| Issue |

A&A

Volume 703, November 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A220 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Atomic, molecular, and nuclear data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556510 | |

| Published online | 20 November 2025 | |

Electron impact ro-vibrational transitions and dissociative recombination of H2+ and HD+

Rate coefficients and astrophysical implications

1

Laboratoire Ondes et Milieux Complexes, UMR 6294 CNRS and Université Le Havre Normandie,

25 rue Philippe Lebon, BP 540,

76058

Le Havre,

France

2

Department of Physical Foundation of Engineering, Politehnica University of Timişoara,

Blvd. Vasile Pârvan 2,

300223

Timişoara,

Romania

3

Department of Physics, West University of Timişoara,

Blvd. Vasile Pârvan 4,

300223

Timişoara,

Romania

4

LPF, UFD Mathématiques, Informatique Appliquée et Physique Fondamentale, University of Douala,

PO Box,

24157

Douala,

Cameroon

5

Istituto per la Scienza e Tecnologia dei Plasmi,

CNR, Bari,

Italy

6

Department of Comput. Informat. Technol. Engineering, Politehnica University of Timişoara,

Bv. Vasile Pârvan 2,

300223

Timişoara,

Romania

7

Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, CentraleSupélec, Structures Propriétés et Modélisation des solides,

Gif-sur-Yvette,

France

8

Université Paris-Saclay, CentraleSupélec, Laboratoire de Génie des Procédés et Matériaux,

Gif-sur-Yvette,

France

9

LSAMA, Department of Physics, Faculty of Science of Tunis,

University of Tunis El Manar,

2092

Tunis,

Tunisia

10

Department of Chemistry,

Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro,

70125

Bari,

Italy

11

INAF Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri,

50125

Firenze,

Italy

12

HUN-REN Institute for Nuclear Research (ATOMKI),

Bem Sqr. 18/c,

4026

Debrecen,

Hungary

13

LAC CNRS-UMR 9025, Université Paris-Saclay, ENS Cachan, Campus d’Orsay,

Bât. 505,

91405

Orsay,

France

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

19

July

2025

Accepted:

6

October

2025

Context. Molecular hydrogen and its cation H2+ are among the first species formed in the early Universe, and play a key role in the thermal and chemical evolution of the primordial gas. In molecular clouds, H2+ ions formed through ionization of H2 by particles react rapidly with H2 to form H3+, triggering the formation of almost all detected interstellar molecules.

Aims. We present a new set of cross sections and rate coefficients for state-to-state ro-vibrational transitions (RVT) of the H2+ and HD+ ions, induced by low-energy electron collisions. The study includes the major electron-impact processes relevant for low-metallicity astrochemistry: inelastic and superelastic scattering, and dissociative recombination (DR).

Methods. The electron-induced processes involving H2+ and HD+ were treated using the multichannel quantum defect theory (MQDT). Results. The newly calculated thermal rate coefficients show significant differences compared to those used in previous studies. When introduced into astrochemical models, particularly for shock-induced chemistry in metal-free gas, the updated DR rates produce substantial changes in the predicted molecular abundances.

Conclusions. These data provide updated and improved input for the modeling of hydrogen-rich plasmas in environments where a high abundance of free electrons is expected, such as planetary nebulae, HII regions, and the ionospheres of giant planets.

Key words: molecular data / scattering / ISM: abundances / HII regions / planetary nebulae: general / early Universe

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Molecular hydrogen and its cation are among the first species formed in the early Universe (for a review, see, e.g., Galli & Palla 2013). Due to the lack of a dipole moment, in the absence of catalyzing dust grains, the homonuclear molecule H2 cannot be formed by radiative association of two hydrogen atoms, and its production in a gas of primordial composition proceeds via the intermediary species H−and  (see, e.g., Lepp et al. 2002; Coppola et al. 2011; Gay et al. 2012). The latter channel is the dominant one at high temperature, and is limited by the destruction of

(see, e.g., Lepp et al. 2002; Coppola et al. 2011; Gay et al. 2012). The latter channel is the dominant one at high temperature, and is limited by the destruction of  by photodissociation, charge exchange with H atoms, and dissociative recombination (DR) with electrons. In dense molecular clouds where ultraviolet radiation is efficiently absorbed by dust grains,

by photodissociation, charge exchange with H atoms, and dissociative recombination (DR) with electrons. In dense molecular clouds where ultraviolet radiation is efficiently absorbed by dust grains,  is formed in excited vibrational states by cosmic-ray ionization of H2 (Glassgold & Langer 1973) and rapidly transformed into

is formed in excited vibrational states by cosmic-ray ionization of H2 (Glassgold & Langer 1973) and rapidly transformed into  , which is the starting point of gas phase ion-molecule reaction chemistry (see, e.g., Tielens 2013). In addition, due to the high electron densities, DR of

, which is the starting point of gas phase ion-molecule reaction chemistry (see, e.g., Tielens 2013). In addition, due to the high electron densities, DR of  plays an important role also in brown dwarfs atmospheres (Gibbs & Fitzgerald 2022; Pineda et al. 2024), planetary nebulae (Black 1978), and HII regions (Aleman & Gruenwald 2004).

plays an important role also in brown dwarfs atmospheres (Gibbs & Fitzgerald 2022; Pineda et al. 2024), planetary nebulae (Black 1978), and HII regions (Aleman & Gruenwald 2004).

The molecular hydrogen cation is also the primary molecular ion formed by photoionization of H2 in the upper atmospheres and ionospheres of outer gaseous planets in the Solar System and extrasolar giant planets (see, e.g., Chadney et al. 2016). In this context, the recombination of  with electrons has also been studied as a source of excited states of atomic hydrogen, in particular H(2p), in models of the ultraviolet emission of Jupiter’s upper atmosphere, where it competes with the energy transfer between free protons and H(2s) (Shemansky 1985).

with electrons has also been studied as a source of excited states of atomic hydrogen, in particular H(2p), in models of the ultraviolet emission of Jupiter’s upper atmosphere, where it competes with the energy transfer between free protons and H(2s) (Shemansky 1985).

Dissociative recombination is also an important reaction in laboratory astrophysics (Parigger et al. 2018) because it affects the diagnostics of electric discharges in hydrogen and deuterium mixtures based on the line profile of the hydrogen Balmer series, where this recombination process becomes dominant. The effect has been studied in particular in recombining plasmas where the electron temperature is below 1 eV (Wünderlich et al. 2009; Friedl et al. 2020) and therefore relevant for the interstellar medium. The effect of DR on diagnostics was also studied using the Monte Carlo DEGAS2 model (Stotler & Karney 1994), applied to the simulation of MAP-II (materials and plasma) columnar plasma sources (Tanaka et al. 2000), used to study edge recombination. In this type of source, the plasma has two mixed but not balanced components: one has a temperature of the order of 1 eV, and a second has a higher temperature. Krasheninnikov et al. (1997) used a collisional-radiative model to show that, due to this reaction too, the formation of molecular ions has a significant effect on the recombination rate of a hydrogen plasma.

In all these environments, in which the ionization fraction is significant, the electron-impact induced ro-vibrational transitions (RVT), strong competitors of the DR, provide the dominant path to excitation and de-excitation process of  (Black & Van Dishoeck 1987; Le Petit et al. 2002; Agundez et al. 2010). The aim of the present paper is to provide accurate cross sections and rate coefficients for electron-impact induced RVT,

(Black & Van Dishoeck 1987; Le Petit et al. 2002; Agundez et al. 2010). The aim of the present paper is to provide accurate cross sections and rate coefficients for electron-impact induced RVT,

(1)

and DR reactions,

(1)

and DR reactions,

(2)

of

(2)

of  and its isotopolog HD+, including all relevant ro-vibrational levels. In reactions (1) and (2),

and its isotopolog HD+, including all relevant ro-vibrational levels. In reactions (1) and (2),  and

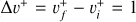

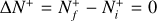

and  are the initial and final rotational and vibrational quantum numbers of the target ion, respectively, ɛ/ɛ′ is the energy of the incident and scattered electron, and n the principal quantum number of the excited atom resulting from dissociation. RVT can be further characterized as resonant elastic collisions, inelastic collisions and super-elastic collisions when the energy ɛ′ of the scattered electron is equal to, smaller, or larger than the energy ɛ of the incident electron. The spectroscopic information, given by the output of reactions (1)-(2), is sensitive to the initial (

are the initial and final rotational and vibrational quantum numbers of the target ion, respectively, ɛ/ɛ′ is the energy of the incident and scattered electron, and n the principal quantum number of the excited atom resulting from dissociation. RVT can be further characterized as resonant elastic collisions, inelastic collisions and super-elastic collisions when the energy ɛ′ of the scattered electron is equal to, smaller, or larger than the energy ɛ of the incident electron. The spectroscopic information, given by the output of reactions (1)-(2), is sensitive to the initial ( ) and final (

) and final ( ) quantum numbers of the target ions and consequently provides the structure of the ionized media.

) quantum numbers of the target ions and consequently provides the structure of the ionized media.

This study was initiated in previous publications by our group (Motapon et al. 2014; Epée Epée et al. 2016; Djuissi et al. 2020; Epée Epée et al. 2022). We notice that, whereas for  the rotational transitions involve rotational quantum numbers of strictly the same parity (“gerade” or “ungerade”), this rule is not valid for the deuterated variant. However, we assumed it for HD+ too, since no data are currently available for the gerade/ungerade mixing, and since the transitions between rotational quantum numbers of different parity are much less intense than the others (Shafir et al. 2009).

the rotational transitions involve rotational quantum numbers of strictly the same parity (“gerade” or “ungerade”), this rule is not valid for the deuterated variant. However, we assumed it for HD+ too, since no data are currently available for the gerade/ungerade mixing, and since the transitions between rotational quantum numbers of different parity are much less intense than the others (Shafir et al. 2009).

This paper is organized as follows: in Sect. 2 we describe our theoretical method. In Sect. 3, we present our results in terms of cross sections and rate coefficients. In Sect. 4, we discuss the applications in the media of astro-chemical interest. And, finally, in Sect. 5 we summarize our conclusions.

2 Theoretical method

The electron-induced reactions (1) and (2) for  and HD+ are studied by a step-wise version of the multichannel quantum defect theory (MQDT), which we successfully applied to calculate DR, ro-vibrational and dissociative excitation cross sections for molecular cations such as

and HD+ are studied by a step-wise version of the multichannel quantum defect theory (MQDT), which we successfully applied to calculate DR, ro-vibrational and dissociative excitation cross sections for molecular cations such as  and its isotopolog (Waffeu Tamo et al. 2011; Chakrabarti et al. 2013; Motapon et al. 2014; Epée Epée et al. 2016, 2022), CH+(Mezei et al. 2019), SH+(Kashinski et al. 2017), BeH+and its isotopologs (Niyonzima et al. 2017, 2018; Pop et al. 2021).

and its isotopolog (Waffeu Tamo et al. 2011; Chakrabarti et al. 2013; Motapon et al. 2014; Epée Epée et al. 2016, 2022), CH+(Mezei et al. 2019), SH+(Kashinski et al. 2017), BeH+and its isotopologs (Niyonzima et al. 2017, 2018; Pop et al. 2021).

A detailed description of the method has been given in previous articles (Motapon et al. 2014; Mezei et al. 2019), and we list below only the main steps of our current MQDT treatment:

Building the interaction matrix based on the couplings between ionization channels – associated with the ro-vibrational levels N+, v+of the cation and with the orbital quantum number l of the incident (Rydberg) electron – and the dissociation channels.

Computation of the reaction matrix K as a second-order perturbative solution of the Lippmann-Schwinger integral equation (Ngassam et al. 2003).

Diagonalization of the reaction matrix by building the short-range representation of the eigenchannel.

Frame transformation from the Born-Oppenheimer (shortrange) representation—characterized by quantum numbers N, v, Λ, and l—to the close-coupling (long-range) representation, defined by N+, v+, and l. Here, N and N+denote the total rotational quantum numbers of the neutral system and the ion, respectively, v and v+are the corresponding vibrational quantum numbers, and l is the orbital angular momentum of the incoming, outgoing, or scattered electron.

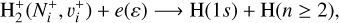

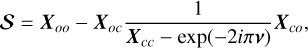

Building of the generalized scattering matrix based on the frame-transformation coefficients organized in blocks associated with energetically open (o) and/or closed (c) channels:

(3)

(3)Building of the physical scattering matrix:

(4)

obtained by the so-called “elimination of closed channel” (Seaton 1983). The diagonal matrix v in the denominator contains the effective quantum numbers corresponding to the vibrational thresholds of the closed ionization channels at the current total energy of the system.

(4)

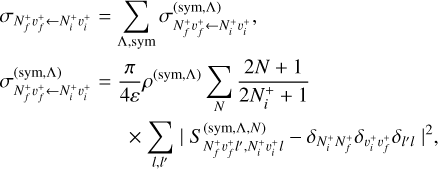

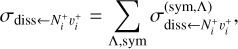

obtained by the so-called “elimination of closed channel” (Seaton 1983). The diagonal matrix v in the denominator contains the effective quantum numbers corresponding to the vibrational thresholds of the closed ionization channels at the current total energy of the system.Computation of the cross sections for the target initially in a state characterized by the quantum numbers

, and for the energy of the incident electron ɛ, the RVT and the DR global cross sections read, respectively,

, and for the energy of the incident electron ɛ, the RVT and the DR global cross sections read, respectively,

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

(7)

where sym refers to the inversion symmetry – gerade/ungerade – and to the spin quantum number of the neutral system, Λ is the projection of the electronic orbital angular momentum on the molecular axis, and ρ(sym, Λ) is the ratio between the spin multiplicities of the neutral system and that of the ion.

(7)

where sym refers to the inversion symmetry – gerade/ungerade – and to the spin quantum number of the neutral system, Λ is the projection of the electronic orbital angular momentum on the molecular axis, and ρ(sym, Λ) is the ratio between the spin multiplicities of the neutral system and that of the ion.

This work extends our previous studies performed on HD+ (Waffeu Tamo et al. 2011; Motapon et al. 2014) and  (Epée Epée et al. 2016) for low collision energies relevant for kinetics modeling in astrochemistry, by considering simultaneous rotational and vibrational transitions (excitations and/or deexcitations) and by increasing the range of the incident energy of the electron. We used the same molecular structure data sets as those from our previous studies (Waffeu Tamo et al. 2011; Motapon et al. 2014; Epée Epée et al. 2016; Djuissi et al. 2020; Epée Epée et al. 2022). The energies of the first 30 ro-vibrational levels of the

(Epée Epée et al. 2016) for low collision energies relevant for kinetics modeling in astrochemistry, by considering simultaneous rotational and vibrational transitions (excitations and/or deexcitations) and by increasing the range of the incident energy of the electron. We used the same molecular structure data sets as those from our previous studies (Waffeu Tamo et al. 2011; Motapon et al. 2014; Epée Epée et al. 2016; Djuissi et al. 2020; Epée Epée et al. 2022). The energies of the first 30 ro-vibrational levels of the  electronic state of

electronic state of  and HD+relative to the ground level

and HD+relative to the ground level  are listed in Table 1. The molecular states of the neutral (H2, HD) systems taken into account were of

are listed in Table 1. The molecular states of the neutral (H2, HD) systems taken into account were of  , and 3Πu symmetries. Consequently, the partial waves considered for the incident electron were s and d for the

, and 3Πu symmetries. Consequently, the partial waves considered for the incident electron were s and d for the  states, d for

states, d for  and 3Δg, and

and 3Δg, and  , and 3Πu.

, and 3Πu.

First 30 ro-vibrational levels of  and HD+.

and HD+.

3 Results and discussions

We computed the RVT cross sections for the lowest 30 rovibrational levels of  and HD+in their ground

and HD+in their ground  electronic state, and for collision energies ranging between 10−5−1.09 eV–this latter value corresponding to the opening of the following dissociation channel – with an energy step of 0.01 meV. We considered both “direct” and “indirect” mechanisms – i.e., including “open” and “closed” channels, respectively. The reaction matrix was evaluated to second order in perturbation theory.

electronic state, and for collision energies ranging between 10−5−1.09 eV–this latter value corresponding to the opening of the following dissociation channel – with an energy step of 0.01 meV. We considered both “direct” and “indirect” mechanisms – i.e., including “open” and “closed” channels, respectively. The reaction matrix was evaluated to second order in perturbation theory.

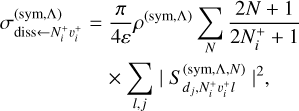

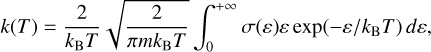

Thermally averaged rate coefficients were obtained by convolution of the cross sections with the isotropic Maxwell distribution function of the kinetic energy of the incident electrons:

(8)

where σ(ɛ) are the cross sections calculated according to Eqs. (5)–(8) and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

(8)

where σ(ɛ) are the cross sections calculated according to Eqs. (5)–(8) and kB is the Boltzmann constant.

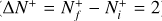

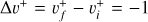

Figures 1 4 display representative samples of RVT cross sections and thermal rate coefficients. More specifically, Figure 1 displays the cross sections of simultaneous electron-impact rotational excitation ( ) and vibrational de-excitation (

) and vibrational de-excitation ( ) from the ground

) from the ground  electronic state and initial ro-vibrational levels

electronic state and initial ro-vibrational levels  and

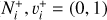

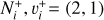

and  . Figure 2 displays the corresponding rate coefficients for ten ro-vibrational levels of the target, ranging from (0, 1) to (9, 1). Figure 3 presents rate coefficients for pure rotational excitation (Δ N+=2, Δ v+=0) from levels (0, 0) to (9, 0), while Figure 4 shows rate coefficients for pure vibrational excitation (Δ N+=0, Δ v+=1) over the same set of initial levels.

. Figure 2 displays the corresponding rate coefficients for ten ro-vibrational levels of the target, ranging from (0, 1) to (9, 1). Figure 3 presents rate coefficients for pure rotational excitation (Δ N+=2, Δ v+=0) from levels (0, 0) to (9, 0), while Figure 4 shows rate coefficients for pure vibrational excitation (Δ N+=0, Δ v+=1) over the same set of initial levels.

In parallel, we computed DR cross sections under the same conditions as those used for the RVT calculations. Figure 5 presents the results for the two lowest initial levels, ( ) = (0, 0) and (1, 0). In the most recent calculations performed by Hvizdoš et al. (2025) and Hörnquist et al. (2024), only the

) = (0, 0) and (1, 0). In the most recent calculations performed by Hvizdoš et al. (2025) and Hörnquist et al. (2024), only the  symmetry of the neutral was considered, which leads to smaller cross sections than ours. Moreover, Hvizdoš et al. (2025) is using a simplified rotationless model. Our corresponding DR rate coefficients, derived from the full set of 30 levels, are shown in Figure 6 up to an electron temperature of 4000 K, along with the thermally averaged values. The latter incorporates the temperature-dependent population distributions and the ortho–para statistical weights (relevant only for

symmetry of the neutral was considered, which leads to smaller cross sections than ours. Moreover, Hvizdoš et al. (2025) is using a simplified rotationless model. Our corresponding DR rate coefficients, derived from the full set of 30 levels, are shown in Figure 6 up to an electron temperature of 4000 K, along with the thermally averaged values. The latter incorporates the temperature-dependent population distributions and the ortho–para statistical weights (relevant only for  ). The results were fit using the following expression:

). The results were fit using the following expression:

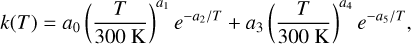

(9)

where the coefficients {a0, a5} have the values listed in Table 2. The last column lists the root-mean-square relative deviation between the calculated and fit rates, RMS

(9)

where the coefficients {a0, a5} have the values listed in Table 2. The last column lists the root-mean-square relative deviation between the calculated and fit rates, RMS ![$= \sqrt{n^{-1} \sum_{i}\left[\left(k_{i}-k^{\text {fit}}\right) / k_{i}\right]^{2}}$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa56510-25/aa56510-25-eq60.png) . The reported values (0.09-0.27) correspond to typical average deviations of about 9−27% over the full temperature range, indicating that the fits reproduce the numerical data with sufficient accuracy for astrophysical applications.

. The reported values (0.09-0.27) correspond to typical average deviations of about 9−27% over the full temperature range, indicating that the fits reproduce the numerical data with sufficient accuracy for astrophysical applications.

In the ISM, as in laboratory experiments, electron impact ionization of H2 produces vibrationally excited  ions with a non-Boltzmann distribution of energy levels that can be estimated by applying the Franck-Condon principle. In its most elementary form, this principle assumes that the transition matrix element varies slowly enough with internuclear separation that it can be factored in the calculation of the relative transition strength to various vibrational levels. In ion trap experiments, the vibrational level populations of

ions with a non-Boltzmann distribution of energy levels that can be estimated by applying the Franck-Condon principle. In its most elementary form, this principle assumes that the transition matrix element varies slowly enough with internuclear separation that it can be factored in the calculation of the relative transition strength to various vibrational levels. In ion trap experiments, the vibrational level populations of  formed by electron impact ionization of thermal H2 are in good agreement with the prediction of the Franck-Condon principle (see, e.g., Von Busch & Dunn 1972; Weijun et al. 1993; Abdellahi El Ghazaly et al. 2004). For these reasons, it is expected that

formed by electron impact ionization of thermal H2 are in good agreement with the prediction of the Franck-Condon principle (see, e.g., Von Busch & Dunn 1972; Weijun et al. 1993; Abdellahi El Ghazaly et al. 2004). For these reasons, it is expected that  ions produced in the ISM by cosmic rays (protons, nuclei and electrons) impacting ambient H2 are formed with a population of excited vibrational states close to the distribution of Franck-Condon factors (Shuter et al. 1986). These vibrationally excited levels have long lifetimes, since dipole transitions within the ground electronic state of

ions produced in the ISM by cosmic rays (protons, nuclei and electrons) impacting ambient H2 are formed with a population of excited vibrational states close to the distribution of Franck-Condon factors (Shuter et al. 1986). These vibrationally excited levels have long lifetimes, since dipole transitions within the ground electronic state of  are forbidden. Thus, even though non-reactive collisions of

are forbidden. Thus, even though non-reactive collisions of  with ambient electrons and other species will eventually establish a thermal Boltzmann distribution of level populations, averaging over a Franck-Condon distribution can be appropriate for the low density conditions of the ISM. Fitting parameters corresponding to the Franck-Condon averaged rate coefficients, for initial vibrational levels

with ambient electrons and other species will eventually establish a thermal Boltzmann distribution of level populations, averaging over a Franck-Condon distribution can be appropriate for the low density conditions of the ISM. Fitting parameters corresponding to the Franck-Condon averaged rate coefficients, for initial vibrational levels  , were obtained using the population weighting factors listed in Weijun et al. (1993).

, were obtained using the population weighting factors listed in Weijun et al. (1993).

Figure 7 presents the fit curves for the thermally averaged and Franck-Condon averaged DR rate coefficients of  (red curves), along with the fits of the thermally averaged DR rate coefficients of HD+(black curves), for initial vibrational levels

(red curves), along with the fits of the thermally averaged DR rate coefficients of HD+(black curves), for initial vibrational levels  , and 2, up to an electron temperature of 4000 K.

, and 2, up to an electron temperature of 4000 K.

|

Fig. 1 Left panel: electron-impact rotational excitation ( |

|

Fig. 2 Left panel: electron-impact rotational excitation ( |

|

Fig. 3 Left panel: electron-impact rotational excitation ( |

|

Fig. 4 Left panel: electron-impact vibrational excitation ( |

|

Fig. 5 Left panel: DR cross sections of |

|

Fig. 6 Left panel: thermal rate coefficient for the DR of |

Fitting parameters for DR rate coefficients of  and HD+.

and HD+.

|

Fig. 7 Thermally averaged and Franck-Condon averaged rate coefficients for DR of |

4 Astrophysical applications

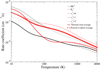

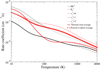

Figure 8 shows a comparison of the thermal rate coefficients of  and HD+adopted in models of the chemistry of primordial gas, compared to our results. The calculations presented in this paper (black curves) resolve considerable discrepancies in previous evaluations of the DR rate of

and HD+adopted in models of the chemistry of primordial gas, compared to our results. The calculations presented in this paper (black curves) resolve considerable discrepancies in previous evaluations of the DR rate of  and HD+, and extend the results to temperatures below ∼ 100 K, where all available estimates of the DR rate significantly underestimate its importance.

and HD+, and extend the results to temperatures below ∼ 100 K, where all available estimates of the DR rate significantly underestimate its importance.

In the early Universe, DR of  and HD+competes with photodissociation (at z ≳ 300) and charge exchange with H (at z ≲ 300) in the destruction of these species. At low redshifts (z ≲ 100) the significant increase in DR at low temperatures evidenced in the current work implies a larger effect of DR with respect to previous results obtained with the DR rate by Schneider et al. (1994): at z ≈ 10−20, the contribution of DR of

and HD+competes with photodissociation (at z ≳ 300) and charge exchange with H (at z ≲ 300) in the destruction of these species. At low redshifts (z ≲ 100) the significant increase in DR at low temperatures evidenced in the current work implies a larger effect of DR with respect to previous results obtained with the DR rate by Schneider et al. (1994): at z ≈ 10−20, the contribution of DR of  and HD+increases from ∼ 2% to ∼ 12% and from ∼ 1% to ∼ 5% of the total destruction rate, respectively. However, because of the low electron fraction, the destruction of both cations at low redshift remains dominated by charge-exchange reactions with the more abundant H atoms.

and HD+increases from ∼ 2% to ∼ 12% and from ∼ 1% to ∼ 5% of the total destruction rate, respectively. However, because of the low electron fraction, the destruction of both cations at low redshift remains dominated by charge-exchange reactions with the more abundant H atoms.

As was mentioned in the Introduction,  ions produced by cosmic-ray ionization in dense molecular clouds shielded from UV radiation are rapidly converted into

ions produced by cosmic-ray ionization in dense molecular clouds shielded from UV radiation are rapidly converted into  ions by charge transfer reactions with ambient H2. Given the importance of

ions by charge transfer reactions with ambient H2. Given the importance of  as a cornerstone of interstellar chemistry, one may wonder to what extent the DR of

as a cornerstone of interstellar chemistry, one may wonder to what extent the DR of  can affect the abundance of

can affect the abundance of  . In pre-dominantly neutral clouds, DR is generally less important than charge transfer reactions of

. In pre-dominantly neutral clouds, DR is generally less important than charge transfer reactions of  with atomic or molecular hydrogen, which are quite fast. Therefore, it is not expected that the equilibrium abundance of

with atomic or molecular hydrogen, which are quite fast. Therefore, it is not expected that the equilibrium abundance of  in molecular clouds depends on DR of

in molecular clouds depends on DR of  . However, in low-density, highly ionized nebular gas, such as planetary nebulae, planetary ionospheres, and supernova remnants, where

. However, in low-density, highly ionized nebular gas, such as planetary nebulae, planetary ionospheres, and supernova remnants, where  has been detected or predicted to be present (see, e.g., Tennyson & Miller 2019), the abundance of

has been detected or predicted to be present (see, e.g., Tennyson & Miller 2019), the abundance of  (and, as a consequence, that of

(and, as a consequence, that of  ) is entirely controlled by DR.

) is entirely controlled by DR.

Another process competing with DR in the destruction of  ions is photodissociation. In the early Universe, at high redshift, the intense cosmic radiation background is by far the dominant destruction process for all molecular ions, and DR of

ions is photodissociation. In the early Universe, at high redshift, the intense cosmic radiation background is by far the dominant destruction process for all molecular ions, and DR of  plays no role. This is not the case when the radiation field is produced by a point source, as in the case of planetary nebulae (Black 1978) and Hii regions (Aleman & Gruenwald 2004), due to the geometric dilution of radiation with distance from the source. In addition, DR in nebulae is also favored by the high abundance of free electrons. In this situation, the abundance of

plays no role. This is not the case when the radiation field is produced by a point source, as in the case of planetary nebulae (Black 1978) and Hii regions (Aleman & Gruenwald 2004), due to the geometric dilution of radiation with distance from the source. In addition, DR in nebulae is also favored by the high abundance of free electrons. In this situation, the abundance of  is basically controlled by the balance of formation by radiative association of H and H+(with rate kra) and destruction by DR (with rate kdr), and it is given by

is basically controlled by the balance of formation by radiative association of H and H+(with rate kra) and destruction by DR (with rate kdr), and it is given by  (see, e.g., Cecchi Pestellini & Dalgarno 1993).

(see, e.g., Cecchi Pestellini & Dalgarno 1993).

Shock waves could also lead to high  and electron abundances. For this reason, accurate and state-to-state resolved DR reaction rates are needed (Shapiro & Kang 1987; Takagi 2002; Shchekinov & Vasiliev 2006; Coppola et al. 2016). The updated DR reaction rates in the chemical evolution of shock waves through gas at high redshift, lead to changes in the fractional abundances of

and electron abundances. For this reason, accurate and state-to-state resolved DR reaction rates are needed (Shapiro & Kang 1987; Takagi 2002; Shchekinov & Vasiliev 2006; Coppola et al. 2016). The updated DR reaction rates in the chemical evolution of shock waves through gas at high redshift, lead to changes in the fractional abundances of  and HD+.

and HD+.

Figure 9 shows the results of simulations of shocks propagating with velocity vs=20 km s−1, compatible with typical supernova explosions, in a gas of primordial composition at redshift z = 10, 20, and 30 (see Coppola et al. 2016, for a description of the shock model). For T > 4000 K, beyond the range of validity of Eq. (10), we adopted a constant value equal to the rate at T=4000 K. Since the DR rate decreases with T above a few × 103 K, this choice may overestimate the true rate and thus provides a conservative lower bound on the abundances. In this context, the results demonstrate that, as is discussed in Section 4, when the ionization fraction is significant (as in shocks, ∼ 10−2−10−1 in these models), DR becomes an important channel for the destruction of  and HD+, competing with the fast charge exchange reactions that usually dominate in a nearly neutral medium. For example, in the high temperature range relevant for a high-speed shock, the DR rate of

and HD+, competing with the fast charge exchange reactions that usually dominate in a nearly neutral medium. For example, in the high temperature range relevant for a high-speed shock, the DR rate of  computed in this paper is a factor of ∼ 8−10 lower than the DR rate coefficient adopted by Coppola et al. (2016) on the basis of the cross sections calculated by Takagi (2002). Consequently, the abundance of

computed in this paper is a factor of ∼ 8−10 lower than the DR rate coefficient adopted by Coppola et al. (2016) on the basis of the cross sections calculated by Takagi (2002). Consequently, the abundance of  is a factor of ∼ 2−3 higher than that obtained by Coppola et al. (2016). On the other hand, at temperatures of a few ∼ 103 K the newly calculated DR rate of HD+is a factor of ∼ 2−3 higher than the value previously adopted, and consequently the abundance of HD+is slightly reduced.

is a factor of ∼ 2−3 higher than that obtained by Coppola et al. (2016). On the other hand, at temperatures of a few ∼ 103 K the newly calculated DR rate of HD+is a factor of ∼ 2−3 higher than the value previously adopted, and consequently the abundance of HD+is slightly reduced.

|

Fig. 8 Comparison of thermal rate coefficients for the DR of |

|

Fig. 9 Fractional abundances of |

5 Conclusions

We computed cross sections and thermally averaged rate coefficients summed for all five relevant molecular symmetries of the neutral from T=1 K up to T=4000 K electron temperatures considering temperature-dependent level population distributions. These new cross sections and rate coefficients can be adopted to model the kinetics of hydrogen-rich media in which the ionization fraction is significant. A primary field of application is planetary atmospheres and astrophysical plasmas in general, either in conditions typical of the early Universe (absence of metals and dust grains) or in the present-day partially ionized interstellar medium (as, for example, in planetary nebulae and HII regions). In all these environments, electronimpact induced RVT are the dominant excitation process of  and HD+, and DR is one of their main destruction channels. Our main findings are summarized as follows:

and HD+, and DR is one of their main destruction channels. Our main findings are summarized as follows:

With the new cross sections, significant differences with previously adopted thermal rate coefficients of DR are found (see Sect. 4 and Fig. 9);

The new rates produce substantial differences with respect to earlier results when introduced in astrochemical models, for example in models for the shock-induced chemistry of hydrogen and deuterium in a zero-metal gas (see Fig. 8).

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17344099.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR) via the project MONA; the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) via the GdR TheMS; the PCMI program of INSU (ColEM project, co-funded by CEA and CNES); the PHC Galilée programme between France and Italy; the DYMCOM project; the Fédération de Recherche “Fusion par Confinement Magnétique” (CNRS, CEA, and EUROfusion); Région Normandie, the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER), and LabEx EMC3 via the projects Bioengine, EMoPlaF, CO2-VIRIDIS, and PTOLEMEE; COMUE Normandie Université; the Institute for Energy, Propulsion and Environment (FR-IEPE); the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) via the Coordinated Research Project “The Formation and Properties of Molecules in Edge Plasmas”; and the European Union via COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology) Actions TUMIEE (CA17126), MW-GAIA (CA18104), MD-GAS (CA18212), COSY (CA21101), PLANET (CA22133), PROBONO (CA21128), PhoBioS (CA21159), DAEMON (CA22154), and DYNALIFE (CA21169). ERASMUS+ agreements between Université Le Havre Normandie and Politehnica University Timișoara, West University of Timișoara, and University College London are also gratefully acknowledged. IFS and MA acknowledge support from the French PEPR SPLEEN consortium via the project PLASMA-N-ACT. NP and IFS are grateful for support from the Romanian Ministry of Research and Innovation, project no. 10PFE/16.10.2018 (PERFORM-TECH-UPT) and “Mobility for the experienced researchers from diaspora” (MCD). JZsM thanks the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary for support under the FK-19 and Advanced-24 funding schemes (project nos. FK-132989 and 151196), and acknowledges support from the Program Hubert Curien “BALATON” (Campus France grant no. 49848TC) and NKFIH TÉT-FR 2023-2024 (2021-1.2.4-TÉT-2022-00069). JZsM is also grateful for the France Excellence Hongrie fellowship. DG acknowledges support from INAF grant PACIFISM. MA acknowledges support from French state aid under France 2030 (QuanTEdu-France; ANR-22-CMAS-0001). We thank A. Larson and D. Hvizdos for having provided some of their results for comparison with ours.

References

- Abdellahi El Ghazaly, M. O., Jureta, J., Urbain, X., & Defrance, P., 2004, J. Phys. B, 37, 2467 [Google Scholar]

- Agundez, M., Goicochea, J. R., Cernicharo, J., Faure A., & Roueff E., 2010, ApJ, 713, 662 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aleman, I., & Gruenwald, R., 2004, ApJ, 607, 865 [Google Scholar]

- Black, J. H., 1978, ApJ, 222, 125 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Black, J. H., & Van Dishoeck, E. F., 1987, ApJ, 322, 412 [Google Scholar]

- Cecchi, Pestellini C., & Dalgarno, A., 1993, ApJ, 413, 611 [Google Scholar]

- Chadney, J. M., Galand, M., Koskinen, T. T., et al. 2016, A&A, 687, A87 [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, K., Backodissa-Kiminou, D. R., Pop, N., et al. 2013, Phys. Rev. A, 87, 022702 [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, C. M., Longo, S., Capitelli, M., Palla, F., & Galli, D., 2011, ApJS, 193, 7 [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, C. M., Mizzi, G., Bruno, D., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 457, 3732 [Google Scholar]

- Djuissi, E., Bogdan, R., Abdoulanziz, A., et al. 2020, Rom. Astron. J., 30, 101 [Google Scholar]

- Epée Epée, M. D., Mezei, J. Zs, Motapon, O., Pop, N., & Schneider, I. F. 2016, MNRAS, 455, 276 [Google Scholar]

- Epée Epée, M. D., Motapon, O., Pop, N., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 512, 424 [Google Scholar]

- Friedl, R., Rauner, D., Heiler, A., & Fantz, U., 2020, PSST, 29, 015014 [Google Scholar]

- Galli, D., & Palla, F., 1998, A&A, 335, 403 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Galli, D., & Palla, F., 2013, ARA&A, 51, 163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gay, C. D., Abel, N. P., Porter, R. L., et al. 2012, ApJ, 746, 78 [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs, A., & Fitzgerald, M. P., 2022, ApJ, 164, 63 [Google Scholar]

- Glassgold, A. E., & Langer, W. D., 1973, ApJ, 186, 859 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hörnquist, J., Orel, A. E., & Larson, A., 2024, Phys. Rev. A, 109, 052806 [Google Scholar]

- Hvizdoš, D., Čurík, R., & Greene, C. H., 2025, Phys. Rev. A, 111, 012805 [Google Scholar]

- Kashinski, D. O., Talbi, D., Hickman, A. P., et al. 2017, J. Chem. Phys., 146, 204109 [Google Scholar]

- Krasheninnikov, S. I., Pigarov, A. Y., Soboleva, T. K., & Sigmar, D. J., 1997, J. Nucl. Mater., 241, 283 [Google Scholar]

- Le Petit, F., Roueff, E., & Le Bourlot, J., 2002, A&A, 390, 369 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lepp, S., Stancil, P. C., & Dalgarno, A., 2002, J. Phys. B, R57, 35 [Google Scholar]

- Mezei, J. Zs., Epée Epée, M. D., Motapon, O., & Schneider, I. F. 2019, Atoms, 7, 82 [Google Scholar]

- Motapon, O., Pop, N., Argoubi, F., et al. 2014, Phys. Rev. A, 90, 012706 [Google Scholar]

- Ngassam, V., Florescu, A., Pichl, L., et al. 2003, Eur. Phys. J. D, 26, 165 [Google Scholar]

- Niyonzima, S., Ilie, S., Pop, N., et al. 2017, At. Data Nucl. Data Tables, 115, 287 [Google Scholar]

- Niyonzima, S., Pop, N., Iacob, F., et al. 2018, PSST, 27, 025015 [Google Scholar]

- Parigger, C. G., Drake, K. A., Helstern, C. M., & Gautam, G., 2018, Atoms, 6, 36 [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, J. S., Hallinan, G., Desert, J. M., & Harding, L. K., 2024, ApJ, 966, 58 [Google Scholar]

- Pop, N., Iacob, F., Niyonzima, S., et al. 2021, At. Data Nucl. Data Tables, 139, 101414 [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, I. F., Dulieu, O., Giusti-Suzor, A., & Roueff, E., 1994, ApJ, 424, 983 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton, M. J., 1983, Rep. Prog. Phys. 46, 167 [Google Scholar]

- Shafir, D., Novotny, S., Buhr, H., et al. 2009, Phys. Rev. Lett., 102, 223202 [Google Scholar]

- Shchekinov, Y. A., & Vasiliev, E. O., 2006, MNRAS, 368, 454 [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, P. R., & Kang, H., 1987, ApJ, 318, 32 [Google Scholar]

- Shemansky, D. E., 1985, J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys., 90, 2673 [Google Scholar]

- Shuter, W. L. H., Williams, D. R. W., Kulkarni, S. R., & Heiles, C., 1986, ApJ, 306, 255 [Google Scholar]

- Stancil, P. C., Lepp, S., & Dalgarno, A., 1998, ApJ, 509, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Stotler, D., & Karney, C., 1994, Contrib. Plasma Phys., 34, 392 [Google Scholar]

- Strömholm, C., Schneider, I. F., Sundström, G., et al. 1995, Phys. Rev. A, 52, R320 [Google Scholar]

- Takagi, H., 2002, Phys. Scr., T96, 52 [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, S., Xiao, B., Kazuki, K., & Morira, M., 2000, Plasma. Phys. Contr. F., 42, 1091 [Google Scholar]

- Tennyson, J., & Miller, S., 2019, Phil. Trans. Roy. Soc. London Ser. A, 377, 2154 [Google Scholar]

- Tielens, A. G. G. M., 2013, Rev. Mod. Phys., 85, 1021 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- von Busch, F., & Dunn, G. H., 1972, Phys. Rev. A, 5, 1726 [Google Scholar]

- Waffeu Tamo, F. O., Buhr, H., Motapon, O., et al. 2011, Phys. Rev. A, 84, 022710 [Google Scholar]

- Weijun, Y., Alheit, R., & Werth, G., 1993, Z. Phys., 28, 87 [Google Scholar]

- Wünderlich, D., Dietrich, S., & Fantz, U., 2009, J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf., 110, 62 [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Left panel: electron-impact rotational excitation ( |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Left panel: electron-impact rotational excitation ( |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Left panel: electron-impact rotational excitation ( |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Left panel: electron-impact vibrational excitation ( |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Left panel: DR cross sections of |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Left panel: thermal rate coefficient for the DR of |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Thermally averaged and Franck-Condon averaged rate coefficients for DR of |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Comparison of thermal rate coefficients for the DR of |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Fractional abundances of |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.