| Issue |

A&A

Volume 703, November 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A158 | |

| Number of page(s) | 37 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554908 | |

| Published online | 28 November 2025 | |

KiDS-Legacy: Cosmological constraints from cosmic shear with the complete Kilo-Degree Survey⋆

1

Ruhr University Bochum, Faculty of Physics and Astronomy, Astronomical Institute (AIRUB), German Centre for Cosmological Lensing, 44780 Bochum, Germany

2

School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics, Newcastle University, Herschel Building, NE1 7RU Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK

3

Center for Theoretical Physics, Polish Academy of Sciences, al. Lotników 32/46, 02-668 Warsaw, Poland

4

Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh EH9 3HJ, UK

5

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, P.O. Box 9513 2300 RA, Leiden, The Netherlands

6

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK

7

Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, D-53121 Bonn, Germany

8

Institute for Computational Cosmology, Ogden Centre for Fundament Physics – West, Department of Physics, Durham University, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK

9

Centre for Extragalactic Astronomy, Ogden Centre for Fundament Physics – West, Department of Physics, Durham University, South Road, Durham DH1 3LE, UK

10

Waterloo Centre for Astrophysics, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada

11

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada

12

Institute for Theoretical Physics, Utrecht University, Princetonplein 5, 3584CC Utrecht, The Netherlands

13

Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, PO Box 800 9700 AV, Groningen, The Netherlands

14

Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology, Campus UAB, 08193 Bellaterra (Barcelona), Spain

15

School of Mathematics, Statistics and Physics, Newcastle University, Herschel Building, NE1 7RU Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK

16

Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (CIEMAT), Av. Complutense 40, E-28040 Madrid, Spain

17

Institute of Cosmology & Gravitation, Dennis Sciama Building, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth PO1 3FX, United Kingdom

18

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Augusto Righi” – Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Via Piero Gobetti 93/2, 40129 Bologna, Italy

19

INAF-Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio di Bologna, Via Piero Gobetti 93/3, 40129 Bologna, Italy

20

Universität Innsbruck, Institut für Astro- und Teilchenphysik, Technikerstr. 25/8, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria

21

The Oskar Klein Centre, Department of Physics, Stockholm University, AlbaNova University Centre, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden

22

Imperial Centre for Inference and Cosmology (ICIC), Blackett Laboratory, Imperial College London, Prince Consort Road, London SW7 2AZ, UK

23

Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Denys Wilkinson Building, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH, UK

24

Donostia International Physics Center, Manuel Lardizabal Ibilbidea, 4, 20018 Donostia, Gipuzkoa, Spain

25

Zentrum für Astronomie, Universitatät Heidelberg, Philosophenweg 12, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany; Institute for Theoretical Physics, Philosophenweg 16, D-69120 Heidelberg, Germany

26

Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare (INFN) – Sezione di Bologna, viale Berti Pichat 6/2, I-40127 Bologna, Italy

27

Department of Physics “E. Pancini” University of Naples Federico II C.U. di Monte Sant’Angelo Via Cintia, 21 ed. 6, 80126 Naples, Italy

28

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, via dell’Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy

29

Institute for Particle Physics and Astrophysics, ETH Zürich, Wolfgang-Pauli-Strasse 27, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland

⋆⋆ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

31

March

2025

Accepted:

31

July

2025

We present cosmic shear constraints from the completed Kilo-Degree Survey (KiDS), where the cosmological parameter S8 ≡ σ8√Ωm/0.3 = 0.81+0.016−0.021 is found to be in agreement (0.73σ) with results from the Planck Legacy cosmic microwave background experiment. The final KiDS footprint spans 1347 square degrees of deep nine-band imaging across the optical and near-infrared (NIR), along with an extra 23-square degrees of KiDS-like calibration observations of deep spectroscopic surveys. Improvements in our redshift distribution estimation methodology, combined with our enhanced calibration data and multi-band image simulations, allowed us to extend our lensed sample out to a photometric redshift of zB ≤ 2.0. Compared to previous KiDS analyses, the increased survey area and redshift depth results in a ∼32% improvement in constraining power in terms of Σ8 ≡ σ8(Ωm/0.3)α = 0.821+0.014−0.016, where α = 0.58 has been optimised to match the revised degeneracy direction of σ8 and Ωm for our current survey at higher redshift. We adopted a new physically motivated intrinsic alignment (IA) model that jointly depends on the galaxy sample’s halo mass and spectral type distributions, and which is informed by previous direct alignment measurements. We also marginalised over our uncertainty on the impact of baryon feedback on the non-linear matter power spectrum. Compared to previous KiDS analyses, we conclude that the increase seen in S8 primarily results from our improved redshift distribution estimation and calibration, as well as a new survey area and improved image reduction. Our companion paper presents a full suite of internal and external consistency tests (including joint constraints with other datasets), finding the KiDS-Legacy dataset to be the most internally robust sample produced by KiDS to date.

Key words: cosmology: observations / galaxies: photometry / gravitational lensing: weak / surveys

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Our current understanding of the large-scale structure (LSS) of the Universe, obtained over the last three decades thanks to increasingly sophisticated astronomical observations, can be regarded as one of the great successes of modern scientific inquiry. Detailed observations of the LSS probe fundamental physics, since the structures we observe were formed by an interplay of physical effects. These primarily include the self-gravity of matter, cosmic expansion, astrophysical feedback processes, and the repulsive effect of the cosmological constant or dark energy.

When it comes to understanding the growth and evolution of LSS, the cosmological stage is set by observations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) that reveal the structure of dark and baryonic matter at early times. Together with other probes, including big-bang nucleosynthesis (BBN) and baryon-acoustic oscillations (BAOs), the CMB has been used to establish and tightly constrain the so-called standard model of cosmology, ΛCDM. It is a strikingly simple model based on only a handful of numerical parameters (Planck Collaboration VI 2020; Qu et al. 2024; Ge et al. 2025) and characterised, in particular, by two components that are at the origin of its name: a cosmological constant (Λ, which dominates the energy landscape at late times) and a cold dark matter (CDM) component that is dominant over baryonic matter by a factor of roughly five. Observations of the CMB constrain the parameters of this model at high redshift (z ∼ 1100), when the Universe was approximately 370 thousand years old. However, the model can be subsequently used to predict the properties of the LSS at late times (z ≲ 2; an extrapolation over more than 10 billion years), which can then be tested with low-redshift probes of cosmic structures.

Of the low-redshift probes, the relative prevalence of CDM poses a problem for those that rely on luminous tracers, such as galaxy clustering measurements. Modelling and constraining the relationship between luminous and dark matter (DM), also known as galaxy bias, constitutes one of the major systematic challenges of such measurements. In contrast, observations of the weak gravitational lensing effect of the LSS are intrinsically sensitive to all matter (dark or otherwise), eliminating the systematic uncertainty of galaxy bias. This unique feature has turned such ‘cosmic shear’ experiments into a major cosmological probe that is just entering its golden age. Indeed, it is the combination of cosmic shear with galaxy clustering – and their cross-correlation called galaxy-galaxy lensing (GGL) – that will potentially yield the most precise test of the standard model.

Over the past decade, the comparison between observations of low-z LSS and their CMB-based predictions has revealed a tension in the  parameter. Therefore, it has been the focus of extensive study. All contemporary cosmic shear measurements to date, except one, have yielded values of S8 that are lower than CMB predictions, indicating a universe with less structure and/or matter. The significance of these measurements varies, but there is a clear tendency towards lower values in the cosmic shear results of the past decade. Only the Deep Lens Survey (DLS; Jee et al. 2016) has reported a value that is higher than that of Planck, and even then only slightly. In contrast, lower values have been reported by the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Lensing Survey (CFHTLenS; Heymans et al. 2013), as well as from previous results from the ongoing ‘stage-III’ surveys by the Kilo-Degree Survey (KiDS; Asgari et al. 2021; Li et al. 2023a), the Dark Energy Survey (DES; Amon et al. 2022; Secco et al. 2022), the Hyper-Suprime Camera survey (HSC; Li et al. 2023b; Dalal et al. 2023), and a joint analysis by Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration (2023). Other low-z LSS probes typically also share this trend but again with a varying level of significance (see Abdalla et al. 2022, for an overview).

parameter. Therefore, it has been the focus of extensive study. All contemporary cosmic shear measurements to date, except one, have yielded values of S8 that are lower than CMB predictions, indicating a universe with less structure and/or matter. The significance of these measurements varies, but there is a clear tendency towards lower values in the cosmic shear results of the past decade. Only the Deep Lens Survey (DLS; Jee et al. 2016) has reported a value that is higher than that of Planck, and even then only slightly. In contrast, lower values have been reported by the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Lensing Survey (CFHTLenS; Heymans et al. 2013), as well as from previous results from the ongoing ‘stage-III’ surveys by the Kilo-Degree Survey (KiDS; Asgari et al. 2021; Li et al. 2023a), the Dark Energy Survey (DES; Amon et al. 2022; Secco et al. 2022), the Hyper-Suprime Camera survey (HSC; Li et al. 2023b; Dalal et al. 2023), and a joint analysis by Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration (2023). Other low-z LSS probes typically also share this trend but again with a varying level of significance (see Abdalla et al. 2022, for an overview).

Cosmic shear probes relatively low redshifts, and relatively small scales compared to other probes of LSS (see e.g. Figure 1 of Broxterman & Kuijken 2024, for a graphical summary). This makes cosmic shear somewhat more sensitive than other low-z probes to non-linear structure formation and astrophysical effects: the latter mainly involve feedback processes driven by supernovae and active galactic nuclei, collectively referred to below as baryonic feedback. It has therefore been suggested that inaccuracies in the modelling of non-linear scales might be the reason for the tension in S8, rather than a more fundamental cosmological cause (Yoon et al. 2019; Yoon & Jee 2021; Amon & Efstathiou 2022; Preston et al. 2023).

A definitive answer to the reality of the S8 tension is within reach. Currently, three stage-III surveys have finished their observations and are preparing their final analyses; one of which we present here. The next generation of surveys, called stage-IV, are just beginning, represented by the ESA Euclid mission (Euclid Collaboration: Mellier et al. 2025), the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) conducted with the Vera C. Rubin Observatory (Ivezić et al. 2019), the NASA Roman Space Telescope (Spergel et al. 2015), and the Chinese Space Station Optical Survey (Gong et al. 2019). We note that Euclid is expected to yield first cosmologically relevant results in 2026. These stage-IV surveys will soon provide datasets capable of measuring the growth of structure at low z with unprecedented precision.

New facilities and new instruments invariably bring along new challenges owing to, for instance, the novelty of their hardware. Comparatively, the final (usually called ‘legacy’) releases of a survey typically represent the culmination of years or decades of analysis, understanding, and refinement regarding their survey and the associated data. As such, the final releases of stage-III surveys will provide a crucial insight and reference for subsequent lensing studies of LSS with stage-IV surveys.

Here, we present the cosmic shear analysis of the completed Kilo-Degree Survey (KiDS) based on the fifth and final data release (KiDS-DR5; Wright et al. 2024), dubbed KiDS-Legacy. With extensive wavelength coverage enabled by its unique pairing with its near-infrared (NIR) sister survey VIKING (VISTA Kilo-Degree Infrared Galaxy Survey) and with its superb image quality in the r-band, KiDS is the stage-III survey that is arguably most suited to simultaneously leverage high-redshift galaxies and accurately calibrate their redshift distributions. Over the past decade, KiDS has been pushing to increasingly high redshifts, while continuously improving the redshift calibration, shear measurements, shear calibration through image simulations, and methodology to accurately extract cosmological constraints from the imaging data.

This paper represents the culmination of these efforts, providing the most robust and precise analysis of KiDS to date. Our dataset is the largest analysed by KiDS thus far (Sect. 3.1), utilising the most extensive spectroscopic redshift compilation prepared for any cosmic shear analysis (Sect. 3.2), and has been calibrated using the most sophisticated simulations produced for this purpose (Sect. 3.4). Improvements in methodology (Sect. 2) have allowed us to access the highest redshifts (with the most tomographic bins) studied for cosmic shear to date (Sect. 3.4). An efficient workflow for this study was enabled by the new COSMOPIPE analysis framework, which we have also made publicly available. We present null tests of our dataset in Sect. 4. The cosmological results are presented in Sect. 5, discussed in Sect. 6, and summarised in Sect. 7. Additionally, we include supplementary information regarding our power spectrum emulation (Appendix A), on the definition of parameters for our fiducial intrinsic alignment model (Appendix B), construction of band power spectra (Appendix C), covariance validation (Appendix D), Bn-mode exploration (Appendix E), correlation function cosmological analyses (Appendix F), detailed posterior analyses (Appendix G), tables of cosmological constraints (Appendix H), and details of changes made to the analysis and manuscript post-unblinding (Appendix I). Finally, this paper has been released alongside two companion papers: the work of Stölzner et al. (2025) presents an extensive analysis of internal and external consistency tests of the KiDS-Legacy dataset (including joint constraints with other datasets) and the work of Wright et al. (2025) describes the various redshift distribution and bias estimation developments made for KiDS-Legacy.

2. Modelling and theoretical framework

The main cosmic shear observable is the ellipticity correlation between pairs of galaxies. The signal depends on the two-point statistics of the shear and galaxy intrinsic alignment fields, which both trace the matter distribution and therefore depend on cosmological information. For our predictions and sampling, we used COSMOSIS, a modular cosmology pipeline described in Zuntz et al. (2015). We included a number of new and/or modified modules in our analysis, including a COSMOPOWER emulator for non-linear power spectra (Appendix A) and new intrinsic alignment models (Sect. 2.4). In this section, we start with the derivation of cosmic shear power spectra from matter power spectra and then detail our choices of intrinsic alignment models. Next, we introduce our observable two-point statistics, briefly discussing their measurement and prediction methodology. We end this section with a brief review of our analytical covariance modelling.

2.1. Shear power spectrum

Our two-point statistic predictions are calculated from shear (cross-)power spectra of galaxy samples i and j,  , where G stands for ‘gravitational’, which distinguishes these power spectra from intrinsic alignment contributions to the two-point signal. Shear power spectra are given by Limber-approximated projections (Kaiser 1992; LoVerde & Afshordi 2008; Kilbinger et al. 2017) taking the form

, where G stands for ‘gravitational’, which distinguishes these power spectra from intrinsic alignment contributions to the two-point signal. Shear power spectra are given by Limber-approximated projections (Kaiser 1992; LoVerde & Afshordi 2008; Kilbinger et al. 2017) taking the form

where Pm, nl is the non-linear matter power spectrum and fK(χ) is the comoving angular diameter distance. Although the integral in Eq. (1) technically runs over the entire line of sight to the horizon, χhor, in practice, the weak lensing kernel,  , limits the integral to the comoving distance of the furthest galaxy in our sample, expressed as

, limits the integral to the comoving distance of the furthest galaxy in our sample, expressed as

where  is the distribution of comoving distances of galaxies in source sample, i; in practice, we express this in terms of redshift, namely, N(z) dz = nS(χ) dχ. Here, Ωm is the total matter density parameter today, H0 is the Hubble constant, c is the speed of light, and a(χ) is the scale factor normalised to unity today.

is the distribution of comoving distances of galaxies in source sample, i; in practice, we express this in terms of redshift, namely, N(z) dz = nS(χ) dχ. Here, Ωm is the total matter density parameter today, H0 is the Hubble constant, c is the speed of light, and a(χ) is the scale factor normalised to unity today.

2.2. Matter power spectrum

In our cosmic shear analysis, we remained mostly sensitive to Fourier scales 0.1 h/Mpc ≲ k ≲ 1 h/Mpc, with a weighting of scales that depends on the two-point statistic (see Sect. 2.5). These scales are well within the (quasi-) non-linear regime and therefore require an accurate non-linear power spectrum model for their predictions. Currently, there are multiple approaches that can produce non-linear matter power spectra, with varying levels of accuracy, for this range of scales. Here, we followed the most popular approach for cosmic shear analyses, using a method inspired by the halo model and calibrated against simulations. Specifically, we used the Boltzmann solver CAMB (Lewis et al. 2000; Howlett et al. 2012) to estimate the linear matter power spectrum and the augmented halo model ‘HMCODE2020’ (Mead et al. 2021) to derive its non-linear evolution.

HMCODE2020 has a similar level of accuracy as popular emulators trained directly on N-body simulations (2.5%; see e.g. Knabenhans et al. 2023; Aricò et al. 2021) and is twice as accurate as HALOFIT from Takahashi et al. (2012), which has been used in a number of previous cosmic shear analyses (see e.g. Amon et al. 2022; Hikage et al. 2019). Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration (2023) presented a comparison of HMCODE2020 and HALOFIT with EUCLIDEMULATORV2, showing that HMCODE2020 produces unbiased results when analysing mock data created with EUCLIDEMULATORV2; meanwhile HALOFIT tends to overestimate power for lower values of S8, resulting in an underestimated S8 value. Similarly, an earlier version of HMCODE, HMCODE2015 (Mead 2015), which was used in previous KiDS analyses, is ∼30% less accurate than HMCODE2020. This can subsequently produce small differences between cosmological constraints estimated using the two codes: Tröster et al. (2021) demonstrated that the most important difference between these versions of HMCODE is in their treatment of baryon feedback, which results in a slightly higher S8 using HMCODE2020. Lastly, we note that the parameter values at which HMCODE was fitted to simulations are somewhat more constrained than our chosen priors for h2Ωm(see Mead et al. 2021, and Table 3). However, given that the fitting functions of HMCODE are based on physically motivated parameters, we did not anticipate any significant issues just beyond this range. Furthermore, we note that our analysis remained unaffected by this choice.

2.3. Baryonic feedback

The primary features of the matter power spectrum can be determined by assuming all matter is in the form of (pressureless) CDM, with modifications due to processes involving baryonic matter. At large scales (0.05 h/Mpc ≲ k ≲ 0.5 h/Mpc), BAOs produce oscillations in the power spectrum. Over a wide range of intermediate scales (0.1 h/Mpc ≲ k ≲ 10 h/Mpc), power is suppressed through feedback processes from active galactic nuclei (AGN), reaching a maximum suppression at around k ∼ 5 h/Mpc. At even smaller scales (k ≳ 10 h/Mpc), star formation processes lead to a sharp increase in power (see e.g. Semboloni et al. 2011).

To model baryonic feedback processes, HMCODE2020 performs a modification to the concentration-mass relation of the halo profiles as a function of their gas fraction; this, in turn, depends on the strength of the AGN feedback (parametrised by log(TAGN) ∈ [7.1,8.3]). This feedback model is then calibrated against a suite of hydrodynamical simulations from BAHAMAS (McCarthy et al. 2017), which had been generated using a wide range of effective feedback amplitudes and cosmological models. Recently, Schaye et al. (2023, FLAMINGO) presented a new suite of hydrodynamical simulations, including emulators for generating power spectra (Schaller et al. 2025), as a mechanism for modelling baryonic effects. Moving beyond hydrodynamical simulations, Salcido et al. (2023, SP(k)) presented alternative phenomenological models for the same purpose, while Schneider & Teyssier (2015), Aricò et al. (2020) presented perturbative models that act directly on the outputs of dark-matter only simulations and can be empirically calibrated (Grandis et al. 2024; Schneider et al. 2022). We did not utilise these models for our cosmological analyses here, as these models were published over the course of the analysis of KiDS-Legacy or were not (at time of writing) implemented within our COSMOSIS sampling framework. However, we note that a reanalysis of our data with these models is a natural and straightforward project that will be undertaken in a future publication.

2.4. Intrinsic alignments

The intrinsic alignment (IA) of galaxies is correlated with the observed ellipticities of galaxy images, making them indistinguishable from the cosmic shear effect we wish to probe for cosmological parameter estimation. In the limit of small shears and IA, the two-point statistics of galaxy ellipticities are given by

where  is the cosmic shear signal given by Eq. (1). Analogous Limber equations can be derived for IA contributions, which are typically grouped into two categories. First, intrinsic-intrinsic (II) correlations represent the correlated alignment of galaxies that are tidally aligned by the same ambient LSS:

is the cosmic shear signal given by Eq. (1). Analogous Limber equations can be derived for IA contributions, which are typically grouped into two categories. First, intrinsic-intrinsic (II) correlations represent the correlated alignment of galaxies that are tidally aligned by the same ambient LSS:

Second, shear-intrinsic (GI) correlations are driven by the mutual gravitational effects of LSS on (i) galaxies within the structures, and (ii) the lensed images of background sources that these structures produce (Hirata & Seljak 2004):

with  . In Eqs. (4) and (5) the power spectra PII, X and PδI, X are given by the chosen IA model. We note that the IA contributions feature a more compact kernel along the line of sight than the lensing kernel in Eq. (1), and hence the Limber approximation is poorer for these signals. However, this effect is not significant for our analysis, as the overall IA contributions to the total signal is small, making up only around 10 percent of the signal in our analysis. Additionally, we are only probing scales ℓ ≳ 50, where the Limber approximation is sufficient even for more compact kernels (Leonard et al. 2023).

. In Eqs. (4) and (5) the power spectra PII, X and PδI, X are given by the chosen IA model. We note that the IA contributions feature a more compact kernel along the line of sight than the lensing kernel in Eq. (1), and hence the Limber approximation is poorer for these signals. However, this effect is not significant for our analysis, as the overall IA contributions to the total signal is small, making up only around 10 percent of the signal in our analysis. Additionally, we are only probing scales ℓ ≳ 50, where the Limber approximation is sufficient even for more compact kernels (Leonard et al. 2023).

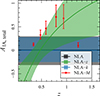

Since IA are caused by the local matter environment, they have a different redshift scaling than lensing, which however is insufficient to isolate the cosmological signal without substantial information loss (Joachimi et al. 2008). Therefore, cosmic shear analyses opt for physically motivated IA models that are inferred jointly with the cosmology (see Lamman et al. 2024, for a review of the field). Guided by this, we implement four IA models in KiDS-Legacy: a widely used baseline with a single overall amplitude parameter (NLA, Sect. 2.4.1), two minimal extensions of NLA with either an additional redshift (NLA-z, Sect. 2.4.2) or scale dependence (via our restricted TATT model, NLA-k; Sect. 2.4.3), and a version of NLA that explicitly incorporates the well-established trends of IA with galaxy type and host halo mass (NLA-M, Sect. 2.4.4). The latter model is the fiducial model chosen for our cosmological analyses.

2.4.1. The non-linear linear alignment (NLA) model

The so-called NLA model (Bridle & King 2007) assumes that the intrinsic ellipticity of a galaxy depends linearly on its surrounding tidal quadrupole (Catelan et al. 2001). Moreover, it is commonly assumed that it is the tidal field at some early time during the formation of the galaxy that sets the amplitude of alignment (Hirata & Seljak 2004). This leads to the following expressions for the IA power spectra,

where C1ρcr ≈ 0.0134 is a constant and D(z) is the linear growth factor normalised to unity at z = 0. The model is empirically extended to non-linear scales by employing the full, non-linear matter power spectrum Pm, nl, encapsulating a mixture of non-linear gravitational effects as well as alignment processes on the scales of dark matter halos (cf. Schneider & Bridle 2010). The model has a single free parameter, namely, the global, dimensionless amplitude AIA, which necessitates the assumption that there are no coherent trends in how galaxy ellipticities respond to their local tidal field within the survey’s galaxy population. Since AIA is well-constrained by tomographic cosmic shear data, we chose a wide top-hat prior for AIA to ensure its posterior is data-driven. All previous KiDS cosmic shear analyses have used the NLA model as their default and, to date, there has been no evidence that this simple prescription is insufficient in representing current-generation datasets (e.g. Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration 2023).

2.4.2. Additional redshift dependence (NLA-z)

There is currently no observational evidence of redshift evolution in the amplitude of IA (Joachimi et al. 2011; Fortuna et al. 2021a), but the statistical uncertainties on measurements underpinning this statement are still large, especially when extrapolated to the redshift range of cosmic shear samples. Moreover, AIA could also acquire an effective redshift scaling; for example, due to a combination of a luminosity dependence and Malmquist bias. Hence, we tested whether the data prefer AIA to evolve over the tomographic bins. Since individual IA amplitudes per tomographic bin are poorly constrained (see the detailed analysis in Samuroff et al. 2019), we chose an extended model that is linear in terms of the scale factor,

where ⟨a⟩(i) is the average scale factor in tomographic bin i, evaluated using the estimated N(z). The parameter AIA thus is the IA amplitude at apiv ≈ 0.769, which corresponds to the commonly chosen pivot of z = 0.3 for IA studies (Joachimi et al. 2011). We set the prior range of the second parameter, BIA, by fitting our linear amplitude dependence to the compilation of KiDS and SDSS measurements studied in Fortuna et al. (2021a, see their Figure 10). Increasing the resulting constraint by 50 %, to account for the limited coverage of these calibration samples and for potential additional implicit redshift dependencies, we obtain a Gaussian prior on BIA with mean −3.7 and standard deviation 4.3. For direct comparisons between amplitudes estimated between this model and others, we define

where  denotes the best-fitted (i.e. maximum a posteriori) value of each parameter.

denotes the best-fitted (i.e. maximum a posteriori) value of each parameter.

2.4.3. Restricted TATT model (NLA-k)

By design, the angular scale dependence of the NLA model is identical to that of the matter power spectrum projected over the redshift distribution of the sample. A natural way to extend this is to consider next-to-linear alignment effects, specifically: (i) a density weighting (Hirata & Seljak 2004), accounting for the fact that alignments are only measured at local over-densities of the matter distribution where galaxies reside; and (ii) quadratic alignments as expected for tidal torquing effects (Crittenden et al. 2001; Catelan et al. 2001).

These contributions are subsumed into the tidal alignment, tidal torquing (TATT) model (Blazek et al. 2019), each with a free amplitude parameter. As can be seen from Figure 1 of Blazek et al. (2019), the density-weighting and quadratic terms have very similar dependence on physical scale. Owing to the scale-mixing of angular statistics, cosmic shear measurements poorly distinguish small and localised scale differences, which leads to pronounced degeneracies among the four TATT parameters (e.g. Samuroff et al. 2019). To avoid these, we implement the full TATT model within the analysis pipeline, but fix all but one of the free parameters that govern the non-linear terms. We treat this model as a more general modification to NLA, to capture potential deviations in scale from the model. We chose to keep the density weighting amplitude term free, thereby adding a single additional free parameter, but note that this choice is fairly inconsequential: given the aforementioned similarity between the scale dependence of the terms, implementing only the density weighting or only the quadratic term would produce a similar end product. The NLA-k model is then expressed as

where the expressions for A0|0E, C0|0E, and A0E|0E are given in Blazek et al. (2019). We consider these terms in the Limber approximation where only transverse modes contribute, and assume that their redshift evolution is inherited from the linear matter power spectrum. In the original density-weighting term, the free parameter bsrc can be interpreted as an effective galaxy bias of the weak lensing source sample, albeit on fairly non-linear scales. For our model, we chose a top-hat prior in the range [ − 0.5, 1.5] to ensure it encompasses NLA (bsrc = 0) and reasonable values expected for the (unknown) source galaxy bias (bsrc ∼ 1). For comparisons between the alignment amplitude estimated with this model and others, we report the alignment amplitude of the NLA component of the model from Eq. (9), namely,

2.4.4. Galaxy-type and mass-dependent model (NLA-M)

Two trends in IA strength are firmly established observationally: (i) a dichotomy between late- and early-type galaxies where only the latter have yielded significant detections on cosmological scales (Samuroff et al. 2023; Johnston et al. 2019; Heymans et al. 2013; Georgiou et al. 2025; see also Mandelbaum et al. 2011; Tonegawa et al. 2025; McCullough et al. 2024 for additional examples of null or marginal detections of late-type alignments); and (ii) a scaling of early-type alignment amplitude with host halo mass that is well described by a power-law (Joachimi et al. 2011; Fortuna et al. 2025). Both have solid theoretical underpinning. First, rotationally supported late-type galaxies are expected to align through tidal torquing, which depends quadratically on the tidal quadrupole, whereas spheroid shapes should respond linearly and thus be well described by NLA-like models. Second, Piras et al. (2018) motivated the halo mass dependence through an analytical argument and also reproduced it for simulated dark matter haloes.

We incorporated these IA trends explicitly into the amplitude of the NLA model. We assumed that, in each tomographic bin, only the fraction fr of ‘red’ (i.e. early-type) galaxies intrinsically align, whereas the remaining galaxies have zero alignment. The latter assumption is consistent with observations, but within a large statistical uncertainty and involving a substantial extrapolation in sample properties, primarily due to the imperfect relation between galaxy colour and rotational/pressure support (which is the property most-likely to cleanly stratify intrinsic alignment amplitudes). Moreover, we assumed that the red galaxy population IA amplitude has a power-law dependence on the average halo mass ⟨Mh⟩ within a tomographic bin. This leads to

where we adopt the pivot halo mass Mh, piv = 1013.5 h−1 M⊙ from Fortuna et al. (2025). The same authors also fit the power-law dependence to a compilation of early-type IA measurements (see their Figure 4), and we adopt their joint posterior on AIA and β as our prior for cosmic shear inference. Their posterior is well approximated by a bivariate Gaussian with AIA = 5.74 ± 0.29, β = 0.44 ± 0.03, and a correlation coefficient of −0.59. Details on how we determine fr and halo masses for our sample of cosmic shear sources, and how we treat their associated uncertainties, are provided in Appendix B. For comparisons between the alignment amplitude estimated with this model and others, we define

2.5. Cosmic shear summary statistics

In cosmic shear analyses, it is most convenient to measure the signal using shear two-point correlation functions (2PCFs) while the modelling is done through shear power spectra (see Eq. (1)). Alternatively, one could take the Fourier transform of the shear field and work in harmonic space, which brings the measurements closer to the theoretical predictions. We chose to use 2PCFs for the measurement, as they shield us from a particular form of E-/B-mode mixing that occurs in harmonic space in the presence of the (unavoidable) image masks. In addition, the shot-noise term does not impact 2PCFs (present only in their covariance), as it is only relevant at zero lag. In harmonic space, both shot noise and masking must be modelled and corrected, prior to beginning cosmological analyses. For more details see e.g. Alonso et al. (2019).

Our cosmological analysis here leverages two-point statistics: the complete orthogonal sets of E/B-integrals (COSEBIs, Sect. 2.5.2) and band power spectra (Sect. 2.5.3), constructed using linear combinations of finely-binned 2PCFs (Sect. 2.5.1).

2.5.1. 2PCFs (ξ±)

The shear two-point correlation functions (ξ±, Kaiser 1992) are functions of the tangential and cross components of shear (γt and γ×, respectively) defined with respect to the line connecting pairs of galaxies with angular separation θ (see e.g. Bartelmann & Schneider 2001),

The measured 2PCFs are binned in θ to reduce measurement noise and compress the data. In practice, we measure ξ±(θ) for 1000 logarithmically spaced θ-bins between θmin = 2′ and θmax = 300′ using TREECORR1 (Jarvis et al. 2004). The inputs to TREECORR are galaxy catalogues, which include galaxy ellipticities (ε1 and ε2), galaxy positions (right ascension and declination), and galaxy weights (w). The weights used by TREECORR are equal to the recalibrated shape weights (Sect. 3.5) multiplied by the redshift distribution gold-weights (Sect. 3.4). Our ξ±(θ) are then estimated using

where  is the bin selection function (which limits the sums to galaxy pairs of separation within the angular bin labelled by

is the bin selection function (which limits the sums to galaxy pairs of separation within the angular bin labelled by  and the tomographic bins i and j), and

and the tomographic bins i and j), and  and

and  are the projected tangential and radial components of observed ellipticities between pairs of galaxies. The estimator includes the galaxies’ multiplicative shear measurement biases ma estimated via image simulations (Sect. 3.4).

are the projected tangential and radial components of observed ellipticities between pairs of galaxies. The estimator includes the galaxies’ multiplicative shear measurement biases ma estimated via image simulations (Sect. 3.4).

Using the flat-sky approximation, we can relate the 2PCFs to the angular (shear) power spectra by Hankel transformations:

where  are the E/B-mode angular power spectra for redshift bins i and j, and J0/4(x) are the zeroth- and fourth-order Bessel functions of the first kind. We expect cosmic shear to produce only E-mode signals up to first order (Schneider et al. 1998; Hilbert et al. 2009), while data systematic errors can in principle create both E and B modes. As a result, B-modes have long been used as a diagnostic tool in cosmic shear analyses (see e.g. Pen et al. 2002; Hoekstra et al. 2002; Heymans et al. 2005; Kilbinger et al. 2013).

are the E/B-mode angular power spectra for redshift bins i and j, and J0/4(x) are the zeroth- and fourth-order Bessel functions of the first kind. We expect cosmic shear to produce only E-mode signals up to first order (Schneider et al. 1998; Hilbert et al. 2009), while data systematic errors can in principle create both E and B modes. As a result, B-modes have long been used as a diagnostic tool in cosmic shear analyses (see e.g. Pen et al. 2002; Hoekstra et al. 2002; Heymans et al. 2005; Kilbinger et al. 2013).

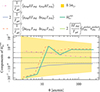

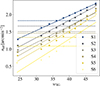

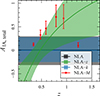

As ξ± mix E and B modes, they are not ideal for cosmic shear analysis. In addition, they variably weight a large range of physical scales in each angular bin, increasing sensitivity to scale-dependent effects such as baryonic feedback (which must be marginalised over using imperfect models). Figure 1 shows the range of ℓ probed by the ξ± over a range of angular separations. The J0 filter in Eq. (15) means that ξ+ mixes a very wide range of scales (1 ≲ ℓ ≲ 104) and J4 makes ξ− particularly sensitive to smaller scales (10 ≲ ℓ ≲ 105). This breadth can create a problem when using ξ± for inference, as the power spectra and intrinsic alignment models become increasingly uncertain at smaller scales. Consequently, we expect the cosmological constraints to be possibly affected by a range of systematic effects that may introduce biases and, as such, we do not include ξ± in our primary cosmological analyses. Nevertheless, results for ξ± are provided for completeness and comparison with previous work, in Appendix F.

|

Fig. 1. Integrands of the transformation between the angular power spectrum and En/Bn (Eq. 17, panel ‘a’), CE, B (Eq. C.5, panel ‘b’), and ξ± (Eq. 15, panels ‘c’ and ‘d’). All solid integrands are normalised by their maximum absolute value. For both COSEBIs and 2PCFs, we show the limiting ranges of the statistics (n ∈ {1, 6} for En and θ ∈ {2.0, 300.0} arcmin for ξ±). For CE, B we show all eight bins used in KiDS-Legacy, defined between ℓ = 100 and ℓ = 1500. Note that, unlike previous KiDS analyses, our new treatment of T(θ) means that the CE, B initially go to zero within their desired ℓ ranges. |

2.5.2. COSEBIs (En/Bn)

The COSEBIs (Schneider et al. 2010) were originally designed to cleanly separate E- and B-modes over a finite θ-range. This was achieved through the use of filter functions T±n(θ), which form complete bases, creating well-defined COSEBIs E- and B-modes (En/Bn). COSEBIs can be calculated or measured via a linear transformation of ξ±,

The COSEBIs modes n start from 1 and go to infinity. However, the first few COSEBIs are sufficient to capture essentially all the cosmological information in each pair of tomographic bins (Asgari et al. 2012). This means that COSEBIs naturally compress the data into well-defined modes, once θmin and θmax are defined, without any need for subsequent data compression. In previous KiDS analyses (e.g. Asgari et al. 2021), the first five COSEBIs modes were used for cosmological analyses. In this work, however, we add the sixth mode, as we found that (with our increased constraining power, and larger redshift baseline) the sixth mode contains relevant cosmological information and thus improves our constraining power on S8. Conversely, the addition of modes 7 − 20 did not result in any improvement of constraining power, returning constraints identical to those measured in the 6 mode case.

We use the relation between COSEBIs and shear power spectra to make our predictions,

where the weight functions Wn(ℓ) are

Figure 1 shows two example integrands from Eq. (17). Wn(ℓ) are highly oscillatory weight functions with a limited range of support over ℓ. This allows us to truncate our integrals in Eq. (17) to a finite range in ℓ, as the En integrand in Eq. (17) is practically zero outside 10 ≲ ℓ ≲ 103.

2.5.3. Band powers (CE, B)

Band power spectra (hereafter ‘band-powers’) refer to binned angular power spectra measured by integrating over ξ±(θ) (Schneider et al. 2002; van Uitert et al. 2016; Joachimi et al. 2021). Ideally, we want a finite number of bins, labelled as l, where each bin is only sensitive to a narrow range of ℓ-values between ℓlo, l and ℓup, l. We also want the E- and B-mode band-powers to be pure, namely, no leakage from B modes into E modes and vice versa. For this ideal case, we can express the following:

for redshift bins i and j, where Sl(ℓ) is the response function for bin l. Here we have normalised the integral with

In this work, we consider the ideal case of a top-hat response function between ℓlo, l and ℓup, l which simplifies the normalisation to

and produces a band-power that traces ℓ2C(ℓ) at the logarithmic centre of the bin. We define eight band-powers logarithmically binned between ℓmin = 100 and ℓmax = 1500. In practice, measuring band-powers with perfect top-hat functions is infeasible, as ξ±(θ) is only measured for a finite θ-range. This has the adverse effect that our band-powers will inevitably mix E and B modes2. The mixing increases for narrower ℓ-bins and when the available range of θ-scales is smaller (Asgari & Schneider 2015). With this definition for band-powers, we forgo perfect E-/B-mode separation in favour of more control over the ℓ-values that contribute to our analyses. We present the detailed derivation of our band-power windows  in Appendix C, and show the integrands of

in Appendix C, and show the integrands of  in Fig. 1. Note, however, that our integrands behave differently to those in Asgari et al. (2021), due to our different treatment of the edges of T(θ) (Appendix C) and due to our different scale-cuts.

in Fig. 1. Note, however, that our integrands behave differently to those in Asgari et al. (2021), due to our different treatment of the edges of T(θ) (Appendix C) and due to our different scale-cuts.

2.6. Analytic covariance modelling

We presented the covariance modelling for KiDS-Legacy and the ONECOVARIANCE code3 in Reischke et al. (2025). In general, the methodology for the cosmic shear part still follows closely the covariance modelling of KiDS-1000 (Joachimi et al. 2021). Major changes to the previous analysis include: (i) the possibility of including non-uniform source distributions in the mixed term of the covariance from the triplet counts of the survey; (ii) including non-binary masks for the area calculation and survey response; and (iii) offering a more generalised framework for a consistent treatment of all summary statistics used in KiDS-Legacy.

The cosmic shear covariance, C, generally consists of four contributions:

with the Gaussian contribution G, the non-Gaussian term NG due to non-linear in-survey modes, the super-sample covariance SSC from modes larger than the survey, and lastly the contribution due to the uncertainty in the multiplicative shear bias calibration, Cmult. Asgari et al. (2021), Secco et al. (2022) included the multiplicative shear bias in the theory prediction instead and marginalised over in the sampling process. If the residual uncertainties on ma are small, these two approaches are equivalent. The Gaussian contribution can further be split into three parts:

describing the sample variance term ‘sva’ due to the finite number of available modes in the survey volume, the pure shot noise term ‘sn’ due to the finite number of sources and their composition, and the mix term ‘mix’.

We calculated the covariances for angular power spectra and transform those to the three summary statistics considered. The only exception was the pure noise term, which was directly computed from the weighted number of pairs in the catalogue. SSC and NG terms were modelled with a halo model approach and the survey variance was directly calculated from the survey mask. Our analytical prescription was tested against GLASS (Tessore et al. 2023) mocks to test the impact of variable depth and the overall agreement. These mocks are discussed in more detail in Appendix D. In Reischke et al. (2025), we showed that the agreement between our analytic covariance and that constructed from GLASS is within 10 percent at large angular separations and below 5 percent for scales below 0.5 degrees. Furthermore, we found that our idealised mix term (which does not account for non-uniformity of the source distribution) did not affect our inference results significantly, and as a result was neglected in our analyses.

3. Data and analysis

In this section, we summarise the KiDS-Legacy lensing data and its calibration, the associated image simulations, and our analysis blinding strategy. Our analysis was performed using a new version of the COSMOPIPE infrastructure presented in Wright et al. (2020). Our fiducial pipeline includes all steps required for a catalogues-to-cosmology analysis, leveraging three primary inputs: a (blinded) shear catalogue (Sect. 3.3), a spectroscopic compilation (Sect. 3.2), and a simulated galaxy lightcone (Sect. 3.4). With these data products, the pipeline performs nine primary functions: pre-processing of the wide-field catalogue, simulated catalogue construction, redshift calibration, N(z) construction, shear calibration, data vector construction, covariance construction, cosmological inference, and post-processing. Details of each processing step are provided alongside the public code base4.

Figure 2 shows the footprint of the KiDS-Legacy sample, split between the two survey patches of KiDS (one in each of the northern and southern Galactic caps). The figure is coloured by the mean effective weight (i.e. including both shape measurement and redshift distribution estimation weights) of sources on sky, which is an approximate tracer of survey properties such as the size of the point-spread function and variable depth (see Appendix D and Yan et al. 2025). The weight is defined as described in Section 7 of Wright et al. (2024), and has the range ![$ w\in[0,\sigma_{\mathrm{pop}}^{-2}] $](/articles/aa/full_html/2025/11/aa54908-25/aa54908-25-eq40.gif) , where σpop = 0.255 is an approximate intrinsic ellipticity dispersion of all sources in KiDS (without e.g. tomographic or brightness selections) defined for Legacy in Li et al. (2023c).

, where σpop = 0.255 is an approximate intrinsic ellipticity dispersion of all sources in KiDS (without e.g. tomographic or brightness selections) defined for Legacy in Li et al. (2023c).

|

Fig. 2. Distribution of the mean weight of the KiDS-Legacy source galaxies in on-sky bins (0.1 × 0.1 degrees). The weights here include both shape measurement weights (Sect. 3.5) and redshift distribution gold weighting (Sect. 3.4). |

3.1. KiDS and VIKING

The KiDS-Legacy lensing sample was drawn from the fifth and final data release of the KiDS survey5, KiDS-DR5, described in Wright et al. (2024). It includes 1347 square-degree tiles observed in the u, g, r, and i filters with the VST (Capaccioli et al. 2005) and OmegaCAM (Kuijken 2011) between 2011 and 2019, as well as the 2009–2018 VIKING survey VISTA/VIRCAM observations (Edge et al. 2013) of the same area in Z, Y, J, H, and Ks. Additionally, the dataset contains spectroscopic calibration fields (the ‘KiDZ’ fields, 27 square-degree tiles in total, including four that are part of the main survey).

KiDS-DR5 significantly extends the previous (fourth) data release (Kuijken et al. 2019), which was the basis for the KiDS-1000 analyses (Asgari et al. 2021; Heymans et al. 2021; Tröster et al. 2021). It represents a substantial increase in survey area (by 34%) and in i-band depth (doubling the exposure time with a second pass). The volume of photometric redshift calibration data has also grown, including photometry for 5 times more spectroscopic sources than in the original KiDS-1000 analysis (Hildebrandt et al. 2021). The deeper i-band depth and more extensive calibration data has allowed us to push the photometric redshift limit for galaxies in the lensing sample from 1.2 to 2. The combined effect of the increase in area and depth is an increase in the survey volume of a factor of 3.5.

Several aspects of the data analysis were changed between DR4 and DR5, as detailed in Wright et al. (2024). The astrometry reference catalogue for the THELI reduction moved from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS Ahumada et al. 2020) and the 2-micron All Sky Survey (2MASS Skrutskie et al. 2006) to Gaia DR2 (Gaia Collaboration 2018), and the astrometric solutions and photometric zero-point determinations in the ASTRO-WISE u-band reductions were made more robust. Also, the manual and automated masking of artefacts in the images, mostly due to ghost reflections, artificial satellite tracks, and detector instabilities, was revisited and improved for the final release. Most importantly, the weak lensing shape measurement method uses an updated version of lensfit (v321), with improvements in the sampling of the ellipticity likelihood surface and of the treatment of residual PSF leakage in the shapes and associated weights (Li et al. 2023c). Details and tests of these new implementations are given in Wright et al. (2024), and in the sections below. A summary of the properties of the KiDS-Legacy sample is given in Table 1, including details of tomographic bin limits, final effective number densities of galaxies (after redshift distribution calibration), and redshift and shape measurement bias parameters.

Properties of the six KiDS-Legacy tomographic bins.

Lastly, we note that a pernicious astrometric issue was identified during the investigation of our B-mode null tests (Sect. 4.3), which resulted in additional masking of approximately 4% of the survey sources to be used in the KiDS-Legacy analysis. More details are given in Sect. 4.3 and Appendix E. The total area after masking is 967.4 deg2, with neff = 8.79 per arcminute within the photometric redshift limits of KiDS-Legacy.

3.2. KiDZ

The KiDZ data consist of VST and VISTA images that target well-studied spectroscopic survey fields, including the Cosmic Evolutions Survey field (COSMOS; Scoville et al. 2007), the DEEP2 Galaxy Redshift Survey (DEEP2; Newman et al. 2013) 02h and 23h fields, the Chandra Deep Field South (CDFS), the Visible Multi-object Spectrograph (VIMOS) Very Large Telescope (VLT) Deep Survey (VVDS; Le Fèvre et al. 2005) 14h field, and the VIMOS Public Extragalactic Redshift Survey (VIPERS; Guzzo et al. 2014) W1 and W4 fields (a full list is given in Wright et al. 2024). They were purposely taken under very similar observing conditions, and with the same observing setup, as the main KiDS/VIKING survey and serve as the calibration sample for photometric redshifts of the faint KiDS sources. A total of 126 085 sources with spectroscopic redshifts have nine-band KiDZ photometry. Additional photometric redshift calibration via cross-correlations uses the overlap between KiDS and shallower, wide-angle spectroscopic redshift surveys, principally: SDSS, the Galaxy And Mass Assembly (Driver et al. 2022) survey, 2-degree Field Lensing Survey (Blake et al. 2016), WiggleZ survey (Blake et al. 2008), and the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI Collaboration 2024).

3.3. Blinding

We used the same blinding methodology as the one implemented in Asgari et al. (2021), first presented in Kuijken et al. (2015). This process involves the double-blind generation of threerealisations of our shape measurement catalogues. One of these is the true catalogue, while in the other two there are induced systematic differences in measured shapes that result in (up to) ±2σ change in the inferred S8. The true catalogue is equally likely to be the one that yields the highest, middle, or lowest S8. These blinded data vectors were analysed throughout the project until the analyses were finalised, cosmological chains were run, the results written up in this publication, and the manuscripts had undergone internal review within the KiDS collaboration. As such, this manuscript (for example) was written containing results for all three blinds, with only the discussion and conclusion sections written afterunblinding.

The authors note (for the reference of future surveys) that this blinding scheme effectively hampered the diagnosis of subtle systematic effects in the dataset (see Appendix E), as we were limited in our ability to directly compare measured shapes between previously constructed catalogues and our KiDS-Legacy catalogues. Such comparisons are extremely useful for the validation of spatially localised systematic patterns in the shape catalogue, which are obfuscated when translated into two-point statistics. This blinding strategy, however, makes such direct comparisons between shape catalogues problematic, as it can also lead to unblinding.

3.4. Redshift distributions and calibration

Redshift distributions (hereafter ‘N(z)’) used in KiDS-Legacy were estimated and calibrated leveraging both colour-based direct calibration using self-organising maps (SOMs Kohonen 1982) and spatial cross-correlations (CC) between tracer spectroscopic samples and the KiDS-Legacy sources. For a detailed description of the N(z) construction and validation process used in this work, we refer to Wright et al. (2025). In brief, the N(z) here differ in their construction (compared to previous work from KiDS) in three main regards: a considerably larger redshift calibration sample from KiDZ (see Sect. 3.2); a new weighting scheme that replaces the binary ‘gold-class’ with a continuous ‘gold-weight’; and through the optional inclusion of weights for spectroscopic objects, such as our so-called ‘prior-volume weighting’. Gold-weights primarily account for noise in the colour-based association between wide-field sources and their calibrating spectra, and are computed by repeating the gold classification N times (where we arbitrarily chose N = 10). Similarly, our prior-volume weighting applies an a priori weighting to the distribution of calibrating spectra as a function of redshift, to reduce bias caused by colour-redshift degeneracies and the complex redshift selection function of our spectroscopiccompilation.

The redshift distribution calibration for KiDS-Legacy made use of two suites of simulations. For the calibration of the SOM redshift distributions (and calibration of source shape measurements, Sect. 3.5), we used the multi-colour SKiLLS simulation of Li et al. (2023c). For additional SOM redshift distribution calibration and cross-correlation redshift distribution calibration, we used the MICE2 simulated lightcone (Fosalba et al. 2015a; Crocce et al. 2015; Fosalba et al. 2015b; Carretero et al. 2015; Hoffmann et al. 2015) adapted to KiDS noise levels and sample selections (van den Busch et al. 2020).

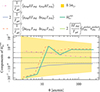

Figure 3 shows the fiducial redshift distributions used in this cosmological analysis. These N(z) include the appropriate δz shifts in each of their mean, as inferred using our simulations and described in Wright et al. (2025). As such, the N(z) presented are shown as-used in the generation of the theory/models during parameter inference. In Wright et al. (2025) we quantified the impact of a series of different analysis choices for N(z) estimation and calibration, demonstrating that they have no significant impact on the final N(z) that we used for cosmological inference. The figure also presents the off-diagonal elements of the correlation matrices for δz, used to construct our correlated δz priors. The lower triangle shows the correlation matrix estimated from our SOM redshift distribution calibration, while the upper triangle shows the correlation matrix for the CC estimated redshift distributions.

|

Fig. 3. Left:N(z) used in the fiducial cosmic shear analyses of KiDS-Legacy. Each panel is one tomographic bin whose definition is determined by the grey band in photo-z. The N(z) have been shifted according to the mean bias estimated using our SKiLLS simulations, making each N(z) a correct representation of the effective N(z) that is used in the cosmological analyses. Fiducial biases are provided in Table 1. Right:δz correlation matrix for our fiducial N(z) (δzSOM, lower triangle) and the correlation matrix inferred from our cross correlation N(z) on the data (DzCC, upper triangle). |

3.5. Shape measurement and calibration

The measurement and calibration of source shapes in KiDS-Legacy were performed with the latest KiDS methods, which have already been established in the literature. We refer to Li et al. (2023c) for an extensive description of the state-of-the-art for shape measurement and calibration in KiDS. Topics discussed therein include: the lensfit algorithm (v321; see also Miller et al. 2007, 2013; Fenech Conti et al. 2017), used for measuring shapes of galaxies (including modelling of the PSF); shape calibration using SKiLLS image simulations; and PSF leakage corrections (with minor updates to the PSF leakage estimation as described in Wright et al. 2024). The SKiLLS image simulations are multi-band image simulations, constructed specifically to match the observational properties of KiDS-Legacy in all available bands, and featuring realistic clustering and correlations between galaxy properties and environment, allowing for realistic treatment of blending effects. The simulations also feature redshift-dependent shear (MacCrann et al. 2022), although this is determined to be of negligible importance to the computation of multiplicative bias (Li et al. 2023c) and redshift distribution bias (Wright et al. 2025) at the sensitivity of KiDS-Legacy.

The multiplicative bias estimation in KiDS-Legacy was performed using the same suite of multi-colour image simulations from SKiLLS used for redshift distribution calibration. Redshift distribution calibration utilises many realisations of the sample to estimate uncertainties on tomographic bias parameters (see Wright et al. 2025). Afterwards, these samples were also used to estimate the multiplicative shear measurement bias, m, per tomographic bin. This means that, for the first time, we have been able to directly estimate the covariance between our redshift distribution bias calibration and our multiplicative shear bias estimation. The resulting covariance matrix (and the corresponding correlation matrix) are functionally block-diagonal: there is no cross covariance between m and δz estimates.

We checked for the degree of PSF leakage measured in the lensing sample through a direct empirical calculation of the correlation between PSF and galaxy ellipticities. Here, we document the measured PSF contamination in our KiDS-Legacy sample, and the measured residual one- and two-dimensional constant ellipticity terms (‘c-terms’) in the dataset. We adopted the first-order systematics model from Heymans et al. (2006):

where k denotes the individual ellipticity components, γ is the (true) shear, and the superscripts ‘obs’, ‘int’, and ‘PSF’ refer to a source’s observed, intrinsic, and modelled PSF ellipticity, respectively. In the limit of large numbers of sources averaged over a large sky area, we can assume ⟨(1 + mk)(εkint + γk)⟩ = 0, and therefore model the residual PSF contamination using a simple linear regression between observed source ellipticities (i.e. after recalibration to remove PSF leakage Li et al. 2023c; Wright et al. 2024) and modelled PSF ellipticities.

Figure 4 shows the αk and ck PSF leakage terms in each ellipticity component of the KiDS-Legacy sample, measured in each tomographic bin. Note that the shape recalibration process used in KiDS-Legacy necessitates that the measured PSF leakage factors be approximately zero, as the recalibration specifically addresses any residual in this parameter, in bins of source signal-to-noise ratio (SN) and resolution (Li et al. 2023c). The residual αk are all negligible, with the α2 having a slightly larger residual amplitude overall (α2 ≈ 0.01, roughly three orders of magnitude smaller than that measured before any recalibration effort). Furthermore, we note that the constant term shown in the figure (ck) is not the same as the additive bias which is removed from our galaxy sample. In practice, the additive component of our ellipticities was computed directly (using a weighted mean) from the sample of galaxies per tomographic bin and hemisphere:  . The

. The  -terms that were subtracted from our recalibrated shape catalogues prior to computation of correlation functions are provided in Table 2. In contrast, the figure presents the constant component of our linear regression (Eq (24)) to all data per tomographic bin after removal of the additive bias. As such it is expected that the ck-terms are small, but not necessarily zero.

-terms that were subtracted from our recalibrated shape catalogues prior to computation of correlation functions are provided in Table 2. In contrast, the figure presents the constant component of our linear regression (Eq (24)) to all data per tomographic bin after removal of the additive bias. As such it is expected that the ck-terms are small, but not necessarily zero.

|

Fig. 4. PSF leakage measured in the KiDS-Legacy lensing sample after recalibration of shapes, computed per tomographic bin and ellipticity component k, and following the first-order systematics model in Eq. (24). |

Subtracted additive shear per ellipticity component, tomographic bin, and hemisphere.

As a further quality test, we computed the non-tomographic 2D c-terms in camera coordinates per ellipticity component, which is shown in Fig. 5. The 2D c-terms were calculated as a weighted mean per bin (using both shape- and gold-weights), with the resulting map smoothed with a Gaussian with one-bin standard deviation (approximately  ), and the computed c-term scaled by the (also smoothed) measured ellipticity dispersion in each bin. The residual c-term can be seen to have amplitudes |ci/σεi|≤1%, indicating that these 2D patterns are negligible in the context of our cosmic shear measurements. The primary structure that is visible in c1 was identified in Hildebrandt et al. (2020) as being due to an electronic effect that introduces an anomalous signal in the read-out direction of one detector on OmegaCAM. However, as shown in Asgari et al. (2021), the amplitude of this signal (≲1% of the ellipticity dispersion) is negligible in the context of our cosmic shear measurements.

), and the computed c-term scaled by the (also smoothed) measured ellipticity dispersion in each bin. The residual c-term can be seen to have amplitudes |ci/σεi|≤1%, indicating that these 2D patterns are negligible in the context of our cosmic shear measurements. The primary structure that is visible in c1 was identified in Hildebrandt et al. (2020) as being due to an electronic effect that introduces an anomalous signal in the read-out direction of one detector on OmegaCAM. However, as shown in Asgari et al. (2021), the amplitude of this signal (≲1% of the ellipticity dispersion) is negligible in the context of our cosmic shear measurements.

|

Fig. 5. Average of each ellipticity component in bins of the focal plane, for sources in all tomographic bins, relative to the (weighted) dispersion of ellipticities in the same bin. The weighted ellipticity dispersion per component over the bins in the focal plane are 0.287 ± 0.001 and 0.288 ± 0.001, indicating that the observed pattern is not driven by variable ellipticity dispersion across the focal plane. The figures still indicate the presence of the two-dimensional pattern reported in Figure 2 of Hildebrandt et al. (2020). |

4. Null tests

In this section, we outline the various null tests that were completed prior to the unblinding of the cosmological analysis of KiDS-Legacy; the reader interested in cosmological parameter estimates only may wish to skip to Section 5. We performed three primary tests: an analysis of the Paulin-Henriksson et al. (2008) systematics model, which quantifies the impact of PSF modelling residuals on correlation functions; an analysis of Bacon et al. (2003) statistics, which test specifically for contamination of the galaxy shape measurements by the PSF; and an analysis of B modes, which tests for a systematic signal that cannot be generated by cosmic shear.

4.1. Paulin-Henriksson et al. (2008) model

To validate the fidelity of our shape measurement catalogue, we first compute the Paulin-Henriksson et al. (2008) systematics model for KiDS-Legacy, which aims to quantify the impact of PSF modelling residuals on cosmic shear correlation functions. This systematics model, in the context of the shear two-point correlation function, reduces to the following:

where we only keep terms that correlate to first order. It should be noted that we use a shorthand notation in Eqs. (25), (26), and (27) as in Section 3.3 of Giblin et al. (2021), so that ⟨ab⟩ denotes ξ±. Here, εobs is the observed ellipticity of a source,  is the noiseless and unbiased measurement of source ellipticity (which we approximate as being equal to the modelled shear:

is the noiseless and unbiased measurement of source ellipticity (which we approximate as being equal to the modelled shear:  ), and T is the R2 object size estimate.

), and T is the R2 object size estimate.

Figure 6 shows the various contributions to the additive systematic,  , from the Paulin-Henriksson et al. (2008) systematics model. The four terms from Eq. (25), shown in various colours, cause ⟨εobsεobs⟩ to deviate from ⟨εperfectεperfect⟩. The total systematic δξ+sys:

, from the Paulin-Henriksson et al. (2008) systematics model. The four terms from Eq. (25), shown in various colours, cause ⟨εobsεobs⟩ to deviate from ⟨εperfectεperfect⟩. The total systematic δξ+sys:

|

Fig. 6. Contributions to the additive systematic |

is given by the summation of these four terms6 and can be compared to the yellow band which encloses 10% of the uncertainty on the cosmic shear correlation function ξ+, from the ONECOVARIANCE (Sect. 2.6). The figure presents the analysis of our sixth tomographic bin (quantitatively similar results are obtained for all other bins), and demonstrates that errors in our PSF modelling are sufficiently small (consistently less than 10% of our correlation function uncertainty) that there is no significant contamination of our two-point statistics from this source of bias. As such, we conclude that PSF modelling errors are negligible for the analysis of cosmic shear in KiDS-Legacy.

4.2. Bacon et al. (2003) statistics

We also used the method from Bacon et al. (2003) to infer the degree of PSF leakage into the two-point correlation function measurement using

In Fig. 7, we show the value of ξ+sys in each tomographic bin autocorrelation, as a fraction of the theory prediction of the cosmic shear signal from our best-fit ξ± cosmology ( ). Results from the cross-correlation bins are quantitatively similar to the autocorrelation. As a reference, we also show 10% of the 1σ uncertainty on the cosmic shear signal as reported by the ONECOVARIANCE (Sect. 2.6). The measured fractional PSF contamination is less than the benchmark 10% of the cosmic shear correlation function uncertainty for all but five data points (out of 189 across all tomographic bin combinations). As such, we conclude that the PSF contamination of cosmic shear correlation functions is negligible in KiDS-Legacy, as expected from our PSF leakage analysis (Sect. 3.5).

). Results from the cross-correlation bins are quantitatively similar to the autocorrelation. As a reference, we also show 10% of the 1σ uncertainty on the cosmic shear signal as reported by the ONECOVARIANCE (Sect. 2.6). The measured fractional PSF contamination is less than the benchmark 10% of the cosmic shear correlation function uncertainty for all but five data points (out of 189 across all tomographic bin combinations). As such, we conclude that the PSF contamination of cosmic shear correlation functions is negligible in KiDS-Legacy, as expected from our PSF leakage analysis (Sect. 3.5).

|

Fig. 7. Ratio of PSF contamination in the cosmic shear correlation function, |

4.3. B modes

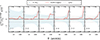

Our third null test examined the significance of B-mode signals in the data vector used for cosmological analyses. This test was based on the understanding that, at the sensitivity available to stage-III cosmological imaging surveys, B-mode signals of cosmological and astrophysical origin ought to be negligible. As such, any significant detection of B modes implies a contamination of the data vector by systematic effects, which may similarly (but undiagnosably) also impact the E-modes used for cosmological inference.

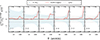

We used a tomographic analysis, equivalent to that of the fiducial cosmological analysis, to derive the significance of B modes (estimated via the COSEBIs Bn) in our data vector. In the early stages of our blinded cosmological analysis, it became clear that our initial KiDS-Legacy sample failed this null test, at high significance. This led to a re-examination of the cosmological sample, which in turn led to a redefinition of the survey footprint to conservatively exclude 46.6 square-degrees with increased astrometric scatter between exposures in our lensing imaging (see Appendix E).

The B-mode signal is presented in Fig. 8. The p-values for the measured B modes across all tomographic bin combinations are 0.04 in the case of 6 Bn modes, and 0.09 in the case of 20 modes, and thus both pass our required threshold of p > 0.01 (adopted from previous work within both the KiDS and DES teams). Looking at the individual tomographic bins, only the sixth bin autocorrelation, with 6 Bn modes, has a p-value below 0.01. However, with 21 tests (one per bin combination) it is expected that one will occasionally find p < 0.01 even with correlated data drawn from the null hypothesis; indeed, this is essentially the calculation that is performed in the computation of the ‘all bins’ p-value, which passes.

|

Fig. 8. COSEBIs B modes measured in KiDS-Legacy. Each panel is annotated with the p-value of the B-mode signals for twenty modes (black) and our fiducial 6 modes (blue). The total p-value for the full data vector, also for six and twenty modes, is annotated in the upper right corner of the figure. The B-mode signals are highly correlated across modes within a tomographic bin, so readers are cautioned against so-called ‘χ-by-eye’. |

5. Results

In this section, we present the cosmological results from KiDS-Legacy split between our fiducial results (Sect. 5.1), and variations of analysis and modelling choices (Sect. 5.2). Furthermore, we refer the reader to our companion paper (Stölzner et al. 2025) for detailed analyses of the internal consistency of KiDS-Legacy, and for analysis of the external consistency between KiDS-Legacy and datasets from DES, DESI, Pantheon+ (Brout et al. 2022), and Planck.

5.1. Fiducial constraints

The fiducial analysis of KiDS-Legacy used two statistics (En, CE) measured over  , an NLA-M intrinsic alignment model, correlated δz prior marginalisation, emulated COSMOPOWERP(k) trained on CAMB and HMCODE2020, covariances constructed with the ONECOVARIANCE and augmented with the uncertainty in the shear calibration, and sampling performed by NAUTILUS (Lange 2023) within COSMOSIS, using a Gaussian likelihood. We chose the NAUTILUS sampler due to its superior efficiency, robustness of uncertainties, and accurate evidence estimation (see e.g. Lemos et al. 2023; Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration 2023). Priors for the various cosmological and nuisance parameters are given in Table 3. Correlated priors used for our redshift distribution bias parameters are given in Sect. 3.4, and for the IA model are given in Appendix B.

, an NLA-M intrinsic alignment model, correlated δz prior marginalisation, emulated COSMOPOWERP(k) trained on CAMB and HMCODE2020, covariances constructed with the ONECOVARIANCE and augmented with the uncertainty in the shear calibration, and sampling performed by NAUTILUS (Lange 2023) within COSMOSIS, using a Gaussian likelihood. We chose the NAUTILUS sampler due to its superior efficiency, robustness of uncertainties, and accurate evidence estimation (see e.g. Lemos et al. 2023; Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration 2023). Priors for the various cosmological and nuisance parameters are given in Table 3. Correlated priors used for our redshift distribution bias parameters are given in Sect. 3.4, and for the IA model are given in Appendix B.

Fiducial prior ranges used in the analysis of KiDS-Legacy.

Constraints on S8 (α = 0.50) and Σ8 (α free).

Figure 9 presents the fiducial marginal constraints in σ8, S8, and Ωm. Marginal constraints over both S8 and Σ8 = σ8(Ωm/0.3)α (with the exponent fitted to the Ωm vs. σ8 contour) are presented in Table 4, for three estimation types: marginal mean and standard deviation, marginal mode and 1D 68% highest posterior density interval (HPDI), and maximum a posteriori (MAP) and 68% projected joint-distribution highest posterior density interval (PJ-HPD). Dark Energy Survey and Kilo-Degree Survey Collaboration (2023, Sect. 2.6) present a discussion of the benefits and detriments of each metric. We also report the χ2 of our cosmological model evaluated at the MAP, and the model probability to exceed (PTE). The MAP was evaluated using an adaptive Nelder-Mead (downhill simplex) algorithm, as described in Joachimi et al. (2021).

|

Fig. 9. Fiducial Ωm, S8 (left), and Ωm, σ8 (right) constraints for our fiducial two-point statistics (En and CE, orange and purple respectively), compared to the CMB results from Planck-Legacy (red). The grey contours outline the marginal distribution of our a priori volume, with (inner) 1σ and (outer) 2σ boundary levels. |

Data vectors for the fiducial En and CE are given in Fig. 10, alongside translated posterior distributions (TPDs; see Köhlinger et al. 2019), for the first application of these consistency metrics to cosmic shear datasets) drawn from the fiducial posterior computed for each statistic.

|

Fig. 10. Data vector and TPDs for the fiducial analysis of En (upper panel) and CE (lower panel). TPDs are shown as polygons spanning the 68th (red), and 95th (orange) percentiles of the posterior models. The En signals are highly correlated across modes within a tomographic bin, so readers are cautioned against so-called ‘χ-by-eye’. The bin 2 autocorrelation signal, for example, is consistent with the best fit model (PTE = 0.09), despite the apparent divergence of the data from the model. The overall PTEs for the full tomographic dataset in each statistic are provided in Table 4. |

Our fiducial cosmological results, from COSEBIs, estimate a value of S8 = 0.813 ± 0.018, evaluated using the marginal mean and standard deviation. This is the tightest constraint made with our COSEBIs measurements, although all constraints are relatively consistent in their constraining power: the marginal mode and HPDI estimate is  , and the maximum a posteriori and PJ-HPD estimate is