| Issue |

A&A

Volume 701, September 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A291 | |

| Number of page(s) | 18 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554835 | |

| Published online | 26 September 2025 | |

Forming deuterated methanol in pre-stellar core conditions

1

Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik,

Gießenbachstraße 1,

85748

Garching bei München,

Germany

2

European Southern Observatory,

Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 2,

85748

Garching,

Germany

3

Astrochemistry Laboratory, Code 691, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center,

Greenbelt,

MD

20771,

USA

4

Department of Physics, Catholic University of America,

Washington,

DC

20064,

USA

5

Ural Federal University,

620002,

19 Mira street,

Yekaterinburg,

Russia

6

Departments of Astronomy & Chemistry, University of Virginia,

Charlottesville,

VA,

USA

★ Corresponding author: riedel@mpe.mpg.de

Received:

28

March

2025

Accepted:

4

August

2025

Context. The formation mechanisms for most complex organic molecules (COMs) are still debated. Either COMs form mostly on the surface of dust grains or mostly by reactions between simpler hydrogenation products upon their desorption into the gas phase. Methanol, the simplest of the O-bearing COMs, plays a key role in both scenarios.

Aims. Our aim is to improve the suitability of our models for the formation and deuteration of COMs in the extremely cold conditions of pre-stellar cores, where chemical reactions between heavier reactants on the surface of dust grains are hindered by the reactant’s immobility. Initially, we focused our efforts on CH3OH and its singly deuterated isotopologue CH2DOH.

Methods. We updated a gas-grain chemical code capable of deuterium chemistry by including various non-diffusive reaction mechanisms: Eley–Rideal reactions, photodissociation-induced reactions, and three-body reactions. Moreover, we added the reaction H2CO + CH3O → CH3OH + HCO to our chemical network, which was found to contribute significantly to methanol formation in both microscopic kinetic Monte Carlo simulations and laboratory experiments. We performed several 1D simulations of the pre-stellar core L1544, where we derived column density profiles for CH3OH and CH2DOH and compared our model results with more conventional modelling approaches and available gas-phase observations.

Results. We show that multiple models with different parameter sets provide column density profiles that are in reasonable agreement with the observed values. On the one hand, when applying a single collision reaction probability, either an increase in the reaction rate by the occurrence of diffusion by quantum tunneling or a lowered diffusion-to-binding energy ratio (Ed/Eb = 0.2) for thermal diffusion is needed to match the observed methanol levels. On the other hand, when applying reaction-diffusion competition, reactions proceeding by thermal diffusion with a conservative diffusion-to-binding energy ratio (Ed/Eb = 0.55) are sufficient to reach observed column densities. We find that, in contrast to other COMs, the introduced non-diffusive mechanisms play only a secondary role in the formation and deuteration of methanol. Additionally, we find only a negligible contribution from H2CO + CH3O → CH3OH + HCO.

Key words: stars: formation / ISM: abundances / ISM: clouds / ISM: molecules

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open Access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1 Introduction

Currently, over 330 molecules1 have been discovered in the interstellar medium, and their numbers are rapidly growing as observers make use of today’s outstanding telescope facilities in the radio, millimetre, and far-infrared regime. Around 47% of the detected molecules are considered to be large, consisting of six atoms or more. Interestingly, all of these larger molecules contain at least one carbon atom, which is why they are commonly called complex organic molecules (COMs; Herbst & van Dishoeck 2009) or interstellar COMs (iCOMs; Ceccarelli et al. 2017). The apparent dominance of carbon chemistry, both in the interstellar medium and on Earth, together with other chemical markers (e.g. D/H ratios), strongly suggest that the precursors of the building blocks of organic life on our planet were formed – and possibly conserved to some extent - in the earliest stages of star formation (Caselli & Ceccarelli 2012).

The consensus is that methanol is formed almost exclusively on the surface of dust grains by successive H-addition reactions to CO (e.g. Watanabe & Kouchi 2002; Fuchs et al. 2009; Santos et al. 2022). The formation scenarios of most other COMs, however, are still under debate. The present and ongoing discussion concerns the degree to which either gas-phase or grain-surface and ice mechanisms dominate the production of COMs in general. In the former case, this would occur as common grain mantle components (e.g. H2O, CO2, NH3, CH4, and CH3OH; Boogert et al. 2015), which are formed mostly by the hydrogenation f atoms or simple molecules, are released into the gas phase by thermal and nonthermal desorption processes and then further processed by gas-phase reactions to form more complex molecules. In the case in which grain-surface chemistry is dominant, production could occur through diffusive or non-diffusive reactions, or through energetic processing (e.g. UV photolysis). The products would then be desorbed into the gas via thermal or nonthermal means, depending on the environment. Although these two possibilities are sometimes presented as either-or options for all COMs (e.g. Ceccarelli et al. 2023), it is apparent from astrochemical models that certain COMs have highly effective gas-phase production mechanisms, while others do not, with many still unexplored. Understanding the early formation mechanisms of methanol is extremely relevant in both formation scenarios, as it plays an important role in both of them. In a scenario where grain surface mechanisms dominate, COMs are usually assumed to form by radical-radical or radical-neutral reactions in which HCO, CH3O, and CH2OH, as intermediate products of the methanol formation route, play a fundamental role. In contrast, in the gas-dominated scenario, methanol is desorbed into the gas phase subsequent to its formation on the grain surface and acts as an important precursor for larger COMs.

In the case of grain surface formation, COMs were formerly believed to form only in a lukewarm temperature regime (30–100 K) during a gradual warm-up phase of the molecular clouds. In this warm-up scenario, grain surface radicals are first produced by the irradiation of UV photons and cosmic rays. Once the grain temperature increases to about 30 K, the radicals become more mobile, diffuse over the grain surface, meet each other, and react (Garrod & Herbst 2006; Garrod et al. 2008). However, detections of multiple COMs in even earlier, colder (< 15 K) stages of star formation (e.g. Öberg et al. 2010; Bacmann et al. 2012; Cernicharo et al. 2012; Jiménez-Serra et al. 2016 ) bring doubt regarding the warm-up scenario as the sole formation process. Alternatively, or in addition to the warm-up scenario, the introduction of non-diffusive reaction mechanisms has been proposed in various works. Hereby, the term non-diffusive chemistry consists of various reaction mechanisms, which have in common that they do not require the diffusion of species heavier than commonly present atoms (e.g. H, O, C, and N). Instead, they rely on the (small) probability that both reaction partners are formed in close proximity to each other. At the low temperatures of pre-stellar cores (6 K ≤ Tgrain ≤ 15 K), non-diffusive reaction mechanisms could be the most relevant process for the formation of COMs, as only the lightest species are expected to diffuse over the grain surface, likely excluding a diffusion-driven COM formation scenario for these conditions. Garrod & Pauly (2011) introduced a single three-body reaction, very similar to the one used in the present work, between the reactants H, O, and CO to explain the formation of CO2 on the surface of dust grains under dark-cloud conditions. Ruaud et al. (2015) showed that Eley-Rideal reactions in combination with a complex induced reaction mechanism of gas phase carbon atoms with the grain surface are able to increase the formation rate of multiple O-bearing COMs. Chang & Herbst (2016) added a chain-reaction mechanism to their unified microscopic-macroscopic Monte Carlo code. Conceptually, their mechanism is very similar to the three-body reactions used in this work; however, it is not straightforwardly applicable to a rate-equation based code. Similar to Garrod & Pauly (2011), Dulieu et al. (2019) introduced a single three-body reaction, between H2NO and H2CO to reproduce the formation of formamide (NH2CHO) in co-deposition experiments of H, NO, and H2CO at 10 K. Their approach tracks two types of H2NO molecules: the ones that are formed next to an active H2CO molecule and the ones that are formed next to other molecules. Although different from the one used in this work, their treatment should produce the same results. Shingledecker et al. (2019) showed that radiolysis can efficiently form radicals and other reactive species in the grain’s bulk, which are then able to react non-diffusively with neighbouring molecules and drive a rich chemistry there. The most extensive introduction and the one adopted in the present work, however, is presented in Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022).

The importance of reactions between heavy reaction partners under dark cloud conditions is supported by several co-deposition experiments of simple and abundant molecules. In experiments with CO molecules and H atoms at 13 K, Fedoseev et al. (2015) found the formation of glycoalde-hyde (HC(O)CH2OH) and ethylene glycol (H2C(OH)CH2OH) in addition to formaldehyde (H2CO) and methanol (CH3OH) formation. The result was confirmed and extended to methyl formate (HC(O)OCH3) formation in CO+H+H2CO and CO+H+CH3OH co-deposition experiments at 15 K by Chuang et al. (2016). There, H2CO and CH3OH were only deposited simultaneously to artificially enhance their abundances to provide sufficiently high methyl formate yields to meet the detection sensitivity limits of the experimental setup. In a similar manner, Fedoseev et al. (2017) detected glycerol (HOCH2CH(OH)CH2OH and tentatively detected glyceraldehyde (HOCH2CH(OH)CHO) upon co-deposition of CO+H+HOCH2 CHO at 13 K. Qasim et al. (2019) showed that the formation of propanal (H3CCH2CHO) in co-deposition of C2H2+CO+H at 10 K and its subsequent hydrogenation to 1-propanol (CH3CH2CH2OH) is possible. Moreover, the formation of the simplest amino acid, glycine (NH2CH2COOH) has been shown in co-deposition of CO+NH2CH3+O2+H at 13 K by Ioppolo et al. (2021). Their proposed formation routes are supported by astrochemical models, performed with MAGICKAL (Garrod 2013), including non-diffusive reaction mechanisms. Fedoseev et al. (2022) find that ketene (CH2CO) is formed in co-deposition of H2O + C + CO + H at 10 K with possible further hydrogenation steps leading to acetaldehyde (CH3CHO) and ethanol (CH3CH2OH) formation. However, the most relevant finding for the present work are the co-deposition experiments of H2CO+H performed in a temperature range from 10 K to 16 K by Santos et al. (2022). The authors confirmed the predominant formation of methanol by the radical-molecule reaction H2CO + CH3O → CH3OH + HCO over the simple H-addition reaction, which was formerly suggested by microscopic kinetic Monte Carlo simulations (Simons et al. 2020. What all the proposed formation pathways have in common is that they involve at least one reaction step where larger surface radicals or molecules react with one another, possibly preceded and-or followed by multiple hydrogenation steps. Before, such reaction steps were deemed inefficient, as both reaction partners are considered to be immobile on the surface of dust grains in the extremely cold conditions of pre-stellar cores. Their inclusion makes invoking non-diffusive reaction mechanisms into astro-chemical models necessary. Otherwise, the efficiency of the proposed reactions could be severely underestimated. Interestingly, the found pathways do not require that the grain mantle products are energetically processed by UV photons or cosmic rays; most of the radicals are instead formed by simple surface hydrogenation addition and abstraction reactions.

The inclusion of non-diffusive reaction mechanisms into rate-equation based astrochemical codes is still under scrutiny. While microscopic Monte Carlo codes account for the exact position of each molecule at all times and can therefore accurately determine the amount of respective reactants sitting in close proximity to each other, rate-equation based codes compute only the average formation and destruction rates of the molecules included in their chemical network. Unfortunately, this large amount of information comes with a high computational cost, and hence, studies conducted with a microscopic Monte Carlo code usually use chemical networks including only a small number of species and reactions. To obtain a broad overview over the chemistry occurring in any interstellar region, rate-equation based codes are typically better suited accounting for the multitude of different species and reactions present. In the formulation of non-diffusive chemistry proposed by Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022), the probability of the second reactant being close by when the first one forms is simply estimated to be Ni/NS. Here, Ni is the average number of atoms or molecules of species A or B on the grains, and NS is the total number of binding sites on a grain. While this recipe is simple to integrate into a rate-equation based code, it can lead to an overestimation of reactants being formed close to each other in the case only very small numbers of the respective reactants are present on the grain. Additionally, rate-equation based codes are unable to account for clustering of surface species, which could potentially make certain non-diffusive reactions more efficient than would otherwise be the case for a random distribution of reactants on the grain surface.

Here, we present the inclusion of non-diffusive reaction mechanisms following the formulation by Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022) into an astrochemical code capable of simulating deuterium chemistry (pyRate; Sipilä et al. 2015a, 2019b). The addition of non-diffusive chemistry to pyRate provides valuable additional information about the deuteration of COMs that could formerly not be obtained. We applied the added reaction mechanisms to methanol, the simplest of the O-bearing COMs, as it is a key species in the two major formation scenarios for COMs discussed in the current literature. To connect to our previous works (Vasyunin et al. 2017; Chacón-Tanarro et al. 2019; Riedel et al. 2023), all the necessary modifications were performed in a step-by-step manner to enable the reader to separately evaluate the effects of each step. In a subsequent work, we will extend our chemical network to larger species and investigate the formation and deuteration of other COMs.

This paper is structured as follows: in Section 2 we describe the physical model and the updated chemical model in detail. In Section 3 we add various non-diffusive reaction mechanisms to the base model individually and in combination with each other. We discuss their importance for the formation and deuteration of methanol and compare them to more conventional modelling approaches and the observationally obtained column density and deuterium fraction profiles from Chacón-Tanarro et al. (2019). Section 4 discusses additional modifications to the chosen chemical and physical parameters. Section 5 presents our conclusions. Appendices A and B provide more detailed information for some minor intermediate modification steps.

2 Methods

2.1 Introducing non-diffusive reaction mechanisms

PyRate was updated to include the non-diffusive mechanisms presented in Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022). In general, the present work follows their formulation closely, and we refer to these works for an extensive explanation of the adopted mechanisms and their respective formulation. However, for some of our purposes, namely to ensure comparability to our previous work (Riedel et al. 2023), it proved necessary to modify some equations slightly. Therefore, we lay out very briefly relevant equations below to explain these minor modifications. In Section 3.2, following the comparison to previous results, we switch to the original formulation of Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022) and use it for the remainder of the paper to ensure comparability to the literature.

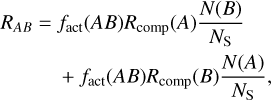

According to the standard formulation, as detailed in Hasegawa et al. (1992), the reaction rate RAB of reactants A and B in chemical reactions proceeding diffusively, is given by the following expression:

![$\matrix{ {{R_{AB}} = {f_{{\rm{act}}}}\left( {AB} \right)\left[ {{k_{{\rm{hop}}}}\left( A \right)N\left( A \right)} \right]{{N\left( B \right)} \over {{N_{\rm{S}}}}}} \cr { + {f_{{\rm{act}}}}\left( {AB} \right)\left[ {{k_{{\rm{hop}}}}\left( B \right)N\left( B \right)} \right]{{N\left( A \right)} \over {{N_{\rm{S}}}}},} \cr } $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa54835-25/aa54835-25-eq1.png) (1)

(1)

where khop(A) or khop(B) are the rates of thermal hopping (occasionally modified to account for diffusion by quantum tunneling) of molecule A or B, respectively, N(A) or N(B) the abundance of species A or B on the grain (here: average number of molecules on individual grain) and NS total number of binding sites on the grain. The quantity ƒact denotes the efficiency of a chemical reaction and assumes a value between 0 and 1.

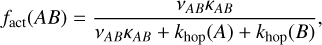

Reaction rates RAB for non-diffusive reactions, as detailed in Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022), follow a similar structure as Eq. (1):

(2)

(2)

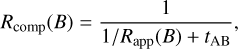

where the diffusion rate [khop(A)N(A)] of reactant A or the diffusion rate [khop(B)N(B)] of reactant B is replaced by the completion rate Rcomp(A) or Rcomp(B) that describe the rate of ‘appearance’ of reactant A and subsequent reaction with reactant B (or vice versa). The completion rates are derived by Eqs. (3) and (4):

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

where Rapp(A) and Rapp(B) are the appearance rates, that depend on the specific non-diffusive mechanism used, and tAB is the average lifetime of both reaction partners staying in a state in which they are ready to react.

Non-diffusive mechanisms are always allowed to act on the entire chemical network and in addition to the well-established diffusive reactions. The added mechanisms include the Eley–Rideal mechanism, photodissociation-induced mechanisms and three-body reactions. Eley–Rideal reactions are reactions in which a molecule from the gas phase adsorbs onto the grain surface and immediately finds a reaction partner in the vicinity of its adsorption spot. The appearance rate for a reactant is simply equal to the adsorption rate of this species. Photodissociation-induced reactions are initiated by a photon dissociating a larger molecule on the dust grain surface into two fragments, followed by a reaction of one of those fragments with another surface molecule in close proximity. The species appearance rate is calculated as the sum of photodissociation rates producing this species. Here, we adopt the description in Jin & Garrod (2020) (or the PDI version in Garrod et al. 2022), as the proposed refinement that considers that unsuccessful immobile photo-products recombine immediately is not of importance for surface species, since they can diffuse away from their production site before they would recombine again. In three-body reactions, a molecule is initially formed either diffusively, in a reaction with at least one mobile reaction partner (e.g. H), or via the above described non-diffusive reaction mechanisms. Subsequently, the newly formed reaction product can then spontaneously react with another adjacent molecule. Here, the appearance rate is the sum of the reaction rates of all diffusive reactions producing this species. In case they are switched on, the summed reaction rates of Eley–Rideal and photodissociation-induced reactions are also added to the appearance rate. Additionally, the three-body reaction mechanism has two variations. It is possible to perform several successive rounds of three-body reactions. While the first round can be initiated by diffusive reactions, and possibly Eley-Rideal and photodissociation-induced reactions, the following rounds are initiated by the respective preceding round of three-body reactions. The cost of running multiple rounds of three-body reactions with a chemical network comprising 75 000 reactions is extremely large and the effect expected to diminish with each round, which is why we limit ourselves to run models with two rounds of three-body reactions. Another option, three-body reactions with excited formation, is to assume that the reaction enthalpy released by the initiating reaction can (partially) help to overcome the activation-energy barrier of the follow-up reaction. This mechanism is only sensible in combination with the basic three-body reactions.

The above described non-diffusive reaction mechanisms can, in principle, be applied in arbitrary combination with each other. However, as running every possible combination would result in an unreasonable amount of models that also not necessarily provide more insights, we restrict ourselves to six models, involving non-diffusive chemistry. We perform a model run, where Eley–Rideal reactions (ND1/ND7), photodissociation-induced reactions (ND2/ND8) and three-body reactions (ND3/ND9) each are enabled separately. Moreover, we test a model with two rounds of three-body reactions (ND4/ND10) and a model where three-body reactions with excited formation are enabled alongside the basic version of three-body reactions (ND5/ND11). At last, we also run a model, where we combine Eley–Rideal, photodissociation-induced and three-body reactions (ND6/ND12), but none of the variations.

2.2 Chemical model

The chemical evolution of molecular abundances is calculated with the gas-grain astrochemical code pyRate, capable of simulating deuterium chemistry and described in more detail in Sipilä et al. (2015a, 2019b). The overall chemical network is based on the 2014 public release of the Kinetic Database for Astro-chemistry (KIDA) gas-phase network (kida.uva.2014, Wakelam et al. 2015). Respective reactions were cloned to include deuterium chemistry for molecules with up to seven atoms and spin-state chemistry for H2,  , and

, and  , as well as multiply pro-tonated species involved in the water and ammonia formation networks and their respective deuterated isotopologues. More details can be found in Sipilä et al. (2015a,b) and Sipilä et al. (2019b). In total the network includes a total of ≈75000 gas-phase and grain surface reactions, making it substantially larger than commonly used chemical networks that do not treat the chemistry of isotopologues explicitly. The methanol formation network is the same as presented in detail in Riedel et al. (2023). If not otherwise indicated, a network without abstraction reactions is adopted. However, in Section 3.3, the experimentally verified (Santos et al. 2022) methanol formation pathway H2CO + CH3O → CH3OH + HCO is added to the network. Moreover, in Section 4.2, we also present and discuss selected models including the abstraction scheme proposed by Hidaka et al. (2009).

, as well as multiply pro-tonated species involved in the water and ammonia formation networks and their respective deuterated isotopologues. More details can be found in Sipilä et al. (2015a,b) and Sipilä et al. (2019b). In total the network includes a total of ≈75000 gas-phase and grain surface reactions, making it substantially larger than commonly used chemical networks that do not treat the chemistry of isotopologues explicitly. The methanol formation network is the same as presented in detail in Riedel et al. (2023). If not otherwise indicated, a network without abstraction reactions is adopted. However, in Section 3.3, the experimentally verified (Santos et al. 2022) methanol formation pathway H2CO + CH3O → CH3OH + HCO is added to the network. Moreover, in Section 4.2, we also present and discuss selected models including the abstraction scheme proposed by Hidaka et al. (2009).

Surface reactions are allowed to proceed through the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism relying purely on thermal diffusion. Diffusion by quantum tunneling of hydrogen and deuterium atoms is not enabled in most models. We show, however, some models including both types of diffusion for the purpose of comparison to previous works (Vasyunin et al. 2017; Chacón-Tanarro et al. 2019; Riedel et al. 2023) in Section 3.1. The diffusion-to-binding energy Ed/Eb is set to 0.55, a value suggested for atoms by Minissale et al. (2016a) based on their measurements of diffusion and desorption energies of O and N atoms.

Dust grains are assumed to be spherical, with a radius of 0.1 µm and a surface site density of 1.5 × 1015 cm−2. We employed a three-phase grain model, including a gas phase, a chemically active surface phase and an inert mantle phase. In contrast to Jin & Garrod (2020), diffusive and non-diffusive mechanisms are carried out solely on the surface of the dust grains. Chemical reactions or any form of bulk diffusion is not included. The impact of bulk diffusion and reactions is probably small in the physical conditions of pre-stellar cores, where the grains undergo net adsorption rather than net desorption and as long as no invasive desorption mechanisms, that partially (or entirely) destroy the grain mantle, are applied. It can, however, become important if one considers the effect of cosmic-ray-driven radiation chemistry in combination with non-diffusive bulk reactions as was done in the works by Shingledecker et al. (2019), Shingledecker et al. (2020). This is beyond the scope of the present paper.

Initially, we adopted atomic initial abundances (see Table 1) taken from Semenov et al. (2010), as they were used for previous works (Chacón-Tanarro et al. 2019; Riedel et al. 2023). This choice is revisited in Section 4.3.

Besides thermal desorption, pyRate contains several non-thermal desorption mechanisms. In this work, we only apply cosmic-ray induced desorption and reactive desorption as non-thermal desorption mechanisms, since those can efficiently desorb methanol from the grain surface with reactive desorption presumed to be the dominant one. Photo-desorption of methanol has been shown experimentally to have negligible impact on the release of methanol from the grain surface (Bertin et al. 2016; Cruz-Diaz et al. 2016). PyRate contains two different options for the treatment of reactive desorption. The first option is a basic mechanism where the reaction products desorb with an efficiency of a specified, but constant value. The second option derives an individual reactive desorption efficiency for every product species that depends on the reaction enthalpy and type of underlying surface Minissale et al. (2016b) and was previously tested in Riedel et al. (2023). Most presented models apply the first option with an efficiency of 1%, as this provides a better comparability to the literature. However in Section 4.2, we also present the effects of the experiment-based reactive desorption mechanism for a small selection of models.

During the test phase, we found that when using the Eley–Rideal mechanism, the code will not converge to a solution, unless there is some method in place to get rid of an unphysical buildup of H2 on the surface of the dust grains. In Section 4.1, we test various options to lower the H2 coverage, including scaling the binding energies of H2 and its isotopologues by a factor of 0.1 and the modified binding energy treatment presented in Garrod & Pauly (2011) applied to all species or solely to H, H2 and its isotopologues. The overall effects on the column densities of CH3OH are small, which is why we have used the simple scaling option on all models presented in the main body of the paper.

Many chemical reactions both in the gas phase and on the surface of dust grains are exothermic but still require the reactants to overcome activation-energy barriers to react with each other. The formation scheme of methanol comprises at least two hydrogenation steps possessing considerable barriers (CO → HCO; EA = 1.76 × 103 K, H2CO → CH3O/CH2OH; 2.00 × 103 K/5.16 × 103 K). However, the extremely cold environments of pre-stellar cores pose a significant obstacle for those reactions to proceed, as the reactants typically have only very low energies. Hence, the details of calculating the efficiency of reactions with activation-energy barriers are crucial for the amount of methanol (and other COMs) produced.

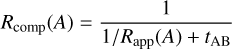

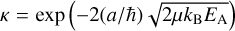

In previous models (see Chacón-Tanarro et al. 2019; Riedel et al. 2023), a single collision reaction probability (hereafter: SC), which was proposed in Hasegawa et al. (1992), was applied. It derives the probability κ for the reaction to happen upon encounter of the reactants as either a Boltzmann factor, κ = exp(−EA/Td), where EA is the activation energy of the reaction and Td the dust temperature, or a tunneling probability,  , where a is the thickness of a rect-angular barrier and µ the reduced mass. In Riedel et al. 2023 and the present work, reactive tunneling with a barrier thickness of 1 Å is used.

, where a is the thickness of a rect-angular barrier and µ the reduced mass. In Riedel et al. 2023 and the present work, reactive tunneling with a barrier thickness of 1 Å is used.

However, the formulation of non-diffusive mechanisms proposed in Jin & Garrod (2020) assumes that rates for reactions containing an activation-energy barrier are calculated using reaction probabilities derived from the reaction-diffusion competition (RDC) model proposed by Chang et al. (2007) (see also Garrod & Pauly 2011). It considers that the reaction partners are confined in the same binding site until one of them diffuses away again. Therefore, they have multiple opportunities to react with each other as opposed to just one in the SC model. In the RDC model, a reaction with an activation-energy barrier is typically significantly more likely to happen as compared to the SC model, as the reactants can undergo multiple attempts to react. Therefore, reactants have to meet less frequently to produce the same amount of successful reactions. In recent years, many modellers adopted the RDC model into their chemical models, as it can provide higher gas phase abundances without assuming a highly efficient diffusion process on the surface or an unlikely high desorption rate.

First, in Section 3.1, to present a consistent approach for both diffusive and non-diffusive reactions and to be fully able to compare the effects of non-diffusive chemistry to the previous models, we modified the equations presented in Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022) accordingly, which can be simply done by setting ƒact to κ. We, also, removed the tAB-term from Eqs. (3) and (4), as the SC model assumes that the reaction either happens on first encounter of the reactants or not at all. In Section 3.2, we switch from using the SC model to using the RDC model for the remainder of the paper. For that, the efficiency factor ƒact is adjusted to be

(5)

(5)

where κAB is, as described above, either a Boltzmann factor or a tunneling probability. khop(A) and khop(B) are the rates of thermal hopping of species A or B, respectively. νAB denotes the frequency of collision of both reactants, which is here taken to be the larger of the characteristic frequencies of the reactants derived by the respective equation that is presented in Hasegawa et al. (1992).

Initial chemical abundances with respect to nH.

2.3 Physical model

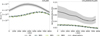

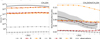

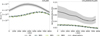

We present a set of static models using a one dimensional physical model (see Figure 1) for H2 density, gas temperature Tgas, dust temperature Td and visual extinction AV, which was derived from the one presented in Keto & Caselli (2010), with a more detailed description in Sipilä et al. (2019a). The chemical evolution is solved separately for 35 concentric shells spanning the entire core radius of 0.32 pc, resulting in spherical symmetric spatio-temporal evolution of molecular abundances.

The column density distribution is calculated by an integration along the line of sight for different impact factors and is subsequently convolved with a 30″ Gaussian beam to be comparable to the observations by Chacón-Tanarro et al. (2019).

3 Results

In the following, various modifications are introduced in a step-by-step manner to make it possible to follow their effects separately. All presented models are listed in the order of their appearance in Table 2. Modified physical and chemical parameters are indicated as well.

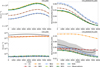

3.1 Applying a single collision model

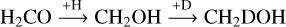

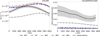

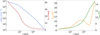

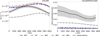

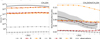

The upper panel of Figure 2 presents the column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right) of various models including non-diffusive reaction mechanisms at the best-fit time of t = 3.0 × 105 yr. The lower panel sets these results in comparison to previous results (Riedel et al. 2023) and the available gas phase observations by Chacón-Tanarro et al. (2019). The single-dish observations, carried out with the Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique (IRAM) 30 m telescope, show that CH3OH peaks in an asymmetric ring (see also Bizzocchi et al. 2014; Vastel et al. 2014; Spezzano et al. 2016). The position of strongest emission (methanol peak) is located in the northeastern part of the ring offset from the position of the dust peak. The best-fit time is taken to be the time-step, where the χ2 value of the observed central column density versus the corresponding value in the base model for H2CO and CH3OH (and their observed deuterated isotopologues) are minimised.

A purely diffusive model with a diffusion-to-binding energy ratio of Ed/Eb of 0.55 (slow thermal diffusion; model D1) is always shown as a reference. We find that applying the non-diffusive mechanisms as proposed by Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022) and modified to be consistent with the SC model as detailed above, is only adding minor contributions to the gas phase methanol reservoir, independent of the respective mechanism. While the largest impact on the CH3OH and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles is seen when adding three-body reactions (model ND3), a further addition of a second round of three-body reactions (ND4) or three-body reactions with excited formation (model ND5) is not increasing the methanol yield much more. Also, Eley–Rideal reactions (model ND1) only cause a slight increase in methanol production.

Photodissociation-induced reactions (model ND2) have a negligible impact on the methanol reservoir. The increase for CH3OH is typically larger than for its deuterated counterpart CH2DOH, consequently reducing the N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) slightly. Most of the increase in methanol can be accredited to opening up an additional pathway for simple H-addition reactions. This is particularly the case for the ND1 model, where the Eley–Rideal mechanism contributes up to 44% at the dust peak (densest part) and 13% at the methanol peak. Reactions between heavier reactants (e.g. OH + CH3 → CH3OH or OH + CH2D→CH2DOH), which occur predominantly via non-diffusive reaction mechanisms, start to play a role as well and are even the dominant formation route on occasion. Especially for the formation of the methanol precursors – CH3O and CH2OH – the reactions O + CH3 → CH3O and OH+CH2 → CH2OH dominate the formation (for CH3O) or are comparable to the hydrogenation reaction (for CH2OH). These formation routes are likely favoured as they do not possess an activation-energy barrier, while the hydrogenation reactions H+H2CO→CH3O (EA = 2 × 103 K) and H+H2CO→CH2OH (EA = 5.16 × 103 K) have a substantial one. For Eley–Rideal reactions, we typically find an increased importance to the innermost part of the core, where the higher gas phase abundances result in larger adsorption rates. The photodissociation-induced and three-body reactions, however, show higher contributions at the position of the methanol peak.

Riedel et al. (2023), in agreement with Vasyunin et al. (2017) and Chacón-Tanarro et al. (2019), conclude that an increase of the diffusion rates of hydrogen and deuterium atoms over the grain is necessary to explain the observations. They tested two available options: either allowing the diffusion to take place both by a slow thermal hopping process (Ed/Eb = 0.55) and additional quantum tunneling of hydrogen and deuterium atoms through a rectangular barrier with a width of 1 Å or by a fast thermal hopping process (Ed/Eb = 0.2). Additionally, a reference model with solely a slow thermal hopping process (Ed/Eb = 0.55) was performed. Both options with increased diffusion rates are able to increase the methanol column densities by several orders of magnitude compared to the reference model, but they still underproduce the observed methanol column densities by roughly an order of magnitude. However, most models presented in Vasyunin et al. (2017), Chacón-Tanarro et al. (2019), and Riedel et al. (2023) apply an experiment-based formulation of reactive desorption proposed by Minissale et al. (2016b), which derives an individual reactive desorption efficiency for every product species in a chemical reaction, depending on the reaction enthalpy and type of underlying surface. Since this version of reactive desorption typically produces reactive desorption efficiencies much lower than 1% for heavier reaction products, this underproduction could potentially be caused by an underestimation of the desorption process. For a full comparison of the models using a form of increased diffusion rate with the models comprising non-diffusive reaction mechanisms presented here, we performed the former ones again, but with scaled H2 binding energies and a constant reactive desorption efficiency of 1% (see Appendices A and B for more details).

In the framework of the SC model, we conclude, when using solely a slow diffusion process (Ed/Eb = 0.55), the diffusion rate of hydrogen (and deuterium) atoms is not efficient enough. Applying the non-diffusive mechanisms is only adding a minor contribution to the gas phase methanol reservoir. Models increasing the diffusion rate, especially of hydrogen (and deuterium) atoms, tested in the previous works, are more successful in that regard and are able, when using a constant reactive desorption efficiency of 1%, to increase column densities to almost the observed order of magnitude and simultaneously produce a N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profile, which is well within the area of uncertainty of the observations.

However, available laboratory experiments (Hama et al. 2012 on an ASW surface, Kimura et al. 2018 on a CO surface) found that the diffusion of hydrogen (and deuterium) atoms at 10 K is not dominated by quantum tunneling but rather thermal hopping, as a significant isotope effect between hydrogen and deuterium atoms has not been observed. These results are also backed up by theoretical work (Senevirathne et al. 2017).

Also, measurements for diffusion energies Ed or more commonly diffusion-to-binding energy ratios Ed/Eb are quite sparse. They are found to be species-dependent with Ed/Eb = 0.2 (as used for the model with a fast thermal hopping process) being the lowest value debated in the literature (Furuya et al. 2022). However, these values were measured for CO and CH4 and not for H. Moreover, experiments (Watanabe et al. 2010; Hama et al. 2012) conclude that potential wells on the surface of the dust grain can be divided into groups according to their depth, with Hama et al. (2012) identifying at least three different ones. Most astrochemical codes are not able to model such complicated grain surface properties, with only a few exceptions (e.g. Grassi et al. 2020), but only use a uniform diffusion-to-binding energy ratio. Additionally, Jin & Garrod (2020) find that a low value for the diffusion-to-binding energy ratio (Ed/Eb = 0.35 in their case) causes a quicker hydrogenation of radicals, which shortens their lifetimes and consequently could make proposed surface formation pathways for COMs less efficient.

|

Fig. 1 Physical model first presented in Keto & Caselli (2010) and described in more detail in Sipilä et al. (2019a) providing static radial profiles of the H2 volume density, n(H2) (blue, logarithmic scale), the visual extinction, AV (red), Tgas (orange), and the dust temperature, Tdust (green). |

Overview of the various models investigated in this work.

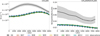

3.2 Applying a reaction-diffusion competition model

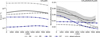

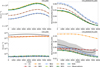

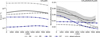

Figure 3 presents the column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right) of the diffusive model with a slow thermal hopping process (Ed/Eb = 0.55; D4) and various non-diffusive models (ND7-ND12), derived by assuming the RDC model. They are presented at the best-fit time of t = 3.0 × 105 yr. We find that the column densities of CH3OH and CH2DOH in model D4 are increased by several orders of magnitude compared to the respective model derived with the SC model (D1) due to the higher reaction probabilities of the reactions with activation-energy barriers (CO + H → HCO and CH2OH/CH3O + H → CH3OH). In fact, the CH3OH column density profile matches the observationally constrained profiles within a factor of around two, which is considered to be a good agreement for astrochemical models.

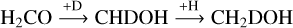

Interestingly, the N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) in model D4 is decreased by a factor of two to three compared to model D1. This decrease is caused by the change in the reaction probabilities for important formation pathways of CH2DOH when applying the RDC model. CH2DOH can be formed via three different pathways, starting from H2CO: (I) the hydrogenation of H2CO to CH2OH and its subsequent deuteration (see reaction (6)), (II) the deuteration of H2CO to CHDOH and its subsequent hydrogenation (see reaction (7)) and (III) the deuteration of H2CO to CH2DO and its subsequent hydrogenation (see reaction (8)). The CH2DOH formation from CH3O or CH2OD is excluded in the selected formation scheme.

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

When applying the SC model for the calculation of reaction probabilities for reactions with an activation-energy barrier, the hydrogenation reaction of H2CO will much more often result in the formation of the isomer CH3O as opposed to CH2OH due to its much higher activation-energy barrier (EA = 5.16 × 103 K versus EA = 2.00 × 103 K). Consequently CH3O is around 104x more abundant than CH2OH at the dust peak for the best-fit time. Without the inclusion of abstraction reactions (see also Section 4.2), a deuteration to CH2DOH is not possible any more once CH3O is formed. Since abstraction reactions are not considered in the first part of this work, the formation of CH2DOH mainly proceeds via reaction (8) as it has the lowest activation-energy barrier: EA = 1.28 × 103 K compared to EA = 5.16 × 103 K for the other two options. When applying the RDC model, however, the formation of CH2OH is not hindered significantly by the reaction’s high activation-energy barrier, as both reactants can undergo numerous attempts to react until one of them diffuses away again. In the extremely cold environment of pre-stellar cores the diffusion rates, even of hydrogen atoms, are much lower than the typical collision frequencies νAB. Consequently, the efficiency factor ƒact is much larger than in the SC model, resulting in an almost equal abundance of CH2OH and CH3O, while the abundance of CH2DO is decreased. Additionally, the D/H ratio on the grain surface in the RDC model is lower – around two order of magnitudes at the dust peak – than in the SC model. Combined with the lower D/H ratio and the slower hopping rate of D atoms, the higher amount of CH2OH decreases the relative CH2DOH formation as a hydrogenation reaction of CH2OH to form CH3OH is more likely than the respective deuteration reaction to form CH2DOH.

The impact of applying the various non-diffusive reaction mechanisms is again quite minor, which is in agreement with the results presented in Jin & Garrod (2020) (see Figure 11). In the models described above, methanol forms mainly by successive H/D-addition reactions to CO. Assuming a more efficient diffusion process is not necessary, when applying the RDC model, as the activation-energy barriers can be overcome more often due to the possibility of multiple reaction attempts, thereby reducing the need for a high amount of meeting events between the reactants. Reactions between two heavier reactants, such as CH3 + OH → CH3OH or similar reactions for precursors of methanol, do not contribute significantly.

|

Fig. 2 Column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right) of various combinations of the introduced non-diffusive mechanisms (model ND1-ND6; upper panel) and of diffusive models, including the diffusion of hydrogen (and deuterium) atoms by quantum tunneling (model D2; red) or a diffusion-to-binding energy ratio of Ed/Eb of 0.2 (fast thermal diffusion; model D3; orange; lower panel). A diffusive model with a diffusion-to-binding energy ratio of Ed/Eb of 0.55 (slow thermal diffusion; model D1; grey) is shown as a reference. All models are performed within the framework of the single collision model. The observed profiles, ranging from the dust peak into the direction of the methanol peak, presented first in Chacón-Tanarro et al. (2019), are depicted in black (errors as grey-shaded areas). The results are presented for the best-fit time of t = 3.0 × 105 yr. |

|

Fig. 3 Column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right) of various combinations of the introduced non-diffusive mechanisms (model ND7-ND12). A diffusive model with a diffusion-to-binding energy ratio of Ed/Eb of 0.55 (slow thermal diffusion; model D4; grey) is shown as a reference. All models are performed within the framework of the RDC model. The observed profiles are depicted in black (errors as grey-shaded areas). The results are presented for the best-fit time of t = 3 × 105 yr. |

3.3 Introducing H2CO + CH3O → CH3OH + HCO

Typically, the methanol formation pathway solely comprises successive H-addition reactions (or H-abstraction reactions) of atomic H to CO (e.g. Watanabe & Kouchi 2002; Fuchs et al. 2009). The hydrogen atom and its deuterated counterpart are both light enough to efficiently diffuse over the surface of the dust grain even at temperatures ranging around 10 K. If at least one of the reactants can diffuse efficiently, the contribution of non-diffusive reaction mechanisms to the formation yields of a reaction is generally small.

However, as Jin & Garrod (2020) showed, non-diffusive reaction mechanisms can have major contributions for reactions where both reactants are too heavy to efficiently diffuse over the surface. Several such reactions for the formation of methanol were proposed and tested in recent years. In their microscopic kinetic Monte Carlo (KMC) code, Simons et al. (2020) included several H-abstraction reactions between heavy intermediate products of the methanol formation pathway – HCO, H2CO and CH3O – with each other. While most of those reactions seem to produce only small methanol yields, Simons et al. (2020) surprisingly derived a contribution of 60–90%, depending on the physical conditions, for the reaction between H2CO and CH3O:

(9)

(9)

making it the dominant pathway for methanol formation over the simple H-addition reaction. This result was later confirmed experimentally by Santos et al. (2022). These authors performed several H2CO and H (or other combinations with D2CO and D) co-deposition experiments with H/H2CO ratios of either 10 or 30 in a temperature range between 10 K and 16 K. Similar to Simons et al. (2020), they find reaction (9) to be the dominant pathway with a contribution of at least 83% independent of the H/H2CO ratios and temperatures. Additionally, they conclude that forming methanol predominantly by reaction (9) would result in a decrease of the expected deuterium fractionation due to the kinetic isotope effect.

Although these findings would signify a major paradigm shift in the methanol formation scheme, most rate-equation codes, unlike microscopic Monte Carlo codes, are not equipped to properly test the efficiency of chemical reactions between two heavy reactants in low temperature regimes, as they do not account for the possibility that the reactants could be already in close proximity by chance. Finally, with the inclusion of non-diffusive reaction mechanisms, we are in a position to test the efficiency of reaction (9).

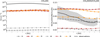

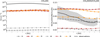

We adopted the branching ratio of 0.4 from Simons et al. (2020) for reaction (9). They also include the reaction channel H2CO+CH3O -> CH3OCH2O and a nonreactive channel to account for cases where the relative geometry of the reactants is not suitable for a reaction and the reactants are unable to reorient. In the present work, these other reaction channels are only implicitly accounted for by using a branching ratio unequal one. As reaction (9) is a radical-molecule reaction, it has an activation-energy barrier, which was estimated to be 2670 K by Álvarez-Barcia et al. (2018). Subsequently, reaction (9) is cloned to generate the reactions involving the various deuterated counterparts of the reactant and product species, resulting in 16 distinct versions. After adding the resulting reaction list to the chemical network used above, we run the diffusive model D4, resulting in model NM1, and the non-diffusive model including three-body reactions ND9, resulting in model NM2. The results are depicted in Figure 4. The former run is performed to verify that reaction (9) is inefficient when assuming purely diffusive reactions to occur, which can be indeed confirmed, as the column density profiles of both CH3OH and CH2DOH of model D4 and NM1 are almost identical. The latter run is performed, because non-diffusive reaction mechanisms had the largest contribution for models including three-body reactions in the previous models presented above. In contrast to the results of Simons et al. (2020) and Santos et al. (2022), we only find negligible contributions to the methanol formation yields from reaction (9), the majority of methanol is still formed by the addition of atomic hydrogen to CH3O or to CH2OH. Our explanation for these contradicting results is that the occurrence rate of either H2CO or CH3O being produced in close proximity to the other reactant is much smaller than a hydrogen atom diffusing to a binding site, where a CH3O molecule is sitting.

Apparently, this is not the case for the other two works by Simons et al. (2020) and Santos et al. (2022). Both groups of authors argue that reaction (9) might be the dominant route in their works due to a higher availability of H2CO and CH3O close to each other as opposed to hydrogen atoms on the grain’s surface. The chemical network in Simons et al. (2020) is limited to a hydrogen addition chain from CO to form methanol that was extended to also account for some recent experimental results on the formation of larger COMs (see Fedoseev et al. (2015) and Chuang et al. (2016)). Considering significantly more chemical reactions would be prohibitively computationally costly for a microscopic Monte Carlo code to perform. Naturally, the surface of their simulated dust grains only consists of the limited amount of species included in their chemical network, which could cause an overestimation of the occurrence rate of H2CO and CH3O molecules in close proximity to each other. Chemical codes that are based on the rate-equation approach are not that severely limited in the same sense. The simulations presented in this work include over 1000 species that are coupled by ≈75 000 reactions, resulting in a more realistic surface composition for interstellar dust grains. Similarly is a H/H2CO ratio of 30 or 10 used in the H2CO and H codeposition experiments by Santos et al. (2022) quite low as compared to the interstellar conditions, which could again result in an overestimation of the availability of H2CO close to CH3O molecules. In a more recent work by Jiménez-Serra et al. (2025), an adaption of the KMC code used in Simons et al. (2020) was employed to model the ice chemistry in the Chamaeleon I cloud. The chemical network used in this work also includes relevant species and reactions for the formation of CO2, CH4, NH3, and H2O, in addition to the network used in Simons et al. (2020). Interestingly, with this larger network Jiménez-Serra et al. (2025) derive only a contribution of ≈ 10% for reaction (9) and ≈90% for the hydrogenation of CH2OH and CH3O. However, since the physical conditions in these two works are not identical, the comparison of both results has to be regarded with some caution.

On the other hand, the specific properties of hydrogen diffusion, its dependency on ice structure, binding sites and - energies and how to include those into chemical codes is still under debate. An overestimation of the hydrogen diffusion rate on the surface could also result in an overestimation of the hydrogenation reaction’s efficiency and consequently lower the contribution of reaction (9).

|

Fig. 4 Column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right) of the diffusive model (D4) and a model including three-body reactions in addition to diffusive reactions (ND9). Both models use the methanol formation scheme presented in Riedel et al. (2023). Subsequently, they were redone with a modified chemical network, including the reaction H2CO + CH3O → CH3OH + HCO (NM1 and NM2). The observed profiles are depicted in black (errors as grey-shaded areas). |

4 Discussion

In addition to the introduction of non-diffusive reaction mechanisms, we explored various parameter modifications. They proved to be either necessary for the inclusion of non-diffusive chemistry or showed large effects on the CH3OH column density or N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) ratio.

4.1 Removing surface H2

The buildup of an unreasonable amount of H2 on the surface of dust grains in cold dense cores is a common issue for astrochemical codes. The H2 adsorption rate is large due to its high abundance in the gas phase, while desorption rates in the extremely cold and highly shielded environments are quite low. The H2 problem becomes more severe in three-phase models, as H2 molecules are incorporated into the mantle and locked in, resulting in a very high amount of mantle layers. Additionally, we found in this work that when applying the Eley–Rideal mechanism, the code will not converge to a solution, unless there is also a mechanism in place that removes the excess H2 from the surface of the dust grains.

The H2 excess is likely caused by the usage of binding energies appropriate for a pure water ice surface, while a realistic grain surface is composed of mostly H2O, CO, CO2, and ill constrained amounts of H2. Cuppen et al. (2009) proposed that the binding energy to an H2 surface could be around 10 times weaker than to other surface types. This motivated Garrod & Pauly (2011) to introduce effective binding Eb,eff and diffusion energies Ed,eff considering the fractional H2 surface coverage θ(H2):

![${E_{{\rm{b,eff}}}} = {E_{\rm{b}}}\left[ {1 - \theta \left( {{{\rm{H}}_2}} \right)} \right] + 0.1\,{E_{\rm{b}}}\theta \left( {{{\rm{H}}_2}} \right).$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/09/aa54835-25/aa54835-25-eq13.png) (10)

(10)

In Equation (10), the surface fraction θ(H2) that is covered by H2 contributes only 0.1 times as much to the effective desorption energy as the remaining surface fraction. The main effect of the method is a significant reduction of the amount of H2 on the surface and in the mantle of the dust grain. However, in Garrod & Pauly (2011), the method is applied to every grain species and consequently also causes a decrease of the binding energies of other species. The same is true for the diffusion energies Ed, as they are usually coupled to the binding energies by the diffusion-to-binding energy ratio Ed/Eb, which is typically due to the lack of sufficient experimental constraints, simply a single, constant value. Therefore, applying the above-described method causes also a decrease in the diffusion energies, increasing the grain species’ mobility.

Slightly more complex variations of this method have also been adopted in several other works. Taquet et al. (2014) considers not only H2 as a surface constituent with distinctly different binding energies from H2O, but also bare grain and pure ice; Furuya & Persson (2018) also considered CO, CO2 and CH3OH. Also, Garrod et al. (2022) propose a refinement of their original formulation, where they assume that every surface species is bound to four adjacent binding partners that collectively contribute to the binding energy. Each of the binding partners can either be an H2 molecule or not, introducing five types of binding sites of varying strength (1.0 for no H2 molecules; 0.1 for 4 H2 molecules). Considering this more intricate version mainly results in a further reduction of the H2 surface coverage and a lessened influence of the H2 content on the diffusion and binding energies of other species.

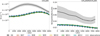

We tested different methods to remove the excess surface H2: scaling the binding energies of H2 and its isotopologues by a factor of 0.1 (model D4) and several versions of the original formulation by Garrod & Pauly (2011) applied to all species (model BE2); only to H2 and its deuterated isotopologues (model BE3); or only to H2, H, and their isotopologues (model BE4). Model BE3 and BE4 were tested, as heavier species should be able to penetrate through the single monolayer of H2 and bind as usual to the underlying ice, which is backed by laboratory experiments that do not find evidence for binding energy changes in experiments with H2 presence in the apparatus (priv. comm. with Gleb Fedoseev). All models presented in Section 4.1 apply only diffusive reaction mechanisms. Non-diffusive reaction mechanisms are not included, as we wanted to be able to compare the effects of the various H2 removal methods to a reference model (model BE1) without one. Figure 5 presents the column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right), while Figure 6 shows the surface coverage of the grain as a function of time (x-axis) and radius (y-axis). In general, the CH3OH column densities and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) of the modified models (D4 and BE2-BE4) differ only by a factor of around two or less when compared to the reference model (BE1). The largest difference to the reference model is seen when using scaled H2-binding energies (model D4), which is likely due to the fact that it represents the most extreme H2 removal method. Its application removes the surface H2 almost completely, decreases the CH3OH column density by approximately a factor of two and increases the N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) by the same amount. It is noteworthy, that we partially see the opposite trend when this method is applied in the context of the single collision model (see Appendix A). The other H2 removal methods (models BE2-BE4) produce CH3OH column densities and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) ratios that are closer to the reference model and also each other. For model BE2, where the Garrod & Pauly (2011) method is applied to all grain species, are the CH3OH column densities slightly higher than in the reference model, while for model BE3 and BE4 the difference to the reference model is negligible. Models BE2-BE4 show a similar level of H2 removal, with the H2 coverage being altered from 99.9% to 56% for the best-fit time of t = 3.0 × 105 yr at the position of the dust peak. Interestingly, the N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) ratio of model BE1 and model BE2-BE4 is lower than that of model D4 with only slight differences between the former models. Overall, Model BE3, where the Garrod & Pauly (2011) method is applied to only H2 and its isotopologues, shows the smallest difference to the reference model. It is, however, difficult to decide which method is the closest to a realistic description of the grain surface, as we currently still lack good constraints on the amount of surface H2 in pre-stellar cores. A removal of the excess surface H2 is mainly necessary to be able to run the Eley-Rideal mechanism, as otherwise the code will not converge to a solution. In principle, all tested mechanisms are able to remove this convergence problem, but the method of scaling the H2-binding energies (model D4) shows the lowest computative cost and the least issues with convergence. Therefore, we adopted it for the majority of this work.

|

Fig. 5 Column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right) of various diffusive models, that we used to test different approaches to prohibit an unphysical buildup of H2 on the surface of dust grains. A reference model (BE1) without a H2 removal method is shown. Additionally, we present a model (D4), where the binding energy of H2 and its isotopologues were scaled by 0.1 and several models adopting the H2 removal method proposed by Garrod & Pauly (2011) applied to all species (BE2), only to H2 (BE3) and only to H and H2 (BE4). The observed profiles are depicted in black (errors as grey-shaded areas). |

|

Fig. 6 Coverage of dust grain as a function of time (x-axis) and radius (y-axis). The left column shows the percentage of empty binding sites, which are typically filled quickly by absorbed and newly formed molecules. The right column shows the percentage of H2. |

4.2 Combining H-abstraction reactions and chemical desorption

Various laboratory experiments (Hidaka et al. 2009, Chuang et al. 2016; Minissale et al. 2016c) agree that H-abstraction reactions play an important role in the methanol formation scheme. Theoretically, the inclusion of H-abstraction should have two important effects on the gas phase reservoirs of CH3OH and CH2DOH. (I) The reactive desorption rate of methanol increases due to cyclic H-abstraction events (e.g. Jin & Garrod 2020): when a CH3OH molecule (or a CH2DOH molecule) is formed, it can be desorbed into the gas phase with a certain probability. However, in the majority of cases, it stays on the grain surface, where it can be subject of H-abstraction reactions that reduce it back to CH3O or CH2OH, which can be hydrogenated to methanol again and thereby desorbing with some probability into the gas phase. In principle, the described addition and abstraction steps can be repeated multiple times, thereby amplifying the reactive desorption process beyond what is suggested by the reactive desorption efficiency. (II) The N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) is increased due to preferential abstraction of CH2DOH to CH2DO and CHDOH (Hidaka et al. 2009): the reaction CH2DOH + H has three possible out-comes in our chemical network. It can either reduce to CH2OH, from where a hydrogenation to CH3OH is more likely to happen than a deuteration to CH2DOH again, or it can reduce to CHDOH and CH2DO, from where a hydrogenation to CH2DOH is more likely to happen than a deuteration to CHD2OH. The branching ratio (0.17) for the former reaction, likely reversing the deuteration, is lower than for the latter two possibilities (0.33 and 0.5, respectively), preserving the deuteration. It is noteworthy that the likelihood of hydrogenation versus deuteration reactions depends on the ratio of deuterium to hydrogen atoms and the assumed mode of diffusion on the surface of the dust grains. In case the D/H ratio is sufficient to compensate the slower diffusion of deuterium atoms, deuteration reactions can become more likely than hydrogenation reactions. However, this is not the case for the models presented in this Section.

Figure 7 shows the impact of the inclusion of the H-abstraction reactions following the Hidaka et al. 2009-scheme, and their combination with either a simple constant reactive desorption efficiency of 1% (model D5) or the experiment-based reactive desorption efficiencies following Minissale et al. (2016b) (model D7). For the purpose of comparison, we also show the respective models solely including H-addition reactions (model D4 and D6).

Models D4 and D5, using a constant reactive desorption efficiency of 1% show both theoretically expected effects. Model D5, which includes H-abstraction reactions, has higher column densities of both CH3OH and CH2DOH. For CH3OH the increase can be attributed to cyclic H-abstraction (effect I), whereas for CH2DOH it is a combination of both described effects (effects I and II). In alignment with our expectations, we find that the increase in CH2DOH is higher than the increase in CH3OH, resulting in an approximately two percentage points higher N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) ratio.

Models D6 and D7 apply an experiment-based desorption mechanism following the proposed equation by Minissale et al. (2016b), which produces an individual desorption efficiency for every product species and surface coverage. In general, they produce lower column densities than model D4 and D5 for both CH3OH and CH2DOH, which is expected as the experiment-based reactive desorption mechanism yields much lower desorption efficiencies than 1% for heavier molecules. Given the used values for reaction enthalpies Hform and binding energies Eb (presented in Table A1 of Riedel et al. 2023), the desorption efficiency is 0.05 for CH2OH→CH3OH and 0.08% for CH3O → CH3 OH on a pure CO surface.

Models D6 and D7 do not follow the same trend as described above for model D4 and D5. The column densities of CH3OH and CH2DOH are both increased due to the cyclic H-abstraction (effect I) in model D7. However, the increase for CH2DOH is lower than for CH3OH for radii above 4000 AU, consequently resulting in a lower N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) ratio for model D7 compared to model D6. The smaller increase in CH2DOH is caused by different reactive desorption efficiencies for the different formation reactions of CH2DOH. Reaction (6) (CH2OH → CH2DOH) and reaction (7) (CHDOH → CH2DOH) both have a reactive desorption efficiency of around 0.05%, while reaction (8) (CH2DO → CH2DOH) has a reactive desorption efficiency of around 0.08%. For the inner radii, CH2DOH formation is dominated by reaction (8). For the outer radii, however, the efficiency of reaction (6) increases, as the D atoms mobility is increased due to the higher dust temperatures. Therefore, the effective CH2DOH reactive desorption efficiency is decreased, since this formation route contributes less of its products to the gas phase.

In our previous works, abstraction reactions were left out entirely or were only used for selected parameter sets. Vasyunin et al. (2017) argued that branching ratios between H-addition and H-abstraction reactions were not measured accurately enough to lower the overall uncertainties of their presented model. Therefore, the authors opted to use a simpler network solely including H-addition reactions. Riedel et al. (2023) included H-abstraction reactions following the scheme proposed by Hidaka et al. (2009) but also tested selected parameter sets with a simpler network comprising only the H-addition reactions. They found the inclusion of H-abstraction reactions to cause a substantial increase in the CH3OH column densities, while the CH2DOH column densities were found to be decreased, consequently lowering the N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) to values that are in worse agreement with observations. Admittedly, this result was impacted by the fact that the presented models also used the experiment-based mechanism for reactive desorption proposed by Minissale et al. (2016b) and therefore experienced the same effect as described above for models D6 and D7. The effect could be seen even more pronounced in the models presented in Riedel et al. (2023), as the use of the SC model causes CH3OH to be formed predominantly by hydrogenation of CH3O, which has a higher reactive desorption efficiency as the competing reaction involving its isome CH2OH. Hence, the effective CH3OH reactive desorption efficiency is higher than in the RDC model.

Recently, Punanova et al. (2025) pointed out that H2CO, an important intermediary in the methanol formation chain, is typically strongly overproduced, resulting in an inverse H2CO:CH3OH abundance of the chemical models compared to observations. Although formaldehyde is formed efficiently on the grain, its main formation reaction is the gas phase reaction CH3 + O → H2CO + H. Punanova et al. (2025) propose to remedy the overproduction of H2CO by introducing the additional reaction channel CH3 + O → CO + H2 + H and constraining its branching ratio (CO+H2+H:H2CO+H = 8:1) observationally. Since the publication of this work is very recent, its proposed constraint has not been tested by us. However, we find that it is unlikely to have large consequences for the formation of methanol, as it concerns the gas phase formation of formaldehyde. We also would like to point out that for the models presented in the present work, the H2CO:CH3OH ratio strongly depends on the model parameters. Indeed, the H2CO:CH3OH ratio for model D5 is not inverse to the observed one.

|

Fig. 7 Column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right) of various diffusive models, either including solely H-addition reactions (round markers) or H-addition and H-abstraction reactions (diamond markers) combined with either a constant reactive desorption efficiency of 1% (grey) or an experiment-based reactive desorption efficiency based on Minissale et al. (2016b) (navy). The observed profiles are depicted in black. Errors are shown as grey-shaded areas. |

|

Fig. 8 Column density profiles of CH3OH (left) and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) profiles (right) of the diffusive model D4 (grey), with an initial atomic hydrogen abundance of 10−8, and diffusive model D8 (green), with an initial atomic hydrogen abundance of 0.5. The observed profiles are depicted in black (errors as grey-shaded areas). |

4.3 Varying the initial H abundances

Unfortunately, a direct measurement of the H2 abundance in cold dense cores is not possible, as the highly symmetric H2 molecule does not possess a permanent dipole moment and is therefore only directly accessible in the UV and near- and far-infrared regime. Therefore, a commonly used tool is the use of 13CO or 18CO abundances combined with a conversion relation of the respective CO isotopologue’s abundance to the one of molecular hydrogen. Simultaneously, the atomic hydrogen abundance can be obtained by accompanying HI narrow self-absorption observations, as was done by Li & Goldsmith (2003). They determined [HI]/[H2] number density ratios between 10−4 and 8 × 10−3 for over 30 dark clouds in the Taurus and Perseus region. Goldsmith & Li (2005) later studied four dark clouds in more detail. There, they obtained an [HI]/[H2] ratio of 10−3 specifically for L1544, resulting in an H abundance of 5 × 10−4 with respect to the total proton density nH= n(H) + 2n(H2). Although it is a common modelling approach to start the simulation with no (or very small) atomic hydrogen abundances, in recent years several modellers adopted initial abundances for atomic hydrogen following the values suggested by the above mentioned works (e.g. Jin & Garrod (2020): 5 × 10−4 for L1544; Wakelam et al. (2021): 5 × 10−4, 1 × 10−3 and 1 × 10−2 for an averaged physical structure representative of TMC1).

In this section, we investigate the effect of a variation in the initial abundances of atomic and molecular hydrogen on the CH3OH column density and N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3 OH) ratio profile (see Figure 8). Here, we adopt an even higher value of 0.5 for atomic hydrogen and 0.25 for molecular hydrogen, which is a ratio more typical of translucent clouds. The initial abundances for pH2 and oH2 are adjusted accordingly to preserve an ortho-to-para ratio of 10−3. The HD abundance is divided in half, where one half remains HD and the other is thought to be in the form of H and D atoms, respectively, thereby increasing the D abundance to the same value as the HD abundance. Consequently, the initial D/H ratio is lowered from a value of 1.0 to 1.6 × 10−5. The modified initial abundances are summarised in Table 3. The diffusive model D4, not including H-abstraction reactions, is run again with the modified initial abundances, resulting in model D8.

An increased atomic hydrogen abundance is a priori expected to increase the production of molecules that are formed by hydrogenation reactions of common ice species, such as CH3OH. Indeed, we find that the CH3OH column density is increased by roughly a factor of 2.5, while the CH2DOH column density is reduced by that factor, resulting in a slightly lower N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) ratio. The decrease of the CH2DOH column density is caused by the lower initial D/H ratio. The N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) in model D8 is eventually able to reach values similar to those in model D4; however, the two models only converge for evolutionary times past 106 yr.

A similar result is obtained in Sipilä et al. (2024) (see Appendix B). There, the authors found a highly increased H2CO and CH3OH formation for larger radii, while the variation for inner radii is small. Since the volume density for the outer radii is low, their contribution to the CH3OH column density is low as well. Therefore, the CH3OH column density of the 50:50 H/H2 model is only increased by a factor 1.8 compared to reference model with initially no atomic hydrogen.

Initial H abundances used for a 50/50 H/H2.

5 Conclusion

Surprisingly high abundances of methanol and other COMs were found in several surveys targeting dark molecular clouds (e.g. Bacmann et al. 2012; Cernicharo et al. 2012; Jiménez-Serra et al. 2016). Additionally, multiple experiments (Fedoseev et al. 2015; Chuang et al. 2016; Fedoseev et al. 2017; Qasim et al. 2019; Ioppolo et al. 2021; Fedoseev et al. 2022; Santos et al. 2022) conducted at low temperatures (T = 10 − 16 K) have proposed grain surface COM formation routes involving (at least) one reaction step with two heavy immobile reactants. These kinds of reactions pose a severe bottleneck in a diffusive-only grain chemistry and likely render the formation route inefficient. Including non-diffusive grain chemistry evades the obstacle of immobility of reactants by taking into consideration that in a (small) number of cases, the reactants are already formed in close proximity to each other.

We updated the astrochemical code pyRate by including various non-diffusive reaction mechanisms, including Eley-Rideal reactions, photodissociation-induced reactions, and three-body reactions, thereby following closely the proposed formulation by Jin & Garrod (2020) and Garrod et al. (2022). We investigated methanol and its deuterated isotopologues, as methanol and its precursors are considered to be fundamental building blocks for both gas phase and grain surface formation routes of COMs. We presented several models for the prediction of abundance, column density, and deuterium fraction profiles of CH3OH and CH2DOH in the prototypical pre-stellar core L1544. Subsequently, we compared our model results to our previous work (Riedel et al. 2023), exploring various methods to increase the efficiency of hydrogen and deuterium atom diffusion and with available single-dish observations presented in Chacón-Tanarro et al. (2019).

Our main conclusions are as follows. When applying the single collision model (SC model) for the derivation of reaction probabilities of reactions with an activation-energy barrier:

Models with a slow diffusion process (Ed/Eb = 0.55) cannot reproduce the observed column density profiles;

The addition of non-diffusive reaction mechanisms provides only minor contributions to methanol formation, independent of the selected mechanisms. Although the majority of CH3OH and CH2DOH is still produced by successive addition of H (or D) atoms, reactions between heavier products (e.g. OH+CH3 → CH3OH, O+CH3 → CH3O and OH+CH2 → CH2OH) can contribute significantly in certain regions and/or at certain time steps;

-

Increasing the diffusion rate of hydrogen and deuterium atoms by either a slow thermal hopping process (Ed/Eb = 0.55) that is accompanied by diffusion by quantum tunneling of H and D atoms or a fast thermal hopping process (Ed/Eb = 0.2) results in significantly better agreement with observed profiles.

When applying the reaction-diffusion competition model (RDC model) for the derivation of reaction probabilities:

In the RDC model, reactions with an activation-energy barrier are significantly more likely to happen when compared to the SC model, reducing the importance of an efficient diffusion process. Models with a slow diffusion process (Ed/Eb = 0.55) match the observed column density profile for CH3OH within a factor of around two, which is a good agreement;

The N(CH2DOH)/N(CH3OH) ratio derived with the RDC model is lower by a factor of two to three in comparison to the one derived with the SC model and the observed ratio. This is due to a combination of an increased importance of H2CO→CH2OH→CH2DOH relative to H2CO→ CH2DO→ CH2DOH and a lowered D/H ratio;

Similar to the results derived with the SC model, the addition of non-diffusive reaction mechanisms provides only minor contributions to methanol formation, independent of the selected mechanisms;

The reaction H2CO+CH3O → CH3OH + HCO (reaction (9)) is theoretically (Simons et al. 2020) and experimentally (Santos et al. 2022) predicted to provide a contribution of 60–90% to the formation of CH3OH. Following the introduction of reaction (9) to our chemical network, we derived only a negligible contribution for reaction (9) due to the fact that the occurrence rate of either H2CO or CH3O produced in close proximity to the other reactant is quite low, resulting in a very small reaction rate. Therefore, we cannot confirm the result;