| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A213 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Astrophysical processes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555053 | |

| Published online | 12 December 2025 | |

Particle acceleration at radiative supernova remnant shocks

Laboratoire d’étude de l’Univers et des phénomènes eXtrêmes, LUX, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, 92190 Meudon, France

★ Corresponding author: pierre.cristofari@obspm.fr

Received:

5

April

2025

Accepted:

20

October

2025

Context. Numerous astrophysical shock waves evolve in an environment where the radiative cooling behind the shock affects the hydrodynamical structure downstream, thereby influencing the potential for particle acceleration via diffusive shock acceleration (DSA).

Aims. We study the possibility for DSA to energize particles from the thermal pool and from preexisting cosmic rays at radiative shocks, focusing on the case of supernova remnants (SNRs).

Methods. We relied on a semi-analytical description of particle acceleration at collisionless shocks in the test-particle limit, estimating the particle spectrum, maximum energy, and total proton and electron content expected from SNRs throughout the radiative phase.

Results. Our results indicate that DSA at radiative shocks can lead to significant particle acceleration during the first few tens of kiloyears of the radiative phase. Although the associated multiwavelength emission from SNRs in the radiative phase may not be detectable with current observatories in most cases, the radiative phase is found to lead to substantial deviations from the canonical p−4 of the test-particle limit. The hardening and/or steepening is due to an interplay between a growing contribution of the reaccelerated term as the SNR volume expands and the effects of adiabatic and radiative losses on trapped particles as particles are confined for a longer time. The slope of the cumulative proton and electron spectra over the SNR lifetime thus depends on the environment in which the SNR shock propagates, and on the duration of the radiative phase during which DSA can take place. Overall, DSA in the radiative phase can lead to a total electron spectrum steeper than the proton spectrum, both at SNRs from thermonuclear and core–collapse SNe. Finally, we comment on the case of young radiative SNRs (in the first month to a few years after the explosion) for which the denser environments (with mass-loss rates of Ṁ ∼ 10−1 − 1 M⊙/yr) tend to inhibit DSA.

Key words: astroparticle physics / shock waves / cosmic rays / ISM: supernova remnants

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Astrophysical shock waves are known to be the place of efficient particle acceleration up to the very high-energy (VHE) domain through diffusive shock acceleration (DSA) (Axford et al. 1977; Krymskii 1977; Bell 1978; Blandford & Ostriker 1978). The observation of VHE gamma rays at various shock waves, such as supernova remnants (SNRs) (H.E.S.S. Collaboration 2018a), gamma-ray bursts (Piran 2004), large-scale shocks in galaxy clusters (Blasi et al. 2007), relativistic jets in active galactic nuclei (AGNs) (Valtaoja & Terasranta 1995), or pulsar wind nebulae (Bednarek & Bartosik 2003) is seen as a direct indication that strong collisionless adiabatic shocks are indeed accelerating particles through DSA. However, the ability of radiative shocks to accelerate particles remains a subject of debate.

In radiative shocks, efficient post-shock cooling significantly alters the hydrodynamical structure, causing the downstream temperature and velocity drop rapidly, while the density rises. These conditions are generally unfavorable for efficient particle acceleration (Raymond 1979; Binette et al. 1985; Bertschinger 1986; Cioffi et al. 1988; Drake 2005). Several factors contribute to this limitation:

1) The loss of a large amount of energy to radiation reduces the energy available for acceleration; 2) the lower temperature weakens the generation of turbulent motions in the post-shock region, in turn leading to weaker magnetic turbulence – crucial for scattering particles back and forth across the shock; 3) the rise of the post-shock density tends to make the plasma collisional, in which suprathermal particles can be thermalized before they enter the acceleration process. 4) the residence time of particles in the thin layer around the shock is reduced, thereby limiting the acceleration process.

Nevertheless, in many cases, cooling is not instantaneous, and on some level, the physical conditions close to the shock discontinuity may still support DSA. Thus, some radiative shocks might energize particles from the thermal pool or reaccelerate preexisting cosmic rays (CRs). Radiative shocks have been observed or predicted in a wide variety of environments, including accretion shocks of young stellar objects (Matsakos et al. 2013), bow shocks of runaway stars (Carretero-Castrillo et al. 2025), perturbed magnetospheres of neutron stars (Beloborodov 2023), or accreting black holes (Okuda & Singh 2021).

The detection of novae in the VHE gamma-ray domain is a notable example of radiative shocks efficiently accelerating particles via DSA (Metzger et al. 2015; Li et al. 2017; Vurm & Metzger 2018; H.E.S.S. Collaboration 2022; Phan et al. 2025).

The case of SNRs is particularly instructive, as DSA is clearly active during the free expansion (FE) and adiabatic phases, but often overlooked during the radiative phase of evolution (Ptuskin & Zirakashvili 2005; Reynolds 2008; Schure et al. 2010; Caprioli 2012; Celli et al. 2019). While multiwavelength observations (Vink 2012) do not support efficient DSA during the radiative phase, which typically begins 20–40 kyr after the supernova (SN) explosion (for a Type Ia, and ≲10 kyr for core-collapse SNe), recent studies suggest that the radiative phase could still contribute significantly. It may lead to hard spectra (∝p−3) of accelerated particles, such as protons, electrons, and nuclei, up to several hundred giga-electronvolts (Zirakashvili & Ptuskin 2022), and enhance the brightness from radio to VHE gamma rays (Diesing et al. 2024; Diesing & Gupta 2025). A similar scenario arises in very young SNRs, where shocks expand into the dense wind of the progenitor star, which can become radiative and hinder particle acceleration due to high cooling rates (Fang et al. 2020; Pitik et al. 2023).

In this paper, we examine the radiative phase of SNRs and investigate its potential for particle acceleration. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the structure of radiative shocks and the associated mechanisms of particle acceleration. Section 3 applies this framework to the case of SNRs. In Section 4, we present and discuss our results. Finally, Section 5 summarizes our conclusions.

2. Radiative shocks

2.1. Shock structure

In astrophysical plasmas with temperatures of T ≳ 104 K, hydrogen is sufficiently ionized so that collisional excitations of atoms and ions are primarily driven by electron collisions. At low densities, these excitations are typically followed by radiative decay, resulting in energy loss. The associated radiative cooling function generally takes the form

with ne and nH the density of electrons and hydrogen, respectively, and Λ the rate of dissipation of thermal energy per unit volume (Draine 2011). A decent approximation for fcool was proposed in Draine (2011):

Another widely used prescription is from (Chevalier & Fransson 1994):

this expression is adopted as a reference in the following. The typical timescale associated with cooling, in the case of isobaric cooling, is  .

.

Let us consider the case of a one-dimensional, infinite plane shock. The physical quantities (velocity, pressure, density, and temperature) downstream can be estimated through the Rankine-Hugoniot conditions, obtained by writing the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy. Using index 1 for quantities upstream and 2 for downstream:

where γ is the adiabatic index, and  is the upstream Mach number, cs1 being the sound speed upstream. For strong shocks where

is the upstream Mach number, cs1 being the sound speed upstream. For strong shocks where  , and assuming γ = 5/3, the above relations reduce to

, and assuming γ = 5/3, the above relations reduce to  , and

, and  .

.

To take into account the cooling in the mass, momentum, and energy conservation equation, the cooling function, Λ, needs to be included downstream.

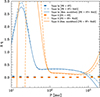

The cooling term, Λ ∝ fcool, becomes important when the temperature downstream decreases, i.e., when the shock speed decreases. The effect of cooling on the shock structure is illustrated in Fig. 1, solving Eqs. (8)–(10) with an Eulerian scheme. The integration was started just downstream of the shock front with post-shock values determined from the Rankine–Hugoniot conditions. The solution was then extended downstream until the temperature reaches a prescribed floor value, at which point outflow (zero-gradient) boundary conditions were imposed.

|

Fig. 1. Velocity, density, and temperature of the fluid across the shock, for Mach numbers upstream |

2.2. Particle acceleration

The spectrum of accelerated particles at the shock can be estimated by solving the transport equation at a one-dimensional infinite plane shock,

where f0 is the spectrum of accelerated particles at the shock, and  the injection term at the shock. At radiative shocks, the cooling induces variations in the fluid velocity downstream, i.e., u2 is a function of the space coordinate (x). Assuming that particles of momentum p can diffuse up to a distance of x ∼ D2/u2, the dependence on the space coordinate can be written as a dependence on momentum. The spectrum at the shock obtained is

the injection term at the shock. At radiative shocks, the cooling induces variations in the fluid velocity downstream, i.e., u2 is a function of the space coordinate (x). Assuming that particles of momentum p can diffuse up to a distance of x ∼ D2/u2, the dependence on the space coordinate can be written as a dependence on momentum. The spectrum at the shock obtained is

where rrub is the compression ratio from upstream to immediately downstream the shock, and Rtot = u1/u2(p) is the overall compression factor. Several studies have examined in detail the particle spectrum at shocks, accounting for a range of physical effects such as the presence of preexisting CRs (Blasi 2002, 2004), nonlinear feedback from efficient particle acceleration (Amato & Blasi 2005, 2006), and modifications due to spatial variations in the velocity profile (Petruk & Kuzyo 2024). While these effects are certainly important in specific contexts, they are beyond the scope of the present work and are therefore not included in our model.

The maximum momentum of the accelerated particles, pmax, is not included in Eq. (12) and can be accounted for by introducing an exponential suppression. For DSA to occur, the shock needs to be strong, and the medium “sufficiently” ionized. We assumed that the condition on ionization was met (Sutherland & Dopita 2017), if only because we were considering shocks expanding in the warm ISM. As the shock slows down, the Mach number decreases. We verified that the shock remains supersonic (ℳ > 1), and assumed that DSA can occur at relatively weak shocks with Mach numbers of ℳ ∼ 2–3. Although particle acceleration is typically associated with strong, high-Mach-number shocks, both theoretical and observational studies have shown that even low-Mach-number shocks (ℳ ∼ 2–3) can accelerate particles under favorable conditions. In particular, hybrid and particle-in-cell simulations have demonstrated efficient ion and electron acceleration at quasi-parallel low Mach shocks (Guo & Giacalone 2013; Caprioli & Spitkovsky 2014; Park et al. 2015). This has been further explored in the context of high-beta astrophysical plasmas, such as those found in galaxy clusters, where low Mach shocks are common (Guo et al. 2014). Cosmological simulations also support the role of such shocks in generating CRs (Wittor et al. 2017). In situ measurements in the solar wind provide additional observational evidence of particle acceleration at low-Mach-number collisionless shocks (Wilson et al. 2017)

Moreover, for DSA to take place, the shock needs to be collisionless. A usual criterion to characterize collisionless shocks relies on the idea that the transition from upstream to downstream occurs on a scale smaller than the mean free path (mfp) of particles. The mfp downstream can be estimated at the time needed for a projectile to be deflected by 90°, and typically reads (Draine 2011):

We assumed that particles can be efficiently accelerated as long as their mfp is much larger than their Larmor radius (mfp ≫rL), and used this criterion to estimate the maximum energy of accelerated particles. One could argue, however, that the conditions for acceleration may no longer hold in regions where cooling significantly affects the shock structure (where the temperature decreases and the density increases) and where the shock may no longer remain collisionless. In practice, this is not a concern, since the Larmor radius remains smaller than the typical cooling length (rL ≲ Lcool).

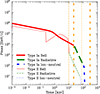

The typical spectra at the shock are illustrated in Fig. 2. For low Mach numbers ( ), the maximum momentum of accelerated particles is low enough that the slope of accelerated particles (α → 3) is not visible. For large Mach numbers

), the maximum momentum of accelerated particles is low enough that the slope of accelerated particles (α → 3) is not visible. For large Mach numbers  ), α → 4 is recovered for a strong shock.

), α → 4 is recovered for a strong shock.

|

Fig. 2. Spectra of accelerated particles at the shocks for various Mach numbers. |

2.3. Limiting effects

Ion-neutral damping can be important at SNR shocks propagating through a partially ionized medium, as it can suppress the growth of magnetohydrodynamic waves, and thus limit magnetic field amplification, and influence CR acceleration. As the temperature drops downstream, the gas downstream can recombine more easily, and thus the fraction of neutral hydrogen can increase, favoring ion-neutral damping. Moreover, slower shocks are less efficient at ionizing the upstream medium, allowing for a significant fraction of neutral to pass downstream. Ion-neutral damping has been discussed upstream (Draine & McKee 1993; O’C Drury et al. 1996; Bykov et al. 2000; Ptuskin & Zirakashvili 2003) and downstream (Achterberg & Blandford 1986).

As was discussed in O’C Drury et al. (1996), ions and neutral are coupled (‘oscillating’) together provided that the wave frequency remains smaller than the typical ion-neutral collision frequency. If the wave frequency is greater than the collision frequency, however, ions and neutrals can be treated as decoupled. In other words, two regimes (coupled and decoupled) are delimited by an energy, Ecoup, and CRs of energy E > Ecoup are in the coupled regime. The energy, Edamp, above which the damping to ion-neutral collisions becomes important was estimated by equating the flux of accelerated particles advected downstream, and the flux of particles leaving the system, due to the damped waves incapable of confining them. When Edamp > Ecoup, the ion-neutral damping is considered to be inefficient; this condition can be rewritten as (Padovani et al. 2015, 2016)

with x being the ionization fraction, and

where Γ is the particle Lorentz factor, β = Γ−1(Γ2 − 1)1/2, and  is the mean particle mass in units of proton mass. Typically,

is the mean particle mass in units of proton mass. Typically,  for a fully ionized gas, and

for a fully ionized gas, and  for a neutral gas.

for a neutral gas.

The phase of the ISM in which the shock evolves is especially important, since the criterion of Eq. (14) depends strongly on the ionization fraction, x. Typically, SNR shocks are expected to be expanding in the warm ionized medium (WIM, T ≈ 8000 K, n0 ≈ 0.2 − 0.5 cm−3, volume filling factor ∼20 − 50, x = 0.6 − 1) or in the warm neutral medium (WNM, T ≈ 8000 K, n0 ≈ 0.2 − 0.5 cm−3, volume filling factor ∼10 − 20, x = 0.01 − 0.05) (Mihalas & Binney 1981). In the WNM, the low ionization fraction makes the condition of Eq. (14) soon after the shock enters the radiative phase ∼20 − 40 kyr, whereas the ionization fraction found in the WIM, potentially close to 1, relaxes this condition. Moreover, at shocks (and especially SNR shocks) several radiation fields can ionize the ISM upstream and downstream: this is the case for external radiation fields (Sutherland & Dopita 2017), as well as self-irradiated shocks, which emit in the UV and X-ray domain and have been shown, even for low-velocity shocks (∼ a few 10 km/s) to substantially affect the ionization fraction, as well as the thermodynamical structure of the shock (Sarkar et al. 2021; Godard et al. 2024a,b). In addition to the shock structure modification, and ion-neutral damping, DSA itself is expected to be modified intrinsically at collisionless shocks propagating in partially ionized media (Morlino et al. 2013). A high level of ionization is required for DSA, and we thus assume that either the phase of the ISM in which the shock expands (e.g., in the WIM phase) or other additional sources, provide the required conditions for ionization.

3. Supernova remnants

3.1. Dynamics of supernova remnant shocks

For a typical remnant from a Type Ia SN (thermonuclear), expanding in a homogeneous ISM, the time evolution of the shock radius, rsh, and velocity, vsh, in the FE and Sedov-Taylor (ST) phases is well described by self-similar solutions that have been derived in several works (Chevalier 1982; Truelove & McKee 1999; Ptuskin & Zirakashvili 2005). For instance, in the adiabatic ST phase,

The adiabatic phase typically ends at tST when the cooling time is on the order of the age of the SNR. Considering the prescription of Chevalier & Fransson (1994), this leads to

Considering the prescription of Draine (2011) for the cooling function leads to a tST a factor of 2 longer. When the shock enters the radiative phase, the shock velocity and radius scale as vsh ∝ t−5/7 and rsh ∝ t2/7 (Cioffi et al. 1988; Bandiera & Petruk 2004; Gintrand et al. 2020). Other works, relying for example on 1D or 2D simulations, have also found a power-law index closer to 0.33 (Blondin et al. 1998). The duration of the radiative phase can be estimated by requiring the shock velocity to remain a few times larger than the sound speed in the ISM, i.e., vsh ≳ 4 − 5cs with cs = (γkBT/m)1/2 ≈ 10T41/2 km/s with T = T4104 K. This condition also ensures that the shock velocity remains super-Alfvènic, and leads to an estimate of the duration of the radiative phase:

The SNRs from a Type II (core–collapse) SN typically expand into a complex medium shaped by the evolution of their massive progenitor stars. During the main sequence, fast stellar winds carve out a low-density, hot bubble in pressure equilibrium with the ISM. In the red supergiant (RSG) phase, a slower, denser wind develops. After the SN explosion, the shock propagates through this dense wind, then the hot bubble, and finally into the ISM. The RSG wind density is  , with Ṁ ∼ 10−5 M⊙/yr, uw ∼ 106 cm/s and m ∼ 1.27mp the mean mass per hydrogen nucleus. The bubble density is

, with Ṁ ∼ 10−5 M⊙/yr, uw ∼ 106 cm/s and m ∼ 1.27mp the mean mass per hydrogen nucleus. The bubble density is  , following Weaver et al. (1977), with a typical main-sequence lifetime of ∼Myr (Longair 1994). The transition radius between the RSG wind and the hot bubble is typically located at a distance of

, following Weaver et al. (1977), with a typical main-sequence lifetime of ∼Myr (Longair 1994). The transition radius between the RSG wind and the hot bubble is typically located at a distance of  , and the hot bubble radius is

, and the hot bubble radius is  . Due to the structured medium, self-similar solutions are not easily found. However, under the thin-shell approximation – i.e., assuming that the swept-up material accumulates in a thin shell – an analytical treatment is still possible (e.g., Ostriker & McKee 1988; Bisnovatyi-Kogan & Silich 1995). For a spherically symmetric case, Ptuskin & Zirakashvili (2005) derived expressions for the shock velocity, vsh(Rsh), and age, t(Rsh). For typical type II SNe, we adopted ESN = 1051 erg, Mej = 5 M⊙, and Ṁ = 10−5 M⊙/yr.

. Due to the structured medium, self-similar solutions are not easily found. However, under the thin-shell approximation – i.e., assuming that the swept-up material accumulates in a thin shell – an analytical treatment is still possible (e.g., Ostriker & McKee 1988; Bisnovatyi-Kogan & Silich 1995). For a spherically symmetric case, Ptuskin & Zirakashvili (2005) derived expressions for the shock velocity, vsh(Rsh), and age, t(Rsh). For typical type II SNe, we adopted ESN = 1051 erg, Mej = 5 M⊙, and Ṁ = 10−5 M⊙/yr.

Throughout the evolution of the SNR shock, the magnetic field strength at the shock front undergoes significant variations. In the early stages, observations of X-ray filaments provide clear evidence that the magnetic field is substantially amplified compared to typical ISM values (Vink 2012). Several mechanisms have been proposed to account for this amplification at the shock. At young SNR shocks (in the FE and early ST phase), the main mechanism responsible for magnetic field amplification is expected to be due to the streaming of CRs’ excited nonresonant instabilities in the plasma upstream as the stream from the shock (Bell 2004; Schure & Bell 2013; Bell et al. 2013), often referred to as the Bell mechanism, which typically lead to a magnetic field of  (see e.g., Eq. (12) in Cristofari et al. 2021). To account for our incomplete knowledge of the problem, and the fact that other mechanisms might come into play and complicate the picture, several groups have proposed various physically motivated prescriptions, where the magnetic field is parametrized to account for nonlinear effects as in Morlino & Caprioli (2012), Diesing & Caprioli (2019), leading to

(see e.g., Eq. (12) in Cristofari et al. 2021). To account for our incomplete knowledge of the problem, and the fact that other mechanisms might come into play and complicate the picture, several groups have proposed various physically motivated prescriptions, where the magnetic field is parametrized to account for nonlinear effects as in Morlino & Caprioli (2012), Diesing & Caprioli (2019), leading to  , and referred to it as the “resonant modified” case (see discussion and Eqs. (5)–(11) in Cristofari et al. 2021). Here we work under the usual assumption the nonresonant (Bell) streaming instability sets the value of the amplified magnetic field, while the conditions for the excitation of these modes are met.

, and referred to it as the “resonant modified” case (see discussion and Eqs. (5)–(11) in Cristofari et al. 2021). Here we work under the usual assumption the nonresonant (Bell) streaming instability sets the value of the amplified magnetic field, while the conditions for the excitation of these modes are met.

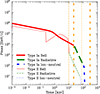

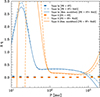

In addition to these prescriptions, we imposed in our estimate of pmax the conditions discussed in Sect. 2.2 that limit the maximum energy when the shock becomes radiative. In the radiative phase of typical SNRs, the conditions for excitations of instabilites that lead to magnetic field amplification are not met, and the magnetic fied is thus assumed to remain unamplified upstream, and compressed downstream by a factor of  . Overall, the maximum momentum obtained is illustrated for a typical Type Ia SNR shock in Fig. 3, and is typically found between a few times ∼103 GeV/c and ∼1 GeV/c in the radiative phase. For the Type II, in the radiative phase, pmax ≲ 103 GeV/c. For both types, the limitation of pmax due to ion-neutral damping becomes important before the naïve estimate of the end of the radiative phase, typically ∼150 kyr (Type Ia) and ∼60 kyr (Type II); also, these values are not well constrained (see discussion in Sect. 2.2 and Sect. 3).

. Overall, the maximum momentum obtained is illustrated for a typical Type Ia SNR shock in Fig. 3, and is typically found between a few times ∼103 GeV/c and ∼1 GeV/c in the radiative phase. For the Type II, in the radiative phase, pmax ≲ 103 GeV/c. For both types, the limitation of pmax due to ion-neutral damping becomes important before the naïve estimate of the end of the radiative phase, typically ∼150 kyr (Type Ia) and ∼60 kyr (Type II); also, these values are not well constrained (see discussion in Sect. 2.2 and Sect. 3).

|

Fig. 3. Maximum momentum of accelerated particles at an SNR from a Type Ia (thick lines) and Type II (thin) progenitor. The dashed orange and black lines correspond to the beginning and end of the radiative phase. The solid red lines correspond to the pmax associated with a magnetic field amplification driven by the growth of nonresonant streaming instabilities (Bell) (Schure & Bell 2013), the dashed green lines to the radiative phase (Section 2.2), and the dotted blue line to the ion-neutral damping (Section 2.3). |

3.2. The proton and electron content

We computed the spectrum of protons accelerated throughout the life of the SNR, up to the end of the radiative phase, under the assumption that particle acceleration proceeds in the radiative phase as was discussed in the previous section. The calculation was carried out as in Cristofari et al. (2020, 2021), and we refer the reader to Cristofari et al. (2021) for the analytical expressions. Until the end of the radiative phase, the approach distinguishes between the particles accelerated and trapped inside the SNR suffering adiabatic losses (and radiative losses for electrons), and the particles at the highest energy continuously escaping in the ISM. In addition, the protons and electrons reaccelerated from Galactic CRs were computed. These contributions can be estimated by assuming that the protons and electrons in front of the SNR shocks are the ones of the local interstellar spectrum, parametrized by (Bisschoff et al. 2019), in agreement with the Voyager I (Cummings et al. 2016) and PAMELA data (Adriani et al. 2011).

At the shock, the spectrum of reaccelerated particles is

with s = 3r/(r − 1) with r the compression factor felt by reaccelerated particles. The associate cumulative spectrum of reaccelerated particles reads

This is computed assuming that the change in momentum of a particle injected at a time, t′, with momentum, p′, due to losses can be written as

where σT is the Thomson cross section. ℒ accounts for adiabatic energy losses, in terms of a change in volume between the two times, t′ and t:

with ρdown the density downstream. If the expansion is adiabatic, ρdown ∝ P1/γ ∝ (ρvsh2(t))1/γ, and ρ is the gas density upstream of the shock. For protons, synchrotron losses are negligible, while for electrons both adiabatic and radiative losses are important.

4. Results

4.1. The cumulative proton and electron spectra

The total proton and electron spectra at SNRs from the Type Ia and Type II prototypes were computed as in Cristofari et al. (2021), with the main additions being the extension to the radiative phase discussed in Sect. 2 and Sect. 3 to account for the spectrum and maximum momentum of accelerated particles at the radiative shock, and for the reacceleration of preexisting CRs. As is shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, from 10 GeV to 10 TeV the inclusion of the radiative phase produces a “bump” in the proton spectra, i.e., harder than p−4 below a few tera-electronvolts and steeper above. This is mostly due to the component from reaccelerated protons, which scales with the volume of the SNRs (thus becoming more important with time), and the fact that at later times the spectra of accelerated particles become harder (closer to p−3) as the shock becomes radiatiave. For electrons, the radiative losses drastically affect the particles trapped inside the SNRs (both accelerated and reaccelerated), so that the dominant component is due to the escaping particles. Several bumps appear, due to the evolution of the maximum energy of accelerated electrons throughout the ST and radiative phases. At low energy (around 10 GeV), the pile-up of trapped particles that cooled radiatively contributes to the total spectrum.

|

Fig. 4. Protons (left panel) and electrons (right panel) accelerated throughout the life of an SNR from a Type Ia SN. The thin orange, pink, and green lines correspond to the particles trapped inside the SNR, escaping the SNR, and reaccelerated from the Galactic CRs, respectively. The dashed lines correspond to the FE and ST phases, while the solid lines additionally take into account the radiative (RAD) phase. The thick dashed blue line corresponds to the total contribution of the FE and ST phases. The thick solid lime line corresponds to the total contribution of the FE, ST, and RAD phases. The bottom panels show the slope of the spectrum sum of all components, for the ST and FE phase (dashed blue), and including the radiative phase (solid lime). |

|

Fig. 5. As in Fig. 4, but for a SNR from a Type II SN, ESN = 1051 erg, Ṁ = 10−5 M⊙/yr, and Mej = 5 M⊙. |

4.2. The electron–proton spectral index difference

During the radiative phase of the SNR, particle trapping can significantly increase the radiative losses experienced by electrons. As is shown in Fig. 6, at times ≳100 kyr this tends to make the electron spectra steeper than in the earlier phases of the SNR evolution. Assuming that the accelerated protons and electrons trapped inside the SNR remain confined until the end of the radiative phase (∼300 kyr for a Type Ia, and ∼70 kyr for a Type II), the electron spectra are found to be significantly steeper than the proton spectra for both type, as is illustrated in Fig. 7, with a typical difference at 103 ≳ p ≳ 102 mc of ∼0.1 − 0.2 (Type II), or ∼0.3 (Type Ia). Considering a different prescription for the magnetic field, for instance the resonant modified case discussed in Sect. 3, does not significantly affect our results. In our calculation, at p ≲ 102 mc, the electron–proton spectral index difference becomes large due to the accumulation of electrons that have cooled via radiative losses. However, this part of the spectrum should be interpreted with caution, given the current uncertainties on particle confinement efficiency and the actual role of reacceleration at SNR shocks, especially late in the radiative phase.

|

Fig. 6. Proton (top), electron (middle), and proton–electron spectral index difference, Δq = qelectrons − qprotons (bottom), distributions. Colored lines (from thin to thick) show the effect of increasing the SNR lifetime from 20 kyr to 300 kyr, assuming a Type Ia SN progenitor. |

|

Fig. 7. Electron–proton spectral index difference, Δq = qelectrons − qprotons, for Type Ia (blue lines) and Type II (orange lines). The thick lines correspond to the results considering the FE and ST phases, the thin solid lines additionally include the radiative phase considering Bell prescription for the magnetic field, and the dashed lines considering the resonant modified prescription for the magnetic field. |

4.3. Discussion

Several assumptions should be kept in mind, as they could affect the proton and electron spectra presented in the previous section, although they are not expected to alter the overall conclusions of this study. First, we worked under the assumption that the trapped particles, whether accelerated or reaccelerated, are trapped until the end of the radiative phase, suffering adiabatic and radiative losses. This is of course a strong assumption, as it is likely that in time the trapping and confinement of the accelerated particles could become inefficient, and thus a fraction of these particles could start leaking in the ISM. In addition, we worked under the assumption that as the SNR shocks expand, the magnetic field downstream is advected without suffering any damping (Pohl et al. 2005; Marcowith & Casse 2010; Ressler et al. 2014; Tran et al. 2015; Wilhelm et al. 2020). Such damping has been proposed in several works, and could be especially important for the radiative losses suffers by electrons, which typically scale with ∝B2.

The duration of the radiative phase and/or the onset of the ion-neutral damping or other effects that could completely prevent particle acceleration through DSA are still not well constrained by observations and theoretical works, and the estimates presented in this work have to be taken with caution. Fig. 6 illustrates the importance of the duration of the radiative phase in which DSA can take place. For instance, in the case of efficient trapping, a radiative phase longer than ≳100 kyr is required to ensure that the electron-proton spectral difference is Δq > 0.1. If the confinement of trapped particles is only partially efficient, the cumulative electron spectrum may steepen more rapidly, causing Δq to reach values of 0.2 − 0.3 at earlier times. In this work, we assumed that at strong shocks the instantaneous spectra of accelerated particles follow ∝p−4 (i.e. ∝E−2 for E ≫ 1 GeV), neglecting nonlinear effects that may introduce deviation in the accelerated spectra (e.g., due to efficient particle acceleration (Malkov & Drury 2001; Amato & Blasi 2005), or due to the drift of scattering centers upstream or downstream (Zirakashvili & Ptuskin 2008; Caprioli et al. 2020; Cristofari et al. 2022). These effects were included for a more complete description of the cumulative spectrum, but overall, since they affect electrons and protons at the shock in the same manner, they do not impact our result for Δq.

The idea that the radiative phase contributes to the total spectrum is compatible with the fact that all SNR shocks in the radiative phase have not been detected as high-energy particle accelerators (via radio or gamma-ray observations). Indeed, in the radiative phase, the shock velocity, vsh, is rather low (few 100 km/s), and thus the available ram pressure (ρvsh2) is substantially smaller than in the FE or ST phase; thus, at any given time, the instantaneous amount of particle accelerated is substantially smaller than in the FE or ST phase, and the associated emission from nonthermal particles is below telescopes’ sensitivities. In the approach adopted here, Type Ia SNR shocks can typically contribute up to ∼200 kyr, leading to a typical shock radius of rsh ∼ 35 pc. This suggests that very low-velocity SNRs expand in the ISM and have not been detected through multiwavelength observations. This is somewhat expected in the sense that in addition to the decrease in the ram pressure,  , and thus of the typical energy density of accelerated particles at the shock, the angular extension of such low-velocity evolved shocks would make their detection highly challenging.

, and thus of the typical energy density of accelerated particles at the shock, the angular extension of such low-velocity evolved shocks would make their detection highly challenging.

The Galactic SN rate is often claimed to be ∼3/century (with values estimated from various methods found between ≈2.5/century and ≈5.7/century Strom 1994; Tammann et al. 1994; Smartt 2009; Adams et al. 2013). As was discussed above, the lifetime of SNRs can vary substantially from one SN to the other, but typically, if the end of the radiative phase happens at ∼100 kyr, this means that currently there should be ∼3000 SNR in the Galaxy, when radio surveys have so far revealed ≈310 SNRs (Green 2025), suggesting that 90% of the Galactic SNRs would remain undetected. Those would a priori be the oldest, radiative, and most extended SNRs.

Furthermore, the idea that a substantial fraction of the radiative phase can contribute to particle acceleration up to ≳102 − 103 GeV is also in favor of a reduced CR efficiency, closer to ∼0.01 of the ram pressure than the ∼0.1 often used to fit gamma-ray observations of SNRs (H.E.S.S. Collaboration 2018b), or to account for gamma-ray observations of the Galactic plane (Acero et al. 2016). Thus if the radiative phase indeed contributes to particle acceleration, such an increase in the duration of the accelerating phase implies a reduction of the efficiency of acceleration.

4.4. Very young radiative supernova shocks

Core-collapse SNe typically explode into the dense wind of a late-stage massive star, characterized by a mass-loss rate, Ṁ, and wind velocity, uw, leading to a density profile of  . The high density enhances radiative cooling, thereby reducing the maximum momentum attainable by accelerated particles. During the late stages of massive star evolution, the mass-loss rate can vary substantially, and a wide range of values is reported in the literature. Depending on the ejecta mass and the total explosion energy of the SN, the resulting shock velocity in the wind is well described by self-similar solutions (Tang & Chevalier 2017).

. The high density enhances radiative cooling, thereby reducing the maximum momentum attainable by accelerated particles. During the late stages of massive star evolution, the mass-loss rate can vary substantially, and a wide range of values is reported in the literature. Depending on the ejecta mass and the total explosion energy of the SN, the resulting shock velocity in the wind is well described by self-similar solutions (Tang & Chevalier 2017).

The case of very young SN shocks (from days to about a year after the explosion) is of particular interest because, unlike the typical radiative SNR shocks (≳20 kyr), the shock speed and density are sufficiently high to excite Bell instabilities in the plasma, leading to significant amplification of the magnetic field (Marcowith et al. 2018). At the same time, the high density can make radiative cooling important. These conditions combine properties usually associated with both young, non-radiative SNRs and old, radiative SNRs, providing a unique environment in which to study the interplay between magnetic field amplification, particle acceleration, and radiative losses.

The maximum energy of accelerated particles, estimated with the criteria described in Sect. 2.2, is illustrated in Fig. 8. On the first day, for mass-loss rates of Ṁ ∼ 10−2−1 M⊙/yr, cooling suppresses acceleration. At one month and one year, this limitation persists only for mass-loss rates on the order of Ṁ ∼ 1 M⊙/yr. For lower mass-loss rates, Ṁ ≲ 10−3 M⊙/yr, particle energies in the tera-electronvolt range can typically be reached at these timescales, opening up interesting prospects for detection with next-generation observatories (Cherenkov Telescope Array Consortium 2019; Cao et al. 2024).

|

Fig. 8. Maximum momentum of accelerated particles at a young SNR shock expanding in the dense wind of the progenitor star, as a function of density and shock velocity. The green circles, crosses, and triangles show the typical values reached 1 day, 1 month, and 1 year after the SN explosion, respectively. The size of the symbols increases with Ṁ from 10−5 to 1 M⊙/yr. |

5. Conclusions

Radiative cooling downstream of astrophysical shock waves significantly impacts the shock structure –affecting temperature, velocity, and density – and, consequently, influences the potential for particle acceleration through DSA. In the context of SNRs, the contribution of the radiative phase to particle acceleration is often overlooked, as it is typically considered subdominant compared to the free-expansion and adiabatic phases. However, our results suggest that the radiative phase can have a substantial impact on the total particle spectra. For protons, the cumulative spectra are found to be harder than the canonical test-particle spectrum, p−4, for p ≲ 103 GeV/c, and steeper above this energy. The electron spectra are also affected, showing several bumps and deviations from p−4, mainly due to the combined effects of the time evolution of the maximum electron momentum and the losses suffered by confined electrons.

The contribution of the radiative phase leads to an electron–proton spectral index difference of Δq ∼ 0.1–0.2 (Type II) and Δq ∼ 0.3 (Type Ia) for 103 ≳ p ≳ 102 GeV/c, which can be of great interest in the search for the sources of Galactic CRs (Blasi 2013; Gabici et al. 2019). The spectral hardening/steepening and deviations from p−4 due to the radiative phase should also be examined in the context of the precision measurements of protons by DAMPE or CALET (An et al. 2019; Adriani et al. 2022) and other experiments, as they may play a role in shaping the local CR spectrum.

Several aspects of our study need to be examined more thoroughly to clarify the role of the radiative phase, including its duration, the damping of the downstream magnetic field, the maximum energy of accelerated particles, and the shock’s ability to confine particles within the SNR. Additionally, other aspects, such as instabilities in the cool shell that can substantially complicate the picture and would need to be studied (Chevalier & Imamura 1982; Binette et al. 1985). Several theoretical works relying on HD simulations have discussed the complexity of the structure of radiative shocks (Chevalier & Imamura 1982), as several instabilities can develop, such as the “nonlinear thin-shell instability”, which can deform the shock front, leading to a corrugated shock (Vishniac 1994; Strickland & Blondin 1995), and affect particle acceleration (Steinberg & Metzger 2018).

The case of SNRs illustrates how low-velocity radiative shocks may play an important role in the Galactic ecosystem of accelerated charged particles. More generally, even if these shocks (such as old SNRs) remain so far often undetected, they can still contribute to injecting mechanical energy and electromagnetic turbulence in the ISM, thereby affecting not only the energization of particles but also the properties of the ISM that regulate the transport of CRs. In the coming years, the multiwavelength study of astrophysical accelerators across the electromagnetic spectrum, from next-generation radio observatories such as SKAO (van Haarlem et al. 2013) to gamma-ray observatories such as CTAO (Cherenkov Telescope Array Consortium 2019), will help clarify the role of radiative shocks in particle acceleration. Additionally, laboratory experiments with laser-generated radiative shocks have shown promising potential for studying particle acceleration in controlled settings (Keilty et al. 2000; Reighard et al. 2006; Yao et al. 2021; Sakawa et al. 2024).

Acknowledgments

PC acknowledges support from the “GALAPAGOS” PSL Starting Grant. PC thanks the anonymous referee for constructive comments, and is grateful to Pasquale Blasi, Benjamin Godard, Antoine Gusdorf, Guillaume Pineau des Forêts, and Guillaume Vigoureux for insightful discussions.

References

- Acero, F., Ackermann, M., Ajello, M., et al. 2016, ApJS, 223, 26 [Google Scholar]

- Achterberg, A., & Blandford, R. D. 1986, MNRAS, 218, 551 [Google Scholar]

- Adams, S. M., Kochanek, C. S., Beacom, J. F., Vagins, M. R., & Stanek, K. Z. 2013, ApJ, 778, 164 [Google Scholar]

- Adriani, O., Barbarino, G. C., Bazilevskaya, G. A., et al. 2011, Science, 332, 69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adriani, O., Akaike, Y., Asano, K., et al. 2022, Phys. Rev. Lett., 129, 101102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Amato, E., & Blasi, P. 2005, MNRAS, 364, L76 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Amato, E., & Blasi, P. 2006, MNRAS, 371, 1251 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An, Q., Asfandiyarov, R., Azzarello, P., et al. 2019, Sci. Adv., 5, eaax3793 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Axford, W. I., Leer, E., & Skadron, G. 1977, Int. Cosm. Ray Conf., 11, 132 [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera, R., & Petruk, O. 2004, A&A, 419, 419 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bednarek, W., & Bartosik, M. 2003, A&A, 405, 689 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A. R. 1978, MNRAS, 182, 147 [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A. R. 2004, MNRAS, 353, 550 [Google Scholar]

- Bell, A. R., Schure, K. M., Reville, B., & Giacinti, G. 2013, MNRAS, 431, 415 [Google Scholar]

- Beloborodov, A. M. 2023, ApJ, 959, 34 [Google Scholar]

- Bertschinger, E. 1986, ApJ, 304, 154 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Binette, L., Dopita, M. A., & Tuohy, I. R. 1985, ApJ, 297, 476 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bisnovatyi-Kogan, G. S., & Silich, S. A. 1995, Rev. Mod. Phys., 67, 661 [Google Scholar]

- Bisschoff, D., Potgieter, M. S., & Aslam, O. P. M. 2019, ApJ, 878, 59 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blandford, R. D., & Ostriker, J. P. 1978, ApJ, 221, L29 [Google Scholar]

- Blasi, P. 2002, Astropart. Phys., 16, 429 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi, P. 2004, Astropart. Phys., 21, 45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi, P. 2013, A&ARv, 21, 70 [Google Scholar]

- Blasi, P., Gabici, S., & Brunetti, G. 2007, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A, 22, 681 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin, J. M., Wright, E. B., Borkowski, K. J., & Reynolds, S. P. 1998, ApJ, 500, 342 [Google Scholar]

- Bykov, A. M., Chevalier, R. A., Ellison, D. C., & Uvarov, Y. A. 2000, ApJ, 538, 203 [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z., Aharonian, F., An, Q., et al. 2024, ApJS, 271, 25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli, D. 2012, JCAP, 2012, 038 [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli, D., & Spitkovsky, A. 2014, ApJ, 783, 91 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli, D., Haggerty, C. C., & Blasi, P. 2020, ApJ, 905, 2 [Google Scholar]

- Carretero-Castrillo, M., Benaglia, P., Paredes, J. M., & Ribó, M. 2025, A&A, 694, A250 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Celli, S., Morlino, G., Gabici, S., & Aharonian, F. A. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 4317 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cherenkov Telescope Array Consortium, Acharya, B. S., Agudo, I., et al. 2019, Science with the Cherenkov Telescope Array [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, R. A. 1982, ApJ, 258, 790 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, R. A., & Fransson, C. 1994, ApJ, 420, 268 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, R. A., & Imamura, J. N. 1982, ApJ, 261, 543 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cioffi, D. F., McKee, C. F., & Bertschinger, E. 1988, ApJ, 334, 252 [Google Scholar]

- Cristofari, P., Blasi, P., & Amato, E. 2020, Astropart. Phys., 123, 102492 [Google Scholar]

- Cristofari, P., Blasi, P., & Caprioli, D. 2021, A&A, 650, A62 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cristofari, P., Blasi, P., & Caprioli, D. 2022, ApJ, 930, 28 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, A. C., Stone, E. C., Heikkila, B. C., et al. 2016, ApJ, 831, 18 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Diesing, R., & Caprioli, D. 2019, Phys. Rev. Lett., 123, 071101 [Google Scholar]

- Diesing, R., & Gupta, S. 2025, ApJ, 980, 167 [Google Scholar]

- Diesing, R., Guo, M., Kim, C.-G., Stone, J., & Caprioli, D. 2024, ApJ, 974, 201 [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T. 2011, Physics of the Interstellar and Intergalactic Medium (Princeton University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T., & McKee, C. F. 1993, ARA&A, 31, 373 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drake, R. P. 2005, Ap&SS, 298, 49 [Google Scholar]

- Fang, K., Metzger, B. D., Vurm, I., Aydi, E., & Chomiuk, L. 2020, ApJ, 904, 4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gabici, S., Evoli, C., Gaggero, D., et al. 2019, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, 28, 1930022 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gintrand, A., Sanz, J., Bouquet, S., & Paradela, J. 2020, Phys. Fluids, 32, 016105 [Google Scholar]

- Godard, B., des Forêts, G. P., & Bialy, S. 2024a, A&A, 688, A169 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Godard, B., Pineau des Forêts, G., La Porte, J., & Merlin-Weck, M. 2024b, A&A, 689, A25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. A. 2025, JApA, 46, 14 [Google Scholar]

- Guo, F., & Giacalone, J. 2013, ApJ, 773, 158 [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X., Sironi, L., & Narayan, R. 2014, ApJ, 797, 47 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- H.E.S.S. Collaboration (Abdalla, H. et al.) 2018a, A&A, 612, A1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- H.E.S.S. Collaboration (Abdalla, H., et al.) 2018b, A&A, 612, A3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- H.E.S.S. Collaboration (Aharonian, F., et al.) 2022, Science, 376, 77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Keilty, K. A., Liang, E. P., Ditmire, T., et al. 2000, ApJ, 538, 645 [Google Scholar]

- Krymskii, G. F. 1977, Akademiia Nauk SSSR Doklady, 234, 1306 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.-L., Metzger, B. D., Chomiuk, L., et al. 2017, Nat. Astron., 1, 697 [Google Scholar]

- Longair, M. S. 1994, High Energy Astrophysics. Volume 2. Stars, the Galaxy and the Interstellar Medium, 2 [Google Scholar]

- Malkov, M. A., & Drury, L. O. 2001, Rep. Progr. Phys., 64, 429 [Google Scholar]

- Marcowith, A., & Casse, F. 2010, A&A, 515, A90 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Marcowith, A., Dwarkadas, V. V., Renaud, M., Tatischeff, V., & Giacinti, G. 2018, MNRAS, 479, 4470 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Matsakos, T., Chièze, J. P., Stehlé, C., et al. 2013, A&A, 557, A69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, B. D., Finzell, T., Vurm, I., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 450, 2739 [Google Scholar]

- Mihalas, D., & Binney, J. 1981, Galactic Astronomy. Structure and Kinematics (San Francisco: Freeman) [Google Scholar]

- Morlino, G., & Caprioli, D. 2012, A&A, 538, A81 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Morlino, G., Blasi, P., Bandiera, R., Amato, E., & Caprioli, D. 2013, ApJ, 768, 148 [Google Scholar]

- O’C Drury, L., Duffy, P., & Kirk, J. G. 1996, A&A, 309, 1002 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, T., & Singh, C. B. 2021, MNRAS, 503, 586 [Google Scholar]

- Ostriker, J. P., & McKee, C. F. 1988, Rev. Mod. Phys., 60, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Padovani, M., Hennebelle, P., Marcowith, A., & Ferrière, K. 2015, A&A, 582, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Padovani, M., Marcowith, A., Hennebelle, P., & Ferrière, K. 2016, A&A, 590, A8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Park, J., Caprioli, D., & Spitkovsky, A. 2015, Phys. Rev. Lett., 114, 085003 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Petruk, O., & Kuzyo, T. 2024, A&A, 688, A108 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Phan, V. H. M., Cristofari, P., Peretti, E., Tatischeff, V., & Ciardi, A. 2025, ApJ, 990, 17 [Google Scholar]

- Piran, T. 2004, Rev. Mod. Phys., 76, 1143 [Google Scholar]

- Pitik, T., Tamborra, I., Lincetto, M., & Franckowiak, A. 2023, MNRAS, 524, 3366 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, M., Yan, H., & Lazarian, A. 2005, ApJ, 626, L101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ptuskin, V. S., & Zirakashvili, V. N. 2003, A&A, 403, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ptuskin, V. S., & Zirakashvili, V. N. 2005, A&A, 429, 755 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, J. C. 1979, ApJS, 39, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reighard, A. B., Drake, R. P., Dannenberg, K. K., et al. 2006, Phys. Plasmas, 13, 082901 [Google Scholar]

- Ressler, S. M., Katsuda, S., Reynolds, S. P., et al. 2014, ApJ, 790, 85 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S. P. 2008, ARA&A, 46, 89 [Google Scholar]

- Sakawa, Y., Ishihara, H., Ryazantsev, S. N., et al. 2024, Phys. Rev. Lett., 133, 195102 [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, K. C., Gnat, O., & Sternberg, A. 2021, MNRAS, 504, 583 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schure, K. M., & Bell, A. R. 2013, MNRAS, 435, 1174 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schure, K. M., Achterberg, A., Keppens, R., & Vink, J. 2010, MNRAS, 406, 2633 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Smartt, S. J. 2009, ARA&A, 47, 63 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, E., & Metzger, B. D. 2018, MNRAS, 479, 687 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland, R., & Blondin, J. M. 1995, ApJ, 449, 727 [Google Scholar]

- Strom, R. G. 1994, A&A, 288, L1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland, R. S., & Dopita, M. A. 2017, ApJS, 229, 34 [Google Scholar]

- Tammann, G. A., Loeffler, W., & Schroeder, A. 1994, ApJS, 92, 487 [Google Scholar]

- Tang, X., & Chevalier, R. A. 2017, MNRAS, 465, 3793 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, A., Williams, B. J., Petre, R., Ressler, S. M., & Reynolds, S. P. 2015, ApJ, 812, 101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Truelove, J. K., & McKee, C. F. 1999, ApJS, 120, 299 [Google Scholar]

- Valtaoja, E., & Terasranta, H. 1995, A&A, 297, L13 [Google Scholar]

- van Haarlem, M. P., Wise, M. W., Gunst, A. W., et al. 2013, A&A, 556, A2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Vink, J. 2012, A&ARv, 20, 49 [Google Scholar]

- Vishniac, E. T. 1994, ApJ, 428, 186 [Google Scholar]

- Vurm, I., & Metzger, B. D. 2018, ApJ, 852, 62 [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, R., McCray, R., Castor, J., Shapiro, P., & Moore, R. 1977, ApJ, 218, 377 [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm, A., Telezhinsky, I., Dwarkadas, V. V., & Pohl, M. 2020, A&A, 639, A124 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, L. B., III, Koval, A., Szabo, A., et al. 2017, J. Geophys. Res.: Space Phys., 122, 9115 [Google Scholar]

- Wittor, D., Vazza, F., & Brüggen, M. 2017, MNRAS, 464, 4448 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, W., Fazzini, A., Chen, S. N., et al. 2021, Nat. Phys., 17, 1177 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zirakashvili, V. N., & Ptuskin, V. S. 2008, AIP Conf. Ser., 1085, 336 [Google Scholar]

- Zirakashvili, V. N., & Ptuskin, V. S. 2022, MNRAS, 510, 2790 [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Velocity, density, and temperature of the fluid across the shock, for Mach numbers upstream |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Spectra of accelerated particles at the shocks for various Mach numbers. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Maximum momentum of accelerated particles at an SNR from a Type Ia (thick lines) and Type II (thin) progenitor. The dashed orange and black lines correspond to the beginning and end of the radiative phase. The solid red lines correspond to the pmax associated with a magnetic field amplification driven by the growth of nonresonant streaming instabilities (Bell) (Schure & Bell 2013), the dashed green lines to the radiative phase (Section 2.2), and the dotted blue line to the ion-neutral damping (Section 2.3). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Protons (left panel) and electrons (right panel) accelerated throughout the life of an SNR from a Type Ia SN. The thin orange, pink, and green lines correspond to the particles trapped inside the SNR, escaping the SNR, and reaccelerated from the Galactic CRs, respectively. The dashed lines correspond to the FE and ST phases, while the solid lines additionally take into account the radiative (RAD) phase. The thick dashed blue line corresponds to the total contribution of the FE and ST phases. The thick solid lime line corresponds to the total contribution of the FE, ST, and RAD phases. The bottom panels show the slope of the spectrum sum of all components, for the ST and FE phase (dashed blue), and including the radiative phase (solid lime). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. As in Fig. 4, but for a SNR from a Type II SN, ESN = 1051 erg, Ṁ = 10−5 M⊙/yr, and Mej = 5 M⊙. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Proton (top), electron (middle), and proton–electron spectral index difference, Δq = qelectrons − qprotons (bottom), distributions. Colored lines (from thin to thick) show the effect of increasing the SNR lifetime from 20 kyr to 300 kyr, assuming a Type Ia SN progenitor. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Electron–proton spectral index difference, Δq = qelectrons − qprotons, for Type Ia (blue lines) and Type II (orange lines). The thick lines correspond to the results considering the FE and ST phases, the thin solid lines additionally include the radiative phase considering Bell prescription for the magnetic field, and the dashed lines considering the resonant modified prescription for the magnetic field. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Maximum momentum of accelerated particles at a young SNR shock expanding in the dense wind of the progenitor star, as a function of density and shock velocity. The green circles, crosses, and triangles show the typical values reached 1 day, 1 month, and 1 year after the SN explosion, respectively. The size of the symbols increases with Ṁ from 10−5 to 1 M⊙/yr. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$$ \begin{aligned} \frac{T_2}{T_1}&= \frac{[(\gamma -1)\mathcal{M}_1^2+2][2\gamma \mathcal{M}_1^2- (\gamma -1)]}{(\gamma + 1)^2 \mathcal{M}_1^2},\end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa55053-25/aa55053-25-eq8.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} f_0(p) = \frac{3 r_{\rm sub}}{r_{\rm sub} - 1}\frac{\eta n_1}{4 \pi p_{\rm inj}^3} \exp \left[ \int _{p_{\rm inj}}^p \frac{3 R_{\rm tot}(p)}{R_{\rm tot}(p)-1} \frac{\text{ d}p\prime }{p\prime }\right] ,\end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa55053-25/aa55053-25-eq19.gif)