| Issue |

A&A

Volume 701, September 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A40 | |

| Number of page(s) | 26 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554836 | |

| Published online | 02 September 2025 | |

Euclid: Early Release Observations of ram-pressure stripping in the Perseus cluster

Detection of parsec-scale star formation within the low surface brightness stripped tails of UGC 2665 and MCG +07-07-070⋆

1

University Observatory, LMU Faculty of Physics, Scheinerstrasse 1 81679 Munich, Germany

2

Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, CNES, LAM, Marseille, France

3

Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Cité, CEA, CNRS, AIM, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France

4

Universitäts-Sternwarte München, Fakultät für Physik, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Scheinerstrasse 1 81679 München, Germany

5

Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, Observatoire astronomique de Strasbourg, UMR 7550, 67000 Strasbourg, France

6

School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK

7

INAF-Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio di Bologna, Via Piero Gobetti 93/3 40129 Bologna, Italy

8

Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Koramangala II Block, Bangalore 560034, India

9

Department of Physics and Electronics, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Bangalore 560029, India

10

Waterloo Centre for Astrophysics, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada

11

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands

12

Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK

13

Sterrenkundig Observatorium, Universiteit Gent, Krijgslaan 281 S9 9000 Gent, Belgium

14

Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, PO Box 800 9700 AV, Groningen, The Netherlands

15

Ludwig-Maximilians-University, Schellingstrasse 4 80799 Munich, Germany

16

Univ. Lille, CNRS, Centrale Lille, UMR 9189 CRIStAL, 59000 Lille, France

17

Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, Institut d’astrophysique spatiale, 91405 Orsay, France

18

Space physics and astronomy research unit, University of Oulu, Pentti Kaiteran katu 1 FI-90014, Oulu, Finland

19

ESAC/ESA, Camino Bajo del Castillo, s/n., Urb. Villafranca del Castillo 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain

20

School of Mathematics and Physics, University of Surrey, Guildford, Surrey GU2 7XH, UK

21

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, Via Brera 28 20122 Milano, Italy

22

IFPU, Institute for Fundamental Physics of the Universe, Via Beirut 2 34151 Trieste, Italy

23

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste, Via G. B. Tiepolo 11 34143 Trieste, Italy

24

INFN, Sezione di Trieste, Via Valerio 2 34127 Trieste TS, Italy

25

SISSA, International School for Advanced Studies, Via Bonomea 265 34136 Trieste, TS, Italy

26

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Università di Bologna, Via Gobetti 93/2 40129 Bologna, Italy

27

INFN-Sezione di Bologna, Viale Berti Pichat 6/2 40127 Bologna, Italy

28

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Via dell’Osservatorio 5 35122, Padova, Italy

29

INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino, Via Osservatorio 20 10025 Pino Torinese (TO), Italy

30

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Genova, Via Dodecaneso 33 16146 Genova, Italy

31

INFN-Sezione di Genova, Via Dodecaneso 33 16146 Genova, Italy

32

Department of Physics “E. Pancini”, University Federico II, Via Cinthia 6 80126 Napoli, Italy

33

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Via Moiariello 16 80131 Napoli, Italy

34

Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Universidade do Porto, CAUP, Rua das Estrelas PT4150-762, Porto, Portugal

35

Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade do Porto, Rua do Campo de Alegre 4150-007, Porto, Portugal

36

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università degli Studi di Torino, Via P. Giuria 1 10125 Torino, Italy

37

INFN-Sezione di Torino, Via P. Giuria 1 10125 Torino, Italy

38

European Space Agency/ESTEC, Keplerlaan 1 2201 AZ Noordwijk, The Netherlands

39

Institute Lorentz, Leiden University, Niels Bohrweg 2 2333 CA Leiden, The Netherlands

40

INAF-IASF Milano, Via Alfonso Corti 12 20133 Milano, Italy

41

Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (CIEMAT), Avenida Complutense 40 28040 Madrid, Spain

42

Port d’Informació Científica, Campus UAB, C. Albareda s/n 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona), Spain

43

Institute for Theoretical Particle Physics and Cosmology (TTK), RWTH Aachen University, 52056 Aachen, Germany

44

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, Via Frascati 33 00078 Monteporzio Catone, Italy

45

INFN section of Naples, Via Cinthia 6 80126 Napoli, Italy

46

Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA

47

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Augusto Righi” – Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Viale Berti Pichat 6/2 40127 Bologna, Italy

48

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, Vía Láctea 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

49

Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh EH9 3HJ, UK

50

Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK

51

European Space Agency/ESRIN, Largo Galileo Galilei 1 00044 Frascati, Roma, Italy

52

Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, CNRS/IN2P3, IP2I Lyon, UMR 5822, Villeurbanne F-69100, France

53

Institut de Ciències del Cosmos (ICCUB), Universitat de Barcelona (IEEC-UB), Martí i Franquès 1 08028 Barcelona, Spain

54

Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA), Passeig de Lluís Companys 23 08010 Barcelona, Spain

55

UCB Lyon 1, CNRS/IN2P3, IUF, IP2I Lyon, 4 rue Enrico Fermi 69622 Villeurbanne, France

56

Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London, Holmbury St Mary, Dorking, Surrey RH5 6NT, UK

57

Departamento de Física, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Edifício C8, Campo Grande PT1749-016, Lisboa, Portugal

58

Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Campo Grande 1749-016, Lisboa, Portugal

59

Department of Astronomy, University of Geneva, ch. d’Ecogia 16 1290 Versoix, Switzerland

60

INAF-Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Via del Fosso del Cavaliere, 100 00100 Roma, Italy

61

INFN-Padova, Via Marzolo 8 35131 Padova, Italy

62

Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS/IN2P3, CPPM, Marseille, France

63

Space Science Data Center, Italian Space Agency, Via del Politecnico snc 00133 Roma, Italy

64

School of Physics, HH Wills Physics Laboratory, University of Bristol, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TL, UK

65

Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, Giessenbachstr. 1 85748 Garching, Germany

66

Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1029 Blindern 0315 Oslo, Norway

67

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA

68

Department of Physics, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YB, UK

69

Felix Hormuth Engineering, Goethestr. 17 69181 Leimen, Germany

70

Technical University of Denmark, Elektrovej 327 2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark

71

Cosmic Dawn Center (DAWN), Denmark

72

Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, UMR 7095, CNRS, and Sorbonne Université, 98 bis boulevard Arago 75014 Paris, France

73

Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Königstuhl 17 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

74

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA

75

Department of Physics and Helsinki Institute of Physics, Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland

76

Université de Genève, Département de Physique Théorique and Centre for Astroparticle Physics, 24 quai Ernest-Ansermet CH-1211, Genève 4, Switzerland

77

Department of Physics, P.O. Box 64 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland

78

Helsinki Institute of Physics, Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

79

Laboratoire d’etude de l’Univers et des phenomenes eXtremes, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, 92190 Meudon, France

80

SKA Observatory, Jodrell Bank, Lower Withington, Macclesfield, Cheshire SK11 9FT, UK

81

Centre de Calcul de l’IN2P3/CNRS, 21 avenue Pierre de Coubertin 69627 Villeurbanne Cedex, France

82

Dipartimento di Fisica “Aldo Pontremoli”, Università degli Studi di Milano, Via Celoria 16 20133 Milano, Italy

83

, Via Celoria 16 20133 Milano, Italy

84

Universität Bonn, Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Auf dem Hügel 71 53121 Bonn, Germany

85

INFN-Sezione di Roma, Piazzale Aldo Moro, 2 – c/o Dipartimento di Fisica, Edificio G. Marconi 00185 Roma, Italy

86

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Augusto Righi” – Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Via Piero Gobetti 93/2 40129 Bologna, Italy

87

Department of Physics, Institute for Computational Cosmology, Durham University, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK

88

Université Côte d’Azur, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, CNRS, Laboratoire Lagrange, Bd de l’Observatoire, CS 34229 06304 Nice cedex 4, France

89

Université Paris Cité, CNRS, Astroparticule et Cosmologie, 75013 Paris, France

90

CNRS-UCB International Research Laboratory, Centre Pierre Binétruy, IRL2007, CPB-IN2P3, Berkeley, USA

91

Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, 98bis Boulevard Arago 75014 Paris, France

92

Institute of Physics, Laboratory of Astrophysics, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Observatoire de Sauverny, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland

93

Aurora Technology for European Space Agency (ESA), Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada 28692 Madrid, Spain

94

Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Campus UAB, 08193 Bellaterra, (Barcelona), Spain

95

School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics, Newcastle University, Herschel Building, Newcastle-upon-Tyne NE1 7RU, UK

96

DARK, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Jagtvej 155 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark

97

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 3G1, Canada

98

Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 2Y5, Canada

99

Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales – Centre spatial de Toulouse, 18 avenue Edouard Belin 31401 Toulouse Cedex 9, France

100

Institute of Space Science, Str. Atomistilor, nr. 409 Măgurele, Ilfov 077125, Romania

101

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, Calle Serrano 117 28006 Madrid, Spain

102

Universidad de La Laguna, Departamento de Astrofísica, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

103

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “G. Galilei”, Università di Padova, Via Marzolo 8 35131 Padova, Italy

104

Institut für Theoretische Physik, University of Heidelberg, Philosophenweg 16 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

105

Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie (IRAP), Université de Toulouse, CNRS, UPS, CNES, 14 Av. Edouard Belin 31400 Toulouse, France

106

Université St Joseph; Faculty of Sciences, Beirut, Lebanon

107

Departamento de Física, FCFM, Universidad de Chile, Blanco Encalada 2008, Santiago, Chile

108

Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), Edifici RDIT, Campus UPC, 08860 Castelldefels, Barcelona, Spain

109

Satlantis, University Science Park, Sede Bld 48940, Leioa-Bilbao, Spain

110

Institute of Space Sciences (ICE, CSIC), Campus UAB, Carrer de Can Magrans, s/n 08193 Barcelona, Spain

111

Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Tapada da Ajuda 1349-018, Lisboa, Portugal

112

Cosmic Dawn Center (DAWN), Denmark

113

Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Jagtvej 128 2200 Copenhagen, Denmark

114

Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, Departamento de Electrónica y Tecnología de Computadoras, Plaza del Hospital 1 30202 Cartagena, Spain

115

INFN-Bologna, Via Irnerio 46 40126 Bologna, Italy

116

Infrared Processing and Analysis Center, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA

117

INAF, Istituto di Radioastronomia, Via Piero Gobetti 101 40129 Bologna, Italy

118

Department of Physics, Oxford University, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH, UK

119

ICL, Junia, Université Catholique de Lille, LITL, 59000 Lille, France

⋆⋆ Corresponding author: Koshy.George@physik.lmu.de

Received:

28

March

2025

Accepted:

28

May

2025

Euclid is delivering optical and near-infrared imaging data over 14 000 deg2 on the sky at spatial resolution and surface brightness levels that can be used to understand the morphological transformation of galaxies within groups and clusters. Using the Early Release Observations (ERO) of the Perseus cluster, we demonstrate the capability offered by Euclid in studying the nature of perturbations for galaxies in clusters. Filamentary structures are observed along the discs of two spiral galaxies, UGC 2665 and MCG +07-07-070, with no extended diffuse emission expected from tidal interactions at surface brightness levels of ∼30 mag arcsec−2. The detected features exhibit a good correspondence in morphology between optical and near-infrared wavelengths, with a surface brightness of ∼25 mag arcsec−2, and the knots within the features have sizes of ∼ 100 pc, as observed through IE imaging. Using the Euclid, CFHT, UVIT, and LOFAR 144 MHz radio continuum observations, we conducted a detailed analysis to understand the origin of the detected features. We constructed the Euclid IE−YE, YE−HE, and CFHT u − r, g − i colour-colour plane and show that these features contain recent star formation events, which are also indicated by their Hα and NUV emissions. Euclid colours alone are insufficient for studying stellar population ages in unresolved star-forming regions, which require multi-wavelength optical imaging data. There are features with red colours that can be explained by dust being stripped along with the gas in these regions. The morphological shape, orientation, and mean age of the stellar population, combined with the presence of extended radio continuum cometary tails can be consistently explained if these features formed during a recent ram-pressure stripping event. This result further confirms the exceptional qualities of Euclid in the study of galaxy evolution in dense environments.

Key words: galaxies: clusters: intracluster medium / galaxies: evolution / galaxies: spiral / galaxies: star formation

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Star-forming galaxies in the Universe follow a tight relation between the star-formation rate and the stellar mass, which has been observed to be present from redshift z ∼ 6 to 0 Brinchmann et al. 2004; Salim et al. 2007; Noeske et al. 2007; Elbaz et al. 2007; Daddi et al. 2007; Popesso et al. 2023. The existence of this relation since early epochs suggests that the process of gas condensation and star formation is well-regulated and closely tied to the galaxy’s gravitational potential well. Primarily, star-forming galaxies have spiral morphologies, where gas stabilises and collapses to form new star-forming regions in the disc, a process regulated by the availability of atomic and molecular hydrogen Kennicutt & Evans 2012. In dense environments, including galaxy clusters and groups, external processes such as galaxy mergers, starvation, thermal evaporation, ram-pressure stripping, and tidal interaction with the cluster potential can alter the gas content and star formation process (see for reviews Boselli & Gavazzi 2006, 2014; Cortese et al. 2021). When galaxies fall into galaxy clusters for the first time, they can experience mergers on the outskirts that disrupt their gas and stellar content, potentially triggering a starburst episode that rapidly depletes fuel for regulated star formation Barnes & Hernquist 1992; Barnes 2004. The cluster environment can cut off the gas supply to galaxies, leading to a gradual reduction of star formation, known as starvation, which slows down the star formation rate once the galaxy becomes a satellite of a larger halo Larson et al. 1980. The cluster potential can create perturbations to galaxies and even disrupt low-mass galaxies falling in radial orbits close to the cluster centre Valluri 1993; Moore et al. 1996; Mastropietro et al. 2005. The cold interstellar medium (ISM) of a galaxy can interact with the surrounding hot intracluster medium (ICM), leading to thermal evaporation Cowie & Songaila 1977. Ram-pressure stripping (RPS) can remove gas from the disc of an infalling gas-rich spiral galaxy, dragging its interstellar medium into the surrounding intergalactic medium Gunn & Gott 1972; Boselli et al. 2002. This process can be observed in the form of stripped tails in CO, radio continuum, H I, dust, Hα, and X-rays Gavazzi et al. 2001; Vollmer et al. 2004; Kenney et al. 2004; Sun et al. 2006; Chung et al. 2009; Yagi et al. 2010; Merluzzi et al. 2013; Fumagalli et al. 2014; Abramson et al. 2016; Jáchym et al. 2017; Moretti et al. 2018; Poggianti et al. 2019; Roberts et al. 2021a,b; Ignesti et al. 2022. The trajectory of the infalling galaxy, its properties, and those of the cluster determine whether these processes act alone or jointly. Gullieuszik et al. 2020; Smith et al. 2022.

Hydrodynamical processes such as RPS act only on the diffuse components of the ISM (gas, dust), leaving the stellar component unaffected. They can easily be identified whenever the tails of stripped material do not contain stars. Indeed, several examples exist of stripped tails of cold, ionised, or hot gas without any associated stellar emission

Gavazzi et al. 2001; Boselli et al. 2016; Boissier et al. 2012; Yagi et al. 2007, 2010, 2017; Jáchym et al. 2017; Laudari et al. 2022; Serra et al. 2023. However, under specific and still unclear physical conditions Boselli et al. 2022, star formation can occur in the tails of stripped gas Owen et al. 2006; Cortese et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2010; Owers et al. 2012; Ebeling et al. 2014; Fumagalli et al. 2014; Rawle et al. 2014; Poggianti et al. 2016, 2019; Bellhouse et al. 2017; Gullieuszik et al. 2017; Boselli et al. 2018; George et al. 2018, 2023; Poggianti et al. 2025; George et al. 2025. Mixing the cold ISM with the hot ICM is expected to warm up the cold gas component, preventing its collapse into giant molecular clouds, where star formation occurs. The occurrence of star formation in the stripped tail is intriguing, as it takes place outside the galaxy disc within the very hostile environment of a hot ICM, with a temperature of 107 − 8 K Sarazin 1986. Within the stripped tails, spectacular trails form, and star formation progresses as the galaxy moves within the cluster. The nearly face-on or edge-on orientation of the in-falling galaxy can make the star formation in the stripped tails appear to have a different morphology. The smallest scales at which star formation progresses in these regions, as well as their diffuse extent, can set constraints on the nature of gas collapse within the stripped tails Portegies Zwart et al. 2010; Elmegreen 2010; Elmegreen et al. 2014. To understand the size distribution of star-forming knots in the stripped gas at the faintest levels and the star-forming process in this hostile environment, it is necessary to observe star-forming regions at high spatial resolution and low surface brightness. High-resolution optical imaging of RPS galaxies can resolve knots of star formation in the stripped tails at 50–100 pc scales in nearby galaxy clusters Abramson & Kenney 2014; Kenney et al. 2015; Cramer et al. 2019; Boselli et al. 2021; Giunchi et al. 2023a; Gullieuszik et al. 2023; Waldron et al. 2023; Giunchi et al. 2025.

The recently launched Euclid mission, with its  spatial resolution in IE, can resolve these knots at 50 pc scales up to distances of 72.5 Mpc (z ∼ 0.016). Perseus (Abell 426) is a massive galaxy cluster (r200 = 2.2 Mpc, M200 = 1.2 × 1015 M⊙, velocity dispersion = 1040 km s−1) located at a redshift of ∼0.0167 Aguerri et al. 2020; Cuillandre et al. 2025a. The core region of the Perseus cluster is exceptionally rich in early-type galaxies, with a strong deficiency in late-type systems Kent & Sargent 1983. The galaxy cluster is located very close to the Galactic plane (latitude −13 degrees). There are four known RPS galaxy candidates in the central regions of the Perseus cluster (MCG +07-07-070, UGC 2654, UGC 2665, and LEDA 2191078). These RPS candidates have been identified from the presence of cometary-shaped radio continuum tails at 144 MHz and from the peculiar, asymmetric morphology of the stellar disc seen in ground-based optical imaging Roberts et al. 2022. The Euclid satellite observed the Perseus cluster in optical (IE) and infrared (YE, JE, HE) bands as part of the Euclid Early Release Observations (ERO; Euclid Early Release Observations 2025) programme. Two of these galaxies (MCG +07-07-070 and UGC 2665) are included in the Euclid ERO field with near-simultaneous co-aligned imaging in the optical and near-infrared.

spatial resolution in IE, can resolve these knots at 50 pc scales up to distances of 72.5 Mpc (z ∼ 0.016). Perseus (Abell 426) is a massive galaxy cluster (r200 = 2.2 Mpc, M200 = 1.2 × 1015 M⊙, velocity dispersion = 1040 km s−1) located at a redshift of ∼0.0167 Aguerri et al. 2020; Cuillandre et al. 2025a. The core region of the Perseus cluster is exceptionally rich in early-type galaxies, with a strong deficiency in late-type systems Kent & Sargent 1983. The galaxy cluster is located very close to the Galactic plane (latitude −13 degrees). There are four known RPS galaxy candidates in the central regions of the Perseus cluster (MCG +07-07-070, UGC 2654, UGC 2665, and LEDA 2191078). These RPS candidates have been identified from the presence of cometary-shaped radio continuum tails at 144 MHz and from the peculiar, asymmetric morphology of the stellar disc seen in ground-based optical imaging Roberts et al. 2022. The Euclid satellite observed the Perseus cluster in optical (IE) and infrared (YE, JE, HE) bands as part of the Euclid Early Release Observations (ERO; Euclid Early Release Observations 2025) programme. Two of these galaxies (MCG +07-07-070 and UGC 2665) are included in the Euclid ERO field with near-simultaneous co-aligned imaging in the optical and near-infrared.

The goal of this paper is to demonstrate the possibility opened up by Euclid in studying galaxy evolution in dense environments. We demonstrate this through a study of star-forming regions in the tails and main bodies of the galaxies UGC 2665 and MCG +07-07-070, made possible by the high spatial resolution and low surface brightness regime of Euclid’s optical and near-infrared imaging observations. The dominant perturbing mechanism can be first established using Euclid imaging data. The features resulting from gravitational perturbations are diffuse and include shells, plumes, and tidal tails Bílek et al. 2020. On the other hand, those related to RPS are filamentary and clumpy, with a cometary shape, as expected from star formation in the stripped gas Boselli et al. 2022. The sensitivity to low surface brightness features, in addition to the angular resolution offered by Euclid, can be used to identify the dominant perturbing mechanism (gravitational or hydrodynamic), resolve the star-forming regions in the stripped material, and reconstruct their star formation history. Finally, our results demonstrate the capabilities of the Euclid Wide Survey (EWS) in detecting low surface brightness features around galaxies across a large region of the sky, enabling the study of galaxy evolution in different environments. The low surface brightness imaging data from EWS, which reaches 29.8 mag arcsec−2, will enable surface brightness limits necessary to identify any possible perturbations induced on the stellar component by gravitational perturbations, and thus determine the dominant perturbing mechanism in rich environments on large, statistically significant samples. In identifying galaxies undergoing an RPS event through morphological analysis of broadband imaging data, it is particularly important to note that the lack of any evident perturbation in the stellar distribution is crucial for ruling out gravitational perturbations.

Throughout the paper we adopt a standard flat ΛCDM cosmology with Ωm = 0.319 and H0 = 67 km s−1Mpc−1Planck Collaboration VI 2020. Magnitudes are in the AB system, and, in concordance with other Perseus ERO papers, we adopted a distance of 72 ± 3 Mpc to the Perseus cluster, where 1″ corresponds to 0.338 kpc Cuillandre et al. 2025a.

2. Data and analysis

Cuillandre et al. 2025b have presented details on Euclid ERO and data reduction optimised for preserving low surface brightness features. We used the data products generated as part of the Perseus cluster observations, which are described in detail in Cuillandre et al. 2025a. The Euclid visible imager (VIS) has a broad passband (IE) that covers the wavelength range 5500–9000 Å Cropper et al. 2014, 2016; Euclid Collaboration: Cropper et al. 2025. The near-infrared spectrometer and photometer (NISP) covers the wavelength range 9200–20 000 Å using the YE, JE, HE passbands Maciaszek et al. 2014, 2016; Euclid Collaboration: Jahnke et al. 2025. Observations were taken centred on coordinates RA = 03h18m40s, Dec = 41° 39′00″ with a ∼0.7 deg2 field of view. The Perseus imaging from ERO was created by combining four reference observation sequences (ROS), whereas the EWS will consist of one ROS Euclid Collaboration: Scaramella et al. 2022; Euclid Collaboration: Mellier et al. 2025. The final combined image exposure time is 7456 s in the IE filter and 1392.2 s in the YE, JE, and HE filters. Euclid VIS and NISP imaging data have pixel scales of 0.1 arcsec pix−1 and 0.3 arcsec pix−1, with angular resolutions of  and

and  , respectively. This enabled us to achieve resolved spatial scales of ∼54 pc in VIS and 135 pc in NISP imaging observations of the stripped tails. The limiting surface brightness of the Perseus cluster field is 30.1 mag arcsec−2 in IE, 29.1 mag arcsec−2 in YE, 29.2 mag arcsec−2 in JE, and 29.2 mag arcsec−2 in HE for a 10″ × 10″ scale at 1σ Cuillandre et al. 2025a.

, respectively. This enabled us to achieve resolved spatial scales of ∼54 pc in VIS and 135 pc in NISP imaging observations of the stripped tails. The limiting surface brightness of the Perseus cluster field is 30.1 mag arcsec−2 in IE, 29.1 mag arcsec−2 in YE, 29.2 mag arcsec−2 in JE, and 29.2 mag arcsec−2 in HE for a 10″ × 10″ scale at 1σ Cuillandre et al. 2025a.

We used the optical broadband u, g, r, i, z photometry and narrowband Hα imaging data of the Perseus cluster field taken with the Canada France Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) before the Euclid launch. Details on the CFHT observations, data analysis, and image quality for all the bands are given in Cuillandre et al. 2025a. The image quality of CFHT band images varies between u , g

, g , r

, r , i

, i , z

, z , and Hα

, and Hα . The narrowband Hα ‘off’ filter (CFHT ID 9604), centred on λc = 6719 Å, has a width of δλ = 109 Å, which corresponds to a heliocentric velocity range of 4660–9600 km s−1 and is used for Hα observations. We created the Hα stellar continuum-subtracted (pure Hα+N II emission) image by subtracting with the r band image of the field.

. The narrowband Hα ‘off’ filter (CFHT ID 9604), centred on λc = 6719 Å, has a width of δλ = 109 Å, which corresponds to a heliocentric velocity range of 4660–9600 km s−1 and is used for Hα observations. We created the Hα stellar continuum-subtracted (pure Hα+N II emission) image by subtracting with the r band image of the field.

We used the archival data of Perseus cluster observed using the Ultra-Violet Imaging Telescope (UVIT) onboard AstroSat Agrawal 2006; Tandon et al. 2017. The level 2 data were generated using the latest version (7.0.1) of the UVIT pipeline Joseph et al. 2025. The observations are in the far ultraviolet [FUV; filter F154W: λmean = 1541 Å, δλ = 380 Å. integration time = 11099 s], and the near ultraviolet [NUV; filter N245M: λmean = 2447 Å, δλ = 280 Å, integration time = 10966.4 s]. The UVIT NUV imaging was performed using a narrowband filter at  , compared to the FUV imaging done with a broadband filter at

, compared to the FUV imaging done with a broadband filter at  resolution. We used NUV N245M imaging in the analysis as it offers a better resolution than FUV Tandon et al. 2017, 2020.

resolution. We used NUV N245M imaging in the analysis as it offers a better resolution than FUV Tandon et al. 2017, 2020.

We used the LOw Frequency ARray (LOFAR) 144 MHz observations of Perseus cluster field for radio continuum emission from the galaxies. These observations were taken as part of LOFAR Two-metre Sky Survey Shimwell et al. 2017, 2019. The LOFAR 144 MHz image covers the central ∼2° × 2° of the Perseus cluster field, with a resolution of 6″ and an RMS of 100 μJy/beam. The details of the LOFAR data reduction and analysis are presented in Roberts et al. 2022; van Weeren et al. 2024.

We note that the data from other wavelengths are at different spatial resolution and relative depths. Comparisons of observations from different instruments and wavelengths can be biased by this sensitivity issue, especially when using Euclid’s low surface brightness optimized imaging. This makes it difficult to quantitatively compare the details of the galaxies at low surface brightness between different wavelengths.

We used stellar masses derived from the spectral energy distribution fitting over the u, g, r, i, z, IE, YE, JE, and HE photometry, using the hyperz code Bolzonella et al. 2000, 2010. The effective radius is measured from the surface brightness profile using AutoProf/AstroPhot. Details of the derivation of these quantities are given in Cuillandre et al. 2025a.

A colour composite image of UGC 2665 and MCG +07-07-070 made from IE, YE, and HE band is given in Figs. 1 and 2.

|

Fig. 1. Colour-composite image of the UGC 2665 galaxy created by combining and assigning blue, green, and red colours for IE, YE, and HE imaging data. The direction to the cluster centre is shown with a light magenta-coloured arrow. In the bottom right of the image, the blue patch is an artefact caused by dichroic ghost in IE imaging. |

3. Results

3.1. Identifying the dominant perturbing mechanism: Gravitational or ram-pressure stripping

Galaxies infalling into rich clusters can undergo gravitational interactions with the cluster potential as well as with other galaxies in the immediate vicinity. The gravitational interactions cancreate tidal features that form tails, shells, and plumes around the galaxies (see galaxy images in Bílek et al. 2020, 2022). These features, however, are normally very diffuse, with low surface brightness, formed from the stars that are tidally pulled out of the galaxies over a large region. On the other hand, RPS is a purely hydrodynamic process in which the gas is first stripped, sometimes appearing as filamentary cometary structures with or without clumpy and compact regions, where new episodes of star formation can occur (see Poggianti et al. 2016, 2019; Durret et al. 2021). We examine the primary mechanism responsible for the features observed in the case of two galaxies, using imaging observations from Euclid and the associated data products generated as part of ERO observations of the Perseus cluster.

3.1.1. Gravitational interaction with the whole cluster

The galaxy cluster can exert gravitational perturbations on infalling galaxies. The constituent matter of a radially infalling galaxy is subjected to the internal acceleration of the galaxy itself (agal), and the two components of the acceleration from galaxy cluster potential: the radial acceleration (arad cluster), the gradient of which tends to enhance the elongation of a galaxy along the galaxy-galaxy cluster direction, and the generally much weaker transverse acceleration (atrans cluster), the gradient of which tends to contract a galaxy in the perpendicular directions Henriksen & Byrd 1996. When the cluster arad cluster overcomes the agal, the perturbation can remove matter from the galactic disc. We compute the radial acceleration arad cluster exerted by the cluster on the galaxies using the following equation Henriksen & Byrd 1996,

The mass of the cluster within the radius r, M(r), where r is the distance of the galaxy from the cluster centre, is computed using a concentration parameter c = 6 and a Navarro–Frenk–White radial density profile Navarro et al. 1997, as described in Eq. (9) of Boselli et al. 2022. G is the gravitational constant. We adopt the position of NGC 1275, the central type-D giant elliptical galaxy, as the centre of the Perseus cluster Roberts et al. 2022. UGC 2665 is observed to be located at a projected distance of 183 kpc from the centre of the cluster (0.10 r200) with a velocity offset ∼2441 km s−1 from the Perseus cluster redshift. MCG +07-07-070 is also found very close to the cluster centre, with a projected distance of ∼220 kpc (0.12 r200) and a velocity offset with respect to the cluster ∼1618 km s−1Roberts et al. 2022. The proximity of both galaxies to the cluster centre, along with their high-velocity offsets relative to the cluster, suggests that they were recently accreted and are likely experiencing their first infall. Table 1 gives details on the two galaxies in the Perseus cluster taken from Cuillandre et al. 2025a. We used the distance from the cluster centre (r), the effective radius (Re) given in Table 1 and the dynamical mass of the Perseus cluster at location of galaxy M(r) to compute the arad cluster using Eq. (1). We computed agal of the galaxy using the following equation,

Details on the two galaxies undergoing RPS in the Perseus cluster.

The dynamical mass of the galaxy (mdyn) is estimated using the M⋆ values given in Table 1. We used the method described in Behroozi et al. 2013 where the halo mass versus stellar mass/halo mass relation can be used to compute the median stellar mass for a given halo mass. We note that the inverse of which does not give the average halo mass for a given stellar mass because of the scatter in the relation. Our goal is to get a rough estimate of the mdyn of the galaxy from the M⋆. We therefore computed the mdyn by considering the 0.01 dex scatter on the M⋆/mdyn and put a lower and upper limit for the mdyn. Within these limits we discuss whether the gravitational effects dominate over hydrodynamic effects on these galaxies. The UGC 2665 has mdyn ∼ 40 M⋆ (lower limit ∼ 29 M⋆, upper limit ∼ 67 M⋆), and the MCG +07-07-070 has ∼12.5 M⋆ (lower limit ∼ 11 M⋆, upper limit ∼ 14 M⋆).

When arad cluster/agal > 1, the cluster potential can create gravitational perturbations able to remove matter from the infalling galaxy. The computed arad cluster/agal values for both galaxies are given in Table 2. We should consider these values as upper limits, as we used projected distances from the centre of the cluster to compute arad cluster. Both galaxies are found to have agal greater than arad cluster. The cluster potential may have a greater effect on MCG +07-07-070, which has a slightly lower mass than UGC 2665. The truncation radius (Rtrunc), beyond which matter can be removed by the cluster potential, was computed for both galaxies as given in Binney & Tremaine 2008,

Computed details on gravitational and hydrodynamical effects on two galaxies.

where r, M(r) from Eq. (1) and mdyn from Eq. (2). The truncation radius is ∼ 37 kpc for UGC 2665, while it is ∼14 kpc for MCG +07-07-070. The truncation radius might range in between 33 kpc < Rtrunc < 44 kpc for UGC 2665 and 13 kpc < Rtrunc < 14 kpc for MCG +07-07-070 considering the dispersion on the mdyn. The isophotal radius measured at 26 mag arcsec−2 from the IE image is 13.64 ± 0.01 kpc for UGC 2665 and 13.12 ± 0.01 kpc for MCG+07-07-070 Cuillandre et al. 2025a. The truncation radius values are larger than the isophotal radius of the galaxies (comparable to MCG+07-07-070 lower limit), implying that it is not possible for the cluster potential to pull out material from the galaxy.

3.1.2. Gravitational interaction with nearby companions

We searched in NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED)1 for any nearby galaxy that could have gravitationally interacted with these two objects. We search within an area covered by a circle with a 20 arcminute (∼405 kpc) radius centred on the galaxy and a velocity separation of 2000 km s−1 (∼2× velocity dispersion of Perseus). The galaxies are having spectroscopic redshift information from the catalogue of Kang et al. 2024 down to r-band apparent magnitude (rPetro, 0) ∼ 20.5. Stellar masses of the galaxies are taken from Cuillandre et al. 2025a. In the case of galaxy UGC 2665 (M⋆ = 1.78 × 1010 M⊙), 67 galaxies meet these criteria, with the nearest two galaxies being WISEA J031917.76+413839.6 (M⋆ = 3.64 M⊙ × 1010 M⊙) located at a projected distance of ∼ 40 kpc to the west with a velocity difference of δv = 1577 km s−1 and WISEA J031937.46+413758.3 (M⋆ = 1.48 M⊙ × 1010 M⊙), located at a projected distance of ∼40 kpc to the east with a velocity difference of δv = 831 km s−1. The two closest galaxies in velocity space are WISEA J031848.10+412622.8 (δv = 3 km s−1) located at a projected distance of ∼281 kpc and PUDG R24 (M⋆ = 3.91 × 108 M⊙), (δv = 30 km s−1), an ultra diffuse galaxy at a projected distance ∼288 kpc Gannon et al. 2022. The radial acceleration exerted by the nearest object on the perturbed galaxy can be calculated using the same formalism discussed earlier in this section, as given in Eq. (1), but with the cluster mass replaced by the neighbouring galaxy mass and using the distance to the neighbour (r) and the effective radius of the galaxy (Re). We checked the arad neighbour/agal for all the neighbouring galaxies within the search radius of 405 kpc centred on UGC 2665 and found that the highest value is 0.004 which is negligible.

There are 131 galaxies that meet this criteria for MCG +07-07-070 (M⋆ = 2.14 × 109 M⊙) with the nearest galaxy NGC 1281 (M⋆ = 5 × 1010 M⊙) located at a projected distance of ∼61 kpc with a velocity difference δv = 315.0 km s−1. The closest galaxy in velocity space is WISEA J031943.81+412725.1 (M⋆ = 1.26 × 1010 M⊙, δv = 2 km s−1), located at a projected distance of ∼276 kpc. We checked the arad neighbour/agal for all the neighbouring galaxies within the search radius of 405 kpc centred on MCG +07-07-070 and found that the highest value is 0.09. The values are much smaller when considering the nearest galaxy in velocity space. Additionally, we note that a high-velocity encounter with another nearby galaxy can only remove mass from a galaxy when the distance between them is shorter than the typical length of the tidal tail and the galaxy’s mass is ≥1.33× dynamical mass of the main galaxy Boselli et al. 2022. We could not detect any massive galaxies at the distances of the tail length to both galaxies. Given the high-velocity dispersion (1040 km s−1) of the cluster and the relatively high velocity of the galaxies, it is unlikely that the galaxies are undergoing gravitational interactions with other galaxies at the cluster centre that could lead to the observed features. Another possibility is that interactions with a group of galaxies can collectively perturb the galaxies. In velocity space, we searched for galaxies within a 20 arcmin radius centred on both galaxies, but we did not find any grouped systems that could have interacted with the galaxy. However, as discussed in Boselli et al. 2023, gravitational interactions between the galaxies could have occurred in the past, when they were falling into the cluster outskirts, potentially perturbing the stars and the ISM. Galaxies could have undergone preprocessing in groups and got dispersed while falling into the cluster Dressler et al. 2004. This can then help strip the gas efficiently as the galaxy moves to the denser regions of the ICM. We recall here that the ram-pressure scales with the square of the velocity of the galaxy times the density of the ICM. We cannot entirely dismiss the possibility of gravitational interactions from any of these neighbouring galaxies, and galaxy groups in the past, as well as from the faint nearby galaxies with no confirmed spectroscopic redshifts. The gravitational perturbations caused by other companions can combine with those due to the cluster potential well (galaxy harassment), making the perturbing process much more efficient Moore et al. 1996. There can be galaxies in the Perseus cluster that may be detected in Euclid imaging but are not listed in NED due to being beyond the magnitude limits of available spectroscopic surveys. Such galaxies can also exert gravitational influence. In the case of UGC 2665, this is relevant, since the galaxy that appears to be interacting from the southern direction does not have confirmed redshift information.

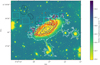

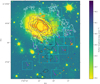

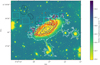

We then analysed the IE imaging data to identify signatures of gravitational interactions, such as tidal tails, shells, and plumes around the galaxies, as well as asymmetries on the galaxy disc. The colour composite images of the galaxies shown in Figs. 1 and 2 show several interesting details. The southern edge of the disc of UGC 2665 is consistent with a smooth stellar halo. In the case of MCG +07-07-070, there is diffuse emission extended along the end of the spiral arms. Isophotal analysis was performed on the IE images of the galaxies down to surface brightness levels of 30 mag arcsec−2. The isophotes generated for these levels are overlaid on the galaxy images in Figs. 3 and 4. The galaxy images are generally symmetric, suggesting that the underlying population that contributes to the bulk of the galaxy’s stellar mass is not perturbed. The contamination from neighbouring stars and galaxies creates artefacts that appear as connections in the surface brightness levels. In the case of UGC 2665, there is a connection with the galaxy in the south as shown in Fig. 3. There are features emanating from the disc of the galaxies likely due to RPS but there are no faint diffuse extended features expected from tidal interactions. Deep optical imaging is expected to reveal features from any gravitational interactions in the form of isophotal asymmetries for the galaxy disc Duc et al. 2015; Boselli et al. 2023. We note these features can be present below the surface brightness limits, as simulations suggest the presence of such features at very low surface brightness of 33 mag arcsec−2Mancillas et al. 2019. However, observations of a large sample of galaxies gathered with MegaCam at the CFHT demonstrate that tidal features are rare at a surface brightness limit below 27.5 mag arcsec−2Sola et al. 2022. The asymmetric structures seen in the images are mainly filamentary and clumpy with a cometary shape. As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, these features have gradual surface brightness variation and appear to be escaping from the stellar discs detected with a limiting surface brightness level of 30 mag arcsec−2 in theIE images.

|

Fig. 3. Colour scale IE image of galaxy UGC 2665 with the scaling set to highlight faint stripped features at the galaxy outskirts. The features that are likely part of the stripped tail are marked with cyan boxes. Coloured contours overlaid on the image are for NUV N245M imaging data of the galaxy in blue, Hα in red and 144 MHz radio continuum in black. The NUV and Hα contour levels created for 2σ, 4σ and 6σ are shown. The contour levels created for 3σ, 6σ and 12σ from LOFAR image are shown. The direction of the stripping feature is marked with magenta-coloured arrows. White contours show isophote generated for surface brightness level of 30 mag arcsec−2. |

3.1.3. Ram pressure stripping

Ram-pressure stripping occurs when the hydrodynamic pressure exerted on the cold ISM of an infalling galaxy moving at a velocity (V) into a galaxy cluster with an ICM density (ρICM) surpasses the internal gravitational force holding the cold ISM to the galaxy disc. This can be expressed as

where Σstar and Σgas represent the stellar and gas mass surface density. Following the mathematical formalism given in Boselli et al. 2022 we compute ρICM for the region around the two galaxies in the Perseus cluster. We used the radial variation of electron density (ne) in the Perseus cluster from Churazov et al. 2003 to estimate the (projected) value at the galaxy location (ne = 10−2 cm−3) within the cluster. Σstar and Σgas are computed for both galaxies within their effective radii using Eq. (20) of Boselli et al. 2022.

Since we do not have an estimate of the measured gas mass for the two galaxies, we used Eq. (25) from Boselli et al. 2022 to compute the total gas mass for each galaxy from the given stellar mass, using the luminosity-dependent XCO conversion factor provided in Boselli et al. 2022. The computed values of the ram pressure and the gravitational anchoring forces for two galaxies are given in Table 2. It is clear from Table 2 that ram pressure exceeds the gravitational anchoring of gas for both galaxies (UGC 2665 by a factor ∼61 and for MCG +07-07-070 by a factor ∼430). We caution that the location of the galaxies within the cluster (and hence the ICM density) is estimated based on the projected distance from the cluster centre. The ram-pressure computation provides an upper limit, which can decrease significantly depending on the true distance from the centre, where the ICM density is correspondingly lower.

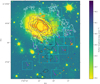

3.1.4. Multi-frequency analysis

The 2σ, 4σ, and 6σ contours2 of NUV (blue) and Hα (red) are overlaid on both galaxies in Figs. 3 and 4. Both the NUV and Hα emission are due to the presence of recent star formation and follow the filamentary features seen in Euclid imaging. Roberts et al. 2022 presents the LOFAR 144 MHz radio continuum imaging of the two galaxies, which reveals the presence of extended, cometary tails extending from the galaxy disc. This low-frequency, non-thermal radio continuum is from synchrotron emission given off by cosmic ray electrons that were accelerated by supernova within the galaxy disc. We overlay the 3σ, 6σ and 12σ 144 MHz radio continuum contours (black) over the IE imaging of the two galaxies in Figs. 3 and 4. We note that the LOFAR imaging is at a lower spatial resolution of 6″ compared to the near-infrared, optical, and UV imaging presented here. The features detected from IE imaging of the two galaxies are almost co-aligned with the radio-continuum contours, with a slight displacement in the case of MCG +07-07-070.

|

Fig. 4. Colour scale IE image of galaxy MCG +07-07-070 with the scaling set to highlight faint stripped features at the galaxy outskirts. Details are same as in Fig. 3. |

Contributions to radio continuum emission can come from physical mechanisms other than star formation van Weeren et al. 2019; Hardcastle & Croston 2020. These include past and recent activity from an active galactic nucleus (AGN) at the galaxy centre, as well as radio relics from recent mergers found within the galaxy cluster. The presence of an AGN can produce jets and create lobe-like features detectable in LOFAR 144 MHz radio continuum imaging. According to the WHAN diagram Cid Fernandes et al. 2011, which combines the equivalent width (EW) of the Hα emission line with the emission line ratio EW(N II)/EW(Hα), UGC2665 is classified as having a weak AGN, with an energy budget insufficient to produce jet/lobe-like features Meusinger et al. 2020. Another possibility is radio relics from cluster mergers that can be detected through radio continuum imaging. The orientation and appearance of the radio continuum contours are more likely to be associated with galaxies than with the cluster. The radio continuum emission is therefore associated with the stripped tails of the galaxy and traces cosmic ray electrons accelerated by supernovae. Cosmic ray electrons in the stripped tails can undergo synchrotron aging, characterised by a steep spectral index that can be flattened by the presence of star formation Roberts et al. 2022. The displacement of radio continuum contours from the features seen in IE imaging for MCG +07-07-070 can be explained by the detection of regions with steep spectral index in 144 MHz radio continuum imaging. The radio mini-halo detected around NGC 1275, the central cluster galaxy, at 144 MHz overlaps with UGC 2665, which can also contribute to radio continuum emission detected from the RPS tail of the galaxy Roberts et al. 2022.

The correspondence between the broadband optical emission from these features and the presence of a radio continuum tail strongly supports the RPS origin. First, the gas is stripped from the galaxy, forming extended tails where star formation occurs in situ, which is then visible as optical emission. The direction of the tails can indicate a ram-pressure origin, since galaxies falling into a cluster for the first time on radial orbits tend to have tails oriented opposite to their velocity vector. The orientation of the stripped tails can help in understanding the orbital dynamics of the galaxy within the cluster Smith et al. 2022; Salinas et al. 2024; George et al. 2024. However, this is complicated by the effect of galaxy rotation when moving at high speeds within the galaxy cluster environment.

3.1.5. Ram-pressure stripping as the dominant perturbing mechanism

In summary, we emphasise that the morphology of the features observed in Euclid imaging of both galaxies does not display any diffuse tidal tail or shells, which would be expected in recent gravitational perturbations, down to the limiting surface brightness of 30.1 mag arcsec−2 of Euclid IE (and similarly in the slightly shallower YE, JE, HE imaging). The features have a filamentary and clumpy structure, with a cometary shape, which is expected in star formation occurring in the tails of galaxies undergoing RPS. These features are extended and have a low surface brightness connection to the galaxy’s disc. In the case of MCG +07-07-070, the one-sided features from the galaxy’s disc resemble the fireballs detected in the stripped tails of galaxies in nearby clusters Yoshida et al. 2008; Hester et al. 2010; Yoshida et al. 2012; Smith et al. 2010; Kenney et al. 2014; Jáchym et al. 2014, 2019; Giunchi et al. 2023b. The two galaxies have also extended radio continuum tails of cometary shape that are co-aligned with the features detected in IE imaging. The radio continuum tails have the expected morphology of ram pressure stripping, where the stripped gas is displaced in the ICM, while the in situ formed stars are not affected. This is particularly clear in the case of MCG +07-07-070, where the radio continuum detected tail is displaced from the features detected through IE imaging. Galaxies experiencing their first infall should have stripped tails pointing away from the cluster centre, which can then be redirected towards the centre after a pericentre passage. We observe that the tail of UGC 2665 is oriented away from the cluster centre, whereas the tail of MCG +07-07-070 is oriented towards the cluster centre, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. As demonstrated in Table 2, the location of both galaxies in the Perseus cluster is far enough from the centre to avoid gravitational perturbations from the cluster potential, and ram pressure dominates over the gravitational anchoring forces of the cold gas, which can potentially strip the gas. Theoretical arguments, supported by observational evidence from Euclid and multi-wavelength data from UVIT, CFHT Hα, and LOFAR, suggest that the two galaxies are currently experiencing a RPS event. Still, the effect of gravitational interactions in the past with other galaxies cannot be fully ruled out. Such an interaction can perturb the gas content of the galaxy, loosening the tightly bound disc gas, thereby making the RPS process more efficient Cortese et al. 2021.

3.2. Ram-pressure stripping in optical and near-infrared imaging

Having established the ram-pressure origin of the features seen in the Euclid imaging data of the two galaxies, we then conducted a combined analysis of the stripped tails of the galaxies using both optical (IE) and near-infrared (YE) imaging data. The colour composite images of the galaxies, created from optical and infrared imaging shown in Figs. 1 and 2, display filamentary dusty and stellar structures escaping from their stellar discs, similar to those observed in a few cluster objects with available HST data Kenney et al. 2015; Abramson et al. 2016; Cramer et al. 2019. Next we discuss the morphological features detected in the Euclid imaging for bothgalaxies.

UGC 2665 is a spiral galaxy, morphologically classified in NED as Scd, which lacks a bulge. The galaxy is observed almost edge-on, with a measured axis ratio of 0.444 from IE imaging, corresponding to an inclination of ∼64° Cuillandre et al. 2025a. The galaxy displays features suggesting star formation is occurring in the stripped tail, visible in an edge-on direction. There are features in the galaxy that are due to dust lanes. The dust lanes on the galaxy disc are visible in IE imaging, but not in YE and HE imaging, as shown in the colour composite image in Fig. 1. The dust present in the galaxy disc can also be stripped along with the gas. There are knots that appear to emanate from the spiral arms but are superimposed on the galaxy’s disc due to projection. The features outside the galaxy close to the disc are clumpy, elongated, and follow the direction of stripping.

Parameters used for SourceXtractor++ run of u, IE, YE, JE, HE images of the two galaxies.

The galaxy displays a distinct “unwinding” effect in the outer spiral arms of the disc, as shown in Fig. 5. This is an effect observed in several RPS galaxies in the literature, both in observations Bellhouse et al. 2021; Vulcani et al. 2022 and simulations Schulz & Struck 2001; Roediger et al. 2014; Steinhauser et al. 2016. To better visualise the effect of ram-pressure on the spiral arms of the galaxy, the IE image of the galaxy is reprojected into polar coordinates, with radial distance from the galaxys’ centre (r) and azimuthal angle around the disc (θ) in the plane of the galaxy. The galaxy is corrected for inclination using the axial ratio from IE imaging, by scaling the distances along the dimension of the minor axis. Each pixel is reprojected into polar coordinates according to its radial distance and azimuthal position. To preserve the area of each pixel in polar space, the reprojection is carried out for each corner of the pixel individually, mapping the shape of each pixel from a square in the cartesian image plane to a polygon in polar coordinates. This is particularly important in regions close to the galactic centre, where some pixels span a large range of azimuthal angles. The left panel of the figure shows the galaxy “unwrapped” in polar coordinates, whilst the right panel shows the original image. On the left-hand panel, logarithmic spiral arms have been drawn to highlight the prominent dust lanes. These spiral arms are shown reprojected back onto the galaxy disc on the right panel. The pitch angle (the angle between a spiral arm and the tangent to the circle on the plane of the disc) can be used as a measure of the tightness of the spiral arm. The pitch angle, ∼0, lies along the tangent, while 90° lies along the normal; tightly wound spiral arms have lower pitch angles, and steeper, more loosely wound spiral arms have higher pitch angles. The median pitch angle of the most prominent spiral arms in the galaxy is ∼22° within 2× the effective radius of the disc (marked by the dashed line/ellipse in Fig. 5), and ∼39° outside this radius. Higher pitch angles in the outer regions of the disc compared with the inner disc suggest that the spiral arms are effectively being unwound. In the trailing region of the galaxy’s disc, the spiral arms are extremely extended, and they become steeper towards the outskirts of the disc and tails. As demonstrated by simulations in Bellhouse et al. 2021, this is consistent with ram-pressure “unwinding” the gas component of the spiral arms. The stars formed in situ outside the galaxy’s disc exhibit a steeper pitch angle than those formed within the disc, yet still maintain the general shape of the spiral arms. The presence of this pattern further confirms the RPS operating in this galaxy. The pattern and amount of unwinding in this galaxy suggest that it is consistent with ram-pressure stripping, as seen in galaxies confirmed by integral-field spectroscopy, and that gravitational processes are not necessary to explain the curved tails. Furthermore, the presence of unwinding in this manner tells us that the galaxy is likely to be in an early stage of infall. According to Bellhouse et al. 2021, the visual unwinding stage is relatively short-lived, lasting up to 0.5 Gyr before the pattern is washed out by the ICM wind into the tail of the galaxy.

|

Fig. 5. Left panel: IE image of UGC 2665 galaxy “unwrapped” in polar coordinates in terms of radial distance from the centre of the galaxy (r) and azimuthal angle around the disc (θ). Right panel: Original image in greyscale. Logarithmic spiral arms have been drawn on the left-hand panel on the prominent dust lanes in cyan colour crosses. Spiral arms are shown projected back onto the galaxy disc on the right panel. |

The unique, low surface brightness optimised imaging data from Euclid allowed us to explore stripped tails at faint levels. We performed a morphological analysis of the low surface brightness features observed along the stripped tails using optical, near-infrared, and other wavelength imaging data. Euclid IE imaging of the galaxy is used to construct a surface brightness map, with features associated with stripping marked in cyan boxes, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The stripped features in boxes 1 to 10, marked on the IE and YE images, are shown in detail in Figs. 6 and 7. The RPS features seen in IE imaging are seen in YE imaging as well, though at a slightly lower spatial resolution. Figure 3 shows the overlaid contours of ultraviolet, Hα and 144 MHz radio continuum. The Hα emission clearly displays a stripping pattern, with the emission from the bright features outside the galaxy detected in IE imaging. Hα emission in star-forming regions is due to the recombination of hydrogen that is ionized by O and early-B stars with ages ≤ 10 Myr Kennicutt 1998; Kennicutt & Evans 2012. The NUV N245M contours appear to cover the detected features, suggesting the presence of very recent star formation (with ages ≤ 200–300 Myr) in the stripped tails. The NUV flux is coming from the photospheres of A–F spectral type stars with age ∼ 300 Myr Boselli et al. 2009. The Hα and NUV N245M regions exhibit a spatial correlation, indicating very recent star formation (less than 10 Myr) in these areas. We note that the Hα and NUV imaging is at a different depth compared to Euclid, and therefore, we do not make any claims about the features detected along the low surface brightness tails. Radio continuum contours clearly reveal the morphology of the gas in the galaxy’s disc and the intracluster medium, with prominent cometary tail features indicative of RPS. The feature highlighted in box 10 is the farthest from the disc and is likely associated with the RPS of the galaxy. Note that the bright streaks in box 10 are due to a foreground nearby bright star in the field. Diffuse emission and clumpy features are observed in the direction of stripping, prominently seen in boxes 1 to 10.

MCG +07-07-070 is a peculiar galaxy classified in NED as SBR(pec). The galaxy is seen face-on with a measured axis ratio of 0.721 from IE imaging that corresponds to an inclination of ∼43°. The stripped material in MCG +07-07-070 is oriented towards the centre of the cluster, as seen in projection, which suggests it may be moving away from the cluster centre after a recent pericentric passage. The features are marked in cyan boxes numbered 1 to 16 in the IE image of the galaxy, as shown in Fig. 4. The galaxy IE image is overlaid with Hα and 144 MHz radio continuum contours. The NUV N245M contours are confined to the galaxy’s disc in projection, as is the Hα, except for a few regions on the stripped tail ends. The faint features outside the disc of the galaxy do not show NUV N245M and Hα emission. The Hα morphology in the disc appears truncated with respect to that of the underlying stellar disc. Star-formation truncation is an aftereffect of RPS, where the outer disc gas is stripped, leaving the gas confined to the central regions, hosting star formation. Koopmann & Kenney 2004a,b; Koopmann et al. 2006; Boselli & Gavazzi 2006; Cortese et al. 2012; Fossati et al. 2013; Fritz et al. 2017; Vulcani et al. 2020. The RPS scenario is expected to cause a stronger truncation of Hα than NUV because the stripping occurs from the outside in. If there is an age effect, between 10 and 100 Myr after the start of the stripping, the Hα disc will be completely truncated, while the NUV disc will only be marginally affected Boselli & Gavazzi 2006. Mondelin et al. 2025 provide more details on the truncation occurring in these galaxies based on the ERO of the Perseus field. We note that MCG +07-07-070 Hα observations can be affected by the galaxy’s peculiar velocity, such that the Hα filter does not completely cover the emission line. Radio continuum contours show the cometary tail features expected from RPS and are slightly displaced from the features seen in IE imaging. The stripped features from the IE images are shown in detail in Fig. 8 and shown for the YE image in Fig. 9. The features exhibit a “fireball” structure (see Appendix for a description of this scenario), characterized by head clumps at the leading edge and diffuse emission at the trailing edge. The orientation of the stripping with respect to the line of sight likely explains this pattern, with the diffuse emission revealing the extent of star formation within the tails. The features marked with arrows in boxes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, and 12 are not all parallel, as expected when the galaxy rotates while moving within the cluster. The stripped tail direction represents the composite vector of the stripping direction and the galaxy’srotation.

|

Fig. 6. Zoom-in on the IE imaging of stripped features for UGC 2665 galaxy. These correspond to the boxes marked in Fig. 3. Each box has a size of 5.1 kpc × 4.4 kpc with the arcsec bar shown corresponding to 338 pc at cluster frame. The details of markers are as in Fig. 3. Contours corresponding to the boundaries of the segments detected from IE image in section 3.3 are overlaid. |

|

Fig. 7. Zoom-in on the YE band imaging of stripped features for UGC 2665 galaxy. These correspond to the boxes marked in Fig. 3. Each box has a size of 5.1 kpc × 4.4 kpc with the arcsec bar shown corresponding to 338 pc at cluster frame. The details of markers are the same as in Fig. 3. Contours corresponding to the boundaries of the segments detected from YE image in Section 3.3 are overlaid. |

|

Fig. 8. Zoom-in on the IE imaging of stripped features for MCG +07-07-070. These correspond to the boxes marked in Fig. 4. Each box is having a size of 5.1 kpc × 4.4 kpc with the arcsec bar shown corresponding to 338 pc at cluster frame. The details of markers are the same as in Fig. 4. Contours corresponding to the boundaries of the segments detected from IE image in Section 3.3 are overlaid. |

|

Fig. 9. Zoom-in on the YE band imaging of stripped features for MCG +07-07-070. These correspond to the boxes marked in Fig. 4. Each box has a size of 5.1 kpc × 4.4 kpc with the arcsec bar shown corresponding to 338 pc at cluster frame. The details of markers are the same as in Fig. 4. Contours corresponding to the boundaries of the segments detected from YE image in Section 3.3 are overlaid. |

In general, we detected the features seen in the IE imaging, albeit at a slightly lower resolution, in the YE imaging of the two galaxies. The near-infrared emissions from the galaxies are dominated by an old-evolved population of stars. However, this is not the case for stripped tails, which can include contributions from the stellar continuum of cool main-sequence stars and red supergiants that have recently left the massive end of the main sequence. We demonstrate this in the next section based on colour information derived from the Euclid optical and near-infrared imaging data. We note that the morphology of the optical and near-infrared detected features is very similar, with the peak emission from the knots coinciding.

3.3. Surface brightness of stripped features: Optical, near-infrared analysis

Euclid imaging is optimized for high angular resolution and low surface brightness, enabling the detection of a larger extent of features created by RPS. We detected these features with SourceXtractor++Bertin et al. 2020; Kümmel et al. 2022. This new and extended implementation of a source detection algorithm has the advantage of performing photometric measurements in multiple bands based solely on the World Coordinate System, unlike SExtractor2Bertin & Arnouts 1996, which requires alignment of all measurement images.

To compute the surface brightness of the stripped features, we made independent SourceXtractor++ runs on the IE, YE, JE, and HE images. Table 3 gives details on the parameters used for the run. As discussed in Cuillandre et al. 2025a, these ERO images have already had their backgrounds removed.

-

We verified that the images used in this analysis have a reasonable background subtraction in our regions of interest and decided not to perform additional background determination.

-

We used the associated weight image for detection and photometry in each band.

-

We optimized the detection result with the built-in detection filter [2.0 pixel full width half maximum (FWHM)].

-

We selected the detection threshold and minimum area in each band independently to keep the false positive detection rate low (< 1.0%). We note that this is different for the two galaxies in NISP bands.

The average surface brightness distribution of the stripped features were then computed using the auto_mag brightness, which is measured in an elliptical aperture derived from the object’s surface brightness distribution, and the segmentation area, which is the area above the detection threshold.

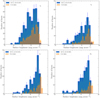

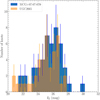

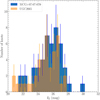

We utilised the segmentation map from the IE image, which is deeper than near-infrared images, to isolate the features associated with stripping. The features associated with stripping are identified by visually inspecting the segmentation map overlaid on the IE images of the two galaxies. These are the features that appear in the marked cyan boxes shown in Figs. 3 and 4. We note that this process is done visually and may leave behind faint, irregular, and distant galaxies, contaminating the detection of genuine features. We checked the possibility of contamination by computing the number density of objects within the limiting magnitude of the detected knots in IE, YE, JE, and HE band images of the galaxies. We calculated the number density, measured in objects/arcmin2, within the boxes marked along the tails of the galaxies in Figs. 3 and 4, as well as in a few regions away from the galaxy. The number density is found to be 3.6/2.2/2.2/1.9 times higher along the stripped tails of UGC 2665 and 4/3.16/2/2.1 times higher along the stripped tails of MCG +07-07-070 in IE/YE/JE/HE bands. This suggests that objects cluster along features in the boxes, which are very likely part of the stripped tails. However, a robust confirmation requires spectroscopic redshift information. We selected those features that show diffuse emission associated with stripping. We excluded stars and features that have the morphology of a likely background galaxy from the selection. After measuring the surface brightness of stripped features from IE images of the galaxies, we created segmentation maps for stripped tails independently using YE, JE, and HE imaging data. The distribution of surface brightness of the features is shown in Fig. 10. The limiting surface brightness of these features changes with the imaging band which in turn is dependent on the sensitivity of the imaging data. Table 4 gives the number of detected segments associated with the stripped features of the two galaxies.

|

Fig. 10. Distribution of surface brightness of segments from the stripped tails detected from IE, YE, JE, HE images of UGC 2665 and MCG+07−07−070. Poisson errors are shown with an error bar. |

Number of the features detected independently from IE, YE, JE, HE images of the two galaxies.

Table 5 lists the surface brightness and corresponding area of the faintest feature detected for two galaxies. We note that the faintest features have a surface brightness of 25.17 mag arcsec−2 for MCG +07-07-070 and UGC 2665, as seen in IE imaging. The surface brightness changes to 25.17 mag arcsec−2 for MCG +07-07-070 and 25.36 mag arcsec−2 for UGC 2665 based on HE imaging data. To better understand the nature of the selected features, we provide the segmentation map of these features, detected independently from the IE imaging in Figs. B.1 and B.2 and at a NISP resolution in the YE imaging of the two galaxies in Figs. B.3 and B.4. We also overlay the contours corresponding to the boundaries of the segments in Figs. 6, 7, 8 and 9. Our goal here is to determine the faintest features that can be resolved within the stripped tails with Euclid imaging. This information can be used to plan for the study of stripped features from Euclid DR1 imaging data.

Surface brightness and the corresponding area of the faintest features detected from IE,YE,JE,HE images of the two galaxies.

3.4. Optical, near-infrared colour of the stripped features

We measured the Euclid colour of the low surface brightness clumpy features detected for the two galaxies. Measuring object colours in imaging data with large differences in resolution and pixel scales requires special attention. SourceXtractor++ projects the elliptical apertures determined on the detection image onto the other measurement images, measuring the brightness of the objects within. The image with the lowest resolution is used as the detection image, which allows the flux of each object to be measured in the same sky area for the better-resolved bands, thereby largely eliminating the impact of resolution on photometry. We used HE as the detection band to measure the colours of the stripped features in the Euclid bands.

We removed contamination from foreground stars after matching the position of knots with the Gaia DR3 catalogue of stars in the field. We note that the limiting magnitude for GaiaG is ∼ 21 in the regions of the galaxies, where the Perseus ERO has a point source depth with a 5σ PSF magnitude of 28.0, 25.2, 25.4, and 25.3 in IE, YE, JE, and HE, respectively and with the exceptional angular resolution in IE star complexes down to the scales of 50 pc can be resolved. This suggests that fainter stars may be present in these fields, detectable through Euclid imaging, which could potentially contaminate the detected features. The extinction due to MilkyWay in the direction of the galaxies is computed for each band using the procedure described in Cuillandre et al. 2025a. The colours computed for these features are then used to constrain the age of the underlying stellar population in the stripped tails. We quantify the resolved knots found in the low surface brightness features identified from the segmentation map. We consider these knots, which lack redshift information, to be in situ star-forming regions, as they fall on low surface brightness stripped features. Additionally, the regions are also covered by the emission detected through UVIT NUV narrowband imaging, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

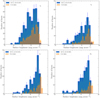

The zoom-in IE images show that the

identified knots have diffuse emission associated with them in the direction of stripping. These knots are selected from the regions outside the galaxy in the direction of stripping. Knots that appear

to follow the stripping pattern are visible in projection, overlapping with the galaxy’s disc. This is particularly true of UGC 2665, and we exclude these knots from consideration due to their susceptibility to contamination from the galaxy’s disc flux. The selected knots on the stripped tails of the galaxies are used to construct a Euclid colour-colour diagram. Figures 11 and 12 show the colour-colour plots of the detected knots in UGC 2665 (green) and MCG +07-07-070 (grey), created using IE−YE, YE−HE, and YE−JE colour combinations. We only show the knots that exceed the resolution limit ( ) of the HE imaging data, with a 3σ detection. There are 37 knots detected for UGC 2665 and 138 knots detected for MCG +07- 07-070. The colour values for single stellar populations of ages ranging from 0 to 300 Myr were generated using Bruzual & Charlot 2003 stellar population models (BC03), Padova 94 isochrones, and a Kroupa initial mass function (IMF, Kroupa 2001), for solar metallicity, corresponding to a redshift of 0.01, are overlaid. The corresponding age range (< 300 Myr) is shown in the colour bar scale and the colour distribution of the knots is shown in the side panels. The measured flux from these knots can be affected by extinction due to dust within the system and in the foreground from the Galaxy. We performed MilkyWay extinction correction for the magnitude values, but the intrinsic extinction can affect these colour values plotted here. The modeled colour values for different stellar population ages exhibit non-monotonous behaviour, mainly because integrated stellar population colours shift to blue before the first massive stars become red supergiants (which takes about 10 Myr), then to the very red colours of red supergiant dominated populations, and later to slightly less red colours when these supergiants become less luminous. The rotation of massive stars also affects this, as it determines the coolest temperature a star of a given mass can reach, and additionally, the spectra of massive stars are uncertain. This makes it difficult to estimate the ages of the underlying stellar population from Euclid colour-colour plots alone. However, as we demonstrate here, we can determine whether the colours are compatible with a young age across an age/metallicity range. The IE bandpass covers a broad wavelength range, which is sensitive to spectral energy variations for different stellar population ages. We could effectively discriminate the contribution of different age stellar populations to the spectral energy distribution by using u, g, i, z imaging data. The resolution of the CFHT data is lower than that of the Euclid imaging data. We used the u band image with the lowest resolution of