| Issue |

A&A

Volume 702, October 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A135 | |

| Number of page(s) | 24 | |

| Section | The Sun and the Heliosphere | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555609 | |

| Published online | 24 October 2025 | |

Solar wind temperature measurements

1

Christian Albrechts University at Kiel, Kiel, Germany

2

Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie, Toulouse Cedex 4, France

⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

21

May

2025

Accepted:

6

August

2025

Context. The solar wind has been an active research area since the beginning of the space age and the available measurements of its basic properties, i.e. solar wind density, velocity, and temperature, have fundamentally shaped our understanding of the heliosphere. Meanwhile, the data from various solar wind instruments show significant systematic differences.

Aims. We characterise systematic errors in these basic solar wind properties that are caused by instrumental limitations and put them in the context of solar wind studies.

Methods. To this end, we investigated the limitations that arise from the finite resolution of state-of-the-art solar wind instruments, namely the Proton Alpha Sensor (PAS) and the Solar Probe ANalyzer for Ions (SPAN-I). We defined two models, a virtual detector model of PAS and a more general further idealised detector with finite resolution. Virtual measurements of Maxwell-Boltzmann velocity distribution functions were compared to observations. The detailed effects of the instrumental resolution on the solar wind density, velocity, and temperature were analysed.

Results. We identify an unphysical direction dependence of the observed temperatures in data from PAS and SPAN-I. We show that both models can reproduce and explain this apparent direction dependence of the temperature observed by PAS. While the solar wind densities and the absolute values of the solar wind velocity are well determined, the directions of the solar wind velocity suffer from systematic errors and more importantly the majority of all available solar wind temperatures are systematically overestimated to varying degrees. These systematic errors are a compulsory consequence of the finite resolution of an instrument and are further enhanced by the detailed instrumental responses. In addition, limited instrumental sensitivity and field of view lead to a systematic and variable underestimation of the temperature. All observed temperatures are affected by one or more of these effects. Our results are transferable to all solar wind instruments.

Conclusions. Our results have far-reaching consequences for heliophysics. Firstly, we provide guidelines to adapt requirements for future solar wind instruments. These guidelines stem from our finding that the resolution of existing solar wind instruments is insufficient to capture all relevant underlying physics. Secondly, we discuss the impact of our results for past and future studies in various aspects of heliophysics. Even long-standing fundamental findings need to be reconsidered in the light of our results.

Key words: plasmas / instrumentation: detectors / solar wind

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the space age in 1957, measurements of the solar wind have been used in countless studies. These studies have revolutionised our understanding in numerous topics, reaching from the large-scale structure of our heliosphere, through medium-scale structures such as corotating interaction regions and coronal mass ejections, down to the very small scale of local wave-particle interaction in an unique almost collisionless plasma. But although much scientific progress has been achieved, many detailed processes of the generation and the evolution of the solar wind are not yet well understood. To shed light on these open questions, the focus of the scientific community has moved to study shorter timescales and smaller spatial scales Marsch (2006). For example, already with Helios, different temperatures had been observed parallel and perpendicular to the magnetic field direction (Marsch et al. 1982). Such temperature anisotropies are interpreted as the result of wave-particle interactions (Marsch 2006) and are expected to drive plasma instabilities (Yoon 2017), and various theoretical and simulation studies offer possible explanations (e.g. Lazar et al. 2022). The common fundamentals for these research topics are accurately observed temperatures that provide the same accuracy for all directions and all bulk solar wind velocities.

However, there is ample evidence that observations of solar wind properties by different instruments show systematic differences beyond the individually calculated uncertainties. Often a cross-correlation approach is used to characterise the differences or to even cross-calibrate datasets (e.g. King & Papitashvili 2005; Ipavich et al. 1998). While a comparison can be insightful, cross-calibration of instruments ignores and obfuscates the root cause of the systematic differences. Further, it relies on various assumptions; for example, that one of the instruments reflects the ground truth. Moreover, the influence of the instrumental resolution on the fundamental solar wind parameters, i.e. solar wind bulk density, velocity, and temperature, to our knowledge have not yet been conclusively investigated. Very recently in an independent concurrent study, Nicolaou et al. (2025) investigated the difficulties of recovering particle Velocity Distribution Function (VDF)s due to the limited energy resolution and limited angular resolution for a virtual detector. Our study combines a data-driven investigation with a theoretical perspective on the measurement of solar wind properties. In fact, measuring solar wind with sufficient accuracy is a challenging task. Solar wind instruments have to cover bulk flow energies that are in the kilo-electronvolt range. Simultaneously, thermal energies that are in the electronvolt range have to be resolved. While the technological progress over the decades is mainly reflected in the better time resolution of solar wind instruments, the energy and angular resolution has remained similar (see Table 1 in Podesta 2015). Podesta (2015) investigated the influence of small non-thermal features on obtained solar wind bulk velocities. They find that the resolution of existing solar wind instruments is about one order of magnitude too low to resolve such features, which leads to uncertainties in the determined bulk velocities.

Here, we analyse the influence of the instrumental resolution on the solar wind bulk density, velocity, and temperature under the assumption of thermal velocity distributions. We find that the provided instrumental resolution, which is often just given by (i) the grid spacing of the instruments bins or (ii) a simple estimation of the broadness of the response function in a given channel, is in fact insufficient to describe the actual resolution of solar wind instruments. For an accurate evaluation of the instrumental resolution, it is necessary to utilise the detailed 3D response function of an instrument to characterise the resolution dependent on different velocity distribution functions. Even if the velocity distribution function is known, such detailed analyses cannot provide a fixed resolution but rather a range of systematic errors of the measurements.

Furthermore, here we restrict ourselves to thermal velocity distributions, that are the easiest use case that should be reliably resolved by solar wind instruments. Any systematic limitations that occur for thermal velocity distributions are even more problematic for all studies focusing on non-thermal features; for example, temperature anisotropies. Section 2 describes the relation between solar wind velocity distributions and the solar wind bulk properties that are commonly used to characterise the solar wind. A general overview of what is actually measured by solar wind instruments is given in Section 3. In this study, we chose two solar wind instruments, the Proton Alpha Sensor (PAS) and the Solar Probe ANalyzer for Ions (SPAN-I), as test cases. They are part of two of the latest solar missions, Solar Orbiter (SolO) run by the European Space Agency (ESA), and Parker Solar Probe (PSP) run by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). We compare their observations with theoretical predictions based on their respective instrumental resolutions. Both instruments are described in Section 3.1. Solar wind temperatures recorded by both instruments show evidence of insufficient instrumental resolution, shown in Section 3.2. In Section 4, a Virtual Detector based on PAS (VPAS) is presented. This VPAS is used to analyse artificial thermal velocity distributions and the results are compared with PAS data. Theoretical limits on the accuracy of measured temperatures are derived in Section 5, based on a further idealised instrument. These limits are compared to the results of Section 4.2. Differences between data from PAS and SPAN-I that have been taken under similar conditions are discussed with respect to their different instrumental resolutions in Section 6. All findings are summarised and conclusions for the design of future solar wind instruments and for past and future studies that build on the available solar wind measurements are drawn in Section 7.

2. Solar wind velocity distributions and bulk properties

Routinely the bulk solar wind is characterised by three properties: the proton density, velocity, and temperature. Depending on the capabilities of the different sensors, velocity and temperature are provided in one, two, or three dimensions. Independent of the instrument, none of the three parameters can be measured directly. Rather, the phase space distribution of protons is sampled and the parameters are derived from these distributions. The phase space distribution, δn(r, mv, t), is 7D, wherein r, and mv are the coordinates in position and momentum space, respectively, and t is the time. For non-relativistic solar wind protons, velocity space can be used instead of momentum space. In the following, we use Cartesian coordinates and indices x,y,z denote the three directions in position, and velocity space, respectively.

For in situ measurements the position, r, naturally is given by the position of the instrument (i.e. the spacecraft position). The resolutions in v and t depend on the capabilities of the instrument.

The position r and time t, dependent density, nsw, bulk flow speed, vsw, and thermal velocity, vth, can be calculated as the 0th, 1st, and 2nd order moments of the distribution in velocity space,

The y and z components of vth(r, t) are defined analogously to Eq. (3). Often the thermal velocity is used to describe the temperature of the solar wind, but also temperatures in Kelvin and electronvolt are widely used. These relate to the thermal velocity as

with mass, m, elementary charge, e, and Boltzmann constant, kB, and as for Eq. (3) the y and z components of the vector T are not shown here. The conversion from electronvolt to Kelvin is given by e/kB or 1 eV ≈ 11 605 K. From now on, we adopt the same notation as used in the PAS and SPAN-I datasets and refer to the kinetic temperature in electronvolt also simply as T instead of kBT. Also note that throughout this study all temperatures and thermal velocities are solar wind properties, but for the sake of readability we omit the subindex, sw, for temperatures and thermal velocities but not for the density and bulk velocity.

The moments are well defined and make no a priori assumptions about the nature of the underlying distributions. But in turn they do not provide any information on the shape of the underlying distributions. This information is lost and the interpretation of each moment as the most likely respective value is only valid for symmetric distributions. The meaning of the 1st and 2nd moments is ambiguous. The most commonly used alternative to moments is a fit of an a priori-defined model VDF to the observed VDF. This fit approach is also affected by the instrumental resolution and in addition requires strongly limiting assumptions in the form of the model VDF. In practice, observed VDFs are often interpolated (e.g. De Marco et al. 2023). However, the interpolation introduces additional assumptions and resulting uncertainties. For instance, even for the same model VDF the determined solar wind properties can differ depending on the degree of a polynomial interpolation. Further, if the response functions of neighbouring bins overlap, as is the case, for example, for PAS and SPAN-I (as is discussed in the following sections), a meaningful interpolation is even more difficult to define. Thus, although our considerations are also relevant for other approaches, in the following we focus on solar wind properties derived as moments of the VDF.

Often the most fundamental assumption of a thermalised distribution is made. In this case, the derived moments can be used to describe the distribution at place r and time t by a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution,

with the scalar property,

However, often non-thermal features are observed. One typical non-thermal feature is a beam that is aligned with the local magnetic field direction. A second non-thermal feature is a temperature anisotropy with respect to the local magnetic field direction. To study these, an additional measurement of the local magnetic field, B, is required, and the measured distributions have to be transformed into a magnetic field aligned frame first.

Table A.1 provides an overview on the meaning of the various super- and sub-indices used in the following sections. In particular, Table A.1 summarises under which conditions redundant indices are omitted.

3. Solar wind measurements

Although the detailed design and measurement technique of solar wind instruments varies, there is one common feature that is shared by most (if not all) of them. Incoming particles are filtered by their ratio of energy-per-charge (EpQ), by means of electrostatic deflection. For an ion species with mass, m, and a charge, q, each given EpQ step, (E/q)i, i ∈ {1, …, NEpQ}, corresponds to a unique energy, q (E/q)i = Ei, q. Thus, an electrostatic analyser implements a velocity filter:

Stepping through i ∈ {1, …, NEpQ} yields 1D velocity spectra. Many instruments allow one to further discriminate one or two inflow directions, and thereby yield 2D or 3D velocity spectra. The individual sensors differ most in their respective methods to discriminate the inflow directions. On three axes stabilised spacecraft typically ion optics are used to determine directionality. On spinning spacecraft a mechanical collimator can be utilised to determine the direction perpendicular to the spin axis.

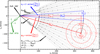

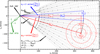

While some instruments utilise other designs such as Faraday cups (e.g. Case et al. 2020; Bosqued et al. 1996; Bridge et al. 1977), here we focus on the most commonly used so called top-hat design (e.g. Schwenn et al. 1975; Bame et al. 1992; McFadden et al. 2008; Reme et al. 1997; Owen et al. 2020; Livi et al. 2022; Galvin et al. 2008). However, our approach also holds for all designs utilising electrostatic analysers and in principle also for all instruments with a finite resolution. Top-hat electrostatic analysers are composed of two stacked spherical segment shaped plates with slightly different curvature radii. In addition to the EpQ stepping as described above, this design allows one to measure the azimuthal direction. Due to the ion optical properties of the top hat design, the position of the ion at the exit of the electrostatic analyser can be used to determine the incoming azimuthal angle, ϕ, in the plane of the detector for Nϕ values of ϕ. A second electrostatic deflection can be used to determine Nθ values of the elevation angle, θ, perpendicular to this plane. With electrostatic analyser and deflection voltages that are stepped through, the instant Field of View (FoV) covers only a small part of the full velocity space. Thereby, it takes a total scan time, tscan, to scan velocity space at NEpQ ⋅ Nϕ ⋅ Nθ points (vx, vy, vz)i, j, k wherein i, j, k denote a combination of an instrumental EpQ step, an azimuthal angle bin, and an elevation angle bin. As an example of an instrumental velocity space coverage, Fig. 1 illustrates the 2D velocity space coverage of PAS for its central elevation step. The black dots mark the central position of instrumental bins, (vx, vy, vz)i, j, k, which are scanned by the instrument. The instrument integrates the velocity space density around these central positions from a certain volume with a response, δℛi, j, k(v, φ, ϑ). The boxes around each centre illustrate an idealised situation where the volumes of adjacent bins do not overlap, i.e. within the FoV the complete velocity space is uniquely covered. For this case the resulting uncertainty can be expressed by the finite grid spacing of the bin centres, we call this uncertainty ΔGS. But there is also a second measure for the uncertainty in v, the width of δℛi, j, k(v, φ, ϑ), which is often given as Full Width Half Maximum (FWHM). We call this uncertainty due to the response width, ΔRW. In the literature, both ΔGS and ΔRW or a mix of both are referred to as instrumental resolution. Often it is not clear which of both is actually used. In Fig. 1 only ΔGSv is illustrated, ΔRWv is addressed beginning in Sect. 4.

|

Fig. 1. Example of a 2D cut of a velocity phase-space scan is shown. The black dots mark the central position of instrumental bins (vx, i, j, k, vy, i, j, k) that are scanned, with i ∈ [1, …, NEpQ], j ∈ [1, …, Nϕ], NEQP as the number of energy-per-charge (EpQ) steps and Nϕ as the number of azimuthal bins, the angle of inflow bin ϕj of the jth azimuthal bin, and its corresponding bin width ΔGSϕj. As an example for a solar wind instrument the calibration values of the central elevation bin k = 5 of PAS for protons are used here and in Fig. 3. Note that we explicitly differentiate between the instrumental properties (ϕ, θ), and the measured angles (φsw, obs and ϑsw, obs). All instrumental characteristics are shown in black including the utilised Frame of Reference (FoR). Dots illustrate the shells centred at the origin, i.e. in the Spacecraft Reference Frame (SRF), which are scanned by the electrostatic analyser. Each 5th electrostatic analyser step is enlarged for clarity. The shape of each instrumental bin is illustrated with a concentric grid. The instrumental resolution in velocity space becomes coarser with increasing shell radius. In red, an example of a thermalised Maxwell-Boltzmann VDF (see Eq. (6)) is depicted. Shown are the bulk-flow vector relative to the instrument vsw, its components, vsw, x, vsw, y, and the thermal velocity vth. The corresponding 1σ, 2σ, and 3σ environments of the distribution are indicated in light red. In blue, measurement quantities are shown: the absolute value of the solar wind bulk velocity |vsw|, the y component of the thermal speed vth, y, and the corresponding thermal angle αy. The two relevant FoRs are depicted in the left part of the figure: the SRF in black and the Radial-Tangential-Normal Frame (RTN) frame in green. Therein, the tangential components points in the direction of the spacecraft eigenvelocity. |

In the radial direction, the uncertainty ΔGSvi is defined by the spacing of (E/q)i. By design the uncertainty ΔRW(E/q)i is proportional to (E/q)i, and thus in the radial direction the uncertainty ΔRWvi is proportional to vEpQ, i. To obtain a wide and continuous phase space coverage the (E/q)i are typically spaced logarithmically. This means that both ΔRWv and ΔGSv in radial direction of velocity space become coarser with increasing vEpQ. This scaling behaviour transfers also to the velocity resolutions in the φ and ϑ directions, as the angular grid spacings ΔGSϕ and ΔGSθ do not depend on vEpQ1. Fig. 1 also illustrates how a thermalised Maxwell-Boltzman VDF would be seen by such an instrument. The angular width under which the distribution is seen by the instrument scales not only with the thermal velocity vth but also with vsw. As a measure for the angular width of a VDF in the Spacecraft Reference Frame (SRF) we define the angle, α,

as the angle under which the full 1σ-environment of the VDF would be seen by the instrument. The angle α can be directly compared with the angular resolution of instruments. Such an angle can be calculated in all three Cartesian directions. We call these angles αx, αy, αz, respectively. Fig. 1 provides an example for the angle in the y direction, αy. We emphasise that this angle is here only calculated in SRF and only to investigate effects of the instrumental resolution. Fig. B.1 illustrates how α depends on temperature and solar wind velocity.

Similarly to the y and z directions, which are expressed with the angles φ and ϑ, the radial direction can also be expressed on an angular scale. With respect to vEpQ, i, we define the angle, γ,

In analogy to the angular resolutions, in Table 1 and in the following sections the resolution in EpQ, (E/q)i + 1/(E/q)i, is also expressed as an angle, ΔGSγ, in velocity space, that is defined as

γ provides a useful instrumental scale for the velocities in the x direction relative to vEpQ, i and αx can be directly compared to ΔGSγ.

Instrumental properties and resolutions of PAS, and SPAN-I, respectively.

3.1. Instruments: PAS and SPAN-I

We chose two solar wind instruments as examples: PAS, which is part of the Solar Wind Analyser (SWA) on SolO, and SPAN-I, which is part of Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP) suite on PSP. Both utilise a top-hat design, as is described in Section 3. The details of the sensors are described in Owen et al. (2020) and Livi et al. (2022).

The two instruments have differences in their design that are relevant to consider. PAS moments can be affected by an alpha contamination, while SPAN-I has an additional time-of-flight section that allows one to distinguish directly between protons and alphas. Although the FoV of SPAN-I is wider than that of PAS, SPAN-I’s position behind PSP’s heat-shield frequently leads to incomplete coverage of the VDF in the y direction (φ direction). For PAS, L2 moment-data is available through the Solar Orbiter archive ESAC (2020) and for SPAN-I, L3 moment-data is provided via Kasper et al. (2020).

According to the metainformation provided along with the moments2, instrumental capabilities are summarised in Table 13. As the data cadence does not reflect the integration times directly, the scan times, tscan, in Table 1 are given by the times needed to complete a single phase space scan according to the instrument papers (Owen et al. 2020; Livi et al. 2022). The velocity space resolution ΔGSv in all directions of both sensors is comparable to similar solar wind instruments (see e.g. Podesta 2015), but both have an outstanding temporal resolution: A (full) scan is completed in less than one second compared to typical durations of 40–120 seconds (Schwenn et al. 1975; Bame et al. 1992; McComas et al. 1998; Galvin et al. 2008).

Both datasets allow one to investigate the effects of the instrumental resolution in the SRF according to Fig. 1, i.e. in a Frame of Reference (FoR) with the instrument at the origin. As outlined in Sect. 3, the instrumental velocity space coverage is best described by equatorial spherical coordinates, vEpQ, ϕ, θ, but moments are given in Cartesian coordinates. According to Fig. 1, we converted the observed first moments, i.e. the observed velocity vectors, vsw, obs, into absolute values, vsw, obs,

observed azimuthal inflow angles, φsw, obs,

and observed elevation inflow angles, ϑsw, obs,

with Eqs. (5) and (9). Kinetic temperatures Tx, obs, Ty, obs, Tz, obs provided in electronvolt were converted to angles

These coordinates are directly comparable to the actual velocity space scan of the instrument as illustrated in Fig. 1. For small angles, φsw, obs, ϑsw, obs, the respective resolutions, ΔGSγ, ΔGSϕ, ΔGSθ, determine the effective resolution in Cartesian x, y, z directions.

3.2. Observations: PAS and SPAN-I

In this section, we show observations from two instruments, PAS and SPAN-I, in two different directions ( and

and  , respectively) as an example. Panels b) and e) of Fig. 2 present 2D histograms of observed

, respectively) as an example. Panels b) and e) of Fig. 2 present 2D histograms of observed  versus observed

versus observed  and observed

and observed  versus observed

versus observed  in the instrumental frame for measured solar wind speeds 345 km/s < vsw < 355 km/s. The right hand axis transforms T to α using Eqs. (5) and (9). An arc-like structure with the base of the arches directly related to the centres of the instrumental angular bins that are marked by solid black vertical lines is clearly visible in both histograms. The dashed black lines mark the positions in the middle between two angular bins and their height is determined by the grid spacing of two adjacent bins ΔGSϕPAS and ΔGSθSPAN − I, respectively. For each arc, both position and height of the top of the arcs match the central position between two bins and the angular width of the respective instrumental bin, respectively. The distributions of observed flow angles shown in panels c) and f) peak at small absolute values; that is, close to the radial direction where the instrumental resolution in ϕ and θ direction governs the resolution in the y and z directions, respectively (compare Fig. 1). The 1D histograms of the observed temperatures shown in panels a) and d) peak at thermal angles close to the distance between instrumental bins, which is basically the instrumental resolution ΔGSϕPAS and ΔGSθSPAN − I, respectively.

in the instrumental frame for measured solar wind speeds 345 km/s < vsw < 355 km/s. The right hand axis transforms T to α using Eqs. (5) and (9). An arc-like structure with the base of the arches directly related to the centres of the instrumental angular bins that are marked by solid black vertical lines is clearly visible in both histograms. The dashed black lines mark the positions in the middle between two angular bins and their height is determined by the grid spacing of two adjacent bins ΔGSϕPAS and ΔGSθSPAN − I, respectively. For each arc, both position and height of the top of the arcs match the central position between two bins and the angular width of the respective instrumental bin, respectively. The distributions of observed flow angles shown in panels c) and f) peak at small absolute values; that is, close to the radial direction where the instrumental resolution in ϕ and θ direction governs the resolution in the y and z directions, respectively (compare Fig. 1). The 1D histograms of the observed temperatures shown in panels a) and d) peak at thermal angles close to the distance between instrumental bins, which is basically the instrumental resolution ΔGSϕPAS and ΔGSθSPAN − I, respectively.

|

Fig. 2. Observed temperatures over the observed inflow direction for observed solar wind speeds between 345 and 355 km/s for 7 July 2020–30 November 2023 for PAS and for 20 April 2021–27 July 2023 for SPAN-I. Panel b): 2D histogram of PAS azimuthal temperatures |

The size and shape of these arc-like structures in PAS and SPAN-I temperatures are clearly related to the respective instrumental resolution. The direction-dependent lower bound on the observed temperatures represented by the arc-like structures is not expected for a physical process in the solar wind. If such a structure were physical, we would expect it to be independent of the direction in the SRF and to be the same in different instruments and not to adapt itself to the respective instrumental resolution. In the following section we present a virtual detector of PAS, to further investigate the influence of the instrumental resolution on derived solar wind moments.

4. Calibration-accurate virtual detector based on PAS

To understand the influence of the full instrumental response function on the derived solar wind parameters we designed a Virtual Detector based on PAS (VPAS). In this section, we put a special focus on the temperatures that are as the 2nd moment particularly sensitive to the measurement uncertainties. The VPAS is based on general considerations that are outlined in Appendix C and incorporates the most detailed 3D calibration of the PAS flight spare model that is available. VPAS is idealised in the sense that we assume that the 3D calibration perfectly and completely describes the instrumental responses4. The calibration describes the response functions, δℛi, j, k(E/q, φ, ϑ)5, for ions with energy, E, and charge, q, in spherical coordinates (compare Eq. (C.3)),

𝒜j, k(φ, ϑ) is an area that only depends on the direction multiplied with the measurement time. ℰj, k((E/q)/(E/q)i) scales the area to an effective area along the radial axis (see also Appendix C).

Fig. 3 gives an example of the calibration data for a selection of angular bins. In panel c) the 2D angular responses for nine central bins are shown, panels b) and d) show the corresponding 1D angular responses. The 1D energy response, which is the same for all (E/q)i, is shown in panel f). In analogy to panels b) and d) the 1D angular response for successive (E/q)i are shown in panel g), where the abscissa shows the angles γ with respect to the ith EpQ step. VPAS numerically integrates the product of a given artificial input VDF and the full 3D response functions for each instrumental bin i, j, k, which result in expectation values for the number of counts, μi, j, k, in each bin, according to Eq. (C.5). These artificial measurements can be evaluated in the same way as the data from the real PAS instrument and moments can be calculated in exactly the same manner. Moments were derived from the artificial measurement by the following procedure. First, for each instrumental bin the expected counts, μi, j, k, were converted to partial densities following Eq. (C.2)

|

Fig. 3. Part of the full 3D instrumental response of PAS and VPAS. Panel c) shows the response functions of nine angular bins in the centre of the PAS FoV as contour lines. The respective indices are specified in the legend at the top of the figure. Panels b), and d), give reduced 1D response functions for the same bins. Panel f) completes the 3D instrumental response with the energy response relative to the ith (E/q)i step. The blue arrows in panel c) indicate the cut along which the VPAS input angles were scanned for panels a) and e). Panel g) give relative 1D energy responses for neighbouring steps i − 2, i − 1, i, i + 1, i + 2. For VPAS the normalised differential energy responses are interpolated. Panels a), e), and h) show the angles αz, αy, and αx, respectively, over the input angles ϑsw, in, φsw, in, and γsw, in, with solid lines and over the output angles ϑsw, out, φsw, out, and γsw, out with dashed lines. The output angles are derived based on the virtual measurement, whereas the input angles refer to the properties of the simulated solar wind distribution that is measured by VPAS. The dash-dotted lines indicate the respective input angle. Black arrows mark one maximum and one minimum in panels a) and e) and connect to the corresponding 1D response functions in panels b) and d). The shaded grey area in panel c) indicates the scan range used in Fig. 5. |

with conversion factors,  . With these discrete Δni, j, k and the bin centre velocities, vi, j, k, moments were derived by summation to obtain the output density, nsw, out:

. With these discrete Δni, j, k and the bin centre velocities, vi, j, k, moments were derived by summation to obtain the output density, nsw, out:

the output bulk speed, vsw, out:

and the output thermal speed, vth, out, with the x component (and analogous y, z components):

with the number of energy bins, NEpQ, the number of azimuth bins, Nϕ, and the number of elevation bins, Nθ. These derived moments can be directly compared to the moments of the input distributions. Such a comparison is discussed in detail in Sects. 4.1 and 4.2.

VPAS differs from PAS in so far as the response function  is exactly known and the total bin responses

is exactly known and the total bin responses  are derived from them (Eq. (C.4)). For any real instrument, the response can only be determined up to a certain precision, which introduces additional systematic errors. Thus, the forward (artificial measurement) and the backward (inversion of measurement back to differential densities) steps in VPAS are done under idealised conditions.

are derived from them (Eq. (C.4)). For any real instrument, the response can only be determined up to a certain precision, which introduces additional systematic errors. Thus, the forward (artificial measurement) and the backward (inversion of measurement back to differential densities) steps in VPAS are done under idealised conditions.

In addition, our scenario differs from the real PAS measurements in so far that the input VDF is known. For this study we exclusively investigate the simple case of thermal VDFs (see, Eq. 6). The input VDFs are therefore fully characterised by nsw, in, vsw, in, and vth, in, i.e. their first three moments. We evaluated the input VDF only in a 5σ environment centred around the bulk flow velocity. Because we used expectation values for the artificial measurements and the inversion instead of discrete counts, additional effects that arise from the limited instrumental sensitivity and statistical uncertainties are not reflected in VPAS. The parameter nsw, in of the input VDF can be chosen arbitrarily. As is outlined in Sect. 3 the instrumental angular resolutions ΔGSγ, ΔGSϕ, and ΔGSθ do not depend on vsw, in. Thus, the other input parameters, i.e. vth, in and the direction of vsw, in, can be represented with the angle αin = 2arctan(vth, in/vsw, in) and the flow directions γsw, in6, φsw, in, and ϑsw, in. Analogously to the input parameters, the output parameters vsw, out, and vth, out can be expressed by the angles αx, out, αy, out, and αz, out and γsw, out, φsw, out, and ϑsw, out.

In summary, our approach allows us to investigate the influence of the instrumental resolution under idealised conditions:

-

The VPAS measures with exactly the calibration that is used to invert the measurement of VPAS. Note that for PAS and generally for all instruments the calibration approximates the real instrumental properties.

-

By taking expectation values instead of discrete counts no statistical uncertainty is considered, especially nsw, in can be chosen arbitrarily. We therein assume an instrument with a good enough instrumental sensitivity to observe the VDF over a full 5σ environment.

-

The input thermal VDFs are well known, and are fully defined by the inflow directions γsw, in, φsw, in, ϑsw, in, and instead of vth, in we use the angle αin. Because all the angles and the instrumental grid-spacing in all directions scale with (E/q)i, a fixed reference velocity vEpQ, i can be chosen arbitrarily, i.e. the results in this section are valid for all solar wind velocities within the FoV.

As is indicated in Table A.1, in the following we omit redundant indices, i.e. the FoR which is always SRF in Sects. 4 and 5.

Results for simulated VDFs with input angles αin = αx, in = αy, in = αz, in = 1° coming in from different directions are shown in panels h), e), and a) of Fig. 3. Shown are the resulting output angles αx, out, αy, out, αz, out in the x, y, z directions over the inflow angles in γsw, in, φsw, in, and ϑsw, in direction. In each case, the respective other two angles were set to 0°. Dashed lines show αx, out, αy, out, and αz, out over the respective input directions, γsw, in, φsw, in, and ϑsw, in, and solid lines over the direction derived from the output of VPAS, γsw, out, φsw, out, and ϑsw, out, respectively. For each direction, the angles αx, out, αy, out, and αz, out do not match the respective input αin values, as the input angle is chosen smaller than the instrumental resolution in this scenario (dash-dotted lines).

For φsw, in and ϑsw, in, very small αy, out and αz, out are derived for inflow directions where only one instrumental bin has a response (see black arrows connecting the base of the arcs with the respective response for the inflow direction in Fig. 3). The highest αy, out, αz, out are observed for directions where the instrumental response is similar for two neighbouring bins (see black arrows connecting the top of the arcs with the respective response for the inflow direction in Fig. 3). Also, the resulting output flow directions are pushed towards the instrumental bin centres (compare solid and dashed blue lines). These arc-like structures in the φsw, in and ϑsw, in directions, which are also seen in the data (compare Fig. 2), are a striking feature that is highly unlikely to be a natural phenomenon in the solar wind. In the following, we argue that this feature can be explained with the 1D responses in the corresponding directions. As can be seen in Figs. 3b) and d), around the bin centres only a single bin has a non-zero response. If we imagine a very narrow, beam-like VDF with a very small temperature and if this beam-like VDF comes from an inflow direction close to a bin centre (see black arrows connecting the base of the arc to the respective instrumental response in Fig. 3), only a single instrumental bin can detect particles from this VDF. As a result a kinetic temperature of 0 eV would be derived. If a similar beam-like VDF is detected exactly between two bin centres, i.e. at the top of an arc, both bins have a similar response. As a result, a high kinetic temperature would be derived for such a cold, beam-like VDF. This situation corresponds to the top of the arc-like structures in Figs. 3a) and e). Thus, for VDFs with temperatures smaller than the grid spacing of the instrument, a derived temperature is ill-defined.

In contrast to the other two directions, for γsw, in, the αx, out are more or less constant independently from the inflow direction. This effect is a result of the strongly overlapping response functions shown in panel g) of Fig. 3. Here, at each position, three instrumental bins have a non-zero response to incoming particles. The resulting values for the first moment, in this case the absolute value of the bulk velocity, are very close to the input values (dashed and solid lines are on top of each other in panel h)), but the 2nd moment, that is the angles αx, out, are systematically overestimated. For example, a delta beam results in αx, out = 2.09°, which corresponds to a temperature Tx ≈ 1 eV (see Fig. B.1) for vsw = 500 km/s (see Fig. B.1).

As is illustrated with the example angle αin = 1° in Fig. 3, VPAS is not able to resolve such angles, i.e. temperatures, which are below the instrumental resolution ΔGSγ, ΔGSϕ, and ΔGSθ, respectively. In the following subsections, we generalise this example to a range of values for αin.

4.1. VPAS and PAS data

We now apply the virtual detector VPAS to investigate the influence of the full instrumental response function on the resulting αy, out for input angles −45° < φsw, in < 25°, at γsw, in = ϑsw, in = 0° systematically and compare the results with measurements. Analogously to Fig. 2, Fig. 4 shows a 2D histogram of the observed angle αy, obs over the observed inflow φsw, obs angle based on PAS data. Note again, all quantities are shown in SRF and not Radial-Tangential-Normal Frame (RTN) since the transformation to RTN obscures but not removes the effects discussed here and α is only meaningfully defined in SRF. Utilising αy instead of the temperature, measurements at all solar wind speeds can be directly compared. Analogously to panel e) of Fig. 3 the coloured solid lines in Fig. 4 show αout over φsw, out for VPAS, while the corresponding αin are marked with dashed coloured lines. There are two major effects to be seen:

|

Fig. 4. Two-dimensional histogram of observed angles, αy, obs, observed by PAS from 7 July 2020 to 30 November 2023 over the determined inflow direction, φsw, obs (valid data with a quality factor of 0 only). Each column of the 2D histogram in panel b) is normalised to its respective maximum. The bins have a fixed size of 0.1° ×0.1°. 1D histograms of the observed angles, αy, out, (Panel a) and the determined inflow directions. φsw, out, (Panel c) are based on the same bin size, respectively. In addition, panel b) includes results from VPAS. For input angles αin ∈ {1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19}° (horizontal dashed lines), the resulting output angles αy, out are given with solid lines in the same colour. 99.89% of all Ntotal = 15 476 959 valid data with a quality factor of 0 are shown here, the remaining 0.11% have αy, obs > 20°. |

Firstly, for small αy, in the same arc-like structures as in Fig. 3 can clearly be seen; these are a direct result of the limited angular resolution. This shows that VPAS and PAS cannot resolve temperatures in the y direction corresponding to angles αy below the instrumental resolution ΔGSϕ.

Secondly, with increasing input αy, in the results become less dependent on the input direction. But, for all αy, in, αy, out is overestimated as long as the distributions are fully inside the FoV. Only at the edges of the FoV where parts of the distribution are not covered by the instrument, αy, out underestimates αy, in. For the highest angle in Fig. 4, αy, in = 19 eV, the VDFs are broad enough that the complete FoV in φsw direction is affected by these edge effects. Thus, in many configurations of VPAS and observations of PAS the finite grid spacing directly leads to an overestimation of the solar wind proton temperatures. From the 1D distribution of observed αy, obs shown in panel a) one can see that ≈98.4% of all observations are below the dashed green line in panel b), i.e. in the range where the majority of temperatures are systematically overestimated.

In the remainder of this section, we describe an additional feature in Fig. 4 that is outside the focus of this study. The red region in panel b), i.e. the maxima of the relative frequencies of occurrences of αy, obs, also show a pattern with respect to φsw, obs. If this pattern in αy, obs had a physical cause, this would indicate that the solar wind is hotter the further the in-flow direction deviates from the most frequently observed φsw, obs, which happens to be close to an instrumental bin centre. While the pattern shows a minimum in αy, obs at φsw, obs ≈ 3°, to both sides a peak- or plateau-like structure is visible. On the right side, close the edge of the instrumental FoV at φsw, obs ≈ 20° the pattern shows a decrease in the observed αy, obs for higher φsw, obs. This matches the expectation from VPAS, i.e. the VDF is broad enough that parts of the VDF are not observed. Surprisingly, the pattern looks similar on the left side, i.e. left of φsw, obs ≈ −15°. In this region, a cut-off effect from a limited FoV is not expected yet. Considering that a small fraction of the observations occurs in this region, the detailed shape of the pattern in this region could be dominated by individual solar wind streams. In summary, this additional pattern cannot be completely explained by VPAS. It is beyond the scope of this study to assess the extent to which this pattern is due to underlying physical processes in the solar wind or is caused by instrumental effects. In the following, we focus on the arc-like structures and the aforementioned systematic over- and underestimation.

4.2. VPAS: Systematic influences on derived moments

As mentioned in the previous section, Fig. 4 already includes virtual measurements with VPAS for the φsw direction. These are derived for ϑsw = 0° and for a fixed speed. The 2D instrumental response functions shown in panel c) of Fig. 3 indicate that the results for αy can be expected to also slightly depend on ϑsw, as the response functions in φsw direction are not independent from ϑsw.

Now, we extend our approach to all three directions and consider the 0th, 1st, and 2nd moments. To quantify the systematic influence of the instrumental response functions on the derived moments we scanned the inner FoV of PAS; that is, −10° < φsw, in < 0° and −5° < ϑsw, in < 5°. This range, indicated with a rectangular shaded black area in Fig. 3, has been chosen to include the most abundant measured flow directions (compare panel c) of Fig. 4 for φsw, in). For all configurations, i.e. combinations of input direction φsw, in, ϑsw, in and angle αin, the results for all parameters are summarised in Fig. 5. In each panel, the range of deviations (ratios in panels a), c), d), e), and differences in panel b)) between input and output parameter depending on αin are shown. In this section, we still assume an instrument with sufficiently good instrumental sensitivity to be able to observe the input VDF over a full 5σ interval. The effects of a limited FoV and limited instrumental sensitivity are discussed in Sect. 5.

|

Fig. 5. Over- and underestimation of the 0th (Panel a)), 1st (Panels b) and c)), and 2nd moments (Panels d) and e)) over the respective input angles αin as determined by VPAS. In panels a)–e), the shaded areas represent the full range of results for all considered input configurations. Solid lines correspond to the respective minima and maxima and dots mark the tested αin. Panel e) gives a zoom-in of panel d). In panels a)–e), three regimes (i), (ii), (iii) are indicated with (fuzzy) black vertical lines. Vertical dashed coloured lines indicate the respective grid spacing, ΔGSγ, ΔGSϕ, and ΔGSθ. Panel f) shows the cumulative fraction of occurrence of the angles observed by PAS from 7 July 2020 to 30 November 2023 (valid data with a quality factor of 0 only). A total of 15 476 959 observations is included here. The range of temperature ratios at the regime boundaries in panel e) is translated with Eq. (15) into output angles αout. Shaded coloured regions in panel f) mark the resulting ranges of αout. |

The results for the density nsw are shown in panel a). The shaded red area marks the full range of the ratios nsw, out/nsw, in for all tested configurations. The results can be roughly split into three regimes. In the first regime (i), for αin below the instrumental grid spacing (ΔGSϕ ≈ ΔGSθ ≈ 5°, compare Table 1) the ratio shows a variability ±15%. In the second regime (ii), 5° ≲αin ≲ 11.5°, the density is very well resolved. Further, in this regime, the variability of the results over all tested configurations is small, ≈2%; however, the density is also slightly overestimated by ≈2%. In the next regime (iii), for αin ≳ 11.5°, a systematic decrease in the determined density is observed. At these temperatures already parts of the VDF are outside the FoV of the instrument.

In panel b) the differences in the flow directions, φsw, out − φsw, in and ϑsw, out − ϑsw, in, respectively, are shown. The same three regimes can be determined as for the density. Below 5° (regime (i)) the directions are off by up to ≈1°. As discussed before in the context of Fig. 3 the output flow angles are pushed to the centres of the instrumental bins due to the directional responses. In regime (ii), which is up to αin ≈ 11.5°, both angles are well resolved. In the third regime (iii), above αin ≈ 11.5° in ϑ direction, parts of the distribution are cut off by the FoV (compare Table 1), which leads to a systematic shift of the determined flow angles and to the previously discussed decrease in density. In φsw, in direction, this effect starts to become visible at higher values of αin ≈ 15° than for the ϑsw, in direction.

For the bulk velocity shown in panel c) a small systematic overestimation between ≈0.3 − 1% is observed for αin ≲ 11.5° (regimes (i), (ii)). From that point on, a slight systematic increase in the determined bulk velocity can be seen. This effect can easily be understood by imagining the situation sketched in Fig. 1 for a hotter distribution. For such a hot VDF, systematically parts of the VDF at smaller velocities, i.e. slower than the bulk flow, are cut off by the FoV. This results in an overestimation of the bulk velocity.

The results for the three temperatures are shown in panel d). Not surprisingly the three regimes that have been visible in the 0th moment and the flow directions are also clearly visible in the 2nd order moments. Below the instrumental resolution, in regime (i), systematic influences on the temperatures are strong. In the y and z directions, temperatures can be as much as two orders of magnitude over- and for very cool distributions even underestimated. Temperatures in the x direction are up to one order of magnitude overestimated and no underestimation occurs in this regime for this component. As was discussed before, the differences between the x direction on the one hand and the y and z directions on the other hand, can be explained by the different instrumental directional responses (compare panel g) to panels b) and d) in Fig. 3). The effect of the limited instrumental FoV can be seen in the z direction. In regime (iii), above αin ≈ 11.5°, the temperatures start to be systematically underestimated due to the instrumental cut off at the edge of the FoV. However, the most surprising and striking finding is the behaviour of the temperature in the regime (ii) in-between, which can be seen best in panel e) that shows a zoom in of panel d) with a linear axis: all temperatures are systematically overestimated in this regime. Here, we assumed an instrument with a good instrumental sensitivity. As discussed in Sect. 5, a limited instrumental sensitivity introduces an additional source of underestimation for the temperatures.

Further, in these artificial measurements, the input VDF is isotropic. Nevertheless the measured temperatures always indicate strong anisotropies, simply because the instrumental limitations in terms of grid-spacing driven resolution and limited FoV are not the same for the different directions. We emphasise that we find no range where temperatures are determined without systematic errors. This observation has important implications, for example, for all temperature anisotropy studies. If the measurement is rotated into a magnetic field aligned coordinate system, this effect is compounded and for the same isotropic VDF different apparent temperature anisotropies would be measured for different magnetic field directions.

Panel f) puts the results of VPAS in the context of how frequently the different temperature regimes are observed with PAS. To this end, the variability of the temperature ratio at the regime borders is translated into a range of angles for each direction with Eq. (9). The resulting ranges are indicated with shaded green, blue, and orange areas in panel f). In addition, panel f) shows the cumulative sums of PAS observations in all three directions. This shows that for all three directions, regime (i), which exhibits severe overestimation of temperatures, is expected in 15–20% of all PAS observations. About 65 − 70% of all PAS observations fall in regime (ii), for which significant and direction dependent overestimation is expected based on VPAS. Thus, the deliberations of this section are highly relevant for the majority of PAS measurements and the majority of the observed temperatures are systematically overestimated.

5. Theoretical limits of a finite resolution detector

With VPAS, in the previous section an instrument with a well known calibration has been investigated. Now, we further idealise our virtual detector to investigate the influence of a finite resolution, i.e. a finite grid spacing. In detail, the measurement errors of idealised box-shaped response functions on measured temperatures under the assumption of thermal velocity distributions are examined. We refer to this as the Finite Resolution Detector (FRD) in the following. As we show in this section and Appendix E this is equivalent to the question of at how many equidistant points a standard normal distribution has to be sampled to determine the 2nd moment reliably.

The mathematical description and numerical details of this model are outlined in Appendix E. The analysis is based on a 1D model with an infinite number of bins, i.e. the FoV is unlimited and the measured distribution is not cut7. In this section, we express the velocity, v, in units of the thermal velocity, vth, in, as w = (v − vsw, in)/vth, in with vsw, in = 0. The FRD is defined by its bin spacing with respect to the width of the simulated distribution, i.e. the number of bins per sigma NBpS = 1/Δw with Δw as the constant distance between two consecutive bin centres wi and wi + 1. The response,  , of the ith bin wi is set to

, of the ith bin wi is set to

i.e. an idealised box-shaped response is given. This model is valid for all thermal distributions without loss of generality (w.l.o.g.) and by definition exactly reproduces the density, i.e. nsw, in = nsw, out. The only degree of freedom of the input VDF is the inflow direction, wmin, with respect to the instrumental bins, which is defined by the position of the closest bin centre to the centre of the VDF. The model can be evaluated for different NBpS and for different inflow directions wmin. I.e. for wmin = 0, the bulk flow exactly matches one of the instrumental bin centres, and for wmin = ±Δw/2 the bulk flow lies exactly between two bins.

Panels a) and b) of Fig. 6 illustrate how an input 1D Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution given by Eq. (E.2) (in red), is scanned by the FRD. In panel a) NBpS = 0.5 and wmin = 0.2Δw, and in panel b) NBpS = 1.0 and wmin = −0.3Δw have been chosen as examples. The horizontal dashed blue lines show the resulting partial densities calculated according to Eq. (E.9). The resulting velocity distribution according to the moments calculation using Eqs. (E.10)–(E.12) are shown with solid blue lines.

According to Eq. (E.2), our input parameters are nsw, in = 1, wsw, in = 0, wth, in = 1. The resulting moments are nsw, out = 1, wsw, out = 0.004, wth, out = 1.150 (Panel a)), and nsw, out = 1, wsw, out = 0.000, wth, out = 1.0418 (Panel b)). As expected from Eq. (E.10), the density is determined exactly in both cases. The error of the bulk velocity measurement is 0.4%, and smaller than 0.05% for the thermal velocity vth for panels a) and b), respectively. However, the corresponding errors in temperatures are given by  , which is 32.5% and 8.3% for panels a) and b), respectively. The error of the bulk velocity basically stems from wmin, i.e. how symmetric the distribution is sampled. Naturally this error propagates into the 2nd moment. However, this is not the main source of error for the 2nd moment. Although the densities Δni are integrated correctly over the bins, the bin centres wi are not the centres of gravity of the VDF in each individual bin. Thus, the assumption that the bin centres, wi, that go into Eq. (E.12) represent the centre of gravity of the measurements in this bin is violated for a Maxwellian distribution. This assumption would only hold for VDFs that are symmetric to the bin centres within each bin. For the case of a thermal distribution, the monotonically decreasing density in the flanks of the distribution naturally leads to an overestimation of the temperature.

, which is 32.5% and 8.3% for panels a) and b), respectively. The error of the bulk velocity basically stems from wmin, i.e. how symmetric the distribution is sampled. Naturally this error propagates into the 2nd moment. However, this is not the main source of error for the 2nd moment. Although the densities Δni are integrated correctly over the bins, the bin centres wi are not the centres of gravity of the VDF in each individual bin. Thus, the assumption that the bin centres, wi, that go into Eq. (E.12) represent the centre of gravity of the measurements in this bin is violated for a Maxwellian distribution. This assumption would only hold for VDFs that are symmetric to the bin centres within each bin. For the case of a thermal distribution, the monotonically decreasing density in the flanks of the distribution naturally leads to an overestimation of the temperature.

As was described above, the FRD is only restricted by its finite bin width, and thus the resulting moments derived from its artificial measurements only depend on NBpS and wmin, i.e. the temperature (vth, in) and the inflow direction (vsw, in). This dependency is discussed in Sect. 5.1. The additional effects of a limited FoV (such as those seen for VPAS and SPAN-I) and of a limited sensitivity are addressed in Sects. 5.2 and 5.3, respectively.

5.1. Influence of finite resolution

To investigate the errors caused by the finite resolution of a detector systematically, the moments were computed for different NBpS. For each NBpS, inflow directions in −Δw/2 ≤ wmin ≤ Δw/2 were evaluated. Since for a detector with unlimited instrumental sensitivity, the errors of the 1st moment are already well below 1% of vth, in, in this section we focus on the errors of the 2nd moment, or more precisely on the ratio  . The ranges of derived temperature ratios are presented in blue in Fig. 6c).

. The ranges of derived temperature ratios are presented in blue in Fig. 6c).

|

Fig. 6. Scaled differential densities in panels a) and b). In red, a standard normal distribution with zero mean and σ = 1 is shown. Dashed black lines mark bin boundaries for two grid spacings: a) NBpS = 0.5, b) NBpS = 1. FRD results are presented in blue. Bin integrated mean values (steps) and the distribution determined from a moment calculation (line) are shown. Blue and red crosses mark the values at the bin centres. In panel c), the ratios Tout/Tin of the respective FRD over NBpS are shown in blue. The results for Ty, out/Ty, in of the VPAS are included in orange. The αin axis on the top of panel c) is scaled to approximately match the scale of NBpS. The dashed lines mark the NBpS values from panels a) and b), respectively. Coloured horizontal lines in panels a) and b) mark three effective thresholds, e.g. FRDLS(10−1) in brown. For these three thresholds and for the FRD panel d) shows the density ratio nsw, out/nsw, in, panel e) gives the velocity difference relative to the thermal speed (vsw, out − vsw, in)/vth, in, and panel e) provides the temperature ratio Tout/Tin in the same scaling as panel c) (but with a lower upper limit). |

Below NBpS ≈ 0.5, even the idealised FRD is not capable of resolving temperatures. For NBpS > 0.5, the unavoidable errors due to finite resolution decrease from ≈33% at NBpS = 0.5 over ≈8% at NBpS = 1.0 to smaller than 1% at NBpS = 2.9. For the design of future instruments, we therefore suggest defining the requirements such that NBpS ≥ 2.9 is ensured for the temperatures of interest.

In addition to the FRD results, the results of Ty, out/Ty, in for VPAS (see Fig. 5) are shown in orange in Fig. 6c). The abscissa is scaled by a factor of 1/(2ΔGSϕ) to approximately match NBpS, under the assumption of the average resolution of PAS from Table 1. Note that compared to Fig. 5, Fig. 6 covers a larger range of αin. The errors of VPAS follow the trend of the FRD results in the range 0.5 ⪅ NBpS ⪅ 1 where VPAS does not suffer from incomplete coverage of the VDFs but at a higher level and with a larger spread. This behaviour can be explained well by the fact that VPAS does not fulfil the FRD assumptions of non-overlapping uniformly spaced bins and constant phase space coverage,  . The overlapping bins of PAS effectively reduce the temperature resolution and increase the measurement error. Thus, the FRD qualitatively reproduces the results of VPAS and thereby verifies that the finite resolution is indeed the source of the temperature overestimation.

. The overlapping bins of PAS effectively reduce the temperature resolution and increase the measurement error. Thus, the FRD qualitatively reproduces the results of VPAS and thereby verifies that the finite resolution is indeed the source of the temperature overestimation.

5.2. Influence of limited field of view

For NBpS ⪆ 1 the VPAS results differ from the FRD results. This effect can be understood by retracing the effect of a limited FoV based on the examples shown in panels a) and b) of Fig. 6. A limited FoV would cut off the VDFin (red curve) at a fixed value, i.e. w = 3. This leads to fewer bins that contribute to the moment calculation (bins above w = 3 are outside the FoV and have an expectation value of zero). In addition, the expectation value in the bin that contains w = 3 is reduced. The 0th and 2nd moments are therefore underestimated (compare Eq. (3)). Since the effect of the limited FoV is asymmetric (depending on the position of the VDF relative to the FoV), the 1st moment is more strongly affected than by the other effects discussed in this study.

The magnitude of the effect of the limited FoV and the αin at which it is starting to contribute to the overall systematic error is of course driven by the extent of the FoV. This extent typically differs even between the angular directions of a given instrument, as can be observed in Fig. 5. Here, the temperatures in the z direction for VPAS are starting to become underestimated for smaller αin than in the y direction due to the smaller FoV in z direction. This inhibits the comparability of different temperature components measured by the same instrument. A comparison between different instruments each with different FoVs has therefore to be done even more cautiously.

In conclusion we suggest that the design of the requirements of future instruments should acknowledge this effect. Thus, we call for sufficiently large FoVs to prevent these avoidable systematic errors.

5.3. Influence of instrumental sensitivity

The only limitation of the FRD is the finite width of its bins and its results only depend on NBpS and wmin, i.e. the temperature (vth, in) and the inflow direction (vsw, in). To investigate the impact of a limited sensitivity of an instrument, i.e. the capability of resolving small densities in a given grid spacing, the scenario of the FRD is modified in this section. The FRD is based on expectation values and thus does not depend on the density nsw, in, i.e. the sensitivity is unlimited. This means that even the smallest signals are taken into account by the FRD. But every real instrument has a lower and an upper detection limit. For PAS-like instruments, these limits are the lowest and highest number of counts that can be recorded. Therein, the lower limit is well defined by a single count. Other instrument also have a limits. For example, for Faraday cups these are determined by the lowest currents above the noise level and the highest currents that can be measured. In addition, these small signals (i.e. small number of counts or signals close to the noise level) carry systematic uncertainties due to discretisation and large statistical uncertainties. While the latter two effects are not covered in this work (in part since they are largely dependent on the detailed instrument properties), in the following, we investigate the effect of only a lower limit in the measurements on the resulting moments. As an example, we consider a PAS-like instrument that measures single particles, but the result are also valid for other instruments.

An instrument that measures individual particles has an inherent lower limit of a single count. If we take the measurements of the FRD as expectation values for the number of measured particle events, the actual number of expected counts is given by the unscaled density, which is the scaled density shown in Figs. 6a), b) multiplied with nsw, in/vth, in. Thus, for a given vth, in, or NBpS respectively, the total number of expected counts and the expected number of counts in the individual bins scale with nsw, in. The fixed lower limit of a single count can then be realised by setting the expectation values of all bins with an unscaled expectation value smaller than one to zero. We implement this lower limit directly in the scaled density of the FRD, where the lower limit still corresponds to a single count but the effective threshold is given by the scaling factor vth, in/nsw, in. We refer to the resulting model as Finite Resolution Detector with limited sensitivity (FRDLS) with an effective threshold vth, in/nsw, in. We emphasise that different effective thresholds correspond to a single instrumental sensitivity and their spread at a given NBpS reflects the dependence of the expected values on the range of densities that the instrument has to observe.

In Figs. 6a) and b) horizontal solid coloured lines show three effective thresholds of 10−1 (brown), 10−2 (olive), and 10−3 (magenta). The expectation values of each instrumental bin, indicated by blue crosses, below these lines are set to zero. Figs. 6a), b) shows that with increasing effective thresholds, i.e. with an increasing ratio vth, in/nsw, in more bins in the flanks of the distribution are below the effective threshold. As a rough guideline, these effective thresholds illustrate the limitations of a solar wind instrument that observes an input VDF with a total number of ≈10, 100, and 1000 counts respectively. The 0th, 1st, and 2nd moments resulting from the FRDLS for the same three thresholds are shown in panels d), e), and f) of Fig. 6, respectively. These results can be directly compared to the results of the FRD with unlimited sensitivity, which are shown in blue, and the differences show the systematic effects that are introduced by the limited sensitivity.

The sawtooth patterns observed for all three effective thresholds occur if the expectation values in individual bins cross the respective effective threshold. As was expected, for all three moments the deviations from the FRD are stronger with increasing effective thresholds, and thus with worsening sensitivity. While the 0th moment is reproduced by the FRD with unlimited sensitivity perfectly, an increasing effective threshold results for an FRDLS in systematic underestimation of the derived density. For the 1st moment (given in panel e) in units of the thermal speed vth) the effect of an effective threshold is symmetric and is small compared to the thermal speed. Again, the 2nd moment is more strongly affected than the density and velocity. Here, limited instrumental sensitivity leads to a strong underestimation of the temperature. Depending on the effective threshold, the resulting temperature underestimation can even be dominant compared to the overestimation arising from the finite grid spacing. For both the density and temperatures, the results show a trend of increasing underestimation with increasing NBpS. This is also to be expected as the VDF is distributed over an increasing number of bins with increasing NBpS and thus the expectation values of individual bins are more likely to be below the effective threshold. For all three moments an effective threshold of 10−3 already reproduces the properties of the input VDF well.

We focus here on the effect of the lower limit of the instrumental sensitivity. Although not shown here, we expect a qualitatively similar behaviour for the upper limit in the 0th and 1st moments compared to the lower limit. In the 2nd moment, an upper sensitivity limit can also lead to an additional overestimation.

In Sect. 5.1 we suggested an instrument with NBpS ≥ 2.9 to achieve a systematic error of less than 1% for the derived temperatures (based on its finite resolution). For this grid spacing, the effective threshold of 10−3 leads to a systematic error due to the limited sensitivity (see Fig. 6f)) in the same order. However, the dynamic range of the to-be-observed solar wind plasma has to be considered here. If a dynamic range in the temperatures of 100 is to be resolved by an instrument, this translates to a dynamic range of 10 in vth, and thus the NBpS of the above considered instrument increases to NBpS = 29 for a solar wind stream with temperature 100 times higher than before. While this further decreases the systematic error due to the finite resolution, the detrimental effect of the limited sensitivity increases due to the now smaller bin sizes relative to the distribution and the resulting smaller expectation values. In this case, for the effective threshold of 10−3 the systematic error increases to about 15%. Hence, the limited sensitivity of a real instrument affects high temperatures more strongly than lower temperatures under otherwise identical solar wind conditions. The design of future instruments should reflect this finding and the uncertainties should be carefully characterised and quantified based on the detailed design in the early stage of development. Even considering a high dynamic range, the systematic errors from the limited sensitivity should remain in the range of the systematic errors from the finite resolution of the instrument.

For a real instrument, the effective threshold depends on the combination of the solar wind density and temperature. For example, for a fixed temperature, a varying density is reflected by different total numbers of counts that cover a larger or smaller part of the underlying VDF. This effect limits the comparability of temperatures measured by the same instrument for different densities.

5.4. Finite resolution detector summary

With the idealised FRD, we showed that the finite resolution alone is sufficient to introduce an overestimation of the temperature. Only for high resolution (here, NBpS ≥ 2.9) small errors (below 1%) in the temperature measurement can be achieved. However, this also requires a large FoV, as is illustrated for VPAS, which does not reach this regime before the effect of a too small FoV already leads to an underestimation of the temperature. Limited instrumental sensitivity introduces a second source of temperature underestimation that varies with the input density.

In fact, without the limited FoV and limited instrumental sensitivity and the resulting cut-off of the distribution, the overestimation of the temperatures for VPAS would remain above that of the FRD. However, if the resolution of VPAS would have been six times higher with similar shaped response functions and the effective sensitivity threshold is 10−3 or better, the resulting instrument would operate in a regime with an approximately constant but small temperature overestimation. This overestimation would still be position-dependent due to the effects of the non-uniform and overlapping responses. However, for the 15–20% of all PAS observations cases below the instrumental resolution (see regime I Fig. 5f)) we estimate that the resolution would need to have been even > 10 times higher.

The interplay of the three different effects, finite resolution, limited FoV, and limited sensitivity, with their different dependencies and resulting over- and underestimations clearly demands for in-depth analysis of each instrument’s capabilities. All three effects contribute systematic errors that are superposed in the measurements. Although occasionally the overestimation due to the finite resolution and the underestimation due to limited FoV or limited sensitivity can be in the same order, i.e. Tout ≈ Tin, this must not be confused with a mitigation of these systematic effects. The combination of the three systematic errors depends sensitively on the varying solar wind conditions and without full a priori knowledge of the input VDF it is not feasible to identify in a given observation which of these effects contributed exactly to which degree.

A forward-modelling approach, as is suggested in Nicolaou et al. (2025), is useful in this context but requires a model that is flexible enough to describe the measured VDF accurately. For the collisionless solar wind, a simple (bi-)Maxwellian model would be insufficient. We emphasis that these effects can only be mitigated by design and cannot be corrected for afterwards without very strong assumptions about the underlying VDFs.

Our findings hold true for previous missions and their corresponding data analysis as well as for proposed future solar wind instrumentation. In detail, the design of the latter should reflect that the coldest to-be-observed temperatures drive the systematic errors due to the finite resolution while the hottest to-be-observed temperatures (and smallest to-be-observed densities) drive the systematic errors due to the limited sensitivity.

6. PAS versus SPAN-I data

In the previous sections, we have investigated the impact of the instrumental resolution on derived solar wind moments. For the case of PAS we have shown that especially the 2nd moments, i.e. temperatures, are systematically overestimated if the VDFs are inside the FoV. The case of the FRD shows that an overestimation of temperatures is a generally expected feature that arises even under idealised conditions from the finite resolution. The data presented in Fig. 2 shows that SPAN-I temperatures have similar features compared to PAS. However, these data cannot be compared directly, because PAS and SPAN-I measure at different places and times. The radial evolution of the solar wind and the solar activity cycle especially do not allow for a direct comparison of measurements taken at different distances to the Sun or under different solar activity.

6.1. Data selection and influence of frame of reference

To select comparable datasets with respect to solar modulation and radial evolution of the solar wind we applied the following criteria for the comparison in this section. For further details on the data selection see Appendix D. We chose data from both instruments that were taken between 1 January 2022 and 28 July 2023 within 0.3 and 0.5 AU (see Fig. 7a)). These data were further split into vsw intervals of 10 km/s width from 350 km/s to 550 km/s Figs. 7b)–d) shows the distribution of observed solar wind speeds in SRF and RTN and each of these panels highlights one example vsw interval. Similarly to Fig. 5f) the cumulative fractions of observed αx, obs, αy, obs, αz, obs were derived (see Figs. 7f)–k)). Therein, the cumulative fractions for each velocity bin are represented individually, i.e. each line represents a 10 km/s bin. A thicker line marks the velocity bin illustrated in panels b)–e). We refer to the cumulative fractions as distributions in the following.

|

Fig. 7. Comparison of PAS and SPAN-I for 1 January 2022 and 28 July 2023. a) Orbits of PAS and SPAN-I. The selection of radial distances (0.3 AU–0.5 AU) that is applied in the panels below is marked with grey shading. Panels b)–e) frequencies of occurences of solar wind velocities in SRF and RTN. An example of a single velocity bin selected based on |

In this section, we specify the frame of reference for the solar wind velocities since here SRF and RTN play a role. As is illustrated in Fig. 1, α depends on  , which is different from the real solar wind speed, v

, which is different from the real solar wind speed, v . Differences in the data from the two instruments based on a selection for certain

. Differences in the data from the two instruments based on a selection for certain  alone are likely a combination of instrumental effects and physical differences; for example, the effects of mixing different solar wind regimes. However, comparing data for certain

alone are likely a combination of instrumental effects and physical differences; for example, the effects of mixing different solar wind regimes. However, comparing data for certain  mixes data observed by instruments on different spacecrafts with variable

mixes data observed by instruments on different spacecrafts with variable  and thus the same temperatures will appear at different values of α in the instrument. Here, we aim to disentangle effects arsing from physical and instrumental differences in the observations of PAS and SPAN-I. Thus, the selection based on vsw has been made twice: On the left side of Fig. 7 in panels b), d), f), h), j) the results for the selection based on

and thus the same temperatures will appear at different values of α in the instrument. Here, we aim to disentangle effects arsing from physical and instrumental differences in the observations of PAS and SPAN-I. Thus, the selection based on vsw has been made twice: On the left side of Fig. 7 in panels b), d), f), h), j) the results for the selection based on  and on the right side in panels c), e), g), i), k) the results for the selection based on

and on the right side in panels c), e), g), i), k) the results for the selection based on  are shown. The mixing of the velocities in these two FoRs due to the respective spacecraft eigenvelocities can be seen for one example vsw-bin in panels b)–e). In panels b) and d), the velocity bin in SRF

are shown. The mixing of the velocities in these two FoRs due to the respective spacecraft eigenvelocities can be seen for one example vsw-bin in panels b)–e). In panels b) and d), the velocity bin in SRF  (dashed lines) is populated by two distinct populations of solar wind speeds in RTN for both instruments (solid lines). This behaviour is expected due to the spacecrafts’ eigenvelocities. The respective spacecraft eigenvelocities change over the orbit (see panel a)) and are for PAS and SPAN-I at the selected positions larger than the chosen bin width of 10 km/s. Since data from all orbits can be selected, for each selection (based on