| Issue |

A&A

Volume 706, February 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A263 | |

| Number of page(s) | 24 | |

| Section | Planets, planetary systems, and small bodies | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556519 | |

| Published online | 18 February 2026 | |

The bulk metal content of WASP-80 b from joint interior-atmosphere retrievals

Breaking degeneracies and exploring biases with panchromatic spectra

Max Planck Institut für Astronomie,

Königstuhl 17,

69117

Heidelberg,

Germany

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

21

July

2025

Accepted:

3

December

2025

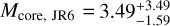

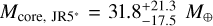

The atmospheres of warm gas giants can be readily characterized through transmission and emission spectroscopy. WASP-80 b is one such exoplanet, with an unusually low density that is in tension with the metal-rich composition expected for a planet of this mass. The aim of this work to derive precise constraints on WASP-80 b's bulk metal mass fraction, atmospheric composition, and thermal structure. We conducted a suite of retrievals using three approaches: traditional interior-only, atmosphere-only, and joint interior-atmosphere retrievals. We coupled the open-source model GASTLI to describe the planetary structure and thermal evolution and petitRADTRANS to describe the atmospheric chemistry and clouds. Our retrievals combined the mass and age with panchromatic spectra from JWST and HST in both transmission (0.5−4 μm) and emission (1–12 μm) as observational constraints. We identified two fiducial scenarios. In the first, WASP-80 b has an internal temperature consistent with its age in the absence of external heating sources; in addition, its atmosphere is in chemical equilibrium, with an atmospheric metallicity of M/H = 2.75−0.56+0.88× solar, a bulk metal mass fraction Zplanet = 0.12 ± 0.02, and a core mass Mcore = 3.49−1.59+3.49 M⊕. In the second scenario, WASP-80 b would be inflated by an additional heat source, possibly induced by magnetic fields, with an atmospheric metallicity of M/H = 10.00−4.75+8.20× solar, Zplanet = 0.28 ± 0 .11, and Mcore = 31.8−17.5+21.3 M⊕. The super-solar M/H and sub-solar C/O ratios in both scenarios suggest late pebble or planetesimal accretion, while additional heating is required to reconcile the data with the more massive core predicted by the core accretion paradigm. In general, joint retrievals are inherently affected by a degeneracy between atmospheric chemistry and internal structure. Taken together with flexible cloud treatment and an unweighted likelihood, this leads to larger uncertainties in bulk and atmospheric compositions than had previously been claimed.

Key words: planets and satellites: atmospheres / planets and satellites: composition / planets and satellites: gaseous planets / planets and satellites: interiors / planets and satellites: physical evolution

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open Access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1 Introduction

Extrasolar gas giants are composed of two main building blocks: hydrogen and helium (H/He) and metals, which include refractory material (rocks) and ices (e.g., H2O, CH4, NH3). Depending on the specific planet formation mechanism characterizing gas giants, their total metal and H/He mass fractions may vary widely. Two main formation mechanisms have been accepted: core accretion and gravitational instability. In the core accretion scenario, gas giants undergo a first stage where metal-rich material is accreted, leading to the formation of a core. This can be further enriched in more metals by accretion of pebbles and plan-etesimals, until the core reaches a critical mass. Then runaway accretion of a gas-rich (H/He) envelope starts. The more massive the planet is, the more gas it binds gravitationally (Helled & Morbidelli 2021; Helled 2023). Thus, core accretion produces massive planets that are metal-poor and dominated by H/He or Neptune-mass planets rich in rocks and ices. The accretion of metal-rich solids and H/He gas occurs within the same time scale in gravitational instability. Traditional gravitational instability models suggest that gas giants formed via this mechanism would have similar bulk compositions to their protoplanetary disk and host star (Helled & Schubert 2008; Boley et al. 2011). However, if the mass of the disk is not massive enough, or if rings and migration play an important role in disk evolution, gravitational instability can form planet cores as massive as in core accretion (Jiang & Ormel 2023; Rice et al. 2025). This is why determining the bulk composition and atmospheric composition of gas giants simultaneously is key to understand their formation and evolution pathways (Thorngren et al. 2016; Müller & Helled 2025).

The bulk amount of metals can only be estimated by comparing (or retrieving) the observed mass and radius to interior structure calculations. Interior models of gas giants typically assume that the planet is stratified in a metal-rich core and an envelope dominated by H/He (Burrows et al. 2004; Fortney et al. 2007; Baraffe et al. 2008; Leconte & Chabrier 2012; Nettelmann et al. 2013; Thorngren et al. 2016; Müller & Helled 2021; Miguel et al. 2022; Baumeister & Tosi 2023). Age is the third observable variable that constrains the internal composition of gas giants, as these contract due to thermal cooling given their Kelvin-Helmholtz timescale. In addition, the metallicity probed in the upper atmosphere by transmission spectroscopy can be used to narrow the envelope metal mass fraction (Bloot et al. 2023; Acuña et al. 2024), assuming that the composition is constant along the radius in the envelope. In retrievals, the precision of the inferred core mass and the total planet metal mass fraction depends on the precision of these four observable parameters. For gas-rich planets, an increase in radius precision produces greater improvements in bulk metal mass fraction estimates than mass (Otegi et al. 2020). In the case of gaseous giants, the precision of the age is particularly important for young planets (< 1 Gyr) because of how rapidly their radius changes between 100 Myr and 1 Gyr, as well as the degeneracy between the luminosity (or internal temperature) and bulk metal mass fraction (Müller & Helled 2023).

The characterization of the bulk composition of extrasolar gas giants faces challenges coming from the aforementioned degeneracies, as well as tensions between different observable parameters and techniques. Degeneracies can be solved by improving the precision of the age measurement, which depends on the spectral type of the star and their properties. Including additional observables could also reduce degeneracies. For example, a lower limit on the internal temperature was inferred from disequilibrium chemistry for WASP-107 b (Sing et al. 2024; Welbanks et al. 2024), a warm gas giant observed in transmission spectroscopy with JWST. This confirmed that WASP-107 b has a metal-rich core, and obtain a precise core mass estimate. Furthermore, the Love number, which quantifies the gravity field and therefore the internal density distribution (Love 1911), is sensitive to the mass of the core, enabling us to constrain it in retrievals (Kramm et al. 2011, 2012; van Dijk & Miguel 2025). This parameter has been measured for five extrasolar hot Jupiters (Buhler et al. 2016; Hardy et al. 2017; Csizmadia et al. 2019; Hellard et al. 2020; Barros et al. 2022; Bernabò et al. 2024). The number of exoplanets whose internal temperature or Love number are available is limited given the required observational criteria (Akinsanmi et al. 2020; Mukherjee et al. 2025).

Tensions can also exist between the bulk density and the inferred atmospheric metallicity. This is the case of sub-Saturn giants with warm equilibrium temperatures (Teq ≤ 1000 K) whose radii are ~1 RJup, such as HAT-P-12 b (Hartman et al. 2009), HAT-P-18 b (Hartman et al. 2011), WASP-29 b (Hellier et al. 2010), WASP-69 b (Anderson et al. 2014), WASP-67 b (Hellier et al. 2012), WASP-39 b (Faedi et al. 2011), and WASP-80 b (Triaud et al. 2013). These exoplanets are easily characterized via transmission spectroscopy given their large radii (Tsiaras et al. 2018; Pinhas et al. 2019). For example, JWST's panchromatic transmission spectrum of WASP-39 b indicate that its atmospheric metallicity is bimodal between solar and ~100x solar (Ahrer et al. 2023; Alderson et al. 2023; Rustamkulov et al. 2023; Feinstein et al. 2023). To explain simultaneously its low density and high atmospheric metallicity, a core-less internal structure is not sufficient because its observed radius is higher than that of a pure envelope exoplanet with a 100 × solar composition (Fortney et al. 2007).

Reconciling apparent discrepancies between interior and atmospheric analyses requires a combination of additional data and more advanced modeling. In general, these discrepancies could have multiple causes, including biases in the atmospheric retrievals (Bézard et al. 2022; Fisher et al. 2024) or unconstrained internal heating mechanisms that inflate the planet's radius (Thorngren & Fortney 2018). Complementary observables to the exoplanet spectra could help clarify the planet's composition and thermal properties, but obtaining such parameters is difficult. For instance, measuring the Love numbers of warm gas giants is challenging because they are further away from their star than their hot Jupiter counterparts (Hellard et al. 2019). Similarly, access to internal temperature constraints can be limited by clouds or equilibrium chemistry. Thus, a new modeling and data analysis approach is required to investigate the source of the differences in interior and atmospheric models. This tension could be mitigated by combining both retrievals into a joint interior-atmosphere retrieval. A joint interior-atmosphere retrieval analysis uses coupled interior-atmospheric calculations as the forward models and integrates the transmission or emission spectra with the observables parameters associated with the bulk density in the likelihood function of the retrieval. Such a retrieval was applied by Wilkinson et al. (2024) to the mass and a transmission spectrum dataset of WASP-39 b obtained by JWST's instrument NIRSpec-G395H. Nonetheless, their work presents two caveats: first, it did not include the effect of clouds in the transmission spectrum and, secondly, it did not consider emission and transmission spectra simultaneously to further constrain any degeneracies.

The aim of this work is to use joint interior-atmosphere retrievals to test whether this framework has this ability to infer more precise bulk composition estimates than the traditional interior structure retrievals by breaking degeneracies. To do this, we explored a suite of interior, atmosphere, and joint interior-atmosphere retrievals. WASP-39 b and WASP-80 b are the two super-puff warm gas giants with the widest wavelength coverage in their spectra. Of the two, WASP-80 b is the only one with emission spectra available; thus, we subsequently selected it as our science case. In Sect. 2, we compile the observational data for WASP-80 b available for our retrievals. In Sect. 3, we introduce the forward models for the three types of retrievals (interior-only, atmosphere-only, and joint). In Sect. 4, we describe our Bayesian framework, including the priors and the calculation of the likelihood function. We present the results of our suite of retrievals in Sects. 5.1–7. We discuss the benefit of joint retrievals in contrast to previous work and the implications for the interior structure and formation of WASP-80 b in Sect. 8. Finally, our conclusions are given in Sect. 9.

2 WASP-80 b data

WASP-80 b is a warm gas giant (Teq = 825 K) with an intermediate mass between that of Jupiter and Saturn. Its radius is similar to that of Jupiter, but its mass is approximately half of Jupiter's value (see Table 1), making it a puffy gas giant. It orbits a low-mass, late-type star (late K or early M) with an effective temperature of 4145 K at an orbital period of ~3 days. Its mass has been measured via the radial velocity method and its radius has been characterized with transit photometry, with consistent results across different ground-based data analyzes (Triaud et al. 2013; Mancini et al. 2014; Triaud et al. 2015). Table 1 shows the values we adopted for estimating for WASP-80 b's mass and radius, along with their references

In addition, WASP-80's age was estimated via gyrochronology to be ~100 Myr. It also presents chromospheric activity, which is expected in stars at young ages (Triaud et al. 2013). Gallet (2020) discussed how gyrochronology could yield a biased age for young stars (<100 Myr) because they might not yet have converged onto a well-behaved rotation-age sequence. In addition, these authors re-calculated the age of several stars via gyrochronology, including WASP-80, while accounting for star-planet tidal interactions. These interactions can spin up the stellar rotational period, biasing gyrochronology estimates towards younger ages. Thus, in this work, we have adopted the age estimate for WASP-80 from Gallet (2020), which is 1.352±0.222 Gyr.

WASP-80 b's short period and high planet-to-star radius ratio make it an excellent target for atmospheric characterization both in transmission and emission spectroscopy. It has been observed in both geometries by Spitzer photometry (Triaud et al. 2015; Wong et al. 2022). Furthermore, two low-resolution transmission datasets were obtained with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) using the STIS and WFC3 instruments. These observations revealed absorption features in the 1.4 bandpass, attributed to H2O and/or CH4. The STIS spectrum showed a slope at optical wavelengths, likely caused by aerosols or stellar contamination. Using atmospheric retrievals on these data, Wong et al. (2022) constrained the overall atmospheric metallicity to [M/H] = ~30–100 × solar, suggesting that the envelope is significantly enriched in metals. Similarly, WASP-80 b has been characterized by JWST with the NIRCam instrument both in transmission and emission. The analyzes of the NIRCam datasets have shown a sub-solar C/O ratio and a ~5 × solar metallic-ity. In addition, CH4 was detected at 6σ (Bell et al. 2023). This detection confirmed earlier tentative evidence from ground-based observations (Carleo et al. 2022). Furthermore, Wiser et al. (2025) detect H2O, CH4, CO, and CO2 at a high level of confidence by analyzing WASP-80 b's panchromatic emission spectrum from the JWST data sets. Finally, transmission spectroscopy observations have suggested the presence of condensates in the atmosphere of WASP-80 b. The composition of these condensates can be constrained through eclipse observations at short wavelengths (λ < 3 pm), which are covered by HST's WFC3, and JWST's NIRISS instruments. Such observations with these two instruments have revealed that the composition of the condensates may include Cr, Na2S, KCl, and ZnS, which are expected in warm (Teq < 1000 K) atmospheres (Jacobs et al. 2023). Furthermore, a moderately high Bond albedo was estimated for WASP-80 b, with a 1σ interval of AB = 0.15–0.40 (Morel et al. 2025).

Table 1 summarizes the spectrum datasets we re-analyze in our suite of retrievals with their respective wavelength ranges, references, and instruments. We discarded the photometric datasets, as they cover similar wavelength ranges to the HST and JWST low-resolution spectra. We do not include the emission dataset from Morel et al. (2025) in our retrievals due to the computational cost of reflected light calculations. Nonetheless, we discuss the effect of including reflected light data in our framework in the inference of the interior composition in Sect. 8.3.

All observational data used in our suite of retrievals of WASP-80 b.

3 Forward model

3.1 Interior structure model

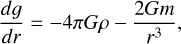

We adopted the GASTLI open-source package1 (GAS gianT modeL for Interiors; Acuña et al. 2021, 2025) as an interior structure model. GASTLI stratifies the planetary interior into two layers: a core (50% water and 50% silicate in mass) and an envelope (H/He mixed with water as a proxy for metals). The mass of the core is defined by the mass of the planet, Mpl and the core mass fraction (CMF) as Mcore = Mpl × CMF. Together with the planet mass and the CMF, the envelope metal mass fraction, Zenv, is an input parameter. Thus, the total bulk metal mass fraction of the planet can be computed as Zpl = CMF + (1 – CMF) × Zenv. GASTLI solves for the pressure P(r), temperature T(r), gravity g(r), and enclosed mass m(r) radial profiles by integrating the differential equations that correspond to hydrostatic equilibrium, an adiabatic temperature gradient, Gauss's theorem and conservation of mass (Eqs. (1)–(4))2. The computation of the adiabatic gradient requires the Grüneisen parameter, γ, and the seismic parameter, ϕ, which are calculated using the density, ρ, and internal energy, E (Eq. (5)). These two properties are directly obtained from the equation of state (EOS). The density, internal energy, and entropy of H/He are calculated using additive laws, in addition to a correction for non-ideal effects between H and He in the mixture (Chabrier & Debras 2021; Howard & Guillot 2023a). The properties of the water-rock mixture are derived in a similar manner, by applying the additive laws to the EOS of water (Mazevet et al. 2019) and rock (Lyon 1992; Miguel et al. 2022). The ices accreted by gas giants may not only contain water, but also methane and ammonia. Accounting for non-ideal effects caused by the mixing of rock and ices is challenging because the ice-to-rock mass ratio and the mass fractions of H2O, CH4, and NH3 in the ices are unconstrained (Nettelmann et al. 2016; Miguel & Vazan 2023). In the absence of more detailed observational constraints, the use of ideal additive laws is a reasonable approach.

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

To solve for the differential equations that govern the internal structure, the following boundary conditions are defined. First, the gravity at the center of the planet is zero, g(r = 0) = 0. Secondly, the pressure and the temperature need to be specified at the surface interface. This is the external interface of the outermost computational layer in the 1D grid that represents the radius, not the physical surface found in rocky planets. These surface conditions, P(r = Rint) = Psurf and T(r = Rint) = Tsurf, are a flexible input for GASTLI, and can be estimated with pre-computed atmospheric grids in an iterative scheme (see Sect. 3.1.1) or it can be a free parameter (Sect. 3.1.2). The former is required to obtain a grid of mass-radius-age models for the traditional interior retrievals (Sect. 6), while the latter is more appropriate for our approach to the joint interior-atmosphere retrievals (Sect. 7). In the joint retrievals, the surface pressure if fixed to Psurf = 1000 bar.

3.1.1 Grid of mass–radius–age models

We used GASTLI's default grid of atmospheric models, which was precomputed using petitCODE (Mollière et al. 2015, 2017). The grid spans a wide range of planetary surface gravities (log gsurf = 2.6–4.2 cm/s2), equilibrium temperatures (100–1000 K), internal temperatures (50–950 K), metallicities (0.01–250 × solar), and C/O ratios (0.10–0.55), making it well-suited for gas giants such as WASP-80b. In brief, petitCODE computes self-consistent pressure-temperature (P–T) profiles by solving radiative transfer via the correlated-k method, under the assumption of 1D radiative–convective equilibrium. The Bond albedo is calculated self-consistently, based on the energy balance between the emitted and absorbed radiation at the top of the atmosphere. In GASTLI's default atmospheric grid, chemical equilibrium, and cloud-free (clear) atmospheres are assumed. For each coupled model, GASTLI extracts the corresponding P–T profile and computes the atmospheric thickness by integrating the hydrostatic equilibrium equation down to a transit pressure of 20 mbar. This approach enables accurate modeling of observable planetary radii. We refer to Acuña et al. (2024) for more details, including the opacities of atmospheric species and their references.

To achieve consistency between the interior and atmospheric profiles, we used the iterative coupling scheme described in Acuña et al. (2021). In this scheme, we defined the interior radius (Rint) as the radius output by the interior model. An initial guess for Rint determines the planet's surface gravity, which is then used to interpolate a surface temperature from the atmospheric grid. The interpolation is performed at fixed values of planet mass, envelope metallicity, core mass fraction, and internal temperature. The interpolated surface temperature then serves as the boundary condition for the interior model. The new interior radius is recalculated, and the process repeats until convergence in radius and surface temperature is reached. The final mass and radius are calculated consistently by adding its respective atmospheric contributions.

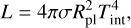

GASTLI calculates the planet's thermal evolution by solving the entropy (S) loss over time (t) due to secular cooling. We computed a sequence of models at different internal temperatures (Tint) – or thermal states. The luminosity, L, at each state is related to the internal temperature and total radius, Rpl, according to Eq. (6). The luminosity is calculated by also using the Stefan-Boltzman constant, σ = 5.67 × 10−8 W m−2 K−4. Entropy as a function of time, S (t), is obtained by integrating the change in entropy ∂S over time, as defined in Eq. (7). This calculation requires us to extract the temperature and enclosed mass profiles, T(r) and m(r), from the interior model to estimate T(m). The resulting S(t) relation enables GASTLI to predict radius and luminosity as functions of age. Here, we adopted GASTLI's default initial entropy, which corresponds to a hot start entropy value S0 = 12 kB mH3. For planets whose age >100 Myr, the choice of the initial entropy does not impact the radius-age and luminosity-age functions (see Figs. 5 and 9 in Spiegel & Burrows 2012; Acuña et al. 2024, respectively). Moreover, hot-start initial entropy conditions are consistent with observations of cold gas giants (Nowak et al. 2020; Trevascus et al. 2025).

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

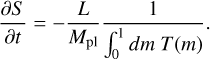

In the mass–radius–age grid, we assumed a constant equilibrium temperature at null Bond albedo, equal to that ofWASP-80 b, Teq = 825 K. The definition of this parameter is given in Eq. (8), where T*, R*, and ad are the stellar effective temperature, stellar radius and orbital semi-major axis (Table 1). PetitCODE uses this equilibrium temperature as input and calculates the Bond albedo self-consistently by generating synthetic reflection spectra and integrating over wavelength. We generated a regular grid of GASTLI models across a 4D hyperparameter space by varying the planet mass, CMF, the envelope's log(M/H), and internal temperature (Tint). The input arrays are finely sampled: mass from 0.35 to 0.75 MJup, with ΔM = 0.05 MJup; CMF from 0.0 to 0.90 with ΔCMF = 0.10, plus the value CMF = 0.99 as a last point in the array; log(M/H) is evaluated at −2.0 and 2.4, in addition to the values comprised between 0.0 and 2.0 with Δlog(M/H) = 0.5; Tint is calculated at 50 K, and 100–800 K with ΔTint = 100 K. Thus, our grid contains the planetary radius and age for 5670 models in total. This grid will be interpolated with scipy's function ```RegularGridlnterpolator`` in the traditional interior retrievals in Sect. 6 to evaluate the forward model:

(8)

(8)

3.1.2 Grid for joint retrievals

As discussed in Sect. 3.1, the traditional interior structure retrievals require the interior model to be coupled to a grid of self-consistent atmospheric models to compute the radius and age as a function of internal temperature. However, for the joint interior-spectrum retrievals, we required the atmospheric profiles to be more flexible than the self-consistent grid. The transmission and emission spectrum may show spectral features that can only be explained by physics that deviate from the assumptions of the self-consistent grid, such as clouds or hazes, or a temperature inversion caused by strong optical absorbers in the upper atmosphere.

We coupled the thermal structure analytical model and the new grid of interior structure models. The coupling algorithm is slightly different from the traditional one described in Sect. 3.1.1 and in Acuña et al. (2021). These differences include using additional parameters (i.e., the cloud and thermal structure parameters), adopting an additional step to calculate the mass mixing ratios of the atmospheric species with easyCHEM, and computing the transmission and/or emission spectrum with petitRADTRANS after the coupled model has converged (see Sect. 3.2 for a description of petitRADTRANS and easyCHEM). More details on the modified coupling algorithm are given in Appendix B. In the following, we explain how we obtain the grid for the joint retrievals.

To calculate the grid for joint retrievals, we separated GASTLI's interior module from its atmospheric module. This allowed us to calculate the radius (Rint) and the entropy S(P = 1000 bar) independently of the atmospheric parameters, such as the atmospheric metallicity, log(M/H), or the internal temperature, Tint.

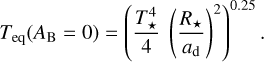

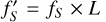

A set of retrievals in our suite requires to calculate the age because it is taken into account as an observable in the calculation of the log-likelihood (see Sect. 4.1). Solving for the Tint-radius-age relations involves computing the function, fS = ∂S/∂t (Eq. (7)). In this equation, the luminosity, L, is dependent on the intrinsic (or internal) temperature (Eq. (6)). Also, Tint is an input to the analytical P–T model that outputs the surface temperature, Tsurf. Consequently, we could not calculate and store the function fS = ∂S/∂t in a grid because the internal temperature was not known a priori. Thus, GASTLI's grid for the joint retrievals cannot contain a multidimensional table of fS. Instead, we defined a new function:  . Then we stored a table for this parameter together with Rint and S(P = 1000 bar). For one instance of a converged coupled interior-atmosphere model, we interpolated the internal radius, entropy and

. Then we stored a table for this parameter together with Rint and S(P = 1000 bar). For one instance of a converged coupled interior-atmosphere model, we interpolated the internal radius, entropy and  values at different surface temperatures that are obtained by varying the internal temperature Ti in the Guillot (2010) P–T profile, while setting the remaining free parameters constant. We defined the internal temperature in Eq. (6) equal to the intrinsic temperature in the P–T profile, Tint = Ti, to compute its corresponding luminosity array. The arrays containing L(Tint) and

values at different surface temperatures that are obtained by varying the internal temperature Ti in the Guillot (2010) P–T profile, while setting the remaining free parameters constant. We defined the internal temperature in Eq. (6) equal to the intrinsic temperature in the P–T profile, Tint = Ti, to compute its corresponding luminosity array. The arrays containing L(Tint) and  were then used to calculate an array for fS, as they are necessary to solve the differential equation of thermal evolution (Eq. (7)). Consequently, we obtained the radius-age curve that allowed us to evaluate the age at the Ti value proposed by the sampler.

were then used to calculate an array for fS, as they are necessary to solve the differential equation of thermal evolution (Eq. (7)). Consequently, we obtained the radius-age curve that allowed us to evaluate the age at the Ti value proposed by the sampler.

The input variables for GASTLI's joint grid are the planet mass, CMF, the metal mass fraction of the envelope, Zenv, and the surface temperature and pressure. We set the surface pressure to Psurf = 1000 bar, as this is the maximum pressure level appropriate for both our analytical P–T profile and spectrum generator (Sect. 3.2). Similar to our mass-radius-age grid, we generate a rectangular multidimensional grid by evaluating the interior models at the values specified by fixed arrays of the input parameters Mpl, CMF, Zenv, and Tsurf. These arrays consist of Mpl = 0.35-0.75 MJup, with ΔMpl = 0.20 MJup; CMF = 0.0–0.99, with ΔCMF = 0.10; and Tsurf = 700–6000 K, with ΔTsurf = 100 K. For the envelope mass fraction, Zenv = 0.0 to 0.05 at intervals of ΔZenv = 0.01, continued by the ranges Zenv = 0.10–0.30 and Zenv = 0.40–0.80 at intervals of ΔZenv = 0.05 and 0.10, respectively. Detailed models of the joint grid can be found in Appendix B.

3.2 Atmospheric model

As forward atmospheric model to generate transmission and emission spectra, we use petitRADTRANS (pRT, Mollière et al. 2019) version 3.0. pRT is an optimized open-source radiative transfer package that offers flexibility in terms of the P–T profiles, chemistry, cloud treatment, and geometry. The computation of emission spectra requires a measurement the planet-to-star flux ratio; thus, we interpolated pRT's in-built library of PHOENIX stellar spectra (Husser et al. 2013) as described by van Boekel et al. (2012).

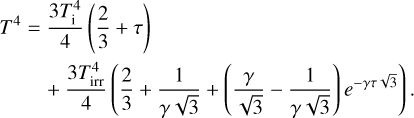

To parametrize a flexible P–T profile, we employed the simple analytical model provided by Guillot (2010). It enables us to estimate the thermal structure of irradiated planets by using four free parameters in Eq. (9). The irradiation temperature is defined as  , while the optical depth for a given pressure P is defined as τ = P × κIR/g. Here, Te is denoted as the equilibrium temperature in the model, Ti is the intrinsic temperature, and g is the surface gravity. Finally, κIR corresponds to the mean infrared (gray) opacity, and γ is the optical-to-infrared opacity ratio. These parameters can be physically interpreted, for example we could identify Te = Teq = 825 K, and Ti = Tint as calculated by the thermal evolution in the mass–radius–age models (Sect. 3.1.1). However, this would limit the shape of the P–T profile in the atmosphere-only and joint retrievals, so we treat them as free parameters (see Sect. 4.2 for their priors). We will only physically interpret Ti as the internal temperature Tint in the joint retrievals that include the age as an observable to compute the log-likelihood (see Appendix B and Sect. 4.1). The temperature profile is expressed as:

, while the optical depth for a given pressure P is defined as τ = P × κIR/g. Here, Te is denoted as the equilibrium temperature in the model, Ti is the intrinsic temperature, and g is the surface gravity. Finally, κIR corresponds to the mean infrared (gray) opacity, and γ is the optical-to-infrared opacity ratio. These parameters can be physically interpreted, for example we could identify Te = Teq = 825 K, and Ti = Tint as calculated by the thermal evolution in the mass–radius–age models (Sect. 3.1.1). However, this would limit the shape of the P–T profile in the atmosphere-only and joint retrievals, so we treat them as free parameters (see Sect. 4.2 for their priors). We will only physically interpret Ti as the internal temperature Tint in the joint retrievals that include the age as an observable to compute the log-likelihood (see Appendix B and Sect. 4.1). The temperature profile is expressed as:

(9)

(9)

We explore both equilibrium chemistry and free chemistry in our suite of retrievals. In equilibrium retrieval, for a given pair of atmospheric metallicity, [M/H], and carbon-to-oxygen ratio, C/O, we calculate the mass fraction abundances by using pRT's pre-computed easyCHEM tables (Mollière et al. 2017; Lei & Mollière 2025). easyCHEM calculates and minimizes the Gibbs free energy of a mixture as a function of pressure, temperature and elemental makeup following the methods described in the Chemical Equilibrium with Applications (CEA) software (Gordon 1994; McBride 1996). We include a variety of chemical species that are expected in warm gas giant atmospheres to generate spectra in our retrievals. Their respective opacity and line list data references are: H2O (Polyansky et al. 2018), CO (Rothman et al. 2010), CO2 (Yurchenko et al. 2020), CH4 (Hargreaves et al. 2020), NH3 (Coles et al. 2019), HCN (Barber et al. 2014), Na (Allard et al. 2019), and K (Mollière et al. 2019).

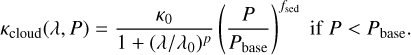

In our retrievals involving transmission spectra, we include condensates as an opacity source. The parameterization of the cloud opacity, κcloud, of our condensate model is shown in Eq. (10). The cloud model consists of five free parameters (see Sect. 4.2 for their priors). Then, λ0 corresponds to the reference wavelength at which the reference opacity, κ0, is defined. fsed is the cloud scale height decrease factor, and p is the power law coefficient of the opacity with wavelength for λ >> λ0. For pressures higher than the base pressure of the cloud layer (Pbase), the cloud opacity is set to zero as κcloud(λ, P > Pbase) = 0. Our condensate model incorporates the behavior of cloud opacities at different wavelength ranges, which consists of a constant opacity at short wavelengths (λ < λ0) and of a slope at large wavelengths (Dyrek et al. 2024). This is computed as:

(10)

(10)

4 Bayesian framework

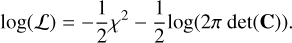

In the atmosphere-only and joint retrievals, we adopted nested sampling (Feroz & Hobson 2008; Feroz et al. 2009; Buchner et al. 2014) to sample the posterior distribution functions, as implemented in the pRT package by Nasedkin et al. (2024). We describe how the log-likelihood function is calculated in these retrievals in Sect. 4.1. In the traditional interior structure retrievals, we employed the Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) ensemble sampler implemented in the emcee package (Foreman-Mackey et al. 2013). The likelihood function was constructed following Eqs. (6) and (14) in Dorn et al. (2015) and Acuña et al. (2021), respectively. The likelihood function is computed by using the observed values of mass, radius, age, and atmospheric metallicity (see Sect. 6). We initialized 32 walkers and ran the chains for 105 iterations. This setup ensures that the chain is sufficiently long to fulfill the MCMC convergence criterion τ << Nchain/50 for a typical interior retrieval autocorrelation time of τ ≃ 100–200 (Acuña et al. 2024).

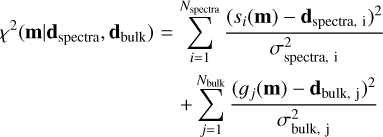

4.1 Likelihood function

Equation (11) shows the χ2 function used to calculate the log-likelihood function (Eq. (12)). The model parameterization vector, m, contains the input variables of a coupled interior-atmosphere model, which are the mass Mpl and the other 12 parameters shown in Fig. B.2. We separate the data in two vectors: the vector containing the spectral fluxes (transmission, emission or both), dspectra, and the vector containing other observables related to bulk density and evolution information, dbulk. Depending on the retrieval, dbulk may contain the planetary radius (in joint emission retrievals), the planet mass (all joint retrievals) and/or the age. In the retrievals that include the transmission spectra, the planet radius is not included as a bulk observable in dbulk because this information is already contained in the transmission spectrum. In the first term in Eq. (11), the vector si(m) is the spectra binned at the same resolution and central wavelengths as the observed spectra, with corresponding uncertainties σspectra. Similarly, in the second term, gj(m) is the coupled interior-atmosphere model parameters related to bulk density and evolution (mass, radius and age), while σbulk are the uncertainties of the observed mass, radius and age. Nspectra and Nbulk are the number of data points contained in dspectra and dbulk, respectively.

(11)

(11)

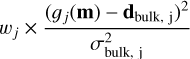

The final log-likelihood function, log(ℒ(m|dspectrum, dbulk)), is obtained by adding a normalization constant to χ2 (Eq. (12); see also Eq. (1) in Nasedkin et al. 2024). This constant takes into account the determinant of the covariance matrix, C, which we assume to be diagonal. In previous work, Wilkinson et al. (2024) multiplied the contribution of each data point contained in dbulk in the second term of Eq. (11) by a weight parameter, wj - in the form  . This weight parameter allows for the importance of an observable in the log-likelihood to be controlled. In our joint interior-atmosphere retrievals, we chose not to weight the bulk observables (mass, radius, and/or age) based on the sensitivity tests discussed in Sect. 8.2.

. This weight parameter allows for the importance of an observable in the log-likelihood to be controlled. In our joint interior-atmosphere retrievals, we chose not to weight the bulk observables (mass, radius, and/or age) based on the sensitivity tests discussed in Sect. 8.2.

(12)

(12)

Priors used in the interior and equilibrium chemistry atmosphere retrievals.

4.2 Priors

Table 2 indicates the prior distributions used for the free parameters in the interior and equilibrium chemistry atmosphere retrievals. In the interior retrievals, if the atmospheric metallicity is included as an observable in the log-likelihood, the prior on log(M/H) is not uniform (see R3-R6 in Sect. 6). Instead, we use a normal prior whose mean and standard deviation are informed by the imposed value.

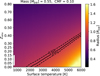

For free chemistry retrievals, we assume the same priors of the equilibrium chemistry retrievals except for log(M/H) and C/O since these two parameters do not apply. The mass fraction abundances of the chemical species are free parameters with a prior log(Xspecies) = 𝒰(−10, 0). For consistency, the joint interior-atmosphere retrievals use similar priors for those parameters that are relevant when bulk density data, age and spectra are combined as observables (see caption in Table 2). The reference pressure does not exist as prior in the joint retrievals because it is fixed to Pref = 1000 bar, where the interior-atmosphere interface is located. Similarly, as the planet radius is computed by the interior grid consistently, it does not require a prior in the joint retrievals. Finally, Table 2 shows that the prior on internal temperature is uniform between 0 and 2000 K. In the joint retrievals that include age as an observable, this prior is changed to 𝒰(0,500) K to improve convergence. This prior choice is further motivated by our self-consistent interior-atmosphere models (see Fig. A.1), which show that WASP-80 b's internal temperature does not exceed a few hundred Kelvin in the absence of extra heating sources. The age of WASP-80 b is approximately 1 Gyr, which corresponds to internal temperatures Tint = 100–300 K according to forward models, even in cloudy atmospheres (Poser et al. 2019; Poser & Redmer 2024). Internal temperatures above 900 K hinder convergence towards older ages in our joint retrievals, as they restrict the explored age range to 1-10 Myr.

Our retrievals also include offset parameters between a reference data set and the other data sets in the same geometry. Specifically, the NIRCam data set is our reference in transmission, introducing two free offsets between the NIRCam and STIS, and the NIRCam and WFC3 data sets. In emission, our reference data set is NIRCam F322W2. Thus, we use three free offsets: one for WFC3, one for NIRCam F444W, and one for MIRILRS. These offsets account for differences in instruments and data reductions, for which we adopted Gaussian priors, offsetdataset = 𝒩(0, 100) parts per million (ppm) in transit depth and planet-to-star flux in transmission and emission, respectively. Previous work report offsets of ~200 ppm between JWST and HST data sets (Lothringer et al. 2025), so a normal distribution with a standard deviation of 100 ppm is a reasonable offset prior in our retrievals.

5 Atmosphere spectrum retrievals

5.1 Transmission spectrum retrievals

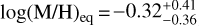

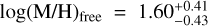

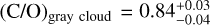

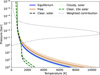

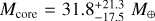

As a starting point for our transmission-only retrievals, we fit an equilibrium chemistry model. In our retrieval, WASP-80 b's atmospheric composition ranges from sub-solar to solar metallicity, and it is consistent with a solar C/O = 0.55 within 1.3σ. This retrieval obtains an atmospheric metallicity of  and

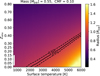

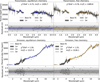

and  . Our C/O ratio agrees well with similar equilibrium chemistry retrievals by Wong et al. (2022, W22) and Bell et al. (2023, B23), whose 1σ estimates span C/O = 0.20–0.60 (see Fig. 1). In contrast, the equilibrium retrievals by previous work suggest that the atmospheric metallicity is super-solar, with M/H ≃ 3–10 × solar (B23) and M/H ≃25–100 × solar (W22). In summary, our equilibrium chemistry retrieval agrees with previous work on C/O ratio, but obtains a solar-like metallicity in contrast to their super-solar estimates.

. Our C/O ratio agrees well with similar equilibrium chemistry retrievals by Wong et al. (2022, W22) and Bell et al. (2023, B23), whose 1σ estimates span C/O = 0.20–0.60 (see Fig. 1). In contrast, the equilibrium retrievals by previous work suggest that the atmospheric metallicity is super-solar, with M/H ≃ 3–10 × solar (B23) and M/H ≃25–100 × solar (W22). In summary, our equilibrium chemistry retrieval agrees with previous work on C/O ratio, but obtains a solar-like metallicity in contrast to their super-solar estimates.

We also explore free chemistry retrievals to constrain the abundances of individual absorbing species. We obtain tight constraints on the mass fraction abundances of H2O and CH4,  and

and  , respectively. CO and CO2 abundances are poorly constrained, spanning more than four orders of magnitude both in our retrievals and B23. Our estimate for CH4 agrees extremely well with that obtained by B23 in their free chemistry retrievals. Our retrieved H2O mass fraction ratio is consistent within 1σ with B23's water abundance estimate.

, respectively. CO and CO2 abundances are poorly constrained, spanning more than four orders of magnitude both in our retrievals and B23. Our estimate for CH4 agrees extremely well with that obtained by B23 in their free chemistry retrievals. Our retrieved H2O mass fraction ratio is consistent within 1σ with B23's water abundance estimate.

Our free retrieval contribution function indicates that the abundances are probed at a pressure Ptransit ≃ 10−3 bar. Thus, we compared our free retrieved abundances to the expected abundances at the transit pressure from our equilibrium chemistry retrieval. We found that the free CH4 abundance is compatible with its expected equilibrium abundance within <2σ. In contrast, water is 4σ more abundant in the free retrieval than in equilibrium.

We estimated the overall atmospheric metallicity and C/O ratio from our free retrieved abundances and obtained  and

and  (shown in Fig. 1). This estimate agrees with the scenario presented by B23 in their free retrievals, in which WASP-80 b's atmosphere is super-solar and has a very low C-to-O ratio with

(shown in Fig. 1). This estimate agrees with the scenario presented by B23 in their free retrievals, in which WASP-80 b's atmosphere is super-solar and has a very low C-to-O ratio with  and (C/O)B23, free = 0.004±0.002.

and (C/O)B23, free = 0.004±0.002.

We adopted the equilibrium chemistry retrieval as our fiducial transmission-only model since it has the highest Bayesian evidence (see Table 3). Our free chemistry retrieval and previous analyzes indicate a super-solar metallicity, whereas our fiducial model suggests a sub-solar to solar composition. We explore whether this discrepancy could be explained by different cloud treatments by performing a new retrieval. This retrieval has in common with our fiducial model the equilibrium chemistry, but uses a cloud model that is different from our κcloud model (Eq. (10)). This is a simple cloud model that consists of a gray cloud deck with two free parameters. The first parameter corresponds to the pressure at which the cloud deck is located, Pcloud. This means that the cloud opacity is completely opaque at all wavelengths for P > Pcloud, which is similar to the cloud model assumed in B23. The second free parameter constitutes a haze factor, which scales the Rayleigh scattering opacity characteristic of hazes. With this cloud parameterization, we obtain an atmospheric metallicity and a C-to-O ratio that are super-solar:  and

and  . Thus, we demonstrated that for the particular case of WASP-80 b, the cloud treatment has a significant effect on the estimated composition, particularly the atmospheric metallicity and C/O ratio. Previous work have also found that cloud parameterization can impact the inference of atmospheric composition (Line & Parmentier 2016; MacDonald & Madhusudhan 2017; Fisher & Heng 2018; Lueber et al. 2024; Roy-Perez et al. 2025).

. Thus, we demonstrated that for the particular case of WASP-80 b, the cloud treatment has a significant effect on the estimated composition, particularly the atmospheric metallicity and C/O ratio. Previous work have also found that cloud parameterization can impact the inference of atmospheric composition (Line & Parmentier 2016; MacDonald & Madhusudhan 2017; Fisher & Heng 2018; Lueber et al. 2024; Roy-Perez et al. 2025).

We compared the cloud properties between our nominal equilibrium and free retrievals. All cloud parameters are similar, except for the cloud base pressure, as it is the cloud parameter with the narrowest constraints. The equilibrium retrieval tends to locate the cloud layer at pressures higher than the transit pressure, Pbase, eq = 0.1 to 100 bar (1σ); whereas the free chemistry retrieval locates the cloud base pressure at higher altitudes that are consistent with the transit pressure, Pbase, free = 1.5 × 10−3−3 bar. This suggests that clouds are a greater source of absorption in the free retrieval than the equilibrium one. Thus, in equilibrium chemistry, the opacity is dominated by the species absorption, namely CH4, as the C/O ratio is greater than the free retrieval estimate by ~0.4.

Finally, we compare the Bayesian evidence between the three models: (1) equilibrium chemistry; (2) free chemistry; and (3) equilibrium chemistry, with a gray cloud deck. The equilibrium chemistry model is preferred over the free chemistry one by ln(B12) = ln(Zl) − ln(Z2) = 5.9 and the gray cloud deck equilibrium model by ln(B13) = 12.8. The comparison of these models is not as straightforward as comparing nested testing to estimate the detection confidence of a particular molecule. In this case, the degrees of freedom is different between models, where the most complex models have more free parameters (see Table 3), and the comparison can be more sensitive to the choice of priors. Under this word of caution, we compared the Bayes factors of the two comparisons and estimate lower and upper limits for their confidence levels according to Schmidt et al. (2025) and Trotta (2008), respectively (see also Kipping & Benneke 2025, for a detailed discussion on how to avoid overestimation of confidence levels in Bayesian model comparisons). The first comparison, ln(B12) = 5.9 is equivalent to a confidence level of 1.5–4σ. Similarly, the second comparison ln(B13) = 12.8 corresponds to 1.5–5σ. Even if it is at low confidence, a sub-solar [M/H] with a solar C/O ratio and wavelength-dependent cloud extinction at low altitudes is preferred over a scenario with super-solar [M/H] with very low C/O ratios and high altitude clouds (see Fig. C.1 for the best fit and residuals).

|

Fig. 1 Comparison between our atmospheric composition estimates and previous work from transmission-only (upper panel) and emission-only (lower panel) retrievals. Previous work include Bell et al. (2023, B23, orange), Wong et al. (2022, W22, dark gold), and Wiser et al. (2025, Wi25, violet). The shaded area indicates the region forbidden by our interior-only retrievals at 4σ (see Sect. 6). |

Goodness-of-fit metrics for the three transmission spectrum retrievals.

5.2 Emission spectrum retrievals

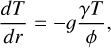

In the following, we explore retrievals for the emission spectrum only. Our emission equilibrium chemistry retrieval estimates an atmospheric metallicity of  and

and  . The emission-only free chemistry retrieval agrees well within 1σ with the emission-only equilibrium estimate,

. The emission-only free chemistry retrieval agrees well within 1σ with the emission-only equilibrium estimate,  and (C/O)emission, free = 0.24±0.12. Overall, the emission-only retrievals agree well in C/O ratio with our transmission-only retrievals. In contrast, the atmospheric metallicity in emission-only retrievals tends to be slightly super-solar, agreeing well with the free chemistry transmission retrieval (see both panels in Fig. 1).

and (C/O)emission, free = 0.24±0.12. Overall, the emission-only retrievals agree well in C/O ratio with our transmission-only retrievals. In contrast, the atmospheric metallicity in emission-only retrievals tends to be slightly super-solar, agreeing well with the free chemistry transmission retrieval (see both panels in Fig. 1).

We estimate the Bayes factor between the equilibrium and free chemistry emission-only retrievals: ln(B) = ln(Zfree) – ln(Zequiiibrium) = 1538.1 − 1537.0 = 1.1. This value of Bayes factor is well below 1σ, meaning that the emission spectrum alone does not show a preference for equilibrium over free chemistry and viceversa.

Figure 1 (lower panel) shows a comparison of our emission-only estimates and those of previous work. All five estimates agree well within uncertainties in an atmospheric metallicity that ranges between solar and 100× solar. The equilibrium retrievals in Wiser et al. (2025) and our work agree that the atmospheric metallicity is [M/H]~3–10× solar. However, our retrievals constrain C/O < 0.40, while Bell et al. (2023) and Wiser et al. (2025) obtain 1σ intervals C/O = 0.40–0.65. Our lower C/O estimate could be due to our assumption of equilibrium chemistry, while Wiser et al. (2025) consider a free vertical eddy diffusion coefficient, Kzz in their retrievals. Thus, their grid might allow for atmospheric models that have low abundances of carbon-bearing molecules (CH4, CO2, and CO) at moderately high Kzz values without requiring low C/O ratios. In addition, we report a weak correlation between C/O ratio and the offset between the MIRI LRS and NIRCam F322 data sets. For a zero value of this offset, we observe a higher C/O~0.4. Wiser et al. (2025) do not use offsets between the NIRCam and MIRI data sets, which may bias the C/O value to slightly higher estimates.

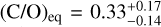

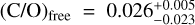

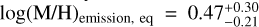

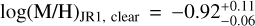

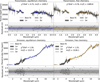

The emission retrievals also allow us to determine the thermal structure at high altitudes. Figure 2 shows the 1σ confidence regions estimated by both emission-only retrievals. The spectrally weighted contribution function is higher at pressures where the emission spectrum is more sensitive to the thermal structure, indicating the pressures that are probed by the data. These pressures are P = 10−3 − 1 bar, for which the thermal structure is well constrained with T = 700–1000 K. This temperature range is in excellent agreement with that estimated by Bell et al. (2023) and Wiser et al. (2025).

We overplot self-consistent models in our P–T diagram to compare to the retrieved profiles. These models correspond to the clear models provided by Mollière et al. (2017), which agree well with the retrieved profiles at the pressures probed by the emission data. In addition, we show one cloudy model that agrees well, which is model 1 in Table 2 from Mollière et al. (2017). This cloudy model assumes irregular grains via the distribution of hollow spheres (DHS), a standard settling parameter fsed = 3, and includes iron (Fe) clouds. We rule out cloud models with fsed < 1 and atmospheric cloud mass fractions Xmax > 3 × 10−5, as their temperatures (not shown) at pressures P = 1–0.1 bar and P = 10−2–10−3 bar are significantly colder and warmer, respectively, than our retrieved profiles.

|

Fig. 2 P–T profile of WASP-80 b as constrained by our two emission-only retrievals. The shaded region indicates the 1σ area of the retrieval, while solid lines correspond to the mean. We show self-consistent 1D models from Mollière et al. (2017) for comparison, including cloudy model 1 in their Table 2 (see text). The dotted gray line shows the contribution function from our emission-only retrievals. |

Mean and uncertainties of retrieved compositional parameters in the interior-only retrievals.

6 Interior retrievals

We ran a suite of six interior-only retrievals that take into account the observables traditionally used to characterize planetary interior structure. To assess the effect of each observable, we varied the number of observables included in the retrieval and, in the case of the atmospheric metallicity, we explored the effect of its assumed value. The atmospheric metallicity was not incorporated into the interior retrieval by including the spectrum in the log-likelihood: this approach is applied in Sect. 7 via Eq. (4.1). Instead, we treated the atmospheric metallicity as an independent observable parameter and fit it alongside mass, radius and age using a log-likelihood function with a prior. We considered two scenarios for the atmospheric metallicity: a sub-solar value derived from our transmission-only, equilibrium chemistry retrieval (fiducial), and a super-solar value from our transmission-only, free chemistry retrieval. Table 4 summarizes the observables and shows the mean and uncertainties of the retrieved compositional parameters.

In the retrievals that use a super-solar atmospheric metallicity (R4 and R6), the posterior distribution of the atmospheric metallicity does not agree with the imposed prior distribution. To quantify this discrepancy, we defined the metric |log(M/H)mean PDF – log(M/H)obs|, which quantifies the difference between the posterior mean and the observational mean, expressed in prior standard deviation units (or σ). A value of |log(M/H)mean PDF – log(M/H)obs| > 1σ indicates that R4 and R6 have difficulty fitting log(M/H) and the other observables simultaneously. This tension arises because the density of WASP-80 b is lower than that of a core-less (CMF = 0) planet with a super-solar envelope composition.

In the following, we discuss the maximum atmospheric metallicity allowed by the density of WASP-80 b. R6 shows that if the age is taken into account, the maximum possible metallicity is ~ 10 × solar. This is consistent with the mass-radius-age forward models where a planet with WASP-80 b's mean mass and log(M/H) = 1 requires to have no core (CMF = 0) to match its observed radius at its current age (see Fig. A.1). In the absence of external heat sources and a non-homogeneous interior in WASP-80 b, an atmospheric metallicity that is consistent with the bulk density cannot be [M/H]>10× solar at 1c, and [M/H]>30× solar at 4c. Thus, there is a discrepancy in [M/H] between our interior-only analysis, and our transmission-only, free chemistry retrieval as well as the estimates presented in previous work. We further discuss how free joint interior-atmosphere retrievals show degeneracies between envelope composition and chemistry in Sect. 7.

The retrievals that did not incorporate the atmospheric metallicity as an observable (R1 and R2), and those that use its sub-solar value (R3 and R5), can reproduce all observables within the 1σ uncertainties. This means that the retrieval can find forward models that are physical and fit the values imposed by the observational data. These four retrievals agree well in their retrieved compositional parameters, suggesting that the core mass fraction of WASP-80 b is CMF ~ 0.03–0.19 at 1σ. This CMF range is equivalent to a core mass Mcore = 5.2–33.2 M⊕. Its envelope metal mass fraction is low, with Zenv < 0.07 within 1σ. Thus, the total bulk metal mass fraction of WASP-80 b ranges between 0.10 and 0.15 with standard deviations of 0.05. We compare this estimate to the joint retrieval in Sect. 7 and discuss its implications for WASP-80 b's formation in Sect. 8.7.

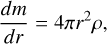

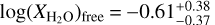

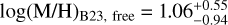

7 Joint interior-atmosphere retrievals

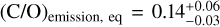

The joint interior-atmosphere retrievals presented in this section incorporate both spectra and bulk observables (mass, radius, age) into their likelihood function, as described in Sect. 4.1. In addition, the forward model consists of the coupled interior-atmosphere model described in Sects. 3.1.2, 3.2 and Appendix B. The suite of joint retrievals (JR; see Table 5) consists of six retrievals: two with transmission spectra (JR1, JR2), two with emission spectra (JR3, JR4), and two that combine both geometries (JR5, JR6). We assumed equilibrium chemistry across the suite of joint retrievals because the transmission-only retrievals show a preference for the equilibrium chemistry model (see Sect. 5.1). Additionally, we explored JR1 and JR5 as free chemistry retrievals. Table 5 shows a summary of the compositional parameter estimates (CMF, Zplanet, log(M/H), C/O) from joint retrievals. Furthermore, Fig. 3 shows a summary schematic of JR6, which we adopted as our fiducial joint retrieval (see Sect. 7.3).

Retrieved model parameters in the joint interior-atmosphere retrievals.

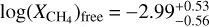

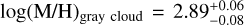

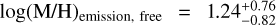

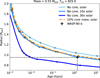

7.1 Bulk and atmospheric composition

The compositional parameters derived in the joint retrievals are compared in Fig. 4 with the interior-only retrievals (top panel: CMF and Zplanet) and the atmosphere spectrum retrievals (bottom panel: C/O and M/H). As the joint retrievals combine the observations used in the independent interior and atmosphere retrievals simultaneously, their estimates should be consistent with these. With the exception of JR5, joint retrievals agree within 2σ with the interior-only retrievals, as shown by their overlap in CMF-Zplanet parameter space (Fig. 4, top panel). JR5, which incorporate emission spectra without the age, tends to overestimate the CMF. We discuss the cause of this high-CMF estimate in Sect. 7.4.

The bulk metal and core mass fraction estimates align along the solar envelope line (dashed black line in Fig. 4). We compare the envelope composition estimates in the bottom panel. The joint retrievals that do not include emission spectra (JR1, JR2) retrieve a sub-solar atmospheric metallicity and a solar C/O ratio, consistent with the fiducial transmission-only retrieval. JR3-JR6, which include emission data with bulk properties and/or the transmission spectrum, obtain atmospheric metallicities and C/O ratios in excellent agreement with the emission-only retrievals (Fig. 4, bottom panel). These show that WASP-80 b has a subsolar C/O~0.10–0.20 and [M/H] = 1–20× solar. JR1 and JR2 (transmission) are compatible with solar C/O values, in contrast to the sub-solar C/O in the other joint retrievals.

Overall, we demonstrate that the joint retrievals that include emission spectra are consistent with the emission-only retrievals, while JR1 and JR2 are consistent with the transmission-only retrievals. We observe that the bulk composition derived in the joint retrievals are also consistent with the traditional interior-only retrievals, with the exception of JR5.

7.2 The M/H discrepancy and degeneracies in joint retrievals

We describe in Sect. 5.1 how the atmospheric metallicity derived from the free chemistry, transmission-only retrieval is strongly super-solar and incompatible with the interior-only retrievals that assume secular cooling. To explore this tension, we modified our joint retrieval JR1, which takes into account the transmission spectrum together with the mass as observables, as a free chemistry retrieval. This free chemistry retrieval, JR1*, tends to obtain a lower C/O ratio and higher atmospheric metallicity than its equilibrium counterpart. This decrease in C/O and increase in M/H is consistent with the behavior we observed in the transmission-only retrievals, as the free chemistry retrieval exhibits a preference for a water-rich atmosphere and high-altitude clouds. In contrast to the transmission-only, free retrieval, the atmospheric metallicity has an upper 1σ limit of log(M/H) = 0.89, which is below the 1σ-upper limit derived by the interior-only analysis of 10 × solar. This is caused by the coupling between the reference radius used to generate the transmission spectrum and the interior model. Thus, the coupling between temperature, chemistry (metal content) and radius in joint retrievals effectively demonstrates that there is a degeneracy between the envelope composition (M/H and C/O) and chemistry.

7.3 Clouds

We obtained very similar estimates on the cloud parameters between each joint retrieval, and these and the transmission-only retrievals in Sect. 5.1. For reference, we included the cloud base pressure in Table 5. Most estimates are consistent with a cloud base located at P > 0.1 bar at 1σ. The most data-complete joint retrieval, JR6, suggests that clouds are present at high altitudes P ~ 10−4 bar within 1σ.

In Sect. 5.1, we note the degeneracy between the opacity of carbon- and oxygen-bearing molecules and cloud opacities in spectra. From the least degenerate joint retrieval (JR6), we can conclude that a sub-solar C/O ratio together with an atmospheric metallicity [M/H] = 1–10× solar and high altitude clouds is the most likely scenario for WASP-80 b, as this is compatible with all spectral data sets and the planet bulk density simultaneously, under the assumption of equilibrium chemistry.

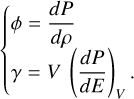

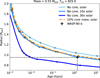

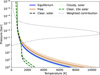

7.4 Thermal structure

We show in Fig. 5 the thermal structure profiles constrained by all our joint retrievals (except for JR4) that incorporate emission spectra. These profiles agree well with those derived by the emission-only retrievals (see Sect. 5.2) at pressures P < 1 bar. As demonstrated in Fig. 2 by the contribution function, these are the pressures probed by the emission spectrum. At higher pressures (P = 1–1000 bar), the constrained thermal structure is very dependent on the assumptions and data included in the retrieval. In the following, we discuss how these impact the temperature in the deep envelope and the bulk metal mass fraction.

Including the age in the likelihood improves the constraints on the internal temperature. This can be seen in the central panel of Fig. 5, and by comparing the internal temperatures in Table 5. When the age is not taken into account, the internal temperatures have wide uncertainties (ΔTiat ~ 100–200 K), and their mean values tend to be high (Tint > 200 K). As WASP-80 is a moderately old system (0.99 Gyr), the age's effect in the retrievals is to decrease the internal temperature to Tint = 50–150 K, with uncertainties as low as ΔTint = 12 K in the least degenerate case, JR6. This range of internal temperatures is consistent with the interior-only retrievals that account for the age (RI, R5–R6) and the interior forward models (see Fig. A.1).

Independently of the geometry considered, adding the age to the likelihood reduces the mean value of the retrieved bulk metal mass fraction and the CMF (see Fig. 4, top panel). As discussed above, the age of WASP-80 b decreases the internal temperature, which entails a lower temperature at 1000 bar. Since the interior temperature follows an adiabatic profile, a lower Tsurf correlates to a colder interior. A colder interior adiabat increases the density of the envelope, which lowers the retrieved CMF and Zplanet values.

The inclusion of transmission spectra in the joint retrievals tends to increase the inferred temperature in the deep envelope and reduce its uncertainties. This effect can be seen when comparing Tint in JR1 and JR3 (Table 5), and in the left panel of Fig. 5. When comparing JR1 (transmission without emission) and JR3 (emission without transmission), we find that JR3 yields lower internal temperatures than JRI. JR3 is more sensitive to the temperature at 1 bar – T(P = 1 bar) = 700–900 K (see also Sect. 5.2) –, favoring lower Tint. Similarly, when both transmission and emission are considered (JR5), the temperature increases compared to JR3 (no transmission; see the left panel of Fig. 5). In Sect. 5.1, we noted that the fiducial transmission retrieval tends to retrieve low C/O ratios. We discussed that this could be due to the assumption of equilibrium chemistry, where low C/O ratios and high deep atmospheric temperatures are required to increase the abundance of H2O relative to CH4. Including the transmission spectrum along with the emission spectrum in a joint retrieval further constrains the abundances of H2O and CH4, which drives model in JR5 toward a higher internal temperature (Tint = 500 K). This high deep atmospheric temperature increases the planet radius, yielding a core and bulk metal mass fraction in JR5 that is the highest of all joint retrievals (see Fig. 4, top panel).

Finally, we explored the effect of assuming equilibrium chemistry on the retrieved thermal structure. We compare the P–T profile of JR5 (emission plus transmission, without age) between equilibrium and free chemistry (JR5*). As discussed above, the equilibrium chemistry model requires high temperatures to reproduce the abundance of H20 observed in the spectra. Thus, relaxing the equilibrium assumption in the free chemistry retrieval leads to a decrease in the temperature at high pressures, as shown in the left panel of Fig. 5. The thermal structure of JR5* is compatible with a self-consistent, clear solar model with Tint = 100 K at 1σ, which is the internal temperature predicted by the age of WASP-80 b in the absence of extra heating.

The decrease in deep atmospheric temperature between JR5 and IR5* has a significant impact on the retrieved CMF. In Fig. 4 (top panel), we can see that the CMF decreases from 0.50 (JR5) to ~0.20 (JR5*). Since JR5* (free chemistry) is more consistent with the other retrievals than JR5, it represents a more conservative scenario than JR5. This is especially the case if WASP-80 b's internal temperature is decoupled from its age due to additional heating sources. Thus, we adopted JR5* as our fiducial retrieval, together with JR6. The latter represents a scenario without extra heating sources where age and Tint are coupled.

|

Fig. 3 Mean forward model from one of our two fiducial interior-atmosphere joint retrievals, JR6, of WASP-80 b. This model corresponds to a core mass fraction (CMF) of 0.02, an atmospheric metallicity of M/H = 2.75 × solar, C/O = 0.12, and Tint = 134 K. Panel a: schematic cross section of the planet; layer thicknesses are to scale. The atmosphere corresponds to pressures below 1000 bar. Panel b: P–T profile of the atmosphere (light blue) and interior (blue and teal). Panel c: transmission spectrum for this model, with the three observed transmission datasets shown for comparison. Panel d: emission spectrum for this model, compared against the four observed emission datasets. Panel e: interior metal mass fraction profile (Z; black) and H/He mass fraction as functions of normalized radius. The atmospheric region (P < 1000 bar) is indicated in light blue. Panel f: atmospheric mass mixing ratios of the molecular species comprising the metals (P < 1000 bar). The region highlighted in orange indicates the pressure range probed by emission spectra, as calculated from the contribution function. |

|

Fig. 4 Top panel: core and bulk metal mass fraction 1σ estimates obtained by our joint retrievals (JR1-JR6). Joint retrievals that take into account the age have triangle markers. Interior-only retrievals (R1–R3 and R5) are shown as colored boxes for comparison. Bottom panel: atmospheric metallicity and C/O ratio estimates from our suite of joint retrievals. Spectra-only estimates are displayed as colored boxes for comparison. |

7.5 Precision in bulk metal mass fraction, Zplmet

In the following, we compare the CMF and Zplanet estimates shown in Table 5 to discuss how the different observables and data sets can improve the precision in bulk metal mass fraction. For this comparison, our reference uncertainty of the bulk metal mass fraction is ΔZplanet = 0.05, which is the uncertainty of the most-data complete of the traditional, interior-only retrievals, R5-R6.

We note that all three joint retrievals that incorporate the age – JR2, JR4, and JR6 - have bulk metal mass fraction uncertainties of ΔZplanet = 0.02–0.03. This means that a joint retrieval together with age reduces the uncertainties from 0.05 to 0.02 – a factor of 1/2. However, in the absence of an age estimate, a joint retrieval does not guarantee an improvement of the retrieved bulk metal mass fraction relative to the traditional, interior-only retrievals. For example, R3 has a ΔZplanet, R3 = 0.05–0.07, while its joint counterpart in transmission (JR1) shows a similar uncertainty ΔZplanet, JRI = 0.07. Furthermore, the joint counterpart in emission (without transmission), JR3, obtains a larger uncertainty of ΔZplanet, JR3 = 0.16. This is due to the degeneracy between temperature in the deep atmosphere (Tsmt) and CMF, which is mostly solved by the age.

8 Discussion

Wilkinson et al. (2024) conducted a similar analysis using the MCMC method and a coupled interior-atmosphere model on WASP-39 b's transmission spectrum. There are three key differences between their analysis and this work. First, we included a condensate opacity source to simulate the effect of clouds. Second, we did not weight the importance of the bulk density observables (i.e. mass, radius, and age). Third, our retrievals incorporate data in both the near-infrared (nIR) and optical. We examined how the cloud treatment, weighted likelihood, and the spectral wavelength coverage affect the inferred atmospheric and bulk compositions in atmosphere-only and joint retrievals in Sects. 8.1, 8.2, and 8.3, respectively.

Furthermore, we discuss the possible presence of external heating sources and disequilibrium chemistry in WASP-80 b in Sects. 8.4 and 8.5. Finally, we conclude by outlining our model uncertainties and caveats (Sect. 8.6) and by discussing the implications of WASP-80 b's atmospheric and bulk composition for its formation pathways (Sect. 8.7).

8.1 Sensitivity to cloud treatment

The omission of cloud modeling in joint retrievals with transmission spectra may lead to biases in the inference of atmospheric composition and bulk metal mass fraction. In traditional, transmission-only retrievals, the atmospheric metallicity and the cloud top pressure (Pbase) are often correlated (Benneke & Seager 2012; Welbanks & Madhusudhan 2019; Fisher & Heng 2018). To study the impact of not including clouds in our modeling, we run our JR1 retrieval without clouds. We obtain CMFJR1, clear = 0.09±0.05,  and

and  . If we compare these to the fiducial JR1 retrieval, we find that the uncertainties in atmospheric metallicity and C/O ratio are reduced by a factor of 3 and 5, respectively. This bias arises from the reduced parameter space caused by eliminating the degeneracy between chemical abundance and cloud pressure. The CMF mean is decreased from 0.14 to 0.09, while their uncertainties are reduced by a factor of 2. We conclude that not accounting for clouds in joint interior-atmosphere retrievals biases not only the inference of atmospheric composition, but also the inferred CMF and Zplanet. These biases include lower C/O ratio and CMF mean values, and significantly reduced uncertainties for all compositional parameters, by factors of 2–4.

. If we compare these to the fiducial JR1 retrieval, we find that the uncertainties in atmospheric metallicity and C/O ratio are reduced by a factor of 3 and 5, respectively. This bias arises from the reduced parameter space caused by eliminating the degeneracy between chemical abundance and cloud pressure. The CMF mean is decreased from 0.14 to 0.09, while their uncertainties are reduced by a factor of 2. We conclude that not accounting for clouds in joint interior-atmosphere retrievals biases not only the inference of atmospheric composition, but also the inferred CMF and Zplanet. These biases include lower C/O ratio and CMF mean values, and significantly reduced uncertainties for all compositional parameters, by factors of 2–4.

|

Fig. 5 P–T proflies of WASP-80 b as constrained by four of our joint retrievals. The shaded regions indicate the 1, 2, and 3σ regions of the retrieval, while solid lines correspond to the mean. Black lines highlight self-consistent models from Mollière et al. (2017); Acuña et al. (2024) of a clear atmosphere with solar composition at Tim = 100 (dashed) and 500 K (dotted) for comparison. Left: the difference between JR3 and JR5 shows the effect of adding the transmission spectrum to JR3, which incorporates emission spectra plus the mass and radius. The transmission spectrum reduces significantly the uncertainties in thermal structure. Center, comparing JR6 and JR5 allows us to study the effect of including the age to the retrieval. JR6 is the most data-complete of the joint retrievals, since it incorporates both transmission and emission, plus the mass and age. If the age is removed (JR5), the temperature in the deep atmosphere increases. Right: comparison between JR5 and JR5*, which illustrates the effect of assuming equilibrium chemistry in the joint retrieval. If we relax the assumption of equilibrium chemistry in JR5 by changing to a free chemistry model (JR5*), the temperature decreases in the deep interior. |

8.2 Effect of weighted likelihood

The second key difference from previous work is that we do not scale the terms associated with the bulk density observables in Eq. (11) (dbull) by a weighting factor (wj). Wilkinson et al. (2024) fix wj to a constant value that equalizes the importance of these observables with that of the spectrum. Under this assumption, the weighting factor must be equal to the total number of points in the spectrum. A value wj > 1 is equivalent to reducing the uncertainties of the observables, because the factor  in Eq. (11) can also be written as

in Eq. (11) can also be written as  . In volatile-rich planets, reducing mass uncertainties does not improve the precision of inferred bulk composition since the envelope mass contributes a negligible fraction to the total mass (Otegi et al. 2020). However, a reduction in radius and age uncertainties significantly improves the precision of the inferred CMF and Zplanet (Müller & Helled 2023). Consequently, using a weighting factor to give more importance to the bulk density observables relative to the transmission spectrum leads to an underestimation of the uncertainties of core and bulk metal mass fraction. The use of weighting factors adopting a prior wj < 1 may be justified if the flux uncertainties in the transmission and emission spectra are expected to be underestimated. This is not the case for WASP-80 b, as the transmission and emission spectra were obtained contrasting different data reduction pipelines in Bell et al. (2023) and Wiser et al. (2025), showing robustness in their approach.

. In volatile-rich planets, reducing mass uncertainties does not improve the precision of inferred bulk composition since the envelope mass contributes a negligible fraction to the total mass (Otegi et al. 2020). However, a reduction in radius and age uncertainties significantly improves the precision of the inferred CMF and Zplanet (Müller & Helled 2023). Consequently, using a weighting factor to give more importance to the bulk density observables relative to the transmission spectrum leads to an underestimation of the uncertainties of core and bulk metal mass fraction. The use of weighting factors adopting a prior wj < 1 may be justified if the flux uncertainties in the transmission and emission spectra are expected to be underestimated. This is not the case for WASP-80 b, as the transmission and emission spectra were obtained contrasting different data reduction pipelines in Bell et al. (2023) and Wiser et al. (2025), showing robustness in their approach.

8.3 Effect of wavelength coverage in atmospheric spectra

In contrast to WASP-39 b's joint retrievals by Wilkinson et al. (2024), our analysis incorporates both nIR and optical transmission spectra. Transmission spectra retrievals exhibit a normalization degeneracy, in which the molecular abundances relative to H are degenerate with the absolute normalization of the spectrum. The normalization depends on the reference pressure, Pref. This degeneracy can be broken if the spectrum is sensitive to Pref through pressure broadening or collision-induced absorption (CIA). The transmission spectrum contains information about these processes when it spans a wide wavelength range in the nIR, such as that provided by the combined HST and IWST datasets used in our analysis (Fisher & Heng 2018). Additionally, optical data further reduce degeneracies between the chemical abundances and the cloud top pressure (Fairman et al. 2024). The optical wavelength range provides valuable information about condensates in transmission retrievals (Welbanks & Madhusudhan 2019).

We further compare our results to those of Morel et al. (2025), who use reflected light data in traditional, atmosphere-only retrievals. They provide and analyze a dataset of WASP-80 b emission spectra between 0.6 and 3 μm, measured with JWST's NIRISS/SOSS. Their retrievals rule out log(M/H) > 2 and C/O > 0.6, which is in good agreement with our joint retrievals. Their self-consistent cloud modeling concludes that the NIRISS/SOSS data are compatible with cloud species such as chromium (Cr[s]), sodium sulfide (Na2S), potassium chloride (KCl) and Zinc sulfide (ZnS). Morel et al. (2025) also consider the presence of tholins in the atmosphere of WASP-80 b. In this scenario, they estimate a low tholin production rate (<10−11.5 g cm−2 s−1). Tholins tend to cool the envelope due to a high UV extinction, as observed in the sub-Neptune GJ1214 b (Nixon et al. 2024) and as predicted in cold, directly imaged planets (Morley et al. 2015). Our fiducial retrieval (JR6) is compatible within uncertainties with a cool atmosphere (see Fig. 5, central panel). Additionally, our atmosphere-only and joint retrievals further support the presence of condensates in transmission, (see Sects. 5.1 and 7), consistent with the scenario proposed by Morel et al. (2025).