| Issue |

A&A

Volume 703, November 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A79 | |

| Number of page(s) | 30 | |

| Section | Stellar atmospheres | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555732 | |

| Published online | 07 November 2025 | |

Evidence for SiO cloud nucleation in the rogue planet PSO J318

1

Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie,

Königstuhl 17,

69117

Heidelberg,

Germany

2

Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, ETH Zurich,

Wolfgang-Pauli-Str 27,

8093

Zürich,

Switzerland

3

SRON Space Research Organisation Netherlands,

Niels Bohrweg 4,

2333

CA

Leiden,

The Netherlands

4

Université Paris Cité, Université Paris-Saclay, CEA, CNRS, AIM,

91191

Gif-sur-Yvette,

France

5

Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University,

PO Box 9010,

6500

GL

The Netherlands

6

Department of Astrophysics, University of Vienna,

Türkenschanzstr. 17,

1180

Vienna,

Austria

7

Institute of Solid State Physics, Friedrich Schiller University,

Jena,

Germany

8

Department of Astronomy & Astrophysics, University of California,

Santa Cruz,

CA

95064,

USA

9

Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Rochester,

Rochester,

NY

14627,

USA

10

Institute of Astronomy, KU Leuven,

Celestijnenlaan 200D,

3001

Leuven,

Belgium

11

Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory,

Edinburgh

EH9 3HJ,

UK

12

Centre for Exoplanet Science, University of Edinburgh,

Edinburgh

EH9 3FD,

UK

13

STAR Institute, Université de Liège,

Allée du Six Août, 19C,

4000

Liège,

Belgium

14

Centro de Astrobiología (CAB), CSIC-INTA, ESAC Campus, Camino bajo del Castillo s/n,

28692

Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid,

Spain

15

Université Paris-Saclay, CEA, IRFU,

91191

Gif-sur-Yvette,

France

16

UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Royal Observatory Edinburgh,

Blackford Hill,

Edinburgh

EH9 3HJ,

UK

17

Department of Astronomy, Stockholm University, AlbaNova University Center,

10691

Stockholm,

Sweden

18

School of Physics & Astronomy, Space Park Leicester, University of Leicester,

92 Corporation Road,

Leicester

LE4 5SP,

UK

19

LIRA, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, Sorbonne Université, Sorbonne Paris Cité, CY Cergy Paris Université, CNRS,

5 place Jules Janssen,

92195

Meudon,

France

20

Université Paris-Saclay, UVSQ, CNRS, CEA, Maison de la Simulation,

91191

Gif-sur-Yvette,

France

21

Department of Astrophysics, American Museum of Natural History,

Central Park West at 79th Street,

New York,

NY

10024,

USA

22

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University,

PO Box 9513,

2300

RA

Leiden,

The Netherlands

23

School of Cosmic Physics, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies,

31 Fitzwilliam Place,

Dublin

D02 XF86,

Ireland

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

29

May

2025

Accepted:

24

July

2025

Silicate clouds have long been known to significantly impact the spectra of late L-type brown dwarfs – with observable absorption features at ~10 μm. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has reopened a window to the mid-infrared with unprecedented sensitivity, bringing the characterization of silicate clouds into focus again. Using JWST, we aim to characterize the planetary-mass brown dwarf PSO J318.5338-22.8603, concentrating on any silicate cloud absorption the object may exhibit. PSO J318’s spectrum is extremely red, and its flux is variable, both of which are thought to be hallmarks of cloud absorption. We present JWST NIRSpec PRISM, G395H, and MIRI MRS observations of PSO J318 from 1 to 18 μm. We introduce a method based on PSO J318’s brightness temperature to generate a list of cloud species that are likely present in its atmosphere. We tested for the species’ presence with petitRADTRANS retrievals. Using retrievals and grids from various climate models, we derived bulk parameters from PSO J318’s spectra, which are mutually compatible. Our retrieval results point to a solar to a slightly super-solar atmospheric C/O, a slightly super-solar metallicity, and a 12C/13C below ISM values. The atmospheric gravity proves difficult to constrain for both retrievals and grid models. Retrievals describing the flux of PSO J318 by mixing two 1D models (“two-column models”) appear favored over single-column models; this is consistent with PSO J318’s variability. The JWST observations also reveal a pronounced absorption feature at 10 μm. This absorption is best reproduced by introducing a high-altitude cloud layer of small (<0.1 μm) amorphous SiO grains. The retrieved particle size and location of the cloud is consistent with SiO condensing as cloud seeding nuclei. High-altitude clouds comprised of small SiO particles have been suggested in previous studies. Therefore, the SiO nucleation we potentially observe in PSO J318 could be a more widespread phenomenon.

Key words: radiative transfer / methods: numerical / techniques: spectroscopic / planets and satellites: atmospheres / brown dwarfs

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open Access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1 Introduction

Brown dwarfs can be thought of as occupying the mass space between the most massive gas giant planets and the lowest mass stars. While their formation likely corresponds to the low-mass end of the star formation process (e.g., Chabrier et al. 2014), they differ from stars by having masses too low (M ≲ 75 MJup) to sustain prolonged hydrogen fusion on the main sequence (e.g., Burrows et al. 1997). The main observable difference between the physical properties of brown dwarfs and gas giant planets is that the latter tend to be less massive and may have different metal enrichment patterns in their H2/He-dominated envelopes and atmospheres. Since planet formation is strongly dependent on initial conditions and driven by many complex, interlocked, and stochastic processes, a greater diversity in compositions is expected for planets (e.g., Öberg et al. 2011; Madhusudhan et al. 2014; Mordasini et al. 2016; Mollière et al. 2022). The brief period of deuterium burning, often used to define the lower mass limit of brown dwarfs, has little effect on the properties of a brown dwarf (except to slow down cooling somewhat), and both massive planets and low-mass brown dwarfs with masses around 13 MJup can burn a fraction of their deuterium over time (e.g., Spiegel et al. 2011; Mollière & Mordasini 2012; Bodenheimer et al. 2013).

The similarity between low-mass brown dwarfs and exoplanets has led to brown dwarfs being called “free-floating” or “rogue” planets and “isolated planetary-mass objects”. The similarity is reflected in the spectra of particularly young low-mass brown dwarfs, which are closely related to those of young gas giant exoplanets. Studying brown dwarfs and planets together will thus reveal a more complete picture of cold substellar atmospheres (e.g., Faherty 2018), while isolated brown dwarfs have the obvious advantage of not suffering from the photon noise of an overwhelmingly bright host star.

The pressure-temperature conditions in the atmospheres of exoplanets and brown dwarfs include regions where silicates are thermodynamically stable. Therefore, we expect to detect their presence via spectroscopy. Indirect evidence of clouds in brown dwarfs has long been claimed from the “reddened” appearance of their spectra (i.e., near-IR emission is suppressed when compared to theoretical cloud-free predictions, see, e.g., Tsuji et al. 1996; Allard et al. 2001). Mid-infrared wavelengths were first accessible with Spitzer, and they revealed the absorption due to Si-O stretching modes of silicate grains with sizes ≲1 μm at wavelengths of ~10 μm (Cushing et al. 2006). This signature was subsequently detected in a number of L-type brown dwarfs (Suárez & Metchev 2022). Work by Luna & Morley (2021); Suárez & Metchev (2023) have indicated that the corresponding clouds in some objects may be located at higher altitudes than classically expected, are consistent with small particle sizes ≲0.1 μm, and may consist of amorphous SiO or MgSiO3. Relatedly, the work by Campos Estrada et al. (2025) has indicated that small (SiO)N clusters forming as cloud seeding nuclei high in the atmospheres of brown dwarfs and directly imaged planets may describe the subsequent cloud formation better than the typically assumed TiO2 seeds when comparing model spectra with observations (but we note that their models did not produce a 10 μm feature itself). With the emergence of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), it soon became clear that its increased signal-to-noise (Gardner et al. 2023), especially of its MIRI instrument, would enable a detailed characterization of clouds. JWST has now detected evidence of 10 μm absorption in a number of brown dwarf companions and exoplanets (e.g., Miles et al. 2023; Grant et al. 2023; Dyrek et al. 2024; Inglis et al. 2024; Hoch et al. 2025).

Here we study the atmosphere of the young low-mass brown dwarf PSO J318.5338-22.8603 (called PSO J318 in the following). PSO J318’s discovery with Pan-STARRS1 was reported by Liu et al. (2013), who emphasized the brown dwarf’s extremely red color and planet-like faintness. Together with the weak alkali absorption and the triangular shape of PSO J318’s H-band spectrum (two signs of low gravity), the picture of a low-mass brown dwarf with a likely very cloudy atmosphere arises. PSO J318 is an assigned member of the β Pic moving group (Barrado y Navascués et al. 1999), so it should be young, and Liu et al. (2013) estimated its mass to be ![$\[6.5_{-1.0}^{+1.3}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq1.png) MJup using evolutionary models, assuming a uniform age prior of

MJup using evolutionary models, assuming a uniform age prior of ![$\[12_{-4}^{+8}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq2.png) Myr, which is consistent with the low gravity inferred from its spectrum (however, we note that the currently accepted age is around 24 Myr, see Mamajek & Bell 2014). An updated value of 8.3 ± 0.5 MJup was determined by Allers et al. (2016). The near-infrared (NIR) spectra presented in Liu et al. (2013) lacked any sign of methane absorption, and the authors derived a spectral type of L7±1. This makes PSO J318 about 400 K cooler (they derived Teff =

Myr, which is consistent with the low gravity inferred from its spectrum (however, we note that the currently accepted age is around 24 Myr, see Mamajek & Bell 2014). An updated value of 8.3 ± 0.5 MJup was determined by Allers et al. (2016). The near-infrared (NIR) spectra presented in Liu et al. (2013) lacked any sign of methane absorption, and the authors derived a spectral type of L7±1. This makes PSO J318 about 400 K cooler (they derived Teff = ![$\[1160_{-40}^{+30}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq3.png) K) than field brown dwarfs of the same spectral type.

K) than field brown dwarfs of the same spectral type.

Another noteworthy property of PSO J318 is its flux variability (Biller et al. 2015). It is thought to stem from brightness inhomogeneities across its top-of-atmosphere structure that rotate in and out of view and evolve. Multiple properties could conceivably vary and thus produce these inhomogeneities (clouds, temperature, or chemical composition, see Biller 2017). The contemporaneous HST and Spitzer light curves of PSO J318 reported in Biller et al. (2018) resulted in a constraint on the rotational period of 8.6 ± 0.1 hr, which led to an inclination of i = 56.2 ± 8.1° when combined with the v sin(i) = ![$\[17.5_{-2.8}^{+2.3}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq4.png) km/s of Allers et al. (2016). Biller et al. (2018) derived peak-to-trough variabilities 3.4 ± 0.1% for Spitzer and 4.4–5.8% across the spectral points of HST WFC3. For WFC3, the authors found the magnitude of variability to be approximately independent of wavelength. Since cloud cross-sections for absorption and scattering can be gray (i.e., constant with wavelength), this hints at cloud heterogeneity as a possible cause. Intriguingly, the authors also found a phase offset of ~200° between the variability of Spitzer and HST measurements, indicating at a pressure-dependent heterogeneity structure.

km/s of Allers et al. (2016). Biller et al. (2018) derived peak-to-trough variabilities 3.4 ± 0.1% for Spitzer and 4.4–5.8% across the spectral points of HST WFC3. For WFC3, the authors found the magnitude of variability to be approximately independent of wavelength. Since cloud cross-sections for absorption and scattering can be gray (i.e., constant with wavelength), this hints at cloud heterogeneity as a possible cause. Intriguingly, the authors also found a phase offset of ~200° between the variability of Spitzer and HST measurements, indicating at a pressure-dependent heterogeneity structure.

Recent evidence for the presence of clouds and the variability of brown dwarfs being correlated was established by Vos et al. (2017) and Suárez et al. (2023). Vos et al. (2017) found that the most variable brown dwarfs, that is, those seen equator-on, exhibit redder spectral energy distributions than brown dwarfs seen pole-on. Additionally, Suárez et al. (2023) showed that silicate cloud absorption features in the mid-infrared are more prominent for brown dwarfs viewed equator-on. Thus variability correlates with redness and cloud absorption, and equatorial regions appear to be more cloudy. Another noteworthy finding has been presented in Vos et al. (2023), where the authors showed with archival Spitzer IRS data that the atmospheres of the two variable, early-T brown dwarfs SIMP-0136 and 2M 2139 are best described as having patchy silicate clouds. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2025) find that the atmosphere of the known variable companion 2M1207b is best described by patchy silicate clouds, based on JWST NIRSpec data. This may point to clouds as a likely variability driver. However, we note that in principle, spectra could be reddened by two effects: (i) clouds could “hide” the deep hot atmosphere otherwise probed in the NIR and (ii) the deep atmosphere could be colder than expected, so it no longer needs to be hidden (Tremblin et al. 2015, 2016, 2017, 2019). Numerous ongoing JWST programs are investigating the cause of variability in brown dwarf atmospheres, and many point to a complex picture of cloud, temperature, and compositional heterogeneities (see Biller et al. 2024; McCarthy et al. 2025; Chen et al. 2025, and many more ongoing JWST programs). A noteworthy recent study is the work by Nasedkin et al. (2025), who ran the first time-dependent retrievals of a variable brown dwarf observed with JWST (the T2 dwarf SIMP-0136) and found that its variability is likely caused by temperature and chemical fluctuations.

In this paper, we aim to study the panchromatic JWST spectrum of PSO J318 obtained with the GTO program 1275 (PI Lagage) with the goal of characterizing PSO J318’s atmosphere and studying its silicate cloud absorption. Our focus lies on identifying the clouds’ constituent species (e.g., MgSiO3 vs. Mg2SiO4), constraining the particle structure (i.e., crystalline vs. amorphous) and size, and assessing their spatial distribution (i.e., determining whether the clouds are homogeneous or “patchy”) and altitude in the atmosphere. While our observations were taken over multiple hours, capturing a significant fraction of PSO J318’s rotational period, we do not attempt to constrain whether they contain a variability signal.

In Section 2, we describe the new and archival observations used in this work. Section 3 contains an overview of the relevant factors that shape the wavelength-dependent opacity of silicates and then focuses on the identification of the species that causes PSO J318’s silicate feature with a method based on brightness temperatures and with retrievals. In Section 4, we discuss the bulk atmospheric properties of PSO J318, as obtained from comparisons to grid models in radiative-convective equilibrium and retrievals, and we further characterize PSO J318’s silicate cloud. Our findings are summarized and discussed in Section 5.

2 Observations

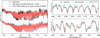

The full spectrum of PSO J318, combining all the observations as used in our atmospheric analysis, is shown in Figure 1. Below we describe the JWST observations and data reduction as well as the provenance of the archival data.

2.1 JWST observations

We observed PSO J318 with JWST as part of the ExOMIRI GTO consortium, GTO program #1275 (PI Lagage). We collected data with NIRSpec PRISM, NIRSpec G395H (Jakobsen et al. 2022), all three MIRI MRS gratings, and with the MIRI imager (Rieke et al. 2015). Together, this provides a spectrum of PSO J318 with complete coverage from 0.6 μm to 27.9 μm, with a resolution R > 100 throughout and R > 1500 for all wavelengths longer than 2.87 μm.

Our observations were collected on 12 June 2023, between UTC 03:45:34 and 06:19:44. The whole sequence lasted 2 h and 34 min, corresponding to roughly 30% of a full rotation of PSO J318. Our observing sequence was as follows: we first collected MIRI MRS observations, using all three gratings (LONG, MEDIUM, SHORT) sequentially. Combined with all four channels (observed simultaneously), this provides data from 4.9 μm to 27.9 μm at R ~ 1500–3500. However, the thermal background becomes increasingly dominant at the longest wavelengths while PSO J318 becomes increasingly faint. In the current work we consider only channels 1,2, and 3, and ignore data beyond 18 μm (i.e., data from Channel 4). For these MIRI MRS observations we used a 2-point dither pattern, with 86 groups/integration and 1 integration/exposure, for a total integration time of 477.3 s per sub-channel. While integrating with MIRI MRS, we also collected simultaneous MIRI images in the F1280W filter, but those are not used in the current work. We then collected MIRI imaging in four photometric filters: F1800W, F2100W, F1280W and F1500W; also these images are not used in the current work, since they add little additional information compared to the spectra.

Next we collected NIRSpec data using the PRISM grating and the CLEAR filter, providing data from 0.6 μm to 5.3 μm at a mean resolution of R ~ 100. We used a 4-point nod pattern, with 2 groups/integration and 2 integrations/exposure, for a total of 350.1 s of integration. Finally, we collected observations with NIRSpec using the G395H grating and the F290LP filter, providing data from 2.87 μm to 5.14 μm at R ~ 2700. We used a 4-point-nod pattern, with 6 groups/integration and 1 integration/exposure, for a total of 408.5 s of integration.

|

Fig. 1 Observations considered for the atmospheric characterization of PSO J318. Uppermost panel: all data considered for the spectral characterization of PSO J318at the wavelength binning fed into the retrieval and self-consistent grid model fits. Specifically, MIRI MRS data was binned down to λ/Δλ = 400, while NIRSpec G395H was binned to λ/Δλ = 400 and λ/Δλ = 1000 for NRS1 and NRS2, respectively. Second panel: HST WFC3, IRTF SpeX, and JWST NIRSpec PRISM data over the 1–3 μm wavelength range. Third panel: JWST NIRSpec G395H data at the full spectral resolution. Lowermost panel: JWST MIRI MRS data at the full spectral resolution. |

2.2 JWST data reduction

For the NIRSpec data reductions (both PRISM and G395H) we directly used the *x1d.fits files from the MAST data archive. We include the PRISM data from 1 μm onwards, and disregard it for wavelengths longer than 3 μm, since they exhibit a flux excess and unexpected systematic behavior when compared to the G395H data. Within our adopted range the NIRSpec data of PRISM and G395H are in good mutual agreement. PRISM also lines up with archival HST and IRTF observations at short, while G395H lines up with the bluest MIRI MRS channel (1A) at long wavelengths (see Fig. 1).

We performed our own reduction for the MIRI MRS data, using the public jwst pipeline1 (version 1.12.5, CRDS reference files jwst_1149.pmap, Bushouse et al. 2023). We started from the *uncal.fits files, and applied all three stages of the standard data reduction. Stage 1 produces *rate.fits files, that is, the rate of photoelectric charge accumulation on the detector. In Stage 2 the world coordinate system (wcs) is applied, and several calibrations are applied to produce photometrically calibrated *cal.fits files. The calibrations applied here include a flat field, stray light, residual fringe and photometric correction. Between Stage 2 and 3 we perform a nod subtraction between dither positions to reduce the residual background. Finally, Stage 3 projects the 2D spectra into 3D cubes (x/y/λ, *s3d.fits) using the “drizzle” weighting algorithm (Law et al. 2023). Here, we include an outlier detection, flagging remaining outliers due to, for example, cosmic rays. A one-dimensional spectrum (*x1d.fits) can then be extracted from this cube by placing an aperture of one Full Width Half Maximum (FWHM) of the corresponding Point Spread Function (PSF) around the source and measuring the contained flux at each wavelength. The mid-point of the source is detected using the ifu_autocen() built-in function.

We also applied an additional correction to the MRS data to account for large-scale systematics, which were apparent in the spectrum produced by the jwst pipeline. Examination of the IFU cubes revealed significant, wavelength-dependent structure in the background, even after the dither subtraction; this leads to wavelength-dependent systematics in the extracted spectrum when using the default pipeline. To correct for this systematic we follow the process described in Matthews et al. (2025). Briefly, we calculated the 3D cubes in the ifualign orientation, where the striping is largely horizontal. We then masked out the source and modeled the background structure for each individual λ slice in a data-driven fashion. This background can then be subtracted, and the spectrum extracted from the cube using the standard jwst pipeline methods. With this correction, our final spectra are smooth in the mid-infrared, well-explained with physical models, and show good agreement in the regions where consecutive sub-channels overlap.

2.3 Archival data

In addition to JWST observations we considered the archival NIR spectra taken with HST WFC3 by Biller et al. (2018). We included all spectra taken during five consecutive HST orbits in our analysis, spanning 7 hr, so almost one full rotation of the object. We also included ground-based archival NIR spectroscopy from IRTF SpeX, taken by Liu et al. (2013). This data set was included from wavelengths larger than 1 μm, out to wavelengths of 2.35 μm. Wavelengths shorter than 1 μm were excluded for numerical efficiency, and because PSO J318becomes increasingly faint (leading to low S/N data). Wavelengths longer than 2.3 μm were excluded because of low S/N. These archival data sets show good mutual agreement (neglecting the fact that HST is actually precise enough to show PSO J318’s variability), and agree well with JWST NIRSpec PRISM, see Fig. 1.

3 Characterizing PSO J318’s 10 μm silicate feature

The data we present in Fig. 1 exhibits a prominent absorption feature at ~10 μm, which we attribute to silicates, that is, absorption by condensed silicon-oxide-rich material in the atmosphere of PSO J318. Silicon is one of the most abundant refractory elements in the universe (e.g., Asplund et al. 2009). In its condensed form it constitutes a major opacity source, especially at 10 μm. In addition to the aforementioned brown dwarfs and planets, silicate absorption is evident in outflows of evolved AGB stars, ejecta of supernovae, proto-planetary and debris disks, the interstellar medium and AGN dust tori (for a detailed review see Henning 2010).

Since we posit that silicates cause the 10 μm absorption, in the following we explore what type of silicate material may be present in the atmosphere of PSO J318. For planets or brown dwarfs silicates of olivine-type stoichiometry (Mg2−xFexSiO4), pyroxene-type (Mg1−xFexSiO3) and quartz (SiO2) are expected species, with their relative importance likely determined by atomic abundance ratios such as Mg/Si (Calamari et al. 2024) and potentially C/O (Wetzel et al. 2013). The internal structure of silicates can be crystalline, that is, the elemental building blocks are arranged on a regularly repeating lattice, or amorphous. We note that the amorphous state is not well defined. It can range from configurations of small crystalline domains that do not properly connect to disarray on a smaller level, where crystalline ordering is missing altogether (Henning 2010). In studies of silicates forming around evolved stars and in proto-planetary disks it was found that crystalline silicates tend to be Fe-poor (e.g., Jaeger et al. 1998; Olofsson et al. 2009; Juhász et al. 2010), which is consistent with theoretical models predicting that Fe should be more abundant in amorphous silicates, that form at lower temperatures (Gail 2010).

Recent studies that investigated the broad silicate feature visible in Spitzer IRS spectra found that the 10 μm feature is best explained by amorphous silicate absorption. Luna & Morley (2021) constrained particle sizes to be small (≲0.1–1 μm), and consisting of SiO, MgSiO3, or Mg2SiO4. Suárez & Metchev (2023) found that the visible clouds consist of amorphous pyroxene-type (Mg1−x FexSiO3) material for low-gravity brown dwarfs (with particle sizes around 1 μm), while high-gravity brown dwarfs may be dominated by small (≲0.1 μm) grains composed of amorphous SiO and MgSiO3.

Since a 10 μm-feature of a putative silicate cloud appears to be present in PSO J318’s spectrum, we first attempt to study its grain properties based on the spectral shape from 7–13 μm alone in Section 3.1. This is done in an agnostic manner (i.e., neglecting the constraints on composition from Luna & Morley 2021; Suárez & Metchev 2023). This can be seen as a precursor step before turning to the numerically costly retrievals, which are presented in Section 3.2. We expect that the shape of the 10 μm feature is sensitive to the following particle properties:

Particle structure. Silicate crystals have sharp absorption features stemming from Si-O stretching transitions. In amorphous particles the crystal structure is lost. The corresponding distribution of bond lengths and angles in the resulting solid leads to a much wider, less structured absorption feature at 10 μm (Dorschner et al. 1995; Henning 2010). If condensation nuclei that form the seed particles for cloud particle growth are prevalent and mixing is slow, silicates in the atmospheres of exoplanets and brown dwarfs should condense at high temperatures, as soon as gas is mixed into regions where condensates are thermodynamically stable. This would result in crystalline particles, because amorphous grains are very efficiently and quickly converted into crystals at high temperatures (so-called annealing, see, e.g., Fabian et al. 2000; Gail 2001; Harker & Desch 2002; Gail 2004). The broad, presumably amorphous absorption features seen in VHS 1256b (Miles et al. 2023), PSO J318 and the Spitzer spectra of many brown dwarfs (Luna & Morley 2021; Suárez & Metchev 2023) are therefore unexpected and point to a gap in our understanding of cloud physics. We also note that, for some stoichiometries, multiple crystalline forms may exist, with distinct spectral features. The stability regimes of these so-called polymorphs depend on temperature. Conversion timescales between polymorphic phases at temperatures relevant for atmospheres are in the range of hours. This may also make the occurrence of mixed polymorph grains possible, which could further transition through an amorphous stage during polymorph transformation (Moran et al. 2024).

Particle composition. Particle composition has a large effect on the shape and the exact location of the 10 μm feature. For example, as one moves from quartz (SiO2) to enstatite (MgSiO3) to forsterite (Mg2SiO4) the degree of polymerization of SiO4 tetrahedra drops, leading to a shifting of the 10 μm feature to redder wavelengths (Henning 2010). The location and number of the narrow absorption maxima observed for crystalline silicates likewise changes as the composition of the grains is varied. Adding iron to the condensates described above (e.g., MgFeSiO4 instead of Mg2SiO4 when considering particles of olivine-type stoichiometry) further reddens the onset of the 10 μm band, because the bond lengths between Fe and O are longer than between Mg and O (Jaeger et al. 1998). This effect is clearly discernible in crystalline silicates. In amorphous silicates, however, it can be obscured by other factors, including differences in disorder, shape and size. In addition, it is not necessarily the case that cloud particles are composed of just one species. In principle, particles could be layered (one species condensing on top of another) or more strongly mixed. For mixed particles, the characteristic absorption features (e.g., crystalline absorption features) could be muted (Kiefer et al. 2024). The degree to which this is important is not clear, and we note that the silicate absorption seen in circumstellar disks can show both amorphous and crystalline features of uniquely identifiable species simultaneously (e.g., van Boekel et al. 2005; Juhász et al. 2010).

Particle shape. The most common assumption for the shape of a cloud particle is a sphere, which enables the use of Mie theory to calculate the cross-sections of particles (e.g., Bohren & Huffman 1983). This approximation is likely incorrect, especially for solid particles (e.g., consider the shape of a snowflake). Several treatment options exist, all of which are more numerically costly than a simple Mie treatment, and all of them require additional parameters to describe the deviation of a particle from a sphere. Examples are treating particles as distributions of hollow spheres (DHS, see Min et al. 2005), continuous distributions of ellipsoids (CDE, see Bohren & Huffman 1983) or to fully specify the shape of a grain and estimating its cross section using the discrete dipole approximation (DDA, see, e.g., Purcell & Pennypacker 1973; Draine 1988). The wavelength location of the crystalline absorption features can move significantly if deviations from spherical grains are considered, and indeed such a departure has been inferred for most of the crystalline silicate absorption in protoplanetary disks (e.g., Bouwman et al. 2001; Juhász et al. 2010). An example of how the particle shapes affect exoplanet transmission spectra with crystalline clouds can be found in Mollière et al. (2017). Amorphous silicate absorption is less strongly influenced by the assumed particle shape; it mainly changes the extent of the 10 μm-feature towards red wavelengths, while the blue onset of the feature is largely unaffected (e.g., Henning & Stognienko 1993; Min 2015).

Particle size (distribution). The particle size significantly affects the wavelength-dependent cross-sections of clouds. For example – as follows from Mie theory – scattering is strongest for wavelengths λ ≪ 2πr, where r is the particle radius, and decreases with λ−4 for wavelengths ≫ 2πr. In addition, the 10 μm silicate absorption feature begins to disappear for grains of sizes ≳1 μm, and its shape likewise depends on the particle size (e.g., Min 2015). It is therefore not surprising that also the particle size distribution plays an important role for determining the shape of the 10 μm absorption feature. Log-normal particle size distributions, which appear symmetric around a characteristic size in logged particle size are a common assumption (e.g., Ackerman & Marley 2001; Morley et al. 2012; Nasedkin et al. 2024; Morley et al. 2024, to name just a few studies). Another example is the Hansen distribution (Hansen 1971; Burningham et al. 2021; Vos et al. 2023) which can be asymmetric, depending on the choice of parameters, and may exhibit broad shoulders. Finally, there are fully microphysical models that solve for the particle size distribution as a function of altitude by considering processes such as condensation, settling, and coagulation, etc. (e.g., Helling et al. 2008; Gao et al. 2018; Powell et al. 2018). These studies often point to complex, multi-modal distributions, although it should be explored which particle sizes inferred from this full treatment actually matter when calculating spectra. In addition, it is not likely that cloud properties are constant across the atmosphere of a planet or brown dwarf, which can affect the aggregate shape of the 10 μm feature that arises from averaging fluxes across the visible hemisphere of the object.

Even if the above properties of the cloud species were perfectly known, biases are likely to impact analyses due to the challenges of deriving optical constants in laboratories. For instance, samples of the species of interest may be hard to synthesize. One way of producing amorphous silicates is through melts in a high-temperature furnace and subsequent cooling (with rates of ~1000 K/s) to prevent crystallization (Jäger et al. 1994; Dorschner et al. 1995). Such samples are called “glassy” in the following. However, while MgFeSiO4 has a melting point of manageable 1900 K, Mg2SiO4 only melts at ~2200 K, which is hard to achieve in a laboratory setting. For such species the so-called sol-gel method is used, where metal organic compounds are dissolved in mixtures of water and alcohol (methanol or ethanol), hydrolized and finally condensed as a three-dimensional magnesium silicate network, the “silicate gel” (see, e.g., Jäger et al. 2003a). The condensed gel is then distilled in order to remove the water and alcohol present, and subsequently annealed at elevated temperatures in order to remove the porosity and to densify the material (but not enough to let it crystallize). A challenge associated with silicate samples produced by melting or by the sol-gel method is the derivation of optical constants at wavelengths corresponding to low absorption. The best solution would be transmission measurements of thick samples to determine the absorption coefficient directly from the transmission. If this is not possible, extrapolation is a commonly employed solution. However, this can result in discrepancies in the optical data close to the blue onset of the 10 μm feature between the silicates generated by melting or by sol-gel.

A last complication we want to mention here is that optical properties of a material sample depend on its temperature. This is most important for the absorption features of crystalline silicates where peaks become broader and shift location for higher temperatures (e.g., Zeidler et al. 2015). Interestingly, this may affect the 10 μm feature somewhat less compared to the longer wavelength silicate absorption features towards the far-infrared (λ ≳ 30 μm, see Koike et al. 2006). In all analyses in this work we neglect the temperature dependence of the silicate opacities. This is a common, but not necessarily justified, assumption in the community.

3.1 Silicate feature analysis with the brightness temperature method

Given the aforementioned complexities that influence what the 10 μm absorption of a cloud will look like, it would be preferable to have an efficient method for identifying cloud candidate species in a first-look approach, that is, before running numerically costly retrievals. We present and apply a potentially useful method for this in the following. Since we treat this demonstration as a proof of principle, only a subset of the cloud complexities was explored in this study.

3.1.1 Fitting procedure

In an optically thin slab of gas and condensates, information about the silicates could be extracted by directly comparing the observed flux F(ν), where ν is the spectral frequency, to predicted opacities κ(ν), where opacity is defined as cross-section per unit mass. This is because in the optically thin limit the flux is described by

![$\[F(\nu) \propto \kappa(\nu) B(\nu, T),\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq5.png) (1)

(1)

where B(ν, T) is the Planck function, and T is the silicate dust temperature. The atmosphere of a giant planet or brown dwarf is never optically thin. Instead, at every frequency one can only probe into the atmosphere until it becomes optically thick, which defines the so-called photosphere. Commonly the optical depth at the photosphere is assumed to be τ ≈ 2/3, although we note that emission is a continuous process, and the observed flux arises from regions at both lower and higher τ. The above relation then no longer holds but can be replaced by an expression that relates the atmospheric brightness temperature, Tbright, to the opacity if making the simplifying assumption that the flux is emitted from τ = 2/3 exactly (or another fixed point):

![$\[\ln [\kappa(\nu)] \approx-\frac{\ln \left[T_{\text {bright}}(\nu)\right]}{\nabla}+\operatorname{cst},\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq6.png) (2)

(2)

where ∇ = dln(T)/dln(P) is a power law index approximating the average temperature gradient of the atmosphere in the regions probed by the observations and cst is a place holder for a constant that is irrelevant to the problem. The derivation of this expression, a list of assumptions that go into obtaining it, and a discussion of the validity of these assumptions are presented in Appendix A. As long as the cloud is the dominant opacity source over the frequency range of interest, an approximated cloud opacity can be extracted, up to a scaling constant, from the measured brightness temperature.

In what follows, we use Eq. (2) to fit the opacities predicted for various silicate species to the observed brightness temperature. In practice, we assume that the silicate cloud resides in a cloudy column of the atmosphere, and add a correction to the brightness temperature to account for the emission of another atmospheric column with a constant brightness temperature. In the derivation this column is called “clear”, but its defining property is that its spectrum is featureless (i.e., at constant brightness temperature) across the 10 μm region. We treat ∇, the cloud column coverage f and the clear column photospheric temperature (again, see Appendix A for more details) as free parameters to extract ln(κ). This ln(κ) is then compared to predicted silicate cloud (scattering+absorption) opacities, assuming a log-normal particle size distribution (in principle, any distribution may be adopted). For this, the mean particle size and width of the distribution are free parameters. The maximum of the log-opacity of the resulting cloud description is scaled to the maximum of the log-opacity derived from the brightness temperature, with an additional scaling (additive term in log space) as a free parameter. We note that all free parameters are varied simultaneously during the fit. We then investigate which species best describes the 10 μm feature over a wavelength range from 8–12.5 μm, which we determined to be the range over which the silicate cloud is the dominant opacity contributor. The priors adopted for the free parameters are given in Table 1. The fits were run by estimating the posterior probability distribution of the free parameters, given the observed brightness temperatures. For this we used PyMultiNest (Buchner et al. 2014), which is a Python wrapper of MultiNest (Feroz & Hobson 2008; Feroz et al. 2009, 2019). For our runs we assumed 200 live points, and the standard parameter values of pymultinest.run(), that is evidence_tolerance = 0.5 and sampling_efficiency = 0.8. The error bars on the brightness temperature observations were derived from the flux uncertainties (see Section A.3). For the latter we used the error bar inflation from our best-fitting retrieval model (b = −8.589 at λ/Δλ = 400, see Section 3.2 for more information), adjusted to our fitting resolution λ/Δλ = 100.

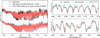

The ![$\[\chi_{\text {red }}^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq7.png) values for all considered silicate species are given in Table 2 (see Table B.1 for a list of references of the optical constants). The fits of the “top 14” species can be seen in Fig. 2 and fits of all remaining species are shown in Figure D.1. We find that the best-fit

values for all considered silicate species are given in Table 2 (see Table B.1 for a list of references of the optical constants). The fits of the “top 14” species can be seen in Fig. 2 and fits of all remaining species are shown in Figure D.1. We find that the best-fit ![$\[\chi_{\text {red }}^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq8.png) are smaller than one, which could indicate overfitting. We note, however, that the flux error bars we are using here have been scaled up, based on values found in the full retrievals (see Sect. 3.2), and may account for both underestimated uncertainties and retrieval model insufficiencies.

are smaller than one, which could indicate overfitting. We note, however, that the flux error bars we are using here have been scaled up, based on values found in the full retrievals (see Sect. 3.2), and may account for both underestimated uncertainties and retrieval model insufficiencies.

In addition to the nominal single-species fits described here, we also attempted to fit the silicate feature by combining two cloud species. For this we considered all Nc(Nc − 1)/2 = 276 possible combinations of species, where Nc = 24 is the number of Si-bearing cloud species in our database. To keep the number of free parameters low, we only added a relative weighting between the two species as an additional free parameter (κtot = κ1 + wκ2, with w going from 10−5 to 105 on a log-uniform prior). The mean particle size and width of the size distribution was therefore the same for both species. We robustly find that SiO is the species leading to the best fits: it is one of the two combined species in 21 out of the top 25 combinations, and also is present in the best combination. We find that adding an additional species can increase the fit quality, pushing ![$\[\chi_{\text {red }}^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq9.png) to values as low as 0.52, when compared to the single-species best-fit (also SiO) of 0.65. We refrained from a more detailed exploration with multiple species, because we considered the brightness temperature technique as a tool for finding likely cloud candidates for in-depth analyses via retrievals here. The underlying assumptions (see Appendix A) may be satisfactorily met for our intended purposes, but may not be good enough to replace an in-depth retrieval analysis over the full wavelength range, with proper radiative transfer. For crystalline silicate features, for which cloud species have more distinct appearances for different species, the multi-species approach may be worth revisiting.

to values as low as 0.52, when compared to the single-species best-fit (also SiO) of 0.65. We refrained from a more detailed exploration with multiple species, because we considered the brightness temperature technique as a tool for finding likely cloud candidates for in-depth analyses via retrievals here. The underlying assumptions (see Appendix A) may be satisfactorily met for our intended purposes, but may not be good enough to replace an in-depth retrieval analysis over the full wavelength range, with proper radiative transfer. For crystalline silicate features, for which cloud species have more distinct appearances for different species, the multi-species approach may be worth revisiting.

Priors adopted for the cloud feature fit.

Ranked list of cloud opacity fits using the brightness temperature method for the wavelength range of 8–12.5 μm.

3.1.2 Results of the brightness temperature analysis

The most likely cloud species, if taking the results of the brightness temperature method at face value, is the absorption of amorphous SiO. This is surprising, because SiO would oxidize to form SiO2 very quickly. If correct, this could mean that the SiO forms in a quite strongly O-depleted (relative to carbon) environment (Wetzel et al. 2013), or that we trace the formation of SiO nuclei that form the seeds for further cloud condensation (e.g., Gail et al. 2013) (this option is discussed further in Sect. 4.3.2, since we deem it a possible scenario). One may argue that while SiO fits the spectrum well over the narrow wavelength range considered here (8–12.5 μm), the required particle properties may lead to imperfect fits over the full JWST wavelength range. We thus progressed by using the brightness temperature method as a way to inform our decision on which condensate species should be tested in retrievals. However, as we describe in Section 3.2, the retrievals also point to SiO being the most likely species. We also note again that SiO was identified as a possible species in (Luna & Morley 2021; Suárez & Metchev 2023). The implications of this finding, if correct, are discussed in Sections 4.3.2 and 5. Lastly we note that even for the best-fitting species a residual wavelength-dependent structure is visible in the opacities inferred from brightness temperatures, from ~9.5–10 μm, see Fig. 2. Likewise, we discuss this in Section 4.3.2.

|

Fig. 2 Opacity fits of the 10 μm feature for the “top 14” silicate cloud species using the brightness temperature method. The remaining fits for the less well fitting species can be found in Fig. D.1. |

3.2 Retrievals

Armed with a ranked list of likely cloud species, we study how well we can reconstruct the spectrum of PSO J318through retrievals below, and how robustly we can constrain the underlying properties of the atmosphere. Particular focus is placed on the identity of the clouds causing the 10 μm feature. More specifically, we tested the top eight species identified with the brightness temperature method. In addition, we looked at three more species from further down in the list, resulting in 11 species with ![$\[\chi_{\text {red }}^{2}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq59.png) values from 0.65 to 4 in the brightness temperature method (these species are also marked with an asterisk in Table 2).

values from 0.65 to 4 in the brightness temperature method (these species are also marked with an asterisk in Table 2).

Retrievals generally aim to constrain the probability distribution of parameters thought to describe the atmosphere (e.g., temperature, composition, cloud properties) while leveraging any prior beliefs we have about the distribution of said parameters. A fairly recent review on retrievals can be found in Madhusudhan (2018). A number of retrieval codes exist now, many of them open source; we refer the reader to MacDonald & Batalha (2023)2 for an up-to-date list. In the work presented below we use petitRADTRANS (pRT, see Mollière et al. 2019, 2020; Blain et al. 2024); retrievals were run with pRT’s retrieval package described in Nasedkin et al. (2024).

3.2.1 Forward model description

The forward model is the function that returns flux predictions given a set of atmospheric input parameter values. A retrieval inverts the forward model and returns the parameter distribution, given an observation. The forward model is thus the central ingredient of any retrieval. We start by defining a single-column forward model which takes the atmospheric temperature, cloud and compositional structure as input parameters for calculating the flux emerging at the top of the atmosphere (including multiple scattering). A single-column model can also be used as a building block to approximate horizontal atmospheric heterogeneities. For this we assume that the atmosphere is well described by the flux predicted from a set of one-dimensional columns, weighted by the fractional area they occupy in the atmosphere. Below we assume at most two columns.

Atmospheric temperature structure. We described the atmospheric temperature structure using the approach reported in Zhang et al. (2023), that is, the power law dependence of the temperature with pressure dlnT/dlnP was retrieved at 10 points in the atmosphere (equidistantly spaced in log-pressure), and quadratically interpolated between these layers. The priors for the seven lowest (i.e., highest pressure) points were determined from constructing the distribution of dlnT/dlnP for the temperature profiles reported in Morley et al. (2024), as has been reported in Zhang et al. (2025). The corresponding 1-σ ranges of these distributions defined our Gaussian priors. In the three uppermost layers the power law index could vary freely (excluding inversions) because our pressure range extends to 10−6 bar, but the Morley et al. (2024) models end at 10−4 bar. The adopted priors for all retrieval parameters and the pressure coordinates of the 10 points are given in Table 3.

Temperature excursion. We additionally allow for the temperature profile to deviate from the above treatment. This is only used for some multi-column setups. Nominally, the columns share the same temperature profile, but when applying the excursion treatment the temperature structure of a given column is allowed to deviate. The temperature excursion is defined by multiplying the nominal dlnT/dlnP structure by

![$\[1+f_{\mathrm{exc}}\left(1-\frac{2|\log _{10}(P)-\log _{10}(P_{\mathrm{exc}})|}{\Delta \log _{10}(P_{\mathrm{exc}})}\right),\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq60.png) (3)

(3)

for all |log10(P/Pexc)| ≤ Δlog10(Pexc)/2. The prior for fexc is chosen such that the resulting behavior of the excursion spans from P-T curves exhibiting (weak) inversions to curves with strong boosts of the dlnT/dlnP gradient. Also, log10(Pexc) and Δlog10(Pexc) are free parameters.

Chemical composition. We determined the chemical composition by prescribing chemical equilibrium for all absorber species we expect to play a minor role. For this we retrieved the atmospheric metallicity, [M/H], and C/O, where the latter was changed by scaling the oxygen abundance after all metals have been scaled by 10[M/H]. The composition is obtained by interpolating in the chemical equilibrium table that is part of pRT, which itself has been prepared with easyCHEM (Lei & Mollière 2024)3. No rainout is included in these calculations, while it is implicitly taken into account for some species by limiting the selection of condensates. For example, feldspars such as orthoclase are not included in our chemical calculations, with the goal of preventing a sequestration of alkalis into these species at the temperatures of L/T transition objects – which is not observed (Line et al. 2017; Zalesky et al. 2019). Since we wanted to treat the major absorbing species more flexibly, we retrieved the mass fractions of 12CO, 13CO, CO2, CH4, CrH and H2O independently, assuming them to be vertically constant. CrH was retrieved independently because it is not included in the precomputed equilibrium table of pRT. The retrieved metallicity and C/O values reported in Table 6 are obtained from considering all metal gas phase abundances, irrespective of whether they were obtained from the chemical interpolation or retrieved independently.

Gas opacity sources. We included the following line opacities in our analysis: CH4 (Hargreaves et al. 2020), 12CO (Rothman et al. 2010), 13CO (Rothman et al. 2010), CO2 (Yurchenko et al. 2020), CrH (Burrows et al. 2002), FeH (Wende et al. 2010), HCN (Barber et al. 2013), H2O (Polyansky et al. 2018), H2S (Azzam et al. 2016), K (line profiles by N. Allard, see Mollière et al. 2019), Na (Allard et al. 2019), NH3 (Coles et al. 2019), PH3 (Sousa-Silva et al. 2014), SiO (Yurchenko et al. 2021), TiO (McKemmish et al. 2019). Where available, correlated-k opacities in the pRT format were taken from the ExoMolOP database (Chubb et al. 2021) or computed with the method described in Mollière et al. (2015) otherwise. Rebinning to lower resolution opacities was done using Exo_k (Leconte 2021).

Clouds. The parameterized behavior of the clouds is motivated by the semi-analytical model presented in Ackerman & Marley (2001), but is more flexible. For any given cloud species we freely retrieve the position of the cloud base, Pi,base. The cloud mass fraction at the cloud base Xi,base, where i stands for a cloud species like MgSiO3, is found by scaling the elemental mass budget by a free parameter 10si. The elemental mass budget is determined by locking all elemental building blocks into the condensate in question, until the first species is depleted (e.g., for MgSiO3 the limiting element is Si, when considering scaled solar composition). The cloud mass fraction in the atmosphere is then Xi(P) = Xi,base(P/Pi,base)fsed,i for P ≤ Pi,base and 0 for P > Pi,base. The power law index fsed is likewise a free parameter. The particle size distribution is assumed to be log-normal, as defined in Ackerman & Marley (2001), with the mean particle size a and the width σ as free parameters in our standard approach. We set the prior for σ up in the same way as in the brightness temperature fitting, see Section 3.1.

Evolutionary priors. Despite excellent data, we noticed the tendency of our retrievals to approach unphysical values for bulk parameters (e.g., log(g) → 3 and lower, depending on the prior range). We therefore decided to prescribe priors on the radius and log(g), using the values derived in Zhang et al. (2020). For these values the authors assumed an age for PSO J318 consistent with the β Pic moving group (24 ± 3 Myr), used PSO J318’s inferred bolometric luminosity, and the cooling curves by Saumon & Marley (2008). Alternatively we adopted free priors on the radius and gravity to explore their effect on our best-fitting model.

Column coverage. Our forward model is set up in such a way that it can handle multiple 1D columns, with the total flux being

![$\[F=\sum_{i=1}^{N_{\text {column }}} b_i F_i,\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq64.png) (4)

(4)

where Fi is the top-of-atmosphere flux of column i, and bi ≥ 0 is its weight, respectively. In principle, the different columns may be fully independent, but in practice they share most of their parameters and only the cloud parameters are varied on a percolumn basis, for example. Because the retrievals presented here assumed at most two columns we defined b1 = B, b2 = 1 − B, B ≤ 1. Since the various data sets we considered were taken at different epochs, we retrieved three different values, BHST, BSpeX, and BJWST, which are thought to express different average climate states at the respective times of observation with the three observatories. That is, if ![$\[\tilde{B}(t)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq65.png) is the actual time-dependent change due to rotation of the object, then B is the time average of

is the actual time-dependent change due to rotation of the object, then B is the time average of ![$\[\tilde{B}(t)\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq66.png) during the observation. We neglect that the JWST observations with the NIRSpec PRISM, G395H, and MIRI MRS instruments were taken sequentially and thus recorded time-averaged fluxes from different rotational phase intervals.

during the observation. We neglect that the JWST observations with the NIRSpec PRISM, G395H, and MIRI MRS instruments were taken sequentially and thus recorded time-averaged fluxes from different rotational phase intervals.

Uncertainty scaling. the flux uncertainties of individual instruments were scaled by setting σscaled.(λ) = [σ2(λ) + 10b]1/2, where σ is the reported flux uncertainty of the observation. This treatment allows for the correction of underestimated uncertainties or shortcomings in the model that would lead to systematic biases. It serves to give a more conservative estimate of the parameter distribution width, as it widens the posteriors (Line et al. 2015). The b values were retrieved on a per-data-set basis, where G395H’s NRS 1 and NRS 2 detectors were treated separately, because we binned NRS 1 to λ/Δλ = 400 and NRS 2 to λ/Δλ = 1000 during the retrievals. The priors for the b values were taken from Line et al. (2015).

Retrieval priors adopted for the single-column forward model.

3.2.2 Retrieval runs

We tested a number of different forward model setups in which the atmosphere was approximated by two columns. For example, we let the temperature structure vary between the columns, or the free parameters associated with the cloud, or the parameters associated with the chemical composition, or mixtures of these setups. The motivation for these options are the various processes (cloud cover, temperature, compositional variations) that have been suggested as drivers for atmospheric variability (see, e.g., Radigan et al. 2014; Robinson & Marley 2014; Tremblin et al. 2020). For studying whether we can constrain the most likely cloud species with retrievals we finally adopted a model in which both columns shared most of their properties: P-T structure, gas phase abundances, and the parameters describing the iron cloud. A global iron cloud (in the lower atmosphere) is a common finding in retrieval studies (Burningham et al. 2021; Vos et al. 2023). Then, for Column 1, a silicate cloud with its associated parameters was retrieved, while for Column 2 the silicate cloud was neglected (by setting ssilicate = −50), motivated by the patchy silicate cloud findings of, for example, Apai et al. (2013); Vos et al. (2023); Zhang et al. (2025). We thus stress that “patchy silicate clouds” does not mean that the atmosphere is described by a cloudy and a cloud-free column, since the iron cloud is present in both columns. The two Columns 1 and 2 also retrieved separate Δlogσ, allowing for different widths of the particle size distributions between Columns 1 and 2. Results obtained with retrieval models that differ from our standard setup, for example assuming a single-column atmosphere, or keeping the cloud parameters fixed in both columns and varying the temperature structure instead, or turning off the evolutionary prior, are listed in Table 6 and discussed in Section 4.3.

We note that among all our explored two-column setups, the fiducial model definition described above consistently fit the data with the least bias upon visual inspection, resulted in the smallest required error bar scalings (i.e., the smallest b-factors), and formally converged in retrievals most reliably. The best-practice approach would be to carry out model selection via a Bayes factor analysis, but with our 40+ free parameters, wide wavelength coverage, and high S/N-data, MultiNest starts to break down (also see Buchner 2023; Himes 2022; Dittmann 2024, for a discussion of how nested sampling can fail). For example, we found that models with too many free parameters failed to converge, or observed that widening the prior ranges (when turning off the evolutionary priors for log10(g) and R) resulted in worse fits for a given model. Given the fact that we are in a high-dimensional parameter space (with signs of the sampler missing the global likelihood maximum, also see Himes 2022), and given that we must run MultiNest in constant sampling efficiency to enable convergence (which can lead to over-confident posteriors, see Chubb & Min 2022), we refrain from carrying out MultiNest-based Bayes factor analyses; we cannot guarantee that the posterior sampling leads to a reliable integration for the evidence Z. This observation and its implications for the use of nested sampling in the era of JWST (and ELT in the future) are discussed in Section 5.

In practice, we set up MultiNest with 3000 live points, using const_efficiency_mode=True, sampling_efficiency = 0.05 and evidence_tolerance set to 0.5. While MultiNest results must be approached cautiously for the reasons stated above, it is the nested sampling algorithm that converges most efficiently (Himes 2022) and enables us to run retrievals for this study in the first place. To speed up the retrievals further we binned the MIRI MRS data to pRT’s wavelengths for a λ/Δλ = 400 wavelength spacing, exactly. The same was done for NIRSpec G395H NRS1. For NRS2 we used the spacing of pRT wavelength tables at λ/Δλ = 1000, to retain sensitivity to secondary CO isotopologues. For HST, SpeX and JWST NIRSpec PRISM the models were calculated at λ/Δλ = 300 (HST) and 140 (SpeX and NIRSpec PRISM) before being convolved to R = 130 (HST), 75 (SpeX) and 65 (NIRSpec PRISM) and then binned to the data’s respective wavelength spacing. Retrievals were run on the Viper cluster of the Max Planck Computing & Data Facility (MPCDF), each requiring on the order of 105 core hours to finish on AMD EPYC Genoa 9554 CPUs; each retrieval ran for about a week on 1000 cores.

3.2.3 Retrieval results

Figure 3 shows the best-fitting spectra of the two-column retrieval models. Panel a shows our “winning model”, that is, the model with the lowest Bayesion information criterion (BIC; see discussion below); an atmosphere with a global iron cloud; and a patchy SiO cloud with amorphous spherical particles, plotted on top of the JWST observations. Residuals (Panel b) are mostly flat but exhibit systematic behavior at some locations, for example in the water band at 6.6 μm. In panels c–m, we show retrievals with all tested cloud candidate species, zoomed in on the silicate feature. In these zoomed-in views it can be seen that the predicted line depth appears to be shallower than the data from 7–8 μm for some of the models. In general, the winning model retrieval finds that the flux of PSO J318is significantly reddened by clouds, since neglecting the cloud opacity for the best-fit model leads to a dramatic increase of flux in the NIR. What is more, the flux separates into a column component that is very red and blackbody-like, and one that retains molecular features much more strongly, similar to the results presented for 2M1207b in Zhang et al. (2025).

Evidence values from nested sampling cannot be used in the selection of the most likely model from our set of tested models, but we still wanted to tentatively vet the retrievals with different cloud species for fit quality (assuming that the global log-likelihood maximum, or a maximum of similar quality to the global maximum, was identified). For this, we made use of the BIC, BIC = Nparamln(Nλ) − 2ln(Lmax), which allows for model selection. Here, Nparam is the number of free parameters of the model, Nλ is the number of wavelength points in the spectrum, and ![$\[\text{ln} L_{\text {max}}=-0.5 {\sum}_{i=1}^{N_{\lambda}}\{(f_{i}-m_{i}^{\text {best}})^{2} /(\sigma_{i}^{2}+10^{b})+\ln [2 \pi(\sigma_{i}^{2}+ 10^{b})]\}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq67.png) is the best-fit log-likelihood, where

is the best-fit log-likelihood, where ![$\[f_{i}, m_{i}^{\text {best}}\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq68.png) and σi are the observed flux, best-fit model, and observational uncertainties at Nλ wavelengths λi, respectively, and b is the error bar scaling parameter. The BIC makes the underlying assumption that posteriors are multivariate Gaussians. This is not necessarily the case, but tends to be better satisfied in high S/N regimes, over which the retrieval model can be better linearized over the width of the posteriors. Yet, this is a limitation that needs to be kept in mind, especially if a posterior exhibits parameter correlations over wide value ranges, or is multi-modal. We note that from visual inspection, most of our retrieved parameters are tightly constrained, with mono-modal posteriors. If the a-priori probability for a given model is unknown (i.e., all models are considered to be equally likely before being applied to the data), then the probability ratio of two models ℳ1 and ℳ2, given the data vector f, P(ℳ1∣f)/P(ℳ2∣f), is given by the Bayes factor B12 = Z1/Z2. Z is the evidence here, which is typically returned by nested sampling. For a posterior with a shape described by a multivariate Gaussian one can write Z = exp(−BIC/2) (Raftery 1995). Since the models that test different silicate cloud species have the same number of free parameters and wavelength points, it then holds that

and σi are the observed flux, best-fit model, and observational uncertainties at Nλ wavelengths λi, respectively, and b is the error bar scaling parameter. The BIC makes the underlying assumption that posteriors are multivariate Gaussians. This is not necessarily the case, but tends to be better satisfied in high S/N regimes, over which the retrieval model can be better linearized over the width of the posteriors. Yet, this is a limitation that needs to be kept in mind, especially if a posterior exhibits parameter correlations over wide value ranges, or is multi-modal. We note that from visual inspection, most of our retrieved parameters are tightly constrained, with mono-modal posteriors. If the a-priori probability for a given model is unknown (i.e., all models are considered to be equally likely before being applied to the data), then the probability ratio of two models ℳ1 and ℳ2, given the data vector f, P(ℳ1∣f)/P(ℳ2∣f), is given by the Bayes factor B12 = Z1/Z2. Z is the evidence here, which is typically returned by nested sampling. For a posterior with a shape described by a multivariate Gaussian one can write Z = exp(−BIC/2) (Raftery 1995). Since the models that test different silicate cloud species have the same number of free parameters and wavelength points, it then holds that

![$\[\text{ln} B_{12} \approx \frac{1}{2}\left(\chi_2^2-\chi_1^2\right)+\frac{1}{2} \sum_{i=1}^{N_\lambda} \ln \frac{\sigma_i^2+10^{b_2}}{\sigma_i^2+10^{b_1}},\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq69.png) (5)

(5)

where ![$\[\chi^{2}={\sum}_{i=1}^{N_{\lambda}}(f_{i}-m_{i}^{\text {best }})^{2} /(\sigma_{i}^{2}+10^{b})\]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa55732-25/aa55732-25-eq70.png) . We note that our error bar scaling via 10b causes a χ2 → Nλ convergence in retrievals (Line et al. 2015), unless b priors are hit, which we observe for the worst cloud candidates. However, the above expression takes this into account: in a situation where all χ would indeed be identical, the model with the least upscaled error bars would win. Given a Bayes factor between a given model and the one with the highest evidence, it is customary to calculate a rejection significance using the formalism described in Benneke & Seager (2013). However, Kipping & Benneke (2025) recently argued that this is misleading, since the so-derived significance values are upper limits only. We thus refrain from a significance conversion and simply report Bayes factors.

. We note that our error bar scaling via 10b causes a χ2 → Nλ convergence in retrievals (Line et al. 2015), unless b priors are hit, which we observe for the worst cloud candidates. However, the above expression takes this into account: in a situation where all χ would indeed be identical, the model with the least upscaled error bars would win. Given a Bayes factor between a given model and the one with the highest evidence, it is customary to calculate a rejection significance using the formalism described in Benneke & Seager (2013). However, Kipping & Benneke (2025) recently argued that this is misleading, since the so-derived significance values are upper limits only. We thus refrain from a significance conversion and simply report Bayes factors.

Panels c-m of Fig. 3 shows the best-fit models of all tested silicate species on top of the data, zoomed in on the 10 μm region. In agreement with the brightness temperature method, the winning silicate species of the two-column retrievals is amorphous SiO in the form of spherical particles. The panels also list the rejection Bayes factor of the respective cloud species, when compared to the winning SiO model. This Bayes factor was calculated using the best-fit log-likelihood from the full wavelength range (1–18 μm). After irregularly shaped amorphous SiO, the next most likely cloud consists of irregularly shaped glassy (thus amorphous) MgSiO3 particles, followed by crystalline spherical MgSiO3 particles. We note that crystalline MgSiO3 appears unlikely, given the smoothness of the 10 μm feature visible in the data. Indeed, any amorphous material with pyroxene-type (Mg1−xSixO3) stoichiometry appears to be fitting the data better across the 10 μm region plotted in panels c–m, but we note again that the rejection Bayes factors are calculated over the full wavelength range. The best fit spectra of all tested retrieval models, over the full wavelength range from 1–18 μm, are shown in Fig. C.1.

We list the ΔBIC and corresponding rejection Bayes factors of less favored cloud species in Table 4. In comparison, the Bayes factors returned by MultiNest did not lead to believable results. For example, the BIC-based values indicate that spherical SiO is clearly favored over irregularly shaped SiO (log10(B) = 12.28). In contrast, the corresponding Bayes factor from MultiNest results in a numerical overflow.

It is worth noting that the second most likely species identified by the retrievals is glassy amorphous MgSiO3. MgSiO3 is potentially expected to form in a PSO J318-like atmosphere, while the presence of SiO is surprising (Calamari et al. 2024, but also note Luna & Morley 2021; Suárez & Metchev 2023). As can be seen in panels e and g in Fig. 3, glassy MgSiO3 in spherical or irregular form actually leads to a good fit across the 10 μm range, albeit worse than the still favored SiO. In addition, both glassy MgSiO3 clouds lead to a too strong flux decrease in the predicted 4 μm flux peak of PSO J318 (see Fig. C.1), such that in total glassy MgSiO3 is disfavored with log10(B) = 32.18 and log10(B) = 42.81 respectively, when compared to SiO (see Table 4).

Comparing the ranked lists of likely cloud species in Tables 2 and 4, we conclude that the brightness temperature method can be a useful pointer for the most likely silicate absorbers affecting a spectrum. More specifically, the best and worst species in both lists agree, while there is some reordering present for the species in between (we note that only 11 of the 24 silicate species were tested in full retrievals due to the significant numerical cost). The brightness temperature method therefore must not be trusted blindly, but appears to lead to reasonably accurate predictions for PSO J318.

It is interesting that both the brightness temperature method and the retrievals come to the conclusion that the winning species is SiO. Making this assertion based on the shape of the amorphous 10 μm feature may still appear to be risky. But we note that the high altitude of the silicate cloud deck and the small particle sizes we retrieved, similar to the results presented in Luna & Morley (2021), also point to SiO, which we discuss in Section 4.3.2. The implication of this likely SiO detection is also further discussed in Section 5.

|

Fig. 3 Model fits of PSO J318 obtained with our fiducial two-column retrieval setup, considering different types of silicate clouds. Panel a shows the best-fit spectrum of the overall winning model (black solid line) plotted on top of the JWST data (gray circles, with 10b error scaling). The winning model assumes amorphous spherical SiO particles. The flux contribution of the two individual columns is also shown, at their best-fit relative scaling (salmon and rose colored lines, respectively). The light blue line shows the result of recalculating the best-fit model, but turning off the cloud opacities. Panel b shows the residuals between the best-fit model and the data (with 10b error scaling). Panel c is a version of Panel a that zooms in on the silicate feature, but the best-fit model is shown in pink instead. Panels d–m show the same zoomed-in view of the silicate feature but for the other tested silicate feature candidates. Panel n shows the residuals between model and data for the various silicate cloud species using the same colors as in panels c–m. |

Ranked list of likely cloud species obtained from full retrievals.

4 Bulk and atmospheric properties of PSO J318

In addition to constraining the identity of PSO J318’s silicate cloud species, its spectrum should also allow us to constrain bulk and atmospheric properties of the object. An established way to judge the accuracy of such constraints is to compare results obtained with retrievals to those obtained from interpolating in so-called self-consistent model grids. Such models determine the atmospheric structure by assuming radiative-convective equilibrium, coupled to chemical schemes that determine the atmospheric composition for a given atmospheric temperature structure and elemental abundances (e.g., Marley & Robinson 2015; Hubeny 2017). For the comparison below, we derived posterior distributions of the self-consistent model parameters with PyMultiNest, using interpolated model grid spectra as the forward model. This analysis was carried out with species4 (Stolker et al. 2020).

4.1 Radiative-convective equilibrium models

Self-consistent models have far fewer free parameters than retrievals, because they implement atmospheric physics to determine the atmospheric state to a much greater degree. A common free parameter is the composition. It is usually expressed through atmospheric metallicity [M/H] and through C/O. Other free parameters are the atmospheric gravity log10(g), the planetary effective temperature Teff, and parameters that describe the setup of the atmospheric clouds and departures from chemical equilibrium. In the following we describe the parameter grids we consider for our study. These are identical to the grids recently used in the Early Release Science (ERS) team’s paper on VHS 1256b, an object similar to PSO J318 (Petrus et al. 2024). A table of the free parameters, the explored parameter range, grid spacing and fit results is given in Table 5.

Exo-REM (Baudino et al. 2015; Charnay et al. 2018; Blain et al. 2021) solves for the atmospheric structure in radiative-convective equilibrium and implements chemical disequilibrium using the quench approximation (Zahnle & Marley 2014). Clouds are described following a combination of the time scale approach of Rossow (1978) with the Ackerman & Marley (2001) approach. The atmospheric mixing strength needed for the cloud and chemical composition models is determined from mixing length theory in the convective regions, and from assuming a convective overshoot decay in the radiative regions above. Among other species (Na2S, KCl, Fe) Exo-REM considers spherical amorphous Mg2SiO4 clouds, adopting the optical constants from Jäger et al. (2003b).

ATMO (Tremblin et al. 2015) likewise models the atmosphere in radiative-convective equilibrium, and implements disequilibrium chemistry for the reactions controlling the CH4-CO and NH3-N2 conversions. For this the vertical eddy diffusion coefficients is varied as Kzz = 105+2(5−log10g) cm2 s−1. ATMO models are cloud-free, such that the reddening of the spectra, often considered to be caused by clouds, is achieved through a decrease of the adiabatic index γ between 2 × 10log10(g)−5 and 500 × 10log10(g)−5 bar. This leads to an earlier (lower pressure) onset of convection, and convective regions with a shallower dependence of temperature on pressure, since (dlnT/dlnP)ad = (γ − 1)/γ. This reddens the spectra – which is very similar to the expected effect of clouds; instead of a cloud hiding the hot lower altitudes of the atmosphere, the lower altitudes are simply less hot with ATMO’s modified γ treatment. The decrease of γ, when compared to classical dry convection, can occur for multiple reasons, such as due to a conversion to a higher mean molecular weight atmosphere at high altitudes (e.g., increase in CH4 and NH3) or due to the release of latent heat if there is a condensible species in the atmosphere (moist convection). More details on the occurrence of diabatic convection in H2/He dominated atmospheres near the L-T transition can be found in Tremblin et al. (2015, 2016, 2017, 2019), where it is introduced as the process that drives that transition.

Sonora Diamond-back (Morley et al. 2024) determines the atmospheric structure in radiative-convective and chemical equilibrium. In addition, it implements the cloud modeling approach of Ackerman & Marley (2001). The required atmospheric mixing for the cloud model is determined from a mixing length and convective overshoot description, see Morley et al. (2024) for more details. The following amorphous high-temperature cloud species are considered: MgSiO3 (Dorschner et al. 1995), Mg2SiO4 (Jäger et al. 2003b), as well as Fe (Palik 1985; Kitzmann & Heng 2018) and Al2O3 (Koike et al. 1995). In addition to the vertical mixing strength Kzz, Sonora Diamondback controls the cloud properties through the fsed parameter (Ackerman & Marley 2001), which is defined as the mass-averaged ratio between the particles’ settling and mixing velocities. At a given Kzz, fsed controls both the mean particle size and vertical extent of the cloud. We note that the pRT’s forward model setup conceptually borrows from this description, defining its cloud mass fraction profile as ∝ Pfsed, while retrieving the cloud particle size freely; this is related, but not identical, to the Sonora Diamondback approach.

Properties of the parameter grids explored for the selfconsistent grid retrievals of the PSO J318 data.

4.2 Results in comparison to free retrievals