| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A219 | |

| Number of page(s) | 29 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554874 | |

| Published online | 12 December 2025 | |

Populations of evolved massive binary stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud

II. Predictions from rapid binary evolution

1

Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany

2

Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany

3

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

4

Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

5

Département d’Astronomie, Université de Genève, Chemin Pegasi 51, CH-1290 Versoix, Switzerland

6

Gravitational Wave Science Center (GWSC), Université de Genève, 24 Quai E. Ansermet, CH-1211 Geneva, Switzerland

7

Institute of Astrophysics, Foundation for Research & Technology Hellas (FORTH), GR-70013 Heraklion, Greece

8

Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Gießenbachstraße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

9

Tel Aviv University, The School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel

10

Department of Materials and Production, Aalborg University, Fibigerstræde 16, 9220 Aalborg, Denmark

11

School of Astronomy and Space Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, People’s Republic of China

12

Key Laboratory of Modern Astronomy and Astrophysics, Nanjing University, Ministry of Education, Nanjing 210023, People’s Republic of China

13

Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

★ Corresponding authors: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

30

March

2025

Accepted:

14

August

2025

Context. Massive star evolution plays a crucial role in astrophysics; however, its study is subject to large uncertainties. This problem becomes more severe by the majority of massive stars being born in close binary systems, whose evolution is affected by interactions among their components.

Aims. We want to constrain major uncertainties in massive binary star evolution, particularly with respect to the efficiency and the stability of the first mass-transfer phase.

Methods. We used the rapid population synthesis code COMBINE to generate synthetic populations of post-interaction binaries, assuming constant mass-transfer efficiency. We employed a new merger criterion that adjusts self-consistently to any prescribed mass-transfer efficiency. We tailored our synthetic populations to be comparable to the expected binary populations in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC).

Results. We find that the observed populations of evolved massive binaries cannot be reproduced with a single mass-transfer efficiency. Instead, a rather high efficiency (≳50%) is needed to reproduce the number of Be stars and Be/X-ray (BeXB) binaries in the SMC, while a low efficiency (∼10%) leads to a better agreement with the observed number of Wolf-Rayet (WR) stars. We constructed a corresponding mass-dependent mass-transfer efficiency recipe to produce our fiducial synthetic SMC post-interaction binary population. It reproduces the observed number and properties of the BeXBs and WR binaries rather well; furthermore, it is not in stark disagreement with the observed OBe star population. It predicts around 170 massive stars with neutron star companion, of which 140 are Be stars, and about 170 systems disrupted by the supernova, of which 150 are Be stars. Overall, 20% of all post-interaction systems contain a helium star. It also predicts two large, as-yet-unobserved populations of OB + BH binaries: about 100 OB + BH systems with rather small orbital periods (≲20 d) and around 40 longer period OBe + BH systems.

Conclusions. Continued searches for massive binary systems will strongly advance our understanding of their evolution.

Key words: stars: black holes / stars: emission-line, Be / stars: massive / stars: neutron / Magellanic Clouds / X-rays: binaries

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Massive stars are powerful cosmic engines. They produce spectacular events such as supernovae (SNe) and gamma-ray bursts, drive the chemical evolution of galaxies (Timmes et al. 1995) and shape their interstellar medium (Hopkins et al. 2014). Massive stars are preferentially born in close binary systems (Sana et al. 2012), which produce X-ray binaries and gravitational wave mergers (Tauris & van den Heuvel 2006, 2023). However, our understanding of their evolution is far from complete (Langer 2012, 2024).

The different types of massive binaries can be ordered in a simplified evolution scheme (e.g. Tauris & van den Heuvel 2006) from zero-age main-sequence (ZAMS) binaries up to compact object mergers (Fig. 1). However, the vast majority of massive binary stars will exit the evolutionary path, either by breaking up as a consequence of core collapse (Tauris & Takens 1998) or by merging into a single object due to the interaction between the two stellar components (Podsiadlowski et al. 1992; Langer 2012; de Mink et al. 2014). A critical step in this evolutionary scheme is the Roche-lobe overflow (RLO), where matter is transferred from one star (donor) to the other (accretor) (Kippenhahn & Weigert 1967). In the first RLO, it is usually the heavier star that is the donor as it burns its fuel faster and expands first. This process can either take place during its main-sequence phase (Case A) or during shell burning (Case B; Kippenhahn & Weigert 1967). The physics of the RLO is not well understood, especially with respect to the conditions that determine whether we are dealing with a case of donor stripping or a merger (Ivanova et al. 2013), what fraction of material lost by the donor is deposited on the accretor (de Mink et al. 2007), and how much angular momentum the ejected material removes from the system (Marchant & Bodensteiner 2024).

|

Fig. 1. Schematic evolutionary path from ZAMS to gravitational wave merger, adapted from Kruckow et al. (2018). We focus on the BH + OBe phase. |

Stable mass transfer is expected to lead to an almost complete removal of the hydrogen-rich envelope of the donor. While this stripped star may retain a thin hydrogen layer (Gilkis et al. 2019; Laplace et al. 2020) or may only partially strip (Ercolino et al. 2024), it is commonly referred to as a helium star (HeS). The accretor receives mass, which may rejuvenate the star (Braun & Langer 1995), and gains spin angular momentum. Packet (1981) showed that only a small amount of accreted material is enough to bring the accretor to rotate close to critical rotation.

Rotating near critical rotation, such a star expels matter from its surface, forming a decretion disk around its equator. This disk causes broad emission lines to appear in the spectrum. These lines, along with the rotationally broadened absorption lines of the star serve as an explanation for the Be star phenomenon (Porter & Rivinius 2003; Rivinius et al. 2013). It is, however, possible that either the mass loss (and thus angular momentum loss) or tidal forces brake stellar rotation; alternatively, strong stellar winds could remove the disk so that the OBe star becomes a usual OB star again. On the other hand, it could be the case that the HeS expands so much that it initiates a second mass transfer (Case BB/BC; Tauris et al. 2015). The HeS terminates its life shortly after and becomes a stellar remnant (SR), namely a white dwarf (WD), neutron star (NS), or a black hole (BH). The following phase (OB + SR) is the focus of this work, as it is the second best observable one, since it features a long-living main-sequence star and an inert SR.

This formation channel of OBe stars by binary interaction is supported by the fact that no OBe stars with main-sequence companions have been observed (Bodensteiner et al. 2020) and, on the other hand, OBe stars with hot subdwarf (sdOB; the observational counterpart to light HeSs; Wang et al. 2021), WD (Zhu et al. 2023), and NS (Coe & Kirk 2015) companions are well known. However, only a few Be + sdOB and Be + WD systems have been discovered since the light and faint companion is hard to detect (Coe et al. 2020; Kennea et al. 2021; Gaudin et al. 2024; Marino et al. 2025). However, they can be very X-ray bright (Eddington luminosity) when they show nova-like outbursts. Several of these systems have been discovered recently (Marino et al. 2025, and references therein). Be + NS systems often appear as BeXBs as the NS accretes material from the disk and releases X-ray emission. Another proposed formation process of OBe stars is single-star evolution, which was recently studied by Ekström et al. (2008) and Hastings et al. (2020).

The success of this picture gives rise to questions around configurations that have not yet been observed. In particular, as many massive stars with NS companions are known, we would assume that OBe star systems with BH companions exist as well. Today, only one system of that kind has been proposed (MWC 656; Casares et al. 2014), but its nature was recently disputed by two independent studies (Rivinius et al. 2024; Janssens et al. 2023). On the other hand, three super-giant/X-ray binaries with BHs (Cyg X-1, LMC X-1, and M33 X-7) are well observed (Orosz et al. 2007, 2009, 2011; Miller-Jones et al. 2021; Ramachandran et al. 2022) and even one source with an X-ray quiet BH is known (VFTS 243, Shenar et al. 2022a). Therefore, an objective of this study is to answer whether it is possible to form OBe + BH systems and to predict their properties. After the OBe + SR phase, the system can evolve through a common envelope ejection to a binary SR, which may undergo a gravitational wave merger (Fig. 1). Thus, the OB + SR phase is an important intermediate step in understanding binary stellar evolution as a whole.

In this study, we focus on stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC). As a low-metallicity satellite galaxy of the Milky Way, it is a distinctive environment. Its metallicity of about one-fifth of the solar value (Venn 1999; Korn et al. 2000; Hunter et al. 2008) corresponds to the average metallicity of a redshift of about 3 (Kewley & Kobulnicky 2007). Low metallicities are interesting, as the aforementioned events (SNe, gamma-ray bursts, and gravitational waves) originate predominately in low metallicity environments (Abbott et al. 2019, 2023); thus, they have been recently studied extensively (e.g. Ge et al. 2023, and references therein). Being located at a distance of about 60 kpc, observing individual stars is still possible, as currently carried out by the ‘Binarity at LOw Metallicity’ (BLOeM) campaign (Shenar et al. 2024), which should yield robust constraints on many of the predictions presented in this work. Another advantage of SMC is the weaker stellar winds caused by low metallicity (Abbott 1982; Kudritzki et al. 1987; Mokiem et al. 2007). Lower winds imply a lower loss of angular momentum and, thus, we expect OBe stars to be more numerous and exhibit higher masses as well as, hence, a higher success rate in finding OBe + BH systems.

This study is closely related to Xu et al. (2025, hereafter Paper I), who investigated the same types of objects using detailed stellar models, whereas we used rapid binary evolution, which requires significantly fewer computational resources. This gives us the opportunity to investigate an alternative approach to treating the RLO phase that involves conducting a comprehensive study of the unconstrained parameters. Our work is structured as follows. Sect. 2 describes our methods to simulate systems consisting of a hydrogen-burning star with an SR. In Sect. 3, we describe how the outcome of binary evolution code depends on the initial parameters of the binary. In Sect. 4, we use different physical assumptions to generate artificial populations and compare them to observational characteristics to determine a fiducial set of assumptions. The population based on these assumptions is analysed in detail in Sect. 5. In Sect. 6, we compare our results to observations and previous work. A summary of our conclusions is given in Sect. 7.

2. Method

We investigated the OB + SR population of the SMC with the Monte Carlo based rapid binary population synthesis code COMBINE, which was first introduced by Kruckow et al. (2018). In this section, we describe how this code operates and how we adjusted it for this study.

2.1. The rapid binary population synthesis code COMBINE

Evolving both binary components simultaneously, COMBINE is based on tabulated detailed single-star models, in contrast to other binary population synthesis codes, which treat stellar evolution using fitting formulae. This allows for a fast exchange and modular use of the underlying stellar models. Compared to detailed codes such as MESA (Paxton et al. 2019, and references therein), COMBINE is much faster and enables the user to generate large model populations of different underlying binary physics in a small amount of time. Also, in contrast to MESA, it follows a system’s evolution through a SN event and it is able to treat a common envelope phase; also, in contrast to other rapid binary population synthesis codes, it uses envelope binding energies calculated self consistently from stellar models (Kruckow et al. 2016), rather than constant values of the envelope’s binding energy or mixing results of different 1D stellar evolution codes.

The dense grid of detailed stellar models is currently available for Milky Way, Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), SMC, and I Zwicky 18 metallicity, featuring both hydrogen-rich and HeS models. The models were calculated with BEC (Yoon et al. 2010, and references therein) using the same stellar physics as Brott et al. (2011) with initial masses from 0.5 to 100 M⊙. For the application in COMBINE, the following quantities were extracted and tabulated: total stellar mass, age, photospheric radius, core mass (see Sect. 2.2 for the updated definition), luminosity, effective temperature, two versions of the λ-parameter describing the binding energy of the envelope, and (new to this version of COMBINE, see Sect. 2.2) the carbon core mass and the moment of inertia factor. For hydrogen-rich models, the time of central hydrogen exhaustion is saved, too. Using initial mass and age as independent quantities, the current values of the remaining eight dependent quantities are interpolated linearly. The same HeS tracks are used for all metallicities, but their masses were rescaled by the wind mass loss rate, according to Hainich et al. (2015). While we are aware that detailed stellar models predict a small hydrogen layer to remain on the HeS and that the size of this layer has a large impact on the stellar radius (Laplace et al. 2020), we neglected it for simplicity.

To initialise a binary star model, COMBINE draws the initial primary mass M1 from an initial mass function (IMF). We used a Kroupa-like function, expressed as

with a high mass slope of α = 2.3 (Salpeter 1955; Massey et al. 1995) within the range of 3–100 M⊙. The lower limit ensures that we consider all relevant stars to meaningfully compare the companions of NS to stars of similar mass and the upper limit is the mass of the most massive stellar model we have. The mass of the secondary is derived from a mass ratio distribution,

and the initial separation from an orbital period distribution,

To model the binary star population in the SMC, we relied on four sets of observationally inferred values of κ and π: Sana et al. (2012), based on Galactic O-type stars (κ = −0.1, π = −0.55); Sana et al. (2013), based on LMC O-type stars (κ = −1.0, π = −0.45); Dunstall et al. (2015), based on LMC early B-type stars (κ = −2.8, π = 0.0); and flat distributions, which were observed by Kobulnicky et al. (2014) in the Cygnus OB2 association (as well as Almeida et al. (2017, π = −0.1)) and Shenar et al. (2022b, with κ consistent with 0) (but we treated this mostly as an academic example). We note that these distributions might not be independent (Moe & Di Stefano 2017). While the lower orbital period limit is given naturally by RLO at ZAMS, we need to be careful about the upper limit. We chose to only consider orbital periods up to 103.5 d ≈ 3162 d, as this is the range considered by Sana et al. (2012), Sana et al. (2013), and Dunstall et al. (2015). As they noted that 50–70% of massive stars have orbital periods below that value and this upper limit coincides roughly with the maximum orbital period for RLO (see Sect. 3), the remaining fraction of stars is either single or in wide non-interacting binaries, rendering them effectively single for our purposes. We assumed a binary fraction of 100% and circular initial orbits, as tidal effects will circularise the orbit before the onset of RLO (Zahn 1977). As we implemented stellar rotation (see Sect. 2.3), it is also possible to choose the initial rotation of the models. We assumed no rotation, a bimodal distribution as in Dufton et al. (2013), synchronised (as in Langer et al. 2020), and a flat equatorial rotation distribution between zero and a user-determined value. We restricted the present study to initially synchronised stars, as tidal interaction predicts this to be archived during evolution towards RLO (Zahn 1977). We used the same stellar models for all rotation rates, which is justified for stars not too close to critical rotation (Brott et al. 2011).

After a system is initialised, it is evolved by COMBINE until only SRs remain. In practice, this means the code determines the time until the radius of one model becomes larger than the Roche radius according to the formula of Eggleton (1983), which marks the onset of an RLO or the end of the stellar evolution. For the intermediate time, the orbital period is adjusted to account for mass loss and the rotational velocity evolves as described in Sect. 2.3.

If one of the two stars is destined to overfill its Roche lobe, COMBINE evaluates whether the donor is stripped by stable mass transfer, a common envelope ejection occurs or the two stars merge. The criteria for that are discussed in Sect. 2.2. In case of stable mass transfer, COMBINE employs the analytical descriptions of Soberman et al. (1997) to describe the change in the orbital period. For this study, we assume that all ejected mass carries the same specific orbital angular momentum as the accretor. We assumed that the mass-transfer efficiency is constant throughout the RLO and treated it as a free parameter, whose value we chose to vary in this study. After the end of the mass transfer, COMBINE searches the stellar model grid for a new model for the accretor with matching core mass and total mass. Since the envelope mass increased, the new model appeared to be younger compared to the old model (rejuvenation). The donor was assumed to become a HeS and a matching model was determined from the HeS model grid. In case of a Case BB/BC RLO, when the donor is already a HeS, we assume an instant SN after the RLO. The duration of a Case B mass transfer was assumed to be of the order of a thermal timescale of the donor. For the duration of the Case A mass transfer and the donor mass thereafter see Sect. 2.2. All unstable RLOs were checked to determine whether a common envelope ejection is possible. We assumed, however, that all unstable RLOs lead to a merger (described in Sect. 2.2), as common envelope ejection is expected to take a very small fraction of the population considered in this study.

When the end of stellar evolution is reached, an SR is formed. Depending on the structure of the final stellar model, this is a WD, NS, or BH. If the helium core mass exceeds 6.6 M⊙, we assume a BH is formed (Sukhbold et al. 2018). The complete carbon core and 80% of the helium layer above it collapse into the BH, and we reduced that mass by 20% to account for the release of gravitational energy (Kruckow et al. 2018, and references therein). If the mass of the carbon core is above 1.435 M⊙, a NS is formed by a core collapse SN (CCSN); if it is between 1.37 M⊙ and 1.435 M⊙, we assume an electron capture SN (ECSN) as calculated by Tauris et al. (2015). The NS masses are around 1.3 M⊙ with the detailed formulae given in Kruckow et al. (2018). If the carbon core is lighter than 1.37 M⊙, a WD is formed, which inherits the progenitor’s carbon core mass as its total mass.

From the velocity distribution of young pulsars (Hobbs et al. 2005; Verbunt et al. 2017) it is known that a SN imposes a natal kick on the NSs. For ECSNe, our standard assumption is a uniformly distributed kick between 0 and 50 km/s (Podsiadlowski et al. 2004; Dessart et al. 2006; Kitaura et al. 2006). For the CCSN, we used a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for the kick velocity, w,

with a 3D root-mean-square velocity (wrms) of  for H-rich progenitors (Hobbs et al. 2005),

for H-rich progenitors (Hobbs et al. 2005),  for HeS (Tauris & Bailes 1996; Tauris et al. 2017; Coleiro & Chaty 2013), and

for HeS (Tauris & Bailes 1996; Tauris et al. 2017; Coleiro & Chaty 2013), and  for SNe after Case BB/BC (Kruckow et al. 2018). Following Tauris et al. (2017) and Kruckow et al. (2018), we assumed that 20% of the systems with stripped stars receive a kick of

for SNe after Case BB/BC (Kruckow et al. 2018). Following Tauris et al. (2017) and Kruckow et al. (2018), we assumed that 20% of the systems with stripped stars receive a kick of  . We varied these assumptions by running one scenario without SN kicks and one with only 3D root-mean-square velocities of

. We varied these assumptions by running one scenario without SN kicks and one with only 3D root-mean-square velocities of  . We refer to these scenarios as ‘fiducial’, ‘no kick’, and ‘Hobbs’. It is unknown whether BHs receive a natal kick (Nelemans et al. 1999; Janka 2013; Repetto & Nelemans 2015; Mandel 2016) and so, we used two extreme scenarios: either no kick or a flat kick distribution between 0 and 200 km/s (Kruckow et al. 2018). Table 1 summarises the SN kicks. We used the results of Tauris & Takens (1998) to calculate the post-SN orbit or (if the binary ends up breaking up) the centre-of-mass velocities of the two components.

. We refer to these scenarios as ‘fiducial’, ‘no kick’, and ‘Hobbs’. It is unknown whether BHs receive a natal kick (Nelemans et al. 1999; Janka 2013; Repetto & Nelemans 2015; Mandel 2016) and so, we used two extreme scenarios: either no kick or a flat kick distribution between 0 and 200 km/s (Kruckow et al. 2018). Table 1 summarises the SN kicks. We used the results of Tauris & Takens (1998) to calculate the post-SN orbit or (if the binary ends up breaking up) the centre-of-mass velocities of the two components.

SN properties for the fiducial scenario.

To generate a stellar model population, we need a large number of binaries for the calculations. Each system is assigned an age according to a predefined distribution function and the parameters of each system at its assigned age are evaluated. For this study, we restricted ourselves to a flat age distribution, equivalent to a constant star-formation rate. We assumed a value in the SMC of 0.05 M⊙/a (Harris & Zaritsky 2004; Rubele et al. 2015, 2018; Hagen et al. 2017; Schootemeijer et al. 2021) and scaled our Monte Carlo results by it to determine the expected number of binary systems. To do so, we summed the total simulated stellar mass (accounting for the additional stars below 3 M⊙), using this result and the age distribution to calculate the simulated star-formation rate, and compare this number to the assumed star-formation rate. The effects of a varying star-formation rate are discussed in Paper I.

2.2. Updates to ComBinE: Single stars, mergers, and Case A

We implemented several updates to COMBINE. This section deals with the minor ones. Compared to Kruckow et al. (2018), we used a new definition for the core mass, Mc, which is expressed as Mc = M − MH/Xenv, where M is the total mass of the model, MH is the model’s hydrogen mass, and Xenv is the average hydrogen mass fraction of the stellar profile with X > 0.1. In the previous version, the mass coordinate for X = 0.1 was used, leading to inconsistencies for hydrogen burning models. The new definition turned out to be a better predictor for the stripped stellar mass. Additionally, it helps numerical stability as it causes Mc to be more monotonically increasing with time. This is important when finding a stellar model based on mass and core mass in the grids. Another change is that the carbon core mass of the hydrogen-rich models is now considered as well to better predict the SN properties and the remaining lifetime of the HeS.

A notable fraction of binary stars merge to a single star throughout their lives (Podsiadlowski et al. 1992; de Mink et al. 2014). While the true nature of a stellar merger is complicated, we simplified the process by assuming that 10% of the stellar mass is lost in the process (de Mink et al. 2013) and use ordinary single-star models to describe the merger product. The model of the merger process is rejuvenated according to its central helium content. We assumed that the merger process lasts one thermal timescale. Following Schneider et al. (2019), we set the rotation rate of the product to 10% of the critical rotation. COMBINE is not able to model the changed surface abundance patterns, nor the expected magnetic fields of the merger product.

In the previous version, it was assumed that the duration of Case A mass transfer and the final mass of the donor star could be modelled in the same manner as for Case B. We improved the treatment by adopting the results of Schürmann et al. (2024); namely, implementing fit formulae for these two quantities depending on the initial donor mass and the initial orbital period.

To determine whether the RLO leads to donor stripping, we used the results of Schürmann & Langer (2024) by modelling the evolution of the size of the L2 sphere and the radius evolution of the accretor, which depends on the mass-dependent ratio of the accretor’s thermal timescale and the mass-transfer timescale of the system modelled by the donor’s thermal timescale and the mass-transfer efficiency. If the accretor grows larger than the L2 sphere, we assumed unstable mass transfer, which leads, in general, to a merger.

There are further conditions under which we assume the RLO leads to a common envelope phase or merger. If accretion onto a hydrogen-rich model after central hydrogen exhaustion occurs, the accretor expands fast. Thus, a contact system forms, which is believed to be unstable and to merge quickly. We can assume a similar fate if the mass is transferred onto a HeS, since a hydrogen envelope of 10–50% of the stellar mass produces a bloated star (Kippenhahn et al. 2012), leading to a contact configuration, as described above. This fate can be challenged, if the mass-transfer efficiency is small enough to keep the accretor within its Roche lobe. We assume that mass transfer is not stable if the donor has developed a convective envelope. However this approach has been challenged by Ge et al. (2010, 2015, 2020a) for binaries with mass ratios close to unity (see also Quast et al. 2019; Marchant et al. 2021; Ercolino et al. 2024). The donor might lose mass through its outer Lagrange point and could trigger a common envelope evolution (Ge et al. 2020b). Lastly, it is assumed that systems with mass rations smaller than 0.1 merge immediately.

In case of a HeS donor, we employed the same criteria and, additionally, the orbital period limit from Tauris et al. (2015). We did not use the criterion of Dewi & Pols (2003) by which the donor is assumed to become convective if it is lighter than some threshold mass leading to a merger. However it turns out (see Sect. 3) that if a merger is avoided during the first RLO, it is also avoided in a subsequent RLO Case BB/BC.

2.3. Updates to ComBinE: Rotation

We implemented stellar rotation into COMBINE. For that purpose, we added the stellar moment of inertia, I, to the tabulated non-rotating single-star models COMBINE relies on in form of the moment of inertia factor, α = I/MR2. A homogeneous sphere would have α = 0.4 and if its density increases towards the centre, we would find α < 0.4. We show the moment of inertia factor of our stellar models in Fig. 2. Even though a rotating star deforms, leading to a change of moment of inertia, we assume this effect is of second order and use the single star moment of inertia in this work.

|

Fig. 2. Evolution of the moment of inertia factor of our SMC models. The abscissa is scaled in units of hydrogen burning times. |

Knowing a star’s rotational angular velocity, ω, we can calculate its rotational velocity at the equator, vrot, by multiplication with the star’s equatorial radius, Req, (de Mink et al. 2013). Since the star deforms due to rotation, the equatorial radius can be up to 1.5 times larger than the polar radius, Rp, which remains almost equal to the non-rotating radius. The ratio of the equatorial radius to the polar radius is a function of ω/ωcr ∈ [0, 1), where ωcr is the critical angular velocity of the model before it breaks up due to the centrifugal forces at the equator being larger than gravity. Thus, we have

where  is the Eddington factor with the electron scattering opacity κ = 0.2 (1 + X) cm2/g (Kippenhahn et al. 2012). Following Rivinius et al. (2013), the radius ratio is

is the Eddington factor with the electron scattering opacity κ = 0.2 (1 + X) cm2/g (Kippenhahn et al. 2012). Following Rivinius et al. (2013), the radius ratio is

Here, we simplified their expression. The critical rotational velocity is then given as vcr = ωcrReq. The rotational deformation does not lead to an earlier RLO, since we assume that before Roche-lobe filling the model’s rotation synchronises to the orbit, which leads to only mild radius ratios of a factor of about 1.1.

With this expression, we can trace the rotation of a stellar model over its evolution given an initial rotation and assume the same nuclear evolution as for a non-rotating single-star model. If the spin angular momentum, S = Iω, of the star is conserved (neither mass loss nor tidal torques), the angular velocity of the next time step is given by

where we mark the quantities of the next time step with a prime and left those of the previous time step unmarked. We assume a rigid rotation, which is sufficiently fulfilled for main-sequence models, but after central hydrogen exhaustion stellar models clearly rotate differentially (e.g. Yoon et al. 2010; Schürmann et al. 2022). We were not able to trace differential rotation meaningfully with our means and, thus, we resigned from computing it thereon. In addition, the rotational decoupling process between core and envelope is not trivial, as Schürmann et al. (2022) showed.

If stellar winds become important, the change of spin angular momentum is

neglecting deformation and assuming isotropic winds (Georgy et al. 2011, see however Hastings et al. 2023). The wind mass loss rate, Ṁ, can be calculated from our tabulated stellar models. Following Langer (1998), wind mass loss is amplified by rotation in form of Ṁamp = x Ṁ with

for vrot/vcr ∈ [0,0.8]. Since this expression diverges for vrot/vcr → 1, we extrapolated it linearly by assuming the slope of Eq. (9) at x = 0.8, giving

With this, we can write

leading to

In a binary system, the stars are subject to tides. To account for this we calculate the synchronisation time scales, τsync, of the models as Eq. (44) in Hurley et al. (2002) for hydrogen burning models with radiative envelopes (M > 1.2 M⊙) and Eq. (27) for hydrogen burning models with convective envelopes (M < 1.2 M⊙), see also Hut (1981). This gives us

with Ω as the angular velocity of the orbit (e.g. Detmers et al. 2008). Recently, Sciarini et al. (2024) pointed out possible inconsistencies in this formalism. Equations (12) and (13) were applied one after another to yield the models’s angular velocity at the next time step. Since the orbital angular momentum of a model is much larger than its spin angular momentum, we can neglect changes of the orbit.

If this scheme leads to a model spinning over-critically, namely, ω > ωcr, we let the model lose additional mass at its equator. As the specific spin angular momentum there is ωR2 (noticing that in contrast to Eq. (8) the factor  disappears) and thus ΔS = ΔMωR2. We can assume that the mass loss to bring the model down to critical rotation is small, as Packet (1981) showed that large changes in stellar rotation require only small changes in mass, and therefore the change of radius is small, too, so we write ΔS = αMR2Δω. Equating these two expressions gives the additional mass loss to bring a model from rotating over-critically back to sub-critical rotation as

disappears) and thus ΔS = ΔMωR2. We can assume that the mass loss to bring the model down to critical rotation is small, as Packet (1981) showed that large changes in stellar rotation require only small changes in mass, and therefore the change of radius is small, too, so we write ΔS = αMR2Δω. Equating these two expressions gives the additional mass loss to bring a model from rotating over-critically back to sub-critical rotation as

It is generally assumed that accretion leads to the spin-up of stars. We calculated the accreted angular momentum depending on whether or not an accretion disk forms by calculating

where a is the semi-major axis (Lubow & Shu 1975; Ulrich & Burger 1976; Paxton et al. 2015). If the accretor radius is larger than this value, we assumed ballistic accretion with a specific angular momentum of  and otherwise accretion from a Keplerian rotating disk at its equator and thus with a specific angular momentum of

and otherwise accretion from a Keplerian rotating disk at its equator and thus with a specific angular momentum of  , where M and R refer to the accretor’s mass and radius. We assumed that a critically rotating accretor can keep accreting mass but limited its rotation to the critical value as the viscosity inside the disk transports mass inwards but transports angular momentum outwards (see Paczynski 1991; Popham & Narayan 1991; de Mink et al. 2013, for a discussion). An alternative view, where the accretion is limited by the accretors spin-up (Petrovic et al. 2005; Marchant Campos 2018), is investigated in Paper I.

, where M and R refer to the accretor’s mass and radius. We assumed that a critically rotating accretor can keep accreting mass but limited its rotation to the critical value as the viscosity inside the disk transports mass inwards but transports angular momentum outwards (see Paczynski 1991; Popham & Narayan 1991; de Mink et al. 2013, for a discussion). An alternative view, where the accretion is limited by the accretors spin-up (Petrovic et al. 2005; Marchant Campos 2018), is investigated in Paper I.

3. Dependence of binary evolution on mass ratio, orbital period, and mass-transfer efficiency

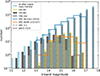

Before we construct synthetic populations from our binary models, we need to understand how different initial masses, initial mass ratios, initial orbital periods and mass-transfer efficiencies affect the evolution of a binary in our code. Therefore we drew 104 binary models with uniform distribution in initial mass ratio, qi, (mass of the initially less massive star divided by the mass of the initially more massive star) and logarithmic initial orbital period, log Pi, for several fixed primary masses and mass-transfer efficiencies (with the non-accreted material carrying the same specific angular momentum as the accretor), and evolved them. We classified the evolutionary path either by the first SR that is produced or by a merger that happens before that, and colour the log Pi-qi plane according to the nearest model. For merging systems, we differentiated between the different reasons for that. In Fig. 3, we assumed an initial mass of 10 M⊙ and the online material contains similar diagrams for other masses. For simplicity, we assumed no SN kick.

In Fig. 3 we find that for low mass-transfer efficiencies most binaries can evolve to OB + NS systems (yellow) and, in case of high mass-transfer efficiencies, mergers dominate because of accretor swelling and subsequent L2 overflow (blue). At high orbital periods, we expect mergers due to the donor star developing a convective envelope (red) and at even wider orbits no RLO takes place at all (white). A large fraction of systems experience a Case BB/BC mass transfer (+-like pink hatching) except for wide systems, as the HeS is not able to fill such a large Roche lobe. Very close systems, which undergo Case A mass transfer, end up as OB + WD systems (green) since the mass of the stripped donor decreases with decreasing initial orbital period for Case A. If the initial mass ratio for Case A is too close to unity (orange) the slow phase of the mass transfer lasts so long that the accretor ends hydrogen burning, expands and fills its Roche lobe. So, a contact system is formed, which we assumed will merge fast. We discuss systems of initial mass ratios close to unity in Sect. A.

If we consider higher donor masses, we find that Case BB/BC RLOs soon disappear from the evolution as the HeSs do not grow to large radii for higher masses. The regions where mergers occur only shift slightly. Around masses of 20 M⊙ (online material) the donor becomes a BH (dark grey). For even higher masses we find that the Case A/B boundary shifts to higher orbital periods and that the merger region at q ≈ 1 becomes larger as the mass-lifetime exponent decreases.

Comparing these diagrams to the predictions by Schürmann & Langer (2024), we find about the same boundary between donor stripping and merger, as expected. In contrast to them, we find that our models merge at very low periods and high mass ratios and strip the donor (for high mass-transfer efficiencies) at high periods and high mass ratios. The differences arise, as Schürmann & Langer (2024) already predicted, since they neglected the evolution of the accretor, which we consider in the work presented here and which leads to the formation of contact systems as described above. Compared to Paper I, we predict mergers only at mass ratios far from unity if the mass-transfer efficiency is not too high. Only for very high mass-transfer efficiency, systems at intermediate mass ratios and high periods merge. The models of Paper I merge for intermediate mass ratios at low periods (independently for Case A and B), as the non-accreted material is gravitationally stronger bound, when the stars are close and the Roche radii are small, which makes the ejection of that material by their energy criterion harder. With our criterion, in close systems the donor radius is small when the RLO starts, which causes the thermal mass-transfer rate to be small and so the accretors do not swell and a contact is avoided. As we show in Sect. 5, this leads to strong differences for the period distributions of BeXB and OB + BH systems.

4. Influence of the mass-transfer efficiency on the synthetic populations

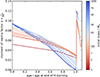

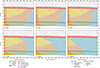

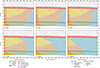

In this section, we generate synthetic binary populations, where the probability of drawing systems depends on the initial mass, initial mass ratio and initial orbital period distributions described in Sect. 2. We also employed the different kick scenarios and varied the mass-transfer efficiency from 10% to 100% in steps of 10% with additional values of 5%, 3%, 2%, and 1%. Each simulation contains 107 binary models and is scaled to a constant star-formation rate of 0.05 M⊙/a. We extracted the number of selected types of stars and binary systems (O-type stars, OB stars, OBe stars, BeXBs, and WR + O systems) and compare them to the observed numbers in Fig. 4.

The four panels in Fig. 4 are ordered in such a way that we can easily identify the impact of the initial binary parameters. The two panels on the left side have rather flat mass ratio distributions (κ ≈ 0.0) but those of the panels to the right are skewed towards more unequal systems (κ = −2.8 and −1.0). The upper panels both have a flat period distribution (π = 0), while for the two lower panels, close systems are preferred (π ≈ −0.5).

We calculated the number of systems with O-type stars by classifying all models with an effective temperature greater than 31 600 K as such. A margin of error can be derived from varying this number by one spectral class, namely, 30 350 K and 32 900 K (Schootemeijer et al. 2021), which is about 30%. The observed number of about 400 is the estimate corrected by completeness from Schootemeijer et al. (2021) and Shenar et al. (2024). The numbers of OB (hydrogen-burning model above 104 K) and OBe stars only includes stars with an absolute Gbp magnitude brighter than −3 (M ≳ 8 M⊙Schootemeijer et al. 2021), which is the completion limit of Schootemeijer et al. (2022). We used a distance modulus of 18.91 (Hilditch et al. 2005) and calculated the absolute Gbp magnitude following Schootemeijer et al. (2021). We classified all hydrogen-burning models as OBe stars if they spin faster than 0.95 times their critical rotational velocity (Townsend et al. 2004) and varied this number by including slow rotator and/or merger products. The observed numbers of OB and OBe stars are from Schootemeijer et al. (2022). We classified a model as a WR star if it is a HeS with a luminosity larger than 105.6 L⊙ (Shenar et al. 2020) and compared them to the four WR + O systems in the SMC (Shenar et al. 2016, 2018). (The other seven, seemingly single WR stars might have been formed through single-star evolution or in a later phase of binary evolution, and thus are disregarded in our analysis.) The margin of error is the Poisson counting uncertainty (i.e. ±2). Finally, we classified a model as BeXB, if it contains an OBe star according to the definition from above and an NS. 107 BeXBs are known in the SMC (Haberl & Sturm 2016)1 and the dimmest has a magnitude of 16.9.

For all initial distributions in Fig. 4, we identify a clear overproduction of O-type stars. This is not unexpected as this dearth was already discussed by Schootemeijer et al. (2021). The total number of bright OB stars is consistent with the observations and deviates by less than a factor of 1.5. Both quantities are almost independent of the mass-transfer efficiency. The predicted number of WR + O stars agrees with the distributions in Fig. 4 (top left, bottom left, and bottom right) in a wide range of mass-transfer efficiencies with the best match at low mass-transfer efficiencies. For the distribution in the top right, only mass-transfer efficiencies below 5% yield an agreement between simulations and observations. Thus, the number of WR + O systems is unaffected by reasonable variation of the initial period distribution but depends more on the initial mass ratio distribution. More extreme initial mass ratios lead to more mergers, reducing the number of systems. For all initial distributions, we find that the WR + O number decreases with increasing mass-transfer efficiencies. This comes from the larger merger area in Fig. 3 and the reduced lifetime of the accretor.

For the same reasons, we find fewer BeXBs at high mass-transfer efficiencies. It is only for very small mass-transfer efficiencies that we observe the opposite trend; in this case there is not enough mass transferred to the accretor, which then does not spin fast enough to become an OBe star. We predict most BeXBs for the no-kick scenario and least for the Hobbs scenario, as stronger kicks break up the systems more easily. An initial mass ratio distribution favouring low mass ratios (κ = −0.1 → −1, lower left to lower right panel in Fig. 4) decreases the number of BeXBs due to more systems merging and a period distribution favouring low periods (π = 0 → 0.5, top panels to bottom panels) increases the number of systems especially at high mass-transfer efficiencies as wide systems merge there more often than close systems (Fig. 3). A higher mass-transfer efficiency causes the magnitude of the dimmest BeXB to be smaller, as expected for a heavier accretor. This behaviour is independent of the initial mass ratio and initial orbital period distribution as it does not consider the number but only the occurrence of such systems.

|

Fig. 3. Evolutionary outcome of our binary models with a primary mass of 10 M⊙ at the time when the first SR has formed, or when the system merges, as a function of initial orbital period (Pi) and initial mass ratio (qi) for six different mass-transfer efficiencies (ε). Each black dot represents one model system, and their total number in each plot is 104. We coloured the plane according to the result of the closest model (Voronoi diagram). We mark the boundary between RLO Case A and B by a black line. The occurrence of a later RLO with a HeS donor (i.e. Case BB or BC) is indicated by pink hatches. If the companion to a SR is not a MS star but a post-MS star, we mark it by orange cross-hatches in case it is H-rich (BSG/RSG), or by pink cross-hatches if it is H-poor (HeS). White regions are those with no RLO (top) or RLO at ZAMS (bottom). In grey areas, the outcome is not none of the above (often two SNe immediately after each other due to the final temporal resolution). |

For OBe stars, we find that their number increases with larger mass-transfer efficiency. While a lifetime effect might be present, here the assumed magnitude limit comes into play. A larger mass-transfer efficiency pushed more binaries with lower initial primary mass, which are preferred by the IMF, over the magnitude threshold than a lower mass-transfer efficiency. We find more OBe stars for steeper period distributions and flatter mass ratio distributions. For the Dunstall et al. (2015) distribution (top right) the curve showing the number of OBe stars is outside the range of the plot, meaning that this distribution underestimates the number of OBe stars by more than a factor of 10. Only the Sana et al. (2012) distribution (bottom left) reproduces the observed number of OBe stars when only considering fast rotators and only at very high mass-transfer efficiencies. When slow rotators are included, the two left panels of Fig. 4 produce the observed number of OBe stars with intermediate mass-transfer efficiencies. However, when doing this, one should also consider all OB + NS systems as BeXBs, which would lead to an overproduction of BeXBs. Another approach would be to vary the star-formation rate in such a way that it takes a higher value when the OBe star progenitors are born. However, it turns out that this is at the same age when the BeXB progenitors were born, so their number would be lifted, too. Figuratively speaking, both approaches mean that we cannot lift the OBe star curve without lifting the BeXB curve. Possible solutions could be to reduce the number of BeXBs again by assuming less reduced SN kicks or considering either merger products or single-star evolution as a channel for OBe star production. The above mentioned overproduction of OB stars simultaneous with the underproduction of OBe stars supports this finding.

In all figures, except Fig. 4 (top right), the line for the number of BeXBs and for the magnitude of the dimmest one meet at a mass-transfer efficiencies of 60–75%, close to the desired observed level. This suggests that during the formation of BeXBs the mass-transfer efficiency was rather high. The number of WR + O systems is best reproduced with low mass-transfer efficiencies, but only with a very large uncertainty, as indicated by the shading in Fig. 4. However, as we discuss in Sect. 6.3, there seem to be a preferences for low mass-transfer efficiencies at high stellar masses. This means that the mass-transfer efficiency might be a function of stellar mass. We assume in the following that the mass to be considered is the accretor mass, as we assume that this is the place in the system where the material is ejected. LMC stars are probably a better proxy for SMC stars than Milky Way stars, and so we choose the distributions of Sana et al. (2013, bottom right) as our fiducial set. In our model, the median initial mass of the accretor in WR + O systems is 35 M⊙, while it is 7 M⊙ for BeXBs. So, we varied the mass-transfer efficiency linearly between these two accretor masses, MA, which yields

|

Fig. 4. Predicted number of selected types of stars and binary systems relative to the observed number (given in parentheses in the legend) as a function of mass-transfer efficiency. We show four different assumptions about the stars that become OBe stars – fast rotating accretors (solid line), fast and slow rotating accretors (dashed), fast rotating accretors and merger products (dotted), fast and slow rotating accretors and merger products (dash-dotted) – and three different assumptions about the SN kick – reduced kicks (solid), Hobbs kicks (dashed), and no kicks (dotted). The green line with labelling on the right side of the diagram shows the magnitude of the dimmest synthetic BeXB relative to the dimmest observed one (16.9). The pink shading indicated the uncertainty due to the low number of WR + O systems. The initial binary parameter distributions are flat (top left), according to Sana et al. (2012, bottom left), Sana et al. (2013, bottom right), and Dunstall et al. (2015, top right). |

and we took the boundary values of 0.6 and 0.1 outside that range. The median mass of accretors in OB + BH progenitors turns out to lie with 15 M⊙ somewhere in between causing a typical mass-transfer efficiency of about 35% in such systems.

In Fig. 5 (top), we present the absolute number of OBe stars with HeS, NS and BH companions including those that were unbound from their NS in the SN. We assume the initial distributions from Sana et al. (2013). (See Fig. B.1 for other initial distributions.) We only consider HeS heavier than 2.55 M⊙, which is a rough limit between WD and NS formation. The numbers reach a maximum at mass-transfer efficiencies of 3%, since for larger values the accretors become heavier and thus live shorter and the lowest mass-transfer efficiencies depose not enough angular momentum on the accretor to become an OBe star. The number of of OBe + HeS does not drop as steeply as the others as it is, in general, the HeS, which evolved faster and ends the OBe + HeS phase. A stronger (weaker) SN kick reduces the number of OBe + NS = BeXB systems, while the number of unbound systems is increased (decreased). We find that the BH kick can unbind a substantial number of systems, reducing their number by a factor of two. We predict 10–200 OBe + BH systems. For a mass-transfer efficiency of 30%, which is the typical values one finds with Eq. (16), we predict 50 of them.

|

Fig. 5. Predicted number of OBe star (top) and regular OB star (bottom) companions indicated by colour and different kick scenarios indicated by line style as a function of mass-transfer efficiency for the initial distributions of Sana et al. (2013). |

In Fig. 5 (bottom), we show those OB-star models that are not rotating fast enough to be classified as emission-line stars. Again, the numbers shrink with larger mass-transfer efficiency. Towards low mass-transfer efficiencies, we find a sharp increase in the number of regular OB stars. This is because accretors are no longer spun up enough to become OBe stars. The OB + BH systems show a different slope than the other species. This may be due to the lower exponent of the mass-lifetime relation for massive stars. Furthermore the SN kicks affect these systems less than the OBe systems since non-OBe stars originate generally from closer and more strongly bound systems. We expect about 150 normal OB + BH systems.

5. The fiducial model with mass-dependent mass-transfer efficiency

In this section we present the properties of our fiducial simulation, namely, where the mass-transfer efficiency is a function of accretor mass according to Eq. (16), with the initial mass ratio and orbital period distributions of Sana et al. (2013) and the SN kicks as in Table 1. In the following, we often differentiate between OBe stars (main-sequence OB stars with Balmer emission lines) and regular or normal OB stars (main-sequence OB stars without emission lines). For this analysis, we rerun our fiducial model with 108 binary models.

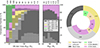

5.1. Companions of OB stars after mass transfer in the SMC

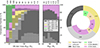

In Fig. 6 we show the predicted fractions of companion types to our core-hydrogen-burning SMC models after mass transfer, as a function of their mass. This figure includes systems that become unbound during the SN event, but excludes merger products, single stars, and binary stars before interaction. We found four types of companions in such systems as well as systems unbound by the SN explosion, each occurring typically in a certain mass range. HeSs can be found over the whole mass spectrum. This is not surprising, as they are the immediate outcome of stable mass transfer. They make up about 20% of OB-star companions. For the lowest and the highest considered masses, this fraction reaches up to 30%. Fewer than half of their OB star companions are expected to be emission-line stars with a shrinking fraction towards higher masses.

|

Fig. 6. Left: Predicted companion fraction of massive (M > 8 M⊙) main-sequence SMC stars in post-mass transfer binaries as function of their mass, including system in which the companion (in general a NS) was unbound during the SN, and excluding merger products. Models that we assumed to appear as emission-line stars are marked with black or white dots (depending on the background colour). Above each mass bin we give the total number of system in that bin. The total number of each companion type is given in the legend distinguishing between emission-line star (first number) and normal OB star (second number). Right: Absolute number of compact companions of OB stars (outer pie chart), and the assumed SN type of the NS progenitor (inner pie chart), predicted by our fiducial SMC population. |

Up to an OB-star mass of 14 M⊙, WDs can be found as companions, where most OB stars are expected to be emission-line stars. This is corroborated by the fact that most of these systems undergo a Case BB/BC RLO after core helium-exhaustion of the primary, during which the accretor is spun up a second time. NSs appear as companions for OB-star masses above about 8 M⊙ and dominate above about 12 M⊙. The NS companion fraction is largest around 15 M⊙ and drops to zero above about 24 M⊙. The ratio of normal OB + NS systems to OBe + NS systems increases towards higher masses. In contrast to the WDs, we predict a notable number of normal OB stars with NS companions, as the higher mass stripped stars avoid a mass transfer after core helium exhaustion. Many OBe stars spin down during core-helium burning of the stripped stars, which can be seen from the synthetic OB + HeS systems, as they are all assumed to rotate critically after mass transfer. Unbound systems have been found for the same OB-star masses as NS companions, as they share the same evolutionary past. Unbound OB stars have a larger OBe fraction than systems with NSs, which is probably caused by a larger probability of systems with high orbital periods, where tidal breaking does not play a role, to unbind during the SN explosion. We predicted 138 NS + OBe systems which we expect to appear as BeXBs, in good agreement with the observations. Additionally, we found 35 normal OB stars with NS companions.

Lastly, for OB stars above about 14 M⊙, we expect BH companions to start forming. They become the dominant companion type above around 18 M⊙ and reach a nearly constant fraction of around 80% for OB-star masses above 22 M⊙. Only for the highest considered OB-star masses (> 70 M⊙), the fraction of BHs decreases slightly. About 30% of BHs have an OBe companion and this number decreases with OB-star mass. The reasons are angular momentum loss by the stellar wind and the tides imposed by the BH and its HeS progenitor on to the star, which can be seen from their period distribution (see Sects. 5.3 and C). At such high masses, angular momentum loss by wind also becomes important, which can be seen by the decreasing number of OBe + BH systems for increasing OB mass. We predict for the SMC a total number of 142 OB + BH binaries for the scenario without a BH kick. 36 of them should have emission line companions. Additionally, we expect 106 normal OB + BH systems. This means that about 3% of all OB stars with an absolute magnitude brighter than −3, including pre-interaction systems, contain a BH, and around 6% of all OBe stars do. If we consider O-type stars only, these numbers become 10% and 50%.

Figure 6 (right) shows that bound OB + NS systems, unbound OB + NS systems, and OB + BH systems occur with roughly the same numbers. The dominant SN mode is CCSNe from a HeS progenitor (pink), which make up about 60% of all events. About 3/4 of them unbind the NS from the system. Systems with small helium core masses undergo an RLO Case BB/BC after core helium exhaustion and produce almost naked CO cores. As we assume that they experience smaller kicks, most of them remain bound. ECSNe, which have the smallest kicks (Table 1). In general, they do not lead to disruption and make up fewer than 1% of the unbound systems. In this scenario, without a BH kick, no BH is unbound from its companion star, and so all unbound systems released an NS. We discuss the effect of BH kicks in Sect. D.

5.2. Masses of OB stars and their companions

In Fig. 7 we show the predicted masses of the components of bound and unbound OB + NS systems and OB + BH systems. We find stellar masses (top row) from 9 to 100 M⊙. In different mass ranges, different companion types dominate. We find NS companions for stars with 9 to 22 M⊙ and BHs from 14 to 100 M⊙. Systems which broke up due to the SN kick follow the same patterns as NS systems, with slightly heavier OB stars as the former peak around 13 M⊙, while the latter reach their maximum at 12 M⊙. OB stars with BH companions have their mode at 20 M⊙.

|

Fig. 7. Predicted masses of the components of massive binary systems after RLO and the formation of a SR. Top row: OB star masses coloured according to their companion type and marked with dots if we expect an emission-line star. The inlays in the upper right corners focus on the upper mass end. Bottom row: BH masses with dots in case of a OBe companion. Note: the vertical axis is logarithmic. Left: Total numbers. Right: Case A RLO (top) and B (bottom) separately. |

We can understand the mass distributions considering the assumed binary physics. We find the lightest NS progenitors to have an initial mass of about 10 M⊙, corresponding to a 3 M⊙ helium core at core hydrogen exhaustion. Thus, 7 M⊙ are lost from the donor during the mass transfer. The mass transfer efficiency is around 60% in this mass range and the minimum mass ratio for stable mass transfer is about 0.5 (see Fig. 3), which yields a lower limit of 5 M⊙ for the initial mass of the accretor, and therefore a minimum mass of 9 M⊙ for the OB star as seen in Fig. 7 (top). Similarly, the upper limit and the ranges of the BH companions can be understood.

Figure 7 (top right) shows Case A and B systems separately. We find that almost all regular OB stars evolved through Case A since in close orbits tidal forces are more efficient in braking the star. Systems tend to disrupt more frequently in Case B, which is due to the lower binding energy in wide orbits. In Case A systems, the mass distributions are slightly wider. This is caused by orbital-period-dependent donor mass after RLO (see Schürmann et al. 2024). Since the main-sequence models expand stronger for larger mass in our stellar model grid, the preference for BH systems to evolve through Case A is not surprising.

The lower panels of Fig. 7 show the mass distribution of the BH companions. They range from 4 to 32 M⊙ and show a slope dlog N/dMBH of about −0.05. The minimum BH mass derives from the minimum mass of a HeS to form a BH, which is 6.6 M⊙, and the BH formation prescription (Sect. 2) and thus it is 4.8 M⊙. The upper mass limit, about 30 M⊙, can be found similarly by taking away 50% of the initial mass of a 100 M⊙ star, our upper limit, to get the mass of the collapsing HeS.

The BH masses depict interesting differences between RLO Case A and B (Fig. 7, bottom right). While the mass distribution of Case A BHs shows the same slope as the total population, for Case B dlog N/dMBH is with −0.1 twice as large. We attribute this to the widening of the main sequence for increasing stellar mass. As already mentioned, BHs whose progenitor evolved through Case B prefer to have OBe companions, while those are rare for Case A BHs. For those, we find a large dip of OBe companions around 12 M⊙. It is unclear to us what causes it, but we expect it to have a limited effect as it would increase the number of emission line companions only by 4–5, if one would remove the dip by drawing a straight line over it. BHs that formed after a Case B RLO do not reach the same maximum mass as those from Case A because our stellar models above 80 M⊙ did not evolve beyond central hydrogen exhaustion.

In Fig. 8 (second row left), we show the combined mass distributions for OB + BH systems (see also Sect. C). This distribution can be described as being framed by four lines. At first, there are the upper and lower BH masses, as discussed previously. As we have shown in this section, we can divide the BH mass by 0.36 to estimate its initial stellar mass. Secondly, the population is limited to the left by a diagonal line following q ≈ 1. These systems stem from those with the initially most extreme mass ratios of about 0.3. Take for instance the upper left corner with MBH ≈ 30 M⊙ and MOB ≈ 30 M⊙. The initial BH progenitor mass was about 100 M⊙ and the initial accretor mass about 25 M⊙, since the mass-transfer efficiency is small at high masses. The systems in the lower left corner on the other hand (MBH ≈ 6 M⊙ and MOB ≈ 10 M⊙) had initial masses of about 15 M⊙ and 6 M⊙ due to the higher mass-transfer efficiency.

|

Fig. 8. Predicted properties of OB + BH systems. The left panels shows the number of systems in the OB mass–BH mass plane (second row), OB mass–orbital period plane (third row), and OB mass–OB velocity semi-amplitude plane (fourth row) in logarithmic colouring and the other panels are projections of that onto one axis, i.e. the distribution of OB masses (first row left), BH masses (second row right), orbital periods (third row right), and OB star velocity semi-amplitudes (fourth row right), where emission-line stars are marked by white dots. We also show the properties of all dynamically confirmed OB + BH systems in the local group and of the WR + O systems in the SMC with WR masses as BH masses. |

The systems at the right side of Fig. 8 (second row left) are bounded by a line of q ≈ 0.2…0.3 and come from systems with a mass ratio initially close to unity. Here, however, effects of Case A mass transfer come into play. Take, for example, a system with initial masses of 15 M⊙ and 14 M⊙. If the donor loses half of its mass of which about a third (Eq. (16)) is gained by the accretor, the OB star would have 16 M⊙, but the diagram shows accretors as heavy as 22 M⊙ in the lower right corner of the population. This is due to the fact, that donors which evolve through Case A mass-transfer can lose more than half of their mass, especially if a Case ABC mass transfer strips them even further, reducing the mass of the BH and increasing the mass of the OB star. For the density of systems per pixel in Fig. 8 (second row left) we note, that the number of systems decreases for larger BH masses, but is fairly constant for varying OB-star masses. The former derives from the IMF and the latter from the near flat initial mass ratio distribution. This means it is more likely to find a 30 M⊙ OB star with a 15 M⊙ BH than with a 30 M⊙ BH, but it is about equally likely for a 20 M⊙ BH to have a 30 M⊙ and a 50 M⊙ OB companion.

Figure 9 shows the predicted OB + BH population in the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (HRD). It is expected that fast-rotating stars will redden due to the von Zeipel-theorem. We are not able to include this effect in our analysis as our models are fixed and rather show the non-rotational effective temperature. The OB stars have luminosities from 104.5 L⊙ to 106.5 L⊙ and display temperatures from 25 kK to 50 kK corresponding to O- and the earliest B-type stars. For the most massive companions, the main-sequence broadens a lot leading to a lowest effective temperature of 10 kK. Their contribution is, as we can see in the upper panels, negligible. The HRDs for the predicted OB + NS systems are provided in Sect. C.

|

Fig. 9. Predicted HRD positions of OB stars with a BH companions in logarithmic colouring together with selected model tracks and the ZAMS. We include values of all observed OB + BH systems and the O-type star of SMC WR + O systems (see Fig. 8 for the symbols). The panels on top and on the right show the temperature and luminosity distributions with predicted emission-line stars highlighted by dotting. |

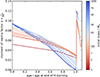

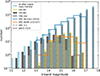

To make a meaningful comparison of our simulations with the observations, we estimate the V-band magnitudes of our OB-star models by using the recipe from Schootemeijer et al. (2021), which is based on Dotter (2016) and Choi et al. (2016), to calculate magnitudes from luminosity and effective temperature. We show the results in Fig. 10. There, the slope of the expected OBe stars dlog N/dmV of about 0.55 until a magnitude of 12, where their number drops significantly, while the number of all post-RLO systems continues to follow the same slope. A difference already appears around mV = 14. The magnitudes we found for OB + NS binaries reach from 13 to 17 with a maximum of around 15.5. The distribution is skewed towards dimmer stars. BeXBs are slightly more common at larger magnitudes. BHs can be found around stars brighter than mV = 16. Their distribution is flatter and less skewed than the OB + NS distribution.

|

Fig. 10. Predicted and observed distribution of V-band magnitudes. The blue bars show the magnitudes of all OB star models (i.e. with HeS, WD, NS, and BH companion and unbound systems) after stable mass transfer. OBe candidates are marked with dots. As observations we show the SMC OBe magnitudes distribution (blue line) from Schootemeijer et al. (2022), the magnitudes of BeXBs (orange line) from Haberl & Sturm (2016)2, SMC X-1 (grey dashed line) and J0045-7319 (brown line). |

Living version: https://www.mpe.mpg.de/heg/SMC

5.3. Orbital parameters

For the systems that remain bound after the formation of the SR, we can analyse their orbital properties, namely, the orbital period, Porb, eccentricity, e, and orbital velocity semi-amplitude of the OB star, expressed as

Here, a is the semi-major axis. Figures 8 and 11 show these orbital properties of our OB + BH binaries. In the bottom left panel of Fig. 8, we can see that systems with masses around 20 M⊙ and velocity semi-amplitudes from 25 to 150 km/s are preferred. Only the widest systems, those with low orbit velocities, become OBe stars. The upper right corner is empty as their progenitors would have initially overfilled their Roche lobe. No systems can be found at high velocities and low masses because the donor after Case A is too light to form a BH. The centre right panel of Fig. 11 shows a somewhat narrow relation between orbital period and velocity semi-amplitude, which is due to Kepler’s law. In the centre left panel of Fig. 8 the combined distribution of orbital period and OB-star mass is shown. Both quantities are highly skewed and peak at low values. Towards high masses and periods a wide plane can be found. The upper right corner is empty because such systems are very rare due to the initial distributions. Systems with low periods and high masses are avoided as such systems would overfill their Roche lobe initially. Finally, the bottom centre panel of Fig. 11 depicts orbital period and eccentricity. The eccentricity only assumes values between 0.05 and 0.2 and strongly peaks at 0.1. The reason is our BH formation formalism. As 20% of the helium envelope is lost, the BH progenitor loses some of its momentum, which translates to a non-zero eccentricity (Tauris & Takens 1998). Varying the mass loss or imposing a kick on the BH would change the resulting eccentricity dramatically. We note, however, that our prescription does not account for the continuous circularisation of the orbit due to tides after the SN, so the real eccentricity may be lower. Nevertheless, the eccentricity distribution of wide OB + BH systems could be a probe for BH kicks.

|

Fig. 11. Predicted properties of OB stars that have BH companions with measurements of all dynamically confirmed OB + BH systems in the local group and of the WR + O systems in the SMC. The main panels shows the number of systems in the rotational velocity-velocity semi-amplitude plane (first column, second row), orbital period-velocity semi-amplitude plane (second column, second row), and eccentricity-velocity semi-amplitude plane (second column, third row) in logarithmic colouring and the other panels are projections of that onto one axis, i.e. the distribution of OB rotational velocities (top left), orbital periods (top centre), OB star velocity semi-amplitudes (centre right), and eccentricities (bottom right), where emission-lines stars are marked by white dots. |

We show a combined histogram of rotational and orbital velocity of OB + BH systems in Fig. 11 (centre left). We find that the OB + BH populations divides clearly in two sub-groups. The somewhat larger group can be found at low rotational (< 200 km/s) and medium to high orbital (> 50 km/s) velocities. These systems evolved through Case A RLO and are normal OB stars. Systems with high rotational (> 300 km/s) and low orbital (∼50 km/s) velocities form the second group and are in general emission-line stars. This has an important implication for the observational search for BHs, namely that on one hand high radial velocity variations in SB1 systems and on the other hand that OBe stars are a predictor of BH companions.

The orbital properties period and eccentricity of OB + NS binaries are shown in Fig. 12. We do not treat mass ratio and orbital velocity here because the NS mass is strongly confined and the OB stars’ velocities are very low due to the low NS mass, see however Fig. C.1. The centre panel shows a 2D histogram of orbital period and eccentricity. The eccentricities follow a very broad distribution covering all values from 0 to 1 and the periods’ mode is, as discussed above, between 10 and 100 d. The combined distribution has accordingly a large main feature at these values. A notable exception is a preference for large orbital periods at high eccentricities and an avoidance of high eccentricities at low orbital periods. This is not surprising as this would lead to Roche-lobe overfilling periastron distances. While emission-line stars are more frequent at large orbital periods, we find no dependence on eccentricity.

|

Fig. 12. Predicted orbital properties of OB + NS systems with observations of the SMC BeXBs, SMC X-1, and J0045-7319. Centre: Orbital period-eccentricity plane. Top: Orbital period coloured by SN type. Right: Eccentricity coloured by SN type. |

In the top and right panels of Fig. 12, we show the period and eccentricity distributions coloured according to the SN type. CCSNe from a HeS, CCSNe after a Case BB/BC RLO, and ECSNe have slightly different typical orbital periods, increasing in that order. This means systems with a stronger kick end up with lower orbital periods, which may sound counter-intuitive but can be explained by wider orbits being more likely to unbind than close orbits or by the different initial parameter spaces of different SN types. Furthermore, CCSNe from HeS progenitors are the only species that yield a notable amount of regular OB stars as tidal breaking before the SN is only possible here. In the case of a CCSN after Case BB/BC RLO, the OB star was just spun-up again, and systems that undergo an ECSN and are close enough for effective tidal braking also experience such a mass transfer. The eccentricities of systems that evolved through ECSNe show the smallest eccentricities and those which experienced a CCSN from a HeS the largest. This also reflects the magnitude of the SN kick as higher kick velocities lead to more eccentric systems. As mentioned above we did not employ continuous tidal induced circularisation of the orbit which may affect the eccentricity distribution.

5.4. Systemic velocity

Because a SN kick changes the momentum of the system, we are able to predict the space (centre of mass) velocity  of our OB-star systems and ejected OB stars as we do in Figs. 13 and C.5. We find that NS systems (yellow) have the broadest distribution from 0 to up to 100 km/s. Even more striking is that this distribution is bimodal with one narrow maximum at 10 km/s and a wide one at 40 km/s. Inspecting the upper left panel we see that the first peak comes from ECSNe and CCSNe of a Case BB/BC donor. The second peak comes exclusively from CCSNe with a HeS progenitor, as they have the highest kick velocities, which lead to high space velocities. CCSNe preceded by Case BB/BC RLO and ECSNe end up with lower space velocities, which is in agreement with the strength of their kicks. NS systems with the largest space velocities do not tend to be OBe stars. This is due to the fact that the pre-SN orbital velocity leaves an imprint on the space velocity (Tauris & Takens 1998). Thus, we can assume that they come from initially close binaries which explains the absence of fast rotation. The panel on the top right of Fig. C.5 supports that Case A produces faster systems.

of our OB-star systems and ejected OB stars as we do in Figs. 13 and C.5. We find that NS systems (yellow) have the broadest distribution from 0 to up to 100 km/s. Even more striking is that this distribution is bimodal with one narrow maximum at 10 km/s and a wide one at 40 km/s. Inspecting the upper left panel we see that the first peak comes from ECSNe and CCSNe of a Case BB/BC donor. The second peak comes exclusively from CCSNe with a HeS progenitor, as they have the highest kick velocities, which lead to high space velocities. CCSNe preceded by Case BB/BC RLO and ECSNe end up with lower space velocities, which is in agreement with the strength of their kicks. NS systems with the largest space velocities do not tend to be OBe stars. This is due to the fact that the pre-SN orbital velocity leaves an imprint on the space velocity (Tauris & Takens 1998). Thus, we can assume that they come from initially close binaries which explains the absence of fast rotation. The panel on the top right of Fig. C.5 supports that Case A produces faster systems.

For unbound systems (grey contour in Fig. 13) we find the most common space velocity of the OB star just above 10 km/s. They again reach up to almost 100 km/s but do not have the bimodality of their bound counterparts. BH systems also show a unimodal distribution, but with lower velocities (peak at 20 km/s), since we do not assume any BH kicks. Their velocities are, as well as the eccentricities, caused by the mass loss during BH formation. With our adopted assumptions, BH systems do not break up.

In the centre of Fig. 13, we show a 2D histogram of spacial and rotational velocities of all OB + SR systems, whether bound or unbound. We find similarly to Fig. 11 (centre left) two populations. First, there are systems with high rotational (> 300 km/s) and relatively low spatial velocity (peak at 10 km/s), which are the Case B and wide Case A systems. Then there are systems with low rotational (∼100 km/s) and higher spacial velocities (mode at 20 km/s). These are the narrow Case A systems where tidal locking is relevant, which inherited their fast orbital velocity as systemic velocity.

6. Discussion

In this section, we compare our results with observations (Sect. 6.1), with Paper I (Sect. 6.2) and previous works (Sect. 6.3). The main uncertainties of our simulations are discussed in Sect. D.

6.1. Comparison with observations

In this section, we compare our predicted distribution to observations of SMC systems and suitable proxies. We focus mostly on systems with BH or NS companions and their directly observable properties.

6.1.1. BH systems

No OB + BH system has been observed thus far in the SMC. Therefore, we relied on OB + BH systems observed in the local group and WR + OB systems, which are believed to evolve to OB + BH systems (Langer 2012), as proxies. The OB + BH systems in question are Cyg X-1 (Orosz et al. 2011; Miller-Jones et al. 2021), LMC X-1 (Orosz et al. 2009), M33 X-7 (Orosz et al. 2007; Ramachandran et al. 2022), VFTS 243 (Shenar et al. 2022a), and MWC 656 (Casares et al. 2014, the true nature is under debate, see Rivinius et al. 2024 and Janssens et al. 2023). For the WR + O systems, we rely on Shenar et al. (2016) and Shenar et al. (2018) and references therein. We aligned all analysed quantities by considering their inclination. The BH systems exist in environments with higher metallicities than the SMC, which has effects on the mass limit for BH formation, the BH mass, and the OB star mass and rotation by wind mass loss and wind angular momentum loss (Langer 2012; Tauris & van den Heuvel 2023).