| Issue |

A&A

Volume 705, January 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A177 | |

| Number of page(s) | 20 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556491 | |

| Published online | 23 January 2026 | |

Variance of dust temperature and spectral index in Planck polarization data using spin-moment expansion

1

Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS, Univ. Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay,

Bât. 121,

91405

Orsay cedex,

France

2

Laboratoire Univers et Particules de Montpellier, Université de Montpellier, CNRS/IN2P2,

CC 72, Place Eugène Bataillon,

34095

Montpellier Cedex 5,

France

3

International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA),

Via Bonomea 265,

34136

Trieste,

Italy

4

Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN), Sezione di Trieste,

via Valerio 2,

34127

Trieste,

Italy

5

Institute for Fundamental Physics of the Universe (IFPU),

Via Beirut, 2,

34151

Grignano, Trieste,

Italy

6

IRAP, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, CNES, UPS,

Toulouse,

France

7

Laboratoire de Physique de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure, ENS, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Université de Paris,

75005

Paris,

France

8

Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, Grenoble INP, LPSC-IN2P3,

53, avenue des Martyrs,

38000

Grenoble,

France

9

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Cagliari,

Via della Scienza 5,

09047

Selargius,

Italy

10

Laboratoire d’Océanographie Physique et Spatiale (LOPS), Univ. Brest, CNRS, Ifremer, IRD,

29200

Brest,

France

11

INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri,

Largo E. Fermi 5,

50125

Firenze,

Italy

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

18

July

2025

Accepted:

19

October

2025

Thermal dust is the major polarized foreground hindering the detection of primordial cosmic microwave background (CMB) B-modes. Its signal exhibits complex behavior in frequency space, arising from the combined variation in our Galaxy of the orientation of magnetic fields and the spectral properties of dust grains aligned with magnetic field lines. In this work, we present a new framework for analyzing the thermal dust signal using polarized microwave data. We introduce residual maps, represented as complex quantities, which capture deviations of the local polarized spectral energy distribution (SED) from the mean complex SED averaged over the sky mask. We present simple predictions that relate the values of the statistical correlation and covariances between the residual maps to the physical properties of the emitting aligned grains. Testing these predictions provides valuable information about the nature of the dust signal. We evaluated our predictions using Planck data over a 97% mask excluding the inner Galactic plane. Despite its simplicity, our model captures a significant part of the statistical properties of the data. For the SRoll2 version of the data, the spectral dependence of the covariances between residual maps is compatible with a dust model that includes only temperature variations rather than spectral index variations. In contrast, for the PR4 Planck official release, it is incompatible with both models. Our methodology can be used to analyze future high-precision polarization data and to build more accurate dust models for use by the CMB community.

Key words: dust, extinction / ISM: magnetic fields / cosmic background radiation

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Observations from the visible to the submillimeter wavelengths (submm) provide extensive evidence on the variations in dust composition and optical properties through the Galaxy. The importance of dust processing in the interstellar medium (ISM) is demonstrated first by the large variations seen in the extinction curve and the depletions of refractory elements (Draine 2003; Jenkins 2009; Schlafly et al. 2016). Additional evidence comes from variations in the spectral energy distribution (SED) and the far-infrared and submm dust opacity of molecular clouds and the diffuse ISM, observed by the Herschel (Ysard et al. 2013) and Planck space missions (Planck Collaboration 2013 XI 2014; Planck Collaboration Int. XVII 2014). These variations of the dust SED include, but are not fully explained by, the dependence of dust temperature on the local intensity of the interstellar radiation field (Fanciullo et al. 2015).

The observational signatures of dust evolution in the dust SED in polarization are harder to identify due to the reduced amplitude of the signal compared to the total intensity (Pelgrims et al. 2021; Ritacco et al. 2023). The interpretation of polarization data considers the combined variations in the structure of the Galactic magnetic field and the dust SED, both in the plane of the sky and along the line of sight in the three-dimensional Galaxy (Tassis & Pavlidou 2015; Planck Collaboration Int. L 2017; McBride et al. 2023; Vacher et al. 2025). This is the specific problem that our work addresses. We present a modeling framework that incorporates variations in dust properties within a turbulent magnetic field, designed to quantify the variance in dust spectral properties from submm polarization data.

In submm polarization maps, the diffuse polarized emission from dust grains that are locally aligned with magnetic-field orientation is summed over the light cone, a small region of the sky observed by the instrumental beam containing both plane-of-the-sky and line-of-sight variations. Variations in the magnetic field orientation within the light cone lead to depolarization (Planck Collaboration Int. XLIV 2016; Clark & Hensley 2019), and their combined variations with changes in dust properties lead to the frequency-dependence of the polarization angle (Tassis & Pavlidou 2015; Planck Collaboration Int. L 2017; Vacher et al. 2023b). For studies of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) polarization, the variation over the sky of dust spectral parameters, and the non-linear distortion they induce in the SEDs, together with their impact on the frequency dependence of polarization angles, makes the separation of the dust and CMB signals a difficult task, especially given the high sensitivity of next-generation experiments (Remazeilles et al. 2016; LiteBIRD Collaboration 2022; Wolz et al. 2024). The modeling of spatial variations in the dust polarization SED is therefore of prime importance for the search for primordial B-modes from inflation and for the putative EB correlation from cosmic birefringence (Diego-Palazuelos et al. 2022, 2023; Vacher et al. 2023a; Jost et al. 2023; Sullivan et al. 2025).

Planck observations show that the mean SED of dust polarized emission in the high-latitude diffuse ISM is remarkably well fitted by a modified black body (MBB) law from 353 GHz to microwave frequencies (Planck Collaboration 2018 XI 2020). This observational result leads us to model spatial variations of the dust polarization SED using the moment expansion method around an MBB, as introduced by Chluba et al. (2017). Previous studies carried out in preparation for future experiments, such as the Simons Observatory and LiteBIRD, show that when spatial variations are present in the foreground SED, the moment-expansion formalism provides a powerful tool to recover the CMB signal without bias, and with minimal parameter addition (Azzoni et al. 2021; Remazeilles et al. 2021; Désert 2022; Vacher et al. 2022; Sponseller & Kogut 2022; Azzoni et al. 2023; Wolz et al. 2024; Carones & Remazeilles 2024). The moment expansion formalism can be extended to polarized dust emission using complex spin-2 fields, referred to as"spin-moment" coefficients (Vacher et al. 2023b,a). In this work, we use this formalism to introduce a modeling framework that, within some simplifying assumptions, accounts for the combined variations of dust properties and magnetic field structure. Applying it to Planck data, we demonstrate the relevance of this framework for analyzing dust polarization microwave observations for foreground modeling and component separation.

Our paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce the dust model and data modeling framework based on complex residual maps. We enumerate the predictions of our model in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, building on the work of Ritacco et al. (2023), we test the validity of our simplifying assumptions in relation to sky observations by analyzing the Planck SRoll2 maps (Delouis et al. 2019). In Sect. 5, we interpret our results in terms of fluctuations in dust spectral properties and compare them with those obtained using the PR4 version of the Planck data (Planck Collaboration Int. LVII 2020). In Section 6, we discuss our results, which we then summarize in Sect. 7.

2 Model definition

Our dust model and methodology, based on complex numbers, are designed to quantify the variance in the emission properties of grains aligned with magnetic field lines1 which emit polarized radiation in the far-infrared and submm. In Sect. 2.1, we set out the assumptions of our dust signal model and in Sect. 2.2 we show how these hypotheses enable accurate modeling of the polarized signal using complex numbers and the moment expansion. In Sect. 2.5, we define the so-called polarization residual maps, from which we derive various covariances in Sect. 2.6. These covariances are then used to build the predictions of our model in Sect. 3.

2.1 Dust model hypothesis

Our dust model relies on simplifying hypotheses of two kinds: astrophysical (HA) and methodological (HM), listed below.

HA1: the local dust polarized SED emitted at any given position in the Galaxy is a single MBB with local temperature T and local spectral index β.

HA2: the variations of the dust polarization spectral parameters T or β, from one point of the Galaxy to another, are not correlated with variations in the orientation of the magnetic field.

HM3: only two extreme cases are explored: the fluctuations of dust properties are either pure β fluctuations over the whole sky or pure T fluctuations.

HA4: the grain alignment efficiency is uniform over the sky; only the structure of the magnetic field controls the dust polarization fraction. This hypothesis was shown by Planck Collaboration 2018 XII (2020) to be justified at the scale of a degree or more.

HM5: following Planck Collaboration Int. XLVIII (2016), we modeled the structure of magnetic fields as a turbulent field close to equipartition between its ordered and random components.

HM6: our data analysis methodology accounts for contamination of the dust polarization signal in Planck data by CMB, noise, and systematics, but it neglects possible contribution from polarized CO emission or leakage of CO emission in the 217 and 100 GHz channels, as well as the presence of residual synchrotron emission after template removal.

While these hypotheses are quite restrictive, our model is able to generate a frequency-dependence of polarization angles. The simplicity of the model and the clarity of its building hypotheses allow one to infer its predictions unambiguously and to identify its limits precisely. To assist the reader with the numerous notations, Table A.1 summarizes all the quantities used in our model.

2.2 Spin-moment expansion of the complex polarized SED

Following the work of Ritacco et al. (2023), we developed an analytical framework to model the observed variations with the frequency of polarization intensity and angle. For this purpose, we did not use the E and B decomposition (Zaldarriaga & Seljak 1997). Instead, we quantified the total variance of the Stokes parameters. For a given frequency ν, we define the dust complex polarized SED Pν from the Stokes parameters Qν and Uν as follows (complex quantities are written in bold font):

where ![$\[\dot{\mathbb{i}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq2.png) is the imaginary unit

is the imaginary unit ![$\[\left(\dot{\mathbb{i}}^{2}=-1\right), P_{\nu}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq3.png) is the polarized intensity (

is the polarized intensity (![$\[P_{\nu}=\sqrt{Q_{\nu}^{2}+U_{\nu}^{2}}=\sqrt{\mathbf{P}_{\nu} \mathbf{P}_{\nu}^{\star}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq4.png) , with ⋆ denoting complex conjugation), and ψν = 0.5 arctan(Uν, Qν) is the frequency-dependent polarization angle.

, with ⋆ denoting complex conjugation), and ψν = 0.5 arctan(Uν, Qν) is the frequency-dependent polarization angle.

Following Vacher et al. (2023b), we note that the use of complex spin-moments is well suited to studying fluctuations in the dust complex polarized SED. The SED Pν observed over a region of the sky is given by the integral over all the local elementary SEDs dPν present within the observed light cone ℒ:

Variations in phases in this integral can partially or fully cancel the polarization signal, a phenomenon known as depolarization (Planck Collaboration Int. XIX 2015). The so-called light cone, ℒ, is a region of the sky over which all local signals dPν – contained both in the plane of the sky and along the line of sight – are averaged. Depending on the context of the analysis, ℒ can refer to a map pixel, the instrumental beam, or even the entire sky, possibly masked. In the present work, we considered ℒ to be the instrumental beam surrounding each pixel of the sky.

We used an MBB model of dust emission (hypothesis HA1, Sect. 2.1) characterized by a local spectral index β and a local temperature T to express the local dust emissivity εν(T, β) at frequency ν,

where Bν(T) is Planck’s law at frequency ν and temperature T, and ν0 is a reference frequency. Assuming that the local complex polarized intensity, dPν0, at frequency ν0 is well-defined in amplitude and phase everywhere in the light cone, the frequency-dependence of the local complex polarized SED, dPν, is

Because the emissivity εν is a real quantity, dPν has the same polarization angle at all frequencies.

To estimate the impact of fluctuations in the spectral parameter s ∈ {T, β} on the observed complex polarized intensity Pν (under our hypothesis HM3, which assumes that either T or β fluctuates over the whole sky but not both), we performed a Taylor expansion of the power-law term and the blackbody in dPν in Eq. (4) around an arbitrary pivot spectral index ![$\[\overline{\beta}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq8.png) and pivot temperature

and pivot temperature ![$\[\overline{T}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq9.png) . We find that the frequency dependence of the complex polarized intensity can be expressed as (Vacher et al. 2023b)

. We find that the frequency dependence of the complex polarized intensity can be expressed as (Vacher et al. 2023b)

where

is the pivot SED, the function ![$\[a_{\nu, n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq12.png) of ν denotes the nth order derivative of the dust emissivity with respect to the spectral parameter s,

of ν denotes the nth order derivative of the dust emissivity with respect to the spectral parameter s,

and ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq14.png) is the nth order spin-moment of s (Vacher et al. 2023b), given2 by

is the nth order spin-moment of s (Vacher et al. 2023b), given2 by

The spin-moments ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq19.png) encode the departure of the spectral dependence of Pν from the pivot SED

encode the departure of the spectral dependence of Pν from the pivot SED ![$\[\overline{\varepsilon}_{\nu}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq20.png) . The pivot spectral parameters

. The pivot spectral parameters ![$\[\overline{\beta}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq21.png) and

and ![$\[\overline{T}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq22.png) are constant over ℒ. For simplicity, we further considered a single pair of pivots for all light cones and hence the whole sky. In this analysis, we used

are constant over ℒ. For simplicity, we further considered a single pair of pivots for all light cones and hence the whole sky. In this analysis, we used ![$\[\overline{T} \equiv 20 \mathrm{~K}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq23.png) . The specific value for

. The specific value for ![$\[\overline{\beta}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq24.png) is not critical, as it does not appear in the data analysis.

is not critical, as it does not appear in the data analysis.

The frequency dependence of ![$\[a_{\nu, n}^{T}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq25.png) and

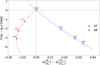

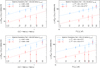

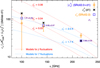

and ![$\[a_{\nu, n}^{\beta}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq26.png) is presented in Fig. 1 for n = 1, 2, and 3. Their analytical expression for n = 1 is as follows:

is presented in Fig. 1 for n = 1, 2, and 3. Their analytical expression for n = 1 is as follows:

The values of the ![$\[a_{\nu, n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq29.png) functions – hereafter referred to as the spectral gradients – are listed explicitly up to n = 5 for both β and T in Chluba et al. (2017).

functions – hereafter referred to as the spectral gradients – are listed explicitly up to n = 5 for both β and T in Chluba et al. (2017).

The polarization-weighted moment ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq30.png) is distinct from the intensity-weighted moments

is distinct from the intensity-weighted moments ![$\[\omega_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq31.png) (Chluba et al. 2017):

(Chluba et al. 2017):

with s ∈ {T, β} as before. Like ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}, \omega_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq33.png) characterizes the statistical properties of the spectral parameters s of aligned grains. However,

characterizes the statistical properties of the spectral parameters s of aligned grains. However, ![$\[\omega_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq34.png) is independent of the structure of the magnetic field, whereas

is independent of the structure of the magnetic field, whereas ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq35.png) is not. The difference between these two moments,

is not. The difference between these two moments,

is a complex quantity of interest. In Appendix B, we demonstrate that, under our hypothesis HA2, which assumes no correlation between the fluctuations of dust spectral properties and variations in the magnetic field direction, ![$\[\Delta_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq37.png) has a statistically zero mean:

has a statistically zero mean: ![$\[\left\langle\boldsymbol{\Delta}_{n}^{s}\right\rangle=0\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq38.png) .

.

|

Fig. 1 Values of |

2.3 Spectral rotation of polarization angles

To gain further insight into how the spin-moments, ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq39.png) , are related to the spectral dependence of Pν, we first consider the specific case of small distortions of the polarized SED around the pivot SED (

, are related to the spectral dependence of Pν, we first consider the specific case of small distortions of the polarized SED around the pivot SED (![$\[\left|{\sum}_{n=1}^{\infty} a_{\nu, n}^{s} \boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\right| \ll 1\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq40.png) ). Taking the logarithm of Eq. (5) and using the approximation ln(1 + x) ~ x for x ≪ 1, we obtain

). Taking the logarithm of Eq. (5) and using the approximation ln(1 + x) ~ x for x ≪ 1, we obtain

from which we take the real and imaginary parts and, using Eq. (1),

Equation (15) describes the spectral rotation of the polarization angle with frequency, caused by fluctuations of the dust spectral parameters within the light cone. Its frequency dependence is governed by the ![$\[a_{\nu, n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq44.png) parameters and its amplitude depends on the imaginary parts

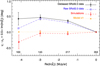

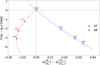

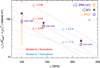

parameters and its amplitude depends on the imaginary parts ![$\[\operatorname{Im \boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq45.png) of the spin-moments. Figure 2 provides a numerical illustration of such a rotation in the log-complex plane for the sum of seven MBBs with Gaussian-distributed spectral parameters in a turbulent magnetic-field model inspired by Planck Collaboration Int. XLVIII (2016) (see also our description in Appendix C). We consider the two cases of our hypothesis HM3: pure fluctuations in T or pure fluctuations in β. Under the assumption of small variations in T or β, the complex SED plotted in the log-complex plane (ln (Pν/ϵν), 2ψν) is close to a straight line for T fluctuations and can be non-linear for β fluctuations when the magnetic field direction is close to the line of sight (as shown in Fig. 2 for illustration). This shows that, in a given light cone, the rotation of the polarization angle with frequency is strongly correlated with the distortion of the polarized intensity relative to the pivot SED.

of the spin-moments. Figure 2 provides a numerical illustration of such a rotation in the log-complex plane for the sum of seven MBBs with Gaussian-distributed spectral parameters in a turbulent magnetic-field model inspired by Planck Collaboration Int. XLVIII (2016) (see also our description in Appendix C). We consider the two cases of our hypothesis HM3: pure fluctuations in T or pure fluctuations in β. Under the assumption of small variations in T or β, the complex SED plotted in the log-complex plane (ln (Pν/ϵν), 2ψν) is close to a straight line for T fluctuations and can be non-linear for β fluctuations when the magnetic field direction is close to the line of sight (as shown in Fig. 2 for illustration). This shows that, in a given light cone, the rotation of the polarization angle with frequency is strongly correlated with the distortion of the polarized intensity relative to the pivot SED.

2.4 Mean complex normalized SED

From here on, we simplify our notation for channel i of frequency νi and use Pi to denote the map of complex polarized intensity, ![$\[\overline{\varepsilon}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq46.png) for the pivot emissivity (constant over the sky), and

for the pivot emissivity (constant over the sky), and ![$\[a_{i, n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq47.png) for the spectral gradient.

for the spectral gradient.

Following Ritacco et al. (2023), we cross-correlated the polarization maps to determine the mean complex SED ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq48.png) of dust polarization, averaged over the sky and normalized to our reference channel, given by

of dust polarization, averaged over the sky and normalized to our reference channel, given by

where ![$\[\overline{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq50.png) is the mean value of

is the mean value of ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq51.png) over the sky, weighted by

over the sky, weighted by ![$\[P_{0}^{2}=\mathbf{P}_{0} \mathbf{P}_{0}^{\star}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq52.png) as

as

|

Fig. 2 Rotation of the SED in the complex plane for a sum of seven MBB SEDs with distinct spectral indices drawn from a Gaussian distribution with mean 1.5 and standard deviation 0.1 (red), or with temperatures drawn from a Gaussian distribution with mean 20 K and standard deviation 5 K (blue). The 3D orientation of the magnetic field is a random realization of the turbulent magnetic field inspired by Planck Collaboration Int. XLVIII (2016). The dashed lines indicate frequencies from 40 to 400 GHz, and the four colored points represent the Planck HFI bands. |

2.5 Residual maps for complex polarization

In this section, we use the pivot SED to construct complex residual maps at all frequencies and relate them to the ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq54.png) moments. We define the residual map Ri for the complex polarization Pi:

moments. We define the residual map Ri for the complex polarization Pi:

This complex map characterizes the residuals at frequency νi after removal of the components correlated with the polarization map at the reference frequency ν0, and subsequently scaled to the reference frequency ν0. Here, Ri quantifies the complexity of the dust signal by measuring its deviations from the mean complex SED ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq56.png) .

.

Using Eqs. (5) and (16), we obtain

By choosing the pivot SED close to the mean SED, we ensure that ![$\[\left|{\sum}_{n=1}^{\infty} a_{i, n}^{s} \overline{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{n}^{s}\right|=\left|\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i} \frac{\overline{\varepsilon}_{0}}{\overline{\varepsilon}_{i}}-1\right| \ll 1\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq58.png) (this hypothesis is verified in the data analysis in Sect. 4), so that, by expanding the previous equation to first order, we obtain

(this hypothesis is verified in the data analysis in Sect. 4), so that, by expanding the previous equation to first order, we obtain

We decompose Ri into its real and imaginary components:

For ![$\[R_{i}^{\psi}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq62.png) to be non-zero in a given light cone ℒ, both the magnetic field and the spectral parameters should vary inside ℒ, whereas a variation in spectral parameters alone suffices for

to be non-zero in a given light cone ℒ, both the magnetic field and the spectral parameters should vary inside ℒ, whereas a variation in spectral parameters alone suffices for ![$\[R_{i}^{P}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq63.png) to be non-zero. We use the labels P and ψ for these map residuals because, as demonstrated in Sect. 2.3, in the limit of small fluctuations, the real and imaginary parts of the complex polarized SED correspond directly to the polarized intensity P and polarization angle ψ.

to be non-zero. We use the labels P and ψ for these map residuals because, as demonstrated in Sect. 2.3, in the limit of small fluctuations, the real and imaginary parts of the complex polarized SED correspond directly to the polarized intensity P and polarization angle ψ.

Similarly, we define the map residual ![$\[R_{i}^{\varepsilon}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq64.png) of the dust polarized emissivity that corresponds to the moments

of the dust polarized emissivity that corresponds to the moments ![$\[\omega_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq65.png) (Eq. (11)) as

(Eq. (11)) as

Here, ![$\[\overline{\omega}_{n}^{s} \equiv\left\langle P_{0}^{2} \omega_{n}^{s}\right\rangle /\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq67.png) denotes the sky-averaged value of

denotes the sky-averaged value of ![$\[\omega_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq68.png) . The map residual

. The map residual ![$\[R_{i}^{\varepsilon}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq69.png) represents what would be observed if the polarization angles were constant across each light cone. It maps the variations of the spectral properties of aligned grains, independently of the magnetic field structure, while

represents what would be observed if the polarization angles were constant across each light cone. It maps the variations of the spectral properties of aligned grains, independently of the magnetic field structure, while ![$\[R_{i}^{P}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq70.png) mixes both.

mixes both.

2.6 Covariance matrices of residual maps

Consider a complex map X (resp. Y) with sky-averaged values ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{X}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq71.png) and

and ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{Y}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq72.png) , defined as

, defined as

We use the notation Cov(X, Y) for the covariance of X and Y weighted by ![$\[P_{0}^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq74.png) and computed over the sky:

and computed over the sky:

where the quantity inside the brackets must be averaged over the partial sky after application of the mask.

For all frequency pairs (i, j), we define covariances for the polarization map residuals RP and Rψ:

While the residual maps R represent values for each light cone of the map, the covariances c are averaged quantities that sum up the statistics of all light cones that make up the masked sky. Because we are working at the map scale and not in Fourier space, this mask does not need to be continuous.

We also define the mixed-covariance of Rψ with RP:

and its companion ![$\[c_{i j}^{P \psi} \equiv c_{j i}^{\psi P}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq79.png) .

.

Finally, we define the covariance matrix cε, which characterizes the fluctuations of the emissivity of aligned grains as

This covariance is the only one not contaminated by variations in the magnetic field structure and so can be directly compared safely to dust models or observations in total intensity.

All these quantities are N × N matrices of real numbers, with N the number of channels. In contrast, the covariance cP of the complex map residual R,

is an N × N matrix of complex numbers, related to other real matrices through

We therefore have the trivial equalities, already expected from the definition of RP and Rψ (Eq. (21) and (22)):

By symmetry, ![$\[\operatorname{Im} \mathbf{c}_{i j}^{\mathbf{P}}=0\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq86.png) if i = j. For i ≠ j, we have

if i = j. For i ≠ j, we have

3 Predictions of our model

Here and throughout this work, predictions of our model are highlighted by a boxed frame.

3.1 Expected level of correlation between residual maps

Our dust model assumes that only a single spectral parameter, β or T, fluctuates in the light cone, but not both simultaneously (hypothesis HM3, Sect. 2.1). Fluctuations in T or β propagate into the residual maps. We next examine how well the residual maps correlate across frequencies.

Limiting the moment expansion of Eq. (20) to first order gives ![$\[\mathbf{R}_{i} \simeq a_{i, 1}^{s} P_{0}\left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{\mathbf{1}}^{\boldsymbol{s}}-\overline{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{1}^{s}\right)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq88.png) and

and ![$\[\mathbf{R}_{j} \simeq a_{j, 1}^{s} P_{0}\left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{\mathbf{1}}^{\boldsymbol{s}}-\overline{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{1}^{s}\right)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq89.png) . Residuals maps become simply proportional to each other. The correlation of Ri with Rj is perfect. This conclusion also holds for RP and for Rψ. Introducing higher-order n weakens this correlation by adding the common signals

. Residuals maps become simply proportional to each other. The correlation of Ri with Rj is perfect. This conclusion also holds for RP and for Rψ. Introducing higher-order n weakens this correlation by adding the common signals ![$\[\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq90.png) in channels i and j, but are weighted with frequency-dependent coefficients ai,n and aj,n, which differ from ai,1 and aj,1. From the values of ai,n (also displayed in Fig. 1), we computed the Pearson correlation coefficients ρ(ai,n, ai,m) across frequencies νi between the spectral parameters taken at two distinct orders n and m. We find

in channels i and j, but are weighted with frequency-dependent coefficients ai,n and aj,n, which differ from ai,1 and aj,1. From the values of ai,n (also displayed in Fig. 1), we computed the Pearson correlation coefficients ρ(ai,n, ai,m) across frequencies νi between the spectral parameters taken at two distinct orders n and m. We find ![$\[\rho\left(a_{i, 1}^{\beta}, a_{i, 2}^{\beta}\right)=-0.958\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq91.png) and

and ![$\[\rho\left(a_{i, 1}^{T}, a_{i, 2}^{T}\right)=-0.999\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq92.png) between orders n = 1 and m= 2, and

between orders n = 1 and m= 2, and ![$\[\rho\left(a_{i, 1}^{\beta}, a_{i, 3}^{\beta}\right)=0.905\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq93.png) and

and ![$\[\rho\left(a_{i, 1}^{T}, a_{i, 3}^{T}\right)=0.998\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq94.png) between orders n = 1 and m = 3. Despite changes in amplitude or sign from one order to another, the spectral gradients ai,n remain well correlated across the first, second, and third orders. This correlation is particularly strong for temperature fluctuations. Considering that the first order, which produces a perfect frequency-correlation, dominates the signal, we expect the sum

between orders n = 1 and m = 3. Despite changes in amplitude or sign from one order to another, the spectral gradients ai,n remain well correlated across the first, second, and third orders. This correlation is particularly strong for temperature fluctuations. Considering that the first order, which produces a perfect frequency-correlation, dominates the signal, we expect the sum ![$\[{\sum}_{n=1}^{\infty} a_{i, n}^{s}\left(\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}-\overline{\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{n}^{s}\right)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq95.png) to remain very well correlated through frequencies νi. Within the framework of our hypothesis HM3, our model, even including orders higher than one in the moment expansion, predicts a perfect correlation of residual maps across frequencies if only the dust temperature varies, and a strong but not perfect correlation if only the dust spectral index varies. We therefore obtain the first prediction P1 of our model:

to remain very well correlated through frequencies νi. Within the framework of our hypothesis HM3, our model, even including orders higher than one in the moment expansion, predicts a perfect correlation of residual maps across frequencies if only the dust temperature varies, and a strong but not perfect correlation if only the dust spectral index varies. We therefore obtain the first prediction P1 of our model:

A word of caution is necessary. We are stating that the residuals maps at different frequencies are correlated with each other, not the maps of the dust signal themselves. As such, dust complexity creates frequency decorrelation in the sense of Planck Collaboration Int. XXX (2016), meaning that the maps at different frequencies are no longer proportional. However, the complex distortions remain strongly correlated. This correlation can be understood geometrically as resulting from the rigid rotation of the complex polarized intensity in the complex plane (see Sect. 2.3 and Fig. 2), which arises from beam and line-of-sight integration effects.

3.2 Properties of covariance matrices of residual maps

We now examine the properties of the covariances of residual maps across frequencies to provide clear predictions that can readily be compared with Planck polarization data.

Using our assumption of no correlation between the magnetic field structure and the fluctuations of dust properties (hypothesis HA2), Eq. (25) yields ![$\[\operatorname{Cov}\left(\omega_{n}^{s}, \omega_{m}^{s}\right) \propto\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq97.png) . From Eq. (29) we therefore obtain the following scaling relation:

. From Eq. (29) we therefore obtain the following scaling relation:

This prediction (P2) is natural: the variance of dust polarized emissivity scales with the square of the mean polarized intensity.

To explore the properties of the variance of polarization angles cψ and intensity cP, we used the moment difference ![$\[\Delta_{n}^{s}=\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}_{n}^{s}-\omega_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq99.png) (Eq. (12)). We defined its sky-averaged value as

(Eq. (12)). We defined its sky-averaged value as ![$\[\overline{\boldsymbol{\Delta}_{n}^{s}} \equiv\left\langle P_{0}^{2} \boldsymbol{\Delta}_{n}^{s}\right\rangle /\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq100.png) . As

. As ![$\[\boldsymbol{\Delta}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq101.png) is statistically zero-mean (Sect. 2.2 and Appendix C), so is

is statistically zero-mean (Sect. 2.2 and Appendix C), so is ![$\[\boldsymbol{\Delta}_{n}^{s}-\overline{\boldsymbol{\Delta}_{n}^{s}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq102.png) so that Eqs. (26) and (27) become

so that Eqs. (26) and (27) become

Covariances of ![$\[\operatorname{Re \Delta}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq105.png) and

and ![$\[\operatorname{Im \Delta}_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq106.png) involve the statistical properties of

involve the statistical properties of ![$\[\Delta_{n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq107.png) that combine the fluctuations of the magnetic field and the optical properties of aligned grains within the light cone. In Appendix C, we present a toy model for a turbulent magnetic field close to equipartition, which successfully explains various statistical properties of dust polarization (Planck Collaboration 2018 XII 2020), and demonstrate that

that combine the fluctuations of the magnetic field and the optical properties of aligned grains within the light cone. In Appendix C, we present a toy model for a turbulent magnetic field close to equipartition, which successfully explains various statistical properties of dust polarization (Planck Collaboration 2018 XII 2020), and demonstrate that

where p0 = P0/I0 is the polarization fraction at the reference frequency with I0 the total intensity, and ![$\[\overline{\eta} \simeq 0.7 \pm 0.2\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq109.png) is a statistical parameter3 characterizing our turbulent magnetic field model. This property is the spectral analog of what is shown in Planck Collaboration 2018 XII (2020) for the spatial variations of polarization angles: dispersion in polarization angles anti-correlate with p0.

is a statistical parameter3 characterizing our turbulent magnetic field model. This property is the spectral analog of what is shown in Planck Collaboration 2018 XII (2020) for the spatial variations of polarization angles: dispersion in polarization angles anti-correlate with p0.

In calculating the covariances ![$\[\operatorname{Cov}\left(\operatorname{Im \Delta}_{n}^{s}, \operatorname{Im \Delta}_{m}^{s}\right)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq110.png) through Eq. (25), the scaling of

through Eq. (25), the scaling of ![$\[P_{0}^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq111.png) with

with ![$\[p_{0}^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq112.png) exactly cancels the dependence of

exactly cancels the dependence of ![$\[\left\langle\operatorname{Im \boldsymbol{\Delta}}_{n}^{s} \times \operatorname{Im \boldsymbol{\Delta}}_{m}^{s}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq113.png) with

with ![$\[1 / p_{0}^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq114.png) , yielding

, yielding ![$\[\operatorname{Cov}\left(\operatorname{Im \boldsymbol{\Delta}}_{n}^{s}, \operatorname{Im \boldsymbol{\Delta}}_{m}^{s}\right) \propto\left\langle I_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq115.png) and therefore

and therefore

Unlike cε, the variance cψ of the polarization angle residuals is predicted, unexpectedly, to scale with the mean square of the total intensity in the mask, with no dependence on the mean polarization fraction.

In the first term of the right-hand side of Eq. (36), we recognize, from Eq. (29), the variance of dust emissivity ![$\[c_{i j}^{\varepsilon}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq117.png) . The second term is, on average and according to Eqs. (37) and (38), proportional to

. The second term is, on average and according to Eqs. (37) and (38), proportional to ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq118.png) , leading to the statistical relationship:

, leading to the statistical relationship:

The variance in polarized intensity cP not only contains the variance cε of the dust polarization emissivity from one region of the sky to another, but also includes an additional variance due to distortions of the SED within the light cone, which can be estimated from the variance of the polarization angle residuals. Prediction P4 implies that cP, unlike cε, does not converge toward zero when the polarization fraction p0 tends towards zero. It also suggests a recipe for estimating the unknown variance cε of the dust polarized emissivity:

Since cε ≥ 0, this implies an upper limit for the ratio cψ/cP (prediction P5):

We use this last property to test whether our hypothesis HM6, which states that the signal is dominated by dust, holds, aside from contamination by CMB E-modes, noise, and systematics that we attempt to remove using simulations.

We conclude by analyzing the consequences for the covariances of the quasi-perfect correlation between the residual maps predicted in our model. Eqs. (26) and (27) show that the frequency dependence of any covariance cij is encoded in the parameters ai,n and aj,n. These parameters are common to all covariances and remain well-correlated across frequencies, as shown in Sect. 3.1. This implies that the ratio between two distinct covariances sharing the same frequency pair is independent of the particular pair (i, j) of channels considered (prediction P6):

We conclude with our final prediction, a null test resulting from the strong correlation of the spectral gradients across frequencies. The matrix Im cP (Eq. (35)) involves the cross-product ai,n aj,m − ai,m aj,n, which is a small factor due to the strong correlation of the ai,n parameters across frequencies. Hence, within the uncertainties, we expect (prediction P7)

In the following section, we compare our predictions with Planck polarization data.

4 Model validation using Planck polarization data

We applied our dust polarized emission model to analyze Planck data. We extend the power-spectrum analysis presented by Ritacco et al. (2023) to our model framework by measuring the total variance of the residual maps at the map level. The SRoll2 version of the Planck data is introduced in Sect. 4.1, and its associated simulations, used to debias our estimations, are described in Sect. 4.2. In the subsequent sections, we present the mean complex polarized SED in Sect. 4.3 and test our model predictions in Sect. 4.4.

4.1 Presentation of Planck maps

Ritacco et al. (2023) performed a power spectra analysis of the Planck data to characterize spatial variations of the SED of dust polarized emission in terms of the E and B–modes. We follow this analysis using Planck full- and half-mission sky maps4 at 100, 143, 217, and 353 GHz and end-to-end data simulations5 produced by the SRoll2 software, which corrects the main systematic effects that impact polarization on large angular scales (Delouis et al. 2019). We applied the scaling factors ![$\[\tilde{\rho}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq124.png) at frequency νi, listed in Table 1 of Ritacco et al. (2023), which represent corrections to the polarization efficiencies. We also applied dust color corrections listed in this table.

at frequency νi, listed in Table 1 of Ritacco et al. (2023), which represent corrections to the polarization efficiencies. We also applied dust color corrections listed in this table.

We used HEALPix pixelization (Górski et al. 2005) at Nside=32 (map pixel size of 1.8°). The resolution of the original maps was degraded applying a cosine filter in harmonic space (see formula (1) in Ritacco et al. 2023). We followed the procedure described in Sect. 2.2 of Ritacco et al. (2023) to subtract the synchrotron polarized emission from the maps at 100 and 143 GHz. We verified that uncertainties in the assumed spectral index of polarized synchrotron emission (βS = −3.19 ± 0.07, Ritacco et al. 2023) do not affect our results. We refer to the obtained maps as raw maps.

We applied the complex polarization formalism of Sect. 2 by computing the variances of residual maps. Our methodology follows that of Ritacco et al. (2023). We used half-maps (two independent versions of the same map) to compute covariances, craw, for the Planck data (see Appendix D). Our results cannot be compared directly with those of Ritacco et al. (2023) because the transformation from Q and U to E and B is non-local. For most of our data analysis, we used a single mask representing fsky = 97.3% of the sky, similar to the 97% mask of Ritacco et al. (2023). Our mask at Nside=32 (Fig. 3) was obtained by removing pixels at Galactic latitude |b| ≤ 3° in the inner Galaxy (−90° ≤ l ≤ 90°), as well as all pixels within 4° of the Crab pulsar. For certain plots, lower values of fsky were used (see Fig. 3); these masks were obtained by removing pixels from the 97.3% mask, ordered by decreasing optical depth, τ353, at 353 GHz.

In Section 5.3, we briefly comment on the comparison of our results obtained with SRoll2 maps and those obtained by applying the same methodology to the Planck PR4 maps. The PR4 Planck dataset is the latest and final Planck data release, available from the Planck Legacy Archive6. These Planck maps were produced by applying the NPIPE pipeline to the intensity and polarization data from both Planck-LFI and Planck-HFI (Planck Collaboration Int. LVII 2020), to create I, Q, and U calibrated maps for each frequency band. The PR4 data release comes with a comprehensive set of “end-to-end” Monte Carlo simulations processed with NPIPE, aimed at identifying and quantifying potential biases and the errors introduced by the pipeline.

|

Fig. 3 HEALPix masks with growing fsky (Nside = 32): 85% (dark blue), 90% (light blue), 92% (green), 95% (orange), and 97.3% (brown). The 97.3% mask additionally excludes the inner Galactic plane within 3 degrees of latitude and pixels within 4 degrees of the Crab pulsar (gray). |

4.2 Data simulations, debiasing, and error-bars estimation

To assess uncertainties associated with Planck satellite noise, including systematics, and the CMB signal, we computed a set of simulated maps based on various models of dust polarization from PYSM 3 (Thorne et al. 2017; Zonca et al. 2021; Group 2025). The d1 model is built from the Planck 353 GHz Legacy maps, extrapolated at lower frequencies with an MBB spectrum, using the spatially varying temperature and spectral index obtained from the Planck intensity data with the Commander code (Planck Collaboration 2015 X 2016). The d10 model is a refined version of d1, in which the templates for amplitude and spectral parameters have been extracted from the GNILC analysis of the Planck data (Planck Collaboration Int. XLVIII 2016; Planck Collaboration 2018 XII 2020), with smaller scales included using the so-called logarithm of the polarization fraction tensor formalism (for more details, see Group (2025)). Finally, the d12 model consists of up to six superposed layers of modified black bodies, each with spectral parameters drawn from Gaussian distributions (Martínez-Solaeche et al. 2018). The dust model maps were combined with the SRoll2 simulations of data noise and systematics (Delouis et al. 2019) and with CMB maps computed from the CMB power spectrum for the ΛCDM fiducial Planck model (Planck Collaboration 2018 VI 2020) as described in Sect. 3.2 of Ritacco et al. (2023). Overall, at each of the four Planck frequencies, we obtained Nsims = 200 sets of simulated Q and U full and half-mission maps, with independent realizations of data uncertainties and CMB anisotropies. The simulations were treated identically to the Planck data.

Our model is designed to study the frequency dependence of the variances, c, of dust polarized emission. The Planck data must be corrected for the bias introduced by noise, systematics, and the CMB in the raw data squared quantities, craw. For simulation number k, the bias introduced by noise, systematics, and the CMB on any squared quantity, c, is estimated as

where csims(k) and cdm represent the covariances of simulation k and of the chosen PYSM 3 dust model, respectively. Taking the raw biased data value craw, we obtain, for each simulation k, a debiased estimate, ![$\[\hat{c}(k)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq126.png) , for the covariance, c(k), in the Planck SRoll2 data:

, for the covariance, c(k), in the Planck SRoll2 data:

The debiased value, c, and its uncertainty, σc, are taken as the mean and standard deviation of ![$\[\hat{c}(k)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq128.png) over its 200 values, respectively.

over its 200 values, respectively.

From now on, we present only the results obtained using d1, our reference model. The results obtained using d10 and d12 are presented in the Appendix F; they do not differ significantly from those presented below, ensuring the robustness of our conclusions against the dust model used in our debiasing procedure.

4.3 Mean complex polarized SED

We extended earlier studies (Planck Collaboration Int. XXX 2016; Planck Collaboration 2018 XI 2020; Ritacco et al. 2023) to the complex plane using the cross-correlation of Planck maps, and determined the mean, debiased, complex SED ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq129.png) of dust polarization, normalized to our reference channel,

of dust polarization, normalized to our reference channel,

where ![$\[\tilde{\rho}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq131.png) is the correction to the polarization efficiency7 at frequency νi (Ritacco et al. 2023, Table 1). Similarly, we computed

is the correction to the polarization efficiency7 at frequency νi (Ritacco et al. 2023, Table 1). Similarly, we computed ![$\[\mathbf{r}_{i}^{\mathrm{dm}} \equiv\left\langle\mathbf{P}_{i} \mathbf{P}_{0}^{\star}\right\rangle_{\mathrm{dm}} /\left\langle\mathbf{P}_{0} \mathbf{P}_{0}^{\star}\right\rangle_{\mathrm{dm}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq132.png) for the dust model,

for the dust model, ![$\[\mathbf{r}_{i}^{\text {sim}}(k) \equiv\left\langle\mathbf{P}_{i} \mathbf{P}_{0}^{\star}\right\rangle_{k} /\left\langle\mathbf{P}_{0} \mathbf{P}_{0}^{\star}\right\rangle_{k}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq133.png) for simulation k, and

for simulation k, and ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}^{\text {sims}} \equiv {\sum}_{k=1}^{N_{\text {sims}}}\left\langle\mathbf{P}_{i} \mathbf{P}_{0}^{\star}\right\rangle_{k} / {\sum}_{k=1}^{N_{\text {sims}}}\left\langle\mathbf{P}_{0} \mathbf{P}_{0}^{\star}\right\rangle_{k}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq134.png) for the mean of all simulations.

for the mean of all simulations.

The uncertainty on the real and imaginary components of the mean simulated SED ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}^{\text {sims}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq135.png) is taken as the standard deviation of the corresponding real and imaginary components of the 200 simulation values

is taken as the standard deviation of the corresponding real and imaginary components of the 200 simulation values ![$\[\mathbf{r}_{i}^{\text {sim}}(k)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq136.png) . The uncertainty in the observed SED

. The uncertainty in the observed SED ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq137.png) must also include the uncertainty in the recalibration factor,

must also include the uncertainty in the recalibration factor, ![$\[\tilde{\rho}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq138.png) , of the Planck polarization data:

, of the Planck polarization data: ![$\[\sigma\left(\tilde{\rho}_{i}\right) / \tilde{\rho}_{i}=0.5 \%\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq139.png) . We repeated the procedure described in Sect. 4.2 200 times, each time drawing a distinct recalibration factor for each channel, i, from a random Gaussian distribution of expectation

. We repeated the procedure described in Sect. 4.2 200 times, each time drawing a distinct recalibration factor for each channel, i, from a random Gaussian distribution of expectation ![$\[\tilde{\rho}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq140.png) and standard deviation

and standard deviation ![$\[\sigma\left(\tilde{\rho}_{i}\right)=0.005 \tilde{\rho}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq141.png) . We debiased this realization with simulation k alone to compute the kth debiased estimate

. We debiased this realization with simulation k alone to compute the kth debiased estimate ![$\[\hat{\mathbf{r}}_{i}(k)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq142.png) of

of ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq143.png) . The uncertainty in the real and imaginary parts of

. The uncertainty in the real and imaginary parts of ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq144.png) is then taken as the standard deviation of the real and imaginary components of this set of 200 values

is then taken as the standard deviation of the real and imaginary components of this set of 200 values ![$\[\hat{\mathbf{r}}_{i}(k)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq145.png) , respectively. To test the assumption made in Sect. 2.5 to obtain Eq. (20), we computed the module of

, respectively. To test the assumption made in Sect. 2.5 to obtain Eq. (20), we computed the module of ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i} \frac{\overline{\varepsilon}_{0}}{\overline{\varepsilon}_{i}}-1\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq146.png) for a pivot SED,

for a pivot SED, ![$\[\overline{\varepsilon}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq147.png) , fitted to

, fitted to ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq148.png) , and found it smaller than 0.03 at all frequencies.

, and found it smaller than 0.03 at all frequencies.

Figure 4 shows the spectral dependence of the mean complex polarized SED in the log complex plane, for the raw SRoll2 data, the mean of simulations, the d1 dust model used for debiasing and the resulting debiased SED ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq149.png) . We observe a variation of the polarization angle with frequency in the data, which may appear significant. However, our estimate for the uncertainty on

. We observe a variation of the polarization angle with frequency in the data, which may appear significant. However, our estimate for the uncertainty on ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq150.png) does not include the uncertainty in the orientation of the Planck polarization bolometers. The most stringent estimates of these uncertainties come from the analysis of EB cross-spectra carried out to constrain cosmic birefringence (Planck Collaboration Int. XLIX 2016; Minami & Komatsu 2020; Diego-Palazuelos et al. 2022, 2023). Diego-Palazuelos et al. (2022) list their results in Table 1, per bolometer for several Galactic masks. The scatter among Galactic masks and the statistical uncertainties both lie in the range 0.2–0.3°. This agrees with the systematic uncertainty of 0.28° quoted by Planck Collaboration Int. XLIX (2016). The magnitude of this uncertainty reduces the significance of the imaginary component of our mean SED.

does not include the uncertainty in the orientation of the Planck polarization bolometers. The most stringent estimates of these uncertainties come from the analysis of EB cross-spectra carried out to constrain cosmic birefringence (Planck Collaboration Int. XLIX 2016; Minami & Komatsu 2020; Diego-Palazuelos et al. 2022, 2023). Diego-Palazuelos et al. (2022) list their results in Table 1, per bolometer for several Galactic masks. The scatter among Galactic masks and the statistical uncertainties both lie in the range 0.2–0.3°. This agrees with the systematic uncertainty of 0.28° quoted by Planck Collaboration Int. XLIX (2016). The magnitude of this uncertainty reduces the significance of the imaginary component of our mean SED.

While the mean complex SED, ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq156.png) , depends on calibration errors in amplitude (correction factors

, depends on calibration errors in amplitude (correction factors ![$\[\tilde{\rho}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq157.png) ) and in phase (absolute orientation of bolometers in the focal plane), the definition of map residuals (Eq. (18)), involving the ratio of Pi to

) and in phase (absolute orientation of bolometers in the focal plane), the definition of map residuals (Eq. (18)), involving the ratio of Pi to ![$\[\overline{\mathbf{r}}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq158.png) , renders the map residuals, and therefore their covariances, independent of any calibration error, whether in amplitude or in phase. This facilitates the comparison of different frequency maps or datasets with distinct systematics.

, renders the map residuals, and therefore their covariances, independent of any calibration error, whether in amplitude or in phase. This facilitates the comparison of different frequency maps or datasets with distinct systematics.

|

Fig. 4 Mean complex polarized SED |

4.4 Comparison of model predictions with Planck polarization data

In this section, we compare our model predictions and hypotheses with the Planck SRoll2 data. Using simulations, we have verified that the 0.5% in the recalibration factors ![$\[\tilde{\rho}_{i}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq159.png) does not have a noticeable effect on our results.

does not have a noticeable effect on our results.

First, we tested model prediction P1 by computing the Pearson correlation coefficient ![$\[\rho_{i j}=c_{i j} / \sqrt{c_{i i} c_{j j}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq160.png) , between the residual maps i and j. Our results for the R, RP, and Rψ residual maps are presented in Table 1 for all frequency pairs, using our 97.3% mask. The error bars on ρij are calculated from the standard deviation of the simulated values ρij(k), following the approach described in Sect. 4.2. We find that the correlation coefficient between the RP residual maps is consistent with a perfect correlation. The correlation between the angle residual maps, Rψ, is strong for the (217,143) pair, but weak for the (143,100) and (100,217) pairs, although with large uncertainties. Therefore, prediction P1 is validated for RP but not for Rψ. The correlation coefficient of Re cP is high but only marginally compatible with 100% for the (217,100) and (143,100) pairs. In the context of Eq. (33), this loss of correlation between the residual maps Ri is a consequence of the loss of correlation between the residual maps

, between the residual maps i and j. Our results for the R, RP, and Rψ residual maps are presented in Table 1 for all frequency pairs, using our 97.3% mask. The error bars on ρij are calculated from the standard deviation of the simulated values ρij(k), following the approach described in Sect. 4.2. We find that the correlation coefficient between the RP residual maps is consistent with a perfect correlation. The correlation between the angle residual maps, Rψ, is strong for the (217,143) pair, but weak for the (143,100) and (100,217) pairs, although with large uncertainties. Therefore, prediction P1 is validated for RP but not for Rψ. The correlation coefficient of Re cP is high but only marginally compatible with 100% for the (217,100) and (143,100) pairs. In the context of Eq. (33), this loss of correlation between the residual maps Ri is a consequence of the loss of correlation between the residual maps ![$\[R_{i}^{\psi}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq161.png) .

.

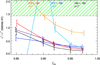

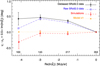

Second, we examined the validity of predictions P2 and P3, which relate cε and cψ to ![$\[\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq164.png) and

and ![$\[\left\langle I_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq165.png) , respectively. Fig. 5 shows how the variances, computed at 217 GHz for a high S/N ratio, depend on the polarization fraction, p0, at 353 GHz. This correlation plot is obtained by binning pixels of the 97.3% mask in bins of p0 and computing, for each p0 bin, the variances c at 217 GHzand the mean squared values,

, respectively. Fig. 5 shows how the variances, computed at 217 GHz for a high S/N ratio, depend on the polarization fraction, p0, at 353 GHz. This correlation plot is obtained by binning pixels of the 97.3% mask in bins of p0 and computing, for each p0 bin, the variances c at 217 GHzand the mean squared values, ![$\[\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq166.png) and

and ![$\[\left\langle I_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq167.png) (a method only applicable at the map level). A model,

(a method only applicable at the map level). A model, ![$\[c^{\varepsilon} \propto\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq168.png) , shown as a dashed orange line, confirms our prediction P2. Another model,

, shown as a dashed orange line, confirms our prediction P2. Another model, ![$\[c^{\psi} \propto\left\langle I_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq169.png) (dashed red line), also confirms the surprising prediction P3 of our model: cψ is reasonably proportional to

(dashed red line), also confirms the surprising prediction P3 of our model: cψ is reasonably proportional to ![$\[\left\langle I_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq170.png) , rather than

, rather than ![$\[\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq171.png) . Consequently, while cε follows

. Consequently, while cε follows ![$\[\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq172.png) as the polarization fraction tends toward zero, cP and Re cP saturate at positive values (prediction P4) due to depolarization effects (the variance of which is quantified here by cψ) that persist even at low p0.

as the polarization fraction tends toward zero, cP and Re cP saturate at positive values (prediction P4) due to depolarization effects (the variance of which is quantified here by cψ) that persist even at low p0.

Predictions P5 and P6 are compared to Planck SRoll2 data in Fig. 6, which shows how the ratio ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi} / c_{i j}^{P}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq173.png) varies with fsky, for all pairs (i, j) of residual maps. The error bars for this ratio are computed from simulations, following the approach described in Sect. 4.2. Prediction P5 (

varies with fsky, for all pairs (i, j) of residual maps. The error bars for this ratio are computed from simulations, following the approach described in Sect. 4.2. Prediction P5 (![$\[c^{\psi} / c^{P} \leq 1 / \overline{\eta}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq174.png) , unhashed region) is verified for all frequency pairs except for the variances at 100 and 143 GHz at lower fsky. This indicates that either the hypotheses of our model or the debiasing method break down at lower fsky. For the 95 and 97.3% masks, the cψ/cP ratio is, within error bars, almost independent of the frequency pair considered (prediction P6), with the notable exception of the variance at 100 GHz.

, unhashed region) is verified for all frequency pairs except for the variances at 100 and 143 GHz at lower fsky. This indicates that either the hypotheses of our model or the debiasing method break down at lower fsky. For the 95 and 97.3% masks, the cψ/cP ratio is, within error bars, almost independent of the frequency pair considered (prediction P6), with the notable exception of the variance at 100 GHz.

Overall, Table 1 and Fig. 6 highlight a limitation of our approach for the 100 GHz channel. In Sect. 6, we discuss to what extent this distinctive behavior can be attributed to dust physics beyond our hypotheses, to residual contamination by a component other than dust and CMB (e.g., synchrotron or CO emission), or to limitations of our debiasing method.

Finally, in Table 2, we test prediction P7, which states that ![$\[\operatorname{Im} \mathbf{c}_{i j}^{\mathbf{P}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq177.png) should be, within the uncertainties, close to zero for all frequency pairs. This prediction is not verified, even for the frequency pair (217,143) for which the residual maps show the strongest correlation (see Table 1). This result is puzzling, as our model does not predict any correlation between Rψ and RP, except for chance correlation. This issue is examined in more detail in the following section.

should be, within the uncertainties, close to zero for all frequency pairs. This prediction is not verified, even for the frequency pair (217,143) for which the residual maps show the strongest correlation (see Table 1). This result is puzzling, as our model does not predict any correlation between Rψ and RP, except for chance correlation. This issue is examined in more detail in the following section.

|

Fig. 5 Test of predictions P2, P3, and P4: dependence on the observed polarization fraction p0 = P0/I0 at 353 GHz of the variances Re cP, cP, cψ, and cε computed at 217 GHz. Our models for cε (P2) and cψ (P3) are overplotted as dotted orange and red lines, respectively, using the mean value of the slope derived from these equations, multiplied by |

|

Fig. 6 Test of predictions P5 and P6 as a function of fsky. The hashed region represents forbidden values according to P5. |

5 Inferring the variance of the spectral properties of aligned grains

Polarization observations trace the spectral properties of a specific population of dust grains that are aligned with the magnetic field lines. They can be compared with the overall spectral properties inferred from dust far-infrared (FIR) and submm total emission, which trace all grains, both aligned and unaligned. Assuming a common temperature8 for aligned and unaligned grains, Planck Collaboration 2018 XI (2020) found close values for the mean spectral index in polarization and intensity: βP − βI = 0.05 ± 0.03 in the high-latitude diffuse ISM. In this section, we extend this work by quantifying the variance of the fluctuations in the spectral properties of aligned grains for the 97.3% mask, where the signal is dominated by the Galactic plane. We trace these variations back to their origin in the fluctuations of β or T, and correlate them with the spectral fluctuations observed in total intensity.

|

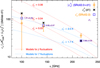

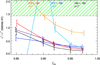

Fig. 7 Comparison of SRoll2 data with the predictions of our model for cP (blue) and cψ (red), for pure β fluctuations (top), and pure T fluctuations (bottom). |

5.1 Disentangling fluctuations of dust temperature and spectral index

As demonstrated in Sect. 3.1, the spectral gradients ![$\[a_{i, n}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq178.png) for n = 2 and n = 3 are strongly correlated with

for n = 2 and n = 3 are strongly correlated with ![$\[a_{i, 1}^{s}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq179.png) . By correlating the covariance matrices

. By correlating the covariance matrices ![$\[c_{i j}^{P}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq180.png) and

and ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq181.png) with

with ![$\[a_{i, 1}^{\beta} a_{j, 1}^{\beta}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq182.png) and

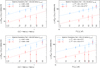

and ![$\[\overline{T}^{4} a_{i, 1}^{T} a_{j, 1}^{T}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq183.png) separately9, we aimed to identify whether these fluctuations originated mainly from variations in β or T, while simultaneously estimating their amplitude. This analysis is illustrated in Fig. 7 for pure β fluctuations (labeled (top)) and pure T fluctuations (labeled (bottom)). The spectral trends observed for cP and cψ are not compatible with a scenario in which they originate from fluctuations in β, as this scenario predicts a steeper slope. A better agreement is obtained if only the dust temperature T fluctuates. In the Galactic plane, starlight heating may indeed dominate the fluctuations of dust emission properties. For the variance in angles (cψ), fluctuations in T may also be favored, although the significant contamination observed in the 100 GHz residual angle map prevents a firm conclusion. To quantify these trends, we performed a χ2 minimization using the MPFITCOVAR IDL routine (Markwardt 2009). Our data combine the two data sets,

separately9, we aimed to identify whether these fluctuations originated mainly from variations in β or T, while simultaneously estimating their amplitude. This analysis is illustrated in Fig. 7 for pure β fluctuations (labeled (top)) and pure T fluctuations (labeled (bottom)). The spectral trends observed for cP and cψ are not compatible with a scenario in which they originate from fluctuations in β, as this scenario predicts a steeper slope. A better agreement is obtained if only the dust temperature T fluctuates. In the Galactic plane, starlight heating may indeed dominate the fluctuations of dust emission properties. For the variance in angles (cψ), fluctuations in T may also be favored, although the significant contamination observed in the 100 GHz residual angle map prevents a firm conclusion. To quantify these trends, we performed a χ2 minimization using the MPFITCOVAR IDL routine (Markwardt 2009). Our data combine the two data sets, ![$\[c_{i j}^{P}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq184.png) and

and ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq185.png) , into an array of 12 values. The corresponding 12 × 12 noise covariance matrix was computed from the covariances between the 200 simulated

, into an array of 12 values. The corresponding 12 × 12 noise covariance matrix was computed from the covariances between the 200 simulated ![$\[c_{i j}^{P}(k)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq186.png) and

and ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi}(k)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq187.png) covariance matrices (see Sect. 4.2). Using predictions P2, P3, and P4, we define a linear model for fluctuations in the spectral parameter s ∈ {T, β}, where

covariance matrices (see Sect. 4.2). Using predictions P2, P3, and P4, we define a linear model for fluctuations in the spectral parameter s ∈ {T, β}, where ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi}=a_{i, 1}^{s} a_{j, 1}^{s}\left(\sigma_{s}^{\psi}\right)^{2}\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq188.png) and

and ![$\[c_{i j}^{P}= a_{i, 1}^{s} a_{j, 1}^{s}\left(\sigma_{s}^{\varepsilon}\right)^{2}\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle+\overline{\eta} c_{i j}^{\psi}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq189.png) , with

, with ![$\[\sigma_{s}^{\psi} \equiv \sqrt{\operatorname{Cov}\left(\operatorname{Im\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{\mathbf{1}}^{s}, \operatorname{Im \boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{\mathbf{1}}^{s}\right)}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq190.png) and

and ![$\[\sigma_{s}^{\varepsilon} \equiv \sqrt{\operatorname{Cov}\left(\omega_{1}^{s}, \omega_{1}^{s}\right)}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq191.png) . When fitting with pure fluctuations in T, we obtain a χ2 of 15.7 (or 1.57 per degree of freedom). For pure β fluctuations, χ2 increases to 31. Removing

. When fitting with pure fluctuations in T, we obtain a χ2 of 15.7 (or 1.57 per degree of freedom). For pure β fluctuations, χ2 increases to 31. Removing ![$\[c_{100 \times 100}^{\psi}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq192.png) from the dataset clearly improves the fit for fluctuations in T (χ2/dof = 0.96), but not for fluctuations in β. Changing the value of

from the dataset clearly improves the fit for fluctuations in T (χ2/dof = 0.96), but not for fluctuations in β. Changing the value of ![$\[\overline{\eta}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq193.png) does not affect the χ2 of the fit’ it modifies only the value of

does not affect the χ2 of the fit’ it modifies only the value of ![$\[\sigma_{s}^{\varepsilon}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq194.png) , while keeping

, while keeping ![$\[\left(\sigma_{s}^{\varepsilon}\right)^{2}+\overline{\eta}\left(\sigma_{s}^{\psi}\right)^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq195.png) constant. Our best fit provides a reasonable value for the typical dispersion in dust temperature in the Galactic plane, corresponding to

constant. Our best fit provides a reasonable value for the typical dispersion in dust temperature in the Galactic plane, corresponding to ![$\[\sigma_{T}^{\varepsilon}=(2.7 \pm 0.1) ~\mathrm{K}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq196.png) for a reference temperature

for a reference temperature ![$\[\overline{T}=20 \mathrm{~K}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq197.png) .

.

Finally, Fig. 8 shows the frequency dependence of the mixed covariances ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi P}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq199.png) (Eq. (28)). This graph confirms that the 143 GHz channel behaves differently from the 217 and 100 GHz channels, possibly indicating contamination by CO emission in these two channels (see Sect. 6). A first-order model (dashed line) based on fluctuations of the dust temperature,

(Eq. (28)). This graph confirms that the 143 GHz channel behaves differently from the 217 and 100 GHz channels, possibly indicating contamination by CO emission in these two channels (see Sect. 6). A first-order model (dashed line) based on fluctuations of the dust temperature, ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi P}=a_{i, 1}^{T} a_{j, 1}^{T} \Sigma_{T}^{\psi P}\left\langle P_{0}^{2}\right\rangle\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq200.png) , with

, with ![$\[\Sigma_{T}^{\psi P} \equiv \operatorname{Cov}\left(\operatorname{Im\boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{\mathbf{1}}^{\boldsymbol{T}}, \operatorname{Re \boldsymbol{\mathcal{W}}}_{\mathbf{1}}^{\boldsymbol{T}}\right)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq201.png) , cannot reproduce the observations. A model based on fluctuations in β also fails. The frequency dependence of the mixed covariances

, cannot reproduce the observations. A model based on fluctuations in β also fails. The frequency dependence of the mixed covariances ![$\[c_{i j}^{\psi P}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq202.png) , together with the values of

, together with the values of ![$\[\operatorname{Im} \mathbf{c}_{i j}^{\mathbf{P}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa56491-25/aa56491-25-eq203.png) (Table 2), warrants further detailed analysis. We defer this to future work.

(Table 2), warrants further detailed analysis. We defer this to future work.

|

Fig. 8 Covariances |

5.2 Correlating fluctuations in intensity and polarization