| Issue |

A&A

Volume 702, October 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A192 | |

| Number of page(s) | 16 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555980 | |

| Published online | 22 October 2025 | |

The gravitational potential of spiral perturbations

I. The 2D (razor-thin) case

Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Mönchhofstraße 12-14, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

⋆ Corresponding author: walter.dehnen@uni-heidelberg.de

Received:

16

June

2025

Accepted:

1

August

2025

I developed an efficient numerical method for obtaining the gravitational potential of razor-thin spiral perturbations and used it to assess the standard tight-winding approximation, which is found to be reasonably accurate for pitch angles α ≲ 20°. I derived the analytic potential of razor-thin logarithmic spirals with an arbitrary power-law amplitude. Approximating a spiral locally by one of these models provides a second-order tight-winding approximation that predicts the phase offset between the spiral potential and density, the resulting radially increasing pitch of the potential, and the nonlocal outward angular-momentum transport by gravitational torques. Beyond the inner and outer edge of a spiral with m arms, its potential is not winding (α = 90°), decays like Rm and R−1 − m, respectively, and cannot be predicted by a local approximation.

Key words: methods: analytical / methods: numerical / galaxies: spiral / galaxies: structure

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Spiral density perturbations are ubiquitous in late-type galaxies (by definition), and they are an important ingredient for the formation and evolution of these galaxies because the resulting non-axisymmetric gravitational forces alter the otherwise simple dynamics of the interstellar medium (ISM) and of the stars. The ISM is often strongly affected and forced to high densities, which triggers star formation, while the perturbation of the stellar orbits leads to radial migration and radial heating (Sellwood & Binney 2002), which correspond to diffusion in the orbital actions Jϕ and JR, respectively.

Studies of these processes often require some model for the gravitational potential of the spiral perturbations, and in many situations, it is only necessary to model the dynamics in two dimensions without considering the vertical motions. Unfortunately, the only known gravitational potential for a flat (razor-thin) spiral density perturbation is that developed by Kalnajs’ (1971), which has an amplitude that declines with radius like R−3/2 and is unsuitable as a model for galactic spirals. Instead, the tight-winding approximation (often also called ‘WKB approximation’1) allows reasonably accurate estimates for the gravitational potential of a spiral pattern with a pitch angle α ≲ 20°.

Dynamical modellers typically employ simple models for the gravitational potential (e.g. Roberts et al. 1979; Contopoulos & Grosbøl 1986; Eilers et al. 2020; Hamilton et al. 2024) that are often based on this approximation. However, the actual density corresponding to these models has never been computed. Similarly, the actual potential generated by reasonably realistic spiral density perturbations is largely unknown.

The purpose of this study is to fill these gaps. To this end, I implement in Appendix B an efficient numerical tool for finding the gravitational potential for any flat density and, vice versa, the density from the potential known in the equatorial plane only. This tool is then applied to assess the accuracy of the tight-winding approximations, including a more accurate novel version, for logarithmic spirals with amplitude that declines with radius either as a power law or exponentially (like the surface density of disc galaxies) with and without radial truncation. I also obtain the actual density of models for spiral potentials that have been used in previous studies, and find that the density sometimes behaves in unexpected ways. For example, the pitch angle can deviate significantly from the target.

Finally, I consider the gravitational torques of a spiral perturbation and derive an approximate expression for their local mean at each radius. For trailing spirals, this is always negative at small and positive at large radii, implying an outward angular-momentum transport (Zhang 1996), in addition to the advective angular momentum transport by diffusion driven by the standard deviation of the torques.

I begin the presentation in Section 2 by introducing my notations and giving a brief overview over known results, including the tight-winding approximation. In Section 3, I extend Kalnajs’ (1971) potential-density pairs to logarithmic spirals whose density amplitude is an arbitrary power law in radius. I also develop a novel more accurate tight-winding approximation. Section 4 considers the non-local gravitational torque induced by a spiral perturbation. In Section 5, I consider various models for spiral perturbations and compare their numerically computed properties to the predictions of the tight-winding approximations. Finally, Sections 6 and 7 discuss my findings and present my conclusion.

2. Spiral density perturbations

This section introduces basic concepts and notations and summarises the important tight-winding approximation, but presents no novel results.

2.1. Poisson’s equation for razor-thin systems

This study exclusively considers the situation of razor-thin mass distributions with some surface density Σ(R), where R ≡ (x, y), and the spatial density ρ(r) = Σ(R) δ(z), where r ≡ (x, y, z) = (R, z). The gravitational potential

satisfies the Poisson equation ΔΦ(r) = 4πG ρ(r), which implies

However, often only the potential in the equatorial plane Ψ(R)≡Φ(R, z = 0) is required or even known, when Eq. (1) becomes

The inverse operation, obtaining Σ(R) from Ψ(R), is not as straightforward as for three-dimensional models because Eq. (2) cannot be used. Nonetheless, a useful relation can be inferred from the fact that a razor-thin plane density wave Σ ∝ eik ⋅ R has the potential Φ(r) = Ψ(R)e−k|z|, where k = |k| and

It follows that in Fourier space, Eq. (3) becomes  or

or  , where a hat denotes the Fourier transform. Thus, −ΔΨ relates to 2πGΣ in exactly the same way as 2πGΣ relates to Ψ, and therefore,

, where a hat denotes the Fourier transform. Thus, −ΔΨ relates to 2πGΣ in exactly the same way as 2πGΣ relates to Ψ, and therefore,

(H. Dejonghe in Binney & Tremaine 2008, problem 2.22; see Appendix A for a proof without Fourier transform). Thus, obtaining Σ(R) from Ψ(R) requires a similar effort as the inverse relation and can be achieved with the same numerical or analytic tools. Appendix B details the numerical tool I used in this study.

2.2. Spiral patterns

The density and potential of the disc can be uniquely decomposed into azimuthal Fourier components of the general form

with amplitudes Pm, Sm ≥ 0 and phases ψΨ, ψΣ, which are real-valued functions of the radius R = |R|. As usual, the physical potential and density are given by the real parts of Eqs. (6), and we can assume m ≥ 0 without loss of generality. For a spiral pattern, the phase is a monotonously increasing (or decreasing) function of radius. The pitch angle α > 0 between the wave crest at ϕ = ψ(R) and concentric circles relates to the phase via

where σ = ±1 gives the sense in which the spiral twists, such that α > 0. Galactic spirals are trailing, implying  , where

, where  is the mean azimuthal (rotational) velocity. The pitch angles of galactic spirals tend to vary with radius (Kennicutt 1981; Savchenko & Reshetnikov 2013; Chugunov et al. 2025), but a widespread model is that of a constant pitch angle, which is obtained for

is the mean azimuthal (rotational) velocity. The pitch angles of galactic spirals tend to vary with radius (Kennicutt 1981; Savchenko & Reshetnikov 2013; Chugunov et al. 2025), but a widespread model is that of a constant pitch angle, which is obtained for

and referred to as a ‘logarithmic spiral’. In this case, the phase factors in Eqs. (6) become eim[ϕ − λln(R/R0)], which is a plane wave in both ϕ and lnR.

Except for models with power-law amplitudes (see Section 3), no analytic solutions to Eq. (3) are known for spirals of the general form (6a). Instead, the following approximation is often employed.

2.3. The tight-winding (or WKB) approximation

Each annulus of a disc with, say, an m = 2 perturbation generates a quadrupolar gravitational field. For a bar-like perturbation, these quadrupoles have the same orientation, and their contributions to the field at some position accumulate. For a spiral, on the other hand, the orientations vary with radius, and most of the contributions from distant annuli to the local field cancel (destructive interference), such that it is dominated by the local pattern. To estimate the field from the local pattern, the curvature of the spiral can be ignored and it can be approximated as a plane wave. In analogy to the relation (4), this gives (Toomre 1964; Lin & Shu 1964)

where k(R) is a locally appropriate horizontal wavenumber. Following Lin & Shu (1964), k(R) is traditionally taken to be just the radial wavenumber

However, the analogy to plane waves suggests the absolute value of the horizontal wavevector, which also includes the azimuthal wavenumber kϕ = m/R, i.e.

Thus, the potential is weaker for more arms (larger m) and more tightly wound spirals (smaller α). Apparently, Eq. (10b) has not been used explicitly, but is implicit in shearing-sheet approaches for modelling spiral structure (e.g. Julian & Toomre 1966, Eq. (11)). Both Eqs. (10) are first-order accurate in the sense that the fractional error made in Eq. (9) is 𝒪(sin α) and the total error 𝒪(sin2α), but Eq. (10b) is significantly better than Eq. (10a), as demonstrated in Figs. 2 and 3.

In general, the phases ψΨ and ψΣ of the potential and density of a spiral perturbation differ, but the first-order approximations (10) give ψΨ = ψΣ and hence do not predict the phase offset δψ ≡ ψΨ − ψΣ. Shu’s (1970) second-order approximation

predicts δψ, but does not provide Ψ(R) for a given Σ(R).

3. Scale-invariant spirals

A simple situation is that of a logarithmic spiral whose density amplitude follows a power law in radius,

such that the total R dependence, Σ ∝ R−γ − imλ, is still a power law and hence scale-invariant. The gravitational potential of these models is (see Appendix D for a derivation)

with spherical radius r = |r| and

where

and Pν m(x) denotes the associated Legendre function of the first kind. The function fm describes the run of Φ(r) with latitude and at x → 1 declines like (1 − x)m/2.

This study focusses on the potential in the z = 0 plane,

where

which satisfies Km(−ζ) = Km(ζ), Km(ζ*) = Km*(ζ) (where a star denotes complex conjugation), and

Interpolating these relations gives the asymptotic behaviour

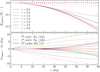

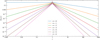

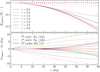

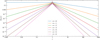

which is an excellent approximation even for pitch angles as large as 40°, as Fig. 1 demonstrates.

|

Fig. 1. Assessing the accuracy of the approximation (20) for m = 2 (for m > 2 the accuracy is better). The real (imaginary) parts are even (odd) functions of |

For these scale-invariant spirals, the potential Ψ and density Σ are proportional to the same phase factor eim[ϕ − λln(R/R0)], such that they have the same constant pitch angle α. For  , ζ is real-valued, and hence, so are fm(x) and Km(ζ), such that Ψ and Σ even have the same phase ψ(R). In this case, Sm ∝ R−3/2 and Pm ∝ R−1/2, and we obtain the potential-density pairs of Kalnajs (1971), who for real-valued ζ gave Ψ(R) with Eqs. (17,18) and an inferior version of Eq. (20).

, ζ is real-valued, and hence, so are fm(x) and Km(ζ), such that Ψ and Σ even have the same phase ψ(R). In this case, Sm ∝ R−3/2 and Pm ∝ R−1/2, and we obtain the potential-density pairs of Kalnajs (1971), who for real-valued ζ gave Ψ(R) with Eqs. (17,18) and an inferior version of Eq. (20).

For  , however, Km(ζ) is complex-valued and causes a constant phase offset δψ = −arg(Km(ζ))/m of Ψ with respect to Σ (see also Fig. 2), such that for a trailing spiral, the potential lags the density for

, however, Km(ζ) is complex-valued and causes a constant phase offset δψ = −arg(Km(ζ))/m of Ψ with respect to Σ (see also Fig. 2), such that for a trailing spiral, the potential lags the density for  and leads it for

and leads it for  (Zhang 1996).

(Zhang 1996).

|

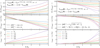

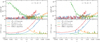

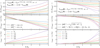

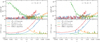

Fig. 2. Assessing the tight-winding (WKB) approximation for scale-invariant spirals. The relative error of the density amplitude and the error in the phase offset δψ ≡ ψΨ − ψΣ are plotted vs. pitch angle α for m = 2 and various values of the exponent γ (for these scale-invariant models, the errors are the same at each radius). Since the first-order approximations give δψapprox = 0, their error reflects the actual phase offset of the models. |

As shown in the next section, this constant offset would imply a non-vanishing total torque in contradiction to Noether’s theorem. However, when the total torque is expressed as an integral over pairs of annuli torquing each other, it is found to be zero. This contradiction arises because of the unphysical nature of these models at R → 0 (see Appendix E for details).

3.1. Comparison with the tight-winding approximation

The scale-invariant spirals have no inner or outer edge, such that there is a local spiral field everywhere. This makes these models the ideal situation for the tight-winding approximation. Fig. 2 plots the errors in amplitude and phase made by the first- (10) and second-order approximation (11), respectively. The traditional tight-winding approximations (10a) and (11) underestimate the density or, conversely, overestimate the potential and forces, but the first-order approximation (10b) only makes very small errors in amplitude. The order of the approximations is only obvious in the phase error (a peculiarity of these power-law models), where the first-order methods predict δψ = 0, while the phase error of the second-order approximation is quadratic in the pitch angle, as expected.

For  (red; Kalnajs’ 1971 spirals), ψΨ = ψΣ and the approximation using Eq. (10b) is identical to Eq. (20) and hence extremely accurate. Away from the z = 0 plane, however, the tight-winding approximation deteriorates, as it predicts ψΨ(R, z) = ψΣ(R), while actually

(red; Kalnajs’ 1971 spirals), ψΨ = ψΣ and the approximation using Eq. (10b) is identical to Eq. (20) and hence extremely accurate. Away from the z = 0 plane, however, the tight-winding approximation deteriorates, as it predicts ψΨ(R, z) = ψΣ(R), while actually  , i.e. the phase is in fact constant on spheres, not on cylinders. A more detailed assessment of the potential and its approximation away from the plane is beyond the scope of this study.

, i.e. the phase is in fact constant on spheres, not on cylinders. A more detailed assessment of the potential and its approximation away from the plane is beyond the scope of this study.

3.2. An improved tight-winding approximation

In the traditional tight-winding approximation, a spiral is locally approximated as plane wave, i.e. assumed to have constant amplitude and pitch angle α ∝ R. The amplitude might instead be assumed to decline locally like a power law and the pitch angle be constant. In other words, the spiral is approximated locally as a scale-invariant spiral. When its potential is in turn approximated via Eq. (20), it can be expressed in the standard form (9) using the complex-valued wavenumber

where the principal value of the square root is taken and

with λ(R) as defined in Eq. (7) and γ(R)≡ − dlnSm/dlnR.

It is also possible to set ![$ \zeta(R) = {\text{ i}}[\frac 1 2 + (R/\Psi)(\partial\Psi/\partial R)] $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq37.gif) , which allows the approximation of Σ(R) given Ψ(R), and, when also approximating

, which allows the approximation of Σ(R) given Ψ(R), and, when also approximating  , gives the second-order approximation (11). A somewhat more simply computable and manipulable form than Eq. (21) is provided by the Taylor expansion,

, gives the second-order approximation (11). A somewhat more simply computable and manipulable form than Eq. (21) is provided by the Taylor expansion,

where  . When this is truncated at zeroth order in ϵ (or for

. When this is truncated at zeroth order in ϵ (or for  when ϵ = 0), this collapses to the first-order approximation (10b). These relations suggest that the novel approximation (21) is at least second-order accurate. In terms of the pitch angle α (instead of λ), the approximation (9) resulting from the expansion (23) is conveniently expressed as

when ϵ = 0), this collapses to the first-order approximation (10b). These relations suggest that the novel approximation (21) is at least second-order accurate. In terms of the pitch angle α (instead of λ), the approximation (9) resulting from the expansion (23) is conveniently expressed as

Section 5 assesses this together with the first-order approximations for various spiral models.

4. The gravitational torque of spiral perturbations

A spiral perturbation exerts a gravitational torque per unit mass of −∂Φ/∂ϕ. This induces changes in the stellar angular momenta, which cause radial migration (Sellwood & Binney 2002) and are particularly pronounced for stars that co-rotate with the spiral pattern (and for stars on the Lindblad resonances) because they experience coherent torquing, while the torques largely average away for other stars. The distribution of angular-momentum changes δJϕ induced by these torques per unit time is characterised by its first two moments ⟨δJϕ⟩ and ⟨(δJϕ)2⟩. The second moment determines the local diffusion of Jϕ, which causes advective angular-momentum transport.

The first moment, ⟨δJϕ⟩, describes non-local angular-momentum transport and is caused by the average torque at fixed Jϕ. While the azimuthal average of −∂Φ/∂ϕ vanishes, that of the torque density τ ≡ −Σ(∂Ψ/∂ϕ) does not in general vanish because the distribution of stars is not axially symmetric owing to the spiral pattern itself. For potential and density perturbations of the form (6), the azimuthal average of τ is (Zhang & Buta 2007)

if mΨ = mΣ = m and ⟨τ⟩ϕ = 0 otherwise. Thus, if the potential and density are out of phase at radius R, a spiral perturbation exerts a net torque over the annulus. For a trailing spiral, if σ δψ < 0 the potential leads the density, and stars gain angular momentum on average. Conversely, if σ δψ > 0, the potential trails the density, and stars lose angular momentum on average.

According to Noether’s theorem, the total angular momentum is conserved. The total torque over the whole disc, T = 2π∫0∞⟨τ⟩ϕR dR, therefore vanishes (as shown explicitly in Appendix E), and these gains and losses at different radii balance, but constitute a non-local transport of angular momentum from regions where σδψ > 0 to those where σδψ < 0.

The azimuthally averaged torque density ⟨τ⟩ϕ can be computed from the numerically computed potential for any spiral density perturbation, but a simple way to approximate it would be insightful.

4.1. Torque in the tight-winding approximation

For a density component of the form (6a), the approximation (9) gives for the azimuthally averaged torque density

The first-order approximations (10) have real-valued k(R) and hence give ⟨τ⟩ϕ = 0. This is not surprising: As the product of the first-order quantities Pm and sin δψ, the torque is a second-order quantity and cannot be predicted by first-order approximations. For the novel approximation (24), we find

4.2. Torque from the potential

Instead of estimating ⟨τ⟩ϕ from the target density and its second-order approximate potential as above, I now compute it for a first-order approximate potential and its (unknown) actual density using the exact expression (Binney & Tremaine 2008, Eq. 6.18)

for the cumulative disc torque T(R)≡2π∫0RdR′R′⟨τ⟩ϕ(R′). In order to apply this, we must evaluate the integral over z. For the first-order tight-winding approximation based on plane waves, the natural approximation is Φ(r) = Ψ(R)e−k(R)|z|, when the integral over z gives a factor 1/k(R), and we obtain after inserting Eqs. (6a) and (9), taking the derivatives, integrating over ϕ (and recalling that only the real part of Ψ has meaning)

The azimuthally averaged torque density can now be estimated as ⟨τ⟩ϕ = (dT/dR)/(2πR), which for the approximation (10b) again gives Eq. (27). As T(R) in Eq. (29) vanishes for R → ∞ (provided Sm decays faster than R−3/2 in this limit), this also implies that the estimate (27) obtains zero total torque exactly.

5. Application: The potential of spirals

I now consider various models for spiral perturbations and study the associated gravitational potentials, but also assess the ability of the tight-winding approximations to predict them.

5.1. Spirals with an exponential amplitude profile

The unperturbed (m = 0) surface density of disc galaxies generally follows an exponential decline,

A simple and natural model for a spiral is one with a constant relative amplitude Am ≡ |Σm|/Σ0 (Section 5.2.3 considers Am to depend on radius). Logarithmic spirals with this amplitude have the density

where Σsp = AmΣc. I now consider various tight-winding approximations for the gravitational potential as well as that computed numerically.

5.1.1. Assessing the tight-winding approximations

A common model is

with some (often unspecified) constant AΨ, which corresponds to the first-order approximation (9) with Eq. (10a) if

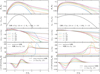

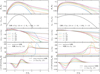

(Contopoulos & Grosbøl 1986, and several subsequent studies) or Eq. (10b) if AΨ = 2πGΣspm−1sin α. For constant and real-valued AΨ, the potential has the same phase as the target density (31), such that αΨ = α. My novel approximation can be expressed in this form by setting AΨ to a complex-valued function of radius. For five values of α, I compute numerically (via Eq. 5 and the gravity solver of Appendix B) the surface densities Σ(R) corresponding to these potential approximations and compare in Fig. 3 their properties to those of the target (31).

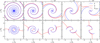

|

Fig. 3. Assessing the ability of the first-order (left) and our novel (right) tight-winding approximations to provide a gravitational potential for the target density (31) of a logarithmic spiral with pitch angle α and exponentially declining amplitude. From the density that is actually generated by the approximate potential, I plot the radial profiles of the relative amplitude error (top) and the errors in phase (middle) and pitch angle (bottom), which for the first-order methods are also the respective offsets between the potential and density because to first order, ψΨ = ψtarget. |

The first-order method using the non-standard k(R) in Eq. (10b) approximates the amplitude significantly better than the standard form (10a). However, the two first-order methods give the same phase for the density as for the potential, and hence, an incorrect phase offset and pitch angle for the density, while the novel approximation gives an excellent match for R ≲ 3Rd or α ≲ 20 and still a reasonably accurate density phase at higher values. The full version of my novel approximation (Eq. (21)) is somewhat better than its reduced form (Eqs. (23) or (24)), but the difference is only significant in the regime where neither is very good any more.

The failure of all the tight-winding approximations at larger radii is not surprising because owing to the exponentially declining amplitude, the local field (on which these approximations are based) becomes ever less relevant compared to the far field from the inner parts (ignored by these approximations).

5.1.2. The exact gravitational potential

Finally, I also numerically computed the actual potential generated by the density (31) and plot in Fig. 4 its amplitude relative to that of the traditional first-order tight-winding approximation, as well as the phase offset and the deviation of the pitch angle between the density and potential. While these relations are apparently not easy to predict by tight-winding approximations for large radii and/or pitch angles, they are sufficiently smooth for interpolation, allowing a cost-efficient numerical implementation.

|

Fig. 4. Properties of a spiral with density (Eq. (31)) and its (numerically computed) potential. Radial profiles of the amplitude ratio to the first-order tight-winding approximation (Eqs. (9) and (10b)), the offsets of phase and pitch angle between the potential and density, and the torque per annulus (< 0 if angular momentum is lost for stars in a galaxy with a trailing spiral). |

Again, the pitch of the potential is larger than that of the density and increases with radius at large αΣ and R even more so than predicted by our novel second-order approximation.

In the bottom panel Fig. 4, I plot the contribution −σdT/dR of each annulus to the total torque. Owing to the increasing phase offset δψ between the potential and density changing sign at  , the torque is negative (for a trailing spiral) at

, the torque is negative (for a trailing spiral) at  and positive at

and positive at  (such that total angular momentum remains conserved).

(such that total angular momentum remains conserved).

The approximation (27) only slightly underestimates the local torque (dashed in the bottom panel of Fig. 4) and makes a much better impression than the approximations for the potential on which it is based. Moreover, the differences between Eq. (27) and its parent (Eq. (26) with k from Eq. (21)) are very small (not shown).

5.2. Radially tapered spirals

All the spirals considered so far extend radially over the whole disc, but real spirals may be limited to a radial range or, equivalently, an azimuthal range. Theoretical analysis of orbits perturbed by a spiral pattern suggest that the response of the system is in phase with the spiral only in a region around the co-rotation resonance (e.g. Contopoulos & Grosbøl 1986), and N-body simulations also show spiral patterns to be confined to a region around co-rotation and limited by the Lindblad resonances (Sellwood & Carlberg 2019). Moreover, in barred galaxies, spiral structures are mostly absent from the bar region.

5.2.1. The phase factor of Roberts et al.

With the goal to model a spiral that begins just outside a bar, Roberts et al. (1979) applied the phase

to the potential

with m = 2. At R ≪ Rsp, this phase function evaluates to zero and the potential perturbation stays aligned (α = 90°) as for a bar, but at R > Rsp, the potential perturbation becomes spiral-like, reaching a pitch angle of α → α∞ at R ≫ Rsp with the sharpness of the transition determined by the parameter N. In case of a constant phase ψ, (35a) is the potential of a razor-thin perturbation with density2

but for the phase (34) no formula for the associated density exists (and Roberts et al. 1979 did not attempt to estimate it). I computed it numerically (for the same parameter values as used by Roberts et al.) and plot in Fig. 5 its amplitude, phase, and pitch angle. The latter switches indeed from α = 90° at small R to α = α∞ at large R as intended, albeit perhaps not as cleanly as for the potential: The bar region (R < Rsp = 1.8s indicated by grey lines in Fig. 5) is significantly pitched, and most of the torque exchange occurs within this region.

|

Fig. 5. Properties of the (numerically computed) density that generates the potential (35a) with the phase ψ = ψR79(R) (Eq. 34) for Rsp = 1.8a (grey vertical line) and N = 5 (as used by Roberts et al. 1979) and various values for α∞ (Roberts et al. used α∞ = 20°). For α∞ = 90°, ψ = 0, and the density is given by Eq. (35b). |

The density declines like Σ ∝ Ψm/R ∝ R−4, as expected from the tight-winding approximation (9), and less steeply than for the bar-like case (α∞ = 90°), i.e. Σ ∝ R−5 (Eq. 35b). The unperturbed (m = 0) component of the model used by Roberts et al. was also of type (35), such that the relative amplitude of the spiral declined like R−4/R−3 = 1/R.

At least two recent studies applied the phase (34) with N = 100 to the potential (32), with the intention of having a spiral pattern only at R > Rsp, but unaware that at R < Rsp this generates a bar-like perturbation (in addition to any other explicitly modelled bar) with significant σψ′Σ < 0 (twisting the wrong way) near R = Rsp. I abstain from plotting these nonsensical models.

5.2.2. The spirals of Hamilton et al.

Hamilton et al. (2024) used a model with the potential being a logarithmic spiral,

with

where  with Rcr the co-rotation radius of the spiral pattern. Hamilton et al. modelled the m = 0 component of the total potential as Ψ = v02lnR, such that η is the (maximum of the) ratio of the tangential force to the unperturbed force. Moreover, for this model the epicycle and circular frequencies are related as

with Rcr the co-rotation radius of the spiral pattern. Hamilton et al. modelled the m = 0 component of the total potential as Ψ = v02lnR, such that η is the (maximum of the) ratio of the tangential force to the unperturbed force. Moreover, for this model the epicycle and circular frequencies are related as  , such that the Lindblad resonances are located at

, such that the Lindblad resonances are located at  , and for β = 1 the standard deviation of the potential envelope BH24 equals the distance to the Lindblad resonances. Hamilton et al. considered

, and for β = 1 the standard deviation of the potential envelope BH24 equals the distance to the Lindblad resonances. Hamilton et al. considered  , β = 1, and β = ∞. The latter case is identical to the scale-invariant spirals (Eq. (16)) with γ = 1, while for finite β, I computed Σ(R) numerically.

, β = 1, and β = ∞. The latter case is identical to the scale-invariant spirals (Eq. (16)) with γ = 1, while for finite β, I computed Σ(R) numerically.

A common measure of the spiral strength is the ratio Am = |Σm/Σ0| of the density amplitudes of the perturbation and the unperturbed (m = 0) disc. I obtained (a lower limit for) Am by assuming a maximum disc for the m = 0 component, i.e. Eq. (30) with Σc = 0.411 v02/GRd, such that the maximum circular speed generated by the disc alone (without the dark-matter halo) equals v0.

In Fig. 6, the resulting Am = 2 is plotted (in the second panel from top) for the parameter choices used by Hamilton et al. (2024) and Rcr = 1.5Rd, while the lower panels show the phase offset and density pitch angle as in previous figures. For β = ∞, which is their favourite model, Am = 2 has an inverted profile with a minimum at R = Rd. Towards smaller and larger radii, it increases and eventually exceeds unity, implying negative density. The finite-β models do not suffer from this issue (except at R ≪ Rd), but their spiral strength Am = 2 is not symmetric with respect to R = Rcr (unlike the potential amplitude) and peaks at R > Rcr.

|

Fig. 6. Assessing the model (36) used by Hamilton et al. (2024) for the same parameters as used by these authors. Plotted as function of radius from top to bottom, I show the relative perturbation strength of the forces, the relative amplitude Am = 2 of the density perturbation (assuming the unperturbed disc is maximal with scale radius related to the co-rotation radius of the spiral as Rcr = 1.5Rd), the phase offset between the potential and density, and the density pitch angle. |

For the model  with α = 30°, the density pitch angle decreases at R > Rcr, implying that the spiral becomes tighter than anticipated by Hamilton et al. (2024). The implications of all these properties for the results of the study by Hamilton et al. (2024) are discussed in Section 6.5.

with α = 30°, the density pitch angle decreases at R > Rcr, implying that the spiral becomes tighter than anticipated by Hamilton et al. (2024). The implications of all these properties for the results of the study by Hamilton et al. (2024) are discussed in Section 6.5.

5.2.3. Spirals with simple density models

All the models considered so far (with the exception of Fig. 4) were specified via the spiral potential, which is required for dynamical modelling. Unfortunately, as we have seen, simple potentials tend to correspond to spiral density patterns that deviate from the target, in particular, if the spiral pattern is restricted in radius. Instead, I now consider simple models in the density and numerically compute the corresponding potential.

I still assumed that the unperturbed (m = 0) density is of the form (30) and that the relative amplitude of the spiral perturbation is Am(R) = |Σm|/Σ0. The spiral perturbation then has the density

For constant Am, this is identical to the target density (31) from the previous section, whose potential was presented in Fig. 4. Instead, I now consider simple non-constant amplitude functions of the form

and plot in Fig. 7 for  and 1 (β = ∞ gives the model shown in Fig. 4) the same quantities as for the models of Hamilton et al. in Fig. 6, plus the torque per annulus.

and 1 (β = ∞ gives the model shown in Fig. 4) the same quantities as for the models of Hamilton et al. in Fig. 6, plus the torque per annulus.

|

Fig. 7. Similar to Fig. 6, but for the density models of Eq. (37a) with constant pitch angle α and relative perturbation density-amplitude Am(R) = AmaxBH24(R, β), i.e., the same profile as the relative perturbation force-amplitude for the model of Hamilton et al. (2024, shown in Fig. 6) for |

A comparison of these two figures shows many similarities: (i) The relative force perturbation peaks at smaller radii than the relative density perturbation, although this effect is weaker for our more realistic density models, where it is hardly present for  . (ii) At radii where Am is significant (not much smaller than its maximum), the phase offset δψ ≡ ψΨ − ψΣ decreases slowly with radius (already seen in Fig. 4), and the potential pattern becomes more open with an outward-increasing pitch angle (although this effect is much weaker for the density models). Finally, (iii) at large radii where Am is insignificant, the potential decays like R−1 − m with αΨ = 90°. This is simply the expected behaviour for the outer field of the inner spiral (e.g. Binney & Tremaine 2008, Eq. (2.93)) without any significant local perturbation, and it is therefore also impossible to predict via the tight-winding approximations (dashed in Fig. 7). In the transition regions, at the edges of the spiral, the potential perturbation even twists backwards, as indicated by the pitch angle of the potential exceeding 90°.

. (ii) At radii where Am is significant (not much smaller than its maximum), the phase offset δψ ≡ ψΨ − ψΣ decreases slowly with radius (already seen in Fig. 4), and the potential pattern becomes more open with an outward-increasing pitch angle (although this effect is much weaker for the density models). Finally, (iii) at large radii where Am is insignificant, the potential decays like R−1 − m with αΨ = 90°. This is simply the expected behaviour for the outer field of the inner spiral (e.g. Binney & Tremaine 2008, Eq. (2.93)) without any significant local perturbation, and it is therefore also impossible to predict via the tight-winding approximations (dashed in Fig. 7). In the transition regions, at the edges of the spiral, the potential perturbation even twists backwards, as indicated by the pitch angle of the potential exceeding 90°.

In the bottom panels of Fig. 7, I also plot the net torque per annulus. The general pattern, already seen in Fig. 4 for a spiral without radial truncation, of outward angular-momentum transport by a trailing spiral is also present for these radially tapered spirals. The approximation (27) (dashed) is not perfect, but gives a reasonable estimate for this torque, in particular, for spirals with a larger radial extent and/or smaller pitch angles. Interestingly, the total torque at −σ⟨τ⟩ < 0, i.e. the total amount of angular momentum that is transported non-locally per unit time, is comparable for the models of  and β = 1 (and the same α): For the shorter spiral pattern, the torque is limited to a smaller region, which is compensated for by a higher torque density.

and β = 1 (and the same α): For the shorter spiral pattern, the torque is limited to a smaller region, which is compensated for by a higher torque density.

6. Discussion

6.1. How good is the tight-winding (WKB) approximation?

Many of the early results on disc stability rely on the first-order tight-winding (or an equivalent) approximation (e.g. Toomre 1964; Goldreich & Lynden-Bell 1965; Julian & Toomre 1966; Toomre 1981), and various later studies have employed models for the potential of spirals based on this approximation (e.g. Contopoulos & Grosbøl 1986; Grosbøl 1993; Grosbøl & Carraro 2018; Eilers et al. 2020). Little is known about its accuracy, however. Binney & Tremaine (2008) claimed that “in many situations [it] works fairly well even for |kR| as small as unity” (i.e. pitch angles as large as 60° for m = 2), but failed to give evidence of this claim. When prompted, Scott Tremaine (private communication) pointed to the fact that it works very well for Kalnajs’ (1971) spiral models, as I have shown in Section 3.1. These models are exceptional, however, in that the density and potential have the same phase, which the (first-order) tight-winding approximation always predicts, but which does not hold in general, nor for realistic spirals.

I assessed the tight-winding approximation for the important case of a spiral perturbation with an amplitude that declines exponentially, like the unperturbed surface density itself, such that the relative strength of the spiral is constant with radius. For this case, the amplitude of the perturbing potential is fairly well approximated, in particular, if the non-standard form (10b) for k is used. However, the first-order approximation does not give a phase offset δψ between the potential and density, and hence, it fails to predict the radially increasing pitch of the potential. If the spiral perturbation has a finite radial extent, the tight-winding approximation only works within the spiral region and fails at its edges and outside.

6.2. An improved tight-winding approximation

Kalnajs (1971) provided the exact potential of logarithmic spirals whose density amplitude declines like Sm ∝ R−3/2. I generalised these models to Sm ∝ R−γ, where the exponent γ is a free parameter. These appear to be the only flat spiral models whose potential is known in closed form. For  , the phase of the potential in the equatorial plane, Ψ(R), differs from that of the density by a constant offset δψ = ψΨ − ψΣ (such that the pitch angle is still the same), which is approximately proportional to

, the phase of the potential in the equatorial plane, Ψ(R), differs from that of the density by a constant offset δψ = ψΨ − ψΣ (such that the pitch angle is still the same), which is approximately proportional to  .

.

By locally approximating an arbitrary spiral pattern by such a scale-invariant model, I obtained the second-order tight-winding approximation (24)

where α = α(R) is the local pitch angle of the density and γ = γ(R) = − dlnSm/dlnR the power-law slope of its amplitude, while σ = sign(dψΣ/dR) gives the sense of the spiral twist (for a trailing spiral  ). This novel tight-winding approximation is much better than the traditional first-order approach. In particular, it predicts the phase offset δψ and pitch of the potential with reasonable accuracy.

). This novel tight-winding approximation is much better than the traditional first-order approach. In particular, it predicts the phase offset δψ and pitch of the potential with reasonable accuracy.

6.3. The potential of typical spiral perturbations

As the surface density of spiral galaxies typically declines nearly exponentially with radius, so does the amplitude of its spiral perturbation (except at its inner and outer edges). In particular, the amplitude declines faster than a power law, and as a consequence, the phase offset δψ is no longer constant. We may estimate it from the second-order approximation (24) as

Typically, the density amplitude is shallower than Sm ∝ R−3/2 at small radii and steeper at larger radii, such that the potential trails the density at small R and leads it at large R (for a trailing spiral). For a purely exponential profile with scale radius Rd, the transition occurs at  .

.

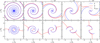

I demonstrate this in Fig. 8, which plots the crest lines (the positions of the density maxima and potential minima at each radius) for logarithmic spirals with an exponentially declining amplitude and various pitch angles (for the density). The solid red curves show the exact potential, and the dashed curves were obtained by the approximation (24), which out to R = 5Rd predicts the actual potential very well. Beyond this radius, this local approximation fails because the potential depends ever more on the inner rather than the local spiral.

|

Fig. 8. Crest lines of the density Σ (blue) and potential Ψ (red, partly concealed by those of the density) for logarithmic m = 2 spirals with a pitch angle α as indicated (top) and an exponentially declining radial density-amplitude (i.e. constant relative amplitude Am = |Σm|/Σ0), either radially unlimited (top) or with sharp inner and outer edges (bottom). I also plot (dashed) crest lines of the potential obtained via the second-order approximation (24) (to first order, the crest lines of Σ and Ψ are identical). |

The bottom panels of Fig. 8 plot the same, but for a spiral that has a non-zero (and exponentially declining) amplitude only at Rd < R < 4Rd. In most of this range, the potential closely follows the density, as predicted by the tight-winding approximations, but towards the edges and outside of the spiral range, the potential aligns itself to a constant phase and decays like Ψ ∝ Rm at R → 0 and Ψ ∝ R−m − 1 at R → ∞, as expected for the outer potential of an m-fold perturbation.

Galactic spirals tend to have an outward-decreasing pitch angle (Savchenko & Reshetnikov 2013), which implies via Eq. (38) that the phase offset does not increase as much as for α = const.

6.4. Net torque and non-local angular momentum transport

The potential of a spiral perturbation exerts a torque −∂Φ/∂ϕ per unit mass. For most stars, this torque averages out, but for stars in orbital resonance, the torque accumulates and causes significant angular-momentum changes δJϕ. These changes cause radial migration (Sellwood & Binney 2002) by (i) advective angular-momentum transport caused by local diffusion of Jϕ, as characterised by ⟨(δJϕ)2⟩, and (ii) non-local angular-momentum transport described directly by ⟨δJϕ⟩.

The sign of δJϕ depends on the relative orbital phase of the star to the spiral perturbation, which is not completely random, as the spiral pattern is made up of the very same stars. As a result, there remains a net torque at each radius, which is second order in both the spiral amplitude and pitch angle, and the sign of which depends on whether the potential of the perturbation trails (σδψ > 0) or leads (σδψ < 0) the density. For trailing spirals,  and the net torque reduces stellar angular momenta at small radii and increases them at large radii, constituting a non-local outward transport of angular momentum by gravitational torques (Zhang 1996).

and the net torque reduces stellar angular momenta at small radii and increases them at large radii, constituting a non-local outward transport of angular momentum by gravitational torques (Zhang 1996).

Thus, every trailing spiral perturbation transports angular momentum outwards, not only via local diffusion, but also by a net gravitational torque at each radius. Remarkably, this conclusion can be derived analytically (in Sections 4.1 and 4.2) without considering orbital dynamics. It implies that spirals alter the state of the disc irreversibly.

6.5. Implications of poor spiral models

The results of models using inadequate gravitational potentials for the spiral pattern are obviously compromised. Unfortunately, these shortcomings are not as uncommon as might be hoped. I give two recent examples.

With the intention to model Milky Way spirals, Eilers et al. (2020) used a gravitational potential that was meant to be the first-order tight-winding approximation (32), but deviated by a factor Rtanα/mhz with hz = 1 kpc. This, however, gives the tight-winding approximation for a density amplitude that differs from the intended exponential model by the same factor, i.e. the relative amplitude Am = |Σm|/Σ0 of the spiral perturbation increases linearly with radius. This is certainly unphysical and implies that the associated dynamical model of the non-axisymmetric stellar kinematics is inadequate Eilers et al. (2020) also neglected the gravity from the Milky Way bar, which renders their model even less adequate).

As already shown in Section 5.2.2, the models employed by Hamilton et al. (2024) also used unrealistic profiles of the density amplitude of the spiral perturbation, in particular, their model with β = ∞ in Eqs. (36), which Hamilton et al. favoured because it would resemble the model of Eilers et al. (2020). Their models  and β = 1 have more reasonable density profiles and induce much less radial heating, which agrees well with the situation that is observed for the Milky Way. The claim of Hamilton et al. that the Milky Way stellar disc is dynamically colder than expected is therefore unfounded.

and β = 1 have more reasonable density profiles and induce much less radial heating, which agrees well with the situation that is observed for the Milky Way. The claim of Hamilton et al. that the Milky Way stellar disc is dynamically colder than expected is therefore unfounded.

6.6. The vertical dimension

In this study, only flat (razor-thin) spiral perturbations have been considered, and of these, only their gravitational potential in the equatorial plane. This is often sufficient for modelling horizontal disc dynamics, at least to first order.

While the discs and their spiral perturbation of real galaxies are thin in the sense that the scale height hz is much smaller than the scale length Rd, hz can become significant compared to the radial wavelength of a spiral perturbation. In the first-order tight-winding approximation, the potential decays as e−k|z| away from z = 0, where k = m/Rsin α, and convolving this with the vertical profile ∝e−|z|/hz reduces the central potential by the factor (1 + hzk)−1. This reduction is larger at smaller R and smaller α (more tightly wound spirals), and implies that razor-thin models overestimate the gravity of spiral perturbations by ∼ (1 + hzk).

To avoid this and model the vertical extent of galactic discs and their spiral perturbations more accurately, full three-dimensional models for these perturbations and their potentials are required. These are the subject of an ongoing study.

7. Conclusions

I studied the gravitational potential of flat (razor-thin) spiral perturbations by means of an accurate numerical solution and compared them to the widely used tight-winding (or WKB) approximation. I also extended Kalnajs’ (1971) scale-invariant spirals to general power-law amplitudes |Σm|∝R−γ (Kalnajs’s spirals have  ). I studied various simple models for spiral potentials or densities, most of which were logarithmic spirals (constant pitch angle α). My main results are as follows.

). I studied various simple models for spiral potentials or densities, most of which were logarithmic spirals (constant pitch angle α). My main results are as follows.

-

For typical m = 2 spirals with exponentially declining amplitude (and hence, with constant relative amplitude), the traditional (first-order) tight-winding approximation gives ≲10% errors for pitch angles α ≲ 20°, and deteriorates beyond that.

-

Models for spiral potentials used in the literature are typically based on the first-order tight-winding approximation and inherit all its weaknesses, implying that the actually implied density deviates from the intended target, sometimes significantly so.

-

A second-order tight-winding approximation (Eq. 24), based on locally approximating the spiral perturbation by a scale-invariant spiral (rather than a plane wave), is significantly better and can predict the phase offset δψ of the potential from the density (unlike the first-order approximations, which always give δψ = 0).

-

Towards the inner or outer edge of a spiral perturbations, all tight-winding approximations fail. Beyond the edges, the gravitational potential of the spiral resembles that of a weak bar. Hence, to model these radially limited spiral perturbations, approximate techniques cannot be used, but numerical treatment is required.

-

Generally, the gravitational potential for trailing spirals trails the density at small radii and leads it at large radii, with the transition at the radius at which the density amplitude declines like R−3/2. These phase offsets result in gravitational torques that transport angular momentum outwards and change the state of the disc irreversibly. Eq. (27) gives a simple but reasonably accurate approximation for the average torque density at each radius.

-

I developed an efficient numerical method for computing the gravitational potential of spiral perturbations for arbitrary multiplicity m, phase functions ψ(R), and amplitudes Sm(R). Implementations in C++ and python are made available.

Called so in most papers and textbooks because the original development by Lin & Shu (1964) was similar to the (Jeffrey-)Wentzel-Kramers-Brillouin approximation of quantum mechanics. I abstain from using this term, because in the context of spiral perturbations some authors associate it with more than merely the approximation of the gravitational potential.

This razor-thin model can be derived from the Kuzmin (1956) disc Φ0 as (∂x − i∂y)mΦ0 and analogously for the density.

The recursion (C.4a) has two solutions, one dominant (growing) and the other recessive (shrinking) as m is incremented. The bsm are the recessive solution, while the dominant solution is obtained by replacing the associated Legendre functions of the second kind in Eq. (C.1) with those of the first kind. Any small numerical error of bs0 and bs1 corresponds to this dominant solution, which will dominate the numerical result for bsm at m ≫ 1.

Acknowledgments

I thank Howard Cohl for discussing the Laplace coefficients and for sharing Kalnajs’ letter to him, Scott Tremaine for discussing the computation of the Laplace coefficients and the tight-winding approximation, Agris Kalnajs for opening my eyes to gravitational torques by pointing out the related problem of the scale-invariant spirals with  , and the anonymous reviewer for a thorough reading and a prompt, encouraging, and helpful report.

, and the anonymous reviewer for a thorough reading and a prompt, encouraging, and helpful report.

References

- Abramowitz, M., & Stegun, I. A. 1972, Handbook of Mathematical Functions (New York: Dover Publications) [Google Scholar]

- Binney, J., & Tremaine, S. 2008, Galactic Dynamics, 2nd edn. (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Chugunov, I. V., Marchuk, A. A., & Savchenko, S. S. 2025, Galaxies, 13, 44 [Google Scholar]

- Contopoulos, G., & Grosbøl, P. 1986, A&A, 155, 11 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Eilers, A.-C., Hogg, D. W., Rix, H.-W., et al. 2020, ApJ, 900, 186 [Google Scholar]

- Goldreich, P., & Lynden-Bell, D. 1965, MNRAS, 130, 125 [Google Scholar]

- Gough, B. 2011, GNU Scientific Library: Reference Manual, 3rd edn. (Bristol: Network Theory) [Google Scholar]

- Grosbøl, P. 1993, PASP, 105, 651 [Google Scholar]

- Grosbøl, P., & Carraro, G. 2018, A&A, 619, A50 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hagihara, Y. 1972, Celestial Mechanics. Vol. 2: Perturbation Theory (Cambridge MS: MIT Press) [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, C., Modak, S., & Tremaine, S. 2024, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2411.08944] [Google Scholar]

- Huré, J. M. 2005, A&A, 434, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Julian, W. H., & Toomre, A. 1966, ApJ, 146, 810 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kalnajs, A. J. 1971, ApJ, 166, 275 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kennicutt, R. C., Jr 1981, AJ, 86, 1847 [Google Scholar]

- Kuzmin, G. G. 1956, Astron. Zh., 33, 27 [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. C., & Shu, F. H. 1964, ApJ, 140, 646 [Google Scholar]

- NIST 2024, Digital Library of Mathematical Functions, https://dlmf.nist.gov/, Release 1.2.3 of 2024-12-15 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, W. W., Jr, Huntley, J. M., & van Albada, G. D. 1979, ApJ, 233, 67 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Savchenko, S. S., & Reshetnikov, V. P. 2013, MNRAS, 436, 1074 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sellwood, J. A., & Binney, J. J. 2002, MNRAS, 336, 785 [Google Scholar]

- Sellwood, J. A., & Carlberg, R. G. 2019, MNRAS, 489, 116 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shu, F. H. 1970, ApJ, 160, 99 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toomre, A. 1964, ApJ, 139, 1217 [Google Scholar]

- Toomre, A. 1981, in Structure and Evolution of Normal Galaxies, eds. S. M. Fall, & D. Lynden-Bell, 111 [Google Scholar]

- Tremaine, S. 2023, Dynamics of Planetary Systems (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. 1996, ApJ, 457, 125 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., & Buta, R. J. 2007, AJ, 133, 2584 [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Proof of equation (5)

I begin with the observation that the potential of a razor-thin disc can always be expressed as Φ(r) = F(R, |z|), where F(r) is a smooth function satisfying ΔF = 0 for z ≥ 0 (one can construct F by setting F = Φ for z ≥ 0 and by analytic continuation for z < 0). Then Ψ(R) = F(R, 0) and Poisson’s equation at z = 0 implies

Because  also satisfies

also satisfies  , another razor-thin model can be constructed, whose potential in the plane

, another razor-thin model can be constructed, whose potential in the plane

For the surface density of the new model, Eq. (A.1) applied to  gives

gives

where the last equality follows from Eq. (A.2). Finally, when the Poisson integral (3) relating  and

and  is expressed in terms of Σ and ΔΨ using Eqs. (A.3, A.4), Eq. (5) follows. ▪

is expressed in terms of Σ and ΔΨ using Eqs. (A.3, A.4), Eq. (5) follows. ▪

Appendix B: Evaluating the Poisson integral numerically

Assume that the density has been decomposed into azimuthal Fourier components

where the Σm(R) are generally complex-valued and often given in polar form Σm(R) = Sm(R) e−imψ(R) with real-valued amplitude Sm and phase ψ. When this is inserted into the Poisson integral (3), the azimuthal Fourier component of the potential is found to be

where

are the ‘Laplace coefficients’. Their computation is detailed in Appendix C, while Fig. B.1 plots them for  . At α = 1, b1/2m has a logarithmic singularity for all m. Other important properties are

. At α = 1, b1/2m has a logarithmic singularity for all m. Other important properties are

In order to compute the derivative dΨm/dR needed for the force, the derivative of b1/2m in Eq. (B.2) could be taken via the relation (Hagihara 1972, eq. 7.4.13)

Alternatively, because Eq. (B.2) is a convolution, the derivative can be shifted onto Σm:

|

Fig. B.1. The Laplace coefficients b1/2m(α) (solid) and their asymptotes at α ≪ 1 and α ≫ 1 (dotted). |

My aim is to employ Gauß-Legendre quadrature to evaluate the integrals in (B.2) and (B.6). This requires to transform to integrals with finite boundaries and finite integrand. To avoid the infinite integration interval and shift the singularity to x = 0, I use the substitution

with some scale length a ≥ 0 (for small R it is often better to set a > 0), such that the integral (B.2) becomes

The logarithmic singularity at x = 0 can now be dealt with by the second substitution x = u3 or x = u5, such that the integrand is smooth at u = 0. Alternatively, the singularity can be treated by a technique used by Huré (2005) in a very similar context. Suppose we already know a potential-density pair  ,

,  that is an exact solution. Then

that is an exact solution. Then

Thus, the integral only computes the difference between Ψm and  times

times  . The point of this construct is that the integrand now vanishes at R′=R and the previous method without the second substitution can be used. A suitable choice for

. The point of this construct is that the integrand now vanishes at R′=R and the previous method without the second substitution can be used. A suitable choice for  and

and  is the model (35) with parameter a set such that

is the model (35) with parameter a set such that  is maximal at R′=R, giving

is maximal at R′=R, giving

Appendix C: Computing the Laplace coefficients

The Laplace coefficients bsm(α), defined in Eq. (B.3), have been studied by Laplace, Lagrange, Legendre, Euler, Cauchy, and Gauß amongst many others and are covered in every textbook on celestial mechanics (e.g. Hagihara 1972; Tremaine 2023). Because of their properties (B.4), their computation can be limited to m ≥ 0 and 0 ≤ α ≤ 1, and I assume that these conditions are satisfied. The Laplace coefficients are related to the associated Legendre functions of the second kind, Qνμ, with half-integer degree ν and integer order μ (also known as toroidal functions) via

A representation due to Lagrange (Hagihara 1972, eq. 7.1.2) is

where 2F1 is the hypergeometric function. One possibility to compute the Laplace coefficients is via the hypergeometric series (the second expression in Eq. C.2a), which gives the algorithm

where (a)n = a(a + 1)…(a + n − 1) = Γ(a + n)/Γ(a) is the (rising) Pochhammer symbol. This algorithm converges for α < 1, but only very slowly for α → 1, where bsm(α) is singular. For  , the singularity at α = 1 is logarithmic, i.e. b1/2m(α)∼ln(1 − α), and a suitable alternative expression based on Eq. (15.3.10) of Abramowitz & Stegun (1972) is

, the singularity at α = 1 is logarithmic, i.e. b1/2m(α)∼ln(1 − α), and a suitable alternative expression based on Eq. (15.3.10) of Abramowitz & Stegun (1972) is

where ϵ = 1 − α2 and ψ(z)≡Γ′(z)/Γ(z) is the digamma function. The resulting algorithm is

|

Fig. C.1. Relative error (top) and costs (bottom) of the computation of the Laplace coefficient bsm via four different methods described in the text for |

Potentially more efficient algorithms are based on the recursion relations

(Euler in Hagihara 1972, eq 7.7) to increment or decrement m and

(Hagihara 1972, eq. 7.11) to increment or decrement s. From these and some starting values for bsm and bsm + 1, the values of the Laplace coefficients for any s and m can, in theory, be computed. Possible starting values are b1/20(α) = 4K(α)/π and b1/21(α) = 4[K(α)−E(α)]/πα, where K and E are complete elliptical integrals of the first and second kind, respectively. These can be efficiently computed simultaneously from their relation to Gauß’ arithmetic-geometric mean (NIST 2024, §https://dlmf.nist.gov/19.8i), which gives the algorithm

which converges quadratically to a∞ = g∞.

Unfortunately, the recursion (C.4a) is unstable in the upwards direction3 and hence cannot be used to compute the Laplace coefficients for αm ≪ 1 with sufficient accuracy when starting from m = 0, 1. In that regime, one may either use the series expression (algorithm C.2b) or apply the recursion (C.4a) downwards (Miller’s algorithm). To this end, one starts from some value m′≫m with initial values bsm′+1 = α and bsm′ = 1, corresponding to the asymptotic behaviour bsm + 1/bsm ∼ α at small α. Next, the recursion is applied to obtain corresponding values for bsm′−1, bsm′−2, …, bs0. At small m, these are only wrong by the same overall normalisation (for the same reason that the recursion is unstable in the upwards direction), which for  can be obtained from b1/20(x) via (C.5a) and in general from the relation Tremaine (2023, problem 4.6)

can be obtained from b1/20(x) via (C.5a) and in general from the relation Tremaine (2023, problem 4.6)

The asymptotic bsm(α)∼αm for small α implies that reaching a precision ϵ requires αm′−m = ϵ or m′=m + lnϵ/lnα = m − 16/log10(α) for the usual 64-bit floating-point arithmetic. These recursive methods are particularly useful for computing several Laplace coefficients with different s or m, but even when only a single coefficient is required, as in our application, they are competitive.

This gives four different methods to compute the Laplace coefficients. For  , the only value actually required by the methods of Appendix B, I assessed them by comparison to a calculation based on the first equality in (C.2a) computed using implementations for the hypergeometric and Gamma functions from the Gnu Scientific Library (gsl, Gough 2011). At α → 1 and m ≫ 1, the gsl routines become inaccurate or even fail altogether (exit with an error), in which case I took the mean of the two least deviating values from my four methods as estimate for the correct value. Fig. C.1 plots the resulting relative errors (top) and the required CPU time (bottom) for b1/22 (left) and b1/24 (right). It appears that for small α the direct summation of the hypergeometric series (blue) is accurate and most efficient, while at larger α the upward recursion (green) is the best method.

, the only value actually required by the methods of Appendix B, I assessed them by comparison to a calculation based on the first equality in (C.2a) computed using implementations for the hypergeometric and Gamma functions from the Gnu Scientific Library (gsl, Gough 2011). At α → 1 and m ≫ 1, the gsl routines become inaccurate or even fail altogether (exit with an error), in which case I took the mean of the two least deviating values from my four methods as estimate for the correct value. Fig. C.1 plots the resulting relative errors (top) and the required CPU time (bottom) for b1/22 (left) and b1/24 (right). It appears that for small α the direct summation of the hypergeometric series (blue) is accurate and most efficient, while at larger α the upward recursion (green) is the best method.

Appendix D: The potential of the scale-invariant spirals

Following the ansatz of Appendix A, the potential can be expressed as Φ(r) = F(R, |z|) with a smooth function F(r) that satisfies

Since Σ(R) = Sm, 0(R/R0)−γ − imλeimϕ ∝ R−3/2 − iζeimϕ is scale-invariant, a natural ansatz for F(r) is a scale-invariant form, too:

with spherical coordinates (r, θ, ϕ). The function fm must be determined by the conditions (D.1), in particular (with x = cos θ)

For this to hold and f → 0 as x → 1 (so that F → 0 as z → ∞),  , where Pν μ is the associated Legendre function of the first kind. The constant C is determined by the last of the conditions (D.1), giving

, where Pν μ is the associated Legendre function of the first kind. The constant C is determined by the last of the conditions (D.1), giving  . Thus,

. Thus,

For real-valued ζ (at  ), the product

), the product  appearing in Eq. (D.3) is also real and, consequently, so is Pν m(z) for this particular case (and known as ‘conical function’).

appearing in Eq. (D.3) is also real and, consequently, so is Pν m(z) for this particular case (and known as ‘conical function’).

At z = 0, cos θ = 0 and

where I have used Eqs. 14.5.1,2 of NIST (2024) and applied Γ(z)Γ(1 − z) = π/sin πz to each Gamma factor for the last equality.

D.1. Alternative derivations of Eq. (D.5)

Eq. (D.5) is merely an extension of Kalnajs’ (1971) Eq. (12) to complex-valued ζ. While Kalnajs (1971) did not provide a derivation, he later4 sketched a proof as follows. Inserting the surface density (12) into Eq. (B.2) gives the integral expression for Km(ζ) in Eq. (E.4b). Inserting the series (C.2a) for b1/2m(e−|w|) and evaluating the integrals over w directly gives the pole expansion for the meromorphic function Km(ζ), which has simple poles at  for n ∈ ℕ. It is straightforward to show that Eq. (D.5) has the same simple poles and residues and hence the same pole expansion. Thus, according to Mittag-Leffler’s theorem, Km(ζ) can differ from the form (D.5) at most by a constant, but as both vanish at infinity, this constant is zero and the two functions identical.

for n ∈ ℕ. It is straightforward to show that Eq. (D.5) has the same simple poles and residues and hence the same pole expansion. Thus, according to Mittag-Leffler’s theorem, Km(ζ) can differ from the form (D.5) at most by a constant, but as both vanish at infinity, this constant is zero and the two functions identical.

Following a method due to Tremaine (2023, Box 6.2), yet another way to derive Eq. (D.5) constructs the scale-invariant spirals as continuous distributions of the models (35) with different scale lengths a, normalisations v02(a)∝a−γ, and phases ψ(a) = λlna, or combined, with complex-valued v02(a)∝a−3/2 − iζ:

Here, I have used ∫0∞ta − 1(1 + t)−a − bdt = B(a, b) = Γ(a)Γ(b)/Γ(a + b), which requires the real parts for a and b to be positive, which in turn implies  and constitutes a limitation of this derivation. Because R−3/2 − iζ = R−γ e−imλlnR, Σ(R) in Eq. (D.6) is proportional to that of the scale-invariant models, and eliminating the same constant of proportionality between Eqs. (D.6, D.7) gives Eq. (D.5).

and constitutes a limitation of this derivation. Because R−3/2 − iζ = R−γ e−imλlnR, Σ(R) in Eq. (D.6) is proportional to that of the scale-invariant models, and eliminating the same constant of proportionality between Eqs. (D.6, D.7) gives Eq. (D.5).

D.2. Computing the Pν m

Unfortunately, standard libraries (e.g. gsl or scipy) do not currently support the computation of the Legendre functions for complex degree ν (needed for the potential shape function fm(x)), but its computation is straightforward. For integer m

(e.g. Eq. 14.3.5 of NIST 2024), which can be computed analogously to algorithm (C.2) for the computation of the Laplace coefficient.

Appendix E: The gravitational torque

When the spiral density perturbation Σ(R) = Sm(R)eim(ϕ − ψ) (as in Eq. 6a) is inserted into Eq. (B.2), its gravitational potential is obtained as

where ψ = ψ(R) and ψ′=ψ(R′). While Sm is real-valued by definition, Pm(R) is in general complex-valued (differently from our convention in Eq. 6b). Therefore (and because only the real parts of Σ(R) are Ψ(R) have meaning), the torque density is

After integrating over ϕ, only the term involving the imaginary part of Pm remains and one finds for the total torque (using Eq. E.1)

Since Rb1/2m(R/R′) = R′b1/2m(R′/R), the integrand is anti-symmetric with respect to swapping R and R′ and the integral vanishes. When Sm(R) = Sm, 0 e−γu and ψ(R) = λu with u ≡ ln(R/R0) for the scale-invariant spirals of Section 3 is inserted into Eq. (E.3) and the integration variables are changed to u and u′, it becomes

where I used  . The integrand is, of course, still anti-symmetric with respect to swapping u with u′, such that the total torque vanishes, as it should. Factorising the double integral into the product of two one-dimensional integrals by changing the inner integration variable from u′ to w = u′−u gives

. The integrand is, of course, still anti-symmetric with respect to swapping u with u′, such that the total torque vanishes, as it should. Factorising the double integral into the product of two one-dimensional integrals by changing the inner integration variable from u′ to w = u′−u gives

which is no longer zero (not even finite), except for  , for which ζ is real and the imaginary part of the integrand of the integral over w is antisymmetric and hence Im{Km(ζ)} = 0. Thus, when merely changing the order of integration from ∬du du′ to ∬dud(u′−u), the result changes. This happens because the integrand is not absolute integrable (the integral over its absolute value diverges). The situation is analogous to a series

, for which ζ is real and the imaginary part of the integrand of the integral over w is antisymmetric and hence Im{Km(ζ)} = 0. Thus, when merely changing the order of integration from ∬du du′ to ∬dud(u′−u), the result changes. This happens because the integrand is not absolute integrable (the integral over its absolute value diverges). The situation is analogous to a series  that is not absolute convergent (

that is not absolute convergent ( diverges): changing the order of summation leads to convergence to different results or even divergence. The problem arises because (i) logarithmic spirals have, for any R > 0, an infinity of turns at radii < R and at radii > R, and (ii) the integral over the amplitude of these power law models does not converge.

diverges): changing the order of summation leads to convergence to different results or even divergence. The problem arises because (i) logarithmic spirals have, for any R > 0, an infinity of turns at radii < R and at radii > R, and (ii) the integral over the amplitude of these power law models does not converge.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Assessing the accuracy of the approximation (20) for m = 2 (for m > 2 the accuracy is better). The real (imaginary) parts are even (odd) functions of |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Assessing the tight-winding (WKB) approximation for scale-invariant spirals. The relative error of the density amplitude and the error in the phase offset δψ ≡ ψΨ − ψΣ are plotted vs. pitch angle α for m = 2 and various values of the exponent γ (for these scale-invariant models, the errors are the same at each radius). Since the first-order approximations give δψapprox = 0, their error reflects the actual phase offset of the models. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Assessing the ability of the first-order (left) and our novel (right) tight-winding approximations to provide a gravitational potential for the target density (31) of a logarithmic spiral with pitch angle α and exponentially declining amplitude. From the density that is actually generated by the approximate potential, I plot the radial profiles of the relative amplitude error (top) and the errors in phase (middle) and pitch angle (bottom), which for the first-order methods are also the respective offsets between the potential and density because to first order, ψΨ = ψtarget. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Properties of a spiral with density (Eq. (31)) and its (numerically computed) potential. Radial profiles of the amplitude ratio to the first-order tight-winding approximation (Eqs. (9) and (10b)), the offsets of phase and pitch angle between the potential and density, and the torque per annulus (< 0 if angular momentum is lost for stars in a galaxy with a trailing spiral). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Properties of the (numerically computed) density that generates the potential (35a) with the phase ψ = ψR79(R) (Eq. 34) for Rsp = 1.8a (grey vertical line) and N = 5 (as used by Roberts et al. 1979) and various values for α∞ (Roberts et al. used α∞ = 20°). For α∞ = 90°, ψ = 0, and the density is given by Eq. (35b). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Assessing the model (36) used by Hamilton et al. (2024) for the same parameters as used by these authors. Plotted as function of radius from top to bottom, I show the relative perturbation strength of the forces, the relative amplitude Am = 2 of the density perturbation (assuming the unperturbed disc is maximal with scale radius related to the co-rotation radius of the spiral as Rcr = 1.5Rd), the phase offset between the potential and density, and the density pitch angle. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Similar to Fig. 6, but for the density models of Eq. (37a) with constant pitch angle α and relative perturbation density-amplitude Am(R) = AmaxBH24(R, β), i.e., the same profile as the relative perturbation force-amplitude for the model of Hamilton et al. (2024, shown in Fig. 6) for |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Crest lines of the density Σ (blue) and potential Ψ (red, partly concealed by those of the density) for logarithmic m = 2 spirals with a pitch angle α as indicated (top) and an exponentially declining radial density-amplitude (i.e. constant relative amplitude Am = |Σm|/Σ0), either radially unlimited (top) or with sharp inner and outer edges (bottom). I also plot (dashed) crest lines of the potential obtained via the second-order approximation (24) (to first order, the crest lines of Σ and Ψ are identical). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.1. The Laplace coefficients b1/2m(α) (solid) and their asymptotes at α ≪ 1 and α ≫ 1 (dotted). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. C.1. Relative error (top) and costs (bottom) of the computation of the Laplace coefficient bsm via four different methods described in the text for |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Sigma (\boldsymbol{R})&= S_{\!m}(R) \, \mathrm{e} ^{\mathrm{i} m [\phi - \psi _{\Sigma }(R)]},\end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq8.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Psi (\boldsymbol{R})&= -P_{\!m}(R) \, \mathrm{e} ^{\mathrm{i} m [\phi - \psi _{\Psi }(R)]}, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq9.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Sigma (\boldsymbol{R}) = -\frac{\mathrm{i} \sigma }{2\pi G\sqrt{R}} \frac{\partial {\sqrt{R}\Psi }}{\partial {R}} \;\times \;\left[1+ O(\sin ^2\!\alpha )\right], \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq17.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Sigma (R,\phi )&= S_{\!m,0}\, (R/R_0)^{-\gamma } \mathrm{e} ^{\mathrm{i} m[\phi -\lambda \ln (R/R_0)]}, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq18.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} K_m(\zeta )\,K_{m+1}(\zeta )&= \left[\zeta ^2+\big (m+\tfrac{1}{2}\big )^2\right]^{-1},\end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq24.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} K_m(\zeta )\,K_m(\zeta +\mathrm{i} )&= \left[\big (\zeta +\tfrac{\mathrm{i} }{2}\big )^2+m^2\right]^{-1}. \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq25.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} K_m(\zeta )&\approx \left[\zeta ^2+m^2-\tfrac{1}{4}\right]^{-1/2}, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq26.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \zeta (R)&= \mathrm{i} \left[\frac{3}{2}+\frac{R}{\Sigma }\frac{\partial {\Sigma }}{\partial {R}}\right] = m\lambda (R) - \mathrm{i} \left(\gamma (R)-\tfrac{3}{2}\right), \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq36.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{k(R)} \approx \frac{R}{\sqrt{\zeta ^2+m^2}}&= \frac{R}{m\sqrt{\lambda ^2+1}} \left[1 + \frac{\mathrm{i} \lambda \epsilon }{\sqrt{\lambda ^2+1}} + \mathcal{O} {\epsilon ^2} \right], \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq39.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Psi (\boldsymbol{R})&\approx -2\pi G \frac{\sin \alpha }{m}\left[1+\mathrm{i} \sigma \frac{\sin 2\alpha }{2m}\left(\gamma -\tfrac{3}{2}\right)\right]R\,\Sigma (\boldsymbol{R}). \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq42.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Sigma (\boldsymbol{R}) = \Sigma _{\mathrm{sp} } \mathrm{e} ^{-R/R_{\mathrm{d} }+\mathrm{i} m[\phi -\lambda \ln (R/R_0)]}, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq49.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Psi (\boldsymbol{R}) = -A_\Psi R \mathrm{e} ^{-R/R_{\mathrm{d} }+\mathrm{i} m[\phi -\lambda \ln (R/R_0)]}, \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq50.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \psi _{\mathrm{R79} }(R)\equiv \frac{\sigma }{N\tan \alpha _\infty }\ln \left[1+\left(R/R_{\mathrm{sp} }\right)^N\right] \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq55.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Psi (\boldsymbol{R})&= \frac{\eta }{m} v_0^2 \,B_{\mathrm{H24} }(R,\beta ) \, \mathrm{e} ^{\mathrm{i} m[\phi -\lambda \ln (R/R_0)]} \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq58.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \Sigma (\boldsymbol{R}) = \Sigma _{\mathrm{c} }\, A_m(R)\, \mathrm{e} ^{-R/R_{\mathrm{d} }+\mathrm{i} m[\phi -\lambda \ln (R/R_0)]}. \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq65.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \nonumber \Psi (\boldsymbol{R})&\approx -2\pi G \frac{\sin \alpha }{m}\left[1+ \mathrm{i} \sigma \frac{\sin 2\alpha }{2m}\left(\gamma -\tfrac{3}{2}\right)\right]R\,\Sigma (\boldsymbol{R}), \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq73.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \delta \psi (R)&\approx -\frac{\sigma }{m}\arctan \left[\frac{\sin 2\alpha }{2m}\left(\gamma -\tfrac{3}{2}\right)\right] \simeq -\frac{\sigma }{m^2} \alpha \left(\gamma -\tfrac{3}{2}\right). \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq75.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} \frac{\mathrm{d}b_s^m}{\mathrm{d}\alpha }&= \frac{[m+(m+2s)\alpha ^2]b_s^m(\alpha )-2[m+1-s]b_s^{m+1}(\alpha )}{\alpha (1-\alpha ^2)}. \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/10/aa55980-25/aa55980-25-eq95.gif)