| Issue |

A&A

Volume 705, January 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A191 | |

| Number of page(s) | 30 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202554956 | |

| Published online | 20 January 2026 | |

Validating a non-local stellar convection model with 3D hydrodynamics simulations

1

Heidelberger Institut für Theoretische Studien Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg 35 69118 Heidelberg, Germany

2

Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 1 85748 Garching, Germany

3

Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Astronomisches Rechen-Institut Mönchhofstr. 12–14 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

4

Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Institut für Theoretische Astrophysik Philosophenweg 12 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

1

April

2025

Accepted:

3

October

2025

Context. The efficient transport of energy and chemical elements by convective motions has a profound effect on the structure and evolution of stars. These motions occur on the relatively short dynamical timescale of convection and are intrinsically multi-dimensional. Stellar models usually rely on the one-dimensional mixing-length approximation of these processes, which is known to break down at convective boundaries. The Kuhfuß, R. (1987, Dissertation, Technische Universität München, München) convection model has been shown to handle convective boundaries in a more consistent way.

Aims. We test the assumptions that enter the Kuhfuß model using multi-dimensional hydrodynamics simulations, and we compare the results with existing one-dimensional models. Where possible, we also aim to calibrate the parameters of the Kuhfuß model using the simulations.

Methods. We computed one-dimensional stellar models employing the Kuhfuß model of a 3 M⊙ main-sequence star. These models were compared to three-dimensional hydrodynamic simulations obtained with the code called SEVEN-LEAGUE HYDRO and using the Reynolds-averaged Navier Stokes analysis. We analysed the global convective variables and individual contributions to the equations of the convection model.

Results. The turbulent kinetic energy as predicted by the Kuhfuß model agrees well with the simulation results. Towards the boundary of the convective core, the simulations show a layer of a positive entropy gradient that coincides with a positive convective flux, as predicted by the convection model. The terms involving pressure fluctuations are found to have a non-negligible magnitude.

Conclusions. The agreement of the turbulent kinetic energy equation for the convection model and the simulation is an important sign that the convection model is physically accurate. The gradient of the mean entropy that we found in the multi-dimensional simulations and in the Kuhfuß model confirms the existence of a Deardorff layer, that is, of a layer with a subadiabtic temperature stratification and positive convective flux. This is not predicted by the mixing-length theory. The assumption that turbulence is isotropic and that pressure fluctuations are negligible needs to be revisited in the convection model.

Key words: convection / hydrodynamics / stars: evolution / stars: interiors

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1. Introduction

Although the assumption of hydrostatic equilibrium is mostly justified, the interiors of stars are inherently dynamic. They are subject to dynamic flows of gas driven by various physical processes. One of the most important contributions stems from convection, which is the transport of matter and energy by bulk fluid motions. The high transport efficiency of convection makes it a crucial ingredient in stellar structure and evolution models because convective layers have a nearly homogeneous composition, and deep convective layers are also nearly adiabatically stratified. In main-sequence stars, in which the nuclear burning is dominated by the CNO cycle, the energy transport in the core becomes convective. The extent of these convectively mixed cores has a direct effect on the luminosity, the chemical yield, and the lifetime of these stars as well as the final fate of the stars as supernovae and potential mergers of the stellar remnants.

The convection in stellar cores is an inherently multi-dimensional turbulent process. The governing equations are too complex for an analytical treatment, and we therefore have to resort to numerical solutions (e.g. Lecoanet & Edelmann 2023). This makes three-dimensional (3D) hydrodynamic simulations a powerful tool for studying stellar convection. These simulations solve the equations of gas dynamics numerically. As a result, the simulations provide us with a time series of hydrodynamic variables such as the velocity field, the mass density, or the specific energy density of the fluid in three spatial dimensions. Compared to other theoretical descriptions of hydrodynamics, 3D simulations apply a limited set of assumptions and approximations. For example, Lecoanet & Edelmann (2023) point out that kinetic energy spectra and average velocities agree well in different simulations. Therefore, 3D simulation results are considered as a rather accurate representation of the physical reality.

Numerical simulations of core convection still include a number of challenges (we refer to Lecoanet & Edelmann 2023 for a review of current simulations of core convection and its limitations; further limitations of core-convection simulations in the context of asteroseismic observations of F- and B-type stars were discussed by Aerts et al. 2021). Some of the main challenges are the long thermal timescale in contrast to the short convective timescale, the effects of rotation and magnetism, and the mixing of chemical elements by waves. Even though we model core convection here, we would like to point out that major challenges have been encountered in modelling convection in the Sun. This circumstance is known as the convective conundrum (e.g. Hanasoge et al. 2012; O’Mara et al. 2016). Currently, rotation and magnetism seem to play major roles in reconciling solar observations and simulations (Käpylä 2024, and references therin), while the helioseismic observations are also actively debated (Birch et al. 2024).

The construction of grids of 3D models that cover the whole range of parameters in stellar convection (stellar mass, age, composition, stratification, etc.) is prohibited by the enormous computing time needed. This necessitates an efficient model that accurately captures the physics of convection without relying on expensive 3D calculations. The first step towards building such a model and testing its accuracy is to compare the convection model to self-consistent 3D simulations. To analyse the 3D simulations and compare them to one-dimensional (1D) stellar models, we used the Reynolds-averaged Navier Stokes (RANS) analysis (e.g. Viallet et al. 2013; Arnett et al. 2015). The RANS equations are based on the so-called Reynolds splitting (Reynolds 1894),

which splits the hydrodynamic variables such as the density ρ or velocities u into a mean part and a fluctuating part, which are denoted with the overbar and with the prime, respectively. Inserting the Reynolds splitting into the hydrodynamic equations allows us to construct the dynamic equations of the fluctuating quantities and higher-order combinations thereof. While the evolution equations of correlation functions of a given order are analytically exact, they cannot be solved self-consistently because correlations of an even higher order always arise from the non-linearity of the Navier-Stokes equation. So-called closure relations are therefore necessary to approximate these and other terms that are not described within the model to obtain a closed system of equations.

In contrast to 3D simulations, stellar structure and evolution models employ various assumptions and approximations, the most prominent being spherical symmetry. Hence, the hydrodynamic flows also need to be described in one spatial dimension. To compute accurate stellar models, it is crucial to ensure that the 1D models capture the most relevant aspects of the hydrodynamic flows. For decades, the most commonly used scheme to describe convection in stellar models has been the mixing-length theory (MLT) (Prandtl 1925; Biermann 1932; Böhm-Vitense 1958). Despite its simplicity as a local and time-independent theory, MLT has described stellar structure and evolution with great success. Evidence has accumulated in recent years, however, that MLT systematically underestimates the size of convective regions from an observational (Maeder & Mermilliod 1981; Bressan et al. 1981; Pietrinferni et al. 2004; Magic et al. 2010; Claret & Torres 2019; Mombarg et al. 2019; Pedersen et al. 2021; Deheuvels et al. 2016; Angelou et al. 2020) and a theoretical side (Roxburgh 1978, 1992; Zahn 1991; Meakin & Arnett 2007; Käpylä 2019; Higl et al. 2021; Anders et al. 2022; Andrassy et al. 2024). This has profound implications for the stellar structure and evolution modelling because the size of convective regions affects for example the properties of convective cores (Moravveji et al. 2015; Pedersen et al. 2021), the lithium abundance of the Sun and Sun-like stars (Carlos et al. 2019; Pinsonneault 1997; Dumont et al. 2021), the location of the base of the solar convection zone (Basu & Antia 2004; Christensen-Dalsgaard et al. 2011; Asplund et al. 2021; Braun et al. 2024), the location of the red giant branch bump (Alongi et al. 1991; Khan et al. 2018), and supernova explosions (Schneider et al. 2023; Heger et al. 2023; Temaj et al. 2024).

These shortcomings led to the introduction of convective overshooting to allow for chemical mixing, and in some descriptions, to also allow for a modified thermal stratification beyond the formal MLT boundaries in stellar models. So far, different approaches have been taken to introduce this convective overshooting in the stellar models, for example by simply extending the convectively mixed region by a fraction of the pressure scale height, by introducing an exponentially decreasing diffusion coefficient at convective boundaries (e.g. Freytag et al. 1996), or by increasing the size of mixed regions through convective entrainment (Turner 1986; Meakin & Arnett 2007). While these approaches are parametrised solutions to the problem, so-called turbulent convection models (TCMs) serve as an alternative description of convection to overcome the fundamental shortcomings of the MLT (Stellingwerf 1982; Kuhfuß 1987; Canuto 1992; Xiong et al. 1997; Canuto & Dubovikov 1998; Li & Yang 2001). Starting from the RANS equations and supplying the necessary closure relations, these models allow for time-dependent convective variables and introduce non-local terms that lead to convective regions extending beyond the formal MLT boundaries defined by a stability criterion.

We compare results from 1D stellar models including the Kuhfuß convection theory (Kuhfuß 1987) to the 3D simulations by constructing the convective variables and the individual equation terms from the 3D data using the RANS analysis. The original Kuhfuß (1987) model has recently been extended by Kupka et al. (2022) and Ahlborn et al. (2022) (K22 and A22 in the following) to include the dissipation by buoyancy waves at convective core boundaries. In this work, we use the version described by K22 and A22. We compare the Kuhfuß model in different ways to the hydrodynamic simulations. The first and simplest comparison is to directly compare the convective variables obtained from the stellar model and as extracted from the hydrodynamic simulations. Here, the turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) and the convective flux are most relevant for stellar structure and evolution because they determine the extent and thermal stratification of convective regions. With this approach, we test how well the stellar models represent the results obtained from the hydrodynamic simulations.

This comparison only shows global discrepancies, however, and does not indicate their physical origin. To study the causes for potential discrepancies of the convective variables in the 1D and 3D data, we compare the individual terms of the RANS equations computed in the simulations and stellar models (see Sects. 2 and 5). These terms can be directly compared to their 1D counterparts, obtained from the TCM, which again allows us to assess the overall physical accuracy of the TCM. Finally, the RANS analysis of 3D simulation data can be used to interpret the results of the simulation, as discussed by Viallet et al. (2013), Arnett et al. (2015), Mocák et al. (2018) or Horst et al. (2021). The comparison of the results of hydrodynamic simulations with the TCM in a stellar model is therefore a powerful way to identify shortcomings of the convection model and understand turbulent convection in stars in general (Grossman 1996; Cai 2020; Arnett et al. 2015; Kupka & Muthsam 2007a,b,c; Snellman et al. 2015).

With this comparison, we determine whether the Kuhfuß model in our current version is an acceptable model to describe convection in stars and if it describes the overshooting zone correctly. In A22 we discuss the agreement between the Kuhfuß model and other 1D descriptions of convective overshooting and observations. An early analysis of the 3D simulations presented in this work can be found in Ahlborn (2022). In Sect. 2 we describe the relevant RANS equations and the TCM by Kuhfuß (1987) and K22 in more detail. In Sect. 3 we describe the simulation code we used and the numerical setup of the simulations. In Sect. 4 we compare the convective variables to their representations computed from the 3D simulations. Subsequently, we compute the terms of the relevant RANS equations and compare them to their counterparts computed in the Kuhfuß model (Sect. 5). Based on the individual terms of the Kuhfuß model computed from the hydrodynamic simulations, we discuss how varying the model parameters might improve the agreement between the model and the simulations in Sect. 6. Because of the theoretical and numerical uncertainties of the hydrodynamic simulations, this analysis can be only carried out in the theoretical limits of the simulations we used (we refer to Sects. 3 and 7).

2. The Kuhfuß (1987) TCM

We used the TCM derived by Kuhfuß (1987) in the implementation described in K22 and A22 (we also refer to Flaskamp 2003). For the sake of completeness, we repeat the most important aspects of the model in this section. As most TCMs, the model of Kuhfuß (1987) is based on the Reynolds splitting (see Eq. (1)), where the fluctuating part refers to the turbulent contribution of the flow. For stellar structure and evolution models, higher-order combinations of these fluctuating parts are of particular interest. The Kuhfuß model features three convective variables that are second-order correlations of fluctuating quantities,

where s′ refers to the fluctuations of the specific entropy. Here and throughout the rest of the paper, the overbar denotes a volume-weighted Reynolds average in contrast to a mass weighted Favre average. In the following, we refer to ω as the TKE, to Π = Πr (the radial component of the convective flux vector) as the convective flux variable and to Φ as the entropy fluctuation variable. By computing the higher-order correlation functions ω, Π and Φ, the Kuhfuß (1987) equations describe bulk properties of the flow in a statistical way. In the following we first describe how to derive the RANS equations by applying the Reynolds splitting to the Navier Stokes (Eq. A.1) and the energy conservation Equation (A.3). Subsequently, we describe the final equations of the Kuhfuß (1987) TCM. The resulting equations are also used to analyse the 3D simulation results.

2.1. The RANS equations

Given the dynamic equations of the fluctuating quantities u′ and s′ (Eqs. (A.2) and (A.4)), the dynamic equations for the second-order moments Eqs. (2)–(4) are derived using the product rule:  and similarly for the other second-order correlation functions where

and similarly for the other second-order correlation functions where  . In the following, we give all the terms of the RANS equations and identify their physical meaning next to the term (e.g. Kuhfuß 1987),

. In the following, we give all the terms of the RANS equations and identify their physical meaning next to the term (e.g. Kuhfuß 1987),

where σ is the viscosity tensor and p denotes the pressure. The notion buoyancy term is motivated by the expansion of  in terms of density fluctuations. In the Kuhfuß model the density fluctuations are further expanded in terms of entropy fluctuations to arrive at the convective flux variable Π (see also Kuhfuß 1987; Ahlborn 2022). Here, we have also rewritten

in terms of density fluctuations. In the Kuhfuß model the density fluctuations are further expanded in terms of entropy fluctuations to arrive at the convective flux variable Π (see also Kuhfuß 1987; Ahlborn 2022). Here, we have also rewritten  using the assumption of hydrostatic equilibrium, where g denotes the gravitational acceleration vector.

using the assumption of hydrostatic equilibrium, where g denotes the gravitational acceleration vector.

Similar to the equation for the TKE, the evolution equation for the convective flux variable can be derived as

where  refers to the ith unit vector. Here, we denote the radiative flux with q, the temperature with T and the specific energy generation rate with ε.

refers to the ith unit vector. Here, we denote the radiative flux with q, the temperature with T and the specific energy generation rate with ε.

Finally, the evolution equation for the entropy fluctuations is given as

The RANS formalism as such is analytically exact. Provided all the data were available, all the terms in the RANS formalism can be evaluated. However, when turning the question around and attempting to use the RANS equations to predict the behaviour of correlation functions relevant for stellar evolution, some terms cannot be computed self-consistently within the theory. As can be seen, the resulting equations for the second-order moments ω, Π and Φ contain a term that is already of third order: The first term on the right-hand side, referred to as the non-local flux, is a third-order moment in the fluctuating quantities. These terms of the next higher order appear as a result of the non-linearity of the Navier Stokes equation. As a consequence, a series of averaged moment equations up to infinite order would be needed to describe the complete problem. This is, of course, computationally infeasible. To compute these terms, approximations and models have to be applied, known as closure relations. Finding suitable closure relations is the task of turbulence theory, which we describe in the next subsection.

2.2. The 3-equation model

In the Kuhfuß model, it is assumed that there are no mean flows, that is  . Furthermore, the spatial distribution of the TKE is assumed to be isotropic. The buoyancy terms are modelled in the Boussinesq approximation and pressure fluctuations are neglected (i.e. p′ = 0). Additionally, molecular viscosity is neglected (σ = 0) in all terms except the viscous dissipation term in Eq. (5). As we discuss below, viscous dissipation is modelled implicitly as a Kolmogorov cascade. This last point also implies that our 3D simulation code solves the same set of equations that the Kuhfuß model tries to describe. For the details, we refer to the original work of Kuhfuß (1987) (a short summary may be found in Appendix A of K22). The final model equations of the 3-equation model read

. Furthermore, the spatial distribution of the TKE is assumed to be isotropic. The buoyancy terms are modelled in the Boussinesq approximation and pressure fluctuations are neglected (i.e. p′ = 0). Additionally, molecular viscosity is neglected (σ = 0) in all terms except the viscous dissipation term in Eq. (5). As we discuss below, viscous dissipation is modelled implicitly as a Kolmogorov cascade. This last point also implies that our 3D simulation code solves the same set of equations that the Kuhfuß model tries to describe. For the details, we refer to the original work of Kuhfuß (1987) (a short summary may be found in Appendix A of K22). The final model equations of the 3-equation model read

where ∇, ∇ad, and Hp refer to the dimensionless model and adiabatic temperature gradient and the pressure scale-height, respectively. With cp we refer to the specific heat capacity at constant pressure. The symbol Λ refers to the dissipation length, that is discussed further below, and CD is a model parameter (default value  ). The default parameter values are obtained by calibrating the local and time-independent Kuhfuß model to the MLT. The flux terms of the RANS equations are denoted as ℱa with a = ω, Π, Φ. In the Kuhfuß model, they are described with a down-gradient approximation (Daly & Harlow 1970; Launder & Reece 1975; Xiong 1978; Li & Yang 2007),

). The default parameter values are obtained by calibrating the local and time-independent Kuhfuß model to the MLT. The flux terms of the RANS equations are denoted as ℱa with a = ω, Π, Φ. In the Kuhfuß model, they are described with a down-gradient approximation (Daly & Harlow 1970; Launder & Reece 1975; Xiong 1978; Li & Yang 2007),

where αa are model parameters. We note, however, that there is no a priori argument for a specific value. Kuhfuß (1987) suggested a value of 0.25 for αω based on a ballistic overshooting picture and calibrated αΠ and αΦ to MLT in a local and stationary limit. In agreement with previous work (A22), we select the same value of αω, αΠ, αΦ = 0.3. The heat flux terms of Eqs. (6) and (7) are modelled using a dissipation timescale,

where γR is a model parameter (default value  ), σB refers to the Stefan-Boltzmann constant and κ denotes the Rosseland opacities. A detailed discussion of the model parameters in the 3-equation model may be found in Sect. 6.

), σB refers to the Stefan-Boltzmann constant and κ denotes the Rosseland opacities. A detailed discussion of the model parameters in the 3-equation model may be found in Sect. 6.

Using the convective flux from the convection model, we define the temperature gradient of the stellar model self-consistently from the energy conservation in the stellar model (e.g. Kippenhahn et al. 2012),

The dissipation length-scale Λ is defined according to

where

and

assuming an ideal gas to compute  . Here, c4 = c3/(c2cϵ) and c2 = 1.92, c3 = 0.3 are parameters (see Eq. (21) in K22 and Canuto & Dubovikov 1998) and α is the equivalent to the mixing length parameter in MLT. The parameter cϵ denotes the dissipation parameter of the convection model, that is cϵ = CD. For the details of the implementation of this dissipation length-scale, we refer to Sect. 2.3 of A22 (see also Wuchterl 1995).

. Here, c4 = c3/(c2cϵ) and c2 = 1.92, c3 = 0.3 are parameters (see Eq. (21) in K22 and Canuto & Dubovikov 1998) and α is the equivalent to the mixing length parameter in MLT. The parameter cϵ denotes the dissipation parameter of the convection model, that is cϵ = CD. For the details of the implementation of this dissipation length-scale, we refer to Sect. 2.3 of A22 (see also Wuchterl 1995).

The convective chemical mixing was modelled as a diffusive process. The diffusion coefficient is defined as

following Langer et al. (1985), with a parameter αs that is discussed further below.

2.3. The 1-equation model

The 3-equation model may be simplified to a 1-equation model by introducing an approximation for the convective flux variable. Following the description of the MLT (e.g. Biermann 1932; Böhm-Vitense 1958), the convective flux variable is expressed proportional to the entropy gradient and a convective velocity scale. The entropy gradient can be expressed using thermodynamic relations assuming a homogenous composition,

which allows us to express the convective flux variable as

(see e.g. Kuhfuß 1986, 1987, or A22, Sect. 2.1). Here,  is a parameter whose value is calibrated by comparing the 1-equation local model to the MLT. When approximating the convective flux in Eq. (8) in this way it is only necessary to solve for the convective variable ω. We refer to this model as the 1-equation model. When applying the 1-equation model, the dissipation length is computed according to the approximation by Wuchterl (1995), that is c3 = 0 for the computation of Eq. (14).

is a parameter whose value is calibrated by comparing the 1-equation local model to the MLT. When approximating the convective flux in Eq. (8) in this way it is only necessary to solve for the convective variable ω. We refer to this model as the 1-equation model. When applying the 1-equation model, the dissipation length is computed according to the approximation by Wuchterl (1995), that is c3 = 0 for the computation of Eq. (14).

3. Three-dimensional hydrodynamic simulations of stellar core convection

In this section, we give an overview of the numerical code we used to compute the 3D simulations and the specific setup of our simulations. Furthermore, we describe how the spherical averages are computed from the 3D data.

3.1. Initial stellar models

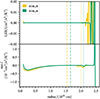

To set up the hydrodynamic simulation, we used results from 1D stellar structure models. For this purpose, we used the 1D Garching Stellar Evolution Code (GARSTEC, Schlattl & Weiss 1999; Weiss & Schlattl 2008). For the following analysis, we initialised two 3D simulations with different 1D stellar models of a 3 M⊙ main-sequence star at solar metallicity to understand the impact of the initial model on the simulation result. The first simulation was initialised with a model computed employing the Kuhfuß 3-equation theory as described in Sect. 2.2. For this model, we followed the procedure of A22. The second simulation was initialised with a starting model computed using MLT and ad hoc overshooting according to Freytag et al. (1996). For the overshooting we chose a parameter value of fOV = 0.02. For simplicity, we refer to the two 3D hydrodynamic simulations as the sim_k simulation and the sim_m simulation, respectively, for the remainder of this paper1. In Fig. 1 we show the temperature stratification of the convective core of our 1D models as dot-dashed lines. In the 3-equation model, the temperature gradient changes over a finite radial distance from the close to adiabatic regime in the convective core to the radiative regime in the envelope. The local nature of MLT causes a much more abrupt transition in the MLT model. Therefore, it is important to initiate hydrodynamic simulations with both models, in order to understand the influence of the initial temperature stratification on the outcome of the simulations. For long enough simulation times (on the order of the thermal timescale) the simulations are expected to reach a similar solution of the convective core structure. We discuss the implications of the different initial thermal stratification for the simulation results in Sect. 7. We picked stellar models with a central hydrogen abundance of Xc = 0.6975, which means that the star has reduced its initial hydrogen abundance by less than 1% in the centre. The hydrogen profiles of the two initial models are shown in the lower left panel of Fig. B.1. The temperature, pressure, and density of the two initial models can be found in the other panels of Fig. B.1.

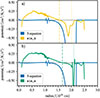

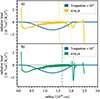

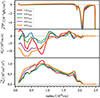

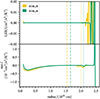

|

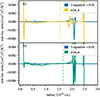

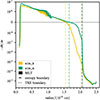

Fig. 1. Time-averaged superadiabaticity of the simulations (solid lines) and the initial models (dot-dashed lines). The dot-dashed orange line shows the superadiabaticity of the 1-equation model for comparison. The vertical dashed and dotted lines indicate the position of the entropy and TKE boundary (for definitions, see Sect. 4.1), respectively. |

These 1D models serve not only as initial models for the 3D simulations, but they are also used to directly compare TCM predictions with the simulation results. Following A22, we also constructed a corresponding 1D model with the 1-equation Kuhfuß model, which allows us to compare the simulation results with this TCM. In contrast to the MLT, the 1-equation model self-consistently develops an overshooting region around convective zones, as in the 3-equation model. The temperature gradient in these overshooting regions is close to being adiabatic (see A22 and Fig. 1). The extent of the overshooting region can be controlled by αω. We find that for αω = 0.15 the extent of the overshooting region of the 1-equation model matches the 3-equation model. So in total we compare the 3D simulations with three 1D stellar models, which we refer to as the MLT model, the 1-equation model, and the 3-equation model. As discussed above the MLT model includes ad hoc overshooting.

The 1D models used here do not include the effects of rotation or magnetic fields. Similarly, the sim_k and sim_m simulation do not include these effects. The 1D models do hence make the same assumptions about the underlying physics as the simulations. The Kuhfuß 1- and 3-equation models are a first step beyond MLT to take the effects of the turbulent flows into account. This allows us to study the effects of turbulent convection in isolation.

3.2. Simulation setup and numerics

For our 3D simulations of stellar core convection, we used the fully compressible SEVEN-LEAGUE HYDRO code (SLH, Miczek 2013; Edelmann 2014; Miczek et al. 2015), which solves the inviscid Euler equations of fluid dynamics with a finite volume scheme (see Edelmann et al. 2021, and references therein for the equations that get solved and details on the implementation). The SLH code follows the implicit large eddy simulations (ILES) approach, in which the smallest scales are filtered out, and only the larger, energy containing scales are simulated (e.g. Pope 2000). In ILES the physical dissipation lengthscale is not resolved by the simulation, but rather the numerical methods naturally dissipate the kinetic energy of the turbulent flows at scales close to the grid resolution element. Following Kolmogorov (1942), the flow properties at the integral and inertial scales remain unaffected by the details of the dissipation mechanism. The flows in stellar cores are highly subsonic, which makes compressible explicit time integration schemes computationally prohibitively expensive. We therefore used the implicit time integration scheme ESDIRK23 of Hosea & Shampine (1996). The low Mach number flows in the convective regions also required us to use a specialised flux function in order to avoid excessive dissipation (see for example the discussion in Miczek et al. 2015; Edelmann et al. 2021; Horst et al. 2021). For these simulations we applied the AUSM+-up flux function (advective upstream splitting method, Liou & Steffen 1993; Liou 1996, 2006). Overall the scheme is second-order accurate in time and space. We closed the system of equations with the Helmholtz equation of state including the ideal gas law and radiation pressure (Timmes & Swesty 2000), which differs from the OPAL EOS (Iglesias & Rogers 1996) used in the 1D models. Another important requirement for accurate simulations of hydrodynamic flows in the stellar interior concerns the state of hydrostatic equilibrium. Deviations from the hydrostatic equilibrium caused by an imperfect balance of pressure and gravity terms in the numerical scheme or the initial model may cause spurious flow velocities, which can dominate the physical flow. To avoid this, well-balancing schemes have been developed to numerically preserve the state of hydrostatic equilibrium over longer time. The deviation well-balancing scheme (Berberich et al. 2021) allows maintaining hydrostatic equilibria on the machine precision level by subtracting a reference state from the hydrodynamical quantities. The advantages of this scheme are demonstrated in Edelmann et al. (2021). The radiative flux was taken into account by means of a diffusion approximation. The opacity profiles were taken from the 1D stellar models and are not updated as the simulation evolves. The mean composition of the 1D models was taken over into the 3D simulations. We note, however, that the mixed regions of the 1D models extend further out in radius than the turbulent convective region in the 3D simulations, such that the convective region has uniform composition (see Table 1).

Comparison of different radial locations in the stellar models and simulations.

The SLH code has been used for several applications in stellar astrophysics, for example convective He-shell burning (Horst et al. 2021), the study of internal gravity waves (IGW) (Horst et al. 2020), shear instability (Edelmann et al. 2017), silicon burning (Röpke et al. 2018), convective core boundary mixing (Andrassy et al. 2024), and turbulent dynamo action (Leidi et al. 2023). Recently, Andrassy et al. (2022) carried out a code comparison study including SLH among other codes and demonstrated that all codes are in good agreement with each other for a convection setup of astrophysical relevance. Furthermore, SLH has been successfully applied to various test cases, for example a Gresho Vortex, the Kelvin Helmholtz instability, or a rising hot bubble (Miczek et al. 2015; Edelmann et al. 2021). This is an indication of the robustness of the numerical methods used. We hence conclude that the SLH simulations discussed in this work are fully suited for a comparison with 1D stellar models.

We set up the simulation in a wedge geometry in spherical coordinates with an extent of 45° in the θ direction and 45° in the ϕ direction. Each angular direction was discretised in 96 regularly spaced cells. In the radial direction, the wedge comprises approximately 2.5 × 1010 cm discretised using 384 regularly spaced grid cells. It has been shown previously that ILES results converge to the Kolmogorov scaling described above with increasing resolution (Cristini et al. 2017; Horst et al. 2021; Lecoanet & Edelmann 2023). Horst et al. (2021) used SLH to simulate He-shell burning in a massive star on a very similar grid configuration as in our case. The latter authors show that the RANS analysis already converges at their lowest resolution. Similar conclusions were reached by Cristini et al. (2017) for their RANS analysis. Further results by Andrassy et al. (2022, 2024) demonstrate that SLH results converge to the scaling for an increased resolution, as describe above. In our case, the convection zone is covered by about 300 points in the radial direction, and hence better resolved than in these simulations at their respective lowest resolution.

The multi-dimensional grid spans 1.16 pressure scale heights in the radial direction and 0.38 pressure scale-heights above the formal Schwarzschild boundary of the stellar models. In the very centre, a region of 109 cm (i.e. approximately 4% of the radial extent of the grid) was cut out to avoid the coordinate singularity of spherical coordinates. In the θ and ϕ direction, periodic boundaries were applied. In the radial direction, wall boundaries were used, that is, the velocity component perpendicular to the boundary is set to zero such that the flow turns sideways. The 1D initial stellar models described in Sect. 3.1 were mapped as a background into the 3D simulation following the procedure described by Edelmann et al. (2017). The model was first interpolated from the Lagrangian grid onto the Eulerian grid, which causes deviations from the initially perfect hydrostatic equilibrium. Subsequently, the density of the interpolated model was changed to reinstate a perfect hydrostatic equilibrium. In this process, the temperature stratification was forced to match the temperature stratification of the initial 1D stellar model. This last step is mainly necessary due to small differences of the EOS between GARSTEC and SLH. We did not follow the nuclear evolution of the H-burning core, since the estimated change in hydrogen abundance during the simulation time is completely negligible. Instead, we included the energy generated by nuclear fusion by a time constant heating profile. The radial distribution of the heating rate was taken from the initial stellar model. Both 3D simulations were evolved over approximately 104 h of physical time. The convective flow was seeded by introducing sinusoidal pressure perturbations with a relative amplitude of 10−7. Figure 2 shows the time evolution of the angularly averaged velocity magnitude throughout the domain. This illustrates how this perturbation slowly builds up into a turbulent flow before it reaches a quasi-steady state after approximately 2 × 103 h. We exclude this initial transient phase from our analysis, such that our averaging interval consists of approximately 8 × 103 h elapsed time in the simulation. This is only a small fraction of the Kelvin Helmholtz timescale at the Schwarzschild boundary of approximately 2.5 × 105 years. The implications of this mismatch of timescales for the interpretation of the simulation results and the comparison to the 1D models are discussed in Sect. 7. Given current numerical methods it is, however, not possible to simulate a substantial fraction of this timescale at the nominal stellar luminosity.

|

Fig. 2. Time evolution of the angularly averaged velocity profile. The top and bottom panels show the sim_m simulation and the sim_k simulation, respectively. The end of the initial transient phase is indicated with a vertical dashed white line. |

In Fig. 3 we show a representation of the convective flow in slices through the computational domain. We indicate the formal Schwarzschild boundary, which we define as the radial location where ∇ad = ∇rad, of the initial models with a white dash-dotted line in each panel. The results of the sim_k and sim_m simulation are shown in the left and right column, respectively. The upper panels show a slice in the x–z plane rotated by π/8 around the vertical axis, and the lower panels show a slice in the x–y plane. The Mach number is colour coded on a logarithmic scale. As discussed above, the Mach number of flows in convective cores on the main sequence is low and indeed does not exceed approximately 3 × 10−4 in the present simulations. The convective flows shown in Fig. 3 present a clear separation of spatial scales. This result arises from the use of specialised flux functions in SLH, which dramatically reduce the excessive amount of numerical dissipation typical of standard methods for fluid dynamics when used to model highly subsonic flows (Miczek et al. 2015; Edelmann et al. 2021). Without using a low-Mach solver, the problem of core convection in upper main sequence stars could only be studied with the so-called enhanced luminosity method (ELM; e.g. Käpylä et al. 2023, and references therein). The idea behind ELM is to artificially boost the driving luminosity of the convection by a large factor to considerably increase convective velocities and in turn the Mach number. In fact, in mildly subsonic regimes (Ma ∼ 0.01 − 0.1), standard shock-capturing methods can still provide accurate numerical results (Andrassy et al. 2022). However, altering the driving luminosity would also change the thermal structure of the relaxed model, which implies that we would no longer be testing properties of the Kuhfuß model2.

|

Fig. 3. Visualisation of the convective flow from the 3D simulations in the x–z and the x–y plane using the Mach number of the flow in the upper and lower panel, respectively. The results from the sim_k simulation are shown in the left column and the results from the sim_m simulation are shown in the right column. The Mach number is indicated with the logarithmic colour-scale. The Schwarzschild boundary of the initial stellar models is indicated with a white dash-dotted line in each panel. We further indicate the entropy and TKE boundary of each simulation with the dashed and dotted white lines (see Sect. 4.1 and Table 1 for details). The upper row shows the raw simulation data, while a radial smoothing has been applied to the flow velocities in the bottom row (see text). The Cartesian coordinates x, y, z are obtained from the conventional conversion of the spherical coordinates r, θ, ϕ of the simulation grid. |

We note that in the sim_k simulation, the turbulent convective motions seem to cease at a radius of about 1.9 × 1010 cm. Beyond this point, we observe that the motions are more ordered, related to internal gravity waves (e.g. Aerts et al. 2010). Beyond 2.05 × 1010 cm motions substantially decrease related to the formal Schwarzschild boundary of the initial models. In the sim_m simulation the turbulent convective motions extend until the Schwarzschild boundary, whereafter an abrupt drop of motions is visible. At the edge of the turbulent convective region, beyond the formal Schwarzschild boundary, some spurious velocity features are visible in the top row of Fig. 3. Our spatial resolution in the radial direction is 6.3 × 107 cm, yet the radial wavelength of IGW with a frequency corresponding to the convective turnover frequency and an angular degree of l = 8 is 2.6 × 107 cm in the stable layer. Moreover, the expected radial wavelength of IGW scales approximately as 1/l (Ratnasingam et al. 2020). All IGW in the stable layer are therefore critically under-resolved. In our numerical scheme, this leads to an odd-even pattern in the radial velocity with unrealistically large amplitudes. Close to the convective boundary waves with l = 8 are still resolved with five radial grid points per wavelength at the convective turnover frequency. However, higher angular orders and lower frequencies are also under-resolved at the convective boundary. Increasing the spatial resolution to resolve these waves is computationally unfeasible and beyond the scope of this project. However, the numerical effect of under-resolved waves can be easily filtered out of the simulation data by applying a smoothing kernel in the radial direction for cell xi,

We applied this smoothing for the velocity and pressure components of the simulation data. The smoothing reduces the amplitudes of the numerical artefacts by a factor of approximately 100 and reveals the underlying wave motions, as can be seen in the bottom row of Fig. 3. The effect on the convective region is negligible. The extent of the turbulent convective region is discussed in more detail below. No data are available below x = 0.1 × 1010 cm, as this is outside of the lower edge of the computational domain.

3.3. Computation of averages

The hydrodynamic simulations provide us with time series of hydrodynamic variables in three spatial dimensions. To compute the RANS equations described in Sect. 2 and compare the 3D data with the stellar convection models, we need to compute suitable averages. In addition to the spatial average, we also computed a temporal average following Mocák et al. (2018). The resulting average then reads

where dΩ = sin θ dθ dϕ denotes the solid angle in spherical coordinates, τ and ΔΩ refer to the time interval and the solid angle that are averaged over, respectively. The initial time-interval needed for convection to fully establish is denoted as τ0. This interval is excluded from the averaging to avoid spurious results from this transient phase. The final average  is then time-independent, as we integrate over the remaining simulation time. We note that both convection models we want to compare to are time-independent. The MLT is time-independent by construction, and for the Kuhfuß equations we chose to neglect the time-derivatives. Therefore, the time-dependence in the simulations is not of interest for us at the moment. In Appendix C, we give some useful identities for the computation of the averages.

is then time-independent, as we integrate over the remaining simulation time. We note that both convection models we want to compare to are time-independent. The MLT is time-independent by construction, and for the Kuhfuß equations we chose to neglect the time-derivatives. Therefore, the time-dependence in the simulations is not of interest for us at the moment. In Appendix C, we give some useful identities for the computation of the averages.

In order to get reliable results, τ has to be chosen large enough to average over statistical fluctuations in the turbulent flow. A natural timescale for this is the convective turnover time τconv defined as

where L is the radial extent of the convective region and  is the space-time average of the velocity magnitude in that region. In our simulations, τconv has a typical value of 1500 h. Space-time averages of quantities directly related to the stratification of the 1D model used to initialise the simulation like density, pressure, or entropy are converged over much smaller timescales than τconv since they evolve on longer timescales and are hence not strongly influenced by turbulent motions. Perturbations of these quantities and dynamical quantities like velocities, on the other hand, evolve on the dynamical timescale and the appropriate size of the time averaging window needs to be estimated.

is the space-time average of the velocity magnitude in that region. In our simulations, τconv has a typical value of 1500 h. Space-time averages of quantities directly related to the stratification of the 1D model used to initialise the simulation like density, pressure, or entropy are converged over much smaller timescales than τconv since they evolve on longer timescales and are hence not strongly influenced by turbulent motions. Perturbations of these quantities and dynamical quantities like velocities, on the other hand, evolve on the dynamical timescale and the appropriate size of the time averaging window needs to be estimated.

In Fig. 4 we compare averages of several quantities that evolve on a dynamical timescale. We show averages starting from τ0 = 2267 h with increasing τ ranging from one to five τconv. We find that correlations of perturbations of slowly evolving quantities like  converge quickly to a stable solution. The same cannot be said about the azimuthal component of the velocity vector (uϕ). Even after averaging over five convective turnover times, the values keep changing significantly. The reason for this is that the initial model corresponds to a non-rotating star and hence the averaged angular velocities should be close to 0. However, in non-rotating simulations the formation of a large-scale dipolar feature in the turbulent flow has been observed (see e.g. Gilet et al. 2013; Cristini et al. 2017; Meakin & Arnett 2007; Woodward et al. 2019). As we ran our simulations on a wedge geometry instead of a full-sphere, we cannot resolve this large scale dipolar feature. The non-zero velocity component in

converge quickly to a stable solution. The same cannot be said about the azimuthal component of the velocity vector (uϕ). Even after averaging over five convective turnover times, the values keep changing significantly. The reason for this is that the initial model corresponds to a non-rotating star and hence the averaged angular velocities should be close to 0. However, in non-rotating simulations the formation of a large-scale dipolar feature in the turbulent flow has been observed (see e.g. Gilet et al. 2013; Cristini et al. 2017; Meakin & Arnett 2007; Woodward et al. 2019). As we ran our simulations on a wedge geometry instead of a full-sphere, we cannot resolve this large scale dipolar feature. The non-zero velocity component in  that we observe in our simulations originates from the periodic boundary conditions employed. Because the adopted numerical scheme introduces little dissipation, the resulting horizontal flow can remain coherent, mimicking a rotational component. This feature evolves slowly over many τconv. We would expect that

that we observe in our simulations originates from the periodic boundary conditions employed. Because the adopted numerical scheme introduces little dissipation, the resulting horizontal flow can remain coherent, mimicking a rotational component. This feature evolves slowly over many τconv. We would expect that  should get close to 0 if we could extend our simulations to a significantly longer timescale. A non-zero mean velocity component is also in conflict with one of the main assumptions of the Kuhfuß model, which assumes

should get close to 0 if we could extend our simulations to a significantly longer timescale. A non-zero mean velocity component is also in conflict with one of the main assumptions of the Kuhfuß model, which assumes  .

.

|

Fig. 4. Comparison of |

Despite the non-converging velocity average we find that the azimuthal component of the kinetic energy  still converges once we average over three to five τconv. This indicates that the magnitude of the velocity field is well converged as well. The same is true for the convective variables, and the superadiabaticity in the bulk of the convection zone. This is further discussed in Appendix D. We hence conclude that variables related to the convective velocity field reached a statistically stationary state on the dynamical timescale, given the thermal stratification.

still converges once we average over three to five τconv. This indicates that the magnitude of the velocity field is well converged as well. The same is true for the convective variables, and the superadiabaticity in the bulk of the convection zone. This is further discussed in Appendix D. We hence conclude that variables related to the convective velocity field reached a statistically stationary state on the dynamical timescale, given the thermal stratification.

For the following analysis, we averaged all profiles over five τconv. Even though the simulations are converged on the dynamical timescale, we still observe a secular evolution of quantities (e.g. the thermal stratification towards the boundary of the convective core in the lower panels of Fig. D.1 or the radial extent of the turbulent convective region) over the simulation time span. We attribute this to the different thermal stratifications in our two initial stellar models. To arrive at a consistent thermal and velocity structure independent of the initial models, simulation times on the order of the thermal timescale would be needed (e.g. Andrassy et al. 2024). This is illustrated in Fig. 1, which shows that the two simulations still have a different mean thermal stratification in the convective boundary layer. Together with the dynamical convergence, this makes results in the bulk of the convection zone and related to the dynamical evolution more robust than those obtained in the boundary layer and dependent on the thermal stratification. In the following, we use the comparison between the two simulations to understand which results are still influenced by the initial models. This is important when interpreting the results of Sects. 4 and 5. For more details we refer to Sect. 7.

4. Convective variables

Our 3D simulations allow us to directly extract all terms included in the Kuhfuß model by performing space-time averages as described in Sect. 3. We then compare the extracted averaged profiles with the predicted profiles of the 3-equation model as well as the MLT and 1-equation model in order to test the accuracy of these convection models. The two profiles with the largest influence on stellar structure and evolution are the TKE, ω, and the convective flux variable, Π. These quantities control the extent of the convectively mixed region (see Eq. (15)) and the temperature stratification (see Eq. (13)), respectively. The detailed profiles around the convective boundary are especially important for the stellar structure. Therefore, we first define the relevant convective boundaries in our simulations.

4.1. Convective boundary definitions

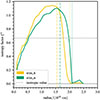

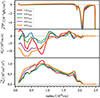

The first boundary we define is the entropy boundary, which separates regions based on their linear stability to convective motions assuming homogenous composition, which can be assumed in convective regions because the mixing efficiency is high. We determined the entropy boundary of the simulations by a space-time average of the entropy gradient, which we show in Fig. 5. The stratification becomes formally stable to convection for positive entropy gradients (see Eq. (16)). We therefore set the entropy boundary of the simulations at the point where the averaged entropy gradient changes sign. The radial positions of this boundary are given in the second column of Table 1. In one-dimensional stellar models, the dimensionless temperature gradients play an important role to define convective boundaries. In these models, the entropy boundary is equivalent to the point where the model temperature gradient equals the adiabatic temperature gradient (∇ = ∇ad) (see Eq. (16)). In MLT, the entropy boundary is identical to the formal Schwarzschild boundary, which is defined as the radius where the radiative temperature gradient equals the adiabatic temperature gradient (∇rad = ∇ad). In the Kuhfuß 3-equation model and the 3D simulations, the actual temperature gradient may however behave independently of the radiative temperature gradient and become subadiabatic well within the formal Schwarzschild boundary. We do not consider the region with positive entropy gradient at the lower end of the simulation domain in our analysis, as we consider this to be an artefact of the lower boundary and the heating profile.

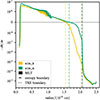

Another way to define the convective boundary is to look at the velocity field in the simulations. Convective flows that pass through the Schwarzschild boundary into the formally stable layer are slowed down by buoyancy and eventually turn around. At the turn-around point the radial velocities are therefore close to zero, while there are still significant angular velocities. The isotropy factor ξ of the velocity field is hence a good indicator for the convective boundary. We compute  as the ratio of the radial TKE

as the ratio of the radial TKE  to the total TKE. The profile of ξ2 extracted from the simulations is shown in Fig. 6. As expected, ξ2 is dropping for radii greater than the entropy boundary, confirming our picture that radial velocities are converted into angular velocities beyond that point. At some distance from the entropy boundary, the profile of ξ2 flattens out and remains small throughout the rest of the simulation domain. In this flat region, angular velocities are dominating over radial velocities, which is characteristic for an internal wave dominated region (see e.g. Horst et al. 2020). We set the boundary of the convective zone at the base of the wave dominated region, which we assume to start when ξ2 reaches a value of 0.01. We call this the TKE boundary and give the radial position in the fourth column of Table 1.

to the total TKE. The profile of ξ2 extracted from the simulations is shown in Fig. 6. As expected, ξ2 is dropping for radii greater than the entropy boundary, confirming our picture that radial velocities are converted into angular velocities beyond that point. At some distance from the entropy boundary, the profile of ξ2 flattens out and remains small throughout the rest of the simulation domain. In this flat region, angular velocities are dominating over radial velocities, which is characteristic for an internal wave dominated region (see e.g. Horst et al. 2020). We set the boundary of the convective zone at the base of the wave dominated region, which we assume to start when ξ2 reaches a value of 0.01. We call this the TKE boundary and give the radial position in the fourth column of Table 1.

In Fig. 5, we see that the sign change of the entropy gradient happens well before the boundary of the TKE and the MLT-Schwarzschild boundary are reached. We note that both simulations have the sign change at approximately the same radial location. The entropy gradients also agree for radii greater than the TKE boundary. The transition region, however, is different. Around the sign change, we find a more extended region with an entropy gradient close to zero (i.e. a close to adiabatic temperature gradient) in the sim_m simulation, while in the sim_k simulation the entropy transitions more steeply from the superadiabatic to the subadiabatic regime. Towards the TKE boundary, the entropy gradient of the sim_m simulation drops steeply from the close to adiabatic value to the value in the radiative region. This difference can be attributed to the lack of thermal relaxation as discussed in Sect. 3.3 where the sim_k simulation would evolve towards an almost adiabatic stratification in the transition region for longer simulation times (see also Fig. D.1).

|

Fig. 5. Negative gradient of the mean entropy as a function of radius on a symmetric logarithmic scale. The entropy boundary is indicated with a vertical dashed line in the respective colour. The boundary of the TKE is indicated with a vertical dotted line in the respective colour. The formal Schwarzschild boundary of the initial stellar model computed using MLT is indicated with the dashed dark grey line. |

|

Fig. 6. Flow isotropy as a function of radius computed from the RANS data obtained from the sim_k and sim_m simulation in yellow and green, respectively. We indicate the entropy and TKE boundaries with dashed and dotted lines in the respective colour. |

At this point, we also point out that the convective flow in the simulations is not isotropic. Isotropic convection corresponds to ξ2 = 2/3. In the bulk of the convection zone we find ξ2 > 2/3, that is the flow is radially dominated. Similar results have for example been found in simulations by Andrassy et al. (2022), Kupka et al. (2018) or Viallet et al. (2013). This clearly shows that the isotropy assumption of the Kuhfuß model is not valid for convective cores.

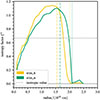

4.2. Turbulent kinetic energy

In Fig. 7 we compare the model predictions of the TKE profiles with the results of the sim_k and sim_m simulation in the upper and lower panel, respectively. The same results are shown in Fig. E.1 on a logarithmic scale. For comparison, we show the results of the 1- and 3-equation model in each panel. The vertical lines indicate the different boundaries that we defined in Sect. 4.1. The TKE is not included in the MLT model itself, but can be easily computed based on the MLT velocity estimates if we assume an isotropic velocity field as in the Kuhfuß model. The TKE of the MLT model is then given by

|

Fig. 7. Comparison of the TKE ω as a function of radius. Each panel shows the results obtained from the 1- and 3-equation model and from an MLT model with a blue, orange and black line respectively. The associated RANS correlations extracted from the sim_k and sim_m simulation are shown in the upper panel and lower panel, respectively. We indicate the entropy and TKE boundaries with dashed and dotted lines in the respective colour. |

where uMLT denotes the convective velocity obtained from MLT. We show this profile as a black dash-dotted line in Fig. 7. This estimate for the TKE of the MLT exceeds the amplitude of the simulation results as well as the TKE from the Kuhfuß models by a factor of four. This is due to a difference in the dissipation length as was shown in A22. Therefore, we argue that the MLT does not provide a good estimate of the TKE for the given choice of the mixing length parameter α. We note that the values for α in the MLT and Kuhfuß models are obtained from separate solar calibrations.

Throughout the convection zone, the shape of the averaged TKE in the sim_k and sim_m simulation matches the predictions of the 1- and 3- equation models. The differences in the averaged TKE profiles in the sim_k and sim_m simulation can be largely attributed to the different initial thermal stratifications. The lower value of the entropy boundary in the sim_k simulation leads to a smaller value of the TKE boundary as compared to the sim_m simulation (see Table 1). This can be also seen in the flow field in Fig. 3, where a layer of waves is generated in the sim_k simulation beyond the entropy boundary. Similarly, this behaviour can be illustrated in the TKE profiles shown in Fig. 7. While in the sim_k simulation the TKE shows a step between the entropy and TKE boundary (coinciding with the generation of waves in this simulation), the TKE in the sim_m simulation reaches all the way to the Schwarzschild boundary where it drops sharply. Finally, the amplitude of the TKE is reduced in the sim_k simulation as compared to the sim_m simulation since the super-adiabatic region in the sim_k simulation is expanding. The growth is driven by the entrainment of high entropy material from the stable layer, which requires some kinetic energy. In contrast, the shrinking super-adiabatic region in the sim_m simulation uses less kinetic energy for entrainment. Here, this leads to the amplitude of the TKE of the sim_k simulation being in agreement with the predictions of the Kuhfuß model while the sim_m simulation exceeds these predictions. Towards the outer boundary of the simulation domain we observe another sharp rise in the TKE (see Fig. E.1). This is caused by the outer wall boundary condition. Since no energy is allowed to cross the boundary, the piled up thermal energy at the domain boundary gets converted into kinetic energy. We therefore do not consider the region with radius greater than 2.3 × 1010 cm in our conclusions.

The values for the TKE boundary depend strongly on the chosen definition (see for example discussion in Higl 2019; Higl et al. 2021). According to the definition laid out in Sect. 4.1, the region with significant TKE in the simulations is much less extended than in the stellar models. However, when defining the boundary as the point where the TKE decreased by a substantial fraction (of 10 to a 1000) as compared to the maximum, the TKE boundary is very comparable between simulations and stellar models (see Fig. E.1). While the TKE boundary in the Kuhfuß TCM can be changed by varying αω, the Schwarzschild boundary poses a lower limit for the convective core size, reached for a parameter value of αω = 0. Hence, for the former definition of the TKE boundary it would not be possible to tune αω to match the observations, while for the latter definition the simulations and stellar models are already in good agreement for the chosen parameter value. The TKE boundaries in the different simulations and stellar models are summarised in the fourth column of Table 1 in terms of radius, and in the fifth column in terms of fractional mass. For the MLT model, the TKE boundary coincides with the formal Schwarzschild boundary given in the third column because the nature of the model is local. Therefore, the values quoted in the fourth and fifth column refer to the chemically mixed core size in this case. By construction, the TKE of the 1- and 3-equation model have the same radial extent.

The excellent agreement between the TKE profiles and the model predictions indicates that the Kuhfuß model includes the most relevant physics in convective cores despite its wrong assumption about isotropy. The isotropy factors only seem to become important close to the convective boundary, where we see the largest deviations from the predictions. As the assumptions about the flow isotropy change the behaviour of the non-local terms, they are also expected to have a large impact on the overshooting distance (see K22). A simple solution to include anisotropy effects into the Kuhfuß model would be to include the profile of ξ into the equations. Since we see large differences in the ξ profiles of the sim_k and sim_m simulation (see Fig. 6), this approach does not seem desirable. It is also highly unlikely that different convection zones would lead to the same ξ profile. In order to include the effects of anisotropic flows properly into the Kuhfuß model, it is necessary to separate the radial from the total TKE equation. Other TCMs by Xiong et al. (1997), Li & Yang (2001) or Canuto (1992) already include this additional equation. We refer to Li & Yang (2007), Zhang & Li (2012a), Zhang (2016) for applications of these models discussing the role of the radial to the total TKE. We note, however, that the addition of equations into the implicit solver of a stellar evolution code is technically challenging.

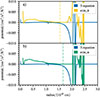

4.3. Convective flux

In Fig. 8 we compare the model predictions of the convective flux variable Π with our simulation results. The model predictions for the 1- and 3-equation model as well as the MLT are almost identical in the bulk of the convection zone. The reason is that the convective flux variable, which represents the energy flux in the stellar model, is set by the energy source terms, since all energy needs to be transported to the surface of the star. The sim_m simulation matches the predictions in the bulk of the convection zone perfectly, while the sim_k simulation reproduces the same shape at an amplitude that is about 20% smaller than the predictions. This is in agreement with the results for the TKE where we found a lower TKE for the sim_k simulation because the super-adiabatic layer still expands. In a stellar model such a reduced convective flux would lead to a very different stellar structure. This can be excluded from an observational point of view.

|

Fig. 8. Comparison of the convective flux variable Π as a function of radius. The results obtained from the 1- and 3-equation model and from the MLT model are shown with a blue, orange and black line respectively. The associated RANS correlations extracted from the sim_k and sim_m simulation are shown in the upper panel and lower panel, respectively. We indicate the entropy and TKE boundaries with dashed and dotted lines in the respective colour. |

The stellar model predictions differ at the convective boundary, where the Kuhfuß models show a region with negative convective flux (see inset of Fig. 8). The width and depth of the negative region is related to the region with the strongest braking of fluid motions and the consequent turnaround of plumes. In the MLT convective motions stop instantaneously at the Schwarzschild boundary without turning around. Hence Π does not show such a negative region in the MLT model. In A22, we show that the depth of the negative convective flux is related to the temperature stratification in the overshooting region (see also Eq. (13)). A large negative value of Π indicates that convection is still rather efficient in the overshooting region. The temperature gradient in that case is therefore close to the adiabatic one, which Zahn (1991) describes as a penetration layer. Small negative values indicate an inefficient convection with a temperature gradient close to the radiative one, which can also be seen by comparing Fig. 5 with Fig. 8. We use the ratio of the minimum to the maximum convective flux as an indicator for the convective efficiency in the negative buoyancy region (see Table 2). For the sim_m simulation we use the value of the minimum that is located slightly within the Schwarzschild boundary at about 2.03 × 1010 cm for our calculations. For the sim_k simulation we use the minimum located slightly within the TKE boundary at about 1.85 × 1010 cm. We find that the absolute value of the ratio of the 3-equation model is about one order of magnitude smaller than that of the 1-equation model. The measured ratios in the sim_k and sim_m simulation are smaller than for the 1-equation model and larger than the 3-equation model. Given the lack of thermal relaxation, we, however, cannot draw conclusions about the thermal stratification that would be reached after evolving the simulations over a thermal timescale.

Comparison of the negative convective flux region in the models and simulations.

We use the radial extent of the negative convective flux region as another criterion for a more quantitative comparison between the TCM and the simulations. For our comparison we use the full width at half maximum of the region with negative convective flux. We summarise the results in the fifth to seventh column of Table 2. As can be inferred already from Fig. 8, the radial extent of the negative convective flux is smaller in the 3-equation model than in the 1-equation model. In the sim_k simulation, the radial extent is similar to the value obtained for the 1-equation model. In the sim_m simulation, we observe a very narrow region of negative convective flux as the change in the temperature stratification acts as a stiff barrier and convective motions are braked in a very narrow region. For longer simulation times, the thermal stratification would adjust, also impacting the shape of this transition. Considering the short simulation times discussed here, we can however not draw any conclusions about this. In 1D stellar models a wider region of negative convective flux as in the sim_k simulation would lead to broader transition regions from the nearly adiabatic to the radiative temperature gradient.

Another important aspect of the temperature structure concerns the so-called Deardorff or counter-gradient layer (Deardorff 1966). This is a region in which the convective flux is still positive even though the entropy gradient is already positive (i.e. temperature gradient is subadiabatic). From a theoretical point of view, such a layer is expected because of the non-local term of the Φ equation. This term transports entropy fluctuations beyond the Schwarzschild boundary and acts as a non-local source of entropy fluctuations. The entropy fluctuations Φ then appear as a source in the Π equation. This layer has been observed in several simulations of stellar convection (Chan & Gigas 1992; Muthsam et al. 1995, 1999; Tremblay et al. 2015; Käpylä et al. 2017; Kupka et al. 2018) as well as other Reynolds stress models (Kupka 1999; Xiong & Deng 2001; Kupka & Montgomery 2002; Montgomery & Kupka 2004; Zhang & Li 2012b) and particularly in the 3-equation model (A22). Here, we investigate whether a Deardorff layer emerges in the 3D simulations of Sect. 3 as well. As mentioned before, the entropy boundary denoted by vertical dashed lines in Fig. 8 indicates the point where the sign of the entropy gradient changes and the stratification becomes subadiabatic. Figure 8 shows that the region of positive convective flux extends substantially beyond this entropy boundary in both simulation, that is a Deardorff layer emerges. It is especially important to note, that the initial model of the sim_m simulation did not have a Deardorff layer. It emerged naturally from the fluid dynamics simulation. The entropy boundaries in both simulations are still evolving during the simulation time, that is, the model is not fully thermally relaxed yet, explaining the differences between the sim_k and sim_m simulation. In order to make strong claims about the size and shape of the Deardorff layer, we would need to reach a thermally relaxed state, which is computationally not feasible at nominal stellar luminosity. Nevertheless, we can confirm the prediction of A22 that a TCM needs to include a convective flux and entropy fluctuation equation in order to improve the predictions of the temperature stratification, since Deardorff layers do not emerge in models without the non-local term in the entropy fluctuation equation. For further discussion of the physical relevance of the Deardorff layer we refer to Sect. 7.2.

4.4. Entropy fluctuations

The third equation of the Kuhfuß model computes the auto-correlation of entropy fluctuations, Φ. We show this quantity in Fig. 9. The profile of Φ is a strictly positive smooth function that is tightly correlated with the mean entropy gradient (see Fig. 5). We find a positive correlation between Φ and the entropy gradient in the superadiabatic regions and an anti-correlation in the subadiabatic regions. This is in contrast to the 3-equation model, which predicts a monotonically increasing Φ except for a small region around the entropy boundary. Around the TKE boundary both simulations show a peak in Φ similar to the 3-equation model. The amplitude of the peak that is located at or slightly above the TKE boundary, however, is two to three times larger in the simulations. Here, the sim_k simulation reproduces the overall shape of the peak better, probably because the thermal structure in the sim_k simulation and the 3-equation model is similar.

|

Fig. 9. Comparison of the squared entropy fluctuations Φ as a function of radius. The results from the 3-equation model are shown with a blue line. The associated RANS correlations extracted from the sim_k and sim_m simulation are shown in the upper panel and lower panel, respectively. We indicate the entropy and TKE boundaries with dashed and dotted lines in the respective colour. |

5. Analysis of individual terms

In Sect. 4 we compare the predictions for the three variables ω, Π, and Φ of the Kuhfuß model with our simulation results and found a general satisfactory agreement strengthening the usefulness of the Kuhfuß model. Within the Kuhfuß model, however, these unknowns are computed from terms that are individually modelled based on physical assumptions (see Sect. 2). Our 3D simulations offer the possibility to test these assumptions.

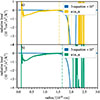

5.1. TKE equation

The TKE Equation (8) has three terms on the right-hand side, that originate from buoyancy contributions, non-local fluxes, and a model for viscous dissipation. The remaining terms of the full RANS Equation (5) are neglected. In order to quantify the contribution CXj(r) of each term Xj to the left-hand side of Eq. (5), we compare the absolute magnitudes of each term |Xj(r)| and normalize them as

where we sum over all terms Xi(r) on the right-hand side of Eq. (5). We then integrate CXj(r) over the convective zone to find the total contribution fraction CXj,

where Δr = r1 − r0 and r0, and r1 are the inner radius of the simulation domain and the TKE boundary, respectively. We give CXj of the TKE equation in the first column of Table 3. A visualisation of the radial dependency of CXj(r) can be found in Appendix F.

Contributions of (absolute) individual terms to the total lhs.

Within the Kuhfuß model, the non-local flux term is responsible for setting the size of the convective core (see Ahlborn 2022). In our simulations, we find that it accounts for about 30% of the right-hand side of the TKE equation and dominates towards the TKE boundary (see Fig. F.1). In Fig. 10 we compare the Kuhfuß 1- and 3-equation models, which compute the non-local flux in the downgradient approximation (see Eq. (8)), to the RANS averaged values of the sim_k and sim_m simulation in the upper and lower panel, respectively. To compare consistently with the Kuhfuß model, we transform the non-local term of Eq. (5) using the anelastic approximation (Ogura & Phillips 1962; Gough 1969) into

|

Fig. 10. Comparison of the non-local terms of the TKE equation. The results obtained from the 1- and 3-equation model are shown with a blue and orange line, respectively. The associated RANS correlations extracted from the sim_k and sim_m simulation are shown in the upper panel and lower panel, respectively. We indicate the entropy and TKE boundaries with dashed and dotted lines in the respective colour. |

All curves in Fig. 10 reproduce the same wave-like shape with negative non-local flux contributions in the middle of the convection zone and positive contributions close to the stellar centre and convective boundary. The radial positions of the sign changes in the simulation roughly matches the 1D models. In the stable layer, the non-local flux quickly approaches zero. This indicates that the Kuhfuß solution for the non-local flux contains all relevant physics. The two simulations only differ in the radial position of the transition towards the stable layer and the magnitude of the non-local flux around the convective boundary. This could indicate that some of the parameters of the Kuhfuß model need to be tuned differently. Given the evolving thermal stratification, calibrating the parameters of the convection model, however, remains difficult. Another solution to the mismatch could be the inclusion of flow anisotropy into the model (see Sect. 8.1).

The buoyancy term as given in Eq. (5) is expected to dominate the dynamics of (nearly) incompressible flows like stellar core convection (see left column of Table 3). In the Kuhfuß model it is modelled by the Boussinesq approximation, which directly connects the buoyancy flux to the convective flux variable Π (see first term in Eq. (8)). Even though we do not use this approximation for our RANS analysis, we find that the agreement between the sim_m simulation and the 1D models is excellent (see Fig. G.1 in the appendix). The result of the sim_k simulation is slightly rescaled compared to the 1D models, but the overall shape agrees quite well. Therefore, we argue that the Boussinesq approximation is well justified for this term. Moreover, the shape of the curves in Fig. G.1 is almost identical to Fig. 8 and hence the discussion of the features around the convective boundary is analogous to the discussion of Π.

In addition to the gradient of the mean pressure a second component, involving the pressure fluctuations, shows up in Eq. (5). In Fig. 11 we show these buoyancy pressure fluctuations computed from the simulations. There are two things that we can immediately take away from this figure: (i) while this term is neglected in the Kuhfuß model, our results show that, integrated over the whole convective zone, it actually has a substantial contribution to the total TKE (see Table 3), (ii) its shape is very similar to the non-local term, but with opposite sign (see dashed lines in Fig. 11). We discuss in the following why this similarity is expected. In the TKE equation it is only the flux contribution of the pressure fluctuation term that remains,

(e.g. Canuto 1992). To account for this term, Lumley (1978) suggested the following closure  and a = 1/5 making the pressure fluctuations proportional to the third-order moment of velocity such that

and a = 1/5 making the pressure fluctuations proportional to the third-order moment of velocity such that

|