| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A156 | |

| Number of page(s) | 19 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554277 | |

| Published online | 09 December 2025 | |

The role of triple evolution in the formation of LISA double white dwarfs

1

Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 1, 85748 Garching bei München, Germany

2

Radboud University, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

3

Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, Science Park 904, 1098, XH Amsterdam, The Netherlands

4

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 München, Germany

⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

26

February

2025

Accepted:

14

October

2025

Galactic double white dwarfs will be prominent gravitational wave sources for the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA). While previous studies have primarily focused on formation scenarios in which binaries form and evolve in isolation, we present the first detailed study of the role of triple stellar evolution in forming the population of LISA double white dwarfs. We used the multiple stellar evolution code (MSE) to model the stellar evolution, binary interactions, and the dynamics of triple star systems and then used a Milky Way-like galaxy from the TNG50 simulations to construct a representative sample of LISA double white dwarfs. In our simulations, about 7 × 106 Galactic double white dwarfs in the LISA frequency bandwidth originate from triple systems, whereas ∼4 × 106 are in isolated binary stars. The properties of double white dwarfs formed in triples closely resemble those formed from isolated binaries, but we also find a small number of systems, ∼𝒪(10), that reach extreme eccentricities ( > 0.9), a feature unique to the dynamical formation channels. Our population produces ∼𝒪(104) individually resolved double white dwarfs (from triple and binary channels) and an unresolved stochastic foreground below the level of the LISA instrumental noise. About 57% of the double white dwarfs from triple systems retain a bound third star when entering the LISA frequency bandwidth. However, we expect the tertiary stars to be too distant to have a detectable imprint in the gravitational wave signal of the inner binary.

Key words: gravitational waves / binaries: close / stars: evolution / stars: solar-type / white dwarfs

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open Access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1. Introduction

Observations indicate that triple star systems are common across various stellar evolutionary stages, including main-sequence stars, evolved giant stars, brown dwarfs, and black holes (Eggleton & Tokovinin 2008; Moe & Di Stefano 2017; Kervella et al. 2017; Triaud et al. 2020; Lillo-Box et al. 2021; Burdge et al. 2024). In particular, white dwarfs have been found in triple systems with main-sequence stars (for a review within 20 pc, see Toonen et al. 2014), other white dwarfs (Maxted et al. 2000; Perpinyà-Vallès et al. 2019), neutron stars (Ransom et al. 2014), and brown dwarfs (Rebassa-Mansergas et al. 2022). However, the observed number of white dwarfs in triple systems remains significantly lower than theoretical predictions, possibly due to observational biases. Indeed, Shariat et al. (2023, 2025) propose that many observed local double white dwarfs could have originated from triples. For example, a recent spectroscopic study of wide double white dwarfs by Heintz et al. (2024) reveals some systems in which the more massive white dwarf companion has a shorter cooling age compared to the less massive one, which contradicts the initial-final mass relation if both stars were formed simultaneously in a non-interacting binary. One proposed explanation is that the progenitors of the double white dwarf were originally in a triple system, where the massive white dwarf was formed by the merger of two stars, resulting in a shorter cooling age. Furthermore, triples could significantly contribute to the rate of Type Ia supernovae, making a substantial contribution to the Type Ia supernova rate from isolated binary stars (Katz et al. 2011; Hamers et al. 2013; Rajamuthukumar et al. 2023).

Hierarchical triple systems are characterized by a close inner orbit and with a tertiary component in a wider orbit. When the orbits of the inner and outer stars are sufficiently inclined, the gravitational perturbation from the tertiary star can cause large-amplitude von Zeipel-Lidov-Kozai (ZLK) oscillations (von Zeipel 1909; Lidov 1962; Kozai 1962) of the inner binary eccentricity while the semi-major axis remains unchanged. This process can play a key role in the formation of close binaries. The combination of ZLK oscillations with dissipative effects such as tidal friction (Kiseleva et al. 1998; Eggleton & Kiseleva-Eggleton 2001; Fabrycky & Tremaine 2007) and gravitational wave radiation can lead to a reduction in the inner binary’s orbital semi-major axis. Thus, perturbations from the tertiary star can facilitate close-binary processes such as mass transfer, common-envelope phases, mergers, and collisions in the inner binary (Fabrycky & Tremaine 2007; Perets & Kratter 2012; Shappee & Thompson 2013; Hamers et al. 2013; Michaely & Perets 2014; Antonini et al. 2017; Toonen et al. 2020; Hamers & Thompson 2019; Stegmann et al. 2022a,b).

Gravitational waves from compact double white dwarfs (with frequencies ranging from 10−4 to 10−1 Hz) detectable with the upcoming Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) mission offer a unique way to explore these triple systems (Amaro-Seoane et al. 2023). By detecting the gravitational wave signals from double white dwarfs, LISA could uncover a population of systems formed through the triple evolution channel, which are inaccessible to electromagnetic observations. This capability has the potential to provide new insights into the formation mechanisms of double white dwarfs, their contribution to Type Ia supernovae (Iben & Tutukov 1984; Korol et al. 2024), and the broader implications for the chemical evolution of the Galaxy (Pagel 1997).

LISA is expected to detect ∼𝒪(106) of Galactic double white dwarfs as part of an unresolved confusion gravitational wave background and individually resolve around 103–104 of the “loudest” double white dwarfs (e.g., Korol et al. 2017; Lamberts et al. 2019; Wilhelm et al. 2021; Thiele et al. 2023; Li et al. 2023; Tang et al. 2024). While previous studies have focused on double white dwarfs formed from the evolution of isolated binary stars, increasing evidence suggests that hierarchical triple systems, in which a close inner binary is orbited by a distant tertiary companion, may also play a significant role in the formation of double white dwarfs (Toonen et al. 2020; Heintz et al. 2024; Shariat et al. 2025).

There is mounting observational evidence that stars often form with bound companions, with a binary fraction of 30% and a triple fraction of 10% for F- and G-type stars (i.e., with masses ∼1 M⊙, Eggleton & Tokovinin (2008), Raghavan et al. (2010), Tokovinin (2014), Moe & Di Stefano (2017), Offner et al. (2023). Moreover, the inner binaries in triple systems tend to be in closer orbits than the binaries found in isolated systems, which increases the probability for some binary interactions (Toonen et al. 2020). In this paper, we show that triple systems offer a greater number of evolutionary pathways for forming short-period inner binaries compared to isolated binary systems. Approximately 10% of white dwarfs are found in binary systems where both components are white dwarfs (i.e., double white dwarfs; Maxted & Marsh 1999; Maoz et al. 2018; Napiwotzki et al. 2020).

Previous studies have explored the potential for detecting tertiary companions in LISA data (e.g., Seto 2008; Robson et al. 2018; Tamanini & Danielski 2019). Similar to electromagnetic observations, the motion of the double white dwarf around the center of mass of the triple system modulates the gravitational wave frequency through the Doppler effect. This modulation produces a periodic shift, causing the observed frequency to oscillate around the intrinsic frequency of the inner binary. Recent studies have focused on leveraging this effect to detect substellar mass tertiaries, such as exoplanets and brown dwarfs (Tamanini & Danielski 2019; Danielski et al. 2019; Kang et al. 2021; Katz et al. 2022). Thus, previous studies have primarily focused on either the isolated binary population of double white dwarfs or the possibility of detecting a third star. Our work is the first evolutionary population synthesis study of Galactic double white dwarfs resulting from triple evolution. In addition, our study assesses the impact of the triple evolution channel to the LISA’s astrophysical noise background, thereby influencing the ρ of all other gravitational wave sources.

We aim to quantify the contribution of the triples to the population of double white dwarfs detectable by LISA. We combine population synthesis models using the MSE code (Hamers et al. 2021) with cosmological simulations from the TNG50 project (Nelson et al. 2019; Pillepich et al. 2019) to construct a representative model of the Galactic double white dwarf population. Our study addresses two critical questions: 1) What fraction of double white dwarfs detectable by LISA originates from the triple evolution channel? 2) Can LISA detect the dynamical effects of the third star in these triple systems?

The paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2 we explain our methodology. In Sect. 3 we describe the evolutionary pathways of triples that lead to the formation of LISA double white dwarfs. We detail the population properties of LISA double white dwarfs from isolated binaries and triples in Sect. 4, investigating prospects for direct detection of the third star in Sect. 4.4. Finally, we discuss the results in Sect. 5 and summarize our findings in Sect. 6.

2. Methods

All simulations were performed using the publicly available population synthesis code MSE1 (Hamers et al. 2021). Our set of simulations of hierarchical triples consists of a main run with a choice of default parameters and three model-variant runs. In each simulated data set, we evolve the triples from the start of the zero-age main-sequence until a maximum integration time tmax = 14 Gyr. The main triple data set consists of 105 systems, where we adopt a common envelope efficiency parameter αCE = 1, and all three stars are assumed to have formed at solar metallicity Z = Z⊙ = 0.02. This initial population results in 3 × 103 LISA double white dwarfs, with a ∼2% Poisson uncertainty in this number. In each of the three model-variant runs, we simulate 104 systems and either vary the common envelope efficiency parameter as αCE = 0.1 and 10 or change the metallicity of the stars to subsolar Z = 0.1 Z⊙. The effects of the chosen parameters are discussed in Sect. 5. In addition to the triple runs, we simulate a population of 105 isolated binaries to compare the impact of tertiary companions. Additionally, we model the inner binaries of all triples without their tertiary stars to assess their influence on the resulting LISA double white dwarf population. We expect that the isolated binary population differs significantly from the inner binary population of triples (Rajamuthukumar et al. 2023). The primary distinction is that the inner binaries have much more compact semi-major axes due to the dynamical stability constraints imposed by the tertiary star.

This section details the physics of the single, binary, and triple evolution incorporated into MSE, and outlines our initial distributions for the stellar populations. Additionally, we provide an overview of the Milky Way-like galaxy selected from the cosmological simulation TNG50. This Milky Way-like galaxy are then used to seed double white dwarfs in the galaxy. The methodology for constructing the Galactic double white dwarf population from triples is also explained here, while further details on building the Galactic double white dwarf population from isolated binaries are provided in the appendix.

2.1. Multiple stellar evolution code

We used the population synthesis approach using the code MSE to model the stellar evolution, binary interactions (tides, mass transfer), dynamical perturbations from higher-order companions in multiple systems, and flybys from ambient stars. MSE is aC/C++ code with a Python interface that can handle any number of stars as long as they start in a hierarchical arrangement. MSE uses a hybrid approach that switches between the secular approximation for dynamically stable orbits (that satisfy the criterion of Mardling & Aarseth 2001) and direct N-body integration using MSTAR (Rantala et al. 2020) for dynamically unstable orbits. Throughout the evolution post-Newtonian terms are included to 2.5 order in the secular approximation and to 3.5 order for the direct N-body integration.

To follow the evolution of single stars, MSE relies on the fitting formulae from Tout et al. (1996), Hurley et al. (2000), while binary interactions such as tides, wind mass transfer, stable mass transfer episodes, and common envelope (CE) evolutions are computed using modified prescriptions of Hurley et al. (2002). We briefly explain the physical handling of these key processes below. For more detailed explanations see Hamers et al. (2021).

Stable mass transfer: In MSE, mass transfer stability is determined either by the critical mass ratio criterion or by comparing mass transfer and dynamical timescales. The critical mass ratio depends on the donor’s stellar type (Hamers et al. 2021). We assume fully conservative mass transfer (βMT = 1), meaning no mass is lost from the system. While MSE generally follows Hurley et al. (2002) for binary interactions, it differs in treating mass transfer in eccentric orbits. Hurley et al. (2002) assumes tides are always efficient in circularizing the orbit. However, in triple systems, the eccentricities are excited secularly. We follow the analytical model from Hamers & Dosopoulou (2019) to model mass transfer at periastron in eccentric orbits

Common envelope evolution: Unstable mass transfer/CE evolution in MSE follows the αCE prescription (Paczynski 1976; van den Heuvel et al. 1976; Livio & Soker 1988; Iben & Livio 1993; Hurley et al. 2002). The code solves for orbital energies before and after the CE phase, parameterizing the envelope ejection efficiency by αCE and adopting a binding energy factor λ for each donor star taken from fits described in Claeys et al. (2014), assuming all the ionization energy stored in each envelope is useful in unbinding that envelope. For the main runs, we adopt αCE = 1. The post-CE semi-major axis is determined from the corresponding orbital energy. The timescale of mass ejection from a CE in the inner binary is relevant for the evolution of the outer orbit, and we assume that ejected common-envelope material leaves the system in a timescale of 103 yr.

Merger or collision: A “failed” CE can result in the merger of two stars. This occurs if the post-CE semi-major axis is too small for either star to avoid Roche lobe overflow. Beyond post-CE mergers, MSE also accounts for physical collisions when the sum of the stellar radii exceeds the semi-major axis or when a periapsis collision occurs in an eccentric orbit. The properties of the merger remnant are assigned following Hurley et al. (2002).

Contact evolution: If both stars simultaneously fill their Roche lobes, MSE assumes a CE phase if both are giant stars. Otherwise, a merger is assumed.

Triple common envelope (TCE) evolution: Mass transfer from a third star onto the inner binary can lead to a TCE. If CE conditions are met for the third star, MSE employs “circumstellar triple CE evolution”, allowing the third star to fill its Roche lobe around the inner binary and undergo unstable mass transfer. This follows a similar approach to the prescription proposed by Comerford & Izzard (2020). The final outer semi-major axis is estimated using an αCE prescription, assuming the inner binary remains intact and does not change. However, CE modeling is uncertain (see Ivanova et al. 2013 for a review), and TCE evolution is even more so, requiring cautious interpretation of results. For hydrodynamical simulations of triple CE outcomes, see, for example, Glanz & Perets (2020).

Flybys: MSE also includes the gravitational perturbations from stellar flybys in the vicinity of the system using the impulsive approximation. The flyby mass is sampled from a Kroupa initial mass function (Kroupa 2001), and encounters are randomly sampled within an encounter sphere of radius Renc = 105 au with velocities drawn from a Maxwellian velocity distribution with dispersion σ⋆ = 30 km s−1. The number density of flybys accounts for the low-density environments, assuming  . These flybys become significant for the evolution of the system if the semi-major axis of the outer orbit exceeds about 103 au (Jiang & Tremaine 2010; Grishin & Perets 2022; Stegmann et al. 2024).

. These flybys become significant for the evolution of the system if the semi-major axis of the outer orbit exceeds about 103 au (Jiang & Tremaine 2010; Grishin & Perets 2022; Stegmann et al. 2024).

2.2. Initial conditions

Here, we describe the initial distribution of our synthetic population of stars. We denote the masses of the inner binary components as m1 and m2, where m1 ≥ m2, and the mass of the tertiary companion as m3. Semi-major axes are denoted as a1 for the inner binary and a2 for the outer binary. Orbital eccentricities are denoted as e1 and e2, respectively. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the parameters of the initial triple population.

|

Fig. 1. Initial parameter distributions. The left panel shows the mass distributions (mi), where m1 and m2 denote the masses of the inner binary components, and m3 represents the mass of the tertiary. The middle panel displays the semi-major axis distributions(ai) for the inner (a1) and outer (a2) orbits, respectively. The right panel illustrates the eccentricity distributions(ei) of the inner (e1) and outer (e2) orbits, respectively. (See Sect. 2.2 for more details). |

We draw the primary mass m1 from a Kroupa initial mass function (Kroupa 2001) between 1 and 8 M⊙. Furthermore, we follow functions from Moe & Di Stefano 2017 to sample the orbital period (0.2 ≤ log(T1/days)≤8) and secondary mass (0.08 M⊙ ≤ m2 ≤ m1) of the inner binary, and calculate the semi-major axis a1 from Kepler’s law. Similarly, the orbital period of the outer binary also follows Moe & Di Stefano 2017, where we assume that the inner binary is represented as a single star with a mass of m1 + m2. We allowed the tertiary mass, m3, to be more massive than the total mass of the inner binary in certain cases, and an extrapolated mass ratio distribution from Moe & Di Stefano 2017 is used to sample m3. In addition, we sample the eccentricities of the inner (e1) and outer (e2) orbits from Moe & Di Stefano 2017 and randomly sample the spatial orientations of the inner and outer orbital frames from isotropic distributions.

We rejected any star whose radius exceeds the Roche-lobe radius on the zero-age main-sequence (Eggleton 1983) and reject any system which would be dynamically unstable (Vynatheya et al. 2022) at the start of the simulation. Any Roche lobe overflow or dynamical instabilities are modeled using prescriptions in MSE during the evolution (see Sect. 2.1 for more details).

2.3. Construction of Galactic double white dwarf population

We used a Milky Way-like galaxy from the large-scale cosmological magneto-hydrodynamical simulations TNG50 (Nelson et al. 2019; Pillepich et al. 2019). With a comoving volume of (50 Mpc)3 the TNG50 simulation box contains about 100 Milky Way-like galaxies with a total mass of 1014 M⊙. To select a suitable Milky Way-like galaxy, we randomly chose one of the six halos with a total mass 1–2 × 1012 M⊙ and whose central galaxy has a stellar mass 5–7 × 1010 M⊙. Additionally, we examined the galaxy’s stellar projection to confirm disk dominance. The mass of the selected galaxy (Galaxy ID = 476266) is ∼5 × 1010 M⊙, which is consistent with our Milky Way galaxy (e.g. Bland-Hawthorn & Gerhard 2016). We extracted the present-day properties such as age, stellar mass, and 3D position of the star particles. We placed our observer at a randomly assigned Sun-like position in the disk, 8.2 kpc from the Galactic center. We then measured the distances to all LISA-detectable double white dwarfs from each star particle to this location. We combined these Galactic properties with the simulated triples to construct a representative Galactic double white dwarf population as follows.

From a population of 105 simulated triple systems generated with MSE, we select only those that evolve into double white dwarf binaries emitting gravitational waves within the LISA sensitivity band (10−4, Hz–0.1, Hz) at some point in their evolution. We use this subset to reconstruct the Galactic LISA DWD population by assigning systems to star particles in a Milky Way–like galaxy from the TNG50 simulation. Each star particle represents a population of stars spanning a range of masses, with an average mass of ∼105 M⊙. By populating each particle with our simulated systems, we imprint our assumed initial conditions (Sect. 2.2) and multiplicity fractions onto the TNG50 galaxy. The number of DWDs assigned to each star particle is obtained by scaling the total number of systems in the MSE sample, NDWD, MSE, by the particle’s stellar mass, M⋆, at redshift z = 0:

For each star particle, we then randomly sample NDWD, ⋆ binaries from our subset. To ensure consistency in formation history, we only retain systems whose formation times precede the particle’s age. For such systems, we account for gravitational wave radiation reaction between their formation and the particle’s age. Evolving every binary fully within MSE would be computationally prohibitive, so we adopt a hybrid approach. For circular binaries, the tertiary companion has no appreciable effect once the system enters the LISA band. These binaries are therefore evolved analytically forward in time, using the gravitational wave emission formula of Peters (1964), until they reach the age of the host particle. In contrast, eccentric binaries (much rarer but significantly influenced by the tertiary) are included only if their simulated formation times lie within ±100 000 years of the particle’s age (a choice set mainly by computational constraints; see Sect. 4.1.2).

The total stellar mass of the simulated population is given by

where Nt, in range = 105 is the number of simulated triple systems with MSE, ft, in range is the fraction of triples in the mass range (1 M⊙ − 8 M⊙) relative to a wider mass range of stars (0.08 M⊙ − 100 M⊙). We estimate ft, in range numerically and find it to be ft, in range = 0.16. Triple fraction ft = 0.2, binary fraction fb = 0.3, and single star fraction 1 − ft − fb = 0.5 represent the fractions of triple, binary, and single systems in a full stellar population (Moe & Di Stefano 2017). We assumed a more optimistic triple fraction than currently estimated from observations to account for the incompleteness. However, our results can be rescaled for practically any assumed triple fraction. The parameters  ,

,  , and

, and  denote the numerically computed average masses of triple, binary, and single systems, respectively. The first term of Eq. (2) represents the total contribution to the stellar mass from triple systems, scaled by their fraction in the population and their average mass. The second term accounts for the contribution from binary systems and the third term represents the mass contribution from single stars. The multiplicative term Nt, in range/(ft, in range ⋅ ft) re-scales the number of simulated triples in the simulated mass range (1–8 M⊙) to the total number of stellar systems in the full mass range (0.08–100 M⊙), accounting for the fraction of triples in the full population (ft) and their relative contribution to the restricted range (ft, in range).

denote the numerically computed average masses of triple, binary, and single systems, respectively. The first term of Eq. (2) represents the total contribution to the stellar mass from triple systems, scaled by their fraction in the population and their average mass. The second term accounts for the contribution from binary systems and the third term represents the mass contribution from single stars. The multiplicative term Nt, in range/(ft, in range ⋅ ft) re-scales the number of simulated triples in the simulated mass range (1–8 M⊙) to the total number of stellar systems in the full mass range (0.08–100 M⊙), accounting for the fraction of triples in the full population (ft) and their relative contribution to the restricted range (ft, in range).

Using Eq. (1), we seed the number NDWD,⋆ of LISA-detectable double white dwarfs corresponding to each star particle and randomly select them from our simulated sample (for NDWD, ⋆ > NDWD, MSE a star particle contains some sampled double white dwarfs more than once). Additionally, we assume that all double white dwarfs are located at a star particle’s center of mass.

3. Key processes that shape the triple evolutionary pathways

In this section we present a brief overview of the five key processes characteristic of triple evolution that shape the evolutionary pathways leading to the formation of LISA double white dwarfs:

-

Induced mass transfer: The perturbation from the tertiary star triggers mass transfer in the inner binary, altering its timing or evolutionary phase compared to an isolated binary. This process ultimately leads to the formation of a short-period LISA double white dwarf.

-

Outer binary channel: The inner binary stars merge and form a new rejuvenated star which then evolves with the tertiary star to become a LISA double white dwarf.

-

Ejected tertiary: The tertiary star aids the formation of the inner double white dwarf but becomes unbound before it enters the LISA frequency bandwidth.

-

Triple common envelope: When the tertiary star overflows its Roche lobe, mass transfer onto the inner binary initiates a triple common envelope phase, which further drives the formation of a LISA double white dwarf.

-

Inner binary channel: The tertiary companion remains bound to the inner binary throughout its evolution but is too distant to significantly affect the formation of a double white dwarf; this channel is effectively that of the isolated binary channel.

We show a schematic diagram for primary processes that drive evolutionary pathways leading to LISA double white dwarfs from triples in Fig. 2. In the following subsections, we discuss these processes in greater depth with detailed examples. All uncertainties presented below are estimated by scaling up the fractional Poisson error from the intrinsic population evolved with MSE. Figure 3 shows that the processes are not mutually exclusive. For instance, about 4.8% of Galactic LISA double white dwarfs from triples undergo a TCE phase and induced mass transfer, leading to a merger in the inner binary. Hence, the relative percentages quoted below do not add up to 100%.

|

Fig. 2. Diagram of possible key processes that drive the evolutionary phases of a triple evolution leading to the formation of a double white dwarf in the LISA frequency bandwidth. The diagram showcases key stages, including mass transfer, common envelope phases, ZLK oscillations that enhance eccentricity, and eventual binary evolution. The tertiary star plays a critical role in shaping the inner binary’s dynamics, either by inducing orbital changes or facilitating interactions that lead to the formation of the LISA double white dwarf. The circles represent the index of the star, with blue, green, and red indicating the primary, secondary, and tertiary stars, respectively. The filling inside each circle represents the star’s evolutionary phase: purple for the main-sequence and white for a white dwarf. A dashed arrow denotes a distant tertiary star that is too far to significantly influence the inner binary. A multi-colored circle represents a post-merger star, with the two colors signifying the components that have merged. |

|

Fig. 3. Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of the different evolutionary processes. Among the five processes, the inner binary channel is the only one that does not require assistance from the tertiary star to produce a LISA double white dwarf. In contrast, the other four processes rely on the tertiary star to bring the system into the LISA frequency bandwidth. These processes are not mutually exclusive and exhibit significant overlap. |

3.1. Induced mass transfer

When comparing the triple runs to the inner binary runs (where the inner binary from the same triple population evolves without the tertiary star; see Sect. 2). We find that approximately  of the Galactic LISA double white dwarfs undergo a mass transfer episode solely induced by the influence of a third star. These inner binaries would not have interacted over a Hubble time without the presence of the tertiary star. About

of the Galactic LISA double white dwarfs undergo a mass transfer episode solely induced by the influence of a third star. These inner binaries would not have interacted over a Hubble time without the presence of the tertiary star. About  of Galactic LISA double white dwarfs initiate mass transfer at a different time due to the influence of a tertiary star. Thus, a total of

of Galactic LISA double white dwarfs initiate mass transfer at a different time due to the influence of a tertiary star. Thus, a total of  of systems experience induced mass transfer (see Fig. 3). The mass transfer is induced due to the combined effect of dynamical stability constraints and dynamical interactions resulting from the third star. It is not trivial to quantify the precise influence of the third star. This mass transfer is often found to have occurred at various evolutionary stages well before the formation of double white dwarfs. In contrast, the corresponding isolated binaries would either not undergo mass transfer or interact at a different time. This timing difference for the onset of mass transfer is crucial for driving the merger in the inner binary or forming a short-period inner binary that can enter the LISA frequency bandwidth within Hubble time (see the example below for more details). Also, we note that only a negligible fraction (∼10−6) of systems undergo stable mass transfer without eventually becoming unstable.

of systems experience induced mass transfer (see Fig. 3). The mass transfer is induced due to the combined effect of dynamical stability constraints and dynamical interactions resulting from the third star. It is not trivial to quantify the precise influence of the third star. This mass transfer is often found to have occurred at various evolutionary stages well before the formation of double white dwarfs. In contrast, the corresponding isolated binaries would either not undergo mass transfer or interact at a different time. This timing difference for the onset of mass transfer is crucial for driving the merger in the inner binary or forming a short-period inner binary that can enter the LISA frequency bandwidth within Hubble time (see the example below for more details). Also, we note that only a negligible fraction (∼10−6) of systems undergo stable mass transfer without eventually becoming unstable.

As examples we show the evolution of a triple system and the inner binary without the tertiary star in Fig. 4. The triple system starts with m1 = 1.61 M⊙, m2 = 1.28 M⊙, and m3 = 1.16 M⊙ as the tertiary star. The inner binary is initially eccentric, with an eccentricity e1 = 0.18 and a semi-major axis a1 = 42.6 au, while the tertiary orbit is much wider, with a semi-major axis of a2 ≈ 2980 au and an eccentricity of e2 = 0.26. The initial mutual inclination between the inner and outer orbits is 99°. Without the tertiary star the system evolves as an isolated binary. The large initial semi-major axis allows the binary components to evolve into white dwarfs without a mass transfer episode. During the course of evolution of the binary mass loss due to winds further widens the system, as shown in Fig. 5. The system continues to lose orbital energy via gravitational wave radiation but remains too wide (a ≈ 32.1 au) to enter the LISA frequency bandwidth within a Hubble time. However, with the third star present, the system undergoes significant orbital shrinkage of the inner binary during its evolution and ultimately enters the LISA frequency band. At around 2.2 Gyr, the primary star of the inner binary becomes a red giant with a convective envelope. The ZLK effect, combined with tidal friction (Fabrycky & Tremaine 2007), shrinks the inner binary’s orbit from a1 ≈ 42.6 au to 1 au. This shortening allows the primary star to fill its Roche lobe and initiate mass transfer to its companion. The mass transfer becomes unstable due to the high mass ratio and the system enters a CE phase, which further reduces the inner binary’s orbit to 0.1 au. This results in a 0.41 M⊙ white dwarf and a 1.28 M⊙ main-sequence star. Later, at around 5 Gyr, the main-sequence companion evolves to an AGB star, eventually leading to a second CE phase. This produces a short-period double white dwarf with component masses of 0.41 M⊙ and 0.23 M⊙, which enters the LISA frequency bandwidth after a few million years. Thus, in this example, the binary would not be to become a LISA source without the tertiary.

|

Fig. 4. Comparison of the evolution of a triple system with and without a tertiary star. Panels (a) and (b) illustrate the evolution of the inner binary with and without the third star respectively. In the system with the tertiary star, mass transfer is induced by perturbations from the third star, allowing the system to eventually enter the LISA frequency bandwidth. When evolved without a tertiary star the binary components remain too far apart to interact. Such a system does not enter the LISA frequency bandwidth. The legends are similar to those in Fig. 2. In addition, the yellow filling represents a star in the Asymptotic giant branch phase. |

|

Fig. 5. Comparative evolution of the properties of the inner binary of the triple with and without a third star. The three panels, from top to bottom, display the zoomed-in evolution of key parameters of the two stars: eccentricity, semi-major axis, and radius. In the case of the triple system, the inner binary experiences unstable mass transfer, causing it to shrink further and eventually enter the LISA band. Meanwhile, the inner binary when evolved without a tertiary star undergoes mass loss due to winds, resulting in an increase in its semi-major axis and a widening of the orbit. Here a1 (triple) and e1 (triple) represent the semi-major axis and eccentricity of the inner binary evolved with a tertiary star, while a (binary) and e (binary) show the semi-major axis and eccentricity of the same inner binary evolved without the tertiary star. Additionally, r1 and r2 represent the radii of the primary and secondary stars in the inner binary, respectively. |

3.2. Outer binary channel

About  of Galactic LISA double white dwarfs originate from triples where there was a merger of the inner binary stars. We identified four scenarios which lead to mergers. First, if the inner and outer orbital planes are highly inclined with respect to each other, the perturbations from the tertiary companion shrinks the orbit of the inner binary through the combination of the ZKL effect and tides. The tightened triple system has an earlier CE episode than in an isolated binary. The CE evolution results in a merger, forming a rejuvenated star bound to the former tertiary star as a binary system. This binary can evolve into the LISA frequency bandwidth. Second, in comparison to the first, the triples start out with a short-period inner binary and a distant tertiary. Here, the binary comes into contact and merges without the aid of the tertiary star. The merged star further evolves with the tertiary star to enter the LISA frequency bandwidth. Third, a TCE can cause a merger of the inner binary stars (see Sect. 3.4 for more details). Fourth, the orbit of the inner binary can widen due to mass transfer and winds, making the entire system dynamically unstable which eventually leads a chaotic evolution of the orbits and the merger of the inner binary stars.

of Galactic LISA double white dwarfs originate from triples where there was a merger of the inner binary stars. We identified four scenarios which lead to mergers. First, if the inner and outer orbital planes are highly inclined with respect to each other, the perturbations from the tertiary companion shrinks the orbit of the inner binary through the combination of the ZKL effect and tides. The tightened triple system has an earlier CE episode than in an isolated binary. The CE evolution results in a merger, forming a rejuvenated star bound to the former tertiary star as a binary system. This binary can evolve into the LISA frequency bandwidth. Second, in comparison to the first, the triples start out with a short-period inner binary and a distant tertiary. Here, the binary comes into contact and merges without the aid of the tertiary star. The merged star further evolves with the tertiary star to enter the LISA frequency bandwidth. Third, a TCE can cause a merger of the inner binary stars (see Sect. 3.4 for more details). Fourth, the orbit of the inner binary can widen due to mass transfer and winds, making the entire system dynamically unstable which eventually leads a chaotic evolution of the orbits and the merger of the inner binary stars.

Panel (a) of Fig. 6 shows an example where the inner binary merges to form a new star. The system starts with m1 = 3 M⊙ and m2 = 2.94 M⊙, and m3 = 1.89 M⊙ as the tertiary star. The inner binary is initially circular with a semi-major axis a1 = 0.3 au. The tertiary orbit is tight, with an outer semi-major axis a2 = 4.7 au and is eccentric with e2 = 0.56. The mutual inclination between the inner and outer orbits is 62°. The most massive of all three stars is in the inner binary (m1 = 3 M⊙) which, at about 370 Myr, initiates an unstable mass transfer episode onto the secondary resulting in the merger of the two stars. This merger leads to the formation of a new star with a mass mr = 5.69 M⊙. The remaining post-merger binary composed of the rejuvenated star and the tertiary companion subsequently undergoes and survives two more CE episodes: one when the rejuvenated star enters the AGB at about 390 Myr and another when the tertiary companion becomes an red giant star at about 1.4 Gyr. The second CE leads to the formation of a circular double white dwarf with a semi-major axis of 9 × 10−3 au later entering the LISA bandwidth after ∼ 1 Gyr. An isolated binary with the same properties as the inner binary of such a triple would not enter the LISA band.

|

Fig. 6. Schematic diagrams of systems that enter the LISA frequency bandwidth after following the outer binary channel and those in which the triple eject the tertiary during the course of evolution. Panel (a) depicts an example of systems following the outer binary channel. In this scenario, the inner binary merges to form a rejuvenated star, which later enters the LISA frequency bandwidth along with the tertiary star. Panel (b) illustrates an example system that initially includes a bound third star, which facilitates a common envelope phase in the inner binary but is later ejected. The inner binary subsequently enters the LISA frequency bandwidth.The legends are similar to those in Fig. 2. In addition, the yellow circle represents a star in the asymptotic giant branch phase. |

3.3. Ejected tertiary

About  of Galactic double white dwarfs from triples lost the tertiary star. The unbinding of the tertiary companion primarily occurs due to the following reasons. First, during a CE phase the inner binary’s orbit shrinks and loses angular momentum, while the prompt mass loss during the CE unbinds the outer orbit. Second, if the inner binary widens due to mass transfer or stellar winds the system becomes less hierarchical and dynamically unstable. Dynamically unstable orbits lead to chaotic evolution which may eject an object from the system. We provide a specific example of this process below.

of Galactic double white dwarfs from triples lost the tertiary star. The unbinding of the tertiary companion primarily occurs due to the following reasons. First, during a CE phase the inner binary’s orbit shrinks and loses angular momentum, while the prompt mass loss during the CE unbinds the outer orbit. Second, if the inner binary widens due to mass transfer or stellar winds the system becomes less hierarchical and dynamically unstable. Dynamically unstable orbits lead to chaotic evolution which may eject an object from the system. We provide a specific example of this process below.

Panel (b) of Fig. 6 shows an example of a system where a tertiary gets ejected after a CE in the inner binary. The system starts with m1 = 1.39 M⊙ and m2 = 1.39 M⊙ as the inner binary components and m3 = 0.31 M⊙ as the tertiary star. The inner binary is initially eccentric with an inner eccentricity e1 = 0.56 and an inner semi-major axis a1 = 50.1 au. The tertiary orbit is wide, with an outer semi-major axis a2 ≈ 1690 au and is eccentric with e2 = 0.81. The mutual inclination between the inner and outer orbits is 112°. The inner binary masses are greater than the tertiary star so they evolve on a shorter timescale. The CE occurs in the inner binary during the AGB phase after about 3.6 Gyr. The CE reduces the inner binary semi-major axis to 10−2 au and unbinds the outer tertiary. The remaining binary components evolve into a double white dwarf system. This double white dwarf binary emits gravitational waves and later enters the LISA frequency bandwidth after 1 Myr. In this example, even though the binary does not have a bound tertiary star by the time it enters the LISA frequency bandwidth, the tertiary plays a role in shrinking the binary before the CE episode.

3.4. Triple common envelope

About  of Galactic double white dwarfs from triples undergo a phase of TCE evolution before entering the LISA frequency band. We identified two possible evolutionary outcomes of a TCE event in our simulations. First, the merger of the inner binary: the inner binary may merge to form a rejuvenated star. The new star forms a binary with the third star which later enters LISA frequency bandwidth. Second, ejection of one component: One of the stars may become unbound from the system, leaving behind a binary formed by the remaining two stars. This binary may enter the LISA band. We explain one of the examples below (see Hamers et al. 2022 for a more detailed study of TCE).

of Galactic double white dwarfs from triples undergo a phase of TCE evolution before entering the LISA frequency band. We identified two possible evolutionary outcomes of a TCE event in our simulations. First, the merger of the inner binary: the inner binary may merge to form a rejuvenated star. The new star forms a binary with the third star which later enters LISA frequency bandwidth. Second, ejection of one component: One of the stars may become unbound from the system, leaving behind a binary formed by the remaining two stars. This binary may enter the LISA band. We explain one of the examples below (see Hamers et al. 2022 for a more detailed study of TCE).

Figure 7 shows an example of a TCE where the inner binary merges to form a new binary. The system starts with m1 = 1.18 M⊙, m2 = 0.54 M⊙, and a massive tertiary m3 = 5.59 M⊙. The inner binary is initially circular, with a semi-major axis a1 = 0.05 au. The tertiary orbit is compact, with an outer semi-major axis a2 = 25 au and highly eccentric with e2 = 0.94. The mutual inclination between the inner and outer orbit is 160°. Since the tertiary star is massive compared to the inner binary masses, it is the first to reach the AGB phase, in about 92 Myr. The inner binary components are still on the main-sequence.

|

Fig. 7. Schematic diagram for an example system that undergoes a TCE. In this scenario, the massive star transfers mass onto the inner binary, leading to its merger and the formation of a rejuvenated star. This rejuvenated star later enters the LISA frequency bandwidth along with the tertiary star. The legends are similar to those in Fig. 2. In addition, the yellow circle represents a star in the asymptotic giant branch phase. |

Expansion of the envelope during the AGB phase initiates Roche lobe overflow. The AGB tertiary starts transferring mass onto the inner binary. The mass transfer becomes dynamically unstable owing to a higher mass ratio. The envelope of the AGB tertiary star engulfs both components of the inner binary. The TCE evolution leads to interactions between the three stars. The inner binary merges to form a rejuvenated star which is still bound to the stripped tertiary star. The resulting binary has a large eccentricity of 0.73 and a semi-major axis of 0.2 au.

After approximately 2 Gyr, the rejuvenated star evolves into a red giant which transfers mass onto the white dwarf, initiating another CE phase. The end of this CE phase leaves a circular and compact double white dwarf in a circular orbit with a semi-major axis of ∼8 × 10−2 au. After a few million years the binary enters the LISA frequency bandwidth due to gravitational wave emission. Here, TCE plays a significant role as it leads to merging the inner binary. The binary with the post-merger rejuvenated star later enters the LISA frequency bandwidth. Hence, the tertiary star plays a vital role in the evolution of the triple to LISA frequency bandwidth.

3.5. Inner binary channel

We evolve the inner binaries of triple systems in isolation (i.e., without the influence of the third star) to quantify the impact of tertiary companions. About  of the Galactic double white dwarfs from triples in our simulations enter LISA frequency bandwidth without any notable contribution from the third star. However, the initial configurations of these binaries (particularly their shorter orbital periods) are themselves a consequence of the dynamical stability constraints imposed by the tertiary companion. Here, the inner binary undergoes phases of CE before forming a short-period double white dwarf. This double white dwarf later enters the LISA frequency bandwidth either with a wide tertiary or as a binary with an ejected tertiary (for details on ejected tertiary, see Sect. 3.3).

of the Galactic double white dwarfs from triples in our simulations enter LISA frequency bandwidth without any notable contribution from the third star. However, the initial configurations of these binaries (particularly their shorter orbital periods) are themselves a consequence of the dynamical stability constraints imposed by the tertiary companion. Here, the inner binary undergoes phases of CE before forming a short-period double white dwarf. This double white dwarf later enters the LISA frequency bandwidth either with a wide tertiary or as a binary with an ejected tertiary (for details on ejected tertiary, see Sect. 3.3).

4. LISA double white dwarfs: Isolated binary versus triple evolution

Building on the method in Sect. 2.3, where we construct the Galactic population by combining MSE with a Milky Way-like galaxy from TNG50, we obtain a total of ∼7.2 × 106 Galactic double white dwarfs originating from triples. To compare this result with the isolated binary channel, we adjust our simulation as described in Appendix A. We emphasize that the initial distribution of the isolated binary population is constructed to represent truly isolated binaries and is different from the initial properties sampled to assemble the inner binaries in triple systems (See Sect. 2.2). In the isolated binary case, we find that about ∼3.8 × 106 double white dwarfs are produced through isolated binary evolution, yielding a total of ∼1.1 × 107 Galactic double white dwarfs currently emitting gravitational waves within the LISA bandwidth. Thus, approximately 65% (∼7.2 × 106) of all Galactic double white dwarf binaries originated from triple systems as illustrated in Fig. 8. We note that the isolated binary evolution channel only yields circular binaries. In contrast, the triple channel generates a small fraction (3 × 10−6) of eccentric binaries, which we discuss below.

|

Fig. 8. Pie chart showing the fraction of eccentric and circular orbits among double white dwarfs from triple systems and isolated binary systems. While isolated binaries do not produce double white dwarfs with eccentric orbits, approximately 3 × 10−6 of LISA-detectable double white dwarfs from triple systems exhibit eccentric orbits. |

Notably, we find that among all the double white dwarfs initially in triples only about half (∼57%) retain a bound tertiary. In the remaining systems, the third star either became unbound or there was a merger of inner binary stars, reducing the system from a triple to a binary (See Sects. 3.3 and 3.2). Importantly, all double white dwarfs that retain their tertiary companion in our simulations have the tertiary in a wide orbit. We discuss the potential for detecting the presence of the tertiary companion based on LISA data in Sect. 4.4. We recall that we also generated a comparative simulation where the Galactic population only follows the isolated binary channel (i.e., entirely excluding triple channels). In this simulation we obtain a total of ∼9.4 × 106 double white dwarfs emitting at LISA frequencies. All results are summarized in Table 1.

Estimated counts.

In the following subsections we present our estimates for the number of individually resolvable sources and estimate the unresolved stochastic foreground. We discuss the source properties and white dwarf (core composition) types from triple systems then compare them with those from the isolated binary channel.

4.1. Detectability with LISA

4.1.1. Circular systems

Double white dwarfs in the LISA band are typically millions of years away from merging. They are continuous, quasi-monochromatic gravitational wave sources for LISA. Describing these signals requires a set of eight parameters, typically chosen as  (LISA Consortium Waveform Working Group et al. 2023). Here, 𝒜gw represents the gravitational wave amplitude, fgw and

(LISA Consortium Waveform Working Group et al. 2023). Here, 𝒜gw represents the gravitational wave amplitude, fgw and  denote the gravitational wave frequency and its time derivative (or chirp), (λ, β) correspond to the ecliptic longitude and latitude, respectively, ι is the (inner) binary inclination angle with respect to the line-of-sight, ψ is the gravitational wave polarization angle, and ϕ0 represents the binary’s initial phase. Our population synthesis models provide binary parameters such as component masses, orbital periods and eccentricities, sky positions, and distances. We use these to derive gravitational wave parameters as follows. As discussed above, the overwhelming majority of double white dwarfs in our simulations are circularized.

denote the gravitational wave frequency and its time derivative (or chirp), (λ, β) correspond to the ecliptic longitude and latitude, respectively, ι is the (inner) binary inclination angle with respect to the line-of-sight, ψ is the gravitational wave polarization angle, and ϕ0 represents the binary’s initial phase. Our population synthesis models provide binary parameters such as component masses, orbital periods and eccentricities, sky positions, and distances. We use these to derive gravitational wave parameters as follows. As discussed above, the overwhelming majority of double white dwarfs in our simulations are circularized.

The gravitational wave frequency of a circular binary is twice its orbital frequency (forb),

while the amplitude is given by

where G and c are the gravitational constant and speed of light respectively. The amplitude is set by the source’s distance, d, and chirp mass:

The chirp mass also sets the rate at which the frequency changes due to the gravitational radiation reaction:

Equations (3), (4), and (6) define the first three parameters of the set. The ecliptic coordinates (λ, β) are inherited from the TNG50 Milky Way-like galaxy where the binary was seeded, while the remaining three parameters are assigned randomly. Specifically, ι is sampled from a uniform distribution in cosι, and ψ and ϕ0 are sampled from flat distributions.

As the next step, we estimate the confusion noise produced by these gravitational wave sources in our mock Milky Way using the pipeline2 described in Karnesis et al. (2021), see also Timpano et al. 2006; Crowder & Cornish 2007; Nissanke et al. 2012). The pipeline approximates the so-called “global fit” analysis, which is the currently adopted approach to handling LISA’s complex data analysis (Colpi et al. 2024, see also Littenberg & Cornish 2023; Katz et al. 2024; Deng et al. 2025).

The pipeline employs a signal-to-noise (ρ) evaluation to iteratively estimate the strain amplitude spectral density resulting from the combined signals of the unresolved (i.e., low ρ) part of the input population. As a result, we also obtain a catalog of individually resolved (i.e., high ρ) binaries. For our analysis, we adopt LISA’s instrumental noise requirements as defined in the technical note by LISA Science Study Team (2018). We assume a mission duration of 4 yr and use an ρ threshold of 7 to distinguish between individually resolvable LISA sources and unresolved ones, a choice commonly adopted in detailed simulations (e.g., Crowder & Cornish 2007; Cornish & Littenberg 2007; Finch et al. 2023)

We estimate a confusion foreground from our mock population containing double white dwarf binaries from both isolated binary and triple channels to be at the level of the LISA instrument noise. We also obtain ∼1.7 × 104 sources above the ρ threshold, of which ∼6.5 × 103 come from the isolated binaries and ∼1.1 × 104 come from the triples (see Sect. 5.1 for comparison to previous works). Figure 9 shows the characteristic strain as a function of gravitational wave frequency for Galactic double white dwarf sources originating from both triples and isolated binaries. The characteristic strain is defined as the effective strain amplitude, incorporating the number of cycles a system completes during the observation time. This quantity is convenient for comparing source signals with the detector sensitivity, since the height of a system above the sensitivity curve represents its signal-to-noise ratio.

|

Fig. 9. Characteristic strain |

Our estimate of the confusion noise is lower than that presented in the LISA mission proposal (Amaro-Seoane et al. 2017) and the more recent LISA Definition Study Report (Colpi et al. 2024), which used a different population synthesis study (Nelemans et al. 2004; Korol et al. 2017). This discrepancy arises from multiple aspects of population modeling, including variations in binary evolution prescriptions, Milky Way modeling, and, importantly, the inclusion of the triple formation channel in our simulations. However, since the same systematics are applied to both our triple and isolated binary populations, their differential properties remain largely unaffected.

These factors collectively influence the total number of binaries in the LISA band and their properties. Identifying a single source of the difference is challenging, as these aspects are interrelated and nontrivially correlated. The LISA Consortium’s Astrophysics Working Group is currently investigating the differences and uncertainties in predicting the confusion foreground as part of the Ultra-Compact Binaries catalog comparison project (Valli et al. 2023, as well as Breivik et al. and Bobrick et al. in prep.). We refer the reader to those forthcoming results and provide a comparison using our test simulation, in which all LISA binaries were generated solely via the isolated binary channel.

4.1.2. Eccentric systems

Here, we focus on eccentric systems originating from the triple formation channel. These systems were excluded from the analysis above as they are estimated to be very few (and therefore do not contribute to the overall Galactic confusion signal) and because their gravitational wave signals differ from those of circular systems.

We find that approximately 3 × 10−6 of all Galactic double white dwarfs exhibit eccentric orbits. These systems result primarily from two reasons: (1) the ZLK effect excites the eccentricity of the inner binary orbit, or (2) the system becomes dynamically unstable and eventually achieves a stable configuration with high eccentricity.

In our simulations, all eccentric systems show high eccentricities (e > 0.9) and wide semi-major axis (101 − 106 au). For such orbital configurations, gravitational wave emission predominantly occurs near pericenter passage, lasting up to a few hours and producing burst-like gravitational wave signals. Since the orbital periods of these systems in our simulations are significantly longer than the mission duration (> 46 yr), the double white dwarf burst signals will not repeat within LISA’s observation window of 4 yr.

The probability to observe a gravitational wave burst from an individual system at periapsis is ∼Tobs/Torb, where Tobs is the observational time ( ∼ 4 yr) and Torb is the orbital period of the binary. Assuming Poisson binomial distribution, we estimate that LISA will detect at most one eccentric double white dwarf during its operational duration. Following Xuan et al. (2024), we estimated the frequency and strain amplitude of such a burst signal as

where rp is the periapsis distance. We found the (dimensionless) strain amplitudes of the gravitational wave emitted during the periapsis are between ∼10−24 and 10−22, i.e., below the noise curve (black stars in Fig. 9). Therefore, such a signal would not be detectable by LISA.

4.2. Population properties

In this section we describe the similarities and differences in the population properties of double white dwarfs formed from triple systems and binary systems. Figure 10 shows the distribution of population properties such as chirp mass, primary mass, eccentricity, and gravitational wave frequency. The green color corresponds to the properties of double white dwarfs from triple systems while the purple color shows the properties of double white dwarfs from binary star systems. The shaded green and purple regions represent the properties of resolvable double white dwarfs from triple and binary star systems, respectively. The resolved double white dwarf population traces the features of the total double white dwarf population. It is also interesting to note that all double white dwarfs in our mock Milky Way with fgw > 2 × 10−3 are fully resolvable by LISA. Individually resolving any double white dwarf with fgw < 2 × 10−3 is more difficult for LISA due to the higher degree of overlap in this frequency range.

|

Fig. 10. Population properties of LISA-detectable double white dwarfs from triple systems compared to isolated binaries. Triple-origin systems tend to produce more massive white dwarfs than isolated binaries. Outline (step) histograms represent the total LISA-detectable population, while filled histograms show the subset of systems individually resolvable with S/N > 7. For more on the distributions shown, refer to Sect. 4.2. Green indicates triple-origin systems, and purple indicates isolated binaries. Thin and thick vertical lines show the 68.3% confidence intervals for the full and individually resolvable populations, respectively. The vertical gray lines indicate the full range of values spanned in each bin. Confidence intervals are estimated via bootstrap resampling and reflect the sampling uncertainty arising from the stochastic seeding of the Galaxy (see Appendix B for details). |

Triple systems produce about ∼1.5 times more LISA double white dwarf systems with primary masses greater than 0.9 M⊙ and ∼3.9 times more super-Chandrasekhar mass double white dwarfs (binary white dwarfs in which total mass of both the white dwarfs combined exceeds 1.44 M⊙) than the isolated binary channel. In addition, triple systems produce ∼1.6 times more extremely low-mass white dwarfs (m < 0.25 M⊙) that enter the LISA frequency bandwidth than isolated binaries. Isolated binaries do not produce binaries with a chirp mass greater than 0.9 M⊙. In contrast, triple systems produce ∼103 binaries whose chirp mass is greater than 0.9 M⊙. There are two possible ways to form massive white dwarfs: 1) The system originates from a massive main-sequence progenitor that evolves to a massive white dwarf; 2) Two less massive progenitors merge to form a massive main-sequence progenitor that subsequently forms a massive white dwarf. In our simulations, initial massive main-sequence progenitors are rare. Hence, it is difficult to form massive white dwarfs in isolated binaries. However, in triple systems, the two less massive progenitors in the inner binary can merge to form a massive progenitor. The merged star co-evolves with the former tertiary component to form a double white dwarf with a massive component.

There is no significant difference in the frequency distribution of double white dwarf binaries formed from isolated binaries and triple systems. This is because most double white dwarfs emerge as short-period binaries after a common envelope phase, eventually emitting gravitational waves to enter the LISA band.

4.3. Different types of double white dwarfs

From the MSE single-star evolution model, helium-core white dwarfs originate from binary interactions where the progenitor loses its envelope before helium ignition, with typical masses of ≲0.45 M⊙. Carbon-Oxygen core white dwarfs form from intermediate-mass stars that exhaust helium in their cores and expel their outer layers, resulting in masses between ∼0.45 − 1.1 M⊙. Oxygen-Neon core white dwarfs arise from more massive stars that undergo carbon burning before shedding their envelopes, with typical masses of ≳1.1 M⊙.

Figure 11 shows the relative numbers of different double white dwarf (core composition) types from binary and triple systems, respectively. Our simulations produce all types of double white dwarfs in the LISA frequency bandwidth from both triple and binary star systems, including He-He, He-CO, He-ONe, CO-CO, and CO-ONe systems. He-CO systems dominate the population of double white dwarfs originating from both triples and isolated binaries. Our simulations produce ONe-ONe systems only from the triple populations, but the sampling uncertainties in this mass range are too high to draw meaningful conclusions.

|

Fig. 11. Types of LISA-detectable double white dwarfs formed from triple systems compared to isolated binaries. In our models, ONe-ONe double white dwarfs are produced exclusively in triple systems. Error bars represent a 68.3% confidence interval and are derived from bootstrap resampling and capture the statistical uncertainty introduced by the stochastic seeding of the Galaxy. (See Appendix B for details). |

4.4. Detectability of the third star

We emphasise again that approximately  of all double white dwarfs detectable by LISA will have a bound tertiary companion. The bound tertiary star can be found in various evolutionary stages, including as a main-sequence star, a giant star, or a white dwarf. In the remaining 43% of systems, the third star either became unbound or there was a merger of two stars, reducing the system from a triple to a binary (See Sect. 3.3). If the tertiary is retained, it can impart accelerations to the center of mass of the binary, leading to observable Doppler shifts in the gravitational wave signals (e.g., Seto 2008; Robson et al. 2018; Tamanini & Danielski 2019).

of all double white dwarfs detectable by LISA will have a bound tertiary companion. The bound tertiary star can be found in various evolutionary stages, including as a main-sequence star, a giant star, or a white dwarf. In the remaining 43% of systems, the third star either became unbound or there was a merger of two stars, reducing the system from a triple to a binary (See Sect. 3.3). If the tertiary is retained, it can impart accelerations to the center of mass of the binary, leading to observable Doppler shifts in the gravitational wave signals (e.g., Seto 2008; Robson et al. 2018; Tamanini & Danielski 2019).

In the context of LISA Galactic binaries in hierarchical triple systems, Robson et al. (2018) identifies three regimes, essentially governed by the ratio of the outer orbital period to the observation time: 1) When the outer period is much larger than the observation time the hierarchical orbit imparts an overall unobservable Doppler shift. 2) When the outer period is up to a factor ten larger than the observation time the influence of the companion can be detected. 3) When the outer period is shorter than or comparable to the observation time, the eccentricity and period of the hierarchical orbit can be inferred. Specifically, a tertiary companion leaves a detectable imprint in the gravitational wave signal if the outer binary period satisfies

where ρ is the signal-to-noise ratio of the binary.

In our simulations, in all systems that have retained the tertiary companion, the outer orbits are too wide to have any detectable effect within the resulting LISA gravitational wave signal. Figure 12 compares the outer orbital period T2 with the factor on the right hand side of the Eq. (9). The black line shows the limit where T2 equals the factor on the right hand side. We find that none of our surviving triple systems lie within, or close to, the detectable limit. In addition, we find no systems where Torb ≤ Tobs or Torb ≈ 10 × Tobs. The minimum outer semi-major axis across all systems is found to be approximately 21 au, which corresponds to an orbital period of around 63 yr.

|

Fig. 12. Comparison between the outer orbital period of a triple system and the factor on the right-hand side of Eq. (9). Red points represent Tlim vs. the outer orbital period T2 for all the Galactic LISA double white dwarfs with a bound third star. The black line represents the points where T2 = Tlim. No tertiary star satisfies Eq. (9) for detectability within the LISA frequency bandwidth. |

5. Discussion

We discuss our results in the context of previous works, present the uncertainties associated with our models, and describe the constraints imposed by electromagnetic observations.

5.1. Comparison to previous works

We calculated the number and population properties of LISA double white dwarfs that originated from triple systems (See Sect. 2). We also simulated LISA double white dwarfs from an isolated binary population (See Appendix A) to compare with triple populations. Our isolated binary simulation predicts ≈104 individually resolvable double white dwarfs in the LISA frequency bandwidth, which agrees with previous works, including Nelemans et al. (2004), Ruiter et al. (2010), Yu & Jeffery (2010), Korol et al. (2017), Lamberts et al. (2019), Li et al. (2023), Thiele et al. (2023), Tang et al. (2024). In total, our models predict ∼1.1 × 107 double white dwarf sources that emit gravitational waves in the LISA frequency bandwidth but have too low ρ to be individually detected by LISA.

In particular, Korol et al. (2017) used the binary population model of Toonen et al. (2012) based on the SeBa binary population synthesis code (Portegies Zwart & Verbunt 1996) and an analytic Galactic potential and star formation history to estimate the number of Galactic double white dwarfs. They predict ∼2.6 × 107 LISA double white dwarfs as foreground noise and ∼2.5 × 104 as individually resolvable LISA double dwarf sources. Korol et al. (2022) performed a data-driven analysis using existing observational double white dwarf data and also estimated a LISA double white dwarf population of ∼2.6 × 107 as foreground noise and ∼6.0 × 104 as individually resolvable LISA double dwarf sources. Using the BSE code (i.e., similar to our isolated binary evolution channel but with different underlying assumptions) combined with the Fire cosmological simulation, Lamberts et al. (2019) constructed the Galactic LISA double white dwarf population and estimated ∼6.2 × 107 double white dwarf sources as foreground noise and ∼1.2 × 104 as individually resolvable LISA double dwarf sources. Further, Li et al. (2023) also used the BSE code but with a mass transfer stability criterion by adopting critical mass ratios from the adiabatic mass loss model by Ge et al. (2010, 2015, 2020), and estimated a foreground LISA double white dwarf population size of ∼5.0 × 107 and about 4.0 × 104 individually resolvable double white dwarfs. Our results are broadly consistent with previous studies in terms of the number of resolved binaries, but we estimate comparatively fewer double white dwarf sources emitting gravitational waves in the LISA frequency band (see Sect. 4.1.1 for details). This discrepancy may arise from multiple factors, including the use of different population synthesis codes, varying assumptions underlying binary evolution, and different approaches to modeling the Galaxy. Most importantly, previous studies model isolated binary evolution only, ignoring triples.

When comparing our isolated binary evolution results (with triple fraction set to zero; see Table 1) to previous studies, several factors can contribute to differences in LISA predictions. For instance, assuming a different total stellar mass for the Milky Way would linearly scale our results (See Eq. (2)). As shown by Keim et al. (2023), the underlying star formation history also plays a role (see also Yu & Jeffery 2010). However, the most likely primary source of differences is the modeling of stellar and binary evolution. This was recently demonstrated by van Zeist et al. (2024), who investigated the gravitational wave population of the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds as a case study using the BPASS (Eldridge et al. 2017) and SeBa codes. They specifically attributed variations in the predicted number of LISA double white dwarfs to differences in the treatment of CE evolution and the stability of mass transfer. Indeed, even studies using the same population synthesis code report significant differences in LISA predictions when these processes are modeled differently (e.g., Korol et al. 2017; Li et al. 2023). As mentioned before, quantifying the impact of all these factors on LISA predictions is a large collaborative effort within the LISA Consortium’s Astrophysics Working Group. We refer the reader to those forthcoming results.

5.2. Uncertainties in our modeling

In our normalization calculations, we assume constant multiplicity fractions 0.2, 0.3, and 0.5 for stars in triple, binary, and single systems respectively. The multiplicity fractions play a crucial role in the mass normalization and, hence, the total number of LISA double dwarfs. All previous works assume a zero triple fraction. To compare our results with previous works, we have also calculated the number of LISA double dwarfs with a 0.5 binary fraction and zero triple fraction. We found ∼9 × 106 systems, showing consistency with previous studies in scale. For the same isolated binary population, assuming a 0.2 triple fraction, we only obtain ∼3.8 × 106 systems, half as many. This highlights the sensitivity of the results to the assumed multiplicity fraction.

We adopt the default critical mass-ratio criteria in MSE to model the stability of mass transfer. Studies investigating alternative stability criteria find that mass transfer tends to be more stable than we have assumed, suggesting that fewer systems undergo a common envelope phase (Tauris & den Heuvel 2000; Podsiadlowski et al. 2002; Ge et al. 2010; Woods et al. 2012; Passy et al. 2012; Ge et al. 2015, 2020; Temmink et al. 2023). This affects the formation of double white dwarfs (Woods et al. 2012), particularly in the LISA band (Li et al. 2023; van Zeist et al. 2024). Additionally, we assume that the orbit circularizes following the common envelope phase. However, there is ongoing debate about whether residual eccentricity may persist at the end of the common envelope evolution. The modeling of unstable mass transfer leading to a common envelope phase follows the approximate α-λ formalism. We investigated the effect of the common-envelope efficiency parameter, αCE, on our results. As discussed in Ivanova et al. (2013), the commonly used parameter αCE only describes an energetic “efficiency” under restrictive assumptions which are not known to be true. Contributions from sources of energy not included in the standard α-λ formalism may perhaps allow for an effective αCE > 1. We would nonetheless be surprised if our model with effective αCE = 10 is a good description of reality, but include that model to explore how sensitive our predictions are to extremely different outcomes of common-envelope phases.

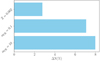

For lower (αCE = 0.1) and higher efficiency parameters (αCE = 10), our simulations yield approximately 7.5 × 106 and 7.6 × 106 LISA double white dwarfs, respectively (see Fig. 13). For a lower value of the common envelope efficiency, the common envelope phase is more effective at shrinking the orbit. Consequently, these systems enter the LISA frequency bandwidth within a Hubble time. In contrast, for the default value (αCE = 1), the common envelope phase results in a wider orbital period. However, for a high common envelope efficiency parameter, there is an increase in the number of LISA-detectable double white dwarf binaries. This is because the more efficient common envelope phase is less likely to merge binaries that would otherwise have merged for αCE = 1.

|

Fig. 13. Fractional difference of LISA-detectable double white dwarfs from models with varying common envelope efficiency, αCE, and subsolar metallicity relative to the default values (αCE = 1, Z = 0.02). The number of double white dwarfs varies by up to 8% when the common envelope parameters are modified. |

We assume that all progenitors of the Galactic LISA double white dwarfs are formed with solar metallicity. About ∼2% of the star particles in the selected Milky Way model have subsolar metallicity. However, our Galaxy encompasses a larger range of metallicities. We also explore the impact of subsolar metallicity by constructing the galaxy using the procedure described in Sect. 2.3 but with an initial metallicity of Z = 0.002. It results in approximately ∼7.5 × 106 LISA double white dwarfs, an increase of ∼0.3 × 106 compared to those with solar metallicity. Stars with lower metallicity evolve faster. For example, a 0.91 M⊙ star evolves into a white dwarf within a Hubble time at subsolar metallicity, whereas it does not at solar metallicity. This increase in the number of low-mass stars that evolve into white dwarfs significantly contributes to the population of LISA-detectable double white dwarfs.

The ZLK effect induces eccentric oscillations in the inner binary, increasing the possibility of mass transfer at periapsis or eccentric mass transfer. The MSE model treats eccentric mass transfer using an approximate prescription. Furthermore, MSE also uses approximate prescriptions for mass transfer from the third star onto the inner binary. In our simulation, about 5.5% of Galactic LISA double white dwarfs undergo a TCE phase before reaching the LISA frequency bandwidth. Inputs from hydrodynamical (Glanz & Perets 2020) simulations of eccentric mass transfer and triple mass transfer are needed to improve the eccentric mass transfer and TCE prescriptions.

We highlight that simulations of triple systems are computationally expensive. We simulated 105 triple systems, producing ∼3 × 103 LISA double white dwarfs. Deriving from the mass function in Fig. 1, there is a very low probability of producing high-mass white dwarfs. Hence, uncertainties in the statistics on the number of white dwarfs increase with mass. There is also a possibility of producing ONe white dwarfs from 8–10 M⊙ stars. Our models are created from progenitors in the mass range 1–8 M⊙. The sampling uncertainties in this mass range are too high to draw meaningful conclusions. In addition, we use random sampling to construct the initial triple population. However, more targeted sampling algorithms, such as STROOPWAFEL (Broekgaarden et al. 2019), could be employed to address the impact of sampling uncertainties in the initial population on rare events.

Finally, we note that MSE is a population synthesis code designed for statistical studies, and individual system modeling is not recommended. Due to variations in floating-point representation and rounding across different machines, the code may yield slightly different results when executed on different machines. However, these numerical difficulties average out on a large sample of the population. Given this inherent complexity, we limited the computational time to 10 hours per system. The majority of systems completed their evolution in under 2 hours. Within the ten-hour limit, 4% of systems did not complete their evolution. Of these, around 0.4% were dynamically unstable, while the remaining systems were undergoing stable secular evolution. Only 0.1% of the systems did not complete their evolution within ten hours and had white dwarfs or both components massive enough to evolve into white dwarfs within a Hubble time. This 0.1% of the systems contribute to some uncertainty in our predictions for LISA double white dwarfs, while the remaining incomplete systems were excluded without affecting the overall results.

5.3. Possibility of electromagnetic constraints to LISA observations