| Issue |

A&A

Volume 705, January 2026

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A143 | |

| Number of page(s) | 22 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556287 | |

| Published online | 14 January 2026 | |

Magnetic fields in the Shapley Supercluster core with POSSUM: Challenging model predictions

1

Departamento de Física de la Tierra y Astrofísica & IPARCOS-UCM, Universidad Complutense de Madrid 28040 Madrid, Spain

2

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Università degli Studi di Bologna Via P. Gobetti 93/2 40129 Bologna, Italy

3

INAF – Istituto di Radioastronomia Via P. Gobetti 101 40129 Bologna, Italy

4

Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, The University of Chicago Chicago IL 60637, USA

5

Dunlap Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Toronto 50 St. George Street Toronto M5S 3H4 ON, Canada

6

Research School of Astronomy & Astrophysics, The Australian National University Canberra ACT 2611, Australia

7

National Research Council Canada, Herzberg Research Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory PO Box 248 Penticton BC V2A 6J9, Canada

8

Mizusawa VLBI Observatory, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, 2-21-1 Osawa Mitaka Tokyo 181-8588, Japan

9

Universitäts-Sternwarte, Fakultät für Physik, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Scheinerstr.1 81679 München, Germany

10

Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 1 85748 Garching, Germany

11

U.S. Naval Research Laboratory 4555 Overlook Ave. SW Washington DC 20375, USA

12

David A. Dunlap Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Toronto 50 St. George Street Toronto M5S 3H4 ON, Canada

13

Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie Auf dem Hügel 69 53121 Bonn, Germany

14

Minnesota Institute for Astrophysics, University of Minnesota 116 Church Street SE Minneapolis MN 55455, USA

15

Trottier Space Institute, McGill University 3550 University Street Montreal QC H3A 2A7, Canada

★ Corresponding author: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Received:

7

July

2025

Accepted:

17

November

2025

Context. Faraday rotation measure (RM) grids provide a sensitive means to trace magnetized plasma across a wide range of cosmic environments.

Aims. We study the RM signal from the Shapley Supercluster core (SSC) in order to constrain the magnetic field properties of its gas. The SSC region consists of two galaxy clusters, A3558 and A3562, and two galaxy groups between them, at z ≃ 0.048.

Methods. We combined RM Grid data with thermal Sunyaev-Zeldovich effect data, obtained from the POlarisation Sky Survey of the Universe’s Magnetism (POSSUM) pilot survey, and Planck, respectively. To robustly determine the gas density, its magnetic field properties, and their correlation |B| ∝ neη, we studied the RM scatter in the SSC region (𝔖RM) and its behavior as a function of distance to the nearest cluster and/or group (dnrst). We compared observational results with semi-analytic Gaussian random field models and more realistic cosmological magnetohydrodynamical (MHD) simulations.

Results. With a sky-density of 36 RMs/deg2, we detect an excess RM scatter of 30.5 ± 4.6 rad/m2 in the SSC region. When we compare with models, we find an average magnetic field strength of ∼1−3 μG (in the groups and clusters). The 𝔖RM(dnrst) profile, derived from data ranging from ∼0.3−1.8 r500 for all objects, is systematically flatter than expected compared to the models, with η < 0.5 being favored. Despite this discrepancy, we find that cosmological MHD simulations matched to the SSC structure most closely align with scenarios where the magnetic field is amplified by the turbulent velocity (vturb) in the intercluster regions Bℱ ∝ ne1/2vturb on scales dnrst ≲ 0.8.

Conclusions. The dense RM grid and precision provided by POSSUM allows us to probe magnetized gas in the SSC clusters and groups on scales within and beyond their r500. Flatter-than-expected RM scatter profiles reveal a significant challenge in reconciling observations with even the most realistic predictions from cosmological MHD simulations in the outskirts of interacting clusters.

Key words: magnetic fields / polarization / galaxies: clusters: general / galaxies: clusters: intracluster medium / galaxies: groups: general

© The Authors 2026

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Magnetic fields are known to be ubiquitous in the Universe. They span a wide range of scales and strengths: from stars and magnetars (up to ∼1015 G; Shu et al. 2025) all the way to ∼10−9 G in cosmic web filaments (Carretti et al. 2025). In the overdensities of the cosmic web (i.e., superclusters and galaxy clusters) large-scale magnetic fields have also been found. The turbulent intracluster medium (ICM) is permeated by ∼μG magnetic fields at ∼1 − 100 kpc scales (see Govoni & Feretti 2004; Donnert et al. 2018 for reviews of cluster magnetic fields). These magnetic fields play important roles in the dynamics and understanding of the baryonic content of the structures they permeate.

The baryonic content of the local Universe is well constrained, both by the predictions of Big Bang nucleosynthesis through the analysis of the abundance of primordial light elements and observations of the Lyman-α forest at high redshift (Nicastro et al. 2008) and by cosmic microwave background (Planck Collaboration VI 2020). However, only ∼70% of these baryons have been found in observations of the local Universe (Shull et al. 2012). Nonetheless, the remaining ∼30%, the so-called missing baryons, are now claimed to be accounted for, although the uncertainties are yet to be lowered for a more definitive conclusion (Driver 2021). They are expected to lie in the warm hot intergalactic medium (WHIM; Nicastro et al. 2018; Macquart et al. 2020). The WHIM is made up of diffuse ionized gas that fills the filaments of the cosmic web. These missing baryons therefore lie in low-density regions, which makes them hard to detect. Cosmic web filaments and intercluster bridges are the type of low-density structures in the Universe where these baryons are expected be. Recently, evidence has been found for magnetic fields in these filaments (Carretti et al. 2025) and it is therefore natural to think that intercluster bridges, where diffuse radio emission and thermal Sunyaev-Zeldovich (tSZ) effect signals have been detected (Pignataro et al. 2024a,b; Tanimura et al. 2019; de Graaff et al. 2019; Radiconi et al. 2022), are magnetized as well. It is then interesting to determine their level of magnetization and their magnetic field strengths and properties.

The Shapley Supercluster core (SSC; z ≃ 0.048) contains one such intercluster bridge between the massive galaxy clusters Abell 3558 and Abell 3562 (hereafter A3558 and A3562), detected by Planck through the tSZ effect (Planck Collaboration XXII 2016). The tSZ emission of two massive groups of galaxies was also detected in this bridge (SC 1327 and SC 1329). The masses, M500, and radii, r5001, of these four objects can be found in Table 1. The projected distance between the centers of the Abell clusters is ≃4.2 Mpc. Such a system provides a unique laboratory for the study of diffuse magnetized gas in intercluster regions to derive the properties of their magnetic field through Faraday rotation.

Masses (M500) and radii (r500) of the four objects that make up the Shapley Supercluster core (SSC).

Linearly polarized light that travels through an ionized and magnetized medium experiences Faraday rotation, i.e., a rotation of the linear polarization vector χ, which is proportional to the square of its wavelength: Δχ = RM ⋅ λ2, where the constant of proportionality is defined as the rotation measure (RM) (e.g., Ferrière et al. 2021). Since the RM is an integral along the line of sight, the quantity we measure is the sum of all the contributions from every Faraday screen, 𝒮i

The integral goes from the source to the observing point. The constants are e, the absolute value of the charge of the electron, me, its mass, and c, the speed of light. The RM depends on the product of the number density of thermal free electrons (ne) and the magnetic field component along the line of sight (B∥)2. Therefore, to properly quantify how much of the observed rotation is actually due to the Shapley Supercluster, we need to properly account for all other possible contributions, typically local contributions to the source itself, intervening extragalactic structures along the way, and most importantly the Galactic contribution, denoted by GRM. When analysing RM data we consider differences in the RM dispersion of different subsamples. Thus, any contribution to the dispersion that can be set as common to both subsamples, such as the intrinsic contribution from the sources, will cancel out. Given that the GRM contribution can be different at different scales throughout the Shapley region we aim to study, it is necessary to model it in detail.

Radio polarization data has been widely used to study magnetic fields in clusters through Faraday rotation (Murgia et al. 2004; Govoni et al. 2006; Guidetti et al. 2008; Bonafede et al. 2010; Govoni et al. 2010; Vacca et al. 2012; Govoni et al. 2017; Stuardi et al. 2021). However, one of the main sources of uncertainty in these RM grid studies is the limited number of polarized sources whose lines of sight go through the given object of study (Johnson et al. 2020). This limited sampling of the density and magnetic field information is one of the main drivers for the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder-Polarisation Sky Survey of the Universe’s Magnetism (ASKAP-POSSUM) collaboration to build the densest RM grid of the southern sky to date, with about 1 million expected extragalactic polarized sources, aiming for ∼30−50 RM/deg2 (Gaensler et al. 2025). The previous densest wide-area catalog has ∼1 RM/deg2 (Taylor et al. 2009). Recent studies with Square Kilometer Array (SKA) pathfinder telescopes data have shown its capabilities to map and detect ionized and magnetized gas in the outskirts of galaxy clusters (Anderson et al. 2021; Loi et al. 2025) as well as the RM signature of galaxy groups (Anderson et al. 2024). Other recent studies of magnetic fields in galaxy clusters have shown the potential of statistical stacking as an alternative to wide area dense RM grids (Osinga et al. 2022, 2025).

In this work, we study the magnetic field properties of the SSC with ASKAP-POSSUM3 data from the POSSUM Pilot II survey. We focus on the potential of these dense RM grids to estimate the magnetic properties of the gas in the intercluster bridge region between clusters A3558 and A3562. The underlying assumed cosmology throughout this paper is a ΛCDM with Ωm = 0.3, ΩΛ = 0.7, and H0 = 70 km/s/Mpc. The linear scale at the redshift of Shapley is thus 0.941 kpc/″. Section 2 is dedicated to the data used in this work. Sections 3 and 4 show the results derived from the data and the different modeling approaches we followed, respectively. Section 5 contains the discussion of our results. In Sect. 6 we conclude our findings. Appendices A and B provide ancillary results and outline the methods used to extract information from the observations and the modeling, respectively. Throughout this paper, the symbol σ will be used as a measure of the scatter in the RM data, and it always refers to the median absolute deviation (MAD) standard deviation defined as σ = 1.4826 MAD, which is less sensitive to outliers than the traditional standard deviation.

2. Data

2.1. Radio polarization and Faraday rotation data from ASKAP-POSSUM

In this work we use observations from the ASKAP-POSSUM pilot survey by combining data from Band 1 (800 − 1088 MHz) and Band 2 (1296 − 1440 MHz) with a spectral resolution of 1 MHz (Gaensler et al. 2025). The target of these observations was the Shapley Supercluster in two different fields: “core” and “south” (as shown in Fig. 1). The tile center coordinates for “core” and “south” in Band 1 and Band 2 are listed in Table 2. ASKAP’s field of view is 30 deg2, while for the typical integration time and rms noise consult Table 2.

|

Fig. 1. POSSUM RMs used in this work and the definition of the different RM subsamples. The background shows the Planck tSZ effect y map. The dash-dotted squares represent the (6 deg)2 Band 1 ASKAP fields, namely, the “core” and “south” fields, with their centers represented by red crosses. The black contour represents the ybdry = 4.24 × 10−6 value used to define the on-target (orange triangles) and off-target (purple dots) samples. These two are inside the 1.71 × 2.42 deg2 (5.8 × 8.2 Mpc2) y-map cutout used for the analysis (see Sect. 2.2). The zoomed-in region at the top left corner of the plot shows the bridge (cyan triangles) and cluster (blue triangles) subsamples, all of which belong in the on-target region. The bridge box used to define the bridge sources is also represented to ease the interpretation of the plot. |

Summary of observations.

2.1.1. Deriving the RM catalog

For each field, the Stokes I, Q, and U image cubes for the fields were obtained from the CASDA repository4, which were produced by the ASKAP Observatory pipeline using the ASKAPsoft software package (Guzman et al. 2019). The on-axis polarization calibration was done for each of the 36 beams (closepack36 footprint with beam pitch of 0.9 deg) using the unpolarized bandpass-corrected primary calibrator (PKS B1934−638). The off-axis leakage in the Stokes Q and U cubes was corrected using beam models derived from holography observations (which was estimated to result in instrumental polarization levels of order 1% or less of Stokes I for these particular observations by the POSSUM data validation team Vanderwoude et al. 2024; Gaensler et al. 2025). A Stokes I catalog for each field is also provided by the ASKAP Observatory team using the Selavy software package (Whiting & Humphreys 2012; Whiting et al. 2017). To quantify the linear polarization and Faraday rotation properties of all Stokes I sources, a development version of the POSSUM Polarimetry Pipeline was used. Initially it was ensured that the image cubes were convolved both spatially and spectrally to a common angular resolution of 20″ (using the beamcon_3D routine from racs_tools5). The Q and U image cubes were then corrected for the average ionospheric Faraday rotation during the observation using the package FRion6. The 1D IQU spectra were then extracted at the position of each Stokes I catalog entry. To account for any potential contamination of the Stokes Q and U spectra by diffuse polarized emission from the Milky Way, the median Stokes Q and U emission in a 109″ annulus surrounding each source was subtracted (see e.g. Vanderwoude et al. 2024 for details). The optimal annulus size was determined through simulated source tests in an internal POSSUM memo (Oberhelman et al. 2024). The 109″ outer radius is large enough such that the error on the subtracted median value does not affect the noise in the subtracted spectra, while also being small enough such that the procedure does not subtract diffuse emission that is unrelated to that contaminating the target spectra. RM synthesis was then applied to the individual spectra using the RM-Tools software package rmsynth_1d7, which output an RM catalog in the standardised form (Van Eck et al. 2023).

2.1.2. Band 1 and Band 2

While both Band 1 and Band 2 data were processed with the development version of the POSSUM pipeline (Purcell et al. 2017), the Band 1 data were processed as single fields (individually for core and south fields), while the Band 2 data were first combined (interleaved for core and in the overlap region with the south) and then split into smaller tiles (∼3.5 deg2). The IQU spectra were extracted in the same manner from both the single fields and the smaller tiles, as described above.

To create the most reliable RM catalog from the Band 1 and Band 2 data, we initially applied a cut in signal to noise of S/N > 6 (in polarization) to Band 1 core data, and S/N > 8 to Band 2 data8. In both Band 1 and Band 2 the angular resolution is 20″, so for multiple sources whose separation is < 20″, we only kept the one with a higher S/N, thus avoiding statistical bias from duplicated RM components. Band 1 was split into core and south data, so we merged both catalogs dealing with the overlap region between them by removing the south counterparts and keeping the core ones, due to a more reliable instrumental polarization correction in the latter. In Band 1 and Band 2 we only kept sources with Ifitstat < 5 thus filtering out those that are too faint in total intensity or those with problems raised during the model fitting of Stokes I9. There were sources that are lying in the overlap region between Band 1 south and Band 2 observations. To deal with these, for those in Band 1 we kept sources with a distance to the nearest beam < 0.3 deg, and distance to the tile < 1 deg. This allowed us to remove sources potentially dominated by leakage and closer to the edges of the beams. For both Band 1 south and Band 2 sources we applied a cut in the degree of polarization > 1.5% (Band 1 core sources were applied a > 1% cut, due to a better widefield leakage correction in that field). Then, we only kept unique Band 2 sources, i.e., not detected in Band 1, since Band 2 has a smaller bandwidth in λ2 thus higher uncertainty in the RMs.

2.1.3. Combined final catalog

In the end, 369 sources from Band 2 and 2106 out of Band 1 data were kept10. Nonetheless, a further selection process was made to end up with a total 149 rotation measures. These where chosen to be those in the relevant region of the SSC that allows us to study its clusters and groups, comprising the combination of the on and off-target regions (see Fig. 1). Out of the final total 149 sources, only 12 of them are from Band 2 and no “south” sources made it to this final version. The catalog has metrics to quantify the Faraday complexity of the sources, and we find that only 4% of the on-target sources have hints of Faraday complexity. Furthermore, the data used in this work is unsuitable for detailed complexity analyses (e.g. QU-fitting) due to the suboptimal instrumental polarization correction. Figure A.1 shows the Stokes I image of ASKAP’s fields with the positions of the final RMs overlaid. The median error of the sources in the final RM grid is δRM = 1.98 rad/m2 and the density of sources is 36 RM/deg2. The most relevant quantities for the polarized sources in the final catalog can be found summarized in Table A.3 for an example set of ten of them.

2.1.4. Embedded sources identification

We searched for sources embedded in Shapley, i.e., within ≲16 Mpc of A3558 (at z = 0.048). 4 sources were found out of the 46 sources in the detected subsample (see Sect. 3.4 for the definition of it) to be embedded. Their component names are: J132928−313924, J133048−314323 (in the bridge subsample), J133503−313918, and J132803−314527 (in the clusters subsample).

2.2. Thermal Sunyaev-Zeldovich map from Planck

When CMB photons propagate through a gas of hot thermal electrons (like a galaxy cluster) they are likely to scatter off them, and typically they gain energy from these collisions (inverse Compton scattering). The way the strength of this effect is parametrized is via the y-Compton parameter (Mroczkowski et al. 2019) defined as

where again, the integral is along the line of sight, Pe = nekBTe is the pressure of the gas of electrons, and σT is the Thomson cross section.

We have used the MILCA (Modified Internal Linear Combination Algorithm) full mission ComptonSZ map from the 2015 Planck results (Planck Collaboration XXII 2016). MILCA is a component separation algorithm that was developed to reliably map spatially localized emission as opposed to the diffuse emission associated with the CMB (Hurier et al. 2013). We downloaded a cutout of the Shapley Supercluster from Planck’s Legacy Archive web page11 with pixel size of 1.71′. The relevant SSC region is 1.71 × 2.42 deg2 (see Fig. 1).

There are other y maps available in the literature that use the same initial Planck data and implement different algorithms for tSZ signal reconstruction, along with deprojection of the cosmic infrared background (CIB) dust contribution (McCarthy & Hill 2024). The root-mean-squared noise of this map in the same SSC region is 4% lower than for the MILCA Planck map. The median ratio of the map values from McCarthy & Hill (2024) and those from the MILCA Planck map is 1.1, thus indicating minimal impact on results derived from the y map.

3. Observational results

In this section we use the POSSUM RMs to study the statistical properties of the magnetized gas in the SSC, and how they vary as a function of distance from the cluster and group centers.

3.1. Galactic foreground subtraction and residual RMs

To study the RM properties that are only related to the SSC, we need to remove correlated RM structures on scales larger than the SSC. The dominant contribution on such scales is expected to come from the Milky Way insterstellar medium (ISM), which we refer more generally to as the Galactic RM (GRM), including the ISM, circum-galactic medium (CGM) and any magneto-ionized media associated with the Milky Way. We define the residual RM as

To estimate the GRM we use the total 2475 POSSUM RMs derived in Sect. 2.1.3. This grid has an areal density of ρRM ≃ 41.5 deg−2. As a consequence, we did not employ commonly used methods such as the all-sky map of the Milky Way contribution (Hutschenreuter et al. 2022), which effectively loses information on scales ≲1 deg2. Instead, we have used the annulus method (Anderson et al. 2024), in which we can adapt the inner and outer annulus radii as relevant to the SSC system.

3.2. GRM from the annulus method

In this method, for each RM value, we estimate the GRM at the source’s position by defining an annulus and averaging12 over the RM values that lie inside it. The annulus is defined by two parameters: the inner exclusion radius rinner and the number of sources we want to average over. First we compute the distance from the source to every other source in the catalog and we keep the 50 nearest ones whose distances are > rinner. Thus, the furthest source defines the outer radius of the annulus.

The parameters rinner and the number of sources to average over, were chosen to avoid removing the actual SSC RM structure, while accounting for the foreground Galactic contribution. The chosen rinner = 1.7 Mpc (0.5 deg) has a size comparable to the average r200 of the four objects in the Shapley core ( ), thus we are not removing information inside the r200 of the clusters and groups, while any contributions on larger scales are expected to be sub-dominant, as evidenced by cluster-derived magnetic field power spectra (Domínguez-Fernández et al. 2019). By choosing 50 sources to average inside the annulus, the average outer radius is

), thus we are not removing information inside the r200 of the clusters and groups, while any contributions on larger scales are expected to be sub-dominant, as evidenced by cluster-derived magnetic field power spectra (Domínguez-Fernández et al. 2019). By choosing 50 sources to average inside the annulus, the average outer radius is  . The RRM errors are computed as the quadratic sum of the measurement errors (δRM) and the standard error of the mean of the 50 sources averaged over in the annulus for that particular source i

. The RRM errors are computed as the quadratic sum of the measurement errors (δRM) and the standard error of the mean of the 50 sources averaged over in the annulus for that particular source i

In Fig. 2 the RRM and GRM maps are shown. A smooth gradient over the SSC is seen in the GRM, while the RRM shows a more irregular pattern. We compared our GRM results with the all-sky reconstruction of the Milky Way contribution in Hutschenreuter et al. (2022). In contrast with the GRM gradient in Fig. 2, we found an almost constant GRM throughout the SSC compatible with the average value from the annulus method. This is consistent with the fact that this map loses information on scales lower than ∼1 degree (due to the sparsity of the underlying input RM data). The median δGRM in the Hutchenreuter et al. map is also approximately two times larger than for the annulus method. We also checked for a potential correlation between the GRM and the dust polarization map (Erceg et al. 2024) from Planck observations (Planck Collaboration XI 2020) finding no significant relation. This is supported by the fact that the thermal electrons, which are responsible for the GRM, do not necessarily reside in the dust-dominated region of the Galaxy.

|

Fig. 2. RRM and GRM maps made by interpolation to the nearest pixel of the estimated value at the particular position of a source from our catalog with the annulus method. The black contour corresponds to ybdry = 4.24 × 10−6 (same as in Fig. 1; see Sect. 3.3). The centers of the clusters and groups are represented by black crosses, while the dash-dotted circles represent their r500. Left: Residual rotation measure map. The random nature of the patches in the map with similar sizes between them indicates that we have removed the larger coherent RM structure of the foreground Galactic contribution, while retaining the information about the SSC. Right: GRM map. Contrary to the behavior of the patches in the RRM map, this map exhibits a large continuous gradient in the RMs, which is expected for the large-scale Galactic contribution. |

A comparison of the statistical properties of the RMobs and the RRM is shown in Table 3. The RRM distribution exhibits a mean and median closer to zero and a lower scatter than the observed RM distribution. Figure 3 shows the histograms of the RMobs and RRM distributions. In Appendix A.2 we demonstrate the robustness of this method.

|

Fig. 3. Histograms of observed rotation measures (RMobs) and residual rotation measures (RRM) of the 149 sources used for our analysis. |

3.3. Definition of subsamples

The 149 sources in the catalog we produced (see details in Sect. 2.1) sample the SSC, which corresponds to  RMs/deg2 (3 RMs/Mpc2). We define the extent of the SSC region for study based on the Planck y-map, with the boundary between on-target and off-target regions defined as twice the y-map’s rms noise level ybdry = 2yrms = 4.24 × 10−6 (see Fig. 1 for context), where

RMs/deg2 (3 RMs/Mpc2). We define the extent of the SSC region for study based on the Planck y-map, with the boundary between on-target and off-target regions defined as twice the y-map’s rms noise level ybdry = 2yrms = 4.24 × 10−6 (see Fig. 1 for context), where

-

Off-target ≡ y < ybdry,

-

On-target ≡ y ≥ ybdry.

The on-target region contains 46 sources. The off-target subsample contains 103 sources, which is a sufficiently large control sample that also avoids regions too far from the center. This avoids encountering contributions from other clusters and groups in the wider Shapley Supercluster area. The on-target region contains lines of sight through the Abell clusters and the SC groups. To study these contributions separately the on-target sample is further split into the “clusters” and “bridge” subsamples.

The bridge box (see Fig. 1) was defined to be parallel to the axis joining the centers of the Abell clusters. Despite the overlapping of the groups and clusters, this definition aims to isolate those lines of sight that mainly go through the SC groups (the bridge) inside their r500, with 12 sources in this subsample. The remaining 34 sources that belong to the on-target region, are defined as the clusters subsample. These mainly represent lines of sight that cross the Abell clusters inside their r500.

X-ray data from eROSITA could be used to trace thermal electrons and define the SSC boundaries. The main advantage of eROSITA compared to the XMM-Newton pointed observations is the larger and contiguous area coverage (Bulbul et al. 2024). While eROSITA covers the whole of Shapley, given that the deeper XMM-Newton observations cover the entirety of the SSC, which is the region of interest for this work, no significant improvement is expected from eROSITA data in this context. Furthermore, the linear dependence of the tSZ effect with the electron density makes it a more suitable and sensitive tracer to define the SSC boundary, compared to the squared dependence of the X-ray emission.

3.4. RM signature in the Shapley Supercluster core

Hereafter, we use “RM” for the results derived from the RRMs except where needed in case of a potential confusion. The higher the scatter in a distribution of RMs, the more likely it is that there is an excess contribution from magnetized gas. We calculate the excess RM scatter (MAD standard deviation, Sect. 1) of the SSC as

with a statistical significance of 6.7σ. We found no significant variations in the exact value of the scatter after exploring minor variations in the value of ybdry. The scatter in the on-target region is σRM, on − target = 32.91 ± 4.18 rad/m2, while the off-target sample presents a scatter of σRM, off − target = 12.32 ± 1.54 rad/m2. This value is higher than the expected ∼6 − 8 rad/m2 for a random extragalactic background (Schnitzeler 2010). It implies that there is a contribution from magnetized gas outside the SSC, or that there remains uncorrected GRM contributions in the background RRMs. However,  is not affected by this, since both subsamples are equally affected by these contributions. Removing the 19 sources with 6 < S/N < 8 leaves the statistics unchanged within the errors.

is not affected by this, since both subsamples are equally affected by these contributions. Removing the 19 sources with 6 < S/N < 8 leaves the statistics unchanged within the errors.

3.5. RM signature within the clusters and bridge

We investigate the RM substructure of the SSC by separately analysing the Abell clusters and the bridge region (where the SC two groups are). Figure 4 shows the y-map of the SSC, along with the |RRM| of the sources and the bridge box. It also highlights the r500 of the clusters and the groups. The excess RM scatter detected from these regions follows Eq. (5), with the same off-target sample and replacing σRM, on − target with the RM scatter of the bridge and clusters subsamples (Table 4).

|

Fig. 4. tSZ Planck map of the A3558-A3562 clusters system as well as the two massive groups of galaxies SC 1327 and SC1329. The triangles represent the locations of the background ASKAP radiogalaxies and they are colored according to their |RRM| values. We also show the r500 of the four objects as reference for the size of the system at the plane of the sky, along with their centers. The black contour represents the threshold we used to define the boundary between the off-target and on-target regions: ybdry = 2yrms = 4.24 × 10−6. The rectangular box defines the bridge. The sources inside it sample the region between the Abell clusters and outside their r500, despite some overlapping effects. The counterpart on-target sources that lie outside the box mainly sample the inside the of r500 of the clusters, thus its name: the clusters subsample. |

Detected excess in the RM scatter from the SCC, bridge, and clusters subsamples, along with their significance and the total number of sources inside each.

The excess RM scatter within the bridge implies that  is not completely dominated by the RM of the clusters. Furthermore, the fact that

is not completely dominated by the RM of the clusters. Furthermore, the fact that  is compatible within the uncertainties with

is compatible within the uncertainties with  , implies that we are probing a very similar range of

, implies that we are probing a very similar range of  (Eq. (8)) in the clusters and bridge regions. This is supported by the electron density range computed in Appendix A.5. We have also computed the excess RM scatter from each of the clusters, and found

(Eq. (8)) in the clusters and bridge regions. This is supported by the electron density range computed in Appendix A.5. We have also computed the excess RM scatter from each of the clusters, and found  and

and  at 4.6σ and 3.2σ respectively. These, further suggest that the range of

at 4.6σ and 3.2σ respectively. These, further suggest that the range of  values is similar in the entire SSC region and its substructures, i.e., clusters combined, bridge, and each cluster separately.

values is similar in the entire SSC region and its substructures, i.e., clusters combined, bridge, and each cluster separately.

3.6. Observed RM scatter profile with distance to nearest cluster and/or group

To further study how the scatter in the RM varies with distance from the clusters and groups centers, we follow Anderson et al. (2024) and Osinga et al. (2025), and define the observable for the RM scatter profile with distance between independent sources as

where we correct for the off-target contribution and for the RRM measurement errors (see Eq. (4)). The distance dnrst ≡ rnrst/r500 is the (projected) distance from a given source to the nearest cluster/group normalized by its r500. This definition deals with the fact that in the SSC, the complicated structure and geometry does not have spherical symmetry, as in single cluster studies. For this profile, we use the on-target region subsample (see Sect. 3.3, Figs. 1 and 4). The range of distances of our clusters and groups we are able to probe with these data is 0.3 ≲ dnrst ≲ 1.8.

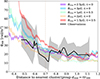

To bin our data, we used a sliding window approach, with fixed size of the window of N = 16 data points, which translates to a median window size of ∼0.3 r500. We obtained the 68% confidence level (C.L.) error region through bootstraping with 106 resamples. The resulting behavior (Fig. 5) is statistically consistent with a moderate anti-correlation between the scatter in the RM and dnrst, as a Spearman rank test yields a correlation coefficient of −0.54 with a p-value of 2 × 10−3.

For dnrst > 0.7 r500 we find sources that are inside the r500 of two different structures, i.e., a cluster and a group, thus we define this as the boundary at which overlapping structures begins. We quantified the trend with dnrst of sources unaffected by the overlapping of structures (dnrst ≤ 0.7 r500) with a Spearman rank test with correlation coefficient of −0.65 and p-value of 0.03. Beyond > 0.7 r500 the profile appears to flatten (Fig. 5, right of the vertical pink line). A Spearman rank test yields a correlation coefficient of 0.02, supporting this argument, but not with enough statistical significance (p-value of 0.9). To assess the impact of the bridge and galaxy groups on the profile in Fig. 5, we examined a subsample of sources, focusing on 19 sources whose lines of sight pass through the outer side of the cluster halos (counter to the bridge direction). After dividing the sample into two bins based on dnrst, we find that the scatter still closely follows the original profile for the entire sample. Therefore, the inner structures of the bridge and groups do not significantly affect the profile.

|

Fig. 5. Observed 𝔖RM(dnrst) profile (black line). The gray shaded region is the 68% C.L. error region. The blue crosses represent the amplitude of the RRMs of the on-target region, while the horizontal line is σoff − target. The arrow-shaped data point corresponds to an outlier value of ∼230 rad/m2. The vertical line is set at 0.7 r500, which is the scale at which overlapping effects start to take place. The horizontal segment at the lower left corner represents the median window size of ∼0.3 r500. The vertical purple error bar (lower right corner) indicates the median on-target δRRM = 4.6 rad/m2. |

3.7. Impact of small-scale magnetic fields on RM statistics

Magnetic fields coherent on scales smaller than our beam resolution, i.e., ∼20 kpc, may play an important role contributing, for instance, to the total  . They may also cause significant depolarization, such that within the SSC region we could be missing a population of polarized sources due to our selection criteria (Sect. 2.1.3). However, there is no clear evidence of a missing population given that the RM number densities are similar in the on-target and off-target regions (

. They may also cause significant depolarization, such that within the SSC region we could be missing a population of polarized sources due to our selection criteria (Sect. 2.1.3). However, there is no clear evidence of a missing population given that the RM number densities are similar in the on-target and off-target regions ( RMs/deg2 and

RMs/deg2 and  RMs/deg2).

RMs/deg2).

To further assess the RM scatter due to small-scale fields, which we denote by ΣRM following the convention in Osinga et al. (2025), we can use Burn’s law (Burn 1966; Sokoloff et al. 1998)

where λ0 ≃ 32 cm corresponds to the weighted mean of the observed wavelength-squared channels of Band 1 observations (ν ≃ 932 MHz). We set poff − target ≡ p0 = 5.3%, which is the median degree of polarization of the RM sources in the off-target sample. The median degree of polarization of the on-target sample is lower at pon − target ≡ p = 4.0%, and therefore on average these sources suffer additional depolarization due to a ΣRM, on/off = 3.6 rad/m2.

This small-scale RM contribution could contribute to a decrease in 𝔖RM at low values of dnrst. The median degree of polarization of on-target sources inside and outside 0.7 r500 is pon, ≤0.7 = 3.7% and pon, > 0.7 = 4.4%, respectively. Taking the ratio of these two, we find a depolarization of ∼0.84 between sources closer to the clusters’ centers with respect to those outside. Using Eq. (7), we find ΣRM, on − in/out = 2.9 rad/m2 (small in comparison to the total signal from the SSC of ≃30 rad/m2). These results indicate that beam depolarization appears to be a minor effect, likely playing a subdominant role in the overall RM statistics of our sample. Deeper observations and/or at higher frequencies, where depolarization effects are less pronounced, would be required to advance this analysis.

4. Modeling results

4.1. Magnetic field strength estimates with single-scale models

To estimate the required magnetic field strength to explain the RM observations in the SSC region, we can use a single-scale model such as that in Gaensler et al. (2001). This model assumes cells of fixed size Λ and constant electron density  , where magnetic field strength is constant with random orientation with line of sight. The observed σRM and magnetic field strength are then related by

, where magnetic field strength is constant with random orientation with line of sight. The observed σRM and magnetic field strength are then related by

where L = 1.8 Mpc is the path length (for details on their estimation we refer the reader to Appendix A.3). The coherence scale Λ was fixed to 50 kpc (Guidetti et al. 2008; Bonafede et al. 2010; Vacca et al. 2012; Govoni et al. 2017). The electron density estimates range from ∼10−4 to 10−3 cm−3 (Appendix A.5, Table A.2). From Eq. (8), we determined the magnetic field strength

in the bridge, clusters, and SSC regions, ranging from 0.2 μG to 1.7 μG in the bridge and cluster regions for a wide range of electron density assumptions (see Table A.2).

4.2. Gaussian random fields with MiRò

Here we investigate more realistic ICM models in order to obtain more robust magnetic field estimates, determine the field correlation with electron density (i.e., |B| ∝ neη), and assess whether an additional gas component besides the clusters and groups in the SSC is required. Therefore, we use semi-analytic models for the ICM that go beyond constant density assumptions and single-scale magnetic field fluctuations by incorporating electron density profiles for clusters and power spectra motivated by magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) simulations onto a Gaussian random magnetic field model. In particular, we modeled the electron density for the clusters and groups with universal density profiles (Pratt et al. 2022; see our Appendix B.1.1). To implement multi-scale fluctuations in the magnetic field, we used the power spectrum from Domínguez-Fernández et al. (2019) that peaks at 230 kpc. The MiRò code (Bonafede et al. 2013; Stuardi et al. 2021) is capable of incorporating the aforementioned elements, thus we use MiRò to model the SSC. Additional details on how this is done, can be found in Appendix B.1.2.

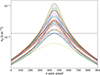

4.2.1. RM signatures predicted by MiRò

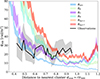

We compute the excess RM scatter from the bridge and clusters regions for the MiRò models in the following parameter space: Brms = 1 μG−3.5 μG, η = 0, 0.5, 1, where η parametrizes the correlation between magnetic field strength and electron density |B| ∝ neη. Following a Monte-Carlo and bootstrap method (see Appendix B.1.3) we obtained  ,

,  shown in Fig. 6 in comparison to the observed values. The bottom line shows the observed excess RM scatter in the bridge and clusters with its error bars, and vertically we show the estimates from the MiRò models.

shown in Fig. 6 in comparison to the observed values. The bottom line shows the observed excess RM scatter in the bridge and clusters with its error bars, and vertically we show the estimates from the MiRò models.

|

Fig. 6. Visual comparison of the excess RM scatter in the bridge and clusters regions between the observations (bottom line) and the Gaussian random field models from MiRò (computed following Appendix B.1.3). Horizontally, we represent the 68% C.L. error region for each model. Vertically we outline the statistical error estimated for the observations for visual comparison reasons. The values of Brms are in μG. |

With this statistic only, despite the fact that there is a significant amount of overlap between models due to the large associated uncertainties, we can already rule out some models. The criterion to decide was whether the predicted  is compatible, within the uncertainties (at the 1σ level), with the observed one. Given that the power spectrum is derived from cluster simulations and there is no evidence that indicates it should also hold in the bridge region, MiRò is expected to perform best at the clusters. Table B.1 shows the predicted RM scatter only of these models.

is compatible, within the uncertainties (at the 1σ level), with the observed one. Given that the power spectrum is derived from cluster simulations and there is no evidence that indicates it should also hold in the bridge region, MiRò is expected to perform best at the clusters. Table B.1 shows the predicted RM scatter only of these models.

Regarding the bridge region, note that only the inclusion of the two massive groups in the modeling is enough to explain the observations within the uncertainties for most models. Therefore, the contributions to the observed excess RM scatter from the clusters and groups dominates over other magnetized gas in the SSC. Hence, at the level of our data, there is no motivation to add an additional RM component (e.g. from filamentary gas) in the intercluster region.

4.2.2. Comparison between modeled and observed 𝔖RM(dnrst)

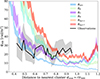

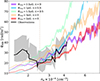

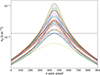

To better discriminate between models, we have computed scatter profiles of the RM with distance to the nearest cluster/group to compare the predictions from MiRò with the results in Sect. 3.6. To calculate the profiles from the mock RM maps, we binned the region with a sliding window of fixed step size Δdnrst = 10−2, and the 68% C.L. error region was computed through bootstrap with 104 resamples. For more details see Appendix B.1.4. In Fig. 7 we plot the resulting profiles as well as the observed profile from Sect. 3.6.

|

Fig. 7. Rotation measure scatter profiles (𝔖RM). The color-shaded regions represent the 68% C.L. error regions for the MiRò profiles (made with a sliding window of fixed size 0.01 r500). We show the five MiRò models with highest Bayesian evidence. The black line represents the observed scatter profile and the gray shaded region represents its 68% C.L. error region. The vertical line is at 0.7 r500, where overlapping structures start to dominate. |

To determine which model best reproduces the observed profile we defined a Gaussian likelihood function ℒk for each MiRò model k as follows:

where  is the total uncertainty in 𝔖RM from both the model and the data, as computed through bootstrapping. We computed the Bayesian evidence for each model which we can simply identify with the likelihood13. Among the models tested, the one that provides the best description of the observational data is the one with the largest value of lnℒk. To compare the performance between different models we compute Bayes factors ℬjk ≡ ℒj/ℒk and use the Kass & Raftery (1995) scale (K&R). For more details on the Bayesian model selection analysis see Appendix B.1.4.

is the total uncertainty in 𝔖RM from both the model and the data, as computed through bootstrapping. We computed the Bayesian evidence for each model which we can simply identify with the likelihood13. Among the models tested, the one that provides the best description of the observational data is the one with the largest value of lnℒk. To compare the performance between different models we compute Bayes factors ℬjk ≡ ℒj/ℒk and use the Kass & Raftery (1995) scale (K&R). For more details on the Bayesian model selection analysis see Appendix B.1.4.

To do this comparison, we used the value of the RM maps with a  compatible with the observed excess RM scatter in the clusters (see Fig. 6) only at the location of the on-target RMs and applied Eq. (6) with the same sliding window parameters applied to the observational profile. Even though MiRò is modeling overlapping structures, it is not accounting for the likely complex interactions between them. Therefore, we only compared the models to the data in the bins satisfying dnrst ≤ 0.7, where the overlapping structures are not dominating the behavior of the profiles. For values > 0.7 r500 all profiles exhibit a similar flattening and most of them lie within the uncertainties of the observed profile. Thus, in order not to bias our conclusions from the Bayesian model selection with the performance of the profiles in that range of distances, we do not include them in this analysis.

compatible with the observed excess RM scatter in the clusters (see Fig. 6) only at the location of the on-target RMs and applied Eq. (6) with the same sliding window parameters applied to the observational profile. Even though MiRò is modeling overlapping structures, it is not accounting for the likely complex interactions between them. Therefore, we only compared the models to the data in the bins satisfying dnrst ≤ 0.7, where the overlapping structures are not dominating the behavior of the profiles. For values > 0.7 r500 all profiles exhibit a similar flattening and most of them lie within the uncertainties of the observed profile. Thus, in order not to bias our conclusions from the Bayesian model selection with the performance of the profiles in that range of distances, we do not include them in this analysis.

In Table 5 we show the results of the Bayesian model selection analysis. The model with the largest Bayesian evidence corresponds to the model with the best predictive performance: Brms = 2.5 μG, η = 0. We show the Bayes factors of all other models with respect to it sorted by their performance up to the first one with strong evidence against it. We find barely worth mentioning evidence against the Brms = 3 μG, η = 0 model, and positive evidence against the best performing η = 0.5 model.

Bayesian evidence, Bayes factors, and K&R scale result for the MiRò model selection analysis.

Another approach is to use the scatter of the RM as a function of electron density, 𝔖RM(ne). This quantity could, in principle, provide a more direct mapping of the profile of the RM scatter from the center of the cluster toward its outskirts. However, the overlapping of structures in the SSC geometry, gives 𝔖RM(dnrst) the advantage of clearly showing at what scale these become important. Moreover, to estimate the electron density from the observations some assumptions need to be made, such as constant density and temperature over the path length (see Appendix A.5). Nonetheless, we show the profiles with respect to electron density and the comparison between models and data with the same Bayesian model selection analysis in Appendix B.4. From these profiles the data favors the model with Brms = 2.5 μG, η = 0, which is in agreement with the above results from the comparison with the profiles with dnrst. The five models with highest Bayesian evidence are the same as those from the profiles with dnrst. However in this case, the second best performing model is Brms = 1 μG, η = 0.5, with barely worth mentioning evidence against it.

4.2.3. Estimated magnetic field strength from MiRò

The average magnetic field strength can be estimated in the bridge and clusters regions from the magnetic field 3D cubes generated by MiRò, but retains significant systematic uncertainty due to the model selection ambiguity. Applying Eq. (B.6) to the model with the best performance according to the results from Sect. 4.2.2, i.e., Brms = 2.5 μG, η = 0, we obtained ⟨|B|⟩≃1.7 μG both in the bridge and clusters regions with a statistical error of ∼0.1 μG.

4.3. Comparison to cosmological MHD simulations: SLOW

MiRò provides a significant improvement in the ICM and magnetic field modeling in clusters with respect to single-scale models. Nevertheless, it lacks a realistic description of the complex interactions between the clusters and groups in the SSC (it only assumes noninteracting spheres with a given density profile), or variable magnetic field coherence lengths (the same power spectrum was assumed to hold at all scales and distances in the entire SSC). However, cosmological MHD simluations provide a solution to these problems.

Therefore, we extend our analysis to compare the RM data from Sect. 3 to modeling obtained from the SLOW (Simulating the Local Web)14 simulation set (Dolag et al. 2023; Böss et al. 2024). SLOW is a cosmological MHD simulation constrained to match the local Universe large-scale structure. We refer the reader to Appendix B.5 for the simulation setup details. From the simulation, we identified analogs of the SSC groups and clusters with the following properties (see discussion in Seidel et al. 2025):

-

SLOW-A3562: M500 = 5.3 × 1014 M⊙, r500 = 1.2 Mpc

-

SLOW-A3558: M500 = 1.46 × 1015 M⊙, r500 = 1.7 Mpc

-

SLOW-SC1329: M500 = 2.25 × 1014 M⊙, r500 = 0.91 Mpc

-

SLOW-SC1327: M500 = 2.04 × 1014 M⊙, r500 = 0.88 Mpc.

The radii were obtained from the M500 following the usual self-similarity relation M500 ∝ r5003. The masses from the analog clusters and groups differ from the observed ones by a factor ranging from 0.02 (SC 1327) to 3.5 (SC 1329) larger. The r500 is underpredicted by a factor 0.02 for SC 1327 and overpredicted by a factor 0.1 − 0.5 for A3558 and SC 1329, respectively, while SLOW-A3562 has a radius equal to the observed one.

Within the simulation adiabatic compression and dynamo processes amplify a seed magnetic field. This simulated magnetic field (Bsim) produces realistic values in galaxy clusters but the radial decline is too steep due to resolution effects (see Steinwandel et al. 2022), hence filament magnetic fields are under-estimated. To study the RM in filamentary regions between the clusters, several magnetic field models are applied to rescale the simulated magnetic field. Namely: a constant plasma-β ratio between magnetic and thermal pressures (Bβ); turbulent and magnetic pressure equilibrium (Bℱ); a magnetic flux conservation during amplification by 3D compression mechanism (Bff); and two turbulent dynamo scenarios, where one of them operates for a range of densities ne ≳ 10−4 cm−3 (Bdyn, ↓) with an attached decline at ne < 10−4 cm−3 to match observations for filament magnetic fields (Carretti et al. 2023), and the other is a pure saturated dynamo (Bdyn, ↑); see Böss et al. (2024) for details.

To understand how these models predict different correlations between magnetic field strength and electron density (in analogy to the η parameter in the modeling with MiRò), we have fit these two quantities in the electron density range 4 × 10−5 ≤ ne [cm−3] ≤ 8 × 10−4, where the comparison between the SLOW models and the data is performed (see Appendix B.5.2). We found that all amplification scenarios are well fitted by a power law with: ηsim = 0.44, ηβ = 0.53, ηℱ = 0.50, ηff = 0.67, ηdyn, ↓ = 0.51 and ηdyn, ↑ = 0.50.

Using SLOW it is possible to obtain maps of different physical effects and observables, e.g., X-ray surface brightness, tSZ effect, temperature, electron density. As an example, Fig. 8 shows the electron number density and y-Compton maps, along with the RM map for one of the dynamo mechanisms of the Shapley analog found in the SLOW simulation. While generally well reproducing the clusters and groups’ masses and sizes, it is worth mentioning that there are two main differences with respect to the observations: the projected distance between the Abell clusters is a factor 0.8 lower, and the positions of the groups do not exactly match the observations.

|

Fig. 8. Zoom-in simulation of the Shapley analog found in the SLOW simulation. From left to right: electron number density, y-Compton parameter, RM map for the dynamo ↓ amplification mechanism. We show the r500 of the two clusters and the two groups, namely: 1.7, 1.2, 0.91, and 0.88 Mpc in decreasing order of mass. |

Using mass weighted magnetic field maps for the different amplification mechanisms, we have computed the average magnetic field in the bridge and clusters regions following Eq. (B.6)15. All models provide magnetic field strengths of the order of ∼1 to 3 μG, both in the bridge and clusters regions, except the Bsim model that yields ∼0.1 μG. The statistical errors are ≲10−3 μG.

4.3.1. RM signatures predicted by SLOW

We determine  and

and  from the SLOW SSC analog in a similar manner to the observations (see Appendix B.5.2). We have estimated the excess RM scatter in these regions using the RM maps derived from all SLOW magnetic field amplification mechanisms.

from the SLOW SSC analog in a similar manner to the observations (see Appendix B.5.2). We have estimated the excess RM scatter in these regions using the RM maps derived from all SLOW magnetic field amplification mechanisms.

Based on  we find that the Bsim model is inconsistent with observations at 4.6σ, and therefore can be ruled out (see Fig. 9). This implies that we can rule out the possibility that in the gas between the Abell clusters no further amplification of the fields is taking place.

we find that the Bsim model is inconsistent with observations at 4.6σ, and therefore can be ruled out (see Fig. 9). This implies that we can rule out the possibility that in the gas between the Abell clusters no further amplification of the fields is taking place.

|

Fig. 9. Visual comparison of the excess RM scatter in the bridge and clusters regions between the observations (bottom line) and all magnetic field amplification mechanisms implemented in SLOW. Horizontally, we represent the 68% C.L. error region for each model. Vertically we outline the statistical error estimated for the observations for visual comparison reasons. |

All other mechanisms are able to reproduce the observed scatter in the clusters. The Bβ model, while showing a larger RM scatter in the bridge than in the clusters region, it also predicts a  that is consistent with observations at the 1σ level. Moreover, similarly to what we found from the Gaussian random field modeling with MiRò, with this statistic we find overlap between these models within the uncertainties, thus being unable to discriminate between them. Table B.4 lists the values of the excess RM scatter shown in Fig. 9.

that is consistent with observations at the 1σ level. Moreover, similarly to what we found from the Gaussian random field modeling with MiRò, with this statistic we find overlap between these models within the uncertainties, thus being unable to discriminate between them. Table B.4 lists the values of the excess RM scatter shown in Fig. 9.

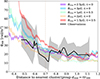

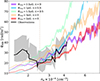

4.3.2. Comparison between simulated and observed 𝔖RM(dnrst)

To better discriminate between models, using the RM maps derived from the simulation, we explore how the RM scatter behaves with distance to the center of the clusters for all amplification mechanisms considered. Details of how these profiles were constructed are provided in Appendix B.5.3. We cannot directly compare with the observational results in Sect. 3.6, because of the differences in projected distance between the clusters and the location of the groups. Therefore, we defined dnrst this time as the distance to the nearest cluster only, without including the groups. We computed a profile of the RM scatter from the observations with this new definition of distance, using Eq. (6).

Figure 10 shows the new observational 𝔖RM(dnrst) profile and the equivalent SLOW profiles of all amplification mechanisms. We have performed a Spearman rank test to the observed profile to asses its flatness, obtaining a correlation coefficient of −0.36 with a p-value of 0.05. This indicates that no statistically significant anti-correlation is found, in contrast with the result from Sect. 3.6 when we included the groups into the analysis.

|

Fig. 10. Rotation measure scatter profiles (𝔖RM) with distance to the nearest cluster only. The black line represents the observed scatter profile, which was computed using a fixed sliding window of N = 16 points. The gray shaded region represents its 68% confidence intervals obtained with bootstrapping resampling. The observational dnrst values have been rescaled by a factor of ×0.8 to account for the difference in projected distance between the SLOW analog clusters and the real A3558-A3562. The colored regions are the SLOW 68% C.L. error regions (made with a sliding window of fixed size 0.01 r500) for the RM maps that correspond to all amplification mechanisms of the magnetic field in the intercluster region. |

To determine the performance of these models we implemented a Bayesian analysis similar to that of Sect. 4.2.2. The main difference from the previous analysis is that this time we are not able to directly map the positions of the observed RMs in the SLOW SSC analog maps. Therefore, we used the value of the RM maps inside the entire analog on-target region16 to produce the profiles. However, we binned the SLOW profiles in the same way as the observational profile to make the comparison with the data by evaluating  at the same dnrst, i bins (see Appendix B.5.3).

at the same dnrst, i bins (see Appendix B.5.3).

In Table 6 we show the results from the Bayesian analysis. The turbulent scenario for amplification of the magnetic field in the intercluster region, i.e., Bℱ is the one that provides the best description of the data. We have very strong evidence against all other mechanisms according to the K&R scale.

Bayesian evidence, Bayes factors, and K&R scale result for the SLOW magnetic field amplification mechanisms model selection analysis.

5. Discussion

The main objective of this work is to characterize the properties of the detected magnetized gas in the SSC (Sects. 3.4 and 3.5). To do this, we first modeled the SSC with Gaussian random magnetic fields with the MiRò code (Sect. 4.2). These models provide insights into the correlation of magnetic field strength and electron density in the ICM through the η parameter defined as |B| ∝ neη. However, after estimating σRM in the bridge and clusters regions predicted by MiRò (Sect. 4.2.1), we found a model degeneracy, i.e., with this information alone, we are not able to distinguish between models with different values of η. Moreover, we have also estimated how the uncertainties in σRM behave when increasing the RM grid density, and found that even for SKA-expected grid densities ∼100 RMs/deg2, this statistic suffers from large uncertainties (see Appendix B.3). These statistical difficulties are not model-dependent, i.e., the local-constrained cosmological MHD simulation SLOW (Sect. 4.3), despite providing a much more detailed prescription of ICM physics, suffers from them as well (Fig. 9). Therefore, this motivates the need to study the trend in the RM scatter as a function of distance from the cluster and group centers (𝔖RM(dnrst) profiles) to gain further insight into the physical properties of the magnetized gas in the SSC.

5.1. Flatter than expected 𝔖RM profiles: The η < 0.5 puzzle

As mentioned in the previous subsection, while Gaussian random field models (MiRò) with η = 0.5, corresponding to a constant thermal-to-magnetic energy scaling, are able to match the observations in terms of  (Fig. 6), there are degeneracies with other models with η < 0.5. The analysis of the RM scatter as a function of distance to the nearest cluster/group, 𝔖RM(dnrst) (Sect. 4.2.2), revealed that the model with highest Bayesian evidence, hence, the one with best predictive performance, is Brms = 2.5 μG, η = 0, which has an unphysical scaling of η = 0 (Table 5). Furthermore, we found positive evidence against the best-performing η ≥ 0.5 model, i.e., Brms = 1 μG, η = 0.5. In an attempt to overcome the difficulties in the analysis introduced by the complicated geometry and overlapping structures, we analyzed profiles with respect to electron density 𝔖RM(ne) and followed the same Bayesian analysis for all MiRò models Appendix B.4. While these further indicate that Brms = 2.5 μG, η = 0 is still the best-performing model, which has the unphysical η = 0 scaling, there is only barely worth mentioning evidence against the Brms = 1 μG, η = 0.5 model (Table B.3).

(Fig. 6), there are degeneracies with other models with η < 0.5. The analysis of the RM scatter as a function of distance to the nearest cluster/group, 𝔖RM(dnrst) (Sect. 4.2.2), revealed that the model with highest Bayesian evidence, hence, the one with best predictive performance, is Brms = 2.5 μG, η = 0, which has an unphysical scaling of η = 0 (Table 5). Furthermore, we found positive evidence against the best-performing η ≥ 0.5 model, i.e., Brms = 1 μG, η = 0.5. In an attempt to overcome the difficulties in the analysis introduced by the complicated geometry and overlapping structures, we analyzed profiles with respect to electron density 𝔖RM(ne) and followed the same Bayesian analysis for all MiRò models Appendix B.4. While these further indicate that Brms = 2.5 μG, η = 0 is still the best-performing model, which has the unphysical η = 0 scaling, there is only barely worth mentioning evidence against the Brms = 1 μG, η = 0.5 model (Table B.3).

The observed profile with respect to distance to the nearest cluster and/or group (Fig. 5), while showing an anti-correlation as suggested by a Spearman rank test, is still considerably flatter than the profiles derived from MiRò, which causes these η < 0.5 models to be consistent with the data. However, the observed profile is consistent with a flat dependence when considering the distance to the nearest cluster only (Sect. 4.3.2), as well as with electron density (Fig. B.1).

Considering that MiRò was designed mainly for single-cluster studies, it does not account for interactions between the clusters and groups of the SSC or a spatially variable magnetic field coherence length. However, the SLOW simulations overcome these limitations, providing detailed ICM cluster physics with a full interaction and merger history17, amplification of a seed magnetic field by adiabatic compression and dynamo processes throughout the dynamical evolution of the system, and prescriptions for further amplification mechanisms outside the cluster cores. As a consequence, the analog SSC provided by SLOW (Fig. 8) is the best possible description of the system to date.

The 𝔖RM(dnrst) profile comparison between all SLOW amplification mechanisms and the observed profile (Fig. 10) indicates, through the Bayesian model selection analysis, that the turbulent velocity scenario (Bℱ) has the best predictive performance (Table 6). There is very strong evidence against all other amplification mechanisms. Nonetheless, there is a large discrepancy at scales dnrst ≳ 0.8. It is possible that this could be solved by more directly comparable positions of the analog SC groups with respect to the observed ones (Fig. 8 vs. Fig. 4).

In the Bℱ scenario, the magnetic field strength is rescaled as a fraction ℱ of the turbulent pressure, which was assumed to be in equilibrium with magnetic pressure (ℱ = 1). This model defines turbulent velocity as the deviation from the gas bulk velocity (similar to e.g., Simonte et al. 2022) and therefore preferentially amplifies magnetic fields in regions of shocks. This opens an avenue for future investigations with more elaborate sub-grid models for turbulence (e.g., Iapichino et al. 2017) of magnetic field amplification at shocks via the Bell instability. Recent results by Zhou et al. (2024) show magnetic field generation and amplification in low-density accretion shock regimes which could provide stronger magnetic fields than can be captured in the SLOW simulation. It will also be worth investigating the impact of astrophysical seeds for magnetic fields such as supernovae and active galactic nuclei (AGN), and how feedback effects contribute to distributing, mixing and amplifying magnetic fields (see e.g., Donnert et al. 2018, for a review). This could have a further impact on the η < 0.5 puzzle and will need to be investigated with the next generation of SLOW simulations.

Other recent works like Osinga et al. (2025), Khadir et al. (2025), have found similar results, where the data suggest models with η < 0.5. Understanding what is driving the flattening of the observed RM profile is key to solving this problem. As pointed out by Osinga et al. (2025), there seems to be an inherent difference between studies that use resolved radio galaxies, such as Murgia et al. (2004), Bonafede et al. (2010), Vacca et al. (2012), Govoni et al. (2017), and Stuardi et al. (2021), which find η ≥ 0.5, and those using unresolved radio sources. The latter have found this flatter-than-expected 𝔖RM profile as a function of distance from the cluster center (Böhringer et al. 2016; Stasyszyn & de los Rios 2019; Osinga et al. 2022, 2025; Khadir et al. 2025), which favor the η < 0.5 models. The size of the samples is considerably larger in studies where the η < 0.5 models are favored, e.g., Osinga et al. (2025) stacks a sample of order ∼100 clusters with ∼600 RMs, and Khadir et al. (2025) uses 111 RM. While studies with resolved radio galaxies derive their conclusions from a limited number of sources, typically ≲10, their focus on individual clusters allows a more precise control of some of the possible confounding factors in stacking studies and interacting systems (e.g., Bonafede et al. 2010; Pagliotta et al. 2025).

Note that the RM scatter profile derived from observations in this work (Fig. 5), matches the behavior of the profile derived by Osinga et al. (2025) for sources behind the clusters (see their Fig. 6), i.e., they have the same amplitude of the profile at similar scales and a similar flattening at ≳0.7 r500. This implies that the behavior found for the SSC profile is not a special case, but rather likely representative of the general population.

5.2. The possibility of a missing RM population due to depolarization

One major difference between our observations and the SLOW simulations is that the observations suffer from depolarization effects. One expects that sources that probe lower projected distances from the clusters’ centers have a large scatter in the RM, and it is at these scales precisely where we could be missing sources due to depolarization. Given our beam’s linear size of ∼20 kpc, we cannot resolve spatial fluctuations below this scale. This means that there could be sources with an intrinsic scatter in their RMs that we are not accounting for. We studied this in Sect. 3.7, to find missing additional scatter of only ΣRM ≲ 4 rad/m2, on average, due to this effect. This is clearly not enough to boost the scatter in the first bins of the profiles in Figs. 7 and 10.

In fact, we can estimate what is the ΣRM scatter we would need to reconcile the observed 𝔖RM(dnrst) value in the first bin (much flatter than expected; see Fig. 10) with the value predicted by the Bℱ magnetic field amplification scenario (the best performing model according to the Bayesian analysis). We would need 16 sources (the size of the sliding window used to compute the profile) with ΣRM ≃ 50 rad m−2 to yield a  , where d1 corresponds to the first bin in dnrst. This implies we would be losing a scatter as high as

, where d1 corresponds to the first bin in dnrst. This implies we would be losing a scatter as high as  . Moreover, we do not find any significant difference in the density of the RM grid in regions closer to the clusters centers than at larger distances. Note though that in this work, we set a threshold of p ≥ 1% to produce the catalog, while future ASKAP observations of the Shapley Supercluster may allow us to use a lower threshold of 0.1% (Gaensler et al. 2025). This could reveal more sources potentially enabling an analysis close to the cluster and group centers.

. Moreover, we do not find any significant difference in the density of the RM grid in regions closer to the clusters centers than at larger distances. Note though that in this work, we set a threshold of p ≥ 1% to produce the catalog, while future ASKAP observations of the Shapley Supercluster may allow us to use a lower threshold of 0.1% (Gaensler et al. 2025). This could reveal more sources potentially enabling an analysis close to the cluster and group centers.

6. Conclusions

In this work we study the properties of the magnetized gas in the Shapley Supercluster core (SSC), with a special emphasis on the ≃4.2 Mpc (projected) intercluster region (or bridge) between the massive Abell clusters (A3558-A3562). We use radio polarization data from the ASKAP-POSSUM Pilot II survey in combination with thermal Sunyaev-Zeldovich effect data (from Planck).

Upon the detection of this magnetized gas, we followed different modeling approaches to characterize it, namely: semi-analytic galaxy cluster modeling with universal density profiles and Gaussian random fields following a power spectrum (MiRò), and constrained local-Universe cosmological MHD simulations (SLOW). Both of these models generate mock RM maps that we used to compare with the RMs we derived from ASKAP-POSSUM observations. The main conclusions derived from this work are the following:

-

We detected a highly significant (6.7σ) excess RM scatter from the magnetized gas present in the SSC,

rad/m2. Furthermore, we determined that this excess is not dominated by the Abell clusters’ contribution alone, given that the bridge region where the massive groups SC 1327 and SC 1329 are has a comparable excess RM scatter to the clusters

rad/m2. Furthermore, we determined that this excess is not dominated by the Abell clusters’ contribution alone, given that the bridge region where the massive groups SC 1327 and SC 1329 are has a comparable excess RM scatter to the clusters  rad/m2.

rad/m2. -

We also studied the trend of the RM scatter as a function of distance (normalized by r500) to the nearest cluster and/or group 𝔖RM(dnrst), in the range sampled by our data, 0.3 ≲ dnrst ≲ 1.8. A Spearman rank test revealed a moderate anti-correlation (correlation coefficient −0.54) with a p-value of 2 × 10−3. Overlapping structures in the SSC appear in our data for dnrst > 0.7 r500.

-

We estimated the average magnetic field strength in the bridge and clusters regions (Fig. 1). Single-scale model estimates, for a variety of assumptions, yield 0.2−1.7 μG (Table A.2); MiRò estimates are ≃1.7 μG for the best performing model (Sect. 4.2.3), while SLOW predicts 1−3 μG for all amplification mechanisms, except for Bsim, which yields ∼0.1 μG.

-

When comparing MiRò with observations, models with η < 0.5 are preferred by the data, as revealed by a comparison of RM scatter profiles both with distance (𝔖RM(dnrst), Sect. 4.2.2) and electron density (𝔖RM(ne), Appendix B.4) through the Bayesian model selection analysis.

-

The SLOW simulations provide the most detailed and complete description of the ICM physics and, despite minor differences in projected distance between the clusters and the position of the groups, an analog SSC system was identified (Fig. 8). Out of the six different amplification mechanisms for the magnetic field, the RM scatter profile analysis (Sect. 4.3.2) indicates that the best performing model is the one with amplification by turbulent velocity Bℱ ∝ ne1/2vturb in the intercluster region, with equilibrium between turbulent and magnetic energies.

-

The observational RM profiles are flatter than expected compared to all models considered in this work. We refer to this as the η < 0.5 puzzle, which cannot be easily solved by accounting for depolarization effects (considering the instrumental polarization of the ASKAP pilot survey observations of ≲1%). We find no evidence of a large, missing population of sources close to the cluster centers that would contribute to the RM scatter sufficiently (see Sect. 5.2).

Given that the RM profile of the SSC is not a special case and is likely representative of the RM behavior of the general population (Sect. 5), it provides the perfect laboratory for enhancing our understanding of cluster physics and magnetic field amplification scenarios (e.g., does magnetic reconnection play a significant role?). In the near future, the full POSSUM survey data, with an order of magnitude better threshold in the degree of polarization (Gaensler et al. 2025), will be able to detect more RMs toward the core of the clusters and groups. Deeper MeerKAT and eventually SKA-Mid observations can further improve RM grid densities, while their higher angular resolution (Braun et al. 2019) should allow for more detailed analysis on scales closer to the cluster centers. Higher resolution tSZ maps from the Simons Observatory (Ade et al. 2019) will also significantly improve the electron density mapping of complex systems like the SSC.

Acknowledgments

D. Alonso-López would like to thank the GUAIX group at the UCM for useful help and comments throughout the development of this work. D. Alonso-López also acknowledges support from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid and Banco Santander through the predoctoral grant CT25/24 and PID2022-138621NB-I00, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER, EU. D. Alonso-López and SPO acknowledge support from the Comunidad de Madrid Atracción de Talento program via grant 2022-T1/TIC-23797, and grant PID2023-146372OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU. This scientific work uses data obtained from Inyarrimanha Ilgari Bundara/the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory. We acknowledge the Wajarri Yamaji People as the Traditional Owners and native title holders of the Observatory site. The Australian SKA Pathfinder is part of the Australia Telescope National Facility (https://ror.org/05qajvd42) which is managed by CSIRO. Operation of ASKAP is funded by the Australian Government with support from the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy. ASKAP uses the resources of the Pawsey Supercomputing center. Establishment of ASKAP, the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory and the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre are initiatives of the Australian Government, with support from the Government of Western Australia and the Science and Industry Endowment Fund. The POSSUM project (https://possum-survey.org) has been made possible through funding from the Australian Research Council, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Research Chairs Program, and the Canada Foundation for Innovation. AB acknowledges support from the ERC-CoG project BELOVED n. 101169773. KD acknowledges support by the COMPLEX project from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant agreement ERC-2019-AdG 882679. BAS acknowledges support by the grant agreements ANR-21-CE31-0019/490702358 from the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche/Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG through the LOCALIZATION project. BAS acknowledges support by the COMPLEX project from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program grant agreement ERC-2019-AdG 882679. LMB would like to thank Frederik Groth for help with the vortex-p code. LMB is supported by NASA through grant 80NSSC24K0173. C.S.A. acknowledges funding from the Australian Research Council in the form of FT240100498. POSSUM is partially funded by the Australian Government through an Australian Research Council Australian Laureate Fellowship (project number FL210100039 awarded to NM-G). The Dunlap Institute is funded through an endowment established by the David Dunlap family and the University of Toronto. Basic research in radio astronomy at the Naval Research Laboratory is supported by 6.1 Base funding. SM acknowledges support from grant PID2023-146372OB-I00, funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU.

References

- Ade, P., Aguirre, J., Ahmed, Z., et al. 2019, JCAP, 2019, 056 [Google Scholar]

- Akahori, T., & Ryu, D. 2011, ApJ, 738, 134 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, C. S., Heald, G. H., Eilek, J. A., et al. 2021, PASA, 38, e020 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]