| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A265 | |

| Number of page(s) | 20 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554890 | |

| Published online | 15 December 2025 | |

Nonlinear saturation of gravito-inertial modes excited by tidal resonances in binary neutron stars

1

Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics (Albert Einstein Institute), D-14476 Potsdam, Germany

2

School of Mathematics, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK

3

Departament de Física Aplicada, Universitat d’Alacant, Ap. Correus 99, E-03080 Alacant, Spain

4

Theoretical Astrophysics, IAAT, University of Tübingen, Tübingen D-72076, Germany

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

31

March

2025

Accepted:

27

August

2025

Context. During the last seconds of a binary neutron-star merger, the tidal force can excite stellar oscillation modes to large amplitudes. From the perspective of premerger electromagnetic emissions and next-generation gravitational wave (GW) detectors, gravity (g-) modes constitute a propitious class. However, existing estimates for their impact employ linear schemes, which may be inaccurate for large amplitudes, as achieved by tidal resonances. With rotation, inertial modes can be excited as well, and while their nonlinear saturation has been studied, an extension to fully consistent gravito-inertial modes, especially in the neutron-star context, is an open problem.

Aims. We study linear gravito-inertial modes and the nonlinear saturation of these modes and investigate the astrophysical consequences for binary neutron-star mergers, including the possibility of tidally excited dynamo activity.

Methods. A new (non)linear formulation based on the separation of equilibrium and dynamical tides is developed. Implementing this into the 3D pseudo-spectral code MagIC, a suite of nonlinear simulations of tidally excited flows with an entropy and/or composition gradient in a stably stratified Boussinesq spherical-shell are carried out.

Results. The new formulation accurately reproduces results of linear calculations for gravito-inertial modes with a free surface for low frequencies. For a constant-density cavity, we show that the axisymmetric differential rotation induced by nonlinear 2g and 1g modes may theoretically be large enough to amplify an ambient magnetic field to ≳1014 G. In addition, rich nonlinear dynamics are observed in the form of parametric instabilities of the 1g mode. The stars are also spun-up, which extends the resonance window for any given mode.

Conclusions. This study provides nonlinear numerical support for a recently proposed scenario where, to accommodate the nonthermal precursor flares seen in some short gamma-ray bursts, the magnetic field of a premerger star is amplified by resonant g-modes. It further suggests that g-mode resonances may have a stronger impact on GW signals than previously estimated.

Key words: hydrodynamics / waves / methods: numerical / binaries: general / stars: neutron / stars: oscillations

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open Access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1. Introduction

Binaries are common in nature, with some estimates of stellar multiplicity being close to unity based on modern astrometric surveys (Duchêne & Kraus 2013; El-Badry 2024). Tidal forces play an important role in the rotational and orbital evolution of close systems, such as binary stars (e.g., Zahn 2013; Barker 2022, and references therein), exoplanetary hot-Jupiter systems (e.g., Jackson et al. 2008; Bolmont & Mathis 2016; Lazovik et al. 2024), planet-satellite systems (Counselman 1973; Fuller et al. 2024, for a review), and merging neutron stars (NSs; Damour & Nagar 2009; Taniguchi & Shibata 2010). Their impact can generally be quantified in terms of two components, these being the equilibrium and dynamical tides. The former exists even in the zero-frequency limit and describes bulk geometric large-scale deformations, while the latter relates to the excitation of internal (damped) waves (e.g., Ogilvie 2014; Hinderer et al. 2016; Andersson & Pnigouras 2020).

A perturbative and often even linear treatment of tides provides an excellent approximation in many astrophysical systems of interest. There are cases, however, where the validity of a linear approximation is less certain (see Sect. 4 of Ogilvie 2014, for a review). One such scenario – central to this paper – involves resonances in NS mergers. As the binary shrinks due to gravitational-wave (GW) radiation-reaction, the orbital frequency “chirps” upward toward coalescence (e.g., Peters 1964). When the tidal driving frequency approaches the oscillation frequency of a mode inside one of the stars, that mode’s amplitude grows rapidly. The amplitude may peak at a value that depends on the degree of orthogonality between its eigenfunction and the appropriate multipole component of the tidal field (“overlap”; Press & Teukolsky 1977; Alexander 1987), or if the resonance window lags behind the ever-increasing tidal forcing frequency, at a value that depends on how rapidly the frequency evolves away from the resonant frequency. For some mode classes, the amplitude could theoretically grow beyond the linear regime, necessitating nonlinear corrections (e.g., Yu et al. 2023; Kwon et al. 2024, 2025) or tidal nonlinearities (Pitre & Poisson 2025) to be taken into account to more accurately assess how tides affect GW or electromagnetic observables.

Numerical relativity simulations have highlighted the impact of nonlinearities on GW dephasing for the fundamental (f-) mode (Kuan et al. 2025). Though subdominant, gravity (g-) modes – supported by internal composition and/or entropy gradients – may also non-negligibly accelerate inspiral in mergers as their eigenfrequencies are sufficiently low (∼102 Hz) to be excited approximately a few seconds prior to coalescence while maintaining sizeable overlaps (Kokkotas & Schafer 1995; Kuan et al. 2021a; Passamonti et al. 2021; Hegade 2024). Since these modes offer valuable microphysical information and it is hoped that templates will be matched to GW data in the future, it is important that their nonlinear saturation be quantified. For stars retaining a high angular frequency into old age (Ω ≳ 102 Hz; “recycled pulsars”) the inertial class of modes (restored by Coriolis acceleration) may also be relevant (Lai & Wu 2006; Suvorov & Kokkotas 2020). With both buoyancy and rotation present, the two branches merge to some degree and go under a “gravito-inertial” label (see, e.g., Aerts & Tkachenko 2024). Here we present a method for modeling the nonlinear saturation of such hybrid modes. In particular, nonlinearities are treated at the level of the magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) equations of motion, rather than via secondary couplings between linear modes as studied previously (e.g., Weinberg et al. 2013; Pnigouras & Kokkotas 2015; Zhou & Zhang 2017). This marks the first time, therefore, that this class and their saturation have been modeled consistently at a nonlinear level for rotating, tidally forced NSs.

Nonlinear, tidally forced inertial modes have been studied in numerical simulations modeling convective envelopes of giant gaseous planets and low-mass stars in close binary systems (Favier et al. 2014; Barker 2016; Astoul & Barker 2022). Due to the generation of differential rotation, transfer rates of tidal energy (i.e., tidal dissipation) can be either higher or lower by up to ∼3 orders of magnitude relative to linear-theory predictions at some frequencies (especially for thin shells, large tidal amplitudes, and low viscosities; Astoul & Barker 2023). In radiative regions, differential rotation can also arise from the deposition of gravity wave angular momentum at corotation resonances – when the horizontal velocity of the wave matches the local speed of the fluid – as predicted by Goldreich & Nicholson (1989) in the envelopes of early-type stars. This result has been confirmed for the radiative cores of solar-like stars in 2D and 3D spherical nonlinear simulations, where the core is progressively spun up from inside out by tidal gravity wave breaking (or weakly nonlinear damping) near the center of the star (Barker & Ogilvie 2010; Barker 2011; Guo et al. 2023). Here, we also study such nonlinear effects but in the context of gravito-inertial modes in NSs by building on the formulation used in Astoul & Barker (2022) to split tides into equilibrium and dynamical components while adding buoyancy and thermal diffusion.

Based on this “split formulation”, accounting for the fact that the Brunt-Väisälä (BV) frequency of a cold NS is typically much lower than its dynamical (hydrostatic) response frequency, we ignored surface waves and assumed impermeable and stress-free boundaries. We used the pseudo-spectral MagIC1 code (Wicht 2002; Gastine & Wicht 2012; Schaeffer 2013) to solve the hydrodynamical equations in a spherical shell under the Boussinesq approximation (Spiegel & Veronis 1960). The equations were coupled to the leading-order (ℓ = m = 2) tidal potential for frequencies relevant to the late-stages of inspiral, with (effective) viscosity included in anticipation of damping and turbulence. Magnetic effects may be especially relevant in some mergers, as there is evidence to suggest that those systems, which release nonthermal gamma-ray burst (GRB) precursor flares (≲5% of mergers; Wang et al. 2020; Coppin et al. 2020), contain magnetars with near-surface fields of B ≳ 1013 G (e.g., Xiao et al. 2024). Fields of this strength can influence mode spectra (e.g., Suvorov et al. 2022; Kuan et al. 2021a) or merger dynamics directly (e.g., Ciolfi 2020). A thorough comparison with a linear scheme, using the Dedalus3 code (Burns et al. 2020), is also provided to explore the direct impact of nonlinearities.

Although this is primarily a “methods” paper where the above-described strategy is presented in detail and then integrated numerically for a variety of setups, we also explore some astrophysical applications. For example, incorporating magnetic fields naturally allows for the investigation of dynamo action, namely the magnetorotational instability (MRI; Balbus & Hawley 1998; Astoul & Barker 2025), sourced by the differential rotation induced by non-axisymmetric mode activity. The nonlinear scheme allows, in principle, for us to compare with the idea suggested by Suvorov et al. (2024a) that magnetar-level fields are generated on the verge of coalescence rather than preserved over cosmological timescales. As such, longevity appears difficult to reconcile with magnetothermal evolutions (Pons & Viganò 2019).

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the neutron-star hybrid modes and the equations governing both the linear (Sect. 2.2.1) and new nonlinear (Sect. 2.2.2) schemes used throughout, with details on numerical implementation provided in Sect. 2.4. Results for both g- and more general gravito-inertial modes in cases with rotation are given in Sect. 3 for the linear and Sect. 4 for the nonlinear cases, respectively. Astrophysical implications are briefly explored in Sect. 5, with discussion provided in Sect. 6. Key results are summarized in Sect. 7.

2. Modeling of the tidal resonance of gravito-inertial modes in a neutron star binary

2.1. Simplified neutron star model

In this work, we studied the tidal forcing of gravito-inertial modes in the late stages of a binary neutron-star inspiral. To do this, we used methods and formulations from the stellar and planetary community, where linear codes and, more recently, nonlinear simulations are developed following the split methodology mentioned earlier. As a first study in the context of binary NSs, we adopted the idealized Boussinesq approximation that allows us to study the impact of stable entropy and/or composition stratification while keeping the simulations computationally efficient so that the parameter space can be efficiently explored. This approximation corresponds to assuming that variations in mass density can be neglected except as they contribute to buoyancy, i.e., the fluid is otherwise incompressible and sound waves are filtered (Spiegel & Veronis 1960). This approximation is partly justified because the velocities of resonant modes are strictly subsonic, as found in previous studies (Kuan et al. 2021a; Passamonti et al. 2021; Suvorov et al. 2024a), while the constant density assumption is made for simplification (see Sect. 6.2). We used the Newtonian Navier-Stokes equations throughout and neglected the effects of general relativity, as the Boussinesq approximation is already a more restrictive approximation. Note that we also assumed the neutron-star interior to contain only a normal fluid, ignoring superfluidity and superconductivity.

The fluid stratification is characterized by the background BV frequency,

where g, ρ0, ρ, S, P and Ye are background quantities, respectively, the gravitational acceleration, background uniform density (see below), density, entropy, pressure, and electron fraction. As a simplification, we assumed that the BV frequency depends only on one dimensionless background buoyancy variable, chosen here as  . In our model, we assumed that the background density and BV frequency stay constant in time. The latter condition amounts to assuming that (nuclear) weak interaction timescales are much longer than internal hydrodynamical timescales and that the entropy entrained by fluid motions is negligible. As a result, the background flow is adiabatic and the frozen compositional gradient gives rise to buoyancy. We evolved density perturbations through the buoyancy variable

. In our model, we assumed that the background density and BV frequency stay constant in time. The latter condition amounts to assuming that (nuclear) weak interaction timescales are much longer than internal hydrodynamical timescales and that the entropy entrained by fluid motions is negligible. As a result, the background flow is adiabatic and the frozen compositional gradient gives rise to buoyancy. We evolved density perturbations through the buoyancy variable  , where δρ is the perturbed density. In this work, we refer to the diffusion process associated with this buoyancy variable as the thermal diffusivity, κth. This does not reduce the (numerical) generality of the problem as the buoyancy variable could be entropy or composition and would play exactly the same role in either case (ignoring double-diffusive effects). We used an explicit dissipation and nonadiabatic processes for the perturbations for numerical stability reasons, as the numerical dissipation is not enough to stabilize the simulation with (pseudo-)spectral methods. For dissipation processes, we adopted uniform profiles of viscosity ν and thermal κth (or compositional κcomp) diffusivities with ν = κth for the sake of simplicity2.

, where δρ is the perturbed density. In this work, we refer to the diffusion process associated with this buoyancy variable as the thermal diffusivity, κth. This does not reduce the (numerical) generality of the problem as the buoyancy variable could be entropy or composition and would play exactly the same role in either case (ignoring double-diffusive effects). We used an explicit dissipation and nonadiabatic processes for the perturbations for numerical stability reasons, as the numerical dissipation is not enough to stabilize the simulation with (pseudo-)spectral methods. For dissipation processes, we adopted uniform profiles of viscosity ν and thermal κth (or compositional κcomp) diffusivities with ν = κth for the sake of simplicity2.

The model for the NS used is that of a spherical shell with a uniform density ρ0. This quantity is determined by the mass of the primary, given as  , where Ro is the stellar radius of the primary and depends on the equation of state (EOS). For tests of the new formulation, we first assumed that the shell has an inner radius Ri, whose ratio to the stellar radius (Ro) is set as α ≡ Ri/Ro = 0.5. This value has been used in previous studies of (gravito-)inertial waves in planets and stars as a standard (e.g., Ogilvie 2009; Favier et al. 2014; Astoul & Barker 2022; Pontin et al. 2023) and it reduces the numerical costs as a lower resolution can be taken. However, a thin shell with α = 0.5 is a bad approximation for NSs as changing the size of the shell also changes the resonant frequencies and the mode amplitudes. Therefore, for astrophysical applications to NSs, we instead took α = 0.1 to approximate a whole NS without substantially increasing numerical costs. In addition, g-mode eigenfunctions in NSs peak away from the region

, where Ro is the stellar radius of the primary and depends on the equation of state (EOS). For tests of the new formulation, we first assumed that the shell has an inner radius Ri, whose ratio to the stellar radius (Ro) is set as α ≡ Ri/Ro = 0.5. This value has been used in previous studies of (gravito-)inertial waves in planets and stars as a standard (e.g., Ogilvie 2009; Favier et al. 2014; Astoul & Barker 2022; Pontin et al. 2023) and it reduces the numerical costs as a lower resolution can be taken. However, a thin shell with α = 0.5 is a bad approximation for NSs as changing the size of the shell also changes the resonant frequencies and the mode amplitudes. Therefore, for astrophysical applications to NSs, we instead took α = 0.1 to approximate a whole NS without substantially increasing numerical costs. In addition, g-mode eigenfunctions in NSs peak away from the region  (Kuan et al. 2021a) so this approximation is reasonable (see Sect. 5.1 for a direct comparison of the linear modes).

(Kuan et al. 2021a) so this approximation is reasonable (see Sect. 5.1 for a direct comparison of the linear modes).

2.2. Governing equations

We placed ourselves in a frame rotating with the star and assumed an initial hydrostatic balance, i.e.,  where g is the gravitational acceleration and

where g is the gravitational acceleration and  is the background pressure. The equations for the perturbed velocity components can then be written as

is the background pressure. The equations for the perturbed velocity components can then be written as

where u, p and b are velocity, pressure, and buoyancy perturbations, Ωs is the (constant) stellar angular frequency of the background star, Ψ is the tidal potential, and τν is the viscous stress tensor. Note that the components of velocity are designated by ui with spherical polar components i ∈ [r, θ, ϕ] instead of the contravariant equivalent ui in GR calculations. Centrifugal and other forces that may lead to a nonspherical cavity are neglected. We chose to neglect perturbations in the gravitational potential for the sake of simplicity and because they are not expected to play a significant role in the context of our Boussinesq system (Ogilvie & Lin 2004, though for quantitative predictions of resonances they may need to be included). This hypothesis is discussed in detail in Sect. 6.4. This makes it easier to compare between formulations as we neglected the contributions of the gravitational potential perturbations due to the equilibrium tides characterized by the Love number k2 (see Sect. 6.4).

In our Boussinesq model, the heat equation thus takes the form

where the global gradient of the buoyancy variable  is linked to the radially dependent BV frequency through

is linked to the radially dependent BV frequency through

In the case of pure entropy or composition stratification, we would obtain  or

or  , respectively.

, respectively.

Leaving aside events involving dynamical capture, orbital eccentricity is expected to be erased long before coalescence in a neutron-star binary merger (e.g., Peters 1964). Because of this and for simplicity, we considered a circular but asynchronous orbit with no spin-orbit misalignment (though cf. Kuan et al. 2023). The dominant (quadrupolar) component of the tidal potential can be written as (e.g., Zahn 1966)

where Ylm is a spherical harmonic of degree ℓ and order m, and the strength of the potential is (see, for instance, Eq. (3) and Table 1 in Ogilvie 2014)

where M2 is the companion mass, a is the orbital semimajor axis, and  is the dynamical frequency with G being the gravitational constant. In the rotating frame introduced earlier, the tidal forcing frequency reads

is the dynamical frequency with G being the gravitational constant. In the rotating frame introduced earlier, the tidal forcing frequency reads  , where Ωo is the orbital frequency, and we note that

, where Ωo is the orbital frequency, and we note that  can be negative. Equations (2)–(4) constitute the full nonlinear equations considered here. The reader who is less interested in details and tests regarding the new formulation and numerical implementations may skip ahead to Sect. 4 for discussions on nonlinear saturation amplitudes or Sect. 5 for the astrophysical application of binary NSs mergers.

can be negative. Equations (2)–(4) constitute the full nonlinear equations considered here. The reader who is less interested in details and tests regarding the new formulation and numerical implementations may skip ahead to Sect. 4 for discussions on nonlinear saturation amplitudes or Sect. 5 for the astrophysical application of binary NSs mergers.

2.2.1. Linear equations

To have a point of comparison with previous literature, we first derived the equations describing linear gravito-inertial modes. These are similar to those from Pontin et al. (2024), which read

In this study, we considered three distinct BV profiles: a uniform BV frequency in Sect. 3, a uniform buoyancy variable gradient, which leads to a BV frequency varying radially and linearly with the gravitational acceleration of a homogeneous body, g = −ger = −g0rer in Sect. 4, and a realistic profile from Suvorov et al. (2024a) in Sect. 5. To solve the linear system, we took a non-penetrating boundary condition for the radial velocity at the inner boundary and a free surface where normal stress vanishes at the outer boundary following Pontin et al. (2023, 2024). We further imposed stress-free conditions (no tangential stress) at the two boundaries, with either the buoyancy variable fixed (b = 0) or its gradient  at the two boundaries, since this has little impact on the resonances (Pontin et al. 2023). This setup will be referred to as a “full formulation” hereafter as it encompasses both the equilibrium and dynamical tides. However, the implementation of a free surface in a fully nonlinear code is prohibitively costly, as surface oscillations would occur at frequencies of ∼ωd, while the rotation rate and (gravito-inertial or BV frequency) mode frequencies are much lower for NSs.

at the two boundaries, since this has little impact on the resonances (Pontin et al. 2023). This setup will be referred to as a “full formulation” hereafter as it encompasses both the equilibrium and dynamical tides. However, the implementation of a free surface in a fully nonlinear code is prohibitively costly, as surface oscillations would occur at frequencies of ∼ωd, while the rotation rate and (gravito-inertial or BV frequency) mode frequencies are much lower for NSs.

2.2.2. A new formulation to excite gravito-inertial modes

A derivation for separating equilibrium and dynamical tides, especially for inertial modes, can be found in numerous studies (see, for example, Ogilvie & Lin 2004; Zahn 2013; Ogilvie 2013; Astoul & Barker 2022, and references therein). For the treatment of the gravito-inertial modes, we took a slightly different approach to the one used in Dhouib et al. (2024): as the equilibrium tide corresponds to the instantaneous hydrostatic response to the tidal force, we assumed that reequilibration between pressure and gravity is reached instantaneously compared to the buoyancy variables (i.e., p and g evolve much faster than b in the current context). Another way of describing this treatment is to assume that the advection of the background gradient of the buoyancy variables by the equilibrium tide is part of the heat equation, Eq. (4), for the dynamical tides. It acts as an effective (“heating” or buoyancy driving) forcing of the waves by the equilibrium tide (see Eq. (16)). Then the heat equation for the equilibrium buoyancy variable (i.e., be) would be

which gives be = 0 as there are no source terms. This corresponds to assuming that the equilibrium tide flow ue is fully incompressible, and thus we adopted the expression valid for ℓ = m = 2 inertial modes (Ogilvie 2013; Lin & Ogilvie 2018; Astoul & Barker 2022, 2023)

with

where u is satisfying the free-surface boundary condition at the top and impenetrability at the bottom. Here Ct = (1+Re[k22])ϵ is the tidal force amplitude related to the real part of the quadrupolar Love number Re[k22] and the tidal amplitude parameter ϵ = (M2/M1)(Ro/a)3.

Equation (12) leads to a static pressure perturbation pe that, in addition to ue, compensates the tidal force in the Navier-Stokes equations. With this equilibrium tide, the linear equations for the leftover velocity u′ = u − ue, pressure p′ = p − pe and b′ = b − be become

This system has two effective tidal forcing: ft = −2Ωs × ue, the Coriolis acceleration on the equilibrium tidal flow ue in the momentum equation, and  , the advection of the background entropy gradient by the equilibrium tide in the heat equation. This second term allows us to excite g-modes even in a nonrotating case. It is usually not included in more general split formulations, where background density is not uniform (Ogilvie & Lin 2004; Dhouib et al. 2024), as it is considered as part of an equilibrium tidal buoyancy variable (i.e., entropy/temperature) term. This approach may lead to issues for g-modes in an uniform density star that may not be present with a nonuniform density, depending on the definition of the equilibrium tide. Indeed, in the Boussinesq approximation, we consider that density perturbations are only due to entropy and/or composition perturbations but, as described by Ogilvie (2013), such a density perturbation corresponds to a delta spike at the surface with radial displacement. The heat equation would then force the radial displacement to be zero, yielding a contradiction. Our formalism is a workaround to avoid this issue. A comparison between formalisms with a nonuniform density ρ0 is planned for a future study. The use of a fixed surface also means we cannot have surface modes and, therefore, our formalism is valid for Ωs2, N2 ≪ ωd2, which is the case for NSs and some gas giants (Dewberry 2023; Lin 2023; Suvorov et al. 2024a).

, the advection of the background entropy gradient by the equilibrium tide in the heat equation. This second term allows us to excite g-modes even in a nonrotating case. It is usually not included in more general split formulations, where background density is not uniform (Ogilvie & Lin 2004; Dhouib et al. 2024), as it is considered as part of an equilibrium tidal buoyancy variable (i.e., entropy/temperature) term. This approach may lead to issues for g-modes in an uniform density star that may not be present with a nonuniform density, depending on the definition of the equilibrium tide. Indeed, in the Boussinesq approximation, we consider that density perturbations are only due to entropy and/or composition perturbations but, as described by Ogilvie (2013), such a density perturbation corresponds to a delta spike at the surface with radial displacement. The heat equation would then force the radial displacement to be zero, yielding a contradiction. Our formalism is a workaround to avoid this issue. A comparison between formalisms with a nonuniform density ρ0 is planned for a future study. The use of a fixed surface also means we cannot have surface modes and, therefore, our formalism is valid for Ωs2, N2 ≪ ωd2, which is the case for NSs and some gas giants (Dewberry 2023; Lin 2023; Suvorov et al. 2024a).

In the following, we omit primes when using the above-introduced formulation, hereafter called the “split formulation”, where the nonlinear equations read

With this split formulation, we used non-penetrating boundary conditions for the velocity at both outer and inner boundaries. We also kept the stress-free boundary conditions as in the previous formulations. For both formulations, we tested that the buoyancy variable boundary conditions did not impact significantly the results and chose, therefore, the one that gave the strongest mode amplitudes, setting the gradient of the buoyancy variable to zero, i.e.,  .

.

2.2.3. Energy equations

As we have a new forcing term in the equations, we focus on deriving the new energy balance to understand the dissipation and saturation of tidally forced modes. The dissipation terms correspond to the volume integrated viscous Dν and thermal Dκ dissipation rates given by

By the standard definition of work, the power injected by the tidal force in the full formulation is

In this formulation, the energy balance has already been derived by Pontin et al. (2023, 2024) and is given by

where EK and EPE are respectively the kinetic and potential energy of the star. Their respective rates of change are

except for N2 = 0 where one has  . At saturation and averaged over a forcing period of

. At saturation and averaged over a forcing period of  , energy conservation implies

, energy conservation implies

For the split formulation, the power injected by the effective body force ft due to Coriolis force of the equilibrium tide is given by

To obtain the power for the effective forcing fN in the heat equation, it is easier to use the buoyancy power in the Navier-Stokes equation that is defined by

By substituting ur using the heat equation, we obtain the buoyancy power due to the tidal entropy forcing

This gives the global balance of energy in the split formulation

Note that this final balance is obtained by substituting the buoyancy power, Pbuoy, by its saturation balance in the heat equation, Pbuoy = Pbuoy, e − Dκ, which accounts for the impact of thermal dissipation on the available power for the tidal flows.

2.3. Parameter space corresponding to resonant g-modes for a neutron star binary

Previous linear studies have shown that g-modes could be resonantly excited in a NS binary. We build on the study by Suvorov et al. (2024a) for our NS models constructed with the APR4 EOS (Akmal et al. 1998) coupled to a Douchin and Haensel (DH) crust (Douchin & Haensel 2001). For our tests of both linear (Sect. 3) and nonlinear calculations (Sect. 4), we studied the resonance of g-modes in a 2.0 M⊙ NS, where the frequency of the first g-mode is N = 102.89 Hz. We also considered an equal mass binary, so that the characteristic frequency is ωd = 2288 Hz for both stars. We varied the rotation rate Ωs and rate Ωs = 2πΩs in this study with  Hz being a “standard” value. The resonant gravity, inertial, or mixed gravito-inertial modes are well-separated from ωd and lie in the low-frequency regime. It should be noted that we express frequencies throughout in units of Hz: the reader should be aware, however, that many of these are angular frequencies (e.g., the spin frequency Ωs) and thus are 2 π times the value of the frequency in these units. In addition, the tidal amplitude is as small as ϵ ∼ 10−3 near the g-mode resonance when 2Ωo ∼ N. According to previous studies on inertial modes (Astoul & Barker 2022, 2023), this places us firmly in the linear regime but this could change for a lower viscosity, higher aspect ratio (α > 0.5), or for the resonant gravito-inertial modes with the highest kinetic energy.

Hz being a “standard” value. The resonant gravity, inertial, or mixed gravito-inertial modes are well-separated from ωd and lie in the low-frequency regime. It should be noted that we express frequencies throughout in units of Hz: the reader should be aware, however, that many of these are angular frequencies (e.g., the spin frequency Ωs) and thus are 2 π times the value of the frequency in these units. In addition, the tidal amplitude is as small as ϵ ∼ 10−3 near the g-mode resonance when 2Ωo ∼ N. According to previous studies on inertial modes (Astoul & Barker 2022, 2023), this places us firmly in the linear regime but this could change for a lower viscosity, higher aspect ratio (α > 0.5), or for the resonant gravito-inertial modes with the highest kinetic energy.

With respect to dissipation, we chose our standard viscosity and thermal diffusivity to be ν = κ = 10−6Ro2ωd ≈ 1.7 × 1010 cm2 s−1, similar to Pontin et al. (2023, 2024). This value is many orders of magnitude higher than the microphysical viscosity expected in NSs (Thompson & Duncan 1993) but is chosen to prevent numerical issues. These choices give an Ekman number of

The control parameter for the BV frequency in the simulations is the Rayleigh number, defined as

As an astrophysical application, we study a more standard equal-mass NS binary of 1.6 M⊙ in Sect. 5. The characteristic frequency is then ωd = 1941 Hz. We also used a “realistic” BV frequency and its value at the outer boundary to define the Rayleigh number. The dimensionless numbers are Ra = −5.1 × 1010 and Ek = 6.2 × 10−5 − 1.99 × 10−5 with rotation rates of  Hz, respectively.

Hz, respectively.

2.4. Numerical methods

To solve the linear equations, we used the spectral MHD code Dedalus3 (Burns et al. 2020). Dedalus has been used to handle different types of hydrodynamical and MHD problems, including convection, waves, and magnetic fields in an unstratified or stratified medium in many studies (Lecoanet et al. 2017; Couston et al. 2018; Ji et al. 2023). Using the full formulation, we benchmarked the code results against the study by Pontin et al. (2023) and are therefore confident in the results for when using the split formulation. The number of grid points used for the linear problem was (nr, nθ) = (200 − 400, 200 − 400) depending on the parameters.

In order to integrate the nonlinear equations in time, Eqs. (17)–(19), we used the benchmarked pseudo-spectral code MagIC (Wicht 2002; Gastine & Wicht 2012; Schaeffer 2013). MagIC solves the 3D MHD equations in a spherical shell using a poloidal-toroidal decomposition for the velocity and the magnetic field (made possible by the solenoidal assumption on u),

where W and Z are the poloidal and toroidal kinetic scalar potentials, respectively, while b and aj are the magnetic potentials. The scalar potentials and the pressure P are decomposed on spherical harmonics for the colatitude (θ) and the azimuthal (ϕ) angles, together with Chebyshev polynomials in the radial direction. For more detailed descriptions of the associated spectral transforms and the numerical method, we refer to Gilman & Glatzmaier (1981), Tilgner & Busse (1997), and Christensen & Wicht (2015).

The nonlinear simulations presented in this paper were performed using a standard grid resolution of (nr, nθ, nϕ) = (257, 256, 512). Some of the simulations have a cutoff mmax in the spherical harmonics to speed up the simulations; for simulations in Sect. 4, mmax = 85 is enough to ensure convergence as the dominant mode corresponds to m = 2. The code uses an adaptive timestep where we added a maximum value of  to ensure the resolution of the forced frequency.

to ensure the resolution of the forced frequency.

3. Linear tests of the formulation

In this section we discuss how we tested the new split formulation. As a first step, we demonstrate how we successfully reproduced the properties of g-modes obtained with the “full” formulation (Sect. 3.1). This set us up for studying gravito-inertial modes to check whether the two effective tidal forcings give the correct geometry (i.e., structure) and amplitude of the gravito-inertial modes (Sect. 3.2). In order to compare more easily with Pontin et al. (2023), we adopt in this section the same units as that study: Ro = 1, ωd = 1 and ρ0 = 1.

3.1. Pure g-modes

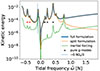

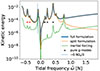

As a benchmark of the Dedalus code and the full and split formulations, we first considered nonrotating stars (Ωs = 0) and also fix N2 = 1 and Ψ0 = 1. For the split formulation, we further used a dimensionless tidal amplitude,  , in this section. We then solved the linear system for both the full formulation and split formulation. In order to verify that mode resonances behave the same, we first plotted the kinetic energy as a function of the tidal forcing frequency

, in this section. We then solved the linear system for both the full formulation and split formulation. In order to verify that mode resonances behave the same, we first plotted the kinetic energy as a function of the tidal forcing frequency  . Figure 1 shows that the dissipation peaks reside at the same frequencies until the tidal forcing frequency becomes close to the f-mode frequency, ωd = 1. This shift was found in Pontin et al. (2023), where the pure g-mode frequencies computed were slightly off the resonant frequencies, with disagreement growing as one approaches ωd because of the boundary conditions assumed in the g-mode analytical derivation. The split formulation recovers, with high accuracy (< 0.4%), the theoretical frequencies of ℓ = m = 2 g-modes (ng22 for radial node-number n); in a cavity for a constant BV frequency N with impermeable boundaries, these are given by Pontin et al. (2023)

. Figure 1 shows that the dissipation peaks reside at the same frequencies until the tidal forcing frequency becomes close to the f-mode frequency, ωd = 1. This shift was found in Pontin et al. (2023), where the pure g-mode frequencies computed were slightly off the resonant frequencies, with disagreement growing as one approaches ωd because of the boundary conditions assumed in the g-mode analytical derivation. The split formulation recovers, with high accuracy (< 0.4%), the theoretical frequencies of ℓ = m = 2 g-modes (ng22 for radial node-number n); in a cavity for a constant BV frequency N with impermeable boundaries, these are given by Pontin et al. (2023)

|

Fig. 1. Kinetic energy as a function of the tidal frequency, |

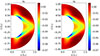

In addition to the characteristic frequencies of g-modes, the split formulation in the regime where  is far from ωd is similarly able to reproduce the eigenfunction of the resonant mode obtained by the full formulation to very high accuracy, within < 0.01% (left panels of Fig. 2). However, when the tidal forcing frequency

is far from ωd is similarly able to reproduce the eigenfunction of the resonant mode obtained by the full formulation to very high accuracy, within < 0.01% (left panels of Fig. 2). However, when the tidal forcing frequency  is of the same order of magnitude as ωd, the split formulation cannot reproduce the resonance as it is expected. Indeed, the split formulation cannot reproduce f-modes as the surface needs to be free to capture these.

is of the same order of magnitude as ωd, the split formulation cannot reproduce the resonance as it is expected. Indeed, the split formulation cannot reproduce f-modes as the surface needs to be free to capture these.

|

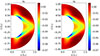

Fig. 2. Comparison of the toroidal velocity uϕ for resonant modes in the full formulation (Panel a) and the split formulation (Panel b) for two representative tidal frequencies |

3.2. Gravito-inertial modes

We applied the split formulation to the tidal resonance problem for low-frequency modes in rotating NSs, where inertial modes and gravito-inertial modes also come into play. We are therefore in the regime where  and Ωs, N ≪ ωd. For our second test, we aimed at probing the impact of the rotation on the gravity modes (i.e., to compare g-modes with gravito-inertial modes) in the right parameter regime. We set Ωs = 0.0139 ωd and N = 0.0450 ωd, respectively.

and Ωs, N ≪ ωd. For our second test, we aimed at probing the impact of the rotation on the gravity modes (i.e., to compare g-modes with gravito-inertial modes) in the right parameter regime. We set Ωs = 0.0139 ωd and N = 0.0450 ωd, respectively.

With these parameters, we computed the kinetic energy of the tidal response (including the equilibrium tide) depending on the tidal frequency for the two formulations. Since we are far from the respective f-mode frequencies, we find that the peak kinetic energy frequencies are identical for both formulations (Fig. 3). We also find that the range of frequency for the gravito-inertial modes is roughly [ − 2Ωs, N] (that is why the frequency range in Fig. 3 is not symmetrical about 0), which is consistent with the limit  found in previous studies (Rieutord 2009; Pontin et al. 2024). By looking at their radial wavelengths, we identify the gravito-inertial modes corresponding to the pure g-modes 4g to 1g with slightly smaller frequencies compared to Eq. (33) in the positive frequencies and from 3g to 2g modes in the negative frequencies. We find that these negative modes corresponding to n = 2 and n = 3 seem to be roughly at frequencies corresponding to

found in previous studies (Rieutord 2009; Pontin et al. 2024). By looking at their radial wavelengths, we identify the gravito-inertial modes corresponding to the pure g-modes 4g to 1g with slightly smaller frequencies compared to Eq. (33) in the positive frequencies and from 3g to 2g modes in the negative frequencies. We find that these negative modes corresponding to n = 2 and n = 3 seem to be roughly at frequencies corresponding to  (i.e., rotation breaks symmetry; in the nonrotating case, negative g-modes are perfectly symmetrical to the positive as in Pontin et al. 2023). The peak at the lower limit of frequencies

(i.e., rotation breaks symmetry; in the nonrotating case, negative g-modes are perfectly symmetrical to the positive as in Pontin et al. 2023). The peak at the lower limit of frequencies  is related to the negative 1g mode, but the resonance peak seems not to be reached (not shown here). We also identify a resonant mode close to the frequency of a resonant Rossby mode at

is related to the negative 1g mode, but the resonance peak seems not to be reached (not shown here). We also identify a resonant mode close to the frequency of a resonant Rossby mode at  . The usual frequency for this resonance is

. The usual frequency for this resonance is  , but it is expected to decrease with α (Ogilvie 2009; Pontin et al. 2024). The identification of the resonant modes with

, but it is expected to decrease with α (Ogilvie 2009; Pontin et al. 2024). The identification of the resonant modes with  is not straightforward since they cannot be predicted from Eq. (33) and thus are not slightly shifted g-modes. For these other modes, the presence of stratification, which has the effect of shifting resonant peaks (compared to neutrally stratified studies), does not allow clear comparison with any of the regular or singular inertial modes of Ogilvie (2013) or Astoul & Barker (2023). The next resonant peak corresponding to

is not straightforward since they cannot be predicted from Eq. (33) and thus are not slightly shifted g-modes. For these other modes, the presence of stratification, which has the effect of shifting resonant peaks (compared to neutrally stratified studies), does not allow clear comparison with any of the regular or singular inertial modes of Ogilvie (2013) or Astoul & Barker (2023). The next resonant peak corresponding to  seems to be a gravito-inertial mode as it has some mixed g-mode and inertial mode features and the n = 1 radial wavelength. This mode is still in the sub-inertial range

seems to be a gravito-inertial mode as it has some mixed g-mode and inertial mode features and the n = 1 radial wavelength. This mode is still in the sub-inertial range  where we expect to find equatorially trapped hyperbolic gravito-inertial modes (as described in Dintrans et al. 1999; Dintrans & Rieutord 2000; Mathis 2009). The higher frequency peaks with

where we expect to find equatorially trapped hyperbolic gravito-inertial modes (as described in Dintrans et al. 1999; Dintrans & Rieutord 2000; Mathis 2009). The higher frequency peaks with  (in the super-inertial regime) presumably belong to the elliptic gravito-inertial mode family, as described in the aforementioned studies.

(in the super-inertial regime) presumably belong to the elliptic gravito-inertial mode family, as described in the aforementioned studies.

|

Fig. 3. Kinetic energies of tidally excited fluid motions as functions of the tidal forcing frequency, |

We also compared the kinetic energy to the split formulation but without the forcing term, fN, in the heat equation; that is, only with ft, which we call inertial forcing (green line on Fig. 3). Some of the peaks linked to the stable stratification and g-modes cannot be seen anymore, are strongly mitigated (especially for low frequency), or change geometry completely as shown on the 1g mode (left panel of Fig. 4). Without it, it corresponds to having gravito-inertial modes with the gravity component only secondarily excited by the effective Coriolis forcing. For example, the mode at  is well recovered with only the effective Coriolis forcing although the amplitude is divided by two (right panel of Fig. 4 but at the frequency of the 1g mode the mode is completely different (left panel of Fig. 4).

is well recovered with only the effective Coriolis forcing although the amplitude is divided by two (right panel of Fig. 4 but at the frequency of the 1g mode the mode is completely different (left panel of Fig. 4).

|

Fig. 4. Comparison of two gravito-inertial modes along ϕ = 0 for the different formulations. The first mode, with |

For all the peaks below  , the kinetic energy for both formulations agrees within < 1%, but there are some differences with the full formulation as the amplitude of the velocity becomes lower in the split formulation for the tidal frequencies,

, the kinetic energy for both formulations agrees within < 1%, but there are some differences with the full formulation as the amplitude of the velocity becomes lower in the split formulation for the tidal frequencies,  , higher than the BV frequency. This means that some tidal response seems to not be captured by the split formalism when further away from the g-mode or gravito-inertial mode frequencies. In order to investigate this effect, we looked at the resonant mode for two different tidal forcing frequencies. For

, higher than the BV frequency. This means that some tidal response seems to not be captured by the split formalism when further away from the g-mode or gravito-inertial mode frequencies. In order to investigate this effect, we looked at the resonant mode for two different tidal forcing frequencies. For  , the gravito-inertial mode velocity is reproduced within 0.5% by the split formulation (two upper left panels of Fig. 4). We can also see the impact of the rotation, which makes the mode more cylindrical than the spherical symmetry of pure g-modes. For

, the gravito-inertial mode velocity is reproduced within 0.5% by the split formulation (two upper left panels of Fig. 4). We can also see the impact of the rotation, which makes the mode more cylindrical than the spherical symmetry of pure g-modes. For  , the toroidal velocity is not exactly reproduced by the split formalism, and the kinetic energy seems to decrease with increasing tidal frequency, since we left the allowed frequency range for gravito-inertial waves to be excited, and the equilibrium tide is no longer negligible. This behavior can be explained by differences in the boundary conditions. Indeed, when outside of the resonant peaks, the amplitude of the equilibrium tide ue cannot be neglected compared to those of the dynamical tide u. This leads to a difference in boundary conditions as the full formulation solves the equations for both tides u + ue, while the split formulation solves the equation for the dynamical tide u. In order to compare the two formalisms, we artificially accounted for the impact of the equilibrium tide by changing our boundary conditions for the viscous rate tensor to τν, rθ(u) = − τν, rθ(ue) and τν, rϕ(u) = − τν, rϕ(ue). Applying these changes, we recovered the results from the full formulation within < 0.05% (Fig. 5).

, the toroidal velocity is not exactly reproduced by the split formalism, and the kinetic energy seems to decrease with increasing tidal frequency, since we left the allowed frequency range for gravito-inertial waves to be excited, and the equilibrium tide is no longer negligible. This behavior can be explained by differences in the boundary conditions. Indeed, when outside of the resonant peaks, the amplitude of the equilibrium tide ue cannot be neglected compared to those of the dynamical tide u. This leads to a difference in boundary conditions as the full formulation solves the equations for both tides u + ue, while the split formulation solves the equation for the dynamical tide u. In order to compare the two formalisms, we artificially accounted for the impact of the equilibrium tide by changing our boundary conditions for the viscous rate tensor to τν, rθ(u) = − τν, rθ(ue) and τν, rϕ(u) = − τν, rϕ(ue). Applying these changes, we recovered the results from the full formulation within < 0.05% (Fig. 5).

|

Fig. 5. Toroidal velocity, uϕ, with |

Since the split formulation has two effective forcing terms, ft and fN, we can compute the power associated with both to assess their importance. Figure 6 shows the different components of the power of the forcings and the thermal and viscous dissipation due to the tidal flows. We first verified that the balance of Eq. (28) is verified and the error that depends on resolution is around 10−7%. For almost all the modes, the power of the forcing, fN, due to the advection of the buoyancy variable gradient dominates, which is expected since we are in the regime N > Ωs. For large Pr, this statement may be even more true since thermal dissipation will be less important. The power of the forcing fN also dominates at a resonant Rossby frequency  where the contribution of the effective Coriolis forcing is the strongest for negative frequencies and is around PCor ≈ 0.4Pbuoy. The only exception is of the gravito-inertial modes found for

where the contribution of the effective Coriolis forcing is the strongest for negative frequencies and is around PCor ≈ 0.4Pbuoy. The only exception is of the gravito-inertial modes found for  , described before. We also find that the power due to the Coriolis effective forcing ft alternates between negative and positive values, while the total power is always positive. This might be linked to the splitting due to rotation of the gravity modes m = ±2.

, described before. We also find that the power due to the Coriolis effective forcing ft alternates between negative and positive values, while the total power is always positive. This might be linked to the splitting due to rotation of the gravity modes m = ±2.

|

Fig. 6. Power and dissipation balance of the tidally excited fluid motions as a function of the tidal forcing frequency, |

The case of pure inertial modes with the effective body force ft has been well studied and therefore needs no testing. Overall, these tests show that the split formulation with the two forcing terms is able to obtain well the resonant gravito-inertial modes without having a free surface implemented, as long as the mode frequency is much smaller than ωd.

4. Nonlinear simulations of gravito-inertial modes

As the orbital separation a shrinks with time due to the emission of GWs, the tidal forcing frequency and amplitude increase, and nonlinear effects can start to be important for the dynamics of the resonance. In this section, we discuss how we tested and studied the importance of nonlinear effects for binary NSs. In particular, we look at the nonlinear saturation of the gravito-inertial modes (i.e., when the nonlinear simulation reaches an average steady state).

We implemented the split formulation in the code MagIC with the stress-free boundary conditions applied to the dynamical tide u, since it does not change results for resonant modes compared to stress-free boundary conditions applied to both equilibrium and dynamical tides. In a similar fashion to Astoul & Barker (2023), we also chose to neglect some nonlinear interactions between the equilibrium and dynamical tides. Indeed, our model uses a non-deformed spherical shell, which in the presence of mixed (equilibrium-dynamical) nonlinear terms would lead to a nonvanishing equilibrium tide at the surface ue ⋅ n ≠ 0. In this case, the advection of the dynamical flow by the equilibrium flow can artificially generate angular momentum and spin up the star. We, therefore, neglected this advection term to avoid this setup artifact and because it is justified in the astrophysical regime (see discussion of Astoul & Barker 2022). For the saturation of the flow, we only considered the nonlinear effects of the dynamical tide on itself (u ⋅ ∇)u. This can be justified in cases where mode wavelengths are much smaller than the radius of the cavity.

We used this implementation to run several simulations for a NS binary of two solar masses, adopting an initial rotation of Ωs = 100/π Hz to continue the comparison as in the previous section. One notable difference is that, in this section, the gradient of the buoyancy variable  is constant instead of the BV frequency for the sake of simplicity. The BV frequency in this case depends on the radius, and N(r) = Nr and g = gor. This leads the linear g-modes to have smaller amplitudes and smaller resonant frequencies compared to the pure g-modes case shown in Sect. 3.1 with constant BV frequency.

is constant instead of the BV frequency for the sake of simplicity. The BV frequency in this case depends on the radius, and N(r) = Nr and g = gor. This leads the linear g-modes to have smaller amplitudes and smaller resonant frequencies compared to the pure g-modes case shown in Sect. 3.1 with constant BV frequency.

For the amplitude of the tidal force, we chose the tidal parameter to reflect the situation of having  so as to study the resonance of gravito-inertial modes, which gives a tidal amplitude of Ct ≈ 10−3 for N = 102.87 Hz, Ωs = 100/π Hz, and ωd = N/0.0450. In order to investigate differences in nonlinear effects between the different modes, we kept the tidal amplitude constant for all simulations in this section. Note that we would have

so as to study the resonance of gravito-inertial modes, which gives a tidal amplitude of Ct ≈ 10−3 for N = 102.87 Hz, Ωs = 100/π Hz, and ωd = N/0.0450. In order to investigate differences in nonlinear effects between the different modes, we kept the tidal amplitude constant for all simulations in this section. Note that we would have  (neglecting the real part of the Love number) in the realistic case (see Sect. 5).

(neglecting the real part of the Love number) in the realistic case (see Sect. 5).

4.1. Linear and nonlinear comparison

To be confident in our nonlinear simulations, we first compared the MagIC simulation results to the linear results. We ran the linear code for ![$ \hat{\omega} \in [-2\Omega_s,2 N] $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa54890-25/aa54890-25-eq89.gif) with a frequency resolution Nfreq = 500, while Nfreq = 100 for the nonlinear simulations. Figure 7 shows the total kinetic energy of the different modes for both the linear code and the nonlinear code MagIC. Overall, we find a good agreement between the two codes for many resonant modes, and the comparison of one of these cases can be seen for the structure and amplitude of the 3g mode (first mark furthest to the left on Fig. 7) in Fig. 8. The mode is deformed by rotation and becomes more cylindrical compared to a pure g-mode (see left panels of Fig. 2 for a pure g-mode at a different frequency). We still notice small differences for some resonance modes, but such effects may stem from the two different frequency resolutions or due to small nonlinear effects.

with a frequency resolution Nfreq = 500, while Nfreq = 100 for the nonlinear simulations. Figure 7 shows the total kinetic energy of the different modes for both the linear code and the nonlinear code MagIC. Overall, we find a good agreement between the two codes for many resonant modes, and the comparison of one of these cases can be seen for the structure and amplitude of the 3g mode (first mark furthest to the left on Fig. 7) in Fig. 8. The mode is deformed by rotation and becomes more cylindrical compared to a pure g-mode (see left panels of Fig. 2 for a pure g-mode at a different frequency). We still notice small differences for some resonance modes, but such effects may stem from the two different frequency resolutions or due to small nonlinear effects.

|

Fig. 7. Kinetic energy along the tidal frequency, |

|

Fig. 8. 3g-mode resonance with |

To quantify the importance of nonlinear effects, Fig. 7 shows the ratio of the axisymmetric-to-total kinetic energy in these simulations. It clearly shows that with the strongest resonance modes, a m = 0 zonal flow component emerges in addition to the forced m = 2 component. This means that nonlinear effects are stronger for these modes. It is not the only criterion, though, as the 2g22 mode has the highest percentage of axisymmetric energy, while the 1g22 mode has the highest mode energy.

4.2. Nonlinear saturation

The previous section showed that for Ct = 10−3, the nonlinear saturation of the kinetic energy matches the linear one. In this section, we examine this assumption to see if it still holds for the strongest resonances. Since nonlinear effects could become important, we also compare the linear and nonlinear simulations for cases with the highest percentage of axisymmetric energy and the highest absolute axisymmetric energy. They correspond to the 2g- and 1g-modes, as discussed above. We first checked that in the case of Ct = 10−9, the kinetic energy of both nonlinear simulations agrees with the associated linear simulations within a relative error < 10−6. Figure 9 compares the time evolution of the nonlinear simulations and the saturated energies predicted by the linear calculations for both modes. We find that the non-axisymmetric energy of the 2g-mode agrees well with the linear kinetic energy. We note that its total saturation is slightly increased by the axisymmetric energy, which is 10% of the total energy. In the case of the 1g-mode, the nonlinear saturation is lower by a factor of 3. This means that the saturation mechanism differs from the linear theory for this mode. It is possible that we only see it for this mode due to it having the strongest amplitude.

|

Fig. 9. Time evolution of the kinetic energy for the nonlinear simulations of 1g and 2g modes compared to the linear results (dashed red lines). The lines above correspond to the 1g mode with |

Figure 10 compares the non-axisymmetric and axisymmetric toroidal velocity of the two modes to see the impact of the nonlinear saturation. We find that axisymmetric rotation, decreasing with cylindrical radius, is generated for both modes. We expect that the differential rotation emerges due to nonlinear processes such as tidal wave-wave interactions (m = 2 and m = −2 nonlinear coupling to form an m = 0 mode, as explained in Barik et al. 2018; Astoul & Barker 2022, for inertial waves) and/or wave breaking as in Barker & Ogilvie (2010) in a 2D cylindrical geometry, Barker (2011) in a 3D box, and Guo et al. (2023) in a 2D circular cavity (see also, e.g., Semin et al. 2016, for experimental generation of a mean flow by internal gravity waves). In the latter, the geometrical focusing of gravity waves launched from the surface toward the center generates differential rotation from inside out by wave breaking (or weak linear damping) of (subcritical) waves and their progressive deposition of angular momentum. Wave breaking is observed when the amplitude of the wave is high enough to overturn the stratification (Barker & Ogilvie 2010; Barker 2011). We therefore applied the following criterion with the radial displacement, ξr, and wavenumber, kr, described in the aforementioned papers for wave breaking to our simulations:

|

Fig. 10. Strongest two g-mode resonances and their nonlinear saturation in the case of small rotation (N/Ωs = 3.24). Non-axisymmetric (left) and axisymmetric (right) toroidal velocity uϕ for the 2g mode (Panel a) and for the 1g mode (Panel b). |

We find that the wave is not strong enough to have wave breaking in these simulations. The presence of both Coriolis and buoyancy forces promotes a mix between cylindrical and spherical geometry of the mean flow (which is reminiscent of latitudinal differential rotation produced in Fig. 6 of Barker 2011). In proportion to the amplitude, the differential rotation is stronger for the 2g-mode.

The emergence of differential rotation supports our hypothesis for the resonant mixed gravito-inertial modes to be able to amplify some ambient magnetic field through winding in a way that is qualitatively similar to that studied by Astoul & Barker (2025). In future work, these results should be checked for different BV frequencies that are more realistic for astrophysical sources to assess the impact of the differential rotation amplitude.

5. An astrophysical application: Gravito-inertial modes in a neutron star binary

Depending on the stellar spin, the eigenfrequencies of gravito-inertial modes imply that they may become resonant some seconds prior to merger in a binary neutron-star inspiral. Because of their polar character, the leading-order overlap integrals and hence amplitudes may also be sizeable. These aspects together indicate that these modes may be important in the description of mergers for a few reasons:

-

A leading theory for explaining the ignition of GRB precursor flares, seen in ≲5% of mergers (Coppin et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2020), is that of crustal failure: resonant modes exert strain on the ion lattice defining the crust, which may exceed its elastic maximum if the mode amplitudes are large enough. Such an overstraining relieves the star of some magnetoelastic energy, which can fuel a gamma-ray flash (Tsang et al. 2012). Previous estimates using a linear, general-relativistic (GR) framework (Passamonti et al. 2021; Kuan et al. 2021b; Suvorov et al. 2022) found that some g-modes may exceed modern estimates for polycrystal strain maxima (Baiko & Chugunov 2018; Baiko 2024); a direct comparison is made with our nonlinear models in Sect. 5.1.

-

Energy may be siphoned from the orbit into the kinetic energy of the modes, leading to GW dephasing. Linear theory predicts that while the dephasing due to gravity(-inertial) modes is unlikely to be visible to current interferometers, it may be relevant for next-generation ones (Ho & Andersson 2023, see also Suvorov et al. 2024b). In general, however, we expect that treating mode excitations via nonlinear perturbation theory would favor measurability since amplitudes in post-resonance regimes do not remain constant as in linear theory (Yu et al. 2024; Kwon et al. 2024, 2025). In addition, the onset of GW dephasing depends on the resonance timing, which can differ between linear and nonlinear models, as explored in Sect. 5.1. Deducing their nonlinear saturation amplitudes is a necessary step toward providing realistic assessments of dephasing; such a comparison is made in Sect. 5.2.

-

Observations of nonthermal GRB precursors and other aspects (see, e.g., Xiao et al. 2024) hint that some magnetar-like objects participate in a rare subclass of mergers. This is difficult to reconcile with the fact that Ohmic decay times are thought to be much shorter than a characteristic inspiral time (e.g., Pons & Viganò 2019). One solution is that actually strong fields are not preserved but rather generated prior to coalescence by a mode-driven dynamo, as suggested by Suvorov et al. (2024a). The validity of this scenario depends on microphysical specifics as well as the mode properties; some MHD aspects of this in the context of the simulations presented here are discussed in Sect. 5.2.2.

In this section, we return to a closer examination of the astrophysical elements of a NS binary. Accordingly, we changed our model and considered a more standard NS of 1.6 M⊙, anticipating that for objects with non-negligible spin, some prior epoch of accretion may have increased the birth value. We adopted a radial profile for the BV frequency inspired by a realistic model of the NS from Suvorov et al. (2024a). We neglected (physical) discontinuities arising in the BV frequency in our “crustal cavity” due to different layers of nuclear composition, as the results were very likely to change with density variations between the core and the crust. The study of core-crust interfacial modes (i.e., i-modes; Tsang et al. 2012) due to these discontinuities is left to future studies. In Fig. 11 we show the smoothed BV frequency: it is visually identical to that predicted by the GR calculations except in the crust. The other main difference in our nonlinear simulations from the linear calculations in Suvorov et al. (2024a) would be that the density is still kept constant, as we first aimed at understanding nonlinear effects in a simpler setup.

|

Fig. 11. BV frequency for a 1.6 M⊙ NS with the APR4 EOS, giving a radius of Ro = 11 km from Suvorov et al. (2024a). The orange line is the profile that is used in the Newtonian simulations presented here (see main text for details). For reference, we overlay the BV frequency of the setup in Sect. 4 (dashed line). |

5.1. Comparison to GR linear calculations

First, before treating rotation self-consistently, we directly compared GR linear calculations to our linear ones to estimate the impact of our numerical hypotheses. To compute these modes, we used a radius ratio of α = 0.1 and the smooth BV profile from Fig. 11. As it turns out, the agreement is encouraging: the resonant frequencies are only slightly shifted to lower or higher values by 3.5% and 2.3% for the 2g and 1g modes, respectively.

The radial eigenfunctions between the two also agree well until a radius of ≈0.8 Ro, where the impact of the density gradient and, subsequently, the discontinuities become more important (see Fig. 12 for the case of uϕ, which corresponds to uϕ in GR calculations). In terms of amplitudes, the Newtonian 1g and 2g modes are rescaled by a factor of ∼0.02 and ∼0.0175 for the radial profiles to match, respectively. This rescaling is due to the way the linear modes are computed: in the GR case, the resulting mode amplitude is determined by the resonance time window, while, in the Newtonian case, the mode amplitude is determined by the balance between the tidal power and the dissipation through the diffusivities. The rough agreement between the rescaling factors shows that the results from the Newtonian case in the core are consistent with the GR linear calculations. We can therefore use the smooth BV frequency to study the resonant modes and their nonlinear saturation. However, the results will be mostly relevant to core-like regions of the NS, and a proper treatment of the density and BV discontinuities is required to study quantitatively the modes in the crust.

|

Fig. 12. Toroidal velocity for 1g22 and 2g22 modes. Solid lines represent the cases as those in Fig. 1 of Suvorov et al. (2024a). |

5.2. Nonlinear saturation of the strongest resonance

In this section, we show how we tested the impact of rotation on the 1g and 2g modes that generated the strongest nonlinear differential rotation in Sect. 4.2. We first began with the 2g mode as it has the lowest mode amplitude. Thus, nonlinear effects were expected to be smaller, and we therefore considered three different rotation rates, Ωs ∈ [0, 100/π, 100] Hz (i.e., astrophysically corresponding to irrotational, moderate, or “recycled” objects). To keep the viscosity the same as previous simulations, the same Rayleigh number Ra was maintained, but the Ekman number varied from Ek = 6.2 × 10−5 to Ek = 1.99 × 10−5 in the slow and fast rotating cases (note that the Ekman number is not defined for Ωs = 0.0). With the new BV profile, which is normalized at the outer boundary, the Rayleigh number is now Ra = −5.1 × 1010. For the same tidal forcing frequency, the orbital frequency Ωo is effectively higher since the spin of the NS is increased, and we thus obtain a larger tidal amplitude parameter, ϵ. Our strategy is to first use the linear code to compute the resonant frequencies, which is then fed into the nonlinear code to compute the saturation amplitudes. As one of our motivations is to investigate the strength of the magnetic field that could be theoretically generated by differential rotation, energies are shown in ergs and compared to the strength of a magnetic field that would have the same energy as the flow kinetic energy. This comparison is done by using the energy of a uniform 1014 G magnetic field, ![$ E_{B14}= \frac{1}{8\pi} \left[(10^{14}\,\mathrm{G})^2 \mathrm{V}\right] = 2.27 \times 10^{45} $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa54890-25/aa54890-25-eq95.gif) erg, where

erg, where  is the volume of the domain.

is the volume of the domain.

5.2.1. 2g mode

We first describe the 2g mode for different rotation rates, Ωs ∈ [0, 100/π, 100] Hz. For these spins, the tidal forcing frequencies of the 2g mode are respectively ![$ \hat{\omega}/N \in [0.146, 0.132, 0.127] $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/12/aa54890-25/aa54890-25-eq97.gif) , while the tidal dimensionless amplitudes are Ct = 9.3 × 10−4 and Ct = 4.1 × 10−3 for the two rotating cases. In order to compare the efficiency of the nonlinearities in the nonrotating case, we manually adjusted the tidal amplitude in the nonrotating case to the fast rotating case, namely Ct = 4.1 × 10−3 instead of the realistic one Ct = 5.29 × 10−4. This allows us to effectively mimic nonlinear effects at lower viscosities since the amplitude of the resonant modes increases with decreasing viscosity (in the linear regime, e.g., Ogilvie 2009; Pontin et al. 2023). Figure 13 shows the time evolution of the different kinetic energies, which for all simulations would be enough to generate a magnetic field stronger than 1014 G if we assume that this kinetic energy would be subdivided through dynamical means into equal parts kinetic and magnetic energy (equipartition). We see that nonlinearities become relevant for both modes after less than 1 s of evolution. The nonlinearities for the 2g mode and their impact are mostly seen in the toroidal kinetic energy, which is expected physically as zonal flows mainly develop in the azimuthal direction. For Ωs = 100/π Hz, the poloidal kinetic energy dominates and nonlinear effects are weaker than in the other case due to the lower tidal amplitude. We find that the axisymmetric energy represents ∼20% of the total kinetic energy. This is higher than but still consistent with the results of the previous section. For a faster star with Ωs = 100 Hz, the toroidal component becomes dominant and the axisymmetric kinetic energy is comparable to the non-axisymmetric energy, representing ∼50% of the total energy.

, while the tidal dimensionless amplitudes are Ct = 9.3 × 10−4 and Ct = 4.1 × 10−3 for the two rotating cases. In order to compare the efficiency of the nonlinearities in the nonrotating case, we manually adjusted the tidal amplitude in the nonrotating case to the fast rotating case, namely Ct = 4.1 × 10−3 instead of the realistic one Ct = 5.29 × 10−4. This allows us to effectively mimic nonlinear effects at lower viscosities since the amplitude of the resonant modes increases with decreasing viscosity (in the linear regime, e.g., Ogilvie 2009; Pontin et al. 2023). Figure 13 shows the time evolution of the different kinetic energies, which for all simulations would be enough to generate a magnetic field stronger than 1014 G if we assume that this kinetic energy would be subdivided through dynamical means into equal parts kinetic and magnetic energy (equipartition). We see that nonlinearities become relevant for both modes after less than 1 s of evolution. The nonlinearities for the 2g mode and their impact are mostly seen in the toroidal kinetic energy, which is expected physically as zonal flows mainly develop in the azimuthal direction. For Ωs = 100/π Hz, the poloidal kinetic energy dominates and nonlinear effects are weaker than in the other case due to the lower tidal amplitude. We find that the axisymmetric energy represents ∼20% of the total kinetic energy. This is higher than but still consistent with the results of the previous section. For a faster star with Ωs = 100 Hz, the toroidal component becomes dominant and the axisymmetric kinetic energy is comparable to the non-axisymmetric energy, representing ∼50% of the total energy.

|

Fig. 13. Time evolution of the kinetic energy for the 2g mode for Ωs = 100/π Hz, (top), Ωs = 100 Hz (middle), and Ωs = 0 with an increased tidal amplitude (bottom). |

To understand whether this increase is due to rotation or the tidal amplitude, we compare it to the nonrotating case with the same tidal amplitude. We find a striking difference for Ωs = 0: the nonlinear effects become important much faster, and the axisymmetric toroidal velocity becomes dominant after 1 s. The toroidal kinetic energy saturates at a higher level compared to the other two rotating cases. This different evolution may be due to the fact that the amplitude of linear g-modes also saturates at greater values with lower rotation because of overlap integral properties (see Fig. 6 of Pontin et al. 2024). For a given tidal amplitude, the nonlinear effects are therefore more important with lower rotation, which is what we observe in our simulations.

To compare the nonlinear effects for the three cases in more detail, we look at the kinetic energy spectra along degrees, ℓ, and orders, m. The m = 2 mode would dominate for purely linear solutions, and the ℓ = 2 mode should dominate for pure g-modes as the different ℓ modes are only coupled by the Coriolis force. Note that ℓ = 2 is also dominant for linear inertial waves because the tidal potential has a ℓ = 2 geometry. In addition, we expect to have even ℓ modes dominating for the poloidal field and odd ℓ modes for the toroidal field due to the equatorial plane symmetry of the equilibrium tide used for the effective forcing, assuming this persists nonlinearly. We see these behaviors in the spectrum depending on the ℓ modes of the two rotating cases and, to a lesser extent, in the nonrotating case too (left panels of Fig. 14). As nonlinear effects become more important (i.e., at larger tidal amplitudes), the spectrum gets extended to higher degrees ℓ.

|

Fig. 14. Kinetic energy spectra of the 2g-mode resonance for Ωs = 100/π Hz, (top), Ωs = 100 Hz (middle), and Ωs = 0 with an increased tidal amplitude (bottom). The left panels denote kinetic energy integrated over r and m, while varying ℓ; and the right panels are integrated over r and ℓ, while varying m. The kinetic energy is in viscous units. The tidal amplitude is Ct = 9.3 × 10−4 in Panel a, Ct = 4.1 × 10−3 in Panel b and in Panel c. |

For the spectrum along order m, we see that the m = 2 and the m = 0 modes dominate for the poloidal component and for the toroidal component, respectively (right panels of Fig. 14). We also see that odd orders m are nonrelevant for the rotating cases and only start to become relevant for the nonrotating case with the strongest nonlinear effects, while remaining below even modes. We see that the amplitude of the toroidal mode m = 0 becomes more and more dominant as the tidal amplitude increases, which is consistent with the ratio of axisymmetric energy in the time evolution. The m = 0 mode of the poloidal component stays much lower than the m = 2 mode.

To confirm the importance of the m = 0 mode of the velocities, we show snapshots of ur and uϕ in the equatorial plane for the three different cases in Fig. 15. In the rotating cases, we see that the modes are quite similar: for ur, the differences between the maximum amplitude of the dominant m = 2 mode are within 30%, and there is only a small difference in geometry close to the equatorial plane (not shown here). There are more differences for uϕ as its amplitude increases with rotation and tidal amplitude. The increase in the axisymmetric component with tidal amplitude can also be seen as the negative amplitude close to the inner core neighbors zero in the fast rotating case. In a similar fashion, the difference between positive and negative amplitudes of uϕ close to the outer boundary is lower in the fast rotating case. This means that the inner region is spun up and the outer region is instead spun down for this particular resonance.

|

Fig. 15. Velocity flows (in CGS units), ur (left) and uϕ (right), of the gravito-inertial 2g mode in the equatorial plane for Ωs = 100/π Hz (top), Ωs = 100 Hz (middle), and Ωs = 0 with an increased tidal amplitude (bottom). The tidal amplitude is Ct = 9.3 × 10−4 in Panel a, Ct = 4.1 × 10−3 in Panel b and in Panel c. |

The nonrotating case is both qualitatively and quantitatively different as compared to the rotating cases: for ur, the m = 2 mode is still dominant but the number of radial nodes is increased, especially in the inner region, and the amplitude is lower by a factor of ∼5. For uϕ, the m = 0 mode is dominant with the addition of “spiral arms” that appear similar to a superposition of m = 2 and m = 1 modes (and/or traveling waves). The amplitude of uϕ is also ∼4 times stronger compared to the rotating cases. This strong spin-up in the inner region might explain why different radial modes are excited for this nonrotating case. Indeed, the spin-up leads to a rotation rate of Ωs,spin−up ≈ 20 Hz, which would modify the tidal forcing frequency from  to