| Issue |

A&A

Volume 705, January 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A56 | |

| Number of page(s) | 24 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202555539 | |

| Published online | 06 January 2026 | |

The multi-messenger view of pulsar timing array black holes with the Horizon-AGN simulation

1

Université Paris Cité, CNRS, Astroparticule et Cosmologie, F-75013 Paris, France

2

Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, UMR 7095, CNRS and Sorbonne Université, 98 bis boulevard Arago, 75014 Paris, France

3

IRAP, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, UPS, CNES, 9 Avenue du Colonel Roche, BP 44346, 31028 Toulouse Cedex 4, France

4

Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory, Edinburgh EH9 3HJ, UK

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

16

May

2025

Accepted:

3

November

2025

We used the HORIZON-AGN cosmological simulation to study the properties of supermassive black hole binaries (MBHBs) with the largest contribution to the gravitational wave background (GWB) signal expected for the pulsar timing array (PTA) band. We developed a pipeline to generate realistic populations of MBHBs, which enabled us to estimate both the characteristic strain and GWB time series observable by PTA experiments. We identified potential continuous wave (CW) candidates standing above the background noise, using toy PTA sensitivities representing the current EPTA and future SKA. We estimated the probability of detecting at least one CW with a signal-to-noise ratio of S/N > 3 to be 4% (20%) for EPTA (SKA)-like sensitivities, assuming a ten-year baseline. We found that the GWB is dominated by hundreds to thousands of binaries at redshifts in the range 0.05 − 1, with chirp masses of 108.5 − 109.5 M⊙, primarily hosted in quiescent massive galaxies residing in halos of mass ∼1013 M⊙. CW candidates have larger masses and lower redshifts, and they tend to be found in even more massive halos, typical of galaxy groups and clusters. The majority of these systems would appear as active galactic nuclei (AGNs), rather than quasars, because of their low Eddington ratios. Nevertheless, CW candidates with fEdd > 10−3 can still outshine their hosts, particularly in radio and X-ray bands, suggesting that they could serve as the most promising route for identification. Our findings imply that optical and near-infrared (NIR) searches based on light curve variability are challenging and biased toward more luminous systems. Finally, we highlight important caveats in the common method used to compare PTA observations with theoretical models. We find that GWB spectral inferences used by PTAs could be biased toward shallower slopes and higher amplitudes at f = 1/yr, thereby reducing the apparent tension between astrophysical expectations and PTA observations.

Key words: gravitational waves / methods: numerical / quasars: supermassive black holes

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

The origin and evolution of supermassive black holes (MBHs, 106–1010 M⊙) remain unclear. A number of MBHs have been detected very early in the evolution of the Universe, up to z ∼ 10 − 11 (Maiolino et al. 2024; Bogdán et al. 2024), while the peak of MBH activity occurs at z ∼ 2 − 3 (Merloni et al. 2004) and many local galaxies host quiescent MBHs (Richstone et al. 1998). Their evolution must have started at early cosmic times, plausibly from intermediate mass black holes (102–105 M⊙), growing through long or repeated periods of sub- (and perhaps even super-) Eddington accretion and/or via multiple mergers, such as Volonteri et al. (2021). Whilst mHz gravitational wave (GW) detections with LISA (Amaro-Seoane et al. 2017) will probe the existence and mergers of massive black holes out to z ∼ 20, the importance of MBH mergers in the Local Universe is currently being probed by the pulsar timing array (PTA) experiments (Foster & Backer 1990), which are able to detect GW signals in the 1–100 nHz frequency range.

Recently, various PTA experiments have presented the first observational evidence for a GW signal (NANOGrav, Agazie et al. 2023a; EPTA & InPTA, EPTA Collaboration 2023a; PPTA, Reardon et al. 2023; CPTA, Xu et al. 2023; and MeerKAT, Miles et al. 2024). This signal shows both spatial and temporal correlations among pulsars, consistent with those expected from a stochastic GW background (Hellings & Downs 1983). The low signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of the detection makes the interpretation difficult, but one possibility is the incoherent superposition of GWs from a population of massive black hole binaries (MBHBs) with separations on the milliparsec scale. Indeed, inference of the GW background spectrum using PTA data confirms that the observed signal is broadly consistent with expectations from the MBHB population (Agazie et al. 2023b; EPTA Collaboration 2024a), although the data tend to favor a larger amplitude than what has been theoretically predicted. One possibility is that the signal emanates from individually resolvable MBHBs that are particularly close and heavy, therefore standing above the background signal (e.g., Mingarelli et al. 2017; Agazie et al. 2023c). However, so far, this scenario is not supported by current PTA datasets (EPTA Collaboration 2024b; Agazie et al. 2023c). Meanwhile, unmodeled noise or overly agnostic priors for the noise parameters could also explain part of the tension (Zic et al. 2022; Goncharov 2025; van Haasteren 2025). In this work, we show that an overly direct comparison between the theoretical power spectrum predicted by cosmological simulations (Kelley et al. 2017a; Sykes et al. 2022; Chen et al. 2025) or semi-analytical models (Wyithe & Loeb 2003; McWilliams et al. 2014; Bonetti et al. 2018) and the data-inferred power spectra could lead to misleading conclusions about potential tensions between the two. In particular, the impact of the finite duration of the datasets on spectral inference should be considered more carefully1.

In the absence of a stronger GW detection, complementary data are necessary to understand the origin of the signal. Cosmological simulations can be used to understand the prevalence and nature of MBHBs in the Universe. These would also help in identifying which of these would be detectable with the PTAs and contribute to the GW background and/or be detectable as individual objects. Electromagnetic observations of these objects would help confirm the nature of the GW sources, but simulations can help us better understand where to search and provide the best strategy for the wavelength ranges to target (see e.g. Cella et al. 2025). With such prior knowledge, the overall challenging multi-messenger detection of MBHBs using PTAs (Charisi et al. 2022; Petrov et al. 2024) could be facilitated (Liu & Vigeland 2021; Truant et al. 2025).

In this paper, we use the Horizon-AGN cosmological simulation to identify and study the MBHBs that contribute most to the GW signal in the PTA band, either by contributing to the background signal or as resolvable continuous wave sources. We study the properties of these MBHBs along with those of their host galaxies. We determine the expected electromagnetic emission from radio to X-ray wavelengths, which we validate by comparing with the properties of MBHB candidates. We also identify the types of searches that would have the best chance of detecting the electromagnetic counterparts of the PTA sources. Finally, we investigate the commonly used methodology for comparing PTA observations with the predicted characteristic strain signal, highlighting its potential limitations when used to interpret the origin of the observed signal.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the HORIZON-AGN simulation used in our study. In Sect. 3, we describe how we built our catalog of merging MBHBs from the simulation and modeled their sub-parsec dynamics in post-processing. In Sect. 4, we present how we generated realizations of the inspiralling MBHB population and inferred the associated characteristic strain signal. We also present the properties of the most contributing binaries and estimate their number in the PTA band. In Sect. 5, we compare the standard methodology used to convert the GW strain signal into timing residuals measured by PTAs, with a more accurate method, and highlight the potential limitations of the former. Using two toy PTA sensitivities, we also identified potentially resolvable individual binaries, for which we analyzed their properties and those of their host galaxies in Sect. 6, along with their electromagnetic properties, and evaluate their potential detectability in Sect. 7. We summarize our findings in Sect. 8.

2. The Horizon-AGN simulation

HORIZON-AGN (Dubois et al. 2014a) is a hydrodynamical cosmological simulation with a large volume (142 comoving Mpc)3, assuming a standard Λ cold dark matter (ΛCDM) cosmology with total matter density of Ωm = 0.272, dark energy density of ΩΛ = 0.728, baryon density of Ωb = 0.045, Hubble constant of H0 = 70.4 km s−1 Mpc−1, and an amplitude of the matter power spectrum and power-law index of the primordial power spectrum of σ8 = 0.81 and ns = 0.967, respectively. In this simulation, refinement is permitted down to  , the stellar particle mass is 2 × 106 M⊙, the dark matter particle mass is 8 × 107 M⊙, and the MBH seed mass is 105 M⊙.

, the stellar particle mass is 2 × 106 M⊙, the dark matter particle mass is 8 × 107 M⊙, and the MBH seed mass is 105 M⊙.

The gas in HORIZON-AGN has an equation of state for an ideal monoatomic gas with an adiabatic index of γad = 5/3. Gas cooling can be modeled down to a floor temperature of 104 K using the curves from Sutherland & Dopita (1993). Heating of the gas from a uniform UV background starts after redshift zreion = 10, following the prescription in Haardt & Madau (1996). In regions that exceed a gas hydrogen number density threshold of  , star formation is triggered in a Poisson random process (Rasera & Teyssier 2006; Dubois & Teyssier 2008), following the Schmidt relation with a constant star formation efficiency of ε* = 0.02 (Kennicutt 1998; Krumholz & Tan 2007). A mechanical energy injection from Type Ia supernovae (Type Ia SNe), Type II SNe, and stellar winds is included assuming a Salpeter (1955) initial mass function (IMF) with cutoffs at 0.1 M⊙ and 100 M⊙.

, star formation is triggered in a Poisson random process (Rasera & Teyssier 2006; Dubois & Teyssier 2008), following the Schmidt relation with a constant star formation efficiency of ε* = 0.02 (Kennicutt 1998; Krumholz & Tan 2007). A mechanical energy injection from Type Ia supernovae (Type Ia SNe), Type II SNe, and stellar winds is included assuming a Salpeter (1955) initial mass function (IMF) with cutoffs at 0.1 M⊙ and 100 M⊙.

Massive black holes and their feedback follow the numerical implementation of Dubois et al. (2012). They are seeded in cells where the gas density is larger than n0 and where the gas velocity dispersion is larger than 100 km s−1. The MBH seeding is stopped at z = 1.5. To avoid formation of multiple MBHs in the same galaxy, an exclusion radius of 50 comoving kpc is imposed in the seeding process. To compensate for the inability to capture the multiphase nature of the interstellar gas, the MBH accretion rate is set to be the Bondi-Hoyle-Littleton rate multiplied by a factor αb = (n/n0)2 when n > n0 and αb = 1 otherwise (Booth & Schaye 2009). The effective accretion rate onto MBHs is capped at the Eddington luminosity with a radiative efficiency of 0.1. 15% of the MBH emitted energy is isotropically coupled to the gas within 4Δx as thermal energy for luminosities above 1% of the Eddington luminosity. If the 1% of the Eddington luminosity threshold is not reached, then the feedback takes a mechanical form instead, with 100% of the power injected into a bipolar cylindrical jet with a radius of Δx and a height of 2Δx, at a velocity of 104 km s−1.

Instead of constantly repositioning MBHs at the minimum of the local potential, which causes unnatural dynamics (Tremmel et al. 2015), gas dynamical friction is exerted on the MBH to avoid spurious motions due to finite force resolution effects (see Dubois et al. 2013 for additional details). The boost factor used here is the same as the boost factor αb for accretion. The equation of gas dynamical friction is  , where G is the gravitational constant, ρgas is the mass-weighted mean gas density within a sphere with a radius of 4 Δx, and fgas is a factor function of the Mach number,

, where G is the gravitational constant, ρgas is the mass-weighted mean gas density within a sphere with a radius of 4 Δx, and fgas is a factor function of the Mach number,  , which accounts for the extension and shape of the wake (Ostriker 1999). Finally, fgas is in a range between 0 and 2 for an assumed Coulomb logarithm of 3 (Chapon et al. 2013; Lescaudron et al. 2023).

, which accounts for the extension and shape of the wake (Ostriker 1999). Finally, fgas is in a range between 0 and 2 for an assumed Coulomb logarithm of 3 (Chapon et al. 2013; Lescaudron et al. 2023).

In HORIZON-AGN the dark matter halos and galaxies are identified with the AdaptaHOP halo finder (Aubert et al. 2004). The density field used in AdaptaHOP is smoothed over 20 particles. The identification density threshold is set to be 178 times the average total matter density. On top of the density criteria, either 50 dark matter particles or 50 star particles are required for a dark matter halo or galaxy identification. The centers of halos and galaxies are estimated using the shrinking sphere approach proposed by Power et al. (2003).

3. Selection and modeling of MBH binaries in Horizon-AGN

We generated a catalog of MBH mergers using the post-processed simulation data. To find merging MBHs, we searched through the data of all MBHs at each coarse time step (∼0.6 − 0.7 Myr) of the HORIZON-AGN simulation. We note that this time step is much shorter than the time step over which a full output is saved, which is ∼150 Myr. Each MBH was assigned a unique ID number when seeded. This ID is carried by the MBH through the simulation until it numerically merges with another MBH at a separation of 4Δx. The merged MBH inherits the ID of the primary black hole in the merger, while the secondary MBH ID is erased after the merger. By searching for disappearing MBH IDs, we can find the corresponding MBH mergers. Possible spurious numerical mergers are filtered out by selecting only MBH pairs within max(2Reff, 4Δx) from the galaxy centers, where Reff is the effective radius of the galaxy measured as its projected two-dimensional (2D) radius containing half of the galaxy stellar mass. This check was performed for the primary MBH at the outputs before the merger and for the merged MBH at the output after the merger. The reason is that the MBHs are likely to move relative to the galaxy center in the 150 Myr between outputs.

Although numerical mergers occur when the separation of two MBHs is about 4 kpc in HORIZON-AGN, physical mergers actually take place later on when the separation is of the order of the black hole’s gravitational radius. We define ‘delayed mergers’ as the outcome of adding delays on top of the numerical mergers calculated in post-processing. We followed the methodology described in Volonteri et al. (2020), which we briefly summarize here.

First, we added a dynamical friction phase from the position of the MBHs when they are numerically merged down to the point when they become gravitationally bound. The dynamical friction timescale is estimated assuming the MBH is in an isothermal sphere, considering only the stellar component of the galaxy and including a factor of 0.3 to account for typical orbits being noncircular,

where MBH is the black hole mass, σ★ is the central stellar velocity dispersion approximated as (0.25GM★/Reff)1/2, Λ = ln(1 + M★/MBH), with M★ being the total stellar mass of the galaxy hosting the MBH at the output before the numerical merger and d its distance from the galactic center. As confirmed by Li et al. (2020a), Li et al. (2020b), and Chen et al. (2022), the stellar dynamical friction dominates over the dynamical friction from gas or that from dark matter. We calculated the dynamical friction delay time of both MBHs in a pair and used the longer, which is normally associated with M2.

We also accounted for the shrinking of the binary orbit until coalescence via stellar hardening, viscous torques in a circumbinary disc, and emission of gravitational waves, following Sesana & Khan (2015) and Dotti et al. (2015). The binary evolution timescale to coalescence was taken to be the minimum between the two following equations:

and

Here, q = M2/M1 is the mass ratio of the MBHB. In Eq. (2), σinf and ρinf are the velocity dispersion and stellar density at the sphere of influence, defined as the sphere containing twice the binary mass in stars:

where M12 is the total mass of the binary and

where we continue to assume a singular isothermal sphere power-law density profile with slope −2, and agw is the separation at which the binary spends most of the time (see Sesana & Khan 2015):

The spatial resolution of the Horizon-AGN simulation does not provide reliable information on the density profile at such small orbital separations. However, it was demonstrated in (Volonteri et al. 2020) that the choice of a single isothermal sphere is in very good agreement with the densities measured in observations of local galaxies. In Eq. (3), ε0.1 is the radiative efficiency normalized to 0.1. We followed Dotti et al. (2015) in selecting ai = GM12/2σ★2 and ac = 1.9 × 10−3(M12/108 M⊙)3/4 pc.

To model the eccentricity evolution in post-processing, we first assigned an eccentricity to each binary when reaching the influence radius, rinf, according to the eccentricity distribution shown in the right panel of Fig. 6 in Li et al. (2020a). The eccentricity is then evolved under loss-cone scattering, viscous drag from the circumbinary disk, and GW emission, from the influence radius to the final coalescence. The orbit hardening and eccentricity evolution due to the loss-cone scattering is described by

and

where forb is the orbital frequency, and H and K are numerical factors resulting from the three-body scattering experiments (Quinlan 1996; Sesana et al. 2006).

The viscous drag due to the circumbinary disk is included when the separation between the binary is below 1 pc. Haiman et al. (2009) described how the binary orbit embedded in a circumbinary (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973) α-disk evolves due to viscous drag and how this evolution depends on the different physical conditions within the disk.

According to Haiman et al. (2009), there are different regimes for an MBHB in a gap-opened, α-disk depending on: (1) whether the radiation pressure or gas pressure balance the vertical gravity (rgas/rad); (2) whether the opacity is dominated by electron scattering or free-free absorption (res/ff); (3) whether the binary is massive enough compared to the local disk mass (M2-dominated or disk-dominated). The characteristic radii are defined as

and

where M7 is the binary mass in units of 107 M⊙ and Rsch = 2GM12/c2 is the Schwarzschild radius corresponding to the binary mass (we denote the speed of light as c in the following).

According to Shapiro & Teukolsky (1983), a disk can be divided into three regions: (i) inner region (r < rgas/rad) with radiation-dominated pressure and electron scattering-dominated opacity; (ii) middle region (res/ff > r > rgas/rad) with gas-dominated pressure and electron scattering-dominated opacity; and (iii) outer region (r > res/ff) with gas-dominated pressure and free-free scattering-dominated opacity. Within each of those three region, there are two possibilities: 1) an M2-dominated region (r < rν/s) and 2) a disk-dominated region (r > rν/s). The rν/s in three regions of an α-disk are defined in Haiman et al. (2009) as

Thus, there are six regimes and their orbital frequency evolution rates are listed below.

(1) Disk-dominated, inner region:

if  ;

;

(2) M2-dominated, inner region:

if r < rgas/rad and  ;

;

(3) Disk-dominated, middle region:

if rgas/rad < r < res/ff and  ; where r3 is the orbital semi-major axis in units of 103Rsch, qs = 4q/(1 + q)2 is the symmetric mass ratio. We note that this prescription implies that the MBHB orbit always shrinks under the influence of viscous drag, especially in the presence of stellar hardening suggested by some most recent simulations (Cuadra et al. 2009; Roedig et al. 2012; Bortolas et al. 2021; Franchini et al. 2021; Amaro-Seoane et al. 2023)

; where r3 is the orbital semi-major axis in units of 103Rsch, qs = 4q/(1 + q)2 is the symmetric mass ratio. We note that this prescription implies that the MBHB orbit always shrinks under the influence of viscous drag, especially in the presence of stellar hardening suggested by some most recent simulations (Cuadra et al. 2009; Roedig et al. 2012; Bortolas et al. 2021; Franchini et al. 2021; Amaro-Seoane et al. 2023)

(4) M2-dominated, middle region:

if rgas/rad < r < res/ff and  ;

;

(5) Disk-dominated, outer region:

if r > res/ff and  ;

;

(6) M2-dominated, outer region:

if r > res/ff and  .

.

The eccentricity evolution due to viscous drag can be complex and cannot be trivially reduced to a prescription for a single dominant regime. The simulation results in Roedig et al. (2011) show that if the incoming eccentricity of the MBHB on a prograde orbit is > 0.04 then there is a saturation eccentricity in the range (0.6, 0.8). Following this result, we randomly assign an eccentricity between 0.6 and 0.8 after one viscous timescale (measured at the separation where viscous drag begins to dominate the evolution). If the eccentricity of the orbit is less than 0.04 when viscous drag takes over the orbital decay, the eccentricity remains fixed until GW emission takes over the orbital evolution.

By numerically solving these equations, we can determine the dynamics (given an initial eccentricity at rinf) of each delayed merger in HORIZON-AGN, tracking both the orbital frequency and eccentricity of the binaries. In the following section, we discuss how to use this information to compute a realistic GW background signal from the population of MBHBs.

4. Estimating the gravitational wave background with Horizon-AGN

In this section, we present the methodology for estimating the GW strain spectrum from the population of MBHBs extracted from the simulation HORIZON-AGN. We computed it by assuming both circular and eccentric ensembles of MBHBs and investigated the properties of the resulting backgrounds.

4.1. Methodology

4.1.1. The analytic average

The gravitational wave background (GWB) can be described at each observed frequency, f, by the characteristic strain, hc(f), which can be evaluated by integrating the comoving density of coalescing binaries (Phinney 2001), expressed as

where z is the merger redshift, n is the number of MBHB mergers per comoving volume and where we grouped the binary parameters (M1, q, σstar,...) in the ξ vector. The characteristic strain is related to the energy released in GWs over the entire binary history (dEGW) per logarithmic frequency interval in the source rest frame, where fs = (1 + z)f.

An MBHB on an (almost) circular orbit emits GWs at twice its orbital frequency, as higher order modes can be safely ignored since they are suppressed by a factor of vorb/c ≪ 1, where vorb is the orbital velocity. In the single dominant mode case, we have a one-to-one relationship between the GW frequency in the source frame fs and the binary orbital frequency forb: dEGW/dlnfs = dEGW/dlnforb. However, this is no longer true for binaries in eccentric orbits. In this case, the emitted GW power is distributed across a set of orbital frequency harmonics, m, and the distribution depends on the orbital eccentricity of the binary. Loss of orbital momentum through gravitational radiation leads to orbital circularization. As a result, the total GW energy dEGW emitted within an observer frequency band centered on fs will include contributions from different harmonics m reflecting different stages of the binary evolution, where forb = fs/m. In most general (eccentric orbits) case the energy release can be written as (Enoki & Nagashima 2007), expressed as

Here, we introduce the time to coalescence, τc, measured in the binary rest frame, and the GW luminosity2 of a binary in a circular orbit corresponding to the mean eccentric motion:

where ℳc = (M1M2)3/5/(M12)1/5 is the binary chirp mass. The GW spectrum is then obtained by including the g(m, e) function, which gives the relative average (over one orbit) GW power emitted at a given harmonic m by a binary with orbital eccentricity e (see Eq. (A1) in Peters & Mathews 1963 for an explicit expression of g(m, e) in terms of Bessel functions).

The energy emitted per logarithmic frequency band is given as a product of GW luminosity and the time the binary spent in that band, expressed as  . As mentioned, we use the energy release averaged over the orbit; however, for eccentric motion, it varies significantly over the orbit, where most of the GW power is emitted during the periapse passage. The uneven energy release over time in highly eccentric binaries with long orbital periods could induce nonstationarity in the GWB signal (Falxa et al. 2025). In this work we neglect this effect and consider the averaged (over period) GWB spectrum.

. As mentioned, we use the energy release averaged over the orbit; however, for eccentric motion, it varies significantly over the orbit, where most of the GW power is emitted during the periapse passage. The uneven energy release over time in highly eccentric binaries with long orbital periods could induce nonstationarity in the GWB signal (Falxa et al. 2025). In this work we neglect this effect and consider the averaged (over period) GWB spectrum.

For circular orbits, as described in Sect. 4.1.3 below, we use the e → 0 limit of Eq. (21) directly. For eccentric binaries, we approximate this expression by computing the MBHB dynamics over a finite-width orbital log-frequency grid using the method presented in Sect. 4.1.4, namely,

We introduce

which is the set of orbital frequency harmonics, m, that would lead to an observed GW frequency within the log-frequency band [lnf − Δlnf/2, lnf + Δlnf/2] for a binary at a redshift, z.

Next, we use the estimation for the merger comoving density given by the HORIZON-AGN merger catalog,

where Vsim is the comoving volume of the simulation, to obtain the analytic expression for the average GWB spectrum:

The sum is over the total energy emitted in GWs by the simulation mergers labeled by j,  , which can be computed either directly using Eq. (21), if an analytic expression for dτc/dlnforb is available, or approximately by Eq. (23). Let us emphasize that this expression is fully deterministic, since we compute only one dynamical evolution for each delayed merger in HORIZON-AGN.

, which can be computed either directly using Eq. (21), if an analytic expression for dτc/dlnforb is available, or approximately by Eq. (23). Let us emphasize that this expression is fully deterministic, since we compute only one dynamical evolution for each delayed merger in HORIZON-AGN.

4.1.2. Building realizations of the Universe

The analytic computation of the characteristic strain spectrum presented in the previous section is, by definition, deterministic and does not introduce any cosmic variance inherent to the discreteness of the binary population (see Sesana et al. 2008). To estimate the variation in the strain signal due to different realizations3 of the Universe, one must consider the population of inspiralling MBHBs instead of mergers, which are the actual GW sources in the PTA band. In this case, the GWB characteristic strain can be computed as the integral over the redshift of the distribution of inspiralling MBHBs,

where  is the number of inspiralling sources and

is the number of inspiralling sources and  is the characteristic strain of one source with given properties. The distribution of inspiralling MBHBs can be derived from the comoving density of mergers using

is the characteristic strain of one source with given properties. The distribution of inspiralling MBHBs can be derived from the comoving density of mergers using

where Vc is the comoving volume (see Appendix A and also Sesana et al. 2008 and Babak et al. 2023 for details). As a result, for each merger j of the simulation, a PTA should observe, on average,  inspiralling binaries with an orbital frequency in

inspiralling binaries with an orbital frequency in ![$ \left[{f_{\mathrm{orb}}}^{(k)} e^{ - \Delta \ln{f_{\mathrm{orb}}} /2}, {f_{\mathrm{orb}}}^{(k)} e^{ \Delta \ln{f_{\mathrm{orb}}} /2}\right] $](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa55539-25/aa55539-25-eq44.gif) ,

,

For the ΛCDM cosmology used in the HORIZON-AGN simulation, the expression in the square brackets equals 4πdM2c(1 + zj), where dM is the comoving distance to the source at redshift zj (Hogg 1999) and  is the residence time of the binary j in the k-th log-orbital frequency bin. To construct a Universe realization, we follow the approach of Kelley et al. (2017b) and draw a number of inspiralling binaries from a Poisson distribution with mean

is the residence time of the binary j in the k-th log-orbital frequency bin. To construct a Universe realization, we follow the approach of Kelley et al. (2017b) and draw a number of inspiralling binaries from a Poisson distribution with mean  , for each HORIZON-AGN merger j and each orbital frequency bin k. To obtain the total induced characteristic strain for a finite-width observer’s log-frequency band centered on f, we sum the contributions from each inspiralling MBHB using Eq. (27), Eq. (25) and

, for each HORIZON-AGN merger j and each orbital frequency bin k. To obtain the total induced characteristic strain for a finite-width observer’s log-frequency band centered on f, we sum the contributions from each inspiralling MBHB using Eq. (27), Eq. (25) and

where dL(z) = (1 + z)dM is the luminosity distance to the source. The dependence on ξ on the right-hand side is hidden in the GW luminosity function of the binary and its orbital eccentricity evolution function. This expression is only valid if the orbital frequency evolution of the binary is slow enough to consider that all of the GW emission over the observation period is within the considered observer frequency band centered on f. This condition is met for the current duration of the PTA observations. Indeed, for the HORIZON-AGN MBHBs, we checked that the frequency evolution is negligible for a PTA with 15 years of observing duration and for an observer frequency below fyr ≡ 1/year ≃ 32 nHz.

4.1.3. The circular ensemble modeling

In this section, we describe our derivation of the GWB spectrum for the ensemble of circular MBHBs with the orbital dynamics driven by GW emission and loss-cone scattering. With this simplification, we can carry out all the derivations analytically and use them as a reference for comparison with a more realistic model that allows for eccentric MBHBs.

For circular orbits (e = 0), the GW power is emitted at the harmonic m = 2, for which g(2, 0) = 1 and fs = 2forb = (1 + z)f. This significantly simplifies Eq. (21), as the sum over m is now reduced to a single term (m = 2). The remaining term is inherently dependent on the binary orbital dynamics, which can be characterized by the evolution of the semi-major axis a:

In addition to the GW emission, we incorporate the orbit hardening due to loss-cone scattering (see Eq. (7)). In the binary rest frame, the dynamics can be modeled as

Here, we neglected the impact of loss-cone scattering on the binary eccentricity evolution, as we forced the binaries to remain circular4. We can compute the second term of Eq. (31) by assuming that the binaries follow Keplerian orbits.

As a result, Eq. (31) can be integrated on a given finite-width orbital frequency grid and plugged in Eq. (29) to build Universe realizations. In the following, we used log-orbital frequency grids corresponding, for each merger, to 125 log-observer frequency bins equally spaced between fmin = 0.8 nHz and fmax = 60 nHz. The upper bound is constrained by neglecting the frequency evolution (over PTA observing duration) of binaries in our study.

4.1.4. The eccentric ensemble modeling

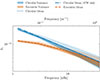

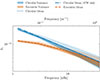

As mentioned in Sect. 3, a more detailed description of the MBHB dynamics requires the inclusion of additional physics (viscous drag, eccentricity evolution, etc.) which makes it technically unfeasible to obtain a derivation of the analytical expressions for the orbital parameters (forb, e, ...) as a function of time. To overcome this limitation (as detailed in Sect. 3), we numerically integrated the dynamics of each merger, j, and stored their orbital parameters on a logarithmic (observer) orbital frequency grid  , for k ∈ [0, 40]. One must go to such a low orbital frequency to have a precise estimate of the GW signal in the PTA band because the GWs emitted by eccentric binaries could have a significant power at frequencies as high as 100 forb for e ≳ 0.9 (Peters & Mathews 1963). We can extract the residence time in each orbital frequency bin k from the numerical integration and evaluate Eq. (29) for each merger, j. An example for three HORIZON-AGN binaries is shown in Fig. 1. The eccentricity evolution function

, for k ∈ [0, 40]. One must go to such a low orbital frequency to have a precise estimate of the GW signal in the PTA band because the GWs emitted by eccentric binaries could have a significant power at frequencies as high as 100 forb for e ≳ 0.9 (Peters & Mathews 1963). We can extract the residence time in each orbital frequency bin k from the numerical integration and evaluate Eq. (29) for each merger, j. An example for three HORIZON-AGN binaries is shown in Fig. 1. The eccentricity evolution function  for each merger can then be used to compute both Eq. (23) and Eq. (30) to obtain the analytic average GW spectrum using Eq. (26) and the Universe realization spectrum using Eq. (27).

for each merger can then be used to compute both Eq. (23) and Eq. (30) to obtain the analytic average GW spectrum using Eq. (26) and the Universe realization spectrum using Eq. (27).

|

Fig. 1. Examples of the residence time (bottom panel), Δτc, per log10 orbital frequency bin are shown for three binaries from the HORIZON-AGN catalog, with chirp masses of 107, 108, and 109 M⊙. We also show their respective eccentricity evolution in the top panel. Eccentric systems are more efficient in dissipating the energy through GWs and this can be seen in the residence time (low panel) as compared to (nearly) circular binaries. The evolution of binaries at high frequencies (starting from a few nHz) is determined by the gravitational radiation, which is more efficient in energy dissipation for heavy and eccentric binaries. We also observe a fast circularization of eccentric systems in the top panel. |

4.2. Characterizing GW signal from a population of MBHBs

4.2.1. Properties of the GW background

The characteristic strain spectra for the circular and eccentric ensembles are shown in Fig. 2. As expected, assuming circular binaries driven by GW emission, we find a mean characteristic strain spectrum that follows the power-law behavior of Eq. (41), with an amplitude at fyr of Ayr = 3.4 × 10−15 and a spectral index of α = −2/3 as derived in Phinney (2001). The background amplitude for HORIZON-AGN is higher than for many other theoretical models. This can be seen in Appendix A of Agazie et al. (2023b) for pre-2023 models, as well as in new models developed by the EPTA collaboration to explain the detected amplitude (EPTA Collaboration 2024a). In fact, Izquierdo-Villalba et al. (2022) already noted that models that reproduce the background amplitude exceed electromagnetic constraints, such as the bright end of the low-redshift AGN luminosity function. In fact, HORIZON-AGN overpredicts the AGN luminosity function (Volonteri et al. 2016), explaining why the background amplitude of the simulation is closer to the value measured by PTAs compared to other models. We stress that in this paper we are not trying to “fit” the amplitude of the background, but we are trying to understand what factors influence the background, and explore the properties of the sources within a unified framework.

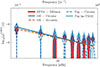

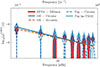

|

Fig. 2. 68% (dark) and 90% (light) confidence regions for the characteristic strain hc are shown for 2000 Universe realizations drawn from the HORIZON-AGN MBHB population, assuming either circular orbits (blue) or noncircular orbits (orange). We also plot their respective deterministic mean expectation values in dotted and dashed lines. For the circular population, we overlay as a dashed-dotted line the average spectrum, assuming the binary dynamics are driven by GW emission only. The inclusion of eccentricity introduces a significant signal reduction at frequencies lower than 10 nHz, due to the reduction of the MBHBs residence time at low orbital frequency. |

Since we included interactions with unbound stars when modeling the binary dynamics for the circular population, we did observe a slight bending of the GW spectrum at low frequencies due to the reduction of the residence time at those frequencies (Ravi et al. 2014). Overall, the bend in the HORIZON-AGN population starts to significantly affect the spectrum at observer frequencies lower than 2 nHz, which corresponds to an observation duration of around 15.8 years, in good agreement with previous studies (Sesana 2013; Kelley et al. 2017b). The current PTA experiments might already be sensitive to this effect (Chen et al. 2024).

As already demonstrated in Sesana et al. (2008) and recently investigated on the basis of PTA data in Agazie et al. (2025), the realistic Universe realization spectra from the circular population could significantly deviate from the power-law behavior with the mean spectral index corresponding to α = −2/3. This is related to the stochasticity of the GW signal from the MBHB population: it is stochastic in the limit of a large number of sources emitting in the same frequency bin during the observation period. The number of binaries per frequency bin decreases with an increase in the frequency due to the reduction in their residence time (see Fig. 1 and Eq. (29)), leading to a complete loss of stochasticity above 100–200 nHz. In the intermediate frequency range of 10–50 nHz, the decrease in the number of contributing sources increases both the variance and skewness5 of the total characteristic strain distribution across Universe realizations. This is a well-known effect, already discussed in Jaffe & Backer (2003), Sesana et al. (2008), and later elaborated in Lamb & Taylor (2024). In Fig. 2, the skewness of the strain distribution above 10 nHz is evident for the circular population, where approximately 84% of the GWB spectra have amplitudes below the square root of the average squared strain value. This renders the strain distribution at these frequencies strongly non-Gaussian. As shown in the following, this ultimately results in GWB power spectra with steeper power-law slopes compared to the average spectrum.

When eccentricity is included, we observe two main effects on the GWB spectra. First, we observe the expected bending of the GW spectrum for observer frequencies ≲ 10 nHz, significantly decreasing the background amplitude at a few nanohertz (nHz). This occurs because eccentricity spreads the GW power across multiple orbital frequency harmonics, combined with the fact that the MBHBs gradually circularize due to the emission of GW (Enoki & Nagashima 2007). The second effect of eccentricity is a slight reduction in the variance and skewness of the GW strain amplitude around fyr compared to the circular population. This is caused by the input of highly eccentric binaries with a low orbital frequency, which effectively increases the number of contributions and maintains the stochasticity at higher frequencies.

4.2.2. Properties of the contributing MBHBs

We now investigate the properties of the MBHBs that contribute the most to the GWB across the PTA frequency band. In particular, we compute the contribution of binaries to the total characteristic strain as a function of their redshift and chirp mass. We consider a PTA experiment with observation span Tobs = TEPTA ≃ 10.33 years. As mentioned above, the properties of the total characteristic GW strain vary significantly between the low and high frequency end of the PTA sensitivity band, so we take two representative frequencies: 1/TEPTA ≃ 3.1 nHz and 9/TEPTA ≃ 27.6 nHz. In Fig. 3, we show the differential contribution of the MBHB population divided into redshift slices. The solid line represents the median values across Universe realizations for each redshift slice, while the shaded region indicates the 68% confidence interval, defined here by the 16th and 84th percentiles of the distributions. At low frequencies, for circular and eccentric populations, the peak of the distribution is found around z ≃ 0.3 − 0.4. At lower redshifts, we observe a larger variance in the contribution compared to higher redshifts. Since the variance (width of the confidence interval) is primarily determined by the average number of sources contributing to the GW strain in each bin, this reflects the smaller number of MBHBs expected at low redshift. At high frequency, the peak of distribution for both populations shifts toward a higher redshift, around z ≃ 0.6 − 0.7. The heavy nearby systems, which dominate the GW signal at low frequencies, spend very little time at high frequencies; therefore, the signal accumulates over a larger volume. This also explains the very large variance compared to the low-frequency distribution: we have a lower number of binaries that contribute at high frequencies. Again, at high frequencies, the eccentric population exhibits smaller variance due to the increased number of contributing binaries. The typical redshift ranges of the MBHBs contributing to 90% of the total characteristic strain signal are given by the vertical lines in Fig. 3. These correspond to the median redshift values (across Universe realizations) at which the cumulative contribution – integrated from low and high redshifts, respectively – reaches 5% of the total strain signal. For the low frequency of 3.1 nHz considered here, where the GW signal is expected to be seen as a stochastic background, we find that most of the contribution comes from the range 0.05 < z < 1.2 for the circular population and 0.08 < z < 1.3 for the eccentric population.

|

Fig. 3. Median and 68% confidence interval of the differential contribution to the total characteristic strain signal, based on 2000 Universe realizations, shown across MBHB redshift bins for both circular and eccentric populations. We compare the results at two observer frequencies: 3.1 nHz (left panel) and 27.6 nHz (right panel). The vertical lines represent the median redshift values at which the cumulative contribution (integrating from low and high redshifts, respectively) reaches 5% of the total strain signal for the circular (solid line) and eccentric (dashed line) populations. |

Similar distributions as a function of MBHB chirp mass are shown in Fig. 4. These distributions confirm the findings noted above. The GW signal at low frequencies is mainly formed by heavy systems with chirp mass in the range 108.5 − 109.5 M⊙, while most of the contribution at high frequencies comes from binaries in the range 108 − 109 M⊙. At low frequency, we find that the contribution to the total strain signal extends to higher masses for the eccentric population relative to the circular population. The main reason is the contribution of the massive and eccentric binaries with orbital periods around and even below the 0.5/Tobs frequency, emitting at higher orbital harmonics. The typical lower bound on the chirp mass of MBHBs contributing 90% of the total characteristic strain signal is indicated by the vertical lines in Fig. 4. These represent the median chirp mass values (across Universe realizations) at which the cumulative contribution (integrated from the lowest masses) reaches 10% of the total strain signal, for each population. We find  for the circular population and log10(ℳc/M⊙)≳8.63 for the eccentric population.

for the circular population and log10(ℳc/M⊙)≳8.63 for the eccentric population.

|

Fig. 4. Median and 68% confidence interval of the differential contribution to the total characteristic strain signal, based on 2000 Universe realizations, shown across MBHB log10-chirp mass bins for both circular and eccentric populations. We compare the results at two observer frequencies: 3.1 nHz (left panel) and 27.6 nHz (right panel). Vertical lines represent the median chirp mass value at which the cumulative contribution (integrating from lower masses) reaches 10% of the total strain signal for the circular (solid line) and eccentric (dashed line) populations. |

4.2.3. Number of contributing MBHBs

In this section, we aim to quantify the number of MBHBs that effectively contribute to the strain power spectrum of the GWB. This number is particularly important as it quantifies the validity of the stochasticity and Gaussianity assumption for the GWB signal in the PTA band. To estimate this number, we use two complementary metrics. The first, suggested in Bécsy et al. (2022), computes how many binary signals must be summed, starting from the brightest, to reach a fraction αtot of the total GWB power in a given observer frequency bin centered at f. This can be expressed as

where the summation in the numerator is performed over the merger population in decreasing order of hc2. We use Eq. (30) to compute each binary’s contribution. In this analysis, we adopt αtot = 0.75, which corresponds to a S/N of 3 for the brightest sources relative to the rest of the MBHB population, defined as  .

.

However, this metric does not quantify the relative contribution of the “brightest sources”. For example, assume that 74% of the GWB power is produced by a few binaries and the remaining 1% needed to reach 75% comes from 999 MBHBs, in this case, we would obtain N75 = 1000 even though the GWs from the population are dominated by one system. To capture this potential problem, we suggest another measure, Neff, inspired by the effective sample size of a Markov Chain, derived in Elvira et al. (2022), which can be written as

where Nb is the total number of inspiralling binaries contributing to the strain signal at frequency f. One can verify that Neff equals Nb if the GW signal originates from a population of equally contributing binaries. However, if 99% of the GW signal from a population is produced by a single binary, Neff will be much closer to 1, as desired.

The (effective) number of binaries that contribute the most to the total GW strain across the PTA frequency band is presented in Fig. 5. The results for N75 are given as error boxes and median Neff values are presented by circles for the circular population and crosses for the eccentric population, for our 2000 Universe realizations. Below 10 nHz, for both populations, the typical number of binary signals that must be added to reach 75% of the background signal is greater than 300, indicating that the stochastic approximation seems justifiable at those frequencies. However, around and above fyr, for 25% of the Universe realizations, N75 is lower than 10, which is not sufficiently high to apply the central limit theorem. The eccentric background has a factor ≈10 greater number of contributors (N75) around fyr due to the distributed spectrum of GW emission and therefore maintains stochasticity to higher frequencies.

|

Fig. 5. Comparison of the effective number of binaries in terms of N75 and Neff contributing to the GWB at each observed frequency bin of a PTA with an observing duration of 10.3 years as for EPTA Collaboration (2023a). At each observer frequency, the two extreme horizontal lines represent the 5th and 95th quartiles of the N75 distribution, derived from 2000 Universe realizations. The edges and the central line of the box represent the 25th, 50th, and 75th quartiles, respectively. For Neff, we only show the median of the distribution at each observer frequency with blue dots for the circular population and orange crosses for the eccentric population. |

As the effective number of binaries, Neff, does not have a direct physical interpretation, we only compare the median values of N75 and Neff at each frequency to quantify the variation in the relative contributions of the binaries counted in N75. We find that at low frequencies, N75 is about two orders of magnitude larger than Neff for both populations. This suggests that the contribution to the total GW strain is highly uneven among binaries. In the lowest frequency bin, although around 10 000 binaries produce 75% of the background signal, only hundreds of them are significantly contributing to the signal. At frequencies below 10 nHz, even the Neff metric indicates the presence of at least tens of sources per bin, suggesting that it could be well described as a stochastic GWB.

At higher frequencies, the contributions are more balanced and point to a number of contributing binaries from a few up to several dozen binaries. This implies that at higher frequency, the background is less likely to be well approximated by a Gaussian noise and therefore is less similar to the conventional definition of a background. Taking the frequency range as a whole, one might conclude that detecting individual sources is unlikely due to the large number of contributing binaries, especially at low frequencies. However, even if the fractional contribution of an individual source is small, the cumulative effect of observing multiple pulsars within a given PTA can enhance its detectability. Furthermore, the detectability of an individual binary by a PTA must consider both pulsar noise and the detector response to GWs. This is examined in the next section, where we investigate how to pass from the properties of the strain signal to the PTA observables.

5. Implications for pulsar timing array observations

To accurately compare the theoretical signal computed from the HORIZON-AGN population with the one currently measured by PTA experiments, we must study the properties of the GWB-induced timing residuals. Timing residuals are the time difference between the measured times of arrival (ToAs) of radio pulses from Galactic millisecond pulsars and the ToAs predicted by a theoretical model, referred to as the timing model (Edwards et al. 2006). The residuals also carry an imprint from GWs; in particular, a GWB would appear as a common correlated signal with a spatial correlation pattern first derived in Hellings & Downs (1983).

5.1. Methodology

In this section we present two methods for estimating the spectral properties of the timing residuals induced by the MBHB population. We emphasize the importance of considering what affects the spectral inference of the detector (here the PTA), to avoid potential biases when interpreting its results. We also outline our methodology for identifying potentially resolvable individual binaries within the population.

5.1.1. The Gaussian ensemble approach

This approach considers the GWB signal generated by an MBHBs population as a Gaussian ensemble (see e.g., Rosado et al. 2015; Romano & Cornish 2017; Hazboun et al. 2019; Agazie et al. 2023b; EPTA Collaboration 2024a). In this case, the GW strain is considered as a random variable, fully characterized by its one-sided power spectral density (PSD), Sh(f) = hc2(f)/f. If one assumes that the GWB signal is stationary, isotropic and un-polarized, the average timing residuals response is given, in terms of PSD, by (Bertotti et al. 1983; Jenet et al. 2006)

The timing residual PSDs from the different Universe realizations obtained using this method have two limitations. First, they do not account for the fact that the signal is produced by a discrete number of sources, each with its own response to the PTA. Second, the derivation of hc2 that leads to the timing residuals PSD  , assumes that each MBHB contributes a Dirac delta function at its orbital frequency harmonics as in Eq. (30). We recall below that this is only the case in the limit of an infinitely long dataset6. For realistic PTA data, the effect of the finite observation duration on spectral estimation needs to be considered a priori. We use a second method for evaluating

, assumes that each MBHB contributes a Dirac delta function at its orbital frequency harmonics as in Eq. (30). We recall below that this is only the case in the limit of an infinitely long dataset6. For realistic PTA data, the effect of the finite observation duration on spectral estimation needs to be considered a priori. We use a second method for evaluating  that accounts for both of these issues in the following subsection.

that accounts for both of these issues in the following subsection.

5.1.2. The population approach

The principle of this approach is to compute the GWB-induced timing residuals by summing the contributions of each individual MBHB (see e.g. Bécsy et al. 2022). This requires knowledge of the waveform for any set of orbital parameters. For this approach, we consider only circular binaries.

The exact residuals induced for a given pulsar by an inspiralling MBHB depend on their relative position, the binary inclination angle ι to the line of sight and the polarization angle ψ. The time series of timing residuals is composed of two terms, corresponding to the impact of the GW strain at the time of emission of the radio pulses (referred to as the Pulsar term) and at the time of their reception (referred to as the Earth term; Detweiler 1979). The correlation between GWB timing residuals among pulsars is entirely due to the Earth term. Thus, in the following, we only consider the GW strain signal of the Earth term when computing the GWB timing residuals power spectrum. We assume GWB to be isotropic, reflecting the distribution of MBHBs across the sky. As a result, we expect the GWB to imprint, on average, the same signal in every pulsar (Hellings & Downs 1983); therefore, we compute the GWB spectrum for only one pulsar and assume that it is the same for the other pulsars in the array.

As shown in Hazboun et al. (2019), for a finite observing duration Tobs, the Fourier transform of the GW residuals induced by a circular MBHB located at a given sky position  at redshift z and emitting GW at fGW = 2forb/(1 + z) in the observer frame, takes the form

at redshift z and emitting GW at fGW = 2forb/(1 + z) in the observer frame, takes the form

where ϕ0 is an (arbitrary) initial GW phase and the amplitude R0 depends on the intrinsic properties of the binary:

where we introduced the redshifted chirp mass ℳc, z = (1 + z)ℳc. The residuals amplitude is modulated by the complex geometric factor  given as

given as

where we introduced the antenna pattern response function for both + and × polarization modes that depends on the sky position of the pulsar and binary as well as on the polarization angle ψ. Their exact expressions can be found in Ellis et al. (2012). Finally, we must correctly take into account the finite duration of the PTA observations (Tobs) by introducing the edge effect into the Dirac delta function:

Contrary to the previous case where we considered Dirac delta functions as a contribution of each MBHB, the finite width of the sinc function leads to spectral leakage in the non-white PSD. As a result, every MBHB can potentially contribute to several frequencies, which makes frequency bins correlated. It is common practice in signal processing to taper the time series to minimize the effect of spectral leakage (Percival & Walden 1993). However, in current PTA data analysis, no such pre-processing is applied to the timing residuals time series, so it might, a priori, affects the inference of the PSD. This suggests that even MBHBs emitting GWs at frequencies much lower than the PTA frequency (1/Tobs) could contribute to the GWB power inferred in the PTA band due to spectral leakage.

The spectral leakage could (at least partially) be mitigated by the timing model. A part of the timing model fits and removes linear and quadratic trends in the PTA residuals that could be caused by the spin-down in the millisecond pulsars. Obviously, it also removes some very low-frequency GWs covariant with such a trend (Cordes & Shannon 2010; van Haasteren & Levin 2013). As a result, it can significantly reduce the dynamical range in the expected PSD and decrease the effect of spectral leakage. An effect already discussed in Taylor et al. (2013), Lentati et al. (2013). However, the timing model cannot be a replacement for a well-designed taper that controls the leakage. Nonetheless, the timing model acts as a high-pass filter that removes very low-frequency GWB (≲1/Tobs) from the pulsar timing residuals (Hazboun et al. 2019). As a result, we consider only MBHBs that emit GWs with fGW > 1/(2Tobs) in order to reduce the numerical cost of the GWB computation without affecting its inferred properties in the PTA frequency band.

We produce realistic GWB timing residuals by summing the contributions from all MBHBs of a given Universe realization, uniformly drawing the sky location, polarization angle, and initial phase for each binary. However, since the number of MBHBs contributing to the PTA band typically exceeds millions, we employed a numerical simplification, which allowed us to carry out this procedure more efficiently; the procedure is described in Appendix B. Once the GWB timing residuals waveform  is obtained, we can return to the time domain and infer the GWB PSD using the data analysis procedure commonly employed in the PTA community. In the following, we briefly discuss the PSD inference procedure used for PTA data.

is obtained, we can return to the time domain and infer the GWB PSD using the data analysis procedure commonly employed in the PTA community. In the following, we briefly discuss the PSD inference procedure used for PTA data.

5.1.3. The GWB spectral inference in PTA

The GWB analysis performed by PTA collaborations is based on the modeling of the timing residuals data (intrinsic red noise, dispersion measure variations, GWB, etc.) using Gaussian processes. Each noise component X is modeled using a truncated Fourier basis where the  coefficients

coefficients  , are distributed according to a multivariate Gaussian with a covariance matrix reflecting the underlying process, characterized by its PSD

, are distributed according to a multivariate Gaussian with a covariance matrix reflecting the underlying process, characterized by its PSD  :

:

This defines a prior for the noise Fourier coefficients, that depends on some parameters θX, which characterize the PSD of the process. It is then usual procedure to marginalize over these coefficients so that the PTA likelihood depends only on the PSD parameters θX (Lentati et al. 2013; van Haasteren & Vallisneri 2014). The observation time Tobs, in Eq. (40), is defined depending on whether the noise component, X, is intrinsic to a specific pulsar or not. If it is intrinsic, Tobs is the observation duration of that pulsar. If X is a common process, such as a GWB, Tobs is the total observation duration of the PTA.

There are two main methods for inferring the timing residuals PSD, Sr(f). The first introduces the parametrized description resulting from a particular physical model. For example, the population of inspiralling binaries should produce a characteristic strain described by a power law (Phinney 2001):

which implies a power-law form  for the timing residuals PSD with γ = 3 − 2α, using Eq. (35). The spectral index γ and an amplitude at fiducial frequency fyr = 1/yr are inferred from the data using a Bayesian framework. This requires a choice of prior for the GWB parameters θGWB = (Ayr,γ). We use a log-uniform prior for the GWB amplitude, log10Ayr ∈ [ − 18, −10] and a uniform prior for its spectral index, γ ∈ [0, 7].

for the timing residuals PSD with γ = 3 − 2α, using Eq. (35). The spectral index γ and an amplitude at fiducial frequency fyr = 1/yr are inferred from the data using a Bayesian framework. This requires a choice of prior for the GWB parameters θGWB = (Ayr,γ). We use a log-uniform prior for the GWB amplitude, log10Ayr ∈ [ − 18, −10] and a uniform prior for its spectral index, γ ∈ [0, 7].

In the second approach, often referred to as “free spectrum”, we infer directly the values Sr(fk) at a set of harmonics fk = k/Tobs assuming that they are independent (Lentati et al. 2013; Taylor et al. 2013). More specifically, the inferred quantities are the residuals root-mean-square (RMS),  . Here, we only sample the RMS coefficients up to fyr, choosing a log-uniform prior for each

. Here, we only sample the RMS coefficients up to fyr, choosing a log-uniform prior for each ![$ \log_{10} \left({\rho_{\mathrm{r}}^{(\mathrm{GWB})}}(f_k) / \text{ s}\right)\in [-10, -4] $](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa55539-25/aa55539-25-eq74.gif) . This method is model-agnostic, but constrained by the assumption of independence of estimate at each frequency bin. Given the current poor sensitivity of PTAs, both approaches give a consistent estimate of the signal PSD (see Agazie et al. 2024).

. This method is model-agnostic, but constrained by the assumption of independence of estimate at each frequency bin. Given the current poor sensitivity of PTAs, both approaches give a consistent estimate of the signal PSD (see Agazie et al. 2024).

In the following, we apply this PTA Bayesian spectral estimation method to the GWB-induced timing residuals of a single pulsar, obtained using the population approach described above. Since we are only interested in the accuracy of the spectral inference and its potential limitations (e.g., regarding spectral leakage), we simplify simulated PTA data and include/consider only white noise residuals in addition to the GWB timing residuals associated with each Universe realization7.

5.1.4. Searching for bright individual binaries

In the previous sections, we refer to the GW signal from the MBHB population as a GWB. However, the population modeling approach emphasizes that the signal is, in reality, a sum of individual sources. As a result, it could be that the GW signal consists of a few resolvable bright binaries, referred to as continuous wave (CW) in the following, on top of the stochastic GWB (Sesana et al. 2008). To quantify the potential detectability of individual sources, we evaluate the S/N of the brightest binaries for our 2000 Universe realizations, using two toy PTA datasets. We then consider a CW with an S/N greater than 3 as a potentially detectable individual binary. This calculation applies only to the population modeling, and thus, for this study, to the circular ensemble.

We identify the CW candidates as follows. First, for each Universe realization, we obtain a list of potential CW candidates by identifying the individual binaries with the highest residuals amplitude R0 across a frequency grid covering the PTA sensitivity band. For each of these brightest candidates, we then compute the associated GWB ‘noise’ excluding the CW candidate waveform,  . We then apply a Hanning window function wHanning to limit spectral leakage (Harris 1978) and then compute its periodogram to estimate its PSD. This effectively gives

. We then apply a Hanning window function wHanning to limit spectral leakage (Harris 1978) and then compute its periodogram to estimate its PSD. This effectively gives

The obtained GWB noise PSD is used to compute the CW candidate optimal match filtering S/N (see e.g., Creighton & Anderson 2011) for the PTA with a noise covariance matrix, CPTA, as

where the CW residuals vector rCW is the concatenation of the CW residuals for the different pulsars of the PTA. The noise covariance matrix CPTA of the PTA is constructed using the enterprise software (Ellis et al. 2020). The noise matrix contains four contributions. The first one is the result of the timing model marginalization (TMM) procedure and can be seen as a transmission function reducing the sensitivity at low frequencies and removing 1/year frequency from the analysis (see discussion above and Hazboun et al. 2019). The second contribution is an intrinsic timing red noise component for each pulsar of the PTA with a PSD modeled as a power law,  . We set log10Ayr = −13.5 and γiRN = 3, for all the pulsars of our toy PTAs; this corresponds to the typical noise process properties found in EPTA Collaboration (2023b). The third component is the white noise characterized by

. We set log10Ayr = −13.5 and γiRN = 3, for all the pulsars of our toy PTAs; this corresponds to the typical noise process properties found in EPTA Collaboration (2023b). The third component is the white noise characterized by  , where (i) σPTA is the typical residuals RMS due to the radio telescope noise and pulse jitter (Shannon & Cordes 2012) defined above (ii) Δtobs is the observation cadence, which we assume to be constant and equal across pulsars. Finally, we include the GWB, which is correlated among pulsars, using Eq. (42) and the Hellings-Downs correlation function (Hellings & Downs 1983). We note that this assumes that the GWB noise PSD is the same for all the pulsars in the toy PTA, which is a reasonable assumption for an isotropic stochastic background.

, where (i) σPTA is the typical residuals RMS due to the radio telescope noise and pulse jitter (Shannon & Cordes 2012) defined above (ii) Δtobs is the observation cadence, which we assume to be constant and equal across pulsars. Finally, we include the GWB, which is correlated among pulsars, using Eq. (42) and the Hellings-Downs correlation function (Hellings & Downs 1983). We note that this assumes that the GWB noise PSD is the same for all the pulsars in the toy PTA, which is a reasonable assumption for an isotropic stochastic background.

The simulated PTAs and noise parameters are given in Table 1. The EPTA configuration is based on the properties of the EPTA DR2new dataset presented in EPTA Collaboration (2023c), while the SKA represents an expected configuration of the future SKA dataset (Janssen et al. 2015), choosing a similar observation duration as for EPTA. For each toy PTA and each Universe realization, we randomly assign sky positions to pulsars, uniformly distributed across the sky, and draw their distances from Earth from a normal distribution with a mean of 1 kpc and a standard deviation of 0.1 kpc. Assuming an isotropic pulsar distribution reduces the dependence of the detectability of a CW candidate on the pulsars’ positions and distances.

Configuration of the two toy PTAs used to infer the detectability of individual MBH binary.

5.2. Results

5.2.1. Comparison with EPTA results

We now examine the properties of the timing residuals induced by the GW signal from our MBHB population. We compare our theoretical expectations, based on the Gaussian ensemble (GE) and population approaches described above, with the current EPTA results obtained with the DR2new dataset, which includes residuals from 25 millisecond pulsars observed over a duration of TEPTA ≃ 10.3 years (EPTA Collaboration 2023c). PTA collaborations are providing the estimated residuals PSD using a power law and a free spectrum model. For the population approach, we compare the GWB spectral inference with and without the TMM procedure described above to quantify its performance on reducing spectral leakage effects.

Our comparison for the power-law PSD model is shown in Fig. 6, where the EPTA results are shown as red dotted lines in both panels. The results using the GE approach are given in the left panel. We show the power-law parameters obtained from a least-squares fit using a power law (assuming Eq. (41) and using Eq. (35)) on the PSD produced by the population for each of the 2000 Universe realizations. We apply the same weight to each observer frequency fk for the least-squares fit. For the population approach, we combine the maximum-a-posteriori samples obtained from the PTA Bayesian spectral inference (using a power-law PSD model) on the timing residuals derived from our 2000 Universe realizations.

|

Fig. 6. Distributions of the amplitude Ayr at fyr and the spectral index γ, which parameterize the GWB timing residuals PSD, derived from 2000 Universe realizations, are compared with the EPTA results (red dotted contours) of EPTA Collaboration (2023a). The 68% and 90% confidence regions are shown for all distributions. Left panel: Distributions obtained via power-law least-squares fits to spectra from the Gaussian ensemble (GE) method for the circular (blue) and eccentric (orange) populations are shown as filled contours. Right panel: Distributions of maximum-a-posteriori power-law parameters from PTA-like inference using the GWB timing residuals from the population (Pop) approach. Solid contours represent the standard data analysis procedure that includes TMM; dashed contours represent the analysis without TMM. The effects of spectral leakage on the inference are clearly visible without TMM and remain measurable even when TMM is included. In both panels, the expected spectral index, γ = 13/3, of the average spectrum from a population of circular binaries driven by GW emission, is shown as a black vertical line. Note: γ relates to the characteristic strain spectral index α via γ = 3 − 2α. |

Using the GE approach, we find that circular MBHBs would induce a slightly steeper residual PSD than expected from the Phinney average power law, γ = 13/3 ≃ 4.33 (α = −2/3 in terms of hc), with a 90% confidence interval of  . For the associated characteristic strain at fyr, we find

. For the associated characteristic strain at fyr, we find  . The eccentric population produces shallower spectra with a 90% confidence interval of

. The eccentric population produces shallower spectra with a 90% confidence interval of  , and induces a similar amplitude at fyr, of

, and induces a similar amplitude at fyr, of  . For circular and eccentric ensembles, when using the GE approach, we recover a background that is steeper and fainter (at fyr) compared to the observations from the EPTA.

. For circular and eccentric ensembles, when using the GE approach, we recover a background that is steeper and fainter (at fyr) compared to the observations from the EPTA.

We compare results using the population approach and the PTA Bayesian spectral inference method in the right panel of Fig. 6. First, as shown by the blue solid contours, the PTA inference which includes TMM leads to a distribution of power-law parameters that is much broader than the GE approach. This is expected because the population approach accounts for both the realistic pulsar response to binary signals – which reduces the effective number of binaries contributing to the pulsar timing residuals – and the limited sensitivity of the PTA, unlike the GE approach. We find 90% confidence intervals of  and

and  for our 2000 Universe realizations. The extension of the spectral index posterior toward lower values, around 3, along with an increase in the background amplitude at fyr, is likely due to residual spectral leakage effects.

for our 2000 Universe realizations. The extension of the spectral index posterior toward lower values, around 3, along with an increase in the background amplitude at fyr, is likely due to residual spectral leakage effects.

Let us say a few more words about the importance of spectral leakage in the inference of the GWB. The dashed blue contours give the posterior distribution of the inferred GWB spectra without TMM. As mentioned above, TMM works as a kind of low-pass filter, which reduces the spectral dynamical range and, therefore, reduces the leakage. The effect of GWB spectral leakage is obvious in this case: the posterior is significantly biased toward higher amplitudes and shallower spectra, with a 90% confidence interval  and

and  . If spectral leakage is improperly handled, each individual binary, as expressed in Eq. (36), contributes to the GWB spectral inference with a decaying tail ∝1/f2 at high frequencies. As a consequence, the more massive (and more numerous) binaries orbiting at low frequencies artificially contribute to the GWB spectrum at much higher frequencies than their actual GW frequency. Although the TMM procedure significantly filters out low-frequency contribution it does not eliminate the leakage completely, which still contributes to the shallower spectra part of the posterior depicted by the solid line. We note that this effect is more evident for the more sensitive SKA toy PTA, where we find a 90% confidence interval of

. If spectral leakage is improperly handled, each individual binary, as expressed in Eq. (36), contributes to the GWB spectral inference with a decaying tail ∝1/f2 at high frequencies. As a consequence, the more massive (and more numerous) binaries orbiting at low frequencies artificially contribute to the GWB spectrum at much higher frequencies than their actual GW frequency. Although the TMM procedure significantly filters out low-frequency contribution it does not eliminate the leakage completely, which still contributes to the shallower spectra part of the posterior depicted by the solid line. We note that this effect is more evident for the more sensitive SKA toy PTA, where we find a 90% confidence interval of  . The asymmetry in the confidence interval toward shallower spectra is highlighting the impact of spectral leakage on the PTA spectral inference, even when the TMM is included8. Both the increase in amplitude at fyr and the decrease in spectral index induced by spectral leakage tend to align the inferred properties of the GWB signal from the HORIZON-AGN MBHB population with EPTA observations. We claim that this should be further investigated as a potential bias in the PTA spectral inference pipeline.

. The asymmetry in the confidence interval toward shallower spectra is highlighting the impact of spectral leakage on the PTA spectral inference, even when the TMM is included8. Both the increase in amplitude at fyr and the decrease in spectral index induced by spectral leakage tend to align the inferred properties of the GWB signal from the HORIZON-AGN MBHB population with EPTA observations. We claim that this should be further investigated as a potential bias in the PTA spectral inference pipeline.

To have a more comprehensive view of what is happening across the PTA band, we compare our results with observations, using the model-agnostic free spectrum approach for the residuals PSD. The results are presented in Fig. 7. For clarity and because the spectral uncertainties are much smaller for the GE approach, we show only the average spectrum for the circular (solid blue line) and eccentric (dashed orange line) ensembles, omitting their corresponding confidence regions. The spectrum produced by the circular population is slightly steeper than the free spectrum suggests, while the eccentric population better fits the observed EPTA free spectrum (red violins). For the population approach, we evaluated the free spectrum with (dashed blue violins) and without TMM (solid light blue violins). The analysis without TMM again clearly exhibits the spectral leakage at high frequencies as a flattening tail. And once again, we do observe that TMM does not completely eliminate the leakage in some Universe realizations. This remains a concern, as overestimating the GWB amplitude at fyr can skew the astrophysical interpretation of the signal.

|

Fig. 7. Comparison of the GW residuals RMS induced by the HORIZON-AGN population, using different modeling and populations, with the spectrum measured by the EPTA collaboration, shown in red. The average GE spectra of both circular and eccentric ensembles are depicted as solid and dashed lines, respectively. The distribution of the maximum-a-posteriori samples for the GWB spectra of the 2000 Universe realizations obtained using the population (Pop) method and a realistic PTA-like inference with and without TMM, are shown in dashed contours and light blue color, respectively, for the circular population. The effect of spectral leakage on the GWB inference results in a shallower spectral shape, significantly biasing the inference when TMM is not included. For some Universe realizations, spectral leakage still has appreciable effects at high frequencies even when TMM is applied. |

5.2.2. Likelihood of individually resolvable binaries

Using the method described in Sect. 5.1.4, we go on to assess the presence of binaries with an S/N greater than 3. We refer to these as CW candidates, attributed to each of our 2000 Universe realizations and for the two toy PTAs.