| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A279 | |

| Number of page(s) | 16 | |

| Section | Planets, planetary systems, and small bodies | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555989 | |

| Published online | 19 February 2026 | |

Self-gravity in thin protoplanetary discs

I. The smoothing-length approximation versus the exact self-gravity Kernel

1

Leibniz-Institut für Astrophysik Potsdam (AIP),

An der Sternwarte 16,

14482

Potsdam,

Germany

2

Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik, Zentrum für Astronomie (ZAH), Universität Heidelberg,

Albert-Ueberle-Str. 2,

69120

Heidelberg,

Germany

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

17

June

2025

Accepted:

30

November

2025

Context. Planet-forming discs are increasingly found to harbour internal structures such as spiral arms. The origin and evolution of these is often associated with the disc’s own gravitational force. When investigating discs using a 2D approximation, it is common to employ an ad hoc softening prescription for self-gravity. However, this approach ignores how the vertical structure of the disc is affected by the mass distribution of gas and dust. More significantly, it suppresses the Newtonian nature of gravity at short distances and does not respect Newton’s third law.

Aims. To overcome the inherent issues associated with approximate descriptions – for instance, a Plummer potential – we aim to derive an exact self-gravity kernel designed for hydrostatically supported thin discs, which moreover incorporates a potential dust fluid component embedded in the gas.

Methods. We develop an analytical framework to derive an exact 2D self-gravity prescription suitable for modelling thin discs. The validity and consistency of the proposed kernel is then supported by analytical benchmarks and both 2D and 3D numerical tests.

Results. We derive the exact 2D self-gravity kernel valid for Gaussian-stratified thin discs. This kernel is built upon exponentially scaled modified Bessel functions and simultaneously adheres to all the expected features of Newtonian gravitation – including point-wise symmetry, a smooth transition from light to massive discs, and a singularity for vanishing distances. Quite remarkably, the kernel displays a purely 2D nature at short distances, while transitioning to a fully 3D behaviour at longer distances. In contrast to other prescriptions found in the literature, it proves capable of leading to an additional, and previously unnoticed, source of gravitational runaway discernible only at infinitesimal distances. We finally note that our new prescription remains compatible with methods based on the fast Fourier transform, affording superior computational efficiency.

Conclusions. Our exact kernel formulation overcomes substantial limitations inherent in the smoothing-length approach. It permits a novel, fully consistent treatment of self-gravity in Gaussian-stratified thin discs. The approach, which makes the usage of the Plummer potential obsolete, will prove useful for studying all common planet formation scenarios, which are often backed by 2D flat numerical simulations. Accordingly, in an accompanying paper we shall investigate how the occurrence of the gravitational instability is affected.

Key words: accretion, accretion disks / gravitation / hydrodynamics / methods: analytical / methods: numerical / protoplanetary disks

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

With the current advancements in numerical capabilities and optimised codes, conducting complex simulations of physical processes within protoplanetary discs (PPDs) has become routine. Despite the increased computational power, high-resolution 3D simulations present practical challenges such as data storage, analysis, or visualisation that remain unresolved. More significantly, they remain computationally challenging, necessitating a resolution trade-off across the three spatial directions. As a result, when studying discs numerically, one of the common approaches involves employing a 2D approximation, which neglects the vertical dimension, and hence offers a significant gain of resolution in the (r, ϕ) plane. In particular, this approximation allows one to conduct sufficiently resolved global simulations including the gravitational force of the disc exerted onto itself, commonly referred as self-gravity (SG).

Deriving the ‘correct’ approximation for the effective gravity in a 2D disc is a subtle and tedious problem that requires one to first define what is meant by 2D approximation. As an extreme case, this could mean living in a ‘2D Universe’, which implies that the laws of nature are fundamentally different from our 3D space; that is, the gravitational field generated by a point mass scales as ∝1/r (Landy 1996). Of course, this does not apply in the case of discs, as they are objects embedded within a 3D space. But based on theoretical expectations, and supported by PPD observations (Pinte et al. 2016), cataclysmic variable accretion discs (Baptista et al. 2016), and galactic discs (Hu & Peng 2014; van Dokkum et al. 2019), we expect discs to have low geometrical aspect ratios. This justifies the flat, or razor-thin, disc assumption for the density vertical profile, which adopts a Dirac δ distribution. In the particular case of axisymmetric discs, this assumption permits one to derive the gravitational potential in the equatorial plane. For instance, this could be achieved by means of a continuous overlap of infinitely flattened homoeoid shells (Binney & Tremaine 2008, Sects. 2.5.1 and 2.6) or through direct integration, resulting in a closed form for the associated potential (Durand 1953; Huré & Hersant 2007; Huré et al. 2008). Although almost flat, PPDs are inherently 3D structures, yet due to computational limitations or for the sake of analytical simplicity, the oversimplified Dirac profile assumption is often made. To eliminate this limitation, the other approach, which we endorse in this paper, consists of averaging vertically the 3D SG force in a thin disc (Li et al. 2009; Müller et al. 2012; Rendon Restrepo & Barge 2023). As a result the obtained 2D force, meant to act in the midplane, encapsulates on average all information from the vertical structure of the disc. We emphasise that the thin disc structure originates from the vertical hydrostatic equilibrium, which, in the simplest case, leads to a Gaussian profile (Armitage 2022).

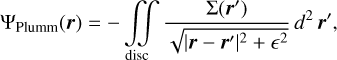

To account for the disc’s vertical thickness in the 2D SG calculation and to presumably avoid numerical singularities, the gravitational potential of a thin disc was often approximated by a Plummer potential1; that is,

(1)

where the smoothing length (SL), denoted as ε, was regarded during a considerable period of time as a free parameter. Over the years, several values have been proposed and theoretical findings have converged towards a softening length proportional to the disc’s scale height (Huré & Pierens 2009; Huré & Hersant 2011; Huré & Trova 2015). The prevailing value frequently used in numerical simulations is εg/Hg=0.6−1.2 (Müller et al. 2012). We highlight that Li et al. (2009) identified another prescription that does not utilise a softening prescription. However, it has received little attention, likely due to its apparent complexity and the lack of efficient, compatible numerical methods. In the latest work to date by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023), it was shown that while this widely used prescription correctly models the long-range SG interaction, it tends to underestimate the mid- and short-range interaction by up to 100% – a discrepancy that aligns with the removal of the Newtonian behaviour in the presence of softening (Adams et al. 1989; Hockney & Eastwood 2021; Baruteau & Masset 2008; Young & Clarke 2015). As a consequence, these authors introduced a space-varying smoothing length (SVSL), departing from the simple constant SL approach. This SVSL allows the 2D force to better fit the vertically averaged 3D counterpart. Further, they generalised their correction to bi-fluids; that is, the case in which a dust phase is embedded in the gas. They found that two additional SLs are required to account for the gravitational interactions of dust with dust and the crosswise interaction of dust with gas. This could be of great importance, since the low levels of turbulence in the vertical direction – supported both by observations of thin dust layers (Villenave et al. 2020, 2022) and by 3D shearing box simulations (Baehr & Zhu 2021) – may suggest that dust SG is comparable to the SG of gas at small scales.

(1)

where the smoothing length (SL), denoted as ε, was regarded during a considerable period of time as a free parameter. Over the years, several values have been proposed and theoretical findings have converged towards a softening length proportional to the disc’s scale height (Huré & Pierens 2009; Huré & Hersant 2011; Huré & Trova 2015). The prevailing value frequently used in numerical simulations is εg/Hg=0.6−1.2 (Müller et al. 2012). We highlight that Li et al. (2009) identified another prescription that does not utilise a softening prescription. However, it has received little attention, likely due to its apparent complexity and the lack of efficient, compatible numerical methods. In the latest work to date by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023), it was shown that while this widely used prescription correctly models the long-range SG interaction, it tends to underestimate the mid- and short-range interaction by up to 100% – a discrepancy that aligns with the removal of the Newtonian behaviour in the presence of softening (Adams et al. 1989; Hockney & Eastwood 2021; Baruteau & Masset 2008; Young & Clarke 2015). As a consequence, these authors introduced a space-varying smoothing length (SVSL), departing from the simple constant SL approach. This SVSL allows the 2D force to better fit the vertically averaged 3D counterpart. Further, they generalised their correction to bi-fluids; that is, the case in which a dust phase is embedded in the gas. They found that two additional SLs are required to account for the gravitational interactions of dust with dust and the crosswise interaction of dust with gas. This could be of great importance, since the low levels of turbulence in the vertical direction – supported both by observations of thin dust layers (Villenave et al. 2020, 2022) and by 3D shearing box simulations (Baehr & Zhu 2021) – may suggest that dust SG is comparable to the SG of gas at small scales.

Even if Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023) solved the main issue with their new prescription, they nonetheless used a number of mathematical simplifications that are debatable. In particular, they assumed that the relative scale heights between component a and b, expressed via ηab=Ha(r′)/Hb(r), are constant over the 2D disc. This, however, breaks the r/r′ symmetry in the SG force. This symmetry breaking results in a spurious radial acceleration, which needs to be compensated for (Baruteau 2008; Rometsch et al. 2024). Furthermore, the authors disregarded the effect of SG on the vertical direction, which could significantly affect the layering of the disc (Bertin & Lodato 1999; Lodato 2007), and thus also indirectly the 2D SG force. As a consequence, Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023) prescription is only valid for comparatively light discs, whose Toomre’s parameter satisfies Qg ≳ 5, and cannot be used self-consistently in simulations of gravitational instability (GI) in which Toomre’s parameter is expected to reach values smaller than unity (Gammie 2001; Takahashi et al. 2016; Baehr et al. 2017; Béthune et al. 2021). In a broader context, this could profoundly impact a broad range of planet formation scenarios, since at some point or another the SG force should come into play in maintaining the gravitational cohesion of the formed objects (Rendon Restrepo & Gressel 2023). Finally, the work of Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023) should be considered as a preliminary step in view of the dust stratification, since it was presumed to be Gaussian without further details being provided. This can be readily contradicted for strong SG of dust whereby the sedimentation follows a sech2−profile (Klahr & Schreiber 2020, 2021). Furthermore, the mentioned assumption disregards the gravitational contribution of the gas to the vertical layering. We conclude that all issues and ambiguities raised in this paragraph need to be corrected in order to conduct consistent 2D simulations of single or bi-fluids incorporating SG.

In this first paper of a series of two, we aim to provide an exact SG kernel that must be used in 2D global simulations of discs – a formulation that is valid from light to massive discs all at once. In the second accompanying paper, we study how this new kernel affects the GI planet formation scenario. We begin by recalling briefly the vertical stratification of self-gravitating, bi-fluid discs and provide the exact SG kernel in Section 2. Then, in Section 3, we highlight the relevance of this kernel and discuss how it possibly leads to a new runaway situation. In Section 4, we benchmark our kernel against well-established analytical results from thin disc literature and both 2D and 3D numerical tests. Finally, in Section 5 we propose a discussion of numerical methods, the limitations of our approach, the indirect term, and the consistency of the 2D Poisson equation. Important equations and derivations can be found in the appendices.

2 Self-gravity for two-phase discs

Estimating in-plane SG forces in thin discs involves a two-step process. The initial step, often overlooked, involves determining the vertical hydrostatic equilibrium of the system. The resulting stratification is subsequently used, in the final phase, as an input for vertically integrating all forces; including, in our specific case, SG.

Accordingly, in the next sections we recall the results of Rendon Restrepo et al. (2025) regarding the stratification of a bi-fluid disc and the key steps taken by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023) for computing SG in 2D, bi-fluid simulations of PPDs. Both results combined enable us to propose an exact SG kernel that works for a broad range of Toomre’s parameters, as well as a bi-fluid. At the same time, it frees us from the problems inherent in a Plummer potential. To enhance readability of this paper, we have compiled the definitions and abbreviations of the main quantities in Table 1.

2.1 The thin self-gravitating, bi-fluid disc

For simplicity, it is often assumed that the vertical structure of the gas and dust phases composing a PPD is set either by the balance between the star’s gravity and by pressure, or by viscous stirring, respectively. However, the vertical component of the disc’s SG should be included in this equilibrium and particularly when modelling class 0/I discs or the outskirts of PPDs where the SG force is predominant over the star’s gravity. This is most likely the case in the Elias 2-27 system (Pérez et al. 2016; Parker et al. 2022) and in IM Lupi and GM Aur (Lodato et al. 2023).

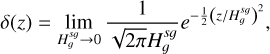

When the gravitational contribution of gas and dust are treated separately in massive discs, their respective layering are no longer Gaussian, but are set by a sech2 function (Spitzer 1942; Klahr & Schreiber 2020, 2021). Additionally, when the disc is solely composed of gas, it is possible to connect the stratification of light and massive discs using a ‘biased’ Gaussian stratification. Such an approach incorporates all SG information into a modified scale height dependent on Toomre’s parameter, as shown by Bertin & Lodato (1999). Rendon Restrepo et al. (2025) extended their work and showed that it is not possible to disentangle the contribution of gas and dust to SG, and proposed a very accurate and general solution valid for any SG strength, of gas and/or dust. At first order, their solution is

![$ \left\{\begin{array}{l} \rho_{g}(\boldsymbol{r}, z)=\frac{\Sigma_{g}}{\sqrt{2 \pi} H_{g}^{s g}} \exp \left[-\frac{1}{2}\left(z / H_{g}^{s g}\right)^{2}\right] \\ \rho_{d}(\boldsymbol{r}, z)=\frac{\Sigma_{d}}{\sqrt{2 \pi} H_{d}^{s g}} \exp \left[-\frac{1}{2}\left(z / H_{d}^{s g}\right)^{2}\right] \end{array},\right. $](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq4.png) (2)

with

(2)

with

![$ \left\{\begin{array}{ll} H_{g}^{s g} & =\sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}} H_{g} f\left(Q_{\mathrm{bi}-\mathrm{fluid}}\right) \\ H_{d}^{s g} & =\sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}} H_{d} f\left(Q_{\mathrm{bi}-\mathrm{fluid}}\right) \\ Q_{\mathrm{bi}-\mathrm{fluid}} & =\left(\frac{1}{Q_{g}}+\frac{1}{Q_{d}}\right)^{-1} \\ f(x) & =\frac{\pi}{4 x}\left[\sqrt{1+\frac{8 x^{2}}{\pi}}-1\right] \end{array},\right. $](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq5.png) (3)

where Hg is the thermal gas scale height and Hd is the dust diffusive scale height. The quantities

(3)

where Hg is the thermal gas scale height and Hd is the dust diffusive scale height. The quantities  and

and  are the Toomre’s parameter of gas and dust, respectively. The effective dust sound speed is cd. Meanwhile, the term f(Qbi-fluid), present in the definition of both scale heights, indicates that both fluids experience an equal gravitational influence from the star and from their combined mass distributions. Indeed, the crosswise gravity of both fluids is encapsulated by the general Toomre’s parameter, Qbi-fluid, defined as the harmonic average of its constituents. For a detailed discussion, we invite readers to refer to Rendon Restrepo et al. (2025). Contrary to the razor-thin disc assumption mentioned in the introduction, the approach discussed in this section is able to accommodate any vertical stratification for the gas and dust phases. For instance, in the case of uniquely dust, it could be applicable to systems with limited sedimentation (Lin et al. 2023) to high settling (Villenave et al. 2020, 2022). As we demonstrate in the following section, the vertical profiles exhibited in Eq. (2) can be elegantly exploited for obtaining the exact 2D SG force via a kernel description.

are the Toomre’s parameter of gas and dust, respectively. The effective dust sound speed is cd. Meanwhile, the term f(Qbi-fluid), present in the definition of both scale heights, indicates that both fluids experience an equal gravitational influence from the star and from their combined mass distributions. Indeed, the crosswise gravity of both fluids is encapsulated by the general Toomre’s parameter, Qbi-fluid, defined as the harmonic average of its constituents. For a detailed discussion, we invite readers to refer to Rendon Restrepo et al. (2025). Contrary to the razor-thin disc assumption mentioned in the introduction, the approach discussed in this section is able to accommodate any vertical stratification for the gas and dust phases. For instance, in the case of uniquely dust, it could be applicable to systems with limited sedimentation (Lin et al. 2023) to high settling (Villenave et al. 2020, 2022). As we demonstrate in the following section, the vertical profiles exhibited in Eq. (2) can be elegantly exploited for obtaining the exact 2D SG force via a kernel description.

Definitions and list of abbreviations.

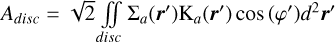

2.2 Exact self-gravity kernel

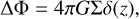

We consider two fluids (gas and dust) with the Gaussian vertical stratification defined by Eqs. (2)–(3). In 3D, the SG force per unit volume exerted by the PPD on gas and dust parcels are expressed as

![$ \begin{align*} & \boldsymbol{f}_{3 D}^{g, \text { tot }}(\boldsymbol{r}, z)=-\rho_{g}(\boldsymbol{r}, z)\left[\nabla \Phi_{g}+\nabla \Phi_{d}\right], \\ & \boldsymbol{f}_{3 D}^{d, \text { tot }}(\boldsymbol{r}, z)=-\rho_{d}(\boldsymbol{r}, z)\left[\nabla \Phi_{g}+\nabla \Phi_{d}\right], \end{align*} $](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq8.png) (4)

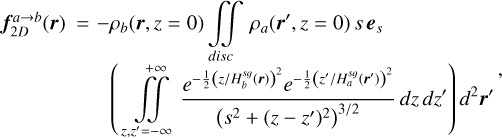

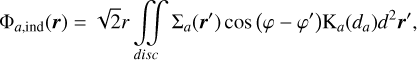

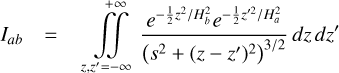

where Φg and Φd are the distinct gravitational potentials associated with the gas and dust discs, respectively. For the sake of generality and conciseness, we denote the two fluid phases as ‘a’ and ‘b’ for the remainder of the paper. The 2D SG force per unit volume exerted by the disc made of fluid ‘a’ on a volume element of fluid ‘b’ is (see Eq. (4) in (Rendon Restrepo & Barge 2023)):

(4)

where Φg and Φd are the distinct gravitational potentials associated with the gas and dust discs, respectively. For the sake of generality and conciseness, we denote the two fluid phases as ‘a’ and ‘b’ for the remainder of the paper. The 2D SG force per unit volume exerted by the disc made of fluid ‘a’ on a volume element of fluid ‘b’ is (see Eq. (4) in (Rendon Restrepo & Barge 2023)):

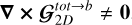

(5)

where s=|r−r′| stands for the separation between two fluid elements and es=(r−r′)/s is a unit vector in the 2D plane. We highlight that all variables linked to phase ‘a’ and ‘b’ are dependent on r′ and r positions, respectively. Hence, for the rest of the paper we skip all explicit dependencies on position, except when a distinction is necessary. We highlight that for a disc made of gas and dust, our naming convention leads to four possible combinations (a, b)={(gas, gas), (gas, dust), (dust, dust), (dust, gas)} for computing

(5)

where s=|r−r′| stands for the separation between two fluid elements and es=(r−r′)/s is a unit vector in the 2D plane. We highlight that all variables linked to phase ‘a’ and ‘b’ are dependent on r′ and r positions, respectively. Hence, for the rest of the paper we skip all explicit dependencies on position, except when a distinction is necessary. We highlight that for a disc made of gas and dust, our naming convention leads to four possible combinations (a, b)={(gas, gas), (gas, dust), (dust, dust), (dust, gas)} for computing  . With these clarifications, Eq. (5) can be rearranged in the following manner:

. With these clarifications, Eq. (5) can be rearranged in the following manner:

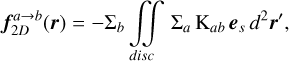

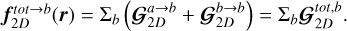

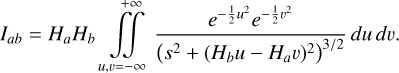

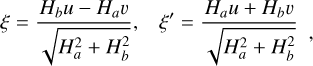

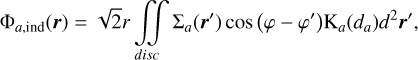

(6)

where

(6)

where

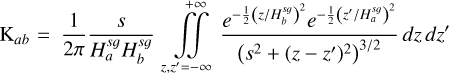

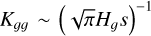

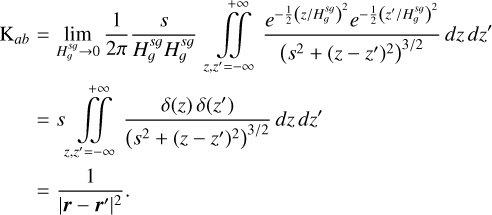

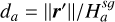

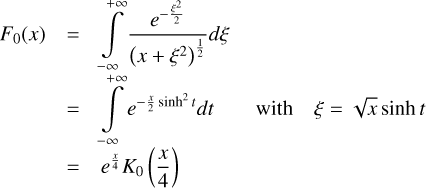

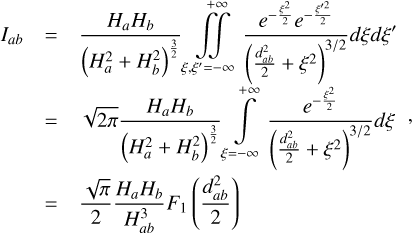

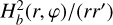

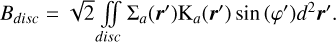

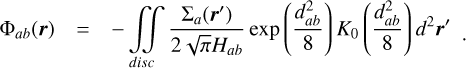

(7)

is the SG force kernel between fluids ‘a’ and ‘b’ 2. The column densities are Σi. Previously, Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023) attempted to provide an accurate approximation of the integral defined by Eq. (7) employing a SVSL, which, despite its accuracy, remains burdensome. In particular, it does not respect the r/r′ symmetry and is not valid in the regime where SG starts to become significant (i.e. Q ≲ 5). Luckily, when the vertical component of SG is disregarded, the double integral defining the SG force kernel can be assessed analytically (Li et al. 2009, Eqs. (20)–(22)) leading us to the derivation of the force kernel in the general case of a self-gravitating bi-fluid as seen below (see Appendices A and B for a detailed derivation):

(7)

is the SG force kernel between fluids ‘a’ and ‘b’ 2. The column densities are Σi. Previously, Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023) attempted to provide an accurate approximation of the integral defined by Eq. (7) employing a SVSL, which, despite its accuracy, remains burdensome. In particular, it does not respect the r/r′ symmetry and is not valid in the regime where SG starts to become significant (i.e. Q ≲ 5). Luckily, when the vertical component of SG is disregarded, the double integral defining the SG force kernel can be assessed analytically (Li et al. 2009, Eqs. (20)–(22)) leading us to the derivation of the force kernel in the general case of a self-gravitating bi-fluid as seen below (see Appendices A and B for a detailed derivation):

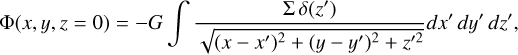

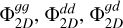

![$\mathrm{K}_{a b}=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi}}\left(H_{a b}^{s q}\right)^{-2} \frac{d_{a b}}{8} \exp \left(\frac{d_{a b}^{2}}{8}\right)\left[K_{1}\left(\frac{d_{a b}^{2}}{8}\right)-K_{0}\left(\frac{d_{a b}^{2}}{8}\right)\right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq13.png) (8)

where Kα are modified Bessel functions of the second kind and order α. The notation

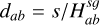

(8)

where Kα are modified Bessel functions of the second kind and order α. The notation  stands for the normalised distance between two fluid elements. The root mean square of

stands for the normalised distance between two fluid elements. The root mean square of  and

and  is defined by

is defined by

(9)

The above-mentioned distance Ha b not only combines the different fluids contribution to the scale height but also takes into account the different disc positions, r and r′. We highlight that the unique definition of the above root mean square (rms) scale height (Eq. (9)) permits one to lift the r/r′ symmetry issues associated with a 2D approximation, even when using the Plummer potential prescription. The symmetry issues are avoided because Newton’s third law is fulfilled as long as the force between two density columns is symmetric.

(9)

The above-mentioned distance Ha b not only combines the different fluids contribution to the scale height but also takes into account the different disc positions, r and r′. We highlight that the unique definition of the above root mean square (rms) scale height (Eq. (9)) permits one to lift the r/r′ symmetry issues associated with a 2D approximation, even when using the Plummer potential prescription. The symmetry issues are avoided because Newton’s third law is fulfilled as long as the force between two density columns is symmetric.

The closed form expressed in Eq. (8) offers several advantages over the one proposed by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023). Despite employing special mathematical functions, this formula remains both simple and general. Notably, there is no longer a necessity for the auxiliary functions (λ, δ) introduced when using a SVSL. Furthermore, Eq. (8) encompasses all mutual interactions between different phases embedded in a PPD. Finally, this new kernel formulation achieves the r/r′ position symmetry, implying Newton’s third law, as well as the interchangeability symmetry between fluid elements ‘a’ and ‘b’. All these aspects reassure us in the accurate representation of the 2D SG when employing our new kernel. We stress that our work differs from Li et al. (2009) due to the incorporation of the bi-fluid analysis (readily adaptable to N-fluids, see Sect. 5.2 for a discussion) and our consideration of how the SG of both components affects their vertical density profile. Indeed, in our investigation, the vertical component of SG is encapsulated in the definition of the revised scale height (Eq. (3)). We stress that these two last aspects are novel. The chosen approach makes our method similar to a 1 D+2 D problem, justified by the fact that the timescales of vertical settling are much smaller than the in-plane dynamic timescales. Further, we want to highlight that due to computational costs, Li et al. (2009) did not encourage to use the Bessel kernel but instead an interpolated formula. Presumably, they did not contemplate that fast Fourier transform (FFT) methods were still valid for such a prescription and that, under certain circumstances, the evaluation of the Bessel kernel is only done once for a whole simulation. This is regrettable because there are a lot of physical lessons to be drawn from their formula, which we explore in the next section.

3 Advantages associated with the Bessel kernel

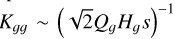

In this section, we explore the benefits of putting our prescription to use. To achieve this, we examine how it compares to other prescriptions from the literature, assess how SG is rescaled when considering a dust phase, and demonstrate that our kernel is the only one enabling a potential runaway process at infinitesimal distances.

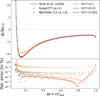

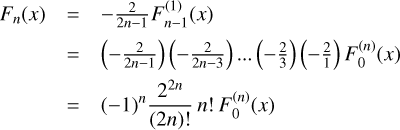

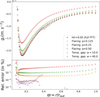

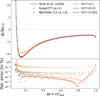

|

Fig. 1 Normalised SG kernels, |

3.1 Comparison with other kernels from the literature

In order to show the interest of our findings, we depicted in Fig. 1 a comparison between our Bessel kernel and the prescriptions suggested by Müller et al. (2012) and Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023). We remind that the first approach relies on a constant SL, which we set at ε/Hg ∈[0, 0.3, 1.2], three customary values in several numerical studies (Paardekooper et al. 2011; Young & Clarke 2015; Zhu & Baruteau 2016; Baruteau & Zhu 2016; Vorobyov & Elbakyan 2018). The second approach is intended for weak SG conditions, Qg ≳ 5, and employs a SVSL. For simplicity, this comparative study assumes a gas-only disc. To ensure finite values at the singularity (dg=0) we normalised the different kernels by  . In particular, the last factor allows us to account for modifications in the scale height due to SG whenever it is incorporated in the kernel’s prescription – as is the case only for our Bessel kernel. In top panel of Fig. 1, we compare the kernels designed for application in the weak SG regime, while the bottom panel shows the Bessel kernel applied to massive discs.

. In particular, the last factor allows us to account for modifications in the scale height due to SG whenever it is incorporated in the kernel’s prescription – as is the case only for our Bessel kernel. In top panel of Fig. 1, we compare the kernels designed for application in the weak SG regime, while the bottom panel shows the Bessel kernel applied to massive discs.

As was expected, our plots revealed similar behaviour among all kernels for the long-range interaction: dg ≳ 3 when the disc is light or dg ≳ 3 Qg when the disc is massive. Notably, all kernels scale as  for large distances, which respects the Newtonian behaviour. Conversely, all these prescriptions reveal distinct behaviours at short range, which we discuss next. First, we highlight that for a vanishing SL the kernel adopts an inverse square law at small distances, which highly overestimates SG. For the constant and non-vanishing SL, two scenarios arise. When the SL approaches zero (e.g. ε/Hg=0.3), the SG vanishes for small distances but is overestimated for dg ∈ [0.2, 3]. Conversely, larger SL (e.g. ε/Hg=1.2) necessarily underestimate SG for dg ∈ [0.2, 3]. This last limitation was corrected by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023) prescription, as their normalised kernel does not indeed vanish at the singularity, aligning more closely with expectations for gravitational interactions: the closer two bodies are, the stronger their mutual gravitational pull, a fundamental principle that must remain true even in the 2D approximation. However, this latter kernel is insensitive to the Toomre’s parameter of the disc, which is inconsistent. The Bessel kernel proposed in this work addresses this issue, as its value scales inversely with the Toomre’s parameter (bottom panel of Fig. 1), matching the expectation that SG strengthens in massive discs. Furthermore, it does not vanish at the singularity, a feature consistent with the nature of gravity. Finally, the Bessel kernel permits a smooth transition between light (Qg ≳ 5) and massive discs (Qg ≲ 1). These are expected features from a coherent 2D SG kernel. We also note that with the Bessel kernel, the effects of SG start to become appreciable when Qg ≲ 5. It is noticeable that for the short and long range interactions, the Bessel kernel scales as

for large distances, which respects the Newtonian behaviour. Conversely, all these prescriptions reveal distinct behaviours at short range, which we discuss next. First, we highlight that for a vanishing SL the kernel adopts an inverse square law at small distances, which highly overestimates SG. For the constant and non-vanishing SL, two scenarios arise. When the SL approaches zero (e.g. ε/Hg=0.3), the SG vanishes for small distances but is overestimated for dg ∈ [0.2, 3]. Conversely, larger SL (e.g. ε/Hg=1.2) necessarily underestimate SG for dg ∈ [0.2, 3]. This last limitation was corrected by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023) prescription, as their normalised kernel does not indeed vanish at the singularity, aligning more closely with expectations for gravitational interactions: the closer two bodies are, the stronger their mutual gravitational pull, a fundamental principle that must remain true even in the 2D approximation. However, this latter kernel is insensitive to the Toomre’s parameter of the disc, which is inconsistent. The Bessel kernel proposed in this work addresses this issue, as its value scales inversely with the Toomre’s parameter (bottom panel of Fig. 1), matching the expectation that SG strengthens in massive discs. Furthermore, it does not vanish at the singularity, a feature consistent with the nature of gravity. Finally, the Bessel kernel permits a smooth transition between light (Qg ≳ 5) and massive discs (Qg ≲ 1). These are expected features from a coherent 2D SG kernel. We also note that with the Bessel kernel, the effects of SG start to become appreciable when Qg ≲ 5. It is noticeable that for the short and long range interactions, the Bessel kernel scales as  and

and  , respectively, in agreement with an apparent 2D-3D gravity that we discuss next. Finally, we highlight that the point-wise symmetry of our Bessel kernel, enabled by the root mean square scale height definition (Eq. (9)), eliminates the need for correction terms arising from radial self-accelerations (Baruteau 2008).

, respectively, in agreement with an apparent 2D-3D gravity that we discuss next. Finally, we highlight that the point-wise symmetry of our Bessel kernel, enabled by the root mean square scale height definition (Eq. (9)), eliminates the need for correction terms arising from radial self-accelerations (Baruteau 2008).

3.2 The gravitational character of our formalism

It is worth mentioning a property that we find quite intriguing: while the long-range interaction of our kernel mirrors that of a gravitational force in a 3D space, at short range, it exhibits characteristics akin to a purely 2D nature since the force scales as ∝ 1/s (see the introduction). This feature is particularly important for the short-range interaction of SG within the context of PPDs – and it insightfully highlights the inherent discrepancies of the Plummer potential paradigm.

On the one hand, as the SL approaches the disc scale height, ε ∼ Hg, it causes a significant underestimation of the short-range effects of SG, potentially hindering the formation of gravitationally bound objects. However, on the other hand, if the SL vanishes, it is implied that the scaling of the 2D force is 1/s2, which in turn results in a substantial overestimation of SG. Specifically, in the context of GI, we anticipate that the use of a vanishing SL could result in an overestimation of the formation of bound objects. This may offer a new perspective on the results reported by Vorobyov & Elbakyan (2018), among others. The realism of GI simulations employing a finite yet small SL, in works like Paardekooper et al. (2011) and Takahashi et al. (2016), appears more challenging to predict. While the overestimation of SG in the range dg ∈ [0.2, 3] might suggest an amplification of GI, the suppression of SG at small scales could indicate the inability of fragments to further contract gravitationally, thereby promoting their destruction upon encounters with spirals. A more in-depth numerical investigation is required to evaluate the consequences of employing different gravity prescriptions. This will be the focus of our upcoming paper.

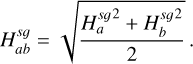

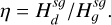

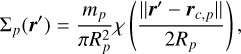

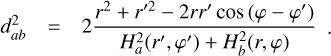

3.3 Gas and dust kernel comparison

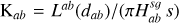

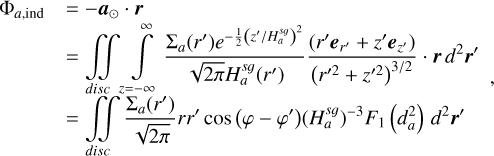

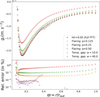

An important feature of our analysis lies in the fact that our kernel does not apply solely to gas discs but it can also account for an embedded dust fluid. Such a situation results in four different contributions to the SG forces: one is attributed to the gas disc, another to the dust layer and two to the mutual interaction between the gas and dust discs. Even if the crosswise contributions are not commutative, the above four contributions only necessitate the evaluation of three kernels: Kgg, Kdd and Kgd=Kdg. As a consequence, we aim to compare how the kernels involving dust, Kdd and Kdg, compare to the kernel of a disc uniquely made of gas for different dust-to-gas scale heights ratios:

(10)

In the top panel of Fig. 2, we depict the dust-to-dust kernel, while in the bottom panel we study the dust-to-gas kernel, which accounts for the crossed contribution. Both quantities were normalised with respect to the gas-gas kernel, Kgg. Motivated by highly settled discs (Villenave et al. 2020, 2022) and also by younger systems with limited sedimentation (Lin et al. 2023), we constrained our investigation to 0.01 ≤ η ≤ 1. As expected, for both cases we observe that the kernel matches the one of a system only made of gas at long distances. Indeed, at long separations a force SG kernel does not depend on the value of the scale height, a feature that also applies within the SL prescription – see Fig. 13 of Müller et al. (2012). Most interestingly, we notice that at short distances, dg ≲ η, the dust-dust kernel is proportional to 1/η. For instance for η=0.01, this suggests that there is an enhancement of dust SG by a factor of 100. Acknowledging that we expect column density dust-to-gas ratios of Z=Σd/Σg=0.01, this suggests that the SG acceleration due to dust is comparable, if not higher, than the one of gas in the limit of short distances. On numerical grounds, this should be however taken with a grain of salt since currently there are little chances that such distances can be resolved by global simulations, except maybe when using adaptive mesh refinement techniques or in the context of shearing box simulations. Regarding the normalised gas-dust kernel, we observe that, at short distances, it rises very quickly (with respect to decreasing η) towards a limiting value of

(10)

In the top panel of Fig. 2, we depict the dust-to-dust kernel, while in the bottom panel we study the dust-to-gas kernel, which accounts for the crossed contribution. Both quantities were normalised with respect to the gas-gas kernel, Kgg. Motivated by highly settled discs (Villenave et al. 2020, 2022) and also by younger systems with limited sedimentation (Lin et al. 2023), we constrained our investigation to 0.01 ≤ η ≤ 1. As expected, for both cases we observe that the kernel matches the one of a system only made of gas at long distances. Indeed, at long separations a force SG kernel does not depend on the value of the scale height, a feature that also applies within the SL prescription – see Fig. 13 of Müller et al. (2012). Most interestingly, we notice that at short distances, dg ≲ η, the dust-dust kernel is proportional to 1/η. For instance for η=0.01, this suggests that there is an enhancement of dust SG by a factor of 100. Acknowledging that we expect column density dust-to-gas ratios of Z=Σd/Σg=0.01, this suggests that the SG acceleration due to dust is comparable, if not higher, than the one of gas in the limit of short distances. On numerical grounds, this should be however taken with a grain of salt since currently there are little chances that such distances can be resolved by global simulations, except maybe when using adaptive mesh refinement techniques or in the context of shearing box simulations. Regarding the normalised gas-dust kernel, we observe that, at short distances, it rises very quickly (with respect to decreasing η) towards a limiting value of  . Surprisingly, this means that the kernel tends towards the planet-disc kernel (see Eq. (20) of Müller et al. 2012), a feature already pointed out by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023). We provide a physical explanation of this result in Sect. 4, below.

. Surprisingly, this means that the kernel tends towards the planet-disc kernel (see Eq. (20) of Müller et al. 2012), a feature already pointed out by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023). We provide a physical explanation of this result in Sect. 4, below.

3.4 Gravitational runaway

In the following, we explore the ability of the Bessel kernel to potentially lead to a runaway process. Let us consider a disc only made of gas where a perturbation caused a local and infinitesimal mass increase over an infinitesimal distance. First, we focus on a massive disc (Qg ≲ 1), where the local mass increase will, in turn, decrease the local Toomre’s parameter. But in the specific case of massive discs the kernel at the singularity3 is  . Subsequently, the local SG is amplified, which feeds into the mechanism, resulting in a possible runaway process. Now, consider the same scenario for a light disc, where the Toomre’s parameter is large. In such a case, the kernel at the singularity is independent of the density perturbation:

. Subsequently, the local SG is amplified, which feeds into the mechanism, resulting in a possible runaway process. Now, consider the same scenario for a light disc, where the Toomre’s parameter is large. In such a case, the kernel at the singularity is independent of the density perturbation:  . Thus, this time, any local increase in density leaves the kernel unaffected, which does not amplify the mechanism and possibly shuts it down. We believe that such a runaway process, which mimics a potential collapse in the vertical direction (through the reduction of the vertical scale height), is uniquely captured by our prescription.

. Thus, this time, any local increase in density leaves the kernel unaffected, which does not amplify the mechanism and possibly shuts it down. We believe that such a runaway process, which mimics a potential collapse in the vertical direction (through the reduction of the vertical scale height), is uniquely captured by our prescription.

We found that out of all prescriptions presented in Sect. 3.1, only ours permits one to maintain a gravitational collapse at infinitesimal distances. Indeed, for Müller et al. (2012) kernel, the rationale of the above paragraph would never lead to a runaway process at infinitely small scales since this kernel vanishes at the singularity, preventing any amplification of gravity caused by the kernel. A runaway is only possible if the length of the perturbation is of the order ∼ Hg for the Müller et al. (2012) kernel but this time the runaway is solely driven by the overdensity term present in the total force calculation (Σg term in Eq. (6)). Similarly, for the SVSL formalism proposed by Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023), even if the kernel does not vanish at the singularity, the runaway would be driven by the overdensity since the kernel is insensitive to the local Toomre’s parameter increase. All the aspects raised above will be addressed in more detail in the accompanying paper. In the following section, we propose to validate our kernel against analytical and numerical tests.

|

Fig. 2 Normalised kernels associated with dust with respect to distance for different dust-to-gas scale heights, η. The dust-dust, Kdd, and dust-gas, Kdg, kernels are insensitive to η at large distances, an aspect also in agreement with the SL prescription (see Fig. 13 of Müller et al. 2012). The dust-dust kernel scales with 1/η at short range, which suggests that the SG acceleration due to dust can be comparable of the one of gas even for Z=Σd/Σg=0.01. At short distances, the normalised dust-gas kernel converges quickly towards |

4 Analytical and numerical validation

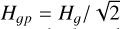

We found it puzzling that the mathematical expression of the Bessel kernel (Eq. (8)) is very similar to the kernel of a planet-disc interaction (Müller et al. 2012, Eq. (20)) by a scaling factor of  in the normalised distance. Convinced that this similarity is not coincidental, we proceed to demonstrate it within our formalism. To elaborate, let us consider a disc made of two fluids: one gas component and a second ‘fluid’ component that we consider as a planet. From a purely gravitational perspective, a planet is nothing more than a fluid with a Dirac distribution in all space directions. Accordingly, the fluid planet is a point and its density in the 2D plane can be expressed as:

in the normalised distance. Convinced that this similarity is not coincidental, we proceed to demonstrate it within our formalism. To elaborate, let us consider a disc made of two fluids: one gas component and a second ‘fluid’ component that we consider as a planet. From a purely gravitational perspective, a planet is nothing more than a fluid with a Dirac distribution in all space directions. Accordingly, the fluid planet is a point and its density in the 2D plane can be expressed as:

(11)

where χ is the rectangular function, Rp and rc, p are the radius and location of the planet, respectively. As the planet’s radius is significantly smaller than all other distances in the problem, the rectangular function could be naturally approximated by a Dirac distribution. Furthermore, the planet inherently possess a zero vertical extension, which leads to the next rms scale height for the system {gas disc + planet}:

(11)

where χ is the rectangular function, Rp and rc, p are the radius and location of the planet, respectively. As the planet’s radius is significantly smaller than all other distances in the problem, the rectangular function could be naturally approximated by a Dirac distribution. Furthermore, the planet inherently possess a zero vertical extension, which leads to the next rms scale height for the system {gas disc + planet}:  4 (see Eq. (9)). With all these observations, we can calculate the gravitational force density of the planet acting on the gas disc:

4 (see Eq. (9)). With all these observations, we can calculate the gravitational force density of the planet acting on the gas disc:

![$ \begin{align*} \boldsymbol{f}_{2 D}^{p \rightarrow g} & =-\Sigma_{g} \iint_{d i s c} \Sigma_{p} K_{g p} \boldsymbol{e}_{s} d^{2} \boldsymbol{r}^{\prime} \\ & =-\Sigma_{g} \frac{m_{p}}{s} \sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}} \frac{1}{H_{g}} c^{2} \exp \left(c^{2}\right)\left[K_{1}\left(c^{2}\right)-K_{0}\left(c^{2}\right)\right] \boldsymbol{e}_{c, p} \end{align*} $](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq31.png) (12)

where

(12)

where  and ec, p=(r−rc, p) /|r−rc, p| is the unit vector oriented from the planet to the fluid element located at r. The above expression is exactly the force density of a planet acting on the gas disc (Müller et al. 2012, Eq. (25)), which validates the consistency of our approach. In other words, the planet-disc interaction kernel is nothing more than a special case of the Bessel prescription emphasised in this article. This observation, which began as a curiosity, constitutes our first analytical test.

and ec, p=(r−rc, p) /|r−rc, p| is the unit vector oriented from the planet to the fluid element located at r. The above expression is exactly the force density of a planet acting on the gas disc (Müller et al. 2012, Eq. (25)), which validates the consistency of our approach. In other words, the planet-disc interaction kernel is nothing more than a special case of the Bessel prescription emphasised in this article. This observation, which began as a curiosity, constitutes our first analytical test.

Another basic analytical test for assessing the correctness of our approach lies in the retrieve of the potentials associated with razor-thin discs, i.e. when the scale height of the disc tends to zero,  . This is achieved simply by using the well-known result

. This is achieved simply by using the well-known result

(13)

which, when used in Eq. (7), permits one to get the force kernel of a razor-thin disc:

(13)

which, when used in Eq. (7), permits one to get the force kernel of a razor-thin disc:

(14)

Such a limit naturally applies to the kernel under its closed form (Eq. (8)) by the use of the dominated convergence theorem, which permits one to commute the vertical integrals and the limits. This second simple analytical validation test shows that we expect to recover analytical and numerical results that apply to flat discs. Consequently, in order to benchmark our Kernel and check our numerical implementation, we decided to compare in the next sections the SG forces provided by our prescription against exact derivations for specific matter distributions and/or 3D numerical tests. We primarily focus in the next sections on the accuracy of our spectral solver and the comparison between 3D simulations and different 2D gravity prescriptions, leaving for a future article the benchmark of the multi-fluid treatment. We start by presenting our numerical set-up and codes.

(14)

Such a limit naturally applies to the kernel under its closed form (Eq. (8)) by the use of the dominated convergence theorem, which permits one to commute the vertical integrals and the limits. This second simple analytical validation test shows that we expect to recover analytical and numerical results that apply to flat discs. Consequently, in order to benchmark our Kernel and check our numerical implementation, we decided to compare in the next sections the SG forces provided by our prescription against exact derivations for specific matter distributions and/or 3D numerical tests. We primarily focus in the next sections on the accuracy of our spectral solver and the comparison between 3D simulations and different 2D gravity prescriptions, leaving for a future article the benchmark of the multi-fluid treatment. We start by presenting our numerical set-up and codes.

4.1 Numerical method and codes

The tests of this section were performed employing both the FargoCPT (Rometsch et al. 2024) and Nirvana-III (Ziegler 2004, 2016) codes. FargoCPT is a 2D finite difference code with a staggered mesh, employing an advection scheme akin to finite volume methods. It solves the hydrodynamics equations using operator splitting and a second-order upwind scheme. FargoCPT and its variants, such as FARGOCA (Lega et al. 2014), FARGOADSG (Baruteau & Masset 2008), and FARGO3D (Benítez-Llambay & Masset 2016), are built upon the Fargo code presented in (Masset 2000). It is formally accurate up to second-order in space and first-order in time and relies on artificial viscosity for shock smoothing (Rometsch et al. 2024). In this code the Bessel kernel was computed by means of full FFT methods, which requires one to satisfy H/r= const. (See Sect. 5.2). Thus, we used a logarithmic grid in the radial direction and a linear grid in the azimuthal direction. We also made use of zero-padding for density in order to guarantee artificial periodicity in the radial direction.

The Bessel kernel was also implemented in the updated version of the Nirvana-iii code, as presented in Gressel et al. (2020). Unlike our implementation in FargoCPT, this time we used a semi-spectral method, which removes the constraint on linear scale heights, allowing for linear radial grids and greater generality (See Sect. 5.2). Finally, in Sect. 4.4, we also employed Nirvana-iii to perform 3D simulations, enabling a comparison between the outcomes of 2D and 3D simulations. In particular, Nirvana-III features a new approach (Gressel & Ziegler 2024) based on James’ method for the computation of the gravitational potential at the poloidal domain boundaries (see James 1977; Moon et al. 2019). We start by showing that the Bessel prescription permits the retrieval of the radial accelerations of flat power law discs.

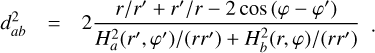

4.2 Power law discs

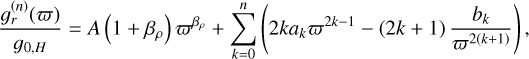

One of the very few exact analytical solutions of the gravitational potential in flat discs concerns axisymmetric, finite-size, and power law density discs (Huré & Hersant 2007; Huré et al. 2008; Baruteau 2008). For such a disc, the authors decomposed the exact potential in terms of series, which permits an evaluation of the SG radial component5:

(15)

where ϖ=r/rout, βρ is the surface density power index and g0, H=−2π G Σ(rout). The constant A and the sequence coefficients can be found in the original papers. Naturally, the above series converges asymptotically to the exact gravitational force. In their study, the authors considered an infinitely thin disc and evaluated the potential in the equatorial plane. Conversely, our results are applicable to a Gaussian vertical profile but they can be safely compared to theirs in the limit of the razor-thin disc approximation, i.e. small aspect ratios:

(15)

where ϖ=r/rout, βρ is the surface density power index and g0, H=−2π G Σ(rout). The constant A and the sequence coefficients can be found in the original papers. Naturally, the above series converges asymptotically to the exact gravitational force. In their study, the authors considered an infinitely thin disc and evaluated the potential in the equatorial plane. Conversely, our results are applicable to a Gaussian vertical profile but they can be safely compared to theirs in the limit of the razor-thin disc approximation, i.e. small aspect ratios:  .

.

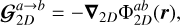

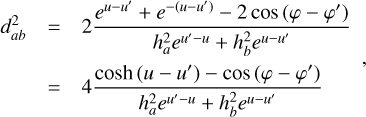

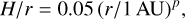

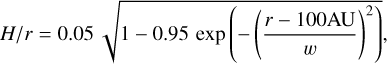

In Fig. 3, we depicted the force derived from Huré et al. (2008) potential (solid blue line) for n=100 and compared it with the force provided by our Bessel kernel for the power law index βρ=−1.5 and decreasing aspect ratios. Our numerical set-up is

![$\left\{\begin{array}{ll}\Sigma_{0}(r) & =20000(r / 1 \mathrm{AU})^{\beta_{\rho}} \mathrm{g} \mathrm{cm}^{-2} \\ H / r^{q} & =[0.1,0.01,0.001] \\ \left(r_{\text {in }}, r_{\text {out }}\right) & =(20,250) \mathrm{AU} \\ \left(N_{r}, N_{\varphi}\right) & =(1200,2800)\end{array}\right.,$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq38.png) (16)

where Nr and Nϕ are the number of cells in the radial and azimuthal direction, respectively. Using FFT in the radial direction with FargoCPT required setting q=1, while for Nirvana-iii, which offers more flexibility, we used q=0. We chose these two distinct values of q to illustrate that our framework accommodates to any disc flaring. For FargoCPT simulations, the relative error decreases with a decreasing disc aspect ratio, aligning with our Bessel kernel’s ability to achieve the flat disc limit. For smaller aspect ratios, the accuracy is limited to approximately ∼ 10−3 and ∼ 10−4 for FargoCPT. The same trend is observed with Nirvana-iii, but the relative error reaches 10−4 more rapidly as the aspect ratio decreases. Notably, when H=0.1, the error is around 10−3, two orders of magnitude smaller than the equivalent H/r=0.1 set-up. This indicates that the common assumption of H/r= const. in thin disc simulations may introduce significant errors. We highlight that the exact radial SG force cancels at ϖ ≃ 0.07, which leads to a statistical bias in the relative error in this region. Finally, we checked that the accuracy trend with respect to the disc aspect ratio remains consistent for other power law indices ranging from [−3, 3], validating our first test.

(16)

where Nr and Nϕ are the number of cells in the radial and azimuthal direction, respectively. Using FFT in the radial direction with FargoCPT required setting q=1, while for Nirvana-iii, which offers more flexibility, we used q=0. We chose these two distinct values of q to illustrate that our framework accommodates to any disc flaring. For FargoCPT simulations, the relative error decreases with a decreasing disc aspect ratio, aligning with our Bessel kernel’s ability to achieve the flat disc limit. For smaller aspect ratios, the accuracy is limited to approximately ∼ 10−3 and ∼ 10−4 for FargoCPT. The same trend is observed with Nirvana-iii, but the relative error reaches 10−4 more rapidly as the aspect ratio decreases. Notably, when H=0.1, the error is around 10−3, two orders of magnitude smaller than the equivalent H/r=0.1 set-up. This indicates that the common assumption of H/r= const. in thin disc simulations may introduce significant errors. We highlight that the exact radial SG force cancels at ϖ ≃ 0.07, which leads to a statistical bias in the relative error in this region. Finally, we checked that the accuracy trend with respect to the disc aspect ratio remains consistent for other power law indices ranging from [−3, 3], validating our first test.

|

Fig. 3 Radial SG force of the power law disc for different scale heights. The accuracy of our kernel increases with decreasing aspect ratios. Note that for ϖ ≃ 0.07 the relative error is beyond unity, which is a bias in the statistical measure due to a vanishing radial acceleration. We recall that in FargoCPT and Nirvana-iii we used a logarithmic and uniform radial grid, respectively. |

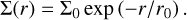

4.3 The exponential disc

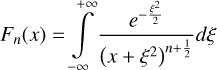

Another analytical result that is useful for comparison with our Bessel kernel relates to exponential discs:

(17)

Indeed, the gravitational potential associated with these discs in the equatorial plane is known (Freeman 1970; Binney & Tremaine 2008, Sect. 2.6), which permits one to exactly derive the radial acceleration due to the disc’s own gravity:

(17)

Indeed, the gravitational potential associated with these discs in the equatorial plane is known (Freeman 1970; Binney & Tremaine 2008, Sect. 2.6), which permits one to exactly derive the radial acceleration due to the disc’s own gravity:

![$g_{r}(r)=-g_{0, F} y\left[I_{0}(y) K_{0}(y)-I_{1}(y) K_{1}(y)\right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq40.png) (18)

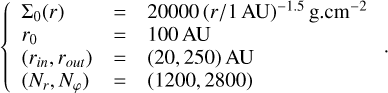

where y=r /(2 r0) and g0, F=2 π G Σ0. The notations Iα and Kα refer to modified Bessel functions (of order α) of the first and second kind, respectively. Once again, our goal here is to compare the exact acceleration of the exponential discs (Eq. (18)) with the acceleration obtained numerically by the use of the Bessel prescription in the limit of small disc aspect ratios. For the numerical side, our set-up is

(18)

where y=r /(2 r0) and g0, F=2 π G Σ0. The notations Iα and Kα refer to modified Bessel functions (of order α) of the first and second kind, respectively. Once again, our goal here is to compare the exact acceleration of the exponential discs (Eq. (18)) with the acceleration obtained numerically by the use of the Bessel prescription in the limit of small disc aspect ratios. For the numerical side, our set-up is

![$\left\{\begin{array}{ll}\Sigma_{0}(r) & =200 \mathrm{~g} \mathrm{~cm}^{-2} \\ H / r^{q} & =[0.1,0.01,0.001] \\ r_{0} & =250 \mathrm{AU} \\ \left(r_{\text {in }}, r_{\text {out }}\right) & =(0.01,2500) \mathrm{AU} \\ \left(N_{r}, N_{\varphi}\right) & =(1200,2800)\end{array}\right..$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq41.png) (19)

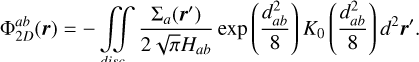

We maintained the same set-up as in the previous section, with q=1 for FargoCPT and q=0 for Nirvana-iii. The results of this comparison are depicted in Fig. 4. The conclusions are similar to the ones drawn for the power law disc (see Sect. 4.2), with the difference that this time the radial SG force vanishes at y=0. The only difference is that FargoCPT more closely approximates the analytical solution than Nirvana-III for H/rq=0.001. This is because FargoCPT's logarithmic grid better resolves the inner disc, where most of the mass lies.

(19)

We maintained the same set-up as in the previous section, with q=1 for FargoCPT and q=0 for Nirvana-iii. The results of this comparison are depicted in Fig. 4. The conclusions are similar to the ones drawn for the power law disc (see Sect. 4.2), with the difference that this time the radial SG force vanishes at y=0. The only difference is that FargoCPT more closely approximates the analytical solution than Nirvana-III for H/rq=0.001. This is because FargoCPT's logarithmic grid better resolves the inner disc, where most of the mass lies.

|

Fig. 4 Radial SG force of the exponential disc for different scale heights. The accuracy of our kernel increases with decreasing aspect ratios and piles up at ∼ 10−4. Note that for y=0 the relative error is beyond unity, which is a bias in the statistical measure due to a vanishing radial acceleration. |

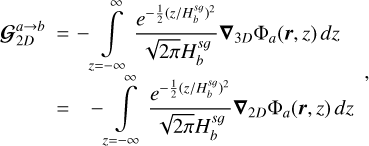

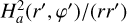

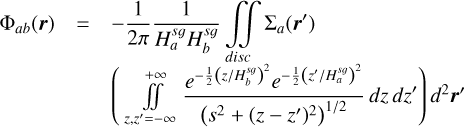

4.4 Gaussian discs test

To assess the accuracy of 2D SG prescriptions, it is common to resort to the Gaussian spheres test (Chan et al. 2006; Li et al. 2009). This test involves averaging vertically the 3D gravitational field associated with 3D Gaussian spheres positioned at different locations and comparing it with the results obtained using a 2D kernel. A benefit of this benchmark is its capability to assess the azimuthal component of the gravitational force. Given the analytical challenges in vertically averaging the SG force of a Gaussian sphere, we chose to conduct this test solely through numerical methods, as is explained in the following paragraphs.

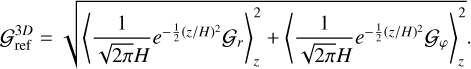

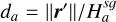

Our test entails computing the 3D gravitational field of Gaussian discs in z= const. planes and serving as perturbation to a background Gaussian vertically stratified density. The resulting 3D gravitational field is then vertically integrated and used for computing the reference field amplitude in the equatorial plane:

(20)

We highlight that

(20)

We highlight that  denotes the 3D gravitational field obtained with Nirvana-iii, followed by vertical integration denoted by 〈…〉z, with the appropriate factors accounted for. This reference field is then compared with the results of the 2D SG prescriptions,

denotes the 3D gravitational field obtained with Nirvana-iii, followed by vertical integration denoted by 〈…〉z, with the appropriate factors accounted for. This reference field is then compared with the results of the 2D SG prescriptions,

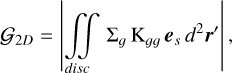

(21)

specifically the Bessel kernel, on the one hand, and a Plummer potential with two different SL values, ε/H=[0, 1.2], respectively, on the other hand. While 𝒢2D is not strictly the absolute value of a 2D gravitational field, as it is not derived from a potential (as detailed in Sect. 5.5), it remains the quantity that can be faithfully compared with its 3D counterpart,

(21)

specifically the Bessel kernel, on the one hand, and a Plummer potential with two different SL values, ε/H=[0, 1.2], respectively, on the other hand. While 𝒢2D is not strictly the absolute value of a 2D gravitational field, as it is not derived from a potential (as detailed in Sect. 5.5), it remains the quantity that can be faithfully compared with its 3D counterpart,  . To assess the potential limitations of each prescription based on the disc vertical extent, we conducted this test for three different scale heights: H = [0.01, 0.1, 0.4].

. To assess the potential limitations of each prescription based on the disc vertical extent, we conducted this test for three different scale heights: H = [0.01, 0.1, 0.4].

For this test, the density consists of a constant background distribution,

![$ \left\{\begin{array}{ll} \rho_{0}(\boldsymbol{r}, z) & =\frac{\Sigma_{0}}{\sqrt{2 \pi} H} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{z}{H}\right)^{2}\right)\\ \Sigma_{0} & =200 \mathrm{~g} \mathrm{~cm}^{-2} \\ H & =[0.1,0.01] \mathrm{AU} \end{array},\right. $](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq46.png) (22)

with perturbations introduced in the form of the aforementioned Gaussian discs,

(22)

with perturbations introduced in the form of the aforementioned Gaussian discs,

![$\rho(\boldsymbol{r}, z)=\rho_{0}(\boldsymbol{r}, z) \prod_{i=1}^{N=3}\left[1+A_{i} \exp \left(-\frac{1}{2} \frac{\left|\boldsymbol{r}-\boldsymbol{r}_{c, i}\right|^{2}}{R_{i}^{2}}\right)\right].$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq47.png) (23)

The parameters Ai, rc, i, and Ri, which represent the relative amplitude, centre location, and radius of the Gaussian, respectively, are detailed in Table 2. For the evaluation of the 3D gravitational field employing the NIRVANA-iii code, we used a cylindrical grid with next computational domain extents:

(23)

The parameters Ai, rc, i, and Ri, which represent the relative amplitude, centre location, and radius of the Gaussian, respectively, are detailed in Table 2. For the evaluation of the 3D gravitational field employing the NIRVANA-iii code, we used a cylindrical grid with next computational domain extents:

![$\left\{\begin{array}{lll} r & \in & {[2,10] \mathrm{AU}} \\ \varphi & \in & {[0,2 \pi]} \\ z & \in & {[-5 H, 5 H]} \end{array}.\right.$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/02/aa55989-25/aa55989-25-eq48.png) (24)

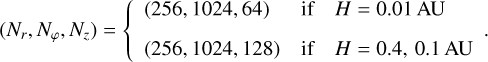

We used two different number of cells for the 3D set-up:

(24)

We used two different number of cells for the 3D set-up:

(25)

This distinct choice permitted us to reduce the anisotropy in our 3D grid, which facilitated the convergence of the multigrid solver. For the 2D simulations counterpart, we kept the radial and azimuth resolution unchanged compared to the 3D set-up.

(25)

This distinct choice permitted us to reduce the anisotropy in our 3D grid, which facilitated the convergence of the multigrid solver. For the 2D simulations counterpart, we kept the radial and azimuth resolution unchanged compared to the 3D set-up.

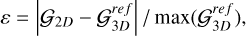

In Fig. 5 we depicted the relative difference between the reference simulation and it is 2D analogues for different SG prescriptions,

(26)

associated with the above set-up and for H=0.4. The amplitude of the 2D gravitational field, computed using the semi-spectral method implemented in Nirvana-iii, is depicted by 𝒢2D. The choice of the above error stems from the fact that the gravitational field amplitude approaches 0 in two regions, which makes the standard relative norm diverge, which bias the interpretation. We quantified the deviation by presenting the following L∞ norm:

(26)

associated with the above set-up and for H=0.4. The amplitude of the 2D gravitational field, computed using the semi-spectral method implemented in Nirvana-iii, is depicted by 𝒢2D. The choice of the above error stems from the fact that the gravitational field amplitude approaches 0 in two regions, which makes the standard relative norm diverge, which bias the interpretation. We quantified the deviation by presenting the following L∞ norm:

(27)

The above L∞ norm is presented in Table 3 for various 2D SG prescriptions. Our findings indicate that for the three different scale heights, the error associated with the Bessel kernel remains within a few percent. Although the maximum error is found near the Gaussian discs positions, it is not centred on them. These minimal deviations, even for high scale heights such as H=0.4, are due to our method’s versatility, which is not limited to razor-thin discs but is applicable to any geometrical aspect ratio. Conversely, the error associated with the Plummer potential varies with the disc scale height and decreases as the scale height diminishes. Specifically, for ε/H=1.2 and H=0.4, the maximum error reaches 28% and is located in the disc of the smallest radius. Indeed, this prescription fails to resolve gravitationally bumps with dimensions smaller than the SL. Notably, this set-up generally underestimates SG. On the other hand, for ε/H=0 and H=0.4, the maximum error reaches 129%. In this case the highest errors are located in the regions of highest density, and this prescription generally overestimates SG. When the scale height decreases to H=0.01, all three prescriptions yield similar results, with an overall maximum error of just a few percent.

(27)

The above L∞ norm is presented in Table 3 for various 2D SG prescriptions. Our findings indicate that for the three different scale heights, the error associated with the Bessel kernel remains within a few percent. Although the maximum error is found near the Gaussian discs positions, it is not centred on them. These minimal deviations, even for high scale heights such as H=0.4, are due to our method’s versatility, which is not limited to razor-thin discs but is applicable to any geometrical aspect ratio. Conversely, the error associated with the Plummer potential varies with the disc scale height and decreases as the scale height diminishes. Specifically, for ε/H=1.2 and H=0.4, the maximum error reaches 28% and is located in the disc of the smallest radius. Indeed, this prescription fails to resolve gravitationally bumps with dimensions smaller than the SL. Notably, this set-up generally underestimates SG. On the other hand, for ε/H=0 and H=0.4, the maximum error reaches 129%. In this case the highest errors are located in the regions of highest density, and this prescription generally overestimates SG. When the scale height decreases to H=0.01, all three prescriptions yield similar results, with an overall maximum error of just a few percent.

With this test, we have demonstrated that the Plummer potential prescription fails to provide an accurate estimation of SG in regions of high density, where SG is overestimated for ε/H=0, and in regions smaller than the scale height for ε/H=1.2, where SG is underestimated. Conversely, the Bessel prescription consistently delivers accurate results across the entire range of scale heights.

Parameters of the Gaussian cylinder test.

5 Discussion

In this section, we explore the potential consequences of our approach for tackling GI, as well as the numerical methods of estimating SG, and we consider alternative methods that offer greater generality. Then, we identify the limitations of our approach and present solutions for scenarios where we deviate from the initial assumptions. Finally, we delve into a detailed discussion on the Poisson’s equation for 2D systems and its implicit implications for 3D systems. In this context, we propose an effective 2D gravitational potential consistent with our formalism.

5.1 Consequences for planet formation

Our detailed study of the Bessel kernel, along with the tests conducted in Sects. 3–4, has revealed and quantified that the Plummer potential can both under- and overestimate the importance of SG. These findings could have profound implications for planet formation theories, particularly the GI, as most simulations characterising it have been conducted using a thin disc approximation. This approach typically employs a SL prescription for the gravitational potential or involves solving a 2D Poisson equation. We take this opportunity to clarify that solving a 2D Poisson equation, as is often done in the flat disc limit, is equivalent to using a Plummer potential with ε/H=0, as is explained in Sect. 5.5.

On the one hand, we affirm that a finite SL suppresses the Newtonian character of gravity, potentially quenching gravitational collapse or enhancing clump disruption during spiral encounters (Young & Clarke 2015). On the other hand, we also affirm that a vanishing SL artificially amplifies gravity. In this context, we recall that an ongoing issue is the convergence problem, which stems from the lack of consensus about the threshold cooling parameter that separates the regime of gravito-turbulence from fragmentation in 2D simulations (Young & Clarke 2015; Kratter & Lodato 2016). The issue first emerged in 3D SPH simulations of gravito-turbulence (Meru & Bate 2011), where resolution-dependent artificial viscosity likely played a significant role (Lodato & Clarke 2011). In 2D grid-based simulations, some aspects of the problem were later attributed to inner edge effects (Paardekooper et al. 2011), though the issue remains only partially addressed in these set-ups. Consistent with these earlier findings, Paardekooper (2012) demonstrated that fragmentation is a stochastic process, allowing discs to fragment at broad beta-cooling ranges and blurring the boundary between gravito-turbulence and fragmentation regimes. Given that these simulations were conducted thanks to 2D shearing box simulations with a similar framework where SL equals zero, we think that our Bessel formulation would be key to addressing the convergence problem. More specifically it will likely narrow and better constrain the beta cooling parameter range where stochastic fragmentation occurs.

L∞ deviations used in the Gaussian disc test.

|

Fig. 5 Relative difference between the 2D SG prescriptions and the reference gravitational field (see Eq. (26)) for H = 0.4 AU. From left to right: (left panel) the sharp potential with ε/H = 0, (middle panel) the variable Bessel kernel, and (right panel) the soft potential with ε/H=1.2. The colours of the contour levels at 10−5, 10−3, 0.1, 0.5 are indicated in the colour bar. Softening prescriptions exhibit errors exceeding tens of percent at disc positions, whereas the Bessel prescription maintain errors below 3%. |

5.2 Numerical assessment with FFT methods

The calculation of SG using the Bessel kernel remains compatible with FFT techniques. This compatibility arises from expressing the radial and azimuthal components of the SG force as convolution products (Baruteau & Masset 2008; Rendon Restrepo & Barge 2023). The explicit forms of the kernel components, ready for use in convolution operations, are provided in Appendix C. The main advantage of this method lies in the acceleration of the calculation since it requires Nr Nϕ log (Nr Nϕ) operations, in contrast with direct summation that requires (Nr Nϕ)2 operations. This gain in performance requires one nonetheless to obey some constraints. First, in order to enable a description in the form of a convolution product, it is necessary that the radial grid is logarithmic. This requires that the disc aspect ratio of the self-gravitating disc,  , remains constant in the whole numerical domain (see Appendix D for a discussion when deviating from this condition). Following the procedure of Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023, Sect. 4.2), we found that this indirectly implies that the bi-fluid Toomre’s parameter, Qbi-fluid, and the standard disc scale height, Ha/r, should remain constant throughout the entire numerical domain – and also in time. This stringent requirement precludes the use of FFT methods in realistic set-ups. Consequently, if FFT methods are necessary, the simplest approach is to use the thermal scale height without the SG correction: Hsg ≃ H. Second, the use of Fourier transforms demands periodicity in all directions, which requires one to double the radial domain with a zero-padding in order to perform an aperiodic convolution (Hockney & Eastwood 2021). This operation does not affect the computational endeavour since the Hermitian property of Fourier transforms halves the total number of transforms and, as a consequence, compensates the doubling of the domain. Finally, this zero-padding does not affect the SG computation as checked in Sect. 4.

, remains constant in the whole numerical domain (see Appendix D for a discussion when deviating from this condition). Following the procedure of Rendon Restrepo & Barge (2023, Sect. 4.2), we found that this indirectly implies that the bi-fluid Toomre’s parameter, Qbi-fluid, and the standard disc scale height, Ha/r, should remain constant throughout the entire numerical domain – and also in time. This stringent requirement precludes the use of FFT methods in realistic set-ups. Consequently, if FFT methods are necessary, the simplest approach is to use the thermal scale height without the SG correction: Hsg ≃ H. Second, the use of Fourier transforms demands periodicity in all directions, which requires one to double the radial domain with a zero-padding in order to perform an aperiodic convolution (Hockney & Eastwood 2021). This operation does not affect the computational endeavour since the Hermitian property of Fourier transforms halves the total number of transforms and, as a consequence, compensates the doubling of the domain. Finally, this zero-padding does not affect the SG computation as checked in Sect. 4.

Computing the Bessel kernel requires one to use special functions, which is computationally expensive. In FargoCPT, the Bessel kernel calculation is roughly 20 times slower than the original kernel calculation. If the Bessel kernel is recomputed at every iteration, this increases the cost of SG from around 40% to around 130% of the transport step cost, or from 21% to 45% of the total computational costs when using a locally isothermal equation of state. For the latter, however, the SG kernel can be precomputed for the whole simulation because it does not change with time. Then, there is no difference in computational cost after the initialisation. In case of a non-isothermal equation of state, the kernel can be recomputed only every so often to save computational costs. This can be justified by the fact that the scale height of the disc only changes slowly, at least when the cooling timescale is short compared to the dynamical timescale. For a more realistic stratification in presence of SG, there is however also a physical issue. In this case, the aspectratio of the disc is no longer constant and the method is formally no longer applicable and only yields an approximation to the SG accelerations.

In general, we expect the disc flaring to not be constant, which renders the application of our method with FFT impractical. For instance, the  = const. constraint (necessary for full spectral methods) becomes prohibitive when investigating massive discs. Indeed this constraint implies that the Toomre’s parameter needs to be constant in the whole domain and frozen in time. Therefore, a potential decrease in the Toomre’s parameter due to a gravitational runaway process will not be captured by these methods. As a consequence, the other computational possibility, which was in fact implemented in Nirvana-iii, consists of resorting to a pseudo-spectral method based on a combination of FFT in the azimuthal direction followed by a direct summation in radial direction, whose complexity is in