| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A84 | |

| Number of page(s) | 29 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556371 | |

| Published online | 06 February 2026 | |

Resolution and calibration effects in high contrast polarimetric imaging of circumstellar scattering regions

1

ETH Zurich, Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics,

Wolfgang-Pauli-Strasse 27,

8093

Zurich,

Switzerland

2

Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG,

38000

Grenoble,

France

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

11

July

2025

Accepted:

20

November

2025

Context. Many circumstellar dust scattering regions have been detected and investigated with polarimetric imaging. However, the quantitative determination of the intrinsic polarization and of dust properties is difficult because of complex observational effects.

Aims. This work investigates the instrumental convolution and polarimetric calibration effects for high contrast imaging polarimetry with the aim of defining the measuring parameters and calibration procedures for accurate measurements of the circumstellar polarization.

Methods. We simulated the instrumental convolution and polarimetric cancellation effects for two axisymmetric point spread functions (PSFs), a Gaussian PSFG and an extended PSFAO, typical for a modern adaptive optics system. The PSFs have the same diameter DPSF for the PSF peak. Further, polarimetric zero-point corrections (zp-corrections) were simulated for different cases, including coronagraphic observations and systems with barely resolved circumstellar scattering regions.

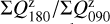

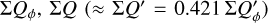

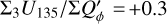

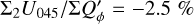

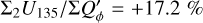

Results. The PSF convolution reduces the integrated azimuthal polarization, ΣQϕ, for the scattering region, while the net Stokes signals ΣQ and ΣU are not changed. For non-axisymmetric systems, a spurious Uϕ signal is introduced by the convolution. These effects are strong for compact systems and for the convolution with an extended PSFAO. Compact scattering regions can be detected down to an inner working angle of r ≈ DPSF based on the presence of a net ΣQϕ signal. Unresolved central scattering regions can introduce a central Stokes Q, U signal that can be used to constrain the scattering geometry even at separations r < DPSF. The smearing by the halo of the PSFAO produces an extended, low surface brightness polarization signal. These effects change the angular distribution of the azimuthal polarization, Qϕ(ϕ), but the initial Qϕ′(ϕ) signal can be partly recovered with the analysis of measured Stokes Q and U quadrant pattern. We find that applying a polarimetric zp-correction for the removal of offsets from instrumental or interstellar polarization depends on the selected reference region and can introduce strong bias effects for ΣQ and ΣU and the azimuthal distribution of Qϕ(ϕ). Strategies for the zp-correction are described for different data types, such as coronagraphic data or observations of partly unresolved systems. These procedures provide polarization parameters that can be easily reproduced with model simulations.

Conclusions. The simulations describe the impact of the PSF convolution and of calibration offsets for imaging polarimetry in a systematic way, and they show when these effects are strong and how they can be considered in the analysis. This defines also suitable measuring parameters and procedures for the quantitative characterization of the intrinsic scattering polarization Qϕ′ for an accurate determination of the properties of the circumstellar dust.

Key words: scattering / instrumentation: high angular resolution / techniques: polarimetric / protoplanetary disks / circumstellar matter, dust / extinction

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Dust in circumstellar disks around young stars and dust in shells around red giants have been recognized in many systems as infrared excess in the spectral energy distribution. This dust plays an important role in the formation of stars and planetary systems (Birnstiel 2024) and the mass loss of evolved stars and the dust enrichment of the interstellar medium (Ferrarotti & Gail 2006).

In the past decade, a lot of new information on circumstellar dust has been obtained with imaging observations of scattered stellar light in the near-IR and visual wavelength range. High-contrast instruments at large ground-based telescopes achieve an angular resolution of up to 20 mas, and this provides important information about the geometric distribution and the scattering properties of the circumstellar dust. In particular, the new information from scattered light observations is complementary to the extensive data already available from IR observations of the thermal emission of the dust around protoplanetary disks (e.g., Woitke et al. 2019), debris disks (e.g., Hughes et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2014), and red giants (e.g., Höfner & Olofsson 2018).

The determination of the geometric structure and the scattering properties of circumstellar dust near stars is of much interest for the investigation of the formation of planetary systems from dusty circumstellar disks around young stars. The measurement of circumstellar polarization is also important for the study of dust formation in the winds around cool, mass loosing stars. However, detection of the scattered intensity from circumstellar dust is difficult because the signal is faint and often hidden in the strong glare of the central star. This requires a careful separation of the stellar signal from the circumstellar signal, which can be achieved with high contrast techniques using space telescopes, such as the Hubble Space Telescope (HST; e.g., Kalas et al. 2013; Schneider et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2023) or JWST (e.g., Gáspár et al. 2023; Lawson et al. 2023), or with ground-based telescopes using adaptive optics (AO) systems (Milli et al. 2017; Ren et al. 2023).

High-resolution imaging polarimetry is a very powerful method to separate the circumstellar polarization signal introduced by dust scattering from the direct light of a bright central source, which usually has no or only a small net linear polarization (e.g., Kuhn et al. 2001; Quanz et al. 2011). Great progress has been achieved with new instruments for imaging polarimetry in combination with AO systems at large ground-based telescopes, including Subaru CIAO, HiCIAO, and SCeXAO instruments (Murakawa et al. 2004; Hodapp et al. 2008; Lucas et al. 2024); Gemini GPI (Perrin et al. 2015); and VLT NACO and SPHERE (Lenzen et al. 2003; Beuzit et al. 2019). Polarimetric imaging of many objects has been obtained, including protoplanetary disks (e.g., Avenhaus et al. 2018; Benisty et al. 2023, and references therein), debris disks (e.g., Esposito et al. 2020; Crotts et al. 2024), circumstellar shells around red giants (e.g., Ohnaka et al. 2016; Khouri et al. 2020; Montargès et al. 2023), and post-AGB stars (e.g., Andrych et al. 2023).

High-resolution imaging polarimetry is a quite new and not so simple observing technique because of point spread function (PSF) smearing and polarization cancellation effects and noise in the weak differential signal (Schmid et al. 2006; Schmid 2022). In addition the polarimetric calibration of the complex high contrast imaging systems has to be considered (e.g., Tinbergen 2007; Schmid et al. 2018; de Boer et al. 2020; van Holstein et al. 2020), including the temporal PSF variations for ground-based observations using AO systems (Tschudi & Schmid 2021; Ma et al. 2023). Depite this, many impressive results on dust scattering geometry have been obtained, but for most objects, no detailed analysis of the polarized intensity has been attempted, mostly because this was not the focus of the study. For some special cases, the polarized flux is derived more accurately to constrain the properties of the scattering dust, for example, for extended circumstellar disks (Stolker et al. 2016; Monnier et al. 2019; Milli et al. 2019; Arriaga et al. 2020; Hunziker et al. 2021), axisymmetric systems (Pinilla et al. 2018; Tschudi & Schmid 2021; Ma et al. 2023), and edge-on debris disks (e.g., Graham et al. 2007; Engler et al. 2017). It is highly desirable that such detailed studies on the circumstellar polarization are applied to a larger sample and are further improved for some key objects.

Accurate polarimetric measurements for circumstellar scattering regions require a good understanding of the observational aspects. Convolution effects degrade the measurable polarization signal, as described for some cases in Schmid et al. (2006), Avenhaus et al. (2017), Heikamp & Keller (2019), Tschudi & Schmid (2021), and Ma et al. (2023, 2024b). Additional issues are polarization offsets introduced by instrumental effects, interstellar polarization, and an intrinsically polarized central star. These offsets can be eliminated with a polarimetric normalization, which sets the polarization for a certain region to zero (Quanz et al. 2011; Avenhaus et al. 2014). We call this procedure hereafter polarimetric zero-point correction (zp-correction).

A very useful and frequently used way to describe the circumstellar signal is the azimuthal polarization Qϕ (Schmid et al. 2006; Quanz et al. 2013). A convolution or an offset by a zp-correction introduces for Qϕ quite complex changes, and some of these effects have not been described in detail or have not been investigated at all. For example, it is clear that polarimetric offsets, or a zp-correction, change the polarization signal, but this work describes for the first time how this change affects the azimuthal distribution of the circumstellar Qϕ signal. Because of the lack of a systematic study, it is difficult to extrapolate findings from the papers cited above to a more general picture.

For compact scattering regions near the star, the mentioned effects are much stronger, and they must even be considered for a qualitative interpretation of the polarization signal. Therefore, the scattering regions at small separations to the star of r ≲ 5 λ/D, or r ≲ 200 mas for large telescopes with AO systems, are often disregarded despite the fact that these regions are scientifically very interesting. They correspond for protoplanetary disks at ≈ 100 pc to the innermost <20 AU, which is where planets form (e.g., Birnstiel 2024), and for nearby red giant stars, they correspond to a separation of a few stellar radii where dust particles condensate (e.g., Höfner & Olofsson 2018). In non-coronagraphic and non-saturated data, this region is sometimes masked in the data reduction process because it looks “noisy” or shows an unexplained polarization pattern. However, these features might just be caused by a polarization offset or a convolution effect.

In coronagraphic observations, the central region is hidden behind the focal plane mask to achieve observations more sensitive to the polarization signal further out. Also for this type of data, it is important to understand the impact of the convolution and of polarization offsets.

This work presents model simulations and a parameter framework for a systematic description of the PSF convolution effects and an investigation of the polarimetric offsets introduced by the instrument, the interstellar polarization, the central star, or by the zp-correction applied to the data. The results should provide a better understanding of these effects for the interpretation of observational results and be useful for the definition of observing and measuring strategies for polarimetric imaging of circumstellar scattering regions.

This paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we describe the model simulation and introduce the used polarimetric parameters. Section 3 describes the degradation of the scattering polarization by the PSF convolution for axisymmetric circumstellar scattering regions and for inclined disk models. The polarimetric calibration and zp-correction effects are investigated in Sect. 4 and discussed in particular for coronagraphic observation and for data with only partially resolved circum-stellar scattering regions. In Sect. 5 the results are summarized and discussed in the context of observational data. Detailed information, in particular numerical results for the presented simulations, are given in the appendix.

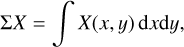

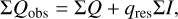

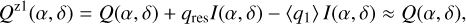

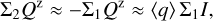

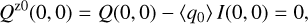

2 Model calculations

The block diagram in Fig. 1 gives an overview of the steps involved in imaging polarimetry using the Stokes Q = I0 − I90 and U = I45 − I135 polarization parameters as example. The full process is described by the boxes connected with red arrows, from the intrinsic polarization model defined in system coordinates Q′(x, y), U′(x, y) to the model in sky coordinates Q′(α, δ), U′(α, δ), including the contribution of interstellar polarization Q″(α, δ), U″(α, δ), to the observed signal Q(α, δ), U(α, δ) and the result after a possible polarimetric zp-correction Qz(α, δ), Uz(α, δ). This is simplified in the simulations according to the blue path in Fig. 1 by calculating the observed polarization signal in system coordinates Q(x, y), U(x, y) considering only convolution and polarimetric offsets and a zp-correction Qz(x, y), Uz(x, y) for the calibration of the data. This approach still considers many of the key aspects of polarimetric imaging but disregards second-order effects and particular problems of individual instruments or datasets. The parameters for the x, y coordinates are used for the description of the model simulations the x, y coordinates, while some general polarimetric principle are discussed for on sky parameters using (α, δ) coordinates. However, it is important to be aware of simplifying assumptions outlined in Fig. 1 for the interpretation of the model results.

|

Fig. 1 Block diagram with the simplified description of the simulated imaging polarimetry given in blue. The red arrows show the full imaging process from the intrinsic model to the on-sky model including interstellar polarization to the observed and possibly zp-corrected polarization signal. |

2.1 Intrinsic scattering models

The intrinsic models for the circumstellar dust scattering region and a point-like central star at x0, y0 are described by 2D maps for each component of the Stokes vector

(1)

(1)

The components describe the intensity, I′(x, y), and the linear polarization, Q′(x, y), U′(x, y), in x,y coordinates aligned with the object. The circular polarization signal V′ is expected to be much weaker for circumstellar scattering and is neglected. In principle, multiple scattering by dust can produce a circular polarization signal, in particular for (magnetically) aligned dust grains. Measurements for circumstellar circular polarization exist since many decades (e.g., Kwon et al. 2014; Bastien et al. 1989; Angel & Martin 1973), but the signals are weak, or originate from regions far away from the star, where interstellar magnetic fields may play a role. Considering this in our models is beyond the scope of this paper.

The models use  consisting of a star,

consisting of a star,  , with or without an intrinsic polarization,

, with or without an intrinsic polarization,  ,

,  , and an extended dust scattering region,

, and an extended dust scattering region,  , according to the vector components

, according to the vector components

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

In most models the star is not polarized and  and

and  are set to zero or

are set to zero or  and

and  .

.

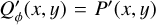

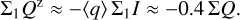

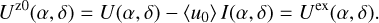

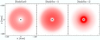

Scattering geometries. We considered the axisymmetric models Ring0 and Disk0 representing circumstellar disks seen pole-on or spherical dust shells as illustrated by the intensity maps  in the upper row of Fig. 2. The intrinsic polarization flux,

in the upper row of Fig. 2. The intrinsic polarization flux,  , is proportional to the intensity,

, is proportional to the intensity,  .

.

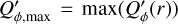

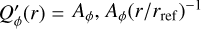

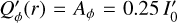

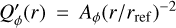

The Ring0 models have a mean radius, r0, and a Gaussian radial profile with full width at half maximum (FWHM) of ∆r = 0.2 r0, and r0 is varied from 3.15 to 806.4 mas. The Disk0 models are axisymmetric scattering regions extending from an inner radius, rin, to an outer radius, rout, with a surface brightness described by the power law

(5)

with reference radius rref. Three cases, Disk0α0, Disk0α−1, and Disk0α−2, are considered with α = 0 for a constant surface brightness and α = −1 and −2 for a brightness decreasing with distance. For all cases the outer radius is rout = 100.8 mas while the radius of the inner cavity is varied between rin = 3.15 mas and 50.4 mas to investigate the differences between fully resolved and partially resolved scattering regions. Figure 2 shows

(5)

with reference radius rref. Three cases, Disk0α0, Disk0α−1, and Disk0α−2, are considered with α = 0 for a constant surface brightness and α = −1 and −2 for a brightness decreasing with distance. For all cases the outer radius is rout = 100.8 mas while the radius of the inner cavity is varied between rin = 3.15 mas and 50.4 mas to investigate the differences between fully resolved and partially resolved scattering regions. Figure 2 shows  maps for Disk0α−1 with rin = 12.6 mas and 50.4 mas.

maps for Disk0α−1 with rin = 12.6 mas and 50.4 mas.

Simulations for non-axisymmetric scattering geometries are obtained by adopting the Ring0 and Disk0 geometries for inclined, flat disks with i = 60◦. The dust density in the disk plane ρd(rd) of the inclined models RingI60 and DiskI60α0, DiskI60α−1, DiskI60α−2 are described by the same radial parameters as for the axisymmetric models. The scattering angle in the inclined disk model varies as a function of azimuthal angle ϕ on the disk, and therefore the scattered intensity and polarization also depend on ϕ. This is simulated as in Schmid (2021) for flat, optically thin disks with a dust scattering phase function described by a Henyey-Greenstein function for the intensity with asymmetry parameter g = 0.6 and a Rayleigh scattering like dependence for the fractional polarization with pmax = 0.25. With these settings the resulting model maps I′(x, y) depend only on r0 for the RingI60 model and on α and the radius of the central cavity rin for the DiskI60 models. Figure 2 shows the maps for RingI60 and DiskI60α−1 with the same r0 and rin parameters as for the pole-on models. The major and minor axes of the inclined disks are aligned with the x and y coordinates and the backside of the disk is in the +y direction. Because of the strong forward scattering (g = 0.6) the intensity signal is enhanced on the front-side, and this is a frequently observed property for inclined disks (e.g., Ginski et al. 2023).

|

Fig. 2 Maps for the intrinsic disk intensity |

2.2 Sky coordinates and interstellar polarization

Observations are obtained in sky coordinates (α, δ) and the intrinsic maps in system coordinates Q′(x, y), U′(x, y) can be transformed into the sky coordinates Q′(α, δ), U′(α, δ) by a rotation of the geometry and the polarization vector (e.g., Schmid 2021). The signal reaching Earth Q″(α, δ), U″(α, δ) is often affected by interstellar polarization introduced by dichroic absorption of magnetically aligned interstellar grains (e.g., Draine 2003). This introduces a fractional polarization offset, which can be described for the usual low-polarization case (Q′, U′ ≪ I′ and q, u ≪ 1) by

(6)

(6)

(7)

where qis, uis are the components of the fractional interstellar polarization

(7)

where qis, uis are the components of the fractional interstellar polarization  with position angle θis = 0.5 · atan2(uis, qis)1 defined in sky coordinates. We used flux ratios to quantify the resulting intensity or polarization so that the interstellar transmission losses can be neglected. Extreme dichroic extinction by the interstellar medium can convert linear polarization partly to circular polarization (e.g., Kwon et al. 2014), but this is not considered in this work.

with position angle θis = 0.5 · atan2(uis, qis)1 defined in sky coordinates. We used flux ratios to quantify the resulting intensity or polarization so that the interstellar transmission losses can be neglected. Extreme dichroic extinction by the interstellar medium can convert linear polarization partly to circular polarization (e.g., Kwon et al. 2014), but this is not considered in this work.

2.3 Signal degradation by ground-based AO observations

The turbulence in the Earth atmosphere leads to a strong seeing convolution of the incoming signal (I″, Q″, U″). With an AO system the seeing can be strongly reduced but there remain smearing and polarimetric cancellation effects that can strongly change the spatial distribution of the observed signal I(α, δ), Q(α, δ), U(α, δ) when compared to the incoming signal (e.g., Perrin et al. 2003; Fétick et al. 2019). The effects are particularly strong for not well resolved structures near the star. The AO correction depends on the atmospheric turbulence and instrument properties, and therefore the observational PSF changes with time and shows various types of non-axisymmetric structures (e.g., Cantalloube et al. 2019). In addition, AO instruments are complex and they usually introduce instrumental polarization offsets which are difficult to calibrate accurately (Tinbergen 2007). These observational effects are investigated in this work.

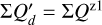

PSF convolution. Axisymmetric PSFs are adopted so that the convolved scattering signal does not depend on the orientation of the observed system. Therefore we can apply the convolution directly to the models described in disk coordinates (x, y). Real PSFs are variable and deviate from axisymmetry but assuming a stable, axisymmetric PSF is a reasonable approximation for PSFs with high Strehl ratio or for the averaged PSF obtained after a number of polarimetric cycles taken in field rotation mode.

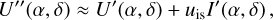

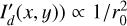

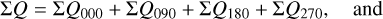

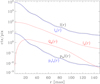

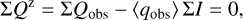

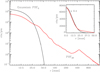

We used PSFAO(x, y) representing an AO system with a narrow core with FWHM or diameter of DPSF = 25.2 mas and an extended halo. This profile is obtained by averaging azimuthally the PSF described in Schmid et al. (2018) for the standard star HD 161096 taken under excellent condition with the AO instrument VLT/SPHERE/ZIMPOL in the N_I filter (λc = 817 nm) with a Strehl ratio of about 0.4. The radial profile of PSFAO is plotted in Fig. 3 together with a Gaussian profile PSFG with the same diameter DPSF, which is used to investigate the impact of the extended halo in PSFAO on the convolved signal. Convolution with a Gaussion PSF with DPSF ≈ λ/D could also represent roughly diffraction limited imaging polarimetry with a space telescope with diameter D or ground based seeing limited imaging polarimetry with DPSF of the order ≈1000 mas.

Polarimetric calibration. Many types of instrumental effects are introduced in observations taken with high-contrast imaging polarimetry and there exist established procedures to calibrate the data, for example for SPHERE/IRDIS (de Boer et al. 2020; van Holstein et al. 2020) and SPHERE/ZIMPOL polarimetry (Schmid et al. 2018; Hunziker et al. 2020; Tschudi et al. 2024). Individual instruments show also particular effects but these aspects are beyond the scope of this paper.

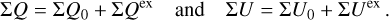

A very general and important observational effect are the offsets introduced by the interstellar pis or by the instrument polarization pinst of the kind described in Eqs. (6) and (7). Because the intensity of the star ΣIs is much higher than the polarization from the circumstellar dust ΣQd, ΣUd, by about a factor 100 or even more, already a small fractional polarization offset for the central star of about p ≈ 0.001 can strongly disturb the circumstellar signal, while p ≈ 0.01 can completely mask that signal. In addition, there could also be a contribution from an intrinsic polarization of the central star. The effects of polarimetric offsets do not depend on the orientation of the selected coordinate system, and therefore they can also be treated in the (x, y) coordinate system.

Unfortunately, it can be quite difficult to disentangle the different contributions to the overall polarimetric offset, and therefore an ad hoc zp-correction for the polarization is often applied to the data based on the assumption that the polarization of the target in a selected integration region is zero, or at least very small (Quanz et al. 2011; Avenhaus et al. 2014). A polarimetric offset sets the integrated Stokes parameters in a certain region to zero ΣQz = ∫ Qz(α, δ)dαdδ = 0 and similar for ΣUz = 0, but this procedure can introduce a bias. For coronagraphic observations, the central star cannot be included for the determination of the zp-correction, and this adds another complication, which we also describe later in the text.

|

Fig. 3 Radial profiles for the extended PSFAO (red) and the Gaussian PSFG (black). In the main panel, the total flux is normalized to 106 counts. In the inset, PSFG is reduced by a factor of 0.4 for a comparison of the PSF cores. The pixel size is 3.6 mas × 3.6 mas. |

2.4 Analysis of diagnostic polarization parameters

The impact of the convolution and the polarimetric zp-correction, follows from the comparisons between the simulated observational maps I(x, y), Q(x, y), U(x, y) or the corresponding zp-corrected polarization Qz(x, y), Uz(x, y) with the initial maps I′(x, y), Q′(x, y), U′(x, y).

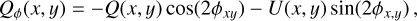

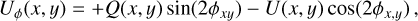

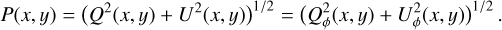

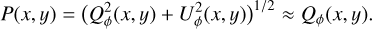

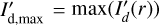

Circumstellar scattering produces predominantly a linear polarization in azimuthal direction Qϕ with respect to the central star located at x0, y0. Therefore Qϕ is a very useful polarization parameter which is defined by

(8)

(8)

(9)

with ϕxy = atan2((x − x0), (y − y0)) according to the description of Schmid et al. (2006) for the radial Stokes parameters Qr, Ur and using Qϕ = −Qr and Uϕ = −Ur. The Uϕ(x, y) parameter gives the linear polarization component rotated by 45◦ with respect to azimuthal component Qϕ(x, y). The different polarized intensities for a given point (x, y) in the polarization maps are related to the polarized flux for the linear polarization according to

(9)

with ϕxy = atan2((x − x0), (y − y0)) according to the description of Schmid et al. (2006) for the radial Stokes parameters Qr, Ur and using Qϕ = −Qr and Uϕ = −Ur. The Uϕ(x, y) parameter gives the linear polarization component rotated by 45◦ with respect to azimuthal component Qϕ(x, y). The different polarized intensities for a given point (x, y) in the polarization maps are related to the polarized flux for the linear polarization according to

(10)

(10)

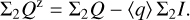

Figure 4 illustrates the relation between Qϕ and the Stokes parameters Q and U for a pole-on disk ring. In this model the Uϕ component is zero and P(x, y) = Qϕ(x, y) because of the axisymmetric geometry. Non-axisymmetric geometries can produce an intrinsic  signal, for example by multiple scattering (Canovas et al. 2015), but for the simple (single scattering) models adopted in this work the intrinsic

signal, for example by multiple scattering (Canovas et al. 2015), but for the simple (single scattering) models adopted in this work the intrinsic  -signal is also zero for inclined disks. However, the convolution and polarimetric offsets will introduce also for these models a Uϕ signal, which is equivalent to a non-azimuthal polarization component (Fig. 9).

-signal is also zero for inclined disks. However, the convolution and polarimetric offsets will introduce also for these models a Uϕ signal, which is equivalent to a non-azimuthal polarization component (Fig. 9).

The observational Q(x, y), U(x, y) or Qϕ(x, y), Uϕ(x, y) maps have in high contrast imaging polarimetry often a lower signal per pixel than the photon noise σ(x, y) or other pixel to pixel noise sources. Therefore, the polarized flux P(x, y) is biased, because it is always positive, and the measured values follow a Rice probability distribution. For a low polarization P(x, y) ≲ σ(x, y) the noise will introduce on average a signal of about P(x, y) ≈ +σ(x, y) (Simmons & Stewart 1985), and this can add up to a very significant spurious signal for the polarized flux ΣP in an integration region Σ containing many tens or more pixels. This noise problem is avoided by using Qϕ(x, y) for measuring the strength of the spatially resolved linear polarization (Schmid et al. 2006). This is a reasonable approximation, because circumstellar scattering produces predominantly a polarization in azimuthal direction with Qϕ(x, y) ≫ 0 and Uϕ(x, y) ≈ 0, and therefore one can consider Qϕ as rough proxy for P according to

(11)

(11)

Enhanced random noise in the data does not change the mean Qϕ signal for a pixel region, but P is for observational data often very significantly affected by the bias problem described above. The simulations in this work do not consider statistical noise in the data. However, there are other systematic differences between Qϕ(x, y) and P(x, y) because of the Uϕ(x, y) signal introduced by the PSF convolution and polarization offsets, which are described by the simulation results.

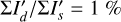

The convolution and zp-correction effects are quantified using polarization parameters integrated in well-defined apertures

(12)

where X is a place holder for the PSF convolved radiation parameters, such as X = {I, Q, U, P, Qϕ, Uϕ}, and similarly for X′ or Xz for the intrinsic models or zp-correcected models, respectively. The term Σ defines a circular aperture centered on the star for the determination of the system integrated parameters. Later, we also consider other axisymmetric circular and annular apertures for the parameters of radial subregions (see Sect. 4.3.1). Axisymmetric apertures are very useful for quantifying the convolution by an axisymmetric PSF and polarization offsets for an intensity signal dominated by the axisymmetric stellar PSF. An overview on the used polarization parameters is given in Appendix A (Tables A.1 and A.2).

(12)

where X is a place holder for the PSF convolved radiation parameters, such as X = {I, Q, U, P, Qϕ, Uϕ}, and similarly for X′ or Xz for the intrinsic models or zp-correcected models, respectively. The term Σ defines a circular aperture centered on the star for the determination of the system integrated parameters. Later, we also consider other axisymmetric circular and annular apertures for the parameters of radial subregions (see Sect. 4.3.1). Axisymmetric apertures are very useful for quantifying the convolution by an axisymmetric PSF and polarization offsets for an intensity signal dominated by the axisymmetric stellar PSF. An overview on the used polarization parameters is given in Appendix A (Tables A.1 and A.2).

For a given integration region, Σ, an “aperture” polarization, (Σ) = (ΣQ)2 + (ΣU)2)1/2. with the corresponding position angle θ(Σi) can be defined in the same way as for aperture polarimetry. These parameters are useful for specifying the polarization of the star or the fractional polarization p = (Σ)/ΣI and the fractional Stokes parameters q, u in order to quantify polarization offsets and zp-correction factors (see Appendix A).

The polarization parameters are usually normalized to the integrated intrinsic polarization  , such as

, such as  ,

,  , because

, because  provides a good reference for the characterization of the impact of the convolution or of offsets on polarization parameters.

provides a good reference for the characterization of the impact of the convolution or of offsets on polarization parameters.

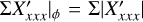

For the characterization of the azimuthal distribution of the polarization Q(ϕ) and U(ϕ), the four Stokes Q quadrants, Qxxx = {Q000, Q090, Q180, Q270}, and the four Stokes U quadrants, Uxxx = {U045, U135, U225, U315}, are used (Schmid 2021), while Xxxx stands for all eight parameters. They represent the Stokes Q and U polarization in the four wedges of 90◦ centered on the position angle ϕ = xxx, which form for well-resolved circum-stellar scattering regions the positive-negative Q and U quadrant patterns. The signals in these quadrants are changed by the convolution and polarization offsets, and they are useful to quantify the corresponding changes for the azimuthal distribution of the polarization signal Qϕ(ϕ).

|

Fig. 4 Maps for the Ring0 models with r0 = 12.6 mas (left), 25.2 mas (middle), and 50.4 mas (right) for the intrinsic circumstellar intensities, |

3 Polarization degradation by the PSF convolution

This section describes the basic PSF smearing and cancellation effects for imaging polarimetry of circumstellar scattering regions. The convolution is always applied to the intrinsic intensity I′ and Stokes Q′, U′ maps, or from maps with a polarization offset like the Q″, U″ maps, and from the resulting Q and U one can then derive according to Eq. (8)–(10) the convolved maps for the polarization parameters Qϕ, Uϕ and P (e.g., Tschudi & Schmid 2021). Alternatively, one could also apply the convolution to the  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  polarization components and derive from this the convolved intensity and polarization maps, because the convolution operation is distributive (PSF ∗ A + PSF ∗ B = PSF ∗ (A + B)). However, a direct convolution of the intrinsic azimuthal polarization (

polarization components and derive from this the convolved intensity and polarization maps, because the convolution operation is distributive (PSF ∗ A + PSF ∗ B = PSF ∗ (A + B)). However, a direct convolution of the intrinsic azimuthal polarization ( ) or of the polarized flux (PSF ∗ P′) gives wrong results.

) or of the polarized flux (PSF ∗ P′) gives wrong results.

3.1 Convolution for axisymmetric scattering models

3.1.1 Narrow pole-on rings

The convolution depends strongly on the spatial resolution, specifically on the angular size of the scattering signal compared to the PSF widths. This can be described by an axisymmetric scattering geometry like for a dust disk seen pole-on or a spherical dust shell.

Simulations for the convolution of the Ring0 models are shown in Fig. 4 for three ring sizes with r0 = 12.6, 25.2, and 50.4 mas and using the Gaussian PSFG. Maps for the intrinsic dust scattering intensities  , and convolved intensities Id(x, y) and the polarization Qd(x, y), Ud(x, y), Qϕ,d(x, y) are given. The central star is unpolarized in this model and there is Qd = Q, Ud = U and Qϕ,d = Qϕ. All three models have the same intrinsic flux

, and convolved intensities Id(x, y) and the polarization Qd(x, y), Ud(x, y), Qϕ,d(x, y) are given. The central star is unpolarized in this model and there is Qd = Q, Ud = U and Qϕ,d = Qϕ. All three models have the same intrinsic flux  and

and  , and therefore the peak fluxes scale as max

, and therefore the peak fluxes scale as max  and are higher for a smaller r0. The star is unpolarized and therefore does not contribute to the polarization maps. The star Is is not included in the intensity maps because for realistic cases it would dominate strongly the scattering intensity Id. For the intrinsic model there is

and are higher for a smaller r0. The star is unpolarized and therefore does not contribute to the polarization maps. The star Is is not included in the intensity maps because for realistic cases it would dominate strongly the scattering intensity Id. For the intrinsic model there is  and

and  . For axisymmetric models, this property is not changed by the convolution, and therefore the maps for P(x, y) and Uϕ(x, y) are not shown in Fig. 4.

. For axisymmetric models, this property is not changed by the convolution, and therefore the maps for P(x, y) and Uϕ(x, y) are not shown in Fig. 4.

Radial profiles for the intensity and azimuthal polarization Id(r) and Qϕ(r) are plotted in Fig. 5 for the Ring0 model convolved with the Gaussian PSFG and the extended PSFAO. The profiles are normalized to the intrinsic peak flux  and

and  respectively, to illustrate the signal degradation. The intensity is smeared by the convolution and this reduces the peak surface brightness of the rings but the total intensity is preserved

respectively, to illustrate the signal degradation. The intensity is smeared by the convolution and this reduces the peak surface brightness of the rings but the total intensity is preserved  . For the smallest model with r0 = 12.5 mas the ring structure is no more visible (Fig. 4) and there is a strong maximum at the center.

. For the smallest model with r0 = 12.5 mas the ring structure is no more visible (Fig. 4) and there is a strong maximum at the center.

The convolved polarization signal shows also a smearing and in addition a mutual polarimetric cancellation between the positive and negative quadrants in the Q and U maps (Schmid et al. 2006). This reduces strongly the polarization signal for Qd(x, y), Ud(x, y), and Qϕ(x, y) close to the star and produces also for compact rings a central zero (Figs. 4 and 5).

The integrated polarization ΣQϕ is reduced for the PSFG convolved models by factors  = 0.91, 0.66, and 0.28 for ring radii of r0 = 50.4 mas, 25.2 mas and 12.6 mas, respectively (Table 1). We measure the apparent ring size using the radius for the maximum surface brightness r(max(Qϕ)) and the size of the central cancellation hole by the radius rh at half maximum Qϕ(rh) = 0.5 · (max(Qϕ)). For r0 ≲ 0.5 DPSF the peak radius for the convolved ring is significantly larger than r0. For larger rings r0 ≳ DPSF these two radii agree well (r(max(Qϕ)) ≈ r0).

= 0.91, 0.66, and 0.28 for ring radii of r0 = 50.4 mas, 25.2 mas and 12.6 mas, respectively (Table 1). We measure the apparent ring size using the radius for the maximum surface brightness r(max(Qϕ)) and the size of the central cancellation hole by the radius rh at half maximum Qϕ(rh) = 0.5 · (max(Qϕ)). For r0 ≲ 0.5 DPSF the peak radius for the convolved ring is significantly larger than r0. For larger rings r0 ≳ DPSF these two radii agree well (r(max(Qϕ)) ≈ r0).

The  values in Table 1 are significantly lower for the PSFAO convolved models because of the much stronger smearing effects introduced by the PSF halo. For r0 < 4 DPSF the reduction is about a factor of 0.5 lower with respect to a convolution with PSFG, or very roughly at the level of the Strehl ratio for PSFAO simulated for the AO system.

values in Table 1 are significantly lower for the PSFAO convolved models because of the much stronger smearing effects introduced by the PSF halo. For r0 < 4 DPSF the reduction is about a factor of 0.5 lower with respect to a convolution with PSFG, or very roughly at the level of the Strehl ratio for PSFAO simulated for the AO system.

For very small rings with r0 = 0.25 DPSF and 0.125 DPSF only a very small amount of the Qϕ polarization remains and the radial Qϕ profile has for these two cases roughly the same shape as the convolved Ring0 with r0 = 0.5 DPSF with a peak at r(max(Qϕ)) ≈ (2/3) DPSF and a hole radius rh ≈ (1/3) DPSF. This represents the simulated inner working angle for the detection of a resolved polarization signal for a circumstellar scattering region. For observational data these limits might be less good because of PSF variation and alignment errors.

Importantly, the spatial resolution is practically not reduced by the convolution with PSFAO when compared to PSFG and the radii r(max(Qϕ)) and rh(Qϕ) for PSFAO are very similar for the two cases because both PSF have the same peak width DPSF. Therefore, the shape of the radial profiles in Fig. 5 are very similar for the two cases and the morphology of the strong polarization structures in the PSFG model maps of Fig. 4, would look practically the same for a convolution with PSFAO. The halo of the PSFAO introduces faint, extended polarization artifacts for axisymmetric geometries as described in the Appendix (Appendix B), but they are very weak with a surface brightness of ≲ 1% when compared to the peak signal of the ring.

|

Fig. 5 Normalized radial profiles for the intrinsic |

Results for Ring0 models with different radii r0.

3.1.2 Radially extended scattering regions

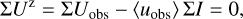

Axisymmetric, radially extended disks or shells models are just superpositions of concentric ring signals, and the polarimetric cancellation effects will be strong for the innermost regions and much reduced further out. Therefore, the convolved polarization signal strongly underestimates the scattering near the central star and can mimic the presence of a central cavity even if no such cavity is present. The effect is illustrated in Fig. 6 with PSFAO convolved Qϕ(x, y) maps for the models Disk0α0, Disk0α−1, and Disk0α−2, with radial brightness profiles  , and Aϕ(r/rref)−2, respectively. In all three cases the intrinsic disk extends from rin = 3.15 mas or 0.125 DPSF to rout = 100.8 mas. The radius of the convolution hole (rh(Qϕ)) is slightly smaller than 0.4 DPSF for the α = −2 case and slightly larger than 0.4 DPSF for the α = −1 disk with a flatter brightness distribution (Table C.1).

, and Aϕ(r/rref)−2, respectively. In all three cases the intrinsic disk extends from rin = 3.15 mas or 0.125 DPSF to rout = 100.8 mas. The radius of the convolution hole (rh(Qϕ)) is slightly smaller than 0.4 DPSF for the α = −2 case and slightly larger than 0.4 DPSF for the α = −1 disk with a flatter brightness distribution (Table C.1).

Constant surface brightness. The convolution effects for Disk0α0 are shown in Fig. 7 with radial profiles for the intrinsic parameters  ,

,  and the convolved intensity Id(r) and polarization Qϕ(r) for different inner disk radii rin and for PSFG and PSFAO convolution. The profiles Id(r) show for increasing cavity size rin an increasing central dip depth and width. The surface brightness Id(r) is strongly reduced after convolution with PSFAO while the central cavity is less pronounced. The convolution does not change ΣId but for PSFAO a lot of the signal is redistributed to radii r ≫ 100 mas.

and the convolved intensity Id(r) and polarization Qϕ(r) for different inner disk radii rin and for PSFG and PSFAO convolution. The profiles Id(r) show for increasing cavity size rin an increasing central dip depth and width. The surface brightness Id(r) is strongly reduced after convolution with PSFAO while the central cavity is less pronounced. The convolution does not change ΣId but for PSFAO a lot of the signal is redistributed to radii r ≫ 100 mas.

The convolved Qϕ(r) profiles show for all cases a central zero Qϕ(0) = 0, even for the disk without central cavity. Only models with rin ≈ DPSF or larger show an obvious difference when compared to the model without cavity. The Qϕ(r) profiles do not reach the intrinsic  level even for the convolution with a narrow PSFG, because of the polarimetric cancellation. For the convolution with PSFAO there is an additional reduction of the Qϕ(r) level by about 40% but despite this, the radial shape of the profiles is very similar for the two cases as follows also from hole radii rh(Qϕ) given in Table C.1.

level even for the convolution with a narrow PSFG, because of the polarimetric cancellation. For the convolution with PSFAO there is an additional reduction of the Qϕ(r) level by about 40% but despite this, the radial shape of the profiles is very similar for the two cases as follows also from hole radii rh(Qϕ) given in Table C.1.

Centrally bright scattering regions. Many circumstellar disks and shells show a steep surface brightness profile increasing strongly toward smaller radii. Therefore, the polarimetric cancellation suppresses efficiently the intrinsically very bright but barely resolved central signal (e.g., Avenhaus et al. 2018; Garufi et al. 2020; Khouri et al. 2020; Andrych et al. 2023).

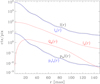

Simulations of radial profiles are shown in Fig. 8 for PSFAO convolved models DiskI60α−2 with intrinsic surface brightness profile for the polarization  with rref = 12.6 mas and Aϕ = 20.7 similar to Eq. (5) and for different cavity sizes rin. The convolved profiles Qϕ(r) show clearly how the central hole size decreases for smaller rin, and how the measurable peak polarization signal max(Qϕ(r)) increases. Despite the strongly increasing intrinsic

with rref = 12.6 mas and Aϕ = 20.7 similar to Eq. (5) and for different cavity sizes rin. The convolved profiles Qϕ(r) show clearly how the central hole size decreases for smaller rin, and how the measurable peak polarization signal max(Qϕ(r)) increases. Despite the strongly increasing intrinsic  signal at small radii the convolved Qϕ(r) curves converge to a limiting model case with ri ≈ 0.2 DPSF (≈5 mas), because even large amounts of intrinsic signal in the center are fully cancelled by the convolution (Table C.1). The Qϕ(r) profiles are still quite sensitive for constraining the intrinsic

signal at small radii the convolved Qϕ(r) curves converge to a limiting model case with ri ≈ 0.2 DPSF (≈5 mas), because even large amounts of intrinsic signal in the center are fully cancelled by the convolution (Table C.1). The Qϕ(r) profiles are still quite sensitive for constraining the intrinsic  signal around r ≈ DPSF based on the location of the flux maximum r(max(Qϕ)) and the amount of Qϕ(r) signal near this location. A careful analysis of Qϕ(r) can therefore constrain an inner cavity for a dust scattering region and this could be potentially useful for estimates on the dust sublimation radius for disks around young stars or the dust condensation radius for circumstellar shells around mass losing stars.

signal around r ≈ DPSF based on the location of the flux maximum r(max(Qϕ)) and the amount of Qϕ(r) signal near this location. A careful analysis of Qϕ(r) can therefore constrain an inner cavity for a dust scattering region and this could be potentially useful for estimates on the dust sublimation radius for disks around young stars or the dust condensation radius for circumstellar shells around mass losing stars.

Details of the profiles Qϕ(r) depend also on the power law index α for the surface brightness. The peak radii r(max(Qϕ(r)) and central hole radii rh for a given rin are a bit larger for Disk0α−1 than Disk0α−2 (Table C.1), because in this model the contributions of smeared signal from larger separations are more important than for Disk0α−2 and this reduces the apparent sharpness of the central cancellation hole.

|

Fig. 6 Central cancellation holes in the Qϕ(x, y) maps for the models Disk0α0, Disk0α−1, and Disk0α−2 after convolution with the extended PSFAO. The size of the inner cavity rin = 0.125DPSF (3.15 mas) is the same for all three models and indicated by the black dot. |

|

Fig. 7 Normalized profiles |

|

Fig. 8 Radial profiles Qϕ(r) for the Disk0α−2 model convolved with PSFAO on a log-scale (upper panel) and a linear scale (lower panel) for different inner cavities r0 as indicated by the colors. The thin black line is the intrinsic surface brightness |

|

Fig. 9 Maps for the intensity Id and polarization Qϕ, Q, U, Qϕ, Uϕ, and P (from top to bottom) for RingI60 models with r0 = 12.6 mas, 25.2 mas, and 50.4 mas after convolution with the Gaussian PSFG (first three columns). The last column gives the same for the intrinsic model with r0 = 50.4 mas. Stokes quadrant parameters are indicated in some Q and U maps. |

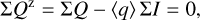

3.2 Convolution for inclined disk ring models

The scattering geometry for a rotationally symmetric system with an inclined symmetry axis is not axisymmetric and then new features appear in the intensity and polarization maps. This is illustrated in Fig. 9 by the PSFG convolved maps for the scattered intensity Id and the polarization parameters Q, U, Qϕ, Uϕ, and P for RingI60 models with an inclination of i = 60◦ and r0 = 12.5 mas, 25.2 mas and 50.4 mas and including the intrinsic maps for the last case. The central star is assumed to be unpolarized, or Q = Qd, U = Ud and P = Pd, and the stellar intensity is not included in the Id(x, y) intensity maps. All RingI60 models have the same intrinsic polarization  .

.

The ring front side is much brighter because of the adopted forward scattering parameter g = 0.6 for the dust and this is clearly visible for the I′(x, y) and I(x, y) maps for r0 = 50.4 mas. This changes for the less resolved systems into a front-side intensity arc for r0 = 25.2 mas or r0 = DPSF and a slightly elongated spot offset toward the front side for r0 = 12.6 mas (0.5 DPSF).

The inclined models show a left-right symmetry for the intensity Id(x, y) = Id(−x, y), for Stokes Q, the azimuthal polarization Qϕ, and the polarized flux P. The Stokes U-parameter has a left-right antisymmetry Ud(x, y) = −Ud(−x, y), as well as the Uϕ-signal introduced by convolution effects.

The intrinsic Stokes parameters Q′(x, y) and U′(x, y) show positive and negative regions which can be characterized by the quadrant polarization parameters  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  for Stokes Q′ and

for Stokes Q′ and  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  for Stokes U′ as indicated in Fig. 9. They are useful for the characterization of the azimuthal distribution of the polarization based on the natural Stokes patterns produced by circumstellar scattering (Schmid 2021). Quadrant parameters have been calculated for simple models of debris disks (Schmid 2021) and of transition disks (Ma & Schmid 2022).

for Stokes U′ as indicated in Fig. 9. They are useful for the characterization of the azimuthal distribution of the polarization based on the natural Stokes patterns produced by circumstellar scattering (Schmid 2021). Quadrant parameters have been calculated for simple models of debris disks (Schmid 2021) and of transition disks (Ma & Schmid 2022).

The intrinsic RingI60 models have strong positive Q090 and Q270 quadrants centered on the major axis of the projected disk, because of the high fractional polarization produced by scatterings with θ ≈ 90◦. The front side quadrant Q180 shows for well resolved systems a clear negative component, which is, however, less dominant than in intensity, because the fractional polarization of forward scattering is lower than for 90◦ scattering.

The negative Q000 and Q180 components disappear for not well resolved disks because the PSF smearing of the two strong positive components Q090 and Q270 cancel the signal of the negative Stokes Q quadrants. For the convolved RingI60 model with r0 = 12.6 mas there remain only two positive Qd-spots but their relative position still indicates the orientation of the projected major axis. The brighter disk front side produces in the Stokes Ud map a left side dominated by the positive U135 signal and a right side by the negative U225 component. This feature is still visible for barely resolved disks and this indicates the location of the disk front-side.

The intrinsic disk polarization of our models is azimuthal everywhere, and therefore the map  is equal P′(x, y), while

is equal P′(x, y), while  , according to Eq. (10). The convolved maps Qϕ(x, y) for r0 = 50.4 mas represents well the intrinsic map appart from the smearing, but for less well resolved disks Qϕ(x, y) starts to display negative values above and below the center and for r0 = 12.6 mas a strong, central quadrant pattern for Qϕ(x, y) is visible as expected for an unresolved, central source with a positive Stokes ΣQ signal and ΣU = 0.

, according to Eq. (10). The convolved maps Qϕ(x, y) for r0 = 50.4 mas represents well the intrinsic map appart from the smearing, but for less well resolved disks Qϕ(x, y) starts to display negative values above and below the center and for r0 = 12.6 mas a strong, central quadrant pattern for Qϕ(x, y) is visible as expected for an unresolved, central source with a positive Stokes ΣQ signal and ΣU = 0.

The convolution of the non-axisymmetric scattering polarization produces a Uϕ signal and we call this effect the convolution cross talks for the azimuthal polarization2 Qϕ → Uϕ. This effect increases with decreasing spatial resolution, and therefore the Uϕ(x, y) signal becomes stronger for less well resolved disks. For an unresolved disk the quadrant patterns for the azimuthal polarization Qϕ(x, y) = −Q(x, y) cos(2ϕxy) and Uϕ(x, y) = Q(x, y) sin(2ϕxy) are equally strong but rotated by 45◦. For the polarized flux P the convolved signal for large rings is roughly equal to the azimuthal polarization P(x, y) ≈ Qϕ(x, y), and for barely resolved rings it evolves toward P(x, y) ≈ Q(x, y) (Fig. 9).

3.2.1 Convolution and integrated polarization parameters

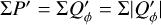

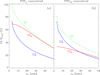

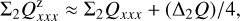

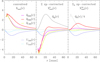

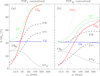

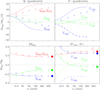

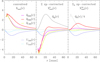

The convolution with a normalized PSF does not change the integrated Stokes polarization or the integrated intensity. Thus, there is for the RingI60 models ΣQ = ΣQ′ = 0.421  and ΣU = ΣU′ = 0, independent of the disk size or the spatial resolution. Contrary to this, the integrated polarization parameters ΣQϕ, ΣUϕ, and ΣP and the sums of absolute values Σ|Q| and Σ|U|, Σ|Qϕ| and Σ|Uϕ| depend on the resolution and the PSF convolution. The dependencies are plotted for the RingI60 models as a function of ring radius r0 convolved with PSFG and PSFAO in Fig. 10, and Table D.1 lists numerical values.

and ΣU = ΣU′ = 0, independent of the disk size or the spatial resolution. Contrary to this, the integrated polarization parameters ΣQϕ, ΣUϕ, and ΣP and the sums of absolute values Σ|Q| and Σ|U|, Σ|Qϕ| and Σ|Uϕ| depend on the resolution and the PSF convolution. The dependencies are plotted for the RingI60 models as a function of ring radius r0 convolved with PSFG and PSFAO in Fig. 10, and Table D.1 lists numerical values.

The red curves in Fig. 10 show ΣQϕ, which is large for well resolved disks and approaches zero for small, unresolved disks r0 → 0 when the Qϕ map shows a perfect positive-negative quadrant pattern with no net ΣQϕ polarization. For the intrinsic disk there is  and

and  and these relations are still approximately valid for well resolved disks convolved with PSFG because the convolution effects are small (Fig. 10a). The convolution with PSFAO introduces even for very extended disks strong smearing, because of the extended PSF halo (Fig. 10b). Therefore, ΣP is for well resolved disks larger than ΣQϕ by about 5% for the model with r0 ≈ 800 mas and about 18% for r0 = 201.6 mas (Table D.1).

and these relations are still approximately valid for well resolved disks convolved with PSFG because the convolution effects are small (Fig. 10a). The convolution with PSFAO introduces even for very extended disks strong smearing, because of the extended PSF halo (Fig. 10b). Therefore, ΣP is for well resolved disks larger than ΣQϕ by about 5% for the model with r0 ≈ 800 mas and about 18% for r0 = 201.6 mas (Table D.1).

For an unresolved scattering region r0 ≪ DPSF there remains only an unresolved polarized source with ΣP. Because of the alignment of the RingI60 models with the (x, y) disk coordinates, there is ΣQ = Σ|Q| = ΣP and ΣU = Σ|U| = 0. The azimuthal polarization is then zero ΣQϕ ≈ 0 and the integrated absolute values for the azimuthal polarization are Σ|Qϕ| = Σ|Uϕ| = (2/π) |ΣP| for the quadrant pattern of an unresolved source (Schmid 2021).

In the models a net signal in azimuthal polarization ΣQϕ > 0 or an integrated absolute signal Σ|Qϕ| larger than Σ|Uϕ| indicates the presence of at least a marginally resolved circumstellar polarization signal (Fig. 10). In observational data, ΣQϕ signals can also be produced by noise effects and one needs to derive for a given dataset the limits for a significant detection of a resolved circumstellar ΣQϕ-signal. However, one can expect for random noise sources introduced for example by the atmospheric turbulence, photon and read-out noise, that they produce also random positive and negative Qϕ and Uϕ signals, and different systematic effects like polarization offsets (see Sect. 4) or alignment errors produce no or only small positive or negative ΣQϕ and ΣUϕ signals. Therefore, the two criteria ΣQϕ > 0 and Σ|Qϕ| > Σ|Uϕ| are reliable indicators for the presence of resolved circumstellar polarization. Contrary to this, the ΣP signal is systematically enhanced by random noise and also polarization offsets change typically ΣP substantially.

|

Fig. 10 Integrated polarization parameters for the RingI60 model as a function of the ring radius r0 after convolution with PSFG (a) and PSFAO (b). All parameters have been normalized to the intrinsic value |

|

Fig. 11 Large-scale halo signals for the Stokes parameters Q, U and the azimuthal polarization Qϕ(x, y), Uϕ(x, y) for the RingI60 model with r0 = 50.4 mas convolved with PSFAO. The inset on the lower-right in each panel shows the disk ring in the center with a color scale reduced by 500 times. |

3.2.2 Halo signals produced by an extended PSFAO

The extended halo in the PSFAO of an adaptive optics system smears substantially the net Stokes polarization ΣQ, ΣU of a system over a large area producing an extended P(x, y) halo of linear polarization for r ≫ r0. This halo effect is illustrated in Fig. 11 for the PSFAO convolved RingI60 model with r0 = 50.4 mas, where the smeared ΣQ signal produces a polarized speckle ring ghost around r ≈ 0.4″ and a halo. The Stokes U signal in the halo is much weaker because there is no net U-signal for this model, and only a much weaker artifact pattern of the kind described in Appendix B is visible. The Q-halo produces extended Qϕ(x, y), Uϕ(x, y) quadrant patterns including the relatively strong speckle ring around r ≈ 0.4″, which shows the small scale imprint of the polarization from the bright ring.

The surface brightness of the halo is low and it can be difficult to recognize it in real data because of observational noise. Nonetheless, for the RingI60 model shown in Fig. 11 the Q-halo integrated in an annulus from r = 0.2″to 1.5″ is almost 30% of the system integrated ΣQ-signal (Table D.1). Therefore, it is important to use large integration apertures for the determination of ΣQ and ΣU for data convolved by an extended PSF.

The Qϕ signal in the halo integrated from r = 0.2″ to 1.5″ contributes less than 0.2% to the total ΣQϕ (Table D.1), because this signal has a positive-negative Qϕ, Uϕ quadrant patterns with zero net signal. Therefore, the measurement of ΣQϕ for a compact circumstellar scattering region should be restricted to a circular aperture which excludes the outer halo regions containing no net Qϕ signal but possibly substantial observational noise.

|

Fig. 12 Azimuthally averaged profiles for Qϕ(r), |Qϕ(r)|, and |Uϕ(r)| for the RingI60 models with r0 = 25.2 mas and 201.6 mas convolved with PSFAO. The green curve for the ratio |Uϕ(r)|/|Qϕ(r)| provides a rough measure for the convolution cross talk, and the dashed line indicates the system integrated value Σ|Uϕ|/Σ|Qϕ| from Table D.1. |

3.2.3 Convolution cross talk Qϕ → Uϕ or intrinsic Uϕ signal

The models considered in this work use a simpified description of the dust scattering which does no produce an intrinsic  polarization. However, it was pointed out in Canovas et al. (2015) that multiple-scattering by dust in optically thick protoplanetary disks with a non-axisymmetric scattering geometry can produce intrinsic

polarization. However, it was pointed out in Canovas et al. (2015) that multiple-scattering by dust in optically thick protoplanetary disks with a non-axisymmetric scattering geometry can produce intrinsic  signals representing non-azimuthal polarization components. Their simulations give

signals representing non-azimuthal polarization components. Their simulations give  signals of up to about ±5% of the azimuthal polarization

signals of up to about ±5% of the azimuthal polarization  and this U′-polarization can be useful to constrain the dust scattering properties and the disk geometry. This effect was also recognized in the disk models presented by Ma & Schmid (2022, Fig. 6).

and this U′-polarization can be useful to constrain the dust scattering properties and the disk geometry. This effect was also recognized in the disk models presented by Ma & Schmid (2022, Fig. 6).

As previously discussed, the PSF convolution can also produce very substantial Uϕ(x, y) signals for models with zero intrinsic  . This fact was already mentioned by Canovas et al. (2015), but they did not quantify this effect and their modeling used only a Gaussian PSF for the convolution.

. This fact was already mentioned by Canovas et al. (2015), but they did not quantify this effect and their modeling used only a Gaussian PSF for the convolution.

The RingI60 simulations can be used to quantify the Qϕ → Uϕ convolution signal for different disk sizes r0. As a simple metric for this effect, we used the ratio Σ|Uϕ|/Σ|Qϕ| given in Table D.1 (see also the Σ|Uϕ| and Σ|Qϕ| curves in Fig. 10). For an unresolved disk, the convolution gives as an extreme limit a ratio of Σ|Uϕ|/Σ|Qϕ| = 1. The ratio is 0.22 and still high for the PSFG convolved disk with r0 = 50.4 mas plotted in Fig. 9. A larger disk of about r0 = 201.6 mas is requird to reach a low ratio of 0.03 so that an intrinsic Uϕ-signal could be detectable.

The situation is worse for disk models convolved with PSFAO producing substantially more Qϕ → Uϕ cross talk, and the ratio Σ|Uϕ|/Σ|Qϕ| is 0.19 for r0 = 201.6 mas and still larger than 0.1 for r0 = 806.4 mas The strong smearing of the Stokes Q-signal produces in the halo a ratio Σ|Uϕ|/Σ|Qϕ| ≈ 1. For a more detailed analysis the radial dependence of the ratio |Uϕ(r)|/|Qϕ(r)| should be considered, and such profiles are shown in Fig. 12 for PSFAO convolved RingI60 models with r0 = 25.2 mas and 201.6 mas. For the compact disk the |Qϕ(r)| signal is only at the separation of the ring r ≈ 12−35 mas substantially larger than |Uϕ(r)|, but nowhere more than a factor of 2. For the unresolved polarization near the center and for the smeared halo signal the ratio is |Uϕ(r)|/|Qϕ(r)| ≈ 1. For the larger disk, the Qϕ(r) signal dominates the Uϕ(r) cross talk signal by about a factor of 20 at the location of the inclined ring r ≈ 100−200 mas.

This indicates that an intrinsic  polarization at the level of 0.05

polarization at the level of 0.05  is only detectable for large disks r0 ≳ 200 mas in high quality data for currently available AO systems, otherwise the convolution cross talks dominate. Helpful is, that the expected geometric structure of the observable Uϕ(x, y) signal produced by multiple scattering (see Canovas et al. 2015; Ma & Schmid 2022) is different from the Qϕ → Uϕ convolution artifacts, which can even be constrained strongly from the observed Qϕ(x, y) signal. In any case, the detection of the presence of intrinsic

is only detectable for large disks r0 ≳ 200 mas in high quality data for currently available AO systems, otherwise the convolution cross talks dominate. Helpful is, that the expected geometric structure of the observable Uϕ(x, y) signal produced by multiple scattering (see Canovas et al. 2015; Ma & Schmid 2022) is different from the Qϕ → Uϕ convolution artifacts, which can even be constrained strongly from the observed Qϕ(x, y) signal. In any case, the detection of the presence of intrinsic  polarization requires high quality data of an extended scattering region and a very careful assessment of the convolution cross talk effects.

polarization requires high quality data of an extended scattering region and a very careful assessment of the convolution cross talk effects.

Uϕ signal and Qϕ uncertainty. In many studies the Uϕ signal is used as a proxy for the observational uncertainty for the measured Qϕ signal. This is a reasonable approach for cases with small Qϕ → Uϕ cross talk, like axisymmetric or close to axisymmetric scattering geometries, and very extended systems like RingI60 models with r ≳ 200 mas. The spurious signals introduces by speckle noise, read-out and photon noise, and small-scale instrumental artifacts in the Uϕ map are then larger than the convolution cross talk and therefore also representative for observational uncertainties in the Qϕ map.

However, for non-axisymmetric compact scattering regions the Uϕ signal consist mainly of the well-defined systematic convolution cross talk signal with high ratios |Uϕ(r)|/|Qϕ(r)| ≳ 0.5 like the RingI60 r0 = 25.2 mas model in Fig. 12. Despite this the azimuthal polarization signal Qϕ can still be highly significant, because for high quality data the observational noise in Qϕ is much smaller than the systematic Qϕ → Uϕ cross talk. In such cases another metric than the Uϕ signal must be used for the assessment of the observational uncertainties, like the dispersion of the measured results for different datasets or a detailed analysis of speckle and pixel to pixel noise in the data.

Nonetheless, a low |Uϕ| signal can be used to identify high quality data within a series of measurements taken under variable observing conditions. Because the systematic cross talk Qϕ → Uϕ is anti-correlated with the quality of the observational PSF one can select the polarization cycles with low |Uϕ| and this may provide a higher quality Qϕ map for a target.

3.2.4 Convolution and quadrant polarization parameters

The convolution can change for not well resolved RingI60 models strongly the azimuthal distribution of the polarization signal Qϕ(ϕ) and Uϕ(ϕ). This can be quantified with the quadrant polarization parameters which provide a simple formalism for the description of polarimetric convolution effects. We use the symbol Xxxx for all quadrant parameters, and Qxxx or Uxxx for the four Stokes Q or Stokes U quadrants, respectively. The quadrant values are related to the integrated Stokes parameters according to

(13)

(13)

(14)

(14)

For the mirror-symmetric RingI60 models, there is also ΣQ000 = ΣQ270, ΣU045 = −ΣU315, and ΣU135 = −ΣU225 (Schmid 2021).

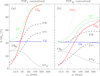

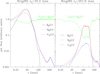

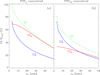

The convolution changes the flux in the different Stokes quadrants because of smearing and mutual cancellation as can be seen in Fig. 9. This degradation is also illustrated for the normalized quandrant parameters  for the PSFG and PSFAO convolved RingI60 models as a function of r0 in the upper panels of Fig. 13 (see also Table D.1). For smaller and less resolved disks all Q-quadrants approach the same value ΣQxxx = ΣQd/4 as expected for an unresolved system with an integrated polarization ΣQd. For the Stokes U quadrants the effects are equivalent on both sides of the y-axis, and strong smearing turns the sign of the weaker back-side quadrants values U045 and U135 to the sign of the strong front side quadrants. This produces for compact disks positive signals for U045 and U135 “on the left side” of the star, and negative signals for U225 and U315 “on the right” side in Fig. 9 for the RingI60 model with r0 = 12.6 mas.

for the PSFG and PSFAO convolved RingI60 models as a function of r0 in the upper panels of Fig. 13 (see also Table D.1). For smaller and less resolved disks all Q-quadrants approach the same value ΣQxxx = ΣQd/4 as expected for an unresolved system with an integrated polarization ΣQd. For the Stokes U quadrants the effects are equivalent on both sides of the y-axis, and strong smearing turns the sign of the weaker back-side quadrants values U045 and U135 to the sign of the strong front side quadrants. This produces for compact disks positive signals for U045 and U135 “on the left side” of the star, and negative signals for U225 and U315 “on the right” side in Fig. 9 for the RingI60 model with r0 = 12.6 mas.

Differential quadrant parameters. Despite the smearing and polarimetric cancellation the information about the relative intrinsic strengths of the quadrant parameters can still be recovered to some degree as long as the scattering region is partially resolved. This is possible, because the mutual compensation of the polarization signal changes opposite sign quadrants roughly by similar amounts (Fig. 13 upper panel), and in step with the degradation of the total azimuthal polarization ΣQϕ shown in Fig. 10 for the same models.

Therefore, good values to constrain the intrinsic  fluxes are the relative differential values

fluxes are the relative differential values

(15)

which quantify how much the individual Stokes Q quadrants contribute to the total Stokes Q signal (Eq. (13)) or how much more or less than the average contribution Q/4. According to Fig. 13 (lower left and Table D.2), the ∆Qxxx/ΣQϕ values are quite independent of the resolution for disks with r0 ≥ 50 mas, and one can still recognize for a RingI60 model disk with r0 ≈ 25 mas that the front side deviates more from the average than the back side. The relative differential quadrant values (Eq. (15)) are also practically the same for a convolution with PSFG and PSFAO and in very good agreement with the intrinsic values

(15)

which quantify how much the individual Stokes Q quadrants contribute to the total Stokes Q signal (Eq. (13)) or how much more or less than the average contribution Q/4. According to Fig. 13 (lower left and Table D.2), the ∆Qxxx/ΣQϕ values are quite independent of the resolution for disks with r0 ≥ 50 mas, and one can still recognize for a RingI60 model disk with r0 ≈ 25 mas that the front side deviates more from the average than the back side. The relative differential quadrant values (Eq. (15)) are also practically the same for a convolution with PSFG and PSFAO and in very good agreement with the intrinsic values

(16)

(16)

The equivalent quantities for the Stokes U quadrants are just ratios (ΣUxxx/ΣQϕ) because the average value (ΣU/4) is zero. Figure 13 (lower right) shows, that the relative Stokes U quadrant ratios deviate for small disks with r0 ≲ 25 mas substantially from a constant. This is caused by the morphology of the Stokes U map for the RingI60 model, which has one dominant positive U135 and one dominant negative U225 quadrant. Smearing and cancellation affect the weak quadrants ΣU045 and ΣU315 stronger than the reference value ΣQϕ, while the effects between the strong components U135 and U225 are smaller than for ΣQϕ, because the separation between the strong components is relatively large.

A useful alternative are the relative differential values between the U quadrants on the positive or negative x-axis side:

(17)

(17)

There is ∆U+ = −∆U− because of the symmetry of the RingI60 models. The ratio ∆U+/ΣQϕ is almost independent of the disk size r0 and the used PSF, according to the red line and points in Fig. 13 (lower right) and the values in Table D.2, which are very similar to the parameters ∆Qxxx/ΣQϕ. This demonstrates that differential quadrant parameters are useful to push the characterization of Qϕ(ϕ) and Uϕ(ϕ) for circumstellar scattering regions toward smaller separations.

|

Fig. 13 Quadrant polarization parameters ΣXxxx normalized to the intrinsic azimuthal polarization |

3.3 Convolution of inclined extended disks

Extended disks with unresolved or partially unresolved central regions are frequently observed (e.g., Garufi et al. 2022) and it is of interest to investigate regions close to the star r < DPSF because they correspond to the zone of terrestrial planet formation ≲ 3 AU for systems in nearby star forming regions. In particular, the polarization of the unresolved part of the disk at r ≲ 0.5 DPSF (<12.6 mas) can be compared with the polarization of the resolved region r ≳ DPSF to constrain the presence or absence of significant changes in the scattering properties between the two regions.

Polarization maps for the inclined and extended DiskI60α-2 models are plotted in Fig. 14 with radii for the inner cavities of rin = 0.125 DPSF, 0.5 DPSF, and DPSF, or 3.15 mas, 12.6 mas, and 25.2 mas, respectively. The inner disk rim is very bright for these models, and therefore the convolved disk maps look similar to the images in Fig. 9 for small disk rings. The model with rin = DPSF in Fig. 14 shows a resolved Qϕ disk image with small cross talk residuals in Uϕ, while the disk with a very small cavitiy of rin = 0.125 DPSF has strong quadrant patterns for Qϕ and Uϕ as expected from the net Q-signal of a bright, unresolved central disk region.

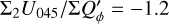

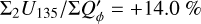

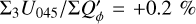

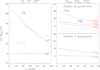

The integrated polarization parameters for the DiskI60α−2 models depend strongly on the inner disk radius rin according to Fig. 15 or the numerical values given in Table D.3. The parameters are all normalized to the intrinsic azimuthal polarization  for the disk with rin = 0.5 DPSF. The intrinsic polarization parameters

for the disk with rin = 0.5 DPSF. The intrinsic polarization parameters  and ΣQ = ΣQ′ = 0.421

and ΣQ = ΣQ′ = 0.421  are much larger for disks with small inner radii, for example by a factor 1.7 for rin = 0.125 DPSF when compared to rin = 0.5 DPSF. The convolution does not change the integrated Stokes polarization ΣQ = ΣQ′ but only redistributes spatially the signal Q′(x, y) → Q(x, y), and therefore the ΣQ curves are identical in the two panels of Fig. 15 for the models convolved with PSFG and PSFAO.

are much larger for disks with small inner radii, for example by a factor 1.7 for rin = 0.125 DPSF when compared to rin = 0.5 DPSF. The convolution does not change the integrated Stokes polarization ΣQ = ΣQ′ but only redistributes spatially the signal Q′(x, y) → Q(x, y), and therefore the ΣQ curves are identical in the two panels of Fig. 15 for the models convolved with PSFG and PSFAO.

Contrary to this, the PSF convolution reduces or even cancels the strong  -signal of the central region and the effect is more important for PSFAO than for PSFG. Therefore, ΣQϕ reaches for a given convolution PSF a limiting value for models with a cavity smaller than rin < 0.5 DPSF, despite the fact that the intrinsic

-signal of the central region and the effect is more important for PSFAO than for PSFG. Therefore, ΣQϕ reaches for a given convolution PSF a limiting value for models with a cavity smaller than rin < 0.5 DPSF, despite the fact that the intrinsic  and ΣQ′ increase steeply for rin → 0 for the DiskI60α−2 model.

and ΣQ′ increase steeply for rin → 0 for the DiskI60α−2 model.

The central quadrant patterns in the convolved Qϕ and Uϕ maps have a strength proportional to the net Q signal from the unresolved inner disk region. The central Stokes signal ΣQc ≈ ΣQ(r ≲ 0.5 DPSF) and ΣUc can be used to constrain the amount of polarization Pc and the averaged polarization position angle (θc = 0.5 · arctan2(ΣUc, ΣQc)) for the unresolved part. Differences between θc and the averaged polarization position angle of the resolved signal θd for ΣQ(r≳ 0.5 DPSF) can point to a structural change between the unresolved and the resolved part of the scattering region, or to a contribution from interstellar or instrumental polarization as discussed in the next section.

The intrinsic profile  for the DiskI60α−2 models is steep, and therefore the ratio of convolved parameters ΣQ/ΣQϕ changes strongly with the radius of the inner cavity rin (Fig. 10). According to Table D.3 the dependence is smaller for the DiskI60α0 and DiskI60α−1 models. Nonetheless, ΣQ/ΣQϕ could be a good parameter to derive from observational data the radius rin of an unresolved central cavity or other disk properties at r < DPSF, in particular when using constraints about disk inclination and surface brightness profile from the resolved part of the disk at r ≳ DPSF.

for the DiskI60α−2 models is steep, and therefore the ratio of convolved parameters ΣQ/ΣQϕ changes strongly with the radius of the inner cavity rin (Fig. 10). According to Table D.3 the dependence is smaller for the DiskI60α0 and DiskI60α−1 models. Nonetheless, ΣQ/ΣQϕ could be a good parameter to derive from observational data the radius rin of an unresolved central cavity or other disk properties at r < DPSF, in particular when using constraints about disk inclination and surface brightness profile from the resolved part of the disk at r ≳ DPSF.

|

Fig. 14 Intrinsic maps |

|

Fig. 15 Integrated polarization parameters ΣQϕ, ΣP, ΣQd for the inclined DiskI60α−2 model as a function of the radius of the inner cavity rin and for PSFG and PSFAO convolution. All values have been normalized to the intrinsic value |

3.4 The contribution of a polarized central star

The simulations presented up to now assume that the central star is unpolarized ( and

and  in Eqs. (3) and (4)), and therefore it does not affect the polarization signal of the circumstellar scattering region. However, often the stars with resolved circumstellar dust scattering regions have also unresolved components, as inferred for example from the thermal emission of hot dust. This dust can produce for the central, unresolved point-like source an intrinsic polarization, if scattering occurs in a non-symmetric structure. The central star can also be polarized by uncorrected contributions from interstellar or instrumental polarization. As the star is typically much brighter than the resolved circumstellar scattering already a small fractional polarization of the order ps = ΣQs/ΣIs ≈ 0.001 can have a strong impact on the observable polarization, and the following Sect. 4 addresses the question on how to correct for this.

in Eqs. (3) and (4)), and therefore it does not affect the polarization signal of the circumstellar scattering region. However, often the stars with resolved circumstellar dust scattering regions have also unresolved components, as inferred for example from the thermal emission of hot dust. This dust can produce for the central, unresolved point-like source an intrinsic polarization, if scattering occurs in a non-symmetric structure. The central star can also be polarized by uncorrected contributions from interstellar or instrumental polarization. As the star is typically much brighter than the resolved circumstellar scattering already a small fractional polarization of the order ps = ΣQs/ΣIs ≈ 0.001 can have a strong impact on the observable polarization, and the following Sect. 4 addresses the question on how to correct for this.