| Issue |

A&A

Volume 702, October 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A240 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556777 | |

| Published online | 24 October 2025 | |

The impact of axion-like particles on late stellar evolution

From intermediate-mass stars to core-collapse supernova progenitors

1

Departamento de Física Teórica y del Cosmos, Universidad de Granada, E-18071 Granada, Spain

2

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico d’Abruzzo, Via Mentore Maggini snc, 64100 Teramo, Italy

3

INFN – Sezione di Roma, Piazzale Aldo Moro 2, I-00185 Roma, Italy

4

Centro de Astropartículas y Física de Altas Energías (CAPA), Universidad de Zaragoza, Zaragoza 50009, Spain

5

Dipartemento Interuniversitario di Fisica “Michelangelo Merlin”, Via Amendola 173, I-70126 Bari, Italy

6

INFN – Sezione di Bari, Via Orabona 4, 70126 Bari, Italy

7

INFN – Sezione di Perugia, Via A. Pascoli, 06123 Perugia, Italy

⋆ Corresponding author: oscar.straniero@inaf.it

Received:

7

August

2025

Accepted:

24

August

2025

Context. Stars with masses ranging from 3 to 11 M⊙ exhibit multiple evolutionary paths. Less massive stars in this range conclude their evolution as carbon-oxygen (CO) white dwarfs (COWDs). However, stars that achieve carbon ignition before the pressure induced by the degenerate electron halts the core contraction would either form massive CONe or ONe WDs, or they might undergo an electron-capture supernova (ECSN). Alternatively, they could photo-disintegrate neon and proceed with further thermonuclear burning, ultimately leading to the formation of a gravitationally unstable iron core.

Aims. An evaluation of the impact of the energy loss caused by the production of axion-like-particles (ALPs) on the evolution and final destiny of these stars is the main objective.

Methods. We computed various sets of stellar models, all with solar initial composition, varying the strengths of the ALP coupling with photons and electrons.

Results. As a consequence of an ALP thermal production, the critical masses for off-center C and Ne ignitions are both shifted upward. When the current bounds for the ALP coupling strengths are assumed, the maximum mass for CO WD progenitors is about 1.1 M⊙ heavier than that obtained without the ALP energy loss, while the minimum mass for a core collapse supernova (CCSN) progenitor is 0.7 M⊙ higher.

Conclusions. Current constraints from observed type II-P supernova light curves and pre-explosive luminosity do not exclude an ALP production within the current bounds. However, the maximum age of CCSN progenitors, as deduced from the star formation rate of the parent stellar population, would require a lower minimum mass. This discrepancy can be explained by assuming a moderate extra mixing (as due to core overshooting or rotational induced mixing) above the fully convective core that develops during the main sequence.

Key words: astroparticle physics / elementary particles / stars: evolution / stars: interiors / supernovae: general

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

In this work, we revise existing models of single stars with masses in the range 3 < M/ M⊙ < 11, taking into account the effects of a possible thermal production of axions or (more generally) axion-like-particles (ALPs). In a previous paper, we discussed the impact of ALPs on the evolution of star with M > 11 M⊙ (Straniero et al. 2019a). More than two decades ago, the effects brought on by the plausible production of ALPs in intermediate-mass stars (3 < M/M⊙ < 7) were illustrated in the pioneer work by Dominguez et al. (1999).

Calculating stellar models for masses of 3–11 M⊙ is considerably more challenging than for higher masses, due to the possible ignition of carbon and neon in environments with high or moderate electron degeneracy (García-Berro et al. 1997; Ritossa et al. 1999; Doherty et al. 2015; Woosley & Heger 2015; Straniero et al. 2019b; Limongi et al. 2024). There are very different scenarios characterizing the late evolution of these stars. Intermediate-mass stars, namely, those that never achieve conditions for carbon burning, evolve through the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) and eventually they become carbon-oxygen white dwarfs (COWDs), which are the most common type of white dwarf (WD). When they are part of a close binary, these types of stars can accrete mass from a companion star and this accretion can trigger a variety of explosive phenomena, including cataclysmic variables, novae, and type Ia supernovae (SNIa). Therefore, the maximum mass of the COWD progenitors is a fundamental parameter in studies of population synthesis and galactic chemical evolution. After Becker & Iben (1979), it is often referred as Mup, but in this paper we prefer to use  . This choice is based on the reasoning that beyond this threshold, stars form a sufficiently massive carbon-oxygen (CO) core, enabling carbon ignition and the consignment production of oxygen and neon. A further contraction of the core may or may not allow the heating necessary to activate the photo-dissociation of Ne and the following chain of α, proton and neutron captures, at the end of which a iron-rich core will form (Woosley & Heger 2015; Straniero et al. 2019b; Limongi et al. 2024). This more advanced stage of the evolution may take place only if the CO core mass is above a critical value, roughly corresponding to theChandrasekhar mass limit. Indeed, in the case of a lower CO core mass, the concurrent action of pressure by degenerate electrons and plasma-neutrino cooling prevent the occurrence of a Ne burning. In practice, there is a subsequent critical stellar mass (hereinafter

. This choice is based on the reasoning that beyond this threshold, stars form a sufficiently massive carbon-oxygen (CO) core, enabling carbon ignition and the consignment production of oxygen and neon. A further contraction of the core may or may not allow the heating necessary to activate the photo-dissociation of Ne and the following chain of α, proton and neutron captures, at the end of which a iron-rich core will form (Woosley & Heger 2015; Straniero et al. 2019b; Limongi et al. 2024). This more advanced stage of the evolution may take place only if the CO core mass is above a critical value, roughly corresponding to theChandrasekhar mass limit. Indeed, in the case of a lower CO core mass, the concurrent action of pressure by degenerate electrons and plasma-neutrino cooling prevent the occurrence of a Ne burning. In practice, there is a subsequent critical stellar mass (hereinafter  ) above which stellar evolution proceeds up to the formation of a gravitationally unstable iron core (Woosley & Heger 2015; Limongi et al. 2024). The final destiny of these massive stars is determined by the collapse of the core, possibly followed by a supernova (SN). Accordingly, the remnant may be a neutron star or a black hole. Instead, stars with mass in the range

) above which stellar evolution proceeds up to the formation of a gravitationally unstable iron core (Woosley & Heger 2015; Limongi et al. 2024). The final destiny of these massive stars is determined by the collapse of the core, possibly followed by a supernova (SN). Accordingly, the remnant may be a neutron star or a black hole. Instead, stars with mass in the range  -

- skip the Ne-burning phase and enter the super-AGB phase. Depending on the mass-loss rate, which is expected to be quite strong along the super-AGB, the final destiny of these stars may be either a massive WD or an electron-capture supernova (ECSN). As for the less massive COWDs, accretion in binaries could also result in various explosive phenomena or, in the case of a pure oxygen-neon WD (ONeWD), an accretion-induced collapse (AIC) could occur, resulting in a WD to neutron star (NS) transition. Binary systems hosting accreting NSs are commonly observed as low-mass-X-ray binaries (LMXBs).

skip the Ne-burning phase and enter the super-AGB phase. Depending on the mass-loss rate, which is expected to be quite strong along the super-AGB, the final destiny of these stars may be either a massive WD or an electron-capture supernova (ECSN). As for the less massive COWDs, accretion in binaries could also result in various explosive phenomena or, in the case of a pure oxygen-neon WD (ONeWD), an accretion-induced collapse (AIC) could occur, resulting in a WD to neutron star (NS) transition. Binary systems hosting accreting NSs are commonly observed as low-mass-X-ray binaries (LMXBs).

In this paper, we discuss the influence of the possible production of ALPs in stellar interiors (and the consequent energy drain) on the values of the minimum stellar masses for carbon and neon burnings. In addition, we also show how this deviation from standard physics affects the second dredge-up and the critical mass, dividing stars into: those undergoing a complete C burning and those for which, following the off-center C ignition, the thermonuclear flame does not propagate inward down to the center. A pure ONe core forms only in case of a complete C burning, while an hybrid core (an inner CO core surrounded by an ONe mantel) is left if the C burning does not extend down to the center.

Axion-like particles (ALPs) emerge naturally in a wide variety of extensions to the standard model (SM) of particle physics (Jaeckel & Ringwald 2010; Ringwald 2014; Di Luzio et al. 2020; Agrawal et al. 2021; Giannotti 2023; Antel et al. 2023). These hypothetical pseudoscalar bosons are typically associated with the spontaneous breaking of approximate global symmetries and are characterized by their weak couplings and light masses. The most studied and theoretically motivated ALP is the QCD axion (Peccei & Quinn 1977b,a; Weinberg 1978; Wilczek 1978), originally proposed to solve the strong CP problem in quantum chromodynamics. While generic ALPs are not required to address this issue, they share many of the QCD axion’s properties and appear naturally in a wide range of well-motivated ultraviolet (UV) completions of the SM. From a top-down perspective, string theory compactifications predict the existence of a rich landscape of such particles (the so-called axiverse), which includes the QCD axion and an entire spectrum of ultralight ALPs spanning many orders of magnitude in mass (Arvanitaki et al. 2010; Cicoli et al. 2012, 2024). These ALPs are expected to couple feebly to photons, fermions, and gluons, leading to distinctive phenomenological signatures across a range of experimental frontiers. From a bottom-up approach, ALPs are of considerable interest due to their potential role in solving several open problems in cosmology and astrophysics. They are compelling dark matter candidates, particularly when taking the form of non-thermally produced cold relics via the vacuum realignment mechanism (Abbott & Sikivie 1983; Dine & Fischler 1983; Preskill et al. 1983; Arias et al. 2012; Adams et al. 2022). In addition, they could help explain a variety of longstanding anomalies in stellar evolution and other astrophysical observations (Giannotti et al. 2016a, 2017; Galanti et al. 2023). These include excessive energy losses in stars, unexplained features in WD cooling, and anomalous transparency of the Universe to high-energy photons. In this context, stars represent powerful laboratories for probing ALP properties. Stellar interiors host hot, dense plasmas where ALPs can be efficiently produced via processes such as the Primakoff effect, photon coalescence, or electron bremsstrahlung, depending on their couplings (Raffelt 1996, 1999). Once produced, ALPs escape the stellar interior essentially unimpeded, carrying away energy and thereby altering stellar lifetimes and evolutionary tracks. This sensitivity has led to some of the most stringent constraints on ALP couplings to photons and electrons, particularly from observations of horizontal branch (HB) stars, red giants (RGs), WDs, and SNe (see Caputo & Raffelt 2024; Carenza et al. 2025, for recent review). The study of axions and ALPs in stellar environments thus offers a unique and complementary window onto new physics beyond the SM. The interplay between theoretical developments and increasingly precise astrophysical measurements continues to sharpen our understanding of these elusive particles and their role in the cosmos.

ALPs are expected to affect astrophysical observations of stars in different evolutionary phases. A stringent constraint to the ALP-photon coupling have been obtained by Ayala et al. (2014) (see also Straniero et al. 2015), comparing R parameters1, as measured in a sample of galactic Globular clusters, with the corresponding theoretical predictions. For the strength of the ALP-photon coupling, they found gaγ < 6.5 × 10−11 GeV−1 at 95% CL. A slightly more stringent bound, gaγ < 5.8 × 10−11 GeV−1, has been obtained by the CAST collaboration (Altenmüller et al. 2024), as part of a search for solar axions. More recently, Dolan et al. (2022), analyzed a limited number of clusters for which R2 measurements are also available and reported an even more stringent bound for the axion-photon coupling (i.e., gaγ ≲ 0.47 × 10−10 GeV−12). However, due to the rapid acceleration of stellar evolution occurring after the central-helium exhaustion, the AGB phase is substantially short-lived. This results in a poor population of stars in this phase, which implies significant statistical fluctuations for R2. Constraints on the strength of the ALP-electron coupling gae have been obtained from the luminosity of the RGB tip of globular clusters (Viaux et al. 2013; Capozzi & Raffelt 2020; Straniero et al. 2020), from the period shift of pulsating WDs (Isern et al. 1992; Córsico et al. 2012; Kepler et al. 2021) and from the WD luminosity function (Miller Bertolami et al. 2014; Isern et al. 2018). From the luminosity of the RGB tip, in particular, we get gae < 1.5 × 10−13 (Straniero et al. 2020) and thanks to improved cluster distances (Baumgardt & Vasiliev 2021), we get gae < 0.95 × 10−13 (Carenza et al. 2025). Ultimately, a recent analysis based on Gaia-DR3 photometry and astrometry (Troitsky 2025) reported gae < 0.52 × 10−13 (95% CL). However, a detailed analysis of the overall error is missing from the cited work. In the present study, we have assumed values of the coupling strengths that are close to or lower than the current bounds.

The aim of the present work is not the revision of these limits, but an analysis of the impact they have on the evolution of intermediate to massive stars. In Sect. 2, we describe the main features of our stellar evolution code and its setup. In Sect. 3, the computational results are illustrated. In particular we will derive values of the critical masses, namely, the minimum mass for the second dredge-up ( ), the maximum mass for CO WD progenitors (

), the maximum mass for CO WD progenitors ( ), and the minimum mass for CCSN progenitors (

), and the minimum mass for CCSN progenitors ( ). A final discussion follows in Sect. 4.

). A final discussion follows in Sect. 4.

2. Stellar evolution code and its setup

All the models presented in this paper have been computed by means of the Full Network Stellar Evolution code (FuNS). The FuNS version here adopted is the one described in Sect. 2 of Straniero et al. (2019a). Due to their relevance for the interpretation of the values of the critical parameters determining the final destiny of stars, we provide a brief description of the main code settings on which our calculations are based. First, boundaries of the convective zones are fixed by means of the Ledoux criterion. Hence, no overshoot is applied to the external birder of the convective core that develops during the H-burning phase and no undershoot is considered at the inner border of the convective envelope during the red giant and asymptotic giant evolutionary phases. Concerning the He-burning phase, induced overshoot and semiconvection are applied according to the procedure described in Castellani et al. (1985). Moreover, sporadic breathing pulses are blocked as in Straniero et al. (2003). Nuclear reaction rates are from the STARLIB repository (Sallaska et al. 2013). In particular, the triple-α and the 12C+12C reaction rates are based on Caughlan & Fowler (1988) prescriptions, while the 12C(α, γ)16O reaction rate is based on deBoer et al. (2017). Eventually, effects of rotation are neglected. Noteworthy, for a given initial mass, this code setup results in a lower CO core mass than obtained when an “extra mixing” is applied at the external border of the convective core of an H burning star, as due to a convective overshooting or rotational induced mixing. On the other hand, due to the adopted treatment of He-burning semiconvection and the 12C(α, γ)16O reaction rate, a reduced C/O ratio (∼0.3) is left in the core after the central-He burning phase (see the discussion in Straniero et al. 2003).

In the present work, we aim to evaluate the impact of a possible ALPs production on the evolution of stars developing a degenerate CO core after the He-burning phase. Therefore, energy-loss rates were computed following the prescriptions reported in the appendix of Straniero et al. (2019a). ALP production via Primakoff effect, associated with photon-axion coupling gaγ, and Compton, Bremsstrahlung, and e−e+-annihilation, due to axion-electron coupling gae, were considered. ALPs are assumed massless, a valid approximation for ma < 10 keV. These energy-loss rates depend on the strengths of these interactions. In the following, we also make use of two dimensionless parameters: g10 ≡ gaγ/(10−10 GeV−1) and g13 ≡ gae/10−13. Current experimental and astrophysical constraints provides upper bound for these two parameters (see the introduction and Caputo & Raffelt 2024; Carenza et al. 2025, for more detailed reviews). To remain conservative, we considered bounds obtained from studies based on a detailed error budget analysis; in practice, this is g10 ≤ 0.6 and g13 ≤ 1.5 for the axion-photon and the axion electron couplings, respectively.

Thus, a large set of stellar evolutionary sequences was computed by adopting a solar chemical composition (Lodders et al. 2009), with Z⊙ = 0.014 and Y⊙ = 0.27. Mass was varied between 3 and 11 M⊙, in steps of 0.1 M⊙. Various couplings of ALPs with photons and electrons were assumed, namely: g10 = 0.0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 and g13 = 0.0, 1.5. Some additional models were also computed assuming a higher axion-electron coupling strength, namely, g13 = 4. All the evolutionary sequences starts from the pre-MS. For  the calculations was stopped at the onset of the first thermal pulse (AGB or super-AGB). For the more massive models, calculations were done until the shell-Si Burning.

the calculations was stopped at the onset of the first thermal pulse (AGB or super-AGB). For the more massive models, calculations were done until the shell-Si Burning.

3. Results

3.1. Stars that experience the second dredge-up, skip the C burning, and leave a COWD

According to existing stellar models, only stars that develop a CO core with mass exceeding a critical value, MCO ∼ 1.06 M⊙, attain the conditions for the C burning. In this context, the second dredge-up plays a fundamental role for the final destiny of intermediate-mass stars. When the central He is fully consumed, the CO core contracts and heats up, while its mass increases due to the helium burning in the overlying shell. Meanwhile, a deep convective envelope develops, whose lower boundary is limited by the presence of an active H-burning shell. In principle, the mass of the CO core could keep growing until the He-burning shell gets close to the base of the H-rich envelope. However, the rising energy flux from the He-burning shell induces an expansion of the overlying layers, so-that the H-burning shell cools down and, eventually, dies down, enabling the penetration of the external convection. This episode limits the growth of the CO core and marks the end of the early-AGB phase Becker & Iben (1979). As a result, the SDU prevents the carbon ignition in the core of intermediate-mass stars at 3 < M/M⊙ < 7. For instance, before the SDU, the He-rich core of a 6 M⊙ model is ∼1.31 M⊙. If the He-burning shell were free to advance up to the edge of this core, the final mass of the CO core would be much greater than the critical mass for carbon ignition. However, the SDU reduces the core mass down to ∼0.91 M⊙, thus preventing the carbon burning. In practice, the C burning may only occur when the He-burning shell attains the critical CO-core mass, MCO ∼ 1.06 M⊙, before the occurrence of the SDU, as it happens in more massive stars. Intermediate-mass stars are of pivotal importance for the galactic chemical evolution. After the SDU, they enter the thermal-pulse AGB phase, which is when the envelope is enriched with products of internal nucleosynthesis. Thus, the intense stellar winds from these stars provides a significant contribution to the chemical enrichment of the galactic gas. Their compact remnants, the CO WDs, are the major constituent of the baryon dark matter in the Milky Way. In addition, interacting binaries hosting CO WDs give rise to important explosive phenomena, among with cataclysmic variables, novae, and SNe Ia. For all these reasons, the determination of the mass range of these stars is a fundamental task of stellar astrophysics. Unfortunately, this mass range is rather uncertain. First of all, different assumptions about the efficiency of the convective-core overshoot or rotational-induced mixing during the H-burning phase lead to a variation of the relation between the initial mass and the resulting CO-core mass. Also the amount of C left by the He burning, which depends on the treatment of semiconvection and overshooting during the He-burning phase and on the rates of relevant nuclear reactions (the triple−α and the 12C(α, γ)16O, in particular) affects the conditions for the C ignition and, in turn, the value of the critical core mass. With the standard settings of the FuNS code illustrated in the previous section, we found a minimum stellar mass for the occurrence of the SDU MSDU = 4.3 M⊙3, corresponding to a CO core mass after the SDU of 0.82 M⊙. Instead, the more massive model in our sample that undergoes the SDU and skips the C burning is 7.4 M⊙, corresponding to a CO-core mass of 1.03 M⊙.

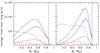

The inclusion of the energy loss possibly caused by a thermal production of ALPs affects both these mass limits. The energy-loss rates are steep functions of the temperature, so that the major influence of the ALPs production takes place during the He burning phase and beyond. Figure 1 shows the expected ALPS luminosity in a 7 M⊙ model for g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5. This choice of the couplings is representative of the current bounds. It results that the Primakoff process provides the major contribution to the energy loss. Noteworthy, the energy loss by ALPs is always greater than that by neutrinos. As a result, the He-burning lifetime is reduced and, in turn, the final He-core mass is lower, while the carbon abundance in the CO core is slightly larger. This energy loss continues during the early-AGB. Figure 2 reports the energy-loss rates of ALPs and neutrinos, in the core of the 7 M⊙ model, before and after the SDU. As expected, the ALPs production is more efficient near the border of the CO core, where the temperature attains a maximum value. Therefore, as already noted by Dominguez et al. (1999), the shell-He burning proceeds at a faster rate and the stops of the H-burning, which coincides with the SDU, is anticipated (see Fig. 3). As a consequence, the minimum SDU mass is lower than that obtained without ALPs, namely,  M⊙. This corresponds to a a CO core mass after the SDU of 0.73 M⊙. On the other hand, the more massive model that undergoes the SDU and skips the carbon burning has a larger mass, 8.5 M⊙, and a larger CO core mass, 1.09 M⊙.

M⊙. This corresponds to a a CO core mass after the SDU of 0.73 M⊙. On the other hand, the more massive model that undergoes the SDU and skips the carbon burning has a larger mass, 8.5 M⊙, and a larger CO core mass, 1.09 M⊙.

|

Fig. 1. Left panel: Evolution of the ALP and neutrino luminosities through the late portion of the He-burning phase and the subsequent early-AGB. Right panel: Evolution of the contributions to the ALP luminosity of the different production processes. The plots refers to the 7 M⊙ model with g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5. |

|

Fig. 2. Energy-loss rates due to ALPs production within the core of a 7 M⊙ with g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5. The left and the right panels refer to the two blue points in Fig. 3, as taken before and after the SDU, respectively. The solid-black line is the total ALP energy-loss rate, while the blue, the red, and the magenta lines represent the contributions of the Primakoff, Compton, and Bremsstrahlung processes, respectively. For comparison, the neutrino energy-loss rate is also reported (black-dashed line). |

|

Fig. 3. ALP impact on the SDU. Black lines (top to botton): Inner border of the convective envelope, location of the H-burning shell and location of the He-burning shell, for a 7 M⊙ (no ALPs), during the early-AGB phase; red lines (top to bottom): same as the black lines, but with g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5. The filled circles represent the He-shell locations for the two models in Fig. 2. |

It is noteworthy that the energy loss induced by an ALPs production reduces the stellar lifetime. In particular, a faster He consumption takes place during the He-burning phase. As a result, the ALP inclusion allows the production of the more massive CO WDs in a shorter timescale, up to ∼ − 25% (see Table 1). This occurrence have interesting implications, such as a shorter delay time for the onset of the first SNe Ia.

Impact of ALPs on the minimum mass for off-center C ignition.

3.2. Off-center carbon ignition in a degenerate CO core

When the ALPs production is neglected, the CO core mass of models with M ≥ 7.5 attains the critical value for the C burning before the occurrence of the SDU. In the 7.5 M⊙ model, an off-center C ignition takes place where the maximum in the temperature profile is attained, namely, at mr = 0.867 M⊙, within a CO core of 1.064 M⊙4. At the ignition point, the temperature and the density are 618 MK and 9.47 × 105 g/cm3, respectively. As noted since the pioneering work of Becker & Iben (1979), the critical CO core mass depends on several physics inputs, among which the adopted nuclear reaction rates are the most relevant. Nonetheless, Becker & Iben (1979) derived a critical CO core mass MCO = 1.06 M⊙, practically the same result as the one we have found more than 40 years later.

As the stellar mass increases, the C-ignition occurs closer to the center. Then, after the off-center ignition, a convective shell develops. Later on, the C burning moves inward through a series of progressively more internal C flashes. However, in models with mass between 7.5 and 7.7 M⊙ the C burning extinguishes before reaching the center, thereby leaving behind an unburned CO core surrounded by an ONe-rich mantel. Later on, these stars enters the super-AGB phase, during which they are expected to lose the H-rich envelope, leaving behind an hybrid WD made up of a CO core surrounded by a O-Ne mantel, whose mass ranges between 1.07 and 1.1 M⊙. An example is reported in Fig. 4, where the three panels show the density, temperature, and chemical composition profiles within the core of a 7.7 M⊙ model entering the super-AGB phase. Owing to the sharp chemical gradient at the CO-ONe interface, a diffusive mixing of the core and the mantel material likely will occur. In case of accretion from a companion star in a binary system, these hybrid WDs may approach the Chandrasekhar-mass limit. Hence, the unburned carbon within the core may trigger a thermonuclear explosion, rather than a core collapse.

|

Fig. 4. Top to bottom: Density, temperature, and chemical profiles within the core of a 7.7 M⊙ model at the onset of the super-AGB phase. In the bottom panel, lines represent the mass fractions of 4He (green), 12C (black), 16O (red), 20Ne (blue), and 24Mg (magenta). No ALP production has been included in this model. We note that it is only above 0.85 M⊙ that C burning has been active. This model represents an example of hybrid WD progenitors. |

A complete C burning occurs in models with M ≥ 7.8 M⊙. The development of the convective shells driven by the various C-flashes in the 9 M⊙ model is illustrated in Fig. 5. The first C ignition occurs at mr ∼ 0.15 M⊙. Suddenly a convective shell develops that extends up to mr ∼ 0.7 M⊙. Then, as C is consumed, the convective shell shrinks and, eventually, disappears. The consequent contraction induces a second C flash, at mr ∼ 0.11 M⊙, coupled to a new convective shell partially overlapping the previous one. Later on, the inner border of this convective shell moves slowly inward, until a central C burning sets in, followed by a series of three weaker and more external C flashes. The resulting core composition is shown in the lower panel of Fig. 6.

|

Fig. 5. Kippenhahn diagram of the degenerate C burning in the 9 M⊙ stellar model. The red region represents the convective envelope, while the violet regions are convective C-burning episodes. The t = 0 point is arbitrary. Note: the SDU occurs after the first C flash. |

|

Fig. 7. As in Fig. 4, but for a 8.6 M⊙ model (g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5). Only above 0.4 M⊙ the C burning has been completed. |

As illustrated in the previous section, the ALPs production moves both  and the corresponding MCO upward. The values of the critical masses, obtained under different assumptions about the strengths of the ALP couplings with photons and electrons, are reported in Table 1. The total stellar lifetime and the central C mass fraction after the He-burning phase are also shown. When only the axion-photon coupling is considered (i.e., g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 0),

and the corresponding MCO upward. The values of the critical masses, obtained under different assumptions about the strengths of the ALP couplings with photons and electrons, are reported in Table 1. The total stellar lifetime and the central C mass fraction after the He-burning phase are also shown. When only the axion-photon coupling is considered (i.e., g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 0),  is 8.4 M⊙, which corresponds to a CO-core mass 1.095 M⊙. In this case, the C ignition occurs at a mass coordinate mr = 0.66 M⊙, where T = 630 MK and ρ = 3.02 × 106 g/cm−3, both higher than the values obtained without ALPs. When the coupling with electrons is also switched on (i.e., g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5), the critical mass rises at

is 8.4 M⊙, which corresponds to a CO-core mass 1.095 M⊙. In this case, the C ignition occurs at a mass coordinate mr = 0.66 M⊙, where T = 630 MK and ρ = 3.02 × 106 g/cm−3, both higher than the values obtained without ALPs. When the coupling with electrons is also switched on (i.e., g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5), the critical mass rises at  M⊙, while MCO = 1.104 M⊙. In this case, the C ignition occurs at mr = 0.66 M⊙, where T = 632 MK and ρ = 2.94 × 106 g/cm−3.

M⊙, while MCO = 1.104 M⊙. In this case, the C ignition occurs at mr = 0.66 M⊙, where T = 632 MK and ρ = 2.94 × 106 g/cm−3.

In addition to the increase of  , the ALPs production also implies a higher minimum CO core mass for the C ignition (see Table 1). This is a direct consequence of the additional energy loss in the CO core of a star approaching the C ignition, only partially counterbalanced by the slightly higher C mass fraction left in the core after the He burning (see the last column in Table 1).

, the ALPs production also implies a higher minimum CO core mass for the C ignition (see Table 1). This is a direct consequence of the additional energy loss in the CO core of a star approaching the C ignition, only partially counterbalanced by the slightly higher C mass fraction left in the core after the He burning (see the last column in Table 1).

As for the SMs, C burning does not extend down to the center for models with masses that are slightly above  . In particular, if g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5, an incomplete C burning occurs for masses between 8.6 and 8.8 M⊙ (see Fig. 7).

. In particular, if g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5, an incomplete C burning occurs for masses between 8.6 and 8.8 M⊙ (see Fig. 7).

In Fig. 8, the variation of  is shown in the two-parameter space, (g13.g10). The shaded-blue band represents the g10 values excluded by the CAST helioscope measurements (Altenmüller et al. 2024). For comparison, the expected sensitivities of BabyIAXO and IAXO are also reported (Ahyoune et al. 2025; Abeln et al. 2021; Armengaud et al. 2014; Giannotti et al. 2016b; Armengaud et al. 2019). Practically, if the coupling of ALPs to electrons is negligible, the bound derived from CAST excludes the possibility that the axion-photon coupling could enhance

is shown in the two-parameter space, (g13.g10). The shaded-blue band represents the g10 values excluded by the CAST helioscope measurements (Altenmüller et al. 2024). For comparison, the expected sensitivities of BabyIAXO and IAXO are also reported (Ahyoune et al. 2025; Abeln et al. 2021; Armengaud et al. 2014; Giannotti et al. 2016b; Armengaud et al. 2019). Practically, if the coupling of ALPs to electrons is negligible, the bound derived from CAST excludes the possibility that the axion-photon coupling could enhance  above ∼8.4 M⊙. More stringent limits will be achieved by Baby-IAXO and subsequently by IAXO.

above ∼8.4 M⊙. More stringent limits will be achieved by Baby-IAXO and subsequently by IAXO.

|

Fig. 8. Contours of Δ |

3.3. Off-center Ne ignition and core-collapse SNe progenitors

As in the case of C burning, there is a minimum core mass above which the temperature increases enough to switch on the Ne photodisintegration through the 20Ne(γ, α)16O reaction. Stars that undergo a complete C burning (where the ONe core mass ends up lower than this threshold) enters the super-AGB phase, when an intense super-wind erodes the H-rich envelope. In principle, the core mass can grow during this evolutionary phase and eventually it might approach the Chandrasekhar limit. In this case, a core collapse would occur followed by a supernova (i.e. ECSNe). However, many of these stars likely leave the super-AGB before this condition is attained, ending up as an ONe WD with mass between 1.15 and 1.35 M⊙. In close binaries, these WDs can accrete mass, giving rise to Nova-like phenomena or they might even undergo an accretion-induced collapse (AIC).

More massive stars develop core masses above the threshold of Ne photodisintegration. According to current models, they are expected to complete all nuclear burnings up to the formation of an iron-rich core core (e.g., Woosley & Heger 2015; Straniero et al. 2019a; Limongi et al. 2024). Then, the iron core will collapse and a classical CCSNe could occur.

When the ALP cooling was neglected, we found that the minimum stellar mass igniting Ne is  M⊙. In this case, the Ne-ignition occurs at a mass coordinate of 0.86 M⊙, within an ONe core of 1.378 M⊙ and a CO core of 1.393 M⊙. The off-center Ne burning begins with the endothermic 20Ne(γ, α)16O reaction and proceeds with a chain of α and proton captures, while the inverse processes become increasingly efficient as the temperature rises. Meanwhile, the burning flame moves slowly inward. For comparison, Limongi et al. (2024) found

M⊙. In this case, the Ne-ignition occurs at a mass coordinate of 0.86 M⊙, within an ONe core of 1.378 M⊙ and a CO core of 1.393 M⊙. The off-center Ne burning begins with the endothermic 20Ne(γ, α)16O reaction and proceeds with a chain of α and proton captures, while the inverse processes become increasingly efficient as the temperature rises. Meanwhile, the burning flame moves slowly inward. For comparison, Limongi et al. (2024) found  M⊙. Their M = 9.3 M⊙ model, in particular, is the most similar to our 9.7 M⊙. At the Ne ignition, the ONe and the CO cores of this Limongi et al. (2024) model are, respectively, 1.367 and 1.382 M⊙. The difference in the minimum Ne burning mass may be likely ascribed to the inclusion in Limongi et al. (2024) of a core overshoot during the H-burning phase and to the algorithm they use to damp breathing pulses appearing during the late part of the He-burning phase. In practice, at the onset of C burning, the central C mass fraction is ∼0.4 in the Limongi et al. (2024) model, which is about double what we find. Figure 9 shows the density, temperature, and chemical profiles, within the core of a 10 M⊙ model during the advanced burning phases, when the thermonuclear flame triggered by the Ne photodisintegration moves inward.

M⊙. Their M = 9.3 M⊙ model, in particular, is the most similar to our 9.7 M⊙. At the Ne ignition, the ONe and the CO cores of this Limongi et al. (2024) model are, respectively, 1.367 and 1.382 M⊙. The difference in the minimum Ne burning mass may be likely ascribed to the inclusion in Limongi et al. (2024) of a core overshoot during the H-burning phase and to the algorithm they use to damp breathing pulses appearing during the late part of the He-burning phase. In practice, at the onset of C burning, the central C mass fraction is ∼0.4 in the Limongi et al. (2024) model, which is about double what we find. Figure 9 shows the density, temperature, and chemical profiles, within the core of a 10 M⊙ model during the advanced burning phases, when the thermonuclear flame triggered by the Ne photodisintegration moves inward.

|

Fig. 9. Top to bottom: Density, temperature and chemical profiles within the core of a 10 M⊙ model during the advanced burning phase (Ne burning and beyond). In the bottom panel, lines represent the mass fractions of 16O (red), 20Ne (blue), 24Mg (cyan), 28Si (black), and 32S (magenta). No ALP production has been included in this model. The burning front is located at mr ∼ 0.44 M⊙. Above this point and up to mr ∼ 1.33 M⊙, oxygen and neon have been already fully consumed and the main constituents are now silicon and sulfur. The penetrating burning front is at mr ∼ 0.44 M⊙. More outside, oxygen and neon are already fully consumed and the main constituents are silicon and sulfur. |

Next, we computed a few additional models, incorporating ALP energy loss. We found that for g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5,  increases to 10.4 M⊙. In this model, Ne first ignites at a mass coordinate of 0.858 M⊙, within an ONe core of 1.381 M⊙ and a CO core of 1.408 M⊙. Results for different choices of the coupling strengths are reported in Table 2.

increases to 10.4 M⊙. In this model, Ne first ignites at a mass coordinate of 0.858 M⊙, within an ONe core of 1.381 M⊙ and a CO core of 1.408 M⊙. Results for different choices of the coupling strengths are reported in Table 2.

Impact of ALPs on the minimum mass for CCSN progenitors.

With or without ALPs, Ne ignition always occurs when the CO core mass exceeds 1.39 M⊙ (or ONe core mass > 1.37 M⊙). Instead, the corresponding initial masses moderately depends on the axion couplings. The minimum mass for CCSNe progenitors increases by maximum 0.8 M⊙ (about 8%) when ALP coupling strengths within current bounds are assumed.

3.4. Age, luminosity, and mass of the lightest CCSN progenitor

Numerous approaches have been developed to estimate the mass of CCSN progenitors. A division into two classes can be made: one comprising methods based on explosive outcomes (light curves and spectra) and the other including ones that rely on observed progenitor properties (pre-explosive luminosities or the ages of the parent stellar population). In both cases, theoretical models – explosive in the first case and hydrostatic in the latter – must be used to relate the observed properties to the progenitor initial mass (or ZAMS mass). This makes the result highly dependent on the model used. Keeping this caveat in mind, we go on to compare the results of these studies to our theoretical prediction.

As shown by Barker et al. (2023), the progenitor mass of a SNII-P can be estimated from the observed bolometric light curves. In particular, they found a relationship between the plateau luminosity and the progenitor iron-core mass. Hence, using a theoretical initial mass-final core mass relation, Barker et al. (2023) derived a minimum ZAMS mass of  M⊙ for SNII-P progenitors. This is in excellent agreement with the value we derived for the reference model and does not exclude a thermal production of ALPs with electron and photon coupling within the current bounds (see Table 2).

M⊙ for SNII-P progenitors. This is in excellent agreement with the value we derived for the reference model and does not exclude a thermal production of ALPs with electron and photon coupling within the current bounds (see Table 2).

A method based on the luminosity of red-super-giant (RSG) progenitors has been developed by Smartt (2009, 2015). Based on 20 archival pre-explosive images, they found a minimum mass for CCSN progenitors of  M⊙, also in agreement with the prediction of our reference model. However, this result seems to exclude a sizable additional cooling due to a possible thermal production of A In this case, the observed parameter is the RSG luminosity, while the progenitor mass is obtained from a specific set of stellar evolutionary tracks. If the ALP production is effective in stellar interiors, the progenitor mass would need to be derived using a set of models that incorporates the associated energy drain. This inconsistency can be resolved by directly comparing observed RSG luminosities with the corresponding predicted values. The dimmer RSG progenitors in the CCSN sample, SN 2003gd, 2005cs, 2008bk, 2009md, and 2012A (see Smartt (2015)), have luminosities (log L/L⊙) ranging from 4.4 to 4.6. These observed minimum luminosities are aptly reproduced by our models, with or without ALPs. We note that while the minimum progenitor mass increases when ALPs are produced in stellar interior, the corresponding final luminosity is marginally affected. Indeed, as explained in Straniero et al. (2019a), models with ALPs show a fainter progenitor. For this reason, the larger minimum mass obtained when ALP energy loss is switched on is compensated by a reduction of the final luminosity.

M⊙, also in agreement with the prediction of our reference model. However, this result seems to exclude a sizable additional cooling due to a possible thermal production of A In this case, the observed parameter is the RSG luminosity, while the progenitor mass is obtained from a specific set of stellar evolutionary tracks. If the ALP production is effective in stellar interiors, the progenitor mass would need to be derived using a set of models that incorporates the associated energy drain. This inconsistency can be resolved by directly comparing observed RSG luminosities with the corresponding predicted values. The dimmer RSG progenitors in the CCSN sample, SN 2003gd, 2005cs, 2008bk, 2009md, and 2012A (see Smartt (2015)), have luminosities (log L/L⊙) ranging from 4.4 to 4.6. These observed minimum luminosities are aptly reproduced by our models, with or without ALPs. We note that while the minimum progenitor mass increases when ALPs are produced in stellar interior, the corresponding final luminosity is marginally affected. Indeed, as explained in Straniero et al. (2019a), models with ALPs show a fainter progenitor. For this reason, the larger minimum mass obtained when ALP energy loss is switched on is compensated by a reduction of the final luminosity.

One last method employed to estimate the minimum mass of SN progenitor is based on the age of the parent stellar population. Recently, Díaz-Rodríguez et al. (2021) investigated the local star formation histories to estimate the ages of a sample of 22 historic CCSNe. In this way, they inferred the slope of the age distribution and the maximum age of CCSNe. Hence, by using single-star evolutionary tracks, they transformed the progenitor age distribution into a progenitor mass distribution. The resulting minimum mass for CCSNe is  . This value is lower than the limits established by other methods, as well as our theoretical predictions. We note that the adopted stellar models (Marigo et al. 2017) were computed assuming a large convective-core overshoot for H-burning stars that implies a lower ZAMS mass for a fixed stellar lifetime. To avoid the dependence on the adopted stellar models, we can directly compare the age inferred from the star formation history with the one we predict for the minimum CCSN progenitor. In particular Díaz-Rodríguez et al. (2021) obtained a maximum age of

. This value is lower than the limits established by other methods, as well as our theoretical predictions. We note that the adopted stellar models (Marigo et al. 2017) were computed assuming a large convective-core overshoot for H-burning stars that implies a lower ZAMS mass for a fixed stellar lifetime. To avoid the dependence on the adopted stellar models, we can directly compare the age inferred from the star formation history with the one we predict for the minimum CCSN progenitor. In particular Díaz-Rodríguez et al. (2021) obtained a maximum age of  Myr, to be compared with the 25.85 Myr of our 9.7 M⊙ reference models (see Table 2). The discrepancy is even worse when a thermal production of ALPs is considered. Indeed, AlP energy loss accelerates fuel consumption during the main nuclear burning phases.

Myr, to be compared with the 25.85 Myr of our 9.7 M⊙ reference models (see Table 2). The discrepancy is even worse when a thermal production of ALPs is considered. Indeed, AlP energy loss accelerates fuel consumption during the main nuclear burning phases.

4. Summary and conclusions

In the present study, we have investigated the impact of ALPs on the final destiny of stars with masses ranging between 3 and 11 M⊙. In particular, we derived the minimum stellar mass for the occurrence of the second dredge-up and the critical masses for off-center carbon and neon ignitions in degenerate cores, under various assumptions about the strengths of the ALP-photon and ALP-electron couplings. The final destiny of stars in this mass range is of pivotal importance in astrophysics. Below the mass threshold for Ne ignition, these stars lead to massive WDs that (in binary systems) might be accreted via mass transfer from the companion star, giving rise to classical or recurrent novae, prompt SNIa, and AIC events. Above this threshold, they are progenitors of CCSN SNe.

Our main findings are summarized below, highlighting the differences between reference models (without ALP production) and models calculated with ALP production rates at the current upper coupling strength limits, namely, g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5. In all cases, the initial chemical composition is Y = 0.27 and Z = 0.014, while both convective overshoot and rotation are neglected.

-

the minimum initial stellar mass that experiences C-ignition is 7.5 M⊙ and 8.5 M⊙, for the reference and the ALP models, respectively. The increase in

the minimum initial stellar mass that experiences C-ignition is 7.5 M⊙ and 8.5 M⊙, for the reference and the ALP models, respectively. The increase in  is due to the earlier occurrence of the second dredge-up in ALP models, which is a consequence of extra energy loss within the He-shell. The maximum mass of the corresponding CO WDs increases by 0.04 M⊙, from 1.06 to 1.10 M⊙, while the lifetime of the corresponding WD stellar progenitors is reduced from above 43.5 to 33.1 Myr.

is due to the earlier occurrence of the second dredge-up in ALP models, which is a consequence of extra energy loss within the He-shell. The maximum mass of the corresponding CO WDs increases by 0.04 M⊙, from 1.06 to 1.10 M⊙, while the lifetime of the corresponding WD stellar progenitors is reduced from above 43.5 to 33.1 Myr. -

The lifetime of the more massive CO WD (0.8 < MWD/M⊙ < 1.1) is shorter when ALPs are included in the calculation of stellar models. The lifetime reduction is more pronounced at lower masses. For instance, for a 0.88 M⊙ CO WD progenitor, it is reduced from 113 to 50 Myr. This occurrence might have an impact on the time elapsed between the progenitor formation and the explosion of the first SNe Ia, which is expected to be ≥40 Myr (Rodney et al. 2014).

-

Models whose masses are slightly above

undergo an incomplete C burning. After the off-center ignition, the burning flame moves inward, but never reaches the center. These models leave an hybrid core, whose innermost portion is made of C and O, while the outermost is a mixture of O and Ne. The minimum mass in which the C burning is completed (up to the center) is 8 and 8.9 M⊙, for models without and with ALPs, respectively. In both cases, the corresponding core mass is ∼1.15 M⊙. If the core mass of these stars approaches the Chandrasekhar limit (due to shell burning in the super-AGB phase) or the mass of the resulting WD increases (due to accretion in binary systems), the presence of carbon near the center would likely trigger a thermonuclear explosion, rather than a corecollapse.

undergo an incomplete C burning. After the off-center ignition, the burning flame moves inward, but never reaches the center. These models leave an hybrid core, whose innermost portion is made of C and O, while the outermost is a mixture of O and Ne. The minimum mass in which the C burning is completed (up to the center) is 8 and 8.9 M⊙, for models without and with ALPs, respectively. In both cases, the corresponding core mass is ∼1.15 M⊙. If the core mass of these stars approaches the Chandrasekhar limit (due to shell burning in the super-AGB phase) or the mass of the resulting WD increases (due to accretion in binary systems), the presence of carbon near the center would likely trigger a thermonuclear explosion, rather than a corecollapse. -

More massive models form an O-Ne core surrounded by an active C burning shell. Later on, those with mass above

ignite Ne. This further threshold is 9.7 M⊙, for no-ALP models, and up to 10.4 M⊙ when ALP energy loss is included. Stars forming an ONe core whose mass is lower than

ignite Ne. This further threshold is 9.7 M⊙, for no-ALP models, and up to 10.4 M⊙ when ALP energy loss is included. Stars forming an ONe core whose mass is lower than  will form ONe WDs; alternatively, in cases where the core mass grows up to the Chandrasekhar limit during the super AGB, their outcome will be an electron-capture SNe. Then, accretion in binary may trigger an AIC. In any case, the mass range of these stars is shifted upward when ALPs are considered. Therefore, if a Salpeter-like mass distribution is assumed (i.e., a power law with exponent α = −2.35), the number of these stars is reduced by ∼30% when ALPs are included in stellar modelcalculations.

will form ONe WDs; alternatively, in cases where the core mass grows up to the Chandrasekhar limit during the super AGB, their outcome will be an electron-capture SNe. Then, accretion in binary may trigger an AIC. In any case, the mass range of these stars is shifted upward when ALPs are considered. Therefore, if a Salpeter-like mass distribution is assumed (i.e., a power law with exponent α = −2.35), the number of these stars is reduced by ∼30% when ALPs are included in stellar modelcalculations. -

is also the minimum mass for progenitors of CCSNe. Both the observed minimum luminosity of CCSN progenitors (Smartt 2015) and the mass estimated from the plateau luminosity of SNII-P (Barker et al. 2023) are compatible with the predictions of our models, either with or without ALPs. On the contrary, the maximum age of the parent stellar population (Díaz-Rodríguez et al. 2021) appears definitively higher than that required by our models. This occurrence might imply the need of a convective core overshoot or rotational induced mixing during the main sequence phase. It is noteworthy that the lifetime of the

is also the minimum mass for progenitors of CCSNe. Both the observed minimum luminosity of CCSN progenitors (Smartt 2015) and the mass estimated from the plateau luminosity of SNII-P (Barker et al. 2023) are compatible with the predictions of our models, either with or without ALPs. On the contrary, the maximum age of the parent stellar population (Díaz-Rodríguez et al. 2021) appears definitively higher than that required by our models. This occurrence might imply the need of a convective core overshoot or rotational induced mixing during the main sequence phase. It is noteworthy that the lifetime of the  model is substantially shorter in case of ALPs (see Table 2).

model is substantially shorter in case of ALPs (see Table 2).

Finally, we note that our ALP stellar models do not include any suppression of the blue loop during the core-He burning phase, which was previously reported by Friedland et al. (2013). Overall, if asteroseismological methods are able to independently determine the extent of mixing in massive main sequence stars, then the measured ages of lighter CCSN progenitors could be used to constrain the coupling of ALPs with standard particles.

Acknowledgments

This article is based upon work from COST Action COSMIC WISPers CA21106, supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology); I.D acknowledges founding from the project PID2021-123110NB-I00 financed by the Spanish MCIN/AEI /10.13039/501100011033/ & FEDER A way to make Europe, UE. MG acknowledges support from the Spanish Agencia Estatal de Investigación under grant PID2019-108122GB-C31, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and from the “European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR” (Planes complementarios, Programa de Astrofísica y Física de Altas Energías). He also acknowledges support from grant PGC2022-126078NB-C21, “Aún más allá de los modelos estándar,” funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF A way of making Europe.” Additionally, MG acknowledges funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the European Research Council (ERC) grant agreement ERC-2017-AdG788781 (IAXO+). The work of A.M. was partially supported by the research grant number 2022E2J4RK “PANTHEON: Perspectives in Astroparticle and Neutrino THEory with Old and New messengers” under the program PRIN 2022 funded by the Italian Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca (MUR) and by the European Union – Next Generation EU. This work is (partially) supported by ICSC – Centro Nazionale di Ricerca in High Performance Computing, Big Data and Quantum Computing, funded by European Union–NextGenerationEU. O.S. and L.P. acknowledge partial financial support from the INAF Minigrant 2023 Self-consistent Modeling of Interacting Binary Systems and O.S. acknowledges funding from the INAF large program BRAVOSUN.

References

- Abbott, L. F., & Sikivie, P. 1983, Phys. Lett. B, 120, 133 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Abeln, A., Altenmüller, K., Arguedas Cuendis, S., et al. 2021, JHEP, 05, 137 [Google Scholar]

- Adams, C. B., Aggarwal, N., Agrawal, A., et al. 2022, in Snowmass 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, P., Bauer, M., Beacham, J., et al. 2021, Eur. Phys. J. C, 81, 1015 [Google Scholar]

- Ahyoune, S., Altenmüller, K., Antolín, I., et al. 2025, JHEP, 02, 159 [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, K., Anastassopoulos, V., Arguedas-Cuendis, S., et al. 2024, Phys. Rev. Lett., 133, 221005 [Google Scholar]

- Antel, C., Battaglieri, M., Beacham, J., et al. 2023, Eur. Phys. J. C, 83, 1122 [Google Scholar]

- Arias, P., Cadamuro, D., Goodsell, M., et al. 2012, JCAP, 1206, 013 [Google Scholar]

- Armengaud, E., Avignone, F. T., Betz, M., et al. 2014, JINST, 9, T05002 [Google Scholar]

- Armengaud, E., Attié, D., Basso, S., et al. 2019, JCAP, 2019, 047 [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitaki, A., Dimopoulos, S., Dubovsky, S., Kaloper, N., & March-Russell, J. 2010, Phys. Rev. D, 81, 123530 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ayala, A., Domínguez, I., Giannotti, M., Mirizzi, A., & Straniero, O. 2014, Phys. Rev. Lett., 113, 191302 [Google Scholar]

- Barker, B. L., O’Connor, E. P., & Couch, S. M. 2023, ApJ, 944, L2 [Google Scholar]

- Baumgardt, H., & Vasiliev, E. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 5957 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S. A., & Iben, I., Jr 1979, ApJ, 232, 831 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Capozzi, F., & Raffelt, G. 2020, Phys. Rev. D, 102, 083007 [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, A., & Raffelt, G. 2024, in 1st General Meeting and 1st Training School of the COST Action COSMIC WISPers, 1, 41 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Carenza, P., Giannotti, M., Isern, J., Mirizzi, A., & Straniero, O. 2025, Phys. Res., 1117, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Castellani, V., Chieffi, A., Tornambe, A., & Pulone, L. 1985, ApJ, 296, 204 [Google Scholar]

- Caughlan, G. R., & Fowler, W. A. 1988, At. Data Nucl. Data Tables, 40, 283 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cicoli, M., Goodsell, M., & Ringwald, A. 2012, JHEP, 10, 146 [Google Scholar]

- Cicoli, M., Conlon, J. P., Maharana, A., et al. 2024, Phys. Rept., 1059, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Córsico, A. H., Althaus, L. G., Miller Bertolami, M. M., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 424, 2792 [Google Scholar]

- deBoer, R. J., Görres, J., Wiescher, M., et al. 2017, Rev. Mod. Phys., 89, 035007 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Di Luzio, L., Giannotti, M., Nardi, E., & Visinelli, L. 2020, Phys. Rep., 870, 1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Rodríguez, M., Murphy, J. W., Williams, B. F., Dalcanton, J. J., & Dolphin, A. E. 2021, MNRAS, 506, 781 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dine, M., & Fischler, W. 1983, Phys. Lett. B, 120, 137 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, C. L., Gil-Pons, P., Siess, L., Lattanzio, J. C., & Lau, H. H. B. 2015, MNRAS, 446, 2599 [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, M. J., Hiskens, F. J., & Volkas, R. R. 2022, JCAP, 10, 096 [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez, I., Straniero, O., & Isern, J. 1999, MNRAS, 306, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Friedland, A., Giannotti, M., & Wise, M. 2013, Phys. Rev. Lett., 110, 061101 [Google Scholar]

- Galanti, G., Nava, L., Roncadelli, M., Tavecchio, F., & Bonnoli, G. 2023, Phys. Rev. Lett., 131, 251001 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- García-Berro, E., Ritossa, C., & Iben, I., Jr 1997, ApJ, 485, 765 [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti, M. 2023, J. Phys. Conf. Ser., 2502, 012003 [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti, M., Irastorza, I., Redondo, J., & Ringwald, A. 2016a, JCAP, 1605, 057 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti, M., Ruz, J., & Vogel, J. K. 2016b, PoS, ICHEP2016, 195 [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti, M., Irastorza, I. G., Redondo, J., Ringwald, A., & Saikawa, K. 2017, JCAP, 10, 010 [Google Scholar]

- Isern, J., Hernanz, M., & Garcia-Berro, E. 1992, ApJ, 392, L23 [Google Scholar]

- Isern, J., García-Berro, E., Torres, S., Cojocaru, R., & Catalán, S. 2018, MNRAS, 478, 2569 [Google Scholar]

- Jaeckel, J., & Ringwald, A. 2010, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci., 60, 405 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kepler, S. O., Winget, D. E., Vanderbosch, Z. P., et al. 2021, ApJ, 906, 7 [Google Scholar]

- Limongi, M., Roberti, L., Chieffi, A., & Nomoto, K. 2024, ApJS, 270, 29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lodders, K., Palme, H., & Gail, H. P. 2009, Landolt Börnstein, 712 [Google Scholar]

- Marigo, P., Girardi, L., Bressan, A., et al. 2017, ApJ, 835, 77 [Google Scholar]

- Miller Bertolami, M. M., Melendez, B. E., Althaus, L. G., & Isern, J. 2014, JCAP, 2014, 069 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peccei, R. D., & Quinn, H. R. 1977a, Phys. Rev. D, 16, 1791 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peccei, R. D., & Quinn, H. R. 1977b, Phys. Rev. Lett., 38, 1440 [Google Scholar]

- Preskill, J., Wise, M. B., & Wilczek, F. 1983, Phys. Lett. B, 120, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Raffelt, G. G. 1996, Stars as laboratories for fundamental physics: The astrophysics of neutrinos, axions, and other weakly interacting particles (University of Chicago Press) [Google Scholar]

- Raffelt, G. G. 1999, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci., 49, 163 [Google Scholar]

- Ringwald, A. 2014, in 49th Rencontres de Moriond on Electroweak Interactions and Unified Theories, 223 [Google Scholar]

- Ritossa, C., García-Berro, E., & Iben, I., Jr 1999, ApJ, 515, 381 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rodney, S. A., Riess, A. G., Strolger, L.-G., et al. 2014, AJ, 148, 13 [Google Scholar]

- Sallaska, A. L., Iliadis, C., Champange, A. E., et al. 2013, ApJS, 207, 18 [Google Scholar]

- Smartt, S. J. 2009, ARA&A, 47, 63 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Smartt, S. J. 2015, PASA, 32 [Google Scholar]

- Straniero, O., Domínguez, I., Imbriani, G., & Piersanti, L. 2003, ApJ, 583, 878 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Straniero, O., Ayala, A., Giannotti, M., Mirizzi, A., & Dominguez, I. 2015, Axion-Photon Coupling: Astrophysical Constraints (Hamburg: Verlag Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron), 77 [Google Scholar]

- Straniero, O., Dominguez, I., Piersanti, L., Giannotti, M., & Mirizzi, A. 2019a, ApJ, 881, 158 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Straniero, O., Piersanti, L., Dominguez, I., & Tumino, A. 2019b, in Nuclei in the Cosmos XV, Springer Proceedings in Physics, 219, 7 [Google Scholar]

- Straniero, O., Pallanca, C., Dalessandro, E., et al. 2020, A&A, 644, A166 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Troitsky, S. V. 2025, Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett., 121, 159 [Google Scholar]

- Viaux, N., Catelan, M., Stetson, P. B., et al. 2013, Phys. Rev. Lett., 111, 231301 [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. 1978, Phys. Rev. Lett., 40, 223 [Google Scholar]

- Wilczek, F. 1978, Phys. Rev. Lett., 40, 279 [Google Scholar]

- Woosley, S. E., & Heger, A. 2015, ApJ, 810, 34 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Left panel: Evolution of the ALP and neutrino luminosities through the late portion of the He-burning phase and the subsequent early-AGB. Right panel: Evolution of the contributions to the ALP luminosity of the different production processes. The plots refers to the 7 M⊙ model with g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Energy-loss rates due to ALPs production within the core of a 7 M⊙ with g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5. The left and the right panels refer to the two blue points in Fig. 3, as taken before and after the SDU, respectively. The solid-black line is the total ALP energy-loss rate, while the blue, the red, and the magenta lines represent the contributions of the Primakoff, Compton, and Bremsstrahlung processes, respectively. For comparison, the neutrino energy-loss rate is also reported (black-dashed line). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. ALP impact on the SDU. Black lines (top to botton): Inner border of the convective envelope, location of the H-burning shell and location of the He-burning shell, for a 7 M⊙ (no ALPs), during the early-AGB phase; red lines (top to bottom): same as the black lines, but with g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5. The filled circles represent the He-shell locations for the two models in Fig. 2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Top to bottom: Density, temperature, and chemical profiles within the core of a 7.7 M⊙ model at the onset of the super-AGB phase. In the bottom panel, lines represent the mass fractions of 4He (green), 12C (black), 16O (red), 20Ne (blue), and 24Mg (magenta). No ALP production has been included in this model. We note that it is only above 0.85 M⊙ that C burning has been active. This model represents an example of hybrid WD progenitors. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Kippenhahn diagram of the degenerate C burning in the 9 M⊙ stellar model. The red region represents the convective envelope, while the violet regions are convective C-burning episodes. The t = 0 point is arbitrary. Note: the SDU occurs after the first C flash. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. As in Fig. 4, but for a 9 M⊙ model (no ALPs). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. As in Fig. 4, but for a 8.6 M⊙ model (g10 = 0.6 and g13 = 1.5). Only above 0.4 M⊙ the C burning has been completed. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Contours of Δ |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9. Top to bottom: Density, temperature and chemical profiles within the core of a 10 M⊙ model during the advanced burning phase (Ne burning and beyond). In the bottom panel, lines represent the mass fractions of 16O (red), 20Ne (blue), 24Mg (cyan), 28Si (black), and 32S (magenta). No ALP production has been included in this model. The burning front is located at mr ∼ 0.44 M⊙. Above this point and up to mr ∼ 1.33 M⊙, oxygen and neon have been already fully consumed and the main constituents are now silicon and sulfur. The penetrating burning front is at mr ∼ 0.44 M⊙. More outside, oxygen and neon are already fully consumed and the main constituents are silicon and sulfur. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.