, I. B., Wu, K., & Surajbali, P. 2018, MNRAS, 481, 666 [Google Scholar]

- Owen, E. R., Jin, X., Wu, K., & Chan, S. 2019, MNRAS, 484, 1645 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, E. R., Wu, K., Inoue, Y., Yang, H. Y. K., & Mitchell, A. M. W. 2023, Galaxies, 11, 86 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pshirkov, M. S., & Nizamov, B. A. 2024, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2410.02066] [Google Scholar]

- Quataert, E., & Hopkins, P. F. 2025, Open J. Astrophys., 8, 66 [Google Scholar]

- Rathjen, T.-E., Naab, T., Girichidis, P., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 504, 1039 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rathjen, T.-E., Naab, T., Walch, S., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 522, 1843 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rathjen, T.-E., Walch, S., Naab, T., et al. 2025, MNRAS, 540, 1462 [Google Scholar]

- Recchia, S., Gabici, S., Aharonian, F. A., & Niro, V. 2021, ApJ, 914, 135 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ruszkowski, M., & Pfrommer, C. 2023, A&ARv, 31, 4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoda, J., & Inutsuka, S.-I. 2022, ApJ, 926, 8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, E.-J., Kim, J.-H., & Oh, B. K. 2021, ApJ, 917, 12 [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M. C., Fielding, D. B., Bryan, G. L., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 527, 1216 [Google Scholar]

- Steinwandel, U. P., Kim, C.-G., Bryan, G. L., et al. 2024, ApJ, 960, 100 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Su, M., Slatyer, T. R., & Finkbeiner, D. P. 2010, ApJ, 724, 1044 [Google Scholar]

- Sugahara, Y., Ouchi, M., Harikane, Y., et al. 2019, ApJ, 886, 29 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, E., Maltby, D., Almaini, O., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 535, 1684 [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, T. A., & Heckman, T. M. 2024, ARA&A, 62, 529 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, T. A., Quataert, E., Zhang, D., & Weinberg, D. H. 2016, MNRAS, 455, 1830 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tibaldo, L., Digel, S. W., Casandjian, J. M., et al. 2015, ApJ, 807, 161 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toyouchi, D., Yajima, H., Ferrara, A., & Nagamine, K. 2025, MNRAS, submitted [arXiv:2502.12538] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuru, T. G., Ozawa, M., Hyodo, Y., et al. 2007, PASJ, 59, 269 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Vasiliev, E. O., Drozdov, S. A., Nath, B. B., Dettmar, R.-J., & Shchekinov, Y. A. 2023, MNRAS, 520, 2655 [Google Scholar]

- Veilleux, S., Cecil, G., & Bland-Hawthorn, J. 2005, ARA&A, 43, 769 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Walter, F., Bolatto, A. D., Leroy, A. K., et al. 2017, ApJ, 835, 265 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Werhahn, M., Girichidis, P., Pfrommer, C., & Whittingham, J. 2023, MNRAS, 525, 4437 [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X., Heckman, T., Henry, A., et al. 2022, ApJ, 933, 222 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X., Heckman, T., Henry, A., et al. 2023a, ApJ, 948, 28 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X., Heckman, T., Yoshida, M., Henry, A., & Ohyama, Y. 2023b, ApJ, 956, 142 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H. Y. K., Gaspari, M., & Marlow, C. 2019, ApJ, 871, 6 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B. P. B., Owen, E. R., Wu, K., & Ferreras, I. 2020, MNRAS, 492, 3179 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D. 2018, Galaxies, 6, 114 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zubovas, K., & Nayakshin, S. 2012, MNRAS, 424, 666 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Halo and outflow model

A.1. Halo model and CR timescales

In our model, the galaxy halo consists of a thermal gas component and a non-thermal CR component. The gas is treated as an infinite slab in vertical hydrostatic equilibrium with a density profile given by

and a velocity dispersion of σ = 10 σ1 km s−1, where ρmp = μ mH nH, mp is the mid-plane gas density, μ = 1.4 is the mean atomic weight, and nH, mp = n0 cm−3 is the number density of the gas. The disk scale-height is given by

(Behrendt et al. 2015). The expected profile of the CR component in the halo is uncertain and depends on the underlying CR transport physics, which remain unsettled. It has been suggested that buoyant bubbles may redistribute CRs in the halo (Recchia et al. 2021). Such bubbles, blown by SN-powered winds in starburst regions of a galaxy (e.g., Herenz et al. 2025), may be associated with outflows when they begin to fragment (e.g., above a cap similar to that seen in M82; Devine & Bally 1999), or could even be attributed to buoyant structures inflated by intensive energetic outbursts akin to the Galactic Fermi bubbles (e.g., Su et al. 2010; Zubovas & Nayakshin 2012; Recchia et al. 2021) analagous to AGN-inflated bubbles in Galaxy clusters (e.g., Yang et al. 2019). Observations of M31 do not yet strongly favor a particular CR distribution profile (Karwin et al. 2019), and detailed physical modeling of the CR halo is beyond the scope of the current work. We therefore adopt a simple spatially uniform CR distribution in the halo, effectively treating it as a CR bath in which an outflow develops. This approach is sufficient to obtain qualitative insights into the effects of a CR halo on outflow development, with more detailed modeling of CR transport mechanisms in galaxy halos left to future work.

To achieve a sensible normalization at low altitudes where CR pressure most strongly influences outflow development, the CR content of the halo is set to match the CR energy fraction at the galactic mid-plane. The halo CR pressure can then be expressed as

where fCR is the fraction of energy supplied by the starburst to CRs at the galactic mid-plane, γ = 5/3 is the thermal gas adiabatic index, and γ = 4/3 is the CR fluid adiabatic index. This configuration creates a layered halo structure, with thermal gas pressure dominating at low altitudes and CR pressure becoming more important at higher altitudes (see the right panel of Fig. 1).

The CRs in the galaxy halo are likely primarily hadronic. This is because fast electron cooling in typical galactic conditions limits the electron population. Once deposited in the halo, CR hadrons experience few interaction or energy loss channels, allowing them to survive over Gyr timescales (see Fig. A.1). Adiabatic losses, streaming losses, and diffusive energy gains in micro-turbulence have only modest effects on the overall CR spectrum. Detailed simulations show that these processes rarely impact CR energies significantly in galaxy halos, typically contributing no more than 10 percent level corrections (Chan et al. 2019; Hopkins et al. 2022). We therefore neglect these effects in our model. Without significant cooling or absorption channels, CR hadrons are expected to accumulate in the galaxy halo, forming a fossil record of the host galaxy’s CR power generation history.

|

Fig. A.1. Characteristic timescales for a CR proton to undergo a hadronic interaction with ambient gas (pp interactions) or radiation (pγ interactions) shown for typical conditions in the galaxy interior (red lines) and halo (black lines). For the galaxy interior, we adopt a gas density of 1 cm−3 and stellar radiation fields consisting of a stellar component with T = 7100 K and an energy density of ∼0.7 eV cm−3, with a dust component at T = 60 K and an energy density of ∼0.3 eV cm−3. For halo conditions, we consider a reduced gas density of 10−3 cm−3, with radiation energy densities scaled down by a factor of 100. pγ losses with cosmological microwave background radiation at z = 0 are included for both galaxy interior and halo conditions, with photo-pair and photo-pion interactions occurring at the same rate in both environments. The Hubble timescale is shown in gray. Interaction timescales exceeding this (i.e., within the shaded pink region) practically do not occur. Hadronic pp and pγ interaction timescales are calculated following the approach of Owen et al. (2018), assuming that the invariant energy of an interaction is dominated by that supplied by the CR. For pp interactions, this uses the total inelastic cross-section parametrization of Kafexhiu et al. (2014). For pγ pion-production losses, the step-function approximation to the cross-section proposed by Dermer & Menon (2009) is adopted. Bethe-Heitler losses are treated using the simplified cross-section from the same reference, but with fitting parameters updated according to Owen et al. (2018), suitable for the energy range considered here. |

A.2. Outflow model

We consider that an outflow is driven by a continuous injection of energy, momentum, CRs, and thermal gas, forming an expanding super-bubble that launches a galactic wind. This approach allows us to establish a criterion for wind launching and derive an analytical expression for the outflow velocity. To do this, we started from the blastwave equation of motion (Ostriker & McKee 1988) under the thin-shell and sector approximations (e.g., Laumbach & Probstein 1969; Koo & McKee 1990) in order to derive an analytically tractable equation of motion suitable for modeling CR-driven outflows:

Here z = z(t) is the shock radius at time t after the onset of shock expansion, ż and  are the instantaneous expansion velocity and acceleration of a thin shell following the expanding shock, M = ∫ρz2dz is the swept-up mass, and ΔP and ΔPCR are the thermal and non-thermal pressure differences between the shocked and the un-shocked gas, respectively. The gravitational acceleration, g < 0, for a single-component, isothermal slab in vertical hydrostatic equilibrium is given by

are the instantaneous expansion velocity and acceleration of a thin shell following the expanding shock, M = ∫ρz2dz is the swept-up mass, and ΔP and ΔPCR are the thermal and non-thermal pressure differences between the shocked and the un-shocked gas, respectively. The gravitational acceleration, g < 0, for a single-component, isothermal slab in vertical hydrostatic equilibrium is given by

The speed of the ejecta, vej, is

Other terms retain the definitions provided in the main text (see section 2).

In the sector approximation (Laumbach & Probstein 1969), we follow the one-zone dynamics of a shell-segment per unit angle, i.e., along a single streamline, which captures its dilution in three dimensions due to the growth of the surface area of the shell-segment as the shock expands.

We set ΔP = 0 to account for the fact that the SBs generally become radiative, and quickly enter a rapidly cooling wind phase (e.g., Kim & Ostriker 2015; Oku et al. 2022). While the expansion of such rapidly cooling winds is still formally energy-driven, the coupling between the hot interior and the shell leads to dynamics that are equivalent to those of a momentum-driven wind, but with a slightly boosted momentum injection rate in comparison to that at the source (Lancaster et al. 2024). We account for this boost, as well as losses, by means of the energy efficiency factor εw.

We model CRs as a non-thermal fluid with an adiabatic index of γCR = 4/3, which is advected with the outflowing gas (Girichidis et al. 2024), assuming a uniform pressure distribution immediately behind the shock. The CR pressure then evolves as

where εw, CR = ζstr, CR ζcal, CR ∼ 0.01 is an efficiency factor for the CR energy. This parametrizes the combined effects of energy losses due to CR streaming, ζstr, CR ∼ 0.1 (Chan et al. 2019; Hopkins et al. 2022), which accounts for their enhancement by stronger magnetic fields near the galactic disk (Buck et al. 2020), and CR attenuation by hadronic collisions, characterized by ζcal, CR.

Galactic starbursts are often CR calorimeters, meaning that a substantial amount of the CR energy is lost to hadronic pp collisions within their ISM (Krumholz et al. 2020; Werhahn et al. 2023). The CR calorimetric fraction has been reported to vary between 0.8 and 0.99 in nearby starbursts (Krumholz et al. 2020). However, such strong calorimetry within the outflow itself would generally only arise before the outflow has cleared a path through the ISM of its host, i.e., the < 10Myr break-out timescale (see Appendix B) compared with the > 100 Myr duration of a wind-sustaining starburst (e.g., Di Matteo et al. 2008). A fiducial choice of ζcal, CR ∼ 0.1 is therefore conservative.

As the outflow reaches a steady state (i.e., over a timescale when the flow reaches its asymptotic limit at high altitudes), the mass it has swept up is given by

To analyze the properties of the outflow, we consider steady-state solutions with  in the limit where z = v∞t ≫ Hs, and where the mass of the shell is dominated by the swept-up mass, i.e.,

in the limit where z = v∞t ≫ Hs, and where the mass of the shell is dominated by the swept-up mass, i.e.,  . In this limit, we can rewrite eq. A.4 as

. In this limit, we can rewrite eq. A.4 as

When external CR pressure is absent (ΔPCR = PCR, in), this reduces to a quadratic form with a single positive solution:

where

and

In the absence of CRs, there are no outflow solutions when ℛSN ≤ ℛc. On the other hand, when CRs are present, outflow solutions are always possible. For weak sources with ℛSN ≪ ℛc, the outflow reaches very slow asymptotic speeds:

where εw, CR, −2 ≡ εw, CR/10−2 and

However, in the strong source limit where ℛSN ≫ ℛc and  , the outflow velocities are much higher, approaching:

, the outflow velocities are much higher, approaching:

Appendix B: Timescales

To assess the validity of the underlying assumptions of our model, we check that the timescales related to the shock break-out from the ISM and the time it takes to reach the steady state solution are short enough to have a negligible effect on the overall dynamics.

The time it takes for a continuously driven SB to become radiative and dissipate the majority of its thermal energy is on the order of the shell-formation timescale (Oku et al. 2022)

which is usually much shorter than the corresponding time it would take for an adiabatic blastwave to reach the galactic scale height and break out; on the order of

Thus, unless they are extremely powerful, the dynamics of starburst-driven SBs prior to shock break-out can be described by a momentum-driven wind solution z ∝ t1/2 and the time it takes for the shock to break out is longer due to the radiative losses; on the order of

Prior to shock break-out the dynamics of the shock are well described by the expressions for momentum-driven winds in uniform media (Oku et al. 2022; Lancaster et al. 2024) in which the losses are explicitly accounted for. We can thus set εw = 1 for these pre-break-out expressions. At the time of shock break-out the shock speed will have dropped dramatically to only about

and the shock is re-accelerated before it reaches its asymptotic speed. In the case of a weak CR-driven wind the acceleration after break-out is approximately  , leading to rapid acceleration up to the asymptotic speed Eq. A.13 within only

, leading to rapid acceleration up to the asymptotic speed Eq. A.13 within only

where we took the geometric average of the acceleration between  and

and  . In this time frame the outflow can already reach a few kpc above the disk. In the strong-source limit the acceleration after break-out is

. In this time frame the outflow can already reach a few kpc above the disk. In the strong-source limit the acceleration after break-out is  , which leads to a moderate, but still relatively fast acceleration to the asymptotic speed Eq. A.14, within

, which leads to a moderate, but still relatively fast acceleration to the asymptotic speed Eq. A.14, within

In this time frame the wind may have already expanded many 10s of kpcs into the halo, while stronger winds may reach their asymptotic speed closer to the galaxy.

These timescales may be compared to the typical duration of a starburst episode on the order of tstarburst ∼ 10 Myr (Rathjen et al. 2023), which suggests that starburst driven winds are established over the course of multiple short bursts, each lasting only a fraction of the lifetime of the wind. The SN rate ℛSN in our model thus represents the average over a series of distinct starbursts.

Appendix C: Model limitations and assumptions

Our model invokes a number of approximations and assumptions. While we consider our results to be qualitatively robust, future developments that relax these assumptions may provide more refined insights. Here, we assess the validity of our assumptions and approximations and discuss their potential impact on our results.

Density profile and gravitational field. The density profile in eq. (A.1) represents an isothermal, single-component atmosphere in vertical hydrostatic equilibrium, providing a reasonably accurate description near the mid-plane. However, the presence of molecular gas and a young stellar disk could create a deeper potential well, leading to a more compact density profile that may affect the early stages of shock breakout. Moreover, explicitly modeling the gravitational potential of different galaxy components (e.g., the bulge, disk and dark-matter halo) could modify flow properties (see Shimoda & Inutsuka 2022), and this can be affected by the detailed gas distribution throughout the galaxy and inner halo. However, the outflow properties at high altitudes (above ∼100 kpc) are unlikely to be significantly impacted if the overall gas surface density and wind loading remain unchanged.

Halo gas properties. In the halo, the multi-phase CGM contributes a diffuse gas background that exerts additional (ram) pressure, which can counteract outflow expansion (Shin et al. 2021). While the CGM is diffuse, it is expected to follow a shallow density profile that would slow the outflow’s expansion once the swept-up CGM mass becomes comparable to M∞. This occurs at a height of  , where

, where  is the number density of hydrogen in the CGM.

is the number density of hydrogen in the CGM.

Ejecta mass. For the asymptotic steady-state solution, we consider a limit where the outflow has traveled sufficiently far above the disk, yet is not old enough for its mass to be dominated by the ejecta. The timescale for the outflow to become ejecta-dominated is  , which is considerably longer than the lifetime of the starburst driving the outflow. We therefore consider our results to be robust against this approximation.

, which is considerably longer than the lifetime of the starburst driving the outflow. We therefore consider our results to be robust against this approximation.

Thin-shell and sector approximation. While the thin-shell approximation is well-suited for radiative blastwaves or those propagating through media with positive density gradients, it becomes increasingly crude in environments with steep negative density gradients. This is because the mass, energy, and momentum distributions behind the shock broaden significantly (see, e.g., Laumbach & Probstein 1969; Koo & McKee 1990). Despite the steep density gradient considered in this work, our model focuses on a radiative, momentum-driven wind, where the thin-shell approximation is expected to remain reasonably accurate. The sector approximation, on the other hand, is most reliable when the local shock surface remains relatively flat. This approximation can break down if adjacent streamlines begin to diverge significantly, for example, due to sudden deflections. However, since observed outflows generally exhibit large opening angles, this approximation is likely to have only a negligible impact on ourfindings.

Treatment of CRs. Our treatment of CRs involves a number of simplifications. While we do not explicitly account for CR cooling or interactions within the flow, this is well justified given the relevant timescales (see Appendix A.1), at least in the context of low mass galaxies. In more massive galaxies with denser gas, it becomes increasingly difficult for shocks driven by stellar feedback to break-out of the disk, where cooling losses do dominate, rendering CR-driven galactic outflows ineffective in such systems with halo masses above ≳ 1012 M⊙ (Jacob et al. 2018; Girichidis et al. 2024). However, future studies with more detailed CR propagation modeling may yield different quantitative results, particularly if a detailed CR transport model within the halo is included. Such models could alter the distribution of halo CRs (Recchia et al. 2021), and reveal the microphysical impacts of CRs on outflows, including re-acceleration processes and interactions with complex magnetic field structures at the outflow–halo interface (see, e.g., Hopkins et al. 2023). Additionally, our study does not consider the spectral evolution of CR particles, which could influence the coupling between CRs and the outflowing wind fluid, potentially modifying their driving efficiency and altering observable CR emission signatures. Future work incorporating these effects could provide a clearer understanding of how CRs shape the development of outflows in CR-rich galaxy halos.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Schematic of the structure of a starburst-driven outflow embedded in a galactic halo, propelled by thermal gas pressure and/or non-thermal CR pressure. The scale height of the warm ISM is indicated. All galaxies are embedded in a gravitational potential, g, which opposes the outflow. Superscripts + and − on quantities indicate whether each term contributes to or opposes the outflow, respectively. Left: In the absence of a substantial gas halo, outflowing gas is unconfined, allowing it to escape beyond the galaxy ecosystem against the galaxy’s gravitational potential. Center: As the galaxy builds up its stellar mass, feedback processes form a hot gas halo that suppresses the outflow, promoting baryonic recycling and enriching the CGM (see Ferrara et al. 2005; Shin et al. 2021). Right: When CRs are supplied to the halo, they accumulate over time, introducing a non-thermal halo component. Since non-thermal CR pressure gradients operate over larger length scales than thermal pressure gradients, an outflow erupting into the galaxy halo encounters distinct layers where thermally dominated and CR-dominated pressure gradients hinder its development. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Terminal outflow velocities as a function of star formation rate surface density for different choices of CR energy fractions, fCR, and energy loading factors, ηe. The model predictions are compared with data from Heckman et al. (2015), which show measured outflow velocities for a sample of nearby starburst galaxies with stellar masses in the range log10(M*/M⊙) ∈ [7.1 − 10.9]. Typical uncertainties are indicated in the top-left corner. The model with ηe ∼ 0.01 and fCR ∼ 0.1 provides a good match with the observed data. Models with higher energy loading values (ηe) generally predict outflow velocities in excess of the observations. The transition from slow outflows in weak starbursts to fast outflows in strong starbursts is best captured by models with fCR > 0. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.1. Characteristic timescales for a CR proton to undergo a hadronic interaction with ambient gas (pp interactions) or radiation (pγ interactions) shown for typical conditions in the galaxy interior (red lines) and halo (black lines). For the galaxy interior, we adopt a gas density of 1 cm−3 and stellar radiation fields consisting of a stellar component with T = 7100 K and an energy density of ∼0.7 eV cm−3, with a dust component at T = 60 K and an energy density of ∼0.3 eV cm−3. For halo conditions, we consider a reduced gas density of 10−3 cm−3, with radiation energy densities scaled down by a factor of 100. pγ losses with cosmological microwave background radiation at z = 0 are included for both galaxy interior and halo conditions, with photo-pair and photo-pion interactions occurring at the same rate in both environments. The Hubble timescale is shown in gray. Interaction timescales exceeding this (i.e., within the shaded pink region) practically do not occur. Hadronic pp and pγ interaction timescales are calculated following the approach of Owen et al. (2018), assuming that the invariant energy of an interaction is dominated by that supplied by the CR. For pp interactions, this uses the total inelastic cross-section parametrization of Kafexhiu et al. (2014). For pγ pion-production losses, the step-function approximation to the cross-section proposed by Dermer & Menon (2009) is adopted. Bethe-Heitler losses are treated using the simplified cross-section from the same reference, but with fitting parameters updated according to Owen et al. (2018), suitable for the energy range considered here. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.