| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A148 | |

| Number of page(s) | 18 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202557167 | |

| Published online | 06 February 2026 | |

Intrinsic alignments of galaxies in multiple projections

1

Institute for Theoretical Physics, Utrecht University Princetonplein 5 3584 CC Utrecht, The Netherlands

2

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University P.O. Box 9513 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

9

September

2025

Accepted:

22

November

2025

The intrinsic alignments of galaxies can be measured and modelled to gain cosmological information and further improve our understanding of the interactions between galaxies, as well as to mitigate their effects on gravitational weak lensing studies. Hydrodynamical simulations are often used to constrain priors or calibrate models. Therefore, obtaining the maximum amount of information possible from these simulations is imperative. In this work, we combined the information of shapes projected over two or three axes (x, y, z), for intrinsic alignment signals (wg+,ξ∼g+,2), showing a consistent gain in signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) for all cases studied using TNG300-1. The gain in S/N is found to be higher for the addition of the second projection than for the third, and it is also higher for shapes calculated using the reduced inertia tensor, rather than the simple one. The two shape samples studied, n★ > 300 and log(M★ h/M⊙) > 10.5, where the latter has a much higher signal amplitude, show similar gains in S/N when more projections are added. We also modelled the correlation functions with the non-linear alignment model for scales greater than 6 Mpc/h. The S/N gains on the non-linear alignment amplitude, AIA, and galaxy bias, bg, are higher than those seen for the full measurements, indicating potential advantages for future works, particularly on larger scales with an increased uncertainty on the alignment signals. Using multiple projection axes increases the overall S/N, enabling a more efficient use of numerically expensive hydrodynamical simulations.

Key words: gravitational lensing: weak / cosmology: theory / large-scale structure of Universe

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

The deflection of light rays due to the presence of matter between a source and the observer, known as weak gravitational lensing, has been established as one of the most powerful probes for exploring the nature of dark matter and dark energy. It can be used to constrain the parameters of the current, widely used cosmological model (Albrecht et al. 2006; Kilbinger 2015). In the 2010s, large-area weak lensing surveys (Stage III surveys) such as the Dark Energy Survey1 (Abbott et al. 2018), Kilo-Degree Survey2 (de Jong et al. 2013), and Hyper Suprime-Cam3 (Aihara et al. 2018) were developed. In recent years, their results (Heymans et al. 2021; Secco et al. 2022; Dalal et al. 2023; Li et al. 2023; Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration 2023) have spurred a discussion of potential tensions in early- and late-time Universe cosmology (Abdalla et al. 2022), opening up new questions and paving the way for Stage IV surveys. Upcoming surveys include the Legacy Survey of Space and Time4 on the NSF-DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory (Ivezić et al. 2019), the Euclid mission5 (Laureijs et al. 2011), and the Nancy Roman Space Telescope6 (Spergel et al. 2015), which allow for precision cosmology to be applied.

The main advantage of weak lensing over other probes of cosmic structure is that it is directly sensitive to mass and, thus, less affected by astrophysical uncertainties (Weinberg et al. 2013). However, it is susceptible to a number of potential systematic sources of error, which pose challenges for the use of such surveys. One of these sources of systematic error is the intrinsic alignments (IA) of galaxies, a term used to refer to the correlations between galaxy shapes and orientations with each other and the underlying density field due to local processes, such as tidal fields (Troxel & Ishak 2015; Joachimi et al. 2015; Lamman et al. 2024). These localised correlations are similar to the effects of cosmic shear and contaminate weak gravitational lensing observations (Krause et al. 2015). Therefore, to fully exploit the potential of weak lensing as a tool for precision cosmology, these non-lensing alignments must either be removed or modelled precisely (Joachimi & Bridle 2010; Zhang 2010; Troxel & Ishak 2011). For reviews on intrinsic alignments, we refer to Troxel & Ishak (2015), Joachimi et al. (2015), Kirk et al. (2015), Kiessling et al. (2015) and, for a practical guide, we refer to Lamman et al. (2024).

Apart from their importance as a source of systematic bias in weak lensing studies, there is cosmological information that can be extracted from the IA signal, allowing it to be used to improve our comprehension of the formation and evolution of the large-scale structure of the Universe (e.g. Chisari & Dvorkin 2013; Chisari et al. 2014; Schmidt et al. 2015; Biagetti & Orlando 2020; Akitsu et al. 2023; Okumura & Taruya 2023; Kurita & Takada 2023; Xu et al. 2023). Galaxies of different types, colours and in different environments are also sensitive to intrinsic alignments in different ways, likely connected to their evolution through mergers and torques (e.g. Bate et al. 2020; Bhowmick et al. 2020) and to baryonic processes (e.g. Velliscig et al. 2015; Tenneti et al. 2017; Soussana et al. 2020). These relations and effects are often studied using hydrodynamical simulations such as IllustrisTNG (Nelson et al. 2021), EAGLE (Schaye et al. 2015), Horizon-AGN (Dubois et al. 2014), and MassiveBlack-II (Khandai et al. 2015).

The results and insights obtained from hydrodynamical simulations can be used to calibrate analytical models and constrain the priors or their parameters. Analytical methods include the linear alignment model (Hirata & Seljak 2004), extended to incorporate non-linear contributions (Hirata et al. 2007; Bridle & King 2007), which is valid on large scales. Additionally, the halo model relates the IA signal at small scales to the distribution of matter in dark matter halos (Schneider & Bridle 2010; Fortuna et al. 2020) and the EFT model describes the IA signal at intermediate scales (Vlah et al. 2020).

For the optimal mitigation of the effects of IA on weak lensing surveys, the parameters of the models need to be determined as precisely as possible. We need to extract as much information as we can from simulations. The obvious route would be to run larger simulations, increasing the sample sizes and, therefore, decreasing the noise in the measurements. However, this is very computationally expensive, making other avenues worth investigating. In recent years, the avenue of finding the optimal estimator has been explored in multiple works. Along this line, Singh et al. (2024) developed a new multipole-based estimator that increases the precision of parameter fits to IA models by a factor of ∼2. Recently, Lamman et al. (2025) suggested an alternative approach, where the line-of-sight integration limit (Πmax) is varied with the separation, rp. Similarly, Kumwembe et al. (2025) improved the S/N for multiplet alignments in DESI using imaging. In this work, we aim to find a complementary method to increase the amount of information that can be extracted from existing simulations, with a relative low computational cost and using the estimators already available. The main objective is to improve the S/N of intrinsic alignment correlations by considering a combination of the three possible projections over different axes of the simulation box. While previous works (e.g. Tenneti et al. 2020) have averaged over projections, the non-trivial cross-covariance between these projections has not been considered before, making the gain in S/N that can be obtained from combining multiple projections unknown. To gain an understanding of how this method complements different estimators, we considered two well-established estimators: wg+ and the quadrupole,  (Singh et al. 2024).

(Singh et al. 2024).

The rest of the work is structured as follows. In this study, we use one of the latest hydrodynamical simulations publicly available, the IllustrisTNG project, which will be described in more detail in Sect. 2, along with the sample selection. Section 3 discusses the methods adopted to calculate the shapes of galaxies and perform the two-point measurements, as well as the estimation of the covariance matrix through jackknife resampling and the calculation of the S/N values. Section 4 introduces the non-linear alignment model, used to fit the measurements. In Sect. 5, we present the results obtained from the applied methods. In Sect. 6, we discuss the results and outline potential avenues for future research and Sect. 7 summarises the conclusions drawn in this work.

2. Data

We used the IllustrisTNG hydrodynamic simulation. The particle and group data are described in the release papers by Springel et al. (2017) and Nelson et al. (2021).

2.1. IllustrisTNG

The IllustrisTNG cosmological simulations (hereafter TNG) are a series of large magnetohydrodynamical simulations of galaxy formation. These simulations are run using the moving-mesh code AREPO (Springel 2010). A Monte Carlo tracer particle scheme is utilised during the simulation to track the Lagrangian evolution of baryons (Genel et al. 2013). Each TNG simulation solves for the coupled evolution of dark matter, cosmic gas, luminous stars, and supermassive black holes from an initial redshift of z = 127 to z = 0.

The TNG simulations are based on a flat ΛCDM cosmological model, utilising parameters that are consistent with Planck Collaboration results, with a dark energy density of ΩΛ, 0 = 0.6911, total matter density of Ωm, 0 = 0.3089, baryon density of Ωb, 0 = 0.0486, amplitude of the matter power spectrum of σ8 = 0.8159, and ns = 0.9667.

These initial parameters determine the distribution of dark matter and gas at high redshift (z = 127) within a periodic simulation box of a given volume. The simulations then evolve these conditions forward in time, following the gravitational interactions between dark matter and gas, as well as the hydrodynamics of the gas, using the AREPO code (Nelson et al. 2021). As the simulation progresses, dark matter and gas collapse into dense regions where stars can form. The simulation outputs snapshots at various redshifts, with a total of 100 snapshots. At each snapshot, the friends-of-friends (FoF) and SUBFIND algorithm are used to identify subhalos and, ultimately, galaxies (Springel et al. 2001).

The TNG project is made up of three simulations in periodic boxes with side lengths of 35, 75, 205 cMpc/h apiece and at different resolutions. In this work, we focus on TNG300 at the highest resolution (TNG300-1), which has 25003 dark matter particles of a mass of mDM = 5.9 × 107 M⊙ and a box size of (205 cMpc/h)3. In particular, we examined the snapshot at redshift zero. In the simulation, we looked at two distinct mass cuts for the shape sample, described in Sect. 2.2.

2.2. Sample Selection

To measure the cross-correlation between the galaxy positions and their shapes, we defined two galaxy shape samples and one galaxy position sample. In this study, the raw data come from the snapshot data catalogues of TNG300-1 at z = 0, sourced from publicly available data7. It is then processed using the equations and methods described in Sect. 3.

While simulated data are not subject to the same biases as observed data, such as the challenge of fitting ellipticities in the presence of pixel noise or imperfect PSF modelling (Samuroff et al. 2021), they remain susceptible to bias. This prompts us to implement quality cuts to ensure the validity of the conclusions that have been drawn. A primary source of uncertainty arises from galaxy resolution, which impacts the ellipticity and orientation measurements. Galaxies with an insufficient number of particles to provide a meaningful shape measurement affect the ellipticity distribution of the sample. Through a series of convergence tests, Chisari et al. (2015) found that a minimum number of 300 particles per galaxy would be needed to mitigate resolution bias to acceptable levels. Consequently, in this study, we followed this practice and applied a cut to the shape sample, selecting only galaxies with more than 300 particles.

For the position sample, we enforce a quality cut of n★ > 50. This threshold reflects the minimum number of particles required for a bound substructure to be considered a legitimate galaxy by the SUBFIND algorithm used in the IllustrisTNG simulations (Nelson et al. 2021). Galaxies with fewer than 50 particles are not well-resolved and could be considered random fluctuations. These cuts leave a total of 192 109 galaxies in the shape sample and 371 855 in the position sample.

In addition to this quality cut, we also consider another shape sample defined by the galaxy stellar mass, M★, enabling us to investigate whether the possible gain in S/N depends on the signal strength, as high mass galaxies have a stronger alignment signal. The high-mass shape sample is defined by M★ > 1010.5 M⊙/h, and contains 24 430 galaxies. The choice in terms of the position sample remains the same.

3. Methodology

3.1. Galaxy shapes

To characterise the three-dimensional (3D) shape of a galaxy, we use both the simple and reduced inertia tensor. While the simple inertia tensor generally provides a higher IA correlation function signal amplitude, allowing for more insight in the workings of galaxies, the reduced inertia tensor shape gives more weight to particles closer to the centre. This leads to rounder estimates of galaxy shapes, which mimic the observations more closely and are, therefore, also worth studying (Tenneti et al. 2015). The simple (Eq. (1)) and reduced (Eq. (2)) tensors are given by

where k, l run from 0 to 2 and denote the x, y, z components of a vector, r, and i runs over all Nj particles in galaxy, j. The vector, r, refers to the position of each particle (xi) relative to the centre of mass (xj), given by ri = xi − xj. The centre of mass is measured via the mass weighted mean of the particle positions in a galaxy  . The variables Mj and mi refer to the galaxy and particle masses, respectively.

. The variables Mj and mi refer to the galaxy and particle masses, respectively.

To determine the two-dimensional (2D) projected shapes of the galaxies, the positions of the particles are projected onto a plane, which can be given by either side of the simulation box. In most other studies, the xy plane is chosen arbitrarily, and thus Eq. (1) is projected along the z-axis by using only the k, l = 0, 1 elements, corresponding to x, y. For Eq. (2), r2 is equal to rx2 + ry2, and so becomes the projected distance from the particle to the centre of mass.

In this work, we calculated three different 2D projected shapes by projecting onto the xy, xz, and yz planes, hereafter called the z, y and x projections, respectively, referring to the line-of-sight axis. The three projected inertia tensors can be diagonalised to yield the eigenvalues, λa > λb, which correspond to the squared values of the lengths of the semi-major and semi-minor axes of the projected ellipsoid and the corresponding eigenvectors,  and

and  , denote their orientation. We define the axis ratio of the galaxy as q = b/a, where a and b represent the semi-major and semi-minor axis lengths (

, denote their orientation. We define the axis ratio of the galaxy as q = b/a, where a and b represent the semi-major and semi-minor axis lengths ( ,

,  ).

).

The radial and tangential ellipticity components of the shape galaxy relative to the position galaxy is then defined by Eq. (3). The components of the ellipticity are given by Mandelbaum et al. (2006):

where q is the axis ratio and ϕ is the orientation angle of the semi-major axis (i.e. the angle between the semi-major axis of the galaxy and the separation vector between a given position and shape galaxy pair). For this definition, e+ > 0 indicates radial alignment, e+ < 0 tangential alignment and e× is the cross component, which generally averages to zero in the universe. The total ellipticity of a galaxy is then calculated as  . We note that we have chosen the convention of using the distortion as the ellipticity,

. We note that we have chosen the convention of using the distortion as the ellipticity,  , instead of the other commonly used definition

, instead of the other commonly used definition  . As we are using e to denote this quantity, we use the term ellipticity throughout the paper.

. As we are using e to denote this quantity, we use the term ellipticity throughout the paper.

3.2. Projected correlations

We focussed our analysis on the cross-correlation of galaxy positions and intrinsic ellipticities, ξg+. To estimate ξg+, we adopted a commonly used estimator, the Landy-Szalay (LS) estimator (Landy & Szalay 1993). This estimator was originally devised to estimate galaxy clustering (ξgg), but it can be generalised to calculate other correlation functions, including ξg+ (Mandelbaum et al. 2006). Alternative estimators, such as the one used in Joachimi et al. (2011), can also be employed. However, the LS estimator has several advantages, including having a higher signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) compared to other estimators (Singh et al. 2015).

We defined the cross-correlation of galaxy positions and intrinsic ellipticities, ξg+(rp, Π), as a function of the projected separation, rp, and along the line of sight, Π (Mandelbaum et al. 2011):

where S+ refers to the + component of our galaxy shape sample and D is the position sample. Additionally, we define R as a set of randomly distributed galaxies with no correlations from large-scale clustering. Here, S+D refers to the sum over all position-shape pairs of simulated galaxies and is given by

where i, j refer to galaxies in the shape or position sample, respectively. In this equation, ℛ refers to the responsivity factor. This variable is a measure of the response of the ellipticity to a small shear and is given by ℛ = 1 − ⟨e2⟩/2, where ⟨e2⟩ is the mean squared ellipticity of the galaxy sample (Bernstein & Jarvis 2002). S+RD refers to the sum over the ellipticities of the galaxies around the random points, which we assumed to be zero, following Tenneti et al. (2015). The quantities RS and RD represent randomly distributed points in the shape sample and density sample, respectively. The denominator, RSRD, corresponds to the expected number of pairs of random galaxies with separation and rp and Π for a uniform random distribution. This quantity is calculated analytically following the approach outlined by Singh et al. (2024).

From these 3D measurements, we can straightforwardly obtain the 2D projected correlation, wg+, which is one of the primary targets of this study. While the 3D information of galaxy shapes can provide more insight, comparing such data with observations is challenging as all galaxy shapes are projected on the sky and we have a fixed line of sight determined by our position in space. Projected correlation functions are more straightforward to observe and model, which makes it more useful to facilitate a direct comparison between simulation results and observational data.

The projected correlation function between galaxy positions and shapes, wg+, is given by integrating along the line of sight,

where Πmax is an integration limit, which can be set by the simulation volume, or chosen separately. In this work, we take Πmax = 20 Mpc/h, to reduce the noise. The impact of using half the box size (102.5 Mpc/h) as Πmax on the results is discussed in Appendix A. The measurements are performed in 15 radial bins from 0.1 Mpc/h ≤ rp ≤ 40 Mpc/h; determined by the number of jackknife regions (see Sect. 3.4) and the box size, which limits the largest scales we can probe without running out of galaxy pairs. Thus, we obtained three different projected cross-correlation functions, wg+x, wg+y, and wg+z, by projecting along the three axes of the simulation box.

3.3. Multipoles

We also measure the multipole expansion of the correlation function, which has emerged as a new and improved estimator for the intrinsic alignment of galaxies. Singh & Mandelbaum (2016) highlighted the potential of using multipole expansion due to the well-defined scaling of the IA signal in the (rp, Π) plane. In such instances, the correlation function can be expressed in terms of their multipole moments according to the following expression (Singh et al. 2024; Okumura & Taruya 2023):

Here, μr is the cosine of the angle between line-of-sight direction and the separation vector r. Lℓ, sab refers to the ℓ-th order associated Legendre polynomial, while sab represents the spin parameter. Note that (Singh et al. 2024) use a wedged multipole, setting the integrand in Eq. (7) to zero for rp < 2 Mpc/h. We find that for r > rp the wedged multipole quickly converges to the full expression, leading to virtually no difference in our results since we restrict the modelling analysis to scales r > 6 Mpc/h.

In this study, similarly to the case of projected correlations, we focus on the cross-correlation between galaxy positions and shapes,  . Galaxy shapes are considered spin-two objects due to their symmetry under rotation by 180 degrees, which implies that sab = 2 for

. Galaxy shapes are considered spin-two objects due to their symmetry under rotation by 180 degrees, which implies that sab = 2 for  (Singh et al. 2024). Because of symmetry, the quadrupole moment is the lowest non-zero multipole moment, which leads to ℓ = 2. Therefore, the expression used to calculate the cross-correlation function in terms of the multipole moments is given by

(Singh et al. 2024). Because of symmetry, the quadrupole moment is the lowest non-zero multipole moment, which leads to ℓ = 2. Therefore, the expression used to calculate the cross-correlation function in terms of the multipole moments is given by  , hereafter abbreviated to

, hereafter abbreviated to  ,

,

This approach is a relatively new avenue for estimating intrinsic alignments. Kurita & Takada (2023) measured the 3D IA power spectrum from the spectroscopic BOSS galaxy sample for the first time by decomposing the spin-2 IA field into multipole moments. They showed that this approach leads to higher S/N and tighter constraints. Recent work by Singh et al. (2024) has also demonstrated the potential of this approach, showing that using a multipole-based estimator can lead to a ∼2.3 increase in statistical precision of alignment amplitude. This improvement is equivalent to having a survey area that is four times larger. Motivated by these promising findings, this work aims to investigate the improvement in the IA signal when employing the multipole-based estimator (hereafter referred to as quadrupole) in the context of hydrodynamic simulations. Similar to the case of wg+, we calculate three different projections of the quadrupole,  ,

,  , and

, and  , by projecting along the three axes of the simulation box.

, by projecting along the three axes of the simulation box.

For the measurements of both wg+ and  the code MEASUREIA8 was used. MEASUREIA is publicly available and has been validated against HALOTOOLS9 (Hearin et al. 2017) and TREECORR10 (Jarvis et al. 2004) for wg+ and wgg measurements, including the covariance.

the code MEASUREIA8 was used. MEASUREIA is publicly available and has been validated against HALOTOOLS9 (Hearin et al. 2017) and TREECORR10 (Jarvis et al. 2004) for wg+ and wgg measurements, including the covariance.

3.4. Covariance matrices

The covariance matrices for our measurements are estimated using the jackknife method (Quenouille 1956; Tukey 1958; Shao 1986). We divide the simulation box into Nsub cubes of equal volumes and compute the alignment statistics by omitting one of the Nsub sub-volumes at a time. This process leads to Nsub jackknife measurements. The covariance matrix for N jackknife resamplings is then estimated using the following expression (Norberg et al. 2009):

where ψi is the value of ψ for the i-th r or rp bin of a given statistic of interest,  , for the k-th jackknife resampling. The mean value of the i-th measurement over all jackknife resamplings,

, for the k-th jackknife resampling. The mean value of the i-th measurement over all jackknife resamplings,  , is given by

, is given by

According to Hirata & Seljak (2004, Appendix D), Nsub needs to be larger than Nbin3/2, with Nbin the number of rp bins, and the length of their box needs to be larger than the largest scales measured. Therefore, for this work, Nsub = 53 = 125 sub-volumes are used, and the effect of using Nsub = 64 is explored in Appendix B.

It is important to note that the jackknife error estimation is limited by the size of the simulation box. As found by Norberg et al. (2009), even though the jackknife covariance estimator is accurate on large scales, it tends to overestimate the covariances on small scales. While this effect depends on the size of the Nsub sub-volumes the data is split into, it is possible that the error bars will be overestimated, especially on smaller scales. Unfortunately other estimators also present limitations, and addressing these effects is beyond the scope of this work. However, the validity of our assumptions has been tested on TNG100-1, which has a smaller box size and higher resolution than TNG300-1. The results of these tests can be found in Appendix C.

We can rewrite Eq. (10) to include the three different projections of our alignment statistics. The data vector, ψ, is redefined as a concatenation of the three possible projections,

and we define the new covariance matrix,  , as

, as

where a, b ∈ (x, y, z), with nine possible combinations of a and b. Thus, the full covariance matrix of all three projections combined,  , is a block matrix, with block elements,

, is a block matrix, with block elements,  can be represented as

can be represented as

This covariance matrix, which incorporates the covariances between different projections, will be referred to as the ‘combined covariance matrix’ in subsequent sections. The dimensions of this combined covariance matrix are 3Nbins × 3Nbins, where each block  is an Nbins × Nbins matrix. In this work, since Nbins = 15, the combined covariance matrix has dimensions of 45 × 45, accounting for the 15 radial bins in each of the three projections (x, y and z). When considering the combinations of two projections alone, the relevant four

is an Nbins × Nbins matrix. In this work, since Nbins = 15, the combined covariance matrix has dimensions of 45 × 45, accounting for the 15 radial bins in each of the three projections (x, y and z). When considering the combinations of two projections alone, the relevant four  blocks can be combined to form the 30 × 30 covariance matrix.

blocks can be combined to form the 30 × 30 covariance matrix.

3.5. Signal-to-noise ratio

The S/N is generally calculated using the following expression,

where ψ represents the wg+ or  data vector, and

data vector, and  is the inverse of the covariance matrix. However, when using the jackknife method to estimate the covariance matrix, only a limited resolution of

is the inverse of the covariance matrix. However, when using the jackknife method to estimate the covariance matrix, only a limited resolution of

can be attained, with Nsub the number of jackknife regions, as explained by Gaztañaga & Scoccimarro (2005). Following the procedure from Eisenstein & Zaldarriaga (2001), Gaztañaga & Scoccimarro (2005), we therefore introduce a resolution condition, imposed on the covariance, which becomes more influential when the projections are combined. The S/N can then be calculated as follows. First, the data and the covariance need to be normalised according to

where  is the variance. After the normalisation, we perform a Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) of the covariance matrix,

is the variance. After the normalisation, we perform a Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) of the covariance matrix,

where Dkl is, per definition, a diagonal matrix with elements λi2. Note that other literature commonly refers to V as hermitian instead of U. In the case of a positive-definite symmetric matrix, such as a covariance, this is irrelevant because U = V. The uncertainty on ΔCij can be translated into a condition on the D eigenvalues, given by

which we motivate more in-depth in Appendix D. We conduct the rest of the analysis in the basis where the covariance is diagonalised. Therefore, the new data vector elements become

When using the inverse of an estimated covariance, as we need for the S/N (Eq. (15)), we apply the Hartlap factor to correct for the bias introduced by the inversion (Hartlap et al. 2006). This factor is given by

where p is the number of elements in the data vector. It is only valid when p < Nsub − 2, which is true in our case. As we are effectively reducing the number of elements in the data vector by imposing the resolution condition, we are using the number of elements left after the condition is included as our p, which is consistent with the work of Philcox et al. (2021). As the data vector length changes with a factor of 2 or 3, depending on the number of projections combined, but Nsub remains the same, the Hartlap factor will be different according to the number of projections.

To calculate the S/N, we use only the elements i of the new data vector for which Eq. (19) is satisfied (p), summing over the squared values of the (S/N)i, which is the S/N for each individual element. The total S/N then becomes

In Sect. 5.3, this version of the S/N is used to compare between cuts, using one or more projections.

4. Modelling

We fit the correlation functions using the linear alignment (LA) model (Catelan et al. 2001). This model is based on the premise that there exists a linear relation between the intrinsic shapes, or ellipticities, of galaxies and the tidal field at the time of galaxy formation. Such linear relation, as expressed by Singh et al. (2015), is:

where ϕp is the primordial gravitational potential, C1 is a constant that determines the strength of the alignment, and G is Newton’s gravitational constant.

Starting from this equation, Hirata & Seljak (2004) derived the power spectrum for the two-point position-shape correlation functions, linking them to the linear matter power spectrum, Pδlin. Focussing only on the cross-correlation, the cross-power spectrum between the galaxy density field and the galaxy intrinsic shear along the line connecting a pair of galaxies is given by Singh et al. (2015):

Here, bg represents the linear galaxy bias, which relates the galaxy density field to the underlying matter density field. In line with other studies, we assume that bg is scale-independent (Joachimi et al. 2011; Chisari & Dvorkin 2013). D(z) is the growth function, normalised to unity at z = 0, to account for the fact that the LA model assumes alignments are established at the time of galaxy formation. Following the conventions of Joachimi et al. (2011), we set C1ρcrit = 0.0134. As defined by Singh et al. (2015), we use a free constant AIA to measure the amplitude of IA. In practice, we use Eq. (3.4) from Blazek et al. (2011) and Eq. (9) from Singh et al. (2024) to calculate wg+ and ξg+2, 2 predictions, respectively, without a Limber approximation.

While the LA model is reasonable at large scales, its reliability diminishes on small scales. For this reason, Bridle & King (2007) propose, following Hirata & Seljak (2004), to replace Pδlin with the non-linear power spectrum Pδnl, resulting in what is known as the non-linear alignment (NLA) model. This provides a more realistic modelling of intrinsic alignments on small scales, where non-linear effects become significant. In this work, we use the NLA model to calculate the predicted values for wg+ and  . The non-linear matter power spectrum will be calculated through the Core Cosmology Library (CCL)11 (Chisari et al. 2019), which uses the software CAMB code to calculate the values (Lewis & Bridle 2002).

. The non-linear matter power spectrum will be calculated through the Core Cosmology Library (CCL)11 (Chisari et al. 2019), which uses the software CAMB code to calculate the values (Lewis & Bridle 2002).

In our analysis, we fit for a single parameter in the NLA model, which is the product of the galaxy bias, bg and the IA amplitude, AIA, henceforth designated as NLA amplitude. For each dataset, we perform the fitting procedure in two different ways. First, we fit each of the three individual projections (x, y and z) separately, using the corresponding individual covariance matrix. The resulting best-fit parameter from this approach is referred to as bgAIA(1). Secondly, we fit a combination of all three projections simultaneously, where the obtained best-fit parameter is denoted as bgAIA(3).

The best-fit parameter for bgAIA(1) and bgAIA(3), along with their uncertainties, were determined by minimising the chi-squared statistic. Similar to the S/N considerations from Sect. (5.3), we transformed data and model vector according to Eq. (20) and apply the resolution condition Eq. (19). The transformed chi-squared then becomes

where λi are the Eigenvalues of the decomposed covariance matrix Cij. In the case of the individual fitting, Cij refers to the corresponding individual covariance matrix, while for the combined fit of three projections, Cij refers to the combined covariance matrix, as described in Eq. (13).

The NLA model is known to break down and underestimate the alignment signal on small scales. To mitigate this, we follow the approach adopted by many studies and restrict the fitting range for the NLA model to intermediate and larger scale (see Singh et al. 2024, Tenneti et al. 2015, among others). We fit the model only over the region between 6 Mpc/h < rp < 40 Mpc/h.

5. Results

5.1. Projected alignment estimators

We begin by presenting the projected density-shape correlation function in Fig. 1, wg+ (top panel), and the quadrupole,  (bottom panel) for three different projections along the x (light blue), y (medium blue) and z (dark blue) axes. In this figure, wg+ is multiplied by rp and

(bottom panel) for three different projections along the x (light blue), y (medium blue) and z (dark blue) axes. In this figure, wg+ is multiplied by rp and  by r2 to negate the main r(p)-dependence, making the comparison between different cuts and projections more clearly visible. The error bars have been calculated using the jackknife resampling technique described in Sect. 3.4. Both statistics are shown for two different shape samples, measured using the simple inertia tensor: galaxies with more than 300 stellar particles (n★ > 300, continuous lines) and galaxies with log(M★[M⊙/h]) > 10.5 (dashed lines).

by r2 to negate the main r(p)-dependence, making the comparison between different cuts and projections more clearly visible. The error bars have been calculated using the jackknife resampling technique described in Sect. 3.4. Both statistics are shown for two different shape samples, measured using the simple inertia tensor: galaxies with more than 300 stellar particles (n★ > 300, continuous lines) and galaxies with log(M★[M⊙/h]) > 10.5 (dashed lines).

|

Fig. 1. Correlation functions, rpwg+ (top) and |

Figure 1 shows that the three different projections along the x, y and z axes are consistent with each other, although at large scales (r(p) ≳ 8 Mpc/h) the data points become noisy due to lack of galaxy pairs and sometimes only the error bars overlap, indicating the errors may be underestimated. The agreement between the signals confirms the expected behaviour that there should be no significant difference between the various line-of-sight projections and that the common choice of projecting onto the xy plane is arbitrary. Furthermore, it can be observed that within the same simulation, the error bars on the quadrupoles are smaller compared to those on wg+, and even though the signal amplitude is lower too, the mean S/N is higher as can be seen in Sect. 5.3. This highlights the benefits of using the quadrupole as potential alternative estimators for the density-shape correlation, as suggested by Singh et al. (2024).

Our choice of Πmax = 20 Mpc/h for wg+ means that the shapes of the correlation functions are very similar between wg+ and the quadrupole up to separations of 20 Mpc/h (provided we take out the main r(p)-dependence). Choosing a larger value for Πmax, adds more noise at large scales to wg+, as can be seen in Fig. A.1.

Comparing the mass cuts, we observe that the high mass sample indeed produces a much larger signal amplitude for both wg+ and  . We also see that the error bars for the high mass cut are larger, due to the smaller sample size. As shown in Sect. 5.3, this stronger signal does not lead to a higher S/N, because both the signal and noise increase by a similar factor.

. We also see that the error bars for the high mass cut are larger, due to the smaller sample size. As shown in Sect. 5.3, this stronger signal does not lead to a higher S/N, because both the signal and noise increase by a similar factor.

These signals have also been measured for shapes measured by the reduced inertia tensor. As this produces rounder shapes, the amplitudes of those signals are much lower. However, the comparison between the different cuts and projections is very similar to Fig. 1. Furthermore, IA correlation functions have been measured in TNG100 for both mass cuts and shape types. Therein, the correlations are much noisier due to the smaller box size, which also leads to a decreased signal strength. Barring that, the signals show the same main conclusions as for TNG300. The S/N values for TNG100 are shown in Appendix C.

5.2. Combined covariance matrix

Figure 2 illustrates the normalised combined covariance matrix, as defined in Eq. (13) and normalised by Eq. (17), for the shape sample defined by n★ > 300 for wg+ (top panel) and  (bottom panel).

(bottom panel).

|

Fig. 2. Normalised combined covariance matrices for wg+ (top panel) and |

For both wg+ and the quadrupole, the combined covariance matrix exhibits the expected symmetry along the diagonal of the auto-correlation blocks (e.g. Cxx). Comparing the wg+ and the quadrupole covariance matrices, we see notable differences between the two. The quadrupole (bottom panel) shows a similar structure in all the auto-correlation and cross-correlation blocks: a high value diagonal; low values for cross-terms with small scales; high values for intermediate scales, r ≳ 0.5 Mpc/h, that gradually decrease as the scales increase. This basic structure is visible in every block, where naturally the central diagonal (auto-correlation blocks) is highest, as it is set to 1 by definition. For wg+ (top panel), we see a less coherent structure arise. The cross-correlation (off-diagonal) blocks do not show a clear diagonal and while the ‘middle’ scales have higher values than the cross terms with small or large scales, the normalised values are lower than for the quadrupole; the median value of the ratio between wg+ and  of all elements (

of all elements ( ) is ∼0.84. Therefore, it seems that the signals of different projections are less correlated for wg+ than for the quadrupole.

) is ∼0.84. Therefore, it seems that the signals of different projections are less correlated for wg+ than for the quadrupole.

In Appendix B, where the effects of using 64 jackknife regions (instead of 125) are explored, we see that the normalised values of the covariance matrix are generally lower than in Fig. 2. This indicates either that choosing 125 jackknife regions overestimates the covariance, or that choosing 64 jackknife regions underestimates the covariance. We have opted for 125 jackknife regions in this work because these covariance matrices are more stable (see Appendix B). Furthermore, Appendix E explores the effect of averaging the diagonal and off-diagonal covariance blocks, which should be equal, given that there is no preferred line-of-sight direction in a large enough box. This reduces the noise of the covariance estimate, but erases the influence of the variation in the large scale structure that arises due to the limited box size.

5.3. Signal-to-noise ratio comparison

We compare the S/Ns of using one or more projections, defined in Sect. 3.5. A higher S/N indicates a more robust detection of the intrinsic alignment signal against the background noise.

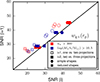

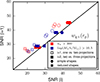

We calculate the S/N for three cases: once for each individual projection {x, y, z}, S/N (1); three times for a combination of two projections, S/N (2) {(x, y),(y, z),(x, z)}; and once using the combined covariance matrix and concatenated data vector from all three projections, S/N (3). If the signals from the different projections {x, y, z} are completely uncorrelated, the maximum improvement in S/N that we can expect by combining the three projections is a factor of  compared to using any individual projection alone, or

compared to using any individual projection alone, or  for two projections. The results are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1.

for two projections. The results are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1.

|

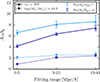

Fig. 3. S/Ns for the wg+ (top) and |

Figure 3 shows the improvement in S/N when one extra projection is added for wg+ (top panel) and  (bottom panel). In other words, the unfilled markers show the S/N for one projection on the horizontal axis versus two projections on the vertical axis, whereas the filled markers show two versus three projections, respectively. The colours denote the shape sample that is used: red for n★ > 300 and blue for log(M★h/M⊙) > 10.5. Furthermore, the circles represent the measurement of the shapes using the simple inertia tensor (Eq. (1)) and the crosses, the reduced inertia tensor (Eq. (2)). The black line is plotted at S/N(i) = S/N(i + 1). Therefore, an improvement in S/N is shown by the marker residing in the top left half of the plot. For the one versus two projection markers (unfilled), the combinations {x, (x, y)}, {y, (y, z)} and {z, (x, z)} are shown.

(bottom panel). In other words, the unfilled markers show the S/N for one projection on the horizontal axis versus two projections on the vertical axis, whereas the filled markers show two versus three projections, respectively. The colours denote the shape sample that is used: red for n★ > 300 and blue for log(M★h/M⊙) > 10.5. Furthermore, the circles represent the measurement of the shapes using the simple inertia tensor (Eq. (1)) and the crosses, the reduced inertia tensor (Eq. (2)). The black line is plotted at S/N(i) = S/N(i + 1). Therefore, an improvement in S/N is shown by the marker residing in the top left half of the plot. For the one versus two projection markers (unfilled), the combinations {x, (x, y)}, {y, (y, z)} and {z, (x, z)} are shown.

For both wg+ and  , almost all cases show a clear improvement in S/N when the information of an extra projection is added. For clarity, Table 1 has been added, which shows the gain in S/N, averaged over the three combinations that are shown individually in Fig. 3 for each choice in shape sample, statistic and shape type. Together, Fig. 3 and Table 1 reveal that for all our cuts and shape types, we can expect a gain in S/N when combining two or three projections, where adding the third projection to two projections will result in less gain than adding a second projection to one projection (the filled markers are closer to the line than the unfilled ones in Fig. 3). The gain in S/N and the S/N values themselves are similar for both mass cuts, despite the high mass sample having a much higher signal amplitude. Furthermore, the gain in S/N for the reduced shapes is generally higher than the gain in S/N for the simple shapes. Finally, the gain in S/N is higher for wg+ than for the quadrupole, although the quadrupole still has a larger S/N in all cases.

, almost all cases show a clear improvement in S/N when the information of an extra projection is added. For clarity, Table 1 has been added, which shows the gain in S/N, averaged over the three combinations that are shown individually in Fig. 3 for each choice in shape sample, statistic and shape type. Together, Fig. 3 and Table 1 reveal that for all our cuts and shape types, we can expect a gain in S/N when combining two or three projections, where adding the third projection to two projections will result in less gain than adding a second projection to one projection (the filled markers are closer to the line than the unfilled ones in Fig. 3). The gain in S/N and the S/N values themselves are similar for both mass cuts, despite the high mass sample having a much higher signal amplitude. Furthermore, the gain in S/N for the reduced shapes is generally higher than the gain in S/N for the simple shapes. Finally, the gain in S/N is higher for wg+ than for the quadrupole, although the quadrupole still has a larger S/N in all cases.

S/N gain.

One possible reason for these differences in gain is the influence of the covariance resolution criterion in the S/N calculation as described in Sect. 3.5. The number of terms included in the S/N is always higher for wg+ than for  and higher for reduced shapes than for simple shapes. As each term included into the S/N increases the S/N, more terms added will increase the chances in S/N gain when projections are combined.

and higher for reduced shapes than for simple shapes. As each term included into the S/N increases the S/N, more terms added will increase the chances in S/N gain when projections are combined.

5.4. Model and fit

In this section we present the results of fitting the NLA model to wg+ and  . First, we assess the quality of the fit and then investigate the improvement of S/N when combining projections, analogous to Sect. 5.3. However, in this section we restrict the scales to r(p) > 6 Mpc/h, only investigating the S/N obtained with common NLA modelling choices. Therefore, the results shown here serve two purposes, first, to investigate how different scales contribute to the gain in S/N, and second, to examine how the pure gain in S/N propagates into uncertainty of the inferred NLA amplitude.

. First, we assess the quality of the fit and then investigate the improvement of S/N when combining projections, analogous to Sect. 5.3. However, in this section we restrict the scales to r(p) > 6 Mpc/h, only investigating the S/N obtained with common NLA modelling choices. Therefore, the results shown here serve two purposes, first, to investigate how different scales contribute to the gain in S/N, and second, to examine how the pure gain in S/N propagates into uncertainty of the inferred NLA amplitude.

Figure 4 shows the combined fit along the x-, y- and z-axis (light, medium and dark blue) for wg+ (top panel) and  (bottom panel) galaxy-shape correlation functions, both for particle number (downward triangle) and mass cut (upward triangle) using the simple inertia tensor definition. The NLA model is fitted in the unshaded region and displayed as solid line for the particle number cut and dashed line for the mass cut. It must be noted that the individual points in Fig. 4 are highly correlated, not only between different projection directions, but also between r(p) bins due to mode mixing. However, we can judge the goodness of fit with the reduced χred2 shown in Table 2. It ranges from 0.47 to 1.59 and is generally lower for wg+, possibly indicating slightly over-predicted error bars, but nevertheless an acceptable fit.

(bottom panel) galaxy-shape correlation functions, both for particle number (downward triangle) and mass cut (upward triangle) using the simple inertia tensor definition. The NLA model is fitted in the unshaded region and displayed as solid line for the particle number cut and dashed line for the mass cut. It must be noted that the individual points in Fig. 4 are highly correlated, not only between different projection directions, but also between r(p) bins due to mode mixing. However, we can judge the goodness of fit with the reduced χred2 shown in Table 2. It ranges from 0.47 to 1.59 and is generally lower for wg+, possibly indicating slightly over-predicted error bars, but nevertheless an acceptable fit.

|

Fig. 4. Correlation functions, rpwg+ (top) and |

Fitted amplitude.

The fitted amplitudes for all available measurements are displayed in Table 2 as well. We find a consistent ∼25% difference in inferred AIAbg between wg+ and  . We believe that this is caused by both methods probing different scales and further discuss this in Appendix F. Still, the inferred AIAbg are internally consistent for the individual projection directions, enabling us to investigate the gain in S/N in a similar way to what is described in the previous sections. In this case, we can define the S/N as the fraction between fitted amplitude (AIAbg) and associated error (σ(AIAbg)) obtained by minimising the χ2-statistic defined in Eq. (25):

. We believe that this is caused by both methods probing different scales and further discuss this in Appendix F. Still, the inferred AIAbg are internally consistent for the individual projection directions, enabling us to investigate the gain in S/N in a similar way to what is described in the previous sections. In this case, we can define the S/N as the fraction between fitted amplitude (AIAbg) and associated error (σ(AIAbg)) obtained by minimising the χ2-statistic defined in Eq. (25):

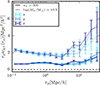

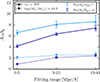

The increase in S/N by adding additional projections is shown in Fig. 5. We show improvement in S/N(AAIbg) as a function of added projections for particle number cut (mass cut) in red (blue), both for simple and reduced inertia tensor shapes (points and crosses, respectively). Unfilled markers indicate the improvement when going from one to two projections, and filled markers when going from two to three projections. Again, the points above the one-to-one line indicate a gain in S/N when adding additional projections. As before, increasing the number of projections used increases the S/N. The improvement is further quantified in Table 3 where we average over the gain when adding an additional projection. Note that with the definition from Eq. (26), it is no longer necessarily true that the increase in S/N is bounded by the factors  or

or  when adding one or two projections, respectively. We discuss this further below.

when adding one or two projections, respectively. We discuss this further below.

|

Fig. 5. Same as Fig. 3, but for the S/N defined in Eq. (26) obtained from the non-linear alignment model fit. |

S/N gain from fit.

Similarly to Sect. 5.3, the S/N increases in almost all cases when adding more projections, whereas the gain is larger when adding a second projection than a third. A notable exceptions is wg+ for reduced shapes using the particle number cut, where the S/N decreases slightly on average when adding a third projection. We believe this to be cause by the resolution condition (Eq. (19)): The error on the correlation function is larger for the higher rp we consider in this chapter. Therefore, adding highly correlated points means proportionally also adding more noise that can lead to removing more values after the SVD; see also Appendix C. This problem is unique to noisy covariance matrix estimators that might not have full rank and require the aforementioned treatment.

When considering the full data vector in Sect. 5.3, wg+ benefits more on average than  when adding additional projections. Here, the reverse seems to be the case. A possible reason for the difference is the additional coupling of the goodness of fit into the S/N consideration. Mathematically, the only difference between the χ2 and the actual S/N is the input model (see Eqs. (22) and (25). Since the covariance of the fit parameter is closely related to the Hessian of χ2, (Cramér 1946; Rao 1945), we expect that improvements in the goodness-of-fit will propagate into the actual S/N(AAIbg). This might further explain why the gain slightly exceeds the theoretical threshold of

when adding additional projections. Here, the reverse seems to be the case. A possible reason for the difference is the additional coupling of the goodness of fit into the S/N consideration. Mathematically, the only difference between the χ2 and the actual S/N is the input model (see Eqs. (22) and (25). Since the covariance of the fit parameter is closely related to the Hessian of χ2, (Cramér 1946; Rao 1945), we expect that improvements in the goodness-of-fit will propagate into the actual S/N(AAIbg). This might further explain why the gain slightly exceeds the theoretical threshold of  for the reduced-shape

for the reduced-shape  measurements in the high mass cut case, in particular with a noisy jackknife covariance matrix that is limited by the box size. The question arises whether this behaviour remains with a more robust covariance that is obtained by analytical means. However, this question is outside the scope of this work and can be tackled in future projects.

measurements in the high mass cut case, in particular with a noisy jackknife covariance matrix that is limited by the box size. The question arises whether this behaviour remains with a more robust covariance that is obtained by analytical means. However, this question is outside the scope of this work and can be tackled in future projects.

Even though the fitted NLA amplitudes are affected by a limited scale range and box size, the S/N shows improvement when combining information of multiple projections in the simulation box. The improvement decreasing when going from two to three projections versus from one to two is further in agreement with the results presented in Sect. 5.3. This again solidifies the advantages of this method for obtaining the maximum amount of available information for computationally expensive and extensive hydrodynamical cosmological simulations.

6. Discussion

In this work, we have studied the intrinsic alignments of galaxies in hydrodynamic simulation using the projected shape correlation function, wg+, and the quadrupole,  . Combining the information of the measurements of the intrinsic alignment signals when projected over the three different axis in a simulation box (x, y, z), has led to an increased S/N in most studied cases. Combining two or three projections leads to a gain in S/N for both wg+ and

. Combining the information of the measurements of the intrinsic alignment signals when projected over the three different axis in a simulation box (x, y, z), has led to an increased S/N in most studied cases. Combining two or three projections leads to a gain in S/N for both wg+ and  , for shapes measured with the simple or reduced inertia tensor and for two distinct shape samples defined by n★ > 300 and log(M★ h/M⊙) > 10.5 (see Fig. 3 and Table 1). This gain in S/N when adding a second projection is robust under a change in Πmax, number of jackknife regions used in the covariance estimate and simulation box size (see Appendices A, B and C). There is additional gain in S/N when adding a third projection in the fiducial case, but this is sensitive to the aforementioned changes explored in Appendices A, B, C, and E, where the gain is more marginal.

, for shapes measured with the simple or reduced inertia tensor and for two distinct shape samples defined by n★ > 300 and log(M★ h/M⊙) > 10.5 (see Fig. 3 and Table 1). This gain in S/N when adding a second projection is robust under a change in Πmax, number of jackknife regions used in the covariance estimate and simulation box size (see Appendices A, B and C). There is additional gain in S/N when adding a third projection in the fiducial case, but this is sensitive to the aforementioned changes explored in Appendices A, B, C, and E, where the gain is more marginal.

Compared to the quadrupole measured in Singh et al. (2024) for TNG100, the  signals we measured in TNG300 and TNG100 are very comparable in amplitude and shape. An in-depth comparison is difficult as the scales probed by Singh et al. (2024) only partially overlap with those we chose to study. Regarding the wg+ signal, we find a good qualitative agreement with previous work. Very similar signal shapes and amplitudes have been measured by e.g. Samuroff et al. (2021) in TNG300, Illustris and MassiveBlack-II; Chisari et al. (2015) in HorizonAGN and Delgado et al. (2023) in MillenniumTNG740, where discrepancies between them mainly arise from differences in galaxy sample selections and the box sizes of the simulations used. In Fig. 1 we see the effect that sample selection can have on the amplitude of the signal and a similar comparison for TNG100 shows that the same sample definitions will lead to lower signal amplitudes in TNG100 when compared to TNG300.

signals we measured in TNG300 and TNG100 are very comparable in amplitude and shape. An in-depth comparison is difficult as the scales probed by Singh et al. (2024) only partially overlap with those we chose to study. Regarding the wg+ signal, we find a good qualitative agreement with previous work. Very similar signal shapes and amplitudes have been measured by e.g. Samuroff et al. (2021) in TNG300, Illustris and MassiveBlack-II; Chisari et al. (2015) in HorizonAGN and Delgado et al. (2023) in MillenniumTNG740, where discrepancies between them mainly arise from differences in galaxy sample selections and the box sizes of the simulations used. In Fig. 1 we see the effect that sample selection can have on the amplitude of the signal and a similar comparison for TNG100 shows that the same sample definitions will lead to lower signal amplitudes in TNG100 when compared to TNG300.

In agreement with (Singh et al. 2024), comparing the S/Ns of wg+ to  , the latter consistently yields a higher S/N for all considered samples, as shown in Fig. 3. However, this is strongly dependent on the chosen value of Πmax, as discussed in Appendix A. When comparing this to the gain in S/N created by adding the information of multiple projections we see that only when comparing the S/N using one projection for the quadrupole to the S/N using three projections for wg+, do we find that the S/N(3) for wg+ is larger than S/N(1) for

, the latter consistently yields a higher S/N for all considered samples, as shown in Fig. 3. However, this is strongly dependent on the chosen value of Πmax, as discussed in Appendix A. When comparing this to the gain in S/N created by adding the information of multiple projections we see that only when comparing the S/N using one projection for the quadrupole to the S/N using three projections for wg+, do we find that the S/N(3) for wg+ is larger than S/N(1) for  for a samples using reduced shapes, whereas adding a second projection to wg+ (S/N(2)) already produces are higher S/N than

for a samples using reduced shapes, whereas adding a second projection to wg+ (S/N(2)) already produces are higher S/N than  with one projection, represented by S/N(1), for simple shapes. This makes the multipole-based estimator a very promising avenue to extract information about IA models from measurements in a more optimal way, especially when multiple projections are combined. Future works could explore the effectiveness of combining multiple projections for other estimators, e.g. the one proposed by Lamman et al. (2025), which will likely show similar gains in S/N.

with one projection, represented by S/N(1), for simple shapes. This makes the multipole-based estimator a very promising avenue to extract information about IA models from measurements in a more optimal way, especially when multiple projections are combined. Future works could explore the effectiveness of combining multiple projections for other estimators, e.g. the one proposed by Lamman et al. (2025), which will likely show similar gains in S/N.

In this work, we model the correlation functions with the non-linear alignment model (Catelan et al. 2001), that has been shown to be a good model fit for observational galaxy alignment measurements (Singh et al. 2015; Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration 2023). Even though the χred2 indicate good fits for  and wg+, we detect a consistent mis-match of ∼25% between alignment amplitude obtained from the two different estimators. In Appendix F we show that this can be attributed to a different sensitivity of the estimators to nonlinear physics. Hence, we expect that not only more conservative scale cuts are necessary for

and wg+, we detect a consistent mis-match of ∼25% between alignment amplitude obtained from the two different estimators. In Appendix F we show that this can be attributed to a different sensitivity of the estimators to nonlinear physics. Hence, we expect that not only more conservative scale cuts are necessary for  for reliable modelling, but choices of Πmax will influence their comparability as well. More stringent restrictions on reliable scales reduce the total S/N of the measurement, possibly diminishing one of the main advantages of using multipole expanded correlation functions instead of projected ones. We conclude that, even though

for reliable modelling, but choices of Πmax will influence their comparability as well. More stringent restrictions on reliable scales reduce the total S/N of the measurement, possibly diminishing one of the main advantages of using multipole expanded correlation functions instead of projected ones. We conclude that, even though  has a higher S/N in measurement and corresponding alignment amplitude, better modelling is necessary to exploit the higher S/N of the measurement. The obtained fitted amplitudes are comparable in magnitude to Singh et al. (2024) who carried out a similar analysis on TNG100 data. However, the exact amplitude is highly dependent on galaxy definition and inertia tensor choice, as we demonstrated throughout this work.

has a higher S/N in measurement and corresponding alignment amplitude, better modelling is necessary to exploit the higher S/N of the measurement. The obtained fitted amplitudes are comparable in magnitude to Singh et al. (2024) who carried out a similar analysis on TNG100 data. However, the exact amplitude is highly dependent on galaxy definition and inertia tensor choice, as we demonstrated throughout this work.

Nevertheless, the obtained alignment amplitudes AIAbg are consistent between the different projection directions, both for individual and combined projections. By normalising the fitted amplitude with the modelling uncertainty, we obtain S/N(AAIbg). Similarly to the measurement S/N, we obtain a clear improvement when adding combining projections that subsequently decreases with number of projections. It must be noted that the improvement exceeds the theoretical limit  in the case of reduced shapes with mass cut for

in the case of reduced shapes with mass cut for  . The average improvement when going from one to two projections is slightly higher than

. The average improvement when going from one to two projections is slightly higher than  for this specific measurement. Furthermore, the S/N gain is smaller when going from one to three projections than from one to two projections for wg+ in the reduced inertia tensor sample obtained from the particle number cut. We believe this to be caused by a noisy covariance matrix that propagates into the modelling uncertainty with which we define the S/N(AAIbg), in particular since the gain exceeds the threshold for only one of the eight considered cases. This can be further investigated in the future by using more stable covariance matrix estimators.

for this specific measurement. Furthermore, the S/N gain is smaller when going from one to three projections than from one to two projections for wg+ in the reduced inertia tensor sample obtained from the particle number cut. We believe this to be caused by a noisy covariance matrix that propagates into the modelling uncertainty with which we define the S/N(AAIbg), in particular since the gain exceeds the threshold for only one of the eight considered cases. This can be further investigated in the future by using more stable covariance matrix estimators.

While the jackknife resampling technique is widely used for estimating covariance matrices, particularly in IA studies, it has known limitations. In the case of this work, it appears that our combined covariance matrix is only stable enough to provide robust results when using the resolution condition, described in Sect. 3.5. In the case of 125 jackknife regions, we filter out 0–6 (mean: 2) elements in the S/N calculation for one projection, 5–13 (7) for two and 9–17 (11) for three, where more elements are filtered out for the quadrupole than wg+ and simple than reduced shapes; and none of the elements that are used in fitting are filtered out. For 64 jackknife regions, in each case, more elements are filtered out than for 125 jackknife regions. Furthermore, we have seen in Appendix B that the results are sensitive to the number of jackknife regions used. To further investigate this, it would be valuable to compare our jackknife covariance matrix to an analytically calculated covariance matrix. This is a complicated task but presents a possibility for future research. Taking the example of Samuroff et al. (2021), they compare their jackknife covariance matrix to an analytically calculated matrix and find that on scales rp > 6 Mpc/h, the jackknife tends to underestimate the variance of wg+ by up to ∼25–50 percent for the TNG300 simulation.

Another viable avenue of further research would include being able to predict covariance of the analytical relations between the projected shapes of our measured ellipsoids. While this is outside of the scope of this work, it would provide insights into why we see a gain in information when adding multiple projections.

As many hydrodynamical simulations currently in use will have comparable or larger box sizes than TNG300, we can assume that our results can be used to measure the IA signals with a consistently larger S/N. Using relatively little computing power compared to the amount needed to run larger simulations, we can use the existing hydrodynamical simulations to better constrain modelling priors currently derived from these same simulations.

7. Conclusions

In this work, we have combined the information of shapes of galaxies projected over multiple axes, while taking their covariance into account, in hydrodynamical simulation TNG300. We show that a consistent and robust gain in S/N can be obtained for both wg+ and  by combining multiple projections. Below, the main conclusions are summarised.

by combining multiple projections. Below, the main conclusions are summarised.

-

Combining the information of more than one projection, the S/Ns of both wg+ and

are consistently larger than for a single projection (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

are consistently larger than for a single projection (Table 1 and Fig. 3). -

Adding a second projection leads to a larger gain in S/N than adding a third projection for both wg+ and

(Table 1 and Fig. 3).

(Table 1 and Fig. 3). -

The gain in S/N when adding two or three projections is larger for shapes measured with the reduced inertia tensor than with the simple inertia tensor (Table 1 and Fig. 3).

-

Table 1 shows that the gain in S/N for a high mass shape sample (log(M★ h/M⊙) > 10.5) is similar to that for all galaxies with resolved shapes (n★ > 300), where the high mass sample signal has a much higher amplitude (Fig. 1).

-

The S/N of the fitted amplitude obtained from the non-linear alignment model increases when adding projections in almost all cases but shows inconclusive systematic behaviour between estimators and sample selection. This is likely caused by the increased uncertainty on larger scales commonly used for modelling (Table 3 and Fig. 5).

Acknowledgments

We thank Casper Vedder for plenty of useful discussions. This publication is part of the project “A rising tide: Galaxy intrinsic alignments as a new probe of cosmology and galaxy evolution” (with project number VI.Vidi.203.011) of the Talent programme Vidi which is (partly) financed by the Dutch Research Council (NWO). DN and HH acknowledge support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program with Grant agreement No. 101053992.

References

- Abbott, T. M. C., Abdalla, F. B., Allam, S., et al. 2018, ApJS, 239, 18 [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, E., Abellán, G. F., Aboubrahim, A., et al. 2022, J. High Energy Astrophys., 34, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aihara, H., Arimoto, N., Armstrong, R., et al. 2018, PASJ, 70, S4 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Akitsu, K., Li, Y., & Okumura, T. 2023, Phys. Rev. D, 107, 063531 [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, A., Bernstein, G., Cahn, R., et al. 2006, Report of the Dark Energy Task Force [Google Scholar]

- Bate, J., Chisari, N. E., Codis, S., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 491, 4057 [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, G. M., & Jarvis, M. 2002, AJ, 123, 583 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick, A. K., Chen, Y., Tenneti, A., Di Matteo, T., & Mandelbaum, R. 2020, MNRAS, 491, 4116 [Google Scholar]

- Biagetti, M., & Orlando, G. 2020, JCAP, 2020, 005 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blazek, J., McQuinn, M., & Seljak, U. 2011, JCAP, 2011, 010 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bridle, S., & King, L. 2007, New J. Phys., 9, 444 [Google Scholar]

- Catelan, P., Kamionkowski, M., & Blandford, R. D. 2001, MNRAS, 320, L7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari, N. E., & Dvorkin, C. 2013, JCAP, 2013, 029 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari, N. E., Dvorkin, C., & Schmidt, F. 2014, Phys. Rev. D, 90, 043527 [Google Scholar]

- Chisari, N., Codis, S., Laigle, C., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 454, 2736 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chisari, N. E., Alonso, D., Krause, E., et al. 2019, ApJS, 242, 2 [Google Scholar]

- Cramér, H. 1946, Mathematical Methods of Statistics (Princeton University Press), Princeton Math. Ser. [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, R., Li, X., Nicola, A., et al. 2023, Phys. Rev. D, 108, 123519 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration (Abbott, T. M. C., et al.) 2023, Open J. Astrophys., 6, 36 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong, J. T. A., Verdoes Kleijn, G. A., Kuijken, K. H., & Valentijn, E. A. 2013, Exp. Astron., 35, 25 [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, A. M., Hadzhiyska, B., Bose, S., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 523, 5899 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, Y., Pichon, C., Welker, C., et al. 2014, MNRAS, 444, 1453 [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, D. J., & Zaldarriaga, M. 2001, ApJ, 546, 2 [Google Scholar]

- Fortuna, M. C., Hoekstra, H., Joachimi, B., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 501, 2983 [Google Scholar]

- Gaztañaga, E., & Scoccimarro, R. 2005, MNRAS, 361, 824 [Google Scholar]

- Genel, S., Vogelsberger, M., Nelson, D., et al. 2013, MNRAS, 435, 1426 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A. K., & Nagar, D. K. 2000, Matrix Variate Distributions (Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC) [Google Scholar]

- Hartlap, J., Simon, P., & Schneider, P. 2006, A&A, 464, 399 [Google Scholar]

- Hearin, A. P., Campbell, D., Tollerud, E., et al. 2017, AJ, 154, 190 [Google Scholar]

- Heymans, C., Tröster, T., Asgari, M., et al. 2021, A&A, 646, A140 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata, C. M., & Seljak, U. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 063526 [Google Scholar]

- Hirata, C. M., Mandelbaum, R., Ishak, M., et al. 2007, MNRAS, 381, 1197 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ivezić, Ž., Kahn, S. M., Tyson, J. A., et al. 2019, ApJ, 873, 111 [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, M., Bernstein, G., & Jain, B. 2004, MNRAS, 352, 338 [Google Scholar]

- Joachimi, B., & Bridle, S. L. 2010, A&A, 523, A1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Joachimi, B., Mandelbaum, R., Abdalla, F. B., & Bridle, S. L. 2011, A&A, 527, A26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Joachimi, B., Cacciato, M., Kitching, T. D., et al. 2015, Space Sci. Rev., 193, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Khandai, N., Di Matteo, T., Croft, R., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 450, 1349 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling, A., Cacciato, M., Joachimi, B., et al. 2015, Space Sci. Rev., 193, 67 [Google Scholar]

- Kilbinger, M. 2015, Rep. Progr. Phys., 78, 086901 [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, D., Brown, M. L., Hoekstra, H., et al. 2015, Space Sci. Rev., 193, 139 [Google Scholar]

- Krause, E., Eifler, T., & Blazek, J. 2015, MNRAS, 456, 207 [Google Scholar]

- Kumwembe, A. A., Lamman, C., Eisenstein, D., et al. 2025, Enhancing Multiplet Alignment Measurements with Imaging [Google Scholar]

- Kurita, T., & Takada, M. 2023, Constraints on Anisotropic Primordial Non-Gaussianity From Intrinsic Alignments of SDSS-III BOSS Galaxies [Google Scholar]

- Lamman, C., Tsaprazi, E., Shi, J., et al. 2024, Open J. Astrophys., 7 [Google Scholar]

- Lamman, C., Blazek, J., & Eisenstein, D. J. 2025, Optimal Intrinsic Alignment Estimators in the Presence of Redshift-space Distortions [Google Scholar]

- Landy, S. D., & Szalay, A. S. 1993, ApJ, 412, 64 [Google Scholar]

- Laureijs, R., Amiaux, J., Arduini, S., et al. 2011, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:1110.3193] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A., & Bridle, S. 2002, Phys. Rev. D, 66 [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Zhang, T., Sugiyama, S., et al. 2023, Phys. Rev. D, 108, 123518 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbaum, R., Hirata, C. M., Ishak, M., Seljak, U., & Brinkmann, J. 2006, MNRAS, 367, 611 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbaum, R., Blake, C., Bridle, S., et al. 2011, MNRAS, 410, 844 [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, F. G., & Percival, W. J. 2022, MNRAS, 514, 1289 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, D., Springel, V., Pillepich, A., et al. 2021, The IllustrisTNG Simulations: Public Data Release [Google Scholar]

- Norberg, P., Baugh, C. M., Gaztañaga, E., & Croton, D. J. 2009, MNRAS, 396, 19 [Google Scholar]

- Okumura, T., & Taruya, A. 2023, ApJ, 945, L30 [Google Scholar]

- Philcox, O. H., Ivanov, M. M., Zaldarriaga, M., Simonović, M., & Schmittfull, M. 2021, Phys. Rev. D, 103 [Google Scholar]

- Quenouille, M. H. 1956, Biometrika, 43, 353 [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C. R. 1945, Bull. Calcutta Math. Soc., 37, 81 [Google Scholar]

- Samuroff, S., Mandelbaum, R., & Blazek, J. 2021, MNRAS, 508, 637 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schaye, J., Crain, R. A., Bower, R. G., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 446, 521 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, F., Chisari, N. E., & Dvorkin, C. 2015, JCAP, 2015, 032 [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, M. D., & Bridle, S. 2010, MNRAS, 402, 2127 [Google Scholar]

- Secco, L. F., Samuroff, S., Krause, E., et al. 2022, Phys. Rev. D, 105, 023515 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J. 1986, Ann. Stat., 14, 1322 [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., & Mandelbaum, R. 2016, MNRAS, 457, 2301 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., Mandelbaum, R., & More, S. 2015, MNRAS, 450, 2195 [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S., Shakir, A., Jagvaral, Y., & Mandelbaum, R. 2024, Increasing the Power of Weak Lensing Survey Data with Multipole-based Intrinsic Alignment Estimators [Google Scholar]

- Soussana, A., Chisari, N. E., Codis, S., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 492, 4268 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spergel, D., Gehrels, N., Baltay, C., et al. 2015, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:1503.03757] [Google Scholar]

- Springel, V. 2010, MNRAS, 401, 791 [Google Scholar]

- Springel, V., White, S. D. M., Tormen, G., & Kauffmann, G. 2001, MNRAS, 328, 726 [Google Scholar]

- Springel, V., Pakmor, R., Pillepich, A., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 475, 676 [Google Scholar]

- Tenneti, A., Singh, S., Mandelbaum, R., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 448, 3522 [Google Scholar]

- Tenneti, A., Gnedin, N. Y., & Feng, Y. 2017, ApJ, 834, 169 [Google Scholar]

- Tenneti, A., Kitching, T. D., Joachimi, B., & Di Matteo, T. 2020, MNRAS, 501, 5859 [Google Scholar]

- Troxel, M. A., & Ishak, M. 2011, MNRAS, 419, 1804 [Google Scholar]

- Troxel, M., & Ishak, M. 2015, Phys. Rep., 558, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tukey, J. W. 1958, Ann. Math. Stat., 29, 588 [Google Scholar]

- Velliscig, M., Cacciato, M., Schaye, J., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 453, 721 [Google Scholar]

- Vlah, Z., Chisari, N. E., & Schmidt, F. 2020, JCAP, 2020, 025 [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, D. H., Mortonson, M. J., Eisenstein, D. J., et al. 2013, Phys. Rep., 530, 87 [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, J. 1928, Biometrika, 20A, 32 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K., Jing, Y. P., Zhao, G.-B., & Cuesta, A. J. 2023, Nat. Astron., 7, 1259 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P. 2010, MNRAS, 406, L95 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Πmax