| Issue |

A&A

Volume 705, January 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A26 | |

| Number of page(s) | 26 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202451034 | |

| Published online | 08 January 2026 | |

A three-dimensional reconstruction of the interstellar magnetic field toward a star-forming region

IRAP, Université de Toulouse, CNRS,

9 avenue du Colonel Roche,

BP 44346,

31028

Toulouse Cedex 4,

France

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

7

June

2024

Accepted:

29

September

2025

Context. The polarized thermal emission from interstellar dust offers a valuable tool for probing both the dust and the magnetic field in the interstellar medium (ISM). However, existing observations only yield the total amount of dust emission along the line of sight (LoS), with no information on its LoS distribution.

Aims. We present a new method designed to give access to the LoS distribution of the dust emission, both in terms of intensity and polarization.

Methods. We relied on three kinematic gas tracers (HI, 12CO, and 13CO emission lines) to identify the different clouds present along the LoS. We decomposed the measured intensity of the dust emission, Id, into separate contributions from these clouds. We performed a similar decomposition of the measured Stokes parameters for linear polarization, Qd and Ud, to derive the polarization parameters of the different clouds, and from this we inferred the clouds’ magnetic field orientations.

Results. We applied our method to a 3 deg2 region of the sky, centered on (l, b) = (139°30′, −3°16′) and exhibiting signs of star formation activity. We found this region to be dominated by an extended and bright cloud with nearly horizontal magnetic field, as expected from the nearly vertical polarization angles measured by Planck. More importantly, we detected the presence of two smaller, depolarizing molecular clouds with very different magnetic field orientations in the plane of the sky (≃65° and ≃45° from the horizontal). This is a novel and viable result, which cannot be directly read off the Planck polarization maps.

Conclusions. The application of our method to the G139 region convincingly demonstrates the need to complement 2D polarization maps with 3D kinematic information when looking for reliable estimates of magnetic field orientations.

Key words: ISM: clouds / dust / extinction / ISM: kinematics and dynamics / ISM: magnetic fields

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

The sky offers a 2D view of the cosmos and one of the main challenges of observational astrophysics is to gain access to the line-of-sight (LoS) dimension. The latter is crucial to uncover the true physical properties and understand the exact inner workings of our cosmic environment. For instance, in the case of our Galaxy, access to the LoS dimension makes it possible to retrieve the 3D distribution of interstellar matter (Lallement et al. 2019, 2022; Green et al. 2019; Chen et al. 2019; Leike & Enßlin 2019; Leike et al. 2020; Hottier et al. 2020; Zucker et al. 2021; O’Neill et al. 2024); in turn, this paves the way to studying the dynamics of the interstellar medium (ISM), the formation and evolution of interstellar structures, and, ultimately, the whole cycle of matter between stars and the ISM. It is evident that 2D images alone are insufficient to reach that goal, as they afford only a partial, and possibly misleading, perspective on the observed medium. In general, integration along the LoS results in a loss of information on the spatial variations of physical properties such as temperature, volume density, emissivity, and so on. The loss of information is more severe in the case of vectorial quantities, such as polarization vectors, which can add up either constructively or destructively. As a result, LoS integration can cause depolarization of an intrinsically polarized signal; for instance, when the magnetic field orientation varies along the LoS (Planck Collaboration 2015b, 2017; Clark 2018; Pelgrims et al. 2021) or in the presence of Faraday rotation (Sokoloff et al. 1998; Beck 2001). Another issue is that projecting onto the plane of the sky (PoS) can distort our perception of certain classes of objects (cores, clumps, filaments, etc.) as well as our estimation of their geometric characteristics (size, aspect ratio, relative orientation angle, etc.) and, accordingly, bias the related statistical analyses (e.g., Planck Collaboration 2016a; Padoan et al. 2023).

There are a range of tools available to help probe the LoS dimension. For instance, turning to spectroscopy, we can infer, from the profile of a spectral line, the brightness distribution as a function of radial velocity (RV) and then we can use the RV as a proxy for LoS coordinate. The direct output is a 3D map of the line brightness as a function of position in the sky and RV, known as a spectral cube. To convert from RV to LoS coordinate (and, thus, obtain a physical cube), we can rely on objects whose distances can be measured directly (e.g., via the parallax) or indirectly (e.g., via bracketing or standard candles).

Observations of the Galactic magnetic field are no exception, as they are also plagued by the lack of information along the LoS. The classical observational methods based on Fara-day rotation, synchrotron emission, and dust polarization provide only LoS-integrated quantities, with no information on how the integrant (Faraday rotation rate, synchrotron emissivity, or dust emissivity) varies along the LoS. Several avenues have been proposed to (partially) overcome this problem and, thus, gain (partial) access to the 3D structure of the Galactic magnetic field. Here, we note three possible approaches, based on polarization of starlight, Faraday rotation of pulsar signals, and Faraday tomography, respectively.

The polarization of starlight presumably results from its interaction with interstellar dust grains that are aligned by the interstellar magnetic field. The measured polarization orientation directly gives the orientation of B⊥1, while the measured polarization fraction can, under certain conditions, provide an estimate of the inclination of B to the PoS. If B varies along the LoS, the inferred orientation and inclination angles are dust-weighted averages between the considered star and the observer. By considering a large number of stars distributed in space and combining their measured polarization parameters with their measured distances (e.g., from Gaia), we can reconstruct the orientation of B⊥ (or possibly B) in 3D. This type of tomographic mapping of B⊥ was performed toward the Perseus molecular cloud (Doi et al. 2021), toward the Southern Coalsack dark nebula (Versteeg et al. 2024) and toward a portion of the Sagittarius spiral arm (Doi et al. 2024). For the larger datasets from the optical polarization survey PASIPHAE, an automated, Bayesian LoS-inversion method was developed by Pelgrims et al. (2023) and later applied by Pelgrims et al. (2024) to a 4 deg2 region of the sky, centered on (l, b) = (103.3°, 22.3°).

Faraday rotation of the linearly polarized radio waves emitted by Galactic pulsars occurs in ionized regions of the ISM, i.e., mainly in the warm ionized medium (WIM), where radio waves interact with the thermal electrons of the medium. The angle by which the polarization orientation rotates is equal to the observing wavelength squared, λ2, times the rotation measure,  , where ne is the thermal-electron density and L the path length from the pulsar to the observer. Aside from the RM of a pulsar, we can also measure its dispersion measure,

, where ne is the thermal-electron density and L the path length from the pulsar to the observer. Aside from the RM of a pulsar, we can also measure its dispersion measure,  . The ratio of RM to DM directly yields the ne-weighted average value of B∥ between the pulsar and the observer. By combining the average values of B∥ toward all pulsars with measured RM and DM (roughly 1 500 at the present time) with their measured distances, we can map out the large-scale 3D distribution of B∥ (e.g., Han et al. 2018; Sobey et al. 2019).

. The ratio of RM to DM directly yields the ne-weighted average value of B∥ between the pulsar and the observer. By combining the average values of B∥ toward all pulsars with measured RM and DM (roughly 1 500 at the present time) with their measured distances, we can map out the large-scale 3D distribution of B∥ (e.g., Han et al. 2018; Sobey et al. 2019).

Faraday tomography also relies on Faraday rotation, but instead of considering the Faraday rotation of the linearly polar-ized radiation from a background radio source, we can exploit the λ2-dependent Faraday rotation of the synchrotron radiation from the Galaxy itself (Burn 1966; Brentjens & de Bruyn 2005). More precisely, we can measure the Galactic polarized intensity at many different radio wavelengths and then convert its variation with λ2 into a variation with LoS coordinate. The standard output of Faraday tomography is a so-called Faraday cube, namely, a 3D map of the synchrotron polarized emission as a function of position in the sky and Faraday depth, which is the equivalent of physical depth measured in terms of Faraday rotation. In practice, Faraday tomography can be used to separate synchrotron-emitting regions located at different Faraday depths and to estimate their respective synchrotron polarized intensities, which, in turn, can lead to the strength and the orientation of their B⊥. Faraday tomography can also be used to uncover intervening Faraday screens and to estimate their Faraday thicknesses, which, in turn, can lead to their B∥. The method is particularly interesting when the uncovered Faraday screens can be identified with known gaseous structures because it then offers a new way of probing their magnetic fields. Faraday tomography was successfully applied to several regions of the sky, including small fields centered on the nearby galaxy IC 342 (Van Eck et al. 2017) and the extra-galactic point source 3C 196 (Turić et al. 2021), as well as a much larger area toward the high-latitude outer Galaxy (Erceg et al. 2022, 2024).

Aside from these three classical methods, Hu & Lazarian (2023) proposed a more indirect approach to map out the 3D distribution of the orientation and strength of B⊥, based on the application of the velocity gradient and two Mach number techniques to Hi spectroscopic observations.

In this paper, we propose a new 3D polarimetric approach, which combines two of the well-proven observational tools described above, namely, 3D spectral cubes and dust polarization. Compared to the starlight polarimetric approach, which utilizes the polarization of stars with measured distances, we rely on the polarization of the thermal emission from interstellar dust, which we connect to kinematic gas tracers with measured spectral cubes. Thus, our method combines two complementary datasets: spectral cubes of atomic (HI) and molecular (12CO and 13CO) gas tracers and polarization maps of the dust emission. The former contain the kinematic information needed to locate the dust-emitting structures along the LoS, albeit in terms of RV rather than physical distance, and the latter provide the polarization information needed to reconstruct the magnetic field orientation.

In Sect. 2, we lay out the general method. In Sect. 3, we apply our method to a 104′ × 104′ area of the sky containing a star-forming region. In Sect. 4, we discuss our results and present our conclusions.

2 General method

In this section, we introduce the general equations needed in our study and we explain how we can identify the different dust-emitting clouds along the LoS and estimate their magnetic field orientations. In Sect. 2.1, we present the basic equations describing the polarized dust emission. In Sect. 2.2, we introduce our atomic (HI) and molecular (12CO and 13CO) kinematic gas tracers, combine the latter into a single molecular (CO) tracer, and connect the dust emission to the Hi and CO tracers via conversion factors. In Sect. 2.3, we explain how the measured intensity of the dust emission can be decomposed along the LoS into the contributions from different clouds identified with the help of the kinematic gas tracers. In Sect. 2.4, we show how the polarization parameters of the different clouds can be fitted to the observed polarization maps of the dust emission and used to infer the orientations of their internal magnetic fields, which we assume to be uniform. Along the way, we make it clear that our LoS decomposition has degeneracies, with implications for the validity of our derived magnetic field orientations. We also propose a convergence test to identify the magnetic field orientations that are truly reliable.

2.1 Polarized dust emission

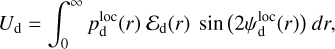

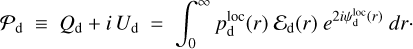

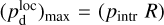

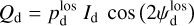

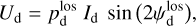

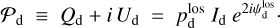

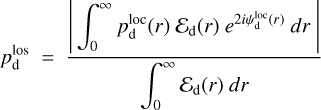

The polarized thermal emission from interstellar dust, integrated along the LoS, can be described by three quantities: the intensity,

(1)

and the two Stokes parameters for linear polarization,

(1)

and the two Stokes parameters for linear polarization,

(2)

and

(2)

and

(3)

where r denotes the LoS distance from the observer, subscript d stands for dust, Ed(r) is the local emissivity of the dust thermal emission,

(3)

where r denotes the LoS distance from the observer, subscript d stands for dust, Ed(r) is the local emissivity of the dust thermal emission,  the local polarization fraction, and

the local polarization fraction, and  the local polarization angle (increasing counterclockwise from Galactic north). Equations (2) and (3) can be combined into a single equation for the complex polarized intensity,

the local polarization angle (increasing counterclockwise from Galactic north). Equations (2) and (3) can be combined into a single equation for the complex polarized intensity,

(4)

(4)

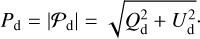

The norm of the complex polarized intensity is generally referred to as the (real) polarized intensity,

(5)

(5)

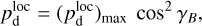

The local polarization fraction can be written as

(6)

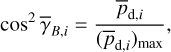

where γB is the inclination angle of the local magnetic field to the PoS,

(6)

where γB is the inclination angle of the local magnetic field to the PoS,  is the theoretical maximum polarization fraction that can be achieved locally, pintr is the intrinsic polarization fraction, which depends on the shape, elongation, and material of dust grains, and R is the Rayleigh reduction factor, which accounts for the imperfect alignment of dust grains2 (see, e.g., Planck Collaboration 2015a, and references therein). The local polarization angle is related to the orientation angle of the local magnetic field in the PoS, ψB, via

is the theoretical maximum polarization fraction that can be achieved locally, pintr is the intrinsic polarization fraction, which depends on the shape, elongation, and material of dust grains, and R is the Rayleigh reduction factor, which accounts for the imperfect alignment of dust grains2 (see, e.g., Planck Collaboration 2015a, and references therein). The local polarization angle is related to the orientation angle of the local magnetic field in the PoS, ψB, via

(7)

(7)

The ±90° term in Eq. (7) arises because both orientation angles are defined within a 180° range, for instance, in the range [−90°, +90°].

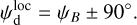

The LoS-averaged polarization fraction is given by

(8)

and the LoS-averaged polarization angle by

(8)

and the LoS-averaged polarization angle by

(9)

with arctan the two-argument arctangent function defined from −180° to +180°. Equations (8) and (9) are equivalent to the pair of equations

(9)

with arctan the two-argument arctangent function defined from −180° to +180°. Equations (8) and (9) are equivalent to the pair of equations

(10)

and

(10)

and

(11)

which can be rewritten in complex form as

(11)

which can be rewritten in complex form as

(12)

(12)

The link between the LoS-averaged polarization fraction and angle and their local counterparts is easily obtained by equating Eq. (12) to Eq. (4), while keeping Eq. (1) in mind,

(13)

and

(13)

and

(14)

(14)

The physical meaning of Eqs. (13) and (14) is pretty straightforward: the LoS-averaged polarization fraction,  , is a dust-weighted LoS average of the local polarization fraction,

, is a dust-weighted LoS average of the local polarization fraction,  , reduced by a LoS depolarization factor,

, reduced by a LoS depolarization factor,  , due to fluctua tions in the local polarization angle; the LoS-averaged polarization orientation, defined by the LoS-averaged polarization angle,

, due to fluctua tions in the local polarization angle; the LoS-averaged polarization orientation, defined by the LoS-averaged polarization angle,  , is a dust-weighted LoS average of the local polarization orientation, defined by the local polarization angle,

, is a dust-weighted LoS average of the local polarization orientation, defined by the local polarization angle,  . In reality, observations do not strictly capture a single LoS, but rather a whole telescope beam. Therefore, in practice, the LoS integrals in Eqs. (13) and (14) are actually integrals over a telescope beam, and the associated averaging and depolarization actually occur both along the LoS and across the telescope beam. Observational values of

. In reality, observations do not strictly capture a single LoS, but rather a whole telescope beam. Therefore, in practice, the LoS integrals in Eqs. (13) and (14) are actually integrals over a telescope beam, and the associated averaging and depolarization actually occur both along the LoS and across the telescope beam. Observational values of  are discussed in Appendix B.

are discussed in Appendix B.

2.2 Kinematic gas tracers and conversion factors

2.2.1 Kinematic gas tracers

It is often implicitly assumed that the local polarization fraction and angle are uniform along the LoS through (most of) the dust-emitting region. This assumption makes it possible to infer their values from the observed LoS-averaged polarization fraction and angle, respectively,  and

and  . In reality, however, the LoS is likely to intersect several clouds with different polarization properties. In that case, the polarization fraction and angle of the different clouds cannot be immediately inferred from the observed dust emission. Other tracers, such as kinematic gas tracers, are needed to estimate them separately.

. In reality, however, the LoS is likely to intersect several clouds with different polarization properties. In that case, the polarization fraction and angle of the different clouds cannot be immediately inferred from the observed dust emission. Other tracers, such as kinematic gas tracers, are needed to estimate them separately.

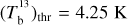

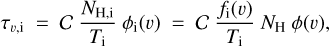

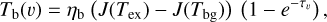

Here, we rely on spectral cubes, namely, 3D maps in (l, b, v) space3, of the brightness temperature, Tb, of the Hi 21 cm, 12CO (1–0) 2.6 mm, and 13CO (1–0) 2.7 mm emission lines, based on the notion that the Hi line traces atomic gas, while the 12CO and 13CO lines together trace molecular gas. In principle, we should also include a spectral cube of the ionized gas, but we assume that the contribution from ionized gas is negligible in the region of interest.

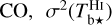

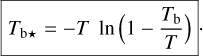

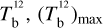

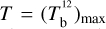

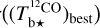

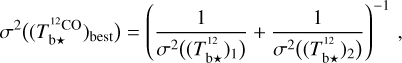

The brightness temperature, Tb, is affected by optical depth effects, undergoing gradual saturation with increasing opacity. Correcting for opacity saturation is a difficult and subtle task, which we address in Appendix A. There, we define an opacity-corrected brightness temperature, Tb⋆, and we derive the equation relating Tb⋆ to Tb (Eq. (A.5)). Since this equation involves the excitation temperature, T, we discuss the choice of the value of T. In brief, we argue in favor of choosing T = 80 K for Hi (see paragraph preceding Eq. (A.13)) and  for CO (see paragraph preceding Eq. (A.20)). Once the values of T are set, we can convert the spectral cubes of

for CO (see paragraph preceding Eq. (A.20)). Once the values of T are set, we can convert the spectral cubes of  ,

,  , and

, and  into spectral cubes of

into spectral cubes of  , and

, and  , respectively, where

, respectively, where  and

and  are two complementary estimates of

are two complementary estimates of  . We can then combine the

. We can then combine the  and

and  spectral cubes into the spectral cube of a best-estimate

spectral cubes into the spectral cube of a best-estimate  (Eq. (A.29)). From now on, superscript 12 in 12CO is dropped for notational simplicity.

(Eq. (A.29)). From now on, superscript 12 in 12CO is dropped for notational simplicity.

The spectral cubes of  and

and  generally have different angular and spectral resolutions, so they first need to be brought to a common angular resolution, δθ, a common spectral resolution, δv, and a common (l, b, v) grid with, say, n1 × n2 pixels. The maps of Id, Qd, and Ud (see Sect. 2.1) also need to be brought to the angular resolution δθ and the n1 × n2 pixel grid.

generally have different angular and spectral resolutions, so they first need to be brought to a common angular resolution, δθ, a common spectral resolution, δv, and a common (l, b, v) grid with, say, n1 × n2 pixels. The maps of Id, Qd, and Ud (see Sect. 2.1) also need to be brought to the angular resolution δθ and the n1 × n2 pixel grid.

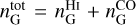

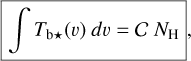

We assume that our  and

and  cubes are complementary, in the sense that together they account for all the gas along the LoS, with no omission and no overlap. It then follows that the hydrogen column density, NH, can be decomposed into the contributions from the gas components probed by Hi and CO,

cubes are complementary, in the sense that together they account for all the gas along the LoS, with no omission and no overlap. It then follows that the hydrogen column density, NH, can be decomposed into the contributions from the gas components probed by Hi and CO,

(15)

(15)

The intensity of the dust emission can be decomposed in a similar way,

(16)

(16)

We make the standard assumption that for each gas tracer A (A = Hi or CO), the intensity of the dust emission associated with that tracer,  , is simply proportional to the hydrogen column density probed by that tracer,

, is simply proportional to the hydrogen column density probed by that tracer,  (e.g., Hildebrand 1983). If we denote the conversion factor from hydrogen column density to dust intensity by

(e.g., Hildebrand 1983). If we denote the conversion factor from hydrogen column density to dust intensity by  , we can then write

, we can then write

(17)

(17)

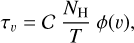

We note that Hi and CO are expected to have slightly different conversion factors, mostly because dust grains have different properties (composition, size, emissivity) in the atomic and molecular media. We further assume that for each tracer A, the hydrogen column density,  , is proportional to the opacity-corrected brightness temperature,

, is proportional to the opacity-corrected brightness temperature,  , integrated over the RV (see Eq. (A.7) in Appendix A),

, integrated over the RV (see Eq. (A.7) in Appendix A),

(18)

where

(18)

where  is the conversion factor from velocity-integrated opacity-corrected brightness temperature to hydrogen column density. Combining Eqs. (17) and (18) leads to

is the conversion factor from velocity-integrated opacity-corrected brightness temperature to hydrogen column density. Combining Eqs. (17) and (18) leads to

(19)

with

(19)

with  . If we now insert Eq. (19) into Eq. (16), we finally obtain for the dust intensity

. If we now insert Eq. (19) into Eq. (16), we finally obtain for the dust intensity

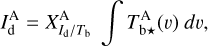

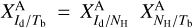

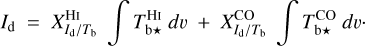

(20)

(20)

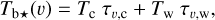

2.2.2 Conversion factors

The observables in Eq. (20) are the dust intensity, Id, and the opacity-corrected brightness temperatures,  and

and  . The conversion factors,

. The conversion factors,  and

and  , are not directly observable, and we did not find any values for them in the literature. We did find separate estimates for some of the intermediate conversion factors, XId/NH and XNH/Tb (see Sect. 3.2), but they were obtained for restricted regions of the sky and they tend to have wide scatter, so they cannot be directly applied to our region of interest.

, are not directly observable, and we did not find any values for them in the literature. We did find separate estimates for some of the intermediate conversion factors, XId/NH and XNH/Tb (see Sect. 3.2), but they were obtained for restricted regions of the sky and they tend to have wide scatter, so they cannot be directly applied to our region of interest.

Here, we treat the conversion factors,  and

and  , as free parameters, and we derive their best-fit values in the considered region by minimizing the reduced χ2, defined by

, as free parameters, and we derive their best-fit values in the considered region by minimizing the reduced χ2, defined by

![$\chi _{\rm{r}}^2 = {1 \over {\left( {{n_{dat}} - {n_{par}}} \right)}}\mathop \sum \limits_{{n_{pix}}} {{{{\left[ {I_{\rm{d}}^{obs} - \left( {I_{\rm{d}}^{HI} + I_{\rm{d}}^{CO}} \right)} \right]}^2}} \over {\sigma _I^2}},$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa51034-24/aa51034-24-eq63.png) (21)

where

(21)

where  is the observed dust intensity,

is the observed dust intensity,  and

and  are the dust intensities associated with Hi and CO, respectively (Eq. (19) with A = Hi and CO), σI is the total observational uncertainty, ndat = npix = n1 × n2 is the total number of data points, npar = 2 is the number of free parameters, and the sum runs over the npix pixels. The total observational uncertainty is the quadratic sum of the measurement errors in

are the dust intensities associated with Hi and CO, respectively (Eq. (19) with A = Hi and CO), σI is the total observational uncertainty, ndat = npix = n1 × n2 is the total number of data points, npar = 2 is the number of free parameters, and the sum runs over the npix pixels. The total observational uncertainty is the quadratic sum of the measurement errors in  , and

, and  ,

,

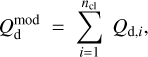

(22)

where

(22)

where

(23)

for A = Hi and CO,

(23)

for A = Hi and CO,  and

and  are given by Eqs. (A.13) and (A.30), respectively, δv is the spectral resolution, and the sum runs over all the velocity bins.

are given by Eqs. (A.13) and (A.30), respectively, δv is the spectral resolution, and the sum runs over all the velocity bins.

Minimization of  is performed through Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations. Since MCMC simulations alone consider only measurement errors, which in the case at hand are potentially dominated by modeling errors (namely, errors in Eq. (20) with constant conversion factors), they are likely to underestimate the uncertainties in the best-fit parameters. To obtain meaningful uncertainties,

is performed through Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations. Since MCMC simulations alone consider only measurement errors, which in the case at hand are potentially dominated by modeling errors (namely, errors in Eq. (20) with constant conversion factors), they are likely to underestimate the uncertainties in the best-fit parameters. To obtain meaningful uncertainties,  and

and  , we resort to parametric bootstrap sampling, with each bootstrap sample involving MCMC simulations.

, we resort to parametric bootstrap sampling, with each bootstrap sample involving MCMC simulations.

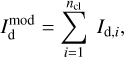

2.3 LoS decomposition into clouds

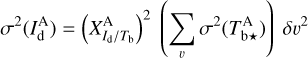

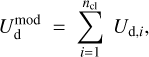

Consider a given LoS and assume that the dust emission measured on that LoS arises from ncl distinct clouds. Here, the term “cloud” is to be understood in a broad sense, which may include intercloud regions. The intensity of the dust emission can then be modeled as the sum of the contributions from the ncl clouds,

(24)

and similarly for the two Stokes parameters for linear polarization,

(24)

and similarly for the two Stokes parameters for linear polarization,

(25)

and

(25)

and

(26)

where the subscript i refers to cloud i. The contributions Id,i, Qd,i, and Ud,i from cloud i have the same expressions as the total Id (Eq. (1)), Qd (Eq. (2)), and Ud (Eq. (3)), respectively, with the LoS integral over an infinite path length replaced by a LoS integral over the path length through cloud i, Li.

(26)

where the subscript i refers to cloud i. The contributions Id,i, Qd,i, and Ud,i from cloud i have the same expressions as the total Id (Eq. (1)), Qd (Eq. (2)), and Ud (Eq. (3)), respectively, with the LoS integral over an infinite path length replaced by a LoS integral over the path length through cloud i, Li.

Next, we use the spectral cubes of the Hi and CO opacity-corrected brightness temperatures,  and

and  , introduced in Sect. 2.2 to identify the different clouds along the LoS.

, introduced in Sect. 2.2 to identify the different clouds along the LoS.

2.3.1 ROHSA decomposition

In a first step, we apply the algorithm ROHSA (Regularized Optimization for Hyper-Spectral Analysis) developed by Marchal et al. (2019) to our  and

and  spectral cubes separately. This algorithm is designed to decompose a spectral data cube, say, a cube of Tb⋆(l, b, v), into several spatially coherent Gaussian kinematic components. The Gaussian decomposition is optimized over the entire data cube at once, with the requirement that the solution must be spatially smooth.

spectral cubes separately. This algorithm is designed to decompose a spectral data cube, say, a cube of Tb⋆(l, b, v), into several spatially coherent Gaussian kinematic components. The Gaussian decomposition is optimized over the entire data cube at once, with the requirement that the solution must be spatially smooth.

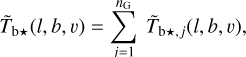

In mathematical terms, the observed Tb⋆(l, b, v) is approximated by a modeled  , equal to the sum of nG Gaussian components,

, equal to the sum of nG Gaussian components,

(27)

where each component j is described by an amplitude Aj(l, b), a mean RV,

(27)

where each component j is described by an amplitude Aj(l, b), a mean RV,  , and a standard deviation, σj(l, b),

, and a standard deviation, σj(l, b),

![${\tilde T_{{\rm{b}} \star ,j}}(l,b,v) = {A_j}(l,b)\exp \left[ { - {{{{\left( {v - {{\bar v}_j}(l,b)} \right)}^2}} \over {2\sigma _j^2(l,b)}}} \right].$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa51034-24/aa51034-24-eq86.png) (28)

(28)

The best-fit values of the 3nG Gaussian parameters, Aj,  , and σj, are derived through minimization of a cost function that includes the standard χ2 term plus a regularization term meant to ensure a spatially smooth solution.

, and σj, are derived through minimization of a cost function that includes the standard χ2 term plus a regularization term meant to ensure a spatially smooth solution.

ROHSA has several free parameters (six in the initial version described in Marchal et al. (2019), and more in the present online version). We keep the default values of these parameters, except for the three hyper-parameters entering the regularization term, λA,  , and λσ. Since our ultimate purpose is to construct smooth, coherent clouds, we need to impose strong constraints of spatial coherence on Aj,

, and λσ. Since our ultimate purpose is to construct smooth, coherent clouds, we need to impose strong constraints of spatial coherence on Aj,  , and σj, which is done by choosing large values for λA,

, and σj, which is done by choosing large values for λA,  , and λσ. After verifying that the exact values are not critical, we adopt λA = λσ = 1000 and

, and λσ. After verifying that the exact values are not critical, we adopt λA = λσ = 1000 and  for our application in Sect. 3. Furthermore, since we want to retain only truly physical components, we discard the extracted components whose velocity-integrated

for our application in Sect. 3. Furthermore, since we want to retain only truly physical components, we discard the extracted components whose velocity-integrated  fall below twice the noise level at every pixel.

fall below twice the noise level at every pixel.

2.3.2 Cloud reconstruction

The second step is to reconstruct the different clouds along the LoS. To that end, we collect all the Gaussian components from both Hi and CO, and we group together the components that have similar velocity profiles. Since the very definition and the exact outline of an interstellar cloud are moot points, the criterion we choose to rely on is necessarily subjective.

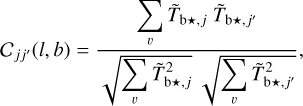

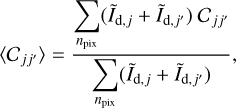

To start with, there is a total of  Gaussian components, which we consider two by two. For every pair of components j and j′ (j ≠ j′), we compute a velocity correlation coefficient at each pixel, (l, b),

Gaussian components, which we consider two by two. For every pair of components j and j′ (j ≠ j′), we compute a velocity correlation coefficient at each pixel, (l, b),

(29)

where the sums run over all the velocity bins. Clearly, Cjj′ depends only on the velocity profiles (mean velocities,

(29)

where the sums run over all the velocity bins. Clearly, Cjj′ depends only on the velocity profiles (mean velocities,  and

and  , and standard deviations, σj and σj′ ) of both components, not on their amplitudes (Aj and Aj′ ). We then compute the average value of Cjj′ (l, b) over all the pixels, weighted by the sum of the dust intensities of components j and j′,

, and standard deviations, σj and σj′ ) of both components, not on their amplitudes (Aj and Aj′ ). We then compute the average value of Cjj′ (l, b) over all the pixels, weighted by the sum of the dust intensities of components j and j′,

(30)

where

(30)

where  is the dust intensity of component j (defined by Eq. (33) below) and the sum runs over the npix pixels.

is the dust intensity of component j (defined by Eq. (33) below) and the sum runs over the npix pixels.

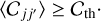

We consider that components j and j′ are correlated, and thus parts of a same cloud, if ⟨𝒞jj’⟩ lies above a certain threshold, 𝒞th

(31)

(31)

It is important to realize that this is a purely kinematic criterion, independent of any possible spatial correlation. This choice is motivated by the fact that while two components of a given cloud are expected to have similar velocity profiles, they do not need to be correlated in space; for instance, they could very well be co-spatial (e.g., a region containing both Hi and CO) or adjacent (e.g., an Hi envelope around a CO core).

A critical issue concerns the choice of the value of 𝒞th. For our application in Sect. 3, we tested all the integer values of 𝒞th between 0 and 100%. Based on the results (summarized in Table 3), we decided to present a detailed analysis in the case 𝒞th = 50% (Sects. 3.3–3.4), considering that this value strikes a good balance between preserving physical clouds and separating distinct clouds along the LoS. The results obtained for other values of 𝒞th as well as their sensitivity to the exact value of 𝒞th are discussed in Sect. 3.5.

Pairs satisfying Eq. (31) are themselves grouped together into one multicomponent cloud if they possess a component in common. For instance, if pairs jk and kl satisfy ⟨𝒞jk⟩ ≥ 𝒞th and ⟨𝒞kl⟩ ≥ 𝒞th, they are grouped into one cloud enclosing components j,k, and l, even if ⟨𝒞jl⟩ < 𝒞th

All the remaining Gaussian components, i.e., the components that are not correlated with any other component (in the sense of satisfying Eq. (31)), are considered to each form a separate cloud.

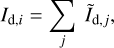

Altogether, we end up with ncl distinct clouds made up of one, two, or more Gaussian components. The dust intensity of cloud i, Id,i can be written as a sum over the nG,i Gaussian components of cloud i:

(32)

where the dust intensity of component j, Ĩd,j, is related to its opacity-corrected brightness temperature,

(32)

where the dust intensity of component j, Ĩd,j, is related to its opacity-corrected brightness temperature,  (Eq. (28)), through an equation similar to Eq. (19):

(Eq. (28)), through an equation similar to Eq. (19):

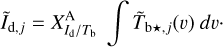

(33)

(33)

Superscript A in the conversion factor  refers to the gas tracer ( Hi or CO) associated with component j. As a reminder, the best-fit value of

refers to the gas tracer ( Hi or CO) associated with component j. As a reminder, the best-fit value of  and the attendant uncertainty,

and the attendant uncertainty,  , are determined as explained in Sect. 2.2.

, are determined as explained in Sect. 2.2.

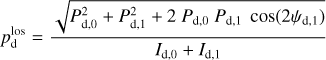

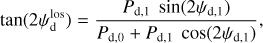

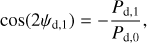

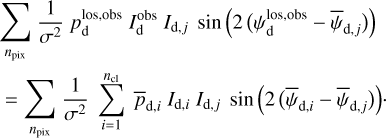

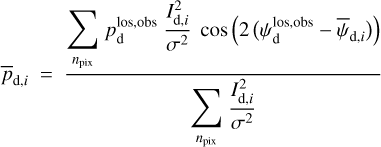

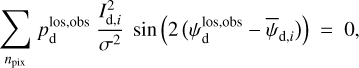

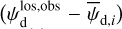

2.4 Derivation of the magnetic field orientation in each cloud

At this point, we have identified ncl clouds along the LoS, and we have derived their contributions Id,i (Eqs. (32) and (33)) to the dust intensity,  (Eq. (24)). We now turn to their contributions Qd,i and Ud,i to the two Stokes parameters for linear polarization,

(Eq. (24)). We now turn to their contributions Qd,i and Ud,i to the two Stokes parameters for linear polarization,  and

and  (Eqs. (25) and (26)). As mentioned below Eq. (26), Id,i, Qd,i, and Ud,i have the same expressions as Id, Qd, and Ud (Eqs. (1), (2), and (3)), respectively, with the LoS integral reduced to the path length through cloud i, Li. By analogy with Eqs. (10)–(14), we can then directly write

(Eqs. (25) and (26)). As mentioned below Eq. (26), Id,i, Qd,i, and Ud,i have the same expressions as Id, Qd, and Ud (Eqs. (1), (2), and (3)), respectively, with the LoS integral reduced to the path length through cloud i, Li. By analogy with Eqs. (10)–(14), we can then directly write

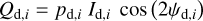

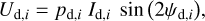

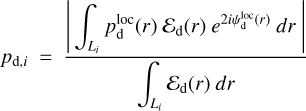

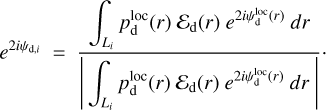

(34)

and

(34)

and

(35)

with

(35)

with

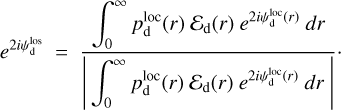

(36)

and

(36)

and

(37)

(37)

The physical meaning of pd,i and ψd,i for cloud i is similar to that of  and

and  given below Eq. (14) for the entire LoS.

given below Eq. (14) for the entire LoS.

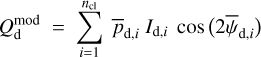

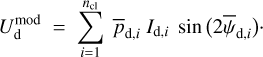

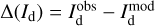

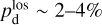

To proceed, we consider that pd,i and ψd,i are uniform across the PoS surface of cloud i, in contrast to Id,i, which generally varies. Strictly speaking, this is unlikely to be correct, as magnetic field lines have probably been distorted by internal motions. However, we are a priori entitled to take this approach if we are only interested in dust-weighted average values of pd,i and ψd,i at the cloud scale, which we denote with an overscore4. Thus, the pair of equations we work here with is obtained by inserting Eqs. (34) and (35), with pd,i and ψd,i overscored, into Eqs. (25) and (26):

(38)

and

(38)

and

(39)

(39)

In the above equations, the dust intensity of cloud i, Id,i, was derived in Sect. 2.3 (Eqs. (32) and (33)), while its average polarization fraction and angle,  and

and  , are treated as free parameters. This leaves us with two free parameters per cloud and hence a total of 2ncl free parameters.

, are treated as free parameters. This leaves us with two free parameters per cloud and hence a total of 2ncl free parameters.

The best-fit values of  and

and  are the values that minimize

are the values that minimize

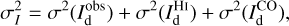

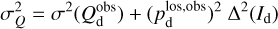

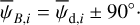

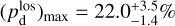

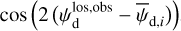

![$\chi _{\rm{r}}^2 = {1 \over {\left( {{n_{{\rm{dat}}}} - {n_{{\rm{par}}}}} \right)}}\mathop \sum \limits_{{n_{pix}}} \left[ {{{{{\left( {Q_{\rm{d}}^{{\rm{obs}}} - Q_{\rm{d}}^{\bmod }} \right)}^2}} \over {\sigma _Q^2}} + {{{{\left( {U_{\rm{d}}^{{\rm{obs}}} - U_{\rm{d}}^{\bmod }} \right)}^2}} \over {\sigma _U^2}}} \right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa51034-24/aa51034-24-eq121.png) (40)

where

(40)

where  and

and  are the observed Stokes parameters,

are the observed Stokes parameters,  and

and  are the modeled Stokes parameters given by Eqs. (38) and (39), respectively, σQ and σU are the total “observational uncertainties” associated with Qd and Ud, respectively, ndat = 2 npix is the total number of data points, npar = 2 ncl is the number of free parameters, and the sum runs over the npix pixels. The total “observational uncertainties” are the quadratic sums of the measurement errors in the observed Stokes parameters,

are the modeled Stokes parameters given by Eqs. (38) and (39), respectively, σQ and σU are the total “observational uncertainties” associated with Qd and Ud, respectively, ndat = 2 npix is the total number of data points, npar = 2 ncl is the number of free parameters, and the sum runs over the npix pixels. The total “observational uncertainties” are the quadratic sums of the measurement errors in the observed Stokes parameters,  and

and  , and the “decomposition errors” in the modeled Stokes parameters arising from decomposition errors in the modeled cloud intensities, Id,i. The contributions from the different clouds cannot be derived separately, but we may reasonably consider that the “decomposition errors” in

, and the “decomposition errors” in the modeled Stokes parameters arising from decomposition errors in the modeled cloud intensities, Id,i. The contributions from the different clouds cannot be derived separately, but we may reasonably consider that the “decomposition errors” in  and

and  are both equal to the error in the modeled intensity,

are both equal to the error in the modeled intensity,  , times the observed LoS-averaged polarization fraction,

, times the observed LoS-averaged polarization fraction,  . We may further approximate the error in

. We may further approximate the error in  by the residual

by the residual  . Altogether, we have

. Altogether, we have

(41)

and

(41)

and

(42)

(42)

Minimization of  is performed through MCMC simulations, leading to the best-fit values of

is performed through MCMC simulations, leading to the best-fit values of  and

and  , together with the attendant uncertainties,

, together with the attendant uncertainties,  and

and  .

.

Once the polarization fraction,  , and the polarization angle,

, and the polarization angle,  , of cloud i have been determined, it is possible to estimate the orientation of its internal magnetic field, Bi. Here, too, we are referring to dust-weighted average values, denoted with an overscore. The orientation angle of

, of cloud i have been determined, it is possible to estimate the orientation of its internal magnetic field, Bi. Here, too, we are referring to dust-weighted average values, denoted with an overscore. The orientation angle of  in the PoS,

in the PoS,  , can be directly inferred from the polarization angle,

, can be directly inferred from the polarization angle,  , with the help of Eq. (7) applied to cloud i:

, with the help of Eq. (7) applied to cloud i:

(43)

(43)

The inclination angle of  to the PoS,

to the PoS,  , can in principle be inferred from the polarization fraction,

, can in principle be inferred from the polarization fraction,  , using Eq. (6) applied to cloud i,

, using Eq. (6) applied to cloud i,

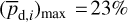

(44)

together with an adopted value of the maximum polarization fraction averaged at the cloud scale,

(44)

together with an adopted value of the maximum polarization fraction averaged at the cloud scale,  . Following Planck Collaboration (2015a), we could, for instance, take

. Following Planck Collaboration (2015a), we could, for instance, take  (see Appendix B). Because of the uncertainty in

(see Appendix B). Because of the uncertainty in  , the derived value of

, the derived value of  is much less reliable than the derived value of

is much less reliable than the derived value of  . Moreover, the existence of two opposite-signed solutions for

. Moreover, the existence of two opposite-signed solutions for  implies that the orientation of

implies that the orientation of  can only be determined with a mirror ambiguity with respect to the PoS. Zee-man observations, which are sensitive to B∥, would be needed to set the sign of

can only be determined with a mirror ambiguity with respect to the PoS. Zee-man observations, which are sensitive to B∥, would be needed to set the sign of  for the dominant cloud.

for the dominant cloud.

3 Application to the G139 region

To illustrate the method presented in Sect. 2, we now apply it to a small region of the sky encompassing the Herschel G139 field, which is one of the 116 Galactic fields observed with Herschel as part of the Herschel Galactic cold core (GCC) key-program (Juvela et al. 2010, 2012). This small region, which we refer to as the G139 region, is a 104′ × 104′ square centered on (l, b) = (139°30′, −3°16′). The Herschel maps reveal a long filamentary structure with signs of star formation activity, including a number of embedded cores and young stellar object candidates (Montillaud et al. 2015). This filamentary structure is surrounded by a more diffuse and extended emission.

In Sect. 3.1, we present the relevant available data. In Sect. 3.2, we derive the conversion factors from gas tracers to dust emission. In Sect. 3.3, we decompose the measured intensity of the dust emission into the contributions from seven separate clouds along the LoS. In Sect. 3.4, we derive the magnetic field orientation in each cloud. In Sect. 3.5, we examine alternative configurations of clouds, involving an increasing number of clouds. The input maps of the G139 region used in our study are listed in Table 1, along with their angular resolution, δθ, and (when relevant) their spectral resolution, δv, and their spectral extent, ∆v.

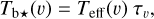

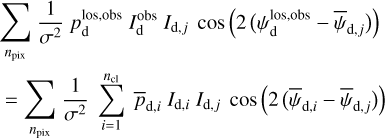

3.1 Available data for G139

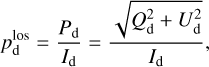

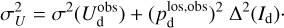

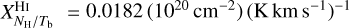

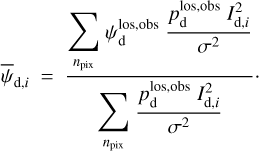

The polarization information needed to infer the magnetic field orientations toward G139 can be extracted from the all-sky maps of the polarized dust emission measured by Planck at 353 GHz (Planck Collaboration 2015b, 2020b). The three panels in the top row of Fig. 1 show the maps of the intensity, Id (Eq. (1)), and of the two Stokes parameters for linear polarization, Qd (Eq. (2)) and Ud (Eq. (3)), of the 353 GHz dust emission toward G139.

The kinematic information needed to separate the different clouds along the LoS is provided by the spectral cubes of the brightness temperature, Tb, of the three gas tracers introduced in Sect. 2.2, namely, the Hi 21 cm, 12CO 2.6 mm, and 13CO 2.7 mm emission lines. Here, we resort to the following cubes: the Hi cube from the Effelsberg-Bonn Hi Survey (EBHIS) of the whole northern sky, with δ ≥ −5° (Winkel et al. 2016), and the 12CO and 13CO cubes from the Milky Way Imaging Scroll Painting (MWISP) survey of the Galactic plane, with 10° ≤ l ≤ +250° and |b| ≲ 5.2° (Su et al. 2019; Yuan et al. 2021, 2022). The corresponding maps of the velocity-integrated Tb toward G139 are displayed in the three panels of the top row of Fig. 2. We see that Hi (left panel) is quite uniformly distributed, with a weak northward gradient, while 12CO (middle panel) and 13CO (right panel) have more structured distributions, with a prominent peak at the position of the bright core in the dust intensity map (top-left panel of Fig. 1). Interestingly, the 12CO peak does not stand out as prominently as the 13CO peak, which is most likely because 12CO emission from the underlying emitting region is optically very thick.

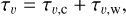

Following the procedure explained in detail in Appendix A, we correct Tb for opacity saturation, thereby obtaining an opacity-corrected brightness temperature, Tb⋆. For HI, we derive  using Eq. (A.5) with T = 80 K. For CO, we derive two complementary estimates of

using Eq. (A.5) with T = 80 K. For CO, we derive two complementary estimates of  assuming

assuming  based on the 12CO cube (Eq. (A.18)) and

based on the 12CO cube (Eq. (A.18)) and  based on the rescaled 13CO cube (Eq. (A.19)); we then combine

based on the rescaled 13CO cube (Eq. (A.19)); we then combine  and

and  to obtain a best-estimate

to obtain a best-estimate  (Eq. (A.29)), from now on referred to as

(Eq. (A.29)), from now on referred to as  . We find that

. We find that  is nearly equal to the estimate with the smaller uncertainty, which is

is nearly equal to the estimate with the smaller uncertainty, which is  away from the CO peak and

away from the CO peak and  toward the CO peak. This dichotomy results from the huge jump in the opacity correction to

toward the CO peak. This dichotomy results from the huge jump in the opacity correction to  toward the CO peak, which renders

toward the CO peak, which renders  extremely uncertain.

extremely uncertain.

The maps of the velocity-integrated  and

and  are displayed in the second row of Fig. 2. The opacity-corrected Hi map (left panel) is similar to, but more contrasted than, its observed counterpart (left panel in the first row). It also differs by the emergence of a slight over-intensity along the lower-left boundary, which probably indicates the presence of a small, HI-bright cloud. The opacity-corrected 12CO and 13CO maps (not shown) are quite similar, except toward the CO peak, where only

are displayed in the second row of Fig. 2. The opacity-corrected Hi map (left panel) is similar to, but more contrasted than, its observed counterpart (left panel in the first row). It also differs by the emergence of a slight over-intensity along the lower-left boundary, which probably indicates the presence of a small, HI-bright cloud. The opacity-corrected 12CO and 13CO maps (not shown) are quite similar, except toward the CO peak, where only  is reliable. Altogether, the combined opacity-corrected CO map (right panel in the second row) is very close to the opacity-corrected 12CO map, with only the CO peak taken from the rescaled opacity-corrected 13CO map.

is reliable. Altogether, the combined opacity-corrected CO map (right panel in the second row) is very close to the opacity-corrected 12CO map, with only the CO peak taken from the rescaled opacity-corrected 13CO map.

Before jointly exploiting the  and

and  spectral cubes, we bring them to common angular and spectral resolutions and to a common (l, b, v) grid. We also bring the Planck maps of Id, Qd, and Ud to the common angular resolution and common (l, b) grid. Since the Hi cube has the lowest angular resolution (see Table 1), we adopt its angular resolution, δθ = 10.8′, together with a pixel size at the (rounded) Nyquist limit, δθpix = 4′. Accordingly, the (l, b) grid needed to cover our 104′ × 104′ G139 region possesses 26 × 26 pixels. Clearly, this grid undersamples the CO and dust maps. Along the v-axis, we retain a total velocity range [−120, +20] km s−1, which is broad enough to encompass all the true emission from Hi and CO, and we adopt a spectral resolution δv = 0.3 km s−1, which is much finer than the spectral resolution of the Hi cube and roughly twice the spectral resolution of the CO cube. This spectral oversampling of

spectral cubes, we bring them to common angular and spectral resolutions and to a common (l, b, v) grid. We also bring the Planck maps of Id, Qd, and Ud to the common angular resolution and common (l, b) grid. Since the Hi cube has the lowest angular resolution (see Table 1), we adopt its angular resolution, δθ = 10.8′, together with a pixel size at the (rounded) Nyquist limit, δθpix = 4′. Accordingly, the (l, b) grid needed to cover our 104′ × 104′ G139 region possesses 26 × 26 pixels. Clearly, this grid undersamples the CO and dust maps. Along the v-axis, we retain a total velocity range [−120, +20] km s−1, which is broad enough to encompass all the true emission from Hi and CO, and we adopt a spectral resolution δv = 0.3 km s−1, which is much finer than the spectral resolution of the Hi cube and roughly twice the spectral resolution of the CO cube. This spectral oversampling of  makes it easier to extract meaningful Gaussian kinematic components with ROHSA. The re-gridded maps of Id, Qd, and Ud and those of the velocity-integrated

makes it easier to extract meaningful Gaussian kinematic components with ROHSA. The re-gridded maps of Id, Qd, and Ud and those of the velocity-integrated  and

and  are displayed in the second row of Fig. 1 and the third row of Fig. 2, respectively.

are displayed in the second row of Fig. 1 and the third row of Fig. 2, respectively.

|

Fig. 1 Maps of the intensity, Id (left), and of the two Stokes parameters for linear polarization, Qd (middle) and Ud (right), of the polarized dust emission at 353 GHz toward the G139 region defined in the first paragraph of Sect. 3. Top row: observational maps from Planck (Planck Collaboration 2020b). Middle row: same maps resampled to the common 26 × 26 pixel grid of the gas tracers (pixel size = 4′). Bottom row: statistical uncertainties in the Planck maps resampled to the 26 × 26 pixel grid. The total uncertainties are equal to the quadratic sums of the statistical uncertainties and the photometric calibration uncertainties, which in turn are given by 0.0078 Id for Id(Planck Collaboration 2016b, 2020b) and 0.015 Pd for Qd and Ud (Planck Collaboration 2020b,c). |

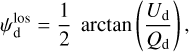

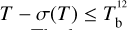

3.2 Derivation of the conversion factors

For each gas tracer A (A = Hi or CO), we need to determine the conversion factor from velocity-integrated opacity-corrected brightness temperature to dust intensity at 353 GHz,  (see Eq. (19)). As explained in Sect. 2.2, the best-fit values of

(see Eq. (19)). As explained in Sect. 2.2, the best-fit values of  and

and  , together with their uncertainties, are obtained by minimizing

, together with their uncertainties, are obtained by minimizing  in Eq. (21) through bootstrap sampling + MCMC simulations.

in Eq. (21) through bootstrap sampling + MCMC simulations.

We find that the best fit has χr = 1.63. This small value of χr indicates that our model is globally satisfactory, in the sense that the errors in the reconstruction of the dust intensity with Eq. (20) are only slightly larger than the total observational uncertainty, σI (Eq. (22)). The latter is dominated by  , which generally exceeds

, which generally exceeds  and

and  by a factor ∼2–10, except toward the CO peak, where

by a factor ∼2–10, except toward the CO peak, where  . The dominant contribution to

. The dominant contribution to  , in turn, comes by far from the uncertainty in the spin temperature of Hi (see second term in the r.h.s. of Eq. (A.13)), while the dominant contribution to

, in turn, comes by far from the uncertainty in the spin temperature of Hi (see second term in the r.h.s. of Eq. (A.13)), while the dominant contribution to  comes from measurement errors (see first terms in the r.h.s. of Eqs. (A.20) and (A.21)).

comes from measurement errors (see first terms in the r.h.s. of Eqs. (A.20) and (A.21)).

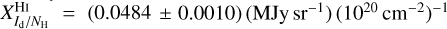

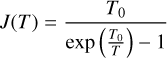

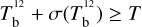

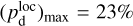

Displayed in Fig. 3 is a corner plot of the marginal and joint probability density functions of  and

and  . Their best-fit values and standard deviations, written above the corresponding 1D histograms (upper-left and lower-right panels), are

. Their best-fit values and standard deviations, written above the corresponding 1D histograms (upper-left and lower-right panels), are  and

and  , respectively. The shape of the joint distribution (lower-left panel) indicates that

, respectively. The shape of the joint distribution (lower-left panel) indicates that  and

and  are strongly anticorrelated. This result can be explained by the fact that Hi and CO both have widespread spatial distributions, with significant overlap (see third row of Fig. 2), such that an increase in the dust emission associated with one tracer must be accompanied by a decrease in the dust emission associated with the other tracer.

are strongly anticorrelated. This result can be explained by the fact that Hi and CO both have widespread spatial distributions, with significant overlap (see third row of Fig. 2), such that an increase in the dust emission associated with one tracer must be accompanied by a decrease in the dust emission associated with the other tracer.

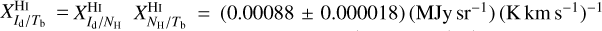

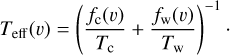

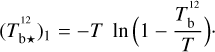

The best-fit values of the conversion factors enable us to rescale the Hi and CO maps in the third row of Fig. 2 to dust intensity at 353 GHz and thus obtain the best-fit maps of  and

and  as well as the best-fit map of the reconstructed dust intensity,

as well as the best-fit map of the reconstructed dust intensity,  . The latter is displayed in the top-middle panel of Fig. 4, where it can be compared to the observational Planck map,

. The latter is displayed in the top-middle panel of Fig. 4, where it can be compared to the observational Planck map,  , in the left panel. Both maps look similar, and the bright regions in the Planck map are well reproduced. The Hi medium provides the general dust-emission background, including its northward gradient, while the CO medium is responsible for the bright core to the right and for the weaker dust enhancement that runs obliquely north of the southeast-northwest diagonal. Globally, the Hi and CO media account for 84.3% and 15.7%, respectively, of the dust emission from the G139 region.

, in the left panel. Both maps look similar, and the bright regions in the Planck map are well reproduced. The Hi medium provides the general dust-emission background, including its northward gradient, while the CO medium is responsible for the bright core to the right and for the weaker dust enhancement that runs obliquely north of the southeast-northwest diagonal. Globally, the Hi and CO media account for 84.3% and 15.7%, respectively, of the dust emission from the G139 region.

The map of the residuals, ![$\left[ {I_{\rm{d}}^{{\rm{obs}}} - \left( {I_{\rm{d}}^{{\rm{HI}}} + I_{\rm{d}}^{{\rm{CO}}}} \right)} \right]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2026/01/aa51034-24/aa51034-24-eq201.png) , is shown in the top-right panel of Fig. 4. The largest residuals are positive and arise on the northwest and southeast sides of the bright core (which itself is almost residual-free). These positive residuals result from the bright core being intrinsically more extended in the observational Planck map than in the opacity-corrected CO map. They possibly reveal the presence of so-called dark gas, namely, gas that is undetected in Hi and CO (e.g., Grenier et al. 2005; Planck Collaboration 2011b). Large positive and negative residuals also arise in the upper-left and lower-right corners, respectively, i.e., in two regions with little CO emission and where the northward gradient of the opacity-corrected Hi emission remains too shallow to reproduce the observed dust-emission gradient. The negative residual along the lower-left boundary coincides with the slight over-intensity appearing in the Hi map after opacity correction (see Sect. 3.1), which suggests that the Hi emission could have been over-corrected. Other residuals could also result from imperfect opacity corrections, following a poor estimation of the excitation temperature. Alternatively, residuals could indicate that dust emission does not exactly follow the gas distribution – in other words, that the conversion factors are not perfectly uniform.

, is shown in the top-right panel of Fig. 4. The largest residuals are positive and arise on the northwest and southeast sides of the bright core (which itself is almost residual-free). These positive residuals result from the bright core being intrinsically more extended in the observational Planck map than in the opacity-corrected CO map. They possibly reveal the presence of so-called dark gas, namely, gas that is undetected in Hi and CO (e.g., Grenier et al. 2005; Planck Collaboration 2011b). Large positive and negative residuals also arise in the upper-left and lower-right corners, respectively, i.e., in two regions with little CO emission and where the northward gradient of the opacity-corrected Hi emission remains too shallow to reproduce the observed dust-emission gradient. The negative residual along the lower-left boundary coincides with the slight over-intensity appearing in the Hi map after opacity correction (see Sect. 3.1), which suggests that the Hi emission could have been over-corrected. Other residuals could also result from imperfect opacity corrections, following a poor estimation of the excitation temperature. Alternatively, residuals could indicate that dust emission does not exactly follow the gas distribution – in other words, that the conversion factors are not perfectly uniform.

It would be interesting to compare our best-fit values of the conversion factors  and

and  to previous estimates, but we did not find such estimates in the literature. However, we found a number of estimates for the intermediate conversion factors

to previous estimates, but we did not find such estimates in the literature. However, we found a number of estimates for the intermediate conversion factors  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  defined in Sect. 2.2.

defined in Sect. 2.2.

Regarding HI, the value of the conversion factor from velocity-integrated brightness temperature to hydrogen column density is generally taken as  (from Wilson et al. 2013), which is strictly valid in the optically thin case. This value was used by HI4PI Collaboration (2016) and by Planck Collaboration (2011b,a), with, in the latter study, an opacity correction equivalent to that in our Eq. (A.5) with T = 80 K. The two Planck papers also discussed the value of the conversion factor from hydrogen column density to dust intensity at 353 GHz. Planck Collaboration (2011b) obtained

(from Wilson et al. 2013), which is strictly valid in the optically thin case. This value was used by HI4PI Collaboration (2016) and by Planck Collaboration (2011b,a), with, in the latter study, an opacity correction equivalent to that in our Eq. (A.5) with T = 80 K. The two Planck papers also discussed the value of the conversion factor from hydrogen column density to dust intensity at 353 GHz. Planck Collaboration (2011b) obtained  in their reference region defined by |b| > 20° and NHI < 1.2×1021 cm−2, while Planck Collaboration (2011a) derived values in the range [0.021, 0.071] (MJy sr−1) (1020 cm−2)−1 for local (low-velocity) clouds toward 14 high-latitude fields covering ≃825 deg2 on the sky. Combining the above values of

in their reference region defined by |b| > 20° and NHI < 1.2×1021 cm−2, while Planck Collaboration (2011a) derived values in the range [0.021, 0.071] (MJy sr−1) (1020 cm−2)−1 for local (low-velocity) clouds toward 14 high-latitude fields covering ≃825 deg2 on the sky. Combining the above values of  and

and  gives for the conversion factor from velocity-integrated (opacity-corrected in the second case) brightness temperature to dust intensity at 353 GHz

gives for the conversion factor from velocity-integrated (opacity-corrected in the second case) brightness temperature to dust intensity at 353 GHz  and [0.00038, 0.00129] (MJy sr−1) (K km s−1)−1, respectively, where the uncertainties include only uncertainties in

and [0.00038, 0.00129] (MJy sr−1) (K km s−1)−1, respectively, where the uncertainties include only uncertainties in  , not uncertainties in

, not uncertainties in  associated with, for instance, opacity saturation. Both estimates are consistent. Our best-fit value,

associated with, for instance, opacity saturation. Both estimates are consistent. Our best-fit value,  , is slightly smaller than the value from Planck Collaboration (2011b), and it falls right within the range from Planck Collaboration (2011a).

, is slightly smaller than the value from Planck Collaboration (2011b), and it falls right within the range from Planck Collaboration (2011a).

Regarding CO, Remy et al. (2017) derived values of XCO and (τ353/N )CO H for six nearby molecular clouds between longitude l = 139° and 191° and between latitude b = −3° and −56°. Relying on 353 GHz dust emission data and on [0.4, 100] GeV γ-ray emission data, they obtained values of XCO in the range [0.86, 1.73] (1020 cm−2) (K km s−1)−1 and [0.36, 1.14] (1020 cm−2) (K km s−1)−1, respectively. They further obtained values of (τ353/NH)CO in the range [12.6, 44] (1027 cm−2)−1. Noting that  and Id = (4.76 × 104 MJy sr−1) τ353 for a dust temperature Td = 19.7 K (Planck Collaboration 2014), we find that the corresponding ranges of

and Id = (4.76 × 104 MJy sr−1) τ353 for a dust temperature Td = 19.7 K (Planck Collaboration 2014), we find that the corresponding ranges of  are [0 10, 0 73] (MJy sr− ) (K km s−1)−1 and [0.043, 0.48] (MJy sr−1) (K km s−1)−1, respectively. These ranges include no opacity correction for the CO line, which might explain why they are so broad. Our best-fit value,

are [0 10, 0 73] (MJy sr− ) (K km s−1)−1 and [0.043, 0.48] (MJy sr−1) (K km s−1)−1, respectively. These ranges include no opacity correction for the CO line, which might explain why they are so broad. Our best-fit value,  falls somewhat below the former range and within, though close to the lower end, of the latter range. Finding a lower value of

falls somewhat below the former range and within, though close to the lower end, of the latter range. Finding a lower value of  here is not surprising given that our opacity correction increases the brightness temperatures, and this increase must be offset by a decrease in the conversion factor.

here is not surprising given that our opacity correction increases the brightness temperatures, and this increase must be offset by a decrease in the conversion factor.

|

Fig. 2 Top row: observational maps of the velocity-integrated brightness temperatures, Tb, of the Hi 21 cm (left), 12CO 2.6 mm (middle), and 13CO 2.7 mm (right) emission lines toward the G139 region; these maps are from Winkel et al. (2016), Yuan et al. (2021), and Yuan et al. (2022), respectively. Second row: maps of the velocity-integrated opacity-corrected brightness temperatures, Tb⋆, of the Hi (left) and 12CO (right) lines, where |

|

Fig. 3 Corner plot of the marginal (1D) and joint (2D) probability density functions of the conversion factors from velocity-integrated opacity-corrected brightness temperature to dust intensity at 353 GHz, |

|

Fig. 4 Maps of the intensity, Id, of the dust emission at 353 GHz toward the G139 region. Left: observational map from Planck. Middle: best-fit maps reconstructed with the two gas tracers, Hi and CO, before (top) and after (bottom) application of the Gaussian decomposition algorithm ROHSA to each gas tracer. Right: maps of the residuals obtained by subtracting the respective reconstructed maps from the observational Planck map. The color code refers to the absolute residuals, whereas the contour lines follow the relative residuals. |

3.3 LoS decomposition into clouds

3.3.1 ROHSA decomposition

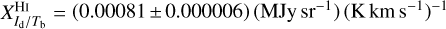

Next, we apply the Gaussian decomposition algorithm ROHSA (presented in Sect. 2.3) to the observed spectral cubes of the opacity-corrected brightness temperatures, Tb⋆, of our two gas tracers, Hi and CO, separately. The procedure yields 19 and 7 Gaussian kinematic components, respectively. The spectra of these components, averaged over the 26×26 pixels of the common (l, b) grid, are plotted in the top and bottom panels, respectively, of Fig. 5. For simplicity, the components of each tracer are ordered by increasing mean velocity. Also plotted in Fig. 5 are the total reconstructed  and

and  spectra, obtained by summing the averaged spectra of their respective kinematic components (black solid lines), as well as the corresponding observed spectra (black dashed lines).

spectra, obtained by summing the averaged spectra of their respective kinematic components (black solid lines), as well as the corresponding observed spectra (black dashed lines).

Comparing the reconstructed and observed spectra indicates that ROHSA does on average a very good job at reconstructing the observed spectra. Since we discarded the extracted components falling everywhere below twice the noise level, the reconstructed spectra are automatically free of the measurement noise apparent in the observational 12CO and 13CO cubes.

The Hi Gaussian decomposition (top panel of Fig. 5) results in 19 components, which peak at various velocities between ≃ −90 and +2 km s−1 and which, together, cover almost the entire velocity range [−120, +20] km s−1. The Hi spectrum is dominated by a cluster of 15 components ( Hi [5] - Hi [19]) peaking between ≃ −15 and +2 km s−1. Also prominent in the Hi spectrum is a strong and broad component ( Hi [2]) centered at v ≃ −40 km s−1.

The CO decomposition (bottom panel of Fig. 5) leads to 7 components peaking between ≃ −32 and 0 km s−1. The four dominant components (CO [3] - CO [6]) are clustered around v ∼ −10 km s−1, with peak velocities between ≃−16 and 0 km s−1; each of these components could easily be related to one of the 15 clustered Hi components. The CO spectrum also contains a very weak component (CO [7]) centered at v ≃ 0 km s−1 as well as two very close components (CO [1] and CO [2]) centered at v ≃ −32 km s−1. The latter probably form a single physical entity, which was artificially split by the sharp transition between our two estimates of  ; they will naturally be recombined at the cloud-reconstruction step. All the CO components are narrower than the Hi components.

; they will naturally be recombined at the cloud-reconstruction step. All the CO components are narrower than the Hi components.

The velocity-integrated maps of all the kinematic components of our two gas tracers are plotted in the top and bottom parts, respectively, of Fig. 6, along with the total reconstructed maps of both tracers (leftmost column), obtained by superposing their respective kinematic components. The brightest Hi component is clearly Hi [2], which, we noted earlier, is also prominent in the average Hi spectrum (top panel of Fig. 5). The globally brightest CO component is CO [3], which leads to the highest peak in the average CO spectrum (bottom panel of Fig. 5). The locally brightest CO feature is the bright core to the right, which, we now see, can be attributed to the CO [1] - CO [2] pair at v ≃ −32 km s−1.

The total reconstructed maps of both gas tracers are also plotted in the fourth row of Fig. 2, where they can be compared to the corresponding re-gridded observational maps in the third row. The comparison confirms the generally very good quality of the ROHSA reconstruction, which we already noted when discussing the average spectra in Fig. 5. Furthermore, in the same way as the re-gridded observational maps of both gas tracers were rescaled (see last two sentences in caption of Fig. 2) and combined into a map of the 353 GHz dust intensity (top-middle panel of Fig. 4), their reconstructed ROHSA maps can be rescaled and combined into a reconstructed ROHSA map of the 353 GHz dust intensity (bottom-middle panel of Fig. 4). Here, too, the agreement with the pre-ROHSA dust intensity map is very good.

It is interesting to compare our Gaussian decomposition of the CO cube to previous decompositions. The G139 region is part of the 12CO cube constructed by Dame et al. (2001) from a composite CO survey of the entire Galactic plane with the CfA & Cerro Tololo 1.2 m telescopes. Straižys & Laugalys (2007) divided the G139 region of this cube into three layers with different RVs (as defined earlier by Digel et al. 1996): the Gould Belt layer, with v ≃ [−5, +10] km s−1, the Camelopardalis (Cam) OB1 association layer, with v ≃ [−20, −5] km s−1, and the Perseus arm, with v ≃ [−60, −30] km s−1. Using the Galactic rotation curve to convert RVs to distances, they estimated the distances to the clouds of the Gould Belt layer, the Cam OB1 layer, and the Perseus arm at d ≈ [150, 300] pc, [800, 900] pc, and [2, 3] kpc, respectively. Later, Montillaud et al. (2015) identified three kinematic components, with RVs v ≈ −34 km s−1, −16 km s−1, and −9 km s−1, in the same 12CO data from Dame et al. (2001) as those studied by Straižys & Laugalys (2007). The v ≈ − 34 km s−1 component clearly peaks at the position of the bright core in the dust intensity map (top-left panel of Fig. 1), the v ≈ −16 km s−1 component has a more extended and more diffuse emission, and the v ≈ −9 km s−1 component is fainter. Referring to the work of Straižys & Laugalys (2007), they concluded that the v ≈ −34 km s−1 component must be part of the Perseus arm, while the v ≈ −16 km s−1 and v ≈ −9 km s−1 components must belong to the Cam OB1 layer. In addition, their identification of the v ≈ −34 km s−1 component with the bright core led them to place the latter at a distance d = 2.5 ± 0.5 kpc. To make the link with our own study, the v ≈ −34 km s−1, −16 km s−1, and −9 km s−1 components of Montillaud et al. (2015) presumably correspond, in our decomposition, to the CO[1] - CO[2] pair (centered at v ≃ −32 km s−1) and to the two peaks formed by the clustered CO[3] - CO[6] components (at v ≃ −16 and −7 km s−1).

|

Fig. 5 Spectra of the opacity-corrected brightness temperatures, |

|

Fig. 6 Reconstructed maps of the opacity-corrected brightness temperatures, |

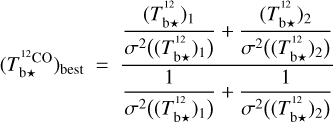

3.3.2 Cloud reconstruction

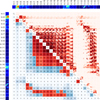

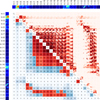

Moving on to the second step of the procedure described in Sect. 2.3, we examine the  Gaussian kinematic components identified with ROHSA and seek to group together, i.e., assign to a same cloud, those with similar velocity profiles. To that end, we consider every possible pair of components j and j′ (j ≠ j′), compute the correlation coefficient 𝒞jj′ (Eq. (29)) at each of the 26 × 26 pixels of our grid, retain the weighted average value of 𝒞jj′ over all the pixels, ⟨𝒞jj′⟩ (Eq. (30)), and compare ⟨𝒞jj′⟩ to the velocity-coherence threshold, 𝒞th, entering Eq. 31). Here, for the purpose of illustration, we adopt 𝒞th = 50%. The results obtained for this value of 𝒞th are presented in Sects. 3.3–3.4, while an overview of the results obtained for all the integer values of 𝒞th between 0 and 100% is provided in Sect. 3.5. When ⟨𝒞jj′ ⟩ ≥ 𝒞th, we combine components j and j′ and assign them to a same cloud. The results of our correlation analysis for the 325 possible pairs of components are reported in Fig. 7, with mini-maps of 𝒞jj′ displayed in the upper-right half and the derived values of ⟨𝒞jj′⟩ indicated in the lower-left half.

Gaussian kinematic components identified with ROHSA and seek to group together, i.e., assign to a same cloud, those with similar velocity profiles. To that end, we consider every possible pair of components j and j′ (j ≠ j′), compute the correlation coefficient 𝒞jj′ (Eq. (29)) at each of the 26 × 26 pixels of our grid, retain the weighted average value of 𝒞jj′ over all the pixels, ⟨𝒞jj′⟩ (Eq. (30)), and compare ⟨𝒞jj′⟩ to the velocity-coherence threshold, 𝒞th, entering Eq. 31). Here, for the purpose of illustration, we adopt 𝒞th = 50%. The results obtained for this value of 𝒞th are presented in Sects. 3.3–3.4, while an overview of the results obtained for all the integer values of 𝒞th between 0 and 100% is provided in Sect. 3.5. When ⟨𝒞jj′ ⟩ ≥ 𝒞th, we combine components j and j′ and assign them to a same cloud. The results of our correlation analysis for the 325 possible pairs of components are reported in Fig. 7, with mini-maps of 𝒞jj′ displayed in the upper-right half and the derived values of ⟨𝒞jj′⟩ indicated in the lower-left half.

It emerges from Fig. 7 that 83 pairs satisfy the condition ⟨ 𝒞jj′ ⟩ ≥ 𝒞th; for better visibility, the corresponding small squares in the lower-left half of the figure are shaded in red (with increasing level of red as ⟨𝒞jj′⟩ increases), as opposed to light blue for the other pairs. Amongst the pairs with ⟨𝒞jj′⟩ ≥ 𝒞th those having a component in common are further grouped together into a same multicomponent cloud. The end result is a set of seven clouds, which we name ℂ1, ℂ 2, ℂ 3, ℂ 4, ℂ 5, ℂ 6, and ℂ 7, and which enclose 1, 2, 1, 4, 15, 2, and 1 components, respectively. The different components of each cloud can be retrieved from the labels with the cloud’s name along the diagonal.

Using the best-fit values of the conversion factors derived in Sect. 3.2 (see Fig. 3), we can now rescale the Tb⋆ spectral cubes of all the kinematic components to dust emission at 353 GHz. This common dust scale enables us to combine the different components of each cloud and thus obtain its dust emission spectral cube. In the left part of Fig. 8, we plot the dust emission spectra of the seven clouds, averaged over the 26×26 pixels (black solid lines), together with the spectra of their individual components (color lines). The dust intensity maps of the seven clouds are displayed in the right column.

ℂ1, ℂ 2, and ℂ3 are three purely atomic clouds, containing 1, 2, and 1 Hi components, respectively. ℂ1 is faint, with an enhancement in the southwest corner; ℂ2 is much brighter, especially in the northwest part; ℂ3 is faint, knotty, and mostly confined to the northeast corner. ℂ1 and ℂ2 both cover a rather broad velocity range, which could perhaps indicate that they are quite extended along the LoS.

ℂ4 and ℂ5 are two mixed atomic-molecular clouds. ℂ4 encloses an oblique, elongated CO structure (2 CO components), partially surrounded by an extended Hi envelope (2 Hi components). ℂ5 is the richest cloud, with 13 Hi and 2 CO components, which together fill the entire region. In both clouds, Hi appears to surround CO in velocity.

ℂ6 and ℂ7 are two purely molecular clouds, with two very close CO components for ℂ6 and a single CO component for ℂ7. ℂ6 is bright and localized both in the sky and in velocity; it clearly corresponds to the bright core in the observational dust intensity map (top-left panel of Fig. 1). ℂ7 is much fainter, confined to the northeast corner, and also localized in velocity.