| Issue |

A&A

Volume 704, December 2025

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A218 | |

| Number of page(s) | 37 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554786 | |

| Published online | 12 December 2025 | |

Populations of evolved massive binary stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud

I. Predictions from detailed evolution models

1

Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany

2

Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121 Bonn, Germany

3

Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschild-Strasse 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

4

Tel Aviv University, The School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel

5

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

6

Dpto. Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

7

Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Gießenbachstraße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

8

Steward Observatory, Department of Astronomy, University of Arizona, 933 N. Cherry Ave., Tucson, AZ 85721, USA

9

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Krijgslaan 281/S9, 9000 Gent, Belgium

10

Department of Materials and Production, Aalborg University, Fibigerstræde 16, 9220 Aalborg, Denmark

★ Corresponding authors: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

; This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

27

March

2025

Accepted:

7

August

2025

Context. The majority of massive stars are born with a close binary companion. How this affects their evolution and fate is still largely uncertain, especially at low metallicity.

Aims. We derive synthetic populations of massive post-interaction binary products and compare them with corresponding observed populations in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC).

Methods. We analyse 53298 detailed binary evolutionary models computed with MESA. Our models include the physics of rotation, mass and angular momentum transfer, magnetic internal angular momentum transport, and tidal spin-orbit coupling. They cover initial primary masses of 5–100 M⊙, initial mass ratios of 0.3–0.95, and all initial periods for which interaction is expected, 1–3162 d. They are evolved through the first mass transfer and the donor star death, and a a possible ensuing Be X-ray binary phase, and they end when the mass gainer leaves the main sequence.

Results. In our fiducial synthetic population, 8% of the OB stars in the SMC are post-mass-transfer systems, and 7% are merger products. In many of our models, the mass gainers are spun up and expected to form Oe/Be stars. While our model underpredicts the number of Be X-ray binaries in the SMC, it reproduces the main features of their orbital period distribution and the observed number of SMC binary WR stars. We further expect ∼50 OB+BH binaries below and ∼170 above the 20 d orbital period. The long-period OB+BH binaries might produce merging double black holes. However, their progenitors, the predicted long-period WR+OB binaries, are not observed.

Conlcusions. While the comparison with the observed SMC stars supports many physics assumptions in our high-mass binary models, a better match for the large number of observed OBe stars and Be X-ray binaries likely requires a lower merger rate and/or a higher mass transfer efficiency during the first mass transfer. The fate of the initially wide O star binaries remains particularly uncertain.

Key words: stars: black holes / stars: emission-line, Be / stars: neutron / stars: Wolf-Rayet / Magellanic Clouds / X-rays: binaries

© The Authors 2025

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

A new window onto the Universe was opened by the first direct detection of gravitational waves, emitted by the merging of two stellar-mass black holes (BHs; Abbott et al. 2016). Up to now, more than 100 compact object merger events have been detected in this way (Abbott et al. 2023). Several formation channels have been proposed (Belczynski et al. 2016; Mapelli 2020; Mandel & Broekgaarden 2022), including the formation of double compact objects in isolated massive binaries. Due to the cosmological distance of these sources, and considerable delay times between the compact object formation and the merger, many of them will have formed in the low-metallicity environment of the high-redshift Universe (Belczynski et al. 2016; Klencki et al. 2025).

An understanding of the formation of tight double-compact binaries through binary evolution is intimately linked to an understanding of massive stars, since most of them are born with a close companion with which they will interact (Sana et al. 2012). Massive star feedback, be it via emitting newly synthesized chemical elements, kinetic energy, or ionizing radiation, is strongly affected by the presence of a companion (Zapartas et al. 2017; Götberg et al. 2019; Eldridge & Stanway 2022), which is therefore important for the evolution of star-forming galaxies (Ma et al. 2016; Fichtner et al. 2022).

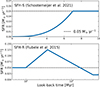

While this holds for all redshifts, we can study metal-rich individual massive stars and binaries in detail. Galaxies are observed at redshifts beyond 14 (Carniani et al. 2024; Helton et al. 2025), and individual stars in these galaxies cannot be resolved. In this respect, the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) provides an ideal laboratory in which to investigate massive single-star and binary evolution at conditions prevalent in the early Universe. Its metallicity of only ∼1/5 the solar one (Hill et al. 1995; Korn et al. 2000; Davies et al. 2015) corresponds to the average metallicity of star-forming galaxies at a redshift of ≈5 (Langer & Norman 2006). Yet, with a distance of only 61.9 ± 0.6 kpc (de Grijs & Bono 2015), and with a current star formation rate of ∼0.05 M⊙ yr−1 (Harris & Zaritsky 2004; Rubele et al. 2015; Hagen et al. 2017; Rubele et al. 2018; Schootemeijer et al. 2021), it shows us a rich population of massive stars.

The SMC is also an ideal test bed for massive star evolution for other reasons. Firstly, due to its low metallicity, the wind loss of hot stars is weak (Mokiem et al. 2007), such that the uncertainty in their mass and angular momentum loss is reduced. Secondly, the extinction towards most of the stars is very low (Górski et al. 2020). Except for potentially the youngest massive stars (Schootemeijer et al. 2021), it is thus generally assumed that we observe their complete populations, which makes the SMC well suited for population synthesis studies. The BLOeM survey will provide further information about the binarity of the SMC massive stars, offering critical tests for binary evolution models (Shenar et al. 2024).

Figure 1 presents a schematic picture of the evolutionary phases of massive close binary systems, up to the time where the initially less massive star leaves the main sequence. It demonstrates that binary evolution models may be compared with the properties of several observed populations of evolved massive binaries in the SMC. While so far, 14 radio pulsars are known in the SMC (Carli et al. 2024) of which 1 has a B star companion, the SMC’s massive X-ray binary population is particularly rich, with about 150 objects, of which ∼100 are identified to be Be X-ray binaries (BeXBs, Haberl & Sturm 2016). Furthermore, Schootemeijer et al. (2022) identified more than 1700 OBe stars brighter than MV ≃ −3 mag (≳9 M⊙), most of which are thought to represent spun-up mass gainers in binary systems (Shao & Li 2014; Bodensteiner et al. 2020). Drout et al. (2023), by searching for UV excess, identified nine hot stars in the SMC with high surface gravities, consistent with the expectation for stars stripped in binaries. The SMC also harbours 12 Wolf-Rayet (WR) stars, four of which show a close OB star companion (Shenar et al. 2016; Neugent et al. 2018).

|

Fig. 1. Schematic evolution of a massive binary system through the six evolutionary phases considered in this paper: pre-interaction, RLO, stripped envelope star (subdwarf, helium star, or Wolf-Rayet star), compact object, referred to as the compact companion (cc) in a binary system, formation possibly connected with a SN explosion, X-ray silent compact object binary, and HMXB. After the second stage, a fraction of the mass gainers may be fast-rotating and appear as Oe or Be stars, and after NS formation as a OBe X-ray binary. Notably, many systems do not survive the second, fourth, and sixth stage as a binary, i.e. the number of systems evolving from top to bottom is being reduced at these stages. The figure is adapted from Kruckow et al. (2018). |

While the predictions of population synthesis models can be compared with these observed samples of post-interaction binaries, for several binary evolutionary stages we basically lack any observed counterparts. This holds in particular for rich predicted populations of stripped mass donors that lack the strong winds to make them appear as WR stars (Wellstein et al. 2001; Götberg et al. 2018; Langer et al. 2020a; Shenar et al. 2020; Drout et al. 2023), for wind accreting BHs with OB star companions (Shao & Li 2019; Langer et al. 2020b; Janssens et al. 2022), which may lack observable X-ray emission (Hirai & Mandel 2021; Sen et al. 2021, 2024), very few of which are known in the Galaxy and Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) (Orosz et al. 2009, 2011; Shenar et al. 2022a; Mahy et al. 2022), and none of which have been found so far in the SMC. Here, population synthesis predictions are useful to refine targeted searches for such objects.

We aim to provide predictions for the evolved phases of massive binary stars in the SMC based on detailed MESA binary evolution models. This work covers all the evolutionary stages presented in Fig. 1. The later stages up to the merger of binary BHs will be investigated in our follow-up work by using the population derived in this work and our detailed model data. Our work is closely related to that of Schürmann et al. (2025; hereafter Paper II), who undertake a similar effort using the rapid binary evolution code ComBinE (Kruckow et al. 2018). Our paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we introduce the grid of detailed binary evolution models used for our analysis, and detail the essential input physics. In Sect. 3, we present the results of our fiducial population synthesis model, and in Sect. 4 we describe the results of parameter variations. In Sect. 5, we compare our results with observations. We discuss the key uncertainties in our calculations in Sect. 6, before summarizing our results in Sect. 7.

2. Method

This work is based on a dense grid of detailed massive binary evolution models (Wang et al. 2020), which was calculated with the one-dimensional stellar evolution code MESA (Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics version 8845) using a tailored metallicity appropriate for the SMC, as in Brott et al. (2011). The detailed description of this code can be found in Paxton et al. (2011, 2013, 2015). Using statistical weights depending on the initial distributions and lifetimes allows us to perform population synthesis.

In contrast to rapid binary population synthesis, where different binary model parameters can easily be explored, we only have one fixed binary evolution grid to work with. However, in order to construct a synthetic population from that model grid, parameters are introduced, which can be varied later on. This concerns in particular the birth kicks of compact objects, the core mass ranges defining the emerging compact object type, the threshold rotation for assuming an OBe nature, and the star formation history. In the following subsections, we describe our method in detail.

2.1. Input physics

Here we briefly summarize our input physics parameters for the MESA calculations. In order to model convection, the standard mixing length theory is adopted with a mixing length parameter of αMLT = 1.5 (Böhm-Vitense 1958). We used the Ledoux criterion to identify convective layers, and adopted step-overshooting for the hydrogen-burning core using a parameter αov = 0.335 (Brott et al. 2011). We modelled semiconvection according to Langer et al. (1983) using a semiconvection efficiency parameter of αsc = 1 (Langer 1991; Brott et al. 2011; Schootemeijer et al. 2019). We follow Cantiello & Langer (2010) in modelling thermohaline mixing with the efficiency parameter αth = 1. Rotation-induced mixing was computed in the diffusion approximation as in Heger & Langer (2000), including the dynamical (Endal & Sofia 1978) and secular shear instability (Maeder 1997), Goldreich-Schubert-Fricke instability (Goldreich & Schubert 1967; Fricke 1968) and Eddington-Sweet circulation (Eddington 1929). In addition, the Spruit-Taylor dynamo was included for the internal angular momentum transport (Spruit 2002).

We adopted stellar wind mass loss following the treatment in Brott et al. (2011), which includes the so-called bi-stability jump (Vink et al. 1999). The first jump is near an effective temperature of 22 kK, below which the mass-loss rate was computed according to Nieuwenhuijzen & de Jager (1990) and Vink et al. (2000, 2001). This mass-loss prescription may need revisions, as recent observations on galactic massive stars do not find evidence for the changes in mass-loss rates across the jump temperature (de Burgos et al. 2024). For enhanced surface helium abundances, with helium mass fractions in the range 0.3–0.7, the mass-loss rate was smoothly increased towards empirical WR rates (Hamann et al. 1995). In addition, enhanced mass loss by rotation was assumed as in Heger & Langer (2000). While rotation does not necessarily enhance mass loss (Hastings et al. 2023), the purpose of this assumption in our models was to prevent the accreting components in mass transfer models from achieving faster-than-critical rotation. Stellar wind also carries away angular momentum, braking stellar rotation. During each time step, our model (MESA ver. 8845) calculated the angular momentum loss by removing the angular momentum contained in the removed layer, which was done the same way as in Brott et al. (2011). Assuming a constant surface specific angular momentum during one time step, which appears to be more physically correct and is done in the most recent MESA versions, would result in a stronger wind induced spin-down than our scheme, and would thus lead to a smaller number of OBe stars (cf. Paper II). However, as (Nathaniel et al. 2025) find that the spin-down of Galactic O stars appears to be better reproduced with the old angular momentum loss prescription, we consider this issue unresolved.

We considered only circular orbits. The orbital evolution of our binary models is affected by mass transfer (Tauris & van den Heuvel 2023) and tides (Hut 1981; Hurley et al. 2002; Sepinsky et al. 2007). We used the Hut_rad scheme coded in MESA to calculate radiative-damping dominated tidal interaction (Detmers et al. 2008), while recently Sciarini et al. (2024) argue that there could be inconsistency in this tide prescription. Mass transfer takes place when the radius of the primary star exceeds the radius of its Roche lobe, where the Roche lobe radius was calculated with the analytic fit derived by Eggleton (1983). In order to account for long-term contact phases, the contact scheme in MESA was adopted (Marchant et al. 2016; Menon et al. 2021). During mass transfer, accretors can be spun up to critical rotation (Packet 1981; Petrovic et al. 2005). The accretor was assumed to accrete as much as possible before reaching critical rotation. When the expected mass transfer rate would cause it to exceed critical rotation, we assumed the accretor can only accrete the amount that makes it remain below critical rotation (Petrovic et al. 2005), which sets a balance among tidal interaction, accretion, and structure adjustment that gives the mass transfer efficiency in a self-consistent way (Paxton et al. 2015). The non-accreted material was assume to be ejected from the binary system, carrying the specific orbital angular momentum of the mass gainer (so-called isotropic re-emission; Soberman et al. 1997). This leads to a rotation-dependent accretion efficiency. In wide-orbit binaries, where tides are inefficient, the accretion efficiency is often below 10%, while it can reach 60% in narrow-orbit binaries.

We setted an upper limit on the mass loss rate from the binary system, Ṁlimit, by comparing the photon luminosity of the stars with the energy input rate that is required to maintain the current mass-loss rate from the binary, as Marchant (2017):

Here, L1 and L2 are the luminosities of the mass donor and the mass gainer, M2 is the mass of mass gainer, and RL, 2 is the Roche-lobe radius of the mass gainer, at which material is assumed to be ejected. If a larger mass-loss rate from the binary system is required, we assumed that the mass transfer is unstable and produces a binary merger. With the above condition, the critical mass ratio for unstable mass transfer in our models is sensitive to the initial orbital period and the initial primary mass of the system (see Sect. 2.2 and Fig. 2). The merger rate based on Eq. (1) is a lower limit, as the ejection of the same amount of material at other locations, like the surface of the mass gainer or the accretion disc around the mass gainer, would require higher radiation energies, resulting in a lower threshold for the mass-loss rate from the system. In addition, we also assumed unstable mass transfer if the mass transfer rate exceeds 0.1 M⊙ yr−1, if inverse mass transfer occurs with a post-main-sequence (post-MS) donor, or if the second Lagrangian point (L2) overflow occurs during a contact phase. The survivors of unstable mass transfer were ignored, as their initial parameter space is narrow (e.g. Ercolino et al. 2024) and expected to take a small fraction of the population considered in this work.

|

Fig. 2. Outcome of the first mass transfer phase in our detailed binary evolution models with an initial primary mass of 17.8 M⊙. In this figure, each pixel represents one detailed MESA binary evolution model, and the corresponding evolutionary outcome is colour-coded (see top legend). Here, ‘OB+cc’ (cc= BH, NS, WD) implies that the corresponding model produced an OB+cc phase, with the cc type indicated by the corresponding colour. However, depending on the adopted compact object birth kicks, these systems may also break up. Systems indicated as ‘Upper_mdot_limit’ or ‘MT_max’ are terminated during their first mass transfer phase as the mass transfer rate exceeds limiting values (see text) and a merger is expected, and those indicated as ‘other merger’ undergo L2-overflow in a contact situation. Corresponding plots for different initial donor star masses can be found in Appendix A. |

Our binary models were evolved from the zero-age main-sequence (ZAMS) stage up to core carbon depletion of the primary star, except for donor stars with a helium core mass above 13 M⊙, for which we terminated the evolution at core helium depletion for numerical reasons. After the termination of the primary star, we further evolved the secondary star as a single star. This numerical setting allows one to explore various post-supernova (post-SN) scenarios (cf. Sects. 2.5 and 2.6).

2.2. Binary model grid

Our SMC binary model grid (Wang et al. 2020) contains 53298 detailed evolution models. The model data1 and necessary files2 to reproduce our models are available online. We assumed that the stars are initially tidally locked. Therefore, the initial binary parameters are the initial primary mass, M1, i, initial mass ratio, qi, and initial orbital period, Porb, i. Our model grid was computed with the following parameter space:

-

Initial primary masses, M1, i, were set in the range of 5–100 M⊙, or log (M1, i/M⊙) between 0.7 and 2, with constant intervals of Δ log(M1, i/M⊙) = 0.05;

-

Initial mass ratios, qi, were considered between 0.3 and 0.95 with a constant interval of Δ qi = 0.05;

-

Initial orbital periods, Porb, i, were selected from 1 d to 3162 d, or log(Porb, i/day) = 0.0–3.50, with constant intervals of Δ log (Porb, i/day) = 0.025.

The input parameter space covers all initial primary masses of BH and neutron star (NS) progenitors below 100 M⊙ and all initial orbital periods for interacting systems. The lower limit on the initial mass ratio was chosen to be 0.3, below which we expect mass transfer to be unstable (Soberman et al. 1997). While recent studies (Ge et al. 2020; Marchant et al. 2021; Schürmann & Langer 2024) find that stable mass transfer is possible for qi < 0.3 in the long-period regime, the corresponding parameter space is small and can be neglected for the purpose of this study.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the models, and the outcome of the first mass transfer phase, for all models with an initial primary mass of M1, i = 17.8 M⊙ (see Appendix A for other initial primary masses). According to the definition of Kippenhahn & Weigert (1967), our closest binaries undergo Case A mass transfer, where the primary star fills its Roche lobe during its core hydrogen burning phase. Above an initial orbital period of ∼5 d, the mass transfer takes place with a shell hydrogen burning donor (Case B mass transfer). At this initial primary mass, our Case A mass donors form NSs, and our Case B mass donors form BHs, according to our adopted maximum final He-core mass limit of 6.6 M⊙ for NS formation (cf. Sect. 2.5). For initial orbital periods above ∼300 d, the mass transfer rate violates our upper limit of 0.1 M⊙ yr−1. Here, mass transfer was expected to become unstable due to the convective envelope of the donor star (Soberman et al. 1997). The widest binaries do not experience any binary interactions and serve as a grid of single star models.

Based on our stability criterion from Eq. (1), we find that a large fraction of models undergo unstable mass transfer (labelled by ‘Upper_mdot_limit’ in Fig. 2). For higher initial primary masses, fewer binary models experience unstable mass transfer (cf. Figs. 2, A.1, and A.2). Also, the Case A/B boundary is shifted to larger initial orbital periods, even exceeding 1000 d for the highest initial primary mass, due to envelope inflation near the Eddington limit (Sanyal et al. 2015, 2017; Sen et al. 2023).

If unstable mass transfer occurs during a Case A mass transfer, the merger product is expected to be a MS star, and we followed its evolution by using the merger models at the SMC metallicity computed by Wang et al. (2022). In these models, the mass of the merger product, Mmerger, was determined by (Glebbeek et al. 2013)

where M1 and M2 are the masses of the primary and secondary stars at the time of the merger, and q = M2/M1. The ejected mass during merger is below 7.5% (q = 1) of the mass of the pre-merger system. This equation is based on a head-on collision, and less mass ejection can be expected for a gentler merger process (Schneider et al. 2016). The ejected material was assumed to be envelope material, which has the initial composition of the two stars.

The angular momentum content of merger stars is uncertain. While the available orbital angular momentum exceeds the possible angular momentum content of the merger product, angular momentum can be lost efficiently along with the ejected fraction of the total mass. Schneider et al. (2019) find, in detailed 3D MHD and 1D stellar simulations, that the product of a merger between two massive main-sequence (MS) stars is in fact slowly rotating due to angular momentum loss and thermal relaxation. We therefore assumed the same for our merger products, which implies in particular that they do not contribute to the predicted population of OBe stars.

2.3. OBe stars

The Be phenomenon is produced by rapidly rotating massive MS stars that show the Hα line in emission, and that have an spectral energy distribution showing an infrared excess. Both features are thought to originate from a circumstellar decretion disc that is fed from the layers near the stellar equator (Reig 2011; Rivinius et al. 2013). While Be stars are fast rotators, it is unclear how close they are to their critical rotation. Townsend et al. (2004) suggested that considering gravity darkening, all Be stars spin near their critical rotation. However, the concept of critical rotation is difficult to define (Hastings et al. 2023), and observations seem to imply that some Be stars can rotate sub-critically, with rotational velocities as low as ∼60% of the critical value (e.g. Huang et al. 2010; Zorec et al. 2016; El-Badry et al. 2022; Dufton et al. 2022).

In our fiducial model, we defined Be stars as rotating faster than 0.95 of their critical rotational velocities (υcrit). Golden-Marx et al. (2016) showed that Oe stars are the high-mass extension of Be stars, and therefore we adopted the same threshold value to define Oe stars. Since our spun-up accretors generally reach critical rotation, and keep it up during their further MS evolution (e.g. Hastings et al. 2020), the threshold value only affects the massive accretors that may slowly spin down due to their stellar wind (above ∼40 M⊙; Langer 1998). We quantify the effect of different threshold values in Sec. 4. We did not consider the detailed properties of the circumstellar discs (cf. Rubio et al. 2025).

2.4. Helium stars and Wolf-Rayet stars

Following the common nomenclature, we defined helium stars (He-stars) as stripped-envelope core helium burning stars (Shenar et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2021), whose winds remain optically thin, such that they will not show emission lines in their spectra. Conversely, we spoke of our model corresponding to a WR star when we can assume that it forms an optically thick stellar wind. Shenar et al. (2020) find a metallicity-dependent luminosity threshold for the WR phenomenon, as log L/L⊙ ≈ 4.9, 5.25, and 5.6 for the Galaxy, the LMC, and the SMC, respectively. Aguilera-Dena et al. (2022) and Sen et al. (2023) show that these luminosity limits are roughly reproduced by simple wind models, using the mass-loss rates as adopted here. Accordingly, we assumed that our stripped stars with log L/L⊙ > 5.6 correspond to WR stars. This limit is exceeded by He-stars above ∼15 M⊙, which requires initial masses above ∼40 M⊙. In addition, we defined hydrogen-free (H-free) WR stars by a surface hydrogen mass fraction of less than 0.05, according to the typical uncertainties of the observationally derived hydrogen abundances in Shenar et al. (2016).

2.5. Formation of compact objects

We adopted the types of compact objects formed by our donor stars according to their final model properties. Sukhbold et al. (2018) perform detailed simulations on the explodability of stars. They find a sudden increase in the compactness parameter of pre-supernova (pre-SN) stars at a final He core mass of 6.6 M⊙, which marks the formation of BHs. While stellar winds at different metallicities could alter the evolution of He stars (e.g. Wang & Han 2010; Doherty et al. 2015; Aguilera-Dena et al. 2022; Guo et al. 2024), the relation between the compactness parameter and the final He core mass is insensitive to metallicity (Sukhbold et al. 2016). Accordingly, we assumed that a BH forms if the final mass of a helium core MHe, c reaches 6.6 M⊙. For simplicity, the non-monotonous behaviour of the compactness parameter (O’Connor & Ott 2011; Sukhbold et al. 2016, 2018; Schneider et al. 2023; Aguilera-Dena et al. 2023) was ignored, and this assumption may overestimate the number of low-mass BHs. Different assumptions on mixing process can affect the explodability of stars by changing the final core carbon abundance (Patton & Sukhbold 2020; Schneider et al. 2021), resulting in different values of the mass threshold. This can affect the predicted number of low-mass BH but has a small effect otherwise (Janssens et al. 2022). The mass of the BH was computed by using the same assumption as in the ComBinE code (Kruckow et al. 2018, and Paper II), which is that 20% of the mass of the He-rich envelope of the core He depleted star is ejected, and after that 20% of the remaining mass is lost due to the release of gravitational binding energy.

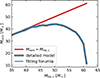

Stars with very massive helium cores become unstable due to the production of electron–positron pairs. Those not massive enough to form a pair-production SN (Heger & Woosley 2002; Langer et al. 2007) undergo a series of energetic pulses accompanied by strong mass ejections (Heger & Woosley 2002; Chatzopoulos & Wheeler 2012; Woosley 2017; Marchant et al. 2019). This process is known as pulsational pair-instability (PPI). Marchant et al. (2019) simulate these mass ejections during the PPI with the MESA code. Base on their result, we performed a polynomial fitting to the helium core mass at core helium depletion and the remaining mass, Mrem, after the pulsations, which is3

where Mrem and MHe,c are in the unit of solar mass. Figure 3 provides a comparison between our fitting formula and the model data in Marchant et al. (2019). This formula is only valid for 35.3 M⊙ ≤ MHe, c ≤ 61.1 M⊙. This mass range is somewhat sensitive to key nuclear reaction rates (Takahashi 2018; Farmer et al. 2020), for which current best estimates lead to a slightly higher mass range (e.g. Farag et al. 2022).

|

Fig. 3. Remaining mass, Mrem, after the pulsations triggered by pair instability, as a function of the helium core mass, MHe, c, at core helium depletion. The grey and blue lines correspond to the model data in Marchant et al. (2019) and Eq. (3), respectively. The red line shows the relation Mrem = MHe, c. |

We assumed that stars with final helium core masses below 6.6 M⊙ form NSs or, for stars with final carbon core masses below 1.37 M⊙ form WDs. The masses of our NSs were fixed to be 1.4 M⊙. Neutron star formation is accompanied by a SN explosion due to the collapsing core. Core collapse in the lowest-mass SN progenitors may be triggered by electron captures, producing a so-called electron-capture SN (ECSNe, Nomoto 1984; Tauris et al. 2015). Since the low-mass progenitors are expected to produce a weak momentum kick on the newborn NSs (Janka 2012), they play an important role in the formation of BeXBs (Podsiadlowski et al. 2004). However, our model grid cannot resolve the narrow mass range of ECSNe well (see Sect. B). For consistency with the results obtained with the ComBinE code (Paper II), we applied the SN scheme adopted in Kruckow et al. (2018) (see Appendix B for details). This considers four types of SNe:

-

Ordinary iron core collapse SNe (CCSNe), if the pre-SN star has a final carbon core mass larger than 1.435 M⊙ and a H-rich envelope;

-

H-envelope-stripped iron-core collapse SNe (CCSN-He) if the H-rich envelope has been stripped by mass transfer;

-

He-envelope-stripped iron-core collapse SNe (CCSN-C) if most of the He-rich envelope has been stripped by mass transfer;

-

ECSNe if the final carbon core mass is in the range 1.37 - 1.435 M⊙.

Different types of SNe are associated with different kick velocity distributions, which are introduced in the next subsection.

2.6. Natal kick

During the SN explosion, asymmetries in the neutrino emission or in the SN ejecta can generate a momentum kick in the new born NSs. Empirical constraints on the kick velocities is still debated (see the discussion in Valli et al. 2025), making this one of the major uncertainties for the formation of NS binaries. The eccentricity of high-mass X-ray binaries (HMXBs; Pfahl et al. 2002) and double pulsar binaries (Tauris et al. 2017; Vigna-Gómez et al. 2018) imply that stripped SNe produce weak momentum kick. Hobbs et al. (2005) found the spatial velocity of young pulsars can be described by the Maxwellian distribution with σ = 265 km s−1. With a sample of 28 young pulsars having VLBI measurements, Verbunt et al. (2017) suggest that there is a slow-moving group of young pulsars (also see Igoshev 2020). Recently, Fortin et al. (2022) and O’Doherty et al. (2023) argue that the kick velocities derived from isolated pulsars overestimate the intrinsic NS kick velocities, since the isolated ones biased towards strong kicks that unbind the binary. The authors find much lower kick velocities by using NS low-mass X-ray binaries.

The more energetic the explosion, the stronger the expected kick (Janka 2012). We used a Monte Carlo method to account for these dynamical effects of SNe. For each pre-SN binary, we determined the type of SN with the SN scheme explained above. Then we randomly drew a sample of kick velocities from the corresponding kick velocity distribution with random orientations. Here we adopted the same kick distributions as ComBinE, which are summarized in Table 1.

Birth kick velocity distributions for NSs used in our synthetic populations.

For normal CCSNe, the kick velocity, υK, distribution was assumed to be a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, f(υK, σ), with a root-mean-square velocity of σ = 265 km s−1, which is based on the proper motion analysis of young pulsar (Hobbs et al. 2005), where

The SNe from stripped stars are thought to be less energetic and therefore to generate weaker kicks (cf. Tauris et al. 2015). On the other hand, the observed double NS binaries imply that rather large kicks may also happen in close binaries (Tauris et al. 2017, and references therein). Accordingly, for stripped SNe we adopted a bi-modal Maxwellian distribution, f2(υK, σ1, σ2), with a 80% low-kick component and a 20% high-kick component,

Based on the observed migration of Galactic HMXBs (Coleiro & Chaty 2013), the low-kick component, σ1, was taken to be 120 km s−1 and 60 km s−1 for CCSN-He and CCSN-C, respectively, and the high-kick component, σ2, was taken to be 200 km s−1(Tauris et al. 2017). For ECSNe, based on the observed low-eccentricity of X Persei-type X-ray binaries (Pfahl et al. 2002; Podsiadlowski et al. 2004), a flat distribution in the range of [0, 50] km s−1 was adopted.

The momentum kick imparted on BHs is highly uncertain. It has been proposed that the low-mass BHs can obtain a natal kick due to fallback during the BH formation (e.g. Belczynski et al. 2008; Fryer et al. 2012; Janka 2017). Mirabel (2017) and Mandel & Müller (2020) provided evidence that the BHs of ∼10 M⊙ and ∼21 M⊙ in the high-mass BH binaries GRS 1915+105 and Cygnus X-1 formed with essentially no kick. Shenar et al. (2022a) and Vigna-Gómez et al. (2024) find that the near-circular X-ray quiet BH binary VFTS 243 in the LMC was born with a negligible kick. However, some BHs in LMXBs may be born with strong kicks (Repetto & Nelemans 2015). Recent evidence for and against kicks in the formation of BHs in LMXBs is discussed in Nagarajan & El-Badry (2025). For simplicity, we assumed no BH formation kick in our fiducial population synthesis model. We investigate the effect of this assumption in Sect. 4.

Besides the kinetic energy injected by a natal kick, mass loss during the SN weakens the gravitational binding of a binary (Blaauw 1961). Whether a binary remains bound after a SN depends on whether the orbital energy of the post-SN system is negative. When a model binary remained bound, we calculated the parameters of the post-SN orbit using the formulae given in Appendix A.1 of Hurley et al. (2002), which are based on Hills (1983). The velocity of the centre of mass generated by the SN explosion is not considered in this work. If a binary got disrupted, we counted the MS companion as a runaway star regardless of its space velocity.

2.7. Population synthesis

In contrast to the commonly adopted Monte Carlo method, we performed population synthesis based on a grid approach. This is suitable as the number of dimensions that our grid span is not very large (M1,i, qi, and log Porb,i) and ensures a uniform coverage allowing us to capture the full variation in behaviour. We assumed an initial binary fraction of 100%. We then assigned a statistical weight to each binary model in a given cell of our initial parameter space that was in a specified evolutionary stage, given by the birth probability and the lifetime of the considered stage (see Appendix E for detailed equations).

The birth probability was determined by the adopted star formation rate, the initial mass function (IMF, fIMF), and the initial distribution of mass ratios, fqi, and orbital periods, flog Porb,i, while the lifetime was given by the evolutionary model in the considered grid cell. For an OB+cc binary, we determined its lifetime by the time between the compact object formation and the secondary star leaving the main sequence or filling its Roche lobe. We adopted the IMF derived by Kroupa (2001),

where

For our fiducial model, initial distributions of mass ratio and orbital period were taken from Sana et al. (2012), which was derived from the O star population in open star clusters. It shows a preference for short orbital periods and a near flat mass ratio distribution,

and

In addition, a constant star formation rate of 0.05 M⊙ yr−1 was adopted (Harris & Zaritsky 2004; Rubele et al. 2015; Hagen et al. 2017; Rubele et al. 2018; Schootemeijer et al. 2021) in our fiducial model. We explore different star formation histories in Sect. 4.

During the OB+cc phase, the orbits may slowly expand or shrink due to the stellar wind from the MS companions (Quast et al. 2019; El Mellah et al. 2020). Considering the low mass-loss rate of OB stars in the SMC, we do not expect significant changes in orbital separation during OB+cc phase. Therefore, we simply assumed the orbital parameters remain unchanged. Also the stellar parameters were assumed to remain constant during this phase. For stellar rotation, we considered the tidal interaction during the OB+cc phase by calculating the synchronization timescale at the beginning of the OB+cc phase. We found that tides during the OB+cc phase are too weak to further spin down the OB star (see Appendix F for details).

For He-stars, we determined their parameters at the middle of core helium burning, which we defined as the moment when when the core He mass fraction dropped to 0.5, and the lifetime was determined by their core He burning time. For WR stars, we went through the evolutionary tracks of core He burning phase step by step to check whether the stars are luminous enough to be considered as WR stars.

We counted pre-interaction MS binaries by going through the evolutionary tracks of all double MS stars in our binary model grid. Only the primary stars were counted, since they are visually brighter than the secondary stars in pre-interaction systems. We defined O stars as MS stars with effective temperatures hotter than 31.6 kK (log Teff /K > 4.5). Here we adopted the relation between spectral type and temperature derived by Schootemeijer et al. (2021). This work does not investigate interacting binaries (see Sen et al. 2022, for a detailed study on massive Algol systems)

3. Properties of our fiducial synthetic population

In this section we present the main properties of our synthetic population based on our fiducial parameter choice, as explained above (see Appendix G for further model details). In Sect. 4, we discuss the effects of variations in the birth kicks of compact objects, the core mass ranges defining the emerging compact object type, the threshold rotation for assuming an OBe nature, and the star formation history. We compare our predictions with the observed numbers in Sect. 5 and discuss the implication for mass transfer physics in Sect. 6.

3.1. The number of O stars

Our adopted star formation rate of 0.05 M⊙ yr−1 determines the absolute number of predicted stars of any type. Our fiducial population contains 1070 O stars, which are defined as the MS stars with Teff > 31.6 kK. This number is slightly larger than the estimated number of observed O stars in the SMC, which is consistent enough for the purposes of this study. For example, in the BLOeM survey of the SMC, Shenar et al. (2024) identify 159 O stars, with a completeness of about 35%. While the survey covers less than half of the surface of the SMC, it focuses on the regions rich in massive stars. Considering the effect of crowding, the BLOeM estimates lead to a total number of about 500 O stars in the SMC.

A similar overprediction has already been noticed by Schootemeijer et al. (2021), who also obtain a total number of O stars in the SMC of just above 1000 with the same SFR and IMF as our fiducial model. However, the authors find that young O stars appear to be missing in the SMC by analysing the Gaia DR2 catalogue (Brown et al. 2018) and on the spectral type catalogue of Bonanos et al. (2010) (see also Castro et al. 2018, which is based on the RIOTS survey Lamb et al. 2016). This means that deep embedding may hide the youngest O stars from our view. Alternately, a star formation history with no star formation at the present time can explain this missing, but it fails to reproduce the observed number of the SMC WR star binaries (see Sect. 4).

3.2. Compact object binaries amongst main-sequence stars

To predict the fraction of massive MS stars expected to be in a binary with a compact object, we first determined the predicted number of OB+cc binaries. We further considered the MS stars with lower-mass MS companions, with helium star companions, and those without companions, whereby the latter are MS mergers and runaways from disrupted systems.

Figure 4 presents the distribution of the MS stars of our OB+NS/BH binaries in the HR-diagram (left panel for NS companions, and right panel for BH companions). The MS components of our OB+NS systems are located between the single-star tracks of ∼6 M⊙ and ∼32 M⊙. The lower mass is set by the smallest initial mass ratio ( 0.65) in the stable mass transferring binaries with the lowest initial primary mass to provide NSs (∼9 M⊙), as can be seen from the overview diagrams in Fig. A.1. The highest mass primaries to provide NSs in our grid are about 20 M⊙ stars in Case A binaries (Fig. A.1). Those are short period systems that, especially for high initial mass ratios, evolve with mass transfer efficiencies of up to 60%, such that the mass gainers can grow up to ∼30 M⊙. The peak of the mass distribution of the MS stars in NS-binaries is at about 9 M⊙. Essentially all OB companions in our NS binary models are somewhat evolved. Hence they are not close to the ZAMS. The reason is that the NS-forming binaries all have initial mass ratios larger than ∼0.5, with an average of about 0.8, which means that the MS lifetimes of the mass gainer and mass donor are comparable. Consequently, when the mass donor produces a NS, the mass gainer has burnt a significant amount of its core hydrogen.

|

Fig. 4. Predicted distribution of OB stars with a NS (left panel) and BH (right panel) companion in the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. The green line is the ZAMS, and the black line is the terminal-age main sequence (TAMS). The blue lines represent evolutionary tracks of non-rotating core hydrogen burning single stars, with the indicated initial masses. The dashed red lines show the boundaries of the three groups of stars defined in the main text, i.e. Teff = 31.6 kK, log L/L⊙ = 5, and the MS evolutionary track of a 8.9 M⊙ single star. On top, we label several spectral types at their approximate effective temperature. |

As we discuss in more detail below, the majority of the MS components below ∼15 M⊙ are expected to rotate close to critical rotation and display themselves as OBe stars. The remaining ones are also expected to rotate rapidly. As most NS-forming binaries break up due to the NS birth kick (see below), we expect many more Be stars to not have a NS companion than to be part of a NS binary.

The highest mass of a MS companion to a WD produced in our grid is ∼12 M⊙ (Fig. 6). As we do not expect newborn WDs to receive kicks like NSs, all WDs are predicted to remain in binary systems, mostly associated with fast-rotating companions, some of which may be observed as WD BeXBs (e.g. Gaudin et al. 2024; Marino et al. 2025). Since our model grid is highly incomplete for WD binaries, their detailed analysis is beyond our scope, and we focus on NS/BH-forming systems.

Since our model predicts more mergers for less massive systems, we expect more BH than NS binaries in the SMC, as is shown in the right panel of Fig. 4. We find that the MS companions of BHs are stretching over a wider mass and and temperature range. While BHs are only formed from primaries above ∼18 M⊙, our BH forming binaries can have stable mass transfer for initial mass ratios as low as 0.3 (Fig. A.1). Due to the different accretion efficiencies of Case A/B binaries (≲10% for Case B and up to ∼60% for Case A), we find the lowest mass MS companions (6 M⊙) to BHs in our models formed in Case B systems but the most massive ones (near 100 M⊙) formed in Case A systems (Fig. G.5). The difference in accretion efficiencies also leads to a stronger surface abundance enrichment for the mass gainers in Case A systems (Fig. G.8).

Towards higher masses, our results become incomplete, but pair-instability will also reduce the number of BH binaries produced there (our most massive BHs are ∼38 M⊙; see below). As the our most massive MS star models undergo envelope inflation, we expect some early B supergiants companions to BHs (cf. Quast et al. 2019). The peak of the MS companion mass distribution is near 10 M⊙, close to that of the NS companions. Most of the BH companions are expected to rotate very rapidly.

To obtain absolute numbers, we integrated the number densities for three groups of stars, mainly depending on the location of the MS component, or of the more massive star in the case of pre-interaction binaries, in the HR diagram as follows (see Fig. 4 for the group borderlines).

-

Group 1: MS stars with masses above 9 M⊙ and luminosities below 105 L⊙;

-

Group 2: MS stars with luminosities above 105 L⊙ and effective temperatures above 31.6 kK;

-

Group 3: MS stars with luminosities above 105 L⊙ and effective temperatures below 31.6 kK.

The chosen boundaries are motivated as follows. The lowest initial primary mass in our binary model grid is 5 M⊙. The most massive merger product involving 5 M⊙ primaries occur in systems with an initial mass ratio of 0.95, and produce 9.02 M⊙ merger products according to Eq. (2). We therefore chose a lower mass limit of 9 M⊙ to ensure completeness of the merger products and mass gainers. Furthermore, the lowest initial primary mass for forming BHs in our Case B system is 17.8 M⊙ (Fig. 2), whose luminosity at terminal-age main sequence is about 105 L⊙. Finally, we chose an effective temperature of 31.6 kK do distinguish between O type and B type MS stars.

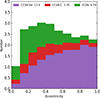

The predicted numbers and fractions of the pre- and post-interaction OB stars are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 5, respectively. To obtain the proper fractions, we include the OB stars produced by the post-interaction single star channels, which are merger products and runaway stars.

Predicted numbers of the pre- and post-interaction MS OB stars in our fiducial synthetic SMC population.

|

Fig. 5. Pie charts for the predicted numbers of pre-interaction MS OB stars primaries, and of OB stars in different types of post-interaction binaries, divided into three groups, Group 1 (top left; top right provides a zoom-in), Group 2 (lower left), and Group 3 (lower right), based on luminosities and effective temperatures. The considered types of binary stars and the corresponding fractions with respect to the total number within the considered group are indicated by text. The corresponding absolute numbers in each wedges are listed in Table 2. |

In Group 1 we find 742 O type and 2398 B type stars, of which 2746 (87.5%) reside in pre-interaction binaries, 155 (4.9%) are merger products, and 42.6 (1.4%) are runaway stars. The remaining ∼200 OB stars have evolved companions.

Group 1 contains 13.6 OB stars with NS companions, most of them B type stars, which implies that only 0.4% of the stars in this group would have a NS companion. At the same time, we expect 4.9% of the MS stars in Group 1 to orbit a BH companion, which is 149 OB+BH binaries in Group 1, 131 of them with a B star. The vast majority of them is expected to be X-ray silent (cf. Sen et al. 2024).

Group 1 is further expected to contain 30.7 OB+He-star binaries, with none of them expected to produce dense enough winds to appear as WR star. However, their winds may collide with the OBe disc or with the wind of their companion, which may turn them into observable X-ray sources (Langer et al. 2020a). We further find 3 WD binaries in Group 1, representing the high mass end of the WD companion mass distribution.

The high-mass Groups 2 and 3 contain 329 O-type stars and 65.5 B supergiants, respectively, which corresponds to 9.3% and 1.8% of all considered OB stars, which means that Group 1 contains 88.9% of them. By design, Groups 2 and 3 contain essentially no NS binaries or runaway stars. However, the most massive BHs and the WR binaries will be found in these groups. With about 10%, the fraction of OB stars with evolved companions is almost twice that in Group 1, with 21.4 (6.5%) and 3.97 (6.1%) of the MS stars forming O+BH and B+BH binaries in Groups 2 and 3, respectively. Also the MS merger fraction in Group 3 is very high with 27.6%.

These numbers are determined by several factors. The fraction of MS merger products goes up with mass due to the growth of the parameter space of Case A mergers (Appendix A). The general decreasing of merger fraction for higher primary masses leads to the increasing of the expected number of post-interaction binaries. This is also relevant for the lower number of NS star binaries compared to BH binaries, which is aggravated by the adopted NS birth kicks, and the neglect of BH kicks. Of course, a different lower mass limit or criterion for BH formation will also shift the relative numbers. The fraction of OB+He-star binaries is at just 10–20% of the OB+cc binaries, because their lifetimes are determined by their core He burning time, while the lifetimes of the former is fixed by the remaining lifetime of the OB star after the formation of the compact object, which is a fair fraction of their MS lifetime.

3.3. Number of post-interaction binaries

While the prediction of MS mergers from our grid is incomplete below ∼9 M⊙ (see above), our choice of the lowest initial primary mass of 5 M⊙ guarantees completeness for the expected NS and BH binaries. In the previous subsection, we used the 9 M⊙ limit for a meaningful comparison of the number of evolved binaries with that of MS stars. Here, we used our complete grid down to primary masses of 5 M⊙, in order to derive absolute numbers of expected post-interaction binaries in the SMC, as well as their mass dependence.

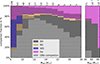

The numbers of the various types of binary systems consisting of a MS star (the mass gainer) and a post-MS companion predicted to exist in the SMC are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 6. In Table 3, we distinguish core-helium burning stripped mass donors originating from three different initial donor mass ranges, which roughly correspond to those forming WDs, NSs, and BHs, respectively, according to our assumptions (Sect. 2.5). We expect that the numbers in Table 3 and Fig. 6 are complete, except for the WDs (Mi, 1 ≤ 10 M⊙). Note, however, that while the initial mass limits for forming a certain compact object type are rather sharp for Case B binaries, the emerging helium star mass in Case A systems is not only a function of the initial donor mass but also of the initial orbital period (Wellstein et al. 2001; Schürmann et al. 2024). We can see the effect of this in Fig. 2, which shows that 17.8 M⊙ donors form BHs in Case B systems but NSs in Case A evolution (see also the plot for the initial donor mass of 10 M⊙ in Fig. A.1).

Number of post-MS companions of OB stars in our fiducial synthetic SMC population.

|

Fig. 6. Fractions of different types of post-MS companions of OB stars in our fiducial synthetic binary population relative to all post-MS companions, as a function of the mass of the OB star. For the companions, we distinguish core-helium burning stars (magenta), white dwarfs (blue), NSs (yellow), and BHs (grey). Shading identifies those companions that are paired with an OB star that rotates with more than 95% of its critical rotational velocities. The absolute number of binaries with post-MS companions expected in the SMC for each mass bin is given on top of the bin. The high-mass end (30–100 M⊙) is presented with a wider bin width. |

Table 3 further gives the predicted number of OB+WR binaries, and for the much smaller fraction of them in which the WR star is expected to be hydrogen-free. We also gave the small number of WR stars produced in very massive and very close binaries in our sample undergoing chemically homogeneous evolution (CHE; see below) in Table 3, for completeness. Finally, we listed the predicted number of OB stars with NS and BH companions. We also counted the number of binaries that are disrupted due to the adopted NS birth kick in Table 3, while Fig. 6 shows only the remaining binaries. Since our fiducial model ignores BH birth kicks, none of our model binaries is broken up when a BH is formed.

In Table 3 and Fig. 6, we also distinguished systems, in which the mass gainer is spun up to close-to-critical rotation and designate them as OBe stars. Notably, we find that 60–100% of the post-interaction systems contain an OBe star. Besides the high efficiency of the spin-up process, these numbers reflect the generally low mass-loss rates of our SMC MS star models, which effectively spins down star only above ∼30 M⊙.

Our overview plot for 10 M⊙ donors (Fig. A.1) shows that we expect the lowest-mass MS stars with a NS companion to have ∼6.5 M⊙. Similarly, Fig. 2 shows that the lowest mass OB+BH progenitors have initial mass ratios near ∼0.35, implying BH companion masses above ∼6.2 M⊙. Therefore, we do not expect NS or BH binaries in mass bins to the left of the 6 − 8 M⊙ bin in Fig. 6. The numbers on top of the bins in Fig. 6 show that the number of systems with MOB > 100 M⊙ that we might be missing is negligible.

As is shown in Fig. A.1, we expect Case C mass transfer (mass transfer with a core-He depleted mass donor) in a small range of initial orbital periods for initial donor masses ≲15.8 M⊙. Furthermore, about half of them may undergo stable mass transfer (Ercolino et al. 2024). We ignored those in our statistics, because they have a negligible lifetime as post-interaction binary given that they have exhausted He in their core before the mass transfer begins. Their fates are uncertain and may be quite diverse (Marchant et al. 2021; Ercolino et al. 2024).

To interpret the numbers shown in Table 3 and Fig. 6, it is helpful to consider some basic trends in our summary plots (Fig. 2 and Appendix A). For the lowest initial donor masses in our model grid (5 M⊙, Fig. A.1), binaries that can avoid merging occupy a small corner in the Case A regime and a somewhat larger triangular region in the high-mass ratio region of the Case B regime, and the models with the largest orbital periods are non-interacting systems. This shows, in agreement with many previous detailed binary evolution calculations (Pols 1994; Wellstein et al. 2001; de Mink et al. 2007), that only ∼10% of all binary systems with donor masses of 5 M⊙ are expected to survive their first mass transfer, and appear in Table 3 and Fig. 6. The other ∼90% are expected to merge4. For larger initial donor masses, the surviving fraction increases and reaches about 60% above 30 M⊙.

Our population synthesis model predicts a similar number of OB+He-star systems in the SMC formed from the initial mass ranges of NS (Mi ≃ 10–17 M⊙: 20.9) and of BH progenitors (Mi ≳ 17 M⊙: 23.1). This is so because the IMF predicts a similar number of systems in both mass ranges, and the shorter lifetime of the more massive binaries is compensated for by a smaller merger fraction. Notably, our fiducial model also predicts 6.7 WR+O star binaries. Consistent with Fig. 5, many more BH-binaries (210) than NS-binaries (24.7) are predicted to exist in the SMC, most of them with OBe type MS components.

Besides the binaries emerging from stable mass transfer, there are 0.04 O+WR and 0.32 O+BH having close orbits but not undergoing any mass transfer. These binaries are formed from tidally induced CHE (de Mink et al. 2009; Marchant et al. 2017). The primary stars are spun up by tides, and the enhanced rotational mixing prevents the establishment of the chemical gradient. Consequently, the stars evolve directly into helium stars without significant expansion. In our model grid, this process occurs with initial primary mass above 70 M⊙, initial mass ratio below 0.4, and initial orbital period around 1.6 days. This small parameter space makes the expected number of CHE products in the SMC very small (see below). In addition, CHE can also occur in massive near-equal-mass binaries, which does not produce O+BH phases but only very brief WR+BH phases (Marchant et al. 2016).

Figure 6 shows the predicted relative fractions of compact and He-star companions to OB stars as the function of mass. The total BH fraction is nearly constant at about 70%. The OBe fraction is a decreasing function of the OB stars mass. Here, most MS star companions below ∼15 M⊙ are Be stars. For higher masses, the OBe+BH fraction drops, which reflects the growing fraction of Case A systems, where stars are braked by tides. Above 40 M⊙, stars are spun down through wind braking. The NS fraction reaches a maximum near MOB = 8 M⊙ with a value about 20% and then decreases to zero near 30 M⊙. The most massive O+NS binaries form in Case A systems, which feature a strong tidal interaction and a high accretion efficiency. The He-star fraction is nearly constant with ∼20%, which is in the range inferred by El-Badry et al. (2022). A distribution of OB star masses in NS and BH binaries is provided in Fig. G.5.

3.4. Properties of OB+He/WR binary systems

Here, we first discuss the observable properties of the WR+O star binaries in our fiducial synthetic population. We compare those with the observed SMC WR stars in Sect. 5.4. The total predicted number of WR stars in the SMC is 6.7. All of them are formed through binary interaction, including tide-induced CHE, as the adopted mass-loss rate is not high enough to form WR stars through wind-stripping (see Fig. G.1 for our non-rotating single star models).

The top panel of Fig. 7 shows the predicted distribution of the WR components of OB+WR binaries in the HR-diagram, together with its 1D-projections in the top and right plots. The predicted effective temperatures of most of WR models are slightly cooler than those of pure He star models (blue line in Fig. 7). While the H-rich envelope of these donor stars gets nearly completely stripped by mass transfer, the remaining hydrogen leads to larger radii and smaller surface temperatures of stripped stars, compared to hydrogen-free models (Schootemeijer & Langer 2018; Gilkis et al. 2019; Laplace et al. 2020). In the majority of our models, the hydrogen layer is not removed by the relatively weak winds in the WR phase at this metallicity. In our synthetic population, the WR models with log Teff/K = 4.9 have a surface hydrogen mass fraction of about 0.3. Models with a surface temperatures above log Teff/K = 5.1 are hydrogen-free WR. The predicted population is sharply cut off at log L/L⊙ = 5.6 due to the threshold luminosity for defining WR stars (see Sect. 2.4). Towards the higher luminosities, the predicted number drops as a consequence of the adopted IMF.

|

Fig. 7. Distributions of properties of the predicted SMC OB+WR binary population. The top panel shows the distribution of the predicted position of the WR components in the Hertzsprung Russell diagram (background colours), where the colour indicates the expected number per pixel (see colour bar on the top right). The total number of observed WR star components, or WR binaries, is four. The plots to the right and on top give the 1D-projections of the distribution, with the inset magnifying the WR binaries produced via chemical homogeneous evolution (CHE). The black circles and diamonds represent the WR components of the observed WR binaries, and single WR stars, in the SMC (Foellmi et al. 2003; Foellmi 2004; Koenigsberger et al. 2014; Hainich et al. 2015; Shenar et al. 2016, 2018), where the numbers are related to the identifier, e.g. ‘1’ for ‘SMC AB1’. The dashed blue line is the zero-age main sequence of helium star models (He-ZAMS) with SMC metallicity (Köhler et al. 2015), with the indicated helium star masses. The bottom panel shows the distribution of the predicted WR binaries in the plane of orbital period versus the orbital velocity of the WR component. Here, the black symbols represent the projected orbital velocity semi-amplitudes of the observed WR+O star binaries (circles) and of the WR+WR binary SMC AB5 (diamond). |

The bottom panel of Fig. 7 shows the distribution of the orbital periods of our OB+WR binary models, and the orbital velocities of the WR components. The orbital periods span a wide range, from ∼3 days to ∼3 years, with about half of the population below 30 days. We do not find shorter-period WR binaries because our ZAMS binaries with the shortest initial orbital periods evolve into contact and eventually merge due to L2-overflow (orange colour in Fig. A.2). The relation between the orbital velocity, υorb, WR, and orbital period, Porb, is determined by

where MWR is the mass of WR star, and G is the gravitational constant. The corresponding orbital velocities go beyond 400 km s−1 for the short period models, and go down to ∼20 km s−1 for the longest period binaries. The orbital velocity distribution between 200 km s−1 and 350 km s−1 is rather flat because the accretion efficiency in our Case A binaries is increasing towards shorter periods, increasing the scatter in stellar masses in Eq. (10). In about two thirds of our WR binary models, the O star is more massive than the WR star (see Fig. G.3).

The insets in Fig. 7 magnify the small contributions from binary models that evolve through mass transfer and produce hydrogen-free WR stars, and those that form WR stars through CHE, which avoid mass transfer (cf. Table 3). While CHE WR stars are expected to have a hydrogen-rich phase during late hydrogen burning and early helium burning (Koenigsberger et al. 2014; Schootemeijer & Langer 2018), we did not include this short phase in our statistics (cf. Fig. G.2).

Our fiducial SMC population also contains a large number of OB+He-star binaries, in which the wind of the He-star is expected to be transparent such that WR-type emission lines would not be produced. These so-called ‘stripped star binaries’ largely lack observed counterparts (Götberg et al. 2023; Drout et al. 2023). It has been suggested that, at least the more massive of such systems, may appear as hard X-ray sources, with X-rays being produced by the collision of the He-star wind with the OBe disc and the OBe star wind (Langer et al. 2020a). While their correspondence to the sub-class of BeXBs called γ Cas-stars is debated (Nazé et al. 2022; Gunderson et al. 2025), the nature of the companion to OBe stars in observed BeXBs is often unclear. Therefore, the predicted OB+He-star binaries could contribute to the large BeXB population of the SMC. This would reduce the discrepancy between our predicted number of OBe-NS systems and the observed number of BeXBs (cf. Sects. 3.5, 5.2).

3.5. Properties of OB+NS binary systems

We find ∼25 OB+NS binaries in our fiducial synthetic population (cf. Table 3). We compare the synthetic with the observed population in Sect. 5.2 and discuss implications in Sect. 6. Figure 8 presents their orbital period distribution. We find two distinct sub-populations with orbital period peaks near 10 and 150 days, which are associated with the different modes of mass transfer. As is seen in Figs. 2 and A.1, OB+NS binaries are formed from two clearly separated triangular regions in the Case A and Case B regimes due to the upper limit on mass transfer rate set by Eq. (1). In addition, some OB+NS binaries have orbital periods exceeding the upper initial orbital period bound (≃3000 days), which are widened by the SN kicks.

|

Fig. 8. Distributions of the orbital periods of the ∼25 OB+NS binaries in our fiducial synthetic SMC population. Upper left: Predicted period distribution (yellow histogram), where the ∼21 OB+NS binaries in which the OB stars rotates faster than 95% of their critical rotational velocity are indicated by shading (labelled ‘OBe’). The period distribution of observed BeXBs in the SMC (Haberl & Sturm 2016) is plotted as purple line. Upper right: A zoom-in of the upper left panel. The B star + radio pulsar binary J0045-7319 (Bell et al. 1995) and the supergiant X-ray binary SMC X-1 (Rawls et al. 2011; Falanga et al. 2015) are indicated by arrows. Lower left: The same predicted distribution as in the top panels, with the colours indicating which of the systems formed through Case A and Case B mass transfer (blue and orange, respectively), with the corresponding total numbers given in the legend. Lower right: The same predicted distribution as in the top panels, with the colours indicating which type of SN, and therefore which NS kick distribution, was assumed for the different systems [green for electron-capture SN; red for helium-envelope-stripped SN (CCSN-C); purple for hydrogen-envelope-stripped SN (CCSN-He); cf. Sect. 2.6]. The predicted total numbers related to different SN types are given in the legend. |

Depending on the final structure of our donor stars, we assumed that NSs are formed through different types of SNe, with correspondingly different NS birth kick distributions (cf. Sect. 2.6) are distinguished. We find ∼6.8 OB+NS binaries in which the NS was assumed to form via an electron capture SN (ECSN), 13.9 via hydrogen-stripped (CCSN-He), and 3.8 vie helium-stripped SNe (CCSN-C). ECSNe contribute a considerable fraction of the population at orbital period around 150 days, where the second dredge up of the primary star, which would reduce the helium core mass in single stars, is avoided due to the mass transfer, making ECSNe to occur much more frequently than in single stars (Podsiadlowski et al. 2004). We see that systems with a He-envelope-stripped SN prefer narrow orbits since the binary has to be close enough to get the donor star deeply stripped (also see Ercolino et al. 2025). Systems with H-envelope-stripped SNe do not show a strong orbital period preference.

Figure 9 presents the predicted distribution of eccentricities of our OB+NS binary population. It peaks at around 0.3. The OB stars of highly eccentric binaries have the chance to fill their Roche lobe during periastron passage, which causes the number of systems to drop in the high-eccentricity region. Due to the difference in the magnitude of the adopted kicks, ECSN mainly contributes binaries with e ∼ 0.3, while stripped SN contributes most of high-e binaries.

|

Fig. 9. Distribution of the eccentricities of our OB+NS model binaries, with the colours indicating which type of SN was assumed for the different systems, as in the bottom right panel of Fig. 8. |

We further show the distribution of OB+NS binaries in the orbital period-eccentricity plane in Fig. 10. We see that wide binaries tend to have higher eccentricities since they are more easily disrupted than close binaries. Further, this plot confirms the prediction of two distinct populations with orbital periods of ∼10 d and ∼150 d, which have similar eccentricity distributions. The upper left edge is populated by systems that undergo Roche lobe overflow (RLO) during periastron passage.

|

Fig. 10. 2D distribution of the ∼24 OB+NS binaries of our fiducial synthetic SMC population in the orbital period – eccentricity plane. The number in each pixel is colour-coded. The 7 SMC BeXBs with eccentricity measurements (Townsend et al. 2011; Coe & Kirk 2015) are indicated by black diamonds. The B star + radio pulsar binary (Kaspi et al. 1994; Bell et al. 1995) is marked by a black star, the supergiant X-ray binary SMC X-1 by a black triangle (Falanga et al. 2015). |

3.6. Properties of OB+BH binary systems

Figure 11 gives an overview of selected properties of the OB+BH binaries in our fiducial synthetic SMC population. The total number of predicted systems is ∼210, which means that ∼5% of the O and early B stars are expected to have a BH companion (Sect. 3.2). The top histogram of Fig. 11 implies that the majority of BHs are expected to have B star companions. We find ∼135 systems (64%) with a MS star mass below 15 M⊙, Those systems are predicted to contain rather light BHs (5–10 M⊙ for most, up to 20 M⊙ for ∼10%) in orbits with typically 100 d periods, in which the B star moves with 20–60 km s−1. The top histogram shows that most of these B stars are expected to be Be stars, since the corresponding stellar model rotates faster than with 95% of its critical rotation velocity.

|

Fig. 11. Properties of the ∼211 OB+BH binaries in our fiducial synthetic SMC population (cf. Table 3), as function of the mass of the OB star. The three main plots show the 2D number density distributions of the systems, with the OB star mass on the X axis, and BH mass, orbital period, and OB star orbital velocity semi-amplitude on the Y axis, respectively. The number density is colour coded (see colour bar on the top right). The known OB+BH binaries, irrespective of their host galaxy metallicity, are marked by blue symbols, and correspond to MWC 656 (Casares et al. 2014), Cyg X-1 (Miller-Jones et al. 2021), LMC X-1 (Orosz et al. 2009), M33 X-7 (Ramachandran et al. 2022), VFTS 243 (Shenar et al. 2022a), and HD 130298 (Mahy et al. 2022). The BH nature of the secondary star in MWC 656 debated in the literature. The solution by Janssens et al. (2023) is labelled by ‘MWC 656 (new)’ and connected to the solution by Casares et al. (2014) through a red line. The four histograms give the corresponding 1D projections, with shading identifying rapidly rotating OB stars (labelled ‘OBe’), and insets magnifying the small contributions from chemically homogeneous evolution (CHE). The orbital velocity semi-amplitudes for observed systems are calculated using Eq. (11) with the observed masses and orbital periods. The errors are calculated by error propagation. |

The O star systems are expected to contain BHs spanning a wider mass range, with 95% of them in the range of 5–25 M⊙, and a few with BHs up to 35 M⊙. There orbital periods and orbital velocities spread a bit wider than those of the B star systems, and in particular we expect O star systems with orbital periods below 10 d, with O star orbital velocities of up to 200 km s−1. However, also many systems with wider orbits and orbital velocities well below 100 km s−1 are predicted. As in the B star regime, most O type companions are found to rotate very rapidly.

The expected number of systems drops for higher MS star masses, mostly because of the adopted IMF. Below 10 M⊙, the chance that the companion star is massive enough to form a BH decreases. Our lowest-mass MS star with a BH companion has about 6 M⊙ (cf. Fig. 6). The BH mass distribution is also affected by the IMF. The lightest BH we predict has ∼4.9 M⊙, for which the 6.6 M⊙ pre-collapse star ejected about 0.5 M⊙ of helium-rich envelope, and 1.2 M⊙ is lost due to the release of gravitational binding energy. The most massive BH in our model sample weighs about 35 M⊙, and the mass ejection from its progenitor is set by the pulsational-pair instability (PPI) mechanism (cf. Sect. 2.5).

The majority of our OB+BH binaries have orbital periods around 100 days. Binaries that are widened by the PPI-induced mass loss occupy the period regime above 3000 days. The effect of tides, which can limit the spin-up of the accreting MS star, is relevant only in the closest binaries. Therefore we expect OBe companions to BHs in most of the wide binaries ( Porb > 10 days), while slower rotators dominate in closer binaries. The most massive MS stars may rotate relatively slowly even in wide binaries because of wind braking (Langer 1998).

The models in our grid that in principle could produce the OB+BH systems with the most massive MS stars are those very massive systems that start with a mass ratio close to 1. However, at higher initial primary masses, the minimum initial mass ratio above which the secondary star ends core hydrogen burning before the primary ends its life is decreasing (Fig. A.2)5. Therefore, those systems are assumed to merge when reverse mass transfer starts, such that they do not contribute to our synthetic SMC compact object binary population. Very massive OB stars are also not produced from the most massive systems with lower mass ratios because the accretion efficiency is quite limited, and stellar wind mass loss is also considerable at the highest masses. Therefore, our population has no statistically significant contribution to the BH binary population at OB star masses above about 70 M⊙.

Comparing with the orbital period distribution of our NS binaries (Fig. 8 and G.6), we see that the clear signature of the two different modes of mass transfer is absent in the BH binary period distribution (middle panel in Fig. 11). The reason is that more binaries near the Case A/B boundary avoid merging in the BH-forming regime compared to the NS-forming regime (see Fig. A.2), which fills the orbital period gap between the two modes.

The lowest panel of Fig. 11 presents the distribution in the OB star mass – orbital velocity semi-amplitude of OB star, KOB, plane. In contrast to the WR binaries, which are assumed to be circular as consequence of the RLO, the assumed mass loss at BH formation does produce a kick, which makes the orbits mildly eccentric. Therefore, KOB is defined here by

where Mcc is the mass of compact object. Inclination effects are not included here. The mass loss during the BH formation produces eccentricities of less than 0.1, which makes the deviation of the orbital velocities of OB stars from their semi-amplitudes within 10%. Corresponding to the peak of the orbital period distribution of about 100 days seen in the middle panel, our OB+BH binaries have velocity semi-amplitudes peaking near 40 km s−1. The highest velocity semi-amplitudes we find are about 250 km s−1 (Fig. G.6), which is near the initial orbital period boundary between stable mass transfer and L2 overflow (see Figs. 2, A.1, and A.2).

|

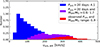

Fig. 12. Orbital period (left plots) and V band magnitude or mass (right) distributions of the OB+NS (top) and OB+BH (bottom) binaries resulting from our parameter variations. The predictions from the different population models are shown with differently coloured lines (see legend), where the predictions from the fiducial model are indicated by the hatched histograms with blue thick lines. The population models that produce the same distributions as the fiducial model are not shown in the corresponding plots. In the bottom plots, the SFH-R distributions are very close to the fiducial ones. We show the distributions of the observed SMC BeXBs in the upper panels with grey histograms. The observed orbital periods and V-band magnitudes of the SMC BeXBs are from Haberl & Sturm (2016). |

4. Parameter variations

Predicted populations derived with various different assumptions.

For our SMC population synthesis, we cannot change the underlying stellar evolution models. Therefore, uncertain assumptions in those, in particular concerning the efficiency of mass transfer or the criterion for unstable mass transfer and merger, cannot be varied here. However, we can vary the parameters that enter directly into the population synthesis calculations. Those are related to assumptions on compact object birth kicks, on the time dependence of the star formation rate, on the initial binary parameter distributions, on the lowest rotation velocity of OBe star, and on the upper core mass limit for NS formation. With this idea, we introduce the following population synthesis models, in which only the mentioned parameter differs from the parameters adopted in our fiducial population synthesis calculation.

-

Kick-265: the distribution of NS kick velocities was taken to be the Maxwellian distribution with σ = 265 km s−1 for all types of SNe.

-

Kick-0: All kick velocities were fixed to zero.

-

Kick-BH: BHs produced by fallback of previously ejected material may produce a SN and receive a momentum kick at birth (Janka 2012). We adopted a flat distribution in the range [0, 200] km s−1 for natal kicks imparted to newborn BHs (Kruckow et al. 2018, and Paper II);

-

logPq-flat: we used flat distributions for the initial mass ratios and logarithms of the orbital periods of our binaries.

-

SFH-S: we assumed a star formation history with no star-formation at the present time that increases up to 7 Myrs ago, before which it stays constant (see the upper panel in Fig. 13).

-

SFH-R: we assumed a star formation rate with a recent peak ∼20 − 40 Myrs ago (Rubele et al. 2015, ; see the lower panel in Fig. 13).

Fig. 13. Star formation history adopted to compute the population models SFH-S (upper panel, Schootemeijer et al. 2021) and SFH-R (lower panel, Rubele et al. 2015), where the dashed line indicates the constant star formation rate of 0.05 M⊙ yr−1 used in the fiducial model.

-

vcrit-0.98: the threshold value of υrot/υcrit for defining OBe stars was taken to be 0.98.

-

vcrit-0.8: the threshold value of υrot/υcrit for defining OBe stars was taken to be 0.8.

-