| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A364 | |

| Number of page(s) | 16 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557061 | |

| Published online | 20 February 2026 | |

Mysteries of Capotauro: Investigating the puzzling nature of an extreme F356W-dropout

1

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “G. Galilei”, Università di Padova Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3 35122 Padova, Italy

2

INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5 35122 Padova, Italy

3

INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma Via Frascati 33 00078 Monteporzio Catone Roma, Italy

4

NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory 950 N. Cherry Ave. Tucson AZ 85719, USA

5

Department of Astronomy, The University of Texas at Austin Austin TX, USA

6

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Roma Sapienza, Città Universitaria di Roma – Sapienza, Piazzale Aldo Moro 2 00185 Roma, Italy

7

Astrophysics Science Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center 8800 Greenbelt Rd Greenbelt MD 20771, USA

8

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Kansas Lawrence KS 66045, USA

9

Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Louisville Natural Science Building 102 Louisville KY 40292, USA

10

INAF, Istituto di Radioastronomia Via Piero Gobetti 101 40129 Bologna, Italy

11

Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, The Pennsylvania State University University Park PA 16802, USA

12

Institute for Computational and Data Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University University Park PA 16802, USA

13

Institute for Gravitation and the Cosmos, The Pennsylvania State University University Park PA 16802, USA

14

CEA, IRFU, DAp, AIM, Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Cité, Sorbonne Paris Cité, CNRS 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France

15

Space Telescope Science Institute 3700 San Martin Drive Baltimore MD 21218, USA

16

Institute of Physics, Laboratory of Galaxy Evolution, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Observatoire de Sauverny 1290 Versoix, Switzerland

17

SISSA Via Bonomea 265 34136 Trieste, Italy

18

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian 60 Garden St Cambridge MA 02138, USA

19

Black Hole Initiative, Harvard University 20 Garden St Cambridge MA 02138, USA

20

Centro de Astrobiología (CAB), CSIC-INTA Ctra. de Ajalvir km 4 Torrejón de Ardoz E-28850 Madrid, Spain

21

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California 900 University Ave Riverside CA 92521, USA

22

Astronomy Centre, University of Sussex Falmer Brighton BN1 9QH, UK

23

European Space Agency (ESA), European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC) Camino Bajo del Castillo s/n 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada Madrid, Spain

24

Laboratory for Multiwavelength Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, Rochester Institute of Technology 84 Lomb Memorial Drive Rochester NY 14623, USA

25

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University College Station TX 77843-4242, USA

26

George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University College Station TX 77843-4242, USA

27

ESA/AURA Space Telescope Science Institute Baltimore MD, USA

28

University of Louisville, Department of Physics and Astronomy 102 Natural Science Building 40292 KY Louisville, USA

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

1

September

2025

Accepted:

6

December

2025

Context. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has uncovered a diverse population of extreme near-infrared dropouts, including ultra-high-redshift (z > 15) galaxy candidates, dust-obscured galaxies challenging theories of dust production, sources with strong Balmer breaks (possibly compact active galactic nuclei in dense gas-rich environments), and cold, substellar Galactic objects.

Aims. This work presents Capotauro, a F356W-dropout identified in the CEERS survey with a F444W AB magnitude of ∼27.68 and exhibiting a sharp flux drop by > 3 mag between 3.5 and 4.5 μm, being nondetected below 3.5 μm. We investigated its nature and constrained its properties, paving the way for follow-up observations.

Methods. We combined JWST/NIRCam, MIRI, and NIRSpec/MSA data with HST/ACS and WFC3 observations to perform a spectrophotometric analysis of Capotauro using multiple SED-fitting codes. Our setup is tailored to test z ≥ 15 as well as z < 10 dusty, Balmer-break or strong-line emitter galaxy solutions, and the possibility of Capotauro being a Milky Way substellar object.

Results. Among extragalactic options, our analysis favors interpreting the sharp flux drop of Capotauro as a bright (MUV ∼ −21.5) Lyman break at z ∼ 32, consistent with the formation epoch of the first stars and black holes, with only ∼0.5% of the redshift posterior volume lying at z < 25. Lower-redshift solutions struggle to reproduce the extreme break, suggesting that if Capotauro resides at z < 10, it must show a nonstandard combination of high dust attenuation and/or prominent Balmer breaks, making it a peculiar interloper. Finally, our analysis indicates that Capotauro’s properties could be consistent with it being a very cold (i.e., Y2-Y3 type) brown dwarf or a free-floating exoplanet with a record-breaking combination of low temperature and large distance (Teff ≤ 300 K; d ≳ 130 pc, up to ∼2 kpc).

Conclusions. While present observations cannot determine Capotauro’s nature, our analysis points to a remarkably unique object in all plausible scenarios. This makes Capotauro stand out as a compelling target for follow-up observations.

Key words: brown dwarfs / galaxies: evolution / galaxies: formation / galaxies: high-redshift

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST; Gardner et al. 2006, 2023) has greatly enhanced our ability to identify and characterize faint near-infrared (NIR) dropout sources, objects that drop out of detection in the bluest available NIR filters. Due to JWST’s unparalleled sensitivity at wavelengths > 2 μm, NIR dropout selections have become a powerful tool for uncovering new classes of objects that were previously inaccessible. Indeed, JWST NIR dropout searches successfully pushed Lyman-break galaxy confirmations to z ∼ 14 (Carniani et al. 2024; Naidu et al. 2025b), spurring efforts to extend dropout selections into even redder JWST/NIRCam bands in search of ultra-high-redshift (z ≳ 15) candidates (Yan et al. 2023; Austin et al. 2023; Harikane et al. 2023; Donnan et al. 2023; Pérez-González et al. 2023; Kocevski et al. 2025; Pérez-González et al. 2025; Castellano et al. 2025; Gandolfi et al. 2026; Whitler et al. 2025). Although some models, such as FLARES (Lovell et al. 2021; Wilkins et al. 2023), are able to reproduce the observed number densities up to at least z < 13 without enhancements, the observed excess of bright galaxies at z > 9 (e.g., Naidu et al. 2022; Castellano et al. 2022; Sun et al. 2023; Finkelstein et al. 2023, 2024) could still point to processes such as enhanced star formation efficiency, a different initial mass function (IMF), rapid baryon assembly (e.g., weak feedback), bursty and/or stochastic star formation, or low dust attenuation (Dekel et al. 2023; Ferrara et al. 2023; Ciesla et al. 2024; Lapi et al. 2024; Trinca et al. 2024; Yung et al. 2024a; Ferrara et al. 2025; Mauerhofer et al. 2025; Somerville et al. 2025). If such mechanisms are already in place by z ∼ 9 − 10, then the detection of candidates at z ≥ 15 could provide critical insights into the underlying physics responsible for this excess.

However, given the depth of current surveys, the selection of ultra-high-redshift candidates (expected to appear as dropouts at λ ≳ 2 μm in JWST/NIRCam imaging) is complicated by contamination from lower-redshift sources. Via diverse and often astrophysically interesting mechanisms, several classes of foreground objects can produce a sharp decrease in flux at the short-wavelength end of their NIR emission, mimicking a Lyman break and, in general, reproducing the photometric signatures expected for z ≥ 15 objects (e.g., Vulcani et al. 2017; Gandolfi et al. 2026; Castellano et al. 2025).

Among the potential interlopers, sources with substantial dust obscuration can appear as NIR dropouts, despite residing at z ≪ 15. The high-extinction–low-mass (HELM) systems (Bisigello et al. 2023, 2025, 2026) exhibit low stellar masses (⟨log M*/M⊙⟩∼7.3) but extreme dust attenuation (⟨AV⟩∼4.9), which challenges the conventional expectation that dust content scales positively with stellar mass if dust was produced predominantly by evolved stars and supernovae (Scalo & Slavsky 1980). Indeed, the NIR color-magnitude properties of HELM galaxies can overlap with those expected for ultra-high-redshift objects (Gandolfi et al. 2026; Castellano et al. 2025), with the first typically residing at z < 1, with a tail extending up to z ∼ 7 (Bisigello et al. 2026). At the opposite extreme in terms of stellar mass, F200W-dropout searches have also revealed JWST/MIRI-detected red monsters at z ≳ 6, suggesting that massive heavily obscured systems with substantial dust reservoirs were already in place at early cosmic epochs (Rodighiero et al. 2023).

At the same time, ultra-high-redshift object searches may be contaminated by foreground sources with sharp Balmer breaks, originating from mature stellar populations or, perhaps, from even more exotic mechanisms. Indeed, JWST has recently revealed a number of compact objects featuring extremely sharp Balmer breaks (Wang et al. 2024; Kokorev et al. 2024; Matthee et al. 2024; Weibel et al. 2025; de Graaff et al. 2025b; Naidu et al. 2025a; de Graaff et al. 2025a; Taylor et al. 2025; Hviding et al. 2025). With effective radii typically below 100 pc, some of these sources are related to the mysterious little red dots (LRDs), a population of very compact, red objects uncovered by JWST (Barro et al. 2024; Kocevski et al. 2025; Guia et al. 2024; Euclid Collaboration: Bisigello et al. 2026; Kocevski et al. 2025), whose spectral energy distributions (SEDs) are often misfit for ultra-high-z galaxies when dedicated templates are not used to fit their properties (Hviding et al. 2025). Intriguingly, LRDs featuring sharp Balmer breaks display broad H and He emission and feature weak metal lines, a spectrum difficult to reconcile with evolved stellar populations. Instead, these sources could be powered by a central ionizing engine – such as a super-Eddington accreting black hole embedded in hot, dense gas – and could feature a broad-line region resembling a stellar atmosphere (Madau & Haardt 2024; Lambrides et al. 2024; Pacucci & Narayan 2025). Recent literature examples of such candidates include the Cliff at zspec = 3.55 (de Graaff et al. 2025a), MoM-BH*-1 at zspec = 7.76 (Naidu et al. 2025a) and CAPERS-LRD-z9 at zspec = 9.288 (Taylor et al. 2025).

Another well-known class of contaminants in z ≥ 15 galaxy searches are strong line emitters, which are foreground galaxies whose intense nebular emission lines in the NIR can dominate broadband fluxes and mimic the photometric continuum expected from ultra-high-redshift sources. A prominent example is CEERS-93316, which was initially identified as a zphot ∼ 16 candidate based on its JWST/NIRCam photometry (Donnan et al. 2023; Harikane et al. 2023; Pérez-González et al. 2023), but later confirmed via spectroscopic follow-up to lie at zspec ∼ 4.9 (Arrabal Haro et al. 2023).

Finally, cold substellar Milky Way objects such as brown dwarfs (BDs), characterized by sharp atmospheric molecular absorption features (Wilkins et al. 2014; Langeroodi & Hjorth 2023; Holwerda et al. 2024; Hainline et al. 2024; Euclid Collaboration: Weaver et al. 2025; Euclid Collaboration: Žerjal et al. 2026; Euclid Collaboration: Mohandasan et al. 2025; Euclid Collaboration: Dominguez-Tagle et al. 2025; Luhman 2025), can mimic the photometric signatures of extragalactic NIR dropouts such as dusty sources (e.g., Holwerda et al. 2024) and, less prominently, LRDs (with sample contamination of up to 20%; e.g., Pérez-González et al. 2024, although other works find this contamination to be negligible; Hviding et al. 2025; Greene et al. 2025), as well as those expected for ultra-high-redshift galaxies. While Milky Way substellar objects with temperatures of ≳400–500 K exhibit a characteristic drop-off at ∼4 μm, they can typically be distinguished from ultra-high-redshift galaxy candidates due to their residual emission around 1 μm (e.g., Holwerda et al. 2024; Leggett 2024; Tu et al. 2025). However, this identification becomes more challenging for colder substellar objects, where the flux at bluer NIR wavelengths vanishes, leaving behind a sharp break in the SED that can mimic the signature of a ultra-high-redshift source. Searches for BDs were previously limited to the solar neighborhood (i.e., up to ∼20 pc; Chen et al. 2025). However, thanks to its sensitivity in the NIR, JWST has opened a new window for BD searches in the Milky Way’s thick disk and halo (e.g., Nonino et al. 2023; Langeroodi & Hjorth 2023; Burgasser et al. 2024; Hainline et al. 2025; Morrissey et al. 2025).

In summary, the diverse and often astrophysically intriguing nature of all the contaminants discussed above underscores the challenge of reliably distinguishing genuine z ≥ 15 sources from interlopers while relying on photometric data alone in NIR dropout searches. As a result, any robust search for ultra-high-redshift galaxies must carefully account for these interlopers, even when they occupy a narrow region of parameter space.

Here we present a spectrophotometric study of Capotauro1 (RA = 214.887376, Dec = 52.797809), an F356W-dropout found in the Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) survey, originally included in the sample by Gandolfi et al. (2026) (ID U-100588). Capotauro is robustly detected only in the two reddest available JWST/NIRCam bands (F410M, S/N ∼ 4.6 and F444W, S/N ∼ 12.5; see Table A.1), with no detection in any other JWST/NIRCam, MIRI, or HST/ACS or WFC3 band. Capotauro’s photometry is also complemented by a short-exposure ( ∼ 0.8h) JWST/NIRSpec PRISM spectrum. We explore whether this combination of photometry and spectroscopy may be compatible with an ultra-high-redshift galaxy or a lower-redshift object (i.e., an extreme Balmer-break system, a strong-line emitter, a dusty source or a combination of these) or even a Milky Way substellar object. We assess each of these scenarios against the current available dataset, with the aim of providing a baseline characterization to guide future observational follow-ups of Capotauro.

This paper is structured as follows. In Section 2 we describe the available data and the setup exploited for their analysis. In Section 3 we present the results of our analysis and discuss the nature of Capotauro in several different scenarios. In Section 4 we draw our conclusions. In this work we adopt a reference Planck Collaboration VI (2020) cosmology and a Chabrier (2003) IMF; all magnitudes are expressed in the AB system (Oke & Gunn 1983).

2. Data and setup

2.1. Imaging

Our analysis relies on JWST/NIRCam imaging data obtained within the CEERS survey program (ERS Program 1345, P.I. S. Finkelstein; Finkelstein et al. 2025). CEERS covers ∼90 arcmin2 of the Extended Groth Strip (EGS; Davis et al. 2007) field with JWST imaging and spectroscopy through a 77.2 hours Director’s Discretionary Early Release Science Program. CEERS JWST/NIRCam observations are available in bands F115W, F150W, F200W, F277W, F356W, F410M, and F444W. Supplementary coverage in the F090W band is provided by the Cycle 1 GO program 2234 (P.I. E. Bañados). CEERS JWST/NIRCam pointings were previously targeted by HST observations both with the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS; covering F435W, F606W and F814W) and Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3; covering F105W, F125W, F140W and F160W) as part of the Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey (CANDELS; Grogin et al. 2011; Koekemoer et al. 2011). We complement our dataset with v0.2 JWST/MIRI imaging obtained within the Cycle 2 GO 3794 survey MIRI EGS Galaxy and AGN (MEGA; P.I. A. Kirkpatrick; Backhaus et al. 2025, custom reduction obtained via private communication). All available bands and the related depths are reported in Table A.1, while Figure B.1 shows 1.2″ × 1.2″ cutouts of Capotauro in all the bands utilized in this work.

2.2. Photometry

To characterize the properties of Capotauro, we exploited the photometry derived within the public CEERS ASTRODEEP-JWST catalog2 (Merlin et al. 2024) based on CEERS DR 0.5 and 0.6. Such catalog leverages carefully chosen detection parameters designed to maximize the detection of high-redshift faint extended objects, using a stacked F356W+F444W detection image. We also used novel mid-infrared JWST/MIRI photometry from the MEGA survey to extend the wavelength range of our analysis and better constrain the nature of the source.

The photometry for Capotauro is presented in Appendix A, while flux measurements are displayed in the last column of Table A.1. Unfortunately, F105W observations do not cover Capotauro, whereas F435W, F140W and F090W observations are unavailable in the ASTRODEEP-JWST catalog. However, such observations are available in the CEERS UNICORN catalog (Finkelstein et al., in prep.). A crossmatch between ASTRODEEP-JWST and the CEERS UNICORN catalog revealed that Capotauro is also undetected (i.e., S/N ≤ 2) in F435W, F140W and F090W. We verified that the inclusion or exclusion of these upper limits in the SED-fitting procedure does not alter our results whatsoever.

2.3. Spectrum

Capotauro was one of the targets of the Cycle 3 program CANDELS-Area Prism Epoch of Reionization Survey (CAPERS; GO-6368; P.I. M. Dickinson; see, e.g., Donnan et al. 2025; Taylor et al. 2025; Kokorev et al. 2025). The source was observed in a single configuration of the JWST/NIRSpec micro-shutter assembly (MSA) using a standard three-point nodding pattern, repeated twice. A cross-dispersion dither in the observing sequence caused the MSA bar structure to obscure the source in half of the exposures, which were therefore discarded from the data combination, leading to a total exposure of t = 2844.83 s (∼0.8 h).

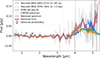

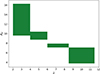

The spectrum is displayed in Figure 1 as a function of observed-frame wavelength, and exhibits a rising continuum redward of ∼4 μm. The emission peak at λ ∼ 4 μm is likely spurious, as it coincides with a region of elevated noise in the RMS map, suggesting it originates from a cluster of noisy pixels rather than genuine line emission. However, we highlight in the top panel of Figure 1 a possible line emission feature at λ ∼ 3.63 μm, which is formally detected at S/N > 5. This tentative line does not correspond to any clear noise cluster in the spectral RMS map, and spans three contiguous pixels in the 1D spectrum, corresponding to 36226 Å, 36334 Å, and 36442 Å respectively, while the tabulated spectral resolution is ∼2.2 px. However, as we visually inspected the three separate, nodded exposures covering Capotauro, we verified that this tentative feature is more prominent in a single exposure in particular, casting doubts on its reliability. We thus decided not to force our SED-fitting setup to reproduce this feature, while opting to keep it as an informative check against our solutions. The potential implication of this line will therefore be discussed in the following sections, but we do not include these considerations in the final assessment of the various options, deferring to future observations the final confirmation (or otherwise) of this feature.

|

Fig. 1. Top panel: Capotauro’s complete JWST and HST photometry in AB magnitudes (left plot), with detections marked as circles and 1σ upper limits as triangles. On the right we report Capotauro’s JWST/NIRCam F356W, F410M, and F444W 1.2″ × 1.2″cutouts (full multi-band single and stacked cutouts are available in Figure B.1). Bottom panel: Capotauro’s 2D JWST/NIRSpec CAPERS spectrum as a function of the observed-frame wavelength. The λ ∼ 3.63 μm potential emission feature is highlighted by a white circle. Below we report the extracted CAPERS spectrum (dark gray line) with 1σ errors (light gray shaded area). The red curve denotes the spectrum rebinned into wavelength bins of width Δλ = 0.1 μm. The surrounding red shaded band illustrates the standard error of the mean in each bin, while the black dashed line marks the zero flux level. The inset displays all the available NIRspec PRISM slits of our CAPERS observations (red for those not containing the source, which were rejected, and green for those containing the source). |

We rebinned Capotauro’s spectrum using a bin size of Δλ = 0.1 μm (the red line in the bottom panel of Figure 1). The red shaded area was computed as the standard error of the mean Δfi in each bin, given by Δfi = σi/Ni, with Ni being the number of original flux measurements in the i-th bin, and σi being their sample standard deviation. The overall trend of the rebinned spectrum supports the possibility of a rising continuum from λ ≳ 4 μm toward the mid-infrared, severely constraining the possibility of Capotauro being a strong line emitter galaxy (e.g., CEERS-93316).

2.4. SED-fitting setup

To obtain estimates of Capotauro’s physical properties in an extragalactic scenario, we performed photometry-only and spectrophotometric fits with three different SED-fitting codes: BAGPIPES (Carnall et al. 2018), CIGALE (Boquien et al. 2019), and ZPHOT (Fontana et al. 2000). Appendix D provides an in-depth review of our SED-fitting setup, which is designed to account for all possible galaxy solutions across the full redshift range, including interlopers that occupy a small redshift probability distribution’s volume, such as strong line emitters (see the discussion in Gandolfi et al. 2026).

To test the hypothesis of Capotauro being a Milky Way substellar object, we analyzed the source’s photometry using the Sonora Cholla cloudless chemical-equilibrium BD atmosphere models (Marley et al. 2021; Karalidi et al. 2021), covering ranges of 200 K < Teff < 2400 K in effective temperature, 3 < log g < 5.5 cm s−2 in surface gravity, 0.52 MJ < M < 108 MJ in mass (with MJ representing units of Jupiter masses), and log[M/H] = −0.5, 0, 0.5 in terms of metallicities in solar units, with all templates provided at a reference distance of 10 pc. Moreover, we performed a consistency check of the Sonora Cholla best-fit results by fitting the photometry of Capotauro with the ATMO 2020 template library for very cool BDs and self-luminous giant exoplanets (Phillips et al. 2020). These templates span ranges of 200 K < Teff < 3000 K in effective temperature, 2.5 < log g < 5.5 cm s−2 in surface gravity, 1.05 MJ < M < 78.57 MJ in mass and solar metallicity.

3. Results

3.1. Capotauro as a brown dwarf

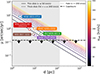

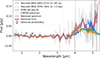

Milky Way substellar objects such as cold BDs exhibit strong molecular absorption features that can induce sharp NIR breaks. To assess whether Capotauro could be a galactic interloper, we first examined its morphology in the F444W band (where the source has the highest S/N ratio) to check if it is significantly resolved. Using the petrofit (Geda et al. 2022), GALFIT (Peng et al. 2002), and GALIGHT (Ding et al. 2021) codes, we independently found that Capotauro’s F444W light distribution is typically fitted by an empirical PSF-convolved Sérsic profile (Sérsic 1963) with half–light radius larger than the PSF (re = 0.05″ − 0.07″) and nonzero best-fit ellipticities up to e ∼ 0.9. However, these values are typically unconstrained (as are the Sersic index n and the concentration), as it is demonstrated by the fact that they can be comparably well reproduced by a simple point spread function3 (PSF). Appendix C details this procedure, while we show in Figure C.1 the F444W segmentation map of Capotauro retrieved by petrofit compared to the simulated band’s PSF. To further check if Capotauro is resolved in the F444W band, we also compared its radial profile4 to 89 F444W PSF sources that were injected into the F444W image and rescaled to match its flux (originally 100, with 11 excluded due to overlapping with extended sources), as well as to a spectroscopically confirmed F444W-detected BD (JWST/NIRSpec MSA ID 1558; Holwerda et al. 2024). All such radial profiles were measured in circular apertures. Within 0.15″ from its center, Capotauro displays spatial anisotropy, departing from typical PSF or BD profiles at a 1–2σ level (see Fig. 2, top left panel). We therefore conclude that these tests are statistically inconclusive, due to the extreme faintness of the object, that prevents us from definitely measuring its spatial extent.

|

Fig. 2. Top Left: Radial profile of Capotauro re-centered to its brightest pixel (black line) compared to the median profile of 89 empirical PSF sources injected in the F444W image and flux-matched to Capotauro (in blue; the shaded area represents the 25–75 percentile range of the 89 profiles). An empirical CEERS F444W PSF profile (red line) is also displayed, as well as a spectroscopically confirmed F444W-detected BD in CEERS (green dashed line; JWST/NIRSpec MSA ID 1558; Holwerda et al. 2024). Uncertainties are calculated as the standard error on the mean flux within concentric 1 px annuli. Top Right: Lower limit on Capotauro’s break strength (dashed orange line) compared to that of the Sonora Cholla cloudless BD atmosphere models (circles) for different effective temperatures, color-coded by their surface gravity value (i.e., log g). Bottom: Rescaled F356W fluxes of the 41 χred2 < 2 Sonora Cholla BD templates versus their effective temperature, color-coded by surface gravitational acceleration. These templates are compared to Capotauro’s 1σ upper limit (orange dashed line). For reference, we provide Capotauro’s ATMO BD template best-fit temperature (T = 300 K), represented as a black dotted line. |

To further evaluate the substellar object hypothesis, we performed fits to Capotauro’s photometry using the Sonora Cholla library described in Section 2.4. To assess which templates could reproduce Capotauro’s sharp break, we computed its break strength as the flux ratio bs = (fF444W + fF410M)/2/fF356W, with fi being the flux within a certain band. Since Capotauro is non detected in the F356W band, we adopted as the 1σfF356W flux estimate the error on Capotauro’s F356W flux measurement. Doing this, we obtain as a lower limit on the break strength the value bs ≥ 15.5. Among 1131 templates, 306 satisfy this threshold, favoring low-temperature (Teff < 600 K) and low-mass (M ≲ 63 MJ) BDs (Fig. 2, top right panel).

We then fitted the 306 valid templates to Capotauro’s F410M and F444W detections following the approach of Nonino et al. (2023). For each template, synthetic fluxes were scaled via bounded scalar minimization in log space (scipy.optimize.minimize_scalar) to match Capotauro’s fluxes, minimizing the reduced χ2, with bounds of ±6 dex around an initial flux-ratio estimate. Eventually, 156/306 templates yielded χred2 < 2, showing how the fit remains highly degenerate due to limited photometric constraints. However, only 41 of the 156 templates with χred2 < 2 predict F356W fluxes equal or below Capotauro’s F356W 1σ upper limit (see Figure 2, bottom panel). These templates predict rather unconstrained surface gravity accelerations (between 3.25 and 5.5 in cm s−2) and masses (between 1 and 63 MJ), as well as effective temperatures always below 400 K, which would place Capotauro in the Y BD class (i.e., the coldest class possible for BDs, with temperatures between 200 and 500 K; Cushing et al. 2011). Indeed, models with Teff > 450 K predict rising SEDs toward the blue, violating Capotauro’s F115W 1σ limit. This best-fit temperature range is confirmed by photometry fits performed exploiting the ATMO 2020 library, whose best-fit template (displayed in Figure 3) is characterized by Teff = 300 K (and log g = 5.5 cm s−2, although this parameter is almost unconstrained by our fits), which would put Capotauro on the cusp between the Y2 (∼300 − 350 K) and Y3 (∼250 − 300 K) BD subclasses. However, if presently known Y2 and Y3 BDs are typically found at distances ≲20 pc (e.g., Dupuy & Kraus 2013; Luhman et al. 2014), our best-fit routines return distances between 127 pc and 1.8 kpc.

|

Fig. 3. Capotauro’s CAPERS spectrum (gray line) and rebinned spectrum (see Figure 1) with HST and JWST/NIRCam photometry (black circles, with 1σ upper limits depicted as triangles) compared to our best-fit ATMO 2020 template (Phillips et al. 2020; blue line). For comparison, we report the JWST/NIRSpec PRISM spectrum of the coldest known BD WISE J0855-0714 (Luhman et al. 2024; green line) and of the Y0 BD WISE 0359-5401 (Beiler et al. 2023; orange line) rescaled to match Capotauro’s JWST/NIRCam photometry (from d ∼ 2.28 pc to d ∼ 307 pc and from d ∼ 13.6 pc to d ∼ 1.1 kpc respectively). |

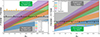

Furthermore, we assessed constraints on Capotauro’s proper motion using a 2.3 yr baseline between the CEERS JWST/NIRCam imaging (December 2022) and CAPERS JWST/NIRSpec spectroscopy (March 2025). The synthetic photometry extracted from the PRISM spectrum in Capotauro’s detection bands is brighter of a factor 1.47 ± 0.37 (F410M) and 1.39 ± 0.16 (F444W), indicating a ≤2.5σ consistency between the two epochs, which aligns with typical spectrophotometric discrepancies observed in other similar analysis (see, e.g., Roberts-Borsani et al. 2024). The absence of significant spectrum–photometry flux loss (consistent within the errors with a constrained JWST/NIRSpec source centering) leads us to adopt the slitlet long side reduced by 0.072″ as the source’s proper motion upper limit, giving μ ≲ 0.137″ yr−1.

Figure 4 details a comparison between this estimate and the proper motion of six known Y BDs and the expected proper motions for different dynamical regimes (i.e., thin disk, thick disk and galactic halo). Such comparison shows how the estimated proper motion for Capotauro is sensibly lower than the proper motion of other known similarly cold BDs and in general agreement with our estimated distances in the range 102 − 103 pc.

|

Fig. 4. Upper limit on Capotauro’s proper motion (black dashed line) compared to that of other known Y BDs as function of their distance (colored circles). The colored lines show the relation μ = vtan/(4.74 d) for different galactic components: thin disk (vtan ≤ 50 km s−1, solid), thick disk (50 < vtan ≤ 200 km s−1, dashed), and halo (vtan > 200 km s−1, dotted). The color scale indicates the different values of vtan. The gray shaded area represents distance values excluded by the best-fit flux normalization. |

Finally, to estimate how rare a substellar object with Teff ∼ 300 K at d ≳ 130 pc would be in the area covered by the CEERS JWST/NIRCam F444W image, we performed a first-order calculation using the empirical relations Teff(SpT) and MW2(SpT) from Kirkpatrick et al. (2021). Here, SpT is a numeric index associated to the BD’s spectral type, while MW2 represents the WISE W2 band absolute magnitude, with a pivot wavelength (∼4.6 μm) approximating JWST/NIRCam F444W’s one. We then normalized the local density by counting BDs per subtype within 20 pc (i.e., the reference distance exploited by Kirkpatrick et al. 2021) and assumed a vertical exponential density profile ρ(z) = ρ0 e−|z|/h with scale height h = 225 pc, consistent with previous estimates for cold BDs (e.g., Robin et al. 2003; van Vledder et al. 2016) and calibrated by matching the number of Y0-type BDs observed in the COSMOS field (Chen et al. 2025). For each BD subtype, we also computed the maximum detection distance dmax at which its apparent magnitude reaches the 5σ CEERS F444W depth (see Table A.1). We then integrated ρ(z) up to dmax to compute the effective volume probed by the survey. At the galactic latitudes typical of CEERS, this computation yields an expected number of Y2 BDs (i.e., Teff ∼ 320 K) of ∼0.02 and a detection probability of P(≥1)∼2.2%, while for Y3 BDs (i.e., Teff ∼ 280 K) we obtain an expected number of ∼0.01 and a detection probability of P(≥1)∼0.9%. Table 1 subsumes the salient findings of this section.

Estimated properties of Capotauro in a Milky Way substellar scenario.

3.2. Capotauro as a free-floating exoplanet

The mass spectrum allowed by the remaining viable Sonora Cholla templates discussed in Section 3.1 comprises substellar objects with mass ≤13 MJ. For an object with solar metallicity, such mass is insufficient to trigger deuterium fusion, the hallmark process that defines BDs. According to the definition adopted by the International Astronomical Union, such an object would therefore not qualify as a BD, but rather as a free-floating gaseous exoplanet (i.e., an exoplanet not associated to any star). Indeed, JWST/NIRISS already detected six rogue planet candidates in NGC 1333, a reflection nebula at ∼300 pc from Earth (Langeveld et al. 2024), but with temperature between 1500 and 2500 K. However, according to simulations, JWST could in principle detect via direct NIR imaging free-floating exoplanets with Teff ≤ 500 K, which could exhibit F444W fluxes of the same order magnitudes of Capotauro (Pacucci et al. 2013). This source could thus be the first example of this class of substellar objects. After having analyzed the properties of Capotauro in a Milky Way object scenario, we proceeded to characterize this source under the hypothesis that it is a galaxy.

3.3. Capotauro as a z ∼ 30 galaxy

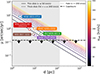

Our first SED-fitting runs with galactic templates and models were performed adopting open redshift priors for BAGPIPES, Cigale, and ZPHOT following the configurations described in Section 2.4. For our BAGPIPES runs, we fitted both the photometry alone as well as a combination of both photometry and the available spectrum. For this latter fit, we masked the CAPERS spectrum of Capotauro in the λ range 3.9 μm ≤ λ ≤ 4.1 μm to exclude the noise spike present in this part of the spectrum (see Figure 1).

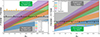

Regardless of the code or setup adopted in the extragalactic scenario, all our configurations consistently recover a primary solution for Capotauro at z ∼ 32, yielding compatible best-fit estimates in terms of redshift (both in the photometry-only and spectrophotometric fits). This solution is consistent with interpreting the apparent rise in the CAPERS spectrum of Capotauro at λ > 4 μm, combined with the nondetection in the JWST/NIRCam bands at λ < 4 μm, as the signature of an extreme Lyman-break galaxy, with the break located between the F356W and F410M bands (see Figure 5). The estimated rest-frame ultraviolet (UV) luminosity is MUV ∼ −21.5. Not surprisingly, the detection probability of such a bright ultra high-z object within the CEERS survey volume is extremely low, amounting to ∼10−7 (when integrating z ∼ 30 predictions of the UV luminosity function by Yung et al. 2024a, without enhancements) or even ∼10−3 (adjusting the z ∼ 30 UV luminosity function predicted by Yung et al. 2024a for a top-heavy IMF boost and stochastic star-formation variability so to reproduce the object’s brightness at these extremely high redshifts). We note that if the tentative 3.63 μm line were real, a solution at z ∼ 29 could remain viable by interpreting this feature as Lyman-α emission.

|

Fig. 5. Left panel: Results of our open-redshift SED-fitting runs based on Capotauro’s photometry. Observed fluxes (black dots; 1σ limits as triangles) are compared to the best-fit SEDs from BAGPIPES (red), CIGALE with a Dale et al. (2014) AGN component (yellow), and ZPHOT (purple). The red diamonds indicate synthetic photometry from the BAGPIPES fit. The gray line shows Capotauro’s spectrum from the CAPERS survey. The inset shows the P(z) distributions from all three codes (linear scale). Right panel: Normalized logarithmic redshift probability distribution yielded by BAGPIPES (red), CIGALE (yellow), and ZPHOT (purple). The black dashed line represents the average best-fit redshift between our BAGPIPES, CIGALE, and ZPHOT runs. We report redshift values of secondary P(z) peaks for CIGALE and ZPHOT. |

Despite the consistent primary peak at z ∼ 31.7, there are a number of lower-probability z < 15 solutions for Capotauro that we characterize in the following sections, with ZPHOT predicting the highest z < 10 solution volume due to the nature of the libraries exploited by the code.

Due to the limited number of detections available, most physical parameters derived from SED fitting are only loosely constrained. Nevertheless, the best-fit stellar masses are consistently found to be ≲109.5 M⊙ within 1σ uncertainties, with good agreement between BAGPIPES and CIGALE (whereas ZPHOT returns an unconstrained estimate). The dust attenuation parameter AV exhibits a large scatter, with best-fit values consistent with zero within 2σ in each of the fitting codes, including our BAGPIPES runs adopting both the Calzetti et al. (2000) attenuation model and the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) law (Prevot et al. 1984; Bouchet et al. 1985). Similarly, star formation history (SFH)-related best-fit parameters – including the metallicity, τdel (or tmax in the case of a log-normal SFH), and the derived star formation rate – remain poorly constrained, independently of the assumed SFH. In our BAGPIPES runs, we explored both a delayed-exponential SFH (e.g., Ciesla et al. 2017; Chevallard et al. 2019) and a log-normal one (e.g., Diemer et al. 2017; Cohn 2018), always recovering a compatible best-fit redshift within the errors.

The CIGALE fit including an AGN component supports the z ∼ 31.7 solution using both the Dale et al. (2014) and Skirtor (Stalevski et al. 2012, 2016) AGN models. The best-fit AGN fraction, defined respectively as the AGN contribution to the total infrared luminosity in the 8–1000 μm range (Dale et al. 2014) and to the total luminosity at 4000 Å (Skirtor), is poorly constrained, spanning ∼10 − 70% within 1σ for both AGN models. We report the best-fit photometry-only redshift estimates in Table 2, and we display in the left panel of Figure 5 the open-priors best-fit SEDs for our BAGPIPES, CIGALE, and ZPHOT runs. The expected photometry from our BAGPIPES best-fit SED is represented as red diamonds. This shows how in such z ∼ 31.7 solution, Capotauro’s flux in the F410M and F444W bands is tracing the galaxy’s Lyman break, while the expected JWST/MIRI photometry is consistent with the available JWST/MIRI upper limits. Finally, the right panel of Figure 5 shows the redshift probability distribution P(z) for all of our runs.

BAGPIPES, CIGALE and ZPHOT photometry-only best-fit results adopting open redshift priors.

3.4. Capotauro as a dusty/Balmer break galaxy at z < 10

Even if our SED-fitting runs with open redshift priors allocate only ∼0.5% of the total P(z) integrated probability density to z < 25 solutions for Capotauro, we still aim to characterize these secondary solutions to discuss their likelihood, physical consistency and potential interest.

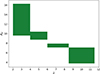

The question arises of whether dust alone can reproduce at z < 10 Capotauro’s infrared colors. To check this, we exploited the SWIRE template library (Polletta et al. 2007), which consists of a broad range of empirical SEDs for star-forming and active galaxies. Each template was dust-attenuated using the Calzetti et al. (2000) extinction law with varying AV values from 0 to 20, redshifted to five representative values (z = 1, 3, 5, 7, 10), and convolved with the JWST/NIRCam and MIRI transmission curves (F356W, F444W, F770W). For each case, we computed synthetic photometry and derived the color tracks as a function of dust attenuation. In Fig. 6, we show the ranges of F356W-F444W and F444W-F770W colors spanned by all dust-attenuated SWIRE templates for the selected redshifts.

|

Fig. 6. Left: F356W-F444W colors of the SWIRE library templates (Polletta et al. 2007) dust-attenuated following the (Calzetti et al. 2000) law for different reference redshifts vs. Av. Each colored region spans the variability of the templates within the library. The orange horizontal dashed line indicates the observed 1σ lower limit for Capotauro’s color, while the dashed black line represents the 3σ estimate. The shaded gray areas mark the color space incompatible with the observed constraints. Right: Same, but for the F444W-F770W color. The orange and black dashed lines represent the observed 1 and 3σ upper limits for Capotauro’s color. |

Adopting 1σ upper limits for the nondetections in F356W and F770W (orange dashed line in Figure 6), the results show that no combination of SWIRE templates, redshift (z ≤ 10), and dust attenuation can simultaneously satisfy both color conditions. Instead, adopting 3σ upper limits for the nondetections in F356W and F770W (black dashed line in Figure 6), the allowed parameter space increases, though still requiring extremely high dust attenuations at all redshifts. The parameter space allowed for SWIRE templates under these 3σ limits is shown in Figure 7 (green regions).

|

Fig. 7. Allowed (z, AV) parameter space for the dust-attenuated SWIRE templates adopting 3σ upper limits for the nondetections in F356W and F770W. Only combinations falling within the green regions simultaneously satisfy the two color constraints reported in Figure 6. |

Nonetheless, we utilized our BAGPIPES setup to perform photometric fitting of Capotauro fixing the redshift at all main secondary P(z) values predicted by our open-prior run (see Figure 5), namely z = 1.275, 3.6, 5.2, 7.65, 8.775, 9.45, retrieved using scipy’s find_peaks function. During these new BAGPIPES runs, we exploited the same priors of our previous run (see Table D.1), with the exception of the prior range on the dust attenuation index, now extended to Av = [0, 20].

Consistent with our simulations using the SWIRE template library, we obtain that lower-z solutions require extremely high Av values (up to Av ∼ 16.5 at z ∼ 1.3) to match Capotauro’s photometry. Interestingly, we note how the z ∼ 8.775 solution interprets the ∼3.6 μm bump observed in the CAPERS PRISM spectrum as [O II] λ3727 emission. However, we find that all our best-fit dusty z ≤ 10 SEDs are in tension with the 3σ F356W upper limits (as well as at the 1σ level with the bluer JWST/MIRI bands; see Fig. 8).

|

Fig. 8. Best-fit BAGPIPES SEDs at fixed redshifts z = 1.275, 3.6, 5.2, 7.65, 8.775, and 9.45 (colored lines, with synthetic photometry as matching diamonds) with best-fit Av values (using the prior range Av = [0, 20]) for a delayed SFH and a Calzetti dust law. Capotauro’s photometry is shown as black circles and the 1σ upper limits as triangles; the CAPERS spectrum is in gray. |

We wanted to determine whether a mix of Balmer break and dust can reproduce at z < 10 Capotauro’s infrared colors. The z = 9.4 secondary solution interprets Capotauro’s declining continuum as a combination of dust attenuation and a pronounced Balmer break, appearing as a sharp flux drop at λ ∼ 3.7 μm. Such a feature could be naturally produced by a stellar population that has assembled a substantial fraction of its mass within a few hundred million years. However, this solution is at a 3σ tension with Capotauro’s F356W upper limit. Interestingly, Capotauro has also been independently selected as a candidate passive galaxy in Merlin et al. (2025), based on SED-fitting using a custom library of templates limited at z < 15. Their best-fit solution places the source at z = 9.83, with log10(M*/M⊙)∼11.6, negligible ongoing star formation, and a burst-like SFH. However, the libraries used for this fit assume a redshift upper limit up to z = 20, preventing the z = 31.7 solution from being identified. The overall result is that this fit implies extreme parameters to recover Capotauro’s photometric properties, including very high metallicity (Z = 2.5 Z⊙) and significant dust reddening (E(B − V) = 1), and most importantly fails again to reproduce the F356W nondetection.

3.5. Capotauro as a strong line emitter galaxy

The question here is whether strong emission lines can power the extreme infrared colors of Capotauro? In principle, our choice of a broad prior on the ionization parameter (extending up to log U = −1) and the use of a large number of live points (nlive = 5000) in our BAGPIPES runs should be sufficient to uncover potential strong-line emitter solutions (see Appendix D and the discussion in Gandolfi et al. 2026). However, to further test this possibility, we constructed a grid of emission-line-augmented models based on the SWIRE template library. For each template, we added a single gaussian emission line (e.g., Lyα, [OII], Hβ, [OIII], Hα) at rest-frame wavelengths, redshifted the full spectrum over a grid spanning z = 0.5 to 15.0 in steps of 0.1, and varied the rest-frame equivalent width of the line from 10 to 3000 Å. For each model, we computed the synthetic fluxes in the JWST/NIRCam F356W and F444W bands, and derived the corresponding F356W–F444W color. We then compared these colors to the observed constraint on Capotauro, defined by its F444W detection and F356W 1σ upper limit, highlighting the combinations of redshift and equivalent width that could match or exceed this color threshold. About 11 out of 25 SWIRE templates were able to produce a F356W-F444W color compatible with Capotauro’s; however all of these synthetic spectra were found to be inconsistent with the CAPERS spectrum of Capotauro within its 3σ flux uncertainties.

3.6. Capotauro as an AGN or a Little Red Dot

Our open-prior photometric CIGALE runs, i.e., the only ones accounting for an AGN component, were not able to constrain potential AGN contribution for Capotauro (see Sect. 3.3). However, AGN templates included in the SWIRE library are unable to reproduce Capotauro’s infrared colors (see the right panel of Fig. 9), even by accounting for the contribution of dust (see Sect. 3.4) up to z ≳ 27.

|

Fig. 9. Left: Capotauro’s photometry (black circles and black triangles indicating 1σ upper limits) and spectrum (gray line) are compared to the spectra of MoM-BH*-1 (blue), J0647–1045 (purple), the Cliff (pink), and CAPERS-LRD-z9 (green), respectively rescaled to z ∼ 8.92, z ∼ 9.24, z ∼ 9.22, and z ∼ 9.34. These redshifted spectra were also rescaled in flux by factors of ∼0.17, ∼0.22, ∼0.12, and ∼0.26, respectively, to match Capotauro’s photometric detections in the F410M and F444W bands. The F356W synthetic fluxes of each rescaled spectrum are displayed as colored diamonds, compared with Capotauro’s F356W 3σ upper limits (gray diamond) as a reference. The inset displays the measured Balmer break strengths for MoM-BH*-1 (blue circle), the Cliff (pink), CAPERS-LRD-z9 (green), and Capotauro’s lower limit (orange), computed as the ratio of the mean flux in the F444W and F410M bands to the flux in F356W. Right: F356W-F444W color of Capotauro, estimated using the 1σ upper limit from the nondetection in F356W (orange dashed line). A more conservative estimate, adopting the 1σ lower limit of the F444W flux measurement, is shown as a gray dashed line. The colors of MoM-BH*-1 (blue circle), the Cliff (pink), J0647–1045 (purple), and CAPERS-LRD-z9 (green) are compared to those of LRDs (estimated assuming UV/optical slopes within the range from Kocevski et al. 2025) as a function of redshift, along with the predicted AGN colors from the models of Polletta et al. (2007) (gray shaded area). |

The question is wether Capotauro could be instead a more peculiar kind of AGN, such as one of the LRDs for which the presence of a SMBH is strongly supported, for example, by very broad lines. The left panel of Figure 9 displays the spectrum of the LRD J0647-1045 (Killi et al. 2024), rescaled in redshift and flux normalization using a simple Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) routine, exploiting a Gaussian likelihood to maximally match Capotauro’s F410M and F444W detections. However, such rescaled spectrum is in tension with Capotauro’s photometry in multiple bands. We then analytically simulated a suite of 200 broken power-law SEDs, which approximate the typical v-shaped emission observed for LRDs in its transition from the UV to the optical regime. Our simulated v-shaped SEDs depend on two independent UV and optical spectral slopes sampled in the ranges βUV ∈ [ − 2.5, −1.5] and βopt ∈ [0.0, 2.5], as motivated by Kocevski et al. (2025). We computed synthetic photometry in the F356W and F444W JWST/NIRCam bands over a redshift range of 0 < z < 40, by redshifting the rest-frame SEDs and integrating them through the instrument throughput curves. The resulting model F356W−F444W color tracks were compared in the right panel of Figure 9 against observed color measurements for Capotauro: even at ultra-high-redshifts, the typical colors of LRDs are unable to reproduce Capotauro’s redness.

Finally, another intriguing possibility is that the potential Balmer break featured by Capotauro could arise from dense gas around an active black hole rather than solely from an evolved stellar population. In this scenario, Capotauro would be composed of a dust-free atmosphere surrounding a supermassive black hole. As discussed in Section 1, there are three notable spectroscopically confirmed candidates which are compatible with this scenario: the Cliff at zspec = 3.55 (de Graaff et al. 2025a), MoM-BH*-1 at zspec = 7.76 (Naidu et al. 2025a), and CAPERS-LRD-z9 at zspec = 9.288 (Taylor et al. 2025). All these objects exhibit exceptionally strong Balmer breaks difficult to explain with evolved stellar populations alone. These sources stand among the most extreme Balmer break galaxies in terms of their break’s strength. The left panel of Figure 9 illustrates how the spectrum of MoM-BH*-1, the Cliff and CAPERS-LRD-z9 can match Capotauro’s spectrophotometric detections, provided their spectra are rescaled in both redshift and flux. To compute the optimal values for these rescaling factors, we apply the same simple MCMC algorithm we exploited to match J0647-1045’s spectrum to Capotauro’s F410M and F444W detections, finding best-fit redshifts of zspec ∼ 8.92 (MoM-BH*-1), zspec ∼ 9.22 (the Cliff), and zspec ∼ 9.34 (CAPERS-LRD-z9), together with best-fit flux normalization factors of ∼0.17 (MoM-BH*-1), ∼0.12 (the Cliff), and ∼0.26 (CAPERS-LRD-z9). As discussed in Section 3.4, at z > 8 the tentative λ ∼ 3.6 μm feature could be reproduced by z ∼ 8.775 [O II] 3727 Å line emission, while only weak high-order Balmer lines near the series limit fall within the feature’s wavelength range. However, the rescaled SEDs of MoM-BH*-1, the Cliff and CAPERS-LRD-z9 all showcase a > 3σ tension with Capotauro’s F356W upper limit, indicating that the source’s break is too strong to be fully reproduced by these templates. To further assess this discrepancy, we compare Capotauro’s break strength to a consistent estimate of the Balmer break strengths (calculated as done in Section 3.1) of the Cliff, MoM-BH*-1, and CAPERS-LRD-z9 in the inset of Figure 9, left panel. This comparison reveals that even the extreme Balmer break of these three black hole star candidates is insufficient to match Capotauro’s break strength. Finally, we note that, although some estimates of z > 8 LRD number densities have appeared in the literature (e.g., Kocevski et al. 2025; Tanaka et al. 2025), there are only three known LRDs featuring strong Balmer breaks, which were found by independent surveys based on different selection criteria, making any expected detection probability for a Capotauro-like LRD essentially unconstrained.

4. Discussion and conclusion

This work presented Capotauro, a faint (mF444W ∼ 27) object characterized by an extreme F356W-dropout (mF356W − mF444W > 3) color identified in the CEERS field. We analyzed its properties utilizing the available information which includes deep photometry from ∼0.6 μm to ∼21 μm (which shows that the source is detected only in the two overlapping JWST/NIRCam bands F410M and F444W) and a R ∼ 100 spectrum obtained with JWST/NIRSpec in the framework of the CAPERS survey. Although the spectrum’s low S/N precludes a firm classification of the source, it nonetheless reveals a rising continuum redward of 4 μm, which suggests Capotauro’s pronounced dropout signature is produced by a spectral break. At the same time, the spectrum rules out prominent emission lines as the origin of the F410M and F444W detections, while also enabling us to constrain the source’s proper motion over a temporal baseline of 2.3 yr.

With these data, we have explored several options regarding Capotauro’s nature, including both a Milky Way or an extragalactic origin. Below, we review and discuss each of the scenarios considered in light of our analysis. Although we do not have enough data to draw a firm conclusion on the nature of Capotauro, our analysis shows that this source is extreme and intriguing in every possibility here examined.

-

Galactic object. To explore the possibility of Capotauro being a Milky Way substellar object, we conducted a morphological analysis of its F444W image (Section 3.1). Despite a slight anisotropy in the radial profile shown in Figure 2 (which could be hindered by noise affecting source centering accuracy) and modest extension in the F444W segmentation map from our petrofit run (Figure C.1), we cannot claim that Capotauro is clearly resolved. Furthermore, whether the object appears only barely resolved or completely unresolved offers no clear discrimination between the Milky Way and the extragalactic object scenario. If high-z or lower-z compact galaxies may appear unresolved, BDs in binary systems (e.g., Opitz et al. 2016; Calissendorff et al. 2023; De Furio et al. 2023, albeit with a decreasing binary likelihood for colder BDs; Fontanive et al. 2018) or surrounded by rings or debris disks (e.g., Zakhozhay et al. 2017, 2023, with no known Y-type BD to date exhibiting these features) might appear marginally resolved. Therefore, by failing to reveal a clear spatial extension, our morphological test remains inconclusive. To further explore the scenario that sees Capotauro as a Milky Way substellar object, we exploited two different BD template sets: the Sonora Cholla photometric grid and the ATMO 2020 spectral library. In both cases, we found that Capotauro’s SED is well reproduced by cool (< 400 K) galactic objects. The best-fit templates indicate temperatures as cold as Teff ≲ 300 K (implying an advanced age) and a distance of at least d ≳ 127 pc, possibly surpassing kiloparsec scales. The fact that Capotauro could be a thick disk or galactic halo member is compatible with the proper motion upper limit we derived. This would make Capotauro as comparably cold as the coldest known BD (i.e., WISE J0855-0714; Teff = 285 K; d ∼ 2.28 pc; Luhman 2014; Skemer et al. 2016; Zapatero Osorio et al. 2016; Kühnle et al. 2025), but at a distance ≳56 times larger, potentially exhibiting a record-breaking combination of coldness and distance. Moreover, the inferred mass spectrum allowed by the best-fit templates allows Capotauro to be a distant free-floating exoplanet (Section 3.2). If true, this would be the first confirmation through direct imaging of a terrestrial-temperature free-floating exoplanet at > 100 pc. Our analysis has also provided an upper limit on the proper motion of the source, which appears significantly lower than the one of other known Y BDs (Figure 4), implying either large distances or low tangential velocities, or a combination of both. Indeed, the CEERS line of sight lies at high Galactic latitude (b ∼ +60°), implying a reduced contribution of thin disk substellar populations and favoring the likelihood of Capotauro rather being a thick disc or galactic halo member, thus favoring distances well beyond the lower bound of d = 127 pc. Finally, the exceedingly low probability (≲3%) of detecting in CEERS a substellar object with the physical properties inferred from our template fitting confirms that, if Capotauro is a Milky Way object, it represents a rare and surprising discovery in this field.

-

Atypicalz < 10 galaxy. Another possibility is that Capotauro is a lower-redshift interloper exhibiting a highly peculiar combination of physical features: a pronounced Balmer break, strong dust attenuation, AGN and/or extreme line emission, all maintaining a negligible continuum at λ ≲ 3 μm. Within our framework – constructed to encompass a wide variety of possible z < 10 interlopers – no combination of parameters succeeds in reproducing Capotauro’s infrared SED. Nevertheless, should Capotauro truly be a z < 10 galaxy, it would likely trace an unrecognized class of interlopers, whose identification would aid in refining high-redshift surveys. Moreover, its properties could offer valuable insights into dust production and Balmer break formation in exotic systems. In this sense, a particularly intriguing possibility is that Capotauro may belong to the newly revealed population of strong Balmer-break LRDs (MoM-BH*-1, the Cliff and CAPERS-LRD-z9). Despite the lack of flexible modeling for this class of sources in current SED-fitting codes, our analysis shows that the spectra of the few known examples fail to fully reproduce our source’s photometry. In this scenario, Capotauro would display the deepest break in the small existing sample of such objects, likely lying at 8 ≲ z ≲ 10 so that its Balmer break would fall between F356W and F410M, making it a uniquely extreme LRD.

-

Galaxy atz ∼ 30. Finally, if Capotauro is indeed a galaxy at z ∼ 30, it would constitute a major breakthrough in the field of galaxy formation and evolution. The inferred photometric redshift corresponds to a cosmic age of only ∼100 Myr, requiring rapid structure formation in the early Universe (see, e.g., Maio et al. 2009). This would have deep implications for our understanding of early star formation, feedback physics, black hole seeding (Barkana & Loeb 2001; Pacucci & Loeb 2022; Fan et al. 2023) and possibly the nature of dark matter and dark energy (Menci et al. 2020; Gandolfi et al. 2022; Maio & Viel 2023; Santini et al. 2023; Dayal & Giri 2024; Yung et al. 2024b, 2025). Moreover, the rest-frame UV luminosity5 of Capotauro in its z ∼ 30 solution is comparable to some of the most distant sources known to date (e.g, GNz11, Oesch et al. 2016 or GSz14 Carniani et al. 2024). If Capotauro would be unexpectedly bright if compared to state-of-the-art UV luminosity function models of both early galaxies and primordial black holes at z ∼ 30 (e.g., Ferrara et al. 2023; Matteri et al. 2025), such luminosity could be reproduced with an IMF boost and MUV scatter linked to bursty star formation (Yung et al. 2024b, 2025) or by early AGN activity. If confirmed by future observations, which are indeed pivotal to better characterize this source, Capotauro’s brightness could be exploited to test current assumptions about the expected physical properties of luminous objects at the epoch of Cosmic Dawn.

In summary, although the current data do not allow a definitive and unambiguous characterization of the nature of Capotauro, this source results exceptional and puzzling from all considered perspectives, with properties that could lead to theoretical and/or observational breakthroughs. The present analysis aims to compile exhaustively the current knowledge on this intriguing source, offering a foundation for future follow-up efforts.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous referee for the insightful comments and suggestions. G. G., G. R., A. G., and B. V. are supported by the European Union – NextGenerationEU RFF M4C2 1.1 PRIN 2022 project 2022ZSL4BL INSIGHT. A. K. and B. E. B. gratefully acknowledge support from grant JWST-GO-03794.001. P. S. acknowledges support from INAF Large Grant 2024 “UNDUST: UNveiling the Dawn of the Universe with JWST” and INAF Mini Grant 2022 “The evolution of passive galaxies through cosmic time”. M. C. acknowledges financial support by INAF Mini-grant “Reionization and Fundamental Cosmology with High-Redshift Galaxies”, and by INAF GO Grant “Revealing the nature of bright galaxies at cosmic dawn with deep JWST spectroscopy”. M. G. acknowledges support from INAF under the following funding schemes: Large Grant 2022 (project “MeerKAT and LOFAR Team up: a Unique Radio Window on Galaxy/AGN co-Evolution”) and Large GO 2024 (project “MeerKAT and Euclid Team up: Exploring the galaxy-halo connection at cosmic noon”). We thank A. Ferrara, C. Gruppioni and G. Roberts-Borsani for the deep and stimulating insights. We thank H. Kühnle and V. Squicciarini for the helpful discussions on Capotauro possibly being a Milky Way object.

References

- Anders, P., & Fritze-v Alvensleben, U. 2003, A&A, 401, 1063 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Arrabal Haro, P., Dickinson, M., Finkelstein, S. L., et al. 2023, Nature, 622, 707 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Austin, D., Adams, N., Conselice, C. J., et al. 2023, ApJ, 952, L7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, B. E., Kirkpatrick, A., Yang, G., et al. 2025, AJ, 170, 300 [Google Scholar]

- Barkana, R., & Loeb, A. 2001, Phys. Rep., 349, 125 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barro, G., Pérez-González, P. G., Kocevski, D. D., et al. 2024, ApJ, 963, 128 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beiler, S. A., Cushing, M. C., Kirkpatrick, J. D., et al. 2023, ApJ, 951, L48 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, E., & Arnouts, S. 1996, A&AS, 117, 393 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, E., Mellier, Y., Radovich, M., et al. 2002, ASP Conf. Ser., 281, 228 [Google Scholar]

- Bisigello, L., Gandolfi, G., Grazian, A., et al. 2023, A&A, 676, A76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bisigello, L., Gandolfi, G., Feltre, A., et al. 2025, A&A, 693, L18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bisigello, L., Gandolfi, G., Grazian, A., et al. 2026, A&A, in press, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556903 [Google Scholar]

- Boquien, M., Burgarella, D., Roehlly, Y., et al. 2019, A&A, 622, A103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet, P., Lequeux, J., Maurice, E., Prevot, L., & Prevot-Burnichon, M. L. 1985, A&A, 149, 330 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Bruzual, G., & Charlot, S. 2003, MNRAS, 344, 1000 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burgasser, A. J., Bezanson, R., Labbe, I., et al. 2024, ApJ, 962, 177 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Calissendorff, P., De Furio, M., Meyer, M., et al. 2023, ApJ, 947, L30 [Google Scholar]

- Calzetti, D., Armus, L., Bohlin, R. C., et al. 2000, ApJ, 533, 682 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carnall, A. C., McLure, R. J., Dunlop, J. S., & Davé, R. 2018, MNRAS, 480, 4379 [Google Scholar]

- Carniani, S., Hainline, K., D’Eugenio, F., et al. 2024, Nature, 633, 318 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M., Sommariva, V., Fontana, A., et al. 2014, A&A, 566, A19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M., Fontana, A., Treu, T., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, L15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M., Fontana, A., Merlin, E., et al. 2025, A&A, 704, A158 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrier, G. 2003, PASP, 115, 763 [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A. Y. A., Goto, T., Wu, C. K. W., et al. 2025, PASA, 42, e042 [Google Scholar]

- Chevallard, J., Curtis-Lake, E., Charlot, S., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 483, 2621 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla, L., Elbaz, D., & Fensch, J. 2017, A&A, 608, A41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla, L., Elbaz, D., Ilbert, O., et al. 2024, A&A, 686, A128 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, J. D. 2018, MNRAS, 478, 2291 [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, M. C., Kirkpatrick, J. D., Gelino, C. R., et al. 2011, ApJ, 743, 50 [Google Scholar]

- Dale, D. A., Helou, G., Magdis, G. E., et al. 2014, ApJ, 784, 83 [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M., Guhathakurta, P., Konidaris, N. P., et al. 2007, ApJ, 660, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dayal, P., & Giri, S. K. 2024, MNRAS, 528, 2784 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- De Furio, M., Lew, B., Beichman, C., et al. 2023, ApJ, 948, 92 [Google Scholar]

- de Graaff, A., Rix, H.-W., Naidu, R. P., et al. 2025a, A&A, 701, A168 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- de Graaff, A., Setton, D. J., Brammer, G., et al. 2025b, Nat. Astron., 9, 280 [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, A., Sarkar, K. C., Birnboim, Y., Mandelker, N., & Li, Z. 2023, MNRAS, 523, 3201 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer, B., Sparre, M., Abramson, L. E., & Torrey, P. 2017, ApJ, 839, 26 [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X., Birrer, S., Treu, T., & Silverman, J. D. 2021, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2111.08721] [Google Scholar]

- Donnan, C. T., McLeod, D. J., Dunlop, J. S., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 518, 6011 [Google Scholar]

- Donnan, C. T., Dickinson, M., Taylor, A. J., et al. 2025, ApJ, 993, 224 [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, T. J., & Kraus, A. L. 2013, Science, 341, 1492 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Euclid Collaboration (Bisigello, L., et al.) 2026, A&A, in press, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554537 [Google Scholar]

- Euclid Collaboration (Dominguez-Tagle, C., et al.) 2025, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2503.22442] [Google Scholar]

- Euclid Collaboration (Mohandasan, A., et al.) 2025, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2503.22559] [Google Scholar]

- Euclid Collaboration (Weaver, J. R., et al.) 2025, A&A, 697, A16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Euclid Collaboration (Žerjal, M., et al.) 2026, A&A, in press, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556980 [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X., Bañados, E., & Simcoe, R. A. 2023, ARA&A, 61, 373 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferland, G. J., Chatzikos, M., Guzmán, F., et al. 2017, Rev. Mex. Astron. Astrofis., 53, 385 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, A., Pallottini, A., & Dayal, P. 2023, MNRAS, 522, 3986 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, A., Pallottini, A., & Sommovigo, L. 2025, A&A, 694, A286 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. L., Bagley, M. B., Ferguson, H. C., et al. 2023, ApJ, 946, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. L., Leung, G. C. K., Bagley, M. B., et al. 2024, ApJ, 969, L2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. L., Bagley, M. B., Arrabal Haro, P., et al. 2025, ApJ, 983, L4 [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A., D’Odorico, S., Poli, F., et al. 2000, AJ, 120, 2206 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanive, C., Biller, B., Bonavita, M., & Allers, K. 2018, MNRAS, 479, 2702 [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi, G., Lapi, A., Ronconi, T., & Danese, L. 2022, Universe, 8, 589 [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi, G., Rodighiero, G., Bisigello, L., et al. 2026, A&A, accepted [arXiv:2502.02637] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, J. P., Mather, J. C., Clampin, M., et al. 2006, Space Sci. Rev., 123, 485 [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, J. P., Mather, J. C., Abbott, R., et al. 2023, PASP, 135, 068001 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Geda, R., Crawford, S. M., Hunt, L., et al. 2022, AJ, 163, 202 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J. E., Setton, D. J., Furtak, L. J., et al. 2025, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2509.05434] [Google Scholar]

- Grogin, N. A., Kocevski, D. D., Faber, S. M., et al. 2011, ApJS, 197, 35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guia, C. A., Pacucci, F., & Kocevski, D. D. 2024, Res. Notes AAS, 8, 207 [Google Scholar]

- Hainline, K. N., Helton, J. M., Johnson, B. D., et al. 2024, ApJ, 964, 66 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hainline, K. N., Helton, J. M., Miles, B. E., et al. 2025, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2510.00111] [Google Scholar]

- Harikane, Y., Ouchi, M., Oguri, M., et al. 2023, ApJS, 265, 5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Holwerda, B. W., Hsu, C.-C., Hathi, N., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 529, 1067 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hviding, R. E., de Graaff, A., Miller, T. B., et al. 2025, A&A, 702, A57 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Karalidi, T., Marley, M., Fortney, J. J., et al. 2021, ApJ, 923, 269 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Killi, M., Watson, D., Brammer, G., et al. 2024, A&A, 691, A52 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, J. D., Gelino, C. R., Faherty, J. K., et al. 2021, ApJS, 253, 7 [Google Scholar]

- Kocevski, D. D., Finkelstein, S. L., Barro, G., et al. 2025, ApJ, 986, 126 [Google Scholar]

- Koekemoer, A. M., Faber, S. M., Ferguson, H. C., et al. 2011, ApJS, 197, 36 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kokorev, V., Caputi, K. I., Greene, J. E., et al. 2024, ApJ, 968, 38 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kokorev, V., Chávez Ortiz, Ó. A., Taylor, A. J., et al. 2025, ApJ, 988, L10 [Google Scholar]

- Kron, R. G. 1980, ApJS, 43, 305 [Google Scholar]

- Kühnle, H., Patapis, P., Mollière, P., et al. 2025, A&A, 695, A224 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lambrides, E., Garofali, K., Larson, R., et al. 2024, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2409.13047] [Google Scholar]

- Langeroodi, D., & Hjorth, J. 2023, ApJ, 957, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Langeveld, A. B., Scholz, A., Mužić, K., et al. 2024, AJ, 168, 179 [Google Scholar]

- Lapi, A., Gandolfi, G., Boco, L., et al. 2024, Universe, 10, 141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett, S. K. 2024, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2409.06158] [Google Scholar]

- López, I. E., Yang, G., Mountrichas, G., et al. 2024, A&A, 692, A209 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, C. C., Vijayan, A. P., Thomas, P. A., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 500, 2127 [Google Scholar]

- Luhman, K. L. 2014, ApJ, 786, L18 [Google Scholar]

- Luhman, K. L. 2025, MNRAS, 542, L126 [Google Scholar]

- Luhman, K. L., Morley, C. V., Burgasser, A. J., Esplin, T. L., & Bochanski, J. J. 2014, ApJ, 794, 16 [Google Scholar]

- Luhman, K. L., Tremblin, P., Alves de Oliveira, C., et al. 2024, AJ, 167, 5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Madau, P., & Haardt, F. 2024, ApJ, 976, L24 [Google Scholar]

- Maio, U., & Viel, M. 2023, A&A, 672, A71 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Maio, U., Ciardi, B., Yoshida, N., Dolag, K., & Tornatore, L. 2009, A&A, 503, 25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Marley, M. S., Saumon, D., Visscher, C., et al. 2021, ApJ, 920, 85 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Matteri, A., Ferrara, A., & Pallottini, A. 2025, A&A, 701, A186 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Matthee, J., Naidu, R. P., Brammer, G., et al. 2024, ApJ, 963, 129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mauerhofer, V., Dayal, P., Haehnelt, M. G., et al. 2025, A&A, 696, A157 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Menci, N., Grazian, A., Castellano, M., et al. 2020, ApJ, 900, 108 [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, E., Pilo, S., Fontana, A., et al. 2019, A&A, 622, A169 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, E., Santini, P., Paris, D., et al. 2024, A&A, 691, A240 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, E., Fortuni, F., Calabró, A., et al. 2025, Open J. Astrophys., 8, E170 [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey, S. J., Burgasser, A. J., de Graaff, A., McConachie, I., & Brammer, G. 2025, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2511.01167] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, R. P., Oesch, P. A., van Dokkum, P., et al. 2022, ApJ, 940, L14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, R. P., Matthee, J., Katz, H., et al. 2025a, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2503.16596] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, R. P., Oesch, P. A., Brammer, G., et al. 2025b, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2505.11263] [Google Scholar]

- Nonino, M., Glazebrook, K., Burgasser, A. J., et al. 2023, ApJ, 942, L29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oesch, P. A., Brammer, G., van Dokkum, P. G., et al. 2016, ApJ, 819, 129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oke, J. B., & Gunn, J. E. 1983, ApJ, 266, 713 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz, D., Tinney, C. G., Faherty, J. K., et al. 2016, ApJ, 819, 17 [Google Scholar]

- Pacucci, F., & Loeb, A. 2022, AAS Meet. Abstr., 240, 213.04 [Google Scholar]

- Pacucci, F., & Narayan, R. 2025, AAS Meet. Abstr., 245, 123.06 [Google Scholar]

- Pacucci, F., Ferrara, A., & D’Onghia, E. 2013, ApJ, 778, L42 [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C. Y., Ho, L. C., Impey, C. D., & Rix, H.-W. 2002, AJ, 124, 266 [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, P. G., Barro, G., Annunziatella, M., et al. 2023, ApJ, 946, L16 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, P. G., Barro, G., Rieke, G. H., et al. 2024, ApJ, 968, 4 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, P. G., Östlin, G., Costantin, L., et al. 2025, ApJ, 991, 179 [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, M. W., Tremblin, P., Baraffe, I., et al. 2020, A&A, 637, A38 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Planck Collaboration VI. 2020, A&A, 641, A6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Polletta, M., Tajer, M., Maraschi, L., et al. 2007, ApJ, 663, 81 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevot, M. L., Lequeux, J., Maurice, E., Prevot, L., & Rocca-Volmerange, B. 1984, A&A, 132, 389 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Borsani, G., Treu, T., Shapley, A., et al. 2024, ApJ, 976, 193 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Robin, A. C., Reylé, C., Derrière, S., & Picaud, S. 2003, A&A, 409, 523 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rodighiero, G., Bisigello, L., Iani, E., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 518, L19 [Google Scholar]

- Santini, P., Menci, N., & Castellano, M. 2023, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2301.03892] [Google Scholar]

- Scalo, J. M., & Slavsky, D. B. 1980, ApJ, 239, L73 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schaerer, D., & de Barros, S. 2009, A&A, 502, 423 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sérsic, J. L. 1963, Boletin de la Asociacion Argentina de Astronomia La Plata Argentina, 6, 41 [Google Scholar]

- Skemer, A. J., Morley, C. V., Allers, K. N., et al. 2016, ApJ, 826, L17 [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, R. S., Yung, L. Y. A., Lancaster, L., et al. 2025, MNRAS, 544, 3774 [Google Scholar]

- Stalevski, M., Fritz, J., Baes, M., Nakos, T., & Popović, L. Č. 2012, MNRAS, 420, 2756 [Google Scholar]

- Stalevski, M., Ricci, C., Ueda, Y., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 458, 2288 [Google Scholar]

- Sun, G., Faucher-Giguère, C.-A., Hayward, C. C., & Shen, X. 2023, MNRAS, 526, 2665 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T. S., Akins, H. B., Harikane, Y., et al. 2025, ApJ, 995, 21 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. J., Kokorev, V., Kocevski, D. D., et al. 2025, ApJ, 989, L7 [Google Scholar]

- Trinca, A., Schneider, R., Valiante, R., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 529, 3563 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z., Wang, S., Chen, X., & Liu, J. 2025, ApJ, 980, 230 [Google Scholar]

- van Vledder, I., van der Vlugt, D., Holwerda, B. W., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 458, 425 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Vulcani, B., Trenti, M., Calvi, V., et al. 2017, ApJ, 836, 239 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B., Leja, J., de Graaff, A., et al. 2024, ApJ, 969, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel, A., de Graaff, A., Setton, D. J., et al. 2025, ApJ, 983, 11 [Google Scholar]

- Whitler, L., Stark, D. P., Topping, M. W., et al. 2025, ApJ, 992, 63 [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, S. M., Stanway, E. R., & Bremer, M. N. 2014, MNRAS, 439, 1038 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, S. M., Vijayan, A. P., Lovell, C. C., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 519, 3118 [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H., Sun, B., Ma, Z., & Ling, C. 2023, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2311.15121] [Google Scholar]

- Yung, L. Y. A., Somerville, R. S., Finkelstein, S. L., Wilkins, S. M., & Gardner, J. P. 2024a, MNRAS, 527, 5929 [Google Scholar]

- Yung, L. Y. A., Somerville, R. S., Nguyen, T., et al. 2024b, MNRAS, 530, 4868 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yung, L. Y. A., Somerville, R. S., & Iyer, K. G. 2025, MNRAS, 543, 3802 [Google Scholar]

- Zakhozhay, O. V., Zapatero Osorio, M. R., Béjar, V. J. S., & Boehler, Y. 2017, MNRAS, 464, 1108 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zakhozhay, O. V., Osorio, M. R. Z., Béjar, V. J. S., et al. 2023, A&A, 674, A66 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zapatero Osorio, M. R., Lodieu, N., Béjar, V. J. S., et al. 2016, A&A, 592, A80 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

Capotauro is the ancient name of the mountain now known as Corno alle Scale, located in the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines (Italy), continuing the naming convention used in Gandolfi et al. (2026).

Appendix A: Aperture photometry and flux estimations

Our analysis relies on the NIR photometry found in the ASTRODEEP-JWST catalog (described in detail in Merlin et al. 2024). In short, detection was performed with SEXtractor (v2.8.6; Bertin & Arnouts 1996) on a weighted stack of the F356W and F444W mosaics. Fluxes and uncertainties were estimated with aphot (Merlin et al. 2019), using colors measured in fixed circular apertures on PSF-matched images to scale the detection total Kron flux.